Abstract

Water reservoirs are critical components of hydrological systems that mitigate floods and droughts, but their long-term performance under climate change and variable socioeconomic conditions remain insufficiently documented. This study examines the Bahlui River basin (northeastern Romania), where 17 reservoirs constructed mainly between the 1960s and 1980s have been operational for more than five decades. Using the most recent technical reservoir reports, land-use evolution, and present operational functions, the contribution of man-made reservoirs to flood attenuation and drought buffering over time was appraised. Flood mitigation is the most consistent and reliable function, with peak-flow reductions commonly exceeding 60–90% of design discharges at the basin scale. Engineered drought mitigation functions (irrigation and industrial water supply) have decreased significantly as a result of socioeconomic changes started in 1989. However, the gradual expansion of green infrastructure, such as wetlands and riparian vegetation, has improved passive water retention and low-flow buffering capacity. These unanticipated developments have resulted in variable levels of hybrid hydrological resilience. The findings show that, while artificial reservoirs have strong flood-control capacity over long periods of time, their contribution to drought mitigation is increasingly dependent on the integration of ecological components, emphasizing the importance of green-gray interactions in long-term reservoir management.

1. Introduction

Hydrological extremes, such as droughts and floods, have become more frequent and intense over the past 50 years, most likely due to climate change [1,2]. This has become a major issue for sustainable water management on a global scale [3,4,5]. Therefore, the concept of hydrological resilience (HR) [6,7] and achieving it, whether naturally or by engineering [8,9], is becoming increasingly important as mankind enters a new geological period, the Anthropocene [10,11]. Unfortunately, systems like riparian vegetation, forests, and wetlands that provide natural resilience [8] against hydrological extremes clash with the trend for agricultural and urban expansion brought on by the world’s population growth [9,12,13]. As a result, human intervention is increasingly required to supplement natural resilience and/or compensate for its absence. The term “engineered hydrological resilience.” [8] describes man-made infrastructure, such as dams, reservoirs, dikes, levees, floodwalls, and polders, that is intended to control water flow and minimize hydrological vulnerabilities. At the local scale, the impact of dams, reservoirs, and related artificial structures is immediate and highly visible, affecting the watercourse and the surrounding landscape. The regional and subsequently global impact is more subtle and occurs relatively slowly as a consequence of altering the natural water cycle. For example, high open water surfaces have an impact on surface evaporation, creating heat and mass fluxes that can contribute to climate changes [14]. Therefore, human intervention in watercourses, carried out for purposes other than flood protection and/or drought prevention, is quite controversial [15], and the balance between the drawbacks and benefits of hydraulic structures is still a subject of debate [14,16]. Furthermore, as the frequency and severity of hydrological extremes tend to rise, human response needs to adapt, which means modifying dam and reservoir design and operations [11,17]. The new hydraulic structures are designed to meet present and, to some extent, future needs [18], whereas the older ones must deal with both anthropogenic interferences (e.g., aggressive urban development, intensive agriculture) and climate-related issues (e.g., flash floods, prolonged droughts) [19,20]. In this context, the transition from single to multi-purpose reservoirs, aiming to increase the benefits of the hydraulic structures, is logical [21,22].

Without a doubt, the hydraulic structures are essential tools in water management, their sustainability depending on a series of factors such as adaptive design, integrated basin-scale planning, and ecological restoration measures [23,24]. Modern strategies are increasingly relying on hybrid systems, which combine engineered hydraulic resilience with natural water retention techniques to provide balanced flood and drought mitigation [25].

A relevant example that illustrates the evolution from single to multi-purpose reservoirs and from engineered to hybrid resilience is the Bahlui River basin in northeastern Romania. This hydrographic system, characterized by (i) a history of recurrent floods and droughts, (ii) a mixed natural–urban environment, (iii) a huge socioeconomic transition (from communism to democracy), and (iv) a massive anthropogenic interference. It provides an insightful case study for assessing the effectiveness of substantial hydrotechnical interventions. Bahlui’s hydrographic basin comprises at least 17 dams and accumulations, the majority of which have been exploited for more than 50 years.

This paper presents a critical analysis of the Bahlui River hydrographic system from a civil engineering perspective, focusing on the interplay between natural hydrological dynamics and hydrotechnical infrastructures. By examining the initial goals and the actual performances of existing reservoirs and hydraulic structures, the study aims to assess the effectiveness of current mitigation strategies and identify opportunities for optimization. The time-developed interaction between anthropogenic and natural water retention systems provides multiple reservoirs in the Bahlui basin with hybrid resilience. The current study stands out for its comprehensive and interdisciplinary approach, which combines historical exploration, civil engineering analysis, hydrological evaluation, and environmental management perspectives to assess how HR contributes to the mitigation of hydrological extremes, such as intense floods and prolonged droughts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Civil Engineering Infrastructure on the Hydrographic Network of the Bahlui River

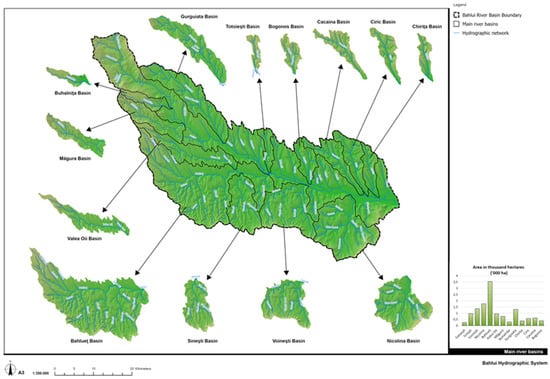

The complex hydrological and morphological characteristics of the Bahlui River basin (Figure 1) necessitate an accurate description of the study area to contextualize the engineering challenges and interventions. A detailed description of the Bahlui hydrographic system can be found in our previous papers [26,27] and/or in the works of other authors [28,29,30]. In a few words, the Bahlui River is 119 km long, has a catchment area of 2025 km2, and a hydrographical network of nearly 3100 km. Even though it is a rain-fed river with an average discharge ranging from 2.8 to 4 m3/s, huge discharge variations ranging from complete depletion during summer droughts [31] till up to 600 m3/s during floods were reported in history [26]. Based on its length and average discharge, the Bahlui River is in the small rivers category [32]; however, there are not many rivers of this size with similar levels of hydrological engineering. No less than 17 dams and accumulations were constructed during the second half of the past century in order to mitigate floods and droughts [26,30]. Only two dams—Pârcovaci and Tansa-Belcești—were constructed along the river’s main course; the other dams, some of which had temporary and some of which had permanent activity, were constructed inside its hydrographic basin (Figure 1), on the Bahlui River’s main tributaries.

Figure 1.

The Bahlui River’s hydrographic system, including main tributaries and basins.

In this study, the term ‘temporary reservoir’ refers strictly to an operational regime, following Romanian hydrotechnical practice; it denotes structures designed for immediate water storage that typically fill during high-flow events and remain dry or partially dry during normal or low-flow conditions. This label does not suggest diminished resilience or ecological insignificance.

Succinct descriptions for each of the 17 dams/accumulations are presented in the next paragraphs, highlighting their original (initially designed) and current functions. The subsequent presentation is based on up-to-date official reports, written in the Romanian language, see references [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49].

Some specific abbreviations were used in the ensuing paragraphs: NRL = normal retention level; m. d. M. N. = meters above Black Sea level; Q0.1%, Q0.01%, Q1.2×0.01% … = floods with exceedance probabilities 0.1%, 0.01%, … and verification; V = volume, m3; Q = volumetric flowrate (discharge), m3/s; ha = hectares, 1 ha = 10,000 m2.

