A New Approach with Agri-Food By-Products: A Case Study of Fortified Fresh Pasta with Red Onion Peels

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

2.2. Fresh Pasta Preparation

2.3. Sensory Analysis

2.4. Pasta Cooking Quality

2.5. Total Polyphenolic Analysis

2.6. Antioxidant Activity

2.7. Starch Hydrolysis and Predicted Glycaemic Index

2.8. Fibre Content

2.9. Global Quality Index Calculation

2.10. Statistical Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sensory Quality

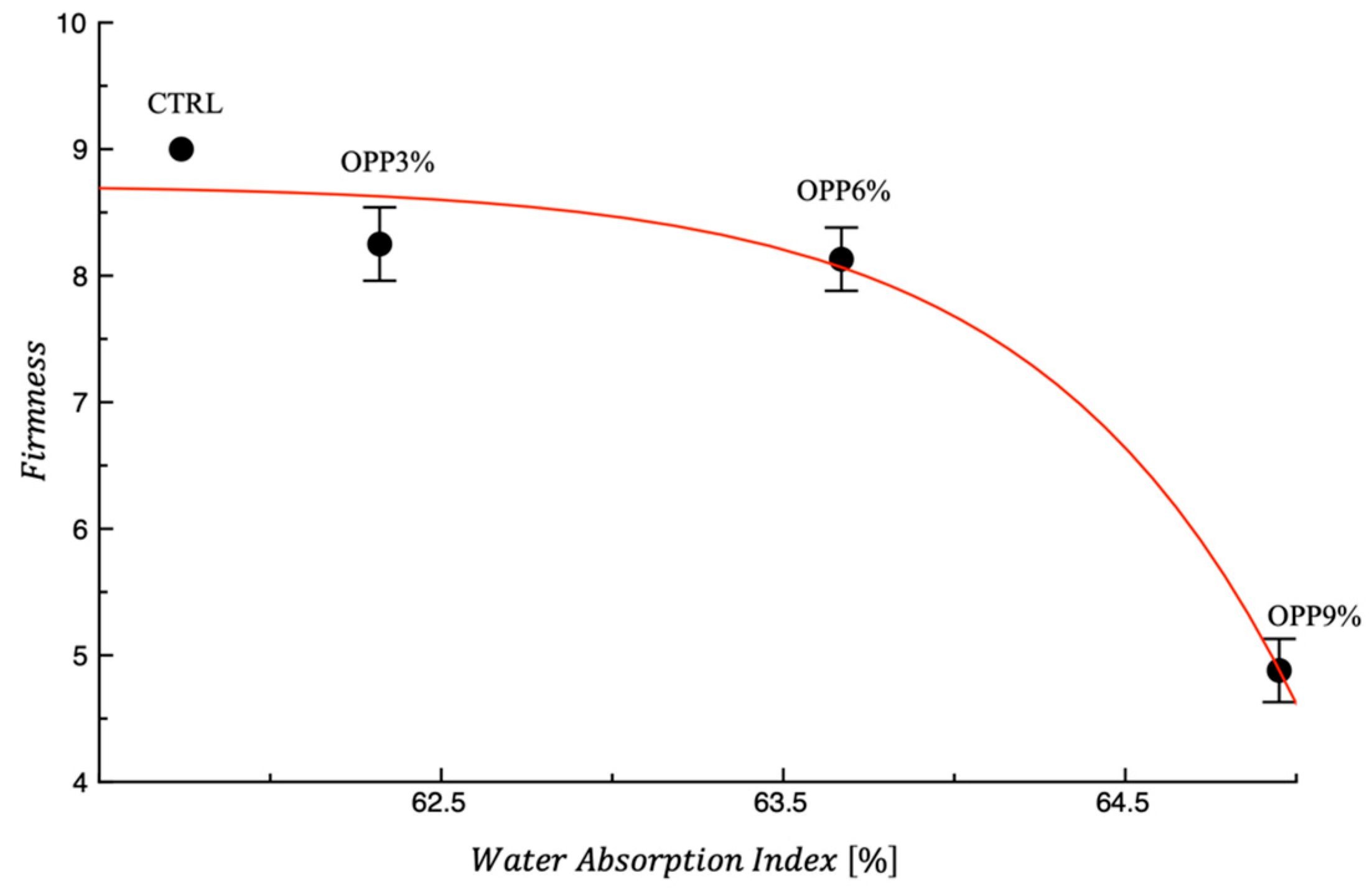

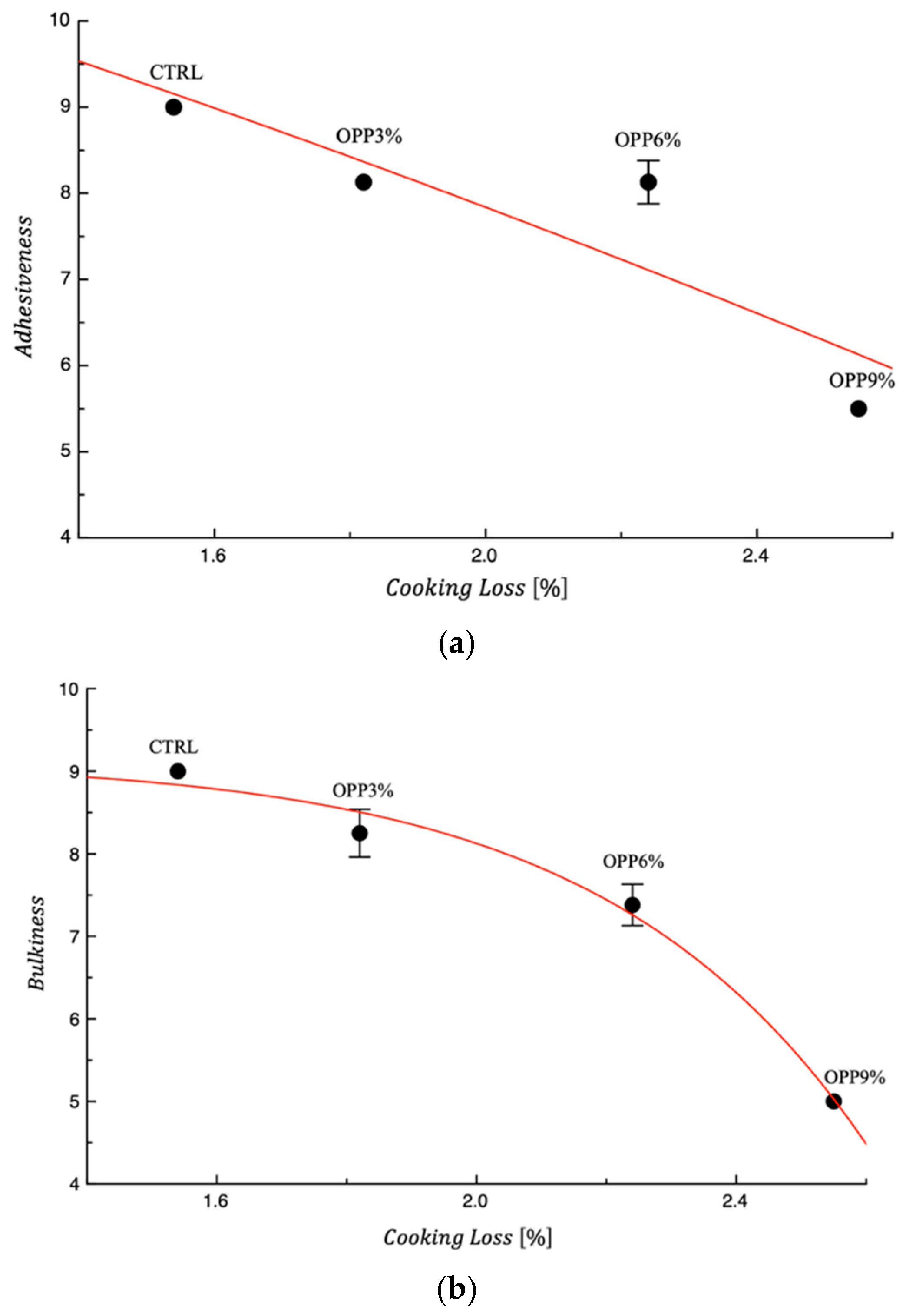

3.2. Technological Properties

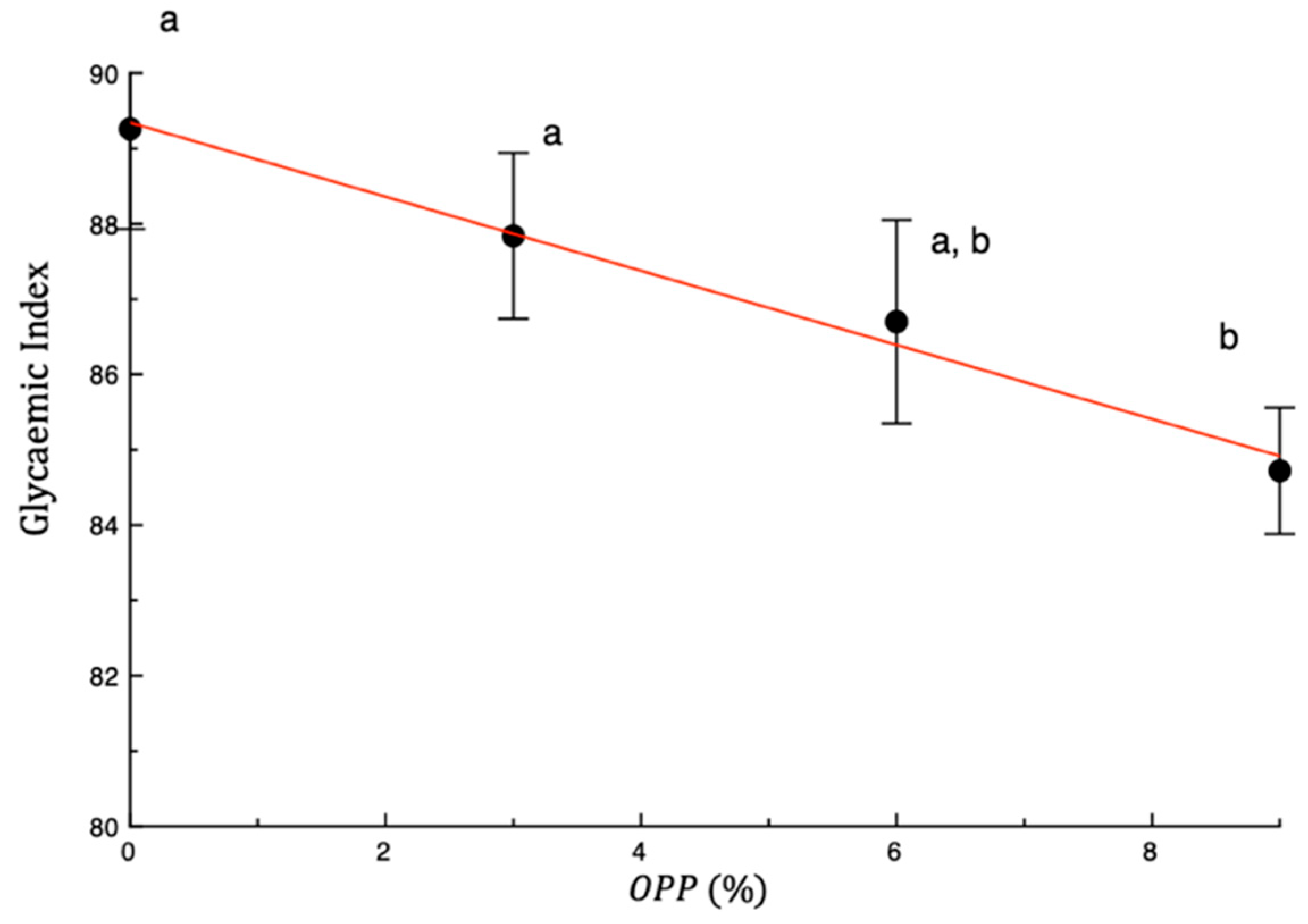

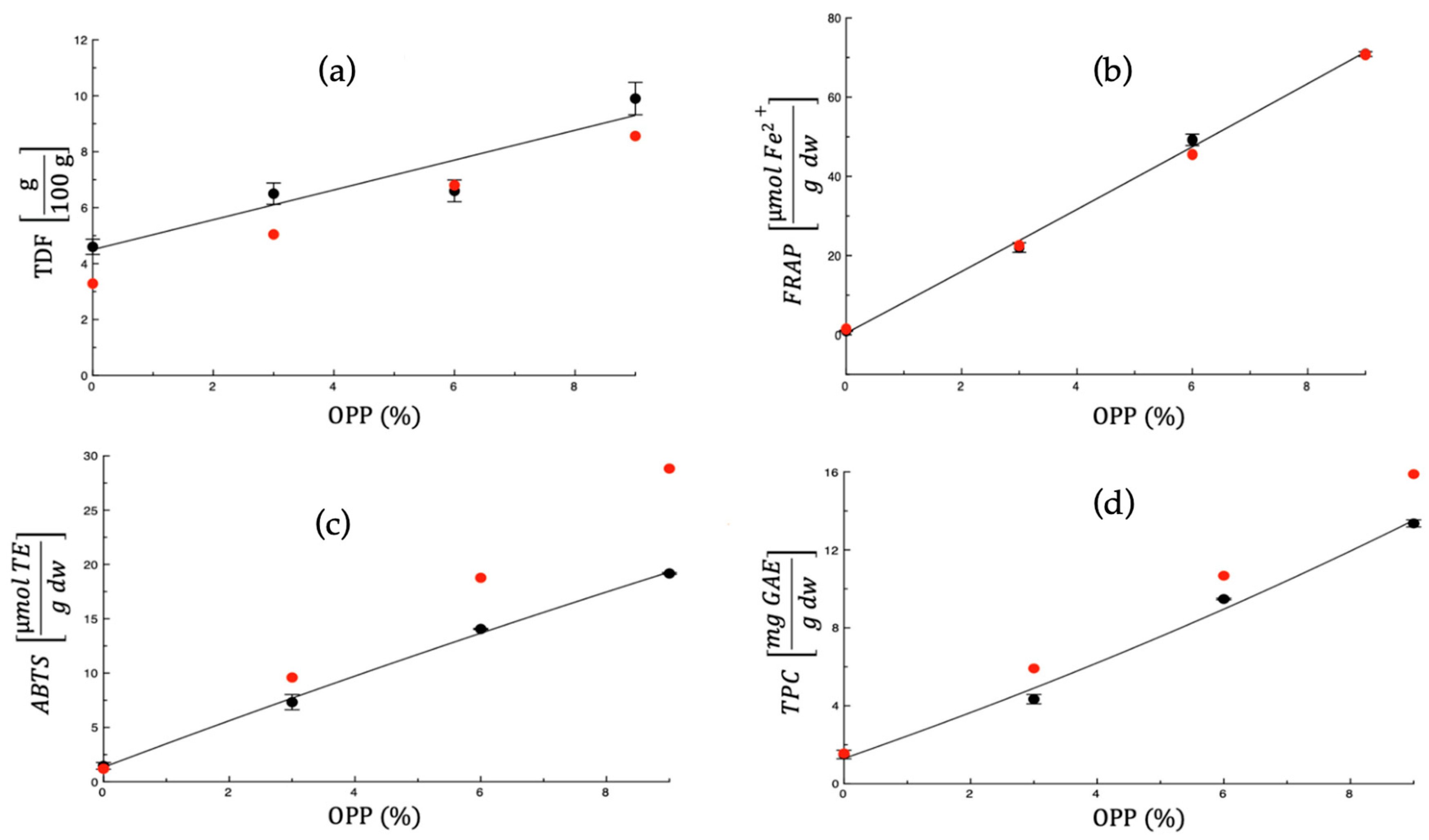

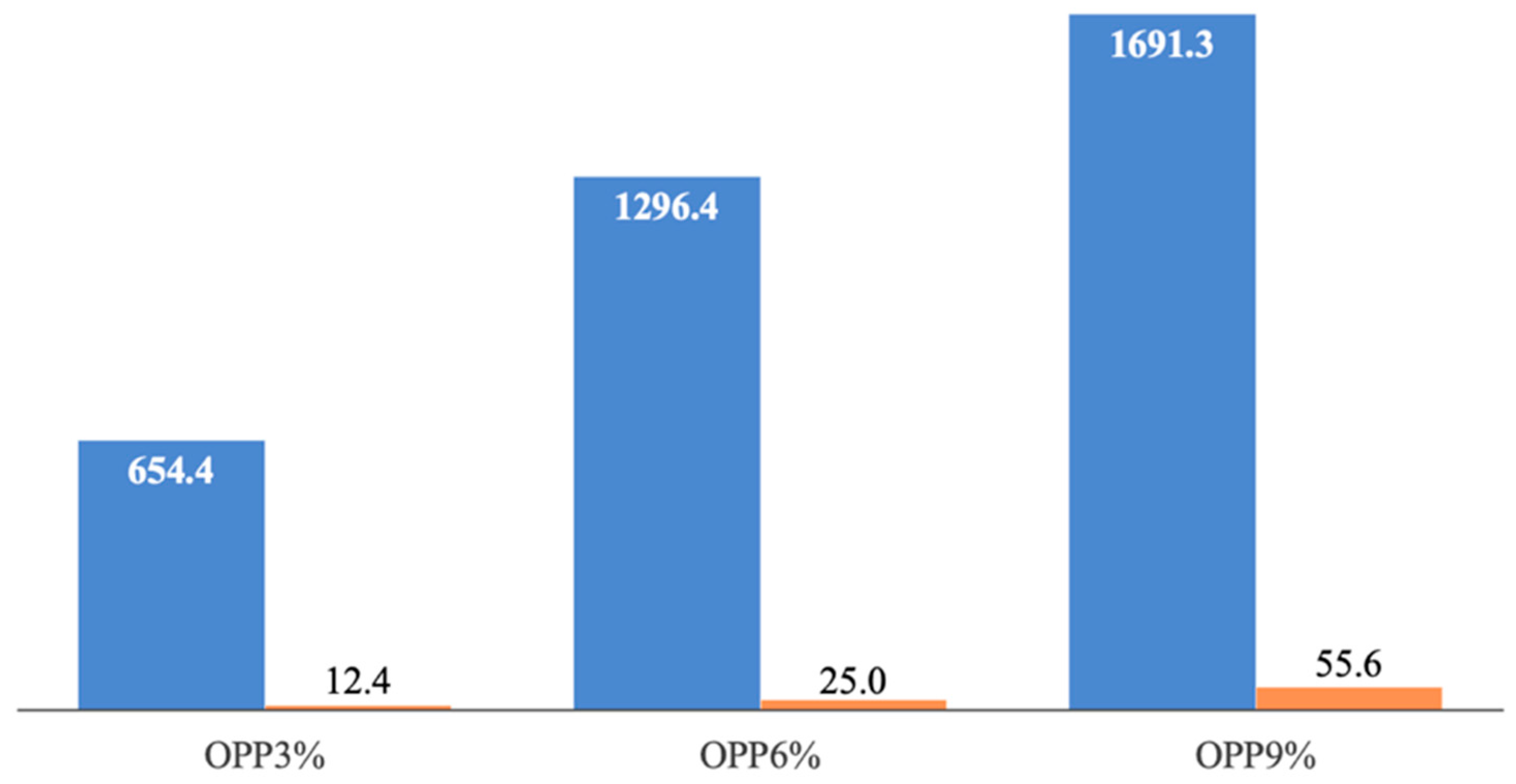

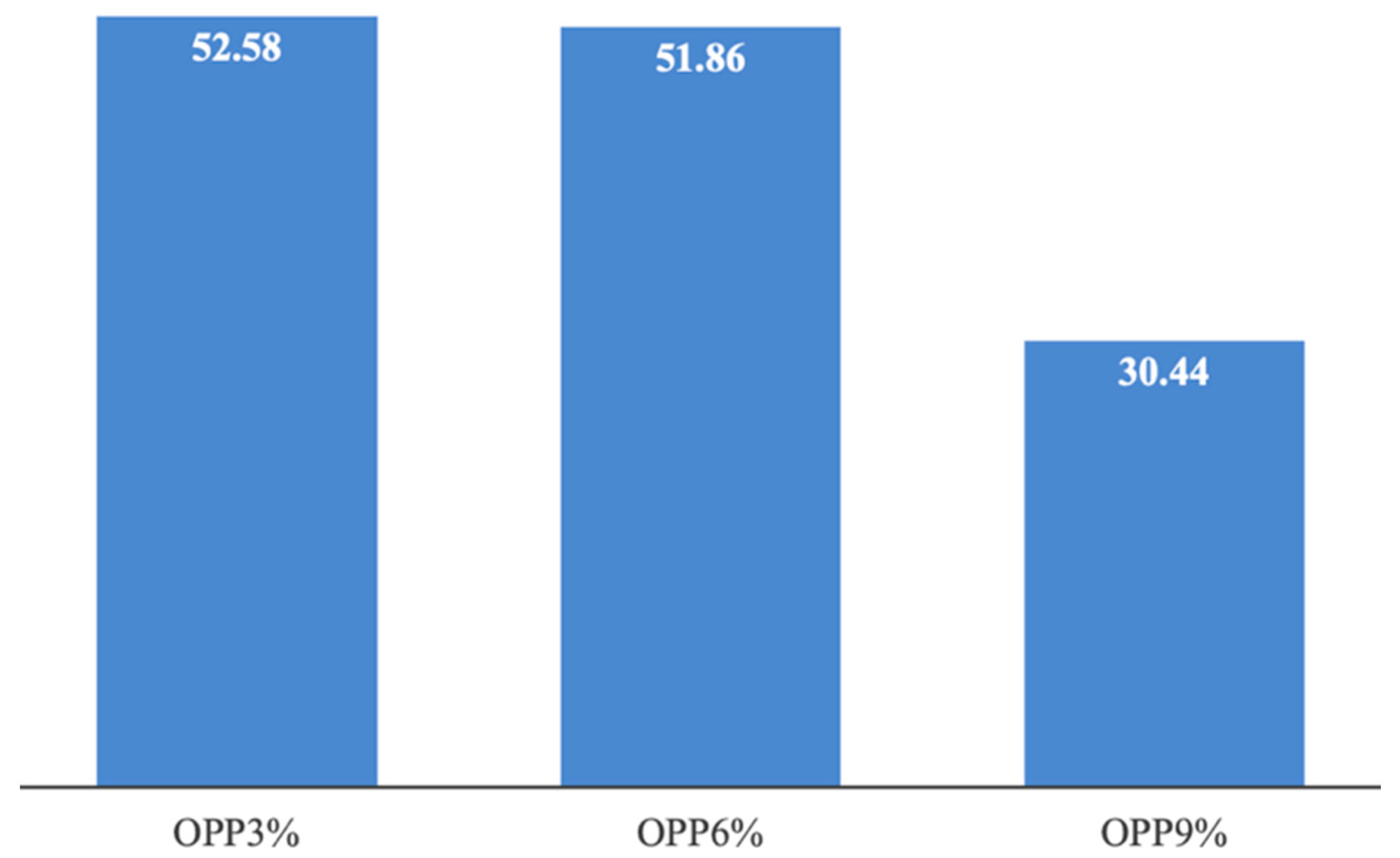

3.3. Nutritional Properties and Glycaemic Index

3.4. Global Quality Index

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coman, V.; Teleky, B.E.; Mitrea, L.; Martău, G.A.; Szabo, K.; Călinoiu, L.F.; Vodnar, D.C. Bioactive Potential of Fruit and Vegetable Wastes. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2020, 91, 157–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, P.; Indrani, D.; Singh, R.P. Effect of dried pomegranate (Punica granatum) peel powder (DPPP) on textural, organoleptic and nutritional characteristics of biscuits. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 65, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupasinghe, H.; Wang, L.; Huber, G.; Pitts, N. Effect of Baking on Dietary Fibre and Phenolics of Muffins Incorporated with Apple Skin Powder. Food Chem. 2008, 107, 1217–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés, A.I.; Petrón, M.J.; Adámez, J.D.; López, M.; Timón, M.L. Food