Harnessing an Invasive Species’ Waste for Syngas Production: Fast Pyrolysis of Rosehip Seeds in a Bubbling Fluidized Bed

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

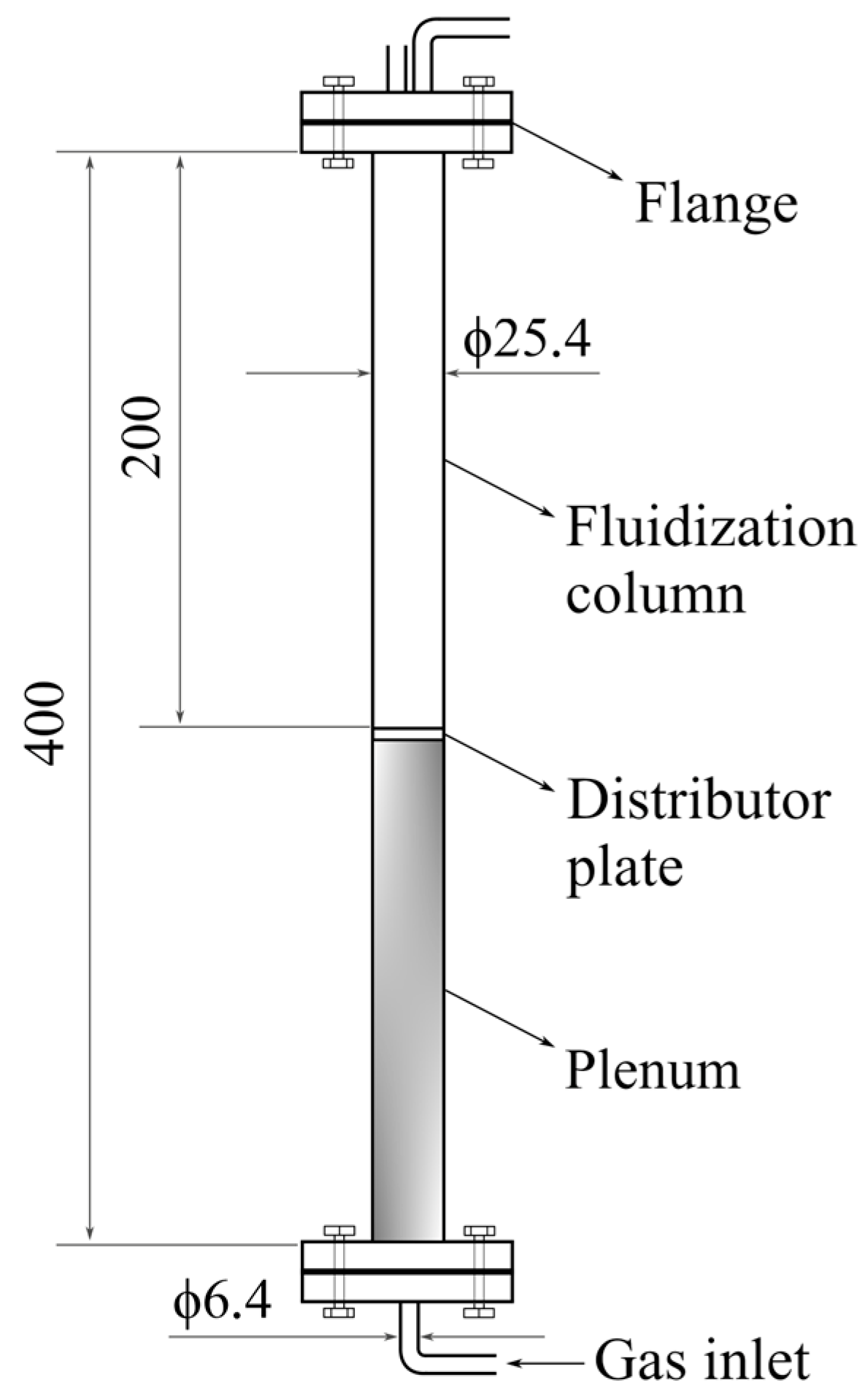

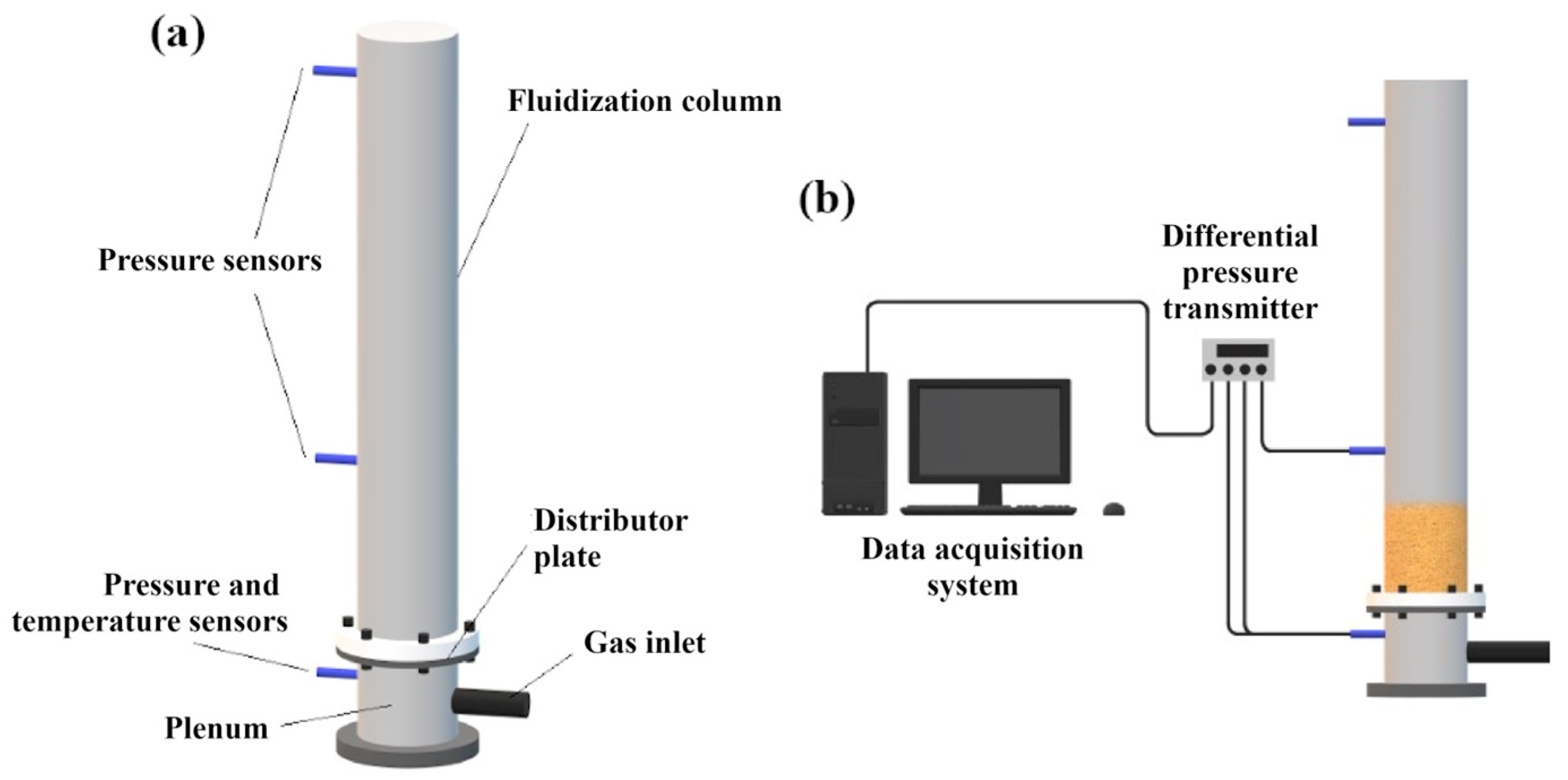

2.2. Minimum Fluidization Velocity Determination

