Abstract

Background: Port digital transition is central to competitiveness and sustainability, yet existing frameworks devoted to such transition toward smart port are descriptive, technology-centered, or weak on data governance. This study designs and empirically refines a comprehensive and novel ten-step roadmap relative to existing Port/Industry 4.0 models, synthesized from 14 partial frameworks that each cover only subsets of the transition, by considering data governance and consolidating cost, time, and impact in the selection step. Methods: We synthesized recent Industry 4.0 and smart port-related frameworks into a normalized sequence of steps embedded in the so-called roadmap, then examined it in an exploratory case of a technology deployment project in a Canadian port using stakeholder interviews and project documents. Evidence was coded with a step-aligned scheme, and stakeholder feedback and implementation observations assessed whether each step’s outcomes were met. Results: The sequence proved useful yet revealed four recurrent hurdles: limited maturity assessment, uneven stakeholder engagement, ad hoc technology selection and integration, and under-specified data governance. The refined roadmap adds a diagnostic maturity step with target-state setting and gap analysis, a criteria-based selection worksheet, staged deployment with checkpoints, and compact indicators of transformation performance, such as reduced logistics delays, improved energy efficiency, and technology adoption. Conclusions: The work couples theory-grounded synthesis with empirical validation and provides decision support to both ports and public authorities to prioritize investments, align stakeholders, propose successful policies and digitalization supporting programs, and monitor outcomes, while specifying reusable steps and indicators for multi-port testing and standardized metrics.

1. Introduction

Global maritime trade continues to show sustained growth, driven by globalization and accompanied by technological advances associated with Industry 4.0 [1]. While Industry 4.0 does not directly cause this growth, it accelerates innovation and efficiency in global transportation networks. Demand for maritime transport, measured in ton-miles, is projected to increase by around 39% by 2050 compared to 2018 [1]. In 2022, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development anticipated a recovery in maritime traffic, projecting growth of 2.4% in 2023 after a slight contraction of 0.4% in 2022 [2]. This trend, which has persisted for several decades with an average annual increase of 3 to 4%, is expected to lead to a 35–40% rise in global trade volumes by 2050 [3]. This dynamic compels ports to modernize rapidly in order to meet growing customer demands and rising inter-port competition on both new and existing market segments [4]. At the same time, the need to reduce the environmental impacts of port activities reinforces the urgency toward more sustainable operations [5]. Port digitalization therefore becomes a key lever for contributing to international sustainability agendas, including the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), by improving energy efficiency, reducing emissions, and supporting more resilient maritime logistics. In this context, digital transformation emerges as a strategic lever to optimize performance and ensure port resilience in the face of current and future challenges [6]. Beyond its operational benefits, it also represents a progressive pathway toward the smart port paradigm, which stands as the ultimate objective of this transition, a model combining technological innovation, data intelligence, and sustainable management to enhance competitiveness and long-term efficiency.

In this paper, we use the term “digital maturity” to describe the degree to which a port has deployed digital technologies, integrated them into its processes, trained its workforce for the required skills, and established governance mechanisms that allow consistent and reliable use of data in decision-making. These digital technologies rely on advanced solutions such as artificial intelligence (AI), the Internet of Things (IoT), big data, and process automation [7]. We also define the term “smart port” as a port that systematically leverages connected digital infrastructure, real-time data, and advanced analytics to coordinate operations, manage resources, and minimize environmental impacts in line with broader sustainability and competitiveness objectives. One illustrative example of such a digital technology, a cost–benefit analysis of a Port Community System, a digital platform that connects all port stakeholders to exchange operational data in real time, demonstrated its positive impact on operational fluidity, reduced transit times, and stronger cooperation among stakeholders [8]. Other technology-driven initiatives further highlight the benefits of digital transformation, such as the integration of AI at the Port of Hamburg, which significantly reduced waiting times and improved synchronization of logistical operations [9]. Some countries have invested heavily in this digital transition, such as South Korea, which allocated 160 million USD between 2016 and 2018 to modernize the Port of Busan [10]. However, these investments often encounter budgetary constraints, particularly for medium-sized ports that must balance digital modernization investments with economic viability [11].

Digital transformation enhances the competitiveness, efficiency, and sustainability of ports. Nevertheless, several obstacles hinder this evolution, including economic, organizational, and technological challenges. The absence of a structured methodological framework complicates investment planning and prioritization [12]. Poorly targeted investments may also result in underutilization of digital technologies, thereby reducing profitability and slowing port modernization [13]. These issues are especially critical for medium-sized ports, which must constantly arbitrate between digital modernization based on advanced technologies and financial viability in an environment of rising budgetary constraints [11]. Although digital transformation is a strategic imperative, it represents a considerable cost that many ports cannot afford, limiting their ability to adopt advanced technological solutions [14]. For such ports, a gradual transition adapted to financial and organizational capacities is necessary to ensure a successful digital transformation [15]. Additional barriers include a shortage of skilled labor, the absence of clear governance frameworks, and heterogeneous levels of digital maturity across port functional domains (e.g., cargo operations, logistics, and administrative services) and their supporting information systems, which complicate interoperability and integration at the scale of the whole port ecosystem [16].

The literature proposes few methodological frameworks to structure port digital transformation. However, existing contributions remain limited within the port sector itself, while a significant number of frameworks have been developed in the manufacturing sector, pioneering engaged in the Industry 4.0 transition [17]. For example, a nine-step methodological framework was designed specifically for Brazilian ports’ digital transformation, integrating governance and human resource parameters, which hinder its applicability to other contexts [7]. Similarly, the sequential framework in [18], although successfully applied at the Port of Valencia, is based on a rigid approach that impeded the flexibility of adaptation to ports with varying levels of digital maturity. Beyond these port-specific contributions (such as the Brazilian ports and the Port of Valencia), Port 4.0 models, digital-twin based frameworks, and Industry 4.0 maturity checklists tend to remain either descriptive, technology-centered, or weak on data governance and stakeholder engagement, which limits their transferability across ports of different sizes and institutional configurations. Critical issues such as data governance, system interoperability, and participatory mechanisms are often treated as secondary design choices rather than as central structuring dimensions of the transformation process. These limitations are particularly problematic for ports that seek to align digital investments with sustainability targets and SDG-related commitments.

From a methodological standpoint, the main gap is not the lack of digital solutions but the lack of actionable guidance on how to prioritize, sequence, and govern the transition across time. In practice, ports face intertwined decisions related to system architecture, interoperability requirements, data-sharing rules among stakeholders, and organizational change management, and these decisions strongly condition whether digital initiatives remain isolated pilots or evolve toward scalable, ecosystem-level capabilities. When governance, interoperability, and stakeholder alignment are not treated as structuring dimensions, investment planning becomes more uncertain and the probability of fragmented implementation increases, especially in ports with heterogeneous information systems and uneven maturity across functional domains.

Against this background, the present study addresses the following research question: how can ports, and especially medium-sized ports, structure their digital transition toward the smart port paradigm? This article proposes a digital transition roadmap designed to overcome the aforementioned limitations of existing frameworks by integrating an evolutionary stepwise approach, grounded in a systematic literature review of existing methodological frameworks and an exploratory case study on an advanced technology implementation project within a Canadian port. Rather than proposing a methodological break with existing theoretical models, this study complements them by positioning the roadmap as a governance- and data-oriented refinement of Port 4.0 and Industry 4.0 maturity approaches, generalizable to ports with different profiles while paying particular attention to the realities of medium-sized ports.

