Ambient Air Pollution and Parkinson’s Disease and Alzheimer’s Disease: An Updated Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Databases and Search Strategies

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Assessment

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

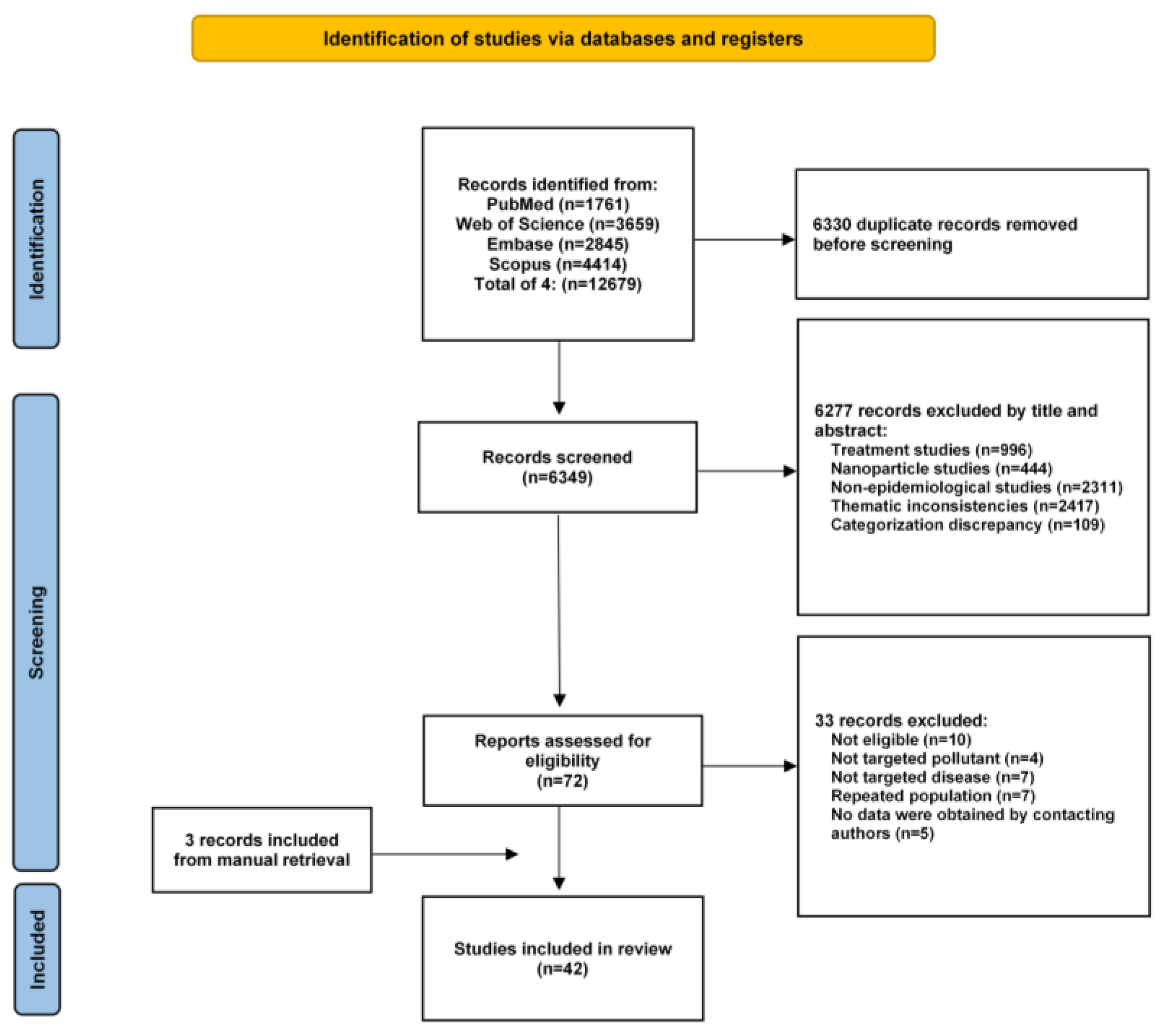

3.1. Results of the Search and Features of the Listed Studies

3.2. Estimated Effects of Particulate Matter

3.2.1. PM2.5

| No. | Reference | Study Design/ Location | Study Period | Exposure Metric | Sample/ Cases | Age, Years | Pollutants | Exposure Assessment | Outcome Measure | Outcome Assessment and Instruments Used for Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Carey et al. [34] (2018) | Cohort London | 2005–2013 | Long-term | 130,978/ 848 | 50–79 | PM2.5 NO2 O3 | Model estimation | First recorded diagnosis | Medical data record (ICD-10) and physician-diagnosed |

| 2 | Cerza et al. [35] (2019) | Cohort Roma | 2001–2013 | Long-term | 350,844/ 7669 | 74.5 | PM2.5 PM10 NO2 O3 | Model estimation | First hospitalization | Hospital records (ICD-9: 331.0) |

| 3 | Culqui et al. [36] (2017) | Time-series Madrid | 2001–2009 | Short-term (Lag2) | 754,005 | >60 | PM2.5 | Fixed monitoring site | Emergency hospital admission | ICD-9: 331.0 |

| 4 | de Crom et al. [37] (2023) | Cohort Netherlands | 2010–2018 | Long-term | 7511/ 406 | >45 | PM2.5 PM10 NO2 | Model estimation | Newly diagnosed cases | MMSE, medical data record, and physician-diagnosed |

| 5 | Gandini et al. [38] (2018) | Cohort Italy | 2001–2008 | Long-term | 74,989/ 248 | >35 | PM2.5 NO2 | Model estimation | First hospitalization | Medical data record (ICD-9: 331) |

