Abstract

Objectives: This study aimed to assess the effects of storage temperature on the lipidomics profile change in Pacific saury (Cololabis saira). Methods: In this paper, C. saira underwent frozen storage at two different temperatures, T1 (−18 °C) and T2 (−25 °C), for a duration of three months. Chemical and lipidomic methods were used to determine the changes in lipids during the storage process. Results: Results showed that the content of triglyceride and phospholipid decreased significantly (p < 0.05), and free fatty acid increased significantly (p < 0.05), while the content of total cholesterol remained relatively constant across different storage temperatures. Additionally, an increasing trend in AV, POV, and TBARS contents was observed after the freezing process, with lipid oxidation being significantly higher in the −18 °C group compared to the −25 °C group (p < 0.05). A comprehensive analysis identified 4854 lipid molecules in the muscles of C. saira, categorized into 46 lipid subclasses, predominantly including triglycerides (TG), phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylinositol (PI), phosphatidylglycerol (PG), and diglycerides (DG). Among them, TG was the most abundant lipid, followed by PC. Using orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) with a variable importance in projection (VIP) score > 1 and p value < 0.05 as criteria, 338, 271, and 103 highly significantly differentiated lipids were detected in the comparison groups CK vs. T1, CK vs. T2, and T1 vs. T2, respectively. The results indicated that storage at −18 °C had a more pronounced effect than storage at −25 °C. During the freezing process, TG expression was significantly down-regulated, and TG(18:4_14:0_20:5), TG(20:5_13:0_22:6), TG(22:6_14:1_22:6), and TG(18:4_13:0_22:6) were the most predominant individuals. The CK group was initially present in C. saira before storage. Differential lipid molecules in the CK vs. T1 and CK vs. T2 groups were screened using a fold change (FC) > 2 or FC < 0.5. In the CK vs. T2 group, 102 highly significant differential lipid molecules were identified, with 55 being down-regulated across seven subclasses. In contrast, the CK vs. T1 group revealed 254 highly significant differential lipid molecules, with 85 down-regulated across 13 subclasses. The results showed that more PCs and PEs were down-regulated, with a higher differential abundance of PE and PC in the −25 °C group compared to the −18 °C group. The differential metabolites were primarily enriched in 17 metabolic pathways, with glycerophospholipid metabolism being the most prominent, followed by sphingolipid metabolism during the frozen storage. Conclusions: Overall, −25 °C storage in production was more favorable for maintaining the lipid stability of C. saira. This work could provide useful information for aquatic product processing and lipidomics.

1. Introduction

Cololabis saira is a significant pelagic fish, which is widely distributed in the subtropical and temperate waters of the Pacific Ocean along the coasts of Asia and America [1]. In 2022, China’s commercial harvest of C. saira reached 35,477 tons [2]. C. saira is rich in protein, lipids, and other essential nutrients, and is particularly abundant in omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids [3,4,5]. The origin of C. saira is far from inland China, and it needs to undergo a long period of freezing and transport. Currently, sales of C. saira primarily consists of primary processed products such as frozen items, with fewer deep-processed products available, including convenient ready-to-eat pieces, canned, and boneless C. saira.

Freezing is one of the most widely used methods for preserving marine foods [6]. Currently, the standard storage temperature for most aquatic products in China is set at −18 °C. However, this temperature has not been optimal for lipid-rich aquatic products. For instance, the ideal freezing temperature for Atlantic salmon ranges between −45 °C and −60 °C [7]. Similarly, tuna requires storage and transportation at a minimum of −55 °C [8]. These specific temperature requirements are essential to slow down the deterioration in quality.

Although it partially inhibits most of the processes leading to quality deterioration, it does not completely prevent lipid oxidation and unfavorable changes in lipid quality and sensory properties [9]. A series of changes have occurred in fish meat during storage and processing, such as protein denaturation and lipid oxidation [10,11]. Many studies on C. saira have focused on lipid and flavor changes during processing [10,12,13] and the effects of natural antioxidants on lipid oxidation [4,12], but little work has been conducted on lipid oxidation of C. saira at different freezing temperatures; that is, apart from Tanaka et al. [14], who have investigated the quality changes of C. saira under different temperature storage conditions. However, comprehensive lipidomic profile differences due to the storage process had not been analyzed until now. Temperatures of −18 °C and −25 °C are commonly used in actual production. In this study, an untargeted lipidomic strategy was used to investigate the effect of storage temperature on lipid composition and lipid molecules during a −18 °C and −25 °C freezing storage process over three months. We screened the different lipids during storage at different temperatures and explored their metabolic pathways by detecting the dynamic changes in lipid profiles. This study aims to enhance the understanding of lipid profile changes during different frozen storage conditions and provide data support for the actual production of C. saira. Additionally, it offers a theoretical basis for the quality control of pelagic fishery catches.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

