Abstract

The craft beer market is continually expanding, driven by the consumers’ demand for product diversification, which leads to innovation in the brewing industry. While traditional brewing focuses on consistency and high-volume efficiency using standard yeasts, craft brewing prioritizes small-batch experimentation and flavor complexity. Traditionally, Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Ale beer) and Saccharomyces pastorianus (Lager beer) yeast are used in brewing. The craft brewing revolution introduced the use of non-conventional yeast. These yeasts possess distinct technological characteristics compared to commercial starters, such as a richer enzyme profile. This biological diversity produces beers with novel, complex aroma profiles, and opens exciting avenues for flavor creation. Recently, non-alcoholic beer and low-alcoholic beer (NABLAB), and functional beer have become the new horizons for the application of non-conventional yeasts. In recent years, the brewing potential of these alternative yeasts has been extensively explored. However, some aspects relating to the interactions between yeast and raw materials precursors involved in the aroma of the final beer, and the management of yeasts in fermentation, remain unexplored. This review systematically outlines the various innovative ways in which non-conventional yeasts are applied in brewing, including healthier beer. Here, we explore how these yeasts can foster innovation in the beer sector and provide the possibility for sustainable development in contemporary brewing.

1. Introduction

The craft brewing phenomenon has seen significant growth since the early 2000s, piquing consumer interest and transforming the industry. Following an extended period dominated by a few global multinationals, craft breweries emerged, introducing innovative products and experimenting with diverse ingredients and brewing processes [1]. Craft beer stands out as a dynamic and creative sector within the food and beverage industry, focusing on quality, aroma, health, sustainability, regionality, and customized brewing technologies [2].

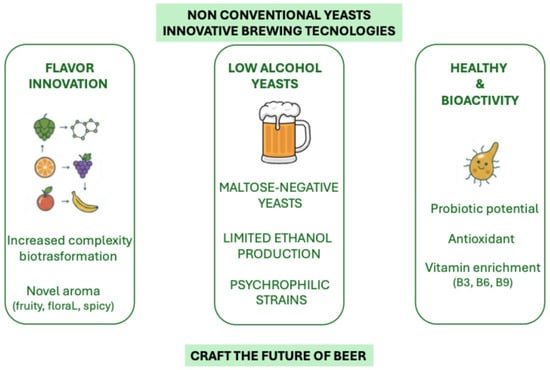

The creation of high-quality beer relies on brewing yeasts that yield positive fermentation as well as desirable aroma and flavor profiles [3]. The importance of Saccharomyces and non-Saccharomyces yeasts extends beyond the production of ethanol and carbon dioxide; they also generate various intermediate compounds and by-products that contribute to the taste and aroma of the beer [3,4]. In the 19th century, the industrial brewing sector’s demand for more uniform products led to the development of specific strains of brewer’s yeast, such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae for Ale beer and Saccharomyces pastorianus for Lager beer. Only a few beer styles, such as Belgian lambic and American Coolship ales, utilize spontaneous fermentation, incorporating native microorganisms, including non-conventional yeast species and bacteria. Research into indigenous non-conventional yeasts represents a promising strategy for craft beers (Figure 1) with unique characteristics.

Figure 1.

The main application of non-conventional yeasts in craft beer.

These yeasts can offer a variety of aromatic compounds and functional benefits, facilitating the production of innovative beer styles [5]. Non-conventional yeasts can diversify products, creating new beer styles, including flavored varieties, as well as specialty beers [6,7]. In addition to the classic styles, so-called specialty beers are appearing in the market, including products that do not fall into conventional styles, such as low-calorie, low-alcohol, and/or non-alcoholic (NABLAB) and gluten-free beers [8].

This review systematically explores the use of non-conventional yeasts in craft beer production. These yeasts contribute significantly to beer fermentation by enhancing flavor profiles through pure and mixed fermentation with S. cerevisiae and by producing organic acids in sour beers. Furthermore, non-conventional yeasts can modulate hop aromas, enhancing fruity perceptions through the release of thiols or terpenes via enzymatic actions and reducing off flavors like diacetyl or acetaldehyde. Finally, we will discuss the potential uses and applications of non-conventional yeasts in producing NABLAB and functional beers and the potential limitations due to the poor knowledge, particularly on safety aspects.

2. Non-Conventional Yeast in Brewing

Non-conventional yeast strains with brewing potential can originate from various sources, including official microorganism collections and natural environments like fermentative ecosystems, sourdough fermentation, and kombucha [8,9,10] and even isolated from contaminating yeasts in breweries that possess valuable brewing capabilities [11]. The current market demands a broader diversity of beers produced efficiently and sustainably, necessitating a new approach to yeast selection in fermentation. The traditional industrial brewing works with high-volume efficiency using standard yeasts. The final beer must be a consistent product over time to build consumer loyalty. Differently, craft brewing prioritizes small-batch experimentation and specific and special beers with flavor complexity. Traditionally, S. cerevisiae (Ale beer) and S. pastorianus (Lager beer) yeast are used in brewing. The craft brewing revolution managed the use of non-conventional yeast. Relying solely on commercial starter strains is no longer adequate for achieving these goals, particularly for low-alcohol beer production. As consumer interest shifts towards new flavor profiles, where alcohol content is less critical, the industry must embrace a wider range of yeast species. This shift reflects a growing enthusiasm for beers beyond traditional styles, which calls for redefining the concept of “brewer’s yeast” and expanding the variety of strains used in breweries [12].

2.1. Management of Non-Conventional Yeasts in Brewing

Non-conventional yeasts can be employed in spontaneous fermentation, mixed fermentation, co-fermentation, or as pure cultures in beer production (Table 1). Their different carbohydrate metabolism allows their application in conventional, low-alcohol, and non-alcoholic beers [6]. By positively influencing the sensory attributes of beer, these yeasts enhance aroma and flavor, serving as a natural tool for creating new styles that align with consumer demand for health beverages [7]. The fermentative performance of yeast during brewing is influenced by various factors, including wort ion concentration, stress tolerance, wort density at inoculation, dissolved oxygen levels, and fermenter geometry. Understanding these factors is essential for selecting an appropriate yeast strain for beer production. To ensure quality, the chosen yeast must efficiently metabolize nutrients from the wort, withstand environmental conditions such as osmotic pressure, pH, temperature, and ethanol concentration, and impart the desired flavors to the beer (Table 1). Due to the extensive biodiversity of yeast strains available, particularly those derived from diverse habitats such as wild and fermented foods and beverages [13], research on managing non-conventional yeasts is still in its early stages. However, several studies have begun to evaluate the use of various non-conventional yeast species in pure, mixed, sequential, or spontaneous fermentation cultures.

Table 1.

Fermentation characteristics of different non-conventional yeasts in brewing.

2.2. Spontaneous Fermentation

Spontaneously fermented beer is characterized by the wort without actively introducing any fermentative microbes by the brewer [34]. The initial fermentation occurs spontaneously, driven by wild yeasts and environmental bacteria. Following this primary fermentation, the brewer may introduce a specific culture of one or more microorganisms for secondary fermentation. Traditional examples of spontaneously fermented beers include Belgian lambics and sour lambics, which were originally crafted in the Senne Valley, particularly around Brussels, between October and March [35,36].

