Abstract

Cassava fiber (CF) is a novel dietary fiber extracted from cassava by-products. To investigate its anti-obesity mechanism, obesity was induced in mice through a high-fat diet (HFD). Dietary supplementation with 10% CF significantly reduced body weight, body fat, triglycerides, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, total cholesterol, and fasting blood glucose in mice. CF effectively ameliorated hepatic steatosis and adipocyte hypertrophy, increased the villus height-to-crypt depth ratio, enhanced mucus secretion by intestinal goblet cells, down-regulated the expression of ileal lipid absorption-related genes (NPC1L1, CD36, and FABP2), and up-regulated the short-chain fatty acid receptor GPR43, collectively improving intestinal health. Compared to HFD mice, CF altered the gut microbiota: it increased beneficial Actinobacteria (including Bifidobacterium and Blautia) and decreased Proteobacteria (including Desulfovibrio) (p < 0.05). Functional analysis showed that the HFD mice microbiota was enriched in genes linked to disease (e.g., lipid metabolism disorders, cancer, antibiotic resistance), whereas CF-enriched microbiota had genes for energy, carbohydrate, and pyruvate metabolism. Compared to microcrystalline cellulose, CF and MCC both alleviated HFD-induced obesity. In summary, cassava fiber helped prevent obesity in mice by modulating gut microbes, strengthening the gut barrier, and improving host metabolic balance.

1. Introduction

Obesity is a global health concern. According to world health organization data, the prevalence of obesity among minors worldwide increased from 2% to 8%, and among adults from 7% to 16% between 1990 and 2022 [1]. Obesity elevates risks of mortality, cardiovascular diseases, metabolic dysfunction, and other comorbidities [2]. Established causative factors include imbalanced diet, physical inactivity, genetic predisposition, medication use, and endocrine disorders [3,4]. The underlying mechanism involves dysregulation of gut endocrine and neurohormonal signaling pathways, leading to increased appetite and energy storage [5]. Dietary modification and exercise remain primary preventive strategies, such as reducing intake of high-fat/high-sugar foods and increasing dietary fiber consumption. Both animal models and human studies have demonstrated the beneficial effects of dietary fiber on obesity and metabolic health [6,7].

Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz), cultivated broadly across tropical and subtropical zones, has an estimated worldwide production of about 303 million tons [8]. Processing one kilogram of fresh cassava roots into flour and starch yields approximately 0.65 kg of solid residue [9], primarily composed of starch and fiber [10]. The ratio of soluble dietary fiber (SDF) to insoluble dietary fiber (IDF) critically modulates intestinal nutrient absorption and microbiota composition. SDF forms a gel-like matrix in the gut, delaying nutrient transit [11], while being fermented by microbiota to generate short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which stimulate enteroendocrine L-cells to secrete glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and peptide YY (PYY). GLP-1 enhances insulin secretion, pancreatic β-cell proliferation, and hepatic glycogen synthesis, while promoting satiety [12]. PYY functions to reduce hunger and limit dietary intake [13]. Concurrently, the reticular structure of IDF adsorbs cholesterol, impedes lipid absorption, and augments satiety signals [14]. In our prior study, the extraction process optimization of SC9 (South China No. 9) cassava residue yielded cassava dietary fiber containing 22.92% SDF and 76.14% IDF [15]. This experiment aims to explore the preventive mechanism of the cassava fiber we obtained on high-fat diet-induced obesity in mice, providing a reference for efficient utilization of cassava by-products.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Cassava Fiber and Diets Formulation (Diet Composition)

In this study, cassava fiber was extracted from Manihot esculenta Crantz cv. CS9 (cultivated in Xishuangbanna, Yunnan Province, China) through a sequential process of washing, enzymatic hydrolysis, and acid treatment. (Extraction conditions: α-amylase concentration 0.8%, temperature 55 °C, pH 6.5, extraction time 3 h). Chemical reagents (Guangdong, Guanghua:) NaOH, sulfuric acid, hydrochloric acid, α-amylase (Novonesis, Denmark). The determination of cassava fiber follows the Determination of Dietary Fiber in Foods (China) [16]. Fiber composition: soluble dietary fiber (SDF) accounts for 22.92%, insoluble dietary fiber (IDF) accounts for 76.14%, and total dietary fiber (TDF) accounts for 99.06%. Four experimental diets were prepared based on Nutrient Requirements of Laboratory Animals [17], as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Ingredient composition and calculated nutrient levels of the mice diets (%, air-dried basis).

2.2. Animals Experiment

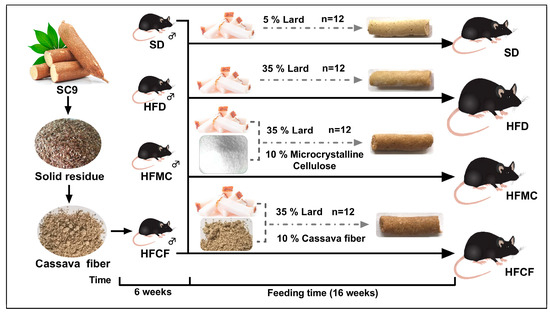

Forty-eight 6-week-old male C57BL/6J mice (22.25 ± 0.98) g were selected. They were randomly divided into four groups, with three cages per group and four mice per cage. The experimental design is illustrated in Figure 1. All mice were provided with food and water ad libitum and housed in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) facility at a constant temperature of 18–22 °C. The trial lasted 16 weeks. Weekly measurements of feed intake and body weight were recorded, and energy intake (kcal) was calculated based on the diet consumption and its energy density (kcal/g). At the conclusion of the study, after a 12 h fast, the mice were euthanized under ether anesthesia via cervical dislocation [18]. Subsequently, plasma, heart, liver, abdominal fat, subcutaneous fat, and intestinal segments were harvested following established protocols. Ileum tissue, cecal contents, and fecal samples were immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until microbial analysis. This study received ethical approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Southwest Forestry University, with all procedures conducted in accordance with the National Research Council Guide (The Care and Use of Laboratory Animals) [19].

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of experiment.

2.3. Biochemical and Histological Analysis

Plasma concentration of TG, CHO, HDL, LDL, TP, and GLU were detected by assay kits (Servicebio, GM1113/GM1117) and the automated biochemical analyzers (Leidu Chemray 240, Shenzhen, China). Plasma is clear; hemolysis is excluded. Each sample was measured in triplicate. For histological evaluation, liver, abdominal adipose tissue, and intestinal specimens were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (pH 7.4) for 24 h at 4 °C. After grade alcohol dehydration and xylene clearances, embedding in paraffin and sections in 5 um with a microtome (Leica RM2245, Wetzlar, Germany). The sections of liver and abdomen were used for hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining and the sections of intestine were used for AB/PAS staining. Microscopic images were captured at 200× and 400× magnifications (Nikon Eclipse E100, Shanghai, China). Image J (Version 1.53t, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda) was used to conduct quantitative analysis of tissue index.

