Abstract

Background: Increasing research into probiotics is showing potential benefits for health in general and mental health in particular. Kombucha is a recent beverage and can be considered a probiotic drink, but little is known about its effects on physical and mental health. This product is experiencing growth in the market; however, there are no scientific results to support its potential for physical and mental health. Aim: This review article aims to draw attention to this issue and to highlight the lack of studies in this area. Key findings and conclusions: The lack of legislation for the correct marketing of this product may also constrain clinical studies. However, clinical studies are of utmost importance for an in-depth understanding of the effects of this product on the human body. More research is needed, not only to better understand the impact of Kombucha on the human body, but also to ensure the application of regulatory guidelines for its production and marketing and enable its safe and effective consumption.

1. Introduction

Nowadays people are increasingly concerned about their own health. People want to become healthier, and the adoption of healthier lifestyles is necessary to improve quality of life and to reduce the numerous pathologies and comorbidities associated with nutrient inadequacy or poor diet choices [1]. People are concerned about their body, their mind and their health, and so their search for healthy foods or specific foods that improve health, such as functional foods, has been increasing [2,3,4]. Functional foods have been linked to improved health and greater quality of life. These products are defined as dietary products (processed or natural foods) that when consumed regularly in a balanced and diversified diet, improve both the mental and physical state of health and/or reduce the risk of disease [5,6]. These functional foods can be classified from the product point of view as follows: fortified (with additional nutrients), enriched (new nutrients or components), altered (substance(s) replacement by other(s) with beneficial effects), and/or enhanced products (new feed composition, genetic manipulation) [5]. Thus, in addition to their nutritional value as conventional foods, these foods present potential to enhance health and can reduce the risk of developing non-communicable diseases, such as cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and mental illnesses [7]. Although there is not yet a worldwide acceptable definition for functional foods, a definition that may become integrative is that of the Functional Food Centre (FFC). The FFC defines functional food as ‘natural or processed foods that contain known or unknown biologically-active compounds which, in defined, effective, and non-toxic amounts, provide a clinically proven and documented health benefit for the prevention, management or treatment of a chronic disease’ [8].

According to the literature, some of the main components of functional foods are polyunsaturated fatty acids, probiotics/prebiotics/synbiotics, and antioxidants [6]. The current research highlights the role of probiotics in functional foods and their impacts on mental health. The development of functional foods and beverages with probiotics has shown a marked increase over the last years, and the consumer and market demand for these products is increasing all over the world [9]. According to Fortune Business Insights the global market was valued at USD 48 billion in 2019 and it is projected to reach USD 94 billion by 2027 [10]. Probiotics have been in the spotlight lately mainly due to their impact on the modulation of the gut microbiota and to other irrefutable health benefits, such as neurological and immunological effects [11,12]. Currently, it is known that physical and mental health are controlled by the brain and one’s environment, but recent discoveries have placed a special role on the gut microbiota [13,14]. Recent findings show that there is a relation between what we consume and our mental health, more precisely, between the brain and the gut [13], which means that both emotional and behavioral processing are affected not only by the brain and the environment, but also by the gut microbiota [13,15].

The consumption of probiotics is increasing, and there is a great diversity of probiotic products on the market [11,12]. These products are displayed in several forms such as supplements (e.g., powder, capsules), food (e.g., yoghurts, cheese, butter, soy products, fermented vegetables, processed food, among others), and beverages [16].

1.1. The Kombucha Beverage

One popular beverage that has been gaining visibility is Kombucha. Kombucha is a traditional Chinese beverage made of sweetened tea (mainly black or green; however, other variants of tea and also other ingredients, such as cereals, milk, and even mushrooms, may be used) fermented by a specific combination of probiotic microorganisms. Kombucha mainly comprises tea polyphenols, amino acids, vitamins, minerals, organic acids, sugars, and probiotic microorganisms. This is a functional beverage that has a high amount of plant extracts and metabolites resulting from the metabolism of the symbiotic culture of bacteria (mainly Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species) and yeasts (mainly Saccharomyces species), known as SCOBY, [17,18]. According to the literature, Kombucha has been shown to have physiological benefits, such as anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antioxidant activities, alongside other properties. Consequently, it qualifies as a functional beverage [19,20,21] (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Composition and properties of Kombucha beverage.

Kombucha is very rich in various bioactive compounds, including acetic and gluconic acid, complex B vitamins, minerals, amino acids, and polyphenols, that have been recognized as having health benefits, such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antidiabetic, and antimicrobial activity [22]. Different studies have shown that the type and amount of these bioactive compounds are associated not only with the properties of the black or green tea used (other materials can also be used, such as cereals, milk, and even mushrooms) but also with the fermentation conditions, namely, the type of microorganisms and their interactions, time and temperature [22,23].

The literature reports the impact of the biological properties of Kombucha on health and several disorders, such as inflammatory diseases, arthritis, allergies, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer [24]. Some studies highlight that Kombucha’s composition impacts hypocholesterolemic activity, as well as anti-hypertensive and antidiabetic activities, by inhibiting the enzymes angiotensin-converting enzyme, α-amylase and β-glucosidase, respectively [24].

On the other hand, some studies have correlated the consumption of probiotics with reductions in anxiety and depression [25,26,27], and a positive impact on cognitive and emotional functions [28]. However, it is not well established how its consumption can affect the human “psyche”. It is known that probiotics modulate the intestinal microbiota which subsequently influence brain responses, such as neurotransmitter biosynthesis and the emotional state, through the gut–brain axis [29].

Thus, the present review focuses on the role of probiotic Kombucha in mental health and associated diseases and intends to draw attention to this thematic, summarizing the latest publications in this field and aiming to understand its potential impact on health.

1.2. Mental Health via Gut–Brain Axis

The literature contains increasing evidence that corroborates the mutual influence between the brain and the gut microbiota [25,30]. The gut microbiota–brain axis is a bidirectional structure that connects these two organic systems and has effects on the modulation of human organic and psychological functions [30]. For example, substances released by the gut microbiota can reach the brain via the circulatory pathway. On the other hand, the brain may also be influencing the gut microbiota by neuronal and endocrine pathways. The literature reports that this communication occurs through three main pathways: the autonomic nervous system (including the enteric nervous system and vagus nerve), immune system and neuroendocrine system [14,31,32].

