1. Introduction

Anatomic pathology provides definitive histopathological assessments essential for disease classification, prognostic stratification, and treatment planning across oncology, infectious diseases, and inflammatory conditions [

1,

2]. Cancer accounts for approximately 10 million deaths annually worldwide, with anatomopathological diagnosis serving as the reference standard for tumor classification according to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria [

3]. Contemporary pathology workflows generate substantial volumes of narrative reports documenting macroscopic descriptions, microscopic findings, and diagnoses, which are integrated into electronic medical records [

4,

5]. These textual data support clinical decision-making, quality assurance, epidemiological surveillance, and retrospective research initiatives across healthcare institutions [

6,

7]. However, the predominance of unstructured free-text formats creates substantial barriers to automated information extraction, semantic interoperability, and large-scale computational analysis [

8,

9].

Converting free-text clinical narratives into structured, usable data is a key focus in the field of artificial intelligence (AI), which is rapidly transforming healthcare with applications for diagnostic imaging, predictive analytics, and clinical decision support. In specialized domains, AI methodologies have demonstrated significant utility, from systematic reviews of diagnostic criteria in endocrinology, such as for polycystic ovary syndrome [

10], to novel neural networks that enhance tumor identification in oncology imaging [

11]. A pivotal yet underexplored application is the semantic processing and standardization of unstructured clinical text. This work addresses that gap by focusing on anatomic pathology reports, where AI can automate the labor-intensive bottleneck of coding, thereby enabling data interoperability for research and clinical workflows.

The transformation of unstructured clinical narratives into structured, standardized data representations requires sophisticated natural language processing approaches capable of medical domain adaptation [

12,

13]. Named entity recognition has emerged as a foundational technique for identifying clinical concepts within free text, with transformer-based architectures demonstrating substantial performance gains over traditional rule-based approaches and statistical methods [

14,

15]. BioBERT introduced domain-specific pre-training on PubMed abstracts and PubMed Central (PMC) full-text articles, achieving state-of-the-art results across multiple biomedical named entity recognition benchmarks, including disease mentions, chemical compounds, and gene identifiers [

16]. Subsequent models, including ClinicalBERT and BioClinicalBERT, incorporated clinical notes from the MIMIC-III database, further improving the performance on clinical entity extraction tasks [

17,

18]. These transformer architectures use self-attention mechanisms to capture long-range contextual dependencies and semantic relationships, which are essential for disambiguating medical terminology [

19].

Beyond entity extraction, normalization to standard medical terminologies represents an equally critical challenge for achieving semantic interoperability across healthcare systems [

20,

21]. The Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT) provides comprehensive coverage with over 350,000 active concepts spanning clinical findings, procedures, body structures, and organisms [

22]. The Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC) standardizes laboratory test nomenclature with approximately 95,000 terms, facilitating data exchange across laboratory information systems [

23]. The International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11) offers a contemporary coding framework supporting epidemiological reporting, clinical documentation, and healthcare resource allocation [

24]. However, mapping free-text clinical entities to these standardized terminologies requires sophisticated approaches capable of handling synonyms, abbreviations, contextual variations, and hierarchical concept relationships [

25,

26]. Recent research has explored metric learning, retrieval-based methods, and graph neural networks for entity linking tasks, with varied results depending on the complexity of the terminology and the availability of training data [

27,

28]. Retrieval-augmented generation has emerged as a promising paradigm that grounds language model predictions in external knowledge bases through dense vector retrieval, demonstrating improvements in factual accuracy and domain-specific question answering [

29,

30].

Despite these advances, several research gaps persist in automated pathology report processing. First, most existing studies focus on English-language clinical texts, with limited validation on non-English pathology reports from diverse geographic regions [

31]. Second, multi-ontology mapping approaches typically evaluate the performance on individual terminologies rather than simultaneous mapping to SNOMED CT, LOINC, and ICD-11 within unified frameworks [

32]. Third, the integration of retrieval-augmented approaches with supervised classification for medical entity normalization remains underexplored compared to standalone architectures [

33]. Finally, rigorous statistical validation, including effect size reporting, confidence interval estimation, and inter-model comparison testing, is often absent from published studies [

34].

