Abstract

Drought is expected to intensify under climate change, posing significant risks to Mediterranean agroecosystems. This study provides long-term projections of drought and wetness conditions for three representative Mediterranean regions—Eastern Mancha (Spain), Sidi Bouzid Governorate (Tunisia), and the Beqaa Valley (Lebanon)—to support climate-resilient planning. Future monthly precipitation (2020–2050) was dynamically downscaled using the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model under the RCP4.5 scenario, and the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI12) was subsequently applied to quantify drought severity at annual and monthly scales. By integrating dynamically downscaled WRF projections with pixel-based SPI analysis across three spatially distinct Mediterranean regions, the study provides a novel, spatially explicit and comparative framework for assessing future drought and wetness extremes in support of climate-resilient planning. The results reveal spatial variability and moderate temporal fluctuations across the three regions, reflected in differing timings and intensities of their driest and wettest hydrological years. Spain is projected to experience its driest hydrological year in 2046–2047, Tunisia in 2030–2031, and Lebanon in 2047–2048. The wettest years are projected to occur in 2045–2046 for Spain and Tunisia, and in 2028–2029 for Lebanon. Although extreme drought events are not widely anticipated, localised severe dry periods emerge in many parts of the study areas. while in Lebanon, these conditions also extend into the winter and spring. These findings underscore the need for spatially targeted adaptation rather than uniform regional measures. Identifying both driest and wettest projected years enhances preparedness, informs water-resource optimisation, and supports agricultural land-use planning, especially in areas with favourable future climatic conditions. Integrating drought projections into multi-hazard planning (i.e., drought and floods) frameworks can further strengthen territorial resilience in regions facing increasing climate-related extremes.

1. Introduction

Drought is considered a major environmental hazard that is expected to become more frequent and intense under climate change, affecting many regions worldwide [1]. Although there is no universal definition of drought, the phenomenon is generally characterised by a moisture deficit over a specific period relative to normal conditions [2]. Climate variability and anomalies (often linked to large amounts of carbon dioxide emissions from human activities) may lead to meteorological drought; extensive land-use changes can contribute to soil moisture drought, which may be exacerbated by unsustainable irrigation practices. Meanwhile, dam construction may induce hydrological drought, further intensified by excessive water abstraction. Collectively, these processes culminate in severe socioeconomic and ecological impacts [3].

The impacts of drought are multifaceted, influencing numerous environmental and socioeconomic dimensions. An important consequence relates to agriculture, where drought may significantly reduce crop productivity; for instance, corn yields may decline by up to 8% for every week of extreme drought [4]. Another notable example is that drought is considered responsible for 50% of cereal losses in India from 1982 to 2012 [5]. Extreme drought also contributes to water insecurity in many regions [6] and can deteriorate water quality by increasing groundwater salinity [7] or promoting harmful cyanobacterial blooms in surface waters [8]. Furthermore, drought may substantially impact hydropower generation, causing reductions of 20–40% every decade, with serious implications for national economies and the energy sector [9,10]. A fundamental concern related to climate change is that more frequent and severe droughts can trigger intense wildfires, threatening critical natural and built environments [11], and necessitating enhanced resilience [12].

Historical drought assessments provide valuable indications of drought vulnerability and are supported by several indices, such as the Standardized Evapotranspiration Deficit Index (SEDI) [13], the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) [14], and the Standardized Precipitation Evaporation Index (SPEI) [15]. However, projections of future drought conditions also play a critical role in enhancing the preparedness and resilience of agroecosystems. To this end, numerous studies have investigated future drought under General Circulation Models (GCMs) and Regional Climate Models (RCMs) [16], the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) [17], or differentiated Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs), indicating that drought hazards are expected to intensify, affecting an increasing proportion of the population, particularly in developing countries [18].

Recent research indicates that agricultural and hydrological drought events intensified across the Mediterranean from 1980 to 2014, while near-future projections suggest a further increase in drought frequency of up to 25% by 2060. The same study highlighted that the southern Mediterranean is expected to be the most critically affected region, with significant impacts on food and water resources; however, the spatial manifestation of drought remains strongly influenced by regional climatic characteristics [19]. In the same context, the severity of meteorological and hydrological drought is projected to escalate due to the synergistic effects of declining precipitation and rising evapotranspiration [20] while agricultural drought is expected to strongly affect low-elevation coastal agricultural regions [21].

Hence, the main aim of this study is to explore the spatiotemporal projections of drought extremes in three distinct vulnerable Mediterranean regions—Spain, Tunisia, and Lebanon. The study makes a novel contribution to the literature by addressing several key aspects. First, based on previous historical monitoring of drought and wetness patterns in these regions, this analysis is extended to future conditions up to 2050. Second, the combination of two robust methodological approaches provides significant insights into the spatial and temporal patterns of dry and wet periods at a pixel-based scale. The Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model is used to project future monthly precipitation, which forms the basis for calculating the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) and identifying spatial and temporal drought and wetness extremes. This information is critical for identifying subregions at high drought risk and for informing appropriate planning measures. Notably, the authors of [22] concluded that drought severity, rather than frequency or duration, is associated with higher financial costs. Finally, the methodology is applied across three spatially distinct domains, enabling the identification of climatic differences and similarities among Mediterranean countries. This integrated, multi-domain WRF–SPI framework applied across three Mediterranean agroecosystems provides a novel, spatially explicit assessment of future drought extremes.

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Study Areas

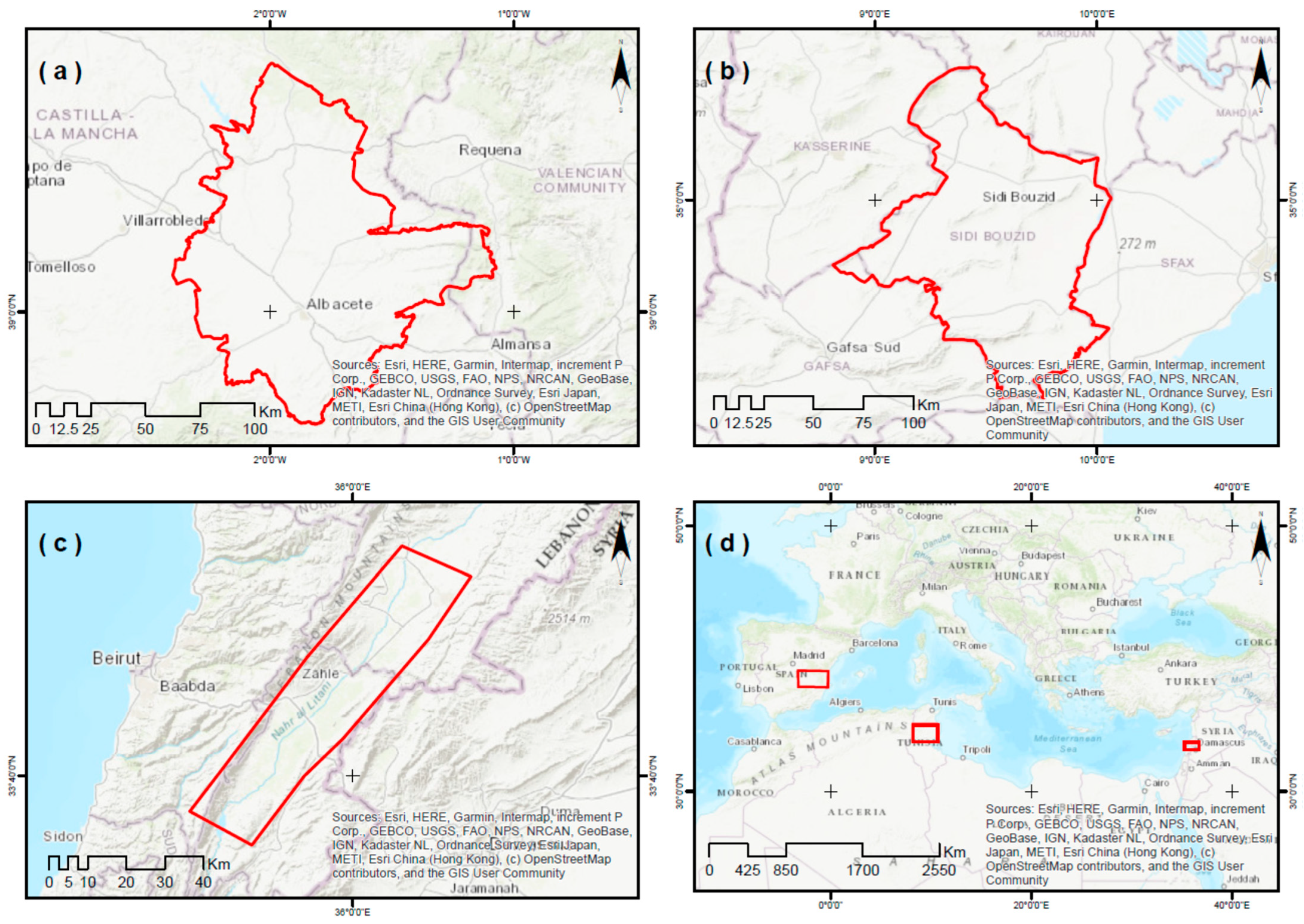

Drought analysis was conducted across three regions that reflect diverse characteristics of Mediterranean environments (Figure 1). The first case study concerns the Hydrogeological Unit “Eastern Mancha”, situated mainly within Albacete province in the region of Castilla-La Mancha, southeastern Spain. This area covers 8500 km2 and includes more than 110,000 hectares of irrigated farmland, with a population density of approximately 150 inhabitants per km2. Its central coordinates are 38°59′ N and 1°51′ W [23]. The climate consists of short, hot summers and long, notably cold winters, with a mean annual temperature of 14.6 °C and typical values ranging from 0.5 to 33.3 °C. Annual precipitation averages 360 mm, and mean wind speeds reach 14.5 km/h [24].

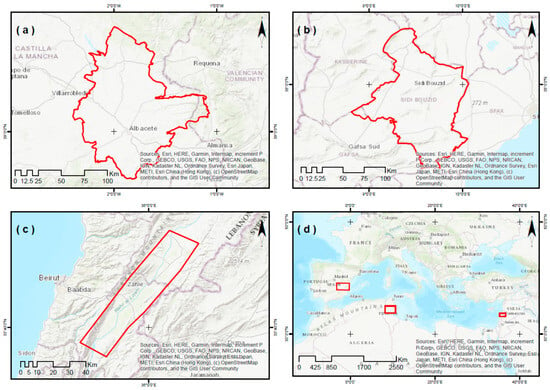

Figure 1.

Spatial extent of the three study areas (a) Eastern Mancha (Spain), (b) Sidi Bouzid (Tunisia), and (c) the Beqaa Valley (Lebanon) and (d) their overall distribution across the Mediterranean region.

The second study area is the Sidi Bouzid Governorate in central Tunisia, one of the country’s 24 administrative regions. It covers 7405 km2, with a recorded population of 429,912 in 2014, corresponding to a density of 58 inhabitants per km2. Its coordinates are 35°02′ N and 9°30′ E [25]. The climate is marked by very hot summers and prolonged cold winters, with temperatures ranging from 4.4 to 36.6 °C. The region receives an average of 248 mm of rainfall per year, and mean wind speeds are approximately 13.7 km/h [26]. Groundwater constitutes the sole source of irrigation in this governorate.

The third study region lies within Lebanon’s Beqaa Valley, a major agricultural corridor extending roughly 120 km in length and 16 km in width, centred around 34°00′ N and 36°08′ E. The valley experiences a continental Mediterranean climate, characterised by wet and frequently snowy winters and dry, warm summers [27]. Temperatures typically fluctuate between 3 °C and 34 °C, while annual rainfall varies from about 230 mm in the northern sector to 610 mm in central areas. Mean wind speeds average near 7 km/h [28].

These three regions were selected based on the following criteria [27]:

- All study areas are located within the broader Mediterranean basin.

- Their contrasting geographical settings—as representatives of Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East—enhance the likelihood of observing marked differences in drought and wetness conditions.

- A considerable geographical separation between sites ensures that local atmospheric and environmental variability can be adequately captured.

- The current analysis extends the historical drought/wetness assessment of the same regions from 1980 to 2050.

Together, these parameters allow for a comparative assessment of future spatiotemporal meteorological patterns and climatic extremes (e.g., precipitation variability, drought, and wetness). They also support the interregional evaluation of the four fundamental dimensions of drought—severity, frequency, spatial extent, and duration—that are recognised as key components of one of the most impactful environmental hazards [27].

2.2. Weather Research and Forecasting Modelling (WRF)

The Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model is a mesoscale numerical weather prediction (NWP) system widely employed for atmospheric research and operational forecasting [29]. Developed through collaboration between NCAR, NOAA, and the U.S. Air Force, and currently maintained by UCAR, WRF provides an open-source framework suitable for real-time forecasting as well as regional climate simulations [30].

WRF includes two dynamical cores—the Advanced Research WRF (ARW) and the Nonhydrostatic Mesoscale Model (NMM)—each tailored to different modelling applications. The model supports a broad suite of physical parameterisation options, including microphysics, cumulus convection, planetary boundary layer processes, land-surface schemes, and shortwave/longwave radiation. These options allow users to configure simulations according to their specific research needs.

The Weather Research and Forecasting model, using the Advanced Research WRF (ARW) core (version 4.2) [29,31], was utilized to provide the necessary climate variables for the SPI analysis over the regions of interest. The model was configured accordingly to provide a high resolution 30-year climate simulation forced by CMIP5 CESM data under emissions scenario RCP4.5 [32]. The choice of the forcing data was based on the available CMIP5 data, as no CMIP6 data was available by the time of producing the 30-year climate simulation. In addition, the RCP4.5 scenario was selected to represent an intermediate, stabilisation-oriented climate pathway that has been widely applied in Mediterranean drought research [33,34] and is broadly comparable to the SSP2-4.5 scenario adopted in AR6 in terms of radiative forcing trajectories. Given the substantial uncertainties associated with long-term climate projections, the use of an intermediate forcing scenario provides a balanced representation of future climatic conditions, avoiding reliance on either low-end or high-end projections while remaining suitable for comparative, planning-oriented drought assessments.

