Physicochemical Properties and Cross-Cultural Preference for Mushrooms Enriched Third-Generation Potato Snacks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Product Characteristics

2.2. Study Design

2.2.1. Physicochemical Properties of Analyzed Snacks

Basic Chemical Composition

Color

Texture

Antioxidant Capacity In Vitro

Polyphenol Profile

2.2.2. Consumer Study General Procedure

2.2.3. Consumer Test Questionnaires

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physicochemical Characterization of Snacks Used in the Experiment

3.2. Acceptability of the Snacks Used in the Experiment

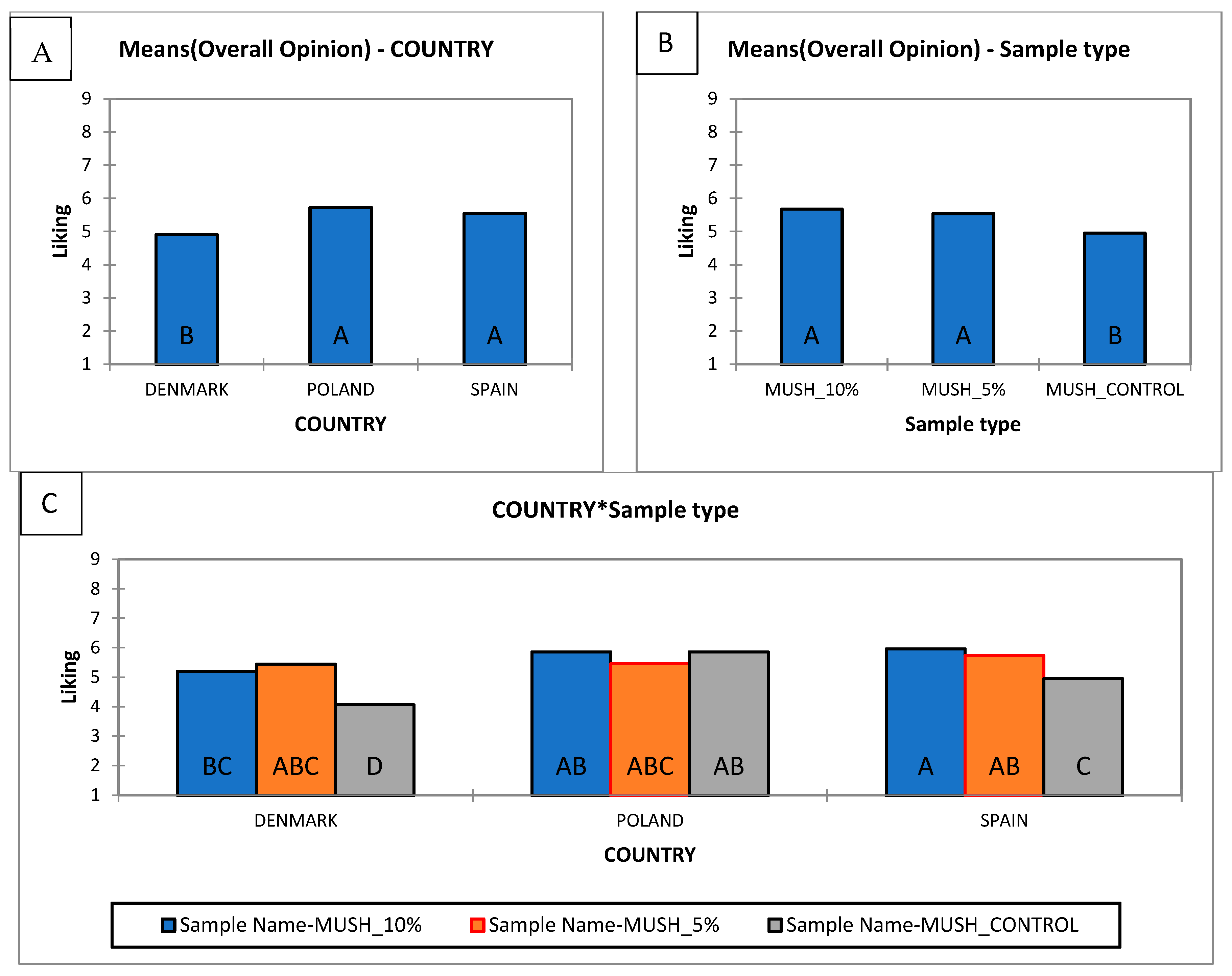

Liking of the Samples

3.3. Consumer Clusters

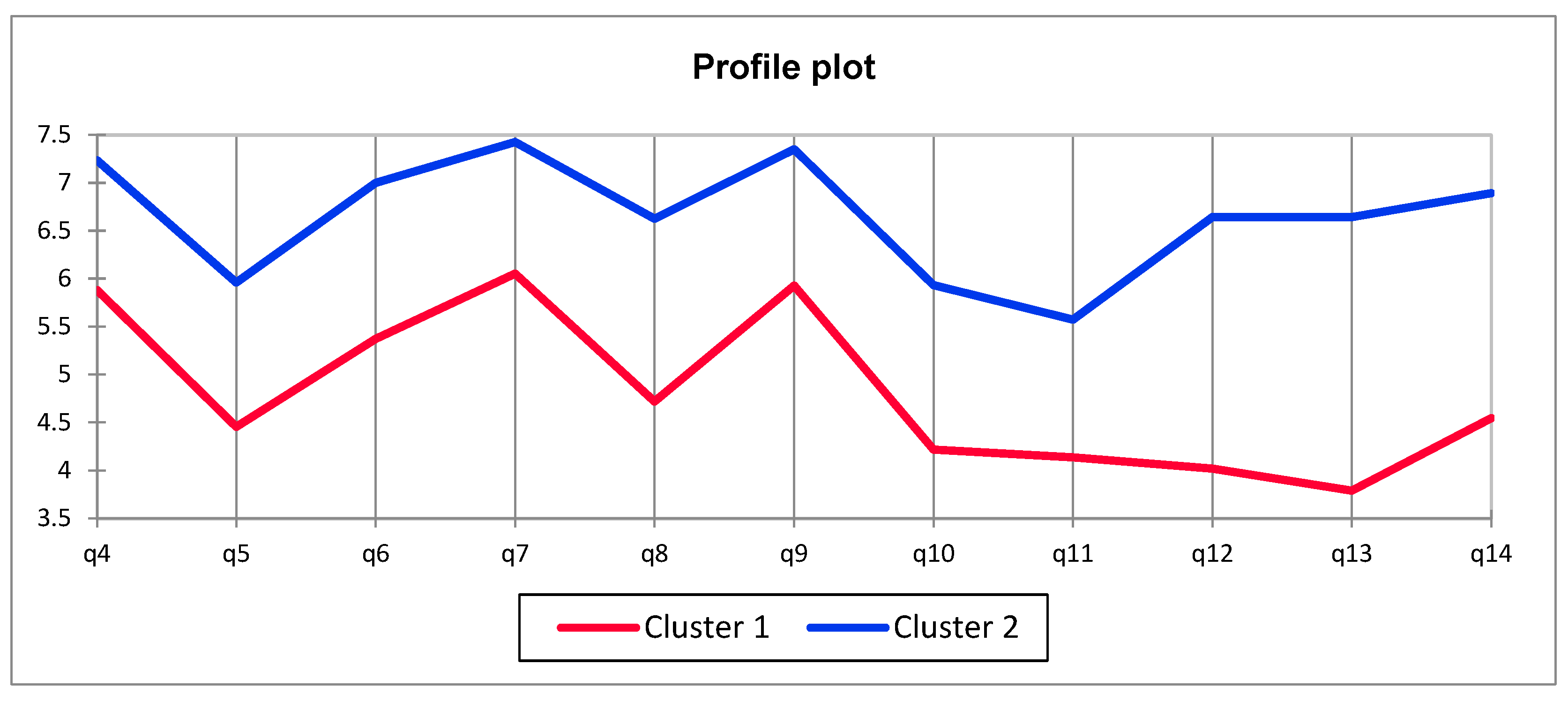

3.3.1. Food Choice

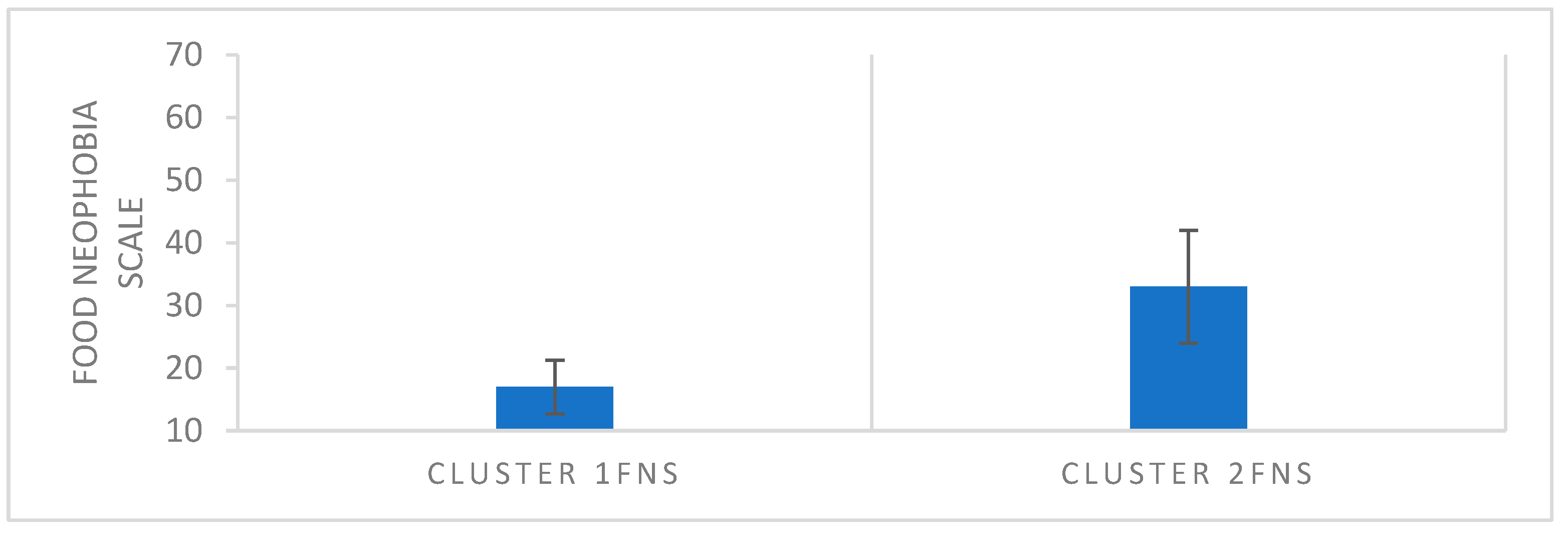

3.3.2. Food Neophobia

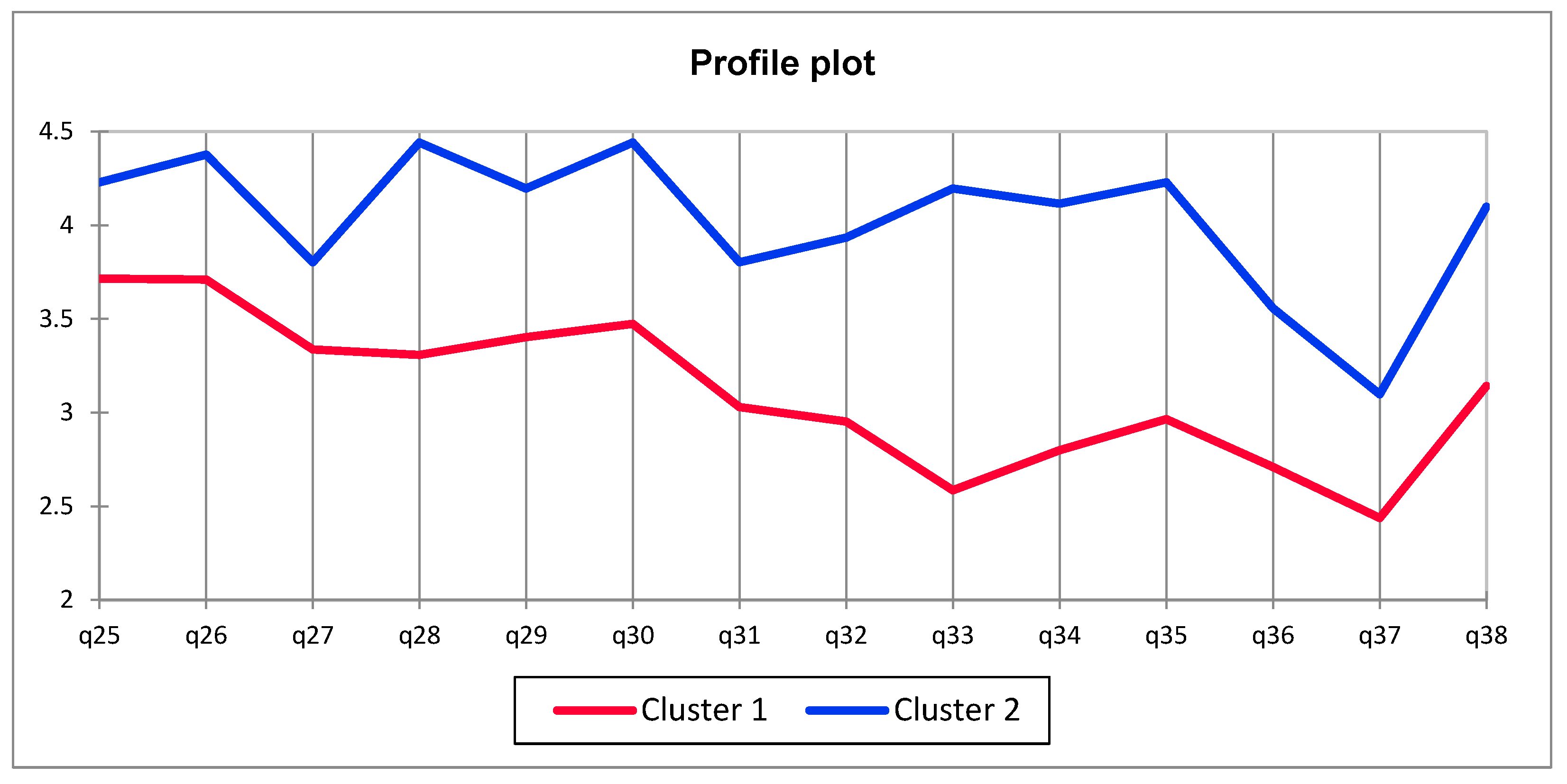

3.3.3. Sustainability Questionnaire

3.3.4. Dietary Habits

3.4. Correlation Between Liking of the Snacks and All Consumers and Products Variables Run per Country