2.4. Gene Expression Analysis of Intestinal Lipid-Metabolism Genes

Total RNA was isolated from ileum by TRIzol™ reagent (Servicebio technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China) and adjusted to a concentration of 200 ng/μL prior to reverse transcription. Gene expression levels by performing RT-PCR using CFX Connect Realtime PCR Platform (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The primers of intestinal adiponectin are detailed in Table 2. Each targeting gene expression was normalized to GAPDH, and the relative expression of each targeting gene compared to the SD group was calculated using the 2−△△CT method [20].

Table 2.

Primer sequence for Realtime qPCR.

2.5. Gut Microbiota Analysis via 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

Intestinal contents (Total Genome) DNA was extracted via CTAB method Evaluate DNA concentration and then adjust it to 1 ng/µL with the sterile water: The V3-V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified by universal primers: 314F (5′-CCTAYGGGRBGCASCAG-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′). The PCR reaction was performed in a mixture with a volume of 25 µL containing: 15 µL Phusion® High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix (NEB). A total of 2 µM of each primer, 10 ng template DNA. Thermocycling denaturing at the initial 98 °C for 2 min, 30 cycles were conducted at 98 °C for 20 s and 50 °C for 30 s and then 72 °C for 30 s and at the end, a 5 min final extension of 72 °C was performed. Amplicons were quantified with the Quant-iT™ PicoGreen™ dsDNA Assay Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) were pooled at equimolar concentrations. Amplicons were purified with the Qiagen Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

Sequence libraries were processed with the MiSeq® DNA PCR-free sample preparation kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Library quality was measured using the Qubit® 2.0 fluorescent meter (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system. In the end, libraries were sequenced on Illumina Novaseq platform with 250bp paired-end reads. Paired-end reads were merged using Flash [21], and raw tags were quality filtered—according to the QIIME v1.9.1 pipeline (Quality threshold is ≤19); tag length filtering: Filter out tags with base lengths shorter than 75% of the tag length. These clean tags were then analyzed again the Silva database through the UCHIME algorithm to identify and eliminate chimeras [22]. Effective tags sharing ≥97% sequence similarity were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) with Uparse v7.0.1001, and representative sequences from each OTU were taxonomically annotated at the phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species levels using the Silva database. Normalized data were subsequently employed to assess alpha and beta diversity, with principal component analysis (PCA) performed prior to cluster analysis to reduce dimensionality. Alpha diversity indices were calculated using QIIME (version 1.7.0), while principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was conducted to extract principal coordinates from the multidimensional data. All data analyses was performed through R software (Version 2.15.3).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Animals were randomly assigned to experimental groups and sampled accordingly. The IBM Corp. SPSS 21.0 software was used for analysis. The significance between groups was analyzed using a one-way ANOVA with Turkey’s Multiple Comparison. Data is represented as mean ± sem. The level p < 0.05 was considered as significant.

3. Results

3.1. Cassava Fiber Effectively Inhibited Weight Gain in Mice on a High-Fat Diet

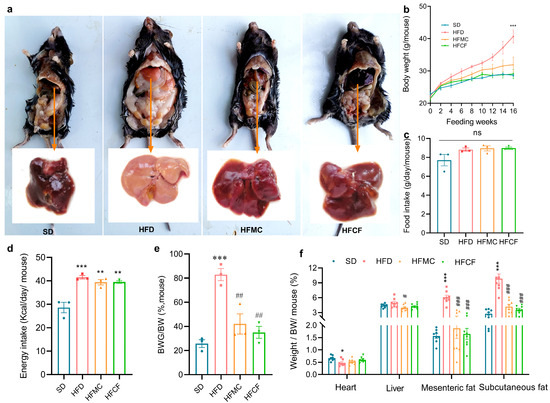

The high-fat diet formulated in this study successfully induced obesity in mice, as demonstrated in Figure 2a. Body weight of mice fed HFD was about 20% greater than SD. From weeks 1 to 16, the growth rate of HFD mice was significantly greater than that of the other three groups, whereas no significant difference was observed between the HFMC and SD groups (Figure 2b). Although food intake varied minimally among groups, energy intake was significantly higher in all three high-fat diet groups compared to the SD group (p < 0.01) (Figure 2c,d). The ratios of body weight gain to total body weight in mice fed microcrystalline cellulose and cassava fiber were significantly less than those in the HFD (p < 0.01) (Figure 2e). With regard to the assessment of the organs and adipose tissue, there were no significant changes in the heart index or the liver index between the groups (p > 0.05) (Figure 2f). However, HFD mice displayed characteristic hepatic pallor suggestive of lipid infiltration, whereas HFMC and HFCF groups maintained normal liver coloration comparable to SD controls (Figure 2a). Mesenteric and subcutaneous fat index in HFD was much higher than the other 3 groups (p < 0.01), but there was no difference among HFMC, HFCF, and SD (p > 0.05) (Figure 2f).

Figure 2.

Abdominal anatomical features and liver morphology, body weight, and dietary indicators of 22-week-old mice under different diets (SD: standard diet; HFD: high-fat diet; HFMC: high-fat diet with 10% microcrystalline cellulose; HFCF: high-fat diet of 10% cassava fiber; n = 12/group); (a) abdominal anatomical features and liver morphology; (b) body weight trajectory, measurements taken per mouse; (c) food intake, measured by cage; (d) energy intake (kcal/mouse/day), measured by cage; (e) body weight gain ratio (final weight—initial weight)/final weight), measured by cage; (f) organo index (organ weight / body weight × 100%), six mice were randomly selected from each cage as samples. Data represent mean ± SEM. * Statistical annotation: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 compared with the SD; # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001 compared with the HFD.

3.2. Cassava Fiber Improves Glycemic Level and Dyslipidemia Caused by High-Fat Diet

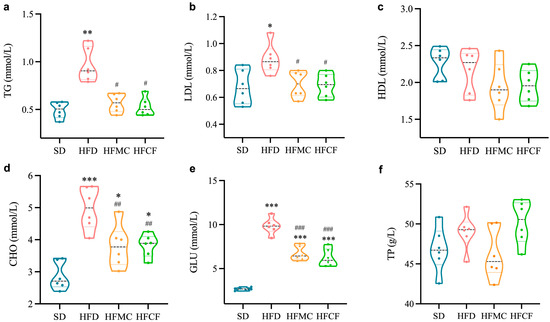

Biochemical markers of lipid metabolism are presented in Figure 3. Mice fed HFD had greatly higher levels of lipid TG and LDL than mice fed SD (p < 0.01), but the levels of lipid TG and LDL in HFMC and HFCF did not differ from the levels in SD mice (Figure 3a,b). All high-fat groups (HFD, HFMC, HFCF) displayed elevated blood cholesterol (CHO) and glucose (GLU) relative to SD mice (p < 0.01), with HFD mice showing maximal increases of 1.73-fold (CHO) and 3.68-fold (GLU) versus SD baseline (Figure 3d,e). Notably, supplementation with microcrystalline cellulose reduced CHO and GLU levels by 23% and 32% compared to the HFD. On the contrary, no considerable differences between the groups regarding HDL and TP can be seen (p > 0.05) (Figure 3c,f). So, these results show us that both microcrystalline cellulose and cassava fiber can effectively ameliorate the dyslipidemia and hyperglycemia induced by a high-energy diet in mice.

Figure 3.

