Abstract

Background: In order to reduce the prolonged duration of orthodontic treatment, several surgical techniques have been proposed over the years. Corticotomy and piezocision are the two most widely used techniques, and, given the lack of consensus in the literature, along with the renewed interest in these approaches in recent years, the primary objective of this study is to evaluate their effectiveness in accelerating canine retraction in patients requiring extraction of the upper first premolar and, as a secondary objective, to assess if there is a worsening of periodontal health and how the surgical approach is perceived by the patient. Methods: An electronic search was performed on PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Embase, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) up to 30 November 2024. The PRISMA statement was adopted for the realization of the review, and the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias assessment tool (RoB 2) was used to assess the studies’ quality. Results: After full text assessment, fifteen randomized clinical trials (14 split mouth design, 1 single-blind, single-center design) covering 326 patients (mean age 20, 19 years) were included. The data collected reveal that corticotomy accelerates canine retraction by 1.5 to 4 times, while piezocision achieves retraction 1.5 to 2 times faster, making corticotomy the most effective technique. No statistically significant adverse effects on periodontal ligament, molar anchorage loss, or root resorption were observed following the two surgical techniques. In addition, patients reported experiencing mild to moderate pain. Conclusions: Corticotomy and piezocision are effective techniques for accelerating upper canine retraction in extraction cases, significantly reducing the overall duration of orthodontic treatment.

1. Introduction

The long duration of orthodontic treatment is one of the major concerns for orthodontic patients, especially given the increased proportion of adults seeking orthodontic treatment. Several factors influence the length of therapy, including age, gender, arch, and bone quality [1,2,3,4]. Moreover, shortening the duration of the treatment is not only satisfying for the patient, but it may also minimize and reduce the risk of experiencing various adverse effects such as pain, discomfort, caries, white spot appearance, gingival recession, and apical root resorption associated with the orthodontic therapy [5].

Over the years, several techniques have been proposed to decrease the overall orthodontic treatment time, and they can be classified into three categories:

- (1)

- Pharmacological: vitamin D3 [6], corticosteroids [7], and prostaglandins [8] administered locally and systemically;

- (2)

- Physical: local heat application, low-level laser therapy (LLLT) [9], light-emitting diode (LED) therapy [10], and light vibrational forces (LVF) [11];

- (3)

- Surgical: corticotomy, corticision, and piezocision.

Among them, the surgical approaches have attracted considerable scientific interest.

Corticotomy is the surgical procedure consisting of intentional cutting using surgical burs of the cortical bone in order to remove the resistance of dense cortical bone.

What happens in bone structures consequently to a corticotomy was first explained by Frost, who introduced the concept of regional acceleratory phenomenon (RAP) [12]. After surgical bone injury, there is a local transitory acceleration in bone turnover activity, and consequently, as a result, there is a reduction in bone density, which is expected to facilitate orthodontic dental movement [13]. However, it remains an invasive technique requiring flap elevation, causing postoperative discomfort and posing potential complications, and therefore is often rejected by patients.

Over time, alternative, less invasive techniques have been introduced aiming to overcome these complications. One of the methods proposed to respond to this need was corticision; this surgical procedure does not require flap elevation and is performed using a reinforced scalpel and a mallet [14]. However, the existing literature on corticision primarily relies on studies conducted with animals [15,16].

Thereafter, based on the corticision technique, a new technique called piezocision was proposed, characterized by the replacement of the scalpel and mallet with a piezosurgical knife. First described by Dibart et al., it consists of microincisions in the gingival tissue and bone incisions made with this ultrasonic piezosurgical knife [17]. This is a safer technique without the fear of damaging the tooth root and with excellent control of bleeding. Furthermore, selective tunneling can be performed when soft or hard tissue grafting is required [18].

The application of these surgical techniques has been proposed and used to accelerate several stages of orthodontic therapy; among them, space closure and canine retraction are two of the most challenging and time-consuming treatment steps. This is significant considering that Class II malocclusion is the most common malocclusion, often resolved by extracting two premolars. Moreover, extraction of the upper bicuspids is commonly performed to resolve class I cases with biprotrusion or increased overjet.

Referring to the timing, an average of 5 months is needed to achieve complete maxillary canine retraction with fixed orthodontic appliances, recording a total duration of therapy of approximately 1.5 to 2 years with fixed appliances [19].

Considering that corticotomy and piezocision are the two techniques that have been most widely employed, that no consensus exists yet in the literature, and that mainly in recent years an interest in these two techniques has revived, the main purpose of the present study is to assess if the integration of these surgical techniques will make traditional orthodontic therapy more efficient in patients requiring maxillary first premolar extraction. In addition, an attempt was made to determine whether, as a second objective, a deterioration of periodontal health occurs and how the surgical approach is experienced by the patient.

2. Materials and Methods

The present systematic review was performed in accordance with the PRISMA statement of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [20]. The protocol was registered in PROSPERO, the international prospective register of systematic reviews, under the number CRD42024615824.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were established according to the PICO framework, defined as follows: “(P) in patients requiring maxillary first premolar extraction and subsequent canine retraction (I) could corticotomy or (C) piezocision (O) accelerate orthodontic movement?”.

