Abstract

Background: This paper presents an analysis and a structured framework for improving inventory accuracy in an automotive factory, considering the current context of global disruptions. In 2023, the company recorded 20,340 inventory adjustments (1695 per month) and a 0.24% monthly net value discrepancy (EUR 256,594 YTD), with a baseline absolute discrepancy of 2.21% of sales. The project aimed to reduce adjustments to below 700 per month and the net value discrepancy to 0.1%. Methods: The research followed the Six Sigma methodology’s Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve and Control (DMAIC) phases, integrating Root Cause Analysis (RCA) and Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) to enhance inventory accuracy in manufacturing operations. Results: Implementation significantly improved inventory accuracy: monthly adjustments decreased from 1695 to 971, the highest RPN was reduced from 576 to 144, and the absolute discrepancy-to-sales ratio stabilized at 0.98% (a 56% improvement). Financial variance was reduced to EUR 1948.10 in Q4 2024, while organizational discipline, role clarity and process control also increased. Conclusions: The integrated DMAIC–RCA–FMEA framework proved effective and replicable, enabling systematic identification of root causes, targeted corrective actions and sustainable KPI-driven improvements. The results demonstrate a scalable approach to inventory optimization that supports operational resilience and supply chain performance.

1. Introduction

Maintaining optimal inventory levels is critical for operational efficiency and cost-effectiveness in the highly competitive and dynamic automotive industry. Robust inventory management techniques are necessary due to the increasing complexity of supply chains and the shifting demands of the market. While low inventory can result in production disruptions, delayed delivery and dissatisfied customers, excessive inventory ties up capital and increases holding expenses. Balancing these extremes remains a persistent challenge for organizations.

The present study used Six Sigma methodology to optimize inventory management in the automotive sector, applying the DMAIC cycle to diagnose process variability, eliminate non-value-added activities and establish robust control mechanisms that enhance accuracy, responsiveness and operational efficiency. Six Sigma uses effective analytical and statistical tools and methods [1,2,3], like DMAIC, characterized by five steps, namely Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve and Control [4,5,6]. The DMAIC structure is further reinforced through the integration of Root Cause Analysis (RCA) and Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA), two complementary diagnostic tools widely used in quality and reliability engineering. RCA supports the Analyze phase by systematically identifying underlying process deviations rather than superficial symptoms, enabling evidence-based prioritization of corrective actions [7,8]. In parallel, FMEA provides a proactive, structured assessment of potential failure modes, their causes, effects and associated risks, allowing teams to quantify the severity, occurrence and detectability of each issue and to calculate the Risk Priority Number (RPN) for decision-making [9,10]. Incorporating RCA and FMEA within the DMAIC cycle strengthens the robustness of process improvement initiatives, ensures early detection of inefficiencies in inventory workflows, and enhances the reliability of the redesigned system, particularly in high-precision sectors such as automotive manufacturing.

Inventory accuracy, defined as the alignment between recorded and physical stock, is a critical factor in manufacturing supply chains. Ineffective inventory management and discrepancies in demand information can result in stockouts, overstocking and lost sales, which not only tie up valuable capital and increase operating costs but also undermine customer satisfaction, trust and overall profitability [11,12]. Accurate inventory management provides a range of strategic and operational benefits across the supply chain. First, it significantly enhances customer satisfaction, as products are delivered on time and in accordance with demand, reducing the risk of backlogs or delays caused by inventory discrepancies [13]. Second, it improves operational efficiency by enabling production processes to proceed as scheduled, eliminating the time and effort spent locating misplaced components [14].

Furthermore, effective inventory management contributes to cost reduction by minimizing storage and transportation expenses, optimizing stock turnover ratios and refining production processes [15].

Despite advancements in literature, a clear gap remains regarding the combined application of DMAIC, RCA and FMEA to address inventory accuracy in manufacturing, particularly with respect to detailed root cause identification, risk prioritization and actionable improvement plans. By using a dedicated case study in an automotive company—combining DMAIC with RCA for root-cause detection and FMEA for risk prioritization—the present research provides empirical evidence that goes beyond defect reduction and targets inventory accuracy as a key performance dimension.

The novelty of this study lies in several key aspects. First, it integrates DMAIC, Root RCA and FMEA into a single framework, whereas previous research has often applied these methods separately. Second, the study adopts a practical case-based approach that connects theoretical quality management tools with their real-world application in inventory management, thereby providing a direct contribution to industry practice in the case of an emerging market. Third, by introducing a risk-based prioritization of inventory discrepancies, the research ensures that improvement efforts are directed toward the most critical causes of inefficiency. Fourth, the study contributes a comprehensive action plan that moves beyond diagnostic analysis and provides concrete, implementable steps for manufacturing firms. Finally, the study highlights inventory accuracy as a driver of production continuity and timely customer deliveries, emphasizing the strategic role of quality tools in enhancing operational efficiency and business performance—an area underexplored in the literature.

This study contributes to the literature by providing insights into improving inventory levels, reducing costs, minimizing stock discrepancies and preventing disruptions in client deliveries, thereby enhancing operational efficiency. By focusing on inventory accuracy and streamlining the processes within the production and logistics framework, the study offers practical insights for maintaining continuous production flow and ensuring timely deliveries to customers, which ultimately contributes to cost savings and enhanced operational efficiency.

The results suggest that the integrated DMAIC–RCA–FMEA approach effectively improves inventory accuracy and supply chain performance by identifying and prioritizing root causes, reducing inventory adjustments and RPN values, stabilizing discrepancy levels and strengthening organizational capabilities in ways that support resilient, human-centric Industry 5.0 practices.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Six Sigma DMAIC Framework and Applications

Six Sigma, a data-driven methodology, provides a formal framework for identifying inefficiencies, reducing waste and strengthening decision-making processes, aiming to minimize process variability and optimize operational performance. Six Sigma is a systematic, powerful technique to continuously improve the processes that uses effective analytical and statistical tools and methods [1,2,3]. In contemporary practice, this often involves the interplay between Six Sigma and Lean principles, where the objective is not only to reduce defects but also to streamline inventory flows and cost reduction [4,5,16]. One approach to the Six Sigma methodology is DMAIC, characterized by five steps, namely Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve and Control [4,5,6]. Each step is a collection of actions and procedures meant to lead a project from problem identification to process improvement. The DMAIC methodology identifies, analyzes and eliminates the root causes of process defects, aiming to improve production processes by reducing non-compliant products and production costs, thereby enhancing productivity and achieving higher quality outcomes [6,17,18,19].

