Abstract

A hybrid machine learning framework has been developed in this study to estimate Terrestrial Water Storage Anomalies (TWSA) in Morocco’s Casablanca–Settat region, which faces serious groundwater stress due to rapid urbanization, intensive agriculture, and climate variability. In this study, TWSA is used as an integrated proxy for groundwater-related storage changes, while acknowledging that it also includes contributions from soil moisture and surface water. The approach combines satellite-based observations from the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) and GRACE Follow-On (GRACE-FO) with key environmental indicators such as rainfall, evapotranspiration, and land use data to track changes in groundwater availability with improved spatial detail. After preprocessing the data through feature selection, normalization, and outlier handling, the model applies six base learners, i.e., Huber regressor, automatic relevance determination regression, kernel ridge, long short-term memory, k-nearest neighbors, and gradient boosting. Their predictions are aggregated using a random forest meta-learner to improve accuracy and stability. The ensemble achieved strong results, with a root mean square error of 0.13, a mean absolute error of 0.108, and a determination coefficient of 0.97—far better than single-model baselines—based on a temporally independent train-test split. Spatial analysis highlighted clear patterns of groundwater depletion linked to land cover and usage. These results can guide targeted aquifer recharge efforts, drought response planning, and smarter irrigation management. The model also aligns with national goals under Morocco’s water sustainability initiatives and can be adapted for use in other regions with similar environmental challenges.

1. Introduction

Groundwater constitutes approximately 30% of the global freshwater supply and plays a critical role in supporting agriculture, maintaining ecological balance, and meeting human consumption needs, particularly in arid and semi-arid zones [1]. However, escalating pressures from climate change, population growth, and Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) transformations are threatening groundwater sustainability. Effective management strategies require robust systems capable of capturing spatiotemporal fluctuations in groundwater levels [2,3].

Satellite-based missions such as Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) and GRACE Follow-On (GRACE-FO) have significantly advanced large-scale monitoring of Terrestrial Water Storage Anomalies (TWSA), offering insights into the combined behavior of groundwater, soil moisture, and surface water. Despite their global utility, the coarse spatial resolution of these datasets limits their applicability in localized groundwater planning. To bridge this gap, machine learning (ML) techniques are increasingly utilized to extract meaningful correlations between hydro-climatic variables and groundwater dynamics. While single-model approaches often lack the flexibility to generalize across heterogeneous geographies, hybrid ML frameworks integrate multiple algorithms and deep learning architectures. Architectures such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) have shown promising results in capturing both short-term variability and long-term trends, thereby enhancing the accuracy and operational relevance of groundwater predictions.

1.1. Relevance to the Casablanca–Settat Region

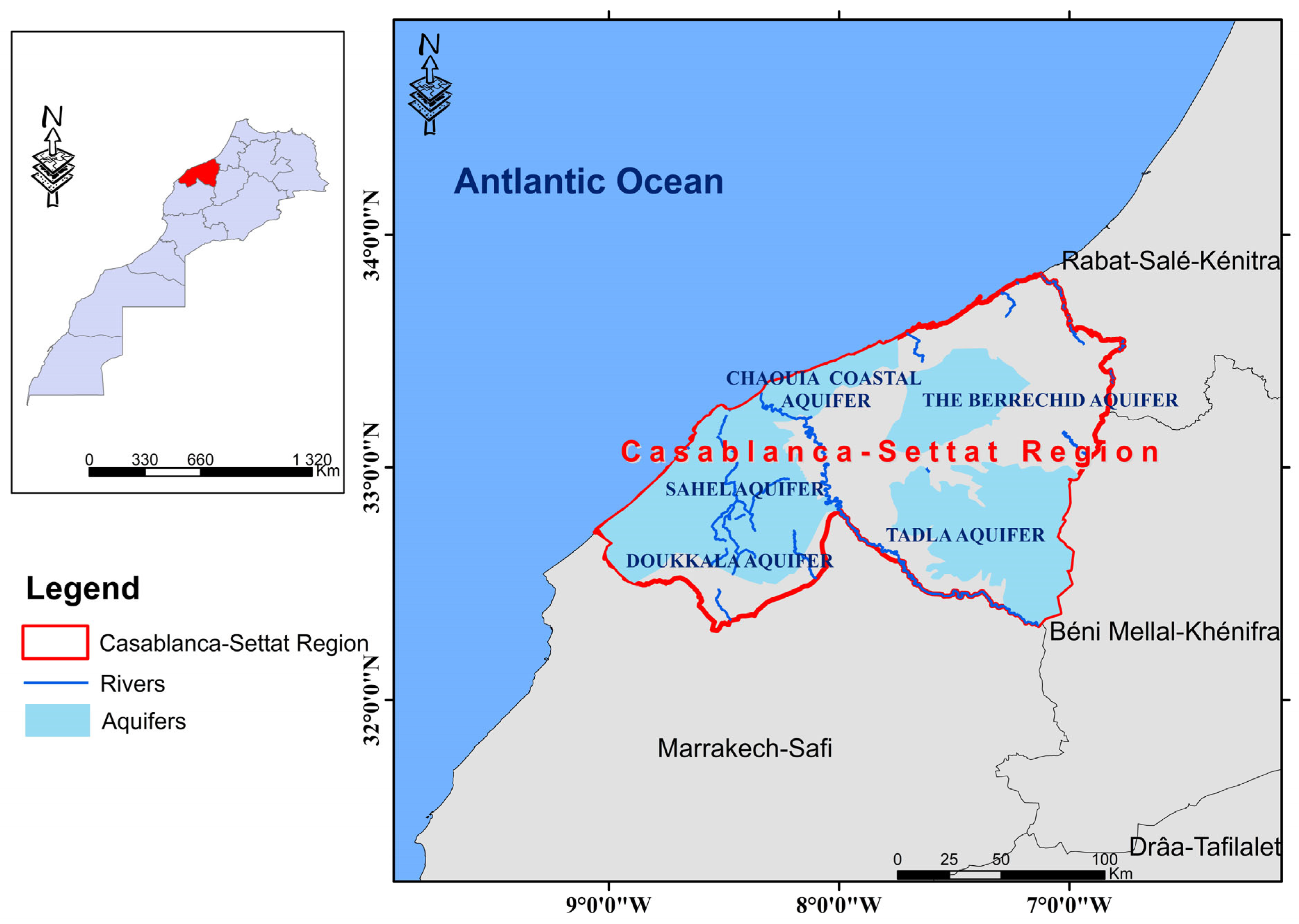

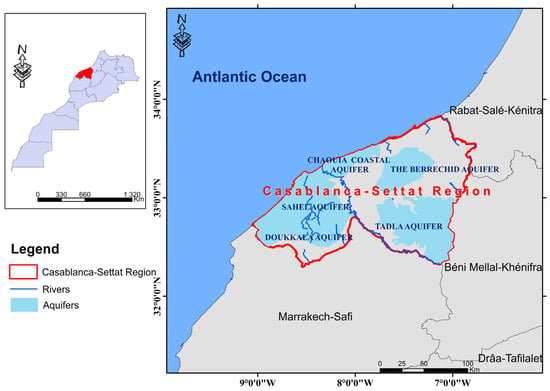

The Casablanca–Settat region of Morocco, positioned along the Atlantic coast (Figure 1), represents a strategic and economically vital zone that faces mounting groundwater challenges. It hosts Morocco’s largest urban hub (Casablanca) and extensive agricultural hinterlands (e.g., Berrechid, Settat, and El Jadida), resulting in complex and competing water demands. While cities rely heavily on groundwater for industrial and domestic use, adjacent farmlands extract substantial volumes for irrigation, especially during the long dry seasons. This imbalance, combined with irregular rainfall, high evapotranspiration, and coastal saline intrusion, has led to widespread aquifer stress and declining groundwater tables.

Figure 1.

Location of the Casablanca–Settat region, Morocco. Source: Aquifer boundaries digitized by the authors based on the official regional monograph of Casablanca–Settat (Ministry of Interior, Morocco).

Traditional monitoring approaches in the region suffer from low spatial resolution and infrequent data updates, making it difficult to detect local depletion trends or inform timely policy actions. In this context, the proposed hybrid ML model offers a robust solution by integrating satellite-derived Terrestrial Water Storage Anomaly (TWSA) data with regional hydro-climatic and LULC variables. This enables high-resolution, spatially explicit forecasting of Ground Water Storage (GWS) anomalies across diverse landscapes and time periods. The model helps identify high-risk zones such as peri-urban agricultural belts prone to over-extraction and inland regions with limited natural recharge. For instance, it can flag potential depletion near Berrechid or highlight increased storage following rainfall in coastal El Jadida. These predictions enable evidence-based decision-making for aquifer recharge projects, groundwater licensing, irrigation scheduling, and drought preparedness. This approach aligns with Morocco’s national water strategy and supports Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) targets related to clean water access and climate adaptation, making it a timely and regionally impactful contribution to groundwater governance.

1.2. Aims and Objectives

This study aims to build a robust hybrid ML model for predicting groundwater anomalies in the Casablanca–Settat region. The core objectives are as follows:

- Data Integration and Model Development: To compile a multi-source dataset (e.g., GRACE/GRACE-FO TWSA and LULC classifications) and construct a hybrid ensemble model combining Huber Regressor (HR), Automatic Relevance Determination (ARD) regression, Kernel Ridge (KR), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Gradient Boosting (GB), and LSTM, with Random Forest (RF) as the final aggregator.

- Model Evaluation: To evaluate the hybrid model’s performance in predicting TWSA using Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and determination coefficient (R2), and to compare its results against individual baseline regression models trained on the same input features.

- Insight Extraction: To generate region-specific insights—such as LULC impact, spatial anomaly clustering, and extreme groundwater zones—to support data-driven hydrological planning.

2. Literature Review

This research has explored the integration of GRACE/GRACE-FO satellite observations with ML and hydrological modeling to better capture spatiotemporal dynamics in GWS. The following literature is categorized into four thematic areas based on methodological approaches and geographic relevance.

2.1. ML-Based Downscaling of GRACE Data

ML models have been widely applied to refine the spatial resolution of GRACE observations. An XGBoost-based model was developed by the authors in [4], which was used for the Upper Indus Plain, utilizing the Famine Early Warning Systems Network Land Data Assimilation System (FLDAS) and terrain features to enhance GWS anomaly (GWSA) detection. But notably, this model lacked Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and LULC inputs, limiting ecological interpretation. A similar three-stage framework built in [5], integrating RF and XGBoost, achieved an R2 of 0.8674 but did not model spatial geolocation features such as latitude and longitude.

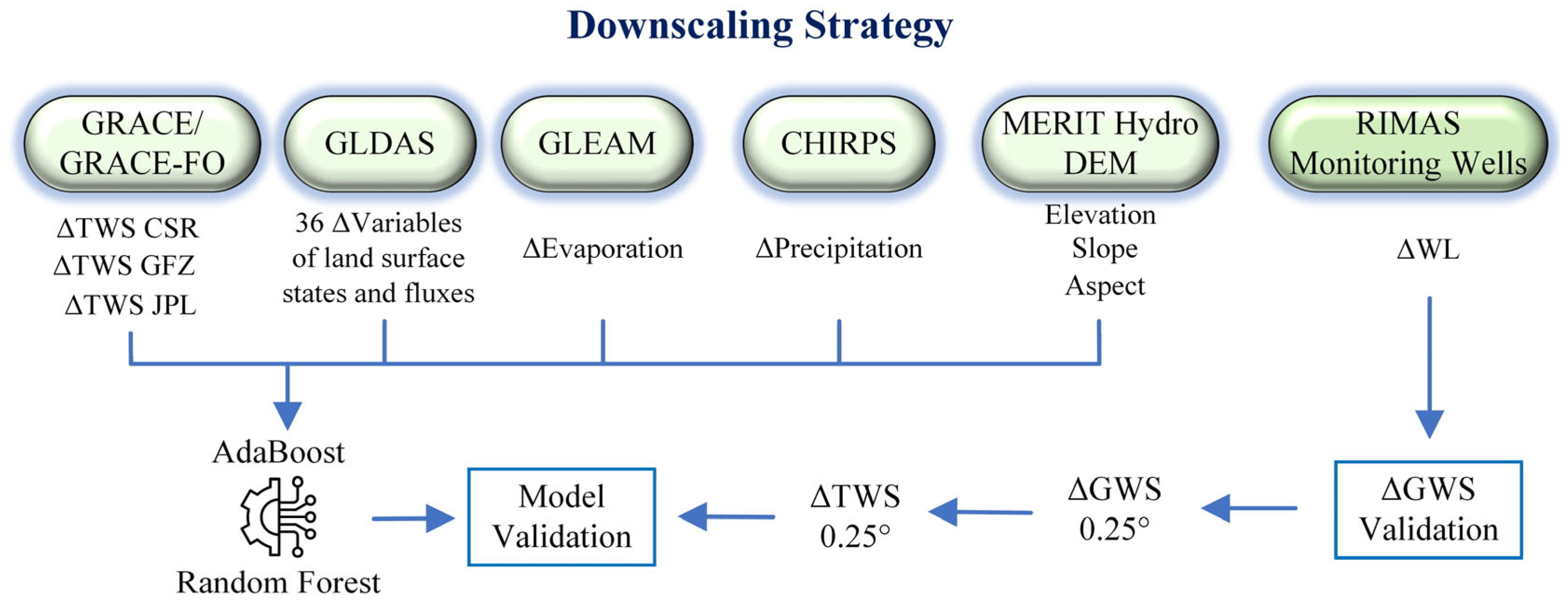

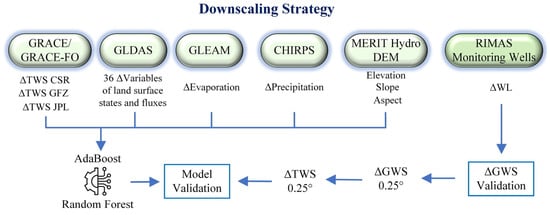

In Hamou-Ali [6], the authors worked on the dataset of the Huang–Huai–Hai (HJH) Plain of China and used a 4 km downscaling model utilizing RF, XGBoost, and LightGBM along with TerraClimate variables. They achieved up to 23% improvement in correlation. Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI) and Actual EvapoTranspiration (AET) were identified as key predictors via SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis. In Morocco, an RF model incorporating NDVI and Land Surface Temperature (LST) inputs successfully generated 1 km TWSA maps validated against 63% of wells, although it excluded runoff dynamics [7]. Moreover, the Amazon Basin saw the application of RF and AdaBoost for downscaling from 1° to 0.25°, capturing a net TWSA gain of +22.24 km3/year while revealing sub-basin heterogeneity. However, it focused primarily on humid regions, limiting broader applicability [8]. Figure 2 illustrates the general GRACE downscaling methodology used in the referenced study, shown here for explanatory purposes.