Based on the identified research gaps, our study aimed to (i) develop and validate a BioBERT-based named entity recognition model for extracting the sample type, test performed, and finding entities from anatomopathological reports; (ii) implement a hybrid standardization framework combining BioClinicalBERT multi-label classification with dense retrieval-augmented generation for simultaneous mapping to the SNOMED CT, LOINC, and ICD-11 terminologies; and (iii) conduct a comprehensive performance evaluation with rigorous statistical testing, including bootstrap confidence intervals, agreement measures, and inter-model comparisons on real-world clinical data.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

This retrospective study received approval from the Ethics Committee of the Military Hospital of Tunis, Tunis, Tunisia (decision number 116/2025/CLPP/Hôpital Militaire de Tunis) on 7 July 2025, before data collection and analysis. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patient information was rigorously anonymized to ensure confidentiality, privacy, and data protection. Data handling and analysis were undertaken solely by anatomical pathologists and data scientists involved in the study, ensuring strict adherence to ethical standards and institutional guidelines.

2.2. Data Collection and Corpus Development

We collected 560 anatomopathological reports retrospectively from the information system of the Main Military Teaching Hospital of Tunis between January 2020 and December 2023. Each report corresponded to a unique patient case and was manually annotated by board-certified anatomical pathologists. Standard preprocessing included removing uninformative headers and footers, de-identifying sensitive personal data, and correcting only typographical errors to achieve complete anonymization. The annotation process identified three primary entity types: sample type (tissue specimens submitted for examination), test performed (histological techniques and staining methods), and finding (diagnostic observations and pathological descriptions).

To ensure consistent and reproducible annotation, we developed the following guidelines, as detailed in

Table 1.

Manual assignment of the reference codes from SNOMED CT, LOINC, and ICD-11 terminologies was performed using official terminology resources obtained from

https://www.snomed.org (accessed 15 August 2025),

https://loinc.org (accessed 15 August 2025), and

https://icd.who.int (accessed 15 August 2025), respectively.

2.3. External Knowledge Base Construction

For the retrieval-augmented generation component, we constructed an external knowledge base using the official releases of SNOMED CT (version 08.2025), LOINC (version 2.81), and ICD-11 (version 01/2024). To ensure clinical relevance to anatomical pathology, we selected relevant subsets from each terminology, guided by their organizational structures: hierarchies for SNOMED CT, class designations for LOINC, and chapter classifications for ICD-11. We integrated and indexed these standardized clinical concepts, along with their associated codes, labels, and relationships, to enable semantic similarity retrieval during model inference.

2.4. Named Entity Recognition Model

We implemented BioBERT v1.1 (dmis-lab/biobert-v1.1) for token-level entity classification, using the Hugging Face Transformers library, version 4.45.0 (Hugging Face Inc., New York, NY, USA) [

16]. Reports were preprocessed and converted to JSON format with sentence-level segmentation. The BioBERT tokenizer applied WordPiece subword tokenization, with the token labels aligned to the subwords using word_ids() mapping. Filler tokens and unaligned tokens were masked using −100 label identifiers. The architecture consisted of bidirectional transformer layers generating contextualized feature vectors for each token position. Self-attention mechanisms captured the contextual dependencies across sequences according to the formulation [

15]:

where

represent query, key, and value matrices, respectively, and

denotes key vector dimensionality. A fully connected classification layer mapped contextualized embeddings to entity type predictions through softmax activation:

where

represents the logit score for class

. Model training optimized the cross-entropy loss:

where

denotes accurate labels and

represents predicted probabilities.

2.5. Training Configuration for Named Entity Recognition

BioBERT v1.1 was fine-tuned for three epochs using the AdamW optimizer as implemented in PyTorch, version 2.4.1 (PyTorch Foundation, San Francisco, CA, USA), with a learning rate of 2 × 10

−5, a weight decay of 0.01, and a batch size of 8 for both the training and evaluation phases [

35]. Cross-entropy loss with ignored labels set to −100 guided optimization. Data were split into 80% for training and 20% for testing. Training was conducted using Python 3.12.12 (Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA) with the Hugging Face Transformers library and PyTorch, via the Hugging Face Trainer API, on NVIDIA GPU hardware/infrastructure (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The evaluation metrics included the token-level precision, recall, and F1-score calculated separately for each entity class.