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Type of Questionnaire | Question Number | Behavior | Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food choice questionnaire (FCQ) | Q4 | Healthy | 1 = Not at all important 2= 3= 4 = Neither/nor 5= 6= 7 = Very important |

| Q5 | A way of monitoring my mood | ||

| Q6 | Convenient | ||

| Q7 | Provides me with pleasurable sensations | ||

| Q8 | Natural | ||

| Q9 | Affordable | ||

| Q10 | Helps me control my weight | ||

| Q11 | Familiar | ||

| Q12 | Environmentally friendly | ||

| Q13 | Animal friendly | ||

| Q14 | Fairly traded |

Appendix B

| Type of Questionnaire | Question Number | Statement | Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food Neophobia Scale (FNS) | Q15 | “I am constantly sampling new and different foods” Reversed item | 1 = Strongly disagree 2= 3= 4 = Neither agree/nor disagree 5= 6= 7 = Strongly agree |

| Q16 | “I don’t trust new food” | ||

| Q17 | “If I don’t know what is in a food, I won’t try it” | ||

| Q18 | “I like food form different cultures.” Reversed item | ||

| Q19 | “Food from other cultures looks too weird to eat.” | ||

| Q20 | “At social gatherings, I will try a new food” Reversed item | ||

| Q21 | “I am afraid to eat food I have never had before” | ||

| Q22 | “I am very particular about the food I will eat” | ||

| Q23 | “I will eat almost anything” Reversed item | ||

| Q24 | “I like going to places serving foods from cultures different to my own” Reversed item |

Appendix C

| Question Number | Statement | Scale | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability Questionnaire (SQ) | Q25 | Recycling | 1 = I am not aware of this issue/I have never paid attention to it 2 = I am aware of this issue but I am not interested in it 3 = I am aware of this issue, I am interested in it, but I haven’t done anything for it 4 = I am interested in this issue and I have done something for it 5 = I am interested in this issue and I have taken a significant action |

| Q26 | Respect of the environment | ||

| Q27 | Enhancing renewable/alternative energies | ||

| Q28 | Enhancement of local production | ||

| Q29 | Preserving natural resources | ||

| Q30 | Supporting local economy | ||

| Q31 | Enhancement of free-preservatives food products | ||

| Q32 | Enhancing sustainable production labels (i.e., ecolabels) | ||

| Q33 | Enhancement of non-industrial farming | ||

| Q34 | Enhancement of organic cultivation | ||

| Q35 | Promoting environmental sustainable production | ||

| Q36 | Contrasting the new developing countries exploitation | ||

| Q37 | Contrasting GMO’s food | ||

| Q38 | Promoting workers’ rights |

Appendix D

| Number of Question | Options | |

|---|---|---|

| Dietary habits (DH) | Q39 | 1 = I regularly eat red meat, fish and chicken |

| 2 = I consciously reduce meat intake, but eating meat now and then | ||

| 3 = I don’t eat red meat, but I eat fish, chicken and other poultry | ||

| 4 = I don’t eat red meat nor chicken, but I eat fish and shellfish | ||

| 5 = I don’t eat meat or fish, but I eat eggs and dairy products | ||

| 6 = I don’t eat meat, fish or eggs, but I eat dairy products | ||

| 7 = I don’t eat meat, fish or dairy products, but I eat eggs | ||

| 8 = I don’t eat meat and I don’t use products of animal origin | ||

| 9 = I eat organic and locally grown foods, with a great overlap with foods consumed in a vegetarian diet, yet also including some kinds of meat |