2.1.1. Dams on the Bahlui River: Pârcovaci and Tansa–Belcesti

The Pârcovaci Reservoir, built between 1978 and 1984, is a Category B, Class II facility with hydrographic code XIII-1.15.32. It was originally intended for industrial and civil water supply, flood mitigation, and natural fish farming. Today, it continues to supply water for Hârlău, primarily for civil use, while still fulfilling flood-control and fish-farming functions. A small amount of technical data is reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

The Pârcovaci Dam: technical data [40].

The Tansa–Belcești Reservoir on the Bahlui River, built between 1971 and 1974, is classified as an important Class I, Category B hydraulic structure and is identified by hydrographic code XIII–1.15.32. The technical data for Tansa–Belecesti reservoir are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

The Tansa–Belcești Reservoir: technical data [43].

Designed primarily for irrigation, the reservoir also provided flood attenuation, local water supply, and supported fish-farming activities, with no hydropower component planned. In its current operation, its main function is flood mitigation. Irrigation is now significantly reduced due to degradation of the distribution system, while water supply continues at a modest rate (2020: 0.01548 m3/s). The reservoir also maintains fish-farming uses and meets ecological flow requirements established by basin management authorities.

2.1.2. Podu Iloaiei Reservoir: Accumulation on Bahlueț River

The Podu Iloaiei Reservoir was built between 1963 and 1964 on the Bahluieț River, which is Bahlui’s main tributary. Its hydrographic code is XIII–1.015.32.12.00.0; it was upgraded from importance Class II to I in 1975 and falls under Category B. Some rehabilitation works were performed in 2011. In its original design, the reservoir served multiple functions, including irrigation and water supply, flood protection, and fish-farming activities. The reservoir was not designed to supply drinking water, industrial water, or to produce hydropower. Under current operating conditions, the primary function of the Podu Iloaiei Reservoir remains flood mitigation. Irrigation activities have been discontinued since 2008, while fish-farming operations continue and prosper. The technical data for Podu Iloaiei Reservoir are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

The Podu Iloaiei Reservoir: technical data [45].

2.1.3. Reservoirs on Râul Locii River: Bârca and Ciurbești

The Bârca Temporary Reservoir is located on the Râul Locii, within the Nicolina River basin, and is identified by hydrographic code XIII.1.15.32.20.1. Classified as a Class II reservoir and falling under Category D, it was constructed between 1978 and 1981. In its original design, the reservoir served exclusively flood-related functions, including flood mitigation for Ciurbești, reduction in downstream flood peaks, and sediment retention to protect the Ciurbești Reservoir. It was not intended for water supply, irrigation, fish farming, or hydropower. Currently, its operational role remains unchanged: it continues to provide flood attenuation and peak-flow reduction on the Nicolina and Bahlui Rivers, with no water-supply, irrigation, or ecological-flow functions.

The Ciurbești Reservoir, also located on the Râul Locii (hydrographic code XIII.1.15.32.20.1.0), was originally classified as Class II but was upgraded to Class I in 1976. It is a Category C reservoir built in 1962. The reservoir was initially designed to support irrigation and water supply for 250 hectares (100,000 m3/year), to function as a permanent fish-farming reservoir, and to provide flood attenuation for downstream localities including Ciurbești, Ciurea, and the Nicolina and Bahlui sectors. In the current operation, flood mitigation remains its primary function. Fish farming continues under natural hydrological conditions, and the reservoir additionally supports a nearby sports and recreation area. Some technical data for Bârca and Ciurbești Accumulations are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Reservoirs on the Râul Locii River: Bârca and Ciurbești—technical data [34,49].

2.1.4. Accumulations on Ciric River: Aroneanu and Ciric III Reservoirs [38,46]

The Aroneanu Reservoir, located on the Ciric River (hydrographic code XIII.1.15.32.22), is classified as a Class I reservoir and belongs to Category B. It was constructed between 1962 and 1964, with crest rehabilitation works completed in 1977–1978. In its original design, the reservoir served several functions: maintaining a permanent 70-hectare lake for fish farming, providing flood attenuation, supplying water to the Ciric I and Ciric II lakes, and supporting irrigation. In the current operation, flood mitigation remains its primary role. Fish-farming activities have ceased due to the absence of active contracts, irrigation has been discontinued, and the reservoir now supports rowing and other sports activities. Table 5 provides some technical data for these reservoirs.

Table 5.

Accumulations on the Ciric River: Aroneanu and Ciric III—technical data [38,46].

Ciric III Reservoir is also situated on the Ciric River and is identified by hydrographic code XIII.1.15.32.22. A Class I, Category C reservoir, it was constructed between 1976 and 1978. It was originally intended for natural-regime fish farming and flood attenuation. Today, flood mitigation continues to be the principal function. Fish-farming activities are still practiced under natural hydrological conditions, and the reservoir has become part of a broader recreation and leisure area.

2.1.5. Accumulations on Cacaina River: Cârlig and Vânători

The Cârlig (hydrographic code: XIII.1.15.32.21) and Vânători (hydrographic code: XIII.1.15.32.21) reservoirs are located on the Cacaina River and were constructed between 1978 and 1981 and 1979–1982, respectively. Both reservoirs are classified as Category D structures, with Cârlig designated as Importance Class I and Vânători as Importance Class II. Originally, each reservoir was designed solely for flood attenuation, with no provisions for water supply, irrigation, fish farming, or hydropower production. Their operational purpose has remained unchanged, and today they continue to function exclusively as flood-mitigation structures. Some technical data are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Accumulations on the Cacaina River: Cârlig and Vânători Reservoirs—technical data [35,39].

2.1.6. Plopi Accumulation on Gurguiata River

The Plopi reservoir, basin code: XIII.1.15.32.8, classified as Importance Class II, Category B, was built over three years, from May 1975 to October 1978. Its original design envisioned a multifunctional role. It was intended to provide 2.4 million m3 of water for the irrigation of roughly 400 hectares, to support a 114-hectare fish-farming area, and to contribute to flood protection within the basin. Over time, the reservoir’s operational profile has evolved. Flood mitigation remains a fully preserved and active function. However, irrigation services are currently inactive. Fish farming continues, but only under natural conditions rather than through managed aquaculture. The reservoir now also fulfills a water-supply role, supported by an active contract amounting to approximately 1.1906 million m3 of water per year. More technical data are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

The Plopi Reservoir: technical data [44].

2.1.7. Sârca Accumulation on Valea Oii River

The Sârca Reservoir on the Valea Oii River (Basin Code XIII.1.15.32.12.7), built in 1979–1984 and classified as Importance Class II, Category C, was originally designed for irrigation (1.0 million m3/year for ~400 ha), fish farming (28 ha), and flood attenuation, with no municipal or hydropower use. Currently, its primary function remains flood mitigation; irrigation has decreased to 128,000 m3/year, and fish-farming activity has enhanced. The reservoir can additionally retain up to 3.0 million m3 to buffer potential upstream pond failures. A few technical data are presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

The Sârca Reservoir: technical data [36].

2.1.8. Cucuteni Reservoir on Voinești River

The Cucuteni Reservoir, basin Code XIII.1.15.32.15, was built in 1964 and classified as an important Class II, Category C. It was originally designed to store 3.0 million m3 for irrigating 780 ha, to support a 108 ha natural-regime fish pond (useful volume 3.0 million m3), and to provide flood attenuation. Currently, flood mitigation remains fully functional; irrigation capacity is largely unused despite ~300 ha being potentially irrigable; and fish farming continues on 98.9 ha, with 1.73 million m3 available at NRL 58.48 m. The technical data for the Cucuteni Reservoir are presented in Table 9.

Table 9.