2.6. Entity Standardization Architecture

The standardization pipeline integrated supervised classification and semantic retrieval components. BioClinicalBERT from emilyalsentzer/Bio_ClinicalBERT encoded the extracted entity mentions into dense representations, projecting them into the model’s latent space [

18]. A multi-label classification head produced probability distributions over the target code spaces for the SNOMED CT, LOINC, and ICD-11 terminologies. The top-k candidates with the highest probabilities were extracted from the classification outputs.

2.7. Retrieval-Augmented Generation Module

For retrieval augmentation, we encoded all the terminology concepts from the SNOMED CT, LOINC, and ICD-11 databases using BioClinicalBERT to generate dense vector representations. During inference, the query entity embeddings were compared with the indexed terminology vectors using the cosine similarity. The nearest-neighbor concepts were retrieved as candidate codes from the external knowledge base via dense passage retrieval [

29].

2.8. Fusion and Reranking Strategy

The final standardization decision combined outputs from the BioClinicalBERT classification and retrieval modules through a learned fusion mechanism. A weighted decision rule was optimized via 5-fold cross-validation, determining whether to select the classifier’s prediction or the retrieved concept. When the classification and retrieval outputs disagreed, the system applied the learned weights to prioritize the more reliable component. As a fallback mechanism, retrieval-based predictions overrode classifier errors when the classification confidence was below the threshold values. This approach balanced discriminative accuracy from supervised learning with semantic robustness from knowledge base retrieval.

2.9. Training Configuration for Standardization

BioClinicalBERT was trained using the AdamW optimizer with cross-entropy loss on the annotated dataset for 10 epochs, with early stopping based on the validation loss. The retrieval-augmented generation component operated only during inference, retrieving the closest terminology codes based on the cosine similarity scores. The fusion module combined predictions from trained BioClinicalBERT and reference retrieval-augmented generation using weighted scoring, with the optimal weights determined through cross-validation on the training set. Final predictions for the SNOMED CT, LOINC, and ICD-11 codes were generated through the integrated fusion architecture.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

The performance evaluation employed precision (positive predictive value), recall (sensitivity), and F1-score (harmonic mean of the precision and recall), calculated separately for each entity type and terminology. Bootstrap resampling with 10,000 iterations estimated the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the performance metrics [

36]. One-sample

t-tests assessed whether the model performance significantly exceeded a baseline threshold of 0.5. Cohen’s Kappa and the Matthews correlation coefficient quantified the agreement between the predictions and ground truth annotations, accounting for chance agreement [

37]. McNemar’s test evaluated the prediction discordance between model pairs [

38]. Permutation tests with 10,000 iterations assessed whether the observed differences in accuracy between models could be due to chance. All the statistical analyses were conducted using Python 3.12.12 and its scientific computing libraries (NumPy version 2.1.1, SciPy version 1.14.1, scikit-learn version 1.5.2) on the held-out test set.

3. Results

3.1. Named Entity Recognition Performance by Entity Type

The BioBERT model achieved strong performance across all the clinical entity types on the test set.

Table 2 presents the performance metrics organized by entity type, with an overall mean precision of 0.969, a recall of 0.958, and an F1-score of 0.963. Sample type entities achieved a precision of 0.97, a recall of 0.98, and an F1-score of 0.97. Test performed entities demonstrated precision of 0.97, a recall of 0.99, and an F1-score of 0.98. Finding entities achieved a precision of 0.97, a recall of 0.90, and an F1-score of 0.93.