References

- Romeo-Arroyo, E.; Mora, M.; Urkiaga, O.; Pazos, N.; El-Gyar, N.; Gaspar, R.; Pistolese, S.; Beaino, A.; Grosso, G.; Busó, P.; et al. Co-Creating Snacks: A Cross-Cultural Study with Mediterranean Children Within the DELICIOUS Project. Foods 2025, 14, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boa, E. Wild Edible Fungi: A Global Overview of Their Use and Importance to People; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrashekar, J.; Hoon, M.; Ryba, N.; Zuker, C.S. The receptors and cells for mammalian taste. Nature 2006, 444, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagiannaki, K.; Ritz, C.; Jensen, L.G.H.; Tørsleff, E.H.; Møller, P.; Hausner, H.; Olsen, A. Optimising Repeated Exposure: Determining Optimal Exposure Frequency for Introducing a Novel Vegetable among Children. Foods 2021, 10, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.theculturefactor.com/ (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Pliner, P.; Hobden, K. Development of a scale to measure the trait of food neophobia. Appetite 1992, 19, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogari, G.; Menozzi, D.; Mora, C. The food neophobia scale and young adults’ intention to eatinsect products. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2019, 43, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verneau, F.; Amato, M.; La Barbera, F. Edible Insects and Global Food Security. Insects 2021, 12, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, C.S.; Bonwick, G. Ensuring the future of functional foods. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 54, 1467–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J. A Pilot Study on RTE Food Purchasing and Food-Related Behaviors of College Students in an Urbanized Area. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maoto, M.M.; Beswa, D.; Jideani, A.I.O. Watermelon as a potential fruit snack. Int. J. Food Prop. 2019, 22, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization Statistical (FAOSTAT). 2021. FAOSTAT-Data-Crops Visualized-Mushrooms and Truffles. Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC/visualize (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- El Sheikha, A.F.; Hu, D.M. How to trace the geographic origin of mushrooms? Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 78, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, S.; Jiao, S.S.; Zhang, Z.T.; Jing, P. Impact of post-harvest processing or thermal dehydration on physiochemical, nutritional and sensory quality of shiitake mushrooms. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 2560–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, M.; Singh, G. Effect of different pretreatments on the quality of mushrooms during solar drying. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 50, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, F.; Du, B.; Bian, Z.; Xu, B. Beta-glucans from edible and medicinal mushrooms: Characteristics, physicochemical and biological activities. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2015, 41, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; He, H.; Wang, Q.; Yang, X.; Jiang, S.; Wang, D. A Review of Development and Utilization for Edible Fungal Polysaccharides: Extraction, Chemical Characteristics, and Bioactivities. Polymers 2022, 14, 4454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawarathne, I.Y.; Daranagama, D.A. Bioremediation and sustainable mushroom cultivation: Harnessing the lignocellulolytic power of Pleurotus species on waste substrates. N. Z. J. Bot. 2024, 63, 1733–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marçal, S.; Sousa, A.S.; Taofiq, O.; Antunes, F.; Morais, A.M.M.B.; Freitas, A.C.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Pintado, M. Impact of postharvest preservation methods on nutritional value and bioactive properties of mushrooms. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 110, 418–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT. 2025. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#search/mushrooms (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Sharma, V.; Singh, P.; Singh, A. Shelf-life extension of fresh mushrooms: Fromconventional practices to novel technologies—Acomprehensive review. Future Postharvest Food 2024, 1, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangeeta Sharma, D.; Ramniwas, S.; Mugabi, R.; Uddin, J.; Nayik, G.A. Revolutionizing Mushroom Processing: Innovative Techniques and Technologies. Food Chem. X 2024, 23, 101774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemś, A.; Pęksa, A. Polyphenols of coloured-flesh potatoes as native antioxidants in stored fried snacks. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 97, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists. Official Methods of Analysis; AOAC: Rockville, MD, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mariotti, F.; Tomé, D.; Mirand, P.P. Converting nitrogen into protein—Beyond 6.25 and Jones’ factors. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2008, 48, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, H. A colorimetric estimation of reducing sugars in potatoes with 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid. Potato Res. 1973, 16, 176–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemś, A.; Kita, A.; Sokół-Łętowska, A.; Kucharska, A. Influence of blanching medium on the quality of crisps from red- and purple-fleshed potatoes. J. Food Process Preserv. 2020, 44, e14937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, A.K.; Stach, M.; Kucharska, A.Z.; Sokół-Łętowska, A.; Szumny, A.; Moreira, H.; Szyjka, A.; Barg, E.; Kolniak-Ostek, J. Comparison of polyphenol and volatile compounds and in vitro antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic, anti-ageing, and anticancer activities of dry tea leaves. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 222, 117632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongstad, S.; Giacalone, D. Consumer Perception Of Salt-Reduced Potato Chips: Sensory Strategies, Effect Of Labeling, And Individual Health Orientation. Food Qual. Pref. 2020, 8, 103856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Reinders, M.J.; Verain, M.C.D.; Snoek, H.M. The development of a single-item Food Choice Questionnaire. Food Qual. Pref. 2019, 71, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flight, I.; Leppard, P.; Cox, D.N. Food neophobia and associations with cultural diversity and socio-economic status amongst rural and urban Australian adolescents. Appetite 2003, 41, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Backer, C.J.; Hudders, L. Meat morals: Relationship between meat consumption consumer attitudes towards human and animal welfare and moral behawior. Meat Sci. 2015, 99, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laureati, M.; Jabes, D.; Russo, V.; Pagliarini, E. Sustainability and organic production: How information influences consumer’s expectation and preference for yogurt. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 30, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szydłowska-Tutaj, M.; Złotek, U.; Combrzyński, M. Influence of addition of mushroom powder to semolina on proximate composition, physicochemical properties and some safety parameters of material for pasta production. LWT 2021, 151, 112235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Yu, X.; Badwal, T.S.; Xu, B. Comparative studies on phenolic profiles and antioxidant capacities of extracts from edible mushrooms. Food Res. Int. 2016, 89, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalska, A.; Sierocka, M.; Drzewiecka, B.; Świeca, M. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Mushroom-Based Food Additives and Food Fortified with Them—Current Status and Future Perspectives. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallardo, M.A.; Vieira Júnior, W.G.; Martínez-Navarro, M.E.; Álvarez-Ortí, M.; Zied, D.C.; Pardo, J.E. Impact of Button Mushroom Stem Residue as a Functional Ingredient for Improving Nutritional Characteristics of Pizza Dough. Molecules 2024, 29, 5140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, F. Characterization of different mushrooms powder and its application in bakery products: A review. Int. J. Food Prop. 2019, 22, 1375–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, R.; Amini Sarteshnizi, R.; Hosseini, S.M. Effect of partial replacement of wheat flour with mushroom powder on the quality characteristics of bread: Nutritional, textural, and sensory evaluation. Foods 2023, 12, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, F.; Helm, C.V.; Bellettini, M.B.; Maciel, G.M.; Isidoro Haminiuk, C.W. Edible mushrooms: A potential source of essential amino acids, glucans and minerals. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 52, 2382–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicklaus, S.; Schwartz, C.; Monnery-Patris, S.; Issanchou, S. Early Development of Taste and Flavor Preferences and Consequences on Eating Behavior. Nestle Nutr. Inst. Workshop Ser. 2019, 91, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalinik, M.; Pawłowicz, T.; Borowik, P.; Oszako, T. Mushroom Picking as a Special Form of Recreation and Tourism in Woodland Areas—A Case Study of Poland. Forests 2024, 15, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommonaro, G.; Morelli, C.F.; Rabuffetti, M.; Nicolaus, B.; De Prisco, R.; Iodice, C.; Speranza, G. Determination of flavor-potentiating compounds in different Italian tomato varieties. J. Food Biochem. 2021, 45, e13736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FoodNavigator-USA. Plant-Based Products: How Mediterranean Umami Enables Salt Reduction and Flavor Enhancement. 2023. Available online: https://www.foodnavigator-usa.com/News/Promotional-features/Plant-based-products-How-Mediterranean-Umami-enables-salt-reduction-and-flavor-enhancement/ (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Sundqvist, J.; Marshall, M. New Nordic Cuisine in practice: Storage and preservation practices as a means for a resilient restaurant sector. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2025, 40, 101193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poojary, M.M.; Orlien, V.; Passamonti, P.; Olsen, K. Enzyme-assisted extraction enhancing the umami taste amino acids recovery from several cultivated mushrooms. Food Chem. 2017, 234, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szelągowska, G. Grzyby w polskiej tradycji kulinarnej. Studia i Materiały Ośrodka Kultury Leśnej 2017, 16, 213–225. [Google Scholar]