| 6 | Jung et al. [39] (2015) | Cohort Taiwan | 2001–2010 | Long-term | 95,690/ 1399 | >65 | PM2.5 O3 | Fixed monitoring site | Newly diagnosed cases | Medical data record (ICD-9: 331.0) |

| 7 | Kioumourtzoglou et al. [40] (2016) | Cohort America | 1999–2010 | Long-term | 9,817,806/ 266,725 | 75.6 | PM2.5 | Fixed monitoring site | First hospital admission | Medical data record (ICD-9: 331.0) |

| 8 | Mortamais et al. [41] (2021) | Cohort French | 1990–2012 | Long-term | 7066/ 541 | 73.4 | PM2.5 NO2 | Model estimation | Newly diagnosed cases | Physician-diagnosed (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) |

| 9 | Nunez et al. [42] (2021) | Time-series America | 2000–2014 | Long-term | 264,075 | - | PM2.5 | Model estimation | First hospitalization | Hospitalization records (ICD-9: 331.0) |

| 10 | Ran et al. [43] (2020) | Cohort Hongkong | 1998–2011 | Long-term | 59,349/ 655 | >65 | PM2.5 | Model estimation | First hospitalization | Hospitalization records (ICD-9: 290.0, 290.2, 290.3, 331.0) |

| 11 | Shaffer et al. [44] (2021) | Cohort Seattle | 1994–2018 | Long-term | 4166/ 921 | >65 | PM2.5 | Model estimation | Newly diagnosed cases | Physician-diagnosed |

| 12 | Shi et al. [46] (2020) | Cohort America | 2000–2016 | Long-term | 63,038,019/2,490,431 | >65 | PM2.5 | Model estimation | First hospitalization | Hospital data (ICD-9: 331.0; ICD-10: G30.9) |

| 13 | Shi et al. [45] (2021) | Cohort America | 2000–2018 | Long-term | 12,456,447/804,668 | >65 | NO2 O3 | Model estimation | Newly diagnosed cases | Medicare claims (ICD-9: 331.0; G30.0, G30.1, G30.8, G30.9) |

| 14 | Shim et al. [47] (2023) | Cohort Korea | 2008–2019 | Long-term | 1,436,361 | 70.9 | PM10 | Fixed monitoring site | Newly diagnosed cases | ICD-10: F00, G30 |

| 15 | Trevenen et al. [48] (2022) | Cohort Australia | 1996–2018 | Long-term | 11,243/ 1670 | 72.1 | PM2.5 NO2 | Model estimation | Newly diagnosed cases | Self-reported, physician-diagnosed (ICD-9: 331.0, ICD-10: F00, G30) |

| 16 | Yang et al. [49] (2022) | Cohort China | 2018–2020 | Long-term | 1545 | 68.21 | PM2.5 | Model estimation | Prevalence | Physician-diagnosed |

| 17 | Yang et al. [50] (2024) | Time-series China | 2017–2019 | Short-term (Lag1) | 4975 | 79.82 | PM2.5 PM10 | Fixed monitoring site | Hospital admission | ICD-10: G30 |

| 18 | Younan et al. [51] (2022) | Cohort America | 1996–2010 | Long-term | 5798/ 130 | >65 | PM2.5 | Model estimation | Newly diagnosed cases | Physician-diagnosed |

| 19 | Yuchi et al. [52] (2020) | Case–control Canada | 1999–2003 | Long-term | 13,498/ 1227 | 45–84 | PM2.5 NO2 | Model estimation | Newly diagnosed cases | Hospital data (ICD-9: 331; ICD-10: G30) |

| 20 | Zanobetti et al. [53] (2014) | Case–crossover America | 1999–2010 | Short-term (lag02) | 146,172 | >65 | PM2.5 | Model estimation | Hospital admission | ICD-9: 331.0 |

| 21 | Zhang et al. [55] (2022) | Cohort Britain | 2006–2021 | Long-term | 227,840/ 1238 | 60.1 | PM2.5 PM10 NO2 | Model estimation | Newly diagnosed cases | Medical data record (ICD-9: 331.0; ICD-10: F00, F00.0, F00.1, F00.2, F00.9, G30, G30.0, G30.1, G30.8, G30.9) |

| 22 | Zhang et al. [54] (2023) | Case–crossover America | 2005–2015 | Short-term (lag03) | 1,595,783 | >45 | PM2.5 NO2 O3 | Model estimation | Emergency department visits | Hospital data |

| 23 | Zhu et al. [56] (2023) | Cohort China | 2015–2022 | Long-term | 29,025/ 182 | 63.32 | PM2.5 PM10 NO2 | Model estimation | Newly diagnosed cases | Medical data record (ICD-10: G30) |

| No. | Reference | Study Design/ Location | Study Period | Exposure Metric | Sample/ Cases | Age, Years | Pollutants | Exposure Assessment | Outcome Measure | Outcome Assessment and Instruments Used for Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cerza et al. [57] (2018) | Cohort Roma | 2008–2013 | Long-term | 1,008,253/ 13,104 | 63 | PM2.5 PM10 NO2 O3 | Model estimation | Newly diagnosed cases | Administrative data (ICD-9: 332.0) and prescription |

| 2 | Chen et al. [58] (2017) | Case–control Taiwan | 2000–2013 | Long-term | 54,524/ 1060 | 40–80 | PM10 NO2 SO2 CO O3 | Fixed monitoring site | Newly diagnosed cases | Physicians’ diagnoses (ICD-9: 332) |

