Comprehensive IAC Cross-Reactivity Validation and Stabilized Method Development for Ochratoxin A, B, and C in Complex Coffee and Spice Matrices

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Instrumental

2.3. Coffee and Spice Samples

2.4. Optimization Parameters for Ochratoxin Extraction and Clean-Up

2.4.1. Optimization of Extraction

2.4.2. Optimization of IAC Clean-Up

2.5. Sample Pretreatment

2.6. Matrix Effect Evaluation of LC-MS/MS

2.7. Method Validation and Comparison

3. Results and Discussion

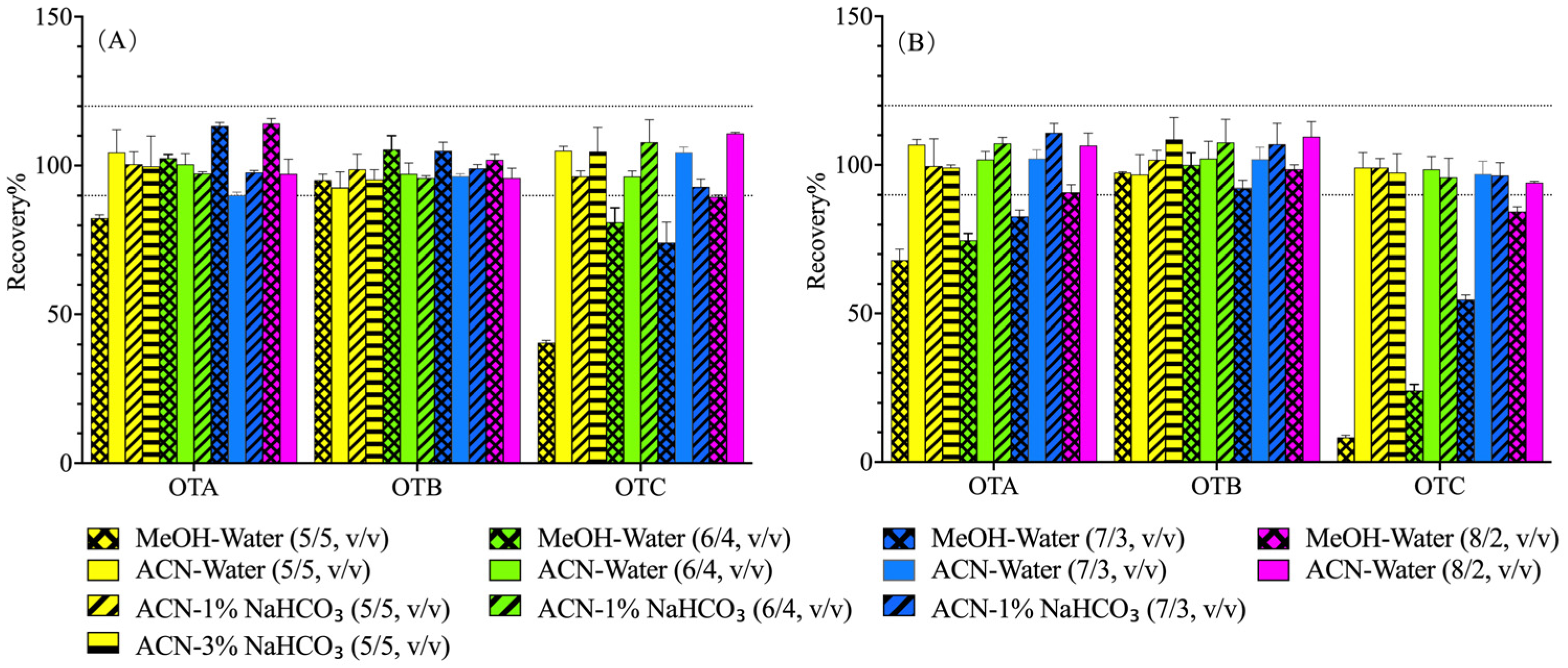

3.1. Optimization of Extractive Solvents on Ochratoxin Recovery

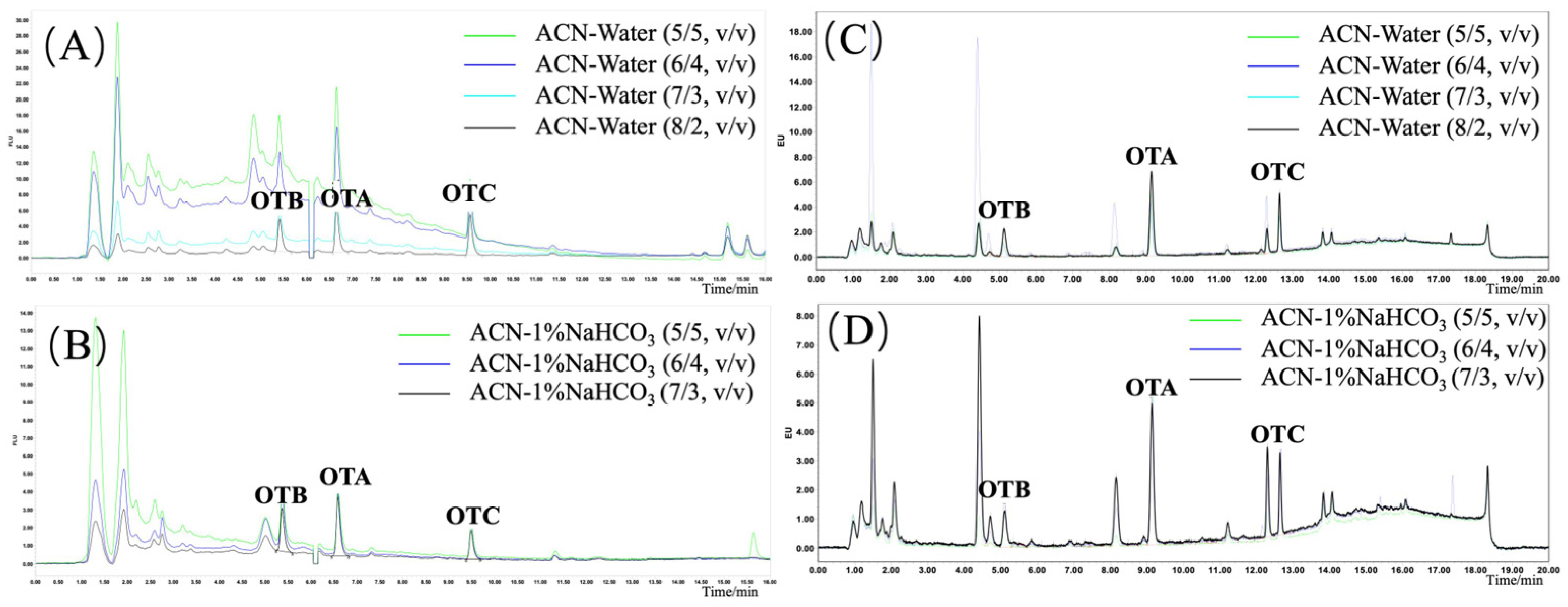

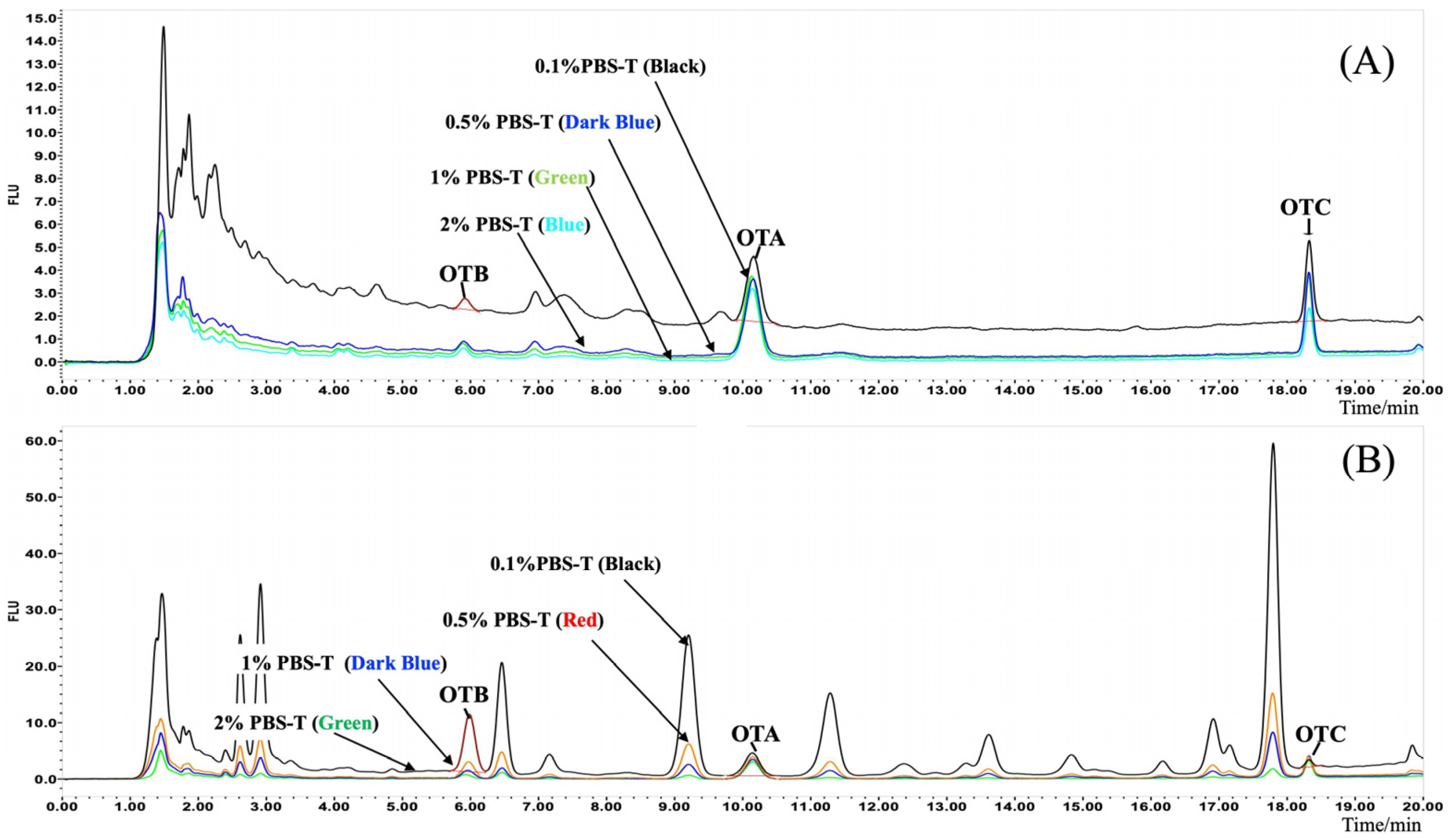

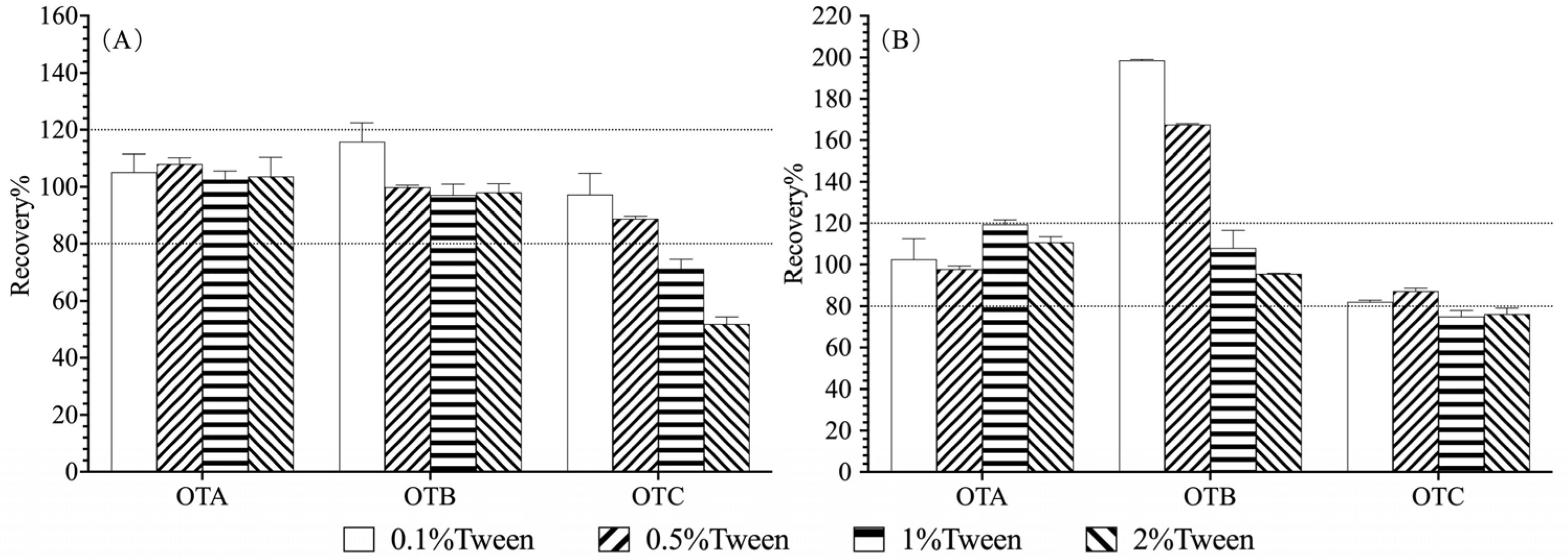

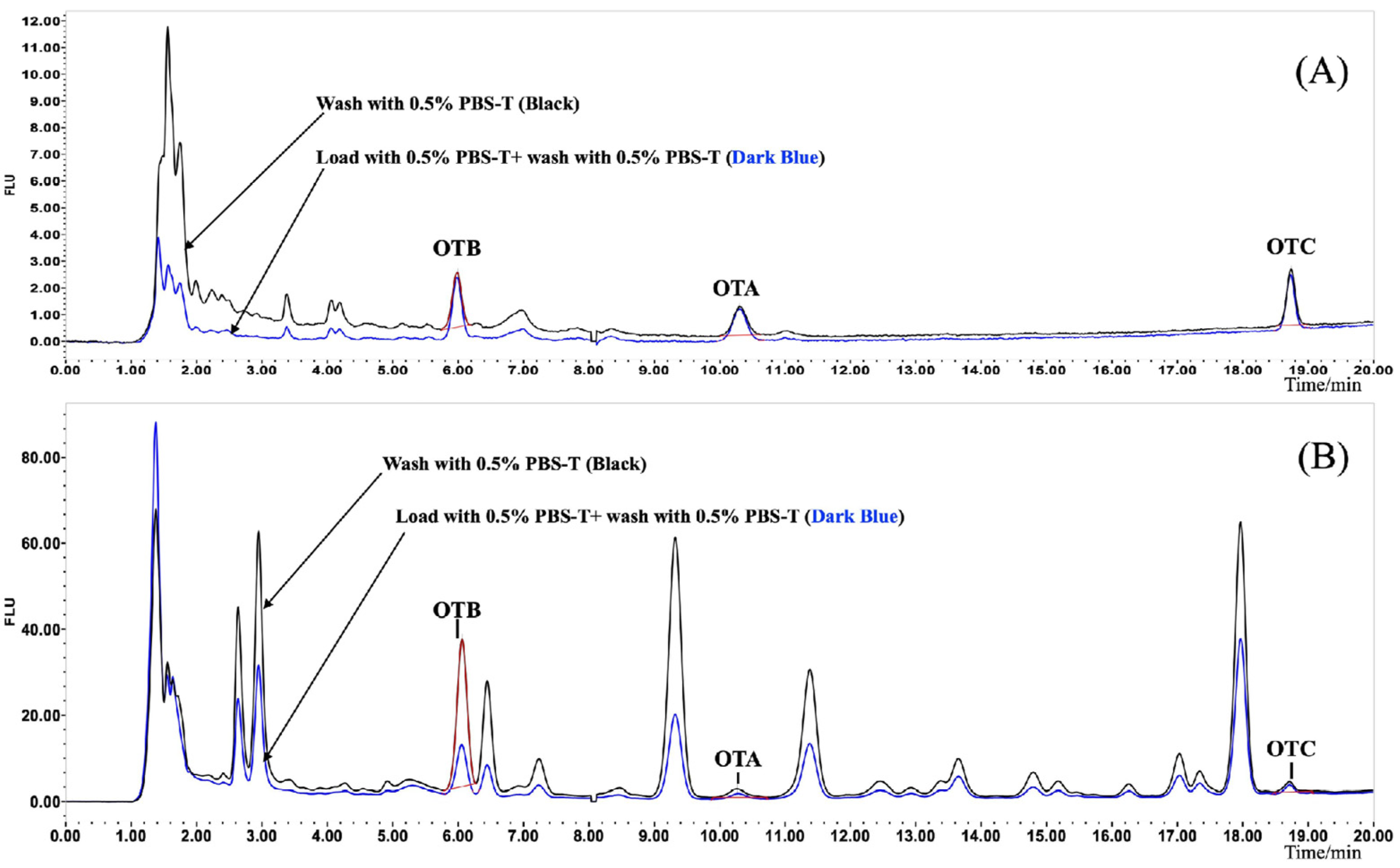

3.2. Optimization of IAC Condition and Clean-Up Protocols

3.3. Validation of HPLC-FLD and UHPLC-MS/MS Methodology

3.4. Comparison of HPLC-FLD and UHPLC-MS/MS Method

3.5. Comparing the Method with Previous Studies

3.6. Identification and Quantification of OTs in Commercial Coffee and Spices

3.7. Adaptability of the Method to Other Matrices