The included studies were randomized clinical trials (RCTs) concerning the maxillary canine retraction in young or adult healthy patients treated using fixed multibracket appliances with corticotomy and/or the piezocision procedure; articles reporting the duration of treatment, speed, and/or rate of tooth movement with corticotomy and/or the piezocision procedure compared to conventional orthodontic treatment.

The excluded studies were the ones on patients with previous orthodontic treatment, systemic diseases, periodontal disease, or any disorders or therapies that might have affected bone turnover or density. Case-control, cohort, and cross-sectional, non-randomized clinical trials (Nr-RCTs); reviews; case reports; case series; in vitro; and animal studies were rejected. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are also summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

A comprehensive search strategy was designed, and the following online databases were recruited for the search: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Embase, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). The search was conducted until 30 November 2024, and no time and language restrictions were applied.

For all other databases, the same advanced search was performed using the same combination of keywords, MeSH (medical subject heading) terms, and Boolean operators. The strategies designed for each database are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Search strategy for each database.

2.3. Selection Process

Two authors (E.L. and E.P.) independently conducted first the research process and subsequently the screening of the obtained results. To evaluate the agreement level among the reviewers, Cohen’s kappa coefficient [21] was calculated, and, in case of disagreement, a third reviewer was consulted (E.S.). Authors showed a substantial agreement (Cohen’s kappa: 0.66). Therefore, an initial screening was conducted based on titles and abstracts, selecting all potentially eligible studies that focused on canine retraction.

Subsequently, a second screening was conducted on the full text of the articles according to the established inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.4. Data Collection

The two main reviewers selected and extracted the data of interest according to the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group data extraction model.

The following data were extracted from the selected papers:

- (a)

- Authors and year of publication;

- (b)

- Study type;

- (c)

- Sample size of study group and of control group;

- (d)

- Gender of participants;

- (e)

- Average age;

- (f)

- Characteristics of malocclusion;

- (g)

- Surgical intervention;

- (h)

- Type of orthodontic fixed appliances;

- (i)

- Force reactivation;

- (j)

- Results.

The primary outcome registered was the rate/velocity of canine retraction data; data on anchorage loss, canine root resorption, periodontal indexes, and the patient’s experience were considered as a secondary outcome.

2.5. Quality Assessment

Articles included in the review underwent a quality assessment; the risk of bias of the included randomized clinical trial was independently conducted by two authors (E.L. and F.B.), using the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias assessment tool (RoB 2) [22].

Any disagreement was discussed and resolved by consensus when necessary.

Bias is assessed in five distinct domains: the randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome, and selection of the reported result. Finally, all included studies were evaluated as low risk, some concerns, or high risk.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

