Abstract

This paper introduces a vanadium dioxide-integrated broadband metamaterial absorber designed for the terahertz frequency range. The simulation results for the proposed structure demonstrate a wide 90% absorption bandwidth of 8.23 THz, corresponding to a fractional bandwidth of 89.5%. By leveraging the phase-transition properties of VO2, the absorber demonstrated dynamic adjustability by modulating the absorption from 3% to 98.74%. The absorption mechanism was analyzed through the impedance matching theory and electromagnetic field distributions, confirming the role of magnetic resonance and interference. Furthermore, machine learning algorithms, specifically Linear Regression, Support Vector Regression, and Random Forest (RF), were applied to accelerate the design process and optimize the structural parameters. Among these, the RF model demonstrated superior prediction accuracy. The machine learning-assisted optimization successfully extended the effective absorption bandwidth to 9 THz, representing an improvement by 9.4% compared to the traditional optimization methods. These results validate the efficacy of combining electromagnetic simulation with data-driven techniques for advanced metamaterial design.

1. Introduction

In the rapidly evolving landscape of modern technology, electromagnetic absorbers stand as critical components across diverse applications, from enhancing sensing systems [1,2] to optimizing emitters [3,4], and advancing thermophotovoltaic energy conversion [5,6]. In this technological area, metamaterials have emerged as a groundbreaking innovation, drawing intense research interest and practical implementation due to their extraordinary capability for perfect electromagnetic absorption [7].

Unlike conventional materials, metamaterials yield their exceptional properties from precisely engineered subwavelength architectures that create resonant interactions with both electric and magnetic field components of incident electromagnetic waves [8]. These sophisticated structures consist of carefully designed “meta-atoms”—artificial electromagnetic building blocks that typically take the form of metallic split-ring resonators, intricately patterned wire meshes, complementary geometric arrangements, or other optimized configurations meticulously fabricated on dielectric substrates or embedded within them. The inherent versatility of metamaterial design enables unprecedented control over absorption frequency, bandwidth, and angular response, opening new possibilities for electromagnetic wave management across the entire spectrum from microwave to optical frequencies [9,10].

Practical applications of metamaterial absorbers not only demand high absorption rates but must also meet other criteria, such as broad bandwidth. Recent research on broadband absorbers has employed complex geometries [11], nano holes [12], or even graphene [13] to obtain these objectives. However, the use of composite materials is the most popular method to meet the requirements. As can be seen from the research by Chouhan et al., the proposed design offers an ultra-broadband bandwidth combined with the capability to modulate ultra-wideband THz amplitude caused by metal–insulator phase transitions in vanadium oxide thin films [14].

Furthermore, metamaterial structures can be modified through numerous design parameters to meet diverse requirements. The challenge lies in the complex relationship between design parameters and electromagnetic responses. Adjusting these parameters to achieve target responses essentially constitutes an optimization process that is time-consuming and labor-intensive. In recent years, machine learning (ML) has found applications across many fields thanks to its capability to learn from data, detect hidden features, and establish relationships between datasets [15].

This study numerically investigates a broadband metamaterial absorber (BMA) unit cell incorporating a VO2 square patch to achieve dynamically tunable absorption characteristics across the THz regime. The investigated absorber not only offers the ability to adjust the absorption by changing the temperature-dependent conductivity of VO2, but also features a simple configuration, thereby facilitating the fabrication process. Additionally, this work employs machine learning techniques to predict the absorption characteristics of the designed structure. Furthermore, it provides a comparison of different ML regressions and optimizes the geometric parameters.