4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oliveira, F.d.S.d.; Andrade, E.T.d.; Viegas, C.; Souza, J.R.S.C.d.; Rabelo, G.F.; Viegas, S. Hidden Hazards: A Literature Review on Occupational Exposure to Fungi and Mycotoxins in the Coffee Industry. Aerobiology 2025, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newerli-Guz, J.; Śmiechowska, M.; Pigłowski, M. Notifications related to herbs and spices reported in the rapid alert system for food and feed (RASFF) in 1999–2023. Food Control 2026, 181, 111735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janković, M.; Torović, L. Spicing up the risk—Unveiling health hazards in herbs and spices. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 146, 107964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banahene, J.C.M.; Ofosu, I.W.; Odai, B.T.; Lutterodt, H.E.; Agyemang, P.A.; Ellis, W.O. Ochratoxin A in food commodities: A review of occurrence, toxicity, and management strategies. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, L.; Han, M.; Wang, X.; Guo, Y. Ochratoxin A: Overview of Prevention, Removal, and Detoxification Methods. Toxins 2023, 15, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csenki, Z.; Garai, E.; Faisal, Z.; Csepregi, R.; Garai, K.; Sipos, D.K.; Szabó, I.; Kőszegi, T.; Czéh, Á.; Czömpöly, T.; et al. The individual and combined effects of ochratoxin A with citrinin and their metabolites (ochratoxin B, ochratoxin C, and dihydrocitrinone) on 2D/3D cell cultures, and zebrafish embryo models. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021, 158, 112674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, G.; Burkert, B.; Rosner, H.; Köhler, H. Effects of the mycotoxin ochratoxin A and some of its metabolites on human kidney cell lines. Toxicol. Vitr. 2003, 17, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoteit, M.; Abbass, Z.; Daou, R.; Tzenios, N.; Chmeis, L.; Haddad, J.; Chahine, M.; Al Manasfi, E.; Chahine, A.; Poh, O.B.J.; et al. Dietary Exposure and Risk Assessment of Multi-Mycotoxins (AFB1, AFM1, OTA, OTB, DON, T-2 and HT-2) in the Lebanese Food Basket Consumed by Adults: Findings from the Updated Lebanese National Consumption Survey through a Total Diet Study Approach. Toxins 2024, 16, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhou, S.; Lyu, B.; Qiu, N.; Li, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, Y. Dietary