Figure 2.

GRACE downscaling methodology (reproduced from [8] for illustrative purposes). The diagram summarizes the main steps, including coarse-resolution GRACE/GRACE-FO TWSA data as input, integration of auxiliary high-resolution hydro-climatic and land-surface variables, supervised learning-based disaggregation, and generation of spatially refined TWSA outputs.

Similarly, regression-based downscaling using a GWR model in the Songhua River Basin achieved high accuracy (Nash–Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE) = 0.989), though generalization to agricultural LULC transitions remained unaddressed [9].

2.2. Temporal Forecasting and Gap-Filling of GRACE Time Series

Efforts to resolve temporal discontinuities in GRACE datasets have driven hybrid modeling innovation. A Conventional Neural Network–Long Short-term Memory (CNN–LSTM) model developed and trained in [10], across Indian basins, achieved an R2 score of 92%, and a Mean Squared Error (MSE) = 0.91, offering reliable GWSA reconstruction. Notably, this work lacked LULC awareness. For the Tehran-based database, a non-stationary LSTM model was integrated by the authors in [11]. They used ERA5 and Global Land Data Assimilation System (GLDAS) data to predict monthly TWSA with an R2 = 0.93 and RMSE = 4.75. But on the downside, the spatial heterogeneity was not modeled in this work. For Shandong Province, LSTM, Autoregressive Moving Average (ARMA), Singular Spectrum Analysis (SSA), and Support Vector Machine (SVM) models were tested using GRACE and WaterGAP Global Hydrology Model (WGHM) inputs; SVM yielded the best RMSE = 4.42, but the study did not explore spatial interpolation [12]. For the South Korea-based dataset, CNN–LSTM networks outperformed standalone LSTM models in predicting TWSA based on GLDAS, Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM), and Landsat inputs, although localized feedback processes were underrepresented [13].

A combination of CNN, LSTM, and CNN–LSTM was used for the Ganga Basin-based dataset, with LSTM showing superior performance (RMSE = 0.292), yet ecological and LULC variables were excluded here as well [14]. Meanwhile, a feature attribution study across 254 basins used XGBoost and SHAP values to distinguish spatial versus temporal importance, offering insight. But this work also lacked spatial downscaling [15].

2.3. Groundwater Trend Assessment, Validation, and Sustainability Monitoring

To assess long-term GWS dynamics, GRACE data have been validated using in situ and quality-based indicators. In Iran’s Yazd region, a strong inverse correlation of −0.79 between GRACE-derived GWS and electrical conductivity levels confirmed aquifer depletion. Notably, spatial modeling was not performed in this work [16]. A large-scale analysis across India detected GWS losses as high as −0.75 cm/year in the Indo-Gangetic plain using Mann–Kendall (MK) and Sen’s Linear Regression (SLR) statistical tests, but these are limited by GRACE’s resolution [17].

A 21-year analysis across the Middle East used GRACE to derive a sustainability index, revealing an alarming 5.93 mm/year GWSA depletion and severe stress in 59% of basins; however, the study lacked predictive modeling or input feature disaggregation [18]. In North China, integrated GRACE, groundwater extraction (GWE), and in situ observations were used to assess South-to-North Water Transfer Project (SNWTP) impacts and sustainability indices without incorporating spatial downscaling [19]. Validation against groundwater modeling and observational wells in five Iranian provinces showed GRACE-FO outperformed GRACE, although it remained coarse in resolution [20]. In the Central Kabul River Basin (CKRB) spanning Pakistan and Afghanistan, long-term depletion rates of −7.83 mm/month were observed via GRACE-FO and GLDAS data, though validation yielded only moderate R2 (0.47) with well data [21].

2.4. Integrative and Regional Approaches for GRACE Enhancement

More recent approaches adopt region-specific frameworks integrating GRACE data with ancillary inputs for enhanced monitoring. In Türkiye’s Kizilirmak Basin, integration of FLDAS data with hydrological indices such as the Warm Spell Duration Index (WSDI) successfully detected localized drought periods. Yet, the model did not incorporate NDVI or LULC predictors [22]. Meanwhile, an integrated groundwater sustainability index for North China was developed using GRACE, GRACE-FO, GWE, and hydrological indicators to evaluate SNWTP impacts. However, the study did not apply ML for enhanced spatial granularity [23]. Another SHAP-based feature analysis using XGBoost across Iranian basins provided interpretability into spatial versus temporal drivers, although predictive downscaling and LULC integration were not implemented [24].

2.5. Regional Perspectives on Water Challenges and Modeling Approaches in Morocco

Recent Moroccan studies reflect a growing urgency to address the multifaceted environmental stresses affecting water resources, particularly in the semi-arid and agriculturally critical regions. One such research study [25] highlighted the severity of soil degradation in the Tamdrost watershed, where average erosion rates reach up to 800 T/ha/year, largely driven by topographic and rainfall factors. Their integration of the Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation (RUSLE) with Geographic Information System (GIS) and remote sensing offered thematic maps to guide erosion control in threatened zones, demonstrating how geospatial modeling supports environmental decision-making. Meanwhile, two-dimensional modeling efforts in the Bouregreg estuary [26] have underscored the benefits of hydrodynamic simulations for managing sediment transport and water circulation. These models showed that dredging operations can reduce erosion impacts by approximately 30%, improving both ecological balance and structural resilience in coastal estuarine systems.

In flood-prone Mediterranean regions, deterministic hydrological models have been used with success, achieving an R2 of 0.81 and Nash–Sutcliffe performance indices averaging 0.69, although initial hydrographs remain difficult to predict [27]. Urbanization’s encroachment on natural water systems forms another vital axis of Moroccan water research. Another study emphasized how urban growth exacerbates desertification and groundwater depletion, calling for the integration of remote sensing, geophysical investigations, and water quality assessments to quantify urban runoff contamination and aquifer drawdown [28]. Complementing these technical studies, a bibliometric analysis of Moroccan water research revealed that, despite substantial international collaboration—particularly with France and Spain—there is a relative lack of emphasis on the development of advanced GIS-based solutions for groundwater mapping, pollution tracking, and agricultural planning [29].

2.6. Research Gap

While recent research has made great strides in applying GRACE/GRACE-FO data and ML to groundwater monitoring, there are still some clear gaps. Many existing models tend to focus either on improving spatial resolution or predicting temporal trends—but rarely both together. Even in well-known studies that use strong algorithms like RF or LSTM, key environmental factors such as LULC, NDVI [30,31,32], or evapotranspiration are often left out. This makes it harder to understand how surface conditions actually relate to what’s happening underground. Moreover, even when models perform well, the insights they generate are not always transformed into region-specific maps or tools that can directly help policymakers on the ground.

In the case of Morocco, this gap becomes even more noticeable. Although researchers have performed important work on issues like soil erosion, urban sprawl, and flood modeling, few have developed models that combine satellite data with advanced ML to predict groundwater changes in a specific region. For example, in areas like Casablanca–Settat, where both cities and farms are putting pressure on water resources, there is a real need for robust tools that can not only forecast groundwater trends but also show where the problems are emerging [33,34]. Thus, this study addresses this by building a hybrid model that brings together satellite data, climate records, and LULC details to produce accurate, high-resolution predictions. The goal is to turn complex data into practical insights that support smarter, more sustainable groundwater management.

3. Methodology

The methodology adopted in this study follows a structured framework. This framework is designed to predict TWSA across the Casablanca–Settat region. TWSA serves as a proxy for groundwater storage anomalies. The process begins with the acquisition and preparation of satellite and environmental datasets. It continues with data cleaning, normalization, and feature engineering [33,35].

3.1. Dataset Collection and Pre-Processing

Publishing after 2020 reflects an enhanced comprehension of sustainable development. The primary variable analyzed in this study is the TWSA, which reflects changes in the total volume of water—including groundwater, soil moisture, and surface water—within a specific region. TWSA values were sourced from NASA’s GRACE and GRACE-FO satellite missions, which use gravity measurements to monitor large-scale hydrological shifts globally. These datasets were accessed through the publicly available GRACE portal (https://grace.jpl.nasa.gov), accessed on 10 September 2025. The GRACE and GRACE-FO missions are separated by a known observational gap between mid-2017 and mid-2018. In this study, this temporal discontinuity was explicitly accounted for during data preprocessing by treating the two missions as a continuous but segmented time series, without imposing artificial interpolation across the gap. Model training and evaluation were therefore conducted only on periods with available observations, preserving the physical integrity of the time series. To build a reliable prediction model, the following environmental and geographic features were incorporated [6]:

- LULC: Categorical data indicating surface types (e.g., urban, forest, and agricultural), later one-hot encoded to reflect their influence on local water retention.

- Climate and Hydrological Indicators: These include Precipitation_mm, Evapotranspiration_mm, Temperature_C, Soil_Moisture_mm, and Runoff_mm, sourced from satellite-based datasets like GLDAS. These indicators capture water balance and hydrological dynamics.

- NDVI: Representing vegetation health and land cover variation, it is included as a key predictor due to its influence on evapotranspiration and soil water retention.

- Topographic elevation data were obtained from a Digital Elevation Model (DEM) and used as a static predictor to account for spatial variability in groundwater recharge and storage conditions.

- Geospatial Attributes: Latitude and Longitude are retained for spatial mapping, while Spatial_Resolution_km and Downscale_Method provide metadata for spatial fidelity.

- All spatial data points were mapped to a grid covering the Casablanca–Settat region and resampled to monthly intervals. Each data record represents a unique combination of location and time, along with its associated environmental features and corresponding TWSA values. While the spatial domain consists of approximately 200 grid cells, the final dataset contains multiple spatio-temporal samples derived from monthly observations across all grid cells.

For each monthly time step, the GRACE-derived TWSA value corresponding to the parent coarse-resolution grid cell was assigned to all fine-resolution grid cells contained within that footprint, while spatial differentiation was learned through the associated high-resolution auxiliary predictors. The combination of remotely sensed water data with climate and LULC variables enables the model to capture complex interactions affecting groundwater dynamics. Using open-access and globally trusted sources ensures transparency and reproducibility of the work.

3.2. Spatial Downscaling Strategy

The native spatial resolution of GRACE and GRACE-FO satellite data is approximately 1° × 1°, which translates to a surface area of around 110 km × 110 km ≈ 12,100 km2 per grid cell near the equator, shown in Equation (1) [36].

However, this resolution is too coarse for regional decision-making in water-scarce zones such as Casablanca–Settat. To make the groundwater anomaly predictions actionable at a local level, a spatial downscaling framework was employed to translate GRACE-derived TWSA data into a 10 km × 10 km resolution, resulting in 100 km2 per grid cell. The total study area spans ~20,000 km2 and was subdivided into 200 downscaled grid cells, calculated in Equation (2).

To achieve this, a supervised regression-based disaggregation approach was adopted. Coarse TWSA values from GRACE were spatially mapped and redistributed using high-resolution auxiliary variables, including precipitation, evapotranspiration, soil moisture, elevation, and LULC. These variables were resampled or natively available at or near the target resolution (10 km), sourced from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectrometer (MODIS) dataset described in the next section [37]. Each high-resolution covariate was assigned to one or more of the 200 grid cells using spatial mapping techniques, enabling fine-scale feature extraction. The GRACE-based coarse TWSA values were then used as labels in a training dataset, where each downscaled grid point became a sample, and the high-resolution variables became the predictors [38,39]. Although the same coarse-resolution GRACE TWSA value is assigned to multiple fine-resolution grid cells within a given month, these samples remain distinct due to their different auxiliary predictor values. During model evaluation, temporal independence is preserved by applying a chronological train–test split, ensuring that all samples from the same time period are assigned exclusively to either the training or testing subset. This prevents information leakage despite the presence of repeated labels within individual time steps [40].

A hybrid ML model was used to learn the non-linear mapping as shown in the following Equation (3):

where P is precipitation, ET is evapotranspiration, SM is soil moisture, and f represents the trained hybrid model function.

The resulting model generated 200 localized TWSA estimates, each representing a 10 km × 10 km (100 km2) spatial unit across the Casablanca–Settat region, allowing more precise monitoring and forecasting of groundwater fluctuations.

3.3. Data Pre-Processing

Preparing the dataset for hybrid modeling is an essential step that directly affects the accuracy and stability of the model. This process involves several key stages: data cleaning, encoding, normalization, reshaping for sequence models, and constructing feature interactions. These steps collectively ensure that all the input variables are numerically coherent and aligned with the expectations of the downstream algorithms.