A systematic application of DMAIC in automotive companies recurrently begins with the Define cost, where process inefficiencies and key sources of inventory-related costs are clearly outlined. Subsequently, relevant metrics—such as stock turnover rates, supplier lead times and defect rates—are measured to quantify the scope and impact of these inefficiencies. Organizations then proceed to the Analyze phase, in order to treat and highlight the root causes, which will allow the optimal solutions to be generated [20]. The Improve phase emphasizes the adoption of tailored interventions, such as safety stock optimization, demand-driven replenishment or enhanced forecasting techniques, which demonstrably reduce inventory costs while maintaining or improving service levels [21]. Crucially, the Control phase ensures that the improvements are sustained over time.

Automakers employ tools like Statistical Process Control (SPC) and FMEA to monitor processes and rapidly detect deviations from target inventory levels, thereby maintaining agility and responsiveness in their supply chains. Case studies document that the combined implementation of Lean, Six Sigma and real-time analytics has led to measurable gains in productivity, substantial reductions in defect rates and notable cost savings in high-volume automotive manufacturing contexts [4].

The Six Sigma methodology, using the DMAIC approach, has been applied in various studies, with companies as case studies focusing on process improvement.

Jou et al. applied Six Sigma methodology in an automotive manufacturing company to reduce the rejection rate [3]. Numerous measures for improvement were put into place, including better inspection techniques, supplier reselection, hiring more staff, training employees and more. Therefore, the Six Sigma level increased from 5.11 to 5.44 in five months.

Mittal et al. [22] presented a case analysis of implementing the Six Sigma DMAIC methodology to reduce the rejection rate of rubber strips produced by a company from India. The implementation of a single Six Sigma project solution resulted in an improvement in the sigma level from 3.9 to 4.45 within three months [22].

Gijo et al. [23] used DMAIC methodology to address process capability-related issues in an automotive parts manufacturing company. The approach significantly enhanced process capability, increasing the first-pass yield from 85% to 99.5% [23].

Singh and Lal [24] identified some improvements in an automobile manufacturing industry specializing in engine mufflers, using Six Sigma methodology. The rejection rate in muffler production dropped from 8.21% to 4.81%, the Sigma level increased from 2.89 to 3.16, and process capability improved from 91.73% to 95.19% [24].

The integration of Lean and Six Sigma (LSS) has been proposed as an effective approach to enhance supply-chain performance beyond simple defect reduction. In a recent work, the author outlines how LSS can systematically address inefficiencies in procurement, production, inventory management and distribution, yielding gains in operational efficiency, waste reduction and customer satisfaction [25].

2.2. Inventory Accuracy and Quality Tools in Supply Chain Management

Inventory accuracy, which measures the alignment between recorded and actual stock levels, is a key determinant of efficiency in manufacturing supply chains. Inventory accuracy has been extensively studied in supply chain management due to its impact on operational performance. Six Sigma tools can be adapted to optimize inventory, uncover root causes of overstocking or inefficient stocking policies and improve alignment between actual and recorded stock [26].

Shabani et al. [27] found that discrepancies between recorded and actual inventory levels significantly affect store-level performance and that reducing these inaccuracies can enhance operational efficiency and improve resource allocation.

Similarly, DeHoratius et al. [14] reported that 65% of inventory records in a sample of 37 stores were inaccurate, with substantial variation across product categories and stores. They identified factors such as inventory auditing that mitigate inaccuracies and store complexity and distribution structure that exacerbate them. Kök and Shang [28] further highlighted the financial implications of inventory inaccuracies, including increased holding costs and lost sales, underscoring the importance of designing processes and planning tools that explicitly account for inventory record inaccuracy.

The DMAIC methodology, a Six Sigma framework, is widely recognized for process improvement in manufacturing [29]. DMAIC has proven effective in identifying root causes of process issues [20] and implementing sustainable solutions in complex systems [22].

RCA is a systematic process used to identify the underlying causes of problems, often employing tools like the Ishikawa (fishbone) diagram to categorize causes into thematic areas such as manpower, methods, systems and materials [30]. RCA is a foundational step in DMAIC, enabling teams to move beyond symptoms to address the root issues driving inefficiencies [31]. FMEA complements RCA by prioritizing risks based on their RPN, allowing organizations to systematically identify and address the most critical potential failures [32]. By combining FMEA with RCA, companies can both uncover root causes and evaluate the severity, occurrence and detectability of each failure mode, ensuring more effective risk mitigation and process improvement strategies. FMEA has been applied in supply chain contexts to mitigate risks, such as inventory inaccuracies, unexpected costs and extended lead times, providing a systematic approach to identify, prioritize and address potential failures in order to enhance supply chain reliability and performance [33].

The integration of machine learning techniques has also been shown to enhance demand forecasting accuracy and optimize inventory levels, leading to improved operational performance [34].

From a strategic perspective, accurate inventory records improve supply chain management, allowing for more precise purchasing and early detection of issues such as supplier delays [35]. Accurate records help upstream and downstream partners coordinate effectively, reduce variability in orders and mitigate the risk of stockouts or excess inventory, ultimately enhancing overall supply chain performance.

In addition, robust inventory control contributes to fraud detection by increasing traceability and reducing opportunities for internal misappropriation [36]. Lastly, accurate records support regulatory compliance, providing the documentation necessary for successful external audits and meeting legal standards [37].

Most empirical studies using DMAIC or Lean Six Sigma focus on defect reduction, process variation, or scrap rates, rather than inventory accuracy or inventory value discrepancies. For example, the automotive assembly line case by Priya et al. [38] applied DMAIC and RCA to reduce defects and non-value-added activities, achieving a significant drop in defect ratio and work-time waste; however, inventory aspects were not addressed.

Few studies combine RCA with FMEA (or other risk-prioritization tools) within a DMAIC project to systematically identify, prioritize and mitigate risk sources affecting inventory accuracy, such as demand fluctuations, supply variability or process inefficiencies. Even the prominent LSS–Supply Chain Management literature reviews emphasize overall supply-chain performance improvement but rarely detail an integrated RCA and FMEA implementation for inventory control [25].

3. Materials and Methods

The research problem addressed in this study concerns the high frequency of inventory adjustments and discrepancies in the automotive supply chain, which lead to inefficiencies and financial losses. The present study uses the Six Sigma methodology, specifically the DMAIC framework combined with RCA and FMEA, to optimize inventory management by identifying root causes, prioritizing risks and implementing targeted corrective actions, thereby improving accuracy and reliability across the material flow from incoming to delivery warehouses. A schematic diagram of the research methodology is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the presented study.