A parent domain covering the broader Mediterranean basin with horizontal resolution of 18 km x 18 km (340 × 210 grid points) was considered, while three one-way nested domains, each focusing on one study region (Eastern Mancha, Spain; Sidi Bouzid, Tunisia; Beqaa Valley, Lebanon) were configured with horizontal resolution of 6 km × 6 km (139 × 139 grid points). For vertical resolution, 50 sigma levels up to 50 hPa were employed.

The simulated period spanned from 2020–2050 (30 years), while the years 2018–2019 were used as spin-up time and were excluded from the analysis. The simulations were carried out on the HPC cluster of the 3DSA on MPI communication mode and at monthly time slices due to the demanding amount of computational and storage resources. In total, approximately 210 days were needed for the completion of the 30-year climate simulation.

All drought statistics (SPI) and the reported 5 × 5 km pixels were computed on a regular lat-lon grid of the inner nests. The precipitation model output used for SPI is provided on a regular lat/lon grid with coordinate increments of approximately 0.045° (lat) × 0.058° (lon) (5 km at the study latitudes), which was created by conservative remapping of the native 6 km × 6 km WRF inner grids. This conservative remapping was applied to ensure spatial consistency and comparability between the future SPI fields derived from WRF and the historical SPI analyses based on CHIRPS precipitation data, thereby supporting a coherent interpretation of drought conditions from historical to future periods.

This procedure enabled consistent, continuous dynamic downscaling across the full projection period and provided the monthly precipitation fields used for subsequent SPI estimation.

2.3. Standardized Precipitation Index

Future drought and wet conditions were assessed using the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI), a widely applied metric for identifying both dry and wet periods across multiple temporal scales [35,36]. The SPI quantifies anomalies in accumulated precipitation by comparing observed values with the long-term climatological distribution. For each timescale (SPI-3, SPI-6, SPI-12, SPI-48), precipitation totals are fitted to a gamma probability distribution, which was then transformed into a standard normal distribution such that SPI values have a mean of zero and can be compared across regions with different climates [37].

The estimation of the SPI follows a standardised procedure. If the x-axis denotes the accumulated precipitation over the selected time scale (e.g., 1, 3, 6 or 12 months), the distribution of these values can be modelled using a gamma (Γ) probability density function, g(x), expressed as [38]:

where g(x) represents the gamma function. In Equation (1a,b), the parameters α and β are estimated using the maximum likelihood method, as shown below:

where n denotes the number of observations in the precipitation time series (total months). The corresponding precipitation value x can then be expressed in terms of its cumulative probability:

Substituting t = x/b into Equation (3) transforms it into a gamma function:

In cases where the accumulated monthly precipitation x is zero, Equation (4) is adjusted accordingly and expressed as H(x).

where q denotes the probability of zero precipitation (x = 0), which reflects the frequency of zero-rainfall events within the entire time series. The SPI is then obtained by transforming this cumulative probability using the standard normal distribution function, as shown below.

assuming the constants c0 = 2.51552, c1 = 0.80285, c2 = 0.01033, d1 = 1.43279, d2 = 0.18927, and d3 = 0.00131.

A standard classification scheme (Table 1) was applied to categorise drought/wetness severity (e.g., moderately dry, severely dry, extremely dry), which was adopted from the European Drought Observatory [39].

Table 1.

SPI classification table adjusted from [39].

In the next stage, wet and dry conditions were assessed for each hydrological year (October to September). Although the SPI3 and SPI6 capture seasonal precipitation variability, the SPI12 is preferred for hydrological planning applications as it better represents annual water balance conditions relevant to agricultural productivity and groundwater resource management in Mediterranean agroecosystems. For this purpose, the SPI12 was selected, as its longer accumulation period allows for the identification of prolonged drought episodes that may influence both surface and groundwater resources. This procedure enabled us to derive annual average drought or wetness characteristics based on the corresponding SPI values.

The SPI12 was computed at each WRF grid cell from monthly precipitation totals using a 12-month moving accumulation. For each grid cell, accumulated precipitation was fitted to a gamma distribution and subsequently transformed to a standard normal variate, yielding the SPI12. In the present study, the hydrological year was defined as October–September. Therefore, the SPI12 value assigned to a given hydrological year corresponds to the September SPI12, which represents the precipitation accumulation over the preceding 12 months (October–September). For annual mapping of the driest and wettest hydrological years, we present the monthly SPI12 values within each hydrological year, all derived from the same rolling 12-month accumulation window.

The outcomes are illustrated through a series of maps depicting the most extreme wet and dry years across the three study regions. The SPI12 was computed directly from gridded WRF precipitation at each model grid cell (native 5 km grid). For spatial representation and area-based summaries within the irregular boundaries of the study regions, we generated Voronoi polygons [40] from the WRF grid-cell centroids, clipped them to each study area, and attributed each polygon with the SPI value of its corresponding grid cell. This procedure provides a complete areal representation within each study region and enables the computation of areal fractions (percent coverage) of SPI classes. It is not a station-based interpolation workflow, and no meteorological station data were used for SPI estimation.

3. Results

This section presents the SPI12 results for all the study areas for the projected period 2020–2050, based on precipitation outputs from the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model. The WRF simulations provided future monthly precipitation values, which were then used to calculate the SPI12. Assessing the future evolution of drought conditions enables a better understanding of potential long-term dry periods and supports the development of proactive measures to mitigate the impacts of exceptionally dry years.

3.1. Prognostic Model for Estimating Potential Drought Conditions in Albacete, SE Spain (2020–2050)

The WRF provided the projected precipitation values for each month in Albacete from 2020 to 2050. Table 2 presents the monthly evolution of the SPI12 for the projected time frame (2021–2049). As shown, the driest hydrological year is projected to occur in 2046–2047 (SPI = −1.24), whereas the wettest hydrological year is projected one year earlier, in 2045–2046 (SPI = 1.62). The projected SPI values indicate that extreme drought conditions are not expected in Albacete up to 2050.

Table 2.

Monthly evolution of the SPI12 for the projected time frame (2021–2049).

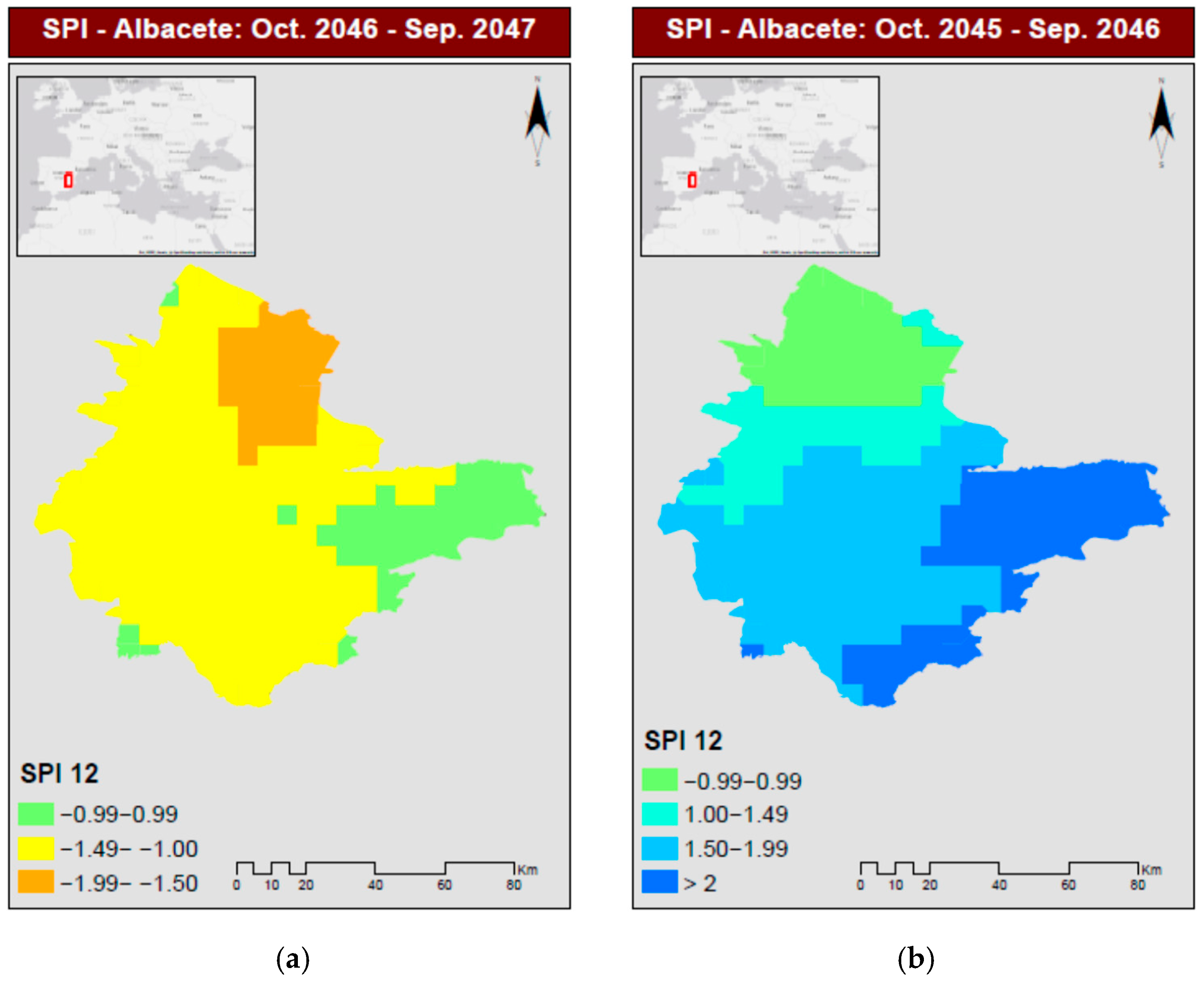

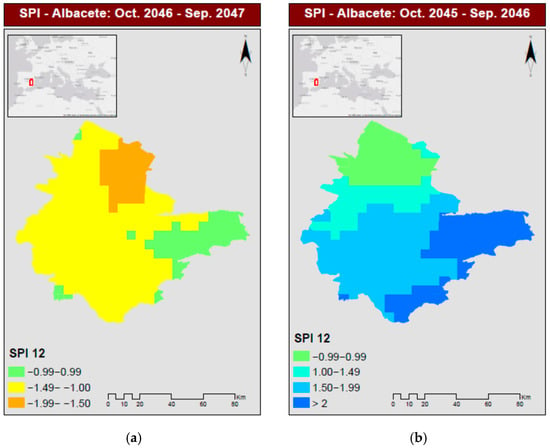

During the entire projected period, attention was given to the driest and wettest hydrological years. In this context, the spatial distribution of drought and wetness categories was mapped to enable decision makers to implement spatially explicit measures in the regions at highest risk, rather than applying uniform management strategies. This approach supports the efficient allocation of financial and environmental resources. Figure 2a illustrates the distribution of drought categories in Albacete during the driest hydrological year (2046–2047). Most of the study area experiences moderate drought (−1.49 < SPI < −1), particularly in the central and western regions, while a smaller area in the northeast is projected to experience severe drought (−1.99 < SPI < −1.5). A small area in the east is characterised by normal conditions (−0.99 < SPI < 0.99).

Figure 2.

(a). SPI12 in Albacete (October 2046–September 2047). (b). SPI12 in Albacete (October 2045–September 2046).

Conversely, the hydrological year of 2045–2046 is projected to be the wettest (Figure 2b). Here, Albacete is divided into four distinct zones. The northern part presents normal conditions (−0.99 < SPI < 0.99). The adjacent zone to the south displays wetter conditions (1 < SPI < 1.49). The central and southwestern parts show even wetter conditions (1.5 < SPI < 1.99), while the wettest region is located in eastern Albacete (SPI > 2).