The raw data may contain missing values in the input datasets, primarily arising from occasional gaps in satellite retrievals, reanalysis assimilation issues, or temporal inconsistencies during data aggregation, rather than from sensor malfunction. Given the relatively low proportion of missing data and the use of monthly aggregated hydroclimatic variables, mean imputation was applied as a simple and stable strategy to preserve temporal continuity without introducing artificial variability. These missing values are addressed using mean imputation, as depicted in Equation (4) [41,42,43].

where xi is the imputed value for feature i, xij is the jth value of feature i, and n is the total number of samples.

Outliers are handled by clipping values beyond the 1.5× interquartile range (IQR), ensuring the model is not biased by extreme data points, as shown in Equations (5) and (6), respectively.

where x is the original value, Q1 and Q3 are the 25th and 75th percentiles, and xclipped is the adjusted value within the IQR threshold.

The IQR-based clipping defined in Equations (5) and (6) was applied only to continuous hydroclimatic predictors (e.g., precipitation, evapotranspiration, soil moisture, and vegetation indices), while categorical variables such as LULC classes were excluded. Thresholds were examined to ensure that physically plausible extreme values were preserved and that only statistically anomalous outliers were limited. Further, the LULC variable is a categorical input. It is encoded using one-hot encoding, where a feature x(i) with k distinct categories is transformed into a k-dimensional binary vector. To align the scale of input variables, min-max normalization is applied as shown in Equation (7). It rescales each value x to a range of [0, 1]:

where x is the original feature value, and xnorm is its normalized form within [0, 1] based on its column’s min and max. This improves model convergence and stability, especially for gradient-based learners and neural networks [44,45,46].

3.4. Baseline Models and Hybrid Model Architecture

To benchmark the performance of the proposed hybrid model, the following four baseline regression algorithms were implemented: linear regression, ridge regression, decision tree, and gradient boosting base. Each model was independently trained and evaluated using the same feature set to ensure consistency. These baselines helped in establishing a reference point for comparison and in understanding the individual contribution of different learning paradigms [33]. The hybrid regression model integrates several ML algorithms that operate on different statistical principles to improve the robustness and accuracy of groundwater storage prediction. By combining linear, non-linear, tree-based, and temporal models, this architecture captures a wide variety of data patterns and relationships. The final TWSA prediction is obtained using a stacking ensemble strategy, where the outputs of multiple base learners are combined through an RF meta-learner [47].

where denotes the final predicted TWSA, represents the prediction of the k-th base learner for input feature vector x, K = 6, K is the number of base learners (HR, ARD, KR, KNN, GB, and LSTM), and denotes the RF meta-learner. In this framework, the meta-learner learns a non-linear mapping between the base-model predictions and the target TWSA, allowing adaptive combination of individual model outputs rather than a fixed or voting-based aggregation.

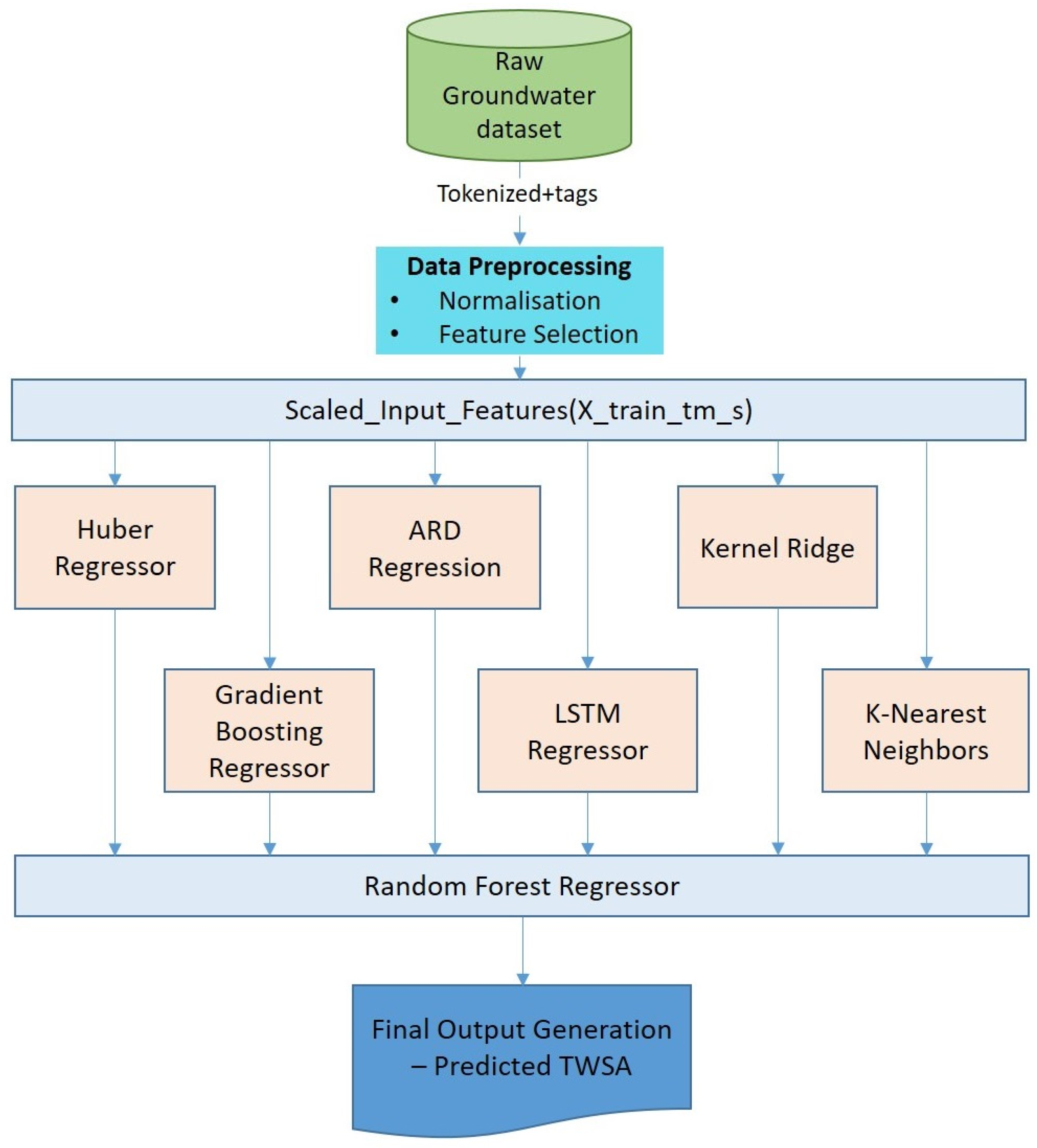

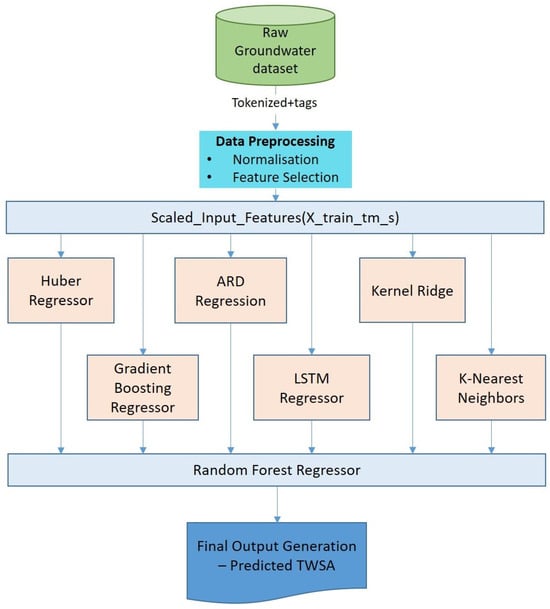

The proposed hybrid model pipeline shown in Figure 3 is designed to leverage a diverse ensemble of ML algorithms to accurately predict TWSA based on groundwater-related features. The pipeline begins with a raw, open-source groundwater dataset comprising various hydro-meteorological indicators [48]. This dataset is first subjected to semantic tokenization and contextual tagging, enabling a structured mapping of variables such as precipitation, evapotranspiration, and soil moisture with their corresponding timestamps and spatial characteristics. This annotated data then undergoes a preprocessing phase where the normalization process is used to scale all the data such that all features are in the same range; thus, the high values of the features have a greater numerical range. Further, the correlation-based filtering and reduction in multicollinearity are employed to choose relevant features that can be used to strengthen the generalizability of the model [38,39,49].

Figure 3.

Architecture of the proposed stacked ensemble regression framework, in which predictions generated by the base learners (HR, ARD, KR, KNN, GB, and LSTM) are stacked and provided as input features to a Random Forest meta-learner to produce the final TWSA estimate.

After that, the scaled input feature set is introduced into a hybrid ensemble with six different models, including HR, ARD, KR, KNN, LSTM, and GB. All these models add their own mathematical lens to the data distribution: ARD adds a Bayesian view of automatic determination of relevance, while LSTM adds the dynamics of temporal dependencies in between sequences. The process of outputs of the six learners, in the embodiment of regional and global patterns, as well as linear and nonlinear features, is sequentially transferred to an RF Regressor. The RF acts as a meta-learner in a stacked ensemble regression framework, learning a non-linear mapping between the base learners’ predictions and the target TWSA values [50,51]. The last result is the statistical prediction of the TWSA, and it is learned as a non-linear combination of statistical inference, time learning, and stacked ensemble regression.

The importance of each model and its role in the hybrid framework is explained in Table 1.

Table 1.

Role of each model in the hybrid framework. Model descriptions are based on standard definitions of the corresponding algorithms in the machine learning literature (e.g., scikit-learn documentation and foundational ML tutorials).

3.5. Model Training and Evaluation Strategy

Data Partitioning and Validation Approach: All the data was divided into training and test segments with a temporal division of 80:20. The temporal split was performed chronologically, with the earliest 80% of the monthly time series used for model training and the most recent 20% reserved for independent testing, ensuring that no future information leaked into the training process. The 5-fold cross-validation was applied exclusively within the training subset to tune model parameters and assess robustness, while the test subset remained completely unseen until the final evaluation. This method minimizes the variability in the estimation of the model and confidently estimates the stability of the models in unrevealed data sets [52].

For LSTM training, the Adaptative Moment Estimation (Adam) optimizer was employed. This optimizer is a gradient-based algorithm that adaptively adjusts learning rates to ensure efficient and stable neural network training. The input data was reshaped to meet the 3D input format expected by LSTM layers—structured as [samples, time_steps, features]. A batch size of eight was chosen to promote stable learning, while the number of epochs was limited to three due to computational constraints, with early stopping mechanisms applied to prevent overfitting. Although the maximum number of epochs was set to three to limit overfitting and computational cost, early stopping was included as a safeguard mechanism to terminate training if no improvement in validation loss was observed between successive epochs [53,54]. For this model, temporal ordering was strictly preserved, and the chronological train–test split ensured that model evaluation was performed on future time periods relative to training, thereby preventing temporal information leakage. The RF and GB models were trained using all available CPU cores to maximize scalability and reduce training time. To measure model performance comprehensively, the following evaluation metrics were used:

- MAE: Measures the average magnitude of prediction errors.

- RMSE: Penalizes large errors more heavily, important for hydrological extremes.

- R2 Score: Indicates how well the model explains the variance in the target variable.

This structured training and evaluation pipeline guarantees fairness in comparison across models, stability in prediction, and transparency in model decisions.

4. Results

4.1. Exploratory Data Analysis

Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) plays a critical role in understanding the structure, distribution, and interactions within the dataset before model development. In this study, EDA was conducted on the merged satellite, climatic, and LULC dataset to examine the underlying patterns influencing groundwater fluctuations, particularly the TWSA.