Levels of biochemical indices of lipid levers in the serum of mice. n = 6/group. (a) Triglycerides (TG); (b) low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL); (c) high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL); (d) cholesterol (CHO); (e) glucose (GLU); (f) total protein (TP). Data represent mean ± SEM. * Statistical annotation: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 compared with the SD; # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001 compared with the HFD.

3.3. Cassava Fiber Attenuates Adipocyte Hypertrophy and Enhances Intestinal Mucosal Integrity

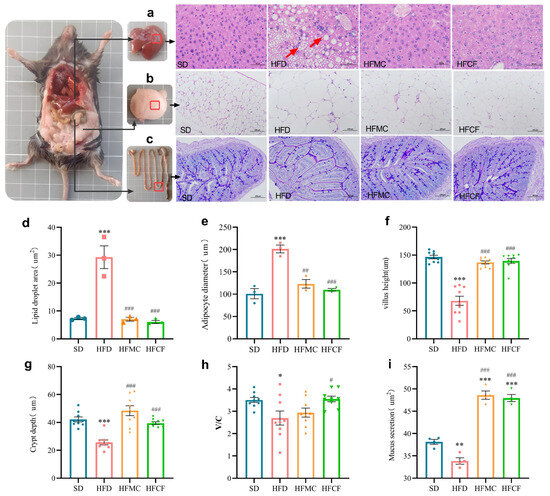

Anatomical assessments of liver and white adipose tissues are presented in Figure 4. Liver sections from HFD mice exhibited numerous vacuolar oil droplets—characteristic of fatty liver disease—accompanied by pronounced lymphocyte infiltration indicative of inflammation (Figure 4a). The hepatic lipid droplet area in HFD mice was much bigger than that in other groups (p < 0.01) (Figure 4d). Meanwhile, there was no difference among the HFMC, HFCF, and SD. In the mesenteric adipose tissue, the adipocytes from HFD mice had a much higher size than the rest of the groups (p < 0.01) (Figure 4b,e), with similar cell sizes observed in the HFMC, HFCF, and SD groups. Additionally, AB/PAS-stained ileal sections revealed that the villus height/crypt depth ratio (V/C) in HFCF mice was way higher than that of HFD mice (p < 0.01; Figure 4c,f–h). Concurrently, the secretion of both neutral and acidic mucus by the villi and basal epithelial cells was markedly reduced in HFD mice compared to the other groups (p < 0.01; Figure 4c,i), while similar mucus production was noted between the HFMC and HFCF groups. These findings suggest cassava fiber effectively suppresses HFD-driven adipocyte hypertrophy while promoting mucin-mediated intestinal mucosal barrier enhancement.

Figure 4.

Histopathological characteristics of liver and adipose tissue and their quantitative analysis. (a) H&E-stained liver sections (400×); (b) H&E-stained mesenteric adipose tissue (200×); (c) AB-PAS-stained ileal sections (200×); (d) hepatic lipid droplet area; (e) mesenteric adipocyte diameter; (f) ileal villus height; (g) ileal crypt depth; (h) villus height/crypt depth (V/C) ratio; (i) neutral and acidic mucus of ileal tissue. Histological measurements were performed on 3 sections per mouse group, with >100 adipocytes counted per field of view. Data represent mean ± SEM. * Statistical annotation: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 compared with the SD; # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001 compared with the HFD.

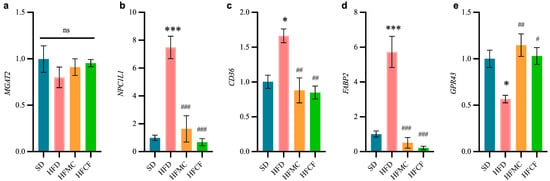

3.4. Cassava Fiber Affects the Expression of Genes Related to Intestinal Lipid Metabolism

The relative expression levels of ileal epithelial cells with lipid metabolism-related gene are presented in Figure 5. In contrast to SD mouse ileum, FFAR2 (GPR43) expression was notably downregulated by HFD (p < 0.05); and FABP2, CPC, and CD36 expression was significantly upregulated by HFD (p < 0.05). However, in mice supplemented with microcrystalline cellulose or cassava fiber, the expression levels of these genes did not differ from those in the SD group. In addition, there was no significant difference in the MGAT2 expression of all groups. And such kinds of discoveries indicate that cassava fiber probably does help regulate lipid metabolism through mitigating high-energy diet-induced alterations in intestinal gene expression.

Figure 5.

Relative transcript levels of ileal genes involved in lipid metabolism in ileum (2−ΔΔCt). n = 6/group. (a) Monoacylglycerol acyltransferase 2 (MGAT2). (b) Niemann-pick C1-like 1 (NPC1L1). (c) Fatty acid translocase (CD36/FAT). (d) Intestinal fatty acid-binding protein 2 (FABP2). (e) Free fatty acid receptor 2 (FFAR2/GPR43). Data represent mean ± SEM. * Statistical annotation: * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001 compared with the SD; # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001 compared with the HFD.

3.5. Cassava Fiber Modulates Gut Microbial Composition

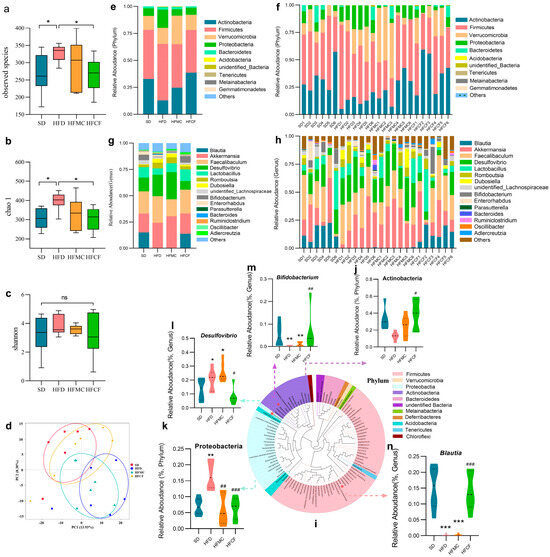

Cecal microbiota profiling via V3-V4 16S rRNA gene sequencing (Illumina NovaSeq platform) revealed distinct microbial community structures across dietary groups (97% similarity threshold for OTU clustering). Richness and evenness were calculated by alpha diversity analysis; at the OTU level the dispersion of alpha-diversity within the HFD mice was lower than other groups. The HFCF mice showed a similar amount as well as dispersion of species when compared to SD (Figure 6a). Chao 1 and shannon indices also showed the HFCF were similar to the SD in richness and evenness of diversity (Figure 6b,c). Furthermore, principal component analysis (PCA) revealed that the microbial community structure in HFD mice differed and segregated from SD (Figure 6d), while cluster analysis indicated that the cecal microbiota of HFCF mice closely resembled that of SD mice. The results indicated that high-fat diet-induced obesity, as well as the intervention with cassava fiber, significantly alters gut microbiome composition, which may be pivotal in regulating and preventing obesity.

Figure 6.