This focus is motivated by the fact that medium-sized ports are frequently encouraged to pursue smart port ambitions while facing tighter financial margins, fewer specialized digital skills, and more constrained information system integration capacity than major hubs, which increases the need for structured, feasible, and staged decision support for investments and implementation choices.

Specifically, the proposed roadmap rests on three key contributions. First, it integrates continuous digital maturity assessment, enabling ports to tailor their transition to their level of technological development and organizational capacity while ensuring strategic investment prioritization. Second, it emphasizes data governance to foster interoperability, ensuring coherent integration of digital technologies while mitigating risks of system incompatibility. Third, it adopts a collaborative approach that actively involves stakeholders through a structured consultation framework to align expectations and encourage commitment to digital initiatives.

The article begins by clarifying the conceptual foundations of the smart port and the main challenges associated with digital transition. It then details the dual methodological approach used in this research, combining a systematic literature review and an exploratory case study, which together support the development and validation-enrichment of a ten-step roadmap for port digital transition. The following parts present the theoretical synthesis of existing methodological frameworks, the proposed roadmap, and its empirical experimentation through the analysis of a trucking traceability technology implementation project within a Canadian port. The paper concludes by summarizing the principal findings, highlighting the roadmap’s practical contributions for decision support by port authorities and suggesting avenues for future research.

2. Smart Port

Several researchers have proposed definitions of the smart port concept without reaching a consensus. A first definition was introduced based on the main activity domains of a smart port in [19,20], followed by a more exhaustive enumeration of seven key domains, namely operations, human resources, safety, environment, energy, social aspects, and technological infrastructure [4]. According to these authors, a smart port is defined as a port “connected, sustainable, safe, and automated, based on modern infrastructure, innovative managerial practices, and qualified personnel” [4]. While these contributions converge on the central role of digital technologies and connectivity, they differ in the emphasis they place on technological infrastructure, governance mechanisms, and sustainability objectives. Some definitions remain predominantly technology-centered, whereas others foreground organizational practices, stakeholder coordination, or environmental performance as core components of smartness.

However, although definitions are becoming more precise, their implementation in operational reality remains a challenge [5,17,21]. The adoption of digital technologies and practices depends not only on a theoretical vision, but also on the ability of ports to overcome organizational, technical, and financial obstacles [5]. For instance, projects such as the smart port initiative in Hamburg have shown that significant investments do not always guarantee success, with difficulties often linked to stakeholder resistance, coordination issues, or integration barriers rather than to technology alone [22]. The Port of Rotterdam also illustrates this complexity: it took nearly twenty years to implement a Port Community System, a digital platform designed to optimize the management of logistics flows and commercial operations by facilitating the exchange of information between port actors [5]. This long trajectory underlines the importance of governance arrangements, standardization efforts, and progressive alignment of stakeholders around shared digital technologies and practices.

Beyond efficiency and competitiveness, smart port initiatives are increasingly expected to contribute to environmental sustainability and energy efficiency. Digital platforms, real-time monitoring, and predictive analytics can support reduced congestion, better energy management, and lower emissions at the port–city interface [5,22,23,24]. In this sense, port digitalization is closely linked to global sustainability agendas, including the United Nations SDGs, particularly SDG 9 on resilient infrastructure and innovation, SDG 11 on sustainable cities and communities, SDG 12 on responsible consumption and production, SDG 13 on climate action, and SDG 17 on partnerships. Positioning smart ports within this normative framework highlights that digital transition is not an end in itself, but a means to reconcile operational performance with decarbonization, territorial integration, and long-term resilience.

Despite the opportunities offered by digital transformation, many ports struggle to structure their transition toward the smart port model [17]. One of the limiting factors lies in the absence of roadmaps adapted to their specific contexts, which complicates the assessment of digital maturity and the alignment of resources with strategic priorities and stakeholder expectations [5,17]. This observation highlights the need to develop and experiment with stepwise approaches tailored to the operational realities of each port, particularly medium-sized ports that face strong financial and organizational constraints [21]. Nevertheless, the literature points to a deficit of a roadmap that can structure and, where possible, quantify the digital transformation process toward smart port [17]. Although the benefits of such a transition are widely recognized [5,22,23], there is no universally adopted framework to guide port authorities in this transformation [5,25].

In light of this gap, several researchers suggest drawing inspiration from pioneering advances toward Industry 4.0 in the manufacturing sector to facilitate the transition [18,26]. Specifically, proven digital transformation methodological frameworks can be adapted to the port sector [26] to overcome the absence of sector-specific tools. Moreover, to address the lack of structured frameworks tailored to port specificities, several researchers have emphasized the importance of developing strategic roadmaps to guide the technological and organizational choices of port authorities [21,25]. Roadmaps provide a structured framework for decision-making that takes into account available resources, risk exposure, and expected impacts. For instance, some studies recommend the development of strategic roadmaps to support the implementation and operation of digital port platforms, highlighting the importance of a structured approach for achieving successful digital transformation [14]. Other contributions propose the standardization of digital port services, offering a roadmap for their implementation within the “Port of the Future” framework [25]. These initiatives aim to provide port authorities with actionable frameworks either to assess their digital maturity [21,25,27] or to align their resources with strategic priorities and to respond effectively to stakeholder expectations.

At the same time, port authorities must also take into account the risks associated with technological investments [28]. Some authors emphasize the importance of rigorous risk management, particularly regarding uncertainties linked to the adoption of new technologies, the profitability of such digital investments, and their integration in existing infrastructure [14]. However, this literature does not propose a specific, stepwise model to structure such management, but rather insists on the need for strategic planning and prior impact assessments to minimize the vulnerabilities associated with digital transformations [14]. This combination of fragmented transformation frameworks, and limited guidance on governance and risk management reinforces the need for a roadmap that explicitly integrates digital maturity assessment, stakeholder coordination, and data governance, as developed in the following sections.

3. Materials and Methods

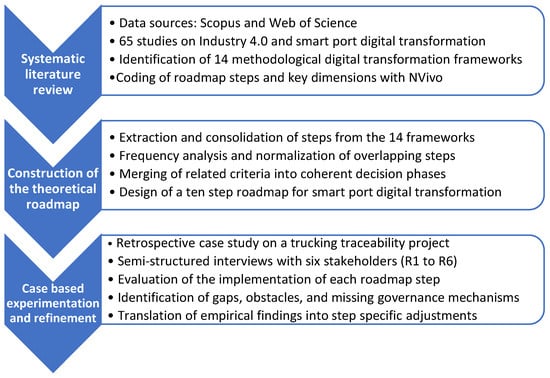

This study is based on a two-part methodological approach: a systematic literature review leading to the proposal of a theoretical roadmap, and an empirical case study that tests and refines this roadmap. This dual approach makes it possible to examine the digital transformation of ports from two complementary perspectives: on the one hand, by relying on a synthesis of theoretical frameworks, and on the other hand, by identifying empirical findings from the assessment of the proposed roadmap on a real case study.

3.1. Systematic Literature Review—Theoretical Construction of the Roadmap

The literature review was carried out in two complementary phases, one focused on the maritime sector and the other on Industry 4.0. Searches were conducted in recognized databases such as ABI, Scopus, EBSCO, JCR, Emerald Insight, and ScienceDirect, using combinations of keywords like “smart port” AND “roadmap” AND “Industry 4.0” AND “maturity index”. Only peer-reviewed articles in French or English were retained.

The review period extends from January 2010 to May 2024, so that major developments in digital transformation in ports and in pioneering industrial sectors are covered. The starting point of 2010 corresponds to the emergence of the first smart-port initiatives and the diffusion of Industry 4.0 technologies, which have significantly reshaped logistics and maritime practices since that time [26]. The end date, May 2024, corresponds to the most recent period available when the review was conducted, which allows the inclusion of up-to-date contributions.