The Cucuteni Reservoir: technical data [47].

2.1.9. Ciurea Reservoir on Nicolina River

The Ciurea Temporary Reservoir, constructed between 1978 and 1981 on the Nicolina River, is classified as an importance Class I, Category D hydraulic structure (code XIII.1.15.32.20). Its primary purpose at the time of design was the attenuation of floods on the Nicolina River and the protection of the downstream localities of Ciurea, Miroslava, and Iași—specifically the CUG, Nicolina, and Galata districts—as well as safeguarding approximately 80 hectares of agricultural land. In its current operational configuration, the Ciurea Reservoir continues to fulfill its original flood-control function entirely. Downstream of the dam, ecological flow is ensured by allowing the natural river discharge to pass through the system, and no supplementary uses have been assigned. The reservoir now forms an integral component of the flood-protection chain within the Nicolina sub-basin, working in coordination with the upstream Ciurbești Reservoir. The technical data for Ciurea Temporary Reservoir are presented in Table 10.

Table 10.

The Ciurea Temporary Reservoir: technical data [48].

2.1.10. Cornet Reservoir on Cornet River

The Cornet Temporary Reservoir, constructed between 1978 and 1981 on the Cornet River, is classified as an Importance Class I, Category D hydraulic structure. Situated within basin code XIII.1.15.32.20.2.1, the reservoir was initially designed primarily for flood attenuation, with its principal function being to enhance the safety level of the downstream Ezăreni Reservoir, raising its protection to Importance Class I standards. In addition to this primary role, the Cornet Reservoir was expected to contribute to reducing peak flood flows propagating toward the Nicolina and Bahlui Rivers. In its current operational context, the Cornet accumulation continues to serve exclusively as a flood-mitigation structure. Its role remains essential for the overall safety of the Ezăreni Reservoir and for the coordinated flood-protection system operating along the Nicolina–Bahlui corridor, providing attenuation capacity during high-flow events. The technical data for the Cornet Temporary Reservoir are presented in Table 11.

Table 11.

The Cornet Accumulation: technical data [37].

2.1.11. Ezăreni Reservoir on Ezăreni River

The Ezăreni Reservoir, constructed between 1962 and 1964 on the Ezăreni River, is classified as an Importance Class I, Category B hydraulic structure within basin code XIII.1.15.32.20.2. In its original design, the reservoir fulfilled multiple functions. It provided approximately 0.140 million m3 of industrial water per year, served as an irrigation source for roughly 360 ha of agricultural land, supported fish-farming activities with a usable volume of 0.78 million m3 at its normal retention level (NRL = 58.40 m d. M. N.), and contributed to regional flood attenuation.

The project also incorporated a recreational component through the formation of a permanent lake of approximately 47 ha at NRL. In its present operational state, flood mitigation remains the reservoir’s primary and consistently maintained function. The former provisions for industrial water supply and irrigation are no longer in use, although the conditions for fish-farming activities remain available at the standard operating level. The recreational role associated with the permanent lake is also preserved, continuing to provide both landscape and leisure value. Some technical data for Ezăreni Reservoir are presented in Table 12.

Table 12.

The Ezăreni Reservoir: technical data [33].

2.1.12. Rediu Reservoir on Rediu River

The Rediu Reservoir, built between 1986 and 1988 on the Rediu River, is classified as an Important Class III, Category C hydraulic structure within basin code XIII.1.15.32.19. In its original design, the reservoir served multiple purposes. It provided a storage volume of approximately 0.30 million m3 intended to irrigate 120 ha of downstream agricultural land, contributed to flood attenuation, and supported natural-regime fish farming through a permanent water surface of 14.6 ha at normal retention level. In the current operation, flood mitigation remains the reservoir’s predominant function. The irrigation component has been discontinued, but fish-farming activities continue to be maintained, relying on the same permanent water surface of about 14.6 ha at NRL. The technical data for Rediu Reservoir are presented in Table 13.

Table 13.

The Rediu Reservoir: technical data [41].

2.1.13. Chirița Reservoir on the Chirița River

The Chirița Reservoir, constructed between 1962 and 1964 on the Chirița River and identified under hydrographic code XIII.1.015.32.23.00.0, is classified as an Importance Class III, importance Category C hydraulic structure. Originally designed as a pre-decantation basin for the Iași water treatment plant, the reservoir was intended to store water pumped from the Prut River and to ensure both flood attenuation and the maintenance of a minimum ecological flow along the downstream reach of the Chirița stream. In its current operational configuration, the Chirița Reservoir serves primarily as a water-supply and pre-treatment source for the municipality of Iași, supporting both industrial and potable water needs. Its flood-mitigation function continues to be maintained, and controlled releases secure downstream ecological flows, with discharge values adjusted according to hydrological conditions: 0.100 m3/s under low-flow scenarios, 0.125 m3/s under medium-flow conditions, and 0.150 m3/s during high-flow periods. The system also continues to facilitate industrial water pumping. Some technical data for Chirița Reservoir are presented in Table 14.

Table 14.

The Chirița Reservoir: technical data [42].

2.2. Historical Evolution of Land Use in the Bahlui Hydrographic System

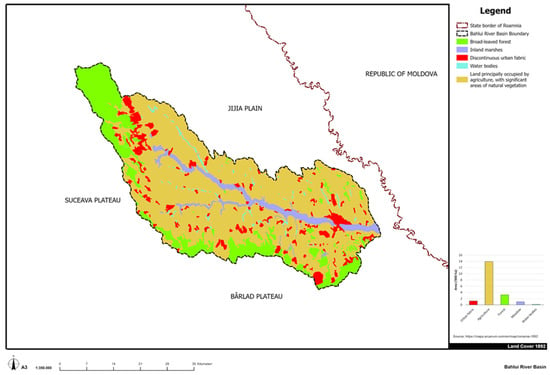

Before the completion of the hydrotechnical infrastructure, the Bahlui was acknowledged as a capricious watercourse oscillating between complete depletion and huge discharge values (up to 600 m3/s during the floods in 1932) [26]. Although its basin is highly engineered, it still remains a rain-fed, lowland river with many ungauged, intermittent tributaries; only about 30% of the network has permanent flow. Three maps were chosen as representative of the land-use evolution of the hydrographic basin as presented in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4.

Figure 2.

Bahlui River Basin: land use, 1892.

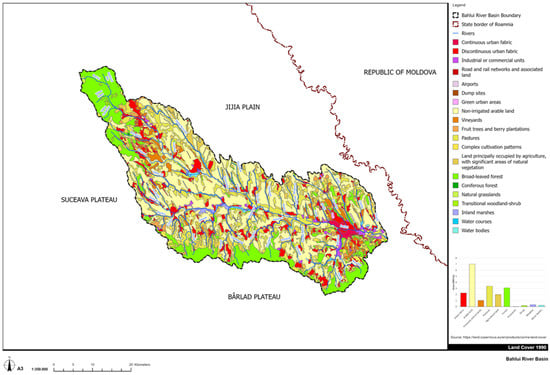

Figure 3.

Bahlui River Basin: land use, 1990.

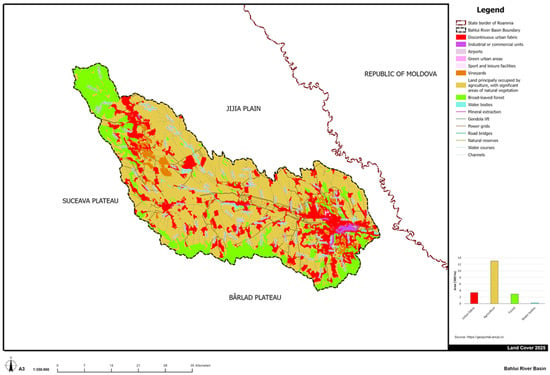

Figure 4.