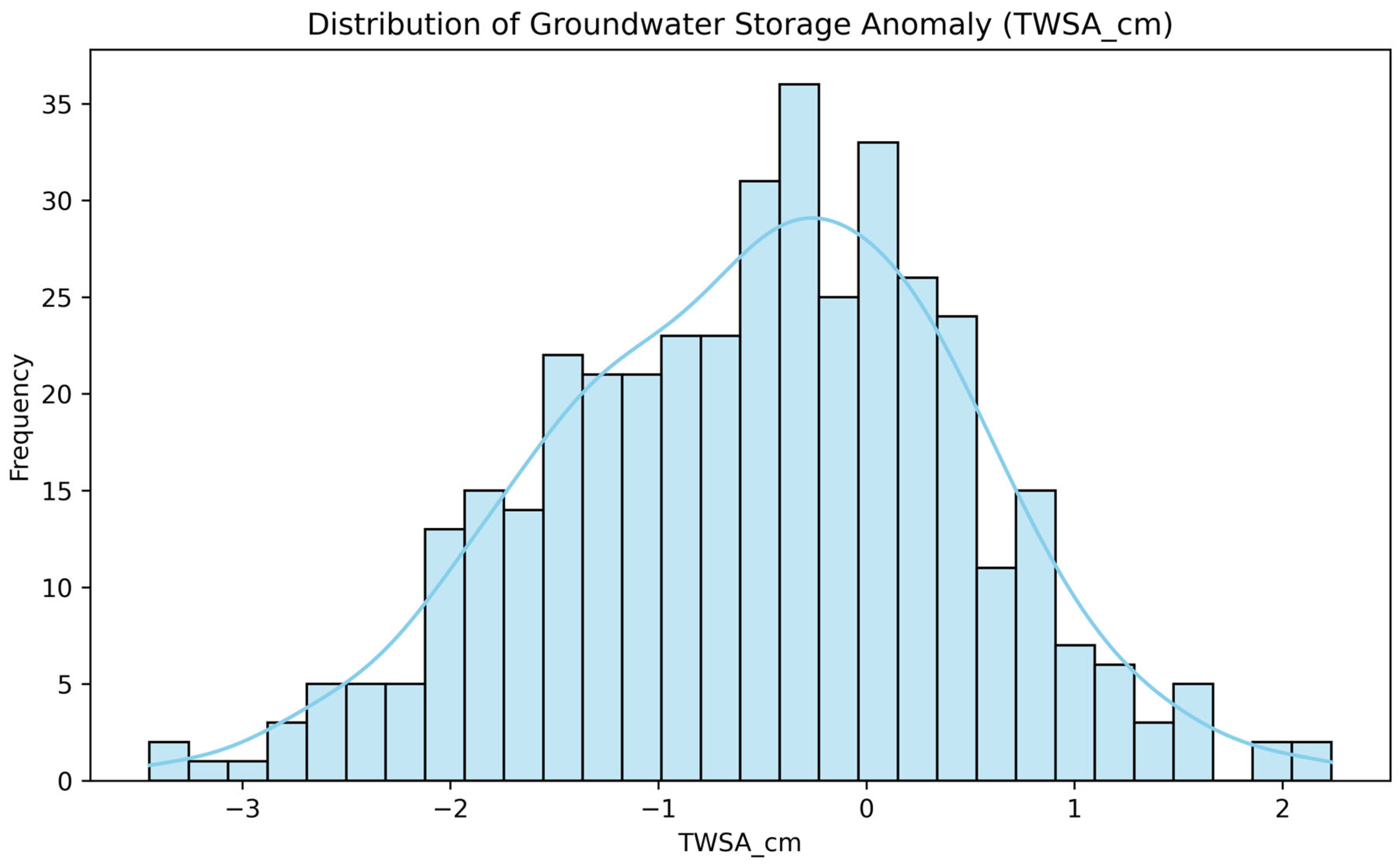

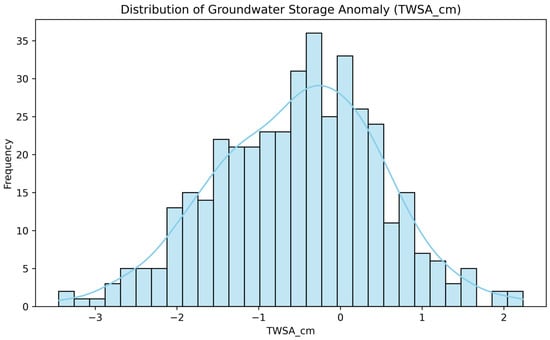

4.1.1. Distribution of TWSA

The plot in Figure 4 illustrates the frequency distribution of the TWSA values, range between −1 to 1. It shows that TWSA measurements are approximately normally distributed, with a mild skew toward negative values, indicating that groundwater depletion episodes are more frequent than excess storage periods.

Figure 4.

Histogram of TWSA values showing a skewed distribution with more frequent groundwater deficits.

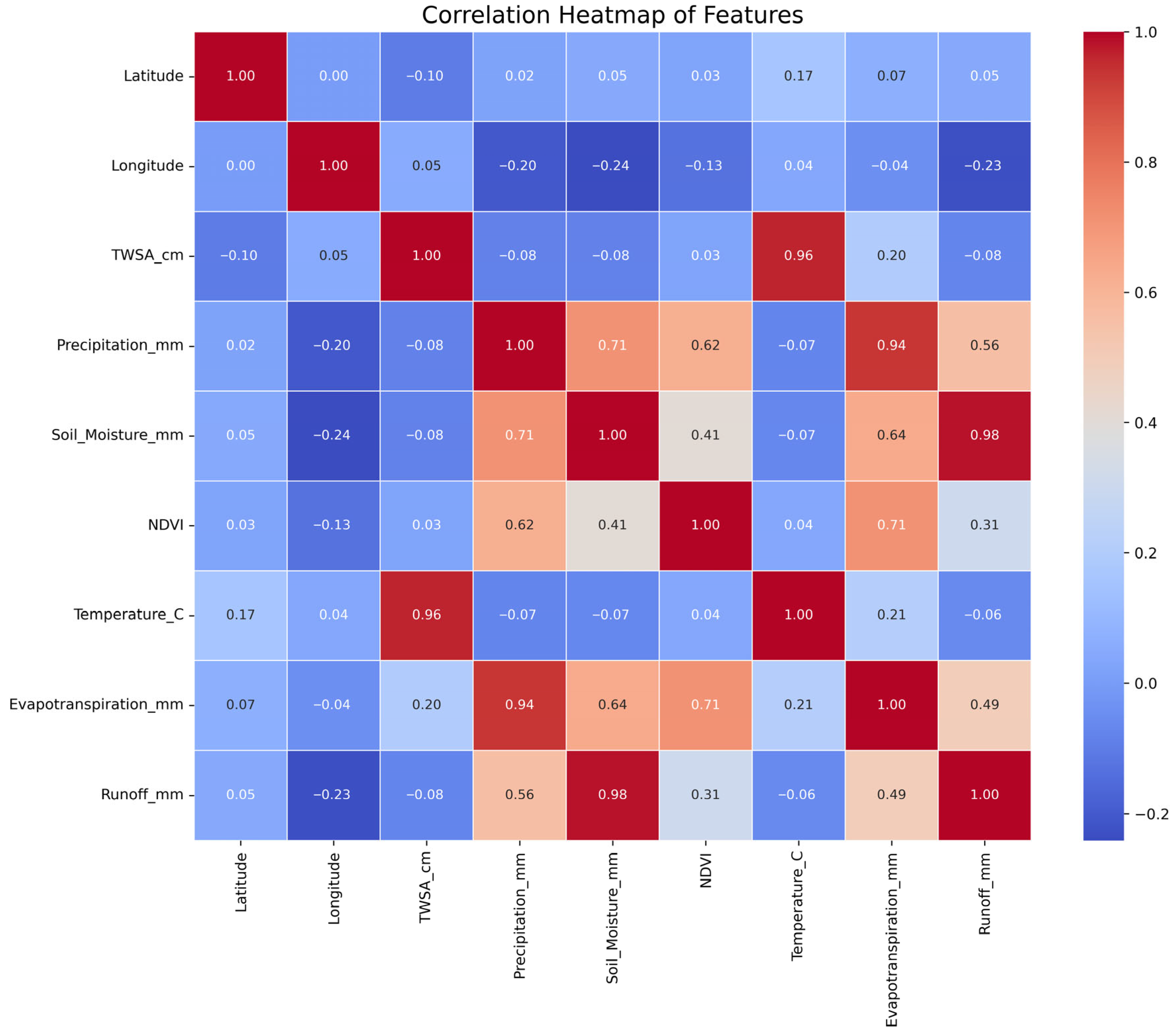

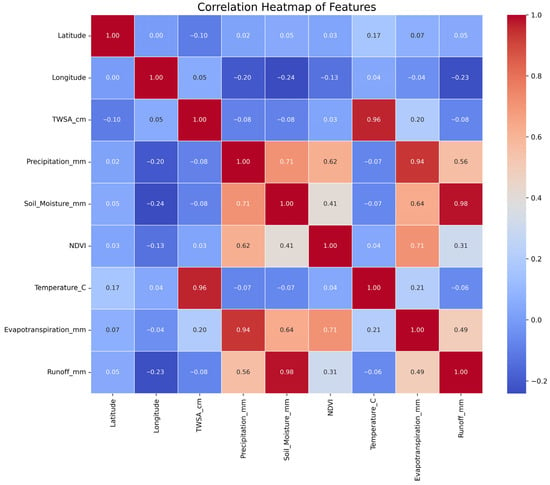

4.1.2. Correlation Heatmap of Features

The correlation heatmap (Figure 5) visualizes the pairwise Pearson correlation coefficients among all features in the dataset. The TWSA has highly correlated with hydro-climatic, herein, temperature (0.96) and between then such as soil moisture and runoff (0.98).

Figure 5.

Correlation heatmap revealing key relationships between TWSA and hydro-climatic variables.

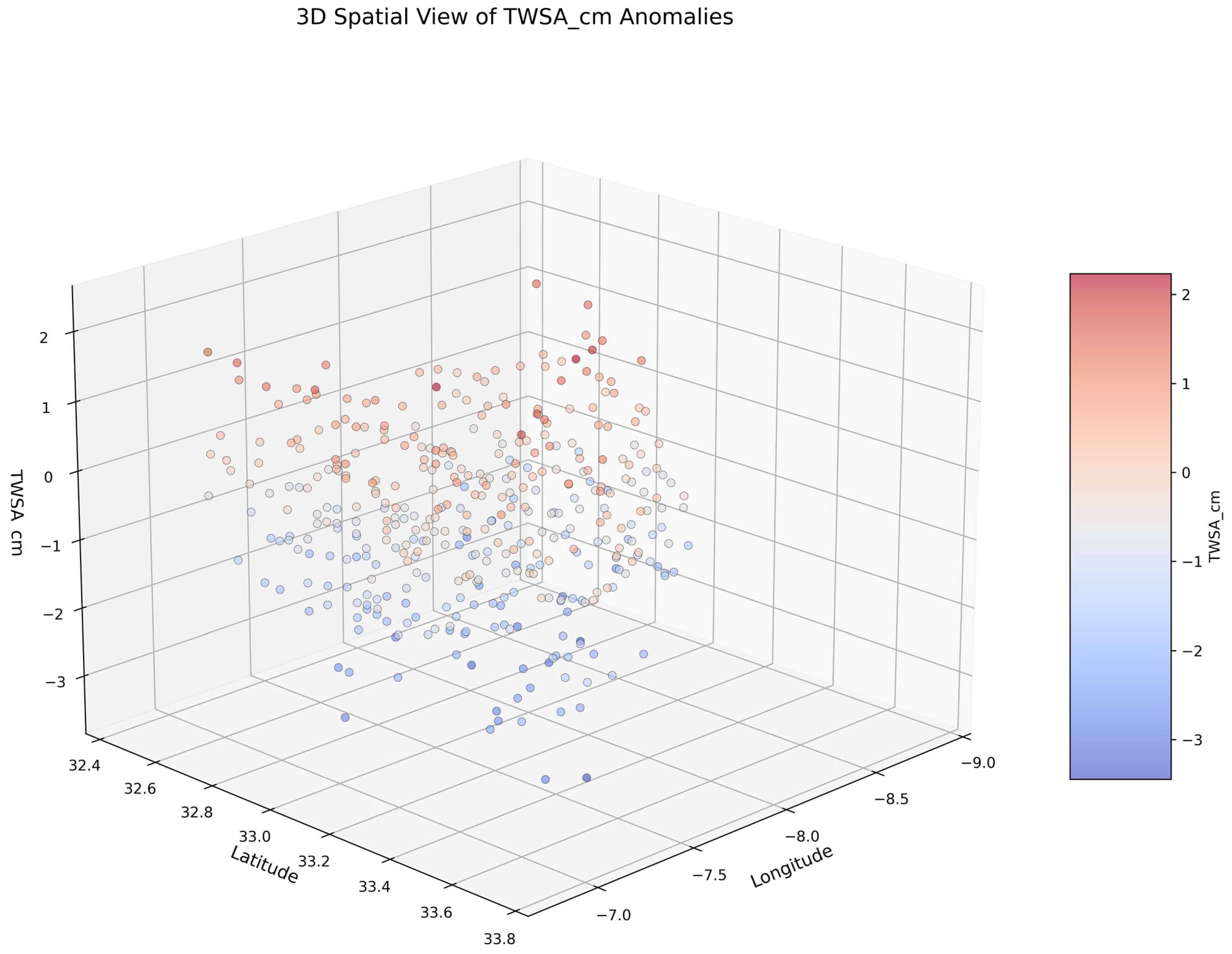

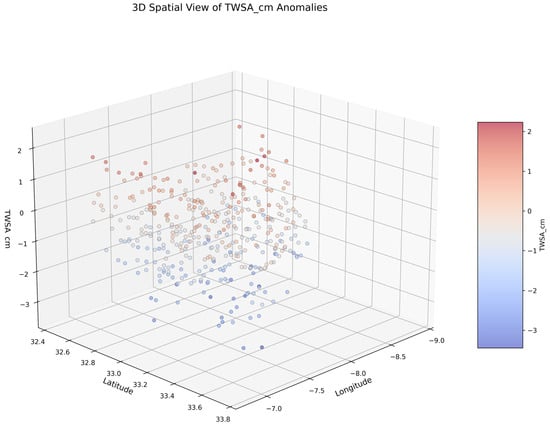

4.1.3. Three-Dimensional Scatter Plot (TWSA vs. Latitude vs. Longitude)

The three-dimensional (3D) scatter plot in Figure 6 provides a spatial-temporal view of TWSA variation across geographic coordinates. This plot is particularly helpful in identifying spatial outliers and regional extremes in groundwater trends.

Figure 6.

Three-dimensional scatter plot of TWSA against latitude and longitude, revealing spatial patterns.