3.1. Case Study Company

The company used for the case study is a Tier-1 automotive electronics manufacturer located in an emerging market. In 2024, it employed 1894 people, of whom 70–80% (approximately 1350–1500) work in direct production roles typical of high-volume automotive assembly plants. As a Tier-1 supplier, it delivers components directly to vehicle assembly lines of major OEMs and other Tier-1 partners. The company manages over 1200 different product variants and recorded annual sales of approximately EUR 210 million in 2024. Inventory management and logistics roles represent 5–7% of non-production staff (approximately 100 people) and are responsible for warehousing, material flow coordination and supply chain accuracy across incoming, pre-production, assembly and delivery warehouses. Like many large automotive suppliers, the company has historically experienced steadily rising inventory levels and frequent adjustments, reducing cash flow, occupying storage space and increasing capital costs. In 2023, inventory was adjusted 20,340 times, indicating lower-than-desired accuracy and motivating the Six Sigma improvement project described in this paper.

Inaccurate inventory leads to damaged customer relationships, disrupted operations, reduced productivity, increased costs and other adverse effects. The main objective of the study was to reduce the Inventory Discrepancy net value and to reduce the number of adjustments.

3.2. Research Method

This study employed a hybrid methodology that integrates DMAIC, RCA and FMEA. The combination was specifically selected to address the volatile operational characteristics of the automotive sector in emerging markets. Frequent shocks in component demand and supply, unstable process conditions and rapid fluctuations in engineering requirements necessitated a flexible yet structured analytical framework. The hybrid model provides the robustness of DMAIC, the diagnostic depth of RCA and the risk-prioritization capability of FMEA. This study adopted a case study approach, a method that enables an in-depth exploration of complex processes within their real-world context [39]. Data were collected from the automotive factory’s internal reports, including financial statements, project charters, phase-specific documentation and an FMEA table.

The research used DMAIC methodology to reduce adjustments to fewer than 700 per month and the net value discrepancy to 0.1%. The project scope covered the material flow from the incoming warehouse (WH-Incoming) to the delivery warehouse (WH-Delivery), covering molding, painting, clean room operations, surface-mount technology (SMT) and assembly processes. In the Define phase (March–April 2024), the project scope was established, and material flows were mapped for Warehouse, Pre-Production, Assembly and SMT areas, aligning stakeholders for data-driven analysis. During the Measure phase (April–June 2024), baseline data were collected through documentation checks, inventory audits and verification of system versus physical stock, providing a foundation for analysis. In the Analyze phase (June–September 2024), RCA with Ishikawa diagrams identified the main sources of discrepancies, which were then prioritized using Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA). Severity, occurrence and detectability were assessed to calculate RPN, guiding the focus of improvement actions. The Improve phase (September–November 2024) implemented corrective actions such as BOM updates, process refinements and staff training, reducing inventory adjustments and achieving significant RPN decreases. Finally, in the Control phase (November 2024–March 2025), standardized processes, dashboards and a Control Plan ensured the sustainability of improvements, with ongoing KPI monitoring to maintain inventory accuracy and process reliability.

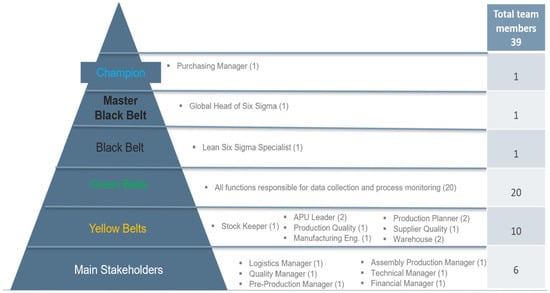

Figure 2 is a visual representation of a project team’s organizational structure, often used in Lean Six Sigma projects to improve processes, reduce waste or enhance quality. The pyramid format illustrates hierarchy, with each level representing a role with specific responsibilities, authority and involvement in the project. The structure ensures clear accountability and efficient collaboration across the team. The Champion ensures the project aligns with the company’s goal of improving product quality. The Master Black Belt provides expert guidance on Lean Six Sigma methodology. The Black Belt leads the team in analyzing defect data and implementing solutions. Green Belts collect data, map processes and test solutions in their departments. Yellow Belts assist with smaller tasks, like documenting results. Stakeholders ensure the changes meet their needs, while additional roles like the Production Planner adjust schedules to accommodate the changes. The pyramid also highlights the decreasing level of technical expertise in Lean Six Sigma as moving down (from Master Black Belt to Yellow Belt), but an increasing number of people are involved, showing the collaborative nature of such projects.

Figure 2.

Project Team—role and responsibility pyramid.

As detailed in Figure 2, the project was supported by a robust, multi-disciplinary team totaling 39 members. This team comprised a dedicated Black Belt, twenty Green Belts responsible for detailed data collection, ten Yellow Belts leading specific process improvements and six main Stakeholders (representing key managerial functions like Logistics, Quality and Production), ensuring comprehensive cross-functional commitment for successful implementation across the organization.

Data for the project were collected through a systematic and collaborative approach, primarily during the Define and Measure phases of the DMAIC framework. The Black Belts and Green Belts worked closely with the Production Planner and Supplier Quality, gathering quantitative and qualitative data from multiple sources. This included extracting historical production records and defect rates from the company’s manufacturing database, conducting time studies on the production floor to measure process cycle times and interviewing Main Stakeholders to understand pain points and customer requirements. Additionally, the team used process mapping sessions to identify inefficiencies and collected real-time data through observation and measurement tools, such as checklists and statistical sampling, ensuring a comprehensive dataset to analyze and drive process improvements.

4. Results

The project’s scope was clearly defined to ensure a focused approach. It encompassed activities related to material storage, handling and inventory processes, covering the flow from the Incoming Warehouse to the Delivery Warehouse. Based on the material flow through processes, all departments were analyzed: incoming warehouse, pre-production (molding, painting, clean room and surface-mount technology [SMT]), assembly production and delivery warehouse. For each department, a flowchart of the material process was created to identify where stock discrepancies could arise, and data were analyzed to determine the main contributors to the inventory discrepancies. However, the analysis excluded areas that were unrelated to inventory management, such as mechanical design, software development and customer-specific packaging. This well-defined scope ensured alignment with the project’s objectives while avoiding resource dilution.