In the lambic brewing process, after mashing, the wort is transferred to open, shallow metal vessels known as coolships, where it is left to cool overnight. During this cooling period, microorganisms from the atmosphere inoculate the wort, initiating fermentation [5]. These coolships are typically stored in wooden-roofed rooms to allow the water vapor from the hot wort to condense and drip back into the vessel. Once cooled, the wort is transferred to wooden barrels, where fermentation continues at room or cellar temperatures, ranging from 15 to 25 °C. The microbiota present in these barrels also contributes to the fermentation process [5,37].

Maturation occurs in the same wooden barrels for a period ranging from 1 to 3 years before bottling. The final product is a sour, cloudy beer with an alcohol content of approximately 5%, low carbonation, and a light head [38]. Aging enhances certain aromatic characteristics, and achieving a harmonious balance among these flavors is crucial for consumer enjoyment. Spontaneous fermentation involves a complex and dynamic microbiota, with variations arising from different geographical regions, brewing techniques, and recipes [5,39,40,41].

Phases of Spontaneous Fermentation

Spontaneous fermentation can be divided into four distinct phases, each marked by a unique microbial consortium.

1. Initial Phase (1–4 weeks): This phase is dominated by Enterobacteriaceae [42,43], along with oxidative yeasts from genera such as Candida, Cryptococcus, Debaryomyces, Hansenula, Pichia, and Rhodotorula [44].

2. Main Fermentation Phase: Here, yeasts from the Saccharomyces genus, including S. cerevisiae, S. bayanus, S. kudriavzevii, and S. pastorianus, become predominant [40]. Other genera, such as Hanseniaspora and Kazachstania, are also present [44]. During this phase, these yeasts produce secondary metabolites—including esters, higher alcohols, and organic acids that significantly influence the organoleptic profile of beers [17,44].

3. Acidification Phase: In this phase, the fermentation is dominated by Lactobacilli and Pediococci, alongside lactic acid bacteria (LAB) [37,44,45]. Here, Saccharomyces yeasts are gradually replaced by Brettanomyces spp., which also play a crucial role during the maturation phase [46].

4. Maturation Phase: This final stage can last from several months to years and is primarily characterized by the activity of Brettanomyces yeasts, which exhibit high ethanol tolerance and the ability to ferment complex carbohydrates that are typically unfermented by Saccharomyces spp. [36,40,45]. Recent research indicates that multiple strains or subspecies of Brettanomyces are involved in wild beer production [41]. These yeasts impart the characteristic “Brett character” to the beer, often described as a mousy aroma with notes ranging from stable and horsey to leathery, medicinal, smoky, and clove-like. Additionally, Brettanomyces yeasts can produce fruity and floral aroma compounds through the bioconversion of hop compounds, wort carbohydrates, and exopolysaccharides from Pediococci [40,46].

Recent advancements in understanding the various microorganisms involved in spontaneous fermentation have led to the development of innovative techniques for sour beer production. These techniques enable better process control and reduce production time. One such approach involves the controlled use of non-conventional yeasts in mixed fermentation with S. cerevisiae strains, resulting in beers that possess unique sensory characteristics alongside their sourness. For instance, a Lambic beer was produced using a combination of a Dekkera bruxellensis (synonymous of Brettanomyces bruxellensis) strain, the commercial starter yeast S. cerevisiae S-04, and the LAB Lactobacillus brevis, all co-fermented together [47]. This co-fermented beer demonstrated a significant enhancement in aromatic characteristics and antioxidant capacity compared to sour beers inoculated solely with S. cerevisiae. After 12 months, the beer exhibited a pronounced “Brett” aroma profile and increased antioxidant properties [47].

2.3. Pure Culture

Non-conventional yeasts are increasingly applied in brewing to modulate fermentation performance, aroma formation, and sensory properties, and many species can be used in pure culture to produce beers with low or no alcohol (Table 1). Their use has been investigated primarily to enhance flavor complexity and overall sensorial quality. Among them, Wickerhamomyces anomalus (Table 1) and Torulaspora delbrueckii (Table 1) are considered particularly promising for beer production, as they generate distinctive ester and higher alcohol profiles while often limiting ethanol formation. W. anomalus ferments maltose with strain dependent variability and is an efficient producer of ethyl propanoate, β-phenyl ethanol, 2-phenyl ethyl acetate, and especially ethyl acetate, which can contribute pleasant fruity notes at moderate levels but solvent like aromas when excessive [25,26,27]. T. delbrueckii has also been widely studied in brewing; it can show variable malt fermenting ability, but typically yields beers rich in amyl alcohols and esters associated with rose, bubblegum, banana, and citrus notes, combined with low attenuation (37%) and reduced ethanol content (2.66% v/v), making it attractive for low alcohol styles [48]. Several other non-conventional yeasts have shown valuable brewing traits. Pichia kluyveri can produce very high levels of 2-phenyl ethyl acetate, isoamyl acetate, ethyl acetate, and linalool [49] whereas Pichia anomala and Pichia kudriavzevii tend to generate high ethyl acetate but comparatively low isoamyl acetate, creating different fruity profiles The use of P. kluyveri, as a starter culture to produce beer with highly interesting aroma characteristics, in need of optimizing the process conditions and/or selecting the most suitable S. cerevisiae strains for the second inoculation. Zygoascus meyerae, P. anomala can significantly exceed sensory thresholds for key volatiles such as 4-vinylguaiacol, β-phenyl ethanol, and geraniol, resulting in beers with pronounced clovelike-, floral, and fruity characteristics [50]. A study on P. kluyveri and Hanseniaspora vineae showed significant increases in free 3-mercaptohexan-1-ol (3MH), enhancing passion fruit notes [28]. Moreover, some researchers found that the high production of acetate esters by these same yeasts can create a “masking effect,” where the heavy floral/banana scents overwhelm the delicate tropical thiols A strain of Candida glabrata, which exhibited high β-glucosidase activity, showed a 50-fold higher geraniol content, resulting in the production of a final beer with unique floral and fruity characteristics [51]. Lachancea thermotolerans (Table 1) contributes to lactic acid during primary fermentation, imparting the sourness and mouthfeel typical of sour beers [20]. However, higher concentrations of lactic acid can lead to a perceived loss of “mouthfeel” and can inhibit the expression of certain hop-derived terpene aromas, making the beer taste “thin” or “sharp” rather than complex [52].

Brettanomyces/Dekkera species (particularly B. bruxellensis) are notable for producing complex mixtures of esters and phenolic compounds that can add spicy, fruity, or “funky” notes valued in certain specialty beers when present at controlled levels. It is widely demonstrated that small amounts of 4-EG and 4-EP are seen as essential for the “terroir” and complexity of wild ales and Lambics. In contrast, in many craft styles (like NEIPAs), even trace amounts of these compounds are classified as spoilage. Furthermore, the vinyl phenol reductase (VPR) enzyme activity varies so wildly between strains that results are often unpredictable [53].

Their β-glucosidase activity enables hydrolysis of glycosidic precursors in hops and wood, releasing monoterpenes such as linalool and methyl salicylate that intensify citrus, floral, minty, or spicy hop aromas [54]. Selected strains are therefore attractive both for pure fermentations and for co-culture with S. cerevisiae. Pure fermentation of the following non-conventional yeast species, H. vineae, Hanseniaspora valbyensis, Metschnikowia pulcherrima, Hanseniaspora guilliermondii, Zygosaccharomyces bailii, T. delbrueckii, W. anomalus was carried out [55]. Among these, W. anomalus was selected in pure culture for brewing low alcohol content beer (1.25% (v/v) for its fruity and phenolic flavors and the absence of wort flavors. Other non-conventional yeast species, unable to ferment maltose, may be used in sequential or mixed fermentations to contribute to flavor profiles. Saccharomyces boulardii investigated in pure culture for several applications produced probiotic non-alcoholic beer [56]. In a study of Breno Pereira de Paula et al. [57], it was reported that S. boulardii has the potential to produce probiotic wheat beers, without any significant reduction in the population during beer storage, tolerating typical wort sugars and bitterness and providing potential health benefits linked to probiotic intake. Thus, the experimental results mentioned above demonstrate that S. boulardii can brew probiotic non-alcoholic beer [56]. Overall, these findings support the use of non-conventional yeasts in pure, sequential, or mixed fermentations as valuable tools for creating beers with reduced alcohol content, enhanced complexity, and potential functional properties.