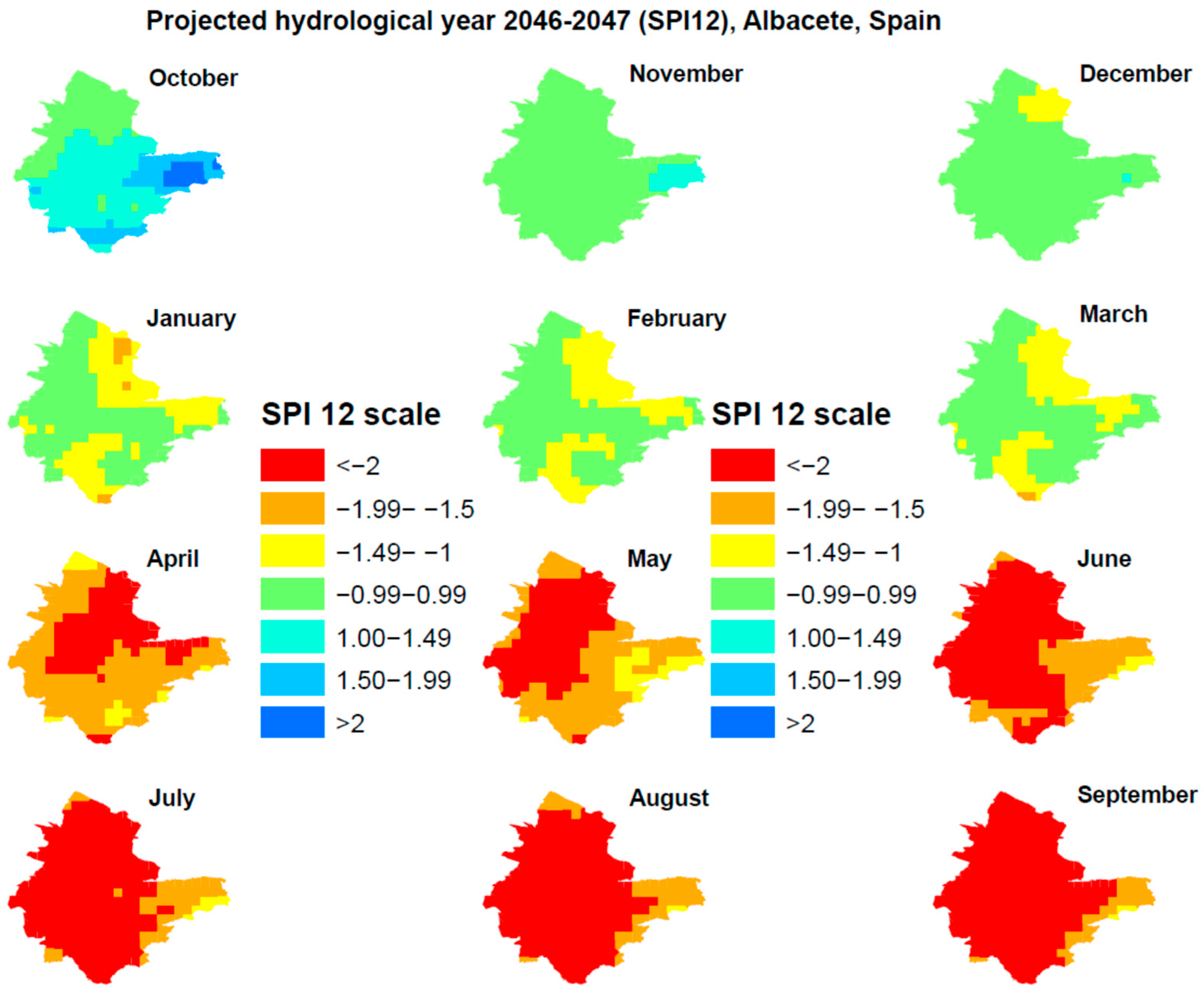

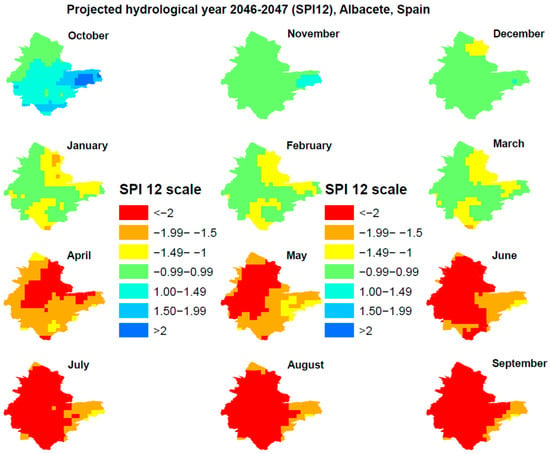

Next, an intra-annual analysis was conducted to explore the spatiotemporal evolution of drought and wetness trends throughout the two most extreme hydrological years. Figure 3 presents the monthly SPI12 evolution for 2046–2047 (driest year). At the beginning of this hydrological year (October–December), normal and wet conditions prevail across most of Albacete. Specifically, the central, southern, and eastern areas experience various degrees of wetness in October, while the northern part remains under normal conditions. November and December are predominantly characterised by normal conditions. From January to March, two diagonally opposite regions—located in the northeastern and southwestern parts of the study area—begin to experience moderate drought. However, almost the entire region is projected to face extreme drought (SPI < −2) from June to September, with the exception of a small area in the east exhibiting moderate drought. Conditions in April and May are less severe, with approximately three-quarters of Albacete experiencing moderate to severe drought but not extreme levels. Certain northern regions, however, do experience extreme drought.

Figure 3.

Monthly SPI12 in Albacete, Spain (projected hydrological year: 2044–2045).

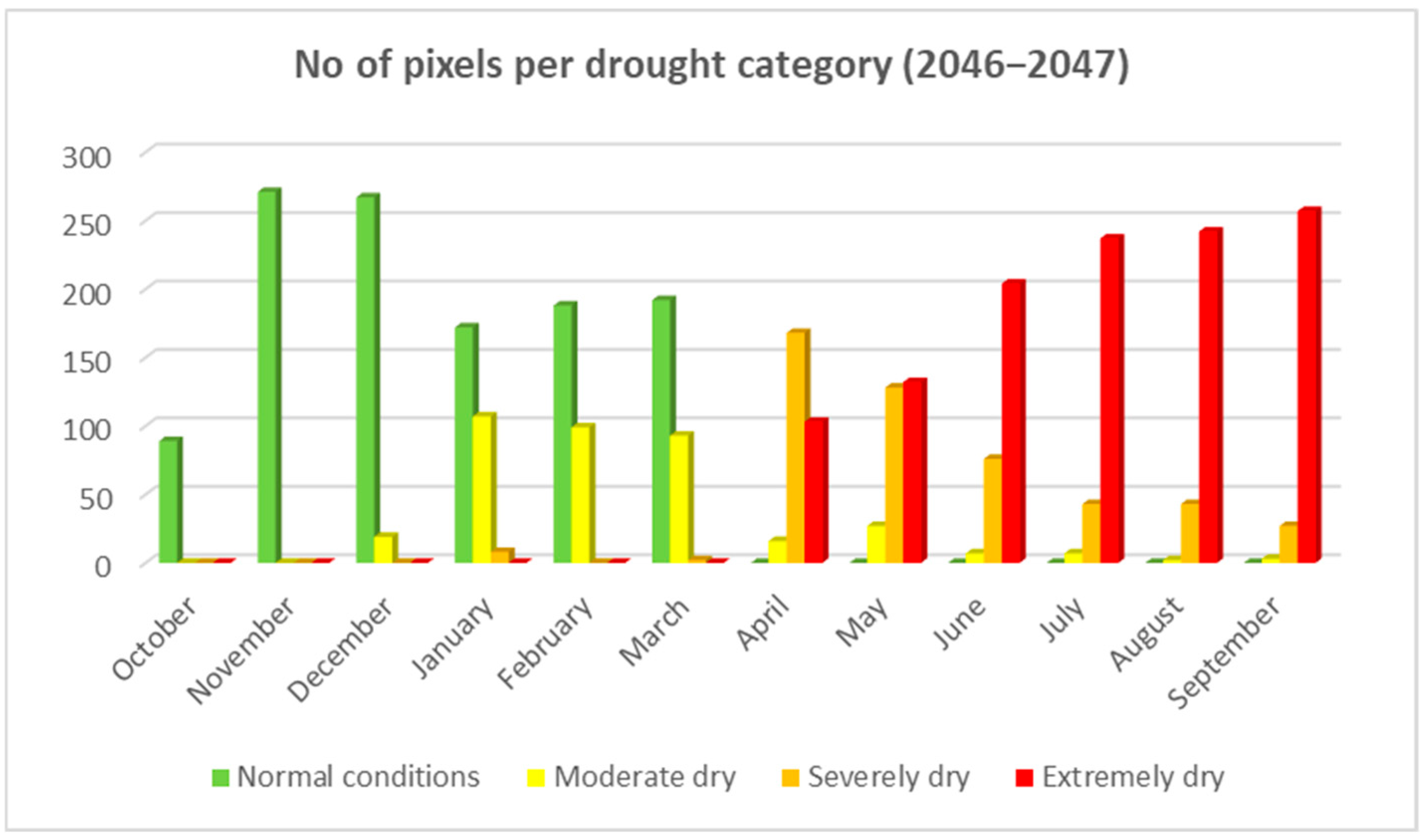

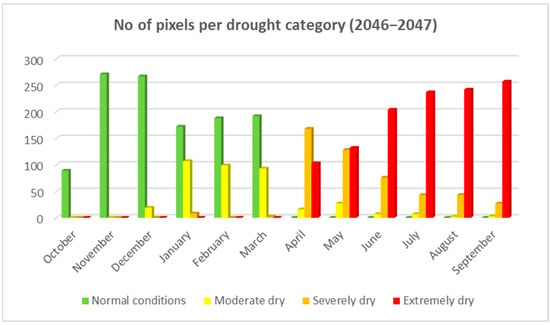

Figure 4 summarises the drought conditions in Albacete for the projected hydrological year of 2046–2047 in terms of the proportion of pixels falling into different categories. The pattern is highly variable. From October to March, many areas experience normal or moderate drought conditions, while an escalating shift towards severe and extreme drought is observed from April to September. Extreme drought expands progressively across Albacete toward the summer months.

Figure 4.

Number of pixels per drought category in Albacete (2046–2047).

Table 3 shows the percentage of pixels (5 × 5 km) falling into each drought category, allowing for the quantification of the spatial extent of each condition. Extensive areas (15–90%) experience severe or extreme drought between April and September. Approximately one-third of the study area faces moderate drought from January to March. Normal or wet conditions prevail between October and December (31–93%).

Table 3.

Percentage contribution of pixels falling into different levels of drought in Albacete (2046–2047).

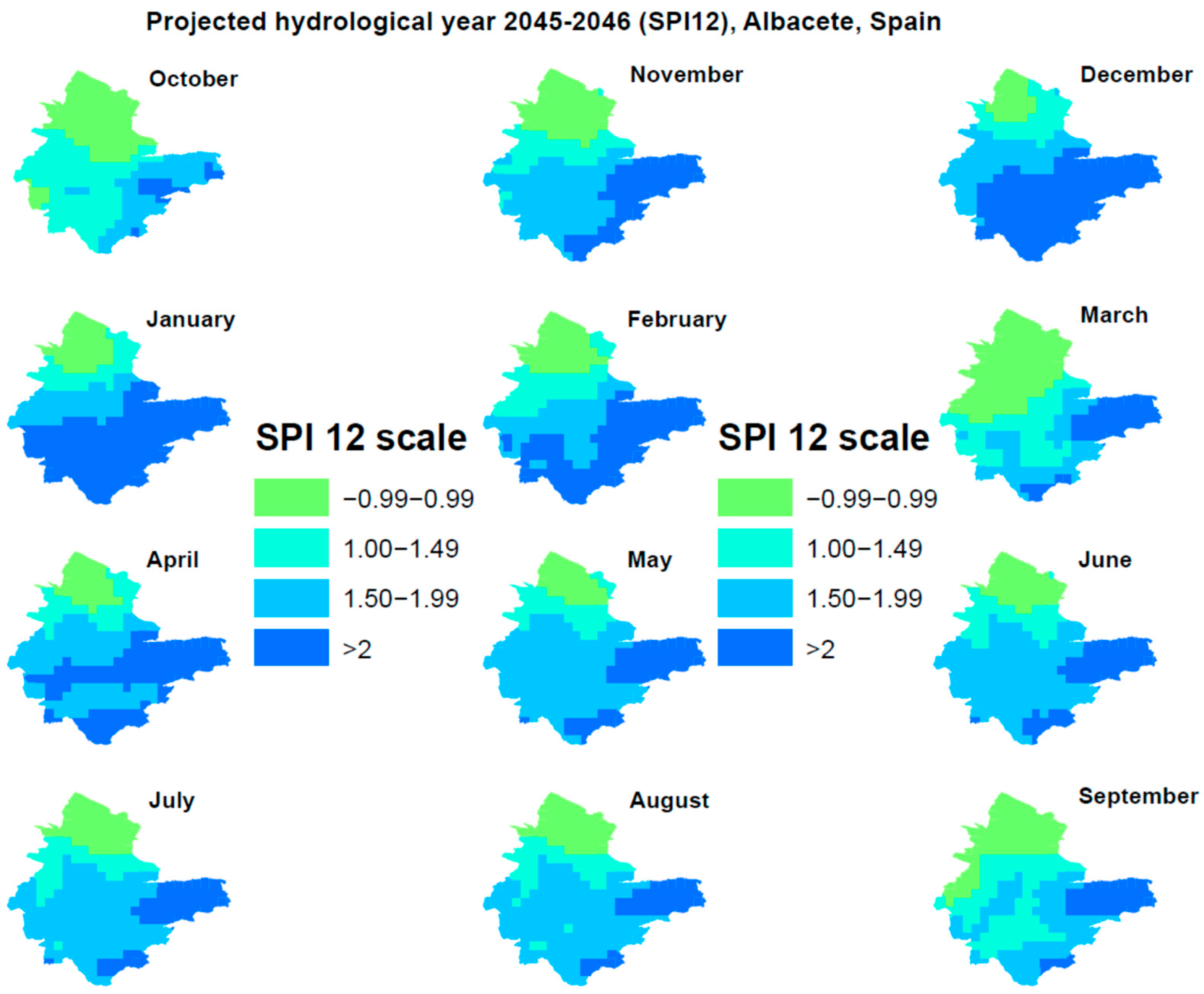

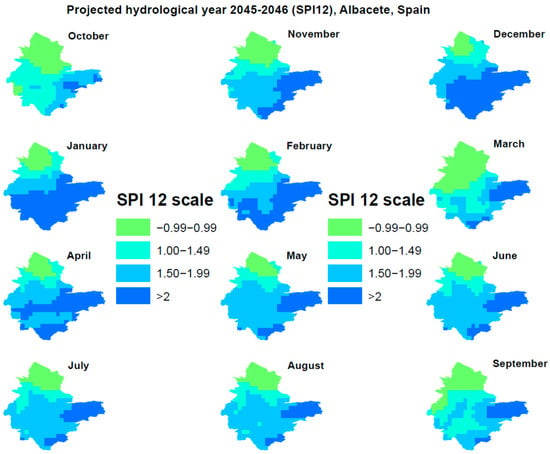

Figure 5 illustrates the monthly SPI12 evolution for 2045–2046 (wettest hydrological year). The study domain is again divided into four zones. The wettest conditions are concentrated in the eastern and southern regions (SPI > 2). The central part of Albacete is characterised by slightly less wet conditions (1.5 < SPI < 2). Moving northwards, conditions become progressively drier, with the intermediate zone showing mild wetness (1 < SPI < 1.5) and the northernmost regions approaching normal conditions. This spatial pattern is consistent throughout the year, with only slight variations in the extent of each wetness category.

Figure 5.

Monthly SPI12 in Albacete, Spain (projected hydrological year: 2045–2046).

3.2. Prognostic Model for Estimating Potential Drought Conditions in Sidi Bouzid Governorate, Tunisia (2020–2050)

The WRF provided the projected precipitation values for each month in Tunisia from 2020 to 2050. Accordingly, Table 4 presents the monthly evolution of SPI12 for the projected period (2021–2049). As shown, the driest hydrological year is projected to be 2030–2031 (SPI = −1.44), while the wettest is projected to be 2045–2046 (SPI = 2.15). Most of the remaining years are expected to be characterised by normal conditions (−0.99 < SPI < 0.99), with only a few exceptions.