Data were sourced from company financial reports (2023–2024), inventory adjustment records, process-specific documentation (e.g., Bill of Material (BOM) checks, material preparation logs) and an FMEA table. Quantitative analysis included tracking adjustments, net value discrepancies, cost variances and RPNs from the FMEA. Qualitative analysis involved identifying root causes through the Ishikawa diagram. Key performance indicators (KPIs) were defined to systematically monitor progress and evaluate inventory management performance. The used KPIs were net value reported to sales discrepancy, absolute value reported to sales discrepancy, frequency of stock adjustments and inventory accuracy. The net value reported to sales discrepancy reflects the percentage difference between positive and negative inventory values relative to total sales. The absolute value reported to sales discrepancy captures the total variation in reported values, irrespective of direction, also as a percentage of total sales. The frequency of stock adjustments measures how often inventory adjustments occur relative to the total number of purchase orders, indicating operational stability. Lastly, inventory accuracy evaluates the alignment between physical inventory counts and system records, expressed as a percentage, to assess data reliability and process integrity.

4.1. Define Phase

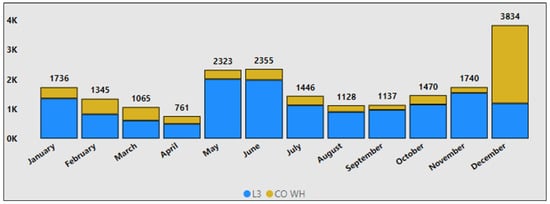

The Define phase started with problem description. At the end of 2023, the company recorded 20,340 inventory adjustments, with a monthly inventory net value-to-sales ratio of 0.24% and an absolute discrepancy of 2.21% of sales. These inaccuracies disrupted operations, increased costs due to overstocking, stockouts and delays, and negatively affected customer relationships. Figure 3 shows the evolution of inventory adjustments across 2023 for the two locations, L3 (blue) and CO WH (yellow).

Figure 3.

Adjustments number by month.

Adjustments peaked in May and June (2323 and 2355, respectively), suggesting operational disruptions or changes in inventory processes. After a decline during the summer months, with the lowest recorded in April (761), adjustment levels remained relatively stable from August to November. However, December showed a sharp spike to 3834 adjustments, primarily in CO WH, suggesting either end-of-year reconciliation efforts or major discrepancies. The variability across months and sites indicates potential inconsistencies in inventory accuracy or differences in control mechanisms, warranting further investigation.

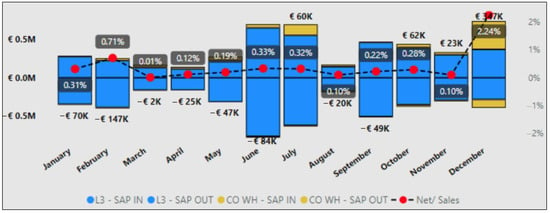

Figure 4 illustrates the monthly net value discrepancies from sales for two warehouses (L3 and CO WH), distinguishing between SAP (Systems, Applications and Products in Data Processing) IN and SAP OUT values.

Figure 4.

NET Value from Sales by month.

SAP IN represents goods receipts or other inbound operations recorded in SAP, such as material deliveries from suppliers, inter-warehouse transfers, returns from customers or the completion of internal production. These transactions increase the system-reported stock levels. Conversely, SAP OUT refers to goods issues, which include customer deliveries, material consumption for production, stock transfers out of a location or write-offs. These events decrease the stock quantity recorded in SAP. The analysis of SAP IN and SAP OUT enables the identification of discrepancies in inventory flows, highlighting potential mismatches between physical and system inventory levels.

As seen in Figure 4, most months exhibit minor discrepancies relative to total sales, with net/sales ratios staying below 1%. Slight increases occurred in February (0.71%) and July (0.32%), while December recorded the highest discrepancy both in absolute value (EUR 347K) and ratio (2.24%) due to an annual stock check. Negative discrepancies occurred in March (−EUR 2K), May (−EUR 47K) and June (−EUR 84K), suggesting potential underreporting or losses. In contrast, July and October show positive discrepancies (EUR 60K and EUR 62K, respectively), suggesting overreporting or unexpected gains. The December spike aligns with the increase in inventory adjustments, reflecting potential process inefficiencies, timing issues, or reporting misalignments that require root cause analysis. This trend may highlight process inefficiencies, timing issues in sales recognition or systemic reporting misalignments, warranting further root cause analysis and process control reinforcement.

Based on the analysis of baseline inventory data, including the number of adjustments, net value discrepancies and variations across months and locations, the project identified operational inefficiencies and inconsistencies that could affect customer service and costs. By defining a robust foundation through the project charter, milestones and measurable objectives, the Define phase set the stage for systematic improvements in the Measure phase and beyond.

4.2. Measure Phase

The Measure Phase serves as a critical step in the Lean Six Sigma framework, focusing on quantifying inventory inaccuracies and identifying key pain points within the material flow process. During this phase, comprehensive data collection and analysis were conducted to uncover the contributors to discrepancies, laying the foundation for targeted interventions in subsequent phases.

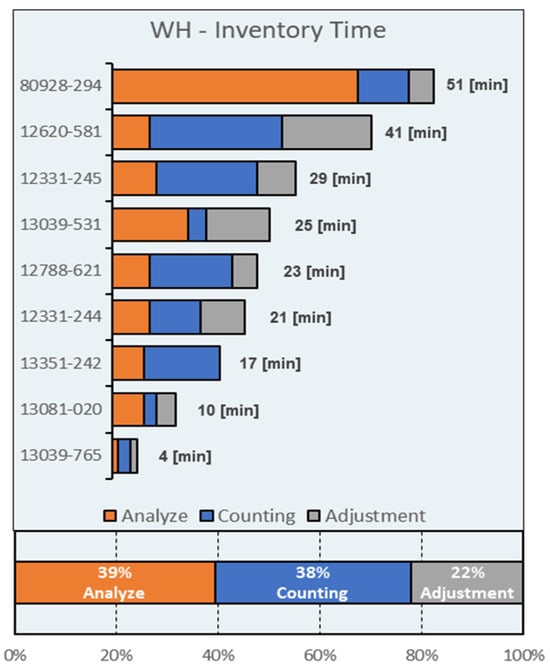

Data analysis identified significant inefficiencies across multiple operational areas. First, the time required to fulfill inventory requests was inconsistent, particularly between the warehouse and production lines, leading to operational delays. Figure 5 presents the processing time, divided among analysis, counting and adjustment activities. Total times range from 4 to 51 min, indicating significant variation in efficiency. Overall, 39% of time is spent on analysis, 38% on counting and 22% on adjustments, suggesting that the analysis phase is the main bottleneck and that process standardization could improve overall performance.

Figure 5.

WH—inventory time.