Bahlui River Basin: land use, 2025.

In 1892, the main land use was agriculture (71.12% from the total basin area). The forest surfaces were surprisingly low (16.7%). A system of fish ponds and small natural lakes, connected to a fairly wide, marshy riverbed of the Bahlui River, is depicted in Figure 2. Around 100 years later, at the very beginning of the post-communist era, in 1990, the land use was completely different (Figure 3). Although agriculture remains the primary occupation (68.40%), some degree of diversity occurs: pastures, vineyards, orchards, and grasslands. The urbanization level varies significantly (11.66%), mostly due to socialist forced urbanization politics [50], while the surface occupied by forest remains relatively constant (16.99%).

Nowadays (Figure 3), there is still a tendency toward urbanization (17.46%); nevertheless, the real estate market and deindustrialization are the main factors [51]. Again, the land use is mainly agricultural (62.27%), but to some extent less diverse than in the 1990s (Figure 4). The remaining (compared to 1990 land cover) industrial areas are concentrated around Iași, the major urban area in the region.

The development of green elements within the Bahlui reservoir system has been significantly influenced by changes in land use and increasing urbanization. After 1989, riparian vegetation, wetlands, and reed beds naturally developed in reservoir tails due to changes in agricultural methods, land abandonment, and decreased maintenance activities. Most of these eco-friendly elements (green infrastructure, GI) emerged as unintended byproducts. Over time, they start to contribute to hydrological regulation, progressively enhancing passive water retention, flow attenuation, and ecological connectivity.

2.3. Land Use Maps: Graphical Updating and Processing

The land-use information available for the Bahlui River Basin is composed of the legacy of the maps: Maps of Moldavia 1892–1898, scale 1:50,000; Corine Land Cover 1996, scale 1:100,000, and Orthophotoplan 2025 (ANCPI). The used methodology correlates the data from different land-use categories, highlighting changes from one historical period to another. The utilized database was digitally analyzed and processed using GIS software, ArcPRO v.10.6.1, and represents the support for the cartographic material realized in this work. The statistical data processing was performed based on Microsoft Office 2016. For graphic processing, the following software was used: Autodesk Civil 3D 2024 v. 13.6.2090.0, Adobe Photoshop 7.0.

2.4. Limitations

The main limitation of this work is the inherent qualitative nature of the hybrid hydrological resilience (HR) concept and its assessment. Because of the long-term perspective and the absence of reliable, measurable ecological data for the entire reservoir system, HR was evaluated using qualitative indicators based on observable and repeatable circumstances rather than numerical methods. Therefore, the study does not aim to determine quantitative correlations or causal linkages between HR levels and reservoir characteristics. Instead, it describes the long-term, unplanned co-evolution of natural ecosystem elements and gray infrastructure, utilizing empirical and historical data to show how hybrid resilience develops over reservoir systems’ life cycles. The institutional recognition (protected natural area, for example) was regarded as a supporting indicator that demonstrated long-term ecological significance. However, legal protection status does not guarantee high HR status for a particular structure.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Key Highlights on Bahlui’s River Civil Engineering Infrastructure

While the structural and functional aspects of the reservoir system in the Bahlui River basin are relatively similar, certain projects differ due to particular hydrotechnical elements.

The Pârcovaci Reservoir features the tallest dam in the basin (25 m), while Țansa–Belcești accumulation is the largest impoundment, with an estimated 40 million m3 of total storage. Among permanent systems, Plopi and Sârca Reservoirs provide the largest useful volumes (3–4 million m3), supporting irrigation, aquaculture, and regional flood mitigation. The deepest active water columns, expressed through the largest elevation range between NNR and maximum levels, are found at Cucuteni and Plopi reservoirs, enhancing their capacity for both daily regulation and extreme-event attenuation. From a historical perspective, the Cucuteni reservoir, commissioned in 1964, is the oldest operational basin, while structures such as Rediu, Bârca, Plopi, and Sârca represent the newer generation developed during the 1980s. The Rediu reservoir, functional since 1988, is the smallest permanent storage, with only 0.675 million m3. The temporary reservoirs Cornet and Vânători achieve the highest flood-attenuation performance, designed to reduce incoming peaks by 60–85% and provide essential protection for downstream communities, including the urban sectors of Iași.

It is worth mentioning that none of the reservoirs were built or run for hydropower, which is in line with the Bahlui basin’s modest discharge potential and mild gradients. Another common feature is that structurally, every dam in the system is a homogeneous earthfill structure constructed from locally available clays or loess-based materials.

3.2. Half-Century Functional Evolution of the Hydrotechnical Infrastructure

The oldest reservoir from Bahlui’s hydrographic system, Cucuteni, is 61 years old, while Rediu, the most recent to be put into service, is 37. The reservoir system of the Bahlui basin is, on average, about half a century old, their construction concentrated between 1964 and 1988. As a result, the majority of structures currently function within the mid- to late-life range of a typical earthfill dam, which is predicted to last 50 years or more [52,53,54].

During the five decades following their construction, the reservoirs of the Bahlui basin have experienced several major politico-economic transitions that, in some cases, have reshaped their functionality. The most influential was the post-1990 decline of state-managed agriculture and industry [55,56], which sharply reduced irrigation demand and eliminated most industrial water needs, leaving many reservoirs underutilized relative to their original design. Fragmented land ownership and limited local budgets further constrained maintenance, accelerating sedimentation and reducing operational volumes. After Romania’s EU accession in 2007, new environmental directives such as the Water Framework Directive [57], Floods Directive [58], Natura 2000 [59], shifted policy priorities toward ecological flow maintenance, biodiversity conservation, and flood-risk reduction, redefining the reservoirs’ operational regimes. More recently, recurrent extreme-weather events associated with climate variability [60,61] have increased the emphasis on flood attenuation and drought resilience, elevating safety requirements for aging dams [62]. Together, these politico-economic shifts have progressively realigned reservoir functions away from their initial agro-industrial purposes toward a predominantly flood-protection, ecological, and urban-safety role within the Iași metropolitan region. Based on these considerations, three classes of dams can be established in Bahlui’s hydrographic basin:

- Reservoirs that essentially kept their original purpose. This category includes (i) the non-permanent reservoirs, Bârca, Cârlig, Cornet, Ciurea, and Vânători, that were built with a single function: flood attenuation; (ii) Ciric III and Ciurbești reservoirs, that preserved their main functions of flood attenuation and fish-farming, with recreation added as a new utility; and (iii) Pârcovaci Accumulation that still performs its designed functions: urban/industrial water supply for Hârlău, flood attenuation, ecological flow, and fishery; the only change is that industrial water demand has decreased.

- Reservoirs with partially modified functionalities, where the original multi-purpose concept remains visible, but certain branches, especially irrigation, have faded: (i) Tansa–Belcesti, Podu Iloaiei, and Rediu, which were planned primarily for irrigation, flood control, and fish-farming, are now centered on flood attenuation and fish-farming; (ii) Cucuteni, Sârca, Plopi, that shifted from irrigation as the main function to fish-farming, keeping their flood attenuation status; (iii) Chirița, that shifted from water storage to water supply, preserving the other functions.

- Reservoirs with major functional modifications, where the current function is clearly different from the original design: (i) Aroneanu, that started as a genuinely multipurpose reservoir (irrigation, fishery, partial water supply, and flood defense) but currently functions mainly as a flood-mitigation and recreational/sports lake; and (ii) Ezăreni, initially designed to supply industrial water and irrigation, to support fishery and flood control, that nowadays ensure flood attenuation and present potential for fishery and recreational activities.