A quantity of 180 kg of Cololabis saira was purchased from Penglai Jinglu Fisheries Co., Ltd. (Penglai, China) for this study. It was harvested from the North Pacific Ocean and initially frozen at −35 °C on the fishing vessel. The transportation from the North Pacific Ocean to China typically needed two or three months, during which the temperature was maintained at −18 °C. Upon arrival at Yantai port, C. saira were promptly transferred to the laboratory for further processing. The initial C. saira was labeled as CK, and the following fish were placed at −18 °C (labeled as T1) and −25 °C (labeled as T2) for frozen storage, respectively. In total, 60 kilogram fish were placed in storage for each group.

2.2. Reagents

Chloroform, methanol, isopropanol, sodium chloride, trichloroacetic acid (TCA), 95% ethanol, sodium hydroxide, sodium thiosulfate, acetic acid, starch indicator, potassium iodide, Triton X100, petroleum ether, thiobarbituric acid (TBA), toluene, copper acetate pyridine, ammonium formate, concentrated nitric acid, perchloric acid, and anhydrous sodium sulfate were analytically pure (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). MS-grade methanol, MS-grade acetonitrile, and HPLC-grade 2-propanol were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. (Waltham, MA, USA). HPLC-grade formic acid and HPLC-grade ammonium formate were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.3. Lipid Composition and Lipid Oxidation Assay

The lipid composition of C. saira was analyzed at monthly intervals over a three-month period. Referring to the method of Wang et al. [15], 0.1 to 0.2 g of the total lipid sample was added to 20 mL digestive solution for wet digestion, the volume ratio of which (concentrated nitric acid and perchloric acid) was 4:1. Digestion continued until the digestive solution was essentially colorless. The digestion was fixed to 50 mL, and the phospholipid (PL) content in the total lipids was determined by the molybdenum blue colorimetric method. In total, 100 µL total lipid sample was diluted to the appropriate concentration. The diluted solution was made of isopropanol and TritonX100; its volume mass ratio was 9:1. Triglyceride (TG) and total cholesterol (TC) content were determined by following the kit instructions. Amounts of 5 mL of toluene and 1 mL of copper reagent (pH 6.1) were added to 0.10 g of the total lipid sample, and shaken for 2 min. Centrifugation was performed at 1000× g for 5 min, and the supernatant was taken to determine the Optical Density (OD) value at 715 nm. The standard curve was plotted with oleic acid to calculate the free fatty acid (FFA) content in the C. saira samples. Lipid oxidation of C. saira samples were assessed by measuring the acid value (AV), peroxide value (POV), and thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARSs). AV was determined according to a thermal ethanol method of the Chinese standard GB 5009.229-2016 [16]. POV was determined by a titrimetric method of the Chinese standard GB 5009.227-2016 [17]. TBARSs were determined according to the spectrophotometric method of the Chinese standard GB 5009.181-2016 [18]. The detailed procedures of the assay methods can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

2.4. Determination of Lipid Profile

2.4.1. Lipid Extraction

The lipidomic analysis was conducted at the end of the storage period (the third month), and the tissue of C. saira was rapidly frozen using liquid nitrogen and subsequently stored at −80 °C. Lipids of C. saira were extracted according to the Methyl tert-Butyl Ether (MTBE) method [19]. Briefly, a 200 µL volume of water was added to the sample, and then the sample was vortexed for 5 s. Subsequently, 240 µL of precooling methanol was added and the mixture was vortexed for 30 s. After that, 800 µL MTBE was added and the mixture was ultrasonicated for 20 min at 4 °C followed by sitting still for 30 min at room temperature. The solution was centrifuged at 14,000× g for 15 min at 10 °C and the upper organic solvent layer was obtained and dried under nitrogen.