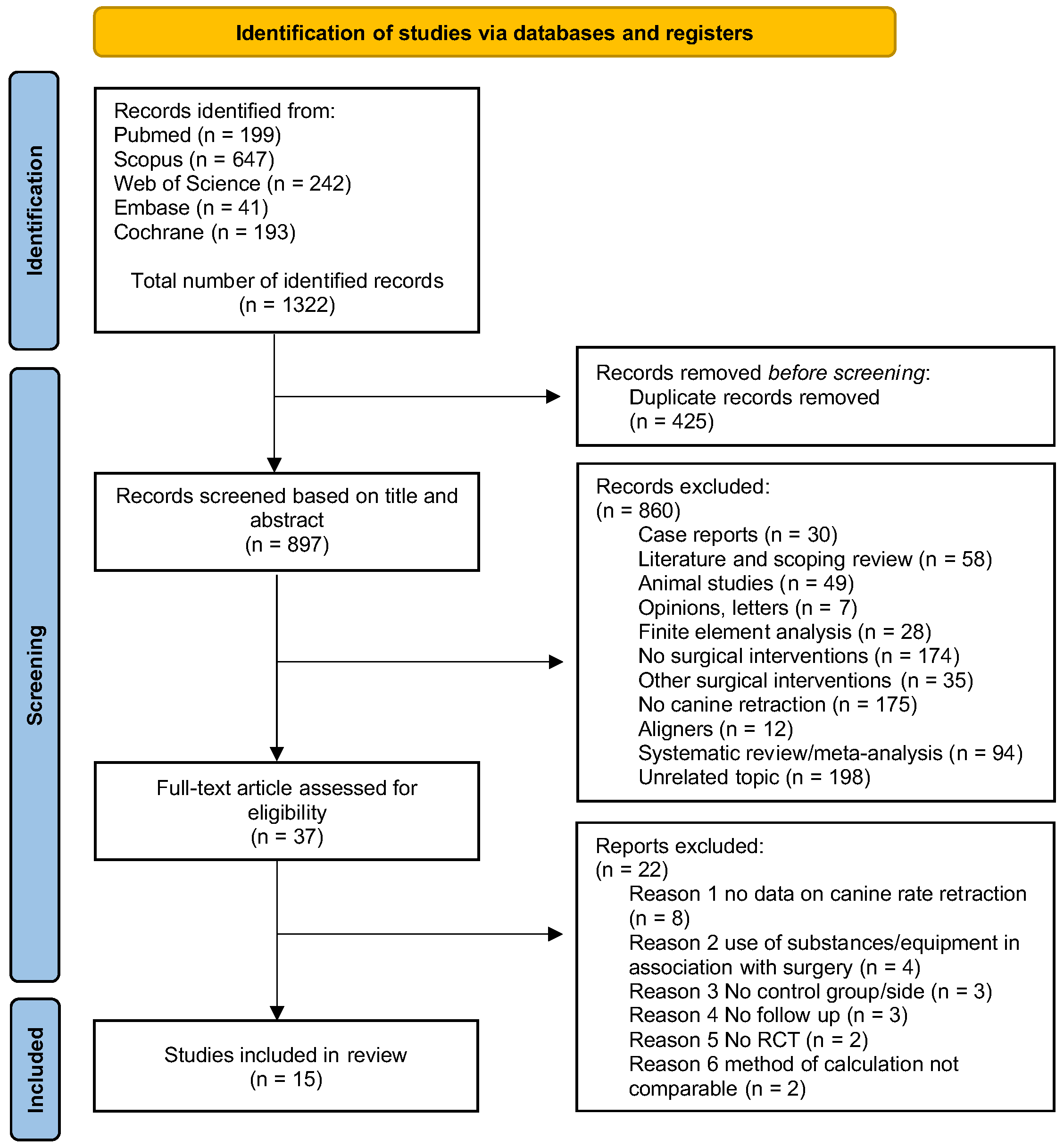

The database search retrieved 1322 abstracts: 199 from PubMed, 647 from Scopus, 242 from Web of Science, and 193 from Cochrane. Following duplicate removal, 897 papers were screened through the reading of the title and abstract and excluded according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. After this initial screening, 37 studies were assessed for eligibility based on reading the full text. Finally, 15 RCTs were included in the qualitative synthesis. The flowchart of the screening process according to the PRISMA statement is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart, flow diagram of the performed search.

The comprehensive PRISMA 2020 Checklist, outlining all reporting elements addressed in this review, is available in Table S1 in the Supplementary Material.

3.2. Study Characteristics

The key characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 3. All included studies were RCTs, all of them with a split-mouth design [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36] except for one with a single-blind, single-center design [37]. All included studies evaluated the efficacy of corticotomy and/or piezocision compared to conventional orthodontic treatment in upper canine retraction after upper first premolar extraction. Concretely, five of them compared conventional canine retraction with piezocision [25,28,30,31,33], seven with corticotomy [24,27,29,32,34,35,36,37], and in three studies both surgical techniques were evaluated [23,26]. The detailed description of the surgical technique can be found in Table S2 in the Supplementary Material.

Table 3.

Study characteristics and results. Author and year of publication, type of study, intervention (piezotomy and/or corticocision), number of participants and gender, mean age, initial malocclusion, characteristics of the fixed orthodontic appliance, force reactivation, primary outcome results, secondary outcomes, and the follow-up period of the 15 included studies have been compiled in the table.

3.2.1. Surgical Technique

The surgical technique employed in each trial is detailed in Table 3.

Corticotomy was performed in ten studies [23,24,27,29,32,34,35,36,37]. In five of these studies [23,24,32,34,35], only a buccal flap was performed; in two [27,37], both buccal and palatal flaps were elevated; and in three, no flap was raised [26,29,36].

In studies involving corticotomy, a certain variability was observed in the surgical techniques employed as well as in the equipment used. Specifically, some studies performed corticotomy with vertical cuts [23,37], while others utilized perforations [24,26,29,36], and several combined both approaches [27,32,34,35]. In the majority of studies, round burs mounted on a micromotor were utilized [24,27,32,35,36], while a piezotome was employed in two studies [23,37], although Er:YAG laser technology was used in corticotomy flapless procedures [26,27,36].

Piezocision was performed in seven studies [23,25,26,28,30,31,33] and, in all cases, the surgery was flapless, following a similar surgical technique. Notably, in all studies, the procedure was performed using a piezotome to create vertical incisions.

Regarding the timing of extraction, in four studies, the surgical procedure was performed immediately after premolar extraction [23,24,32,35]. In three studies, this information was not clearly provided [25,33,34]; however, in most cases, premolar extractions were carried out significantly earlier than the piezocision and/or corticotomy, ranging from four weeks [27] to four months prior [29,30], or even before the orthodontic appliance was applied [26,28,31,36,37].

3.2.2. Orthodontic Appliance

Properties relating to the orthodontic appliances, canine traction systems, and anchorage methods employed in each trial were described in Table 3.

In the majority of the included studies, the application of orthodontic force for canine retraction occurred during the same appointment in which piezocision and/or corticotomy were performed. Exceptions were found in three studies: in two of them [34,37], force application started three days later, while in the third it was not started until two weeks later [32]. However, in all studies, the alignment and leveling stages were first completed, and only after the insertion of a rigid steel wire did the canine retraction begin.

Canine retraction was achieved in all studies using a closed NiTi coil spring with an average force of 150 g (ranging from 120 to 250 gr). Only two studies diverged: in one, an elastic chain was used [25], while in the other, an open vertical loop was applied [32]; however, in both cases, the force exerted was comparable to that used in the other studies.

3.3. Canine Rate Retraction

The primary outcome assessed was the amount of canine distalization, and the values reported in each study are summarized in Table 3.