In conclusion, the Bahlui reservoir system has developed a consistent functional trajectory over the last fifty years. Every reservoir that was first built for flood mitigation still serves this purpose today, making flood protection the most reliable and enduring function. By contrast, irrigation and industrial water supply have undergone the sharpest decline. It has completely disappeared from certain reservoirs (e.g., Podu Iloaiei, Rediu, Aroneanu, Ezăreni) and is only minimally present in others, such as Sârca, Plopi, and Cucuteni. Fish farming and leisure activities, on the other hand, have shown to be relatively resilient, frequently persisting in areas where local demand and infrastructure are still feasible. Recreational use has become the primary function in certain reservoirs, most notably Aroneanu, Ciric III, and Ciurbești, indicating a broader functional shift away from agro-industrial goals and toward environmental and social considerations. Naturally, as Minea reported in his study [29], the water quality of each accumulation also changed with time. Nevertheless, as indicated in the following, hybrid resilience is not about the structural integrity of man-made constructions or the health of natural ecosystems, but rather about the green-gray interaction and its adaptive capacity to manage floods and droughts. This study does not consider legal protection status (for example, Law No. 5/2000 or Natura 2000 classification) as proof of ecological integrity or optimal ecosystem functioning. Protected reservoirs may nevertheless suffer from ecological degradation, such as eutrophication, discontinuities in nutrient flow [26], the presence of invasive species, or hydro-morphological fragmentation [27], as observed in some areas of the Bahlui basin [29].

3.3. Hybrid Resilience: From Theoretical Concept to Actual Examples

3.3.1. HR: Theoretical Background

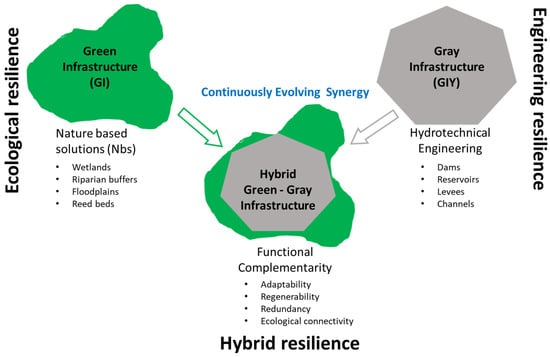

In the middle of the 1970s, C. S. Holland introduced the concept of “resilience” [63], and in the late 1990s, the same author divided it into “engineering resilience” and “ecological resilience” [64]. A series of debates followed the introduction of the resilience concept and there are two distinct interpretations of this term (simplified) [65,66,67,68,69]: (i) the capacity of a system to absorb disturbance and reorganize so as to still retain essentially the same function, structure, and identity; and (ii) the time required for a system to return to an equilibrium or steady-state following a perturbation. According to Granata and Di Nunno [8], in hydrology, the term “resilience” means that a water system can continue to perform the designed functions, such as water supply, flood regulation, and ecosystem support, despite disturbances (e.g., floods and droughts). Referring mainly to floods mitigation, Nakamura [70] introduced the terms “gray infrastructure” (GYI) that represents the engineering resilience and include dams, reservoir, levees, drainage channels, etc., and green and “green infrastructure” (GI), which represents the ecological resilience and include forests and wetlands in the watershed, wetlands, riparian corridors, floodplains, reed beds, etc.

Although resilience in hydrological systems can arise through both natural processes (GI) and engineered interventions (GYI), each one has its own benefits and drawbacks:

- (i)

- GYI—dams, levees, stormwater networks—remain essential for regulating runoff and protecting communities. Yet its effectiveness is limited under extreme future climate scenarios. Evaluations of current levees and dams reveal that engineered systems built to surpass former hydrological standards are becoming more vulnerable to unprecedented floods [25,70].

- (ii)

- GI—wetlands, riparian zones, forests, floodplains—provide functions like infiltration, storage, cooling, and biodiversity support; however, these systems alone cannot always protect densely populated or highly modified landscapes. GI is recognized for multi-functionality, offering climate adaptation, risk reduction, and ecological services, but also requires governance and careful implementation.

The concept of hybrid resilience (HR) emerges from the recognition that neither conventional gray infrastructure nor purely ecological, nature-based systems alone can adequately address the increasing hydrological instability of the Anthropocene [8,70,71]. HR encompasses the ability to manage floods, sustain water quality, buffer droughts, and support biodiversity under conditions of climatic and anthropogenic stress through the combined use of green (nature-based) and gray (engineered) infrastructures [8,70]. Hybrid (green-gray) systems (Figure 5) integrate the immediate protective capacity of engineered structures with the adaptive, regenerative characteristics of ecosystems. This combination provides functional complementarity: gray elements deliver immediate risk reduction, while green elements enhance long-term resilience through ecological progression, energy dissipation, and hydrological retention. While gray components offer immediate and predictable levels of safety, the protective and ecological functions of green elements increase over time as vegetation establishes, sediment accumulates, and ecological connectivity improves.

Figure 5.

The hybrid resilience conceptualization.

It is crucial to emphasize that hybrid resilience represents a degree of functional integration between naturally occurring green components and man-made gray infrastructure, rather than a measure of ecological optimality. In this context, hybrid resilience does not imply ecological perfection; instead, it reflects the capacity of engineered and natural elements to operate jointly and adaptively under real-world constraints, including land-use pressures, infrastructure aging, and climate variability.

Considering these, the definition of the HR concept (in hydrology) can be slightly modified, adapted for a green-gray infrastructure: the ability to mitigate floods, buffer droughts, and support biodiversity under extreme climate conditions and anthropogenic stress.

3.3.2. Temporal Dynamics of Hybrid Resilience Development

A fundamental characteristic of HR is that it takes time to develop and manifest. Because of its ecological component, HR is not static and keeps evolving and adjusting. While gray infrastructure can be planned and constructed within a matter of years, green infrastructure develops through slower ecological processes that may take decades to reach full functionality. The GIY offer immediate and predictable levels of safety, while the protective and ecological functions of GI increase over time as vegetation establishes, sediment accumulates, and ecological connectivity improves.

The time necessary to “develop” a hybrid infrastructure is not a one-digit number: construction of the gray parts may take a few years, while the achievement of full hybrid performance and co-benefits is on the order of decades, tied to ecological maturation, social acceptance, and hydrotechnical infrastructure life cycle. Thus, hybrid systems go through stages of development. The engineered components provide instant, predictable safety, whereas the ecological components grow slowly, enhancing system performance over time in a less controllable manner.

Since HR is a relatively “new” concept, the design methods for hybrid infrastructures are still “in the research stage”, and their effectiveness needs to be evaluated via simulations and long-term monitoring [25,70]. Because of the uncertainty involved with ecosystem-based risk reduction, the rules and procedures evolve gradually as more data accumulates, extending the timescale for complete implementation. Hybrid resilience requires a long-term planning strategy. Its progress takes place in three overlapping stages [8,70]:

- (i)

- Stage 1: 0–5 years, construction of gray infrastructure, which provides immediate protection; some green elements can be introduced (not yet functional), including grading, planting, and wetland creation.

- (ii)

- Stage 2: 5–20 years, development of green infrastructure, including riparian vegetation, wetlands, reed beds, etc.; ecological functions achieve a certain maturity; green and gray components begin operating together, generating complementarity.

- (iii)

- Stage 3: 20+ years, ecological systems reach functional maturity, providing sustained flood mitigation, water-quality improvements, and biodiversity benefits; the hybrid system becomes a fully integrated socioecological infrastructure; depending on the initial design, the gray infrastructure may require major reinvestment and/or rehabilitation works, enabling redesign toward more nature-based or lighter-gray solutions.