The initial search produced a broader set of references that were first deduplicated. Titles and abstracts were then screened to retain articles that explicitly proposed a sequence of steps, phases, or stages for digital transformation in ports or in Industry 4.0 contexts. Full texts were consulted when relevance could not be clearly established from the abstract alone. The inclusion criteria required that a paper: describe a methodological or managerial framework for digital transition, and address at least one of the following dimensions: governance, stakeholder involvement, data management, or technology deployment. Publications that were not peer-reviewed, that only presented technical solutions without methodological or organizational considerations, or that referred to digitalization in a very generic manner were excluded.

After this process, 65 articles were selected. These articles constitute the theoretical foundation of the proposed roadmap, by integrating lessons drawn from previous studies and identifying recurrent steps and gaps. The steps appearing in each framework were mapped into a reconciliation matrix in order to compare the sequences proposed by smart port contributions and by Industry 4.0 transformation models. This comparative analysis made it possible to cluster convergent elements and to identify where key issues such as digital maturity assessment, data governance, and stakeholder participation were treated in depth, only mentioned, or largely ignored. On this basis, a ten-step roadmap was established to support ports’ transition toward a smart port model while reflecting operational constraints and the need for progressive digital transformation.

3.2. Exploratory Case—Empirical Testing of the Roadmap

The theoretical roadmap was tested through a retrospective exploratory case study of a trucking traceability technology implementation project at the Port of Trois-Rivières (PTR), Canada. This qualitative approach makes it possible to analyze a complex phenomenon in its real context and to confront theoretical assumptions with operational realities [29,30]. It also highlights organizational, technological, and managerial dimensions that influence port digital transformation [31,32]. Located on one of the gateways to the St. Lawrence–Great Lakes region, which represents the world’s third-largest economy, the PTR is a medium-sized, multi-cargo port (liquid bulk, dry bulk, and non-containerized cargo). This profile makes it representative of many ports that face limited financial and organizational resources while being encouraged to engage in digital transition.

The project studied concerns the deployment of an advanced traceability technology for trucking activities during their transit at the port, from the entry gate to the exit gate. The solution, developed by the technology firm SMATS Traffic Solutions, relies on IoT sensors that analyze and forecast truck traffic flows in near real time in order to reduce congestion and improve logistics management [24]. Its implementation in a medium-sized port with diversified cargo flows offers a concrete example of the integration of Industry 4.0-type technologies into a port environment.

An inductive qualitative methodology was adopted to collect and analyze data. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with three categories of stakeholders involved in the project. In total, six participants were interviewed: the innovation manager and the executive vice-president at the port authority, the innovation director and the CEO-founder of the technology provider, and two academics conducting research on PTR logistics analytics. Three separate interview guides were designed to reflect the roles and responsibilities of these actors.

- The guide for port authority personnel focused on motivations for the project, governance issues, and challenges related to integrating the technology into port management.

- The guide for the technology provider examined deployment issues, compatibility with existing infrastructure, information systems, required adaptations, and perceived risks.

- The guide for the academics explored the analytical needs that motivated the implementation of enhanced traceability, as well as how such new data unlocked by the solution could be used for logistics optimization and performance assessment.

This segmentation of interviews ensured a balanced representation of strategic, technical, and analytical perspectives and provided a comprehensive understanding of the project. The interviews were complemented by a documentary analysis of technical documentation, project progress reports, and meeting minutes, which ensured data triangulation and strengthened the validity of the results [33]. The analysis was conducted using Nvivo software, 12 Plus (QSR International, 2018) which facilitated thematic and inductive coding of the material [34,35]. Codes were organized according to the ten steps of the proposed roadmap. For each step, we examined whether the conditions described in the theoretical roadmap were fully present, partially present, or absent in the project, based on interview evidence and documents.

This alignment between the coding scheme and the theoretical roadmap structure made it possible to identify where the case confirmed the relevance of the steps and where it revealed blind spots or ambiguities. In particular, recurrent difficulties were observed in relation to digital maturity assessment, stakeholder engagement, technology selection and integration, and data governance. These patterns were used to refine the initial theoretical roadmap within its existing ten-step structure, by clarifying the digital maturity assessment step, developing criteria-based tools for technology selection, and providing more explicit guidance on data governance and staged deployment.

To summarize the overall research design, Figure 1 provides an integrated view of the three main phases of the study, linking the systematic literature review, the construction of the initial theoretical roadmap, and its empirical refinement through the PTR case.

Figure 1.

Overview of the research design.

4. Proposed Roadmap

This section presents the theoretical roadmap developed from a systematic literature review of methodological frameworks for digital transformation toward smart port and Industry 4.0. The comparative analysis of these frameworks identifies approaches that are transferable to the port context and distills lessons to structure ports’ digital transition [25,36].

4.1. Methodological Frameworks Toward Industry 4.0

The literature highlights several structured methodological frameworks developed to support the transition toward Industry 4.0. One study outlined a five-step framework (1) raising awareness of Industry 4.0 to enhance efficiency, automation, and connectivity; (2) assessing maturity using a questionnaire such as the Acatech index; (3) analyzing results to identify gaps; (4) defining strategic objectives; and (5) selecting actions [37].

Another contribution integrated the Capability Maturity Model (CMM) to evaluate digital-process maturity and the Strategic Alignment Model to align digital objectives with corporate strategy. This framework follows six stages: (1) building a project team, (2) assessing digitalization, (3) defining actions, (4) conducting workshops, (5) estimating technology impacts, and (6) prioritizing use cases [38].

Complementarily, a maturity model assessing 65 key factors was developed, offering a ten-step methodological approach ranging from initial analysis to strategy definition. Although not presented as a prescriptive roadmap, it provides a methodological scaffold to guide digital transformation while requiring adaptation to specific organizational contexts [21].

Another methodology relied on the well-known Deming wheel to structure the digital transition of supply chains. This continuous improvement cycle is articulated in four stages: (1) Plan, which involves setting objectives and preparing an action plan; (2) Do, which covers the progressive deployment of digital technologies and real-world trials; (3) Check, which emphasizes the evaluation of key performance indicators and the identification of variances; and (4) Act, which consists of adjusting strategies accordingly [39].

Focusing on manufacturing SMEs, one study identified four axes of transformation: resources, culture, organization, and information systems, as the foundation for a progressive action strategy [37]. In parallel, another proposed a six-phase methodological model that includes (1) assessment of the current state, (2) selection of technologies, (3) deployment of technologies, (4) employee training, (5) redefinition of performance indicators, and (6) monitoring of technological choices [40].

Further research stressed the need for stepwise process flexibility, recommending the creation of multidisciplinary teams, awareness campaigns, and the use of key performance indicators to evaluate and adjust transformation strategies [41]. A related six-step approach has also been suggested, comprising: (1) initial assessment, (2) project-team formation, (3) process analysis, (4) knowledge acquisition, (5) solution deployment, and (6) performance evaluation [42].

Finally, a five-phase framework was developed, consisting of (1) objective definition, (2) prioritization of critical criteria, (3) selection and management of technical resources, (4) project management, and (5) monitoring. Originally validated in the aerospace sector, this methodological approach demonstrates strong transferability to other industrial contexts [43].

4.2. Methodological Frameworks Toward Smart Port

The End-to-End Tool was introduced to evaluate the past, present, and future digitalization of ports. Its purpose is to identify digital transformation scenarios through three stages: (1) assessment of current maturity, (2) definition of target maturity, and (3) implementation of strategies to achieve objectives. While designed to facilitate decision-making, it does not provide a detailed methodological framework to guide ports in implementing the necessary actions, particularly in relation to technology selection, organizational adaptation, and resource management [44].