2.4. Sequential Fermentation

Sequential and mixed fermentations with non-conventional yeasts and S. cerevisiae are widely used to diversify beer flavor, enhance aroma complexity, and, in some cases, improve functional properties such as antioxidant activity and probiotic potential [57]. These approaches allow brewers to combine the metabolic traits of different yeasts to obtain beers with distinctive sensory profiles and added health -related value [17,58,59,60]. Non-conventional yeasts are often co-inoculated or used sequentially with S. cerevisiae to ensure reliable fermentation while enriching the volatile profile with esters, higher alcohols, phenols, and other aroma-active metabolites. The final aroma of each beer depends strongly on the chosen strain combination and on process parameters such as inoculation order, inoculum ratio, temperature, and fermentation time.

T. delbrueckii is regarded as one of the most promising non-conventional yeast species for brewing, particularly in mixed or sequential fermentations [61]. When used first and followed by S. cerevisiae, it can increase compounds like 4—vinyl guaiacol and modify phenolic and ester balances, yielding beers with enhanced spicy or clove -like notes and altered fatty-acid derived flavors [28]. Co-fermentation at different S. cerevisiae/T. delbrueckii ratios can shift production of esters such as ethyl octanoate and modulate levels of acetaldehyde and higher alcohols, providing a practical lever for fine-tuning aroma [62]. Kayadelen et al. [63] demonstrated that the ester content of beer produced by mixed fermentation of T. delbrueckii with S. cerevisiae is higher than that produced by S. cerevisiae alone.

P. kluyverii and Pichia kudriavzevii have attracted attention to their strong impact on fruity esters in mixed or sequential fermentations. P. kluyveri can markedly increase isoamyl acetate and related compounds, intensifying banana-like notes that are desirable in wheat beers, while co-fermentation with S. cerevisiae helps complete attenuation [28]. In a recent work this species showed in both co-culture and sequential fermentation residual sugar levels comparable to those exhibited by S. cerevisiae monoculture fermentation [49]. P. kudriavzevii, when combined with S. cerevisiae, tends to produce high levels of ethyl acetate, 2-phenyl ethanol, isoamyl alcohol, and other fruity volatiles, generating intensely fruity wheat beers when used in either sequential or mixed modes [64].

Hanseniaspora guilliermondii (Table 1), when applied first and followed by S. cerevisiae, can dramatically increase phenyl ethyl acetate levels (increased by 8.2 times), imparting pronounced rose and honey notes and improving the perceived body and balance of the beer [65]. Similar strategies with H. vineae and M. pulcherrima have been shown in related fermentations to boost fruity esters, β--damascenone, antioxidant capacity, and melatonin, suggesting that beers produced with these yeasts may offer functional benefits when consumed in moderation. During aging, co--fermentation with B. bruxellensis can generate complex mixtures of esters, phenols, acids, and terpene alcohols that contribute to the characteristic “Brett” profile, including spicy, barnyard, and fruity notes valued in lambic and gueuze styles [66]. B. bruxellensis, known for its characteristic “horse blanket” flavor and high acidity, plays a vital role in the mixed fermentation of Lambic and Gueuze beers [53]. Brettanomyces yeasts are particularly associated with the formation of 4-ethyl guaiacol and related phenolic compounds that add spicy and smoky nuances when controlled carefully [28]. Mixed fermentations including the probiotic yeast S. cerevisiae var. boulardii often end with this strain dominating cell populations; such beers can retain many viable probiotic cells, show increased antioxidant activity and polyphenol content, and maintain acceptable aroma comparable to beers produced with S. cerevisiae alone [67]. Postigo et al., [47] tested H. vineae and M. pulcherrima in mixed fermentation, and the beers were characterized by a greater body and balance, as well as fruity aromas and flavors. Moreover, the selected yeasts produced the highest levels of antioxidant capacity and melatonin during fermentation. All these features suggest that these beers can be considered functional for moderate consumption.

3. How Non-Conventional Yeasts Transform Beer

We can examine their metabolic contributions through three main chemical “engines”: the production of volatile phenols, the enzymatic release of hop-derived thiols, and the synthesis of esters and organic acids (Table 2).

Table 2.

Biochemical mechanisms of the main non-conventional yeasts involved in brewing process innovation.

The “wild” character of Brettanomyces is chemically defined by the transformation of hydroxycinnamic acids, which are naturally present in malt. While most brewing yeasts can decarboxylate these acids into vinyl-phenols (producing a simple clove-like aroma), Brettanomyces species possess a unique enzyme called vinyl phenol reductase (VPR).

In this pathway, ferulic acid is first converted to 4-vinylguaiacol. The VPR enzyme then uses NADH as a cofactor to reduce this intermediate into 4-ethylguaiacol (4-EG). Similarly, p-coumaric acid is reduced to 4-ethylphenol (4-EP). This specific reduction is a survival strategy for the yeast to maintain its internal redox balance NAD++/NADH+), but for the brewer, it results in the complex, “funky” aromas of leather, barnyard, and aged wood [68]. The species L. thermotolerans has gained popularity for its ability to naturally sour beer during primary fermentation. Unlike Saccharomyces, which convert most of the pyruvate into ethanol via acetaldehyde, L. thermotolerans utilizes the enzyme L-lactate dehydrogenase (LDH).

Through this pathway, pyruvate is diverted from the alcoholic fermentation route and reduced directly into L-lactic acid. This process consumes NADH and releases NAD+ allowing glycolysis to continue. The resulting beer has a lower pH and a clean, sharp acidity that avoids the “vinegar” notes associated with acetic acid, as Lachancea typically produces very low levels of volatile acidity compared to other wild yeasts. Many “tropical” aromas in modern beer are not originally present in the hops as free molecules but are bound to amino acids like cysteine or peptides like glutathione [69].

Non-conventional yeasts, particularly from the genus Pichia (such as P. kluyveri), are highly efficient at “unlocking” these compounds.

This is achieved through beta-lyase activity. The enzyme targets the carbon-sulfur bond of the odorless precursor (e.g., Cys-3MH), cleaving the molecule to release the free volatile thiol 3-mercaptohexan-1-ol (3MH). Chemically, this transformation is crucial because these thiols have incredibly low detection thresholds, meaning even trace amounts produced by the yeast can drastically change the sensory profile toward passion fruit and grapefruit.

Yeasts like T. delbrueckii and H. uvarum are often described as “ester powerhouses.” Their metabolism focuses heavily on the activity of Alcohol Acetyltransferases (AAT).

The chemical reaction involves the condensation of an acyl-CoA (usually Acetyl-CoA derived from sugar metabolism or fatty acid synthesis) with a higher alcohol (produced via the Ehrlich pathway from amino acids). Hanseniaspora species are particularly specialized in the production of 2-phenyl ethyl acetate, which is formed from the precursor 2-phenyl ethanol. This result in intense rose and floral aromas that are much more pronounced than those found in standard ales. Furthermore, Torulaspora yeasts tend to produce higher concentrations of ethyl esters (like ethyl hexanoate) which provide a “refined” fruity character resembling red apples or pineapple [70].