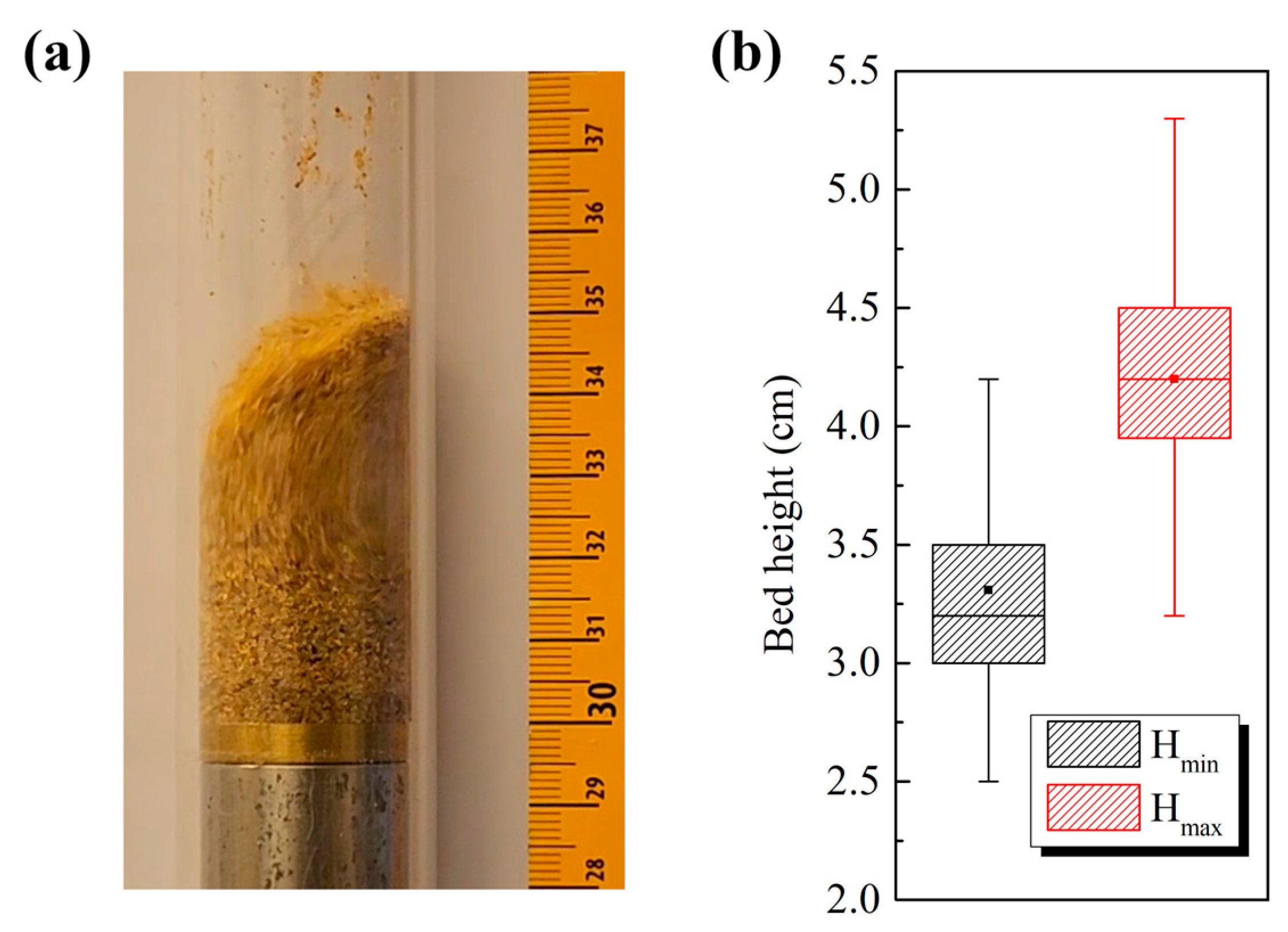

2.3. Bed Expansion Analysis

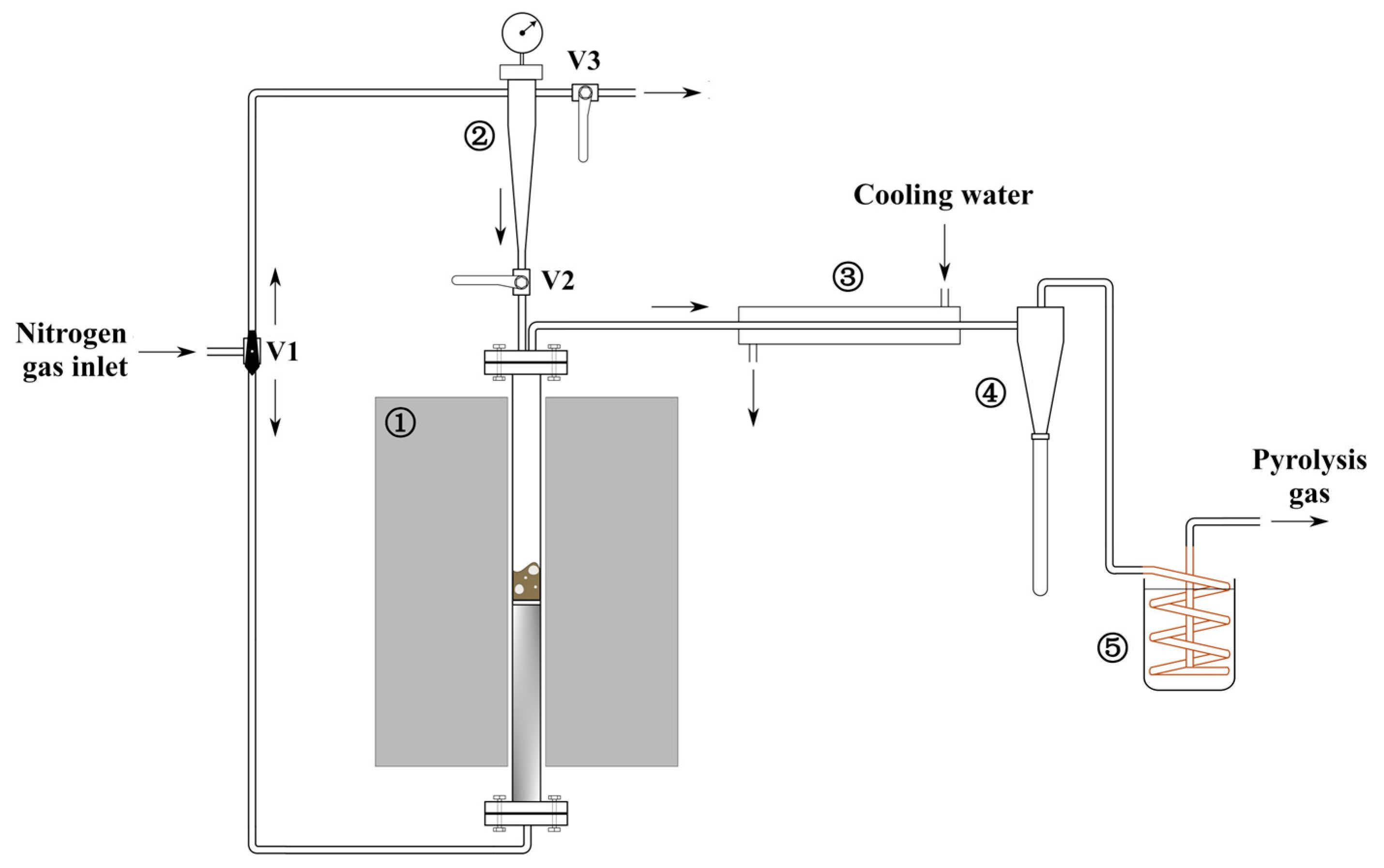

2.4. High-Temperature Pyrolysis Experiments

2.5. Syngas Efficiency Calculations

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Minimum Fluidization Velocity Determination

