Optimal Design of Energy–Water Systems Under the Energy–Water–Carbon Nexus Using Probability-Pinch Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

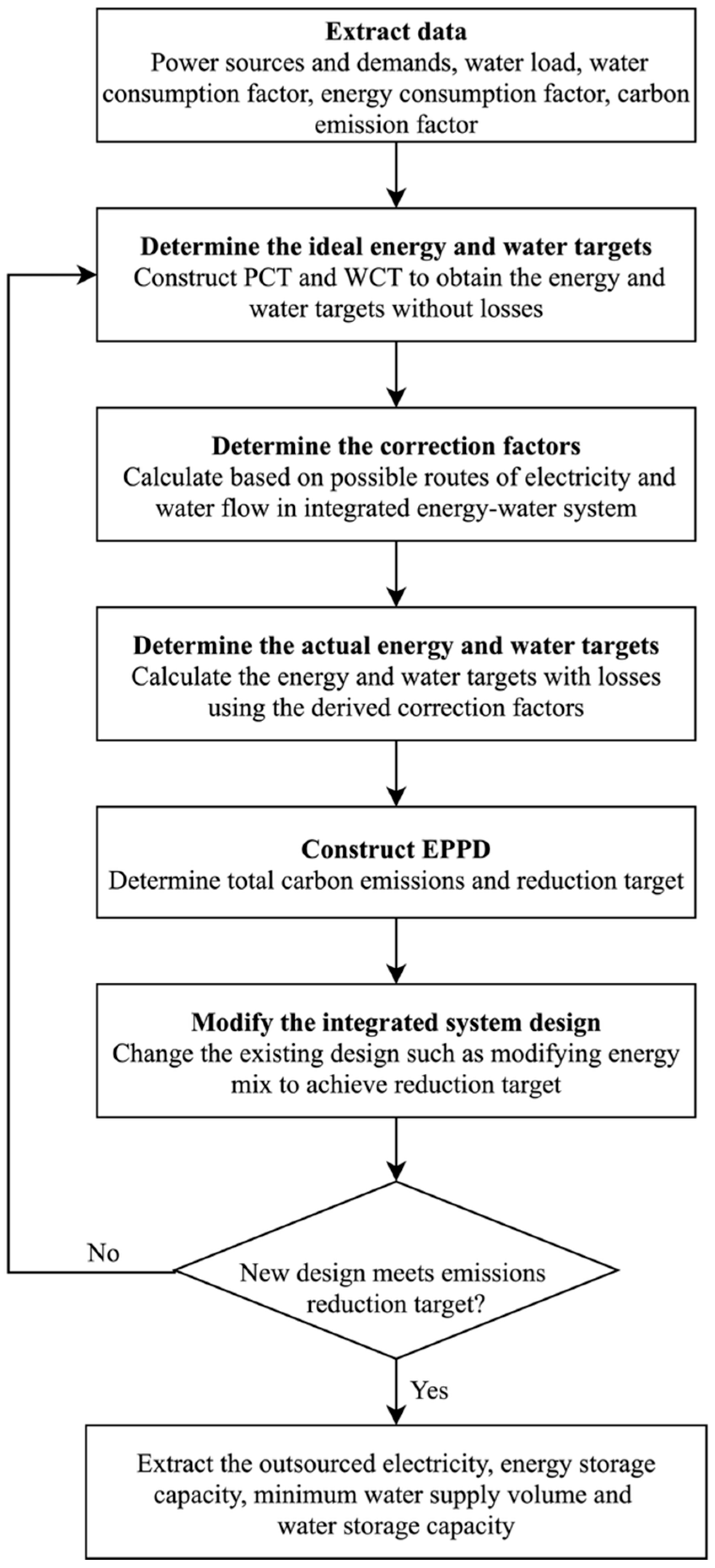

2. Methodology

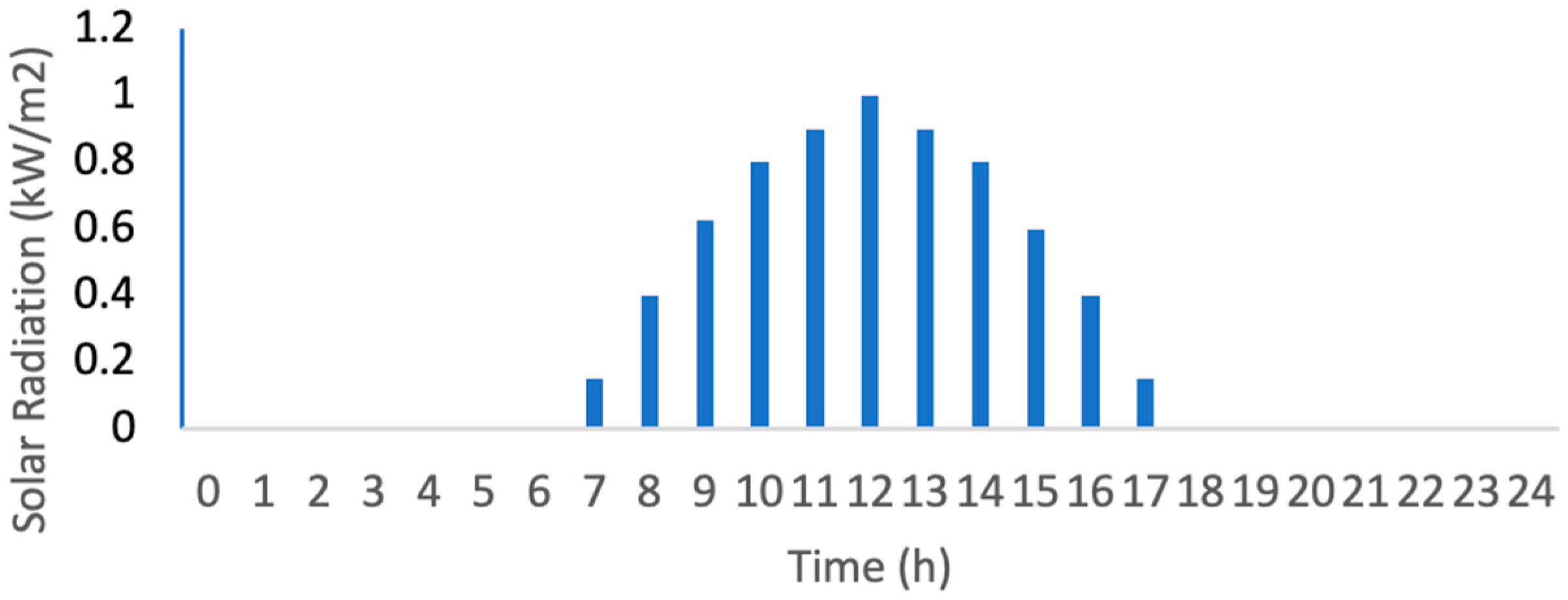