By-Products as Potential Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Additives in Chill Stored Raw Lamb Patties. Meat Sci. 2017, 129, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergezer, H.; Serdaroglu, M. Antioxidant Potential of Artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.) Byproducts Extracts in Raw Beef Patties during Refrigerated Storage. J. Food Measur. Charact. 2018, 12, 982–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouchouli, V.; Kalogeropoulos, N.; Konteles, S.J.; Karvela, E.; Makris, D.P.; Karathanos, V.T. Fortification of Yoghurts with Grape (Vitis vinifera) Seed Extracts. LWT 2013, 53, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchiani, R.; Bertolino, M.; Belviso, S.; Giordano, M.; Ghirardello, D.; Torri, L.; Piochi, M.; Zeppa, G. Yogurt Enrichment with Grape Pomace: Effect of Grape Cultivar on Physicochemical, Microbiological and Sensory Properties: Grape Skin Flour and Yogurt Quality. J. Food Qual. 2016, 39, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucera, A.; Costa, C.; Marinelli, V.; Saccotelli, M.; Del Nobile, M.A.; Conte, A. Fruit and Vegetable By-Products to Fortify Spreadable Cheese. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, B.; Cai, Y.Z.; Brooks, J.D.; Corke, H. Potential Application of Spice and Herb Extracts as Natural Preservatives in Cheese. J. Med. Food 2011, 14, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drabinska, N.; Nogueira, M.; Szmatowicz, B. Valorisation of broccoli by-products: Technological, sensory and flavour properties of durum pasta fortified with broccoli leaf powder. Molecules 2022, 27, 4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panza, O.; Conte, A.; Del