Obviously, hybrid systems are never “complete” at construction. Its performance is expected to improve over time as vegetation grows and the ecological connection improves. The three HR stages describe generalized temporal trajectories derived from landscape evolution and reservoir age, recognizing that ecological development is gradual, geographically variable, and non-synchronized across sites. Most of the reservoirs built in the 1960s and 1970s have Stage 3 characteristics (Chirița, Podu Iloaiei), whereas reservoirs commissioned in later decades have Stage 2 or Stage 1 features (e.g., Rediu), which reflect shorter ecological succession periods and less development of green infrastructure.

3.3.3. Hybrid Resilience: Can It Be Designed, Anticipated, Accelerated, or Delayed?

If allowed, the green component may appear on its own. In fact, as in the case of Bahlui’s hydrodynamic system, a lot of reservoirs and dams that are older than the term “resilience” itself are nowadays working in a hybrid mode. The hybrid resilience simply occurred as the green component began to grow and interact with the gray one. Nowadays, when the benefits of this association are acknowledged, the hybrid resilience can be studied, anticipated, and/or modeled [25]. Because the combined effects of green and gray components rely on how they are positioned in relation to one another, hybrid infrastructures necessitate careful design of their spatial configurations [70].

The development of the green component can be anticipated to a certain degree. However, both natural and anthropogenic influences can interfere with the normal progress of ecological resilience. Climate events and land-use changes can either slow down or accelerate the growth of the green infrastructure. Therefore, modeling and ecological practice can be used to anticipate HR, but full forecasting is impossible due to social and climatic unpredictability [8].

Ecological processes that would usually take decades can be accelerated by planting mature plants, creating wetlands, and repairing riparian zones. Reservoir management can increase ecological resilience downstream more rapidly. In the same manner, the ecological processes can be delayed by extreme weather events or by human activities. Stakeholders’ decisions, implementation of adequate legislation, can also contribute to the faster development of hybrid infrastructures.

HR is a dynamic concept that is always evolving. It is somewhat predictable, manageable, and designable. Its development can be strategically accelerated by ecological progress and engineering assistance. Its evolution may be slowed down by social restraints, institutional obstacles, or natural events. Long-term planning, consistent ecological knowledge, and adaptive governance are essential for successful hybrid resilience implementation [8].

3.3.4. Actual Examples of Hybrid Resilience in Bahlui’s River Hydrographic Basin

In the case of the Bahlui River, any deliberate connection with concepts like GIY, GI, and HR can be ruled out since the first dams in the Bahlui hydrographic system were built ten years prior to the emergence of the “resilience” concept [63], and all of them were built during Communism, before the 1990s. The majority of the dams in this hydrographic basin are presently in the mid- to late-life range of a conventional earthfill dam, as was indicated in Section 3.2. This points out that the majority of the dams had enough time to complete all the steps necessary for HR development (see Section 3.3.2). The hybrid resilience in Bahlui’s basin developed progressively over several decades (without recognition), almost concurrently with the creation and acceptance of the HR concept.

The hybridization level of the dams in Bahlui’s hydrographic basin can now be assessed using their actual constructive characteristics and functions (see Section 2.1), the previously discussed GYI–GI and HR concepts (Section 3.3.1, Section 3.3.2 and Section 3.3.3), as well as local, national, and international decisions and laws concerning the protected natural areas in Romania [72]. When addressing flood and drought mitigation, the term hybridization level refers to the degree of functional integration between man-made gray infrastructures and naturally occurring green components. Table 15 shows the classification proposed for the 17 dams: high, moderate, and low HR level.

Table 15.

Estimating hybrid hydrological resilience using institutional, functional, ecological, and structural data.

The Bahlui reservoir system is more than just a collection of dams; parts of it already operate as a hybrid resilience network (Sârca–Podu Iloaiei; Tansa–Belcești–Plopi; Aroneanu–Ciric III), with GIY offering controlled flood and drought mitigation, storage, and supply, and GI offering complementary services and ecosystem improvement. With the correct ecological and operational strategies, the Bahlui system might become a regional model of hydrological resilience and hydrologically sound water management. Assessing the time required for achieving the GIY–GI interaction in Bahlui’s basin is of high importance for future design strategies aiming at HR. The reservoirs constructed in the 1960s and 1980s are now GI mature (multiple decades of development should be considered).

Overall, the Bahlui reservoir system shows how anthropogenic structures and self-organized natural processes can co-evolve over time to create multifunctional structures that are safer, more biodiverse, and more ecologically integrated than either purely natural or purely constructed systems alone. While naturally occurring wetlands, marshy reservoir tails, and riparian belts provide biological flexibility and adaptive potential to climate change, the constructed components provide structural strength.

To analyze the HR uniformly across all reservoirs, three categories of indicators were employed:

- (1)

- Green infrastructure (GI) development: the emergence and expansion of wetland areas, marshes and swamps, or reed beds, especially in reservoir tails and shallow margins; riparian vegetation belts and vegetated slopes.

- (2)

- Evidence of functional green-gray integration (e.g., dense vegetation increases hydraulic roughness, which attenuates the peaks of flash floods; wetland plants buffer droughts by acting as sponges, trapping and releasing water gradually).

- (3)

- Institutional and administrative indicators (e.g., the administrative authority’s periodic reports, inclusion in protected natural areas), which are used as supporting, non-deterministic factors.

Using the available historical data, land-use maps, field observations, the literature records, and present functioning features from administrative technical reports, each reservoir was qualitatively assessed regarding the degree of hybrid resilience. Based on a combination of these indicators, three classes of reservoirs (hybridization levels) were identified (Table 15):

- (1)

- High HR: Defined by well-developed natural ecosystems that actively interact with gray infrastructure to mitigate floods and droughts.

- (2)

- Moderate HR: Partial or emerging green infrastructure that provides gray infrastructure with complementary ecological support, with clear potential for upgrading the hybridization level.

- (3)

- Low HR: The ecological component is underdeveloped, and the gray infrastructure dominates the system.

The HR classes presented in Table 15 reflect observed and documented levels of green-gray integration based on qualitative indicators, not quantified measures of ecosystem health or performance.

4. Conclusions

Using the Bahlui River basin as an illustrative example of a heavily regulated hydrographic basin in northeast Romania, this study offers a long-term, basin-scale evaluation of how artificial reservoirs help mitigate hydrological extremes.

After more than 50 years of operation, the analysis shows that flood control is still the most reliable and enduring reservoir function. Despite infrastructure aging, sedimentation, changing land use and urbanization levels, and fluctuating management priorities, peak-flow attenuation remains effective across the reservoir network, confirming the enduring role of artificial reservoirs in flood-risk reduction.

On the other hand, after socioeconomic changes started in 1989, drought mitigation functions, such as irrigation and industrial water supply, have significantly diminished. Though this slow decline has not resulted in a complete loss of drought-buffering capability. Instead, the establishment of riparian vegetation, wetlands, marshy reservoir tails, and reed beds are examples of natural systems that have progressively enhanced passive water storage and low-flow buffering. Over time, various levels of functional integration between gray infrastructures and naturally occurring green components have developed. The concept of hybrid hydrological resilience is used to explain this long-term evolution as a transition from purely engineered control toward multifunctional green-gray systems. It is important to note that hybrid resilience represents a degree of functional integration between naturally occurring green components and man-made gray infrastructure, and not a measure of ecological health. Hybrid resilience does not imply ecological perfection; it reflects the capacity of artificial and natural elements to operate jointly and adaptively under real-world constraints, including land-use pressures, infrastructure aging, and climate change.