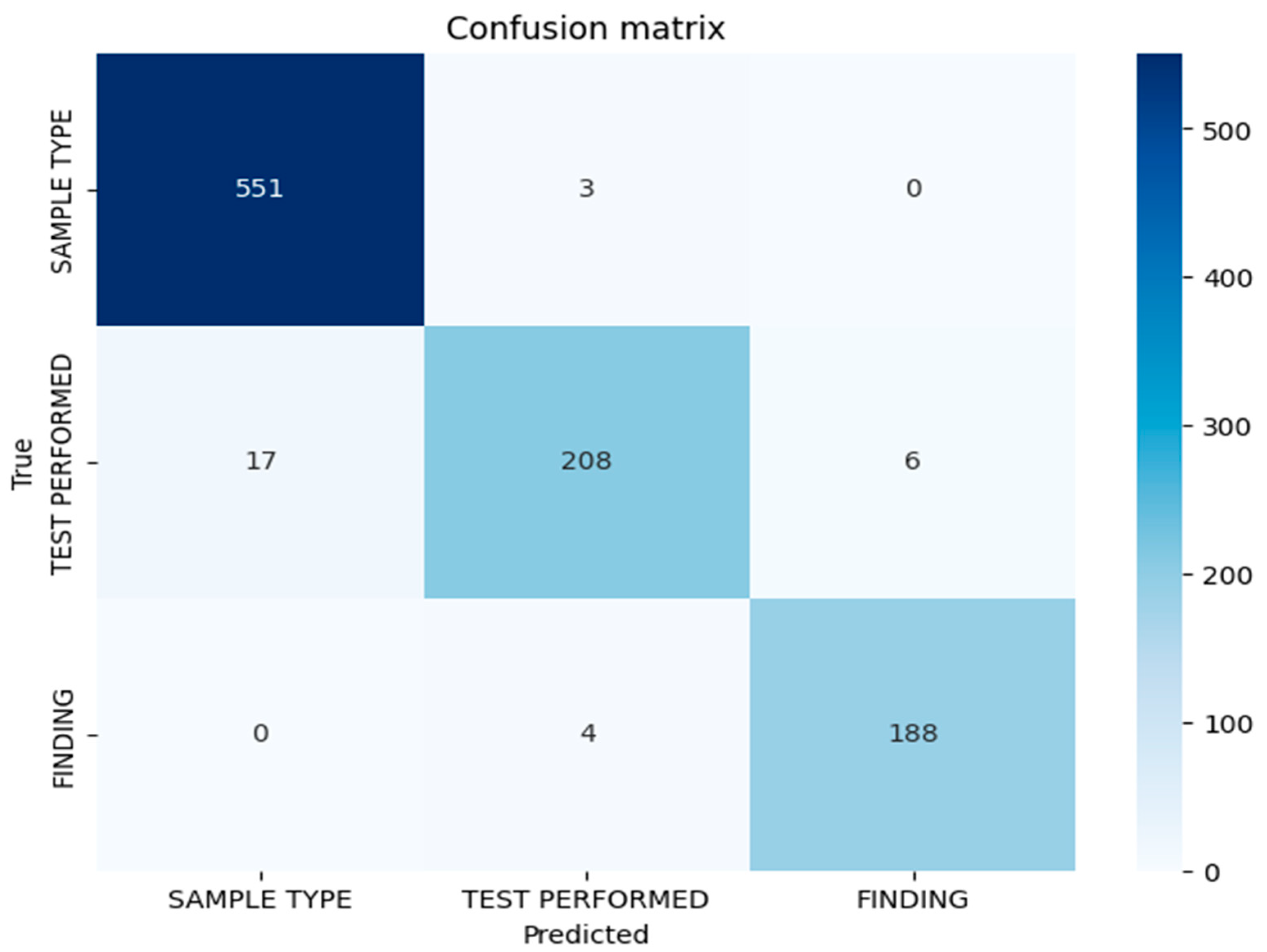

3.2. Confusion Matrix Analysis

Figure 1 represents the confusion matrix displaying the token-level classification results for the BioBERT model on the test set. The matrix demonstrates strong discrimination between entity classes, with minimal misclassification. The diagonal elements indicate correct classifications for each entity type, while the off-diagonal elements indicate misclassifications. The misclassification patterns reveal that the errors are primarily concentrated in the test performed entity category, suggesting lexical or contextual ambiguities in the procedural nomenclature descriptions in anatomopathological reports. The confusion matrix confirms the low cross-category confusion, indicating that the model effectively learns semantic distinctions between sample types, performed tests, and diagnostic findings.