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) is a neural network that comprises the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems. This network in connection with hypothalamic-pituitary–adrenal axis establishes the communication between the brain and the gut [14]. The ANS is responsible for controlling physiological homeostasis without conscious effort, namely the gastrointestinal function. The ANS in connection with neuronal (e.g., vagus nerve) and neuroendocrine signaling can induce changes in the gastrointestinal autonomic activation, which can be triggered by interoceptive afferent feedback or by cognitive and emotional efferent modulation [14,32,33]. On the other hand, the ANS controls several gastrointestinal functions, such as gut permeability, fluids production, and the mucosal immune response, and it can be modulated by gut microbiota metabolites like short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and lipopolysaccharides [14,32]. Therefore, the ANS provides the gut with the most direct neurological response available; however, the intestinal microbiota can interact with gut ANS synapses, by microbiota-derived neuromodulatory metabolites (e.g., serotonin (SER), gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), catecholamines). This process explains the microbiota–gut–brain axis bidirectional communication. Thus, changes in the gut microbiota can influence brain functions (e.g., cognitive, memory, emotion, decision-making) and behaviors (e.g., mood) [14,32,34].

The role of the immune system’s pathway role in gut–brain signaling is growing [35]. It is known that neuroinflammation increases the odds of developing psychiatric disorders, such as autism spectrum disorders, epilepsy, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and cerebrovascular diseases [14,35,36]. The literature reports that various gut metabolites, including SCFAs (e.g., butyrate, propionate, acetate), bacteriocins and neuromodulators (e.g., glutamate), seem to activate the immune system and so affect and regulate cytokine secretion and microglial activation [14]. Thereby, cytokines, neurotransmitters, neuropeptides, SCFAs and other microbiota metabolites can pass through the blood and lymphatic systems and be in constant communication with both the brain and the gut [14,32,37].

Finally, the other most studied pathway in this axis communication is the neuroendocrine pathway. As with the immune system, gut metabolites can enter into the systemic circulation, activate the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, and modify the secretion of gut hormones and neurotransmitters, and consequently regulate body metabolism functions [14,33]. The literature shows that homeostatic deregulation can be caused by mental disorders, such as stress, anxiety, or depression [35]. For example, in stress disorders, there is a release of the adrenocorticotrophic hormone by the pituitary gland and cortisol by the adrenal cortex, which seems to be associated with the neuroimmune response and cytokine release, leading to an increase in gastrointestinal permeability [14,38,39].

Such a complex mechanism that involves not only internal but also external factors, such as stress, diet, exercise, and the environment, has interested researchers and, in consequence, much research has been conducted to understand these interactions [38].

1.3. Probiotics/Kombucha Impact on Mental Health

As mentioned above, probiotics are functional components. According to the World Health Organization (2001), probiotics are live microorganisms that when incorporated into the daily diet in adequate amounts, confer physical and mental health benefits on the host [40,41]. Their therapeutic potential has been explored in several pathologies, such as obesity, cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes, arthritis, and mental disorders. Therefore, the impacts of probiotic products on the gut–brain relation and how altered gut microbiota affects mental illness (e.g., depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia) and its prevention and/or treatment have been studied [28].

Several microorganisms (bacteria and yeasts) have been reported as probiotics, namely, specific probiotic strains of the following genera: Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, Propionibacterium, Peptostreptococcus, Pediococcus, Leuconostoc, Enterococcus, Streptococcus, Bacillus, Bacteroides, Akkermansia, and Saccharomuyces [40,42]. These probiotic strains within the abovementioned genera are known for boosting the immune system and balancing the intestinal microbiota [12] and may act as prevention or therapeutics for cardiovascular diseases and cancer, among others [43]. Specifically in regard to the positive impacts of probiotics on brain disorders (e.g., multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Alzheimer and Parkinson’s disease, autism, stress, and anxiety), the literature reports the potential of several species and strains belonging to the following genera: Actinobacteria, Aelobaculum, Alistipes, Allobaculum, Anaerotruncus, Akkermansia, Bacteroidetes, Bacteroidesfragilis, Bascteroidesvulgatu, Blautia, Bifidobacterium, Bilophila, Butyrivibriofibrisolvens, Collinsella, Clostridium, Coprococcus, Corynebacterium, Desulfovibrio, Dialister, Disulfovibironacease, Dorea Enterobacteriaceae, Faecalibacterium, Firmicutes, Methanobrevibacter, Oscillibacter, Parabacteroidsdistasonis, Parabacteroides, Peptococcus, Prevotellaceae, Proteobacteria, Ralstonia, Rikenellaceae, Roseburia, Ruminococcus, Sutterellaceae, Tenericutes, Veillonella, and Verrucomicrobia [42,44].

The literature suggests that the consumption of these probiotic foods and supplements may enhance cognitive function. With that, the reduction in negative neurologic or neuropsychiatric conditions, such as depression, anxiety, stress related symptoms, emotional deregulation, some neurodegenerative diseases (Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s disease) can even help with antisocial and aberrant behaviors associated with autism disorder [29,45,46,47].

Although the literature reports the advantages of probiotics and probiotic food in mental health, less is known about the role of these foods in the gut–brain relation, their importance in CNS function, and in neurodevelopment. Some animal and human studies have reported that probiotics contribute to neuronal modulations through the release of their metabolites, such as GABA, Serotonin, SCFAs, Glutamate, and others. For example, Hur and collaborators (2022) reported that in their animal study, treatment with probiotics relieved hyperactivation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, which decreased cortisol levels and reduced anxiety and depressive symptoms [34]. The probiotics’ anti-inflammatory effect modulates the proinflammatory cytokines and can potentially decrease depressive symptoms. Probiotics have also been shown to alleviate depressive mood in humans; however, studies in humans are still scarce [34]. Although other animal studies have been conducted [48], further studies, both in animals and humans, are needed to validate the beneficial effects of probiotic supplementation on mental health conditions (depression, anxiety and other brain functions).

One probiotic food that has gained particular attention is Kombucha, and the present review aims to investigate the impacts of this specific product on mental health. Regarding the impact of Kombucha on mental health, several studies have reported the health benefits of this functional beverage, and some of its beneficial properties include antioxidant, anti-inflammatory [19,20], and antimicrobial activities [49], as well as improving immunologic and liver functions, particularly the hepaprotective effect [20,50,51]. Although the literature refers to the possible effects of Kombucha on mental health, there are few studies to support these claims, and hence the need for this review.

2. Methodology

This review intended to analyze the relationship between “Kombucha and mental health”. However, due to the lack of studies in the area, the search was refined and a review on “Kombucha and health” was included to identify information on in vitro, in vivo and human assays. To this end, a systematic search was performed using Pubmed, Science Direct and Web of Science databases from 2 June to 29 July 2023. Several descriptors were used: “Kombucha” AND “health” AND (“in vitro” OR “in vivo” OR “human assays”) (Figure 1). The screening of the articles was conducted by applying the following eligibility criteria:

- (a)

- Inclusion: research articles, clinical assays, publications written in English.