4. Beer Revolution with Non-Conventional Yeasts: The Healthy Issue

Functional beers were created to improve the health benefits of beverages by incorporating advantageous functional components and utilizing functional yeasts. Non-conventional yeasts can be extensively utilized to generate or convert advantageous compounds [71]. Among specialty beers, the most fascinating include low-calorie beer, low-alcohol or alcohol-free beer, beers with unique flavors, gluten-free beer, and functional beer. These unique beers are becoming more popular among consumers who are more focused on their health. The most notable non-conventional yeasts are the genera Hanseniaspora, Pichia, Torulaspora, and Wickerhamomyces (Table 1), among others, due to their varied enzymatic activities and their capacity to bio convert the components of the fermentation substrate. Craft beer is usually unfiltered and unpasteurized, making it a possible source of health advantages due to its beneficial compounds (antioxidants and polyphenols) and microorganisms [72,73] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Non-conventional yeasts with health properties.

4.1. Probiotic Beer as Vehicle for Probiotic

A novel functional beer is represented by probiotic beer, obtained by incorporating probiotic microorganisms. This strategy exploits evidence that craft beer is typically an unpasteurized and unfiltered matrix, thus representing a potential vehicle for delivering probiotics. Probiotics are defined as live microorganisms added to food, which, at certain doses, can be potentially beneficial for human health, especially in maintaining intestinal microbial balance [74]. Consequently, a probiotic beer is obtained by using probiotic microorganisms during the fermentation process. The best-known microorganisms utilized for their probiotic characteristics are lactic acid bacteria (LAB). Probiotics are not only bacteria, indeed, S. cerevisiae var. boulardii is a probiotic yeast strain that has been explored for specialty unfiltered and unpasteurized probiotic beer [57,67,75]. Studies have demonstrated that foods and drinks containing live probiotics are more effective in providing health benefits than products with inactive probiotics. Craft beer containing live yeasts can therefore be considered a new tool for beneficial health effects [76]. The use of several non-conventional genera such as Brettanomyces, Debaromyces, Dekkera, Hansenula, Hanseniaspora, Kloeckera, Schizosaccharomyces, Sporobolomyces, Trichosporon, Torulopsis, Zygosaccharomyces, Lachancea, Kluyveromyces, Torulaspora, Metschnikowia, Kazachstania, Brettanomyces, Pichia, Candida, Hanseniaspora, Rhodotorula and Rhodosporidiobolus was found to have great potential for use in the production of craft beers with probiotic characteristics [21,77]. Among these genera, several yeast strains have been investigated for their potential probiotic properties. Three non-conventional yeast strains belonging to the species P. kluyveri, H. uvarum, and Candida intermedia have demonstrated probiotic properties [78]. Since craft beer is generally unfiltered or unpasteurized, the yeast cells remaining after fermentation can impart a probiotic character to the beer and be considered beneficial to health. For this reason, craft rather than industrial brewing would be more appropriate, as viability is crucial for the efficacy of probiotics [67]. However, it should be noted that the presence of yeasts in beer, while contributing to a unique taste, can reduce its shelf life, as cell lysis during storage can negatively affect quality. Therefore, strain selection is fundamental in the production of craft beer.

One of the crucial points in probiotic beer production is the choice of when and how to introduce the chosen microbial strain or group. In fact, the addition can occur at different productions. The addition must clearly occur after any heat treatment to reach the required high cell concentration and ensure the viability of the live cultures [79]. Since a substantial concentration of live probiotic microorganisms is essential to the definition of a functional beverage, this requirement often gives craft breweries an advantage over industrial breweries [80]. Another strategy to obtain beer with functional characteristics could be the combination of functional or probiotic yeasts with functional ingredients [81]. Among these, promising ingredients include legumes such as chickpeas, lentils, and soy, which are important sources of protein for human health [22].

4.2. Healthy Yeast Metabolites

Beer contains a variety of beneficial substances, including antioxidants, protein (0.2–6.6 g/L), flavonoids (0.03–18.30 mg/L), polyphenols (34–426 mg/L), as well as small amounts of B group vitamins, macro and micronutrients, and soluble fiber [82]. These metabolites originate from the ingredients utilized in the beer-making process as well as from the microorganisms participating in fermentation. Certainly, throughout the fermentation process, yeasts generate metabolites that possess significant nutritional value and health-enhancing qualities. Wild yeast varieties can generate premium craft beers that are rich in nutrients, offer health benefits, and feature distinct flavor characteristics [21].

The use of non-conventional yeasts in beer production not only enhances organoleptic traits but also leads to beers that offer notable health benefits, featuring reduced alcohol and energy content along with increased levels of ascorbic acid, phenolic compounds, and antioxidant properties [83]. B vitamins are an important class of vitamins, essential for optimal physiological and neurological functions of human metabolism [84]. It has been widely demonstrated that yeasts may be able to synthesize vitamins B3, B6, and B9 [85,86,87]. Generally, beer brewed with traditional yeasts have sufficient B vitamin content to meet daily requirements; moderate beer consumption has even been found to have a specific positive impact on health because it can increase B9 and vitamin B12 intake [88,89]. Non-alcoholic beers fermented with a strain of S. ludwigii, two different strains of Cyberlindnera saturnus and Kluyveromyces marxianus have also been shown to contain B vitamins and can therefore be used as supplements to a balanced diet [84]. This type of beer can help people protect their health.

Low to moderate beer intake has demonstrated beneficial health impacts, promoting the growth of healthy microbiota. Multiple studies indicate that beer promotes gut microbiota by enhancing the growth of saccharolytic microorganisms that produce short-chain fatty acids [90].

4.3. Functional Yeasts

At present, numerous investigations have been carried out to assess the effectiveness of different non-traditional probiotic starter cultures in the production of craft beer [67,69,75]. S. cerevisiae var. boulardii, utilized in craft beer brewing, resulted in beers with decreased alcohol levels, enhanced antioxidant properties, comparable sensory characteristics to the commercial S. cerevisiae starter, significantly higher yeast viability after 45 days, and heightened acidification, which lowers contamination risks in large-scale brewing. Moreover, the probiotic yeast exhibited quicker growth and greater cell sizes compared to the commercial yeast, enhancing the probiotic mass in the final craft beer [75]. S. cerevisiae var. boulardii was likewise evaluated in combination with various S. cerevisiae strains during wort fermentation to create craft beers offering enhanced health advantages [69]. The application of these mixed fermentations did not harm beer aroma. It enhanced antioxidant activity and polyphenol levels compared to beers made with a single starter yeast, demonstrating the beneficial effect of the probiotic yeast strain on these aspects [67]. Furthermore, S. cerevisiae var. boulardii was used in mixed fermentation with lager starter strains, increasing its viability during 28 days of storage. Research on probiotic yeasts in craft beer has focused on non-conventional yeasts. Forty-three yeast strains belonging to the genera Rodosporidobolus, Candida, Lachancea, Rhodotorula, Torulaspora, Kazachstania, Brettanomyces, Pichia, Kluyveromyces, Metschnikowia, Hanseniaspora and Saccharomyces, previously validated for their probiotic characteristics, were tested for craft beer production [21]. In this research, hydrolyzed chickpea wort (PCW) or lentil wort (PLW) (substituting 20% of the wort) was incorporated into the wort utilized for craft beer production to enhance the protein levels in the finished beers. The chosen strains, Kazachstania unispora, L. thermotolerans, and S. cerevisiae, may serve as promising microbial options for creating an exceptional craft beer featuring elevated nutritional and functional traits along with a unique aroma [22]. The non-conventional yeasts used in beer brewing, along with their probiotic characteristics and effects on flavor, were assessed for the creation of specialty and healthier beers, including non-alcoholic/low-alcohol beers (NABLAB), low-calorie beers, and functional beers. These applications probably take advantage of the metabolic variations present in different non-traditional yeast species. Nonetheless, additional research is required to comprehend the mechanisms associated with the functional properties of non-conventional yeasts.