| 3 | Finkelstein, Jerrett [59] (2007) | Case–control Hamilton/Toronto | 1992–1999 | Long-term | 111,348/ 509 | Birth year from 1900 to 1978 | NO2 | Model estimation | Newly diagnosed cases | Physicians’ diagnoses (ICD9: 332) and prescriptions for L-Dopa containing medications |

| 4 | Gandini et al. [38] (2018) | Cohort Itlay | 2001–2008 | Long-term | 74,989/ 149 | >35 | PM2.5 NO2 | Model estimation | First hospitalization | Medical data record (ICD-9: 332) |

| 5 | Goria et al. [60] (2021) | Time series France | 2009–2017 | Short-term (lag01) | 196,479 | - | PM2.5 PM10 NO2 O3 | Fixed monitoring site | Hospital admission | ICD-10: G20, F023 |

| 6 | Gu et al. [61] (2020) | Time series China | 2013–2017 | Short-term (lag1) | 4,433,661 | - | PM2.5 O3 | Fixed monitoring site | Hospital admission | ICD-10 |

| 7 | Kioumourtzoglou et al. [40] (2016) | Cohort America | 1999–2010 | Long-term | 9,817,806/ 119,425 | 75.6 | PM2.5 | Fixed monitoring site | First hospital admission | Medical data record (ICD-9: 332) |

| 8 | Kirrane et al. [62] (2015) | Case–control North Carolina/Iowa | 1993–2010 | Long-term | 83,343/ 301 | 12–92/42.77 | PM2.5 O3 | Model estimation | Newly diagnosed cases | Self-reported and physician-diagnosed |

| 9 | Lee et al. [65] (2016) | Case–control Taiwan | 2007–2010 | Long-term | 55,585/ 11,117 | 72 | PM10 SO2 CO O3 | Model estimation | Newly diagnosed cases | Physicians’ diagnoses (ICD9: 332.0) |

| 10 | Lee et al. [64] (2017) | Case–crossover Korea | 2002–2013 | Short-term (lag07) | 314 | - | PM2.5 NO2 SO2 CO O3 | Fixed monitoring site | Emergency admission case | Physician-diagnosed |

| 11 | Lee et al. [63] (2022) | Cohort Korea | 2007–2015 | Long-term | 313,355/ 2621 | 48.9 | PM2.5 PM10 | Model estimation | Newly diagnosed cases | Hospital visit data (ICD-10: G20) and prescriptions |

| 12 | Liu et al. [66] (2016) | Case–control America | 1995–2006 | Long-term | 4869 | 63.7 | PM2.5 PM10 NO2 | Model estimation | Newly diagnosed cases | Self-reported and physician-diagnosed |

| 13 | Nunez et al. [42] (2021) | Time series America | 2000–2014 | Long-term | 114,514 | - | PM2.5 | Model estimation | First hospitalization | Hospitalization records (ICD-9: 332.0) |

| 14 | Palacios et al. [68] (2014) | Cohort America | 1990–2008 | Long-term | 115,767/ 508 | 30–55 | PM2.5 PM10 | Model estimation | Newly diagnosed cases | Self-reported and physician-diagnosed |

| 15 | Palacios et al. [67] (2017) | Cohort America | 1988–2010 | Long-term | 50,352/ 550 | 40–75 | PM2.5 PM10 | Model estimation | Newly diagnosed cases | Self-reported and physician-diagnosed |

| 16 | Ritz et al. [69] (2016) | Case–control Denmark | 1996–2009 | Long-term | 3496/ 1696 | 62 | NO2 CO | Model estimation | Newly diagnosed cases | Physician-diagnosed |

| 17 | Rumrich et al. [70] (2023) | Case–control Finland | 1996–2015 | Long-term | 139,525/ 21,187 | 70.6 | PM2.5 PM10 | Model estimation | Newly diagnosed cases | ICD-10 |

| 18 | Salimi et al. [71] (2019) | Cross-sectional Australia | 2006–2009 | Long-term | 236,390/ 1428 | 62.5 | PM2.5 NO2 | Model estimation | Prevalence | Physician-diagnosed |

| 19 | Shi et al. [46] (2020) | Cohort America | 2000–2016 | Long-term | 63,038,019/ 1,033,669 | 69.9 | PM2.5 | Model estimation | First hospitalization | Hospital data (ICD-9: 332; ICD-10: G20, G21.11, G21.19, G21.8) |

| 20 | Shin et al. [72] (2018) | Cohort Canada | 2001–2013 | Long-term | 2,194,519/ 38,745 | 67 | PM2.5 NO2 O3 | Model estimation | Newly diagnosed cases | Hospital record |

| 21 | Toro et al. [73] (2019) | Case–control Netherlands | 2010–2012 | Long-term | 1290/ 436 | 69 | PM2.5 PM10 NO2 | Model estimation | Newly diagnosed cases | Physician-diagnosed |

| 22 | Wei et al. [74] (2019) | Case–crossover America | 2000–2012 | Short-term (lag01) | 214 | - | PM2.5 | Model estimation | Hospital admission | ICD-9 |

| 23 | Yu et al. [75] (2021) | Cohort Ningbo | 2015–2018 | Long-term | 47,516/ 206 | 62.27 | PM2.5 PM10 NO2 | Model estimation | Newly diagnosed cases | Medical data record (ICD-10: G20, G21.11, G21.19, G21.8) |

| 24 | Yuchi et al. [52] (2020) | Cohort Canada | 1999–2003 | Long-term | 634,432/ 4201 | 58.1 | PM2.5 NO2 | Model estimation | Newly diagnosed cases | Physician claims recorded (332) and prescriptions |