Owing to its unique features, the Bahlui River basin represents an illustrative case of unplanned hybrid resilience emergence. It demonstrates how aged artificial reservoirs can maintain effective flood-control performance while gradually developing complementary ecological functions that support drought mitigation. The reservoirs’ long-term resistance to hydrological extremes can be enhanced in an economical, environmentally responsible, and flexible manner by identifying, controlling, and eventually designing hybrid resilience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: N.M. and M.-T.N.; methodology: A.-I.B.; software: M.G.B. and D.T.; validation: V.B., C.D.B. and Ș.C.; formal analysis: A.-I.B.; investigation: C.D.B.; resources: Ș.C.; data curation: D.T. and V.B.; writing—original draft preparation: N.M. and M.-T.N.; writing—review and editing: M.-T.N.; visualization: M.G.B.; supervision: N.M.; project administration: Ș.C.; funding acquisition: N.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rahmani, F.; Fattahi, M.H. Investigation of alterations in droughts and floods patterns induced by climate change. Acta Geophys. 2024, 72, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Yang, Y. Climate Change and Hydrological Extremes. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 2024, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkins, G.A.; Renard, B.; Whitfield, P.H.; Laaha, G.; Stahl, K.; Hannaford, J.; Burn, D.H.; Westra, S.; Fleig, A.K.; Araújo Lopes, W.T.; et al. Climate Driven Trends in Historical Extreme Low Streamflows on Four Continents. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2022WR034326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granata, F.; Zhu, S.; Di Nunno, F. Hydrological extremes in the Mediterranean basin: Interactions, impacts, and adaptation in the face of climate change. Reg. Environ. Change 2025, 25, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Maharjan, S.; Fisher, J.B.; Piechota, T.; El-Askary, H. Escalating Hydrological Extremes and Whiplashes in the Western U.S.: Challenges for Water Management and Frontline Communities. Earth’s Future 2025, 13, e2024EF005447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, B.; Spence, C. James buttle review: A resilience framework for physical hydrology. Hydrol. Process. 2023, 37, e14926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles-Wilhelm, F.; Matthews, J.H.; Karres, N.; Abell, R.; Dalton, J.; Kang, S.-T.; Liu, J.; Maendly, R.; Matthews, N.; McDonald, R.; et al. Emerging themes and future directions in watershed resilience research. Water Secur. 2023, 18, 100132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granata, F.; Di Nunno, F. Pathways for Hydrological Resilience: Strategies for Adaptation in a Changing Climate. Earth Syst. Environ. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinca, L.; Murariu, G.; Lupoae, M. Understanding the Ecosystem Services of Riparian Forests: Patterns, Gaps, and Global Trends. Forests 2025, 16, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J.; Falkenmark, M.; Allan, T.; Folke, C.; Gordon, L.; Jägerskog, A.; Kummu, M.; Lannerstad, M.; Meybeck, M.; Molden, D.; et al. The unfolding water drama in the Anthropocene: Towards a resilience-based perspective on water for global sustainability. Ecohydrology 2014, 7, 1249–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Baldassarre, G.; Martinez, F.; Kalantari, Z.; Viglione, A. Drought and flood in the Anthropocene: Feedback mechanisms in reservoir operation. Earth Syst. Dynam. 2017, 8, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFries, R.S.; Rudel, T.; Uriarte, M.; Hansen, M. Deforestation driven by urban population growth and agricultural trade in the twenty-first century. Nat. Geosci. 2010, 3, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Tiwari, A.K.; Singh, G.S. Managing riparian zones for river health improvement: An integrated approach. Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 2021, 17, 195–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Shang, Y. Nexus of dams, reservoirs, climate, and the environment: A systematic perspective. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 12707–12716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellner, E. The controversial debate on the role of water reservoirs in reducing water scarcity. WIREs Water 2021, 8, e1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Połomski, M.; Wiatkowski, M. Impounding Reservoirs, Benefits and Risks: A Review of Environmental and Technical Aspects of Construction and Operation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, R.J.; Escuder-Bueno, I. Dam Safety History and Practice: Is There Room for Improvement? Infrastructures 2023, 8, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erpicum, S.; Crookston, B.M.; Bombardelli, F.; Bung, D.B.; Felder, S.; Mulligan, S.; Oertel, M.; Palermo, M. Hydraulic structures engineering: An evolving science in a changing world. WIREs Water 2021, 8, e1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondolf, M.; Yi, J. Dam Renovation to Prolong Reservoir Life and Mitigate Dam Impacts. Water 2022, 14, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelakis, A.N.; Baba, A.; Valipour, M.; Dietrich, J.; Fallah-Mehdipour, E.; Krasilnikoff, J.; Bilgic, E.; Passchier, C.; Tzanakakis, V.A.; Kumar, R.; et al. Water Dams: From Ancient to Present Times and into the Future. Water 2024, 16, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Merwade, V. From single to multi-purpose reservoir: A framework for optimizing reservoir efficiency. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2024, 60, 1144–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellner, E.; Brunner, M.I. Reservoir Governance in World’s Water Towers Needs to Anticipate Multi-purpose Use. Earth’s Future 2021, 9, e2020EF001643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, S.; Karami, E. Sustainability assessment of dams. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 2919–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, P.; Guan, X.; Yan, D. Quantitative assessment of safety, society and economy, sustainability benefits from the combined use of reservoirs. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 324, 129242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Sun, J.; Hu, B.; Xu, Y.J.; Rousseau, A.N.; Zhang, G. Can the combining of wetlands with reservoir operation reduce the risk of future floods and droughts? Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 27, 2725–2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcoie, N.; Chihaia, Ș.; Hrăniciuc, T.A.; Balan, C.D.; Drăgoi, E.N.; Nechita, M.-T. Linking Nutrient Dynamics with Urbanization Degree and Flood Control Reservoirs on the Bahlui River. Water 2024, 16, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcoie, N.; Toma, I.O.; Chihaia, Ș.; Hrăniciuc, T.A.; Toma, D.; Balan, C.D.; Drăgoi, E.N.; Nechita, M.-T. Anthropogenic River Segmentation Case Study: Bahlui River from Romania. Hydrology 2025, 12, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionuț, M. Bazinul Hidrografic Bahlui—Studiu Hidrologic; Facultatea de Geografie şi Geologie, Universitatea “Alexandru Ioan Cuza” Iaşi: Iasi, Romania, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Minea, I. The evaluation of the water chemistry and quality for the lakes from the south of the Hilly Plain of Jijia (Bahlui drainage basin). Lakes Reserv. Ponds 2010, 4, 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Ludikhuize, D.; Savin, A.; Schropp, M. A Sobek Model for the Bahlui River; Rijksinstituut voor Integraal Zoetwaterbeheer en Afvalwaterbehandeling (RWS, RIZA): Lelystad, The Netherlands, 2004; 49p. [Google Scholar]

- Minea, I. Minimum discharge in Bahlui basin and associated hydrologic risks. Aerul si Apa. Compon. Ale Mediu. 2010, 508–515. [Google Scholar]

- Mediului, M. Atlasul Cadastrului Apelor din România; Editura Romcart SA: București, Romania, 1992; p. 448. [Google Scholar]

- ANPA. Regulament de exploatare: Acumulare Ezăreni. Râul Ezăreni. Bazinul hidrografic Prut. Administraţia Naţională “Apele Române”, Direcţia Apelor Prut 2010.

- ANPA. Regulament de exploatare: Acumulare Ciurbești. Râul Locii. Bazinul hidrografic Prut. Administraţia Naţională “Apele Române”, Direcția Apelor Prut 2010.