3.3. Error Analysis by Entity Type

Table 3 presents the absolute and relative errors per entity for the BioBERT model. Test performed entities exhibited the highest error rate, with 16 misclassified tokens, resulting in a relative error rate of 6.9%. Sample type entities demonstrated a moderate level of difficulty, with 14 misclassified tokens and a relative error rate of 2.5%, reflecting the variability in the descriptions of anatomical specimens across reports. Finding entities showed very low error levels, with only two misclassified tokens and a relative error rate of 1%, indicating that the diagnoses are relatively consistent and easier to identify within the corpus. The diversity of terms and abbreviations used to describe specimens and procedures contributes to the classification challenges, particularly for test performed entities, where standardized terminology exists alongside institutional variations and procedural synonyms.

3.4. Confidence Intervals for Performance Metrics

Bootstrap estimation with 10,000 samples generated 95% CIs confirming robust performance stability, as presented in

Table 4. The precision demonstrated narrow confidence intervals (95% CI: 0.967–0.970), indicating high stability for this metric across the bootstrap resampling iterations. The recall exhibited slightly wider confidence intervals (95% CI: 0.900–0.995), reflecting variability in detecting certain entity instances, particularly for finding entities. The F1-score confidence intervals (95% CI: 0.933–0.982) showed intermediate width, balancing the stability of the precision with the variability of the recall measurements. The narrow intervals overall confirm that the observed performance represents stable model behavior rather than stochastic variation or overfitting to the particular test set composition.

3.5. Statistical Significance Testing Against Baseline

One-sample

t-tests comparing the model metrics against a baseline of 0.5 yielded extremely high t-statistics, as shown in

Table 5, with all the

p-values below 0.001. The t-statistics for precision, recall, and F1-score were 612.029, 15.71, and 30.24, respectively, confirming that the observed performance significantly exceeded the baseline thresholds with very high confidence. The exceptionally high t-statistic for the F1-score was driven by both high mean performance and low variance across the three entity types. The very low

p-values confirm that all the model metrics significantly exceed the 0.5 baseline, indicating that the observed performance is not due to chance. The t-statistics for precision, while very high, reflects the small entity sample size (n = 3), which amplifies test statistics when the variance is low. The recall and F1-score t-values remained elevated, with the magnitudes being more intuitive, reflecting slightly greater variability in these metrics across entities.

3.6. Descriptive Statistics Across Entity Labels

Table 6 presents the metric statistics by label, revealing consistent high performance across all the entity types. A mean precision of 0.969 and a standard deviation of 0.001 demonstrate minimal variability in the positive predictive value across the entity classes. A mean recall of 0.958 with a standard deviation of 0.050 indicates slightly higher variability, suggesting that certain entities, such as finding, pose greater detection challenges due to the lexical diversity and contextual variation in diagnostic descriptions. The mean F1-score of 0.963 with a standard deviation of 0.025 confirms the balanced performance between precision and recall. The low standard deviations indicate that the model consistently achieves high performance across all the labels, with stable precision and F1-scores throughout the entity taxonomy.

3.7. Multi-Ontology Standardization Descriptive Performance

Table 7 presents the descriptive performance metrics across four model configurations evaluated on 53 test samples: BioClinicalBERT only (without external knowledge), dense retrieval-augmented generation (transformer-based embeddings indexed with Facebook AI Similarity Search or FAISS), BioClinicalBERT + BM25 (sparse retrieval-augmented generation without dense embeddings), and our proposed Fusion/Reranker system (BioClinicalBERT + dense Retrieval-Augmented Generation).