In six out of seven studies, canine retraction was significantly faster on the side/group where piezocision was performed than in the control side/group [23,25,26,28,30,33]. Notably, this finding was consistently significant during the first two months of observation. Only one study did not find a statistically significant difference [31] (p > 0.05).

Canine retraction was significantly faster in the side or corticotomy group than in the control in 9 out of 10 studies [23,24,27,32,34,35,36,37]. A statistically significant difference was not observed in one single study [29] (p > 0.05).

Two studies assessed both surgical techniques [23,26]: Abbas [23] reported that corticotomy produced a canine retraction 1.5 to 2 times faster, while piezocision accelerated retraction by 1.5 times. Consequently, corticotomy produced higher rates of canine movement than piezocision. In contrast, Alfawal’s study [26] found no statistically significant differences between the two surgical techniques (p > 0.05).

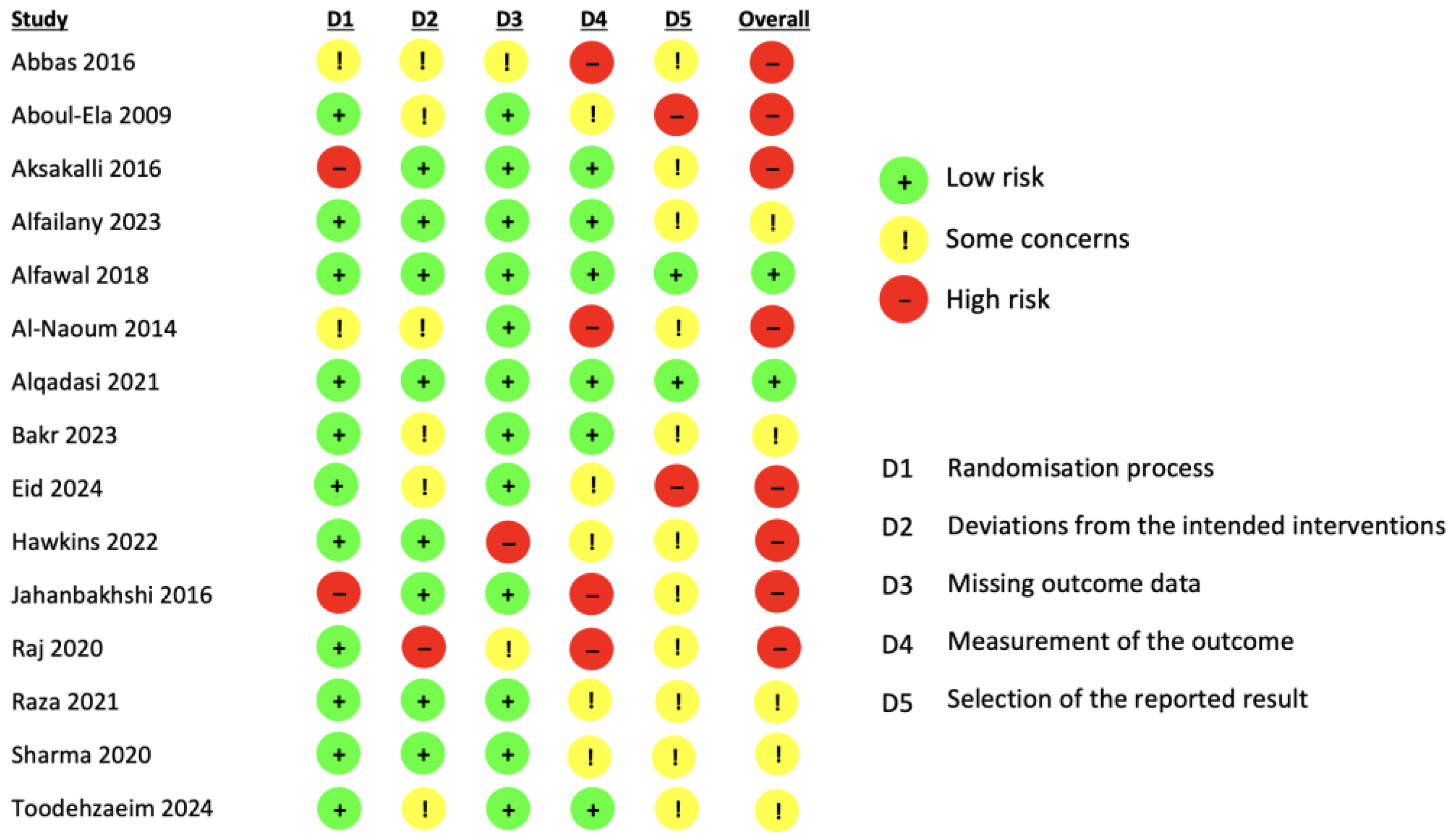

3.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

According to RoB 2 (Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias assessment tool), the quality of the included studies is described in Figure 2. Eight studies were categorized as having a high risk of bias [23,24,25,27,30,31,32,33], five studies were evaluated with some concerns [29,34,35,36,37] and only two studies were classified as low risk [26,28].

Figure 2.

Risk of bias of the included studies according to the RoB 2, Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias assessment tool [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37].