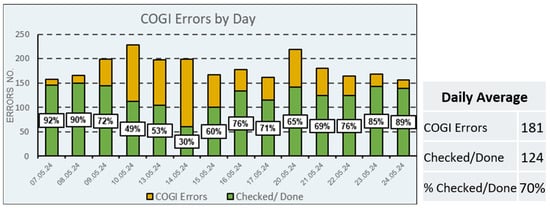

Additionally, SAP-related errors, referred to as Controlling Goods Issue (COGI) errors, were prevalent. These errors often disrupted workflows due to mismatches between system transactions and physical inventory, highlighting a critical area for process improvement. COGI errors by day can be seen in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

COGI errors by day.

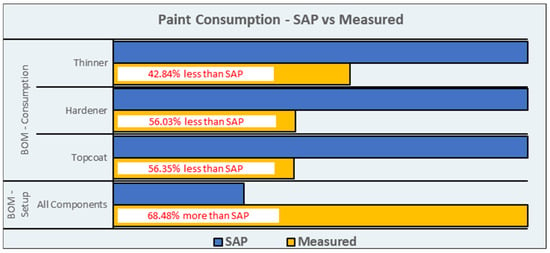

Further investigation into the Bill of Materials (BOMs) uncovered discrepancies between predefined material consumption quantities and actual usage. For example, machine setup and undesired events, such as equipment malfunctions, resulted in unreported material waste that was not accounted for in the SAP system. This issue compounded inventory inaccuracies and increased operational costs. For example, Figure 7 compares the paint consumption as recorded in the SAP system with the actual measured consumption. For production activities (BOM—Consumption), the measured consumption was significantly lower than the values recorded in SAP—by 42.84% for thinner, 56.03% for hardener and 56.35% for topcoat. In contrast, when considering all components together, the measured consumption is 68.48% higher than the value indicated in SAP. This issue requires further investigation, including a detailed review of measurement practices, SAP aggregation rules and consumption reporting procedures, to accurately determine its root cause. Hence, the need to improve BOM accuracy, strengthen reporting mechanisms and enhance traceability for non-standard consumption in order to achieve reliable inventory management.

Figure 7.

Paint consumption for AUC8D5 P/N’s: SAP and measured.

Labeling inconsistencies during incoming inspections, particularly when quantities were measured by weight rather than count, also contributed to inventory discrepancies.

A notable finding was the lack of standardized documentation for key inventory processes. Critical tasks such as scrap booking, production reporting and component recovery were either poorly documented or entirely missing. This gap hindered the ability to establish consistent workflows and further emphasized the need for process standardization.

The Measure phase identified pain points across the material flow, summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Measure phase findings—key pain points across material flow.

The data provided a quantifiable understanding of inefficiencies, enabling a focused approach to addressing root causes in the Analyze phase. By identifying these pain points, the Measure phase not only highlighted areas requiring immediate attention but also ensured that future interventions would be based on robust data-driven insights.

4.3. Analyze Phase

The Analyze phase was a pivotal step in identifying and addressing the root causes of inventory discrepancies. Through rigorous analysis and data-driven methodologies, this phase provided actionable insights into inefficiencies within the material flow and inventory processes.

4.3.1. Root Cause Analysis

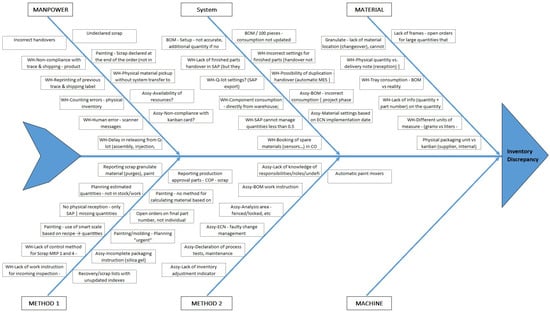

RCA was used to systematically explore potential causes of inventory inaccuracies, a structured tool that categorizes potential causes into thematic areas to facilitate thorough investigation [30]. Cross-functional teams from production, logistics and quality assurance collaborated in brainstorming potential causes based on the pain points summarized in Table 1. The RCA, using an Ishikawa diagram, identified 48 potential causes, categorized into Manpower (40%), Methods (23%), System (23%) and Materials (15%), which informed a FMEA. Analysis confirmed that human-related factors (Manpower: 40%) were the dominant cause of discrepancies. System and Method issues followed. The RCA findings, illustrated in the Ishikawa diagram (Figure 8), provided the crucial input for the FMEA, ensuring that the corrective actions targeted the highest-impact and highest-risk causes, thus maximizing the efficiency of the Improve phase.

Figure 8.

RCA diagram.

4.3.2. Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA)

The FMEA approach was applied to critical production and inventory subprocesses. This analysis identified potential defects, their causes and consequences, evaluated their risk priority and defined corrective measures aimed at reducing process variability and enhancing data accuracy. The methodology systematically quantified risks using three parameters—Occurrence, Severity and Detection—to calculate the RPN, which provided a measurable indicator of process reliability before and after improvement actions. The RPN is defined as the product of these three parameters: RPN = Severity (S) × Occurrence (O) × Detection (D).

Table 2 summarizes the RPN results for the top three failure modes identified and mitigated by the project.

Table 2.

RPN results for the top three failure modes.

The analysis began with the BOM—material consumption and setup process, where the system may record incorrect material quantities due to calculation errors or missing reviews after project transfers. The failure mode directly impacted inventory accuracy, generating an initial RPN of 576. The implementation of control measures—such as rechecking and adjusting material consumption in assembly and pre-production—reduced the RPN to 144. This significant decrease demonstrates the effectiveness of process verification and highlights the preventive impact of FMEA-driven corrective actions.

The second most critical area was the SAP MRP scrap percentage assignment, which showed an initial RPN of 432. Implementing a formal review of scrap percentages and training personnel on correct material consumption documentation reduced the RPN to 72. The third critical area, with an initial RPN of 384, was the trace shipping quantity discrepancy, where errors in final delivery quantities led to inventory inaccuracies. By introducing an automatic check of the palletizing system and enforcing clear roles and responsibilities, this risk was reduced to an RPN of 64.

Even though the initial severity was moderate, the improvement emphasizes the preventive nature of FMEA in maintaining process consistency. Overall, the analysis demonstrated that the structured use of FMEA provided a systematic foundation for identifying, evaluating and reducing process risks. The measurable decrease in RPN across all subprocesses indicated a strong correlation between targeted corrective measures and improved process reliability.

4.4. Improve Phase

The Improve phase marked a significant milestone in addressing the root causes of inventory discrepancies through targeted, data-driven interventions. Building upon the insights obtained during the Analyze phase, this phase centered on executing prioritized solutions and monitoring their impact on KPIs.