exposure to fumonisins and ochratoxins in the Chinese general population during 2007–2020: Results from three consecutive total diet studies. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 159, 112768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, R.; Shetty, S.A.; Young, M.F.; Ryan, P.B.; Rangiah, K. Quantification of aflatoxin and ochratoxin contamination in animal milk using UHPLC-MS/SRM method: A small-scale study. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 3453–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholova, A.; Lhotska, I.; Uhrova, A.; Spanik, I.; Machynakova, A.; Solich, P.; Svec, F.; Satinsky, D. Determination of Ochratoxin A and Ochratoxin B in Archived Tokaj Wines (Vintage 1959–2017) Using On-Line Solid Phase Extraction Coupled to Liquid Chromatography. Toxins 2020, 12, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Villeda, B.; Lobos, O.; Aguilar-Zuniga, K.; Carrasco-Sánchez, V. Ochratoxins in Wines: A Review of Their Occurrence in the Last Decade, Toxicity, and Exposure Risk in Humans. Toxins 2021, 13, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaikel-Viquez, D.; Granados, F.; Gómez-Arrieta, A.; Vásquez-Flores, J.; Morales-Calvo, F.; Argeñal-Avendaño, N.; Álvarez-Corvo, D.; Artavia, G.; Gómez-Salas, G.; Wang, B.; et al. Occurrence of ochratoxins in coffee and risk assessment of ochratoxin a in a Costa Rican urban population. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2024, 42, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, H.; Wei, W.; Zhao, J. Ratiometric absorbance and fluorescence dual model immunoassay for detecting ochratoxin a based on porphyrin metalation. Food Chem. 2025, 464, 141608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charles, I.D.; Zhang, M.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, Z.; Liu, B. An albumin-based indicator displacement assay enables ratiometric detection of total ochratoxins in food. Microchem. J. 2025, 212, 113215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Commission Regulation (EU) 915/2023 of 25 April 2023 on maximum levels for certain contaminants in food and repealing Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006. Off. J. Eur. Union 2023, 119, 55. [Google Scholar]