Table 4.

Monthly evolution of SPI12 in Sidi Bouzid Governorate (Tunisia) for the projected time frame (2021–2049).

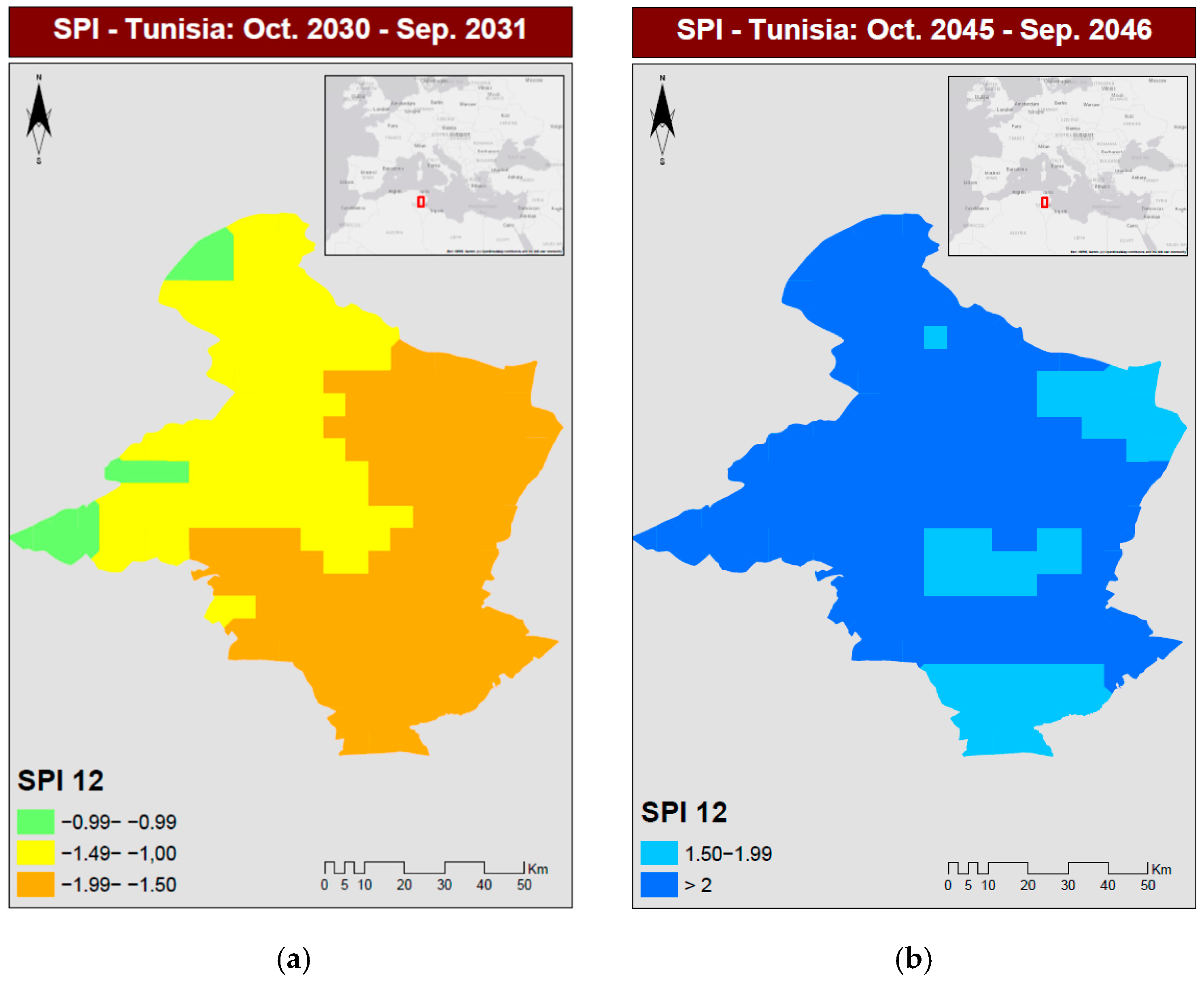

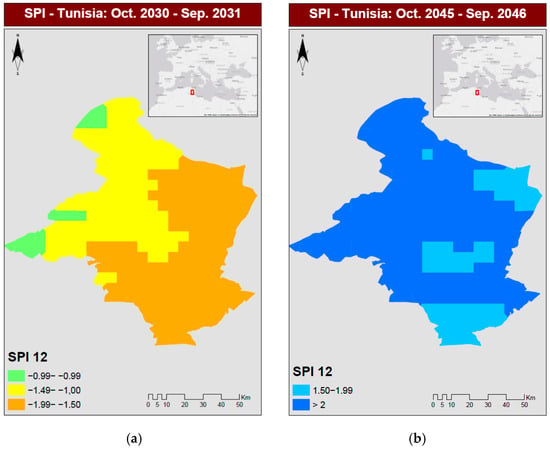

Throughout the projected period, the spatial distribution of drought and wetness categories was mapped for the two most extreme hydrological years. The driest year is projected to be 2030–2031 (Figure 6a). The study domain can be divided into two primary regions with escalating drought severity. The southeastern part is characterised by severe drought (−1.99 < SPI < −1.5), while the northwestern region experiences less severe, moderate drought (−1.49 < SPI < −1). Only a few areas in the north and west exhibit normal conditions.

Figure 6.

(a). SPI12 in Tunisia (October 2030–September 2031). (b). SPI12 in Tunisia (October 2045–September 2046).

Conversely, the wettest hydrological year is projected to be 2045–2046. Most of the study area is expected to experience extremely wet conditions (SPI > 2), whereas several regions in the southern, central, and eastern parts of the domain present slightly lower levels of wetness (1.5 < SPI < 1.99) (Figure 6b).

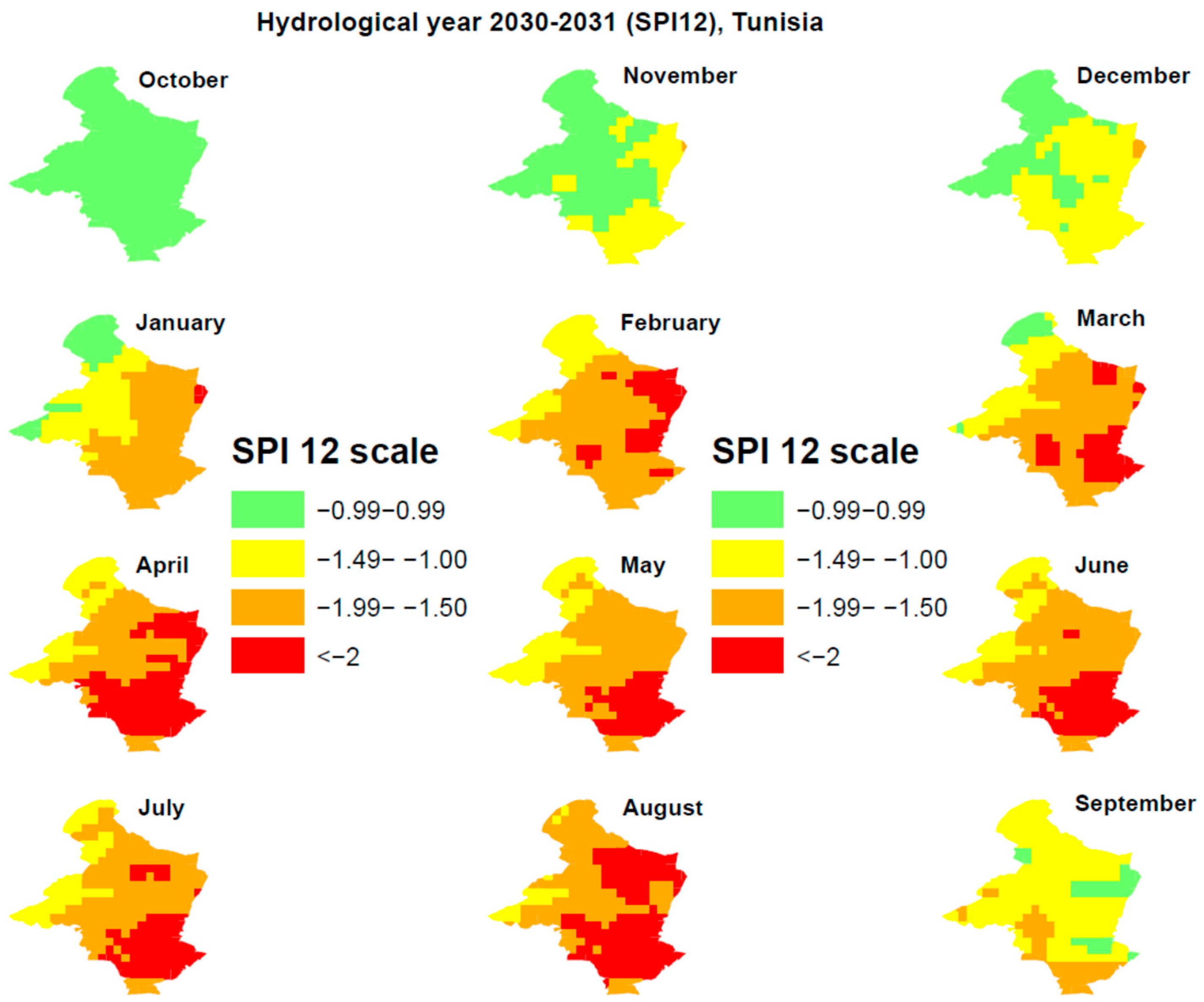

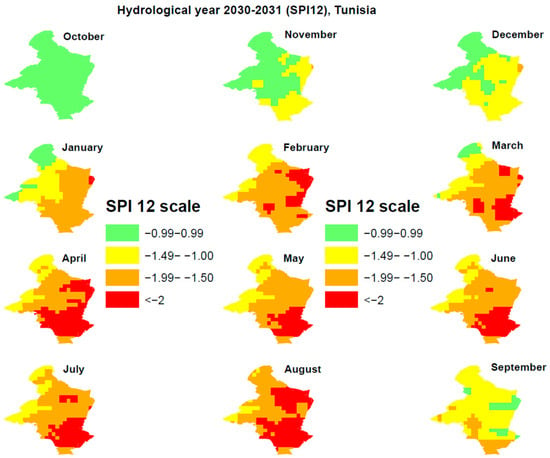

Next, an intra-annual analysis was conducted to explore the spatiotemporal evolution of drought and wetness across the two representative hydrological years. Figure 7 shows the monthly SPI12 evolution for 2030–2031. The study area can be divided into three zones: the northwestern region, the central territory, and the eastern–southern region. Drought severity escalates across these regions—from moderate drought (−1.49 < SPI < −1) in the northwestern zone, to severe drought (−1.99 < SPI < −1.5) in the central and eastern areas, and finally to extreme drought (SPI < −2) in the south. This pattern is consistently observed from January to August, with the area experiencing extreme drought expanding during the summer months. In contrast, the entire region is characterised by normal conditions in October. Moderate drought spreads across the eastern, southern, and central areas in November and December. During September, most of Sidi Bouzid is affected by moderate drought, except for some southern areas experiencing severe drought and a few eastern areas showing normal conditions.

Figure 7.

Monthly SPI12 in Sidi Bouzid Governorate (projected hydrological year: 2030–2031).

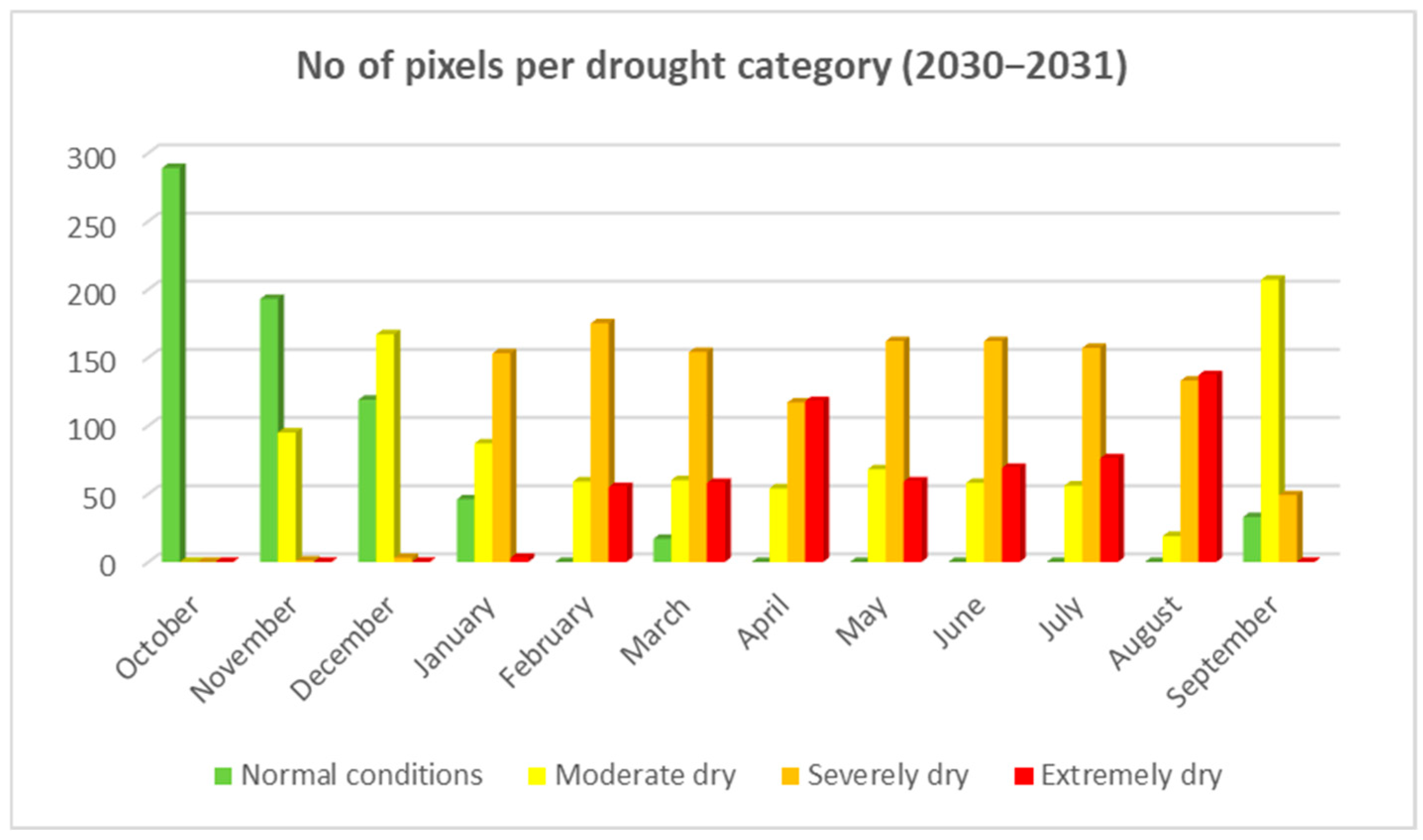

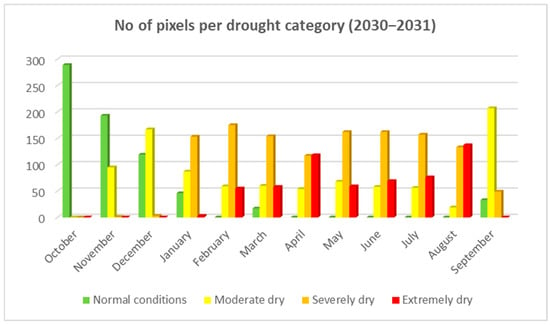

Figure 8 summarises the drought conditions in Sidi Bouzid Governorate for the projected hydrological year of 2030–2031 in terms of the percentage of pixels falling into each drought category. Many regions experience moderate drought (particularly in December and September), severe drought (from January to August), and extreme drought (especially in April and August), while normal conditions dominate during the remaining months—mainly in the first three months of the hydrological year. It is worth noting that most of the territory is affected by either severe or extreme drought from February to August.

