Abstract

This study conducted a comprehensive comparison of two green extraction methods, microwave-assisted extraction (MAE) and ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE), for recovering bioactive phenolic compounds from Pinus pinaster bark. The goal was to valorize timber industry waste and enhance the value of by-products through the development of eco-friendly processes to extract phenolic compounds from Pinus pinaster Aiton subsp. atlantica in northwest Portugal. MAE achieved significantly higher extraction yields than UAE (11.13 vs. 3.47 g extract/100 g bark) and superior total phenolic content (833 vs. 514 mg GAE/g). MAE extracts also exhibited enhanced antioxidant activity in most assays tested (DPPH, ABTS, ORAC, and OxHLIA), while both extracts effectively inhibited lipid peroxidation (TBARS) and showed activity against Gram-positive bacteria. Phenolic profile analysis revealed that MAE recovered a substantially higher amount of total phenolic compounds (230.0 mg/g) compared to UAE (86.95 mg/g), with procyanidins identified as the predominant compounds. The greater recovery of this complex procyanidin mixture by MAE is strongly associated with the enhanced bioactivities observed. Overall, this study confirms MAE as a highly efficient and sustainable technology for transforming pine bark waste into valuable antioxidant and antimicrobial extracts with potential applications in the food and pharmaceutical industries.

1. Introduction

Agricultural and forestry residues and by-products are valuable sources of biocomponents that hold industrial significance. The production of plant-derived antioxidant extracts has gained increasing research attention due to their applications in the food and pharmaceutical sectors [1,2]. Based on renewable natural resources, the forest industry is a significant productive sector that generates many discarded products yearly. These products primarily consist of processing by-products such as sawdust, wood chips, and bark, originating from sawmill and cellulose industries [3,4,5]. These discarded products have low economic value, although some of them contain a significative amount of biologically active compounds [6]. Thus, the forest industry holds substantial potential to upgrade these by-products into high-value products through their conversion and utilization. Pines are long-lived evergreen conifers characterized by resin production and predominantly monoecious reproduction [2]. Different species of pine trees possess varying compositions of bioactive compounds [7]. One of them is maritime pine (Pinus pinaster Ait.), which is distributed through the western Mediterranean basin and on the Atlantic coast of Portugal, Spain and France, and also in some North African countries, with the main objective being wood exploitation for various industrial purposes [5,8].

The worldwide abundance of pine bark, particularly from P. pinaster Ait. and P. pinea L., has generated significant interest in its utilization. In Portugal for instance, the bark from these species accounted for approximately 5000 and 600 tons in 2015, respectively [9,10]. The appeal of pine bark lies in its rich phytochemical content, affordability, and stability, making it an attractive by-product for various applications [11,12]. These favorable attributes collectively contribute to the attractiveness of employing this by-product.

Maritime pine bark is primarily composed of lignin, cellulose and hemicellulose [13], and is a substantial source of phenolic compounds, including flavonoids, phenolic acids, stilbenes, and tannins, particularly proanthocyanidins, among which procyanidins are prominent [14]. These extracts, abundant in flavonoids and condensed tannins, show promising health benefits and a potential to be used as a food preservative due to their antioxidant and antimicrobial properties [7,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Research indicates their use in enhancing the antioxidant capacity of food products like juices and dairy, although their broader application in food industries remains underexplored [20,22,23,24].

The extraction method used to obtain bioactive compounds from plants is a crucial factor that greatly influences their quality. This method, also known as a sample preparation technique, plays a significant role in determining the overall yield and outcome [25]. Despite their widespread use, conventional methods like maceration and Soxhlet extraction are laborious and require substantial solvent volumes [26]. This has driven a shift toward environmentally friendly and efficient “green extraction” techniques, such as MAE and UAE [27,28]. Nonetheless, even green techniques like UAE and MAE typically require biomass pre-processing (e.g., grinding and sieving), similar to conventional methods. The extraction method itself is a key determinant of the quality of the recovered bioactive compounds. As a fundamental component of sample preparation, it directly influences the yield and performance of all extraction approaches, regardless of the technology applied.

MAE is a rapid and efficient non-conventional technique that generates high pressure within the biomaterial, leading to cell disruption and enhanced solvent penetration [8], with high efficiency and applying shorter extraction times [29]. UAE uses a process known as sonication, which involves generating sound waves that produce cavitation bubbles, disrupting the cell walls and thereby releasing the contents of the cells [30,31,32]. Both methods prioritize the extraction efficiency and chemical stability of phenolic compounds, offering sustainable alternatives to conventional methods [29,33].

Therefore, the application of some of these extraction techniques could be a more sustainable alternative in the production of maritime pine bark extracts. For this reason, the aim of this work was to obtain two extracts rich in phenolic compounds by MAE and UAE using maritime pine bark by-products obtained in Portugal as raw material. In order to verify the bioactive potential of the two extracts, a chemical characterization of the phenolic compounds was carried out and their antioxidant, cytotoxic, anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial properties were analyzed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

Bark from maritime pine (Pinus pinaster Ait. subsp. atlantica) was collected in May 2021 from a certified experimental forest plantation located in Valença, Viana do Castelo, in northern Portugal. The bark was taken from 21-year-old trees at approximately 1.30 m above ground level by making a circular cut around the main trunk. After harvesting, the bark was repeatedly washed with distilled water to remove impurities such as dirt, lichens, and resin, and then dried at 40 °C for 48 h. The dried material was subsequently ground using an Analysette 3 PRO (Fritsch, Idar-Oberstein, Germany) and sieved for one minute at an amplitude of 0.2, yielding particles between 200 and 850 µm in diameter. The prepared samples were stored in hermetically sealed containers under controlled temperature, low-humidity, and light-protected conditions until further use.

2.2. Extraction

Two extraction techniques were applied: MAE and UAE. For MAE, 2.5 g of maritime pine bark was transferred to the extraction vessel and mixed with 50 mL of a water–ethanol solution (50:50, v/v), yielding a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:20 (w/v). The mixture was processed in an ETHOS X microwave extraction system equipped with an SK-12 medium-pressure rotor (Milestone, Bergamo, Italy) at 1600 W and 130 °C for 15 min. These optimized operating conditions for MAE were defined based on previous studies [34]. The vessels were kept under continuous agitation throughout the extraction process, as each extraction cell contained a magnetic stirrer operating inside the equipment.

The operating conditions for UAE were established based on preliminary unpublished studies conducted by the authors, supported by previous applications of UAE [35]. In this technique, 2.0 g of sample was combined with 100 mL of ethanol/water (80:20, v/v), giving a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:50 (w/v). The extraction was performed using an ultrasonic homogenizer (model CY-500, Optic Ivymen System, Barcelona, Spain) fitted with a titanium probe, operating at 20 kHz and 250 W (approximate intensity of 18.8 W/cm2 at the probe tip) for 5 min.

In both cases, the resulting extracts were filtered through paper and dried for yield determination. Following temperature adjustment to ambient conditions, the liquid phase containing the extractives was separated by vacuum filtration through Whatman® qualitative filter paper, Grade 1 (11 µm pore size; Whatman PLC, Little Chalfont, UK). In both cases, the resulting filtrates were then dried to determine the extraction yield.

2.3. Total Phenolic Content Determination

Total phenolic content was quantified using the Folin–Ciocalteu method according to Singleton and Rossi (1965) [36] and Ainsworth and Gillespie (2007) [37]. In brief, 100 µL of the extract was added to 200 µL of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent and gently agitated. Subsequently, 800 µL of 7% (w/v) sodium carbonate was added, and after a 2 h incubation, the absorbance of the resulting blue complex was measured at 765 nm with a Varioskan LUX Multi-mode Microplate Reader (Thermo Scientific, Vantaa, Finland). A reagent–water mixture served as the blank, and gallic acid was used to construct the calibration curve. Results were expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per gram of dry extract.