A high risk of bias is unfortunately common in orthodontic studies, particularly in those using a split-mouth design. This is primarily because the nature of the interventions makes it impossible to blind patients, operators, or outcome assessors, which inherently increases the risk of performance and detection bias. Furthermore, the independence of outcomes and site-level randomization require careful consideration to avoid inflated assessments of the risk of bias.

4. Discussion

Based on the results of the present systematic review, it can be deduced that both corticotomy and piezocision are able to effectively improve the rate of canine retraction following the extraction of the maxillary first premolar compared to conventional orthodontic therapy. Indeed, the amount of canine retraction (primary outcome) achieved with corticotomy was 1.5 to 4 times greater compared to conventional therapy [23,24,27,32,34,35,36,37]. In a comparable manner, piezocision also resulted in a higher rate of canine retraction, ranging from 1.5 to 2 times faster compared to conventional orthodontics [23,25,26,28,30,33]. The measurement of canine retraction was performed directly in the oral cavity using a digital caliper in three studies [27,32,33]. However, in the majority of studies, an indirect measurement method was employed, as described by Ziegler and Ingervall [38].

Specifically, in seven studies, measurements were conducted digitally on plaster models that were subsequently scanned [23,24,25,28,29,31,36]; in two studies, measurements were performed directly on plaster models [34,37]; in another two studies, measurements were performed on photographs of dental models, and a millimeter ruler was included in the images to serve as a reference for correcting magnification and ensuring accurate linear measurements.

In extractive orthodontic cases, anchorage management is particularly critical, for which reason additional anchorage methods, such as miniscrews [24,28,29,30,32,35] or transpalatal arches [26,27,31,33,34,36,37], were used in almost all studies; it is noteworthy that the use of mini-implants for skeletal anchorage is becoming increasingly common [39]. Specifically, molar anchorage loss has been a finding of interest in the selected studies; in several studies there were no differences in molar anchorage loss between the surgical and the control side/group (p > 0.05) [23,24,26,31,35,36]. However, a greater loss of anchorage was recorded in the control group/side in three studies [25,29,37], showing that surgical interventions do not affect anchorage stability.

Root resorption is often considered to be the most regrettable complication of orthodontic treatment. The topic has yielded conflicting results in the literature; indeed, in terms of canine root resorption, the control groups of two studies showed a greater resorption [23,34], confirming the findings of Frost [12] that higher osteoclast activity and lower bone density linked to RAP osteopenia reduced the risk of root resorption. This suggested that surgical techniques succeed in accelerating tooth movement without nevertheless inducing root resorption. However, two studies [28,29] did not report significant differences in root resorption, whereas Eid et al. [30] described a greater root resorption, observed concomitantly with piezocision. Only one study used bone grafting in combination with corticotomy [34]; bone grafting would produce an increase in bone formation after an initial phase of bone turnover at the graft site [40].

Historically, corticotomy has been associated with a detrimental effect on the periodontal structures, leading to bone loss and gingival attachment loss. Periodontal status was assessed in seven studies [23,24,25,29,33,35,36], determined by considering parameters like the plaque index, the gingival index according to Silness and Loe’s method, probing depth, attachment level, and gingival recession.

The findings reported in the included articles appear encouraging, considering that the majority of studies did not report significant adverse periodontal effects [23,25,33,35,36]; this suggests that surgical interventions do not negatively impact periodontal health; however, careful periodontal monitoring post-surgery remains essential.

Aboul-Ela et al. [24] reported a significantly higher gingival index in the surgical group, while Bakr et al. [29] observed a significant increase in the plaque index in the group undergoing the surgical technique. Nevertheless, these findings are not considered clinically relevant due to their reversible nature. Excessive tipping or torquing movements in thin biotypes can lead to alveolar bone resorption, while controlled forces can stimulate adaptive remodeling without compromising periodontal health [41]. Adjunctive surgical techniques, such as piezocision and corticotomy, offer potential benefits in managing periodontal responses during orthodontic treatment. By accelerating tooth movement and reducing treatment duration, these approaches may help mitigate prolonged stress on the periodontium, which is particularly advantageous for thin biotypes prone to complications.

In the collective imagination, surgical procedures are often associated with pain and discomfort; however, in a case like this, where premolar extraction is necessary regardless, does the addition of corticotomy and/or piezocision lead to a notable increase in these sensations? Patient comfort and pain level have become topics of increasing interest in recent years, and, indeed, it is an aspect that has been measured in the five most recent studies [27,31,34,35,36]. In four studies, mild to moderate pain, discomfort, and swelling were recorded on the side where the piezotomy [31] or corticotomy [27,34,35] was performed. Pain, particularly significant on the day of the procedure, progressively decreased over time; for this reason, most patients considered the surgical procedure tolerable and recommended it considering the benefit. No significant differences were found in the pain score between the two groups in one study [36].

Orthodontic treatment involving extractions has long been debated for its potential impact on facial aesthetics. Unfortunately, no studies currently provide a comprehensive evaluation of the facial aesthetics of patients who have undergone extractions. However, this does not represent a significant concern, as the current literature suggests that accurate orthodontic treatment planning with precise control of incisor positioning in extraction and non-extraction cases can mitigate adverse effects on the profile [42].