For the SNOMED CT code mapping, BioClinicalBERT alone achieved an accuracy of 0.7547, a precision of 0.5881, a recall of 0.6667, and a macro-F1 of 0.6124. Dense-only retrieval-augmented generation demonstrated intermediate performance with an accuracy of 0.6981, a precision of 0.5833, a recall of 0.5960, and a macro-F1 of 0.5856. The configuration using BM25 sparse retrieval (BioClinicalBERT + BM25) showed reduced performance, with an accuracy of 0.5849, a precision of 0.5000, a recall of 0.4907, and a macro-F1 of 0.4944, highlighting the limitations of traditional sparse retrieval methods for this task. In contrast, our Fusion/Reranker system achieved the highest performance, with an accuracy of 0.7925, a precision of 0.6136, a recall of 0.6263, and a macro-F1 of 0.6159, representing an improvement over BioClinicalBERT alone.

For the LOINC classification, the performance was substantially higher across all the models, with Fusion/Reranker achieving an accuracy of 0.9811, a precision of 0.9216, a recall of 0.9412, and a macro-F1 of 0.9294. BioClinicalBERT alone showed an accuracy of 0.9434, a precision of 0.8284, a recall of 0.8824, and a macro-F1 of 0.8445. Dense-only retrieval-augmented generation performed exceptionally well, matching the accuracy of Fusion/Reranker at 0.9811, suggesting strong lexical matching for the LOINC codes. Further, it exhibited a precision of 0.9216, a recall of 0.9412, and a macro-F1 of 0.9284. The BM25 configuration achieved an accuracy of 0.9245, a precision of 0.7963, a recall of 0.8333, and a macro-F1 of 0.8056, demonstrating that while BM25 performs reasonably for LOINC, our dense retrieval approach provides a performance improvement.

For the ICD-11 mapping, Fusion/Reranker achieved an accuracy of 0.8491, a precision of 0.7115, a recall of 0.7500, and a macro-F1 of 0.7201, compared to BioClinicalBERT’s accuracy of 0.7925, precision of 0.6623, recall of 0.7171, and macro-F1 of 0.6772. Dense-only retrieval-augmented generation showed the same accuracy as BioClinicalBERT at 0.7925 but had a lower macro-F1 of 0.6583. The precision and recall yielded values of 0.6500 and 0.6875, respectively. The BM25 configuration achieved an accuracy of 0.8113 and a macro-F1 of 0.6880, showing modest improvement over BioClinicalBERT alone but remaining inferior to our Fusion/Reranker system, with a precision of 0.6813 and a recall of 0.7125.

These results demonstrate three key findings: (1) traditional sparse retrieval (BM25) degrades performance compared to BioClinicalBERT alone for SNOMED CT, highlighting its inadequacy for this task; (2) our dense retrieval approach consistently outperforms BM25 across all the terminologies; and (3) the Fusion/Reranker architecture provides the optimal combination, achieving consistent superiority across all three medical terminologies while emphasizing the critical importance of dense embeddings over sparse alternatives.

3.8. Agreement Measures for Model Predictions

Table 8 presents the Cohen’s Kappa and Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) values for all the model configurations. For SNOMED CT, Fusion/Reranker achieved strong agreement (Kappa = 0.7829, MCC = 0.7885), outperforming BioClinicalBERT alone (0.7423/0.7511) and dense-only retrieval-augmented generation (0.6871/0.6998). The BM25 sparse retrieval configuration exhibited the lowest agreement (0.5751/0.5910), highlighting the limitations of traditional retrieval methods.

For LOINC, both Fusion/Reranker and dense-only retrieval-augmented generation (0.9773/0.9777) achieved near-perfect agreement, while BioClinicalBERT demonstrated high agreement (0.9318/0.9338). The BM25 configuration remained strong (0.9093/0.9124) but was inferior to the dense approaches.

For ICD-11, Fusion/Reranker showed substantial agreement (0.8435/0.8457), surpassing BioClinicalBERT (0.7840/0.7878) and dense-only retrieval-augmented generation (0.7856/0.7891). The BM25 configuration demonstrated moderate improvement over BioClinicalBERT alone (0.8049/0.8078) but remained below Fusion/Reranker.

These results confirm the following: (1) BM25 consistently underperforms compared to dense retrieval; (2) dense retrieval excels for standardized codes (LOINC) but requires fusion for complex mappings (SNOMED CT); and (3) Fusion/Reranker provides optimal agreement across all the terminologies.