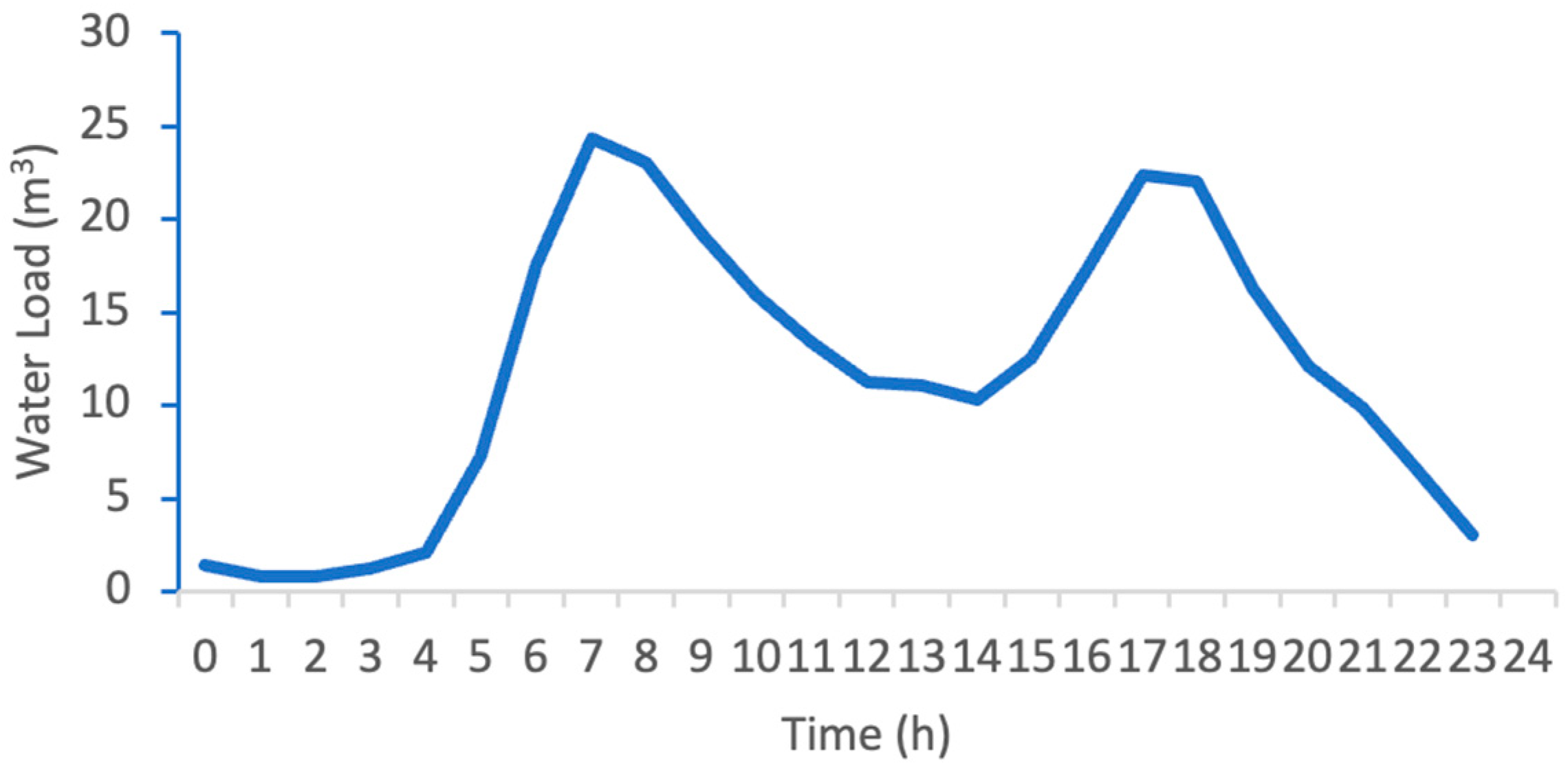

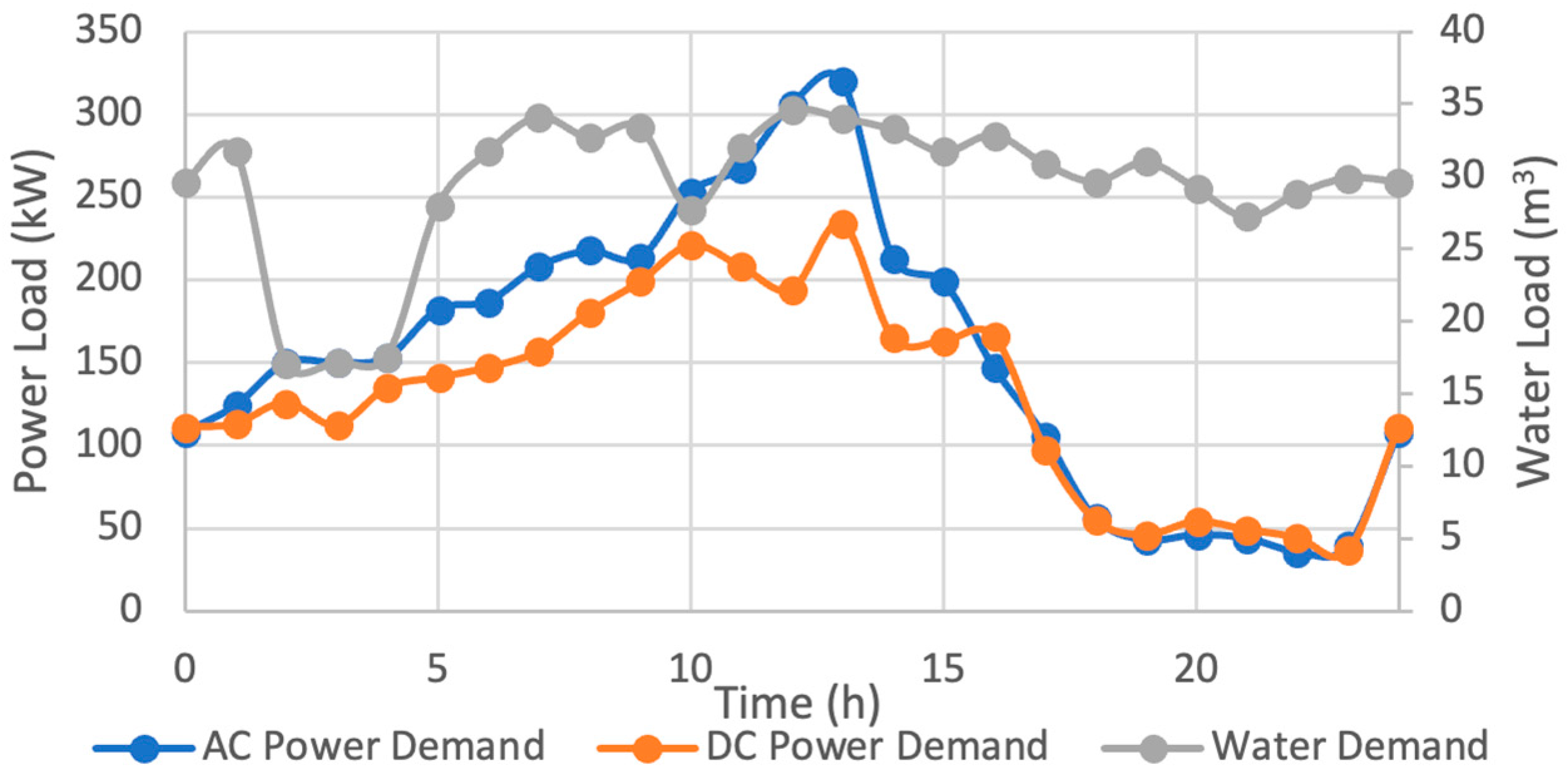

2.1. Step 1: Extract Data

2.2. Step 2: Determine the Ideal Energy and Water Targets

2.3. Step 3: Determine the Correction Factors

2.4. Step 4: Determine the Actual Energy and Water Targets