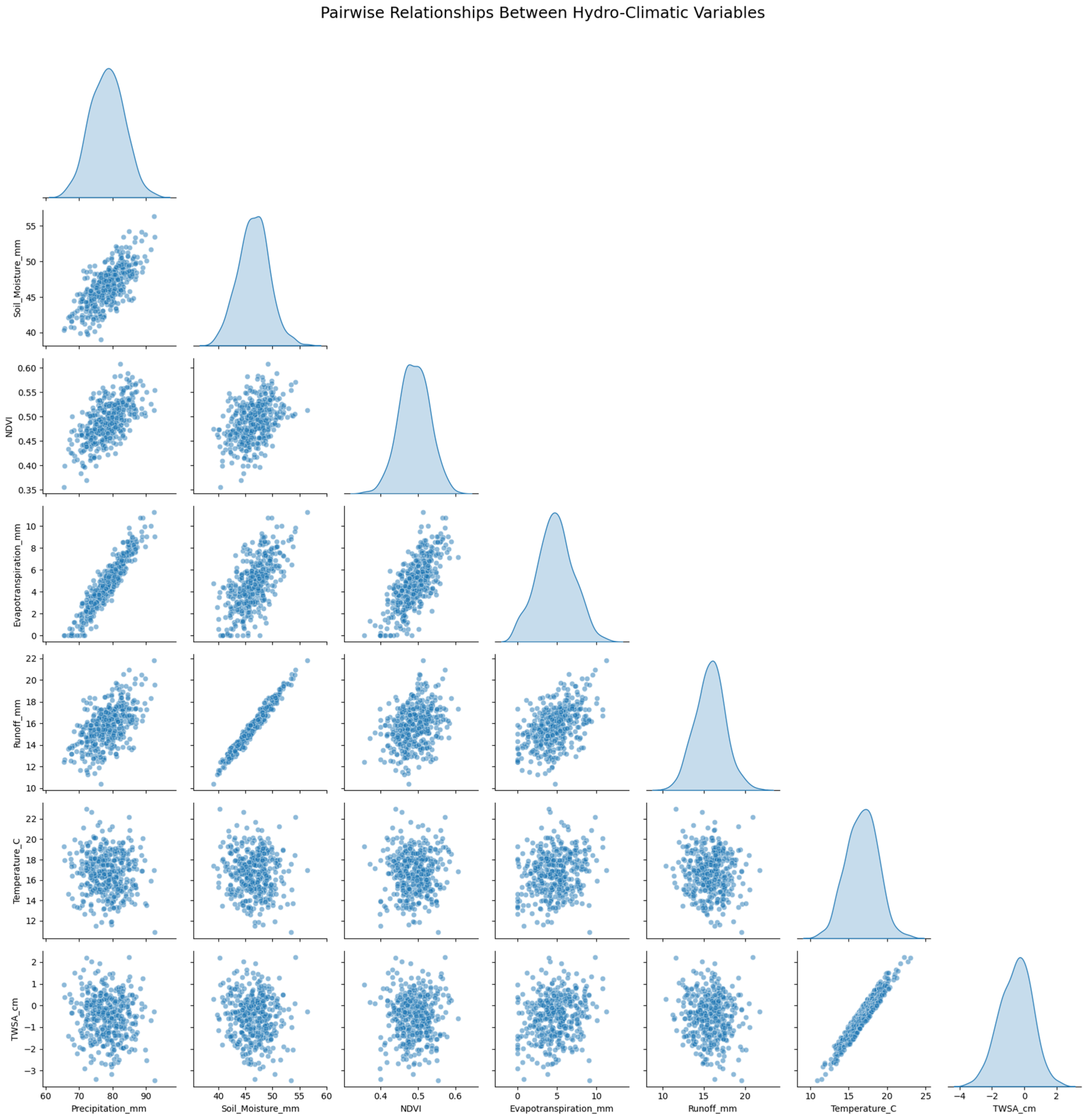

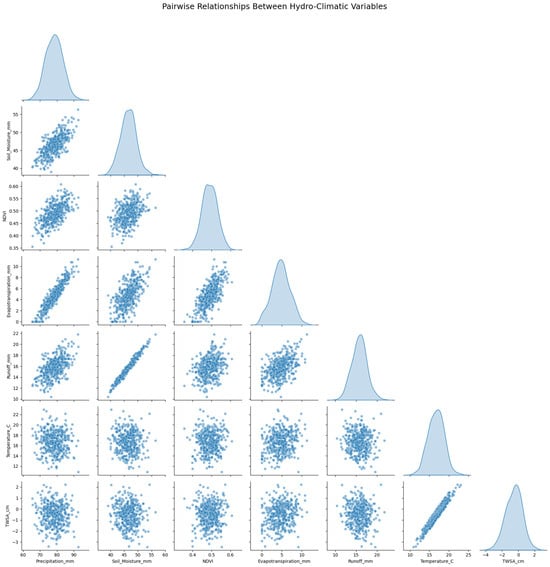

4.1.4. Pairwise Relationships Between Hydro-Climatic Variables

The pairwise plot in Figure 7 visualizes the joint distributions and correlations between TWSA, precipitation, evapotranspiration, temperature, and LULC indices. It reveals linear trends between TWSA and precipitation, as well as non-linear associations with evapotranspiration and land cover. These relationships guide feature selection and model tuning.

Figure 7.

Pairwise plots showing interactions between TWSA and key environmental features.

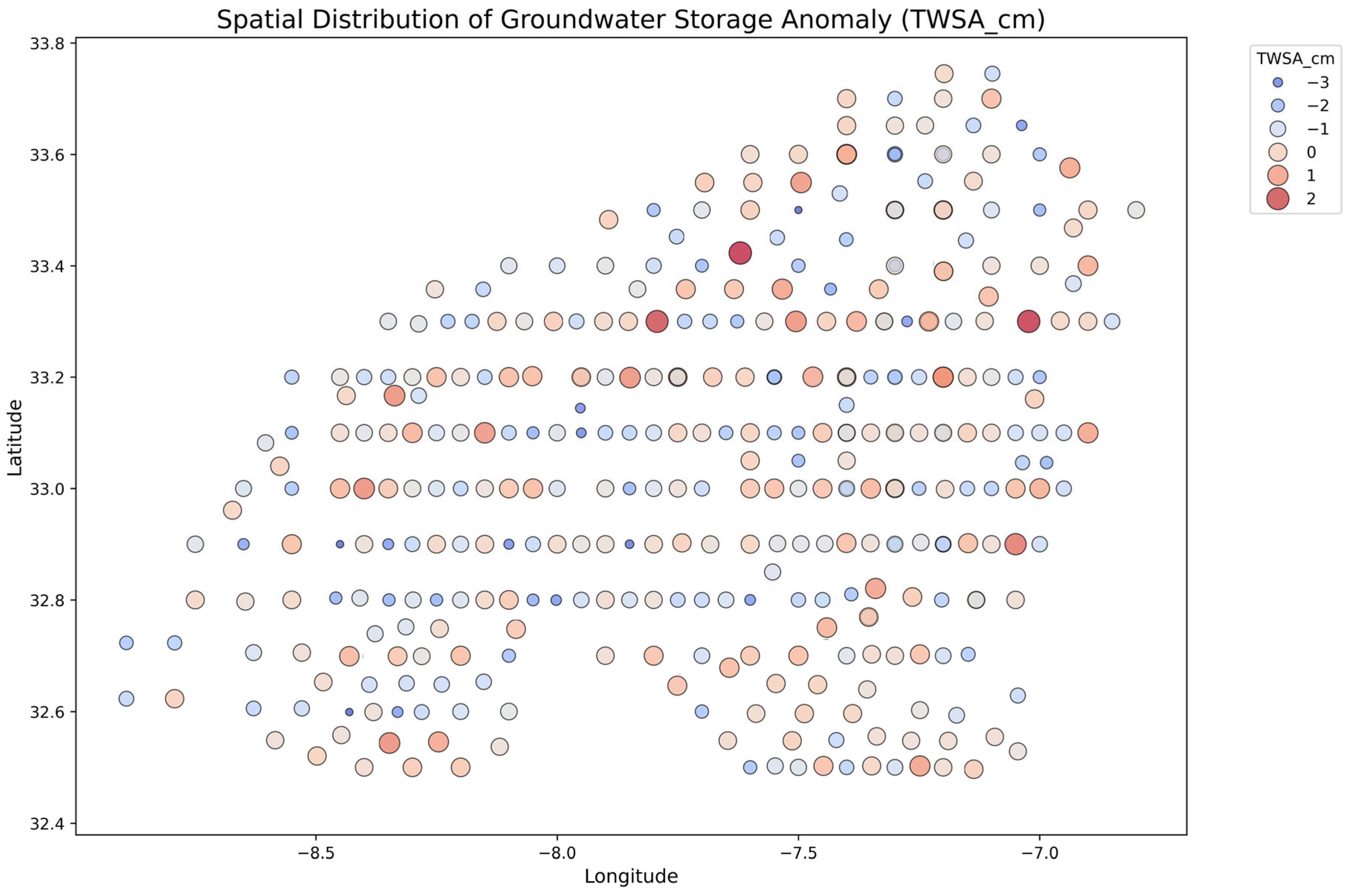

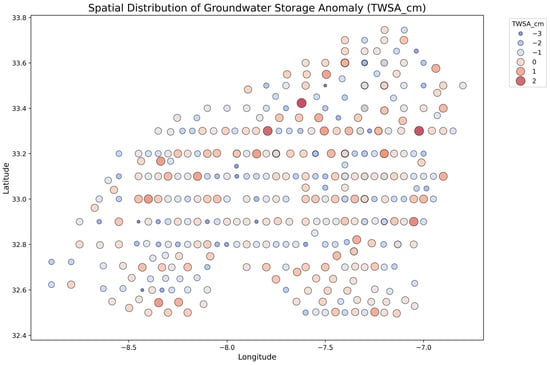

4.1.5. Spatial Plot of TWSA_cm (Bubble Map)

This spatial visualization (plotted in Figure 8) maps TWSA values over the Casablanca–Settat region. It demonstrates geographical disparities in groundwater availability, with coastal and lowland zones showing greater depletion. This helps assess the spatial generalizability of the model.

Figure 8.

Spatial bubble map illustrating regional variations in groundwater storage.

Together, these visualizations provide a comprehensive understanding of the dataset’s statistical and spatial properties.

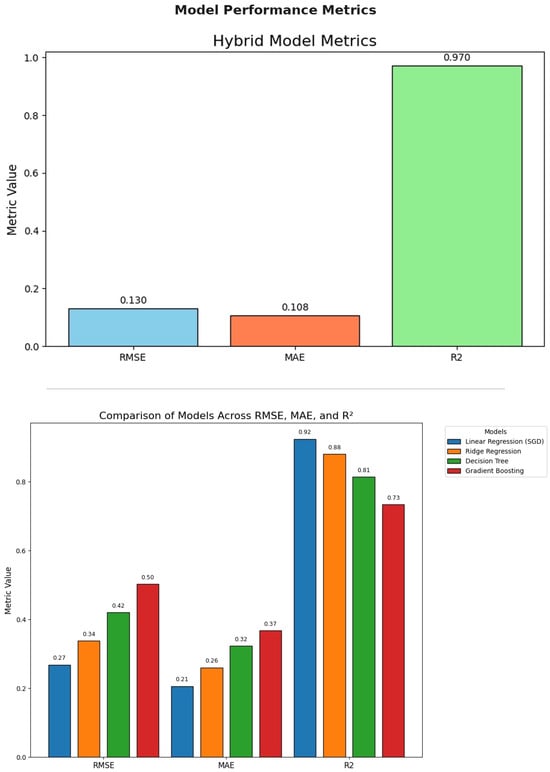

4.2. Model Evaluation

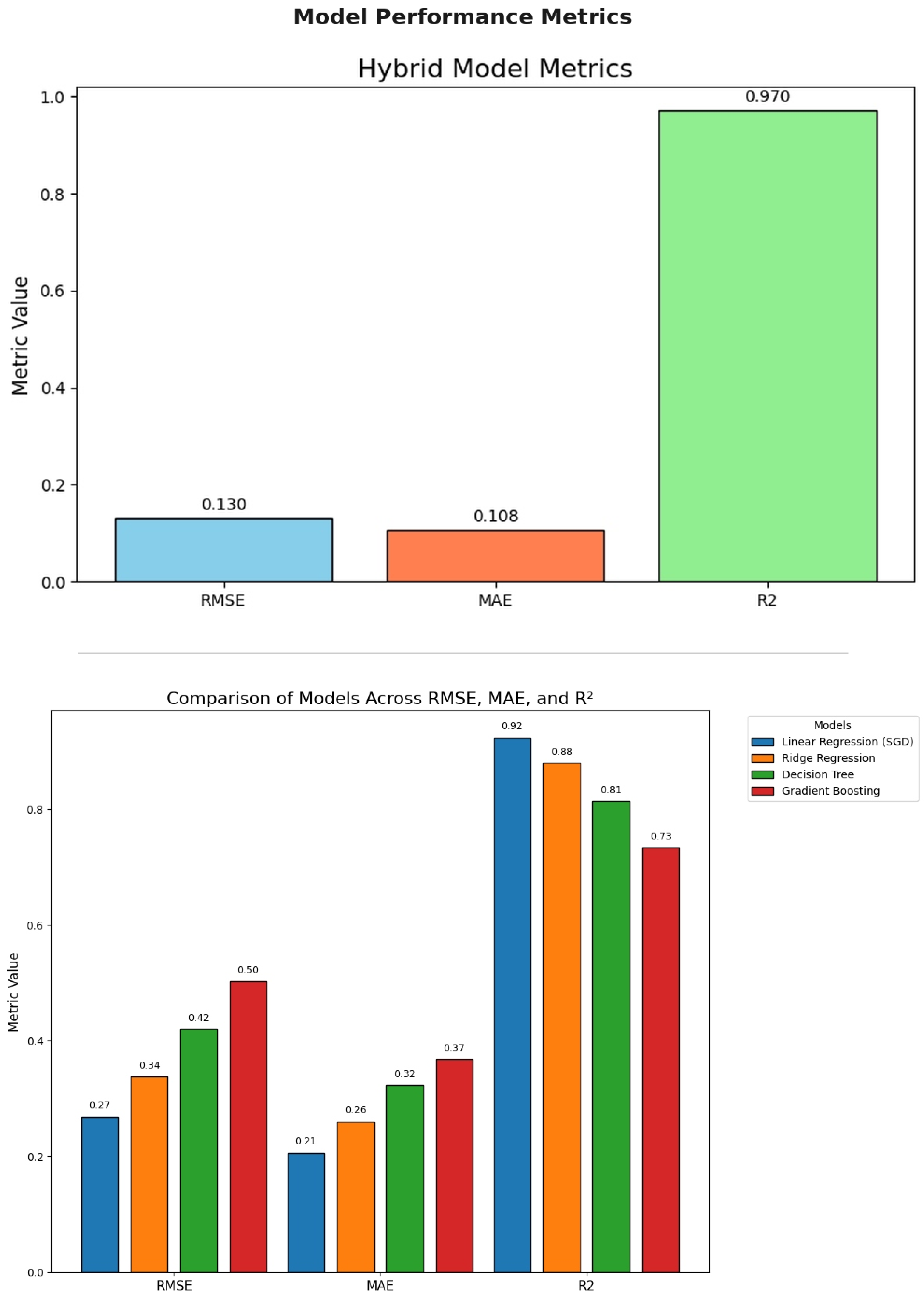

The baseline models were selected to represent a broad spectrum of statistical learning strategies, including linear, kernel-based, decision-tree, and boosting-based methods. The proposed hybrid ensemble model was evaluated using the same metrics as the baseline models—RMSE, MAE, and R2 Score [32,55]. Table 2 summarizes the evaluation thus made. A visual comparison of model performance across these metrics is provided in Figure 9.