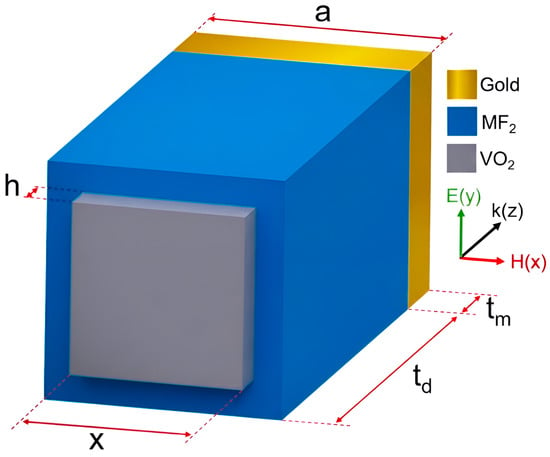

2. Design and Simulation

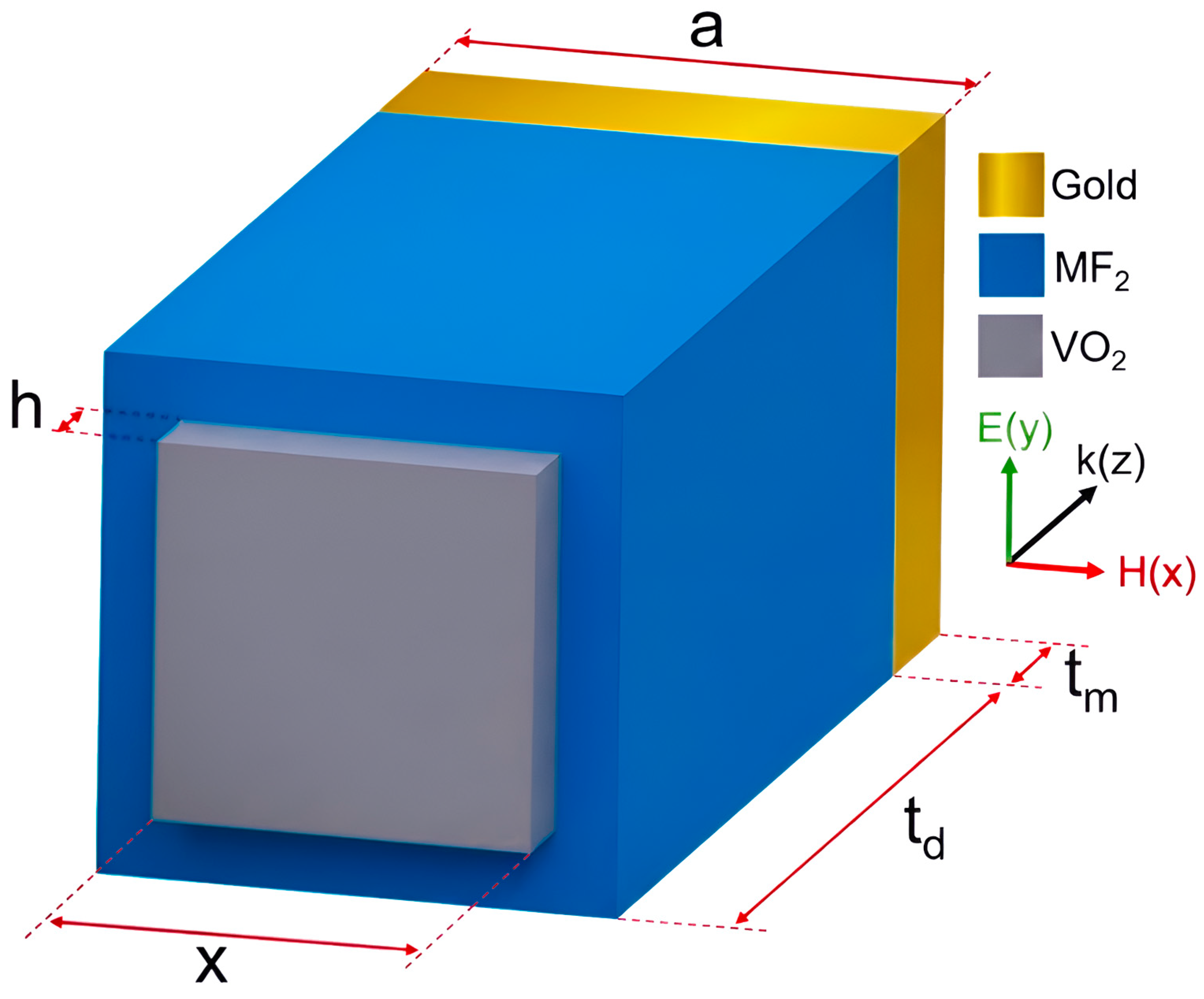

The unit cell of the proposed absorber is shown in Figure 1, including three layers: VO2–dielectric MF2–Au. The top layer is made up of VO2, which has a relative permittivity in the THz range, described by the Drude model [16]:

where denotes the angular frequency of the incident electromagnetic wave, = is the permittivity at very high frequencies, is the plasma frequency of VO2, and γ = is the collision frequency constant. The relationship between and can be expressed as

with = and = . Upon exceeding a critical temperature of 68 °C, VO2 undergoes a phase transition of insulator to a metallic state. When the metallic volume fraction is relatively large, the reduced spacing between particles makes inter-particle interactions significant. To be more specific, the dielectric constant of VO2 can be expressed by the simple Bruggeman theory [17]:

with = 9 of the VO2 thin film dielectric function in the insulator state. is the permittivity of the metallic components in VO2, expressed by the Drude model. Moreover, volume fraction of metal components can be explained by [18]