2.4.2. LC-MS/MS Method for Lipid Analysis

Reverse-phase chromatography was selected for LC separation using a CSH C18 column (1.7 µm, 2.1 mm × 100 mm, Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA). The lipid extracts were re-dissolved in 200 µL 90% isopropanol/acetonitrile, centrifuged at 14,000× g for 15 min, and, finally, 3 µL of sample was injected. Solvent A was acetonitrile–water (6:4, v/v) with 0.1% formic acid and 0.1 mM ammonium formate and solvent B was acetonitrile–isopropanol (1:9, v/v) with 0.1% formic acid and 0.1 mM ammonium formate. The initial mobile phase was 30% solvent B at a flow rate of 300 μL/min. It was held for 2 min, and then linearly increased to 100% solvent B in 23 min, followed by equilibrating at 5% solvent B for 10 min.

Mass spectra were acquired by Thermo Fisher Q-Exactive Plus in positive and negative modes. ESI parameters were optimized and preset for all measurements as follows: source temperature, 300 °C; capillary temp, 350 °C; the ion spray voltage for positive and negative ions was set at 3000 V; the S-Lens RF Level was set at 50%; and the scan range of the instruments was set at m/z 200–1800.

2.4.3. Identification by Lipid Search

Lipid Search software version 4.2 (Thermo Scientific™) was used to identify the lipid molecules and lipid species based on MS/MS calculations [20]. It contains more than 30 lipid classes and more than 1,500,000 ion fragments in the database. Adducts of +H and +NH4 were selected for positive mode searches, and −H and +CH3COO were selected for negative mode searches since ammonium acetate was used in the mobile phases. Both mass tolerances for the precursor and fragment were set to 5 ppm, with a product ion threshold of 5%.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The experimental data for lipid composition and oxidation were analyzed using SPSS 22.0 software, and significant differences were analyzed with Duncan’s multiple range test at p < 0.05. All lipidomic measurements were conducted in eight replicates. Regarding the data extracted from Lipid Search, lipids with a relative standard deviation (RSD) greater than 30% and missing values greater than 50% in each group were removed. After normalization and integration using the Perato scaling method, the processed data were imported into SIMPCA-P 16.0 (Umetrics, Umea, Sweden) for principal component analysis (PCA).

3. Results

3.1. Lipid Composition Change and Lipid Oxidation Analysis of C. saira at Different Storage Temperatures

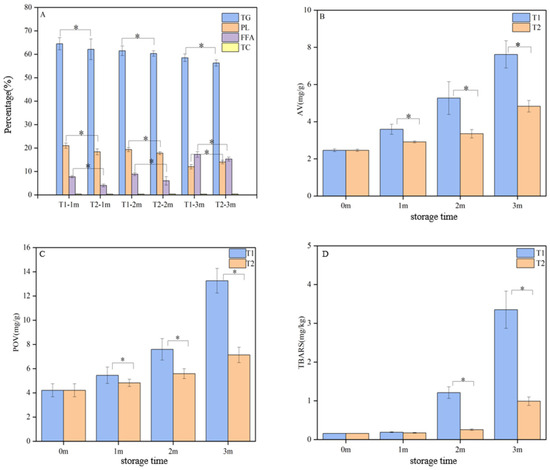

Figure 1A illustrates the lipid composition of C. saira at various storage temperatures, providing insights into the evolution of lipids during the frozen storage process. Similarly to most marine fish, the lipid composition of C. saira was predominantly comprised of TG and PL, with smaller quantities of FFA and very low levels of TC. During storage, the contents of TG and PL decreased significantly (p < 0.05), while FFA levels increased significantly (p < 0.05). However, the TC content remained relatively constant at different storage temperatures. Notably, the changes in lipid composition were more pronounced in the T1 group (−18 °C) compared to the T2 group (−25 °C), suggesting that storage temperature significantly influences lipid composition. Consequently, a storage temperature of −25 °C was more suitable for the long-term frozen storage of C. saira.

Figure 1.

Lipid composition (A) and lipid oxidation (B–D) analysis of C. saira at different storage temperatures; asterisks indicate statistical significance (* p < 0.05).

To assess the levels of primary and secondary oxidation products during the lipid oxidation process, AV, POV, and TBARS were utilized as key indicators [21]. Figure 1 illustrates the lipid oxidation of C. saira at various frozen storage temperatures. It is evident that lipid oxidation was typically unavoidable during frozen storage, leading to significant increases in the AV, POV, and TBARS values of C. saira.