Table 2.

Model evaluation comparison.

Figure 9.

Comparison of models across RMSE, MAE, and R2, and model performance metrics.

Baseline Models’ Performance Insights: linear regression outperformed other baseline models, achieving the highest R2 score and lowest RMSE/MAE. This suggests that the underlying data may have strong linear components that are effectively captured by the stochastic gradient optimization. Ridge regression, while slightly less accurate, still performed well. Decision tree performance declined due to its tendency to overfit on small local patterns, especially in datasets with temporal dependencies and continuous variables. The gradient boosting base, surprisingly, showed a lower R2. This may be attributed to shallow tree depths or insufficient learning iterations, which limited the model’s capacity to learn complex interactions. In this study, the gradient boosting model was configured with a limited number of estimators and shallow tree depth (n_estimators = 50, max_depth = 2, learning_rate = 0.02, subsample = 0.8), which may restrict its ability to capture complex non-linear relationships compared to more flexible ensemble architectures. The gradient boosting base was intentionally configured as a conservative baseline with limited depth and learning capacity, and its lower performance is therefore attributed to constrained model flexibility rather than inherent deficiencies in the input data.

Hybrid Model Performance: The hybrid model demonstrated superior performance due to the synergistic integration of multiple learning paradigms. Unlike baseline models that specialize in capturing either linear, non-linear, or local relationships in isolation, the hybrid model combines these strengths into a single predictive system. The key factors contributing to this improvement include the following:

- Multi-Perspective Learning: By incorporating diverse regressors (HR, ARD, KNN, KR, and LSTM), the hybrid model captures a wider spectrum of statistical patterns—from temporal dependencies to local clusters and global trends.

- Error Compensation: Weaknesses in individual models are balanced by strengths in others. For instance, LSTM can model temporal dependencies missed by KNN, while ARD enhances feature selection that benefits kernel methods.

- RF Aggregation: The meta-learner (RF) combines model outputs in a non-linear way, applying internal bootstrapping and meta-learning aggregation. This reduces prediction variance and improves generalization, especially in the presence of noisy or correlated features [35].

Feature Stability via Preprocessing: Prior feature normalization and interaction construction ensured consistent scaling across learners, improving convergence and learning quality.

4.3. Insights from TWSA Analysis

To further understand the spatial and contextual implications of groundwater storage patterns in the Casablanca–Settat region, multiple visualization techniques were employed using the predicted TWSA values. These visualizations not only validate model behavior but also uncover geographic trends, LULC influences, and extreme anomaly zones that are critical for sustainable groundwater resource planning [56].

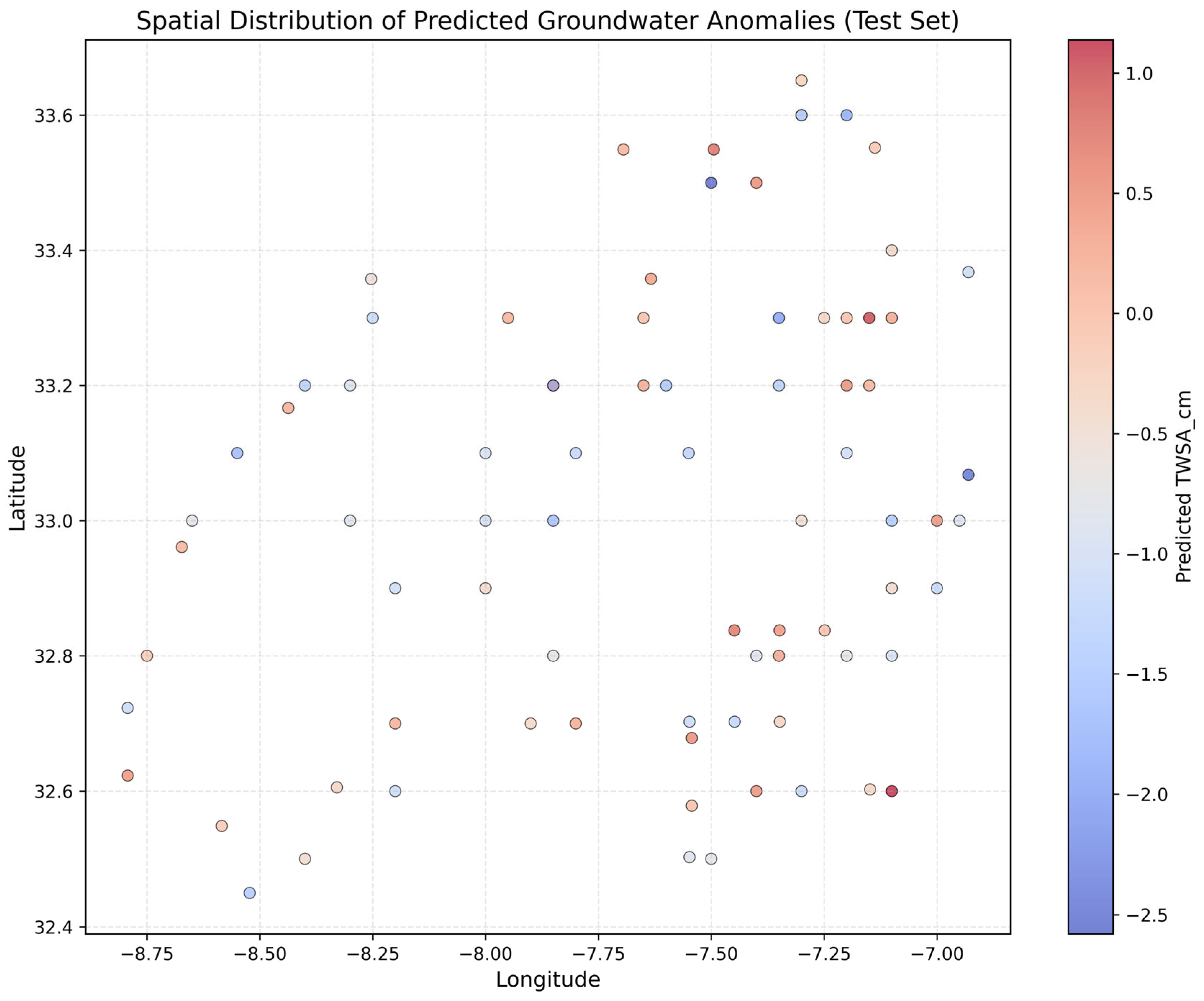

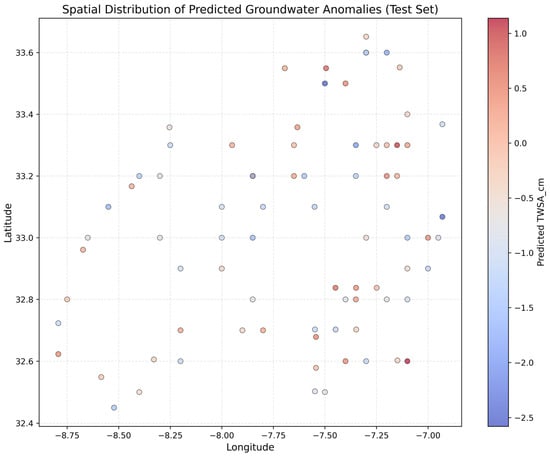

Spatial Scatter Plot of Predicted Anomalies: The scatter plot of predicted TWSA values in Figure 10 reveals clear spatial heterogeneity across the region. Each point represents a georeferenced prediction of groundwater storage deviation from the climatological norm:

Figure 10.

Spatial scatter plot of predicted TWSA (cm).

- Blue markers indicate negative anomalies, highlighting zones under stress or depletion, which may require immediate intervention or investigation.

- Red markers denote positive anomalies, possibly driven by recent rainfall, surface recharge, or low extraction activity.

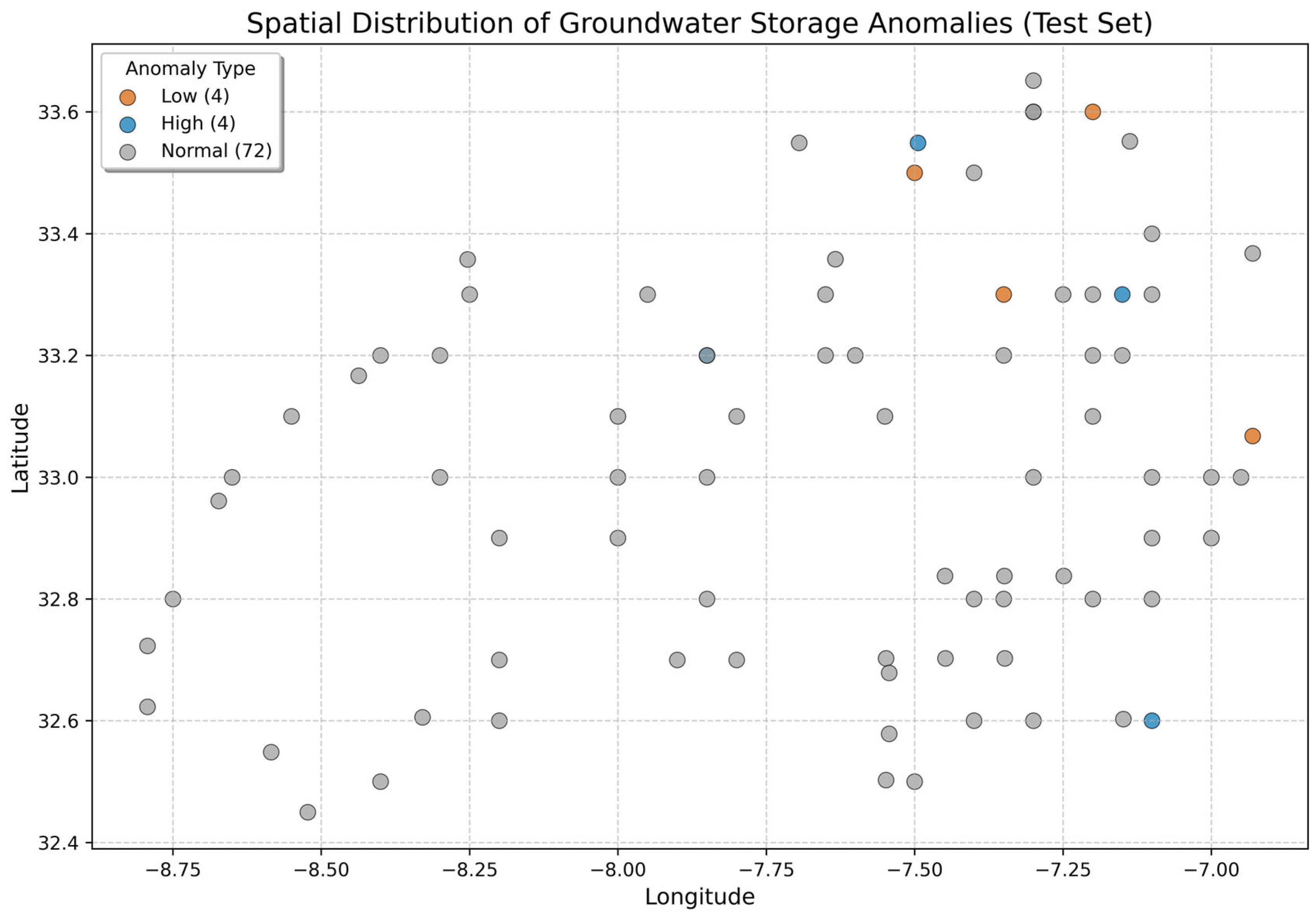

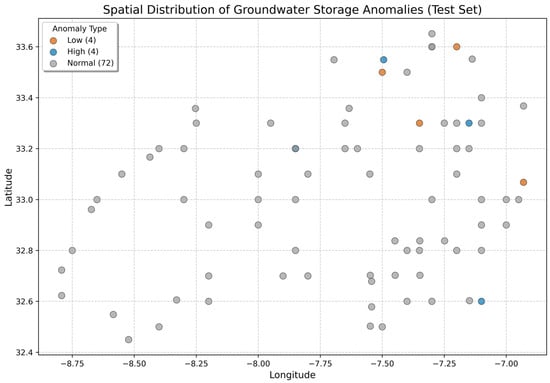

The visual clustering of these zones supports the identification of geographically coherent patterns, aiding hydrological agencies in allocating monitoring resources efficiently. Additionally, Anomaly Detection and Extreme Zone Identification: To highlight critical groundwater conditions, the predicted TWSA values were categorized and plotted in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Classified TWSAs: orange (deficit), blue (surplus), and gray (normal).