2.4. DPPH Free Radical Scavenging Effect

In low-light conditions, 0 µL of the methanolic diluted extract was added to a transparent 96-well microplate containing 200 µL of DPPH solution (60 µM, methanol). The mixture was incubated for 30 min, after which absorbance was measured at 520 nm using a Varioskan LUX Multimode Microplate Reader (Thermo Scientific, Vantaa, Finland). Spectrophotometer calibration was performed using methanol as the blank, while a DPPH solution prepared in absolute methanol without extract served as the control. Antioxidant activity was determined from the ability of pine bark extracts to scavenge DPPH radicals, with results expressed as IC50 values (mg/mL). Trolox (6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid) was used as the reference standard for calibration, prepared at a concentration of 800 µM.

The radical inhibition percentage was calculated from the reduction in DPPH absorbance, reflecting hydrogen-donor activity of antioxidants. The extent of discoloration indicated the radical scavenging capacity of the extracts. The DPPH assay is widely employed for evaluating antioxidant capacity due to its simplicity, sensitivity, and practicality [38].

2.5. ABTS Radical Cation Scavenging Effect

In dark conditions, 25 µL of the diluted extract stock solution (in methanol) was added to a clear 96-well microplate containing 200 µL of ABTS solution in methanol. The reaction mixture was incubated for 6 min prior to absorbance measurement at 735 nm, using a Varioskan LUX Multimode Microplate Reader (Thermo Scientific, Vantaa, Finland). Methanol served as the blank, while an ABTS solution with absolute methanol instead of extract was used as the control. Antioxidant activity was evaluated based on the ability of the pine bark extracts to scavenge ABTS radicals, with results expressed as IC50 values (mg/mL). A calibration curve was prepared using Trolox as the standard prepared at a concentration of 800 µM.

In this method, ABTS•+ radicals are generated by reacting ABTS with potassium persulfate, producing a blue/green chromophore. Upon addition of antioxidants, the radical cation is reduced in a concentration- and time-dependent manner, reflecting the antioxidant activity of the sample. The degree of decolorization, expressed as the inhibition percentage of ABTS•+, is compared with Trolox under identical conditions. This assay is widely applicable for assessing both water- and lipid-soluble antioxidants in pure compounds as well as complex extracts [39].

2.6. Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity

The antioxidant activity of the extracts was assessed using the oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) assay, carried out in a black 96-well microplate (Thermo Scientific™ Nunc MicroWell) following the procedure described by Coscueta et al. (2020) [40]. Briefly, the assay was performed at 40 °C in 75 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) with a final reaction volume of 200 µL. Each well contained fluorescein (70 nM), 2′-azobis (2-methylpropionamidine) dihydrochloride (AAPH, 12 mM), and either Trolox (1–8 µM) for calibration or the sample for determination. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was used as the control. Prior to the addition of AAPH, the mixture was pre-incubated for 10 min at 37 °C, after which AAPH was added quickly to initiate the reaction. Fluorescence kinetics were monitored at 30 s intervals for 90 min (181 cycles) on a Varioskan LUX Multimode Microplate Reader (Thermo Scientific, Vantaa, Finland), using excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 and 520 nm, respectively, under the control of SkanIt software (version 6.1.1.7). Antioxidant activity curves (fluorescence versus time) were normalized against the blank, and the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated using the trapezoidal rule. Results were expressed as IC50 values (mg/mL).

2.7. Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances (TBARS) Formation Inhibition

The thiobarbituric acid reactive substance (TBARS) inhibition assay was performed following the method of Pinela et al. (2012) [41]. Porcine (Sus scrofa domestica L.) brains were dissected and homogenized in cold 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) to obtain a 1:2 (w/v) brain tissue homogenate, which was then centrifuged at 3000× g for 10 min. An aliquot of the supernatant (0.1 mL) was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h with different extract concentrations (0.2 mL), FeSO4 (10 μM, 0.1 mL), and ascorbic acid (0.1 mM, 0.1 mL). The reaction was stopped by adding 28% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid (0.5 mL), followed by 2% (w/v) thiobarbituric acid (0.38 mL). The reaction mixture was incubated at 80 °C for 20 min, centrifuged at 3000× g for 10 min to remove protein precipitates, and the absorbance of the MDA–TBA complex in the supernatant was recorded at 532 nm using a Model 200 spectrophotometer (AnalytikJena, Jena, Germany). Antioxidant activity was expressed as IC50, defined as the extract concentration (µg/mL) required to inhibit 50% of TBARS formation.

2.8. Cellular Antioxidant Activity

Cellular antioxidant activity (CAA) was evaluated following the method of Wolfe & Liu (2007) [42]. Extracts were dissolved in water to obtain a stock solution of 8 mg/mL, which was then diluted with dichlorohydrofluorescein (DCFH; prepared in ethanol and diluted in 50 μM HBSS) to reach the desired working concentrations (500–2000 μg/mL).

RAW 264.7 murine macrophages were used as the cell model. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA) supplemented with 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 2 mM non-essential amino acids. Cultures were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified incubator (Heal Force CO2 Incubator, Shanghai Lishen Scientific Equipment Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) with 5% CO2. Cells were detached using a scraper, centrifuged (1200 rpm, 5 min), and after adjustment to 70,000 cells/mL, 300 µL of the cell suspension was seeded into black, clear-bottom 96-well plates (SPL Lifesciences, Pocheon-si, Republic of Korea) and incubated until a confluent monolayer was formed. After incubation, the medium was discarded, and cells were washed twice with HBSS (100 µL). They were then treated with 200 µL of extract at different concentrations (500–2000 μg/mL) and incubated for 1 h. Following treatment, cells were washed twice with HBSS (100 µL) before adding 100 µL of AAPH solution (600 μM). Fluorescence was recorded every 5 min for 1 h using a Synergy H1 microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA) with excitation at 530 nm and emission at 470 nm.

Negative controls consisted of DCFH with culture medium, while quercetin was used as a positive control. Results were presented as the percentage reduction in reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation at the maximum extract concentration tested.

2.9. Oxidative Haemolysis Inhibition Assay (OxHLIA)

The oxidative hemolysis inhibition assay (OxHLIA) was carried out according to the method described by Lockowandt et al. (2019) [43]. Sheep erythrocyte suspension (200 μL, 2.8% v/v in PBS) was mixed with 400 μL of extract solution (0.31–2.5 μg/mL in PBS), PBS alone (negative control), or water (complete hemolysis) in flat-bottom 48-well plates. Trolox was used as the positive control. Following a 10 min pre-incubation at 37 °C with shaking, 200 μL of AAPH (160 mM in PBS) was added. Optical density was immediately measured at 690 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, ELX800). The plate was then incubated under the same conditions, with absorbance recorded approximately every 10 min at 690 nm until complete hemolysis occurred. Data were analyzed, and results were expressed as IC50 values (μg/mL) for a Δt of 60 min.

2.10. Antimicrobial Activity

For this assay, the extracts were lyophilized under vacuum for 48 h using an Alpha 1-2 LDplus freeze-dryer (Christ, Osterode am Harz, Germany) and subsequently dissolved in DMSO. Both MAE and UAE extracts were tested for antimicrobial activity at concentrations of 30, 50, and 65 mg/mL, following the procedures described by Barros et al. (2020) [5] and Mármol et al. (2022) [44]. Antimicrobial activity was evaluated using the disk diffusion method in accordance with CLSI 2012 guidelines [45]. Sterile paper disks (Oxoid, England; 6 mm diameter) were impregnated with 10 μL of extract or control (DMSO as negative control, bleach coded as Lx as positive control).