Alpha and beta diversity of the microbiota in the cecal contents and classification analysis of the microbiota. n = 6/group. Data represent mean ± SEM. * Statistical annotation: * p < 0.05. (a) Observed species between groups. (b) Alpha diversity chao1 index. (c) Alpha diversity shannoon index. (d) Principal component analysis between groups. (e,f) Phylum-level relative abundance. (g,h) Genus level relative abundance. (i) Phylogenetic tree of predominant genera. (j,k) Differential flora at phylum level. (l–n) Differential flora genus levels. Data represent mean ± SEM. * Statistical annotation: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 compared with the SD; # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001 compared with the HFD.

Different dietary group mice had different abundance of cecum microbiota. Despite differences in diet composition, their gut bacteria’s main taxa were Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, Verrucomicrobia, Proteobacteria, and Bacteroidetes. Phylum level (Figure 6e,f), the relative abundance of Actinobacteria was much less in HFD mice compared to HFCF mice (p < 0.05) (Figure 6j), whereas the relative abundance of Proteobacteria in HFD mice was much more than in HFMC and HFCF groups (p < 0.01) (Figure 6k). Correspondingly, at the genus level (Figure 6g,h), SCFA-specific Bifidobacterium (Actinobacteria) were significantly more abundant at the genus level in HFCF mice than in HFD mice (p < 0.01) (Figure 6 m) and HFMC mice, but pro-inflammatory Desulfovibrio (Pro-bacteria) were significantly more abundant in HFD mice than in HFMC mice (p < 0.05) (Figure 6l). Also, the relative amount of Blautia in HFD and HFCF mice was dramatically less when compared with HFCF mice (p < 0.001) (Figure 6n). Even if many of the microbial taxa did not show statistical significance in the phylum and genus abundance, the above differences in the flora with specific metabolic functions suggest that cassava fiber mediates anti-obesity effects through microbial metabolite reprogramming.

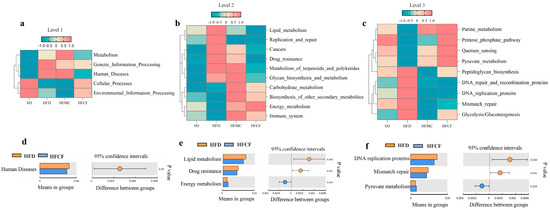

According to 16S rRNA gene-sequence information of the samples microbiota we annotated, gut microbiota functions by mapping homologous sequences to the KEGG database. Tax4Fun analysis revealed that, compared to SD and HFCF mice, the gut microbiota of HFD mice enriched KEGG homologs associated with human diseases at Level 1 (Figure 7a,d). Correspondingly, at level 2, we found genes involved with lipid metabolism, cancer, and drug resistance were enriched (Figure 7b,e). In contrast, at level 3, the gut microbiota of HFCF mice was significantly overrepresented in functional genes involved in energy metabolism, carbohydrate metabolism, and pyruvate metabolism (Figure 7c,f). It means different dietary plans might impact gut health differently since they alter the specific gene sets performing functions in the gut microbiome.

Figure 7.

Hierarchical functional profiling of gut microbiota via Tax4Fun prediction. n = 6/group. (a–c) KEGG ortholog distribution across functional hierarchies. (d–f) Differentially enriched pathways (a/d: level 1. b/e: level 2. c/f: level 3).

4. Discussion

Obesity is widely recognized as a global public health issue facing the human population. We usually refer to the imbalance between the caloric intake and energy utilization as the cause of obesity [23]. Obesity is closely associated with more than 50 diseases, including diabetes, high cholesterol, gallbladder disease, and metabolic dysfunction, and increases the risk of death [2]. In the diets of countries such as Eastern Europe, China, and France, lard is often used in cooking to enhance the flavor of food. These animal fats are high in saturated fatty acids (SFAs), and eating too much of these kinds of fats for long periods of time is related to weight gain and heart problems [24]. Our research proved that feeding 35% lard to adult mice led to obesity, and this obesity was shown through an increase in the mice’s weight, an increase in belly and subcutaneous fat, and through pathological manifestations of cardiovascular disease and fatty liver, with total triglyceride, LDL (low density lipoprotein), cholesterol, and glucose levels all at elevated levels, with many fat vacuoles and lymphocytes present in liver cells. The direct reason is that dietary saturated fatty acids are transported into intestinal epithelial cells for further processing and packaging to form chylomicrons, which are transferred to metabolic tissues through the lymphatic and circulatory systems [25], resulting in obesity.

Nutritional approaches to preventing obesity include adjusting dietary patterns and increasing dietary fiber intake. There are many studies which have shown that dietary fiber can prevent obesity by regulating intestinal digestion and absorption, microflora composition, enzyme activity, short-chain fatty acids, and other related receptor (GPCRs, Y2), promoting hormone secretion (PYY, GLP-1, NF-κB) and regulating appetite, metabolism, and immunity through the brain-intestinal axis [26,27,28]. And, through our study, we found that MCC and cassava fiber also help with obesity and reduce the TG, LDL, CHO, and GLU in the blood of mice ingesting a high-fat diet. MCC is a purified polysaccharide derived from natural plant cellulose polymerized with β-1, 4-glucoside bond. It is used as food raw material and dietary fiber in the food industry. MCC has been proven to absorb lipids to reduce blood lipids, affect the expression of enzymes in lipid metabolism, and have a positive effect on gastrointestinal physiology [29]. The cassava fiber in this study was extracted from South China No. 9 (SC9), a high yield and low cyanoside variety widely cultivated in Yunnan Province, China. The proportions of soluble and insoluble fibers in cassava fiber were 22.92% and 76.14%, respectively. The gel-like substance formed by soluble fiber in the gastrointestinal tract can affect digestion and absorption of the contents [30]. Insoluble fiber could increase fecal bulk and decrease transit time [31]. The study by Lin et al. also pointed out that people with higher fiber intake and those with a higher proportion of increased soluble fiber had lower BMIs [32]. A few reviews and an analyses of the studies that have been conducted have identified that fiber intake can give a measure of protection from cardiovascular illness [33] and type 2 diabetes [34]. First, the fiber-rich cell wall acts as a barrier stopping food from being digested and so uses less energy and CHO [35]. Second, soluble fiber increases the viscosity of chyme, which impedes the α-activity of amylase and the diffusion of glucose through the epithelium cell [36]. Indeed, from the indices of view of anti-obesity indicators, the effect of cassava fiber is also better than MCC.

In addition to fiber being able to dilute energy and shorten transport time, the resistance to obesity it provides is also reflected in the structure and function of the intestine [37]. Changes in the height of intestinal villi and the depth of intestinal recess can directly affect the surface area of intestinal contact with food and determine the absorption and digestion of nutrients [38]. It is pointed out in this study that the MCC and cassava fiber can promote an increase in villus height and V/C value in the ileum through the dietary fiber fermentation process, the production of SCFAs in the intestine, the supply of energy to the intestinal epidermis cell, and the promotion of the proliferation of crypt cells and goblet cells to increase the villi height [39]. Furthermore, MCC and cassava fiber can promote the differentiation of goblet cells and effectively alleviate the obstruction of intestinal epithelial mucus secretion caused by the high-fat diet. Other studies [40] also suggest that the mucus layer is structurally dependent on Mucus—2 recombinant protein (MUC2) synthesized by goblet cells, and absence of fiber results in a thinned mucus layer and damages our intestinal health.