- Red zones: The lowest 5% of predicted values, representing areas at significant risk of groundwater depletion.

- Blue zones: The highest 5%, suggesting recharge-rich regions or underutilized aquifers.

- Gray zones: Represent normal storage behavior, serving as a baseline for temporal comparisons.

This classification aids anomaly tracking and early warning systems for water scarcity, helping stakeholders initiate localized action plans or awareness campaigns [13].

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of Findings

The hybrid model proposed in this study significantly outperforms traditional baseline regression models in predicting TWSA for the Casablanca–Settat region [57]. The achieved R2 of 0.97, with an RMSE of 0.13 and an MAE of 0.108, marks a substantial improvement over earlier models like linear regression (R2 = 0.924) and decision tree regression (R2 = 0.813). This highlights the model’s superior ability to capture both linear and non-linear hydro-climatic dependencies. Compared to earlier studies referenced in the literature review, our model demonstrates marked advantages in several dimensions. Table 3 below compares the key performance outcomes of our model with the most relevant previous approaches, strictly derived from the cited works.

Table 3.

Comparative performance of existing studies and the proposed hybrid model.

Previous studies have leveraged deep learning or spatio-temporal models (Table 3), they generally focus on specific patterns (either temporal or spatial) without extensive ensemble integration. Our approach focuses the benefits of diverse model types, leading to significantly higher prediction accuracy and robust generalizability.

5.2. Regional Relevance: Casablanca–Settat Groundwater Concerns

The Casablanca–Settat region, home to over 7 million residents and accounting for a significant portion of Morocco’s economic activity, faces acute groundwater stress due to its semi-arid climate and rapidly urbanizing footprint. The region exhibits pronounced seasonality, where rainfall is irregular and often confined to a few months, while the dry periods are prolonged. This climatic setup causes erratic recharge patterns, often failing to replenish deep aquifers fully [34,56,58]. Moreover, the region’s agricultural belt—especially in Settat and El Jadida—relies heavily on groundwater for irrigation. Coupled with expanding industrial zones and population clusters around Casablanca, the stress on aquifers is mounting. Over-extraction in shallow aquifers, absence of controlled recharge programs, and LULC changes further exacerbate depletion. The hybrid modeling framework presented in this study offers several region-specific benefits as follows:

- Localized Anomaly Detection: By detecting micro-level TWSAs, the model supports future zoning of groundwater stress at district and sub-district levels.

- Temporal Sensitivity: Integration of LSTM allows the model to capture seasonal recharge–discharge cycles critical in Morocco’s agro-ecological planning.

- LULC Driven Forecasting: The model incorporates land cover data to detect how different uses (urban, forest, cropland) impact local groundwater storage.

- Data-Informed Policy: High-resolution forecasts generated from the model can guide dynamic water allocation, irrigation scheduling, and artificial recharge decisions.

Although a formal feature attribution analysis was not conducted, the predictive behavior of the ensemble is primarily driven by hydroclimatic and land–surface variables that are physically linked to terrestrial water storage dynamics. Precipitation and evapotranspiration directly control water inputs and losses, while soil moisture and vegetation indices reflect surface and root-zone water availability. LULC and elevation provide spatial context related to groundwater abstraction intensity and recharge potential. The consistency of the downscaled patterns with known hydrogeological conditions suggests that the ensemble leverages physically meaningful relationships rather than purely statistical correlations.

This work fills a critical technological gap by equipping local water governance bodies with a fine-grained, interpretable, and spatially aware groundwater forecasting tool—a much-needed step in promoting water security across the Casablanca–Settat region.

5.3. Limitations and Future Scope

Although the proposed hybrid model has shown an acceptable level of predictive accuracy, there are some limitations that need to be noted to give an idea of how it should be enhanced. The dependence on GRACE (and the related GRACE-FO satellites) is one of the main limitations of the work. This interferes with the sensitivity of the model to localized movements of groundwater, particularly in heterogeneous terrains like the subregion in the bush or topography-differing regions. Moreover, ensemble architecture, where several ML and deep learning algorithms are combined, presents a certain level of complexity of computations that might limit its usage in real-time monitoring or operations based in environments with scarce digital infrastructure [59,60].

The fact that the model demonstrates some form of dependence on past trends poses yet another challenge. It can be effective, during normal seasonal and climatic conditions, but can have less adaptability in case of extreme events, like abrupt LULC changes, non-controlled groundwater pumping, or prolonged drought periods. There is also a lack of dense, field-level validated data, especially in less-monitored districts of the Casablanca–Settat region, which also constrains the capacity to make a granular accuracy evaluation at the zone level [39,61,62].

This framework can be further enhanced by combining near-real-time data streams of the Internet-of-Things (IoT)–based groundwater monitoring systems. This would improve the time responsiveness of the model so that there will be timely interventions. Also, to render the insights of this model more accessible to the practitioners, including the water boards and agricultural planners, an interactive and multilingual decision-support interface, specifically for the local administrative units, would need to be developed. It would also be beneficial to explore transfer learning methods so that the adaptation of this framework to other regions of Morocco and basins in North Africa can be achieved. In addition, integrating the model with climate modeling tools can enhance long-term scenario planning, whereby authorities can model the resilience of groundwater under different climate change scenarios [43,63].

While the downscaled outputs are provided at a 10 km spatial grid, corresponding to approximately 200 spatial grid cells across the study region, independent validation of the spatial fidelity of these patterns using dense in situ groundwater observations or high-resolution hydrological models was not feasible due to data limitations in the study region. Consequently, model evaluation focuses on temporal consistency with GRACE-derived TWSA signals using standard performance metrics. The resulting spatial patterns should therefore be interpreted as physically informed, relative variations constrained by auxiliary predictors, rather than exact point-scale groundwater measurements.

5.4. Applications of the Work

The hybrid model proposed has a substantial operational worth in regulating groundwater in the Casablanca–Settat region, wherein there are increasing demands on the resources as a result of intense agricultural production scenarios, fast urbanization processes, and climate change. With Settat and Berrechid provinces in particular and high water demand to cultivate crops, there lies the requirement in the Casablanca urban area, where the water footprint is also continuing to spread and strain the local aquifers [64].

Regional decisions can be made by the spatial predictions of TWSA that are highlighted by the model. For instance, consistently positive TWSA zones may be earmarked for recharge zone protection, while areas exhibiting persistent negative anomalies—such as ‘Sidi Bennour’ or ‘El Jadida’—could be prioritized for artificial recharge programs or stricter extraction regulations. In agricultural planning, the model offers a data-driven foundation for optimizing irrigation schedules, particularly during moisture-deficit periods, enabling agencies like the “Office Régional de Mise en Valeur Agricole (ORMVA), Agence de basin hydraulique (ABH)” to balance water availability with crop productivity.

To manage the urban areas, the predictive information can assist authorities to better measure extraction stresses and think about groundwater licensing, well-boring zoning, or groundwater recharge parks within the peri-urban areas where infiltration has lessened due to the development of impervious surfaces. Furthermore, by aligning the model’s outputs with national programs like the Plan Maroc Vert, the framework can contribute to broader sustainable water governance strategies in Morocco’s most economically significant region [65,66].

6. Conclusions

This paper establishes a hybrid ML model to anticipate TWSA over the Casablanca–Settat area, where multi-source data was used to combine satellite-observed gravity anomalies, climatic variables, and LULC data. The architecture of the models used was an ensemble of six different algorithms: HR, ARD, KR, LSTM, KNN, and GB, along with an ensemble model consisting of RF as the meta-learner. The best predictive performance was revealed in evaluation results, where the ensemble model delivered an RMSE of 0.13, an MAE of 0.108, and an R2 score of 0.97, which was way out of the baseline models.

In addition to its precision, which is in the numerical domain, the model provided useful spatial information on how the groundwater behaved in different regions and the uncovered relationships between water storage behavior and the types of land cover. Such functionalities render the framework as a feasible decision-aiding framework for water resource planning and drought monitoring, priority assignments to aquifer recharge, and adaptive irrigation management. The fact that it is modular and interpretable also means that it is scalable to other regions of comparable data availability. Integrating the empirical results of the expectations about groundwater through data and human needs of water management (in practical). This research works to bring about the contemporary theme of sustainable groundwater management in the semi-arid areas.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L., N.E.A. and O.O.; methodology, Y.L., N.E.A. and O.O.; software, Y.L.; validation, N.E.A., T.T.N. and A.M.S.; formal analysis, Y.L.; investigation, O.O.; resources, O.O. and N.E.A.; data curation, Y.L. and O.O.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L. and O.O.; writing—review and editing, Y.L., O.O., N.E.A. and A.M.S.; visualization, Y.L., N.E.A. and T.T.N.; supervision, N.E.A., T.T.N. and A.M.S.; project administration, Y.L. and N.E.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study, with all analysis code (Jupyter notebook), are archived on Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18017503. The record is currently restricted to avoid premature public release during peer review, but access can be granted to editors and reviewers on request, and it will be made fully public upon article acceptance.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the Moroccan Institute of Scientific and Technical Information (Institut Marocain de l’Information Scientifique et Technique, IMIST-CNRST) for providing access to international scientific databases such as Scopus and Web of Science through the e-resources platform, which was essential for conducting the bibliometric analysis and literature review of the present study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mukherjee, A.; Scanlon, B.R.; Aureli, A.; Langan, S.; Guo, H.; McKenzie, A. Chapter 1—Global Groundwater: From Scarcity to Security through Sustainability and Solutions. In Global Groundwater; Mukherjee, A., Scanlon, B.R., Aureli, A., Langan, S., Guo, H., McKenzie, A.A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 3–20. ISBN 978-0-12-818172-0. [Google Scholar]