Nobile, M.A. Recycling of fig peels to enhance the quality of handmade pasta. LWT 2022, 168, 113872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak-Majewska, M.; Teterycz, D.; Muszyński, S.; Radzki, W.; Sykut-Domańska, E. Influence of onion skin powder on nutritional and quality attributes of wheat pasta. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagar, N.A.; Pareek, S.; Gonzalez-Aguilar, G.A. Quantification of flavonoids, total phenols and antioxidant properties of onion skin: A comparative study of fifteen Indian cultivars. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 2423–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prokopov, T.; Chonova, V.; Slavov, A.; Dessev, T.; Dimitrov, N.; Petkova, N. Effects on the quality and health-enhancing properties of industrial onion waste powder on bread. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 5091–5097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Gregorio, R.M.; García-Falcon, M.S.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Rodrigues, A.S.; Almeida, D.P.F. Identification and quantification of flavonoids in traditional cultivars of red and white onions at harvest. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2010, 23, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sadda, R.R.; Amira, R.E.-S.; Heba, O.E.S.; Elhossein, A.M.; Omnia, H.G.; Mohamed, M.E.-Z.; Youssef, Y.E.; Wael, S.E.-T. Evaluation of biological potential of red onion skin extract for anticancer and antimicrobial activities. Process Biochem. 