- Contato, A.; Conte Junior, C. Mushrooms in innovative food products: Challenges and potential opportunities as meat substitutes, snacks and functional beverages. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2025, 156, 104868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, J.; Young, O.; Zhang, S.; Cummings, T. Effects of added “flavour principles” on liking and familiarity of a sheepmeat product: A comparison of Singaporean and New Zealand consumers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2004, 15, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barska, A.; Wojciechowska-Solis, J. Traditional and regional food as seen by consumers—research results: The case of Poland. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 1994–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- el Campo, C.; Bouzas, C.; Monserrat-Mesquida, M.; Tur, J.A. Food Neophobias in Spanish Adults with Overweight or Obesity by Sex: Their Association with Sociodemographic Factors and the Most Prevalent Chronic Diseases. Foods 2024, 13, 2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jezewska-Zychowicz, M.; Plichta, M.; Drywień, M.E.; Hamulka, J. Food Neophobia among Adults: Differences in Dietary Patterns, Food Choice Motives, and Food Labels Reading in Poles. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Special Eurobarometer, Climate Change; Eurobarometer Report, Febryary–March 2025; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contato, A.G.; Inácio, F.D.; Bueno, P.S.A.; Nolli, M.M.; Janeiro, V.; Peralta, R.; de Souza, C.G.M. Pleurotus pulmonarius: A protease-producing white rot fungus in lignocellulosic residues. Int. J. Microbiol. 2023, 26, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhao, R.L. A review on nutritional advantages of edible mushrooms and its industrialization development situation in protein meat analogues. J. Future Foods. 2023, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorr, E.; Koegler, M.; Benoît, G.; Christine, A. Life cycle assessment of a circular, urban mushroom farm. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 288, 125668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/veganism-by-country (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Available online: https://proveg.org/data/ (accessed on 8 January 2025).