Figure 8.

Number of pixels per drought category in Sidi Bouzid Governorate (2030–2031).

Table 5 presents the percentage of pixels falling into the different drought categories, highlighting the variability in drought intensity throughout the year. Normal conditions prevail in October and November (67–100% of the total area). Moderate drought dominates in December and September (58–72%). Severe drought is prevalent from January to August (40–61%), while extreme drought affects large portions of the study area in April and August (41–47%).

Table 5.

Percentage contribution of pixels falling into different levels of drought in Sidi Bouzid Governorate (2030–2031).

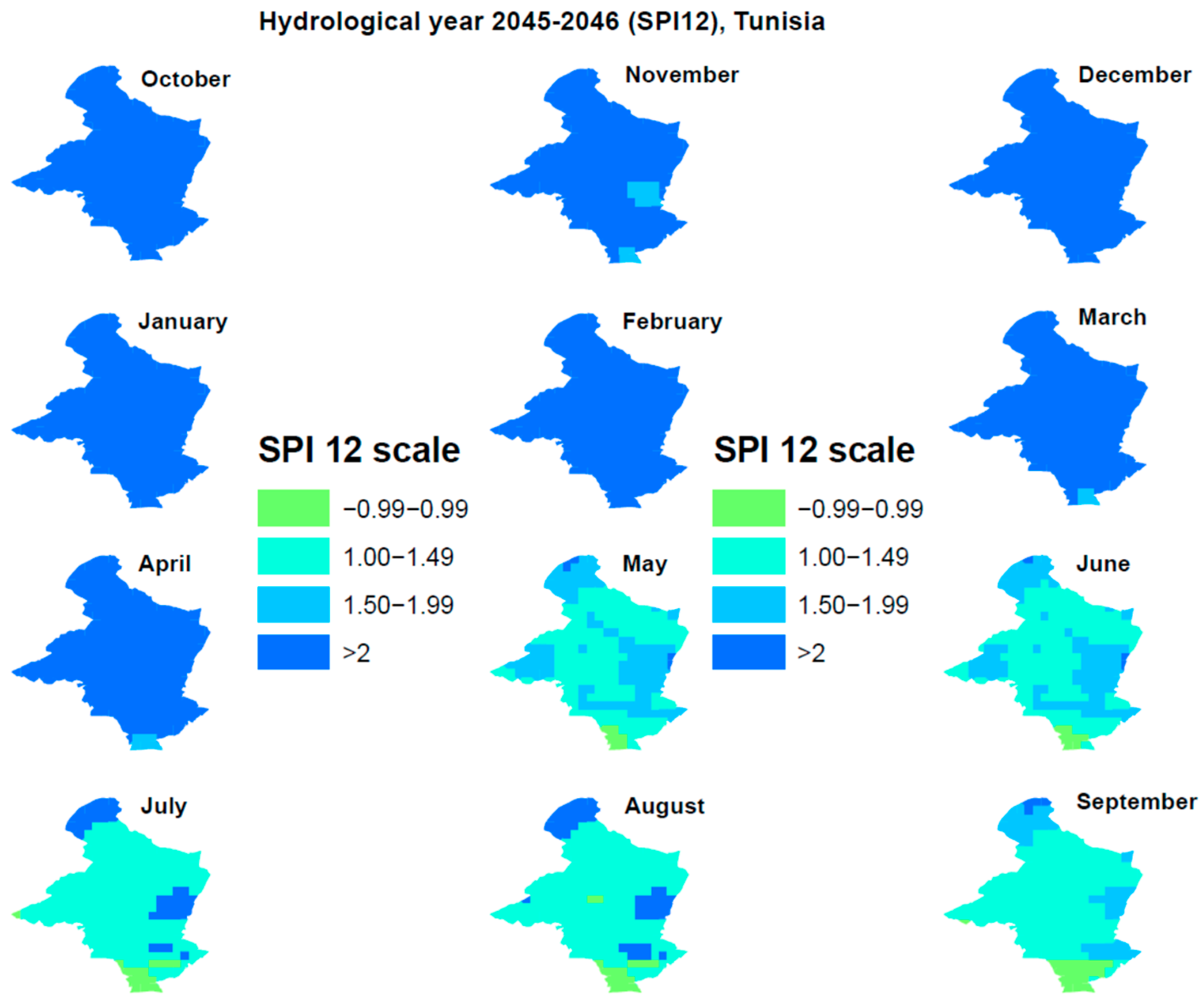

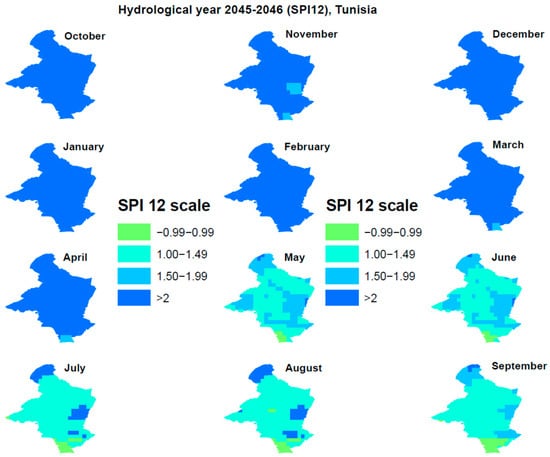

Finally, the wettest year in the projected period was evaluated. Figure 9 shows the monthly SPI12 evolution for 2045–2046. All the months of this hydrological year exhibit high levels of wetness, with no indication of drought. For nearly half of the year (October to April), the entire study domain experiences extremely wet conditions (SPI > 2). From May to September, conditions remain moderately wet (1 < SPI < 1.49), with a few scattered regions showing either wetter conditions (SPI > 2) or normal conditions (−0.99 < SPI < 0.99), particularly in the north and south, respectively.

Figure 9.

Monthly SPI12 in Sidi Bouzid Governorate (projected hydrological year: 2045–2046).

3.3. Prognostic Model for Estimating Potential Drought Conditions in Beqaa Valley, Lebanon (2020–2050)

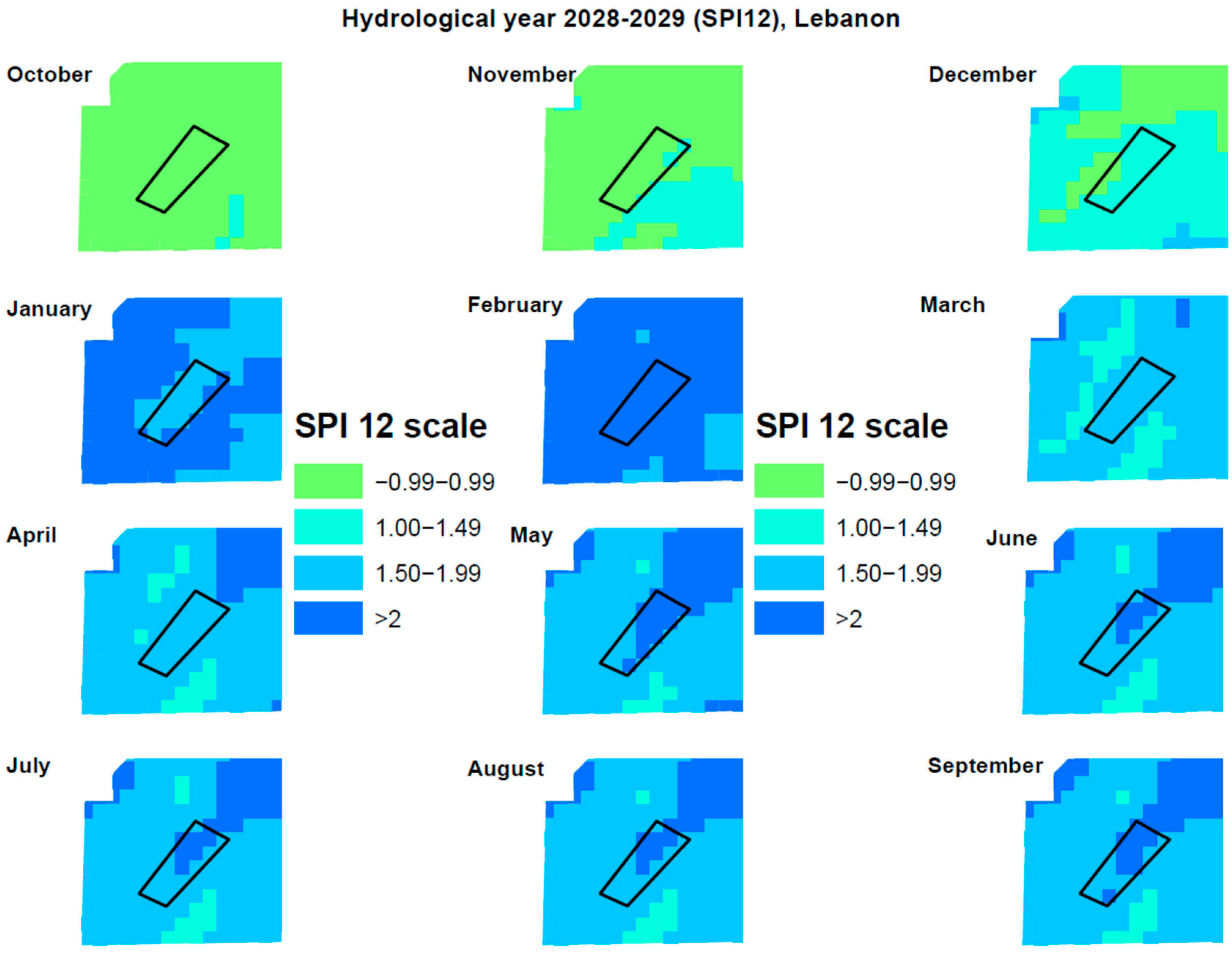

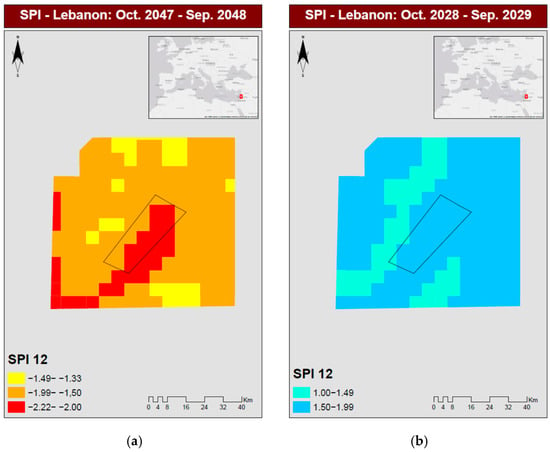

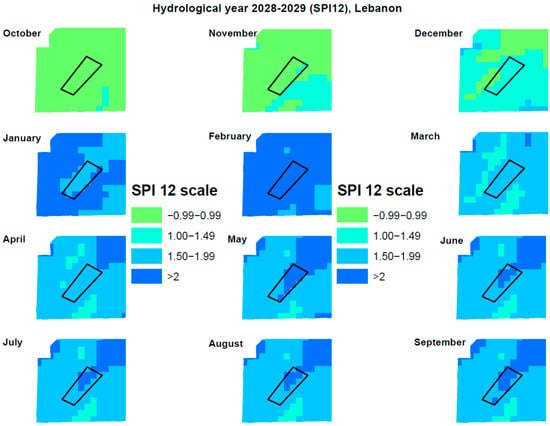

The Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model provided the projected precipitation values for each month in Lebanon from 2020 to 2050. Table 6 presents the monthly evolution of SPI12 for the projected time frame (2021–2049). As shown, the driest hydrological year is projected to be 2047–2048 (SPI = −1.82), whereas the wettest is projected to be 2028–2029 (SPI = 1.62).

Table 6.

Monthly evolution of SPI12 in Lebanon for the projected time frame (2021–2049).