2024, 147, 587–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosazad, S.; Peyman, G.; Razzagh, M.; Saeed, S.; Roghayeh, V.; Soltani, A. Antibacterial and antioxidant properties of colorant extracted from red onion skin. J. Chem. Health Risks 2019, 3, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elberry, A.A.; Mufti, S.; Al-Maghrabi, J.; Sattar, E.; Ghareib, S.A.; Mosli, H.A.; Gabr, S.A. Immunomodulatory effect of red onion (Allium cepa L.) scale extract on experimentally induced atypical prostatic hyperplasia. Mediat. Inflam. 2014, 13, 640746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.Y.; Lee, H.; Woo, J.S.; Jang, H.H.; Hwang, S.J.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, W.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Choue, R.; Cha, Y.J.; et al. Effect of onion peel extract on endothelial function and endothelial progenitor cells in overweight and obese individuals. Nutrition 2015, 31, 1131–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, J.S.; Park, E. Cytotoxic and anti-inflammatory effects of onion peel extract on lipopolysaccharide stimulated human colon carcinoma cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 62, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hager, A.S.; Czerny, M.; Bez, J.; Zannini, E.; Arendt, E.K. Starch properties, in vitro digestibility and sensory evaluation of fresh egg pasta produced from oat, teff and wheat flour. J. Cereal Sci. 2013, 58, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Association of Cereal Chemistry. Approved Methods of the American Association of Cereal Chemistry; Methods 44–19, 08–03, 46–13, 66–50; American Association of Cereal Chemistry: Saint Paul, MN, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Padalino, L.; Mastromatteo, M.; Lecce, L.; Spinelli, S.; Contò, F.; Del Nobile, M.A. Chemical composition, sensory and cooking quality evaluation of durum wheat spaghetti enriched with pea flour. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 49, 1544–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavaro, A.R.; De Bellis, P.; Montemurro, M.; D’Antuono, I.; Linsalata, V.; Cardinali, A. Characterization and functional application of artichoke bracts: Enrichment of bread with health promoting compounds. LWT 2025, 215, 117256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Antuono, I.; Kontogianni, V.G.; Kotsiou, K.; Linsalata, V.; Logrieco, A.F.; Tasioula-Margari, M.; Cardinali, A. Polyphenolic characterization of Olive Mill Waste Waters, coming from Italian and Greek olive cultivars, after membrane technology. Food Res. Int. 2014, 65, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavaro, A.R.; De Bellis, P.; Linsalata, V.; Rucci, S.; Predieri, S.; Cianciabella, M.; Tamburino, R.; Cardinali, A. Valorization of Artichoke Bracts in Pasta Enrichment: Impact on Nutritional, Technological, Antioxidant, and Sensorial Properties. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant Activity Applying an Improved ABTS Radical Cation Decolorization Assay. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. The Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma (FRAP) as a Measure of “Antioxidant Power”: The FRAP Assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goñi, I.; Garcia-Alonso, A.; Saura-Calixto, F. A starch hydrolysis procedure to estimate glycemic index. Nutr. Reser. 1997, 17, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC 985.29-1986 (2003); Total Dietary Fiber in Foods. Enzymatic-Gravimetric Method. AOAC International: Rockville, MA, USA, 2003.