4.4. NABLAB

There is an increasingly massive customer demand for low-alcohol (0.5–1.2% v/v) and non-alcoholic (<0.5% v/v) beers (NABLAB). Various technological approaches can be used to produce these beers, such as physically removing alcohol from the beer or stopping fermentation with conventional brewing yeast, but in both cases, they lead to products with less-than-pleasant flavor profiles. Another strategy is the use of non-conventional yeasts, which exhibit a low or limited ability to ferment maltose, allowing them to produce low-alcohol beers while still maintaining aromatic complexity. S. ludwigii can produce non-alcoholic beers with rich aroma profiles thanks to its production of aromas (mainly esters and higher alcohols) [91]. P. kluyveri has a limited ability to ferment glucose, while significantly converting hop compounds into positive aroma compounds. This species produces medium levels of esters and high amounts of higher alcohols. Moreover, the co-fermentation of S. cerevisiae and P. kluyveri in a 1:10 ratio produced an ABV of 2.98% (v/v), exhibiting high concentrations of isoamyl acetate and phenyl ethyl acetate exhibiting banana, rose aromas. On the other hand, further studies are needed to clarify the relationship among some fermentation parameters, reducing sugar, and sensory properties [92]. Regarding Z. rouxii, the literature reports conflicting data regarding its application to obtain NABLAB beers [30,93] since the final content of ethanol found in the final product has been highly variable in the tests performed. De Francesco et al. [94] reported that beer fermented with the psychrophilic basidiomycete yeast Mrakia gelida, showed a low alcohol content of 1.40% (v/v) and a low diacetyl concentration (5.04 μg/L) contain more fruity aromas, such as apricot, grape, and lychee [94]. Low-alcohol beer produced by M. gelida is clear and yellow, with a fine and persistent head, full of intense and rich fruity aromas [94]. Methner et al. [84] used Saccharomycopsis fibuligera, to produce low-alcohol beer with an initial sugar content of 10 °P. In this way, a production of low-alcohol beer, approximately 0.8% (v/v) was obtained [84]. Starmerella bombicola, an important industrial producer of biosurfactants, was introduced for the first time into beer production [91]. Surprisingly, even at a temperature of 20 °C, this species was able to produce alcohol-free beer after 10 days of fermentation. This beer exhibited neutral aroma characteristics without any negative impact on sensory properties [75]. Cyberlindnera saturnus, a maltose-negative species, is suitable to produce non-alcoholic beer [31,95]. This yeast strain synthesizes a significant amount of isoamyl acetate, giving it a fruity aroma, predominantly reminiscent of banana and a unique flavor of red berries and apples, determined by its secondary metabolite β-damascenone [83,95]. For these reasons, the use of biological methods, based on the use of non-conventional yeasts as starter cultures, could be a valid tool for producing NABLAB. Indeed, these yeasts generally exhibit low capacity to ferment maltose (and maltotriose), the most abundant reducing sugar, in wort combining, at the same time, aroma enhancement and complexity improvement [17,75,95].

5. Potential Limitations and Future Perspectives

The use of non-conventional yeasts in craft beer as a tool for innovation has attracted great interest from both researchers and brewers. The safety assessment of non-conventional yeasts is a relevant aspect that needs to be investigated since a few yeast species are generally recognized as safe (GRAS/QPS) for use in food production [96]. In this regard, accurate taxonomic species identification and safety assessment should be evaluated. The production of high levels of histidine, phenylalanine, or tyrosine could increase the synthesis of biogenic amines with a risk to the health of the consumer [97]. Another relevant feature that needs to be investigated and clarified is the modality and feasibility of their use in breweries, taking in account the technological process and the possible interactions with the raw materials [97,98]. Considering these aspects, a guideline for the use of non-conventional yeasts in brewing is desirable. On the other hand, some non-conventional strains are already commercialized as starters for enology or brewing. They could release some amino acids, providing yeast assimilable nitrogen to S. cerevisiae during mixed fermentation.

6. Conclusions

The use of non-conventional yeasts in craft beer production represents significant growth in the brewing sector, and beer could be a promising vehicle for innovation (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Innovative brewing technologies with non-conventional yeasts.

In contrast to traditional brewing, which typically relies on highly standardized strains of S. cerevisiae or S. pastorianus to ensure consistency and rapid turnover,—non-conventional yeasts not only improve the sensory profile of beer but also expand the potential for application and development in the brewing industry. Exploring non-conventional yeasts will play a fundamental role in shaping the future of beer. While traditional methods often prioritize predictable attenuation and technical efficiency, further investigations into their fermentation mechanisms, genomic and metabolic pathways, and their aroma contributions will provide valuable insights for brewers looking to innovate and differentiate their products in an increasingly competitive market. Furthermore, developing fermentation strategies that exploit the unique characteristics of these yeasts will further enrich the craft beer sector. The management of non-conventional yeasts provides the beer with further natural aromatic variations, such as complex esters and phenols—that differentiate it from mass-produced commercial beers, which often prioritize a neutral or uniform profile. Indeed, their use in pure culture, sequential culture, or with aeration during fermentation makes them very versatile. Furthermore, beer is composed of several bioactive compounds that not only give it sensory properties but also improve its functionality, in addition to providing health benefits, obviously when consumed responsibly. Functional beers will see the emergence of a health-conscious consumer who is attentive to the flavor that distinguishes this fermented beverage. Further research is needed to understand and develop the use of these yeasts in the brewing process, their probiotic and functional properties, and, above all, product stabilization strategies, which remain more challenging compared to the straightforward stabilization of traditional lagers and ales.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.C. and M.C.; investigation, L.C., M.C., A.A. and F.C.; writing—original draft preparation, L.C., M.C., A.A. and F.C. writing—review and editing, L.C., M.C., A.A. and F.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Garavaglia, C.; Swinnen, J. Economic Perspectives on Craft Beer: A Revolution in the Global Beer Industry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; ISBN 978-3-319-58235-1. [Google Scholar]