3.2. Bed Expansion Analysis

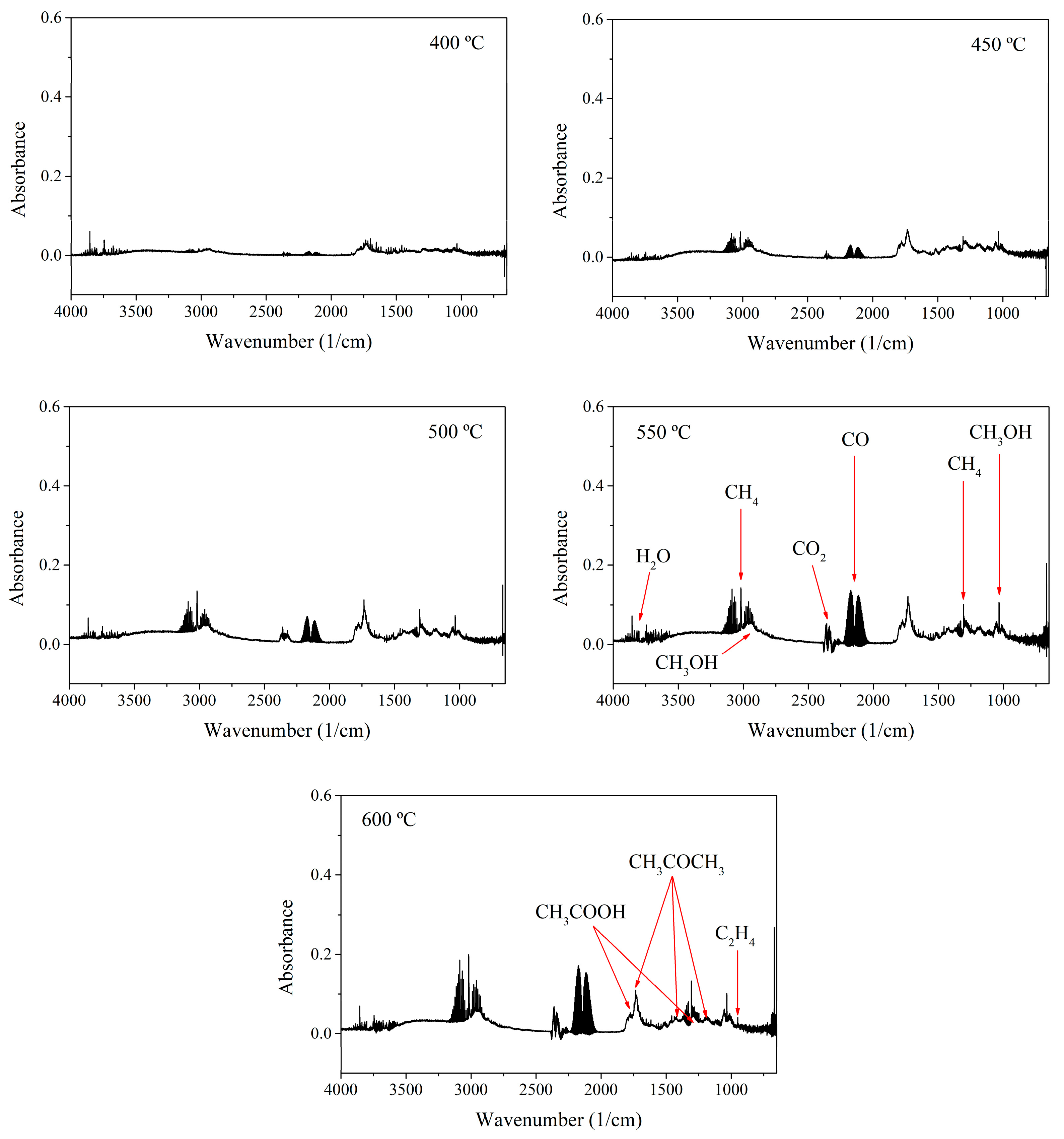

3.3. Analysis of the Syngas Produced by Fast Pyrolysis at Different Temperatures

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CCE | Carbon conversion efficiency |