Figure 1B illustrates the changes in the AV of C. saira at various storage temperatures, revealing a gradual increase in AV with the extension of the storage period. Notably, the AV in the T1 group increased significantly more than in the T2 group (p < 0.05). This observation aligned with the results from the lipid composition analysis, suggesting a potential link to the hydrolysis of TC and PL. Furthermore, the rate of lipid hydrolysis was influenced by several factors, including the moisture content and its state within the samples, as well as the activity of endogenous lipase and other variables [22,23]. POV was an index used to determine the content of primary oxidation products, such as hydroperoxides, which can reflect the degree of the primary oxidation of lipids [24]. Aquatic products, such as C. saira, are rich in unsaturated fatty acids, which were prone to oxidative decomposition during storage, leading to the formation of malondialdehyde. The TBARS assay was utilized to evaluate lipid secondary oxidation by measuring the malondialdehyde content produced during this process [25]. Lipid oxidation was generally unavoidable during transportation or storage, resulting in significant increases in both POV and TBARS values in C. saira. Figure 1C,D illustrate the changes in POV and TBARSs, respectively, at different storage temperatures. The POV and TBARS values of the T1 group increased significantly compared to the T2 group (p < 0.05).

Overall, an increasing trend in AV, POV, and TBARS contents was observed during the freezing process. These results indicated that storage at −25 °C is more conducive to the preservation of C. saira.

3.2. Lipidomics Analysis of C. saira at Different Storage Temperatures

During the storage process, lipid oxidation can be influenced by various factors, including temperature, duration, and packaging. When lipid peroxidation occurs, the appearance of C. saira may become tawny, and it may develop an unpleasant odor or a hard texture, which negatively impacts consumer sensory acceptability. Therefore, understanding the fundamental processes and mechanisms of lipid oxidation is crucial for ensuring the storage stability of C. saira.

Table 1 presented the statistical results obtained from both positive and negative ion modes. In the muscles of Cololabis saira, a total of 4854 lipid molecules were identified and categorized into 46 lipid subclasses. These subclasses primarily included triglycerides (TG), phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylinositol (PI), phosphatidylglycerol (PG), and diglycerides (DG). Notably, TG was the most abundant lipid in C. saira, serving as the primary storage form of fatty acids in organisms, as well as an essential energy source and carrier [26]. PC was the second most prevalent lipid, recognized as a major component of fish phospholipids, and it plays a critical role in maintaining cell membrane permeability and structural integrity [27].

Table 1.

Number of lipid subclasses and compounds.

3.3. Multivariate Statistical Analysis of C. saira at Different Storage Temperatures

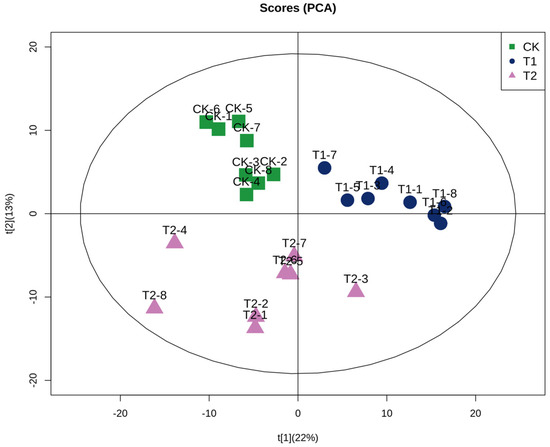

In order to elucidate the changes in the lipid profile of C. saira under different storage temperatures and identify potential differences in lipid types, a principal component analysis (PCA) model was established, as illustrated in Figure 2. The figure demonstrated the distribution of the lipid profiles in the three groups of C. saira, from which it could be seen that the distribution of the same group of C. saira was concentrated in a region. The samples of TI and T2 groups were dispersed in different regions and far away from each other, which indicated that there were significant differences in the lipid profiles of the T1 and T2 group of C. saira, and further confirmed that storage temperature has a substantial effect on the lipid profiles of C. saira.

Figure 2.

Principal component analysis.