- Gobbi, L.; Stanković, M.; Ruggeri, M.; Savastano, M. Craft Beer in Food Science: A review and conceptual framework. Beverages 2024, 10, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binati, R.L.; Salvetti, E.; Bzducha-Wróbel, A.; Bašinskienė, L.; Čižeikienė, D.; Bolzonella, D.; Felis, G.E. Non-Conventional Yeasts for Food and Additives Production in a Circular Economy Perspective. FEMS Yeast Res. 2021, 21, foab052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, C. The Impact of Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts in the Production of Alcoholic Beverages. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 9861–9874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitaels, F.; Wieme, A.D.; Janssens, M.; Aerts, M.; Daniel, H.-M.; Van Landschoot, A.; De Vuyst, L.; Vandamme, P. The Microbial Diversity of Traditional Spontaneously Fermented Lambic Beer. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e95384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postigo, V.; Sánchez, A.; Cabellos, J.M.; Arroyo, T. New Approaches for the Fermentation of Beer: Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts from Wine. Fermentation 2022, 8, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canonico, L.; Galli, E.; Ciani, E.; Comitini, F.; Ciani, M. Exploitation of Three Non-conventional Yeast Species in the Brewing Process. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubillos, F.A.; Gibson, B.; Grijalva-Vallejos, N.; Krogerus, K.; Nikulin, J. Bioprospecting for Brewers: Exploiting Natural Diversity for Naturally Diverse Beers. Yeast 2019, 36, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozzachiodi, S.; Bai, F.-Y.; Baldrian, P.; Bell, G.; Boundy-Mills, K.; Buzzini, P.; Čadež, N.; Cubillos, F.A.; Dashko, S.; Dimitrov, R.; et al. Yeasts from Temperate Forests. Yeast 2022, 39, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexa, L.; Csoma, H.; Ungai, D.; Kovács, B.; Czipa, N.; Miklós, I.; Kállai, Z.; Papp, L.A.; Takács, S. Alternative Yeast Strains in Beer Production: Impacts on Quality and Nutritional Value. Beverages 2025, 11, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogerus, K.; Eerikäinen, R.; Aisala, H.; Gibson, B. Repurposing Brewery Contaminant Yeast as Production Strains for Low-Alcohol Beer Fermentation. Yeast 2022, 39, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A. Brewing Microbiology: Managing Microbes, Ensuring Quality and Valorising Waste; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; ISBN 978-0-323-99607-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bamforth, C.W. Fermentation of Beer. In Brewing New Technologies; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2006; pp. 228–253. ISBN 978-1-84569-173-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ciani, M.; Canonico, L.; Comitini, F. Nonconventional Yeasts in Craft Beer Brewing. In Craft Beer; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025; pp. 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Michel, M.; Kopecká, J.; Meier-Dörnberg, T.; Zarnkow, M.; Jacob, F.; Hutzler, M. Screening for New Brewing Yeasts in the Non-Saccharomyces Sector with Torulaspora delbrueckii as Model. Yeast 2016, 33, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, R.F.; Alcarde, A.R.; Portugal, C.B. Could Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts Contribute on Innovative Brewing Fermentations? Food Res. Int. 2016, 86, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, E.J.; Teixeira, J.A.; Brányik, T.; Vicente, A.A. Yeast: The Soul of Beer’s Aroma—A Review of Flavour-Active Esters and Higher Alcohols Produced by the Brewing Yeast. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 1937–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabaci Karaoglan, S.; Jung, R.; Gauthier, M.; Kinčl, T.; Dostálek, P. Maltose-Negative Yeast in Non-Alcoholic and Low-Alcoholic Beer Production. Fermentation 2022, 8, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osburn, K.; Amaral, J.; Metcalf, S.R.; Nickens, D.M.; Rogers, C.M.; Sausen, C.; Caputo, R.; Miller, J.; Li, H.; Tennessen, J.M. Primary Souring: A Novel Bacteria-Free Method for Sour Beer Production. Food Microbiol. 2018, 70, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domizio, P.; House, J.F.; Joseph, C.M.L.; Bisson, L.F.; Bamforth, C.W. Lachancea thermotolerans as an Alternative Yeast for the Production of Beer†. J. Inst. Brew. 2016, 122, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canonico, L.; Zannini, E.; Ciani, M.; Comitini, F. Assessment of Non-Conventional Yeasts with Potential Probiotic for Protein-Fortified Craft Beer Production. LWT 2021, 145, 111361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canonico, L.; Agarbati, A.; Zannini, E.; Ciani, M.; Comitini, F. Lentil Fortification and Non-Conventional Yeasts as Strategy to Enhance Functionality and Aroma Profile of Craft Beer. Foods 2022, 11, 2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canonico, L.; Agarbati, A.; Comitini, F.; Ciani, M. Recycled Brewer’s Spent Grain (BSG) and Grape Juice: A New Tool for Non-Alcoholic (NAB) or Low-Alcoholic (LAB) Craft Beer Using Non-Conventional Yeasts. Foods 2024, 13, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canonico, L.; Agarbati, A.; Comitini, F.; Ciani, M. Unravelling the Potential of Non-Conventional Yeasts and Recycled Brewers Spent Grains (BSG) for Non-Alcoholic and Low Alcohol Beer (NABLAB). LWT 2023, 190, 115528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passoth, V.; Fredlund, E.; Druvefors, U.Ä.; Schnürer, J. Biotechnology, Physiology and Genetics of the Yeast Pichia Anomala. FEMS Yeast Res. 2006, 6, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G.M. Pichia Anomala: Cell Physiology and Biotechnology Relative to Other Yeasts. Antonie Van. Leeuwenhoek 2011, 99, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-J.; Choi, Y.-R.; Lee, S.-Y.; Park, J.-T.; Shim, J.-H.; Park, K.-H.; Kim, J.-W. Screening Wild Yeast Strains for Alcohol Fermentation from Various Fruits. Mycobiology 2011, 39, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt, S.; Mukherjee, V.; Lievens, B.; Verstrepen, K.J.; Thevelein, J.M. Bioflavoring by Non-Conventional Yeasts in Sequential Beer Fermentations. Food Microbiol. 2018, 72, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellut, K.; Michel, M.; Zarnkow, M.; Hutzler, M.; Jacob, F.; De Schutter, D.P.; Daenen, L.; Lynch, K.M.; Zannini, E.; Arendt, E.K. Application of Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts Isolated from Kombucha in the Production of Alcohol-Free Beer. Fermentation 2018, 4, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matraxia, M.; Alfonzo, A.; Prestianni, R.; Francesca, N.; Gaglio, R.; Todaro, A.; Alfeo, V.; Perretti, G.; Columba, P.; Settanni, L. Non-Conventional Yeasts from Fermented Honey by-Products: Focus on Hanseniaspora uvarum Strains for Craft Beer Production. Food Microbiol. 2021, 99, 103806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Francesco, G.; Turchetti, B.; Sileoni, V.; Marconi, O.; Perretti, G. Screening of New Strains of Saccharomycodes ludwigii and Zygosaccharomyces rouxii to Produce Low-Alcohol Beer: Screening of New Strains of S. ludwigii and Z. Rouxii. J. Inst. Brew. 2015, 121, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methner, Y.; Hutzler, M.; Zarnkow, M.; Prowald, A.; Endres, F.; Jacob, F. Investigation of Non- Saccharomyces Yeast Strains for Their Suitability for the Production of Non-Alcoholic Beers with Novel Flavor Profiles. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 2022, 80, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capece, A.; De Fusco, D.; Pietrafesa, R.; Siesto, G.; Romano, P. Performance of Wild Non-Conventional Yeasts in Fermentation of Wort Based on Different Malt Extracts to Select Novel Starters for Low-Alcohol Beers. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K.C.; Hynes, S.H.; Ingledew, W.M. Influence of Medium Buffering Capacity on Inhibition of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Growth by Acetic and Lactic Acids. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 1616–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossaert, S.; Winne, V.; Van Opstaele, F.; Buyse, J.; Verreth, C.; Herrera-Malaver, B.; Van Geel, M.; Verstrepen, K.J.; Crauwels, S.; De Rouck, G.; et al. Description of the Temporal Dynamics in Microbial Community Composition and Beer Chemistry in Sour Beer Production via Barrel Ageing of Finished Beers. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 339, 109030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonsmeire, M. American Sour Beer: Innovative Techniques for Mixed Fermentations; Brewers Publications: Boulder, Colorado, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Spitaels, F.; Van Kerrebroeck, S.; Wieme, A.D.; Snauwaert, I.; Aerts, M.; Van Landschoot, A.; De Vuyst, L.; Vandamme, P. Microbiota and Metabolites of Aged Bottled Gueuze Beers Converge to the Same Composition. Food Microbiol. 2015, 47, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, M.; Hoalst-Pullen, N. The Geography of Beer: Regions, Environment, and Societies; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; ISBN 978-94-007-7787-3. [Google Scholar]