| ECE | Energy conversion efficiency |

| FID | Flame ionization detector |

| FTIR | Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy |

| LHV | Lower heating value |

| RSW | Rosehip seed waste |

| TCD | Thermal conductivity detector |

References

- Ezeorba, T.P.C.; Okeke, E.S.; Mayel, M.H.; Nwuche, C.O.; Ezike, T.C. Recent Advances in Biotechnological Valorization of Agro-Food Wastes (AFW): Optimizing Integrated Approaches for Sustainable Biorefinery and Circular Bioeconomy. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2024, 26, 101823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Sharma, V.; Tsai, M.L.; Chen, C.W.; Sun, P.P.; Nargotra, P.; Wang, J.X.; Dong, C. Di Development of Lignocellulosic Biorefineries for the Sustainable Production of Biofuels: Towards Circular Bioeconomy. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 381, 129145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matamba, T.; Tahmasebi, A.; Yu, J.; Keshavarz, A.; Abid, H.R.; Iglauer, S. A Review on Biomass as a Substitute Energy Source: Polygeneration Influence and Hydrogen Rich Gas Formation via Pyrolysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2023, 175, 106221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardi, Z.; Shahbeik, H.; Nosrati, M.; Motamedian, E. Waste-to-Energy: Co-Pyrolysis of Potato Peel and Macroalgae for Biofuels and Biochemicals. Environ. Res. 2024, 242, 117614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Li, N.; Pan, Y.; Shi, L.; Xie, G.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Q. Hydrogen-Rich Syngas Production from Tobacco Stem Pyrolysis in an Electromagnetic Induction Heating Fluidized Bed Reactor. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 68, 1271–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, T.A. A Review on the Technologies for Converting Biomass into Carbon-Based Materials: Sustainability and Economy. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2024, 25, 101771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, L.; Wang, R.; Xie, P.; Li, Y.; Huang, X.; Yin, H.; Dong, M. Comparative Investigation on the Pyrolysis of Crop, Woody, and Herbaceous Biomass: Pyrolytic Products, Structural Characteristics, and CO2 Gasification. Fuel 2023, 335, 126940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cen, K.; Li, J.; Jia, D.; Gao, J.; Zhang, L.; Chen, D. Insights into the Interactions between Cellulose and Hemicellulose during Pyrolysis for Optimizing the Properties of Biochar as a Potential Energy Vector. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 223, 120126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trubetskaya, A.; von Berg, L.; Johnson, R.; Moore, S.; Leahy, J.J.; Han, Y.; Lange, H.; Anca-Couce, A. Production and Characterization of Bio-Oil from Fluidized Bed Pyrolysis of Olive Stones, Pinewood, and Torrefied Feedstock. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2023, 169, 105841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinescu, M.; Bucura, F.; Ionete, E.I.; Spiridon, Ş.I.; Ionete, R.E.; Zaharioiu, A.; Marin, F.; Ion-Ebrasu, D.; Botoran, O.R.; Roman, A. Cattle Manure Thermochemical Conversion to Hydrogen-Rich Syngas, through Pyrolysis and Gasification. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 79, 1058–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroga, J.M. Análisis Preliminar de La Cadena de Valor de La Rosa Mosqueta En Bariloche y Zona de Influencia, Argentina. SaberEs 2019, 11, 65–80. Available online: https://www.scielo.org.ar/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S1852-42222019000100004 (accessed on 9 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Torres-Sciancalepore, R.; Asensio, D.; Nassini, D.; Fernandez, A.; Rodriguez, R.; Fouga, G.; Mazza, G. Assessment of the Behavior of Rosa Rubiginosa Seed Waste during Slow Pyrolysis Process towards Complete Recovery: Kinetic Modeling and Product Analysis. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 272, 116340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Sciancalepore, R.; Nassini, D.; Asensio, D.; Bohé, A.; Rodriguez, R.; Fouga, G.; Mazza, G. Synergistic Effects of the Mixing Factor on the Kinetics and Products Obtained by Co-Pyrolysis of Rosa Rubiginosa Rosehip Seed and Husk Wastes. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 302, 118095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Sciancalepore, R.; Nassini, D.; Asensio, D.; Soria, J.; Rodriguez, R.; Fouga, G.; Mazza, G. CO2-Assisted Gasification of Patagonian Rosehip Bio-Wastes: Kinetic Modeling, Analysis of Ash Catalytic Effects, and Product Gas Speciation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 114644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toschi, F.; Zambon, M.T.; Sandoval, J.; Reyes-Urrutia, A.; Mazza, G.D. Fluidization of Forest Biomass-Sand Mixtures: Experimental Evaluation of Minimum Fluidization Velocity and CFD Modeling. Part. Sci. Technol. 2021, 39, 549–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soanuch, C.; Korkerd, K.; Piumsomboon, P.; Chalermsinsuwan, B. Minimum Fluidization Velocities of Binary and Ternary Biomass Mixtures with Silica Sand. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.J.P.; Cardoso, C.R.; Ataíde, C.H. Bubbling Fluidization of Biomass and Sand Binary Mixtures: Minimum Fluidization Velocity and Particle Segregation. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2013, 72, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emiola-Sadiq, T.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Dalai, A. Mixing and Segregation of Binary Mixtures of Biomass and Silica Sand in a Fluidized Bed. Particuology 2021, 58, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannello, S.; Morrin, S.; Materazzi, M. Fluidised Bed Reactors for the Thermochemical Conversion of Biomass and Waste. KONA Powder Part. J. 2020, 37, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xiao, R.; Huang, H.; Xiao, G. Comparison of Non-Catalytic and Catalytic Fast Pyrolysis of Corncob in a Fluidized Bed Reactor. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 1428–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, B.; Li, X.; Zhou, C.; Lv, F.; Zhang, C.; Wang, L.; Yu, M.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, Y.; et al. Co-Pyrolysis of Dyeing Sludge and Pine Sawdust in a Fluidized Bed: Characterization and Analysis of Pyrolytic Products and Investigation of Synergetic Effects. Waste Manag. 2023, 167, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, P. Biomass Gasification, Pyrolysis and Torrefaction. Practical Design and Theory, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Inc.: San Diego, CA, USA, 2013; ISBN 9780123964885. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, T.; Xu, J.; Wu, Y. Hydrogen-Rich Gas Production from Two-Stage Catalytic Pyrolysis of Pine Sawdust with Calcined Dolomite. Catalysts 2022, 12, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, R.H.; Green, D.W. Section 2: Physical and Chemical Data. In Perry’s Chemical Engineers’ Handbook; Mc Graw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 0071542094. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.; Si, H. Experimental Study on Fluidization, Mixing and Separation Characteristics of Binary Mixtures of Particles in a Cold Fluidized Bed for Biomass Fast Pyrolysis. Chem. Eng. Process.—Process Intensif. 2020, 153, 107936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, N.P.; Pedroso, D.T.; Machin, E.B.; Antunes, J.S.; Verdú Ramos, R.A.; Silveira, J.L. Prediction of the Minimum Fluidization Velocity of Particles of Sugarcane Bagasse. Biomass Bioenergy 2018, 109, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilal, N. The Dependence of Solid Expansion on Bed Diameter, Particles Material, Size and Distributor in Open Fluidized Beds. Adv. Powder Technol. 2005, 16, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, J.G. Effects of Temperature and Pressure on Gas-Solid Fluidization. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1996, 51, 167–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, J.; Leaver, J.; Pang, S. Modelling of Enhanced Dual Fluidized Bed Steam Gasification with Integration of Biomass-Specific Devolatilization. Biomass Bioenergy 2026, 204, 108445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaria, L.; Beirow, M.; Mangold, F.; Lopez, G.; Olazar, M.; Schmid, M.; Li, Z.; Scheffknecht, G. Influence of Temperature on Products from Fluidized Bed Pyrolysis of Wood and Solid Recovered Fuel. Fuel 2021, 283, 118922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abduhani, H.; Tursun, Y.; Abulizi, A.; Talifu, D.; Huang, X. Characteristics and Kinetics of the Gas Releasing during Oil Shale Pyrolysis in a Micro Fluidized Bed Reactor. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2021, 157, 105187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Cano, D.; Salinero, J.; Haro, P.; Nilsson, S.; Gómez-Barea, A. The Influence of Volatiles to Carrier Gas Ratio on Gas and Tar Yields during Fluidized Bed Pyrolysis Tests. Fuel 2018, 226, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielsticker, S.; Gövert, B.; Kreitzberg, T.; Habermehl, M.; Hatzfeld, O.; Kneer, R. Simultaneous Investigation into the Yields of 22 Pyrolysis Gases from Coal and Biomass in a Small-Scale Fluidized Bed Reactor. Fuel 2017, 190, 420–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarm, K.K.; Strand, C.L.; Miller, V.A.; Spearrin, R.M. Calibration-Free Breath Acetone Sensor with Interference Correction Based on Wavelength Modulation Spectroscopy near 8.2 μM. Appl. Phys. B Lasers Opt. 2020, 126, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Strand, C.L.; Hanson, R.K. High-Temperature Mid-Infrared Absorption Spectra of Methanol (CH3OH) and Ethanol (C2H5OH) between 930 and 1170 cm−1. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2019, 224, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngohang, F.E.; Fontaine, G.; Gay, L.; Bourbigot, S. Revisited Investigation of Fire Behavior of Ethylene Vinyl Acetate/Aluminum Trihydroxide Using a Combination of Mass Loss Cone, Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy and Electrical Low Pressure Impactor. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2014, 106, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngohang, F.E.; Fontaine, G.; Gay, L.; Bourbigot, S. Smoke Composition Using MLC/FTIR/ELPI: Application to Flame Retarded Ethylene Vinyl Acetate. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2015, 115, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedelich, N. TGA-FTIR. In Evolved Gas Analysis; Carl Hanser Verlag GmbH & Co. KG: München, Germany, 2019; pp. 18–30. ISBN 978-1-56990-809-9. [Google Scholar]