| Physico-Chemical Properties | Consumer Study | |

|---|---|---|

| Basic chemical composition | Dry matter [%] | Acceptability of the snacks (9-pt hedonic scale) |

| Total proteins [%] | Food choice (Appendix A) | |

| Fat [%] | Food neophobia (Appendix B) | |

| Ash [%] | Sustainability Questionnaire (Appendix C) | |

| Total sugars [%] | Dietary habits (Appendix D) | |

| Raw fiber [%] | ||

| Salt [%] | ||

| Bioactive compounds | Total flavanols HPLC [mg/kg] | |

| Total phenolic acids HPLC [mg/kg] | ||

| Total polyphenols HPLC [mg/kg] | ||

| Antioxidant capacity | TEAC ABTS [µmol TE/g] | |

| TEAC DPPH [µmol TE/g] | ||

| TEAC FRAP [µmol TE/g] | ||

| Color parameters | L* | |

| a* | ||

| b* | ||

| C | ||

| h° | ||

| Texture [N] | ||

| Parameter | Control Sample | Mushrooms 5% | Mushrooms 10% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dry matter [%] | 96.06 ± 0.11 c | 96.50 ± 0.08 b | 97.07 ± 0.08 a |

| Total proteins [%] | 3.13 ± 0.10 c | 3.95 ± 0.08 b | 4.56 ± 0.08 a |

| Fat [%] | 17.78 ± 0.16 c | 23.93 ± 0.08 a | 22.80 ± 0.17 b |

| Ash [%] | 1.13 ± 0.11 c | 1.70 ± 0.05 b | 1.97 ± 0.11 a |

| Total sugars [%] | 1.40 ± 0.03 a | 0.61 ± 0.11 b | 0.66 ± 0.04 b |

| Raw fiber [%] | 1.33 ± 0.16 c | 1.86 ± 0.11 b | 2.02 ± 0.07 a |

| Salt [%] | 1.40 ± 0.12 a | 1.55 ± 0.08 a | 1.40 ± 0.13 a |

| Total flavanols HPLC [mg/kg] | 0.75 ± 0.01 c | 3.23 ± 0.02 b | 8.45 ± 0.04 a |

| Total phenolic acids HPLC [mg/kg] | 26.25 ± 0.33 c | 77.32 ± 0.99 b | 126.30 ± 0.95 a |

| Total polyphenols HPLC [mg/kg] | 26.99 ± 0.34 c | 81.02 ± 1.03 b | 135.75 ± 0.94 a |