From a continuous improvement perspective, the evolution of Industry 4.0 in the port sector has been analyzed through a bibliometric study. This research identified four key stages: (1) adoption, (2) implementation, (3) operational exploitation, and (4) evaluation of digital technologies. Although this perspective structures the transition into four phases, it remains primarily an analytical framework to understand the factors influencing the transformation toward smart ports, which are still in an exploratory stage [45].

The validation of the roadmap developed and applied at the Port of Valencia aims to support the digital transformation of ports toward a smart port model. It adopts a sequential approach beginning with an assessment of digital maturity to identify specific needs and technological, organizational, and financial constraints. This diagnostic phase guides strategic decisions in digitalization. The emphasis remains on the selection and gradual integration of digital technologies, notably the IoT, AI, and blockchain. The latter are deployed through short-, medium-, and long-term planning, ensuring optimized resource management, risk mitigation, and the progressive adoption of digital innovations. Another key component lies in governance and monitoring: the model defines an organizational framework that assigns roles and responsibilities to stakeholders, promoting coordination among port actors. A system of monitoring and evaluation based on performance indicators is also proposed, enabling the adjustment of implementation strategies and the optimization of the digital transition. Active stakeholder involvement is considered a key success factor, fostering the acceptability and adoption of emerging technologies [18].

However, this validation of the roadmap presents certain limitations that must be addressed in assessing its applicability. It places predominant emphasis on technological and operational dimensions, while paying limited attention to organizational and strategic issues. For example, although it proposes a structured framework for technology implementation, it does not sufficiently integrate governance mechanisms, organizational change management, or the economic impacts of digitalization. Furthermore, the focus on technological planning overlooks challenges such as interoperability, cybersecurity, and the integration of legacy systems, factors that are critical for a sustainable and effective digital transition. Thus, while the Port of Valencia’s roadmap constitutes a structured methodological framework applied to a concrete case, its approach remains partial and requires complementing with a broader and more interdisciplinary perspective that incorporates organizational, economic, and strategic dimensions [18].

Another methodological framework was designed by [7] to guide ports and terminals in their digital transformation by integrating the principles of Industry 4.0. The latter emphasizes a methodical and context-sensitive approach to planning and progressive technology implementation. However, it is specifically rooted in the Brazilian port context, considering local infrastructure, resources, and management models, which limits its direct applicability to other port environments with different organizational and economic constraints. The methodological framework follows a multi-step structure: definition of strategic objectives, assessment of digital maturity, selection and implementation of technologies, stakeholder involvement, training, establishment of performance indicators, monitoring, and continuous improvement. This evolutionary approach allows ports to progress through successive levels of maturity according to their capacity to integrate technologies and adapt to digital requirements. One of the strengths of this framework lies in its adaptability to local contexts, with emphasis on resource management, rigorous monitoring through performance indicators, and a structured framework to optimize technological investments. Nonetheless, its focus remains on technological and operational dimensions, without sufficiently addressing strategic, organizational, and regulatory issues. Therefore, while it offers a detailed methodological framework for implementing digital solutions, its applicability beyond the Brazilian context requires significant adaptation to account for diverse economic, regulatory, and infrastructural realities. This detailed analysis substantiates the introductory claim that the Brazilian framework, while methodologically rich, has limited direct applicability to other port contexts.

Finally, an evaluation framework known as the Smart Port Maturity Model (SPMM) was proposed to measure the degree of digital transformation in ports [5]. This model evaluates five fundamental dimensions: energy and environment, capacity, safety and security, operations, and synchromodality. It provides a precise diagnostic of the level of digital maturity achieved by a port and informs its strategic choices regarding technological and organizational innovation. The SPMM integrates several steps: (1) assessing digital maturity, (2) identifying gaps between current and target states, and (3) developing tailored recommendations for the specific port context. While this analytical framework helps identify strengths and areas for improvement to enable a progressive transition toward a smart port model, it does not constitute a prescriptive roadmap. Instead, it is limited to diagnostic evaluation and strategic guidance, leaving ports with the responsibility of defining the concrete operational steps required to implement the recommendations.

4.3. Analysis and Results

The literature review was conducted in two complementary stages. First, Section 4.1 examined Industry 4.0 digital-transformation roadmaps from a general perspective, identifying their main methodological building blocks such as maturity assessment, gap analysis, technology selection, and continuous improvement. Then, Section 4.2 focused specifically on the port sector, analyzing how these Industry 4.0 principles have been adapted to this sea–land interface in transportation network and highlighting persistent gaps, particularly the limited integration of governance, organizational change management, and local operational constraints. Building on these insights and toward the design of a tailored roadmap for smart port transformation. This section synthesizes the key stages and methodological patterns identified across the reviewed studies. Table 1 summarizes the steps extracted from fourteen roadmaps addressing digital transformation in both Industry 4.0 and smart port contexts. Each step was classified in chronological order according to its presentation in the reviewed publications. To ensure a systematic and reproducible derivation of the roadmap, each candidate step was extracted and coded from the fourteen source roadmaps. The frequency of occurrence of each step was then tallied, and semantically overlapping items were consolidated under a normalized label. This structured mapping (extraction, coding, frequency tally, and consolidation) provides a transparent link between the literature corpus and the synthesized set of steps.

Table 1.

Steps of the digital transformation frameworks identified in the literature.

Based on this systematic mapping, we prioritized steps with higher recurrence and merged closely related criteria (e.g., cost, implementation timeline, and impact estimation) into the technology/practice selection phase, as these are interdependent decision inputs rather than standalone phases. This rule-based consolidation yields a coherent, non-redundant sequence that can be operationalized. According to Table 1, the steps “Evaluation and calculation of the maturity index” and “Definition of the target maturity level” stand out as the most frequently present in the reviewed roadmaps (71%). They are followed by “Definition of actions” (64%), as well as “Analysis of maturity index results” and “Analysis of gaps between current and target maturity levels”, both also appearing in 64% of the reviewed frameworks. In addition, half of the latter mentioned the steps “Selection of smart technologies and innovative managerial practices” and “Deployment of new technologies in chronological order”.

Although the step “Evaluation of transformation” is mentioned only once, it may play a crucial role in embedding a continuous improvement approach. As highlighted, this step ensures the constant adjustment of processes to evolving port challenges [4,46].

Stakeholder involvement remains a key success factor, particularly in the early stages of digital transformation. Effective communication from the outset and active participation throughout the project enable strategic cohesion and optimize resource allocation. The step “Idea generation” could also be merged with “Selection of technologies and innovative managerial practices,” as both fall within an iterative process of innovation and strategic technology choice. Such a merger would help structure decision-making more effectively and ensure coherence between identifying needs and selecting solutions.

Finally, to enhance practical usability, we normalized labels where different authors described the same operational intent using varied terms, and we split composite labels when a single item bundled distinct intents (e.g., evaluation vs. action planning). The resulting ten-step structure is therefore both traceable to the source models and applicable to port transformation programs. Compared with existing Port 4.0 roadmaps, SPMM-based tools, and generic Industry 4.0 maturity checklists, this synthesized structure explicitly integrates digital maturity diagnosis, stakeholder coordination, and governance-related choices as core, recurring steps rather than as optional or peripheral considerations.