- (b)

- Exclusion: outside the scope of the subject, other types of publications (reviews, comments, editorials, discussions, correspondence, letters, short communications), publications in languages other than English, and studies whose full texts were not available.

This review was conducted using the PRISMA criteria for preferred reporting items within systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) [52,53]. The collected information was compiled and analyzed regarding the year of publication, authors, sample, country, methodology/type of study, results, conclusions, and research aims. The bibliographic references were compiled through the computer program EndNote bibliographic referencing.

3. Results

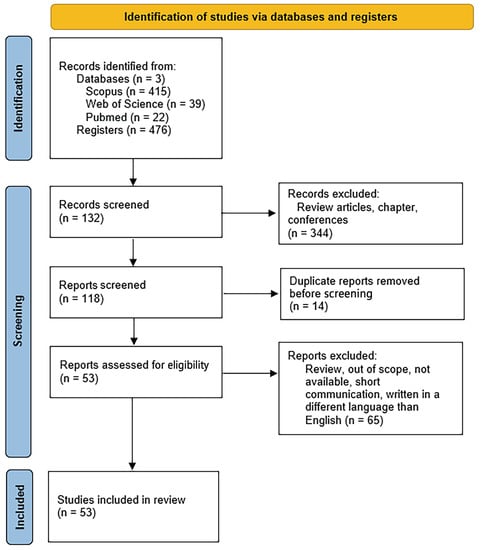

This systematic review identified 476 scientific articles published in international journals indexed to the digital databases used in this search. After screening, duplicate publications and research that fitted the exclusion criteria were removed. Thus, after the eligible criteria were applied, fifty-three publications met the defined inclusion criteria, as shown in the PRISMA flow diagram presented in Figure 2. A summary of the most important characteristics of these articles is presented in Table 1.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram showing research methodology: “Kombucha” AND “mental health” AND (“in vitro” OR “in vivo” OR “human assays”).

Table 1.

Summary information of the studies included from the literature search using the descriptors “Kombucha” and “health”, and “in vitro”, “in vivo” and “human assays”.

It should be noted that no specific studies evaluated the impact of Kombucha on mental health (brain impact, cognitive functions, or brain disorders). Most studies reported the characteristics of the Kombucha beverage, highlighting the physicochemical and biological properties of the product. In vitro and in vivo studies with animal models were included, as well as studies of new products (incorporation of new ingredients) and new processing methods (e.g., fermentation times).

Considering the abovementioned collected data, the lack of clinical assays related to Kombucha is evident (Table 1). Human assays are scarce, and in vivo assays, although they exist, are not yet fully conclusive. Most of the studies that aimed to identify and evaluate the properties of this functional beverage (some studies reported on commercialized Kombucha already in the market and others on Kombucha still in the development process) focused on the physiochemical and biological characterization, using in vitro assays. Based on the analysis of the included studies, it is also worth highlighting the lack of information about the SCOBY used, which is why its inclusion in Table 1 was not justified.

Regarding the studies presented, most of the time, it is difficult to understand the pathology with which they are associated. However, some studies highlight using Kombucha treatments mainly for oncological diseases, diabetes, and cardiac diseases. There is a need for more practical studies about the impact of the consumption of Kombucha on the brain and brain-related diseases.

4. Discussion

This systematic review was designed to provide insights into the impact of Kombucha consumption on health in general, and its effects on mental health or brain disorders, in particular. Due to the appeal of Kombucha among consumers, and its potential higher consumption, together with the lack of evidence about its impact on health, specifically in mental health, careful in-depth study of these products is of utmost importance.

According to our results, it is clear there is an absence of scientific evidence/studies that can confirm the veracity of the commonly misused expression ‘the beneficial impact of Kombucha in mental health’. In consequence, readers should be cautious, not only when accessing online information, but also when it comes to Kombucha consumption.

Despite the ambiguous discussions about Kombucha found in the literature, in the obtained data, and after using several descriptors, we were only able to identify two articles with experimental designs related to this thematic and these articles were without a clear focus. Permatasari and collaborators reported the potential of Kombucha in anti-ageing [71]. However, the authors also emphasizes that evidence is needed for determining the functional potential of Kombucha consumption in humans. On the other hand, in the research works of Barbosa and collaborators [65] and other research teams (see Table 1), study emphasis was placed on the antioxidant potential of Kombucha, highlighting also the need for further studies.

Most of the studies we found in these three credible scientific databases focused on identifying and characterizing the physicochemical and biological properties of this functional beverage. Some in vitro and in vivo studies are presented, although in vivo assays are also few, and they are not yet fully conclusive. Human assays are scarce, and there is an urgent need to better understand the impact of this specific probiotic beverage on health. However, the lack of legislation and regulatory guidelines for the production process may be one reason for the lack of research. The literature has highlighted the beneficial properties of Kombucha, but the clinical evidence is limited, especially in relation to brain disorders.

The literature has reported the role of Kombucha as a possible neuroprotective agent for neurodegenerative diseases and brain damage lesions, mainly due to its antioxidant properties that are responsible for decreases in neural cell death [24,71,106]. In the studies presented in Table 1, there is clear evidence of the antioxidant potential of this functional beverage; however, it is important to transpose these findings to clinical trials. This biological property is of great importance, since the antioxidant activity is at the basis of preventing the development of neurodegenerative diseases and other non-neurological diseases. There are strong arguments and evidence for the possible correlation between this Kombucha activity and reductions in the development of neurodegenerative diseases; nevertheless, this correlation must be tested in order to draw solid conclusions [71].

Furthermore, studies have shown that glutamate, one of the most abundant metabolites in Kombucha, is the most important excitatory neurotransmitters in the brain associated with learning, memory, and neural development [83,107]. Furthermore, glutamate with GABA, effectively reduces the symptomology of anxiety, depression, and bipolar disorders [108,109]. This information helps us to understand not only the therapeutic potential of Kombucha, but also its possible preventive effect against psychiatric and neurological disorders. However, it is quite ambitious and, in fact, misleading to say that there is a cause–effect relation given the lack of studies addressing this question. Therefore, it is of paramount importance to investigate the glutamate role in Kombucha, how it reacts with other Kombucha components and if it really has a significant impact on mental health.

In addition, the anti-inflammatory properties associated with Kombucha must also be better analyzed as there is limited scientific evidence reported by only few studies [66,83,97]. This property is essential to understand neurodegenerative diseases because in these diseases, inflammation is a complex multifactorial process involving the central nervous system.

These beneficial properties of the product are due not only to the substrates used in its composition and other elements (e.g., phenolic compounds, proteins, vitamins, etc.), but also to the composition of the applied SCOBY. The literature vaguely mentions these microorganisms, providing little information on their type and quantity. Most of the articles included in this review did not report this information, and so details about SCOBY were not included in Table 1.