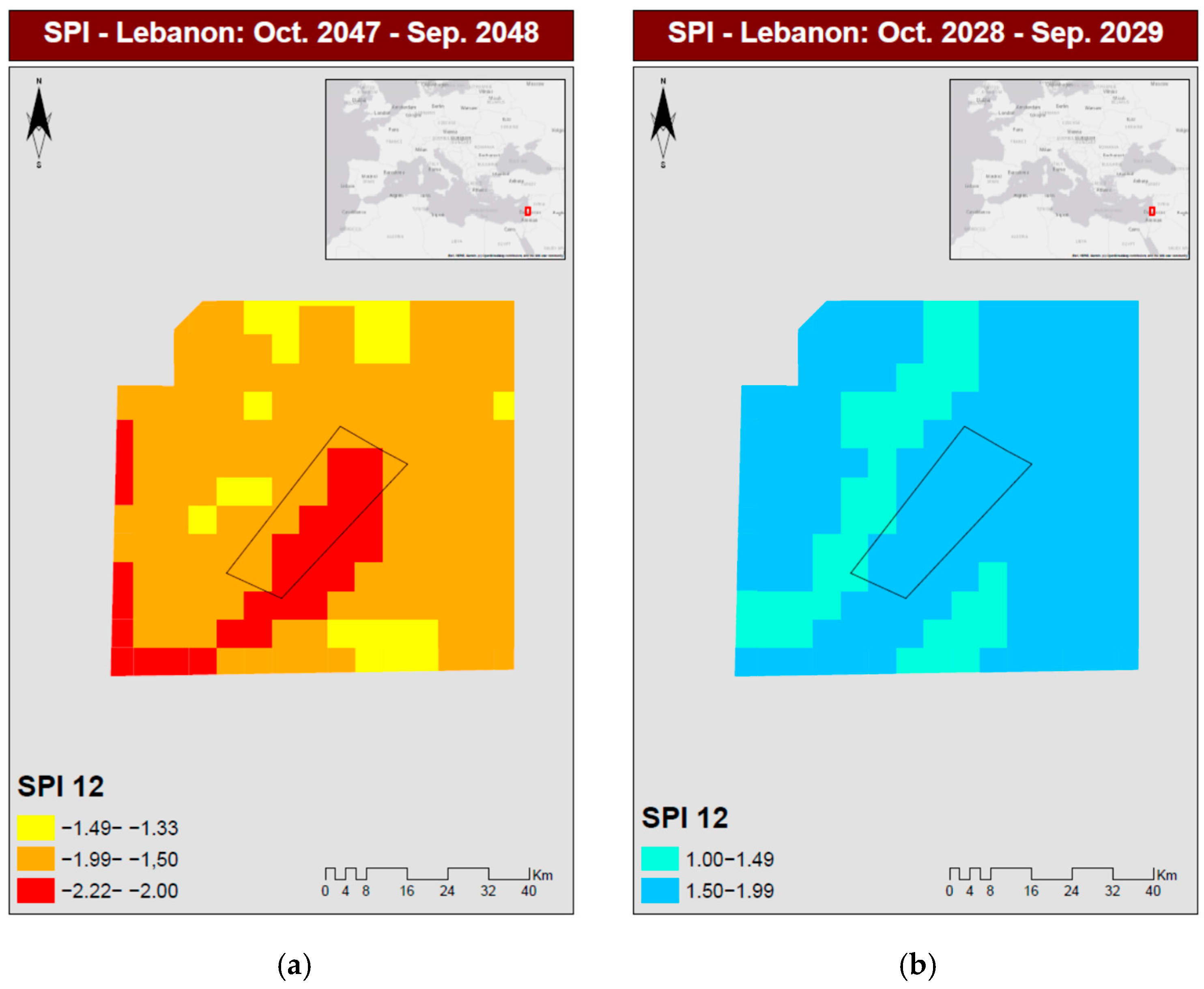

Throughout the modelled period, particular emphasis was given to the driest and wettest hydrological years. The driest year is projected to be 2047–2048. According to Figure 10a, most of the study area is characterised by severe drought (−1.99 < SPI < −1.5), while the pilot study area (outlined by the black rectangle) predominantly experiences extreme drought (SPI < −2). This result indicates that counterbalancing measures may be required to safeguard crop viability during the driest period expected over the next 30 years. Conversely, the hydrological year of 2028–2029 is forecast to be the wettest (Figure 10b). Based on the projected weather data and SPI values, the pilot study area is expected to experience very wet conditions (1.5 < SPI < 1.99), while several surrounding regions will face slightly less wet conditions (1 < SPI < 1.49).

Figure 10.

(a). SPI12 in Lebanon (October 2046–September 2047). (b). SPI12 in Lebanon (October 2028–September 2029). The black rectangle depicts the pilot study area.

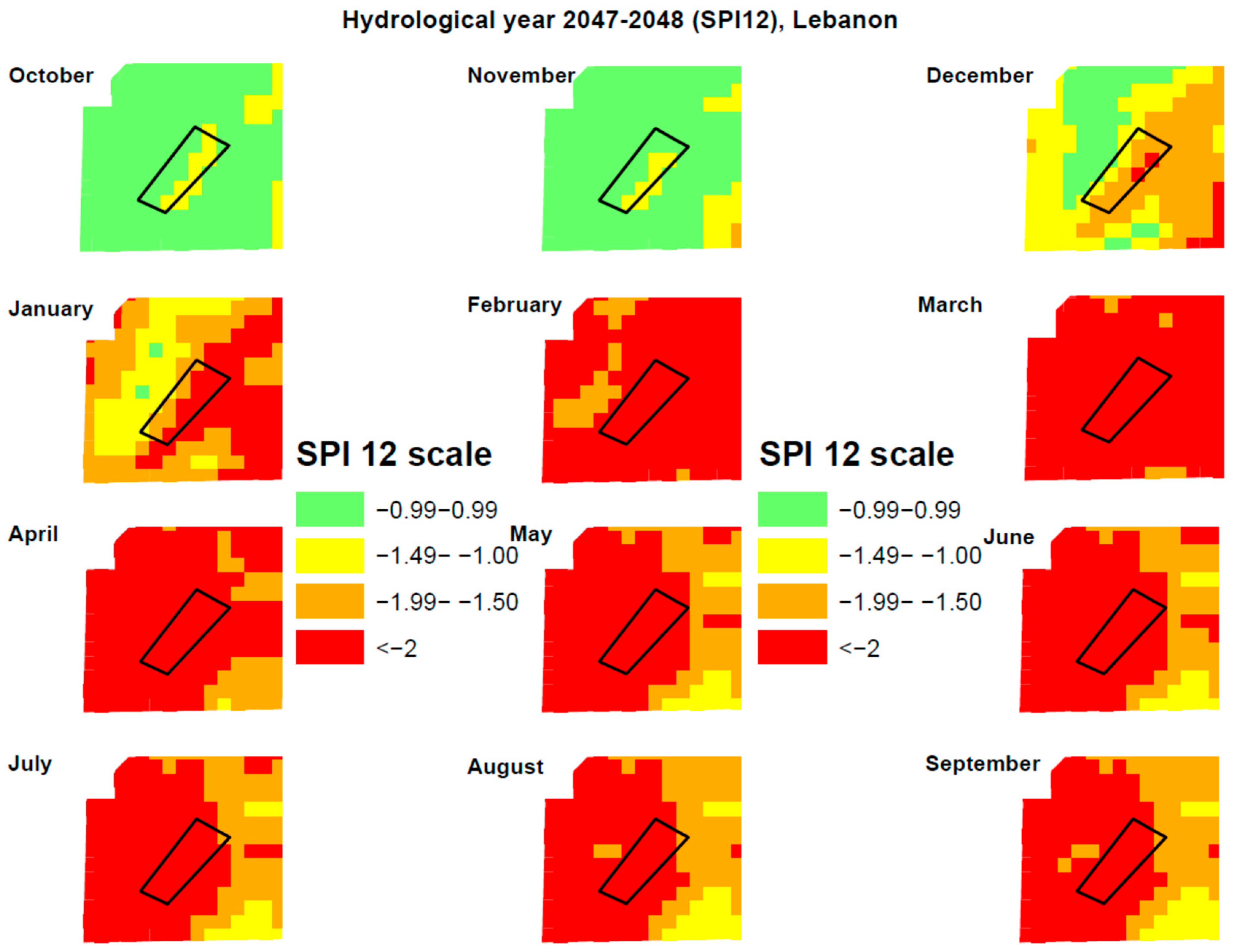

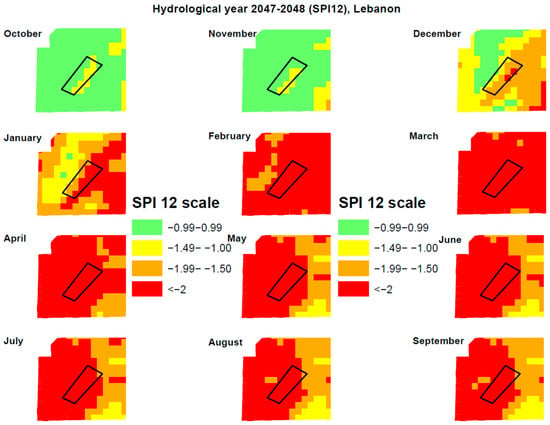

Next, an intra-annual analysis was conducted to examine the spatiotemporal evolution of drought and wetness trends throughout the two representative hydrological years. Figure 11 illustrates the monthly SPI12 evolution for 2047–2048 (driest year). At the beginning of this hydrological year (October–November), moderate drought (−1.49 < SPI < −1) predominates across most of the pilot study area, while the surrounding regions experience normal conditions. In December and January, the pilot study area presents a mixture of severe (−1.99 < SPI < −1.49) and extreme (SPI < −2) drought conditions. The wider territory exhibits normal and moderately dry conditions in the western regions and severe drought in the eastern regions in December; by January, the conditions intensify to moderate and extreme drought, respectively. For the remainder of the hydrological year (February–September), the pilot study area is projected to face extreme drought, which may significantly affect crop growth and yield. The eastern part of the broader region is characterised by severe and moderate drought from April to September, whereas the central and western areas mainly experience extreme drought.

Figure 11.

Monthly SPI12 in Lebanon (projected hydrological year: 2047–2048). The black rectangle depicts the pilot study area.

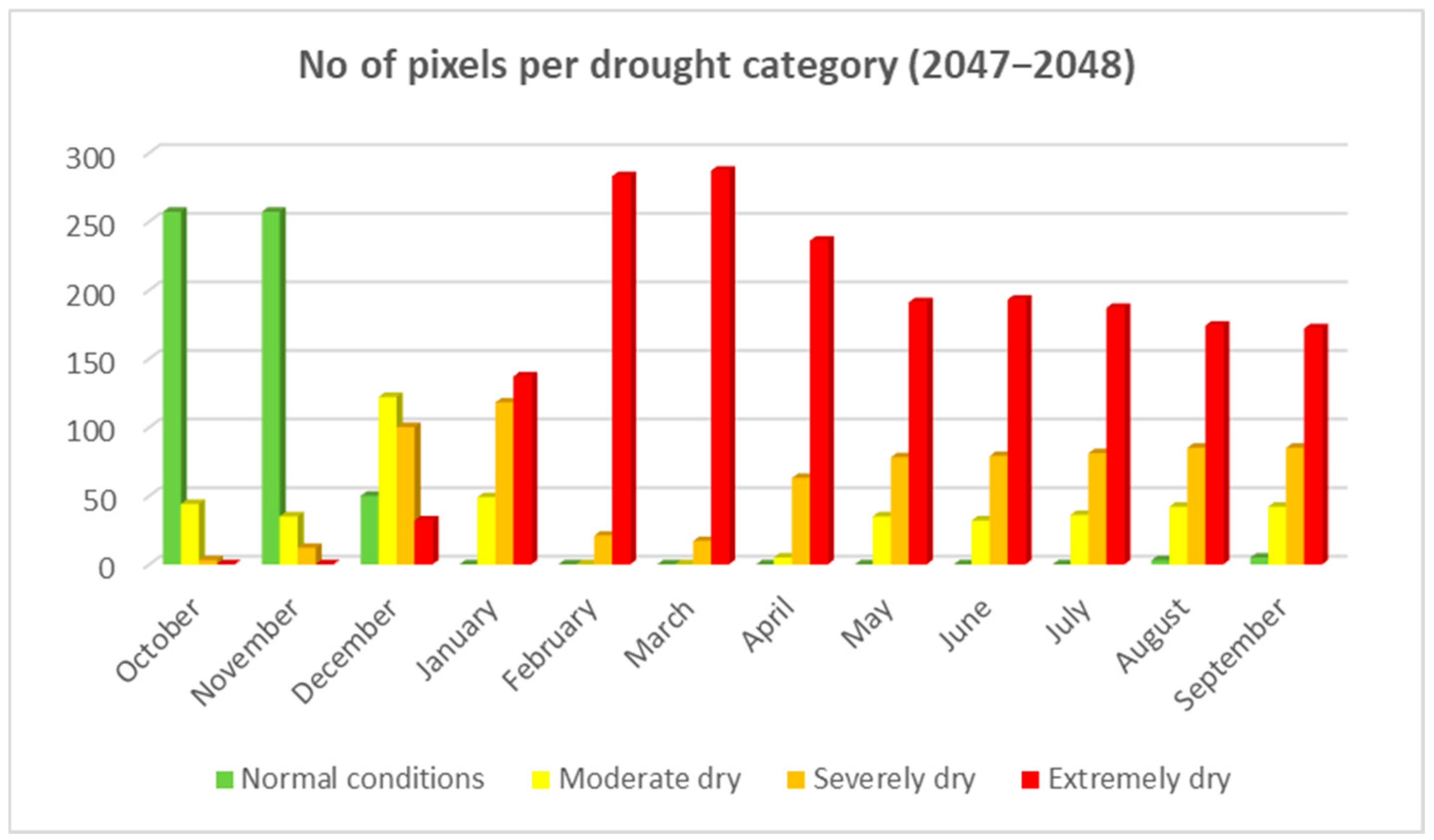

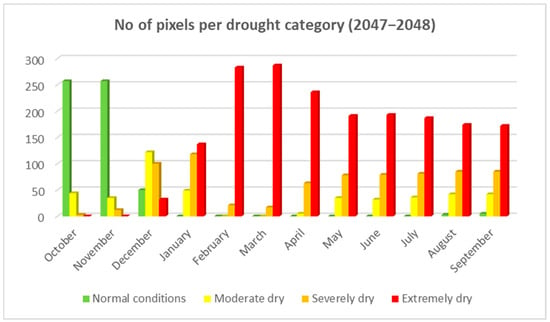

Figure 12 summarises the drought conditions in Lebanon for the projected hydrological year of 2047–2048 in terms of the proportion of pixels falling into each category. The pattern is variable: many regions experience normal or moderate dryness from October to December, while an escalating trend toward more severe drought is observed throughout the remainder of the year. Severe and, predominantly, extreme drought conditions prevail from January to September, with the pilot study area almost entirely characterised by extreme drought.