3.9. Statistical Comparison Between Model Architectures

Table 9 presents statistical comparisons between the models using McNemar’s test and permutation testing. For SNOMED-CT, Fusion/Reranker showed a non-significant improvement over BioClinicalBERT alone (McNemar

p = 0.500, Perm

p = 0.491), with an accuracy difference of 0.0378, but significantly outperformed BM25 sparse retrieval (McNemar

p = 0.0005, Perm

p = 0.0002), with an accuracy difference of 0.2075.

For LOINC, Fusion/Reranker exhibited non-significant improvements over both BioClinicalBERT alone (McNemar

p = 0.625) and the BM25 configuration (McNemar

p = 0.250). For ICD-11, Fusion/Reranker demonstrated non-significant improvements over BioClinicalBERT alone (McNemar

p = 0.375) and BM25 (McNemar

p = 0.500). Further data and statistics are reported in

Table 9.

All the McNemar p-values comparing BioClinicalBERT to Fusion/Reranker exceeded 0.375, indicating insufficient evidence for statistical superiority. This could be due also to the relatively small sample size (n = 53). However, the BM25 vs. Fusion/Reranker comparison for SNOMED-CT showed clear statistical significance (p < 0.001), demonstrating the superiority of dense embeddings over sparse retrieval for complex medical code mapping.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that BioBERT-based named entity recognition, combined with BioClinicalBERT and retrieval-augmented generation, achieves strong performance in automated extraction and multi-ontology standardization of anatomopathological report entities. The hybrid architecture achieved excellent F1-scores as well as mean precision and recall, as confirmed by the bootstrap CIs and statistical significance testing, demonstrating performance substantially exceeding the baseline thresholds. Multi-ontology standardization demonstrated substantial to near-perfect agreement across the SNOMED CT, LOINC, and ICD-11 terminologies, with particularly high performance for the LOINC laboratory test mapping. While retrieval-augmented generation provided descriptive performance improvements across all the tasks, with consistent gains in the accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-scores, statistical testing revealed non-significant differences given the current sample size of 53 test instances, indicating that larger validation studies are necessary to establish augmentation benefits with adequate statistical power definitively. The system demonstrates preliminary practical feasibility for reducing the manual coding burden, improving the data quality, and enhancing the semantic interoperability across healthcare institutions. However, several critical steps remain before clinical deployment can be recommended. Multi-institutional validation studies across diverse geographic regions, languages, and pathology subspecialties are essential to assess the generalizability and identify potential performance degradation scenarios when encountering different documentation styles, terminology preferences, and case mix patterns. A prospective evaluation comparing automated coding with expert pathologist annotations in real-world workflow conditions would quantify the accuracy, identify failure modes, and establish quality assurance protocols for clinical integration. Integration with existing laboratory information systems and electronic health record platforms requires attention to computational efficiency, latency constraints, inference scalability, and failure mode handling to ensure reliable operation in production environments without disrupting clinical workflows. Human-in-the-loop workflows with confidence-based routing to manual review can maintain quality standards while maximizing automation benefits, optimizing the balance between efficiency gains and clinical safety through adaptive thresholding based on validation studies.

Future research directions include expansion to multilingual pathology corpora enabling cross-linguistic model transfer through multilingual BERT variants, incorporation of multimodal data such as structured report sections and histopathological images for comprehensive diagnostic coding, hierarchical code prediction exploiting the terminology structure and semantic relationships to improve rare code detection, active learning approaches to continuously improve performance with minimal annotation burden through intelligent sample selection, and federated learning frameworks enabling collaborative model development across institutions while preserving data privacy and regulatory compliance. The demonstrated technical feasibility, combined with the straightforward clinical utility for improved data standardization, enhanced research capabilities, reduced coding costs, and better interoperability, motivates continued development toward robust, validated systems supporting pathology informatics infrastructure in modern healthcare systems, ultimately advancing the transformation of unstructured clinical narratives into actionable structured knowledge, supporting evidence-based medicine, precision health initiatives, and data-driven clinical decision support.