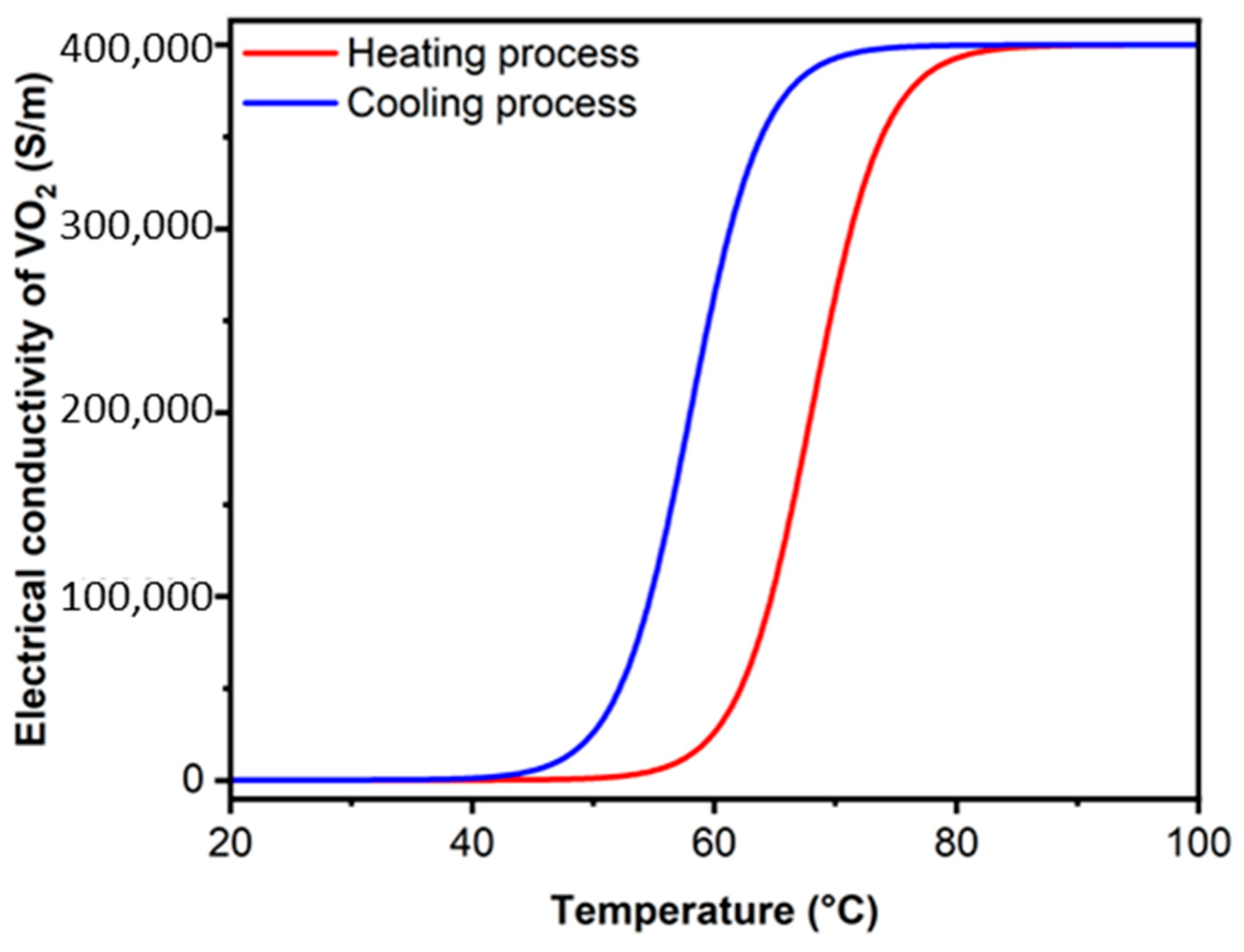

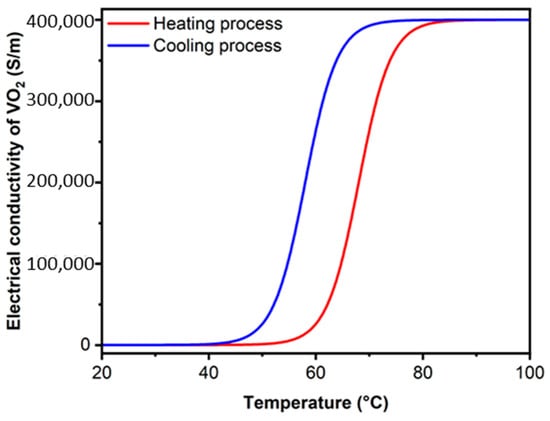

where T0 = 68 °C is the phase transition temperature of VO2 and ∆T = 3 °C is the transition width [19]. From Equations (3) and (4), the conductivity of VO2 can be expressed as Furthermore, previous research demonstrated that the conductivity of VO2 could be varied from 10 to 400,000 S/m through temperature adjustment [20]. The relationship between temperature and conductivity of VO2 is demonstrated in Figure 2 through theoretical calculations. However, our study focuses on the change in VO2 conductivity ranging from 200 S/m at 318 K to 200,000 S/m at 341 K.

Figure 1.

3D schematic of the metamaterial structure with directions of the magnetic field, electric field, and wave vector.

Figure 2.

Temperature-dependent electrical conductivity of VO2 film (heating process T0 = 68 °C, and cooling process T0 = 58 °C).

The middle dielectric is MF2, a non-dispersive medium with a permittivity of 1.9 [21]. The metallic ground is made of gold, and its dielectric constant is characterized by the Drude model [22]:

where represents the permittivity of free space, is the plasma frequency of Au, and = is the damping rate. The simulation process was performed by using CST Studio Suite software 2023, with the structural parameters listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameters of the proposed unit cell.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Electromagnetic Characteristics of VO2-Integrated Broadband Absorption Materials