- GB 2761-2017; Maximum Limit of Mycotoxins in Food. China’s Ministry of Health: Beijing, China, 2017.

- Ganesan, A.R.; Mohan, K.; Karthick Rajan, D.; Pillay, A.A.; Palanisami, T.; Sathishkumar, P.; Conterno, L. Distribution, toxicity, interactive effects, and detection of ochratoxin and deoxynivalenol in food: A review. Food Chem. 2022, 378, 131978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, M.S.; Jeyaram, K.; Datta, S.; Chandrasekar, N.; Balaji, R.; Selvarajan, E. Detection, Contamination, Toxicity, and Prevention Methods of Ochratoxins: An Update Review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 13974–13989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yan, L.; Huang, Q.; Bu, T.; Yu, S.; Zhao, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, D. Highly sensitive simultaneous detection of major ochratoxins by an immunochromatographic assay. Food Control 2018, 84, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agriopoulou, S.; Stamatelopoulou, E.; Varzakas, T. Advances in Analysis and Detection of Major Mycotoxins in Foods. Foods 2020, 9, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegedüs, Z.; Gömöri, C.; Varga, M.; Vágvölgyi, C.; Szekeres, A. Separation of ochratoxins by centrifugal partition chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2024, 1724, 464898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Huang, P.; Wei, F.; Ying, G.; Lu, J.; Zhou, L.; Kong, W. Regeneration and Reuse of Immunoaffinity Column for Highly Efficient Clean-Up and Economic Detection of Ochratoxin A in Malt and Ginger. Toxins 2018, 10, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Z.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Hammock, B.D.; Xu, Y. Nanobody-based fluorescence resonance energy transfer immunoassay for noncompetitive and simultaneous detection of ochratoxin a and ochratoxin B. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 251, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Ye, B.; Li, H.; Yan, P.; Chen, D.; Zhao, M. Enhanced selectivity for convenient extraction of acidic mycotoxins using a miniaturized centrifugal integrated cold-induced phase separation: Determination of fumonisins and ochratoxins in cereals as a proof-of-concept study. Food Chem. 2024, 454, 139715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.J.; Wang, M.L.; Cai, Z.X.; Huang, B.F.; Xu, X.M. Application of ultra-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry in analysis of aflatoxins and ochratoxin A in hotpot seasoning. Chin. J. Food Hyg. 2025, 37, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, M.; Gao, H.; Gao, S.; Liu, Y.; Yao, J.; Liu, H.; Wang, F.; Chen, M.; Song, L.; Wang, T.; et al. Electromembrane extraction coupled with UPLC-FLD for the determination of ochratoxin A in food crops. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 142, 107518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonell-Rozas, L.; Mihalache, O.A.; Bruni, R.; Dall’Asta, C. Comprehensive Analysis of Mycotoxins in Green Coffee Food Supplements: Method Development, Occurrence, and Health Risk Assessment. Toxins 2025, 17, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakasham, K.; Gurrani, S.; Shiea, J.; Wu, M.-T.; Wu, C.-F.; Lin, Y.-C.; Tsai, B.; Huang, P.-C.; Andaluri, G.; Ponnusamy, V.K. Ultra-sensitive determination of Ochratoxin A in coffee and tea samples using a novel semi-automated in-syringe based coagulant-assisted fast mycotoxin extraction (FaMEx) technique coupled with UHPLC-MS/MS. Food Chem. 2023, 417, 135951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BS EN 17250:2020; Foodstuffs—Determination of Ochratoxin A in Spices, Liquorice, Cocoa and Cocoa Products by IAC Clean-up and HPLC-FLD. BSI Standards Publication: London, UK, 2020.