- Bokulich, N.A.; Thorngate, J.H.; Richardson, P.M.; Mills, D.A. Microbial Biogeography of Wine Grapes Is Conditioned by Cultivar, Vintage, and Climate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E139–E148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straka, D.; Hleba, L. Microbiological phases of spontaneously fermented beer. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Food Sci. 2022, 12, e9624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piraine, R.E.A.; Leite, F.P.L.; Bochman, M.L. Mixed-Culture Metagenomics of the Microbes Making Sour Beer. Fermentation 2021, 7, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roos, J.; Verce, M.; Aerts, M.; Vandamme, P.; De Vuyst, L. Temporal and spatial distribution of the acetic acid bacterium communities throughout the wooden casks used for the fermentation and maturation of lambic beer underlines their functional role. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e02846-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, H.; Dawoud, E.; Verachtert, H. Synthesis of Aroma Compounds by Wort Enterobacteria During the First Stage of Lambic Fermentation. J. Inst. Brew. 1992, 98, 421–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokulich, N.A.; Bamforth, C.W.; Mills, D.A. Brewhouse-resident microbiota are responsible for multi-stage fermentation of American coolship ale. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongaerts, D.; De Roos, J.; De Vuyst, L. Technological and environmental features determine the uniqueness of the lambic beer microbiota and production process. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, AEM0061221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roos, J.; De Vuyst, L. Microbial Acidification, Alcoholization, and Aroma Production during Spontaneous Lambic Beer Production. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postigo, V.; García, M.; Arroyo, T.; Postigo, V.; García, M.; Arroyo, T. Non-Conventional Saccharomyces Yeasts for Beer Production. In New Advances in Saccharomyces; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023; ISBN 978-0-85466-127-5. [Google Scholar]