Bacterial strains tested included Bacillus cereus (NCTC 11,143 and ATCC 11778), Clostridium perfringens ATCC 13124, Escherichia coli ATCC 8739, Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 13932, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923, and Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis ATCC 25928. Cultures (0.5 McFarland standard) were first inoculated onto Columbia Agar with 5% sheep blood (COS, Biomérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France), then spread with a cotton swab onto Mueller-Hinton Agar (MHA, Oxoid, England). After drying for 3–5 min, disks were placed on the inoculated plates using flame-sterilized tweezers. Plates were left to stand for 15 min, inverted, and incubated at 37 °C for 22 h. For Clostridium perfringens, the plates were incubated under anaerobic conditions using an anaerobic jar with gas-generating sachets to maintain an oxygen-free environment.

Zone diameters were measured in millimeters (mm) using ImageJ v1.4 software [46]. and expressed as the mean of three inhibition halos. The bacterial strains were chosen as representative Gram-positive and Gram-negative foodborne pathogens and spoilage bacteria.

2.11. Antiproliferative Activity

The antiproliferative activity was evaluated following the method of Mandim et al. (2019) [47]. Human tumor cell lines used included AGS (gastric adenocarcinoma), Caco-2 (colorectal adenocarcinoma), MCF-7 (breast adenocarcinoma), and NCI-H460 (lung carcinoma). All cell lines were obtained from the European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures (ECACC). Non-tumor cell lines were also included, namely Vero (African green monkey kidney) and PLP2 (primary pig liver culture), established according to Mandim et al. (2019) [48].

Tumor and PLP2 cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA) supplemented as described in Section 2.8, while Vero cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, glutamine, and antibiotics. All cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and used at 70–80% confluence.

Stock solutions of the extracts were prepared by dissolving 8 mg of each extract in 1 mL of water to yield a concentration of 8 mg/mL. Serial dilutions were then prepared to obtain the test concentrations (0.125–8 mg/mL). For the assay, 10 μL of each extract dilution was incubated with 190 μL of the respective cell suspension in 96-well plates for 72 h. Cell density was 1.0 × 104 cells/well for all lines except Vero, which was plated at 1.9 × 104 cells/well.

Following incubation, cells were fixed with cold 10% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid (TCA, 100 μL) for 1 h at 4 °C, washed with water, and dried. Sulforhodamine B (SRB, 0.057% w/v, 100 μL) was then added and allowed to stain for 30 min at room temperature. Plates were washed three times with 1% (v/v) acetic acid and dried to remove unbound dye. Bound SRB was solubilized in 200 μL of 10 mM Tris, and absorbance was measured at 540 nm using a Synergy H1 microplate reader (Biotek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA).

Results were expressed as the extract concentration required to inhibit 50% of cell growth (GI50, μg/mL). Cells without extract served as negative controls, while dexamethasone was used as a positive control.

2.12. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

The anti-inflammatory activity of the extracts was assessed following the procedure described by Sobral et al. (2016) [49]. Stock solutions (8 mg/mL) were prepared by dissolving the extracts in water, and serial dilutions were then made to obtain test concentrations ranging from 0.125 to 8 mg/mL. RAW 264.7 murine macrophages, maintained as described above, were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 5.0 × 105 cells/mL and incubated for 24 h under standard conditions to allow for cell attachment and proliferation.

Following this, cells were treated with various concentrations of the extracts (15 μL, corresponding to 6.25–400 μg/mL) and incubated for 1 h. Inflammation was induced by adding 30 μL of lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 1 mg/mL), followed by an additional 24 h incubation. Nitric oxide production was determined using the Griess reagent system (containing nitrophenamide, ethylenediamine, and nitrite solutions), along with a sodium nitrite calibration curve (1.6–100 mM) prepared in a 96-well plate. Absorbance was measured at 540 nm using a Synergy H1 microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA). Nitric oxide concentrations were determined from the calibration curve (y = 0.0068x + 0.0951, R2 = 0.98).

Results were expressed as the extract concentration required to inhibit 50% of nitric oxide production (IC50, μg/mL), calculated from the dose–response curve of percent inhibition versus extract concentration. Dexamethasone was used as a positive control, while cells without LPS served as the negative control.

2.13. Analysis of Phenolic Compounds

Phenolic compounds were analyzed following the method of Bessada et al. (2016) [50]. Extracts were dissolved in 80% ethanol (v/v) to a final concentration of 10 mg/mL and filtered through 0.22 µm disposable filters. Analyses were conducted using a Dionex Ultimate 3000 ultra-performance liquid chromatography system (UPLC) coupled to a diode array detector and an electrospray ionization mass spectrometer (HPLC-DAD-ESI/MS) operating in negative mode (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA). Separation was performed on a Waters Spherisorb S3 ODS-2 reverse-phase C18 column (4.6 × 150 mm, 3 µm), using a mobile phase composed of 0.1% formic acid in water and acetonitrile under a gradient elution program. Detection was carried out at 280, 320, and 370 nm.

Data acquisition and processing were performed using the Xcalibur® 1.6 software (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA). Compounds were identified by comparing their UV–Vis and mass spectra with literature data and, when available, authentic standards (Extrasynthèse, Genay, France). For compounds lacking authentic standards, quantification was achieved using calibration curves of structurally analogous phenolics within the same chemical group. Quantification of identified compounds was based on authentic standard calibration curves for (+)-catechin (y = 13304x − 7786.3, R2 = 0.9994; LOD = 0.15 μg/mL; LOQ = 0.78 μg/mL) and taxifolin (y = 39133x − 13647, R2 = 0.999; LOD = 0.67 μg/mL; LOQ = 2.02 μg/mL).

2.14. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using TIBCO Statistica Ultimate Academic 14.0.0 for Windows (TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA). All experiments were performed in triplicate for each replicate, and results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Data were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA), and differences between means were evaluated using Tukey’s HSD test, with significance set at p < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Extraction Yield, TPC and Antioxidant Activities

The efficiency of extracting antioxidant compounds from plant material is largely influenced by the specific conditions applied during the liquid–solid extraction process [32]. The extraction yields of the two extraction methodologies, MAE and UAE, are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Extraction yield, Total Phenolics and Antioxidant activities of Minho maritime pine bark hydroethanolic extracts obtained by Microwave- and Ultrasound-assisted extractions.

A highly statistically significant difference was observed between the two methods (p < 0.001). MAE yielded a greater quantity of extract at 11.13 g extract/100g pine bark, in contrast to UAE, more than three times lower. While both methods disrupt the plant matrix, MAE showed higher efficiency than UAE under the conditions tested, likely due to the role of intrinsic plant water as a microwave energy transfer medium, which favors this specific matrix (pine bark). This advantage of MAE over UAE in terms of extraction efficiency is supported by previous research, which found a greater extraction yield with MAE when dealing with the outer bark of yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis Britton) [51]. The reason for the distinct MAE yield compared to UAE can be attributed to the particular sample tissue composition together with the distinct operational mechanisms of extraction [52,53,54]. MAE applies microwave radiation to uniformly heat both the solvent and the sample matrix throughout the entire volume. In essence, it functions by elevating the temperature of moisture content, specifically water molecules, present within plant cells, thereby making them the focal point of microwave heating. This swift elevation in temperature within the plant matrix results in an augmented intracellular pressure, disrupting the cell walls and facilitating the release of internal cellular components. Simultaneously, the rise in solvent temperature expedites the diffusion process [52,53,54]. MAE stands out for its remarkable efficiency in both extraction and time, while also demanding minimal quantities of solvent [55]. Conversely, the UAE technique relies on the phenomenon of cavitation induced by ultrasound as it traverses through the solvent, thereby enhancing mass transfer and fostering a strong interaction between the solvent and plant tissues [30,54,56]. This process results in the generation of cavitation bubbles near the surfaces of plant tissues. Upon the collapse of these bubbles, they disrupt the integrity of the cell walls, expanding the contact area between the matrix and solvent. Consequently, this increased permeability of the cell wall enhances the diffusion process, favoring the extraction yield [30,54,56].