Lipid-associated transporters in intestinal epithelial cells are key to fat absorption. The Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 gene (NPC1L1) controls the expression of a membrane protein on the brush membrane of the small intestine epithelium [41], a target for intestinal cholesterol absorption. NPC1L1 transports cholesterol to the endoplasmic reticulum in the intestinal cells, which is esterified into cholesterol ester (CE) by cholesterol esterification enzyme (ACAT2), and then forms chylomicrons that are transported to the blood circulation [42]. Polymorphism of the NPC1L1 gene are related to plasma total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels. FABP2 (intestinal FABP) is one of the intracellular protein families highly expressed in intestinal villi epithelial cells, and it binds strongly with long-chain fatty acids (LCFA) [43]. FABP2 is a major regulatory of lipid metabolism within cells and tissue. FABP2 transports fatty acids into intestinal epithelial cells to synthesize triglycerides [44], and its over expression will increase the transport of fatty acids and cause diseases such as dyslipidemia and obesity [45]. Gajda et al. [46] confirmed that FABP2 knockout mice lost weight after a high-fat diet, considering that FABP2 is associated with lipid uptake in the small intestine. In addition, FABP2 collaborates with the fat transporter (CD36) to promote the transmembrane absorption of long-chain fatty acids [47] and the production of chylomicron [48]; free fatty acids cause post translation variations in these transporters [49]. And highly expressing all three of these kinds of transmembrane protein genes can enable intestinal epithelial cells to absorb and transform a large number of lipids. Similarly to our results, the gene expressions of NPC1L1, FABP2, and CD36 transmembrane proteins in the ileal epithelial cells of HFD mice are significantly higher than those of the control mice, and dietary fiber can effectively reduce the expression of these lipid transport genes. The results were also confirmed by TG, LDL, and CHO in the blood of the mice.

In contrast, HFD reduced FFAR2 (GPR43) gene expression in mouse ileal epithelial cell membranes. GPR43, GLP-1, and PYY are all co expressed and have similar roles by way of regulation of appetite and insulin action in L Intestional cells to control energy homeostasis [50,51,52]. Among them, the PYY is released by the intestinal epithelial cells in response to the presence of lipids in the intestinal lumen and it controls the production of FABP2 by the L-cells [53]. GPR43, PYY, and GLP-1 on intestinal epithelial cell membrane can be activated by SCFAs [54,55], and FFARs have been reported to have physiological functions such as facilitation of insulin and incretin hormone secretion [56]. Ge et al. [57] showed that intraperitoneal injection of sodium acetate in mice could activate GPR43 and rapidly reduce the level of plasma FA in vivo. Similarly, in our study, dietary fiber under a high-fat diet may also regulate these lipid transporters through intestinal microbial fermentation to produce SCFAs, which regulates the absorption of fat and energy by intestinal epithelial cells. This positive regulatory effect is also reflected in the blood indices of mice.

The changes in the composition of gut microbiota caused by diet are closely associated with metabolic disorders and obesity [58,59]. The core microbiota in the animal intestine mainly consists of Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Verrucomicrobia, Proteobacteria, and bacteroidetes [60]. In our study, the significant enrichment of Blautia within the phylum Firmicutes in the intestines of HFCF mice, compared to HFD and HFMC mice deprived of insoluble fiber, drew our attention. Among mammals, Blautia is a potential probiotic with obesity-regulating effects, following Akkermansia [61]. In obesity research in mice and humans, Blautia shows a negative correlation with several biomarkers related to obesity and metabolic disorders in multiple studies [62,63,64]. In addition, eating orally Blautia wexlerae has been shown to prevent obesity and diabetes induced by a high-fat diet in mice [65]. Adding corn fiber to a high-fat diet can increase the abundance of Blautia in mouse feces and improve obesity [66]. Enrichment of Blautia was also observed in the feces of rats when fiber was added to a high-cholesterol diet [67]. In our study, the inhibitory effects of cassava fiber on obesity and hyperlipidemia may also be associated with the enrichment of Blautia. In contrast, microcrystalline cellulose had minimal effects. Parmar et al. [68] found that Blautia isolated from the rumen showed prominent metabolic capabilities for insoluble fibers. This may suggest that the fermentation substrates of Blautia are specific. The regulation of intestinal microorganisms to host is mainly mediated by metabolites. The main metabolic product of Blautia in the intestine is acetate [69], which, by activating the GPR41 and GPR43, inhibits insulin signaling and fat accumulation in adipocytes, thereby promoting lipid and glucose metabolism and alleviating obesity [70]. Similarly to our results, the high expression of the GPR43 gene in the intestinal epithelium of HFD-fiber mice may also be contributed by the high abundance of Blautia. Some in vitro experiments have also confirmed that Blautia can prevent obesity by esterifying hydroxylated long-chain fatty acids [71] and metabolizing tryptophan to produce indole-3-acetic acid (I3AA) [62]. I3AA restrained liver lipogenesis via negatively controlling the expression of the FAS and SREBP-1c, which encoded fatty acid synthetases and SREBP-1c, respectively [72]. These studies on Blautia will provide valuable information for future microbiome-based strategies for the early prevention of obesity and its complications.

In addition, the differences in the gut microbiota of mice induced by cassava fiber intervention were also reflected in the following: fiber deprivation (HFD) led to a decrease in the abundance of Bifidobacterium within the phylum Actinobacteria and an increase in the abundance of Desulfovibrio within the phylum Proteobacteria. Similarly, in the gut Microbiota of 66 obese and diabetic patients, a low abundance of Bifidobacteria (Actinobacteria) and a high abundance of Proteobacteria were observed [60]. Fiber diet intervention can increase the abundance of Bifidobacterium adolescentis and protect male mice from diet-caused obesity [73]. Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum’s newly found evidence, its strains have an endo-1, 4-β-xylanase which is a gene to metabolize plant-based long-chain xylan (a form of insoluble diet fiber) [74], producing short-chain fatty acids (lactate, acetate) associated with host health [75]. At the same time, Tax4Fun showed that the gut microbiota of cassava fiber mice enriched genetic information related to energy metabolism (Level 2) and pyruvate metabolism (Level 3), which corresponded to the enrichment of Bifidobacterium. Because Bifidobacterium contains an important metabolic gene-pyruvate-kinase in its 16S rRNA [76], it can convert pyruvate into lactic acid under anaerobic conditions [77]. In addition, Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum promotes the biosynthesis of secondary bile acids by producing bile salt hydrolase [78], whereas Bifidobacterium pseudolongum produces more of acetate which in turn can block IL-6/JAK1/STAT3 pathway using GPR43 [79], both of which reduce excessive fat deposition in the body. These diet-induced differences in gut microbiota, despite the specificity between strains. But overall, intervention with dietary fiber and its associated floras could be a way to tackle metabolic conditions such as obesity and diabetes.