In the literature, one can find several studies about probiotic strains and their impact on mental health. However, the validation of their effects should be extended to specific products. Studies in the literature report how the consumption of probiotic supplements (composed mainly of Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus and Actinobacteria) as part of a therapy can significantly reduce depression symptomatology, improve cognitive functions (e.g., memory and neuroplasticity), and regulate emotional behavior. Nevertheless, it is crucial to assess specific types of probiotics [25,47,110,111,112], as well as particular food matrices, which are sources of these probiotics. Some studies indicate that treatment with probiotic supplements, containing mainly Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, with quantities around 2 × 109 CFU/g, primarily for 8–12 weeks, can significantly reduce Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative disease symptoms as well as elevate the production of serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine and GABA, thereby reducing depression symptomology [113]. A specific study showed that a probiotic treatment consisting of supplementation of 8 × 109 CFU/day over 12 weeks for schizophrenia could reduce the condition’s general symptomology [114,115]. It is obvious that probiotic really do impact our health and reduce the development of certain diseases, specifically neurological ones. Still, given that Kombucha consumption is increasing as a probiotic source, more studies must be performed in order to understand how this beverage can particularly influence the improvement in neurological and psychological conditions and to determine suitable doses to treat different diseases.

Thus, information about SCOBY deserves special attention, especially concerning the creation of regulatory guidelines for the development/production and commercialization of this product to ensure its quality and safety.

Another critical factor that influences Kombucha properties concerns the manufacturing process, namely the fermentation process. This review highlighted some studies that report that the fermentation conditions and time affect the antimicrobial and antioxidant activities and phenolic, flavonoid, and bioactive compounds of Kombucha [54,84,90]. For example, Aung and collaborators showed that using higher fermentation temperatures boosts the microorganism growth, maintains important total flavonoid compounds and enhances the ɑ-amylase inhibitory activity [67].

These characterization studies are extremely important, but there is an urgent need for further studies in humans. These studies are clearly scarce but are urgent because the consumption of this product is increasing. Clinical human assays should seek to understand the mechanism of action of probiotic foods and drinks on brain function, particularly on how this interaction occurs and what results from it in terms of cerebral activity. As Kombucha is one of the probiotic beverages with potential for expansion in the market, the implications of its consumption on the human body must be more deeply investigated [116], particularly its main effects on general health, as well as brain activity. On the other hand, the lack of legislation may be an obstacle to the research into impactful novel properties of this beverage [117]. Thus, more human clinical trials need to be conducted in order to guarantee the efficacy and safety of this product’s production and consumption. Only with clinical studies will it be possible to improve knowledge about this product, clearly understand its benefits, and explore the associated risks, particularly its potential toxicity.

The data reported in this review are intended to draw attention to this issue and its importance. It is extremely important to understand the real impact of Kombucha consumption on health and mental health through clinical trials and to define national and international regulatory guidelines for the production and commercialization of this beverage in order to standardize its consumption and ensure consumer health and safety [117]. The lack of such regulations and artisanal production can compromise the quality and safety of the beverage [116]. This drink involves microbiological complexity, which must be preserved according to specific guidelines.

Some limitations in the present review should be highlighted. Important limitations were the difficulty in selecting the specific descriptors and the lack of studies in the area, especially in mental health, which hampered the review process.

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

The literature has shown a link between the consumption of probiotics and the benefits associated with mental health, although the scientific evidence about the mental health benefits of the Kombucha beverage is not clear.

Even though probiotic supplements may have positive effects on the prevention and treatment of mental disorders, more studies are needed to explore the different probiotic-rich functional products in the market.

This review intended to draw attention to the lack of up-to-date scientific evidence about the health effects of Kombucha, particularly mental health-related benefits. In particular, the neuroprotective effect so often associated with Kombucha needs to be carefully studied and its potential biological activity validated. In addition, to ensure safe consumption, it is of utmost importance to apply regulatory guidelines to its production and marketing. Also, the lack of existing legislation regarding this product may also constrain the execution of clinical trials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.B.; investigation, P.B. and M.R.P.; writing—original draft preparation, P.B., M.R.P., and C.V.-R.; writing—review and editing, P.O.-S. and M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The present publication was supported by CEDH, through the CEECINST/00137/2018 and Project UIDB/04872/2020 of Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT), Portugal.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rochefort, G.; Lapointe, A.; Mercier, A.-P.; Parent, G.; Provencher, V.; Lamarche, B. A Rapid Review of Territorialized Food Systems and Their Impacts on Human Health, Food Security, and the Environment. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addanki, S.; Koti, E.; Juturi, R.K. Nutraceuticals: Health Claims Regulatory Overview. Int. J. Pharm. Res. 2021, 13, 4024–4033. [Google Scholar]

- Chopra, A.S.; Lordan, R.; Horbańczuk, O.K.; Atanasov, A.G.; Chopra, I.; Horbańczuk, J.O.; Jóźwik, A.; Huang, L.; Pirgozliev, V.; Banach, M. The current use and evolving landscape of nutraceuticals. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 175, 106001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Costa, J.P. A current look at nutraceuticals–Key concepts and future prospects. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 62, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarabella, A.; Varese, E.; Buffagni, S. Functional Foods. In Food Products Evolution: Innovation Drivers and Market Trends; Tarabella, A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 117–142. [Google Scholar]

- Granato, D.; Barba, F.J.; Kovačević, D.B.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Cruz, A.G.; Putnik, P. Functional Foods: Product Development, Technological Trends, Efficacy Testing, and Safety. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 11, 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essa, M.M.; Bishir, M.; Bhat, A.; Chidambaram, S.B.; Al-Balushi, B.; Hamdan, H.; Govindarajan, N.; Freidland, R.P.; Qoronfleh, M.W. Functional foods and their impact on health. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 60, 820–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martirosyan, D.M.; Singh, J. A new definition of functional food by FFC: What makes a new definition unique? Funct. Foods Health Dis. 2015, 5, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research, G.V. Functional Foods Market Size, Growth & Trends, Industry Report, 2025; ID: GVR-1-68038-195-5; 20209; Grand View Research: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Insights, F.B. Market Research Report; Fortune Business Insights: Maharashtra, India, 2020; p. 144. [Google Scholar]