The extraction of phenolic compounds using MAE proved to be more efficient, yielding 833 mg GAE/g DM extract, in contrast to UAE, which yielded 514 mg GAE/g DM extract, as indicated in Table 1. This statistically significant difference (p = 0.005) can be attributed to the presence of radicals generated during the UAE process, which may have caused the degradation of phenolic compounds due to their inherent antioxidant properties [57]. In the study of Diouf et al. (2009) [51], however, no significant differences were found between these two extraction methods regarding TPC. The MAE extracts obtained in the present study showed higher TPC compared to the reported in previous studies with maritime pine bark using MAE [8] and with others studies using other extraction procedures and hydroethanolic solvents: Ferreira-Santos et al. (2020) [58] found a TPC concentration of 674.5 ± 23 mg GAE/g; Simões et al. (2021) [59] presented a TPC average value of 439.8 mg GAE/g extract; Ramos et al. (2022) [10] obtained a total phenolic content of 539 mg GAE/g extract. Sládková et al. (2016) [60] conducted a study in another species bark (P. abies) using MAE and reported a maximum TPC of 321.1 mg GAE/100 g of dry bark, lower than the obtained in the present study.

To evaluate the antioxidant properties of pine bark extracts DPPH, ABTS, ORAC, TBARS, CAA, and OxHLIA assays were employed. TBARS assay was employed to evaluate the antioxidant activity of pine bark extracts in a biologically relevant system, specifically their ability to inhibit lipid peroxidation. Lipid peroxidation is a key process in oxidative stress, and plant-derived phenolic compounds are known to prevent or delay this process by scavenging reactive species or chelating pro-oxidant metal ions. TBARS assay provides complementary information to the radical scavenging assays (DPPH, ABTS, ORAC) by assessing the protective effect of the extracts in a lipid matrix, which is relevant for potential food, cosmetic, or pharmaceutical applications. The results were expressed as IC50 values or inhibition percentage, depending on the method (see Table 1 above). IC50 represents the concentration of extract required to inhibit 50% of the free radical activity in the assay. Lower IC50 values indicate stronger radical scavenging activity. In contrast, for the Cellular Antioxidant Activity (CAA) assay, higher inhibition percentages correspond to greater antioxidant activity of the extract.

The MAE pine bark extract obtained displayed higher antioxidant properties compared to the UAE extract regarding the DPPH and ABTS assays, with, respectively, an IC50 value of 0.176 mg/mL and 0.333 ± 0.004 mg/mL. The ethanol-water extracts from P. pinaster and P. pinea phloems studied by Simões et al. (2021) [59] showed even higher antioxidant activity able to effectively reduce the DPPH with IC50 values ranging from 1.2 μg/mL to 1.8 μg/mL. Pinus pinaster extracts obtained in the study by Ferreira-Santos et al. (2019) [61], presented values for the DPPH ranging from 165.07 to 237.27 μmol total trolox equivalents/g of bark and for ABTS assay ranging from 394.28 to 918.49 μmol total trolox equivalents/g of bark.

However, the opposite occurred in TBARS assay, where the IC50 value of the extract obtained by UAE was lower than by MAE revealing the higher ability of UAE method. The highlight in this case is that both IC50 values are much lower than the obtained in the other used methodologies, indicating both extracts had strong capacity to inhibit lipid peroxidation [62]. The findings indicated that the antioxidant activity of pine bark extract, as determined in the TBARS assay, was higher for both extracts obtained through MAE (IC50 of 1.74 µg/mL) and UAE (IC50 of 0.969 µg/mL) compared to the Morus nigra fruit extract (IC50 of 39 ± 2 µg/mL) reported in the study by Vega et al. (2021) [63].

Also, in the CAA method, the extract obtained by UAE showed a higher percentage of inhibition (69%) and, therefore, a higher antioxidant activity. In this case, the percentages correspond to the maximum concentration tested (2000 μg/mL), so that neither of the two extracts showed outstanding activity in the CAA method. Nevertheless, the CAA results from this investigation revealed a superior antioxidant capacity compared to the aqueous extract of Solanum mammosum L. leaves obtained by Pilaquinga et al. (2021) [64], where the CAA percentage obtained was 14.7%. Regarding the ORAC and OxHLIA tests, there were no significant differences in the antioxidant abilities of the two extraction methods. Concerning the OxHLIA assay, the extracts obtained by both methods exhibited a notable antioxidant capacity by delaying oxidative hemolysis for 60 min. This performance was noteworthy, particularly when compared to the Morus nigra fruit extract (IC50 of 253 µg/mL) reported in the study by Vega et al. (2021) [63]. The research carried out by Vieira et al. (2020) [65] showed results of antioxidant activity for the hydroethanolic extract of Juglans regia L. in the TBARS assay of IC50 = 101 μg/mL and in the OxHLIA assay of IC50 = 80 μg/mL, results significantly lower than those found in this study. Therefore, considering all methodologies applied, the extract obtained by MAE has, in general, better antioxidant properties than the extract obtained by UAE.

3.2. Antiproliferative and Anti-Inflammatory Properties

As shown in Table 2, the extraction method influenced the cell lines proliferation, as statistically significant differences were observed in all cell lines, except Caco2. In the three tumor cell lines for which statistically significant differences were observed (AGS, MCF-7, and NCI-H460), the GI50 values were lower in the case of the extract obtained by UAE, so its anti-proliferative potential is higher. In both cases, higher activity was observed in AGS and NCI-H460, with GI50 values below 200 μg/mL. In contrast, the same was not observed in non-tumor cell lines. In the case of Vero, the extract obtained by UAE showed a higher GI50 value (77.4 > 54.4 μg/mL), while in the case of PLP2, the MAE extract showed a higher GI50 value (173.9 > 120.6 μg/mL). As these are non-tumor cells, the extracts should ideally not show antiproliferative activity against these cell lines. As the GI50 values of both extracts in tumor cell lines are lower than the GI50 values in non-tumor cell lines, the extracts are not useful for this purpose because they will be cytotoxic to non-tumor cell lines if used at concentrations with anti-proliferative activity in tumor cell lines.

Table 2.

Antiproliferative and Anti-inflammatory effects of Minho maritime pine bark hydroethanolic extracts obtained by Microwave- and Ultrasound-assisted extractions.

Regarding the anti-inflammatory activity, similar results were observed. In this case, neither extract is suitable for this purpose because none of them showed quantifiable anti-inflammatory activity, as can be seen in Table 2.

Similar results were reported by Oliveira et al. (2021) [66] and Fischer et al. (2022) [67] for extracts obtained from Paraná pine (Araucaria angustifolia (Bertol.) Kuntze) seed residues and for phenolic-rich extracts isolated from the sterile bracts of Araucaria angustifolia, respectively. In both studies, no anti-inflammatory activity was detected within the tested concentration range, which extended up to 400 μg/mL.

3.3. Antibacterial Activity

The pine bark extracts produced inhibition zones ranging from 9 to 18 mm against Gram-positive bacteria, as shown in Table 3. Extracts obtained via UAE generally produced larger inhibition zones compared to those obtained by MAE. Among the tested bacteria, only Bacillus cereus, Staphylococcus aureus, and Clostridium perfringens were susceptible to the maritime pine bark extracts from both extraction methods. In a previous study, Barros et al. (2020) [5] reported inhibition zones of 7–17 mm for maritime pine bark extracts against Gram-positive bacteria.

Table 3.

Antibacterial activity of hydroethanolic Minho maritime pine bark of extracts obtained by Microwave- and Ultrasound-assisted extraction determined by the disk diffusion method in MHA.

As noted by Kumar & Brooks (2018) [68], Gram-positive bacteria are typically more sensitive than Gram-negative bacteria. This difference is largely due to the outer double-layer membrane, highly hydrophilic lipopolysaccharides, and the distinct periplasmic space characteristic of Gram-negative bacteria. Similarly, Ramos et al. (2022) [10] and Nisca et al. (2021) [69] observed that pine extracts more effectively inactivated Gram-positive bacteria compared to Gram-negative species.