2.5. Step 5: Construct EPPD

2.6. Step 6: Modify the Integrated System Design

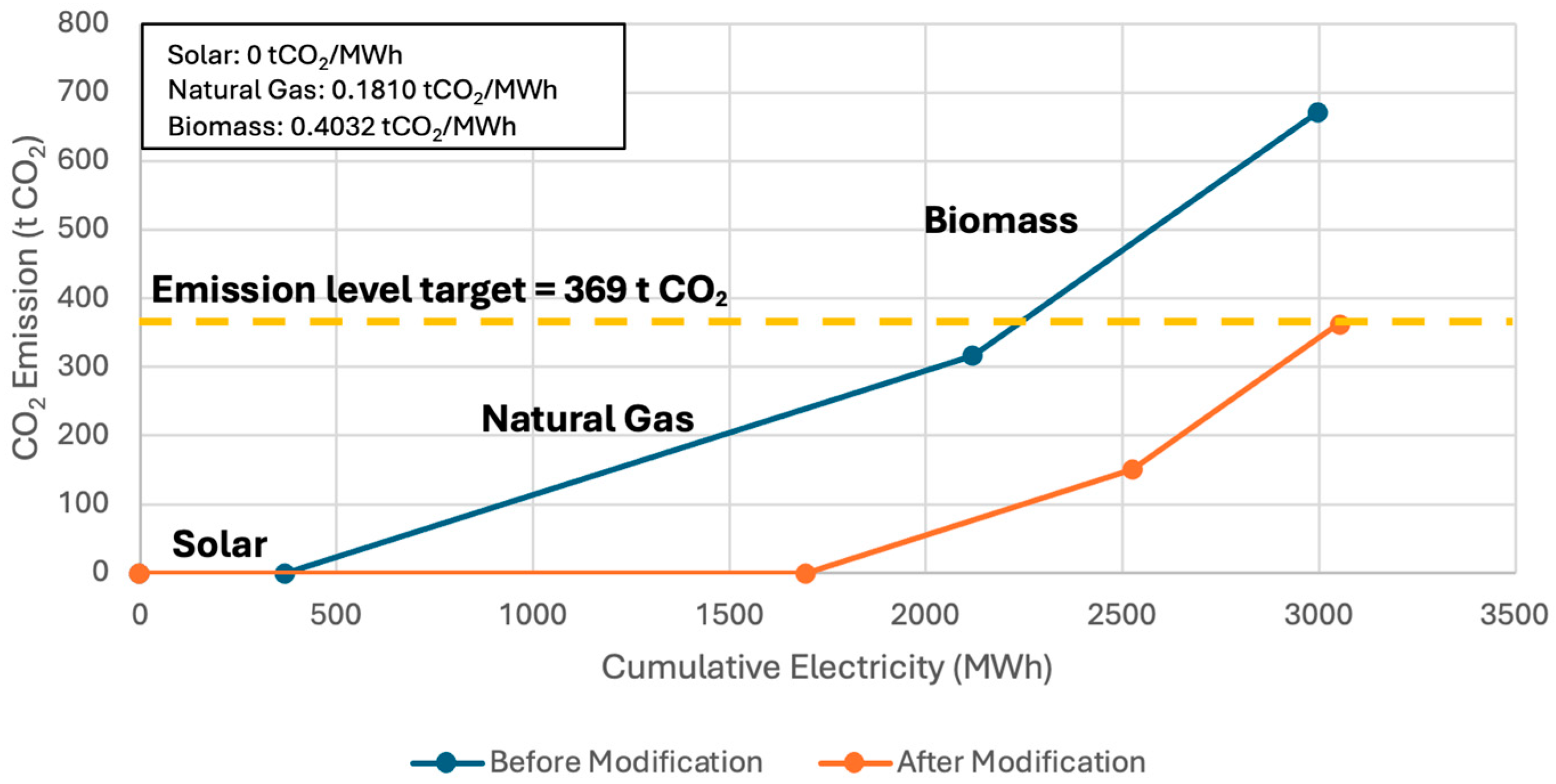

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

- Simultaneous consideration of energy–water interactions with an integrated, system-wide loss model.

- Fast, algebraic computation that eliminates manual matching and is suitable for early-stage design screening.

- Expanded variable set that accounts for efficiencies, losses, storage, outsourcing, and multi-route corrections.