Figure 12.

Number of pixels per drought category in Lebanon (2047–2048).

Table 7 presents the percentage of pixels falling into the different drought categories. Normal conditions dominate in October and November (85% of the study area). Moderate drought is most widespread in December (40% of the total area), followed by severe drought (33%). Extreme drought becomes the dominant condition from January to September (45–94% of the study area), followed by severe drought (6–39%).

Table 7.

Percentage contribution of pixels falling into different levels of drought in Lebanon (2047–2048).

The wettest hydrological year (2028–2029) exhibits highly variable conditions. Figure 13 shows the spatial distribution of wetness across the study area. The pilot study area experiences normal conditions in October and November, while some eastern regions display moderate wetness (1 < SPI < 1.49). The pilot study area becomes moderately wet in January, March, and April. The surrounding regions are wetter in January and largely similar in March and April, except for a few areas exhibiting either wetter or slightly less wet conditions compared to the pilot study area. Finally, the pilot study area is characterised by predominantly extreme wetness in February and from May to September. The wider region displays varying degrees of wetness, from moderate to extreme. Specifically, the northeastern regions tend to exhibit extreme wetness, the southern regions experience moderate wetness, and the remaining territory (apart from the pilot study area) is characterised by wet conditions.

Figure 13.

Monthly SPI12 in Lebanon (projected hydrological year: 2028–2029). The black rectangle depicts the pilot study area.

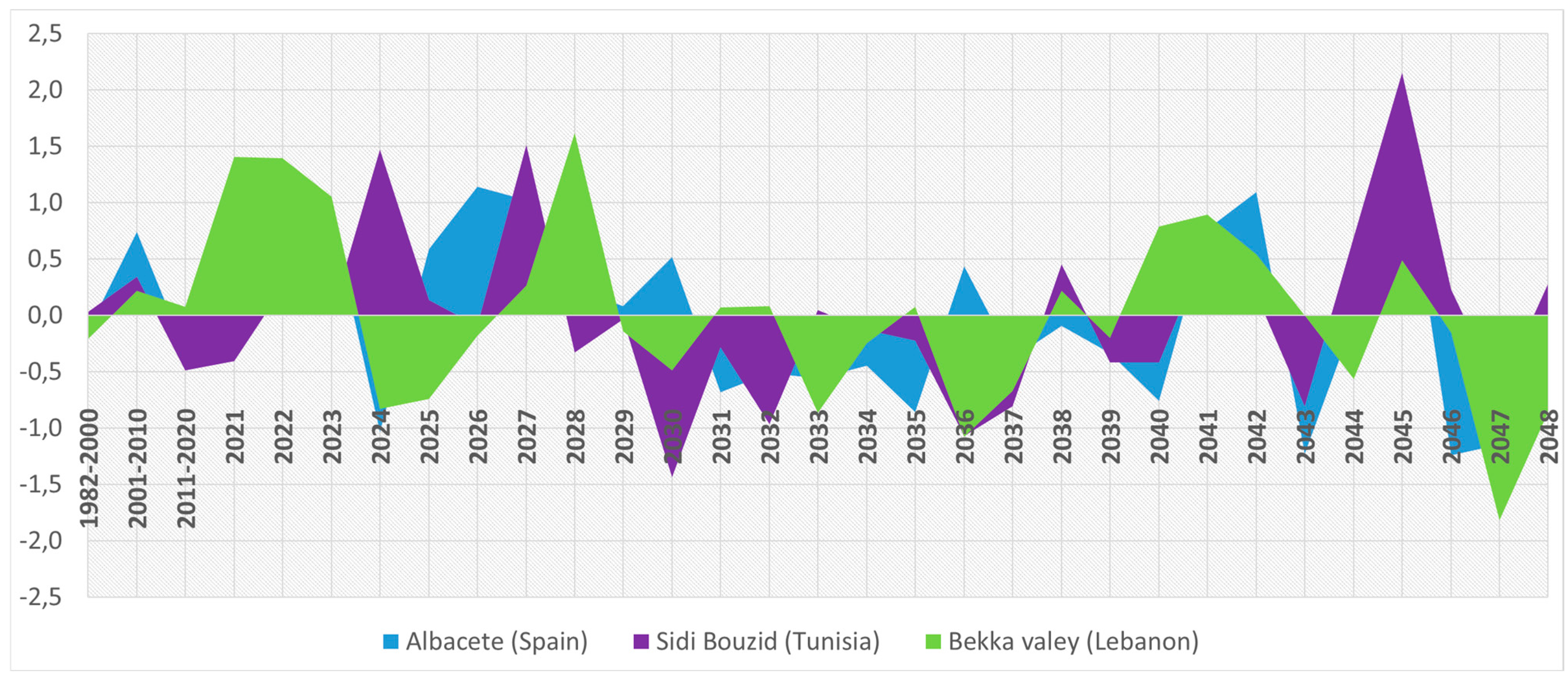

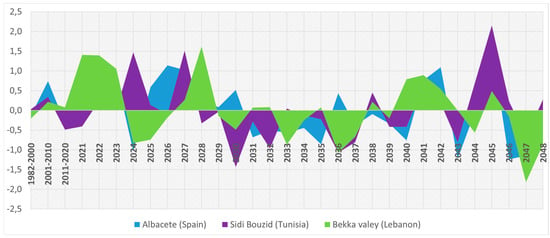

3.4. Comparative Analysis of Future Drought and Wetness Evolution for the Three Mediterranean Study Areas

Finally, Figure 14 presents the comparative assessment of the future SPI12 evolution and the corresponding dry and wet hydrological years for the entire projected period across the three Mediterranean study areas. The first three values in the figure represent the median SPI12 values for the last three historical periods—1982–2000, 2001–2010 and 2011–2020—providing an overview of past drought and wetness trends. Median values were selected to minimise the influence of potential outliers on the overall assessment.

Figure 14.

Drought severity assessment (hydrological years) through SPI12 evolution (1982–2048) in Albacete (Spain), Sidi Bouzid (Tunisia) and Bekaa valley (Lebanon).

For Albacete, the variability is relatively low, with SPI12 values ranging from −1.24 to 1.62. This suggests only a few years with moderately dry conditions (e.g., 2043: −1.22 and 2046: −1.24) or moderately wet conditions (e.g., 2028 and 2042). In Sidi Bouzid Governorate, aside from the extreme drought and wet years previously examined, no additional critical dry hydrological years are anticipated. Variability is higher here, with SPI12 values ranging from −1.43 to 2.15. Potential dry years generally exhibit values close to or slightly below −1, except for 2030, which is expected to show moderate dryness (−1.43). In contrast, three particularly wet years are anticipated—2024, 2027 and 2045—with SPI12 values of 1.47, 1.51 and 2.16, respectively, indicating moderately to very wet conditions. In the Bekaa Valley, and beyond the extreme dry and wet years already highlighted, no other critical dry hydrological years are projected. Variability is similar to that observed in Sidi Bouzid, with SPI12 values ranging from −1.81 to 1.61. Most potential dry years range close to or slightly below −1, except for 2047, which is anticipated to be a very dry year with SPI12 values approaching −1.82. Conversely, 2021, 2022 and 2028 are projected to be wet years, with SPI12 values of 1.41, 1.39 and 1.62, respectively, indicating moderately to very wet conditions.

The modelled drought and wetness trends exhibit broadly similar behaviour across the three Mediterranean regions. During the first projected decade (2020–2030), all areas are expected to experience predominantly normal to slightly wet conditions. In the following decade (2030–2040), conditions are predicted to be mostly normal to slightly dry. In the final decade (2040–2048), Albacete and the Bekaa Valley are expected to maintain similar patterns, while Sidi Bouzid shows more variability. Overall, conditions across all regions are expected to remain within the normal range, except for a few years presenting moderate dry or wet conditions.

4. Discussion and Planning Recommendations

This study employed a two-stage procedure for assessing future drought conditions. First, precipitation projections for the period 2020–2050 were generated using the WRF model. These served as input for estimating SPI12 values for three Mediterranean countries with similar yet distinct climatic characteristics—Spain, Tunisia and Lebanon. This process is essential, as it provides decision makers with the necessary information to design appropriate measures against drought, particularly in regions where the highest risk is anticipated.

The findings align with similar studies in which the Reconnaissance Drought Index, Precipitation Decile Index and the Standardized Precipitation Index were applied to assess future drought conditions under different climatic scenarios, namely RCP2.6, RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 [41]. Likewise, the authors of [42] estimated the future spatiotemporal patterns of drought intensity for Greece using the SPEI6,12 and SPI6,12 based on WRF projections under RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 up to 2100. In the same context, the authors of [43] conducted a probabilistic drought assessment using Global Circulation Model simulations to drive historical and future SPI and SPEI analyses, showing that droughts are expected to intensify during summer months. While previous studies have provided valuable insights into future drought evolution using indices such as the SPI and SPEI under different climate scenarios, their primary focus has generally been on regional or national-scale assessments and on annual or seasonal drought indicators. In many cases, drought projections are analysed as standalone climatic outputs, without an explicit linkage to spatial planning, land-use decision making, or resilience-oriented applications. The research gap addressed in this study lies in the absence of high-resolution, planning-oriented drought projection frameworks that explicitly support spatially targeted adaptation strategies. In this context, the combined application of dynamically downscaled WRF precipitation projections and SPI analysis enables the estimation of future drought and wetness conditions at a 5 km spatial resolution and across both annual and monthly temporal scales, supported by a series of thematic maps. This multi-scale representation of temporal and spatial drought and wetness intensity allows for the identification of sub-regional variability that is often masked in coarser or purely temporal analyses. As a result, the proposed framework moves beyond descriptive drought assessment and provides an operational basis for informed, place-based resilience planning in Mediterranean agroecosystems.

Our findings are fully consistent with those in [44], which emphasised the need for further drought assessment studies based on representative locations across the Mediterranean basin in order to better address uncertainties in regional climate behaviour. These uncertainties are particularly pronounced for hydrological droughts, where human pressures—such as increasing water demand driven by urbanisation and declining water availability—play a critical role, especially in the southern and eastern Mediterranean regions [44]. By adopting a comparative, multi-regional approach, the present study directly responds to this need, providing spatially explicit drought projections that support more robust and regionally tailored planning and water-management strategies.

Our monthly analysis similarly revealed differentiated drought conditions across the three countries in the driest projected year: Albacete is expected to experience extreme and severe drought from late spring to early autumn (April–September); Sidi Bouzid Governorate is projected to be affected by shorter but less spatially extensive drought from February to August; and the Bekaa Valley is anticipated to face more widespread and persistent drought from February to September.

Although the SPI is one of the most widely applied indices for drought assessment, its limitations are acknowledged [45]. Specifically, its performance depends entirely on precipitation and does not incorporate additional atmospheric variables. Under climate change and rising temperatures, evapotranspiration becomes increasingly important in assessing future drought [46,47,48]. Even though the SPEI is often considered a more reliable index [1], the SPI remains robust when compared with weather station measurements [45], and its use is particularly relevant in regions lacking sufficient temperature data and where the SPI may be the only feasible option [49]. In the context of this study, the SPI was prioritised to isolate precipitation-driven drought signals that are directly relevant to water availability and planning decisions while ensuring methodological consistency across regions and future climate projections. This choice facilitates comparability between study areas and supports the spatial planning focus of the analysis, without precluding the integration of temperature-based indices in future work.

We extended the drought assessment analysis to three Mediterranean countries. Although some tendencies appear similar, the occurrence of extreme drought and wet years varies considerably across the study areas. The driest projected year is 2046 for Spain and 2047 for Lebanon, whereas Tunisia is expected to experience its driest year much earlier, in 2030. Conversely, the wettest year is projected to occur in 2045 for Spain and Tunisia, while 2028 is projected to be the wettest in Lebanon. This variability reflects the heterogeneous nature of regional atmospheric processes, even among countries sharing broadly similar climatic environments.

Beyond identifying the driest hydrological year—an essential step for strengthening drought resilience—we also identified the wettest year, both statistically and geographically. This information may support more rational water resource management. Anticipating a wet year may enable managers to temporarily ease drought-mitigation efforts while promoting water storage that enhances crop productivity. In this regard, spatial planning should play a central role alongside climate planning. It is recommended that land-use optimisation prioritise agricultural zones, particularly in areas expected to have favourable climatic conditions. Likewise, land-use restrictions may be necessary to prevent the encroachment of higher-value but incompatible uses (e.g., industrial activities) [50]. Such measures help safeguard valuable agricultural land and prevent soil contamination unless socioeconomic conditions justify mixed land-use development through vertically integrated production systems.

In parallel, planners and policymakers should adopt a multi-hazard perspective by jointly assessing drought and flood risks. Analysing both the driest and wettest projected hydrological years provides insight into the full spectrum of extremes that a region may face. As highlighted in recent multi-hazard planning research, droughts and floods may share underlying climatic drivers, occur sequentially and generate cascading or compound impacts. Addressing them together supports more coherent and efficient land-use planning, improves integrated water-management strategies and strengthens overall territorial resilience [51,52].

Considering the inherent uncertainty associated with climate projections, although future precipitation projections cannot be directly validated against observations, the robustness of the SPI methodology has been extensively evaluated in previous studies. In particular, the SPI-based drought assessment framework applied herein has been validated against observed meteorological records in similar Mediterranean environments [45], demonstrating its reliability in capturing drought severity and temporal variability. In the present study, the SPI is applied consistently across regions using dynamically downscaled WRF precipitation to support comparative, planning-oriented assessments. No bias correction was applied to the dynamically downscaled precipitation outputs, which constitutes a recognised limitation for SPI-based analyses and is therefore acknowledged when interpreting the results. Nevertheless, uncertainty in climate projections remains an inherent constraint of future-oriented drought assessments [53].