- Koirala, S.; Anal, A.K. Probiotics-based foods and beverages as future foods and their overall safety and regulatory claims. Future Foods 2021, 3, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi Khaneghah, A.; Abhari, K.; Eş, I.; Soares, M.B.; Oliveira, R.B.A.; Hosseini, H.; Rezaei, M.; Balthazar, C.F.; Silva, R.; Cruz, A.G.; et al. Interactions between probiotics and pathogenic microorganisms in hosts and foods: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 95, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivamaruthi, B.S.; Prasanth, M.I.; Kesika, P.; Chaiyasut, C. Probiotics in human mental health and diseases—A minireview. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2019, 18, 889–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryan, J.F.; O’Riordan, K.J.; Cowan, C.S.; Sandhu, K.V.; Bastiaanssen, T.F.; Boehme, M.; Codagnone, M.G.; Cussotto, S.; Fulling, C.; Golubeva, A.V. The microbiota-gut-brain axis. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1877–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesika, P.; Suganthy, N.; Sivamaruthi, B.S.; Chaiyasut, C. Role of gut-brain axis, gut microbial composition, and probiotic intervention in Alzheimer's disease. Life Sci. 2021, 264, 118627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, E.M.F.; Ramos, A.M.; Vanzela, E.S.L.; Stringheta, P.C.; de Oliveira Pinto, C.L.; Martins, J.M. Products of vegetable origin: A new alternative for the consumption of probiotic bacteria. Food Res. Int. 2013, 51, 764–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, B.K.; Fabricio, M.F.; Ayub, M.A.Z. Health effects and probiotic and prebiotic potential of Kombucha: A bibliometric and systematic review. Food Biosci. 2021, 44, 101332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emiljanowicz, K.E.; Malinowska-Pańczyk, E. Kombucha from alternative raw materials–The review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 3185–3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravorty, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Chatzinotas, A.; Chakraborty, W.; Bhattacharya, D.; Gachhui, R. Kombucha tea fermentation: Microbial and biochemical dynamics. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 220, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal-Soto, S.A.; Beaufort, S.; Bouajila, J.; Souchard, J.-P.; Renard, T.; Rollan, S.; Taillandier, P. Impact of fermentation conditions on the production of bioactive compounds with anticancer, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties in kombucha tea extracts. Process Biochem. 2019, 83, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitas, J.S.; Cvetanović, A.D.; Mašković, P.Z.; Švarc-Gajić, J.V.; Malbaša, R.V. Chemical composition and biological activity of novel types of kombucha beverages with yarrow. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 44, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolomedi, B.M.; Paglarini, C.S.; Brod, F.C.A. Bioactive compounds in kombucha: A review of substrate effect and fermentation conditions. Food Chem. 2022, 385, 132719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, A.A.; Suroto, D.A.; Utami, T.; Rahayu, E.S. Probiotic potential of kombucha drink from butterfly pea (Clitoria ternatea L.) flower with the addition of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum subsp. plantarum Dad-13. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2023, 51, 102776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, D. Biological activities of kombucha beverages: The need of clinical evidence. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 105, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.; Satyanarayanan, S.K.; Su, H. Nutraceuticals and probiotics in the management of psychiatric and neurological disorders: A focus on microbiota-gut-brain-immune axis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 90, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Wang, K.; Hu, J. Effect of probiotics on depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients 2016, 8, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKean, J.; Naug, H.; Nikbakht, E.; Amiet, B.; Colson, N. Probiotics and subclinical psychological symptoms in healthy participants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2017, 23, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastwood, J.; Walton, G.; Van Hemert, S.; Williams, C.; Lamport, D. The effect of probiotics on cognitive function across the human lifespan: A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 128, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirani, E.; Milajerdi, A.; Mirzaei, H.; Jamilian, H.; Mansournia, M.A.; Hallajzadeh, J.; Ghaderi, A. The effects of probiotic supplementation on mental health, biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress in patients with psychiatric disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 49, 102361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leta, V.; Ray Chaudhuri, K.; Milner, O.; Chung-Faye, G.; Metta, V.; Pariante, C.M.; Borsini, A. Neurogenic and anti-inflammatory effects of probiotics in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review of preclinical and clinical evidence. Brain Behav. Immun. 2021, 98, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrio, C.; Arias-Sánchez, S.; Martín-Monzón, I. The gut microbiota-brain axis, psychobiotics and its influence on brain and behaviour: A systematic review. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2022, 137, 105640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Weng, P.; Liu, L.; Zhang, R.; Wu, Z. The gut microbiota–brain axis: Role of the gut microbial metabolites of dietary food in obesity. Food Res. Int. 2022, 153, 110971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.-Y.; Ho, Y.-S.; Chang, R.C.-C. Linking circadian rhythms to microbiome-gut-brain axis in aging-associated neurodegenerative diseases. Ageing Res. Rev. 2022, 78, 101620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, H.J.; Park, H.Y. Gut Microbiota and Depression, Anxiety, and Cognitive Disorders. In Sex/Gender-Specific Medicine in the Gastrointestinal Diseases; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 379–391. [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti, A.; Geurts, L.; Hoyles, L.; Iozzo, P.; Kraneveld, A.D.; La Fata, G.; Miani, M.; Patterson, E.; Pot, B.; Shortt, C.; et al. The microbiota–gut–brain axis: Pathways to better brain health. Perspectives on what we know, what we need to investigate and how to put knowledge into practice. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Huh, J.R.; Shah, K. Microbiota and the gut-brain-axis: Implications for new therapeutic design in the CNS. EBioMedicine 2022, 77, 103908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, L.; Wei, Y.; Hashimoto, K. Brain–gut–microbiota axis in depression: A historical overview and future directions. Brain Res. Bull. 2022, 182, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casertano, M.; Fogliano, V.; Ercolini, D. Psychobiotics, gut microbiota and fermented foods can help preserving mental health. Food Res. Int. 2022, 152, 110892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.; Wei, S.; Zong, X.; Wang, Y.; Jin, M. Microbiota-gut-brain axis and nutritional strategy under heat stress. Anim. Nutr. 2021, 7, 1329–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.B.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S.; et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lof, J.; Smits, K.; Melotte, V.; Kuil, L.E. The health effect of probiotics on high-fat diet-induced cognitive impairment, depression and anxiety: A cross-species systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2022, 136, 104634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zendeboodi, F.; Khorshidian, N.; Mortazavian, A.M.; da Cruz, A.G. Probiotic: Conceptualization from a new approach. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2020, 32, 103–123. [Google Scholar]