- Lordi, A.; Caro, D.; Le Rose, A.; Del Nobile, M.A.; Conte, A. Quality and environmental impact of meat burgers fortified with tomato by-products. LWT 2025, 229, 118182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sant’Anna, V.; Christiano, F.; Damasceno Ferreira Marczak, L.; Tessaro, I.C.; Thys, R.C.S. The effect of the incorporation of grape marc powder in fettuccini pasta properties. LWT 2014, 58, 497–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, F.; Tolve, R.; Rainero, G.; Bordiga, M.; Brennan, C.S.; Simonato, B. Technological, nutritional and sensory properties of pasta fortified with agro-industrial by-products: A review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 4356–4366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobota, A.; Rzedzicki, Z.; Zarzycki, P.; Kuzawińska, E. Application of common wheat bran for the industrial production of high-fibre pasta. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 50, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foschia, M.; Peressini, D.; Sensidoni, A.; Brennan, M.; Brennan, C.S. How combinations of dietary fibres can affect physicochemical characteristics of pasta. LWT 2015, 61, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudoricǎ, C.M.; Kuri, V.; Brennan, C.S. Nutritional and physicochemical characteristics of dietary fiber enriched pasta. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Brennan, M.; Serventi, L.; Mason, S.; Brennan, C.S. How the inclusion of mushroom powder can affect the physicochemical characteristics of pasta. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 51, 2433–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, M.; Braojos, M.; Fernández, R.; Parle, F. Utilization of By-Products from the Fruit and Vegetable Processing Industry in Pasta Production. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Barbhai, M.D.; Hasan, M.; Dhumal, S.; Singh, S.; Pandiselvam, R.; Rais, N.; Natta, S.; Senapathy, M.; Sinha, N.; et al. Onion (Allium cepa L.) peel: A review on the extraction of bioactive compounds, its antioxidant potential, and its application as a functional food ingredient. J. Food Sci. 2022, 87, 4289–4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramires, F.A.; Bavaro, A.R.; D’Antuono, I.; Linsalata, V.; D’Amico, L.; Baruzzi, F.; Pinto, L.; Tarantini, A.; Garbetta, A.; Cardinali, A.; et al. Liquid submerged fermentation by selected microbial strains for onion skins valorization and its effects on polyphenols. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 39, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viera, V.B.; Piovesan, N.; Rodrigues, J.B.; Mello, R.; Prestes, R.C.; Santos, R.C.V.; Vaucher, R.A.; Hautrive, T.; Kubota, E.H. Extraction of phenolic compounds and evaluation of the antioxidant and antimicrobial capacity of red onion skin (Allium cepa L.). Int. Food Res. J. 2017, 24, 990–999. [Google Scholar]

- Sagar, N.A.; Pareek, S. Dough rheology, antioxidants, textural, physicochemical characteristics, and sensory quality of pizza base enriched with onion (Allium cepa L.) skin powder. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattivelli, A.; Nissen, L.; Casciano, F.; Tagliazucchi, D.; Gianotti, A. Impact of cooking methods of red-skinned onion on metabolic transformation of phenolic compounds and gut microbiota changes. Food Func. 2023, 14, 3509–3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chadorshabi, S.; Hallaj-Nezhadi, S.; Ghasempour, Z. Red onion skin active ingredients, extraction and biological properties for functional food applications. Food Chem. 2022, 386, 132737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, H.S.; Hassan, N.M.; El, M.H.A. The effect of using onion skin powder as a source of dietary fiber and antioxidants on properties of dried and fried noodles. Curr. Sci. Int. 2014, 3, 468–475. [Google Scholar]