- Demonstrated accuracy with deviation ranges below 10% for large-scale systems, while small systems may exhibit higher sensitivity to individual route losses with deviations of 20–25%.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EWC | Energy–water–carbon |

| EST | Energy-saving technologies |

| PA | Pinch analysis |

| P-PA | Probability-pinch analysis |

| P-PoPA | Probability-power pinch analysis |

| HyPoPA | Hydropower pinch analysis |

| WENT | Water–energy nexus tool |

| PCT | Power cascade table |

| WCT | Water cascade table |

| SCT | Storage cascade table |

| EPPD | Energy planning pinch diagram |

| MILP | Mixed-integer linear program |

| MCDM | Multi-criteria decision-making |

| SDA | Structural Decomposition Analysis |

| EEMRIO | Environmentally extended multi-regional input–output |

References

- Li, J.; Han, J.; Zuo, Q.; Guo, M.; Wang, S.; Yu, L. Water–energy–carbon nexus of China’s Yellow River water allocation schemes. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 332, 119761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamaghani, F.A.; Omidvar, B.; Avami, A.; Nabi-Bidhendi, G. An optimal integrated power and water supply planning model considering Water-Energy-Emission nexus. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 277, 116595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ma, C.; Tan, Z.; Wu, T. Low-carbon development pathways for the water-energy-food-carbon nexus in the Yangtze river economic Belt: Insights from coupling coordination and obstacle degree analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 523, 146399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xiang, N.; Shu, C.; Xu, F. Unveiling the industrial synergy optimization pathways in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration based on water-energy-carbon nexus. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 376, 124528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, L.; Tong, Y.; Jia, X.; Tian, H. Water-energy-carbon nexus assessment of China’s iron and steel industry: Case study from plant level. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 253, 119910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Liang, C.; Sun, H.; Deng, X.; Xue, J.; Chen, F.; Xiao, W.; Zhou, H.; Meng, C.; You, Z. Policy implications of energy-water-carbon emissions nexus based on national policies in China. Energy 2025, 339, 138950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munsamy, M.; Telukdarie, A. Optimising the energy-water-CO2 nexus of a water distribution network. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2022, 11, 100574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargari, L.S.; Joda, F.; Ameri, M. A techno-economic assessment for the water-energy-carbon nexus based on the development of a mathematical model: In the iron and steel industry. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2024, 63, 103653. [Google Scholar]

- Nakkasunchi, S.; Brandoni, C. Water-Energy Nexus Tool: A complete energy assessment model for wastewater treatment plants. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 346, 120477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zeng, X.; Yu, L.; Huang, G.; Li, Y. Planning energy-water nexus systems based on a dual risk aversion optimization method under multiple uncertainties. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 255, 120100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Gardars, E.B.; Rodríguez-Macias, A.; Tena-García, J.L.; Fuentes-Cortés, L.F. Assessment of the water–energy–carbon nexus in energy systems: A multi-objective approach. Appl. Energy 2022, 305, 117872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmchi, A.S.T.; Ifaei, P.; Yoo, C. Smart supply-side management of optimal hydro reservoirs using the water/energy nexus concept: A hydropower pinch analysis. Appl. Energy 2021, 281, 116136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, X.B.; Rozali, N.E.M.; Liew, P.Y.; Klemeš, J.J. Design of integrated energy-water systems using Pinch Analysis: A nexus study of energy-water-carbon emissions. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 322, 129092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, U.; Mohammad Rozali, N.E.; Mahadzir, S. Energy–water–carbon nexus study for the optimal design of integrated energy–water systems considering process losses. Energies 2022, 15, 8605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.H.; Alwi, S.R.W.; Hashim, H.; Lim, J.S.; Rozali, N.E.M.; Ho, W.S. Sizing of Hybrid Power System with varying current type using numerical probabilistic approach. Appl. Energy 2016, 184, 1364–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad Rozali, N.E.; Ho, W.S.; Wan Alwi, S.R.; Manan, Z.A.; Klemeš, J.J.; Cheong, J.S. Probability-Power Pinch Analysis targeting approach for diesel/biodiesel plant integration into hybrid power systems. Energy 2019, 187, 115913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macknick, J.; Newmark, R.; Heath, G.; Hallett, K. Review of Operational Water Consumption and Withdrawal Factors for Electricity Generating Technologies; Technical Report; U.S. Department of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2011.

- Young, R. A Survey of Energy Use in Water Companies; American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Emission Factors for Greenhouse Gas Inventories—Stationary Combustion Emission Factors; Washington, DC, USA, 2014.

- Trubetskaya, A.; Horan, W.; Conheady, P.; Stockil, K.; Moore, S. A Methodology for Industrial Water Footprint Assessment Using Energy-Water-Carbon Nexus. Processes 2021, 9, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Chen, C.; Zhou, M.; Li, B.; Zhao, L.; Shen, L.; Lin, H. Alternating current electrochemistry for energy-efficient contaminant removal and resource recovery in water treatment: A critical review. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 518, 164624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciotti, R.; Kaiser, A.; Sardella, A.; De Nuntiis, P.; Drdácký, M.; Hanus, C.; Bonazza, A. Climate change-induced disasters and cultural heritage: Optimizing management strategies in Central Europe. Clim. Risk Manag. 2021, 32, 100301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, E.A.; Alwi, S.R.W.; Lim, J.S.; Manan, Z.A.; Klemeš, J.J. An integrated Pinch Analysis framework for low CO2 emissions industrial site planning. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 146, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, P.C.; Sitathani, K. Malaysia: Climate Promise Country Report; United Nations Development Programme (UNDP): New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Power Demands | Power Type | Time | Time Interval, h | Power Rating, kW | Electricity Consumption, kWh | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From | To | |||||