3.4. Differentially Abundant Lipid Analysis

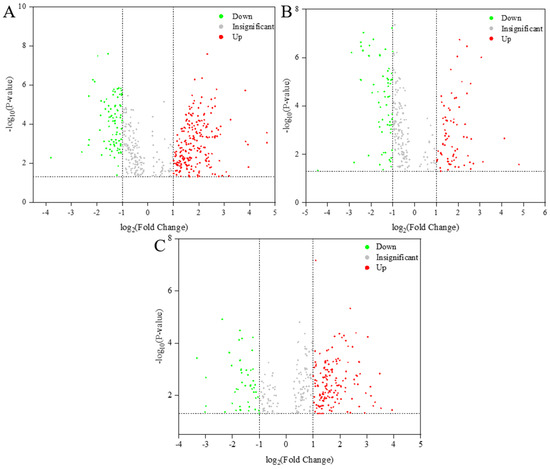

In lipidomics studies, a high Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) score combined with a low p-value has indicated significant differences in target lipid samples [28]. By employing Orthogonal Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA) with VIP > 1 and p-value < 0.05 as the criteria, we identified highly significantly differentiated lipid molecules (Figure 3). Specifically, 338, 271, and 103 highly significantly differentiated lipids were detected in the comparison groups CK vs. T1, CK vs. T2, and T1 vs. T2, respectively. Figure 3 presented volcano plots of the three comparison groups, illustrating the changes in lipid compounds. In these plots, each point represents a lipid compound, with larger values along the horizontal and vertical axes indicating more significant alterations in the selected lipid compounds. The figure reveals that the relative contents of most lipid metabolites were either significantly up-regulated or down-regulated across the three sample groups. These findings suggested that the most pronounced differences in the lipid composition of C. saira occurred during T1 storage. The results indicated that the T1 group storage had a more substantial impact on lipid quality compared to the T2 group.

Figure 3.

Volcano plot of differential lipid molecules in CK versus T1 sample (A), CK versus T2 sample (B), T1 versus T2 sample (C).

The lipid molecules that were either up-regulated or down-regulated in the CK vs. T1 and CK vs. T2 groups were identified using a fold change (FC) criterion of >2 or <0.5. The analysis revealed that the down-regulation of triglycerides (TG) was the main reason for the changes in the lipid profiles of C. saira during storage, and thus the lipid compounds that were down-regulated lipid molecules in the different comparison groups were listed in Table 2 and Table 3, separately. In the CK vs. T2 group, 102 highly significant differential lipid molecules were detected, with 55 being down-regulated. These down-regulated molecules belonged to seven subclasses, including 40 species of TG, 4 species of sphingomyelins (SM), 3 species of sterols (ST), 3 species of sphingolipids (SPH), 3 species of PI, 1 species of PG, and 1 species of phosphatidylserine (PS). In comparison, the CK vs. T1 group exhibited 254 highly significant differential lipid molecules, with 85 being down-regulated across 13 subclasses. These included 33 species of TG, 17 species of PE, 11 species of phosphatidylcholines (PC), 5 species of PI, 5 species of ST, 4 species of PG, 2 species of SPH, 2 species of SM, 2 species of cardiolipins (CL), 1 species of LPE, 1 species of Dihexosylceramide (Hex2Cer), 1 species of DG, and 1 species of Phosphatidylserine (PS). This suggested a more complex lipid metabolism in this reservoir. These lipid compounds could also serve as differentiating factors. The findings indicated that the lipid profiles of C. saira were significantly influenced by different storage temperatures, aligning with previous studies on lipid content and oxidation.

Table 2.

Changes in significantly different lipid molecules in CK vs. T1 group during storage process.

Table 3.

Changes in significantly different lipid molecules in CK vs. T2 group during storage process.