- EN 14132:2009; Foodstuffs—Determination of Ochratoxin A in Barley and Roasted Coffee—HPLC Method with Immunoaffinity Column Clean-Up. BSI Standards Publication: London, UK, 2009.

- European Commission (EC). No 401/2006 of 23 February 2006 laying down the methods of sampling and analysis for the official control of the levels of mycotoxins in foodstuffs. Off. J. Eur. Union 2006, 70, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Kmellár, B.; Fodor, P.; Pareja, L.; Ferrer, C.; Martínez-Uroz, M.A.; Valverde, A.; Fernandez-Alba, A.R. Validation and uncertainty study of a comprehensive list of 160 pesticide residues in multi-class vegetables by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2008, 1215, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakshir, K.; Dehghani, A.; Nouraei, H.; Zareshahrabadi, Z.; Zomorodian, K. Evaluation of fungal contamination and ochratoxin A detection in different types of coffee by HPLC-based method. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2021, 35, e24001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouakhssase, A.; Fatini, N.; Ait Addi, E. A facile extraction method followed by UPLC-MS/MS for the analysis of aflatoxins and ochratoxin A in raw coffee beans. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2021, 38, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iha, M.H.; Rodrigues, M.L.; Trucksess, M.W. Multitoxin immunoaffinity analysis of aflatoxins and ochratoxin A in spices. J. Food Saf. 2021, 41, e12921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanshetty, M.; Shinde, R.; Goon, A.; Oulkar, D.; Elliott, C.T.; Banerjee, K. Analysis of aflatoxins and ochratoxin a in chilli powder using ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection and tandem mass spectrometry. Mycotoxin Res. 2022, 38, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remiro, R.; Ibáñez-Vea, M.; González-Peñas, E.; Lizarraga, E. Validation of a liquid chromatography method for the simultaneous quantification of ochratoxin A and its analogues in red wines. J. Chromatogr. A 2010, 1217, 8249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | Parent Ion/(m/z) | Product Ion/(m/z) | DP/V | CE/eV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OTA | 404.0 | 239.1 *, 358.1 | 100 | 34, 20 |

| OTB | 370.0 | 205.1 *, 324.1 | 70 | 28, 19 |

| OTC | 432.1 | 239.1 *, 358.1 | 70 | 35, 22 |

| 13C-OTA | 424.2 | 250.1 | 100 | 32 |

| 13C-OTB | 390.2 | 216.1 | 70 | 33 |

| 13C-OTC | 452.2 | 250.1 | 70 | 36 |

| IAC Brand No. b | Column Reactivity % a | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| OTA | OTB | OTC | |

| 1 c | 98.90 | 107.8 | 100.6 |

| 2 | 109.4 | 109.6 | 88.41 |

| 3 | 95.31 | 93.75 | 90.00 |

| 4 | 108.4 | 108.1 | 86.00 |

| 5 | 108.9 | 107.0 | 92.50 |

| 6 | 98.04 | 99.20 | 71.28 |

| 7 | 88.18 | 87.68 | 67.44 |

| 8 | 82.4 | 80.32 | 77.52 |

| 9 | 89.63 | 83.98 | 21.94 |

| Compound | HPLC-FLD | UHPLC-MS/MS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOQ (µg/kg) | Spiking (µg/kg) | Roasted Coffee * | Sichuan Pepper * | LOQ (µg/kg) | Spiking (µg/kg) | Roasted Coffee * | Sichuan Pepper * | |

| OTA | 0.3 | 0.3 | 98.99 ± 8.81 | 95.83 ± 5.35 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 95.93 ± 2.04 | 99.18 ± 4.57 |

| 5 | 99.97 ± 4.68 | 105.63 ± 2.50 | 5 | 104.07 ± 5.12 | 99.11 ± 2.50 | |||

| 10 | 96.58 ± 4.71 | 99.80 ± 4.41 | 10 | 109.83 ± 7.11 | 96.99 ± 1.96 | |||

| OTB | 0.2 | 0.3 | 85.56 ± 6.36 | 111.11 ± 5.59 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 92.26 ± 2.67 | 110.09 ± 3.94 |