Numerous RCTs in the literature have investigated the surgical techniques of interest; however, many of these were excluded from the current review as they focused on the efficacy of corticotomy and/or piezocision in en-masse extractive space [43,44] or in the management of impacted canines [45] and third molars [46,47,48]. The results recorded are consistent with those reported in the previous works of Patterson et al. [49] and Han et al. [50]. However, several limitations were noted in both studies: the quality of both papers was considered low due to the presence of multiple methodological problems, high risk of bias, and heterogeneity among the included articles. For example, Patterson’s review included studies on impacted canines and en masse canine retraction. In both cases, insufficient attention was placed on surgical techniques, as studies involving micro-osteoperations were also included without adequate differentiation. In the present review, considerable efforts were made to analyze the surgical techniques in detail and to ensure the comparability of the reported results. We also believe that an extremely optimistic assessment of the risk of bias of the included studies was made in the Han et al. study [50]. In the first month of canine retraction, anchorage loss and canine rotation were significantly lesser in the TC and FCAPs groups than in the control group (p < 0.001). On the contrary, the canines’ rotation amount after the completion of retraction was greater in the TC group than in the other two groups (p < 0.001).

Furthermore, the included studies were all RCTs with a split-mouth design that centered on canine retraction, with the exception of one study [37], which was a three-arm randomized controlled clinical trial. It is noteworthy how prevalently the split-mouth design is utilized in the orthodontic literature. This study design facilitates the control of inter-individual variability by using each subject as its own control, thus minimizing confounding factors such as age, gender, or baseline characteristics that could potentially influence the results. Moreover, it allows the use of smaller sample sizes, reducing the number of subjects required to reach statistical significance [51]. However, it is important to consider the disadvantages of this study design, such as anatomical variability, that may introduce a potential bias in the results, or ethical concerns, particularly if one of the two treatments is perceived to be less favorable. In addition, these studies generally require a longer follow-up period to monitor the effects of the treatments, which may pose problems in terms of patient compliance, especially for younger patients or those requiring extensive orthodontic procedures.

The present study exhibits several limitations: First, the sample included various dissimilarities: in size, ranging from 10 to 36 participants, but especially in terms of age, which ranged from 15 to 30 years. In patients still growing, RAP phenomena may behave differently.

Second, the follow-up periods, which ranged from 3 to 8 months, considering the type of study, are not long enough, which made it difficult to ensure that no further long-term complications were discovered. Furthermore, it is important to note that the surgical techniques presented in the included studies exhibit considerable variability. Despite these limitations, the positive results found in this study should be recognized for their potential benefits in clinical practice.

Future efforts should focus on conducting studies with larger and more homogeneous samples; follow-up periods should be extended over time, and it would be valuable to gather more information not only on the canine retraction phase but also on the total duration of the treatment.

Another effort should be directed toward the standardization of the surgical technique, as several variables currently exist. Additionally, the integration of digital planning tools, such as 3D imaging and artificial intelligence, into surgical workflows could enhance accuracy and reproducibility. Research could explore the impact of these technologies on patient outcomes and the standardization of procedures.

It would also be highly interesting for future research to focus on developing predictive models that account for patient-specific variables (e.g., bone density, age, or periodontal biotype) to personalize treatments and improve the predictability of outcomes.

5. Conclusions

Corticotomy and piezocision could effectively accelerate the retraction of the upper canines in extraction cases, resulting in a reduction in the overall duration of orthodontic treatment.

- -

- Corticotomy has been shown to be slightly more effective, with a rate of 1.5 to 4 times higher than conventional therapy.

- -

- Piezocision results in canine retraction that is 1.5 to 2 times faster than conventional treatment.

- -

- The two surgical techniques studied did not show statistically significant adverse effects on the periodontal ligament, molar anchorage loss, or root resorption.

- -

- Patients report experiencing mild to moderate pain, which is nonetheless regarded as tolerable.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/dj13020057/s1. Table S1, PRISMA 2020 Checklist; Table S2, Detailed Description of the Surgical Technique.