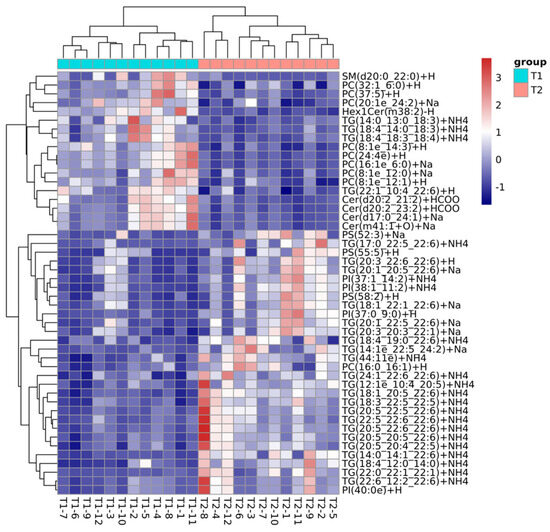

During the freezing storage process, the expression of TG was significantly down-regulated (Figure 4), primarily decomposing into FFA, DG, and monoglycerides (MG). These metabolites served as energy sources and substrates for the proliferation of cryophilic microorganisms, facilitating microbial growth [26]. TG(18:4_14:0_20:5), TG(20:5_13:0_22:6), TG(22:6_14:1_22:6), and TG(18:4_13:0_22:6) were the most predominant species. The freezing storage process also led to an increase in AV, POV, and TBARSs, indicating a comparative deterioration of the lipid profiles in C. saira. This reduction in TG levels can be attributed to oxidative degradation, which is triggered by hydrolysis due to the enzymatic action of lipases [28]. This process might convert TG into substances such as DG, while simultaneously releasing fatty acids [29]. DG, an intermediate product of lipid metabolism, is closely associated with the biosynthesis and catabolism of TG [30]. Notably, the T1 and T2 groups exhibited two up-regulated DG lipid species. PE and PC played crucial roles in regulating energy, lipid metabolism, and lipoprotein secretion [31]. The expression of functional ingredients such as PE, PC, and PI was also significantly down-regulated, suggesting their conversion to lysophosphatidylethanolamine (LPE), lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), and lysophosphatidylinositol (LPI), respectively, through pathways such as partial hydrolysis or lipid oxidation [27]. These findings underscored the critical role of lipid oxidation in lipid transformations during the freezing storage process of C. saira, in accordance with the results of previous studies [22,32].

Figure 4.

The correlation analysis between the lipid metabolites and different frozen storage temperature.

Comprehensive analysis of the differential lipids at freezing temperatures of −18 °C and −25 °C revealed significant findings regarding lipid regulation and oxidation in muscle tissue. The study found that more phosphatidylcholines (PCs) and phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) exhibited down-regulation, likely due to oxidation reactions in muscle tissue. These reactions may cause hydrogen rearrangement on the PC/PE chains and lead to the breakage of the C-C layer of α-bonds [33]. Notably, the differential abundance of PE and PC was higher in the −25 °C group compared to the −18 °C group, indicating that a freezing temperature of −25 °C could more effectively inhibit lipid oxidation in the muscle of C. saira. These results underscored the significant impact of different freezing storage temperatures on the lipid profile, with −25 °C being more favorable for the frozen storage of C. saira. This finding aligned with previous results concerning lipid composition and oxidation.

3.5. Lipid Metabolic Pathway Analysis of C. saira During Storage Process

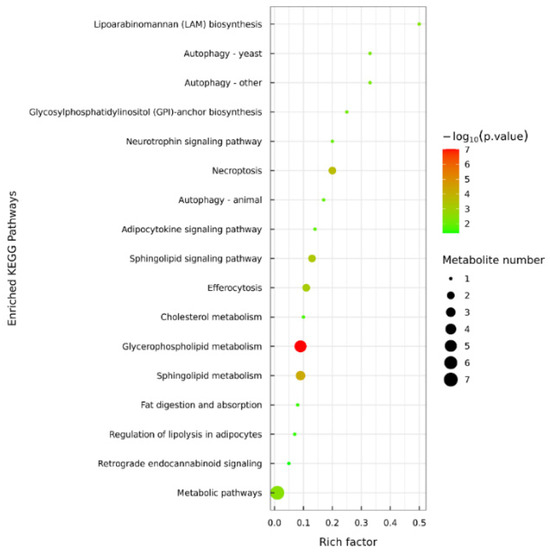

The analysis of metabolic pathways provided insights into how frozen storage temperatures affect lipid distribution in samples, as indicated in previous studies [6]. Utilizing the KEGG database, the pathway annotation analysis of lipid differential metabolites in C. saira at varying storage temperatures was depicted in Figure 5. Comparative analysis revealed that these differential metabolites were predominantly enriched in 17 metabolic pathways of the T1 (−18 °C) vs. T2 (−25 °C) group. Among these, glycerophospholipid metabolism emerged as the primary pathway enriched during the frozen storage process. Key lipid components such as phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylinositol (PI), and phosphatidylserine (PS) were annotated within this pathway. These lipids were crucial as they constitute major components of cell membranes, thereby maintaining cellular physiological functions and facilitating the transport of triglycerides [34]. Additionally, sphingolipid metabolism was identified as another significant pathway enriched during frozen storage, with ceramide (Cer) and sphingomyelin (SM) being the two significantly different lipid metabolites annotated in this pathway. Further investigation into the lipid oxidation pathway is necessary, in conjunction with metabolomics, to uncover the potential key lipid molecules involved in the storage process of C. saira.

Figure 5.