- Canonico, L.; Agarbati, A.; Comitini, F.; Ciani, M. Torulaspora delbrueckii in the Brewing Process: A New Approach to Enhance Bioflavour and to Reduce Ethanol Content. Food Microbiol. 2016, 56, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rong, Y.; Yu, X.; Hong, K. Synergistic Effect Enhances Aromatic Profile in Beer Brewing through Mixed-Culture Fermentation of Pichia Kluyveri and Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. diastaticus. Fermentation 2025, 11, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larroque, M.N.; Carrau, F.; Fariña, L.; Boido, E.; Dellacassa, E.; Medina, K. Effect of Saccharomyces and Non-Saccharomyces Native Yeasts on Beer Aroma Compounds. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 337, 108953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Qin, Q.; Li, C.; Zhao, X.; Song, F.; An, M.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Huang, W.; Zhan, J.; et al. Application of Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts with High β-Glucosidase Activity to Enhance Terpene-Related Floral Flavor in Craft Beer. Food Chem. 2023, 404, 134726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morata, A.; Loira, I.; Tesfaye, W.; Bañuelos, M.A.; González, C.; Suárez Lepe, J.A. Lachancea thermotolerans Applications in Wine Technology. Fermentation 2018, 4, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steensels, J.; Daenen, L.; Malcorps, P.; Derdelinckx, G.; Verachtert, H.; Verstrepen, K.J. Brettanomyces Yeasts—From Spoilage Organisms to Valuable Contributors to Industrial Fermentations. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 206, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khablenko, A.; Danylenko, S.; Dugan, O.; Polishchuk, V.; Yalovenko, O.; Holubchyk, D. Biotechnological aspects of sour beer production. Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 18, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postigo, V.; O’Sullivan, T.; Elink Schuurman, T.; Arroyo, T. Non-conventional yeast: Behavior under pure culture, sequential and aeration conditions in beer fermentation. Foods 2022, 11, 3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senkarcinova, B.; Dias, I.A.G.; Nespor, J.; Branyik, T. Probiotic Alcohol-Free Beer Made with Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii. Lwt 2019, 100, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira de Paula, B.; de Souza Lago, H.; Firmino, L.; Fernandes Lemos Júnior, W.J.; Ferreira Dutra Corrêa, M.; Fioravante Guerra, A.; Signori Pereira, K.; Zarur Coelho, M.A. Technological Features of Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii for Potential Probiotic Wheat Beer Development. LWT 2021, 135, 110233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco, L.; Viñas, M.; Villa, T.G. Proteins Influencing Foam Formation in Wine and Beer: The Role of Yeast. Int. Microbiol. 2011, 14, 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Hiralal, L.; Olaniran, A.O.; Pillay, B. Aroma-Active Ester Profile of Ale Beer Produced under Different Fermentation and Nutritional Conditions. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2014, 117, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbelen, P.J.; Dekoninck, T.M.L.; Saerens, S.M.G.; Van Mulders, S.E.; Thevelein, J.M.; Delvaux, F.R. Impact of Pitching Rate on Yeast Fermentation Performance and Beer Flavour. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 82, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasuti, C.; Solieri, L. Yeast Bioflavoring in Beer: Complexity Decoded and Built up Again. Fermentation 2024, 10, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, D.W.K.; Chua, J.Y.; Liu, S.Q. Impact of Simultaneous Fermentation with Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Torulaspora delbrueckii on Volatile and Non-Volatile Constituents in Beer. LWT 2018, 91, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayadelen, F.; Agirman, B.; Jolly, N.P.; Erten, H. The Influence of Torulaspora delbrueckii on Beer Fermentation. FEMS Yeast Res. 2023, 23, foad006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaolesi, S.; Pérez-Través, L.; Pérez, D.; Roldán-López, D.; Briand, L.E.; Pérez-Torrado, R.; Querol, A. Identification and Assessment of Non-Conventional Yeasts in Mixed Fermentations for Brewing Bioflavored Beer. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 399, 110254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourbon-Melo, N.; Palma, M.; Rocha, M.P.; Ferreira, A.; Bronze, M.R.; Elias, H.; Sá-Correia, I. Use of Hanseniaspora guilliermondii and Hanseniaspora opuntiae to Enhance the Aromatic Profile of Beer in Mixed-Culture Fermentation with Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Food Microbiol. 2021, 95, 103678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, E.; Azevedo, M.; Teixeira, J.A.; Tavares, T.; Oliveira, J.M.; Domingues, L. Evaluation of Multi-Starter S. cerevisiae/D. bruxellensis Cultures for Mimicking and Accelerating Transformations Occurring during Barrel Ageing of Beer. Food Chem. 2020, 323, 126826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capece, A.; Romaniello, R.; Siesto, G.; Romano, P. Conventional and Non-Conventional Yeasts in Beer Production. Fermentation 2018, 4, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granato, T.M.; Romano, D.; Vigentini, I.; Foschino, R.C.; Monti, D.; Mamone, G.; Ferranti, P.; Nitride, C.; Iametti, S.; Bonimi, F.; et al. New insights on the features of the vinyl phenol reductase from the wine-spoilage yeast Dekkera/Brettanomyces bruxellensis. Ann. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hranilovic, A.; Gambetta, J.M.; Schmidtke, L.; Boss, P.K.; Grbin, P.R.; Masneuf-Pomarede, I.; Pely, M.; Albertin, W.; Jiranek, V. Oenological traits of Lachancea thermotolerans show signs of domestication and allopatric differentiation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belda, I.; Ruiz, J.; Esteban-Fernández, A.; Navascués, E.; Marquina, D.; Santos, A.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V. Microbial Contribution to Wine Aroma and Its Intended Use for Wine Quality Improvement. Molecules 2017, 22, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, M.D.; Moreno, H.; Calvo, J.R. Melatonin Present in Beer Contributes to Increase the Levels of Melatonin and Antioxidant Capacity of the Human Serum. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 28, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, R.; Bernasconi, P.; Fowler, D.; Gautreaux, M. Inhibition of Candida albicans Translocation from the Gastrointestinal Tract of Mice by Oral Administration of Saccharomyces Boulardii. J. Infect. Dis. 1993, 168, 1314–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertuzzi, T.; Mulazzi, A.; Rastelli, S.; Donadini, G.; Rossi, F.; Spigno, G. Targeted Healthy Compounds in Small and Large-Scale Brewed Beers. Food Chem. 2020, 310, 125935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, M.E.; Merenstein, D.; Merrifield, C.A.; Hutkins, R. Probiotics for Human Use. Nutr. Bull. 2018, 43, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulero-Cerezo, J.; Briz-Redón, Á.; Serrano-Aroca, Á. Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii: Valuable probiotic starter for craft beer production. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comitini, F.; Canonico, L.; Agarbati, A.; Ciani, M. Biocontrol and Probiotic Function of Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts: New Insights in Agri-Food Industry. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suiker, I.M.; Wösten, H.A. Spoilage Yeasts in Beer and Beer Products. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 44, 100815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo Piraine, R.E.; Nickens, D.G.; Sun, D.J.; Leivas Leite, F.P.; Bochman, M.L. Isolation of Wild Yeasts from Olympic National Park and Moniliella megachiliensis ONP131 Physiological Characterization for Beer Fermentation. Food Microbiol. 2022, 104, 103974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majeed, M.; Majeed, S.; Nagabhushanam, K.; Arumugam, S.; Beede, K.; Ali, F. Evaluation of Probiotic Bacillus coagulans MTCC 5856 Viability after Tea and Coffee Brewing and Its Growth in GIT Hostile Environment. Food Res. Int. 2019, 121, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellor, D.D.; Hanna-Khalil, B.; Carson, R. A Review of the Potential Health Benefits of Low Alcohol and Alcohol-Free Beer: Effects of Ingredients and Craft Brewing Processes on Potentially Bioactive Metabolites. Beverages 2020, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannini, E.; Bravo Núñez, Á.; Sahin, A.W.; Arendt, E.K. Arabinoxylans as Functional Food Ingredients: A Review. Foods 2022, 11, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postigo, V.; García, M.; Crespo, J.; Canonico, L.; Comitini, F.; Ciani, M. Bioactive Properties of Fermented Beverages: Wine and Beer. Fermentation 2025, 11, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boro, N.; Borah, A.; Sarma, R.L.; Narzary, D. Beer Production Potentiality of Some Non-Saccharomyces Yeast Obtained from a Traditional Beer Starter Emao. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2022, 53, 1515–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methner, Y.; Weber, N.; Kunz, O.; Zarnkow, M.; Rychlik, M.; Hutzler, M.; Jacob, F. Investigations into Metabolic Properties and Selected Nutritional Metabolic Byproducts of Different Non-Saccharomyces Yeast Strains When Producing Nonalcoholic Beer. FEMS Yeast Res. 2022, 22, foac042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, F.F.; Striegel, L.; Rychlik, M.; Hutzler, M.; Methner, F.-J. Yeast Extract Production Using Spent Yeast from Beer Manufacture: Influence of Industrially Applicable Disruption Methods on Selected Substance Groups with Biotechnological Relevance. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2019, 245, 1169–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, E.F.; Carvalho, J.; Pinto, E.; Cunha, S.; Almeida, A.A.; Ferreira, I.M.P.L.V.O. Nutritive Value, Antioxidant Activity and Phenolic Compounds Profile of Brewer’s Spent Yeast Extract. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2016, 52, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, I.M.P.L.V.O.; Pinho, O.; Vieira, E.; Tavarela, J.G. Brewer’s Saccharomyces Yeast Biomass: Characteristics and Potential Applications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 21, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamforth, C.W. Nutritional Aspects of Beer—A Review. Nutr. Res. 2002, 22, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, O., Jr.; Šimon, J.; Rosolová, H. A Population Study of the Influence of Beer Consumption on Folate and Homocysteine Concentrations. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 55, 605–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zugravu, C.-A.; Medar, C.; Manolescu, L.S.C.; Constantin, C. Beer and Microbiota: Pathways for a Positive and Healthy Interaction. Nutrients 2023, 15, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaštík, P.; Rosenbergová, Z.; Furdíková, K.; Klempová, T.; Šišmiš, M.; Šmogrovičová, D. Potential of Non-Saccharomyces Yeast to Produce Non-Alcoholic Beer. FEMS Yeast Res. 2022, 22, foac039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.-H.; Lin, Y.-C.; Lin, Y.-W.; Zhang, Y.-W.; Huang, D.-W. The Potential of Co-fermentation with Pichia kluyveri and Saccharomyces cerevisiae for the Production of Low-Alcohol Craft Beer. Foods 2024, 13, 3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabvandi, S.; Mousavi, M.; Razavi, S.; Mortazavian, A. Application of advanced instrumental techniques for analysis of physical and physicochemical properties of beer: A review. Int. J. Food Prop. 2010, 13, 744–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Francesco, G.; Sannino, C.; Sileoni, V.; Marconi, O.; Filippucci, S.; Tasselli, G.; Turchetti, B. Mrakia gelida in Brewing Process: An Innovative Production of Low Alcohol Beer Using a Psychrophilic Yeast Strain. Food Microbiol. 2018, 76, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellut, K.; Michel, M.; Zarnkow, M.; Hutzler, M.; Jacob, F.; Atzler, J.J.; Hoehnel, A.; Lynch, K.M.; Arendt, E.K. Screening and Application of Cyberlindnera Yeasts to Produce a Fruity, Non-Alcoholic Beer. Fermentation 2019, 5, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, A.; Allende, A.; Bolton, D.; Chemaly, M.; Davies, R.; Girones, R.; Herman, L.; Koutsoumanis, K.; Lindqvist, R.; Nørrung, B.; et al. Scientific Opinion on the Update of the List of QPS-Recommended Biological Agents Intentionally Added to Food or Feed as Notified to EFSA. EFSA J. 2017, 15, e04664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miguel, G.A.; Carlsen, S.; Arneborg, N.; Saerens, S.M.; Laulund, S.; Knudsen, G.M. Non-Saccharomyces yeasts for Beer Production: Insights into Safety Aspects and Considerations. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 383, 109951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaczyński, P.; Iwaniuk, P.; Hrynko, I.; Łuniewski, S.; Łozowicka, B. The effect of the multi-stage process of wheat beer brewing on the behavior of pesticides according to their physicochemical properties. Food Control 2024, 160, 110356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.