Author Contributions

E.L. was involved in the design of this systematic review, the literature search and article selection, data acquisition and analysis, and the drafting and revision of the manuscript, tables, and images; E.P. was involved in the design of the study, the literature search and article selection, and data acquisition and analysis; F.B. participated in the systematic review design, drafting, and revision of the manuscript; E.S. participated in the final proofreading of the article, study design, article selection, and drafting and revision of the manuscript and tables; A.V. and M.V. participated in article selection and the drafting and revision of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The review protocol was registered in PROSPERO CRD42024615824.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of the present systematic review are available within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Giannopoulou, C.; Dudic, A.; Pandis, N.; Kiliaridis, S. Slow and fast orthodontic tooth movement: An experimental study on humans. Eur. J. Orthod. 2016, 38, 404–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, A.J.; Songra, G.; Clover, M.; Atack, N.E.; Sherriff, M.; Sandy, J.R. Effect of gender and Frankfort mandibular plane angle on orthodontic space closure: A randomized controlled trial. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 2016, 19, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozdemir, F.; Tozlu, M.; Germec-Cakan, D. Cortical bone thickness of the alveolar process measured with cone-beam computed tomography in patients with different facial types. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2013, 143, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chugh, T.; Jain, A.K.; Jaiswal, R.K.; Mehrotra, P.; Mehrotra, R. Bone density and its importance in orthodontics. J. Oral Biol. Craniofac. Res. 2013, 3, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, G.R.; Schiffman, P.H.; Tuncay, O.C. Meta analysis of the treatment-related factors of external apical root resorption. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 2004, 7, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moradinejad, M.; Yazdi, M.; Mard, S.A.; Razavi, S.M.; Shamohammadi, M.; Shahsanaei, F.; Rakhshan, V. Efficacy of the systemic co-administration of vitamin D3 in reversing the inhibitory effects of sodium alendronate on orthodontic tooth movement: A preliminary experimental animal study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2022, 162, e17–e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abtahi, M.; Shafaee, H.; Saghravania, N.; Peel, S.; Giddon, D.; Sohrabi, K. Effect of corticosteroids on orthodontic tooth movement in a rabbit model. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2014, 38, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias, O.R.; Marquez-Orozco, M.C. Aspirin, acetaminophen, and ibuprofen: Their effects on orthodontic tooth movement. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2006, 130, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kharat, D.S.; Pulluri, S.K.; Parmar, R.; Choukhe, D.M.; Shaikh, S.; Jakkan, M. Accelerated Canine Retraction by Using Mini Implant With Low-Intensity Laser Therapy. Cureus 2023, 15, e33960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambevski, J.; Papadopoulou, A.K.; Foley, M.; Dalci, K.; Petocz, P.; Darendeliler, M.A.; Dalci, O. Physical properties of root cementum: Part 29. The effects of LED-mediated photobiomodulation on orthodontically induced root resorption and pain: A pilot split-mouth randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Orthod. 2022, 44, 650–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriphan, N.; Leethanakul, C.; Thongudomporn, U. Effects of two frequencies of vibration on the maxillary canine distalization rate and RANKL and OPG secretion: A randomized controlled trial. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 2019, 22, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frost, H.M. The regional acceleratory phenomenon: A review. Henry Ford Hosp. Med. J. 1983, 31, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kole, H. Surgical operations on the alveolar ridge to correct occlusal abnormalities. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1959, 12, 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.G. Corticision: A Flapless Procedure to Accelerate Tooth Movement. Front. Oral Biol. 2016, 18, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Park, Y.G.; Kang, S.G. Effects of Corticision on paradental remodeling in orthodontic tooth movement. Angle Orthod. 2009, 79, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, C.A.; Chandhoke, T.; Kalajzic, Z.; Flynn, R.; Utreja, A.; Wadhwa, S.; Nanda, R.; Uribe, F. Effect of corticision and different force magnitudes on orthodontic tooth movement in a rat model. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2014, 146, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dibart, S.; Sebaoun, J.D.; Surmenian, J. Piezocision: A minimally invasive, periodontally accelerated orthodontic tooth movement procedure. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 2009, 30, 342–350. [Google Scholar]