5. Conclusions

Drought hazard is expected to increase in both frequency and intensity, emphasising the importance of forward-looking assessments to support preparedness and resilience, particularly in vulnerable regions. In this study, future precipitation for the period 2020–2050 was projected using the WRF model for three representative Mediterranean regions in Spain, Tunisia, and Lebanon, enabling the calculation of the SPI12 and the assessment of future drought and wetness conditions. The results provide annual and monthly insights into emerging dry and wet patterns, supported by spatially explicit mapping. Although extreme drought or wetness conditions are not projected uniformly across all regions, considerable local-scale variability was identified, underscoring the limitations of uniform adaptation measures and highlighting the need for targeted, place-based planning strategies.

Beyond identifying the driest hydrological years, the analysis also highlights the future wettest years, offering opportunities for more rational water-resource management, including the temporary adjustment of drought mitigation measures, enhanced water storage, and improved agricultural productivity. In this context, spatial planning plays a critical role in safeguarding agricultural land, particularly in areas with favourable projected climatic conditions, while land-use restrictions may be necessary to prevent incompatible developments. Finally, adopting a multi-hazard perspective—through the joint assessment of drought and flood risks—supports more coherent and efficient territorial planning as these hazards may share climatic drivers, occur sequentially, and generate cascading impacts. Such integrated approaches are essential for strengthening long-term resilience and supporting sustainable development in climate-exposed regions.

6. Disclosure

AI-based tools (e.g., ChatGPT 5.2 by OpenAI) were used to assist with language refinement and editing. All scientific content, interpretations, and conclusions were solely developed and approved by the authors.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/hydrology13020073/s1, Table S1: Summary of datasets used in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S., N.A., N.D. (Nicholas Dercas); methodology, S.S., N.A. and N.D. (Nicholas Dercas); software, S.S., N.A., S.K. and G.A.T.; validation, M.S., N.A., S.S., I.F. and P.S.; formal analysis, I.F., P.S.; investigation, A.D., J.A.M.-L., F.K., R.L.-U., F.K., H.A., A.T., K.G. and R.N.; resources, A.D., J.A.M.-L., F.K., R.L.-U., F.K., H.A. and R.N.; data curation, N.A., I.F. and G.A.T.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S. and S.S.; writing—review and editing, S.S., N.D. (Nicholas Dercas) and M.S.; visualization, N.D. (Nicholas Dercas) and N.D. (Nicholas Dercas); supervision, N.D. (Nicholas Dercas), N.D. (Nicholas Dercas), A.D., S.S., J.A.M.-L. and F.K.; project administration, S.S. and N.D. (Nicholas Dercas); funding acquisition, N.D. (Nicholas Dercas) and N.D. (Nicholas Dercas) All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the SUPROMED project, Call 2018, under the PRIMA program of the European Commission (Grant Agreement No 1813).

Data Availability Statement

A summary of all datasets used in this study, including their temporal and spatial resolutions and their role in the workflow, is provided in Table S1 (Supplementary Materials). The data presented in this study is available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ault, T.R. On the essentials of drought in a changing climate. Science 2020, 368, 256–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, T.M.; Robertson, G.C. Disturbance and Sustainability in Forests of the Western United States; General Technical Report PNW-GTR-992; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station: Portland, OR, USA, 2021; p. 231.

- Van Loon, A.F.; Stahl, K.; Di Baldassarre, G.; Clark, J.; Rangecroft, S.; Wanders, N.; Gleeson, T.; Van Dijk, A.I.J.M.; Tallaksen, L.M.; Hannaford, J.; et al. Drought in a human-modified world: Reframing drought definitions, understanding, and analysis approaches. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2016, 20, 3631–3650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwayama, Y.; Thompson, A.; Bernknopf, R.; Zaitchik, B.; Vail, P. Estimating the Impact of Drought on Agriculture Using the U.S. Drought Monitor. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2019, 101, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, R.; Nath, D.; Li, Q.; Chen, W.; Cui, X. Impact of drought on agriculture in the Indo-Gangetic Plain, India. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2017, 34, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullin, M. The effects of drinking water service fragmentation on drought-related water security. Science 2020, 368, 274–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosley, L.M. Drought impacts on the water quality of freshwater systems; review and integration. Earth. Sci. Rev. 2015, 140, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, J.M.; Lopes, F.A.C.; Lopes-Ferreira, M.; Vidal, L.M.; Leomil, L.; Melo, F.; de Azevedo, G.S.; Oliveira, R.M.S.; Medeiros, A.J.; Melo, A.S.O.; et al. Occurrence of harmful cyanobacteria in drinking water from a severely drought-impacted semi-arid region. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 318788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuartas, L.A.; Cunha, A.P.M.D.A.; Alves, J.A.; Parra, L.M.P.; Deusdará-Leal, K.; Costa, L.C.O.; Molina, R.D.; Amore, D.; Broedel, E.; Seluchi, M.E.; et al. Recent Hydrological Droughts in Brazil and Their Impact on Hydropower Generation. Water 2022, 14, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.; Zhao, J.; Popat, E.; Herbert, C.; Döll, P. Analyzing the Impact of Streamflow Drought on Hydroelectricity Production: A Global-Scale Study. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57, e2020WR028087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakellariou, S.; Sfougaris, A.; Christopoulou, O.; Tampekis, S. Integrated wildfire risk assessment of natural and anthropogenic ecosystems based on simulation modeling and remotely sensed data fusion. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 78, 103129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakellariou, S.; Sfoungaris, G.; Christopoulou, O. Territorial Resilience Through Visibility Analysis for Immediate Detection of Wildfires Integrating Fire Susceptibility, Geographical Features, and Optimization Methods. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2022, 13, 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Lee, W.S.; Kim, S.T.; Chun, J.A. Historical Drought Assessment Over the Contiguous United States Using the Generalized Complementary Principle of Evapotranspiration. Water Resour. Res. 2019, 55, 6244–6267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muse, N.M.; Tayfur, G.; Safari, M.J.S. Meteorological Drought Assessment and Trend Analysis in Puntland Region of Somalia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayissa, Y.; Maskey, S.; Tadesse, T.; Van Andel, S.J.; Moges, S.A.; Van Griensven, A.; Solomatine, D. Comparison of the Performance of Six Drought Indices in Characterizing Historical Drought for the Upper Blue Nile Basin, Ethiopia. Geosciences 2018, 8, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Zeng, R.; Kang, W.H.; Song, J.; Valocchi, A.J. Strategic Planning for Drought Mitigation under Climate Change. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2015, 141, 04015004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Peña-Angulo, D.; Beguería, S.; Domínguez-Castro, F.; Tomás-Burguera, M.; Noguera, I.; Gimeno-Sotelo, L.; El Kenawy, A. Global drought trends and future projections. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2022, 380, 20210285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Sun, F. Integrated drought vulnerability and risk assessment for future scenarios: An indicator based analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 900, 165591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essa, Y.H.; Hirschi, M.; Thiery, W.; El-Kenawy, A.M.; Yang, C. Drought characteristics in Mediterranean under future climate change. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2023, 6, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos-Garcia, P.; Lopez-Nicolas, A.; Pulido-Velazquez, M. Combined use of relative drought indices to analyze climate change impact on meteorological and hydrological droughts in a Mediterranean basin. J. Hydrol. 2017, 554, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Gomez, J.d.D.; Pulido-Velazquez, D.; Collados-Lara, A.J.; Fernandez-Chacon, F. The impact of climate change scenarios on droughts and their propagation in an arid Mediterranean basin. A useful approach for planning adaptation strategies. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 820, 153128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaniolo, M.; Fletcher, S.; Mauter, M.S. Multi-scale planning model for robust urban drought response. Environ. Res. Lett. 2023, 18, 054014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ámbito e Integración—Junta Central Regantes Mancha Oriental. Available online: https://www.jcrmo.org/entidad/ambito-e-integracion/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Martínez-López, J.A.; López-Urrea, R.; Martínez-Romero, Á.; Pardo, J.J.; Montero, J.; Domínguez, A. Sustainable Production of Barley in a Water-Scarce Mediterranean Agroecosystem. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidi Bouzid Governorate—Wikipedia. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sidi_Bouzid_Governorate (accessed on 11 February 2026).

- Sidi Bouzid Climate, Weather by Month, Average Temperature (Tunisia)—Weather Spark. Available online: https://weatherspark.com/y/61917/Average-Weather-in-Sidi-Bouzid-Tunisia-Year-Round (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Sakellariou, S.; Dalezios, N.R.; Spiliotopoulos, M.; Alpanakis, N.; Faraslis, I.; Tziatzios, G.A.; Sidiropoulos, P.; Dercas, N.; Domínguez, A.; López, H.M.; et al. Remotely Sensed Comparative Spatiotemporal Analysis of Drought and Wet Periods in Distinct Mediterranean Agroecosystems. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobrossi, J.; Karam, F.; Mitri, G. Rain pattern analysis using the Standardized Precipitation Index for long-term drought characterization in Lebanon. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, J.G.; Klemp, J.B.; Skamarock, W.C.; Davis, C.A.; Dudhia, J.; Gill, D.O.; Coen, J.L.; Gochis, D.J.; Ahmadov, R.; Peckham, S.E.; et al. The Weather Research and Forecasting Model: Overview, System Efforts, and Future Directions. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2017, 98, 1717–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weather Research & Forecasting Model (WRF) | Mesoscale & Microscale Meteorology. Available online: https://www.mmm.ucar.edu/models/wrf (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Skamarock, A.W.; Klemp, J.B.; Dudhia, J.; Gill, D.O.; Zhiquan, L.; Berner, J.; Wang, W.; Powers, J.G.; Duda, M.G.; Barker, D.M.; et al. A Description of the Advanced Research WRF Model Version 4.1; National Center for Atmospheric Research: Boulder, CO, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruyère, C.L.; Monaghan, A.J.; Steinhoff, D.F.; Yates, D. Bias-Corrected CMIP5 CESM Data in WRF/MPAS Intermediate File Format. Available online: http://library.ucar.edu/research/publish-technote (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Monforte, P.; Imposa, S. Future Dynamics of Drought in Areas at Risk: An Interpretation of RCP Projections on a Regional Scale. Hydrology 2025, 12, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barredo, J.I.; Mauri, A.; Caudullo, G.; Dosio, A. Assessing Shifts of Mediterranean and Arid Climates Under RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 Climate Projections in Europe. In Meteorology and Climatology of the Mediterranean and Black Seas; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazi, B.; Salehi, H.; Przybylak, R.; Pospieszyńska, A. Assessment of drought conditions under climate change scenarios in Central Europe (Poland) using the standardized precipitation index (SPI). Clim. Serv. 2025, 39, 100591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhawana, M.B.; Kanyerere, T.; Kahler, D.; Masilela, N.S.; Lalumbe, L.; Umunezero, A.A. Hydrological drought assessment using the standardized groundwater index and the standardized precipitation index in the Berg River Catchment, South Africa. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 53, 101779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, T.B.; Doesken, N.J.; Kleist, J. The relationship of drought frequency and duration to time scales. In Proceedings of the 8th Conference on Applied Climatology, Anaheim, CA, USA, 17–23 January 1993; pp. 179–184. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Hughes, B.; Saunders, M.A. A drought climatology for Europe. Int. J. Climatol 2002, 22, 1571–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copernicus European Drought Observatory (EDO). Available online: https://edo.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Aurenhammer, F.; Klein, R.; Lee, D.T. Voronoi Diagrams and Delaunay Triangulations; World Scientific Pub Co Pte Ltd.: Singapore, 2012; pp. 1–337. [Google Scholar]

- Khanmohammadi, N.; Rezaie, H.; Behmanesh, J. Investigation of Drought Trend on the Basis of the Best Obtained Drought Index. Water Resour. Manag. 2022, 36, 1355–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politi, N.; Vlachogiannis, D.; Sfetsos, A.; Nastos, P.T.; Dalezios, N.R. High Resolution Future Projections of Drought Characteristics in Greece Based on SPI and SPEI Indices. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Srivastava, P.; Lamba, J. Probabilistic assessment of projected climatological drought characteristics over the Southeast USA. Clim. Change 2018, 147, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramblay, Y.; Koutroulis, A.; Samaniego, L.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Volaire, F.; Boone, A.; Le Page, M.; Llasat, M.C.; Albergel, C.; Burak, S. Challenges for drought assessment in the Mediterranean region under future climate scenarios. Earth. Sci. Rev. 2020, 210, 103348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakellariou, S.; Spiliotopoulos, M.; Alpanakis, N.; Faraslis, I.; Sidiropoulos, P.; Tziatzios, G.A.; Karoutsos, G.; Dalezios, N.R.; Dercas, N. Spatiotemporal Drought Assessment Based on Gridded Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) in Vulnerable Agroecosystems. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi Zarch, M.A.; Sivakumar, B.; Sharma, A. Droughts in a warming climate: A global assessment of Standardized precipitation index (SPI) and Reconnaissance drought index (RDI). J. Hydrol. 2015, 526, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, D. Assessment of Meteorological Drought Indices in Korea Using RCP 8.5 Scenario. Water 2018, 10, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Park, G.; Jung, H.; Jang, D. Assessment of Future Drought Index Using SSP Scenario in Rep. of Korea. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhail, S.; Katipoğlu, O.M. Comparison of the SPI and SPEI as drought assessment tools in a semi-arid region: Case of the Wadi Mekerra basin (northwest of Algeria). Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2023, 154, 1373–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Zou, X.; Cui, Y.; Ying, S.; Zhou, Y. Spatial planning based on the modeling the food-energy-water-carbon nexus: A case study of the Yangtze River basin. Agric. Syst. 2026, 231, 104552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzorni, M.; Innocenti, A.; Tollin, N. Droughts and floods in a changing climate and implications for multi-hazard urban planning: A review. City Environ. Interact. 2024, 24, 100169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinh, N.Q.; Van, T.T. Resilient Spatial Planning for Drought-Flood Coexistence (‘DFC’): Outlook Towards Smart Cities. In Smart and Sustainable Cities and Buildings; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Marotzke, J. Quantifying the irreducible uncertainty in near-term climate projections. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2019, 10, e563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.