| 5 | 100.44 ± 3.48 | 92.41 ± 1.79 | 5 | 95.97 ± 4.06 | 95.49 ± 3.97 | |||

| 10 | 89.68 ± 3.86 | 91.71 ± 3.11 | 10 | 100.53 ± 7.85 | 94.05 ± 2.84 | |||

| OTC | 0.2 | 0.3 | 86.11 ± 5.15 | 82.22 ± 5.54 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 103.94 ± 3.51 | 112.51 ± 3.55 |

| 5 | 95.54 ± 1.99 | 82.17 ± 3.01 | 5 | 98.83 ± 4.86 | 99.89 ± 3.76 | |||

| 10 | 85.69 ± 4.30 | 82.00 ± 2.10 | 10 | 104.05 ± 5.09 | 98.88 ± 1.55 | |||

| Compound | Instant Coffee | Roasted Coffee | Cumin | Sichuan Pepper | White Pepper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13C-OTA | 107.7 | 88.32 | 109.9 | 82.49 | 72.65 |

| 13C-OTB | 93.63 | 108.0 | 105.8 | 101.4 | 96.38 |

| 13C-OTC | 74.53 | 35.27 | 52.87 | 62.21 | 12.61 |

| Samples | Assigned Content (µg/kg) | HPLC-FLD (µg/kg) | UHPLC-MS/MS (µg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coffee | 3.18 ± 1.4 | 3.54 ± 0.20 * | 3.55 ± 0.24 |

| Mixed spice | 16.0 ± 7.0 | 20.1 ± 1.4 | 20.5 ± 0.8 |

| Analyte. | Extraction | Pretreatment | Matrix | Instrument | LOD (μg/kg) | LOQ (μg/kg) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OTA/OTB/OTC | ACN-water (8/2, v/v) | IAC | Coffee and spices | LC-MS/MS HPLC-FLD | 0.1; 0.3 | 0.3; 1 | This study |

| OTA | MEOH-3%NaHCO3 (50 + 50, v/v) | IAC | spices, liquorice, cocoa, and cocoa products | HPLC-FLD | / | 1 | [30] |

| OTA | MEOH-3%NaHCO3 (50 + 50, v/v) | Phenyl silane SPE-IAC | Roasted coffee and barley | HPLC-FLD | / | 0.6 | [31] |

| OTA | MEOH-water (8/2, v/v) | IAC | Coffee | HPLC-FLD | 0.47 | 1.23 | [34] |

| AFTs/OTA | MEOH-ACN (6/4, v/v) | QuEChERS method | Raw coffee beans | LC-MS/MS | / | 0.6 | [35] |

| AFTs/OTA | 3%NaHCO3; ACN-water; MEOH-0.5%NaHCO3 | IAC | Spices | HPLC-FLD | <0.1 | / | [36] |

| AFTs/OTA | MEOH-water (8/2, v/v) | IAC | Chilli powder | LC-MS/MS HPLC-FLD | / | 1; 0.5 | [37] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, J.; Cai, Z.; Wang, M.; Xu, X.; Shen, H. Comprehensive IAC Cross-Reactivity Validation and Stabilized Method Development for Ochratoxin A, B, and C in Complex Coffee and Spice Matrices. Foods 2025, 14, 4102. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234102

Xu J, Cai Z, Wang M, Xu X, Shen H. Comprehensive IAC Cross-Reactivity Validation and Stabilized Method Development for Ochratoxin A, B, and C in Complex Coffee and Spice Matrices. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4102. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234102

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Jiaojiao, Zengxuan Cai, Mengli Wang, Xiaomin Xu, and Haitao Shen. 2025. "Comprehensive IAC Cross-Reactivity Validation and Stabilized Method Development for Ochratoxin A, B, and C in Complex Coffee and Spice Matrices" Foods 14, no. 23: 4102. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234102

APA StyleXu, J., Cai, Z., Wang, M., Xu, X., & Shen, H. (2025). Comprehensive IAC Cross-Reactivity Validation and Stabilized Method Development for Ochratoxin A, B, and C in Complex Coffee and Spice Matrices. Foods, 14(23), 4102. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234102