Tax4Fun functional prediction can quickly predict the potential metabolic pathways and functions of a microbial community by mapping to the KEGG functional database, without the need for complete genome data. It is worth noting that, compared to cassava fiber mice, Tax4Fun showed that HFD mice enriched genetic information related to human diseases (Figure 7a,d), lipid metabolism, and drug resistance (Figure 7b,e), which corresponded to the enrichment of the Desulfovibrio. There is more energy which leads to there being more Desulfovibrio, which damages the host. Lots of studies previously identified that Desulfovibrio in gut microbiota contributes to obesity and diabetes [80,81]. The Desulfovibrio-derived H2S, richly found in the gut microbiota of metabolic syndrome, can inhibit mitochondrial respiration and suppress the secretion and gene expression of GLP-1 in the intestinal L-cells of mice [82]. This metabolic disruption through the gut-brain axis leads to obesity and impaired glucose tolerance [83]. Additionally, Desulfovibrio can desulfate mucin, thereby facilitating Prevotella in degrading intestinal mucin and disrupting the mucus barrier [84]. In our study, HFD mice with enriched desulfation showed reduced mucin secretion in the intestinal epithelial AB/PAS staining. These results are associated with the abundance of Desulfovibrio. Of course, such results reflect trends rather than actual gene expression levels. We need to validate these findings in subsequent studies by integrating metagenomic or transcriptomic data.

5. Conclusions

Our study successfully established a high-fat mouse model with a formulated high-fat diet, which exhibited marked obesity and related lesions. Under a high-fat diet, both cassava fiber and MCC effectively prevent obesity, maintain homeostasis in fat, liver, and intestinal epithelial cells, and regulate serum glucose and lipid levels. Furthermore, cassava fiber may alter Bifidobacterium, Blautia, and Desulfovibrio abundance in the intestine, affecting gut barrier integrity and host metabolic processes, resulting in an anti-obesogenic effect. Of course, in future research it is necessary to carry out metagenomic and metabolomic detection of SCFAs to further verify the mechanism of preventing obesity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Y., A.G. and Z.Z.; methodology, Y.Y. and F.L.; software, L.L.; formal analysis, Y.Y. and F.L.; investigation, Y.C.; resources, Z.Z. and J.L.; data curation, Y.Y. and F.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y.; writing—review and editing, A.G.; visualization, Y.Y. and Y.C.; supervision, Q.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 31860650 and the Yunnan Provincial Agricultural Basic Research Joint Special Project—Key Project, grant number 202401BD070001-024, and the National Cassava Industry Technology System Xishuangbanna Comprehensive Experimental Station Project, grant number CARS-11-YNLHQ.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the ethical approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Southwest Forestry University (Resolution No: SWFU-20240512).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Obesity and Overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/obesity/ (accessed on 31 August 2024).

- Campbell, L.A.; Kombathula, R.; Jackson, C.D. Obesity in adults. JAMA 2024, 332, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazdi, F.T.; Clee, S.M.; Meyre, D. Obesity genetics in mouse and human: Back and forth, and back again. PeerJ 2015, 3, e856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleich, S.; Cutler, D.; Murray, C.; Adams, A. Why is the developed world obese? Annu. Rev. Public Health 2008, 29, 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deehan, E.C.; Mocanu, V.; Madsen, K.L. Effects of dietary fibre on metabolic health and obesity. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 21, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.K.; Rossi, M.; Bajka, B.; Whelan, K. Dietary fibre in gastrointestinal health and disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mah, E.; Liska, D.J.; Goltz, S.; Chu, Y. The effect of extracted and isolated fibers on appetite and energy intake: A comprehensive review of human intervention studies. Appetite 2023, 180, 106340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwibuka, Y.; Nyirakanani, C.; Bizimana, J.P.; Bisimwa, E.; Brostaux, Y.; Lassois, L.; Vanderschuren, H.; Massart, S. Risk factors associated with cassava brown streak disease dissemination through seed pathways in Eastern D.R. Congo. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 803980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Schmidt, V.K.; de Vasconscelos, G.M.D.; Vicente, R.; Teixeira, J.A. Cassava wastewater valorization for the production of biosurfactants: Surfactin, rhamnolipids, and mannosileritritol lipids. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 39, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinya, T.Y.; Elsner, V.H.P.; de Lima, D.S., Jr.; Ranke, F.F.D.; Escaramboni, B.; Melo, W.G.D.; Núñez, E.G.F.; Neto, P.D. Bioprocess development with special yeasts for cassava bagasse enrichment nutritional to use in animal feed. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2022, 290, 115338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuhiro, B.; Lillo, L.E.; Sáenz, C.; Urzúa, C.C.; Zárate, O. Chemical characterization of the mucilage from fruits of Opuntia ficus indica. Carbohydr. Polym. 2006, 63, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isken, F.; Klaus, S.; Osterhoff, M.; Pfeiffer, A.F.H.; Weickert, M.O. Effects of long-term soluble vs. insoluble dietary fiber intake on high-fat diet-induced obesity in C57BL/6J mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2010, 21, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Cui, X.; Guo, M.; Tian, Y.; Xu, W.; Huang, K.; Zhang, Y. Insoluble dietary fiber from pear pomace can prevent high-fat diet-induced obesity in rats mainly by improving the structure of the gut microbiota. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 27, 856–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, B.; Lin, L.; Chen, B.; Zheng, Y.; Xiao, J. Hydration properties and binding capacities of dietary fibers from bamboo shoot shell and its hypolipidemic effects in mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 109, 1003–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Lei, F.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, L.; Li, Q.; Guo, A. Effects of cassava root meal on the growth performance, apparent nutrient digestibility, organ and intestinal indices, and slaughter performance of yellow-feathered broiler chickens. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2024, 56, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GB/T 5009.88-2008; Determination of Dietary Fiber in Foods. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China (SAC): Beijing, China, 2008; pp. 1–15.

- National Research Council. Nutrient Requirements of Laboratory Animals, 4th ed.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; pp. 1–176. [Google Scholar]