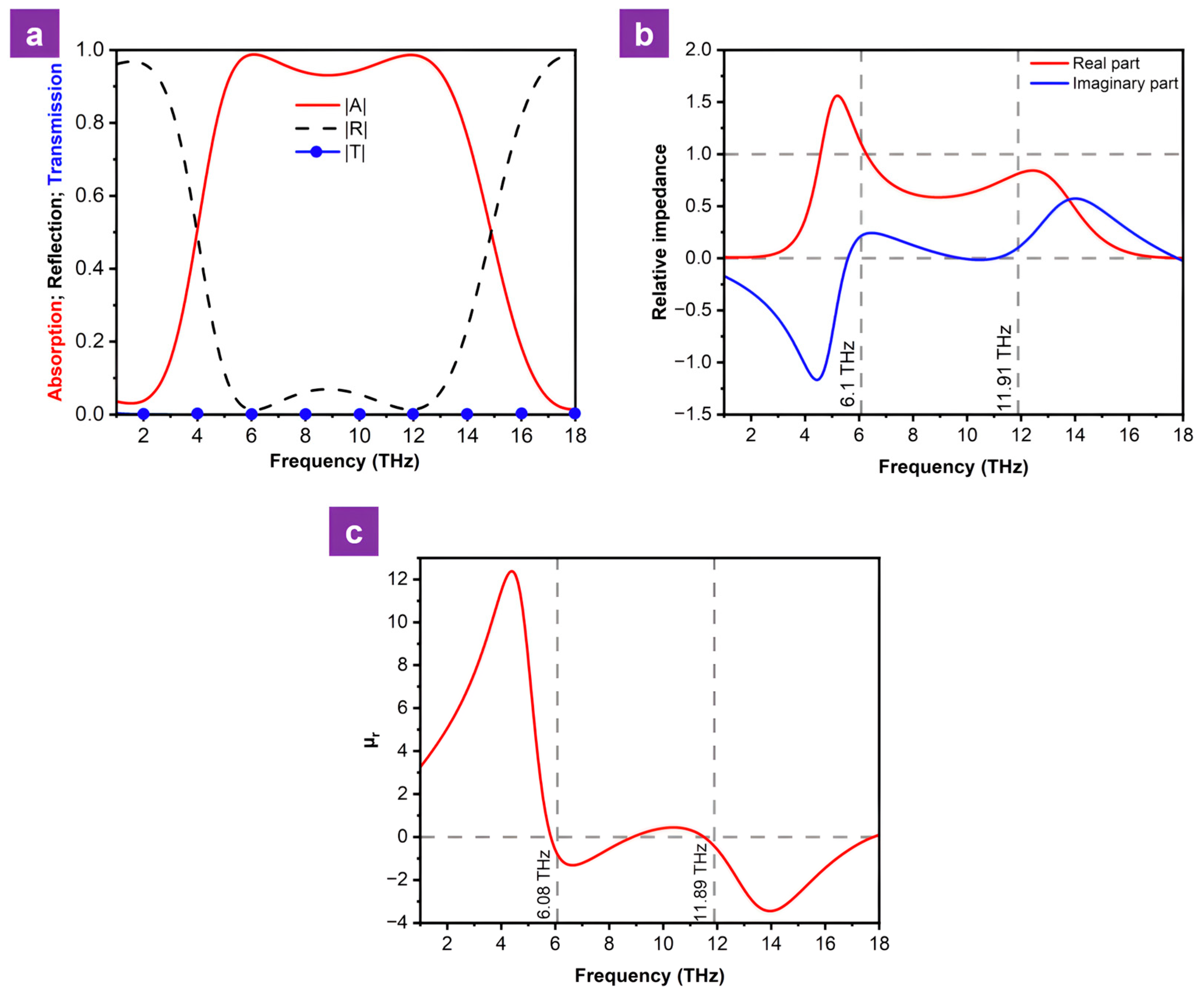

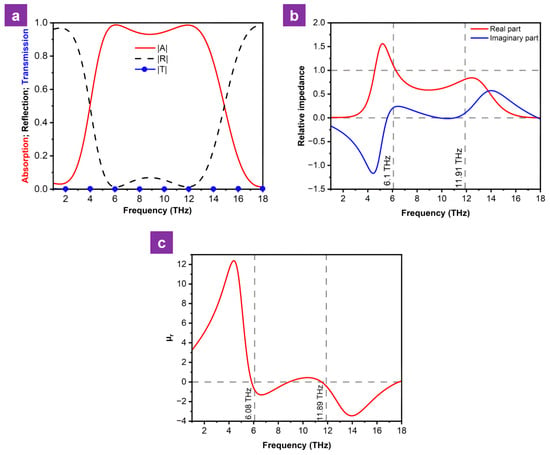

The simulated absorption, transmission, and reflection spectra of the BMA material at a conductivity of 200,000 S/m are illustrated in Figure 3a. The results exhibit two distinct absorption peaks at 6.1 and 11.91 THz, with absorption of 98.74% and 98.62%, respectively. Furthermore, the absorption bandwidth exceeding 90% is 8.23 THz, from 5.08 to 13.31 THz.