| Appliance 1 | AC | 0 | 24 | 24 | 30 | 720 |

| Appliance 2 | DC | 8 | 24 | 16 | 25 | 400 |

| Appliance 3 | AC | 0 | 24 | 24 | 30 | 720 |

| Appliance 4 | DC | 8 | 22 | 14 | 20 | 280 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Electricity Source (kWh) | Electricity Demand (kWh) | Amount of Electricity Transfer (kWh) | Electricity Surplus/Deficit (kWh) | Storage Capacity (kWh) | Outsourced Electricity (kWh) | ||

| Biomass (AC) | Solar (DC) | |||||||

| 0 | ||||||||

| 0 | ||||||||

| 85.00 | 0 | 60.00 | 1.63 | 61.63 | 23.37 | 23.37 | 0 | |

| 1 | ||||||||

| 85.00 | 0 | 60.00 | 1.08 | 61.08 | 23.92 | 47.29 | 0 | |

| 2 | ||||||||

| 85.00 | 0 | 60.00 | 1.08 | 61.08 | 23.92 | 71.22 | 0 | |

| 3 | ||||||||

| 85.00 | 0 | 60.00 | 1.47 | 61.47 | 23.53 | 94.74 | 0 | |

| 4 | ||||||||

| 85.00 | 0 | 60.00 | 2.26 | 62.26 | 22.74 | 117.48 | 0 | |

| 5 | ||||||||

| 85.00 | 0 | 60.00 | 6.98 | 66.98 | 18.02 | 135.51 | 0 | |

| 6 | ||||||||

| 85.00 | 0 | 60.00 | 16.48 | 76.48 | 8.52 | 144.02 | 0 | |

| 7 | ||||||||

| 85.00 | 6.75 | 60.00 | 22.77 | 82.77 | 8.98 | 153.01 | 0 | |

| 8 | ||||||||

| 85.00 | 18.00 | 105.00 | 21.59 | 103.00 | −23.59 | 129.41 | 0 | |

| 9 | ||||||||

| 85.00 | 28.13 | 105.00 | 18.05 | 113.13 | −9.93 | 119.49 | 0 | |

| 10 | ||||||||

| 85.00 | 36.00 | 105.00 | 15.07 | 121.00 | 0.93 | 120.42 | 0 | |

| 11 | ||||||||

| 85.00 | 40.50 | 105.00 | 12.63 | 117.63 | 7.87 | 128.29 | 0 | |

| 12 | ||||||||

| 85.00 | 45.00 | 105.00 | 10.66 | 115.66 | 14.34 | 142.62 | 0 | |

| 13 | ||||||||

| 85.00 | 40.50 | 105.00 | 10.51 | 115.51 | 9.99 | 152.61 | 0 | |

| 14 | ||||||||

| 85.00 | 36.00 | 105.00 | 9.80 | 114.80 | 6.20 | 158.81 | 0 | |

| 15 | ||||||||

| 85.00 | 27.00 | 105.00 | 11.85 | 112.00 | −4.85 | 153.96 | 0 | |

| 16 | ||||||||

| 85.00 | 18.00 | 105.00 | 16.32 | 103.00 | −18.32 | 135.64 | 0 | |

| 17 | ||||||||

| 85.00 | 6.75 | 105.00 | 20.96 | 91.75 | −34.21 | 101.42 | 0 | |

| 18 | ||||||||

| 85.00 | 0 | 105.00 | 20.65 | 85.00 | −40.65 | 60.77 | 0 | |

| 19 | ||||||||

| 85.00 | 0 | 105.00 | 15.38 | 85.00 | −35.38 | 25.39 | 0 | |

| 20 | ||||||||

| 85.00 | 0 | 105.00 | 11.45 | 85.00 | −31.45 | 0 | 6.06 | |

| 21 | ||||||||

| 85.00 | 0 | 105.00 | 9.41 | 85.00 | −29.41 | 0 | 29.41 | |

| 22 | ||||||||

| 85.00 | 0 | 85.00 | 6.26 | 85.00 | −6.26 | 0 | 6.26 | |

| 23 | ||||||||

| 85.00 | 0 | 85.00 | 3.12 | 85.00 | −3.12 | 0 | 3.12 | |

| 24 | ||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Water Source (m3) | Water Demand (m3) | Amount of Water Transfer (m3) | Water Surplus/Deficit (m3) | Storage Capacity (m3) | |