- Arras, M.; Rettich, A.; Seifert, B.; Käsermann, H.P.; Rülicke, T. Should laboratory mice be anaesthetized for tail biopsy? Lab. Anim. 2007, 41, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th ed.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magoč, T.; Salzberg, S.L. FLASH: Fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2957–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, B.J.; Gevers, D.; Earl, A.M.; Feldgarden, M.; Ward, D.V.; Giannoukos, G.; Ciulla, D.; Tabbaa, D.; Highlander, S.K.; Sodergren, E.; et al. Chimeric 16S rRNA sequence formation and detection in Sanger and 454-pyrosequenced PCR amplicons. Genome Res. 2011, 21, 494–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, B.C.; Lim, A.L.; Chan, S.; Yum, M.P.; Koh, N.S.; Finkelstein, E.A. The impact of obesity: A narrative review. Singapore Med. J. 2023, 163, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Gan, L.; Graubard, B.I.; Männistö, S.; Fang, F.; Weinstein, S.J.; Liao, L.M.; Sinha, R.; Chen, X.; Albanes, D.; et al. Plant and animal fat intake and overall and cardiovascular disease mortality. JAMA Intern. Med. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mah, S.M.; Cao, E.; Anderson, D.; Escott, A.; Tegegne, S.; Gracia, G.; Schmitz, J.; Brodesser, S.; Zaph, C.; Creek, D.J.; et al. High-fat feeding drives the intestinal production and assembly of C16:0 ceramides in chylomicrons. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadp2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddell, I.S.; Orfila, C. Dietary fiber in the prevention of obesity and obesity-related chronic diseases: From epidemiological evidence to potential molecular mechanisms. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 63, 8752–8767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, G.B.; Heaton, K.W.; Murphy, D.; Burroughs, L.F. Depletion and disruption of dietary fibre: Effects on satiety, plasma-glucose, and serum-insulin. Lancet 1977, 310, 679–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miquel-Kergoat, S.; Azais-Braesco, V.; Burton-Freeman, B.; Hetherington, M.M. Effects of chewing on appetite, food intake and gut hormones: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiol. Behav. 2015, 151, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsor-Atindana, J.; Chen, M.; Goff, H.D.; Zhong, F.; Sharif, H.R.; Li, Y. Functionality and nutritional aspects of microcrystalline cellulose in food. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 172, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron-Smith, D.; Collier, G.R.; O’Dea, K. Effect of soluble dietary fibre on the viscosity of gastrointestinal contents and the acute glycaemic response in the rat. Br. J. Nutr. 1994, 71, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberfroid, M. Dietary fiber, inulin, and oligofructose: A review comparing their physiological effects. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1993, 33, 103–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Huybrechts, I.; Vandevijvere, S.; Bolca, S.; De Keyzer, W.; De Vriese, S.; Polet, A.; De Neve, M.; Van Oyen, H.; Van Camp, J.; et al. Fibre intake among the Belgian population and its association with BMI and waist circumference. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 105, 1692–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Threapleton, D.E.; Greenwood, D.C.; Evans, C.E.; Cleghorn, C.L.; Nykjaer, C.; Woodhead, C.; Cade, J.E.; Gale, C.P.; Burley, V.J. Dietary fibre intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2013, 347, f6879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrli, F.; Taneri, P.E.; Bano, A.; Bally, L.; Blekkenhorst, L.C.; Bussler, W.; Metzger, B.; Minder, B.; Glisic, M.; Muka, T.; et al. Oat intake and risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, C.; Ryden, P.; Edwards, C.H.; Grundy, M.M. Plant cell walls: Impact on nutrient bioaccessibility and digestibility. Foods 2020, 9, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, K.; Ke, M.Y.; Li, W.H.; Zhang, S.Q.; Fang, X.C. The impact of soluble dietary fibre on gastric emptying, postprandial blood glucose and insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 23, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.K.; Kim, W.K. Effects of dietary fiber on nutrients utilization and gut health of poultry: A review of challenges and opportunities. Animals 2021, 11, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva, B.P.; Martino, H.S.D.; Tako, E. Plant origin prebiotics affect duodenal brush border membrane functionality and morphology in vivo (Gallus gallus). Food Funct. 2021, 12, 6157–6166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piekarska, J.; Miśta, D.; Houszka, M.; Króliczewska, B.; Zawadzki, W.; Gorczykowski, M. Trichinella spiralis: The influence of short chain fatty acids on the proliferation of lymphocytes, the goblet cell count and apoptosis in the mouse intestine. Exp. Parasitol 2011, 128, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyström, E.E.L.; Martinez-Abad, B.; Arike, L.; Birchenough, G.M.H.; Nonnecke, E.B.; Castillo, P.A.; Svensson, F.; Bevins, C.L.; Hansson, G.C.; Johansson, M.E.V. An intercrypt subpopulation of goblet cells is essential for colonic mucus barrier function. Science 2021, 372, eabg1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Yang, F.; Huang, Y.; You, X.; Liu, D.; Sun, S.; Sui, S.F. Structural insights into the mechanism of human NPC1L1-mediated cholesterol uptake. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabg3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Dong, L.W.; Liu, S.; Meng, F.H.; Xie, C.; Lu, X.Y.; Zhang, W.J.; Luo, J.; Song, B.L. Bile acids-mediated intracellular cholesterol transport promotes intestinal cholesterol absorption and NPC1L1 recycling. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storch, J.; Thumser, A.E. Tissue-specific functions in the fatty acid-binding protein family. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 32679–32683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuhashi, M.; Hotamisligil, G.S. Fatty acid-binding proteins: Role in metabolic diseases and potential as drug targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 489–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotamisligil, G.S.; Bernlohr, D.A. Metabolic functions of FABPs–mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2015, 11, 592–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajda, A.M.; Zhou, Y.X.; Agellon, L.B.; Fried, S.K.; Kodukula, S.; Fortson, W.; Patel, K.; Storch, J. Direct comparison of mice null for liver or intestinal fatty acid-binding proteins reveals highly divergent phenotypic responses to high fat feeding. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 30330–30344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glatz, J.F.C.; Luiken, J.J.F.P. Dynamic role of the transmembrane glycoprotein CD36 (SR-B2) in cellular fatty acid uptake and utilization. J. Lipid Res. 2018, 59, 1084–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.W.; Wang, J.; Guo, H.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Sun, H.H.; Li, Y.F.; Lai, X.Y.; Zhao, N.; Wang, X.; Xie, C.; et al. CD36 facilitates fatty acid uptake by dynamic palmitoylation-regulated endocytosis. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupert, J.E.; Kolonin, M.G. Fatty acid translocase: A culprit of lipid metabolism dysfunction in disease. Immunometabolism 2022, 4, e00001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaki, S.; Mitsui, R.; Hayashi, H.; Kato, I.; Sugiya, H.; Iwanaga, T.; Furness, J.B.; Kuwahara, A. Short-chain fatty acid receptor, GPR43, is expressed by enteroendocrine cells and mucosal mast cells in rat intestine. Cell Tissue Res. 2006, 324, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolhurst, G.; Heffron, H.; Lam, Y.S.; Parker, H.E.; Habib, A.M.; Diakogiannaki, E.; Cameron, J.; Grosse, J.; Reimann, F.; Gribble, F.M. Short-chain fatty acids stimulate glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion via the G-protein-coupled receptor FFAR2. Diabetes 2012, 61, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolognini, D.; Barki, N.; Butcher, A.J.; Hudson, B.D.; Sergeev, E.; Molloy, C.; Hodge, D.; Bradley, S.J.; Le Gouill, C.; Bouvier, M.; et al. Chemogenetics defines receptor-mediated functions of short chain free fatty acids. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2019, 15, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halldén, G.; Aponte, G.W. Evidence for a role of the gut hormone PYY in the regulation of intestinal fatty acid-binding protein transcripts in differentiated subpopulations of intestinal epithelial cell hybrids. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 12591–12600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.J.; Goldsworthy, S.M.; Barnes, A.A.; Eilert, M.M.; Tcheang, L.; Daniels, D.; Muir, A.I.; Wigglesworth, M.J.; Kinghorn, I.; Fraser, N.J.; et al. The orphan G protein-coupled receptors GPR41 and GPR43 are activated by propionate and other short chain carboxylic acids. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 11312–11319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, E.S.; Morrison, D.J.; Frost, G. Control of appetite and energy intake by SCFA: What are the potential underlying mechanisms? Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2015, 74, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, J.; Hasegawa, S.; Kasubuchi, M.; Ichimura, A.; Nakajima, A.; Kimura, I. Nutritional signaling via free fatty acid receptors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Li, X.; Weiszmann, J.; Wang, P.; Baribault, H.; Chen, J.L.; Tian, H.; Li, Y. Activation of G protein-coupled receptor 43 in adipocytes leads to inhibition of lipolysis and suppression of plasma free fatty acids. Endocrinology 2008, 149, 4519–4526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, T.; Bäckhed, F. Effects of the gut microbiota on obesity and glucose homeostasis. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 22, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.T.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Bäckhed, F. Microbial modulation of insulin sensitivity. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sroka-Oleksiak, A.; Młodzińska, A.; Bulanda, M.; Salamon, D.; Major, P.; Stanek, M.; Gosiewski, T. Metagenomic analysis of duodenal microbiota reveals a potential biomarker of dysbiosis in the course of obesity and type 2 diabetes: A pilot study. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Mao, B.; Gu, J.; Wu, J.; Cui, S.; Wang, G.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W. Blautia-a new functional genus with potential probiotic properties? Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1875796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Hu, X.; Song, Y.; Wang, C.; Luo, P.; Ni, S.; Jiao, F.; Qiu, J.; Jiang, W.; Yang, S.; et al. Blautia coccoides is a newly identified bacterium increased by leucine deprivation and has a novel function in improving metabolic disorders. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2309255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozato, N.; Yamaguchi, T.; Mori, K.; Katashima, M.; Kumagai, M.; Murashita, K.; Katsuragi, Y.; Tamada, Y.; Kakuta, M.; Imoto, S.; et al. Two Blautia species associated with visceral fat accumulation: A one-year longitudinal study. Biology 2022, 11, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozato, N.; Saito, S.; Yamaguchi, T.; Katashima, M.; Tokuda, I.; Sawada, K.; Katsuragi, Y.; Kakuta, M.; Imoto, S.; Ihara, K.; et al. Blautia genus associated with visceral fat accumulation in adults 20–76 years of age. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2019, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosomi, K.; Saito, M.; Park, J.; Murakami, H.; Shibata, N.; Ando, M.; Nagatake, T.; Konishi, K.; Ohno, H.; Tanisawa, K.; et al. Oral administration of Blautia wexlerae ameliorates obesity and type 2 diabetes via metabolic remodeling of the gut microbiota. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Bindels, L.B.; Segura Muñoz, R.R.; Martinez, I.; Walter, J.; Ramer-Tait, A.E.; Rose, D.J. Disparate metabolic responses in mice fed a high-fat diet supplemented with maize-derived non-digestible feruloylated oligo- and polysaccharides are linked to changes in the gut microbiota. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Han, H.W.; Yim, S.Y. Beneficial effects of soy milk and fiber on high cholesterol diet-induced alteration of gut microbiota and inflammatory gene expression in rats. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, N.R.; Nirmal Kumar, J.I.; Joshi, C.G. Deep insights into carbohydrate metabolism in the rumen of Mehsani buffalo at different diet treatments. Genom. Data 2015, 6, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, R.; Onuki, M.; Hattori, K.; Ito, M.; Yamada, T.; Kamikado, K.; Kim, Y.G.; Nakamoto, N.; Kimura, I.; Clarke, J.M.; et al. Commensal microbe-derived acetate suppresses NAFLD/NASH development via hepatic FFAR2 signalling in mice. Microbiome 2021, 9, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, I.; Ozawa, K.; Inoue, D.; Tsujimoto, G. The gut microbiota suppresses insulin-mediated fat accumulation via the short-chain fatty acid receptor GPR43. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folz, J.; Culver, R.N.; Morales, J.M.; Grembi, J.; Triadafilopoulos, G.; Relman, D.A.; Huang, K.C.; Shalon, D.; Fiehn, O. Human metabolome variation along the upper intestinal tract. Nat. Metab. 2023, 5, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, S.; Ding, Y.; Saedi, N.; Choi, M.; Sridharan, G.V.; Sherr, D.H.; Yarmush, M.L.; Alaniz, R.C.; Jayaraman, A.; Lee, K. Gut microbiota-derived tryptophan metabolites modulate inflammatory response in hepatocytes and macrophages. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 1099–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Wu, Q.; Qian, L.; He, J.; Ni, Y.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Yuan, R.; Liu, S.; et al. Resistant starch intake facilitates weight loss in humans by reshaping the gut microbiota. Nat. Metab. 2024, 6, 578–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y.; Saito, Y.; Hara, T.; Tsukuda, N.; Aiyama-Suzuki, Y.; Tanigawa-Yahagi, K.; Kurakawa, T.; Moriyama-Ohara, K.; Matsumoto, S.; Matsuki, T. Xylan utilisation promotes adaptation of Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum to the human gastrointestinal tract. ISME Commun. 2021, 1, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira, F.M.; Photenhauer, A.L.; Pollet, R.M.; Brown, H.A.; Koropatkin, N.M. Starch digestion by gut bacteria: Crowdsourcing for carbs. Trends Microbiol. 2020, 28, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaugien, L.; Prevots, F.; Roques, C. Bifidobacteria identification based on 16S rRNA and pyruvate kinase partial gene sequence analysis. Anaerobe 2002, 8, 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degnan, B.A.; Macfarlane, G.T. Effect of dilution rate and carbon availability on Bifidobacterium breve fermentation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1994, 40, 800–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, A.; Qi, M.; Deng, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, N.; Wang, C.; Liao, S.; Wan, D.; Xiong, X.; Liao, P.; et al. Gut Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum protects against fat deposition by enhancing secondary bile acid biosynthesis. iMeta 2024, 3, e261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Zhang, X.; Liu, W.; Wei, H.; Liang, W.; Zhou, Y.; Ding, Y.; Ji, F.; Ho-Kwan Cheung, A.; Wong, N.; et al. Bifidobacterium pseudolongum-generated acetate suppresses non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 1352–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Meng, F.; Wang, J.; Wei, J.; Zhang, K.; Qin, S.; Li, M.; Wang, F.; Wang, B.; Liu, T.; et al. Desulfovibrio vulgaris flagellin exacerbates colorectal cancer through activating LRRC19/TRAF6/TAK1 pathway. Gut. Microbes 2025, 17, 2446376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doumatey, A.P.; Adeyemo, A.; Zhou, J.; Lei, L.; Adebamowo, S.N.; Adebamowo, C.; Rotimi, C.N. Gut microbiome profiles are associated with type 2 diabetes in urban Africans. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q.; Zhang, H.; Jin, Z.; Wang, C.; Xia, M.; Chen, B.; Lv, B.; Peres Diaz, L.; Li, X.; Feng, R.; et al. Hydrogen sulfide produced by the gut microbiota impairs host metabolism via reducing GLP-1 levels in male mice. Nat. Metab. 2024, 6, 1601–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carty, S. Microbial hydrogen sulfide hampers L-cell GLP-1 production. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2024, 20, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, D.P.; Rosendale, D.I.; Roberton, A.M. Prevotella enzymes involved in mucin oligosaccharide degradation and evidence for a small operon of genes expressed during growth on mucin. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2000, 190, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).