- Shafi, A.; Naeem Raja, H.; Farooq, U.; Akram, K.; Hayat, Z.; Naz, A.; Nadeem, H.R. Antimicrobial and antidiabetic potential of synbiotic fermented milk: A functional dairy product. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2019, 72, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Sahoo, N.K.; Mehan, S.; verma, B. The importance of gut-brain axis and use of probiotics as a treatment strategy for multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2023, 71, 104547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leblhuber, F.; Ehrlich, D.; Steiner, K.; Geisler, S.; Fuchs, D.; Lanser, L.; Kurz, K. The Immunopathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease Is Related to the Composition of Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2021, 13, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luna, R.A.; Foster, J.A. Gut brain axis: Diet microbiota interactions and implications for modulation of anxiety and depression. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2015, 32, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akkasheh, G.; Kashani-Poor, Z.; Tajabadi-Ebrahimi, M.; Jafari, P.; Akbari, H.; Taghizadeh, M.; Memarzadeh, M.R.; Asemi, Z.; Esmaillzadeh, A. Clinical and metabolic response to probiotic administration in patients with major depressive disorder: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Nutrition 2016, 32, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, G.; Mookherjee, S. Probiotics-targeting new milestones from gut health to mental health. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2021, 368, fnab096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, D.; Bhattacharya, S.; Patra, M.M.; Chakravorty, S.; Sarkar, S.; Chakraborty, W.; Koley, H.; Gachhui, R. Antibacterial Activity of Polyphenolic Fraction of Kombucha Against Enteric Bacterial Pathogens. Curr. Microbiol. 2016, 73, 885–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laavanya, D.; Shirkole, S.; Balasubramanian, P. Current challenges, applications and future perspectives of SCOBY cellulose of Kombucha fermentation. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Kim, J.; Wang, S.; Sung, S.; Kim, N.; Lee, H.-H.; Seo, Y.-S.; Jung, Y. Hepatoprotective effect of kombucha tea in rodent model of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrútia, G.; Bonfill, X. PRISMA declaration: A proposal to improve the publication of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Med. Clin. 2010, 135, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuliana, N.; Nurainy, F.; Sari, G.W.; Widiastuti, E.L. Total microbe, physicochemical property, and antioxidative activity during fermentation of cocoa honey into kombucha functional drink. Appl. Food Res. 2023, 3, 100297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilic, G.; Sengun, I.Y. Bioactive properties of Kombucha beverages produced with Anatolian hawthorn (Crataegus orientalis) and nettle (Urtica dioica) leaves. Food Biosci. 2023, 53, 102631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzaroli, C.; Sordini, B.; Daidone, L.; Veneziani, G.; Esposto, S.; Urbani, S.; Selvaggini, R.; Servili, M.; Taticchi, A. Recovery and valorization of food industry by-products through the application of Olea europaea L. leaves in kombucha tea manufacturing. Food Biosci. 2023, 53, 102551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira de Miranda, J.; Martins Pereira Belo, G.; Silva de Lima, L.; Alencar Silva, K.; Matsue Uekane, T.; Gonçalves Martins Gonzalez, A.; Naciuk Castelo Branco, V.; Souza Pitangui, N.; Freitas Fernandes, F.; Ribeiro Lima, A. Arabic coffee infusion based kombucha: Characterization and biological activity during fermentation, and in vivo toxicity. Food Chem. 2023, 412, 135556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, E.J.; Kim, H.; Hong, K.-B.; Suh, H.J.; Ahn, Y. Hangover-Relieving Effect of Ginseng Berry Kombucha Fermented by Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Gluconobacter oxydans in Ethanol-Treated Cells and Mice Model. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, F.S.; Cohen, M.; Lau, K.; Brand-Miller, J.C. Glycemic index and insulin index after a standard carbohydrate meal consumed with live kombucha: A randomised, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1036717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira Oliveira, J.; Machado da Costa, F.; Gonçalvez da Silva, T.; Dotto Simões, G.; dos Santos Pereira, E.; Quevedo da Costa, P.; Andreazza, R.; Cavalheiro Schenkel, P.; Pieniz, S. Green tea and kombucha characterization: Phenolic composition, antioxidant capacity and enzymatic inhibition potential. Food Chem. 2023, 408, 135206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, A.; Cristani, C.; Palla, M.; Di Giorgi, R.; Giovannetti, M.; Agnolucci, M. Storage time and temperature affect microbial dynamics of yeasts and acetic acid bacteria in a kombucha beverage. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 382, 109934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, Z.; Asir, Y. Assessment of instrumental and sensory quality characteristics of the bread products enriched with Kombucha tea. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2022, 29, 100562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permatasari, H.K.; Firani, N.K.; Prijadi, B.; Irnandi, D.F.; Riawan, W.; Yusuf, M.; Amar, N.; Chandra, L.A.; Yusuf, V.M.; Subali, A.D.; et al. Kombucha drink enriched with sea grapes (Caulerpa racemosa) as potential functional beverage to contrast obesity: An in vivo and in vitro approach. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2022, 49, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Noronha, M.C.; Cardoso, R.R.; dos Santos D’Almeida, C.T.; Vieira do Carmo, M.A.; Azevedo, L.; Maltarollo, V.G.; Júnior, J.I.R.; Eller, M.R.; Cameron, L.C.; Ferreira, M.S.L.; et al. Black tea kombucha: Physicochemical, microbiological and comprehensive phenolic profile changes during fermentation, and antimalarial activity. Food Chem. 2022, 384, 132515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, E.L.; Netto, M.C.; Bendel Junior, L.; de Moura, L.F.; Brasil, G.A.; Bertolazi, A.A.; de Lima, E.M.; Vasconcelos, C.M. Kombucha fermentation in blueberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) beverage and its in vivo gastroprotective effect: Preliminary study. Future Foods 2022, 5, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permatasari, H.K.; Nurkolis, F.; Gunawan, W.B.; Yusuf, V.M.; Yusuf, M.; Kusuma, R.J.; Sabrina, N.; Muharram, F.R.; Taslim, N.A.; Mayulu, N.; et al. Modulation of gut microbiota and markers of metabolic syndrome in mice on cholesterol and fat enriched diet by butterfly pea flower kombucha. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2022, 5, 1251–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aung, T.; Eun, J.-B. Impact of time and temperature on the physicochemical, microbiological, and nutraceutical properties of laver kombucha (Porphyra dentata) during fermentation. LWT 2022, 154, 112643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluz, M.I.; Pietrzyk, K.; Pastuszczak, M.; Kacaniova, M.; Kita, A.; Kapusta, I.; Zaguła, G.; Zagrobelna, E.; Struś, K.; Marciniak-Lukasiak, K.; et al. Microbiological and Physicochemical Composition of Various Types of Homemade Kombucha Beverages Using Alternative Kinds of Sugars. Foods 2022, 11, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, C.Q.; Wu, Y.X.; Farooq, M.A.; Young, D.J.; Wong, J.W.C.; Chang, K.; Tian, B.; Kumari, A.; et al. Impact of different processing techniques on reduction in oil content in deep-fried donuts when using kombucha cellulose hydrolysates. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 997097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Júnior, J.C.d.; Magnani, M.; Almeida da Costa, W.K.; Madruga, M.S.; Souza Olegário, L.; da Silva Campelo Borges, G.; Macedo Dantas, A.; Lima, M.d.S.; de Lima, L.C.; de Lima Brito, I.; et al. Traditional and flavored kombuchas with pitanga and umbu-cajá pulps: Chemical properties, antioxidants, and bioactive compounds. Food Biosci. 2021, 44, 101380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permatasari, H.K.; Nurkolis, F.; Augusta, P.S.; Mayulu, N.; Kuswari, M.; Taslim, N.A.; Wewengkang, D.S.; Batubara, S.C.; Ben Gunawan, W. Kombucha tea from seagrapes (Caulerpa racemosa) potential as a functional anti-ageing food: In vitro and in vivo study. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifudin, S.A.; Ho, W.Y.; Yeap, S.K.; Abdullah, R.; Koh, S.P. Fermentation and characterisation of potential kombucha cultures on papaya-based substrates. LWT 2021, 151, 112060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, K.A.; Uekane, T.M.; de Miranda, J.F.; Ruiz, L.F.; da Motta, J.C.B.; Silva, C.B.; de Souza Pitangui, N.; Gonzalez, A.G.M.; Fernandes, F.F.; Lima, A.R. Kombucha beverage from non-conventional edible plant infusion and green tea: Characterization, toxicity, antioxidant activities and antimicrobial properties. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2021, 34, 102032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrutia, M.A.D.; Ramos, A.G.; Menegusso, R.B.; Lenz, R.D.; Ramos, M.G.; Tarone, A.G.; Cazarin, C.B.B.; Cottica, S.M.; da Silva, S.A.V.; Bernardi, D.M. Effects of supplementation with kombucha and green banana flour on Wistar rats fed with a cafeteria diet. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, T.; Eun, J.-B. Production and characterization of a novel beverage from laver (Porphyra dentata) through fermentation with kombucha consortium. Food Chem. 2021, 350, 129274. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sknepnek, A.; Tomić, S.; Miletić, D.; Lević, S.; Čolić, M.; Nedović, V.; Nikšić, M. Fermentation characteristics of novel Coriolus versicolor and Lentinus edodes kombucha beverages and immunomodulatory potential of their polysaccharide extracts. Food Chem. 2021, 342, 128344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rasouli, L.; Aryaeian, N.; Gorjian, M.; Nourbakhsh, M.; Amiri, F. Evaluation of cytotoxicity and anticancer activity of kombucha and doxorubicin combination therapy on colorectal cancer cell line HCT-116. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2021, 10, 376. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Değirmencioğlu, N.; Yıldız, E.; Sahan, Y.; Güldas, M.; Gürbüz, O. Impact of tea leaves types on antioxidant properties and bioaccessibility of kombucha. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 2304–2312. [Google Scholar]