A total of 30 improvement actions were implemented, focusing on inefficiencies in material handling, documentation and system processes. These actions directly supported the project’s core objectives of reducing inventory adjustments and enhancing accuracy. Key interventions included the optimization of the BOMs, where material setup discrepancies were corrected across molding, painting and assembly processes to better align recorded and actual material usage. The improvement initiatives aimed to validate and align actual material consumption with the data recorded in the SAP system for every 100 produced parts. This process included granting controlled access rights to specific employees, allowing them to modify only consumption-related information, while also ensuring that personnel are properly trained and supported by the BOM team. The establishment of weekly BOM check meetings with key stakeholders institutionalized the review process, ensuring that BOM inaccuracies were identified and corrected proactively, thereby stabilizing material planning and consumption data. The creation of standardized documentation for BOM processes, including flow descriptions, work instructions and guidelines, represented an essential step in achieving procedural clarity and consistency. These documents explain the process of BOM modification and review, serving as reference materials for quality audits and employee training. Furthermore, improvements related to machine setup in the pre-production phase aimed to increase efficiency and precision. Management approval was required for any component removal from the BOM, and responsibilities for weighing and scrapping materials were clearly defined. The potential use of a Manufacturing Execution System was considered to ensure accurate tracking and integration of process data.

Additionally, smart scale technology was introduced into the painting processes, enabling the capture of critical parameters such as batch number, temperature, viscosity and expiration dates, thereby improving traceability and minimizing waste.

System enhancements addressed technical gaps within SAP, including improved database communication and error tracking to mitigate duplicate entries and erroneous stock adjustments. Manual tasks were also replaced by automation tools, eliminating high-risk methods such as estimation-based material handling and spreadsheet documentation.

Awareness and training initiatives supported the sustainability of these changes. A structured training plan equipped staff with essential inventory management skills, while clearly defined roles and responsibilities fostered accountability and discipline in daily operations. Training sessions were integrated into digital learning platforms such as SECOVA or Success Factors, reinforcing procedural compliance and knowledge standardization across departments.

Post-implementation data demonstrated measurable progress, as seen in Table 3.

Table 3.

Inventory performance summary: post-implementation metrics.

The number of inventory adjustments decreased from a baseline monthly average of 1695 to 971, with a target of 700. Similarly, the absolute value of inventory discrepancies, measured as a percentage of total sales, improved from a baseline of 2.21% to a final average of 0.98%, with a long-term target of 0.50%. While targets were not fully met, progress validates the effectiveness of the implemented actions.

In 2023, a total of 20,340 inventory adjustments were recorded, with a monthly net discrepancy value of 0.24%, equivalent to EUR 256,594 year-to-date. The highest monthly discrepancy occurred in September, reaching EUR 785,000, which represented 1.27% of the project’s total sales. These metrics highlighted persistent systemic challenges in data accuracy, process consistency and inventory tracking, reinforcing the need for ongoing improvements in subsequent DMAIC phases.

This phase emphasized the integration of advanced digital tools, reinforced system controls and comprehensive process standardization. These enhancements improved inventory accuracy while establishing a foundation for sustained process stability and long-term cost reduction.

4.5. Control Phase

The Control phase focused on ensuring the long-term sustainability of the improvements achieved during the Define, Measure, Analyze and Improve phases. The primary objective was to institutionalize the implemented changes, preventing a regression to previous levels of inventory inaccuracy. A key strategy involves developing and implementing a process mentoring program, establishing a formal system for transferring knowledge and best practices to new employees and current staff. This ensured that the operational proficiency gained during the project became an embedded organizational standard. Training continued during this phase, with periodic refresher sessions and new hires trained using updated materials. The control strategy emphasized the reinforcement of individual responsibility in inventory transactions, ensuring that all personnel understood their roles in maintaining data accuracy.

A Control Plan was formalized to define ownership, monitoring frequency and escalation paths for each critical inventory process. The plan included defined thresholds for acceptable performance and clear actions in case of deviations. Key metrics showed gradual improvement or sustained performance, confirming effective maintenance of process changes.

The action plan’s integration of DMAIC, RCA and FMEA provides a replicable model for manufacturing firms, aligning with [40] findings on risk prioritization in supply chain management. The focus on process standardization, real-time monitoring and training ensured sustained improvements, reinforcing operational efficiency and inventory accuracy. The entire DMAIC process, objectives and outcomes are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Task allocation across DMAIC phases for inventory accuracy improvement.

Through the structured approach of the Control phase, the organization was able to stabilize the gains realized in earlier phases, minimize the risk of regression and create a culture of continuous improvement in inventory management.

5. Discussion

The analysis highlighted several critical areas requiring immediate attention to address the root causes of inventory discrepancies. One key issue was the presence of documentation deficiencies, particularly missing or outdated work instructions for essential inventory tasks such as scrap booking and component recovery. These gaps contributed to inconsistent execution and poor traceability across processes.

Another major concern identified was process delays, especially in the implementation of engineering change notices and scrap setting adjustments. These delays worsened discrepancies by allowing outdated procedures to persist and hinder timely corrections. Systemic improvements were also identified as necessary. Among the recommendations were the introduction of password protection for printing systems to avoid duplicate entries and the enforcement of stricter quality control measures for operator handling. These steps aim to reduce system misuse and enhance data integrity.

The Analyze phase provided a structured identification and prioritization of root causes through effort–benefit assessment, ensuring that resources were directed toward high-impact corrective actions. The Improve phase exemplified the application of Lean Six Sigma principles to drive actionable change. Our findings align with [11,12], who emphasize the importance of inventory management in enhancing cost efficiency, reducing stockouts and overstocks, and improving overall business performance. By implementing targeted, high-impact solutions, the project team achieved significant improvements in inventory accuracy and addressed key process inefficiencies, reflecting the practical benefits highlighted in the literature. These improvements set the stage for the Control phase, in which full implementation and ongoing monitoring are maintained through updated standard operating procedures (SOPs), audit checklists and regular process reviews—an approach consistent with the control and standardization practices highlighted by [2].

Consistent with the findings of Rifqi et al. [20], who demonstrated the effectiveness of the DMAIC approach in structuring Lean Manufacturing initiatives and achieving significant process and financial improvements, the results confirm the method’s utility in systematically identifying root causes of inventory discrepancies, prioritizing improvement actions and implementing targeted solutions that enhance process accuracy and control.

The integration of DMAIC, RCA and FMEA for an automotive company in an emerging market provided a robust framework for addressing inventory discrepancies. The RCA revealed that human errors (40%) and procedural/systemic issues (23% each) were the primary drivers of discrepancies, aligning with [14], who identified human errors and system inaccuracies as key contributors to inventory inaccuracies. RCA results guided the FMEA prioritization process, enabling targeted actions that reduced the highest RPN—from 576 to 144—for BOM consumption issues, confirming, consistent with [33,40], the value of FMEA in managing supply chain risks.