These results indicate strong antibacterial activity specifically against Gram-positive bacteria. At a concentration of 65 mg/mL, the UAE extract produced the largest inhibition zone against C. perfringens, consistent with the findings of Mármol et al. (2022) [44]. Conversely, Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli, and Salmonella Enteritidis were the most resistant strains, with neither extract showing activity against the Gram-negative bacteria tested.

3.4. Phenolic Compound Profile

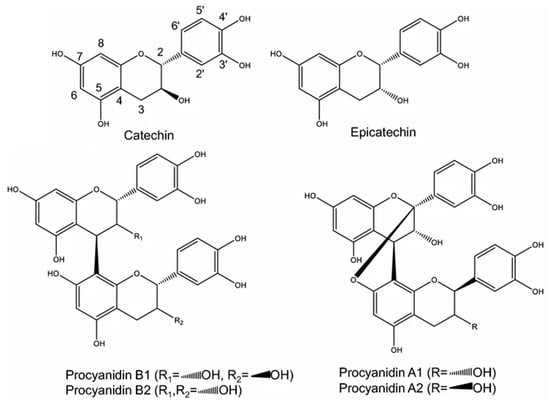

The LC-MS/MS analysis of pine bark extracts obtained by MAE and UAE, presented in Table 4, reveals a complex profile of phenolic compounds, predominantly procyanidins. The fragmentation patterns observed provide insights into the structural characteristics of these compounds. B-type procyanidin dimers (Peaks 1, 10) showed a parent ion [M-H]- at m/z 577, fragmenting to m/z 559, 467, 451, 425, 407, and 289. The presence of fragment ions at m/z 451 and 407 indicates the loss of C4-C8 or C4-C6 linked flavan-3-ol units. For (+)-catechin and (−)-epicatechin (peaks 2, 7), displaying a molecular ion at m/z 289, the main fragment ions at m/z 245 and 205 are indicative of the flavan-3-ol structure, typical of catechins. B-type procyanidin trimers (peaks 3, 6) exhibited a parent ion [M-H]- at m/z 865, with notable fragments at m/z 577 and 289, appearing to indicate the sequential loss of (+)-catechin or (−)-epicatechin units. For B-type procyanidin tetramers (peaks 4, 8, 9, 17), with a molecular ion at m/z 1153, the fragmentation to m/z 865 and 577 suggests the presence of linked catechin/epicatechin units. A-type procyanidin dimers (peaks 5, 13), with a parent ion at m/z 575, showed a unique fragmentation pattern with ions at m/z 423 and 407, indicating the presence of A-type linkages between flavan-3-ol units. For A-type procyanidin tetramers (peaks 11, 14, 15), the molecular ion at m/z 1151 and fragments at m/z 1009, 863, and 575 suggest the presence of A-type linkages in these larger procyanidin structures. Taxifolin-7-O-hexoside (peak 12) is tentatively identified by its molecular ion at m/z 465 and characteristic fragments at m/z 303 and 285, indicating the presence of a flavanonol glycoside. Single A-type linked procyanidin trimers (peaks 16, 18), with a parent ion at m/z 863, showed fragmentation to m/z 575, indicating the cleavage of A-type linkages. Figure 1 illustrates the chemical structures of key phenolic compounds identified in the pine bark extracts, showcasing the structural nuances of A-type and B-type procyanidins, as well as the fundamental units of catechin and epicatechin. This visual representation aids in understanding the molecular basis for their bioactivity and fragmentation patterns observed in our analysis.

Table 4.

Retention time (Rt), maximum absorption wavelengths in the visible region (λmax), mass spectral data, relative fragment ion abundances, and the tentative identification of phenolic compounds in maritime pine bark extracts.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of phenolic compounds found in pine bark extracts. This figure displays the molecular structure of A-type and B-type dimeric procyanidins, along with (+)-catechin and (−)-epicatechin.

Regarding the quantification of the phenolic compounds found in the maritime pine bark extracts obtained by MAE and UAE are listed in Table 5. The most abundant compound was B-type procyanidin trimer I, with a content of 73.30 mg/g of extract in the MAE extract and 26.79 mg/g of extract in the UAE extract. Both extracts also contained another compound of this type, B-type procyanidin trimer I, with a content of less than 4 mg/g extract. Procyanidins are proanthocyanidins formed from (+)-catechin and (−)-epicatechin [14]. Precisely these two compounds are also present in the extracts in isolated form. (+)-Catechin is the second most abundant phenolic compound in the MAE extract (48.88 mg/g of extract), but its content in the UAE extract was 17 times lower (2.86 mg/g of extract). The epicatechin content was not so different in the two extracts, with the MAE extract containing 6.63 mg/g of extract and the UAE extract 3.27 mg/g of extract, approximately half. Another abundant compound in these extracts was B-type procyanidin dimer I, ranking second among phenolic compounds in abundance in the UAE extract at 10.95 mg/g of extract. In the MAE extract its content was higher, 18.57 mg/g of extract.

Table 5.

Phenolic compound profile of Minho maritime pine bark hydroethanolic extracts obtained by Microwave- and Ultrasound-assisted extraction.

Out of the 18 compounds identified, 15 were procyanidins. In total terms, B-type procyanidins were more abundant than A-type procyanidins. In both cases, the MAE extract had a higher content of A-type (56.92 mg/g of extract) and B-type (117.41 mg/g of extract) procyanidins than the UAE extract (22.94 and 56.92 mg/g of extract, respectively). In addition to these compounds, a flavanonol, taxifolin-7-O-hexoside, was found with a reduced content in both cases and less than 1 mg/g of extract.

The total content of phenolic compounds in the extract obtained by MAE was 230.0 mg/g extract, while the extract obtained by UAE was 86.95 mg/g extract. These data are in line with the results of total phenolic compounds discussed above (Table 1), as the MAE extract had a higher content than the UAE extract.

Although there are several studies on phenolic compounds in maritime pine bark, data on procyanidin content are scarce. Chupin et al. (2015) [8] reported the total content of condensed tannins as catechin equivalents. They studied two extraction methods, one in water with 1% NaOH, 0.25% Na2SO3, and 0.25% NaHSO3 and the other in 80% ethanol using MAE, obtaining a much higher result in the second case with a total condensed tannins content of 402.5 mg catechin equivalents/g extract, more than 17 times higher than the other extract. Simões et al. (2021) [59] reported the total content of condensed tannins in the extract too, with values ranging from 84.4 to 125.1 mg catechin equivalents/g of extract. In the case of the extract obtained by UAE, the sum of A-type and B-type procyanidins is less than the minimum value of the range defined by Simões et al. (2021) [59], while in the extract obtained by MAE, the sum of both values exceeds their maximum value, so the results of Simões et al. (2021) [59] are within the range defined by the results of this study. In contrast, Chupin’s (2015) [8] values lie outside the two ranges.

Gascón et al. (2018) [70] reported the content of two specific procyanidins in bark, so it is not possible to compare the results directly with ours, which are expressed in extract, but in relative terms. The most abundant was procyanidin B2, with a content of 42 μg/g bark, while the content of procyanidin B1 was much lower, 5.3 μg/g bark. Both procyanidins are B-type dimers with C4 → C8 bonds, B1 of (+)-catechin and (−)-epicatechin and B2 of (−)-epicatechin [14]. In this study, two B-type dimers were identified, which are likely to correspond to procyanidins B1 and B2. The compound as such cannot be known due to methodological limitations, as described by Lin et al. (2014) [71]. The first B-type dimer was present in both extracts and with a higher content, so it is possible that it is procyanidin B2, while the second was found only in the extract obtained by MAE and in smaller quantities, and it may correspond to procyanidin B1. The structural characteristics of procyanidins in the maritime pine bark extracts obtained in this study may facilitate specific interactions with biomolecules such as proteins and nucleic acids. These interactions, though not directly assessed this investigation, could influence the observed bioactivities, as suggested by similar studies in the field [72,73]. For instance, research by Dai et al., (2019) [74] has indicated that such structural configurations can enhance antioxidant and antimicrobial activities. Therefore, the bioactivities noted in the performed assays might be partly attributed to these molecular interactions, warranting further investigation to elucidate these mechanisms. Chupin et al. (2013) [75] carried out a thiolysis treatment to depolymerise the procyanidins and release the catechin and epicatechin subunits, and the content of (+)-catechin was higher than the content of (−)-epicatechin in all the extracts they analyzed. Since their results were after thiolysis, it is not known how much (+)-catechin and (−)-epicatechin were free and how much were polymerized.