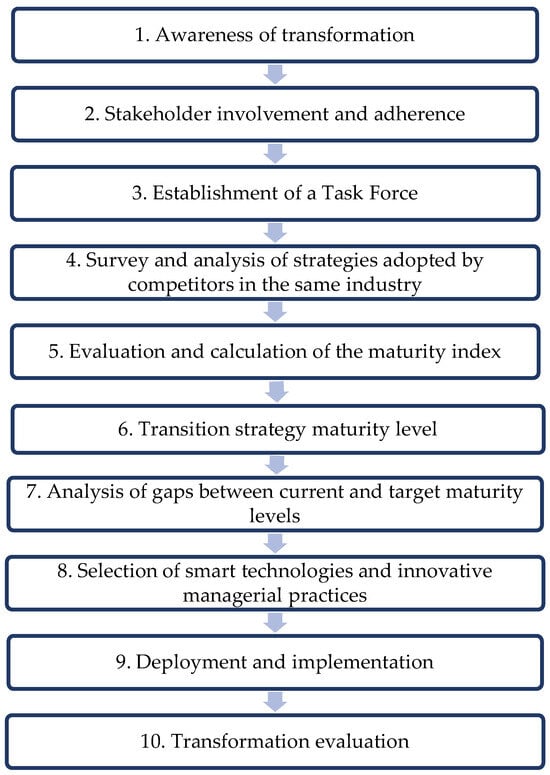

4.4. Steps of the Proposed Theoretical Roadmap

The proposed roadmap, illustrated in Figure 2, provides a simple and adaptable structure where each step is derived from previous systematic mapping among the fourteen roadmaps. Specifically, this rule-based integration avoids redundancy and clarifies decision logic, providing a coherent and operational sequence. Therefore, the proposed roadmap enables the selection, prioritization, and implementation of digital technologies according to strategic objectives, resource constraints, and timelines. Furthermore, it incorporates indicators to evaluate the effectiveness of implemented transformations and supports a process of continuous improvement, ensuring a dynamic response to the evolving challenges of the port sector. In contrast to existing Port 4.0 and smart port approaches, this ten-step roadmap combines a diagnostic maturity module, explicit stakeholder engagement, data governance, and a consolidated technology-selection step that jointly considers cost, time, and expected impact.

Figure 2.

Steps of the proposed roadmap for the transition to a smart port.

Each step is detailed below to explain its strategic objective, the key activities required, and any existing technique or method that can be used by port authorities to perform the step. The first step, awareness of digital transformation, aims to build a shared understanding of opportunities, expected benefits, and possible risks. Anticipating impacts on logistics flows, resources, and organizational processes is essential to maximize results and plan the adjustments required across the supply chain [41,47]. Typical activities include initial information sessions, targeted communication campaigns, and expert-led workshops or training to ensure decision-makers and operational teams are aligned on the project’s vision and scope [7,48].

The second step, stakeholder involvement and adherence, focuses on early and structured engagement of all actors who will influence or be affected by the transformation. This includes stakeholder mapping to identify key groups, clarifying roles and responsibilities, and establishing feedback mechanisms to maintain alignment. While innovation improves digital performance, natural resistance to change can persist [49,50]. Therefore, clear communication, visible top management support, and formal change management practices (e.g., kick-off meetings, regular updates, training plans) are crucial to foster adherence and minimize barriers to adoption [7].

The formation of a Task Force constitutes the third step. This team is responsible for coordinating resources and processes necessary for implementation while integrating both experts and stakeholders [51]. In practical terms, port authorities can formalize this step by appointing a cross-functional team (operations, IT, finance, legal, and terminal representatives), defining a clear mandate and decision rights, and setting a regular meeting schedule and reporting template to steer the project.

The fourth step involves the survey and analysis of strategies adopted by comparable companies. Comparative analysis of strategies developed by sector leaders makes it possible to identify best practices and anticipate challenges [21].

The evaluation and calculation of the maturity index, the fifth step, are based on tools such as the Acatech and IMPULS-VDMA models to measure the technological and organizational advancement of a port in its digital transition [52,53]. These models assess key dimensions, including organizational culture and operational processes, thereby providing an objective foundation for guiding digital transformation [53].

Once the current level of maturity has been determined, the sixth step consists of defining a target level aligned with the strategic ambitions of the port. This stage, drawing on models such as the Strategic Alignment Model, ensures that digital transformation is harmonized with organizational priorities and enables a progressive, coherent adoption of technologies [38].

The seventh step involves analyzing gaps between the current and target maturity levels to identify necessary adjustments and prioritize the actions required to fulfill them [54]. This diagnostic step provides the foundation for a structured implementation plan, ensuring effective transformation aligned with the defined objectives.

The eighth step is the selection of smart technologies and innovative managerial practices. This stage is based on cost, time, and impact criteria, with investment prioritization supported by structured techniques such as the Analytical Hierarchy Process, which weights decision criteria, or Cost–Benefit Analysis, which assesses the profitability of solutions before implementation [38].

The ninth step involves deploying and implementing the selected technologies in the chronological order established during the prioritization and phasing exercise of step 8. In this phase, deployment plans are adjusted to account for cost and time constraints, as well as local conditions such as existing infrastructure and the port’s capacity to progressively adopt and operate new innovations [7].

Finally, the tenth step, transformation evaluation, ensures that operational and technological performance is measured using indicators such as reduced logistics delays, improved energy efficiency, and the adoption success rate [45]. This stage also identifies necessary adjustments to the technologies deployed, management processes, and stakeholder training and, through the feedback loop represented in the step 2 of the roadmap, feeds these adjustments back into the earlier steps (maturity diagnosis, prioritization, deployment planning), thereby optimizing the digital transition over successive cycles. Continuous, closed-loop evaluation thus guarantees that the transformation remains aligned with the modernization and optimization objectives defined from the outset.

Although this roadmap rests on a solid theoretical foundation, practical experimentation is required to assess its applicability and relevance in a specific operational context [55]. In applied research, the evaluation of methodological frameworks helps determine their validity against field realities [31]. The literature further highlights the importance of such assessment in the port context, e.g., when analyzing digital maturity [5].

5. Experimentation of the Proposed Roadmap

The experimentation of the proposed roadmap is a pivotal phase for assessing both its theoretical robustness and its practical relevance. Rather than a simple descriptive check, this phase confronts the theoretical roadmap with the complex reality of a port environment in order to reveal its strengths, limitations, and areas for refinement. In line with design science research principles [31], the aim is not to claim definitive validation, but to transform a conceptual artifact into a pragmatic framework that can be used by decision-makers in port authorities, thereby generating both scientific and managerial insights.

In this regard, the retrospective case study conducted at the PTR provides a privileged setting for such an experiment. Positioned on a path of progressive digitalization through the adoption of truck traceability technology, this medium-sized port serves as a particularly relevant empirical laboratory. Its environment, characterized by limited resources, and specific organizational constraints, mirrors the challenges faced by many ports worldwide. Analyzing this case thus enables the assessment of the roadmap’s transferability while enriching the understanding of the real conditions of digital transformation in the port sector.

The experimentation thus pursues a dual objective. From a scientific perspective, it tests normative hypotheses drawn from the literature, assessing their adaptability to a specific context and their capacity to yield generalizable lessons. From a managerial perspective, it aims to provide port authorities with a pragmatic framework for action, capable of guiding the prioritization of initiatives, the allocation of resources, and the management of risks.

The experimentation is structured into two parts. The first evaluates the relevance and degree of implementation of each step of the proposed theoretical roadmap, confronting theoretical prescriptions with practices observed in the case study. The second suggests adjustments to the theoretical roadmap, derived from identified gaps, with the purpose of enhancing its applicability, flexibility, and operational value. These refinements go beyond technical recommendations; they are framed within a process of organizational learning and continuous improvement, which is fundamental to any digital transformation journey.