- La Torre, C.; Fazio, A.; Caputo, P.; Plastina, P.; Caroleo, M.C.; Cannataro, R.; Cione, E. Effects of Long-Term Storage on Radical Scavenging Properties and Phenolic Content of Kombucha from Black Tea. Molecules 2021, 26, 5474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamer, C.E.; Temel, S.G.; Suna, S.; Karabacak, A.O.; Ozcan, T.; Ersan, L.Y.; Kaya, B.T.; Copur, O.U. Evaluation of bioaccessibility and functional properties of kombucha beverages fortified with different medicinal plant extracts. Turk. J. Agric. For. 2021, 45, 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lavefve, L.; Cureau, N.; Rodhouse, L.; Marasini, D.; Walker, L.M.; Ashley, D.; Lee, S.O.; Gadonna-Widehem, P.; Anton, P.M.; Carbonero, F. Microbiota profiles and dynamics in fermented plant-based products and preliminary assessment of their in vitro gut microbiota modulation. Food Front. 2021, 2, 268–281. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, D.R.; Santos, L.O.; Prentice-Hernández, C. Antioxidant and antibacterial activity of a beverage obtained by fermentation of yerba-maté (Ilex paraguariensis) with symbiotic kombucha culture. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45, e15101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal-Soto, S.A.; Bouajila, J.; Pace, M.; Leech, J.; Cotter, P.D.; Souchard, J.-P.; Taillandier, P.; Beaufort, S. Metabolome-microbiome signatures in the fermented beverage, Kombucha. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 333, 108778. [Google Scholar]

- Mizuta, A.G.; de Menezes, J.L.; Dutra, T.V.; Ferreira, T.V.; Castro, J.C.; da Silva, C.A.J.; Pilau, E.J.; Machinski Junior, M.; Abreu Filho, B.A.d. Evaluation of antimicrobial activity of green tea kombucha at two fermentation time points against Alicyclobacillus spp. LWT 2020, 130, 109641. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, C.; Hu, W.; Tang, S.; Meng, L.; Huang, Z.; Xu, X.; Xia, X.; Azi, F.; Dong, M. Isolation and identification of Starmerella davenportii strain Do18 and its application in black tea beverage fermentation. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2020, 9, 355–362. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Taheur, F.; Mansour, C.; Ben Jeddou, K.; Machreki, Y.; Kouidhi, B.; Abdulhakim, J.A.; Chaieb, K. Aflatoxin B1 degradation by microorganisms isolated from Kombucha culture. Toxicon 2020, 179, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, D.; Sinha, R.; Mukherjee, P.; Howlader, D.R.; Nag, D.; Sarkar, S.; Koley, H.; Withey, J.H.; Gachhui, R. Anti-virulence activity of polyphenolic fraction isolated from Kombucha against Vibrio cholerae. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 140, 103927. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, R.R.; Neto, R.O.; dos Santos D’Almeida, C.T.; do Nascimento, T.P.; Pressete, C.G.; Azevedo, L.; Martino, H.S.D.; Cameron, L.C.; Ferreira, M.S.L.; Barros, F.A.R.d. Kombuchas from green and black teas have different phenolic profile, which impacts their antioxidant capacities, antibacterial and antiproliferative activities. Food Res. Int. 2020, 128, 108782. [Google Scholar]

- Harisman, E.K.; Puspitasari, Y.E. The kombucha from Rhizophora mucronata Lam. herbal tea: Characteristics and the potential as an antidiabetic beverage. J. Pharm. Pharmacogn. Res. 2020, 8, 410–421. [Google Scholar]

- Zofia, N.-Ł.; Aleksandra, Z.; Tomasz, B.; Martyna, Z.-D.; Magdalena, Z.; Zofia, H.-B.; Tomasz, W. Effect of Fermentation Time on Antioxidant and Anti-Ageing Properties of Green Coffee Kombucha Ferments. Molecules 2020, 25, 5394. [Google Scholar]