Regarding the free (+)-catechin and (−)-epicatechin content, the works of Ferreira-Santos et al. (2019, 2020) [58,61] are useful. However, direct comparisons of the results cannot be made because they expressed the results per L of liquid extract. The most remarkable aspect of their results is that they could not quantify (−)-epicatechin. In the extract obtained in this research by MAE there is a large difference between (+)-catechin and (−)-epicatechin content, with (+)-catechin content being much higher, so it could correspond to a similar situation. However, the extract obtained in this investigation by UAE showed more (−)-epicatechin than (+)-catechin, although it is true that the content of both molecules was much lower than the (+)-catechin content in the extract obtained by MAE. Ferreira-Santos et al. (2020) [58] studied the effect of the percentage of ethanol in a hydroethanolic mixture extraction and the (+)-catechin content exceeded 100 mg/L of extract with 30, 50, 70 and 90% ethanol, while (+)-catechin could not be quantified in the aqueous extract without ethanol. However, in a previous study [61] comparing extraction with water and 50% ethanol, they were able to quantify (+)-catechin, but its content was significatively lower. Ferreira-Santos et al. (2019) [61] investigated the effect of ohmic heating on the extraction of phenolic compounds and reported that this technique significantly increased extraction yields compared to conventional methods.

The application of ultrasound in the extraction of phenolic compounds remains limited. In one of the few studies available [35], ultrasound-assisted extraction of polyphenols from maritime pine residues yielded an extract with strong antioxidant and antimicrobial activity. According to Ferreira-Santos et al. (2020) [76], this extraction technique has been used with other species of the genus Pinus with good results, as well as MAE, which has been previously used on this type of sample, as mentioned above. When comparing the results of the two extraction methods, the MAE method showed higher values than the UAE method in terms of total phenolic compounds. It is true that the extraction solvent also has an influence and that in this study different ethanol concentrations were used in the two types of extraction. However, considering (+)-catechin as the reference compound, according to Ferreira-Santos et a. (2020) [58], there are no statistically significant differences in its content in the extracts obtained with 50, 70 and 90% ethanol, so the differences observed in the present study must be mainly due to the extraction method and not to the concentration of the solvent. Therefore, under these conditions, MAE is a more appropriate extraction method than UAE for obtaining phenolic-rich extracts from maritime pine bark.

4. Conclusions

In this study, MAE was shown to be more efficient than UAE for the valorization of Pinus pinaster bark under the tested conditions. MAE achieved significantly higher extraction yields (11.13 vs. 3.47 g extract/100g bark), total phenolic content (833 vs. 514 mg GAE/g), and enhanced antioxidant activity in most assays tested. The phenolic profile analysis revealed that MAE extracted 230.0 mg/g of total phenolic compounds compared to 86.95 mg/g for UAE, confirming that MAE more effectively extracts a complex mixture of procyanidins, which are strongly linked to the observed bioactivities. The significant antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive pathogens underscores the potential of these extracts, particularly from MAE, as natural preservatives in the food industry or as active ingredients in cosmetic and pharmaceutical formulations. The superior performance of MAE can be attributed to its enhanced cellular disruption mechanism through microwave heating of intracellular water, leading to increased mass transfer rates. These findings support the implementation of MAE as a sustainable and efficient technology for valorizing forestry waste into high-value bioactive products. However, further research including pilot-scale studies and energy efficiency analyses would be needed to determine the feasibility of scaling up either technology. The research contributes to the development of green extraction processes that can transform low-value agricultural residues into economically viable bio-based products. Also, future developments should focus on process optimization, scale-up considerations, and techno-economic feasibility analysis for industrial implementation of these sustainable extraction technologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and investigation, D.B., J.I.A.-E., É.F., L.B. and M.V.-V.; methodology, D.B., J.I.A.-E., É.F., L.B. and M.V.-V.; formal analysis, D.B., J.I.A.-E. and É.F.; writing—original draft preparation, D.B., J.I.A.-E., T.C.F., C.P., J.A.V., R.P.-P., É.F., P.P. and J.S.; writing—review and editing, D.B., J.I.A.-E., R.P.-P., É.F., L.B. and M.V.-V.; resources, L.B. and M.V.-V.; supervision, L.B. and M.V.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT, Portugal) through national funds FCT/MCTES (PIDDAC) to CISAS, UIDB/05937/2025 (DOI: 10.54499/UID/05937/2025, as well as to CIMO, UID/00690/2025 (10.54499/UID/00690/2025) and UID/PRR/00690/2025 (10.54499/UID/PRR/00690/2025); and SusTEC, LA/P/0007/2020 (DOI: 10.54499/LA/P/0007/2020).

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. Restrictions apply to the availability of raw data due to institutional and ethical considerations.