| 0 | ||||||

| 0 | ||||||

| 24.31 | 1.45 | 0.32 | 1.76 | 22.55 | 22.55 | |

| 1 | ||||||

| 24.31 | 0.85 | 0.32 | 1.16 | 23.15 | 45.69 | |

| 2 | ||||||

| 24.31 | 0.85 | 0.32 | 1.16 | 23.15 | 68.84 | |

| 3 | ||||||

| 24.31 | 1.28 | 0.32 | 1.59 | 22.72 | 91.55 | |

| 4 | ||||||

| 24.31 | 2.13 | 0.32 | 2.44 | 21.87 | 113.42 | |

| 5 | ||||||

| 24.31 | 7.23 | 0.32 | 7.54 | 16.77 | 130.18 | |

| 6 | ||||||

| 24.31 | 17.51 | 0.32 | 17.82 | 6.49 | 136.67 | |

| 7 | ||||||

| 24.31 | 24.31 | 0.32 | 24.62 | −0.31 | 136.35 | |

| 8 | ||||||

| 24.31 | 23.04 | 0.32 | 23.35 | 0.96 | 137.31 | |

| 9 | ||||||

| 24.31 | 19.21 | 0.32 | 19.52 | 4.79 | 142.10 | |

| 10 | ||||||

| 24.31 | 15.98 | 0.32 | 16.29 | 8.02 | 150.11 | |

| 11 | ||||||

| 24.31 | 13.35 | 0.32 | 13.66 | 10.65 | 160.76 | |

| 12 | ||||||

| 24.31 | 11.22 | 0.32 | 11.53 | 12.78 | 173.53 | |

| 13 | ||||||

| 24.31 | 11.05 | 0.32 | 11.36 | 12.95 | 186.48 | |

| 14 | ||||||

| 24.31 | 10.29 | 0.32 | 10.60 | 13.71 | 200.18 | |

| 15 | ||||||

| 24.31 | 12.50 | 0.32 | 12.81 | 11.50 | 211.68 | |

| 16 | ||||||

| 24.31 | 17.34 | 0.32 | 17.65 | 6.66 | 218.33 | |

| 17 | ||||||

| 24.31 | 22.36 | 0.32 | 22.67 | 1.64 | 219.97 | |

| 18 | ||||||

| 24.31 | 22.02 | 0.32 | 22.33 | 1.98 | 221.94 | |

| 19 | ||||||

| 24.31 | 16.32 | 0.32 | 16.63 | 7.68 | 229.62 | |

| 20 | ||||||

| 24.31 | 12.07 | 0.32 | 12.38 | 11.93 | 241.55 | |

| 21 | ||||||

| 24.31 | 9.86 | 0.32 | 10.17 | 14.14 | 255.68 | |

| 22 | ||||||

| 24.31 | 6.46 | 0.32 | 6.77 | 17.54 | 273.22 | |

| 23 | ||||||

| 24.31 | 3.06 | 0.32 | 3.37 | 20.94 | 294.15 | |

| 24 | ||||||

| Key Parameters | Ideal Values (Without Losses) | |

|---|---|---|

| PCT | ||

| (usable) | 158.81 kWh | |

| 44.85 kWh | ||

| 2151.23 kWh | ||

| 533.74 kWh | ||

| 191.40 kWh | ||

| 0 kWh | ||

| 0 kWh | ||

| 153.01 kWh | ||

| WCT | ||

| Before iteration | After iteration | |

| 583.44 m3 | 289.29 m3 | |

| 294.15 m3 | 72.48 m3 | |

| 288.97 m3 | 214.15 m3 | |

| 294.47 m3 | 75.14 m3 | |

| 0.31 m3 | 75.14 m3 | |

| AC Source, | 2040.00 kWh |

| DC source, | 302.63 kWh |

| AC demand, | 1707.48 kWh |

| DC demand, | 680.00 kWh |

| DC storage, | 158.81 kWh |

| AC outsource, | 44.85 kWh |

| Components | Power Type | Fraction Values |

|---|---|---|

| Source | AC | = 0.8708 |

| DC | = 0.1292 | |

| Demand | AC | = 0.7152 |

| DC | = 0.2848 | |

| Energy storage | DC | e = 1.0000 |

| Outsourced electricity | AC | f = 1.0000 |

| Routes | Correction Factors | Total Correction Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Components | Type | Fraction Values |

|---|---|---|

| Source | w = 1 | |

| Demand | Water system | = 0.9739 |

| Energy system | = 0.0261 | |

| Storage | z = 1 |

| Routes | Correction Factors | Total Correction Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Key Parameters | Actual Values (with Losses) |

|---|---|

| PCT | |

| (usable) | 128.43 kWh |

| (DoD adjusted) | 160.53 kWh |

| 130.52 kWh | |

| WCT | |

| 13.85 m3/h | |

| 72.48 m3 | |

| Before Modification | After Modification | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA | P-PA | PA | P-PA | |