| 25 | Zanobetti et al. [53] (2014) | Case–crossover America | 1999–2010 | Short-term (lag02) | 40,496 | >65 | PM2.5 | Model estimation | Hospital admission | ICD-9: 332 |

| Outcome | Pollutant | Exposure Duration | No. of Estimates | OR | 95%CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | PM2.5 | Long-term | 17 | 1.16 | 1.04, 1.30 | 0.010 |

| PM2.5 | Short-term | 4 | 1.02 | 0.99, 1.05 | 0.185 | |

| PM10 | Long-term | 5 | 1.03 | 0.96, 1.10 | 0.411 | |

| NO2 | Long-term | 10 | 1.01 | 0.99, 1.02 | 0.455 | |

| O3 | Long-term | 4 | 0.9998 | 0.99, 1.01 | 0.954 | |

| PD | PM2.5 | Long-term | 17 | 1.10 | 1.03, 1.17 | 0.003 |

| PM2.5 | Short-term | 5 | 1.01 | 1.002, 1.01 | 0.016 | |

| PM10 | Long-term | 10 | 0.99 | 0.99, 1.004 | 0.235 | |

| NO2 | Long-term | 11 | 1.01 | 1.0002, 1.02 | 0.045 | |

| O3 | Long-term | 6 | 1.003 | 0.9998, 1.01 | 0.065 | |

| O3 | Short-term | 3 | 1.002 | 0.999, 1.005 | 0.284 | |

| CO | Long-term | 3 | 1.32 | 0.82, 2.11 | 0.255 |

3.2.2. Particulate Matter with a Diameter Smaller than 10 μm (PM10)

3.3. Estimated Effects of Gaseous Pollutants

3.3.1. NO2

3.3.2. O3

3.3.3. Sulfur Dioxide (SO2)

3.3.4. Carbon Monoxide (CO)

3.4. Subgroup Analysis

3.4.1. PM2.5 Exposure and AD

3.4.2. PM2.5 Exposure and PD

3.4.3. The Association Between NO2 Exposure, and AD and PD

3.5. Publication Bias and Sensitivity Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Results

4.2. Biological Plausibility

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lamptey, R.N.L.; Chaulagain, B.; Trivedi, R.; Gothwal, A.; Layek, B.; Singh, J. A Review of the Common Neurodegenerative Disorders: Current Therapeutic Approaches and the Potential Role of Nanotherapeutics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, S.; Miller, M.I.; Joshi, P.S.; Lee, J.C.; Xue, C.; Ni, Y.; Wang, Y.; De Anda-Duran, I.; Hwang, P.H.; Cramer, J.A.; et al. Multimodal deep learning for Alzheimer’s disease dementia assessment. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Śliwińska, S.; Jeziorek, M. The role of nutrition in Alzheimer’s disease. Rocz. Panstw. Zakl. Hig. 2021, 72, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, S.; Atluri, V.; Kaushik, A.; Yndart, A.; Nair, M. Alzheimer’s disease: Pathogenesis, diagnostics, and therapeutics. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 5541–5554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhiman, V.; Trushna, T.; Raj, D.; Tiwari, R.R. Is ambient air pollution a risk factor for Parkinson’s disease? A meta-analysis of epidemiological evidence. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2022, 33, 733–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestrino, R.; Schapira, A.H.V. Parkinson disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 2019, 27, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lau, L.M.L.; Breteler, M.M.B. Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2006, 5, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Eeden, S.K. Incidence of Parkinson’s Disease: Variation by Age, Gender, and Race/Ethnicity. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2003, 157, 1015–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, R.A. Risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease. Folia Neuropathol. 2019, 57, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, L.V.; Lang, A.E. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 2015, 386, 896–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyer, O.; Rahman, A.; Hristov, H.; Berkowitz, C.; Isaacson, R.S.; Diaz Brinton, R.; Mosconi, L. Female Sex and Alzheimer’s Risk: The Menopause Connection. J. Prev. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 5, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nianogo, R.A.; Rosenwohl-Mack, A.; Yaffe, K.; Carrasco, A.; Hoffmann, C.M.; Barnes, D.E. Risk Factors Associated With Alzheimer Disease and Related Dementias by Sex and Race and Ethnicity in the US. JAMA Neurol. 2022, 79, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noyce, A.J.; Bestwick, J.P.; Silveira-Moriyama, L.; Hawkes, C.H.; Giovannoni, G.; Lees, A.J.; Schrag, A. Meta-analysis of early nonmotor features and risk factors for Parkinson disease. Ann. Neurol. 2012, 72, 893–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellou, V.; Belbasis, L.; Tzoulaki, I.; Evangelou, E.; Ioannidis, J.P. Environmental risk factors and Parkinson’s disease: An umbrella review of meta-analyses. Park. Relat. Disord. 2016, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dockery, D.W.; Pope, C.A., 3rd; Xu, X.; Spengler, J.D.; Ware, J.H.; Fay, M.E.; Ferris, B.G., Jr.; Speizer, F.E. An association between air pollution and mortality in six U.S. cities. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993, 329, 1753–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoek, G.; Krishnan, R.M.; Beelen, R.; Peters, A.; Ostro, B.; Brunekreef, B.; Kaufman, J.D. Long-term air pollution exposure and cardio- respiratory mortality: A review. Environ. Health Glob. Access Sci. Source 2013, 12, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangas, T.; Gadeyne, S.; Lefebvre, W.; Vanpoucke, C.; Rodriguez-Loureiro, L. Are air quality perception and PM2.5 exposure differently associated with cardiovascular and respiratory disease mortality in Brussels? Findings from a census-based study. Environ. Res 2023, 219, 115180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderón-Garcidueñas, L.; Calderón-Garcidueñas, A.; Torres-Jardón, R.; Avila-Ramírez, J.; Kulesza, R.J.; Angiulli, A.D. Air pollution and your brain: What do you need to know right now. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2015, 16, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, L.G.; Cole, T.B.; Dao, K.; Chang, Y.C.; Coburn, J.; Garrick, J. Neurotoxicity of air pollution: Role of neuroinflammation. Adv. Neurotoxicol. 2019, 3, 195–221. [Google Scholar]