- Michalak-Majewska, M.; Złotek, U.; Szymanowska, U.; Szwajgier, D.; Stanikowski, P.; Matysek, M.; Sobota, A. Antioxidant and potentially anti-inflammatory properties in pasta fortified with onion skin. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piechowiak, T.; Grzelak-Błaszczyk, K.; Bonikowski, R.; Balawejder, M. Optimization of extraction process of antioxidant compounds from yellow onion skin and their use in functional bread production. LWT 2020, 117, 108614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsebaie, E.M.; Essa, R.Y. Microencapsulation of red onion peel polyphenols fractions by freeze drying technicality and its application in cake. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2018, 42, e13654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedrniček, J.; Jirotkova, D.; Kadlec, J.; Laknerova, I.; Vrchotova, N.; Třiska, J.; Samkova, E.; Smetana, P. Thermal stability and bioavailability of bioactive compounds after baking of bread enriched with different onion by-products. Food Chem. 2020, 319, 126562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fares, C.; Platani, C.; Baiano, A.; Menga, V. Effect of processing and cooking on phenolic acid profile and antioxidant capacity of durum wheat pasta enriched with debranning fractions of wheat. Food Chem. 2010, 119, 1023–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, D.; Ciccoritti, R.; Nicoletti, I.; Nocente, F.; Corradini, D.; D’Egidio, M.G.; Taddei, F. From seed to cooked pasta: Influence of traditional and non-conventional transformation processes on total antioxidant capacity and phenolic acid content. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 69, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocchetti, G.; Lucini, L.; Chiodelli, G.; Giuberti, G.; Montesano, D.; Masoero, F.; Trevisan, M. Impact of boiling on free and bound phenolic profile and antioxidant activity of commercial gluten-free pasta. Food Res. Int. 2017, 100, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Jiménez, J.; Arranz, S.; Tabernero, M.; Díaz-Rubio, M.E.; Serrano, J.; Goñi, I.; Saura-Calixto, F. Updated Methodology to Determine Antioxidant Capacity in Plant Foods, Oils and Beverages: Extraction, Measurement and Expression of Results. Food Res. Int. 2008, 41, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowska-Bartosz, I.; Bartosz, G. Evaluation of The Antioxidant Capacity of Food Products: Methods, Applications and Limitations. Processes 2022, 10, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattivelli, A.; Di Lorenzo, A.; Conte, A.; Martini, S.; Tagliazucchi, D. Red-skinned onion phenolic compounds stability and bioaccessibility: A comparative study between deep-frying and air-frying. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 115, 105024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Commission Regulation (EU) No 1047/2012 of 8 November 2012 amending Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006 with regard to the list of nutrition claims Text with EEA relevance. Off. J. Eur. Union 2012, 310, 36–37. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, F.; Huang, H.; Luo, F.; Duan, R.; Zhou, Q.; Luo, J.; Luo, P.; Liu, L. Effects of adding food ingredients rich in dietary fiber and polyphenols on the microstructure, texture, starch digestibility and functional properties of Chinese steamed bun. Food Chem. X 2025, 31, 103178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ćorković, I.; Gašo-Sokač, D.; Pichler, A.; Šimunović, J.; Kopjar, M. Dietary Polyphenols as Natural Inhibitors of α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase. Life 2022, 12, 1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattivelli, A.; Zannini, M.; Conte, A.; Tagliazucchi, D. Inhibition of starch hydrolysis during in vitro co-digestion of pasta with phenolic compound-rich vegetable foods. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 104586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, M.; Costa, H.S.; Silva, M.A.; Albuquerque, T.G. The health effects of low glycemic index and low glycemic load interventions on prediabetes and type 2 diabetes mellitus: A literature review of RCTs. Nutrients 2023, 15, 5060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, V.; Piccini, C.; Romi, M.; Salusti, P.; Cai, G.; Cantini, C. Pasta enriched with carrot and olive leaf flour retains high levels of accessible bioactives after in vitro digestion. Foods 2023, 12, 3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberatore, M.T.; Dilucia, F.; Rutigliano, M.; Viscecchia, R.; Spano, G.; Capozzi, V.; Bimbo, F.; Di Luccia, A.; la Gatta, B. Polyphenolic characterization, nutritional and microbiological assessment of newly formulated semolina fresh pasta fortified with grape pomace. Food Chem. 2025, 463, 141531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balli, D.; Cecchi, L.; Innocenti, M.; Bellumori, M.; Mulinacci, N. Food by-products valorisation: Grape pomace and olive pomace (pâté) as sources of phenolic compounds and fiber for enrichment of tagliatelle pasta. Food Chem. 2021, 355, 129642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padalino, L.; D’Antuono, I.; Durante, M.; Conte, A.; Cardinali, A.; Linsalata, V.; Mita, G.; Logrieco, A.F.; Del Nobile, M.A. Use of olive oil industrial by-product for pasta enrichment. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buonocore, G.G.; Del Nobile, M.A.; Di Martino, C.; Gambacorta, G.; La Notte, E.; Nicolais, L. Modeling the water transport properties of casein-based edible coating. J. Food Eng. 2003, 60, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ingredient | CTRL [%] | OPP3% [%] | OPP6% [%] | OPP9% [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Durum wheat semolina flour | 71.43 | 65.43 | 59.43 | 53.43 |

| Water | 28.57 | 26.17 | 23.77 | 21.37 |

| OPP | 0 | 3.00 | 6.00 | 9.00 |

| Water to hydrate OPP | 0 | 5.40 | 10.80 | 16.20 |

| Sample | Colour | Odour | Homogeneity | Appearance | Resistance to Breaking | Overall Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTRL | 8.90 ± 0.22 a | 9.00 ± 0.20 a | 9.00 ± 0.00 a | 9.00 ± 0.00 a | 8.90 ± 0.22 a | 9.00 ± 0.00 a |

| OPP3% | 8.50 ± 0.00 a,b | 8.50 ± 0.00 b | 8.25 ± 0.29 b | 8.50 ± 0.00 b | 8.00 ± 0.00 b | 8.25 ± 0.29 b |

| OPP6% | 8.00 ± 0.00 c | 8.13 ± 0.25 c | 6.25 ± 0.29 c | 6.00 ± 0.00 c | 5.75 ± 0.29 c | 6.00 ± 0.00 c |