Figure 3.

(a) Absorption, reflection, and transmission spectra, (b) relative impedance and (c) real part of the permeability at VO2 conductivity of 200,000 S/m.

In addition, the relative bandwidth (RAB) is considered a quantity for comparing the broadband electromagnetic absorption performance of different BMA structures, regardless of their operating frequency ranges. It can be calculated by using the following formula:

where and denote the upper and lower cutoff frequencies, respectively, at which the absorption remains above a specified threshold. For the investigated BMA structure, with the absorption threshold set at 89.5%, an RAB of 90% is obtained. As shown in Table 2, this represents a superior performance for a simple three-layer structure that is highly effective in broadband absorption.

Table 2.

Comparison of the proposed model with recent investigations.

The physical mechanism governing the electromagnetic absorption characteristics of the designed structure can be elucidated by employing the impedance matching theory. When electromagnetic waves propagate to the surface of a material, a portion of the energy is reflected into the free space, another fraction is transmitted through, and the remaining energy is absorbed by the material. The absorption of the investigated model is calculated by using the following equation:

where and represent the transmission and reflection, respectively. In this configuration, the continuous metal layer at the bottom serves to completely block the transmission of electromagnetic waves. Consequently, to maximize absorption, the reflection coefficient of the incident wave must be minimized. When the transmission is neglected, the relationship between the absorption and the impedance of the material is expressed by the formula below:

Here, is the absolute impedance of the designed structure, is the impedance of the free space and can be calculated through permeability and permittivity : . Additionally, the relative impedance can be expressed as [27]

When the relative impedance approaches unity, the reflection nearly vanishes, thereby the optimal absorption of the proposed material is achieved. Based on the relative impedance calculated by Equation (9) and presented in Figure 3b, it can be observed that in a frequency range from 5.08 to 13.31 THz, the real part of the relative impedance varies between 1.5 and 0.5, while the imaginary part ranges from −0.8 to 0.3. Specifically, at 6.1 THz, the real and imaginary parts of are 1.08 and 0.22, respectively, whereas at 11.91 THz these values are 0.81 and 0.1, respectively. These results demonstrate that, within the 5.08–13.31 THz band, the impedance of the material approximates that of the surrounding medium. Consequently, only a minimal fraction of the electromagnetic wave is reflected at the top interface, and transmission through the material is virtually nonexistent, as clearly evidenced by the transmission and reflection spectra in Figure 3a.