The high percentage of BOM-related issues highlights the need for robust data management systems, aligning with Waller et al.’s [41] emphasis on real-time data. The financial impact analysis (EUR 1948.10 variance in Q4 2024) highlights the need for precise cost control, particularly in mechanics and assembly processes. The results are consistent with Stanivuk et al. [17], who showed that structured process control can lead to significant cost reductions.

The action plan, with 69 tasks, provides a structured approach to addressing these issues, focusing on process standardization, role clarity and training. These actions align with [28] recommendation for process standardization to reduce discrepancies. The emphasis on roles, responsibilities and training supports Schroeder et al.’s findings [29] on the importance of organizational factors in successful Six Sigma projects in the case of emerging markets. Moreover, by improving inventory accuracy, the plan contributes to enhanced operational efficiency and better resource allocation, consistent with the findings of [27].

The findings directly support the transition toward Industry 5.0 and Logistics 5.0 principles, which emphasize human-centric and resilient operations. The RCA revealed that Manpower (40%) was the most significant category of root causes. The subsequent improvement actions focused on empowering human workers through standardized, precise processes, aligning with the human-centric focus of Industry 5.0. Furthermore, by drastically reducing the risk of inventory discrepancies, a major source of supply chain instability, the framework enhances operational resilience and supply chain stability, a core objective of Logistics 5.0. The use of smart scales and system controls also represents a move toward intelligent, collaborative technology assisting human decision-making, which is central to the human-machine collaboration required by the new paradigm.

This study contributes to the literature by offering a practical framework for inventory optimization, demonstrating the combined application of DMAIC, RCA and FMEA in manufacturing. The detailed RCA, FMEA and action plan provide a replicable model for other firms, emphasizing the importance of structured root cause identification, risk assessment and continuous improvement.

The comparative assessment between the present study and prior literature demonstrates that existing research typically applies Six Sigma tools in isolation, whereas this study adopts an integrated DMAIC–RCA–FMEA framework tailored to inventory accuracy challenges in the automotive sector. While DMAIC has been effectively used to improve manufacturing processes [1,4], it is rarely extended to internal logistics or inventory record management. Similarly, traditional RCA studies [7,8] provide valuable diagnostic structures but are not commonly embedded into a broader continuous improvement cycle. FMEA-focused works [9,10] offer systematic risk prioritization, yet they do not typically integrate earlier stages of problem identification through DMAIC or root-cause tools.

Compared with hybrid approaches in the literature [23,25], which combine defect analysis with selective Lean or Six Sigma instruments, the present research advances methodological novelty by synchronizing all three components—process optimization, cause identification and risk assessment—within a single coherent workflow. Moreover, studies addressing inventory record inaccuracy [14,40] primarily assess the consequences of inaccurate records rather than proposing structured Six Sigma interventions. By demonstrating how RCA outputs feed directly into FMEA scoring and how DMAIC stages guide the implementation of corrective controls, this study provides a more comprehensive and operationally actionable approach.

To systematically demonstrate how the proposed DMAIC–RCA–FMEA framework differs from and advances beyond existing approaches in the literature, Table 5 presents a structured comparison across key methodological and application criteria of prior studies applying DMAIC-only, RCA-only, FMEA-only and hybrid models, highlighting the specific gap addressed by this research.

Table 5.

Comparative analysis table.

However, this study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. The research was conducted within a single automotive company in an emerging market, which limits the generalizability of the findings to other companies, industries or geographical contexts with different operational structures. Also, external factors such as supplier reliability, market demand variability or regulatory changes were not included in the analysis, although they may affect inventory discrepancies. Despite efforts to enhance training and clarify roles, variability in human compliance and behavioral factors may affect the consistency of processes and the durability of improvements over time.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates a data-driven approach to improving inventory accuracy and optimizing supply chain performance in the automotive sector. The Analyze phase, combining RCA and FMEA, successfully identified and prioritized the key causes of inventory discrepancies, resulting in a 69-task action plan. Implementation of this plan led to substantial quantitative improvements, as measured by KPIs, including reductions in inventory adjustments from 1695 to 971 per month, reductions in RPN from 576 to 144 for BOM-related issues and stabilization of the absolute discrepancy-to-sales ratio at 0.98%. These KPI-driven outcomes confirm the effectiveness of the integrated DMAIC–RCA–FMEA framework in achieving operational stability and enhancing profitability.

From a qualitative perspective, the study highlights the managerial and organizational benefits of structured improvement initiatives. Emphasis on awareness, knowledge, discipline, clearly defined roles and a collaborative team mindset has strengthened the company’s capability to sustain process improvements, enhance customer satisfaction, reduce operational costs and improve overall efficiency. The business impact analysis further underscores the financial and operational consequences of inventory discrepancies, providing a compelling justification for continued investment in inventory accuracy initiatives.

These results confirm that the methodology is both theoretically sound and practically applicable, contributing to human-centric and resilient industrial practices consistent with Industry 5.0 objectives.

Future research should explore the long-term sustainability of the proposed improvements, particularly the effectiveness of process mentoring, ongoing training and monthly reporting in maintaining inventory accuracy. Comparative studies across multiple companies, industries or geographical regions could assess the generalizability of the DMAIC-RCA-FMEA framework and its adaptability to different operational contexts. Additionally, investigating the integration of emerging technologies, such as automated inventory tracking systems, IoT-enabled monitoring and AI-driven data validation, could further enhance real-time accuracy and minimize human error, linking to the principles of a smart and resilient supply chain.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.-R.P., I.M.P. and M.B.; methodology, I.-R.P. and M.B.; software, I.-R.P. and I.M.P.; validation, I.-R.P., I.M.P. and M.B.; formal analysis, I.M.P.; investigation, I.-R.P.; resources, I.-R.P.; data curation, I.-R.P.; writing—original draft preparation, I.-R.P. and I.M.P.; writing—review and editing, I.-R.P., I.M.P. and M.B.; visualization, I.-R.P., I.M.P. and M.B.; supervision, I.-R.P., I.M.P. and M.B.; project administration, I.-R.P.; funding acquisition, I.M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by Transilvania University of Brașov.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the first author on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hakimi, S.; Zahraee, S.M.; Mohd Rohani, J. Application of Six Sigma DMAIC methodology in plain yogurt production process. Int. J. Lean Six Sigma 2018, 9, 562–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, A.; Silva, F.J.G.; Campilho, R.D.S.G.; Ferreira, S.; Pinto, G. Applying DMADV on the industrialization of updated components in the automotive sector: A case study. Procedia Manuf. 2020, 51, 1332–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jou, Y.-T.; Silitonga, R.M.; Lin, M.-C.; Sukwadi, R.; Rivaldo, J. Application of Six Sigma Methodology in an Automotive Manufacturing Company: A Case Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devikar, A. Optimizing scalable process improvement frameworks for high-volume manufacturing plants. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2025, 15, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevan, H.; Westwood, N.; Crowe, R.; O’Connor, M. Lean Six Sigma: Some Basic Concepts; NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement: Nottingham, UK, 2017.