KEGG pathway analysis of highly significant differential lipids in T1 vs. T2 group.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, the findings indicated that storage temperature had a significant influence on the lipid stability of C. saira during the frozen storage process. The lipid stability of C. saira stored at −18 °C was much worse than that at −25 °C. Thus, −25 °C storage was more conducive to maintain the storage stability of C. saira in production. The study will provide valuable insights into production quality control of pelagic fishery catches.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/foods14050756/s1, Determination of lipid oxidation.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, visualization, investigation, L.Z.; data curation, S.W.; conceptualization, project administration, Q.L.; methodology, D.S. and Y.Z.; funding acquisition, R.C.; supervision, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Plan (No. 2020YFD0901203) and Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund, CAFS (No. 2023TD72).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, X. International fisheries dynamics. Fish. Inf. Strategy 2023, 38, 317–324. [Google Scholar]

- NPFC. NPFC-2023-AR-Annual Summary Footprint-Pacific Saury. 2023. Available online: https://www.npfc.int/summary-footprint-pacific-saury-fisheries (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Zhang, J.; Tao, N.; Wang, M.; Shi, W.; Ye, B.; Wang, X.; Zhu, Q.; Hua, C. Characterization of phospholipids from Pacific saury (Cololabis saira) viscera and their neuroprotective activity. Food Biosci. 2018, 24, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.M.; Yang, G.Q.; Zhao, Q.; Li, H.Y.; Niu, L.H.; Wu, H.Y.; Yu, H. Antioxidant effects of Stevia rebaudiana leaf and stem extracts on lipid oxidation in salted Pacific Saury (Cololabis saira) during processing. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2022, 124, 210022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.Y.; Yin, M.Y.; Liu, L.; Song, R.Z.; Wang, X.D.; Tao, N.P.; Wang, X.C. UPLC-ESI-MS/MS strategy to analyze fatty acids composition and lipid profiles of Pacific saury (Cololabis saira). Food Chem. X 2024, 23, 101682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suárez-Medina, M.D.; Sáez-Casado, M.; Martínez-Moya, T.; Rincón-Cervera, M.Á. The Effect of Low Temperature Storage on the Lipid Quality of Fish, Either Alone or Combined with Alternative Preservation Technologies. Foods 2024, 13, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Indergård, E.; Tolstorebrov, I.; Larsen, H.; Eikevik, T.M. The influence of long-term storage, temperature and type of packaging materials on the quality characteristics of frozen farmed Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar). Int. J. Refrig. 2014, 41, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, W.Q.; Liu, L.; Xiao, L.; Mei, J.; Xie, J. Effect of Temperature Fluctuation on the Quality of Big-Eye Tuna (Thunnus obesus) during Low Temperature Circulation. Food Sci. 2021, 42, 205–212. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Wang, L.; Cao, R.; Liu, Q.; Su, D.; Zhang, Y.T.; Yu, Y.Q. The role of ultraviolet radiation in the flavor formation during drying processing of Pacific saury (Cololabis saira). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 8099–8108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.Y.; Chen, Y.; Gong, Y.S. Improvement of Theaflavins on Glucose and Lipid Metabolism in Diabetes Mellitus. Foods 2024, 13, 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Sun, W.C.; Luo, Y.H. Research progress in detection and function of sphingomyelin in food. Food Res. Dev. 2020, 41, 211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, H.B.; Wang, W.H.; Chen, W.; Tang, H.Q.; Jiang, L.; Yu, Z.F. Effect of incorporation of natural chemicals in water ice-glazing on freshness and shelf-life of Pacific saury (Cololabis saira) during −18 °C frozen storage. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 9, 3309–3314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, K.H.; Wang, Y.F.; Luan, D.L. Effects of high-temperature short-time processing on nutrition quality of Pacific saury (Cololabis saira) using extracted fatty acids as the indicator. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 1, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, R.; Naiki, K.; Tsuji, K.; Nomata, H.; Sugiura, Y.; Matsushita, T.; Kimura, I. Effect of antioxidative treatment on lipid oxidation in skinless fillet of Pacific Saury (Cololabis saira) in frozen storage. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2013, 37, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Y.; Jian, C.; Hu, M.Y.; Zhao, L.; Sun, H.H.; Liu, Q.; Cao, R.; Xue, Y. Lipid changes and volatile compounds formation in different processing stages of dry-cured Spanish mackerel. Food Qual. Saf. 2024, 8, fyae026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 5009.181-2016; National Standards for Food Safety Determination of Malondialdehyde in Food. The National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2016.

- GB 5009.227-2016; National Standards for Food Safety Determination of Peroxide Value in Food. The National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2016.