| OPP9% | 8.25 ± 0.29 c,b | 8.25 ± 0.29 b,c | 5.75 ± 0.29 d | 5.38 ± 0.25 d | 4.50 ± 0.00 d | 4.50 ± 0.00 d |

| Sample | Elasticity | Bulkiness | Colour | Odour | Adhesiveness | Firmness | Sandiness | Taste | Overall Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTRL | 9.00 ± 0.00 a | 9.00 ± 0.00 a | 9.00 ± 0.00 a | 9.00 ± 0.00 a | 9.00 ± 0.00 a | 9.00 ± 0.00 a | 9.00 ± 0.00 a | 9.00 ± 0.00 a | 9.00 ± 0.00 a |

| OPP3% | 8.00 ± 0.00 b | 8.25 ± 0.29 b | 8.50 ± 0.00 b | 8.50 ± 0.00 b | 8.13 ± 0.00 b | 8.25 ± 0.29 b | 7.88 ± 0.25 b | 8.00 ± 0.00 b | 7.88 ± 0.25 b |

| OPP6% | 7.38 ± 0.25 c | 7.38 ± 0.25 c | 8.13 ± 0.25 c | 8.50 ± 0.00 b | 8.13 ± 0.25 b | 8.13 ± 0.25 b | 6.63 ± 0.25 c | 6.75 ± 0.29 c | 6.75 ± 0.29 c |

| OPP9% | 4.88 ± 0.25 d | 5.00 ± 0.00 d | 8.13 ± 0.25 c | 8.50 ± 0.00 b | 5.50 ± 0.00 c | 4.88 ± 0.25 c | 4.38 ± 0.25 d | 4.00 ± 0.00 d | 4.00 ± 0.00 d |

| Sample | OCT [min] | Swelling Index (g Water/g Dry Pasta) | Water Absorption [%] | Cooking Loss [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTRL | 6:00 | 1.62 ± 0.01 d | 61.74 ± 0.94 b | 1.54 ± 0.10 a |

| OPP3% | 5:30 | 1.78 ± 0.02 c | 62.32 ± 0.81 ab | 1.82 ± 0.73 a |

| OPP6% | 3:30 | 1.90 ± 0.00 b | 63.67 ± 0.99 ab | 2.24 ± 0.61 a |

| OPP9% | 1:00 | 2.03 ± 0.05 a | 64.95 ± 1.09 a | 2.55 ± 0.48 a |

| Total Polyphenols (mg GAE g−1 dw) | FRAP (μmol Fe2+ g−1 dw) | ABTS (μmol TE g−1 dw) | TDF (g/100 g) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Durum wheat semolina | 1.56 ± 0.03 b | 1.49 ± 0.09 b | 1.19 ± 0.05 b | 4.60 ± 0.27 b | |

| OPP | 100.96 ± 1.93 a | 481.72 ± 6.17 a | 192.88 ± 5.24 a | 67.8 ± 3.90 a | |

| Powder Samples | Total Polyphenols (mg GAE g−1 dw) | FRAP (μmol Fe2+ g−1 dw) | ABTS (μmol TE g−1 dw) | TDF (g/100 g) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| raw | cooked | raw | cooked | raw | cooked | raw | cooked | |

| CTRL | 1.50 ± 0.22 dB | 0.62 ± 0.01 dA | 1.10 ± 0.14 dA | 1.19 ± 0.02 dB | 1.45 ± 0.31 dA | 2.36 ± 0.16 dB | 4.60 ± 0.27 cA | 2.20 ± 0.14 dB |

| OPP3% | 4.34 ± 0.24 cB | 3.79 ± 0.12 cA | 22.03 ± 1.21 cA | 27.84 ± 0.44 cB | 7.32 ± 0.70 cA | 10.27 ± 0.18 cB | 6.50 ± 0.38 bA | 3.00 ± 0.18 cB |

| OPP6% | 9.48 ± 0.04 bB | 8.04 ± 0.06 bA | 49.22 ± 1.45 bA | 55.49 ± 1.80 bB | 14.06 ± 0.05 bA | 14.73 ± 0.41 bB | 6.60 ± 0.39 bA | 4.10 ± 0.25 bB |

| OPP9% | 13.36 ± 0.18 aB | 11.58 ± 0.12 aA | 70.86 ± 0.60 aA | 71.04 ± 2.03 aA | 19.17 ± 0.08 aA | 19.76 ± 0.22 aB | 9.90 ± 0.58 aA | 5.30 ± 0.31 aB |

| Functional Parameter | |

|---|---|

| TDF | 16.89 |

| FRAP | 14.31 |

| ABTS | 33.21 |

| TPC | 10.75 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pagazzo, A.; Bavaro, A.R.; D’Antuono, I.; Linsalata, V.; Cardinali, A.; Conte, A.; Del Nobile, M.A. A New Approach with Agri-Food By-Products: A Case Study of Fortified Fresh Pasta with Red Onion Peels. Foods 2025, 14, 4101. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234101

Pagazzo A, Bavaro AR, D’Antuono I, Linsalata V, Cardinali A, Conte A, Del Nobile MA. A New Approach with Agri-Food By-Products: A Case Study of Fortified Fresh Pasta with Red Onion Peels. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4101. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234101

Chicago/Turabian StylePagazzo, Alessia, Anna Rita Bavaro, Isabella D’Antuono, Vito Linsalata, Angela Cardinali, Amalia Conte, and Matteo Alessandro Del Nobile. 2025. "A New Approach with Agri-Food By-Products: A Case Study of Fortified Fresh Pasta with Red Onion Peels" Foods 14, no. 23: 4101. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234101

APA StylePagazzo, A., Bavaro, A. R., D’Antuono, I., Linsalata, V., Cardinali, A., Conte, A., & Del Nobile, M. A. (2025). A New Approach with Agri-Food By-Products: A Case Study of Fortified Fresh Pasta with Red Onion Peels. Foods, 14(23), 4101. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234101