- ANPA. Regulament de exploatare: Acumulare Vânători. Râul Cacaina. Bazinul hidrografic Prut. Administraţia Națională “Apele Române”, Direcţia Apelor Prut 2009.

- ANPA. Regulament de exploatare: Acumulare Sârca. Râul Valea Oii. Bazinul hidrografic Prut. Administraţia Națională “Apele Române”, Direcţia Apelor Prut 2009.

- ANPA. Regulament de exploatare: Acumulare Cornet. Râul Cornet. Bazinul hidrografic Prut. Administraţia Națională “Apele Române”, Direcţia Apelor Prut 2009.

- ANPA. Regulament de exploatare: Ciric III. Râul Ciric. Bazinul hidrografic Prut. Administraţia Naţională “Apele Române”, Direcția Apelor Prut 2009.

- ANPA. Regulament de exploatare: Acumulare Cârlig. Râul Cacaina. Bazinul hidrografic Prut—Bârlad. Administraţia Națională “Apele Române”, Directia Apelor Prut 2009.

- ANPA. Regulament de exploatare: Acumularea Pârcovaci, Râul Bahlui, Bazinul hidrografic Prut. Administraţia Națională “Apele Române”, Direcția Apelor Prut 2009.

- ANPA. Regulament de exploatare: Acumularea Rediu. Râul Rediu. Bazinul hidrografic Prut. Administrația Națională “Apele Române”, Direcţia Apelor Pru42 2009.

- Societatea de Construcții, Asamblări, Sarcini și Acoperișuri. Regulament de Exploatare: Amenajare Hidrotehnică Chirița; Râul Chirița, Bazinul hidrografic Prut: Iași, Romania, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- ANPA. Regulament de exploatare: Acumularea Tansa Belcesti. Râul Bahlui. Districtul de bazin hidrografic Prut—Bârlad. Administrația Națională Apele Române, Administrația Bazinală de Apă Prut—Bârlad 2021.

- ANPA. Regulament de exploatare: Acumularea Plopi. Râul Gurguiata. Bazinul hidrografic Prut. Administrația Națională “Apele Române”, Administraţia Bazinală de Apă Prut Bârlad 2017.

- ANPA. Regulament de exploatare: Acumulare Podu Iloaiei. Curs de apă Bahlueț. Bazinul hidrografic Prut. Administrația Națională “Apele Române”, Administraţia Bazinală de Apă Prut Bârlad 2014.

- ANPA. Regulament de exploatare Aroneanu. Râul Ciric. Bazin hidrografic Prut. Administrația Națională “Apele Române”, Administrația Bazinală de Apă Prut—Bârlad 2013.

- ANPA. Regulament de exploatare: Acumularea Cucuteni. Râul Voinești. Districtul de bazin hidrografic Prut—Bârlad. Administrația Națională “Apele Române”, Administraţia Bazinală de Apă Prut—Bârlad 2012.

- ANPA. Regulament de exploatare: Aculumarea Ciurea. Râul Nicolina. Districtul de bazin hidrografic Prut—Bârlad. Administrația Națională “Apele Române”, Administrația Bazinală de Apă Prut—Bârlad 2010.

- ANPA. Regulament de exploatare acumularea Bârca. Râul Locii. Bazinul hidrografic Prut. Administrația Națională “Apele Române”, Administraţia Bazinală de Apă Prut—Bârlad 2010.

- Dumitrache, L.; Zamfir, D.; Nae, M.; Simion, G.; Stoica, I.-V. The Urban Nexus: Contradictions and Dilemmas of (Post) Communist (Sub) Urbanization in Romania. Hum. Geogr. J. Stud. Res. Hum. Geogr. 2016, 10, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincze, E. Deindustrialization and the real-estate–development–driven housing regime. The case of Romania in global context. Stud. Univ. Babes-Bolyai-Sociol. 2023, 68, 25–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubay-Anongphouth, I.O.; Alfaro, M. Delayed instabilities of water-retaining earth structures. Front. Built Environ. 2022, 8, 927137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.J. Earth dams. In Earth Structures Engineering; Mitchell, R.J., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1983; pp. 163–218. [Google Scholar]

- Pytharouli, S.; Michalis, P.; Raftopoulos, S. From Theory to Field Evidence: Observations on the Evolution of the Settlements of an Earthfill Dam, over Long Time Scales. Infrastructures 2019, 4, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, B.; Dobay, K.M.; Sabates-Wheeler, R. Revisiting group farming in a post-socialist economy: The case of Romania. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 81, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacu, C. The collapse of the state industry in Romania: Between political and economic drivers. Hum. Geogr. J. Stud. Res. Hum. Geogr. 2016, 10, 116–127. [Google Scholar]

- EU. EU Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EC); EU: Brussels, Belgium, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. Directive 2007/60/EC on the assessment and management of flood risks. Off. J. Eur. Union 2007, L288, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the European Union. Council Directive 92/43/EEC on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora (Habitats Directive). Off. J. Eur. Communities 1992, L206, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Bâra, A.; Văduva, A.G.; Oprea, S.-V. Anomaly Detection in Weather Phenomena: News and Numerical Data-Driven Insights into the Climate Change in Romania’s Historical Regions. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2024, 17, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagavciuc, V.; Scholz, P.; Ionita, M. Hotspots for warm and dry summers in Romania. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 22, 1347–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamo, N.; Al-Ansari, N.; Sissakian, V.; Laue, J.; Knutsson, S. Dams safety: Inspections, safety reviews, and legislations. J. Earth Sci. Geotech. Eng. 2021, 11, 109–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C. Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1973, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C. Engineering Resilience Versus Ecological Resilience; Engineering Within Ecological Constraints/National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Folke, C. Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Glob. Environ. Change 2006, 16, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunderson, L.H. Ecological Resilience—In Theory and Application. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2000, 31, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayar, K.; Carmichael, D.G.; Shen, X. Resilience and Systems—A Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.; Holling, C.S.; Carpenter, S.R.; Kinzig, A. Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social–ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2004, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Carpenter, S.R.; Walker, B.; Scheffer, M.; Chapin, T.; Rockström, J. Resilience thinking: Integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, F. Concept and application of green and hybrid infrastructure. In Green Infrastructure and Climate Change Adaptation: Function, Implementation and Governance; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks, M.D.; Dowtin, A.L. Come hybrid or high water: Making the case for a Green–Gray approach toward resilient urban stormwater management. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2023, 59, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANMAP, Romania’s Protected Natural Areas. National Agency for Protected Natural Areas. 2025. Available online: https://ananp.gov.ro/ariile-naturale-protejate-ale-romaniei/# (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Paliament, R. The Emergency Ordinance for the Amendment of Law no. 5/2000 Regarding the Approval of the National Territorial Planning Plan—Section IIl—Protected Areas, Official Monitor; Emergency Ordinance no. 49 of 31 August 2016 (689); Romania Government: Bucharest, Romania, 2016.

- Parliament, R. Law on the Approval of the National Territory Planning Plan—Section III—Protected areas, Official Monitor; Law no.5 of 6 March 2000 (152/12 April); Romania Government: Bucharest, Romania, 2000.

- Romania Government. Decision no. 663 of 14 September 2016 on the Establishment of the Protected Natural Area Regime and the Declaration of the Special Avifauna Protection Areas as an Integral Part of the European Ecological Network Natura 2000 in Romania, Official Monitor, (743); Romania Government: Bucharest, Romania, 2016.

- EEA. Acumularile Belcesti, Natura 2000 Site, Code ROSPA0109; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2025. Available online: https://ananp.gov.ro/ariile-naturale-protejate-ale-romaniei/# (accessed on 10 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.