By combining empirical confrontation with theoretical roadmap adjustments, this experimentation contributes to advancing the academic literature on smart ports while also equipping practitioners with an adaptable strategic framework. It therefore seeks to move beyond a simple juxtaposition of theoretical guidelines, offering instead an evolving stepwise decision support tool transferable to a variety of port contexts, whether they be large international hubs or medium-sized ports striving toward digital transformation.

5.1. First Part: Evaluation of the Relevance of the Different Steps of the Initial Roadmap

The evaluation of the steps of the initial and solely theoretical-based roadmap for the digital transformation of the PTR was carried out through a retrospective study, based on semi-structured interviews conducted with stakeholders involved in the technology implementation project. For confidentiality purposes, interviewees were coded from R1 to R6. This design allowed the researchers to confront the theoretical roadmap, derived from the systematic review, with the practices implemented in the field. The analysis thus focused on how each step was followed, applied, or, conversely, adapted according to any operational, organizational, and contextual constraints specific to the studied port.

The first step of the roadmap, namely awareness of the transformation, aims to establish a common understanding of the smart port concept and its benefits. According to R1: “Our main objective is to provide efficient infrastructure […] By optimizing the use of our infrastructure, we aim to reduce transit times, which translates into significant environmental gains and an improvement in overall productivity.” As R1 notes, this step was not fully exploited: “Initial communication was not sufficiently thorough, which led to an uneven understanding of the project among stakeholders, complicating subsequent phases, […], this lack of communication generated misunderstandings and divergent expectations.” To strengthen this first step, the roadmap could be adjusted by integrating formal awareness and alignment mechanisms from the project launch, such as structured communication plans and interactive workshops to align expectations and avoid misunderstandings.

The second step, stakeholder involvement and adherence, appears not to have been completed. Although their active participation was decisive, the experience of the PTR highlighted insufficient involvement of field operators, leading to resistance and delays. As reported by R2: “Certain stakeholders, such as terminal operators, were not sufficiently engaged from the beginning, which led to resistance and delays in certain phases of the project”. This observation underlines the need for rigorous planning to ensure effective involvement of all parties from the initial stages.

The third step, the establishment of a working team within the TR dedicated to digital transformation, faced several difficulties, particularly related to frequent changes in team composition and internal coordination problems. R2 mentions in this context that: “Changes in team composition and coordination difficulties limited its effectiveness at the PTR.” R3 confirms that “The team composition had to be modified several times. Roles and responsibilities were not clearly defined or properly communicated, which compromised the effectiveness of monitoring and the smooth running of the project.” This experience highlights the importance of maintaining stability in team composition and ensuring effective coordination from the start of the project.

Step four, the inventory and study of strategies adopted by other companies in the sector, although theoretically relevant, revealed its limitations in the context of the PTR. As R3 pointed out: “The specificity of the PTR, which operates mainly in bulk, did not allow us to find examples to follow or to benefit from the experiences of pioneering port authorities in digital transformation.” This observation is also confirmed by R2: “I conducted a market study by researching on Google Scholar, but I found no examples of similar ports that had developed truck tracking and traceability technology” outside container terminals. Finally, R1 indicates: “I contacted port authorities to benefit from their experience, but I did not obtain conclusive answers or concrete examples implemented in the field.” Although comparative analysis with other ports could not be fully exploited, it remains essential to structure digital transition and anticipate challenges, provided that lessons are adapted to local realities.

Step five, the evaluation and calculation of the maturity index, was not formally carried out at the PTR. As R2 specifies: “No evaluation or calculation of maturity index was performed by the PTR” or any that may resemble to such. This observation is corroborated by R5, who adds: “This transformation project was proposed without stemming from an evaluation or calculation of the maturity index.” Similarly, R3 indicates: “No evaluation was carried out.” The absence of digital maturity evaluation complicated the identification of real needs and the prioritization of actions to be undertaken. A structured evaluation framework would have allowed for better guiding transformation efforts and ensuring a more coherent and measurable project progression.

The sixth step, the definition of port challenges and the target maturity level, was lacking at the PTR, which led to confusion about project priorities. As R6 underlines: “The port needed a traceability solution for road transport, as this part constituted a black box for the port authority. However, the PTR did not provide a clear definition of its challenges, nor did it prioritize or hierarchize them.” R1 also confirms the lack of clarity on the challenges: “There was no clear definition of the challenges, but chance and opportunity allowed the PTR to be placed on this digital transformation project.” This highlights the importance of clarifying challenges from the beginning to ensure coherence and efficient resource allocation.

Since step six was not performed, step seven of the analysis of gaps between the current and target maturity level, could not be carried out at the PTR as confirmed by R5 and R6. This absence of analysis limited the port’s ability to effectively target areas needing improvement.

The eighth step, the selection of advanced technologies and innovative managerial practices, was carried out without an exhaustive evaluation of available options, which possibly led to suboptimal choices. R4 explains: “It was a combination of luck, networking, and, of course, the presentation of our products at seminars, conferences, and events.” R1 adds: “We did not proceed with a technology selection process, but rather a partner proposal.” R3 supports: “In the absence of such an evaluation, the PTR encountered challenges related to the compatibility and integration of the chosen technology.” A more thorough and structured selection would have ensured better integration and sustainability.

For the ninth step, the deployment and implementation of new technologies, the PTR experienced various delays and interruptions, particularly due to insufficient planning and integration problems. R2 explains: “Our main problem lay in the PTR’s specifications, which lacked details on the tasks to be accomplished and the management of spare parts.” R4 specifies: “We focused on objectives without planning the details of implementation or including a verification period.” Furthermore, R5 mentions: “Since the supplier is based in another province, on-site travel was rare, and requests had to go through the CEO, lengthening response times.” Finally, R3 insists: “We had not planned who would be responsible in case of breakdown or additional costs, which leads us to consider abandoning the technology.” These testimonies underline the need for rigorous planning, post-deployment verification, and clear technical responsibilities.

The tenth step, the evaluation of digital transformation, was insufficiently implemented at the PTR. R5 emphasizes: “No evaluation or monitoring was carried out by the PTR to assess the expected results […] any change or visualization must go through the supplier and obtain their authorization.” R3 adds: “Since the departure of the PTR agent in charge of the project, no one has been monitoring the indicators or data for this project.” Furthermore, R6 specifies: “No one monitors the data collected by the sensors; no analysis or use of this data is made by the PTR. […] although these sensors are installed on the port, their use and ownership rights are held by the supplier.” The lack of monitoring and access to data restricted the port’s ability to fully benefit from the project’s lessons and to measure performance effectively.

Overall, the case analysis made it possible to assess the relevance of the ten steps and to highlight discrepancies between the theoretical roadmap and a practical field experience toward the smart port, thereby generating concrete lessons on how the proposed roadmap should be adapted to field specificities.

5.2. Second Part: Proposed Refinements to the Roadmap

Refinements of the port’s digital transformation roadmap can be derived from the analysis of the truck traceability implementation project in the case study. These adjustments aim to improve the effectiveness and alignment of digital transformation initiatives with operational realities and specific challenges encountered in the field. Table 2 synthesizes, for each step of the theoretical roadmap, the main implementation issues observed at the PTR, the corresponding refinements, and the expected outcomes.

Table 2.

Proposed Refinements to the Theoretical Roadmap.