- Velis, M.; Conti, K.I.; Biermann, F. Groundwater and Human Development: Synergies and Trade-Offs within the Context of the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scanlon, B.R.; Fakhreddine, S.; Rateb, A.; De Graaf, I.; Famiglietti, J.; Gleeson, T.; Grafton, R.Q.; Jobbagy, E.; Kebede, S.; Kolusu, S.R.; et al. Global Water Resources and the Role of Groundwater in a Resilient Water Future. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Ran, J.; Khorrami, B.; Wu, H.; Tariq, A.; Jehanzaib, M.; Khan, M.M.; Faisal, M. Downscaled GRACE/GRACE-FO Observations for Spatial and Temporal Monitoring of Groundwater Storage Variations at the Local Scale Using Machine Learning. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 25, 101100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilengwe, C.; Banda, K.; Nyambe, I. Machine Learning Downscaling of GRACE/GRACE-FO Data to Capture Spatial-Temporal Drought Effects on Groundwater Storage at a Local Scale under Data-Scarcity. Environ. Syst. Res. 2024, 13, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamou-Ali, Y.; Karmouda, N.; Mohsine, I.; Bouramtane, T.; Kacimi, I.; Tweed, S.; Tahiri, M.; Kassou, N.; El Bilali, A.; Chafki, O.; et al. Downscaling GRACE Total Water Storage Data Using Random Forest: A Three-Round Validation Approach under Drought Conditions. Front. Water 2025, 7, 1545821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorrami, B.; Ali, S.; Gündüz, O. Investigating the Local-Scale Fluctuations of Groundwater Storage by Using Downscaled GRACE/GRACE-FO JPL Mascon Product Based on Machine Learning (ML) Algorithm. Water Resour. Manag. 2023, 37, 3439–3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satizábal-Alarcón, D.A.; Suhogusoff, A.; Ferrari, L.C. Characterization of Groundwater Storage Changes in the Amazon River Basin Based on Downscaling of GRACE/GRACE-FO Data with Machine Learning Models. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 168958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, C.; Zhang, W. Reconstructing Long-Term, High-Resolution Groundwater Storage Changes in the Songhua River Basin Using Supplemented GRACE and GRACE-FO Data. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moudgil, P.S.; Rao, G.S.; Heki, K. Bridging the Temporal Gaps in GRACE/GRACE–FO Terrestrial Water Storage Anomalies over the Major Indian River Basins Using Deep Learning. Nat. Resour. Res. 2024, 33, 571–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavimehr, S.M.; Kavianpour, M.R. A Non-Stationary Downscaling and Gap-Filling Approach for GRACE/GRACE-FO Data under Climatic and Anthropogenic Influences. Appl. Water Sci. 2025, 15, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Bao, L.; Yao, G.; Wang, F.; Guo, Q.; Zhu, J.; Zhu, J.; Wang, Z.; Bi, J.; Zhu, C.; et al. The Analysis on Groundwater Storage Variations from GRACE/GRACE-FO in Recent 20 Years Driven by Influencing Factors and Prediction in Shandong Province, China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, J.Y.; Lee, S.-I. Predicting Changes in Spatiotemporal Groundwater Storage Through the Integration of Multi-Satellite Data and Deep Learning Models. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 157571–157583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moudgil, P.S.; Rao, G.S. Groundwater Levels Estimation from GRACE/GRACE-FO and Hydro-Meteorological Data Using Deep Learning in Ganga River Basin, India. Environ. Earth Sci. 2023, 82, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, A.; Ali, S.; Basit, I.; Jamil, A.; Farmonov, N.; Khorrami, B.; Khan, M.M.; Sadri, S.; Baloch, M.Y.J.; Islam, F.; et al. Terrestrial and Groundwater Storage Characteristics and Their Quantification in the Chitral (Pakistan) and Kabul (Afghanistan) River Basins Using GRACE/GRACE-FO Satellite Data. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 23, 100990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, V.; Ali, S.; Sohrabi, N. Estimating the Spatio-Temporal Assessment of GRACE/GRACE-FO Derived Groundwater Storage Depletion and Validation with in-Situ Water Quality Data (Yazd Province, Central Iran). J. Hydrol. 2023, 620, 129416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.S.U.; Saif, M.M.; Ahmad, N.; Rai, A.K.; Khan, M.A.; Aldrees, A.; Khan, W.A.; Mohammed, M.K.A.; Yaseen, Z.M. Spatiotemporal Analysis of Future Trends in Terrestrial Water Storage Anomalies at Different Climatic Zones of India Using GRACE/GRACE-FO. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikraftar, Z.; Parizi, E.; Saber, M.; Hosseini, S.M.; Ataie-Ashtiani, B.; Simmons, C.T. Groundwater Sustainability Assessment in the Middle East Using GRACE/GRACE-FO Data. Hydrogeol. J. 2024, 32, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, W.; Zhang, P.; Chen, P.; Li, J.; Gao, Y. Spatiotemporal Variations and Sustainability Characteristics of Groundwater Storage in North China from 2002 to 2022 Revealed by GRACE/GRACE Follow-On and Multiple Hydrologic Data. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadavi, D.; Mousavi, S.M.; Rahimzadegan, M. An Intercomparison of the Groundwater Level Estimations by GRACE and GRACE-FO Satellites and Groundwater Modeling in Iran. Acta Geophys. 2024, 72, 3609–3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Lu, C.; Hu, J.; Liu, B.; Shu, L.; Zhang, Y. Machine Learning-Based Downscaling of GRACE Data to Enhance Assessment of Spatiotemporal Evolution of Coastal Plain Groundwater Storage. Water Resour. Manag. 2025, 39, 6377–6397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorrami, B.; Ali, S.; Gündüz, O. An Appraisal of the Local-scale Spatio-temporal Variations of Drought Based on the Integrated GRACE/GRACE-FO Observations and Fine-resolution FLDAS Model. Hydrol. Process. 2023, 37, e15034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdi, M.; El Alem, A.; Goita, K. Groundwater Storage Estimation in the Saskatchewan River Basin Using GRACE/GRACE-FO Gravimetric Data and Machine Learning. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, V. Comparison Features Importance for Temporal and Spatial-Temporal Approaches in GRACE and GRACE-FO Signal Reconstruction Based on GLDAS Data. Int. J. Hydrol. Sci. Technol. 2023, 16, 370–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Assaoui, N.; Bouiss, C.; Sadok, A. Assessment of Water Erosion by Integrating RUSLE Model, GIS and Remote Sensing—Case of Tamdrost Watershed (Morocco). Ecol. Eng. Environ. Technol. 2023, 24, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Assaoui, N.; Sadok, A.; Bendaraa, A.; Charafi, M.M. Two-Dimensional Numerical Modeling of Morphodynamic Evolution in Bouregreg Estuary (Morocco). Ecol. Eng. Environ. Technol. 2023, 24, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karmouda, N.; El Assaoui, N.; Kacimi, I.; Mahe, G.; Bouramtane, T.; Brirhet, H.; Idrissi, A.; Kassou, N. Hydrological Modelling of Extreme Events in Ouergha Mediterranean Basin, Northern Morocco, Using a Deterministic Model and Gridded Precipitations. IGJ 2023, 56, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laalaoui, Y.; Elassaoui, N.; Ouahine, O. Balancing Urban Growth and the Sustainability of Groundwater and Agricultural Land: Case of the Berrechid-Settat Area. In Proceedings of the E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2024; Volume 489, p. 04012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lrhoul, H.; Assaoui, N.E.; Turki, H. Mapping of Water Research in Morocco: A Scientometric Analysis. In Proceedings of the Materials Today: Proceedings; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 45, pp. 7321–7328. [Google Scholar]

- Belgiu, M.; Drăguţ, L. Random Forest in Remote Sensing: A Review of Applications and Future Directions. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2016, 114, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achahboun, C.; Chikhaoui, M.; Naimi, M.; Bellafkih, M. Crops Classification Using Machine Learning and Google Earth Engine. In Proceedings of the SITA 2023: 2023 14th International Conference on Intelligent Systems: Theories and Applications, Casablanca, Morocco, 22–23 November 2023; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Abuzied, S.M.; Pradhan, B. Hydro-Geomorphic Assessment of Erosion Intensity and Sediment Yield Initiated Debris-Flow Hazards at Wadi Dahab Watershed, Egypt. Georisk Assess. Manag. Risk Eng. Syst. Geohazards 2021, 15, 221–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmotawakkil, A.; Moumane, A.; Zahi, A.; Sadiki, A.; Karkouri, J.A.; Batchi, M.; Bhagat, S.K.; Enneya, N. HydroPredictor a Hybrid Machine Learning Model for Addressing Data Scarcity in Groundwater Prediction. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 44069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Driss, M.A.; Iflillis, A.; Ettazarini, S.; Hahou, Y.; Boudad, L.; El Amrani, M.; Courba, S. Groundwater Potential Mapping in Fractured Aquifers Using Remote Sensing and GIS Technology in the Moulouya Region, Morocco. Iraqi Geol. J. 2024, 57, 172–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snousy, M.G.; Elshafie, H.M.; Abouelmagd, A.R.; Hassan, N.E.; Abd-Elmaboud, M.E.; Mohammadi, A.A.; Elewa, A.M.T.; EL-Sayed, E.; Saqr, A.M. Enhancing the Prediction of Groundwater Quality Index in Semi-Arid Regions Using a Novel ANN-Based Hybrid Arctic Puffin-Hippopotamus Optimization Model. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 59, 102424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodell, M.; Reager, J.T. Water Cycle Science Enabled by the GRACE and GRACE-FO Satellite Missions. Nat. Water 2023, 1, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Ran, J.; Xiao, Y.; Xu, Z.; Wu, H.; Deng, X.; Du, L.; Zhong, M. The Temporal Improvement of Earth’s Mass Transport Estimated by Coupling GRACE-FO With a Chinese Polar Gravity Satellite Mission. JGR Solid Earth 2023, 128, e2023JB027157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forkuor, G.; Hounkpatin, O.K.L.; Welp, G.; Thiel, M. High Resolution Mapping of Soil Properties Using Remote Sensing Variables in South-Western Burkina Faso: A Comparison of Machine Learning and Multiple Linear Regression Models. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhungeni, O.; Ramjatan, A.; Gebreslasie, M. Evaluating Machine-Learning Algorithms for Mapping LULC of the uMngeni Catchment Area, KwaZulu-Natal. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, J.; Alqadhi, S.; Talukdar, S.; Hang, H.T. Evaluating groundwater sustainability and vegetation dynamics in arid regions: Advanced remote sensing and spatiotemporal analysis in Saudi Arabia. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 38, 104203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, A.; Bahi, H.; Bounoua, L.; Tahiri, M.; Tweed, S.; LeBlanc, M.; Bouramtane, T.; Malah, A.; Kacimi, I. Predictive Modelling on Spatial–Temporal Land Use and Land Cover Changes at the Casablanca-Settat Region in Morocco. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2024, 10, 6691–6714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guellaf, A.; Kettani, K. Assessment of Seasonal Variations in Water Quality and Pollution Sources in the Coastal Water Bodies between Casablanca and Rabat (Northwest Morocco). Ecol. Eng. Environ. Technol. 2025, 26, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amazirh, A.; Ouassanouan, Y.; Bouimouass, H.; Baba, M.W.; Bouras, E.H.; Rafik, A.; Benkirane, M.; Hajhouji, Y.; Ablila, Y.; Chehbouni, A. Remote Sensing-Based Multiscale Analysis of Total and Groundwater Storage Dynamics over Semi-Arid North African Basins. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, F.; Martek, I.; Wu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Chen, C.; Chan, A.P.C. Scientometric Review of Smart Water Management Literature from the Sustainable Development Goal Perspective. Int. J. Strateg. Prop. Manag. 2023, 27, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Guo, Z.; Chen, K.; Fan, L.; Zhan, Y.; Kuang, X.; Cui, B.; Zheng, C. The Effect of Seasonally Frozen Ground on Rainfall Infiltration and Groundwater Discharge in Qinghai Lake Basin, China. Front. Water 2024, 6, 1495763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Assaoui, N.; Sadok, A.; Merimi, I. Impacts of Climate Change on Moroccan’s Groundwater Resources: State of Art and Development Prospects. In Proceedings of the Materials Today: Proceedings; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 45, pp. 7690–7696. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.; Wiegand, B.; Reza, A.; Chaudhuri, H.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Yadav, A.; Patra, P.K. A machine learning approach to investigate the impact of land use land cover (LULC) changes on groundwater quality, health risks and ecological risks through GIS and response surface methodology (RSM). J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 366, 121911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaoui, N.E.; Sadok, A.; Charafi, M. Analysis of a Water Supply Intake from a Silted Dam Using Two-Dimensional Horizontal Numerical Modeling: Case of Mechraa Hammadi Dam (Morocco). Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 45, 7718–7724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqr, A.M.; Kartal, V.; Karakoyun, E.; Abd-Elmaboud, M.E. Improving the Accuracy of Groundwater Level Forecasting by Coupling Ensemble Machine Learning Model and Coronavirus Herd Immunity Optimizer. Water Resour. Manag. 2025, 39, 5415–5442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fentaw, A.E.; Abegaz, A. Analyzing Land Use/Land Cover Changes Using Google Earth Engine and Random Forest Algorithm and Their Implications to the Management of Land Degradation in the Upper Tekeze Basin, Ethiopia. Sci. World J. 2024, 2024, 3937558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dharumarajan, S.; Hegde, R. Digital Mapping of Soil Texture Classes Using Random Forest Classification Algorithm. Soil Use Manag. 2022, 38, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Weng, Q.; Li, G. Evaluation of Training Sample Sizes and Class Distribution on Machine Learning Classifiers for Land Cover Classification Using Google Earth Engine. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 100, 102327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, A.; Jamshidi, M.; Roozbahani, A.; Golparvar, B. Groundwater Level Forecasting Using Empirical Mode Decomposition and Wavelet-Based Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Neural Networks. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 28, 101397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzegar, M.; Gharehdash, S.; Chowdhury, F.; Liu, M.; Timms, W. Hybrid Machine Learning for Predicting Groundwater Level: A Comparison of Boosting Algorithms with Neural Networks. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 31, 101508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomani, K.; Pshdari, S. Evaluation of Different Classification Algorithms for Land Use Land Cover Mapping. KJAR 2024, 9, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzekraoui, H.; El Asri, Z.; Ouikhalfan, M.; Benyaich, A. Urban Sprawl and Land Degradation in the Casablanca-Settat Region of Morocco: Analysis and Implications. Urban Plan. Dev. 2020, 146, 05020011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadouane, A.; Chaouki, A. Simulation of the Flood of El Maleh River by GIS in the City of Mohammedia-Morocco. In Proceedings of the Climate Change and Water Security: Select Proceedings of VCDRR 2021; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- El Haou, M.; Ourribane, M.; Ismaili, M.; Abdelrahman, K.; Fnais, M.S.; Krimissa, S.; El Oudi, H.; Hajji, S.; El Bouzkraoui, M.; Tarchi, F.; et al. Advanced GIS-Based Modeling for Flood Hazards Mapping in Urban Semi-Arid Regions: Insights from Beni Mellal, Morocco. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1585926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feizizadeh, B.; Omarzadeh, D.; Kazemi Garajeh, M.; Lakes, T.; Blaschke, T. Machine Learning Data-Driven Approaches for Land Use/Cover Mapping and Trend Analysis Using Google Earth Engine. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2023, 66, 665–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukdar, S.; Singha, P.; Mahato, S.; Shahfahad; Pal, S.; Liou, Y.-A.; Rahman, A. Land-Use Land-Cover Classification by Machine Learning Classifiers for Satellite Observations—A Review. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryawanshi, A.; Sharnagat, N. Google Earth Engine-Application in LULC Classification; ICAR Research Complex for NEH Region: Meghalaya, India, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riche, A.; Ricci, R.; Melgani, F.; Drias, A.; Souissi, B. Machine Learning Approach to LULC Forecasting. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Mediterranean and Middle-East Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (M2GARSS), Oran, Algeria, 15–17 April 2024; IEEE: Oran, Algeria, 2024; pp. 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Landini, F.; Malerba, F.; Mavilia, R. The Structure and Dynamics of Networks of Scientific Collaborations in Northern Africa. Scientometrics 2015, 105, 1787–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouabid, H.; Martin, B.R. Evaluation of Moroccan Research Using a Bibliometric-Based Approach: Investigation of the Validity of the h-Index. Scientometrics 2009, 78, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Liu, L.; Zhang, X.; Yang, J.; Chen, X.; Gao, Y. Automatic Land-Cover Mapping Using Landsat Time-Series Data Based on Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharnagat, N.; Nema, A.K.; Mishra, P.K.; Patidar, N.; Kumar, R.; Suryawanshi, A.; Radha, L. State-of-the-Art Status of Google Earth Engine (GEE) Application in Land and Water Resource Management: A Scientometric Analysis. J. Geovis. Spat. Anal. 2025, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.