- GB 5009.229-2016; National Standards for Food Safety Determination of Acid Value in Food. The National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Shi, C.P.; Guo, H.; Wu, T.T.; Tao, N.P.; Wang, X.C.; Zhong, J. Effect of three types of thermal processing methods on the lipidomics profile of tilapia fillets by UPLC-Q-Extractive Orbitrap mass spectrometry. Food Chem. 2019, 298, 125029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.Q.; Zhao, M.T.; Wang, X.W.; Li, C.; Liu, Z.Y.; Shen, X.R.; Zhou, D.Y. Investigation of oyster Crassostrea gigas lipid profile from three sea areas of China based on non-targeted lipidomics for their geographic region traceability. Food Chem. 2022, 386, 132748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, X.C.; Ding, Y.T.; Ke, Z.G.; Zhou, X.X.; Zhang, J.Y. Diversity and succession of the microbial community and its correlation with lipid oxidation in dry-cured black carp (Mylopharyngodon piceus) during storage. Food Microbiol. 2021, 98, 103686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.D.; Chen, H.S.; Yan, H.B.; Shui, S.S.; Benjakul, S.; Zhang, B. Investigation of the changes in the lipid profiles in hairtail (Trichiurus haumela) muscle during frozen storage using chemical and LC/MS-based lipidomics analysis. Food Chem. 2022, 390, 133140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, A.; Caputo, S.; Pantusa, M.; Perri, E.; Sindona, G.; Sportelli, L. Amino acids as modulators of lipoxygenase oxidation mechanism. The identification and structural characterization of spin adducts intermediates by electron spin resonance and tandem mass spectrometry. Food Chem. 2010, 119, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Cai, Z.C.; Sang, X.H.; Deng, W.T.; Zeng, L.X.; Wang, J.M.; Zhang, J.H. LC-MS-based lipidomics analyses of alterations in lipid profiles of Asian sea bass (Lates calcarifer) induced by plasma-activated water treatment. Food Res. Int. 2024, 177, 113866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soyer, A.; Özalp, B.; Dalmıs, Ü.; Bilgin, V. Effects of freezing temperature and duration of frozen storage on lipid and protein oxidation in chicken meat. Food Chem. 2010, 120, 1025–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.L.; Ren, S.J.; Shen, Q.; Ye, X.Q.; Chen, J.C.; Ling, J.G. Protein oxidation and proteolysis during roasting and in vitro digestion of fish (Acipenser gueldenstaedtii). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 5344–5351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Kong, Q.; Sun, Z.T.; Liu, J.Y. Freshness analysis based on lipidomics for farmed Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) stored at different times. Food Chem. 2022, 373, 131564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zang, M.W.; Cheng, X.Y.; Wang, S.W.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, B.; Li, D. Evaluation of changes in the lipid profiles of dried shrimps (Penaeus vannamei) during accelerated storage based on chemical and lipidomics analysis. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 191, 115564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Shi, D.; Liu, C.J.; Huang, Y.L.; Wang, Q.L.; Wang, J.Y.; Pei, L.Y.; Lu, S.L. UPLC-MS-MS-based lipidomics for the evaluation of changes in lipids during dry-cured mutton ham processing. Food Chem. 2022, 377, 131977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.H.; Cao, S.Y.; Yang, L.; Li, Z.L. Flavor formation based on lipid in meat and meat products: A review. J. Food Biochem 2022, 46, e14439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.; Sun, Z.X.; Qu, X.C.; Cao, J.; Shen, X.R.; Li, C. A comprehensive study of lipid profiles of round scad (Decapterus maruadsi) based on lipidomic with UPLCQ-Exactive Orbitrap-MS. Food Res. Int. 2020, 133, 109138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.M.; Gang, K.Q.; Li, C.; Wang, J.H.; Liu, Y.X.; Zhou, D.Y.; Zhu, B.W. Change of lipids in whelks (Neptunea arthritica cumingi Crosse and Neverita didyma) during cold storage. Food Res. Int. 2020, 136, 109330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.S.; Zhang, H.W.; Song, Y.; Cong, P.X.; Li, Z.J.; Xu, J.; Xue, C.H. Comparative Lipid Profile Analysis of Four Fish Species by Ultraperformance Liquid Chromatography Coupled with Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 9423–9431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Liu, C.; RAO, W.X.; Chen, P.; Lei, K.K.; Mai, K.S.; Zhang, W.B. Dietary phospholipids improve growth performance and change the lipid composition and volatile flavor compound profiles in the muscle of abalone Haliotis discus hannai by affecting the glycerophospholipid metabolism. Aquac. Rep. 2023, 30, 101567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).