Table 2 operationalizes the theoretical roadmap presented in Figure 2 by confronting it with empirical evidence from the PTR case study. Each step of the initial roadmap is thus revisited in light of observed field challenges and gaps, and specific refinements are proposed to strengthen its practical applicability. This process transforms the roadmap from a purely literature-based conceptual sequence into a more robust and actionable framework. By linking each adjustment directly to the corresponding step of the theoretical roadmap, the table clarifies how the latter evolves to better address real operational constraints such as resource stability, stakeholder engagement, and technology integration while preserving the original structure.

6. Discussion

Analysis of existing methodological frameworks highlights recurring limitations in terms of generalization, operationalization, and adaptation to port environments. Models such as those proposed by [5,7,18,45] offer valuable building blocks, particularly around maturity assessment and technological deployment, but they tend to remain either diagnostic, technology driven, or insufficiently explicit regarding governance, stakeholder coordination, and investment prioritization. The roadmap proposed in this article seeks to address these gaps by moving beyond a simple maturity assessment toward a detailed sequence of ten steps that combines strategic planning, technology selection and implementation, and systematic monitoring of transformation. In contrast to previous approaches, which largely focus on technological capabilities, the proposed framework explicitly integrates data governance mechanisms and stakeholder engagement as central dimensions of the transition process. This structuring supports a progressive and better-controlled adoption of digital solutions, while allowing adaptation to the specific characteristics of port infrastructure and resource constraints.

The retrospective experimentation at the PTR reinforces and refines this contribution. By confronting each step of the roadmap with practices observed in an advanced technology deployment project, the case study confirms the relevance of key stages such as awareness, maturity diagnosis, gap analysis, and post-deployment evaluation, but also reveals critical shortcomings when these stages are absent or weakly implemented. For example, the lack of a formal maturity assessment, the limited early involvement of terminal operators, the opportunistic selection of a technological partner, and the absence of structured performance monitoring all led to delays, integration issues, and reduced control over data. The adjustments proposed in Table 2 translate these empirical findings into operational refinements for each step of the proposed roadmap, thereby transforming the latter from a purely theoretical construct into a more robust and actionable framework grounded in field realities. In this sense, the roadmap can be interpreted, in a design science perspective, as an artifact that iteratively evolves through the confrontation between prescriptive principles and contextual constraints.

From a managerial and organizational change perspective, the results confirm that port digital transformation cannot be reduced to isolated technology projects. It requires clear governance arrangements, rigorous planning, and proactive stakeholder management. Strategic alignment emerges as a central challenge, calling for explicit prioritization of investments and structured sequencing of initiatives according to organizational capabilities, risk exposure, and interoperability requirements. Effective governance, in this context, relies on a structured decision-making framework that clarifies roles and responsibilities, supports coordination between internal and external actors, and formalizes the rules governing data access, ownership, and sharing. Stakeholder involvement is likewise a key success factor, which demands transparent communication, awareness-raising mechanisms, and training programs designed to reduce resistance and build trust in new tools.

The proposed roadmap also carries policy and sustainability implications. By embedding maturity diagnosis, data governance, and performance indicators into a single structure, it offers public authorities a reference for assessing and supporting port digitalization programs. The emphasis on traceability, interoperability, and monitoring of operational and environmental indicators aligns with international sustainability agendas, in particular the United Nations SDGs related to industry, innovation, and infrastructure (SDG 9), sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11), responsible consumption and production (SDG 12), climate action (SDG 13), and partnerships for the goals (SDG 17) [56]. The proposed roadmap is thus not only a port’s modernization decision support tool, but a structured lever for integrating operational efficiency, economic performance, and environmental responsibility within a unified transformation trajectory. At the same time, the lessons drawn from a single case of a medium-sized port should be seen as exploratory, calling for further validation across diverse port profiles and for the integration of quantitative performance indicators in future research.

7. Conclusions

This study aimed to propose a comprehensive roadmap for the digital transformation of ports, based on a synthesis of a significant corpus of the scientific literature and on empirical insights from a field experiment. The literature review highlighted that, despite the existence of several methodological frameworks to support the digital transition of ports [5,7,18,45], these approaches present recurrent limitations in terms of operationalization, data governance, and adaptability to port realities. In particular, no unified model simultaneously integrates a structured assessment of digital maturity, a progressive technological implementation strategy, and explicit mechanisms for stakeholder management.

Methodologically, this research is based on a dual approach. First, a systematic literature review made it possible to structure a ten-step roadmap that combines maturity diagnosis, gap analysis, technology selection, deployment, and evaluation. Second, an empirical experimentation was carried out through a retrospective case study at the PTR. This combination allowed the theoretical roadmap to be confronted with field realities and helped identify discrepancies between state-of-the-art methodological recommendations and their effective implementation in a medium-sized port context.

The results of the case study revealed several shortcomings in the digital transformation process followed by the studied port. The absence of structured planning, formal maturity assessment, and clear digital governance led to organizational challenges, particularly regarding stakeholder engagement, technology selection, and data management. These findings provide preliminary support for the relevance of the proposed roadmap to structure port digital transition and to guide managers in sequencing initiatives, clarifying roles, and formalizing data-governance rules. They also motivated refinements to the initial model, especially concerning stakeholder involvement, continuity of project teams, and the formalization of performance monitoring.

This study has limitations that open avenues for future research. The empirical validation relies on a single case, centered on a specific technology within a medium-sized Canadian port, which limits the diversity of empirical findings and thus proposed adjustments. Moreover, the analysis is primarily qualitative and does not include systematic quantitative performance indicators to measure changes in efficiency, competitiveness, or environmental impact. Future work should therefore test the adaptability of the roadmap on a larger sample of ports with diverse governance models, sizes, and technological profiles, and should integrate maturity indices and operational, economic, and environmental metrics to quantify the effects of digital transformation.