| Biomass generator capacity (kW) | 85.00 | 85.00 | 65.00 | 65.00 |

| Solar PV panel area (m2) | 300.00 | 300.00 | 750.00 | 750.00 |

| Energy storage capacity (kWh) | 163.90 | 160.53 | 294.66 | 265.89 |

| Outsourced electricity (kWh) | 100.95 | 130.52 | 135.65 | 182.82 |

| Water supply capacity (m3/h) | 13.76 | 13.85 | 13.68 | 13.77 |

| Water storage capacity (m3) | 75.42 | 72.48 | 75.42 | 72.48 |

| Emissions from energy system (t CO2/y) | 300.22 | 300.22 | 229.58 | 229.58 |

| Emissions from water system (t CO2/y) | 40.39 | 39.96 | 40.14 | 39.71 |

| Variable | Description | Unit | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy generation from source i at time t | kWh | [23] | |

| Energy demand of the energy system at time t | kWh | [23] | |

| Energy demand of the water system at time t | kWh | [23] | |

| Water demand of the energy system at time t | m3 | [23] | |

| Water demand of the water system at time t | m3 | [23] | |

| Water consumption factors of energy source i | m3/kWh | [17] | |

| Electricity consumption factor for water supply | kWh/m3 | [18] | |

| Carbon emission factor of power source i | t CO2/MWh | [19] | |

| Carbon emission factors for water processes | t CO2/m3 | [20] | |

| Battery charging/discharging efficiency | % | [16] | |

| DoD | Battery depth of discharge | % | [13] |

| Converter efficiency | % | [16] | |

| Water transfer efficiency | % | [22] |

| Before Modification | After Modification | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA | P-PA | PA | P-PA | |

| Biomass generator capacity (kW) | 100.00 | 100.00 | 60.00 | 60.00 |

| Natural gas generator capacity (kW) | 200.00 | 200.00 | 95.00 | 95.00 |

| Solar PV panel area (m2) | 1000.00 | 1000.00 | 4600.00 | 4600.00 |

| Energy storage capacity (kWh) | 1242.16 | 1250.81 | 2081.35 | 1971.50 |

| Outsourced electricity (kWh) | 688.28 | 754.04 | 1208.65 | 1223.60 |

| Water supply capacity (m3/h) | 34.28 | 33.89 | 33.60 | 33.22 |

| Water storage capacity (m3) | 39.42 | 37.94 | 39.40 | 37.94 |

| Emissions from energy system (t CO2/y) | 670.32 | 670.32 | 362.55 | 362.55 |

| Emissions from water system (t CO2/y) | 102.69 | 101.66 | 100.65 | 99.64 |

| Before Modification | After Modification | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA | P-PA | PA | P-PA | |

| Scenario 1: Low solar (40%) | ||||

| Energy storage capacity (kWh) | 1216.43 | 1207.10 | 214.79 | 213.77 |

| Outsourced electricity (kWh) | 1299.85 | 1317.42 | 2312.52 | 2385.78 |

| Water supply capacity (m3/h) | 34.28 | 33.89 | 33.60 | 33.22 |

| Water storage capacity (m3) | 39.42 | 37.94 | 39.40 | 37.94 |

| Scenario 2: Energy and water demand +20% | ||||

| Energy storage capacity (kWh) | 1025.73 | 1026.00 | 973.97 | 916.77 |

| Outsourced electricity (kWh) | 2015.84 | 2065.34 | 1824.46 | 1820.55 |

| Water supply capacity (m3/h) | 40.86 | 40.40 | 40.18 | 39.73 |

| Water storage capacity (m3) | 47.30 | 45.53 | 47.27 | 45.53 |

| Low Efficiency | Base Case | High Efficiency | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Battery’s charging/discharging efficiency | 85 | 90 | 95 |

| Converter efficiency | 90 | 95 | 98 |

| Water transfer efficiency | 85 | 90 | 95 |

| Energy storage capacity (kWh) | 1660.02 | 1971.50 | 2208.64 |

| Outsourced electricity (kWh) | 1292.73 | 1223.60 | 1182.13 |

| Water supply capacity (m3/h) | 34.79 | 33.22 | 31.65 |

| Water storage capacity (m3) | 37.94 | 37.94 | 37.94 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feng, A.L.D.; Mohammad Rozali, N.E. Optimal Design of Energy–Water Systems Under the Energy–Water–Carbon Nexus Using Probability-Pinch Analysis. ChemEngineering 2025, 9, 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemengineering9060145

Feng ALD, Mohammad Rozali NE. Optimal Design of Energy–Water Systems Under the Energy–Water–Carbon Nexus Using Probability-Pinch Analysis. ChemEngineering. 2025; 9(6):145. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemengineering9060145

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Annie Lau Diew, and Nor Erniza Mohammad Rozali. 2025. "Optimal Design of Energy–Water Systems Under the Energy–Water–Carbon Nexus Using Probability-Pinch Analysis" ChemEngineering 9, no. 6: 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemengineering9060145

APA StyleFeng, A. L. D., & Mohammad Rozali, N. E. (2025). Optimal Design of Energy–Water Systems Under the Energy–Water–Carbon Nexus Using Probability-Pinch Analysis. ChemEngineering, 9(6), 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemengineering9060145