- Tkach, I.; Panchenko, A.; Kaz, T.; Gogel, V.; Friedrich, K.A.; Roduner, E. In Situ Study of Methanol Oxidation on Pt and Pt/Ru-Mixed with Nafion® Anodes in a Direct Methanol Fuel Cell by Means of FTIR Spectroscopy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2004, 6, 5419–5426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sand | RSW 10% | RSW 20% | RSW 40% | RSW 100% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Umf (m/s) | 0.227 | 0.229 | 0.247 | 0.251 | 0.257 |

| 400 °C | 450 °C | 500 °C | 550 °C | 600 °C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2 (mmol/gRSW) | 0.707 | 1.118 | 1.510 | 2.408 | 7.914 |

| CO (mmol/gRSW) | 2.250 | 2.835 | 3.860 | 5.800 | 13.868 |

| CCECO (%) | 5.6 | 7.1 | 9.6 | 14.5 | 34.6 |

| ECEsyn (%) | 4.3 | 5.8 | 7.8 | 12.0 | 31.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Torres-Sciancalepore, R.; Zalazar-García, D.; Rodriguez, R.; Fouga, G.; Mazza, G. Harnessing an Invasive Species’ Waste for Syngas Production: Fast Pyrolysis of Rosehip Seeds in a Bubbling Fluidized Bed. ChemEngineering 2025, 9, 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemengineering9060146

Torres-Sciancalepore R, Zalazar-García D, Rodriguez R, Fouga G, Mazza G. Harnessing an Invasive Species’ Waste for Syngas Production: Fast Pyrolysis of Rosehip Seeds in a Bubbling Fluidized Bed. ChemEngineering. 2025; 9(6):146. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemengineering9060146

Chicago/Turabian StyleTorres-Sciancalepore, Rodrigo, Daniela Zalazar-García, Rosa Rodriguez, Gastón Fouga, and Germán Mazza. 2025. "Harnessing an Invasive Species’ Waste for Syngas Production: Fast Pyrolysis of Rosehip Seeds in a Bubbling Fluidized Bed" ChemEngineering 9, no. 6: 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemengineering9060146

APA StyleTorres-Sciancalepore, R., Zalazar-García, D., Rodriguez, R., Fouga, G., & Mazza, G. (2025). Harnessing an Invasive Species’ Waste for Syngas Production: Fast Pyrolysis of Rosehip Seeds in a Bubbling Fluidized Bed. ChemEngineering, 9(6), 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemengineering9060146