- Dibart, S. Piezocision™: Accelerating Orthodontic Tooth Movement While Correcting Hard and Soft Tissue Deficiencies. Front. Oral Biol. 2016, 18, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wazwaz, F.; Seehra, J.; Carpenter, G.H.; Papageorgiou, S.N.; Cobourne, M.T. Duration of canine retraction with fixed appliances: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2023, 163, 154–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A Coefficient of Agreement for Nominal Scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, N.H.; Sabet, N.E.; Hassan, I.T. Evaluation of corticotomy-facilitated orthodontics and piezocision in rapid canine retraction. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2016, 149, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboul-Ela, S.M.; El-Beialy, A.R.; El-Sayed, K.M.; Selim, E.M.; El-Mangoury, N.H.; Mostafa, Y.A. Miniscrew implant-supported maxillary canine retraction with and without corticotomy-facilitated orthodontics. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2011, 139, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksakalli, S.; Calik, B.; Kara, B.; Ezirganli, S. Accelerated tooth movement with piezocision and its periodontal-transversal effects in patients with Class II malocclusion. Angle Orthod. 2016, 86, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfawal, A.M.H.; Hajeer, M.Y.; Ajaj, M.A.; Hamadah, O.; Brad, B. Evaluation of piezocision and laser-assisted flapless corticotomy in the acceleration of canine retraction: A randomized controlled trial. Head Face Med. 2018, 14, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Naoum, F.; Hajeer, M.Y.; Al-Jundi, A. Does alveolar corticotomy accelerate orthodontic tooth movement when retracting upper canines? A split-mouth design randomized controlled trial. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 72, 1880–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqadasi, B.; Xia, H.Y.; Alhammadi, M.S.; Hasan, H.; Aldhorae, K.; Halboub, E. Three-dimensional assessment of accelerating orthodontic tooth movement-micro-osteoperforations vs. piezocision: A randomized, parallel-group and split-mouth controlled clinical trial. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 2021, 24, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakr, A.R.; Nadim, M.A.; Sedky, Y.W.; El Kady, A.A. Effects of Flapless Laser Corticotomy in Upper and Lower Canine Retraction: A Split-mouth, Randomized Controlled Trial. Cureus 2023, 15, e37191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eid, F.Y.; El-Kalza, A.R. The effect of single versus multiple piezocisions on the rate of canine retraction: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, V.M.; Papadopoulou, A.K.; Wong, M.; Pandis, N.; Dalci, O.; Darendeliler, M.A. The effect of piezocision vs. no piezocision on maxillary extraction space closure: A split-mouth, randomized controlled clinical trial. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2022, 16, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahanbakhshi, M.R.; Motamedi, A.M.; Feizbakhsh, M.; Mogharehabed, A. The effect of buccal corticotomy on accelerating orthodontic tooth movement of maxillary canine. Dent. Res. J. 2016, 13, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, S.C.; Praharaj, K.; Barik, A.K.; Patnaik, K.; Mahapatra, A.; Mohanty, D.; Katti, N.; Mishra, D.; Panda, S.M. Retraction With and Without Piezocision-Facilitated Orthodontics: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2020, 40, e19–e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raza, M.; Sharma, P.; Kumar, P.; Vaish, S.; Pathak, B. Comparison of canine retraction by conventional and corticotomy-facilitated methods: A split mouth clinical study. J. Orthod. Sci. 2021, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Gupta, S.; Ahuja, S.; Bhambri, E.; Sharma, R. Does corticotomy accelerate canine retraction with adequate anchorage control? A split mouth randomized controlled trial. Orthod. Waves 2020, 79, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toodehzaeim, M.H.; Maybodi, F.R.; Rafiei, E.; Toodehzaeim, P.; Karimi, N. Effect of laser corticotomy on canine retraction rate: A split-mouth randomized clinical trial. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfailany, D.T.; Hajeer, M.Y.; Al-Bitar, M.I.; Alsino, H.I.; Jaber, S.T.; Brad, B.; Darwich, K. Effectiveness of Flapless Cortico-Alveolar Perforations Using Mechanical Drills Versus Traditional Corticotomy on the Retraction of Maxillary Canines in Class II Division 1 Malocclusion: A Three-Arm Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Cureus 2023, 15, e44190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, P.; Ingervall, B. A clinical study of maxillary canine retraction with a retraction spring and with sliding mechanics. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1989, 2, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benetti, M.; Montresor, L.; Cantarella, D.; Zerman, N.; Spinas, E. Does Miniscrew-Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion Influence Upper Airway in Adult Patients? A Scoping Review. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdecchia, A.; Suárez-Fernández, C.; Miquel, A.; Bardini, G.; Spinas, E. Biological Effects of Orthodontic Tooth Movement on the Periodontium in Regenerated Bone Defects: A Scoping Review. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Russo, L.; Zhurakivska, K.; Montaruli, G.; Salamini, A.; Gallo, C.; Troiano, G.; Ciavarella, D. Effects of crown movement on periodontal biotype: A digital analysis. Odontology 2018, 106, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepedino, M.; Esposito, R.; Potrubacz, M.I.; Xhanari, D.; Ciavarella, D. Evaluation of the relationship between incisor torque and profile aesthetics in patients having orthodontic extractions compared to non-extractions. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 5233–5248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatrom, A.A.; Zawawi, K.H.; Al-Ali, R.M.; Sabban, H.M.; Zahid, T.M.; Al-Turki, G.A.; Hassan, A.H. Effect of piezocision corticotomy on en-masse retraction. Angle Orthod. 2020, 90, 648–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, S.; Hassan, N.; Mazhar, S.; Anjan, R.; Anand, B. Comparison of the Efficiency and Treatment Outcome of Patients Treated with Corticotomy-Assisted En masse Orthodontic Retraction with the En masse Retraction without Corticotomy. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2021, 13, S1320–S1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, M.R.; Hajeer, M.Y.; Burhan, A.S.; Heshmeh, O.; Alam, M.K. The effectiveness of minimally-invasive corticotomy-assisted orthodontic treatment of palatally impacted canines compared to the traditional traction method in terms of treatment duration, velocity of traction movement and the associated dentoalveolar changes: A randomized controlled trial. F1000Research 2023, 12, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Xu, G.; Yang, C.; Xie, Q.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, S. Efficacy of the technique of piezoelectric corticotomy for orthodontic traction of impacted mandibular third molars. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 53, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Areqi, M.M.; Abu Alhaija, E.S.; Al-Maaitah, E.F. Effect of piezocision on mandibular second molar protraction. Angle Orthod. 2020, 3, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhaija, E.S.A.; Al-Areqi, M.M.; Maaitah, E.F.A. Comparison of second molar protraction using different timing for piezocision application: A randomized clinical trial. Dent. Press J. Orthod. 2022, 4, e2220503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, B.M.; Dalci, O.; Darendeliler, M.A.; Papadopoulou, A.K. Corticotomies and Orthodontic Tooth Movement: A Systematic Review. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 3, 453–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.H.; Park, W.J.; Park, J.B. Comparative Efficacy of Traditional Corticotomy and Flapless Piezotomy in Facilitating Orthodontic Tooth Movement: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina 2023, 10, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesaffre, E.; Philstrom, B.; Needleman, I.; Worthington, H. The design and analysis of split-mouth studies: What statisticians and clinicians should know. Stat. Med. 2009, 28, 3470–3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).