| TEAC ABTS [µmol TE/g] | 0.49 ± 0.01 c | 1.01 ± 0.00 b | 1.53 ± 0.01 a |

| TEAC DPPH [µmol TE/g] | 0.45 ± 0.03 c | 0.64 ± 0.03 b | 0.72 ± 0.04 a |

| TEAC FRAP [µmol TE/g] | 0.24 ± 0.01 c | 0.74 ± 0.02 b | 1.21 ± 0.04 a |

| Parameter | Control Sample | Mushrooms 5% | Mushrooms 10% |

|---|---|---|---|

| L* | 85.58 ± 0.26 a | 63.40 ± 0.48 b | 55.73 ± 0.37 c |

| a* | 0.96 ± 0.11 c | 4.17 ± 0.04 b | 5.28 ± 0.04 a |

| b* | 19.51 ± 0.24 a | 18.78 ± 0.09 a | 18.84 ± 0.15 a |

| C | 19.54 ± 0.25 a | 19.24 ± 0.10 a | 19.57 ± 0.15 a |

| h° | 87.18 ± 0.33 a | 77.47 ± 0.08 b | 74.36 ± 0.10 c |

| Texture [N] | 33.34 ± 5.59 a | 22.34 ± 5.42 b | 21.13 ± 5.15 b |

| Cluster | Cluster Description | Cluster Share | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poland | Denmark | Spain | Poland | Denmark | Spain | ||

| % | |||||||

| Cluster 1FCQ | Consumers who place more importance on all aspects of food choice | 65.4 | 51.9 | 24.7 | 0.000 * | 0.406 | <0.0001 * |

| Cluster 2FCQ | Consumers who place less importance on all aspects of food choice | 34.6 | 48.1 | 75.3 | 0.000 * | 0.406 | <0.0001 * |

| Cluster | Cluster Description | Cluster Share | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poland | Denmark | Spain | Poland | Denmark | Spain | ||

| % | |||||||

| Cluster 1FNS | Neophilic consumers | 42.3 | 44.3 | 21.9 | 0.197 | 0.085 | 0.002 * |

| Cluster 2FNS | Neophobic consumers | 57.7 | 53.7 | 78.1 | 0.197 | 0.085 | 0.002 * |

| Cluster | Cluster Description | Cluster share | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poland | Denmark | Spain | Poland | Denmark | Spain | ||

| % | |||||||

| Cluster 1SQ | Consumers are less engaged with environmental actions. | 69.2 | 83.5 | 67.1 | 0.344 | 0.012 * | 0.150 |

| Cluster 2SQ | Consumers are more engaged with environmental actions | 30.8 | 16.5 | 32.9 | 0.344 | 0.012 * | 0.150 |

| Cluster | Cluster Description | Cluster Share | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poland | Denmark | Spain | Poland | Denmark | Spain | ||

| % | |||||||

| Cluster 1DH | Consumers who limit meat and meat products in their diet (flexitarians) | 25.6 | 29.1 | 27.4 | 0.755 | 0.756 | 1.000 |

| Cluster 2DH | Consumers who are eating everything (omnivores) | 41.0 | 54.4 | 52.0 | 0.095 | 0.268 | 0.573 |

| Cluster 3DH | Consumers who do not eat red meat but eat fish, poultry, and shellfish (semi-vegetarians) | 21.8 | 5.1 | 12.3 | 0.007 * | 0.012 * | 1.000 |

| Cluster 4DH | Half-vegetarians like pescatarians or lactoovovegetarians | 10.3 | 8.9 | 6.9 | 0.623 | 1.000 | 0.619 |

| Cluster 5DH | Vegans | 1.3 | 2.5 | 1.4 | 1.000 | 0.609 | 1.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nemś, A.; Mora, M.; Rune, C.J.B.; Giacalone, D.; Noguera Artiaga, L.; Carbonell-Barrachina, A.A.; Kolniak-Ostek, J.; Michalska-Ciechanowska, A.; Kita, A. Physicochemical Properties and Cross-Cultural Preference for Mushrooms Enriched Third-Generation Potato Snacks. Foods 2025, 14, 4103. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234103

Nemś A, Mora M, Rune CJB, Giacalone D, Noguera Artiaga L, Carbonell-Barrachina AA, Kolniak-Ostek J, Michalska-Ciechanowska A, Kita A. Physicochemical Properties and Cross-Cultural Preference for Mushrooms Enriched Third-Generation Potato Snacks. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4103. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234103

Chicago/Turabian StyleNemś, Agnieszka, Maria Mora, Christina J. Birke Rune, Davide Giacalone, Luis Noguera Artiaga, Angel A. Carbonell-Barrachina, Joanna Kolniak-Ostek, Anna Michalska-Ciechanowska, and Agnieszka Kita. 2025. "Physicochemical Properties and Cross-Cultural Preference for Mushrooms Enriched Third-Generation Potato Snacks" Foods 14, no. 23: 4103. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234103

APA StyleNemś, A., Mora, M., Rune, C. J. B., Giacalone, D., Noguera Artiaga, L., Carbonell-Barrachina, A. A., Kolniak-Ostek, J., Michalska-Ciechanowska, A., & Kita, A. (2025). Physicochemical Properties and Cross-Cultural Preference for Mushrooms Enriched Third-Generation Potato Snacks. Foods, 14(23), 4103. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234103