- Thiankhaw, K.; Chattipakorn, N.; Chattipakorn, S.C. PM2.5 exposure in association with AD-related neuropathology and cognitive outcomes. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 292, 118320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heusinkveld, H.J.; Wahle, T.; Campbell, A.; Westerink, R.H.S.; Tran, L.; Johnston, H.; Stone, V.; Cassee, F.R.; Schins, R.P.F. Neurodegenerative and neurological disorders by small inhaled particles. Neurotoxicology 2016, 56, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Garciduẽnas, L.; Avila-Ramírez, J.; Calderón-Garciduẽnas, A.; González-Heredia, T.; Acũna-Ayala, H.; Chao, C.K.; Thompson, C.; Ruiz-Ramos, R.; Cortés-González, V.; Martínez-Martínez, L.; et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in highly exposed PM2.5 urbanites: The risk of Alzheimer’s and parkinson’s diseases in Young Mexico City Residents. In Alzheimer’s Disease and Air Pollution: The Development and Progression of a Fatal Disease from Childhood and the Opportunities for Early Prevention; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 477–493. [Google Scholar]

- Calderón-Garcidueñas, L.; Franco-Lira, M.; D’Angiulli, A.; Rodríguez-Díaz, J.; Blaurock-Busch, E.; Busch, Y.; Chao, C.K.; Thompson, C.; Mukherjee, P.S.; Torres-Jardón, R.; et al. Mexico City normal weight children exposed to high concentrations of ambient PM2.5 show high blood leptin and endothelin-1, vitamin D deficiency, and food reward hormone dysregulation versus low pollution controls. Relevance for obesity and Alzheimer disease. Environ. Res. 2015, 140, 579–592. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pradhan, A.U.; Uwishema, O.; Onyeaka, H.; Adanur, I.; Dost, B. A review of stem cell therapy: An emerging treatment for dementia in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Brain Behav. 2022, 12, 4878–4890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooray, R.; Gupta, V.; Suphioglu, C. Current Aspects of the Endocannabinoid System and Targeted THC and CBD Phytocannabinoids as Potential Therapeutics for Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s Diseases: A Review. Mol. Neurobiol. 2020, 57, 4878–4890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erkkinen, M.G.; Kim, M.-O.; Geschwind, M.D. Clinical Neurology and Epidemiology of the Major Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2018, 10, a033118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ Clin. Res. Ed. 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, C. How to Understand the 95% Confidence Interval Around the Relative Risk, Odds Ratio, and Hazard Ratio: As Simple as It Gets. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2023, 84, 47304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doi, S.A.; Furuya-Kanamori, L.; Xu, C.; Lin, L.; Chivese, T.; Thalib, L. Controversy and Debate: Questionable utility of the relative risk in clinical research: Paper 1: A call for change to practice. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2022, 142, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahami Monfared, A.A.; Byrnes, M.J.; White, L.A.; Zhang, Q. Alzheimer’s Disease: Epidemiology and Clinical Progression. Neurol. Ther. 2022, 11, 553–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinmetz, J.D.; Seeher, K.M.; Schiess, N.; Nichols, E.; Cao, B.; Servili, C.; Atalell, K.A. Global, regional, and national burden of disorders affecting the nervous system, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. Neurol. 2024, 23, 344–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsey, E.R.; Elbaz, A.; Nichols, E.; Abbasi, N.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A.; Murray, C.J. Global, regional, and national burden of Parkinson’s disease, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. Neurol. 2018, 17, 939–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichols, E.; Szoeke, C.E.; Vollset, S.E.; Abbasi, N.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdela, J.; Murray, C.J. Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. Neurol. 2019, 18, 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carey, I.M.; Anderson, H.R.; Atkinson, R.W.; Beevers, S.D.; Cook, D.G.; Strachan, D.P.; Dajnak, D.; Gulliver, J.; Kelly, F.J. Are noise and air pollution related to the incidence of dementia? A cohort study in London, England. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e022404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerza, F.; Renzi, M.; Gariazzo, C.; Davoli, M.; Michelozzi, P.; Forastiere, F.; Cesaroni, G. Long-term exposure to air pollution and hospitalization for dementia in the Rome longitudinal study. Environ. Health Glob. Access Sci. Source 2019, 18, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Culqui, D.R.; Linares, C.; Ortiz, C.; Carmona, R.; Diaz, J. Association between environmental factors and emergency hospital admissions due to Alzheimer’s disease in Madrid. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 592, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Crom, T.O.E.; Ginos, B.N.R.; Oudin, A.; Ikram, M.K.; Voortman, T.; Ikram, M.A. Air Pollution and the Risk of Dementia: The Rotterdam Study. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2023, 91, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandini, M.; Scarinzi, C.; Bande, S.; Berti, G.; Carnà, P.; Ciancarella, L.; Costa, G.; Demaria, M.; Ghigo, S.; Piersanti, A.; et al. Long term effect of air pollution on incident hospital admissions: Results from the Italian Longitudinal Study within LIFE MED HISS project. Environ. Int. 2018, 121 Pt 2, 1087–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.R.; Lin, Y.T.; Hwang, B.F. Ozone, particulate matter, and newly diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease: A population-based cohort study in Taiwan. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2015, 44, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kioumourtzoglou, M.A.; Schwartz, J.D.; Weisskopf, M.G.; Melly, S.J.; Wang, Y.; Dominici, F.; Zanobetti, A. Long-term PM2.5 exposure and neurological hospital admissions in the northeastern United States. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortamais, M.; Gutierrez, L.-A.; de Hoogh, K.; Chen, J.; Vienneau, D.; Carriere, I.; Letellier, N.; Helmer, C.; Gabelle, A.; Mura, T.; et al. Long-term exposure to ambient air pollution and risk of dementia: Results of the prospective Three-City Study. Environ. Int. 2021, 148, 106376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunez, Y.; Boehme, A.K.; Weisskopf, M.G.; Re, D.B.; Navas-Acien, A.; van Donkelaar, A.; Martin, R.V.; Kioumourtzoglou, M.A. Fine particle exposure and clinical aggravation in neurodegenerative diseases in new york state. Environ. Health Perspect. 2021, 129, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ran, J.; Schooling, C.M.; Han, L.; Sun, S.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, X.; Chan, K.P.; Guo, F.; Lee, R.S.; Qiu, Y.; et al. Long-term exposure to fine particulate matter and dementia incidence: A cohort study in Hong Kong. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 271, 116303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, R.M.; Blanco, M.N.; Li, G.; Adar, S.D.; Carone, M.; Szpiro, A.A.; Kaufman, J.D.; Larson, T.V.; Larson, E.B.; Crane, P.K.; et al. Fine Particulate Matter and Dementia Incidence in the Adult Changes in Thought Study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2021, 129, 87001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Steenland, K.; Li, H.; Liu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Lyles, R.H.; Requia, W.J.; Ilango, S.D.; Chang, H.H.; Wingo, T.; et al. A national cohort study (2000-2018) of long-term air pollution exposure and incident dementia in older adults in the United States. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Wu, X.; Danesh Yazdi, M.; Braun, D.; Abu Awad, Y.; Wei, Y.; Liu, P.; Di, Q.; Wang, Y.; Schwartz, J.; et al. Long-term effects of PM2.5 on neurological disorders in the American Medicare population: A longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. Planet. Health 2020, 4, e557–e565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shim, J.-I.; Byun, G.; Lee, J.-T.T. Long-term exposure to particulate matter and risk of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia in Korea: A national population-based Cohort Study. Environ. Health 2023, 22, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trevenen, M.L.; Heyworth, J.; Almeida, O.P.; Yeap, B.B.; Hankey, G.J.; Golledge, J.; Etherton-Beer, C.; Robinson, S.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Flicker, L. Ambient air pollution and risk of incident dementia in older men living in a region with relatively low concentrations of pollutants: The Health in Men Study. Environ. Res 2022, 215 Pt 2, 114349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Wan, W.; Yu, C.; Xuan, C.; Zheng, P.; Yan, J. Associations between PM2.5 exposure and Alzheimer’s Disease prevalence Among elderly in eastern China. Environ. Health A Glob. Access Sci. Source 2022, 21, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Jiang, W.; Gao, X.; He, Y.; Lin, C.; Zhou, J.; Yang, L. Impact of airborne particulate matter exposure on hospital admission for Alzheimer's disease and the attributable economic burden: Evidence from a time-series study in Sichuan, China. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2024, 36, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younan, D.; Wang, X.; Gruenewald, T.; Gatz, M.; Serre, M.L.; Vizuete, W.; Braskie, M.N.; Woods, N.F.; Kahe, K.; Garcia, L.; et al. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Alzheimer’s Disease Risk: Role of Exposure to Ambient Fine Particles. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2022, 77, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuchi, W.; Sbihi, H.; Davies, H.; Tamburic, L.; Brauer, M. Road proximity, air pollution, noise, green space and neurologic disease incidence: A population-based cohort study. Environ. Health A Glob. Access Sci. Source 2020, 19, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanobetti, A.; Dominici, F.; Wang, Y.; Schwartz, J.D. A national case-crossover analysis of the short-term effect of PM2.5 on hospitalizations and mortality in subjects with diabetes and neurological disorders. Environ. Health A Glob. Access Sci. Source 2014, 13, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Shi, L.; Ebelt, S.T.; D’Souza, R.R.; Schwartz, J.D.; Scovronick, N.; Chang, H.H. Short-term associations between ambient air pollution and emergency department visits for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Environ. Epidemiol. 2023, 7, e237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, C.; Yang, Y.; Li, H.; Cai, M.; Lin, H. Associations of Air Pollution and Genetic Risk With Incident Dementia: A Prospective Cohort Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2023, 192, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Yang, Z.; Yu, L.; Xu, L.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shen, P.; Lin, H.; Shui, L.; Tang, M.; et al. Residential greenness, air pollution and incident neurodegenerative disease: A cohort study in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 878, 163173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerza, F.; Renzi, M.; Agabiti, N.; Marino, C.; Gariazzo, C.; Davoli, M.; Michelozzi, P.; Forastiere, F.; Cesaroni, G. Residential exposure to air pollution and incidence of Parkinson’s disease in a large metropolitan cohort. Environ. Epidemiol. 2018, 2, e023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-Y.; Hung, H.-J.; Chang, K.-H.; Hsu, C.Y.; Muo, C.-H.; Tsai, C.-H.; Wu, T.