Acknowledgments

D.B. thanks FCT—SFRH/BD/146720/2019 PhD Scholarships co-financed by European Social Fund (ESF) through the Programa Operacional Regional Norte 2020 (DOI: 10.54499/SFRH/BD/146720/2019); J.I.A.-E. thanks the Ministry of Universities (Spain) and the European Union-Next Generation EU Funds for the Margarita Salas grant (UCM/572725/2021).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Conde, E.; Díaz-Reinoso, B.; Moure, A.; Hemming, J.; Willför, S.; Domínguez, H.; Parajó, J.C. Extraction of Phenolic and Lipophilic Compounds from Pinus Pinaster Knots and Stemwood by Supercritical CO2. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2013, 81, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, T.; Choi, Y.-W.; Kim, Y.-K. Impact of Different Extraction Solvents on Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Potential of Pinus densiflora Bark Extract. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 3520675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ku, C.S.; Jang, J.P.; Mun, S.P. Exploitation of polyphenol-rich pine barks for potent antioxidant activity. J. Wood Sci. 2007, 53, 524–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspé, E.; Fernández, K. The effect of different extraction techniques on extraction yield, total phenolic, and anti-radical capacity of extracts from Pinus radiata Bark. Ind. Crops Prod. 2011, 34, 838–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, D.; Vieito, C.; Santos, J.; Ramos, C.; Velho, M.V. Inhibitory Effects of Pinus Pinaster Aiton Subsp. Atlantica Bark Extracts Against Known Food Pathogens. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2020, 79, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspé, E.; Fernández, K. Comparison of phenolic extracts obtained of Pinus radiata bark from pulp and paper industry and sawmill industry. Maderas Cienc. Tecnol. 2011, 13, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziedziński, M.; Kobus-Cisowska, J.; Stachowiak, B. Pinus Species as Prospective Reserves of Bioactive Compounds with Potential Use in Functional Food—Current State of Knowledge. Plants 2021, 10, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chupin, L.; Maunu, S.L.; Reynaud, S.; Pizzi, A.; Charrier, B.; Charrier-El Bouhtoury, F. Microwave assisted extraction of maritime pine (Pinus pinaster) bark: Impact of particle size and characterization. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 65, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICNF. 6º Inventário Florestal Nacional—IFN6. Available online: https://www.agroportal.pt/6o-inventario-florestal-nacional/ (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- Ramos, P.A.B.; Pereira, C.; Gomes, A.P.; Neto, R.T.; Almeida, A.; Santos, S.A.O.; Silva, A.M.S.; Silvestre, A.J.D. Chemical Characterisation, Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities of Pinus pinaster Ait. and Pinus pinea L. Bark Polar Extracts: Prospecting Forestry By-Products as Renewable Sources of Bioactive Compounds. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, M.E.M.; Santos, R.M.S.; Seabra, I.J.; Facanali, R.; Marques, M.O.M.; de Sousa, H.C. Fractioned SFE of antioxidants from maritime pine bark. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2008, 47, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabra, I.J.; Dias, A.M.A.; Braga, M.E.M.; de Sousa, H.C. High pressure solvent extraction of maritime pine bark: Study of fractionation, solvent flow rate and solvent composition. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2012, 62, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, D.; Fernandes, É.; Jesus, M.; Barros, L.; Alonso-Esteban, J.I.; Pires, P.; Vaz Velho, M. The Chemical Characterisation of the Maritime Pine Bark Cultivated in Northern Portugal. Plants 2023, 12, 3940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Esteban, J.I.; Carocho, M.; Barros, D.; Velho, M.V.; Heleno, S.; Barros, L. Chemical composition and industrial applications of Maritime pine (Pinus pinaster Ait.) bark and other non-wood parts. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technol. 2022, 21, 583–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Grün, I.U.; Mustapha, A. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of natural extracts in vitro and in ground beef. J. Food Prot. 2004, 67, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, J.; Grün, I.; Mustapha, A. Effects of plant extracts on microbial growth, color change, and lipid oxidation in cooked beef. Food Microbiol. 2007, 24, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hameş-Kocabaş, E.E.; Çeliktaş, Ö.Y.; İşleten, M.; Sukan, F.V. Antimicrobial activity of pine bark extract and assessment of potential application in cooked red meat. GIDA 2008, 33, 123–127. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggeri, S.; Straniero, R.; Pacifico, S.; Aguzzi, A.; Virgili, F. French Marine Bark Extract Pycnogenol as a Possible Enrichment Ingredient for Yogurt. J. Dairy Sci. 2008, 91, 4484–4491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iglesias, J.; Pazos, M.; Lois, S.; Medina, I. Contribution of Galloylation and Polymerization to the Antioxidant Activity of Polyphenols in Fish Lipid Systems. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 7423–7431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesil Celiktas, O.; Isleten, M.; Vardar-Sukan, F.; Oyku Cetin, E. In vitro release kinetics of pine bark extract enriched orange juice and the shelf stability. Br. Food J. 2010, 112, 1063–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raitanen, J.E.; Järvenpää, E.; Korpinen, R.; Mäkinen, S.; Hellström, J.; Kilpeläinen, P.; Liimatainen, J.; Ora, A.; Tupasela, T.; Jyske, T. Tannins of Conifer Bark as Nordic Piquancy-Sustainable Preservative and Aroma? Molecules 2020, 25, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frontela-Saseta, C.; López-Nicolás, R.; González-Bermúdez, C.A.; Peso-Echarri, P.; Ros-Berruezo, G.; Martínez-Graciá, C.; Canali, R.; Virgili, F. Evaluation of Antioxidant Activity and Antiproliferative Effect of Fruit Juices Enriched with Pycnogenol® in Colon Carcinoma Cells. The Effect of In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion. Phytother. Res. 2011, 25, 1870–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Nicolás, R.; González-Bermúdez, C.A.; Ros-Berruezo, G.; Frontela-Saseta, C. Influence of in vitro gastrointestinal digestion of fruit juices enriched with pine bark extract on intestinal microflora. Food Chem. 2014, 157, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semeniuc, C.A.; Rotar, A.; Stan, L.; Pop, C.R.; Socaci, S.; Mireşan, V.; Muste, S. Characterization of pine bud syrup and its effect on physicochemical and sensory properties of kefir. CyTA J. Food 2016, 14, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.W.; Lin, L.G.; Ye, W.C. Techniques for extraction and isolation of natural products: A comprehensive review. Chin. Med. 2018, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasidharan, S.; Chen, Y.; Saravanan, D.; Sundram, K.M.; Yoga Latha, L. Extraction, isolation and characterization of bioactive compounds from plants’ extracts. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoddami, A.; Wilkes, M.A.; Roberts, T.H. Techniques for Analysis of Plant Phenolic Compounds. Molecules 2013, 18, 2328–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belwal, T.; Ezzat, S.M.; Rastrelli, L.; Bhatt, I.D.; Daglia, M.; Baldi, A.; Devkota, H.P.; Orhan, I.E.; Patra, J.K.; Das, G.; et al. A critical analysis of extraction techniques used for botanicals: Trends, priorities, industrial uses and optimization strategies. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2018, 100, 82–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Mu, T.; Sun, H.; Garcia-Vaquero, M. Phlorotannins: A review of extraction methods, structural characteristics, bioactivities, bioavailability, and future trends. Algal Res. 2021, 60, 102484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma, M.; Vinatoru, M.; Paniwnyk, L.; Mason, T.J. Investigation of the effects of ultrasound on vegetal tissues during solvent extraction. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2001, 8, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinatoru, M. An overview of the ultrasonically assisted extraction of bioactive principles from herbs. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2001, 8, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oroian, M.; Escriche, I. Antioxidants: Characterization, natural sources, extraction and analysis. Food Res. Int. 2015, 74, 10–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luthria, D.L. Significance of sample preparation in developing analytical methodologies for accurate estimation of bioactive compounds in functional foods. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2006, 86, 2266–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, D.; Pereira-Pinto, R.; Fernandes, É.; Pires, P.; Vaz-Velho, M. Microwave-Assisted Extraction for the Sustainable Recovery and Valorization of Phenolic Compounds from Maritime Pine Bark. Sustain. Chem. 2025, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, H.; Gomes, V.; Aliaño-González, M.J.; Faleiro, L.; Romano, A.; Medronho, B. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Polyphenols from Maritime Pine Residues with Deep Eutectic Solvents. Foods 2022, 11, 3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of Total Phenolics with Phosphomolybdic-Phosphotungstic Acid Reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, E.A.; Gillespie, K.M. Estimation of total phenolic content and other oxidation substrates in plant tissues using Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 875–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinelo, M.; Rubilar, M.; Sineiro, J.; Núñez, M.J. Extraction of antioxidant phenolics from almond hulls (Prunus amygdalus) and pine sawdust (Pinus pinaster). Food Chem. 2004, 85, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coscueta, E.R.; Reis, C.A.; Pintado, M. Phenylethyl Isothiocyanate Extracted from Watercress By-Products with Aqueous Micellar Systems: Development and Optimisation. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinela, J.; Barros, L.; Dueñas, M.; Carvalho, A.M.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Antioxidant activity, ascorbic acid, phenolic compounds and sugars of wild and commercial Tuberaria lignosa samples: Effects of drying and oral preparation methods. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 1028–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, K.L.; Liu, R.H. Cellular Antioxidant Activity (CAA) Assay for Assessing Antioxidants, Foods, and Dietary Supplements. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 8896–8907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockowandt, L.; Pinela, J.; Roriz, C.L.; Pereira, C.; Abreu, R.M.V.; Calhelha, R.C.; Alves, M.J.; Barros, L.; Bredol, M.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Chemical features and bioactivities of cornflower (Centaurea cyanus L.) capitula: The blue flowers and the unexplored non-edible part. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 128, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mármol, I.; Vieito, C.; Andreu, V.; Levert, A.; Amiot, A.; Bertrand, C.; Rodríguez-Yoldi, M.J.; Santos, J.; Vaz-Velho, M. Influence of extraction solvent on the biological properties of maritime pine bark (Pinus pinaster). Int. J. Food Stud. 2022, 11, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twenty-Second Informational Supplement, CLSI Document M100-S22; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rasband, W.S. ImageJ; U.S. National Institutes of Health: Bethesda, MD, USA, 1997–2018. Available online: https://imagej.net/ij/ (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Mandim, F.; Graça, V.C.; Calhelha, R.C.; Machado, I.L.F.; Ferreira, L.F.V.; Ferreira, I.; Santos, P.F. Synthesis, Photochemical and In Vitro Cytotoxic Evaluation of New Iodinated Aminosquaraines as Potential Sensitizers for Photodynamic Therapy. Molecules 2019, 24, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandim, F.; Barros, L.; Calhelha, R.C.; Abreu, R.M.V.; Pinela, J.; Alves, M.J.; Heleno, S.; Santos, P.F.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Calluna vulgaris (L.) Hull: Chemical characterization, evaluation of its bioactive properties and effect on the vaginal microbiota. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobral, F.; Sampaio, A.; Falcão, S.; Queiroz, M.J.R.P.; Calhelha, R.C.; Vilas-Boas, M.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Chemical characterization, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and cytotoxic properties of bee venom collected in Northeast Portugal. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2016, 94, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessada, S.M.F.; Barreira, J.C.M.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P. Phenolic profile and antioxidant activity of Coleostephus myconis (L.) Rchb.f.: An underexploited and highly disseminated species. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 89, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diouf, P.N.; Stevanovic, T.; Boutin, Y. The effect of extraction process on polyphenol content, triterpene composition and bioactivity of yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis Britton) extracts. Ind. Crops Prod. 2009, 30, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, V.; Mohan, Y.; Hemalatha, S. Microwave Assisted Extraction—An Innovative and Promising Extraction Tool for Medicinal Plant Research. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2006, 1, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Weller, C.L. Recent advances in extraction of nutraceuticals from plants. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2006, 17, 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinatoru, M.; Mason, T.J.; Calinescu, I. Ultrasonically assisted extraction (UAE) and microwave assisted extraction (MAE) of functional compounds from plant materials. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2017, 97, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azwanida, N.N. A review on the extraction methods use in medicinal plants, principle, strength and limitation. Med. Aromat. Plants 2015, 4, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanase, C.; Erzsébet, D.; Coșarcă, S.-L.; Miklos, A.; Imre, S.; Domokos, J.; Dehelean, C. Study of the Ultrasound-assisted Extraction of Polyphenols from Beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) Bark. Bioresources 2018, 13, 2247–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniwnyk, L.; Beaufoy, E.; Lorimer, J.P.; Mason, T.J. The extraction of rutin from flower buds of Sophora japonica. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2001, 8, 299–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Santos, P.; Genisheva, Z.; Botelho, C.; Santos, J.; Ramos, C.; Teixeira, J.A.; Rocha, C.M.R. Unravelling the Biological Potential of Pinus pinaster Bark Extracts. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, R.; Pimentel, C.; Ferreira-Dias, S.; Miranda, I.; Pereira, H. Phytochemical characterization of phloem in maritime pine and stone pine in three sites in Portugal. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sládková, A.; Benedeková, M.; Stopka, J.; Surina, I.; Haz, A.; Strižincová, P.; Kučíková, K.; Butor Skulcova, A.; Burčová, Z.; Kreps, F.; et al. Yield of Polyphenolic Substances Extracted From Spruce (Picea abies) Bark by Microwave-Assisted Extraction. Bioresources 2016, 11, 9912–9921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Santos, P.; Genisheva, Z.; Pereira, R.N.; Teixeira, J.A.; Rocha, C.M.R. Moderate Electric Fields as a Potential Tool for Sustainable Recovery of Phenolic Compounds from Pinus pinaster Bark. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 8816–8826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Esteban, J.I.; Pinela, J.; Barros, L.; Ćirić, A.; Soković, M.; Calhelha, R.C.; Torija-Isasa, E.; de Cortes Sánchez-Mata, M.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Phenolic composition and antioxidant, antimicrobial and cytotoxic properties of hop (Humulus lupulus L.) Seeds. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 134, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, E.N.; Molina, A.K.; Pereira, C.; Dias, M.I.; Heleno, S.A.; Rodrigues, P.; Fernandes, I.P.; Barreiro, M.F.; Stojković, D.; Soković, M.; et al. Anthocyanins from Rubus fruticosus L. and Morus nigra L. Applied as Food Colorants: A Natural Alternative. Plants 2021, 10, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilaquinga, F.; Morey, J.; Fernandez, L.; Espinoza-Montero, P.; Moncada-Basualto, M.; Pozo-Martinez, J.; Olea-Azar, C.; Bosch, R.; Meneses, L.; Debut, A.; et al. Determination of Antioxidant Activity by Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORAC-FL), Cellular Antioxidant Activity (CAA), Electrochemical and Microbiological Analyses of Silver Nanoparticles Using the Aqueous Leaf Extract of Solanum mammosum L. Int. J. Nanomed. 2021, 16, 5879–5894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, V.; Pereira, C.; Abreu, R.M.V.; Calhelha, R.C.; Alves, M.J.; Coutinho, J.A.P.; Ferreira, O.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Hydroethanolic extract of Juglans regia L. green husks: A source of bioactive phytochemicals. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 137, 111189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, A.; Moreira, T.F.M.; Pepinelli, A.L.S.; Costa, L.G.M.A.; Leal, L.E.; da Silva, T.B.V.; Gonçalves, O.H.; Porto Ineu, R.; Dias, M.I.; Barros, L.; et al. Bioactivity screening of pinhão (Araucaria Angustifolia (Bertol.) Kuntze) seed extracts: The inhibition of cholinesterases and α-amylases, and cytotoxic and anti-inflammatory activities. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 9820–9828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, T.E.; Marcondes, A.; Zardo, D.M.; Nogueira, A.; Calhelha, R.C.; Vaz, J.A.; Barros, L.; Zielinski, A.A.F.; Alberti, A. Bioactive Activities of the Phenolic Extract from Sterile Bracts of Araucaria angustifolia. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Brooks, M.S.-L. Use of Red Beet (Beta vulgaris L.) for Antimicrobial Applications—A Critical Review. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2018, 11, 17–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisca, A.; Ștefănescu, R.; Stegăruș, D.I.; Mare, A.D.; Farczadi, L.; Tanase, C. Comparative Study Regarding the Chemical Composition and Biological Activity of Pine (Pinus nigra and P. sylvestris) Bark Extracts. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascón, S.; Jiménez-Moreno, N.; Jiménez, S.; Quero, J.; Rodríguez-Yoldi, M.J.; Ancín-Azpilicueta, C. Nutraceutical composition of three pine bark extracts and their antiproliferative effect on Caco-2 cells. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 48, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.-Z.; Sun, J.; Chen, P.; Monagas, M.J.; Harnly, J.M. UHPLC-PDA-ESI/HRMSn Profiling Method to Identify and Quantify Oligomeric Proanthocyanidins in Plant Products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 9387–9400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Tuo, X.; Wang, L.; Tundis, R.; Portillo, M.P.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Yu, Y.; Zou, L.; Xiao, J.; Deng, J. Bioactive procyanidins from dietary sources: The relationship between bioactivity and polymerization degree. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 111, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Wang, K.; Liu, X.; Liu, G.; Hu, Z.; Zhao, L. Characterization and bioactivity of A-type procyanidins from litchi fruitlets at different degrees of development. Food Chem. 2023, 405, 134855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, T.; Chen, J.; McClements, D.J.; Hu, P.; Ye, X.; Liu, C.; Li, T. Protein–polyphenol interactions enhance the antioxidant capacity of phenolics: Analysis of rice glutelin–procyanidin dimer interactions. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chupin, L.; Motillon, C.; Charrier-El Bouhtoury, F.; Pizzi, A.; Charrier, B. Characterisation of maritime pine (Pinus pinaster) bark tannins extracted under different conditions by spectroscopic methods, FTIR and HPLC. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 49, 897–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Santos, P.; Zanuso, E.; Genisheva, Z.; Rocha, C.M.R.; Teixeira, J.A. Green and Sustainable Valorization of Bioactive Phenolic Compounds from Pinus By-Products. Molecules 2020, 25, 2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.