To succeed in their digital transformation, ports must adopt an integrated approach combining strategic planning, continuous evaluation, and adapted governance, so that technological innovations are aligned with the imperatives of competitiveness, sustainability, and operational efficiency in the maritime sector. In this perspective, the proposed roadmap should be viewed as a structured and evolving decision support tool, offering ports and public authorities a reference framework to design, steer, and progressively improve in their digital transformation and digitalization programs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.B., J.-F.A. and P.F.; methodology, B.B., J.-F.A., P.F. and V.A.; software, B.B.; validation, B.B., and P.F.; formal analysis, B.B.; investigation, B.B. and V.A.; resources, B.B.; data curation, B.B.; writing—original draft preparation, B.B.; writing—review and editing, B.B., J.-F.A., P.F. and V.A.; visualization, B.B., J.-F.A., P.F. and V.A.; supervision, J.-F.A. and P.F.; project administration, J.-F.A.; funding acquisition, J.-F.A. and P.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially supported by Mitacs and the Port of Trois-Rivières Authority.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study by the Institutional Review Board due to the non-interventional nature of the research, its focus on organizational processes and managerial practices, the exclusive involvement of professional stakeholders in their official roles, and the absence of sensitive personal data.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to confidentiality, privacy, and ethical restrictions associated with the qualitative interviews and the case study context. The data were collected under conditions that do not allow public sharing.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the collaboration of the Canadian port as well as all the respondents in the case study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- DNV. Maritime Forecast to 2050; DNV: Oslo, Norway, 2023; Available online: https://www.dnv.com (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- CNUCED. Étude sur les transports maritimes 2023 (Review of Maritime Transport 2023). In Proceedings of the Conférence des Nations Unies sur le Commerce et le Développement, Geneva, Switzerland, 20–23 October 2025; Available online: https://unctad.org/publication/review-maritime-transport-2023 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Musée National de la Marine. À Quoi S’attendre en 2050 Pour le Transport Maritime Mondial? Musée National de la Marine: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Belmoukari, B.; Audy, J.-F.; Forget, P. Smart port: A systematic literature review. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2023, 15, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boullauazan, Y.; Sys, C.; Vanelslander, T. Developing and demonstrating a maturity model for smart ports. Marit. Policy Manag. 2022, 50, 447–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaś, A. Smart port as a key to the future development of modern ports. TransNav Int. J. Mar. Navig. Saf. Sea Transp. 2020, 14, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Nascimento Dominguez, G.; Gorges, S.C.; Silva, V.M.D. Roadmap for implementing smart practices at seaports and terminals. Rev. Eletrônica Estratégia Negócios 2022, 15, 73–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlan, V.; Sys, C.; Vanelslander, T. How port community systems can contribute to port competitiveness: Developing a cost–benefit framework. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2016, 19, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PierNext. How the Port of Hamburg uses AI to optimize traffic flows. PierNext. Available online: https://piernext.portdebarcelona.cat (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Jun, W.K.; Lee, M.-K.; Choi, J.Y. Impact of the smart port industry on the Korean national economy using input–output analysis. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2018, 118, 480–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notteboom, T.; Rodrigue, J.P. Maritime container terminal infrastructure, network corporatization, and global terminal operators: Implications for international business policy. J. Int. Bus. Policy 2022, 6, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz-Reiter, B.; Windt, K.; Kolditz, J.; Böse, F.; Hildebrandt, T.; Philipp, T.; Höhns, H. New concepts of modelling and evaluating autonomous logistic processes. In Proceedings of the 2004 IFAC Conference on Manufacturing, Modelling, Management and Control, Athens, Greece, 21–22 October 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Adolf, K.Y.N.; Liu, J.J. Port-Focal Logistics and Global Supply Chains, 1st ed.; Palgrave Macmillan London: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Banque Mondiale. Accélérer la Digitalisation: Actions Critiques Pour Renforcer la Résilience de la Chaîne D’approvisionnement Maritime; Banque Mondiale: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Almeida, F. Challenges in the digital transformation of ports. Businesses 2023, 3, 548–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Économique et Sociale pour l’Asie et le Pacifique (CESAP). Asia-Pacific Trade Facilitation Report 2021: Supply Chains of Critical Goods; Nations Unies: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.unescap.org (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Philipp, R. Digital readiness index assessment towards smart port development. Sustain. Manag. Forum 2020, 28, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundación Valenciaport. Smart Ports Manual: Strategy and Roadmap; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Available online: https://publications.iadb.org/en/smart-ports-manual-strategy-and-roadmap (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Buiza-Camacho-Camacho, G.; del Mar Cerbán-Jiménez, M.; González-Gaya, C. Assessment of the factors influencing on a smart port with an analytic hierarchy process. Revista DYNA 2016, 91, 498–501. [Google Scholar]

- Molavi, A.; Lim, G.J.; Race, B. A framework for building a smart port and smart port index. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2020, 14, 686–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, A.; Nemeth, T.; Sihn, W. Roadmapping towards industrial digitalization based on an Industry 4.0 maturity model for manufacturing enterprises. Procedia CIRP 2019, 79, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilig, L.; Lalla-Ruiz, E.; Voß, S. Digital transformation in maritime ports: Analysis and a game theoretic framework. Netnomics 2017, 18, 227–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klar, R.; Fredriksson, A.; Angelakis, V. Digital twins for ports: Derived from smart city and supply chain twinning experience. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 71777–71799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagha, A.; Ben Daya, B.; Audy, J.-F. Assessment of greenhouse gas emissions from heavy-duty trucking in a non-containerized port through simulation-based methods. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, P.; Antonelli, S.; Tardo, A. C-Ports: A proposal for a comprehensive standardization and implementation plan of digital services offered by the “Port of the Future”. Comput. Ind. 2021, 134, 103556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, E.; Rüsch, M. Industry 4.0 and the current status as well as future prospects on logistics. Comput. Ind. 2017, 89, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministère de la Transition Écologique. Stratégie Nationale Portuaire; Gouvernement Français: Paris, France, 2021. Available online: https://www.ecologie.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/publications/21002_strategie-nationale-portuaire.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Marsh. Numérisation dans les ports et terminaux: Les avancées technologiques augmentent le risque. Marsh Insights 2022. Available online: https://www.marsh.com/fr-ca/industries/marine/insights/digitalization-in-ports-and-terminals-technology-advances-bring-increased-risk.html (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gregor, S.; Hevner, A.R. Positioning and presenting design science research for maximum impact. MIS Q. 2013, 37, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieringa, R. Design Science Methodology for Information Systems and Software Engineering; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, G.A. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qual. Res. J. 2009, 9, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Douaioui, K.; Fri, M.; Mabrouki, C.; Semma, E.A. Smart port: Design and perspectives. Int. J. Eng. Res. Afr. 2018, 35, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stich, V.; Zeller, V.; Hicking, J.; Kraut, A. Measures for a successful digital transformation of SMEs. Procedia CIRP 2020, 93, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, A.; Hatiboglu, B.; Bildstein, A.; Bauernhansl, T. Industrie 4.0 roadmap: Framework for digital transformation based on the concepts of capability maturity and alignment. Procedia CIRP 2018, 72, 973–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deniaud, I.; Marmier, F.; Michalak, J.L. Méthodologie et outil de diagnostic 4.0: Définir sa stratégie de transition 4.0 pour le management de la chaîne logistique. Logistique Manag. 2020, 28, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotrino, A.; Sebastián, M.; González-Gaya, C. Industry 4.0 roadmap: Implementation for small and medium-sized enterprises. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häring, K.; Pimentel, C.; Teixeira, L. Industry 4.0 implementation in small- and medium-sized enterprises: Recommendations extracted from a systematic literature review with a focus on maturity models. Logistics 2023, 7, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digalwar, A.K.; Singh, S.R.; Pandey, R.; Sharma, A. Industry 4.0 implementation: Evidence from Indian industries. In Transfer and Diffusion of IT; Dwivedi, Y.K., Janssen, R., Rana, N.P., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaltini, M.; Terzi, S.; Taisch, M. Development and implementation of a roadmapping methodology to foster twin transition at manufacturing plant level. Comput. Ind. 2024, 154, 104025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Cancelas, N.; Molina Serrano, B.; Soler-Flores, F.; C-Majolero, N. Diagnosis of the digitalization of the Spanish ports: End-to-end tool. World Sci. News 2021, 155, 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- Jeevan, J.; Selvaduray, M.; Mohd Salleh, N.H.; Ngah, A.H.; Zailani, S. Evolution of Industrial Revolution 4.0 in seaport system: An interpretation from a bibliometric analysis. Aust. J. Marit. Ocean Aff. 2022, 14, 229–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, O.L. Modelos de madurez digital: ¿En qué consisten y qué podemos aprender de ellos? Boletín Estud. Económicos 2016, 71, 573–592. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, R.C.; Martinho, J.L. An Industry 4.0 maturity model proposal. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2020, 31, 1023–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faheem, M.; Shah, S.B.H.; Butt, R.A.; Raza, B.; Anwar, M.; Ashraf, M.W.; Ngadi, M.A.; Gungor, V.C. Smart grid communication and information technologies in the perspective of Industry 4.0: Opportunities and challenges. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2018, 30, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchini, F.; Oleskow-Szlapka, J.; Ranieri, L.; Urbinati, A. A maturity model for Logistics 4.0: An empirical analysis and a roadmap for future research. Sustainability 2020, 12, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]