- Patil, A.B.; Inamdar, K.H. Process Improvement using DMAIC approach: Case Study in Downtime Reduction. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2014, 3, 1930–1934. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, B.; Fagerhaug, T. Root Cause Analysis: Simplified Tools and Techniques, 2nd ed.; ASQ Quality Press: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Doggett, A.M. Root cause analysis: A framework for tool selection. Qual. Manag. J. 2006, 12, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatis, D.H. Failure Mode and Effect Analysis: FMEA from Theory to Execution, 2nd ed.; ASQ Quality Press: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; You, J.X.; Song, M.S. Failure mode and effect analysis improvement: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2020, 199, 106885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Santhosh, A.M. The impact of inventory management on business performance: A comprehensive study. Int. J. Res. Financ. Manag. 2024, 7, 592–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immadisetty, V.S. Real-Time Inventory Management: Reducing Stockouts and Overstocks in Retail. J. Recent Trends Comput. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, S. Supply Chain Management: Strategy, Planning, and Operation, 7th ed.; Pearson: Hong Kong, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- DeHoratius, N.; Raman, A. Inventory record inaccuracy: An empirical analysis. Manag. Sci. 2008, 54, 627–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.A.A.; Fayad, A.A.S.; Alomair, A.; Al Naim, A.S. The Role of Digital Supply Chain on Inventory Management Effectiveness within Engineering Companies in Jordan. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Md Saad, N.A.; Amrin, A.; Jamaludin, K.R. Strategic Deployment of Lean Six Sigma in Managing Inventory Escalation Issue. J. Adv. Res. Bus. Manag. Stud. 2020, 18, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Stanivuk, T.; Gvozdenović, T.; Žanić Mikuličić, J.; Lukovac, V. Application of Six Sigma Model on Efficient Use of Vehicle Fleet-Web of Science Core Collection. Symmetry 2020, 12, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranavi, V.; Umasankar, V. Application of Six Sigma approach on hood outer panel to reduce the defect in painting peel off. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 46, 1269–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraleedharan, P.; Balamurugan, S.; Prakash, R. Six Sigma DMAIC in manufacturing industry: A literature review. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2017, 6, 18288–18293. [Google Scholar]

- Rifqi, H.; Zamma, A.; Souda, S.B.; Hansali, M. Lean manufacturing implementation through dmaic approach: A case study in the automotive industry. Qual. Innov. Prosper. 2021, 25, 54–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Rao, P.K.; Simpson, T.; Lu, Y.; Witherell, P.; Nassar, A.; Reutzel, E.; Kumara, S. Six-sigma quality management of additive manufacturing. Proc. IEEE 2021, 9, 347–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, A.; Gupta, P.; Kumar, V.; Al Owad, A.; Mahlawat, S.; Singh, S. The performance improvement analysis using Six Sigma DMAIC methodology: A case study on Indian manufacturing company. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gijo, E.V.; Antony, J.; Kumar, M.; McAdam, R.; Hernandez, J. An application of Six Sigma methodology for improving the first pass yield of a grinding process. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2014, 25, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Lal, E.H. Application of DMAIC technique in a manufacturing industry for improving process performance—A case study. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 7, 36–38. [Google Scholar]

- Gomaa, A.H. Manufacturing supply chain excellence through lean six sigma: A case study approach. Glob. J. Ind. Manag. 2025, 1, 2032. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, B.; Tian, Y. Six Sigma Applied in Inventory Management. Adv. Eng. Forum 2011, 1, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabani, A.; Maroti, G.; de Leeuw, S.; Dullaert, W. Inventory record inaccuracy and store-level performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 235, 108111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kök, A.G.; Shang, K.H. Evaluation of cycle-count policies for supply chains with inventory inaccuracy and implications on RFID investments. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2014, 237, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, R.G.; Linderman, K.; Liedtke, C.; Choo, A.S. Six Sigma: Definition and underlying theory. J. Oper. Manag. 2008, 26, 536–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, K. What Is Total Quality Control? The Japanese Way; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Pyzdek, T.; Keller, P. The Six Sigma Handbook, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: Columbus, OH, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mokhtarzadeh, M.; Rodríguez-Echeverría, J.; Semanjski, I.; Gautama, S. Hybrid intelligence failure analysis for industry 4.0: A literature review and future prospective. J. Intell. Manuf. 2025, 36, 2309–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curkovic, S.; Scannell, T.; Wagner, B. Using FMEA for supply chain risk management. Mod. Manag. Sci. Eng. 2013, 1, 251–265. [Google Scholar]

- Sattar, M.U.; Dattana, V.; Hasan, R.; Mahmood, S.; Khan, H.W.; Hussain, S. Enhancing Supply Chain Management: A Comparative Study of Machine Learning Techniques with Cost–Accuracy and ESG-Based Evaluation for Forecasting and Risk Mitigation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannella, S.; Framinan, J.M.; Bruccoleri, M.; Barbosa-Póvoa, A.P.; Relvas, S. The effect of Inventory Record Inaccuracy in Information Exchange Supply Chains. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2015, 243, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasaklis, T.K.; Voutsinas, T.G.; Tsoulfas, G.T.; Casino, F. A Systematic Literature Review of Blockchain-Enabled Supply Chain Traceability Implementations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M. Logistics and Supply Chain Management, 5th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Priya, S.K.; Jayakumar, V.; Kumar, S.S. Defect analysis and lean six sigma implementation experience in an automotive assembly line. Mater. Today 2020, 22, 948–958. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 5th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Waller, M.A.; Nachtmann, H.; Hunter, J. Measuring the impact of inaccurate inventory information on a retail outlet. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2006, 17, 355–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Zhou, R.; de Souza, R. Enhanced FMEA for Supply Chain Risk Identification. In The Road to a Digitalized Supply Chain Management: Smart and Digital Solutions for Supply Chain Management, Proceedings of the Hamburg International Conference of Logistics (HICL), Hamburg, Germany, 13–14 September 2018; epubli GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2018; Volume 25, pp. 311–330. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.