-N. Long-term exposure to air pollution and the incidence of Parkinson’s disease: A nested case-control study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkelstein, M.M.; Jerrett, M. A study of the relationships between Parkinson’s disease and markers of traffic-derived and environmental manganese air pollution in two Canadian cities. Environ. Res. 2007, 104, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goria, S.; Pascal, M.; Corso, M.; Le Tertre, A. Short-term exposure to air pollutants increases the risk of hospital admissions in patients with Parkinson’s disease—A multicentric study on 18 French areas. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 264, 118668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Shi, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, N.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, T. Ambient air pollution and cause-specific risk of hospital admission in China: A nationwide time-series study. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirrane, E.F.; Bowman, C.; Davis, J.A.; Hoppin, J.A.; Blair, A.; Chen, H.; Patel, M.M.; Sandler, D.P.; Tanner, C.M.; Vinikoor-Imler, L.; et al. Associations of Ozone and PM2.5 Concentrations With Parkinson’s Disease Among Participants in the Agricultural Health Study. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2015, 57, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Kim, O.-J.; Jung, J.; Myung, W.; Kim, S.-Y. Long-term exposure to particulate air pollution and incidence of Parkinson’s disease: A nationwide population-based cohort study in South Korea. Environ. Res. 2022, 212, 113165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Myung, W.; Kim, D.K.; Kim, S.E.; Kim, C.T.; Kim, H. Short-term air pollution exposure aggravates Parkinson’s disease in a population-based cohort. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.-C.; Liu, L.-L.; Sun, Y.; Chen, Y.-A.; Liu, C.-C.; Li, C.-Y.; Yu, H.-L.; Ritz, B. Traffic-related air pollution increased the risk of Parkinson’s disease in Taiwan: A nationwide study. Environ. Int. 2016, 96, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; Young, M.T.; Chen, J.-C.; Kaufman, J.D.; Chen, H. Ambient Air Pollution Exposures and Risk of Parkinson Disease. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124, 1759–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palacios, N.; Fitzgerald, K.C.; Hart, J.E.; Weisskopf, M.; Schwarzschild, M.A.; Ascherio, A.; Laden, F. Air Pollution and Risk of Parkinson’s Disease in a Large Prospective Study of Men. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 087011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palacios, N.; Fitzgerald, K.C.; Hart, J.E.; Weisskopf, M.G.; Schwarzschild, M.A.; Ascherio, A.; Laden, F. Particulate matter and risk of Parkinson disease in a large prospective study of women. Environ. Health Glob. Access Sci. Source 2014, 13, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritz, B.; Lee, P.C.; Hansen, J.; Lassen, C.F.; Ketzel, M.; Sørensen, M.; Raaschou-Nielsen, O. Traffic-Related Air Pollution and Parkinson’s Disease in Denmark: A Case-Control Study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumrich, I.K.; Lin, J.; Korhonen, A.; Frohn, L.M.; Geels, C.; Brandt, J.; Hartikainen, S.; Hanninen, O.; Tolppanen, A.-M. Long-term exposure to low-level particulate air pollution and Parkinson’s disease diagnosis-A Finnish register-based study. Environ. Res. 2023, 229, 115944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salimi, F.; Hanigan, I.; Jalaludin, B.; Guo, Y.; Rolfe, M.; Heyworth, J.S.; Cowie, C.T.; Knibbs, L.D.; Cope, M.; Marks, G.B.; et al. Associations between long-term exposure to ambient air pollution and Parkinson’s disease prevalence: A cross-sectional study. Neurochem. Int. 2020, 133, 104615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Burnett, R.T.; Kwong, J.C.; Hystad, P.; van Donkelaar, A.; Brook, J.R.; Copes, R.; Tu, K.; Goldberg, M.S.; Villeneuve, P.J.; et al. Effects of ambient air pollution on incident Parkinson’s disease in Ontario, 2001 to 2013: A population-based cohort study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 47, 2038–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toro, R.; Downward, G.S.; van der Mark, M.; Brouwer, M.; Huss, A.; Peters, S.; Hoek, G.; Nijssen, P.; Mulleners, W.M.; Sas, A.; et al. Parkinson’s disease and long-term exposure to outdoor air pollution: A matched case-control study in the Netherlands. Environ. Int. 2019, 129, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Wang, Y.; Di, Q.; Choirat, C.; Wang, Y.; Koutrakis, P.; Zanobetti, A.; Dominici, F.; Schwartz, J.D. Short term exposure to fine particulate matter and hospital admission risks and costs in the Medicare population: Time stratified, case crossover study. BMJ Clin. Res. Ed. 2019, 367, l6258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Wei, F.; Zhang, X.; Wu, M.; Lin, H.; Shui, L.; Jin, M.; Wang, J.; Tang, M.; Chen, K. Air pollution, surrounding green, road proximity and Parkinson’s disease: A prospective cohort study. Env. Res 2021, 197, 111170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Jin, Y.; Dou, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Duan, Y.; Pei, H.; Lyu, P. Long-term particulate matter 2.5 exposure and dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health 2022, 212, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, X.; Chang, H.; Zhang, J.; Gao, Z.; Mi, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Huang, C.; et al. Global ambient particulate matter pollution and neurodegenerative disorders: A systematic review of literature and meta-analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 39418–39430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciottolo, M.; Wang, X.; Driscoll, I.; Woodward, N.; Saffari, A.; Reyes, J.; Serre, M.L.; Vizuete, W.; Sioutas, C.; Morgan, T.E.; et al. Particulate air pollutants, APOE alleles and their contributions to cognitive impairment in older women and to amyloidogenesis in experimental models. Transl. Psychiatry 2017, 7, e1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, J.; Zhang, Y.; Han, L.; Sun, S.; Zhao, S.; Shen, C.; Zhang, X.; Chan, K.P.; Lee, R.S.; Qiu, Y.; et al. The joint association of physical activity and fine particulate matter exposure with incident dementia in elderly Hong Kong residents. Environ. Int. 2021, 156, 106645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, L.G.; Cole, T.B.; Coburn, J.; Chang, Y.C.; Dao, K.; Roqué, P.J. Neurotoxicity of traffic-related air pollution. Neurotoxicology 2017, 59, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, D.P.; Puig, K.L.; Gorr, M.W.; Wold, L.E.; Combs, C.K. A pilot study to assess effects of long-term inhalation of airborne particulate matter on early Alzheimer-like changes in the mouse brain. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Xiong, L.; Tang, M. Toxicity of inhaled particulate matter on the central nervous system: Neuroinflammation, neuropsychological effects and neurodegenerative disease. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2017, 37, 644–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Guo, J.; Huang, Y.; Liu, S.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Lu, Z.; Li, F.; Zheng, J.C.; et al. Urban airborne PM2.5—activated microglia mediate neurotoxicity through glutaminase-containing extracellular vesicles in olfactory bulb. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 264, 114716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahad, O.; Lelieveld, J.; Birklein, F.; Lieb, K.; Daiber, A.; Münzel, T. Ambient Air Pollution Increases the Risk of Cerebrovascular and Neuropsychiatric Disorders through Induction of Inflammation and Oxidative Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Perez, R.D.; Taborda, N.A.; Gomez, D.M.; Narvaez, J.F.; Porras, J.; Hernandez, J.C. Inflammatory effects of particulate matter air pollution. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 42390–42404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Jiang, C. Evolution of blood-brain barrier in brain diseases and related systemic nanoscale brain-targeting drug delivery strategies. Acta Pharm. Sinica B 2021, 11, 2306–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderón-Garcidueñas, L.; Solt, A.C.; Henríquez-Roldán, C.; Torres-Jardón, R.; Nuse, B.; Herritt, L.; Villarreal-Calderón, R.; Osnaya, N.; Stone, I.; García, R.; et al. Long-term air pollution exposure is associated with neuroinflammation, an altered innate immune response, disruption of the blood-brain barrier, ultrafine particulate deposition, and accumulation of amyloid β-42 and α-synuclein in children and young adults. Toxicol. Pathol. 2008, 36, 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, R.V.; Ellerby, H.M.; Bredesen, D.E. Coupling endoplasmic reticulum stress to the cell death program. Cell Death Differ. 2004, 11, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandics, T.; Major, D.; Fazekas-Pongor, V.; Szarvas, Z.; Peterfi, A.; Mukli, P.; Gulej, R.; Ungvari, A.; Fekete, M.; Tompa, A.; et al. Exposome and unhealthy aging: Environmental drivers from air pollution to occupational exposures. GeroScience 2023, 45, 3381–3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Kang, J.M.; Myung, W.; Choi, J.; Lee, C.; Na, D.L.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Han, S.H.; Choi, S.H.; et al. Exposure to ambient fine particles and neuropsychiatric symptoms in cognitive disorder: A repeated measure analysis from the CREDOS (Clinical Research Center for Dementia of South Korea) study. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 668, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranft, U.; Schikowski, T.; Sugiri, D.; Krutmann, J.; Krämer, U. Long-term exposure to traffic-related particulate matter impairs cognitive function in the elderly. Environ. Res. 2009, 109, 1004–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, W.; Yun, Y.; Ku, T.; Li, G.; Sang, N. NO2 inhalation promotes Alzheimer’s disease-like progression: Cyclooxygenase-2-derived prostaglandin E2 modulation and monoacylglycerol lipase inhibition-targeted medication. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, F.; Tang, J.J.; Zhang, T.; Lin, J.; Li, F.; Gu, X.; Chen, R. Impact of Air Pollution on Cognitive Impairment in Older People: A Cohort Study in Rural and Suburban China. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020, 77, 1671–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Kim, Y.J.; Park, K.W.; Hwang, Y.S.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, B.J.; Chung, S.J. Association of NO2 and Other Air Pollution Exposures With the Risk of Parkinson Disease. JAMA Neurol. 2021, 78, 800–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Z.; Yuan, Y.; White, A.J.; Li, C.; Luo, Z.; D’Aloisio, A.A.; Huang, X.; Kaufman, J.D.; Sandler, D.P.; Chen, H. Air Pollutants and Risk of Parkinson’s Disease among Women in the Sister Study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2024, 132, 17001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xie, C.; Xia, X.; Wang, K.; Yan, J.; Bai, L.; Guo, L.; Li, X.; Wu, S. Ambient Air Pollution and Parkinson’s Disease and Alzheimer’s Disease: An Updated Meta-Analysis. Toxics 2025, 13, 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13020139

Xie C, Xia X, Wang K, Yan J, Bai L, Guo L, Li X, Wu S. Ambient Air Pollution and Parkinson’s Disease and Alzheimer’s Disease: An Updated Meta-Analysis. Toxics. 2025; 13(2):139. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13020139

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Cuiyao, Xi Xia, Kai Wang, Jie Yan, Lijun Bai, Liqiong Guo, Xiaoxue Li, and Shaowei Wu. 2025. "Ambient Air Pollution and Parkinson’s Disease and Alzheimer’s Disease: An Updated Meta-Analysis" Toxics 13, no. 2: 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13020139

APA StyleXie, C., Xia, X., Wang, K., Yan, J., Bai, L., Guo, L., Li, X., & Wu, S. (2025). Ambient Air Pollution and Parkinson’s Disease and Alzheimer’s Disease: An Updated Meta-Analysis. Toxics, 13(2), 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13020139