- Zubaidah, E.; Afgani, C.A.; Kalsum, U.; Srianta, I.; Blanc, P.J. Comparison of in vivo antidiabetes activity of snake fruit Kombucha, black tea Kombucha and metformin. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 17, 465–469. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, C.; Tang, S.; Azi, F.; Hu, W.; Dong, M. Use of kombucha consortium to transform soy whey into a novel functional beverage. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 52, 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Gaggìa, F.; Baffoni, L.; Galiano, M.; Nielsen, D.S.; Jakobsen, R.R.; Castro-Mejía, J.L.; Bosi, S.; Truzzi, F.; Musumeci, F.; Dinelli, G.; et al. Kombucha Beverage from Green, Black and Rooibos Teas: A Comparative Study Looking at Microbiology, Chemistry and Antioxidant Activity. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Abuduaibifu, A.; Tamer, C.E. Evaluation of physicochemical and bioaccessibility properties of goji berry kombucha. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2019, 43, e14077. [Google Scholar]

- Zubaidah, E.; Dewantari, F.J.; Novitasari, F.R.; Srianta, I.; Blanc, P.J. Potential of snake fruit (Salacca zalacca (Gaerth.) Voss) for the development of a beverage through fermentation with the Kombucha consortium. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2018, 13, 198–203. [Google Scholar]

- Uțoiu, E.; Matei, F.; Toma, A.; Diguță, C.F.; Ștefan, L.M.; Mănoiu, S.; Vrăjmașu, V.V.; Moraru, I.; Oancea, A.; Israel-Roming, F.; et al. Bee Collected Pollen with Enhanced Health Benefits, Produced by Fermentation with a Kombucha Consortium. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1365. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Cabral, B.D.; Larrosa-Pérez, M.; Gallegos-Infante, J.A.; Moreno-Jiménez, M.R.; González-Laredo, R.F.; Rutiaga-Quiñones, J.G.; Gamboa-Gómez, C.I.; Rocha-Guzmán, N.E. Oak kombucha protects against oxidative stress and inflammatory processes. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2017, 272, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudi, E.; Saeidi, M.; Marashi, M.A.; Moafi, A.; Mahmoodi, V.; Zeinolabedini Zamani, M. In vitro activity of kombucha tea ethyl acetate fraction against Malassezia species isolated from seborrhoeic dermatitis. Curr. Med. Mycol. 2016, 2, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sun, T.-Y.; Li, J.-S.; Chen, C. Effects of blending wheatgrass juice on enhancing phenolic compounds and antioxidant activities of traditional kombucha beverage. J. Food Drug Anal. 2015, 23, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hrnjez, D.; Vaštag, Ž.; Milanović, S.; Vukić, V.; Iličić, M.; Popović, L.; Kanurić, K. The biological activity of fermented dairy products obtained by kombucha and conventional starter cultures during storage. J. Funct. Foods 2014, 10, 336–345. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Gachhui, R.; Sil, P.C. Effect of Kombucha, a fermented black tea in attenuating oxidative stress mediated tissue damage in alloxan induced diabetic rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 60, 328–340. [Google Scholar]

- Srihari, T.; Arunkumar, R.; Arunakaran, J.; Satyanarayana, U. Downregulation of signalling molecules involved in angiogenesis of prostate cancer cell line (PC-3) by kombucha (lyophilized). Biomed. Prev. Nutr. 2013, 3, 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Aloulou, A.; Hamden, K.; Elloumi, D.; Ali, M.B.; Hargafi, K.; Jaouadi, B.; Ayadi, F.; Elfeki, A.; Ammar, E. Hypoglycemic and antilipidemic properties of kombucha tea in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 12, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Jayabalan, R.; Subathradevi, P.; Marimuthu, S.; Sathishkumar, M.; Swaminathan, K. Changes in free-radical scavenging ability of kombucha tea during fermentation. Food Chem. 2008, 109, 227–234. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, S.-C.; Chen, C. Effects of origins and fermentation time on the antioxidant activities of kombucha. Food Chem. 2006, 98, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, M.G.; de Lima, M.; Reolon Schmidt, V.C. Technological aspects of kombucha, its applications and the symbiotic culture (SCOBY), and extraction of compounds of interest: A literature review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 110, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Fawal, H.A.N. Neurotoxicology. In Encyclopedia of Environmental Health; Nriagu, J.O., Ed.; Elsevier: Burlington, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, S.; Poore, M.; Gerdes, S.; Nedveck, D.; Lauridsen, L.; Kristensen, H.T.; Jensen, H.M.; Byrd, P.M.; Ouwehand, A.C.; Patterson, E.; et al. Transcriptomics reveal different metabolic strategies for acid resistance and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) production in select Levilactobacillus brevis strains. Microb. Cell Factories 2021, 20, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, M.M. Glutamate: The Master Neurotransmitter and Its Implications in Chronic Stress and Mood Disorders. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 722323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaldi, R.; Gibson, G.R.; Vulevic, J.; Giallourou, N.; Castro-Mejía, J.L.; Hansen, L.H.; Leigh Gibson, E.; Nielsen, D.S.; Costabile, A. A prebiotic intervention study in children with autism spectrum disorders (ASDs). Microbiome 2018, 6, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto-Sanchez, M.I.; Hall, G.B.; Ghajar, K.; Nardelli, A.; Bolino, C.; Lau, J.T.; Martin, F.-P.; Cominetti, O.; Welsh, C.; Rieder, A. Probiotic Bifidobacterium longum NCC3001 reduces depression scores and alters brain activity: A pilot study in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 448–459.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamtaji, O.R.; Heidari-Soureshjani, R.; Mirhosseini, N.; Kouchaki, E.; Bahmani, F.; Aghadavod, E.; Tajabadi-Ebrahimi, M.; Asemi, Z. Probiotic and selenium co-supplementation, and the effects on clinical, metabolic and genetic status in Alzheimer's disease: A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 2569–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.; Letchumanan, V.; Thum, C.C.; Thurairajasingam, S.; Lee, L.-H. A Microbial-Based Approach to Mental Health: The Potential of Probiotics in the Treatment of Depression. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, A.; Banafshe, H.R.; Mirhosseini, N.; Moradi, M.; Karimi, M.-A.; Mehrzad, F.; Bahmani, F.; Asemi, Z. Clinical and metabolic response to vitamin D plus probiotic in schizophrenia patients. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghamohammad, S.; Hafezi, A.; Rohani, M. Probiotics as functional foods: How probiotics can alleviate the symptoms of neurological disabilities. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 163, 114816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Adhikari, K. Current trends in kombucha: Marketing perspectives and the need for improved sensory research. Beverages 2020, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, P.; Penas, M.R.; Pintado, M.; Oliveira-Silva, P. Kombucha: Perceptions and Future Prospects. Foods 2022, 11, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).