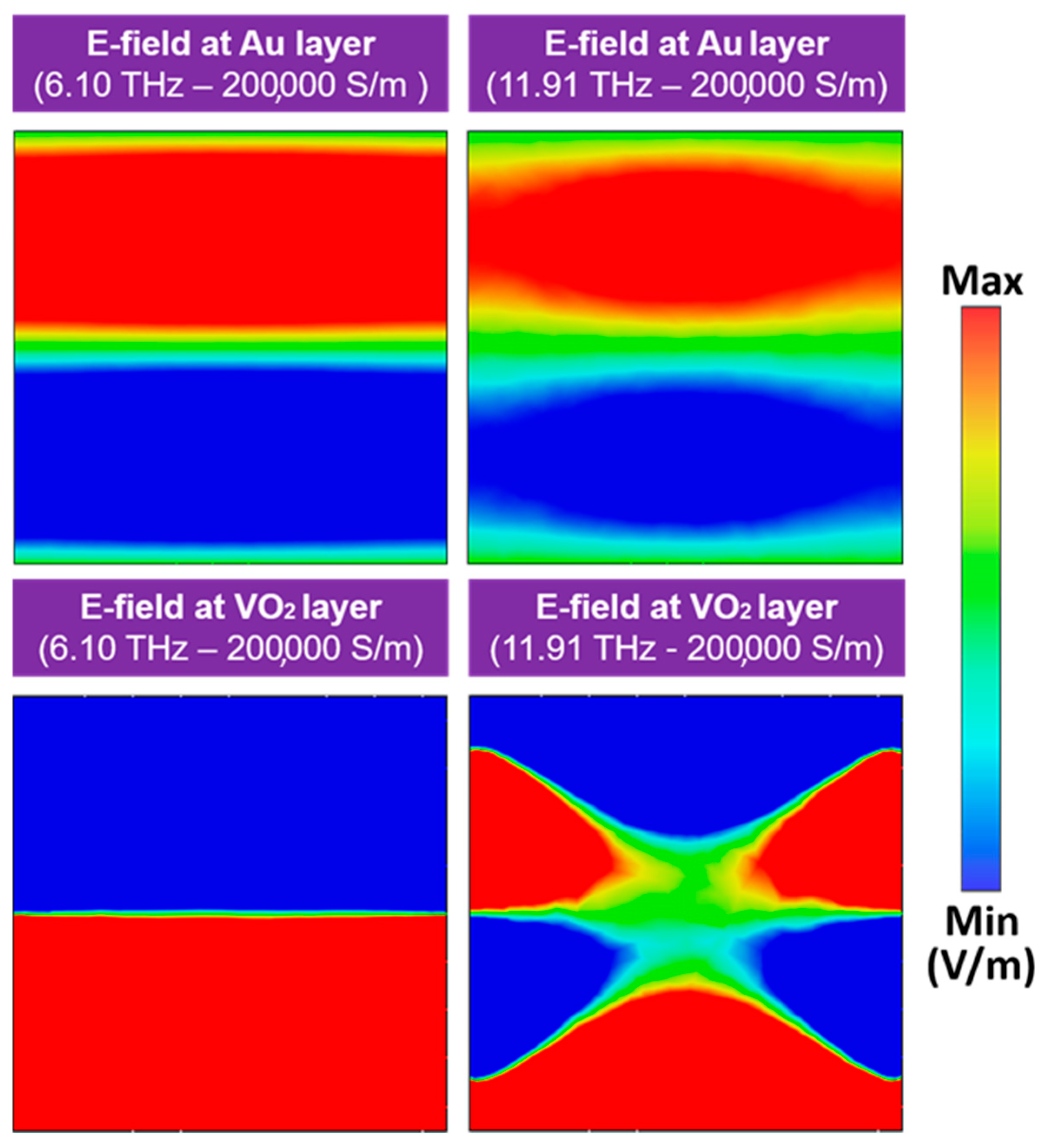

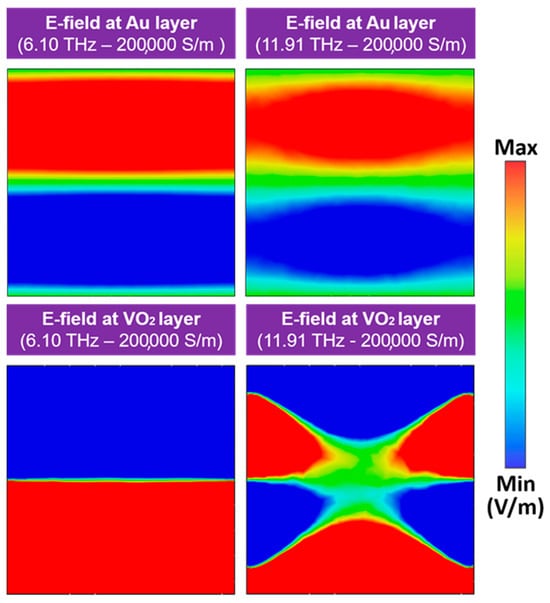

To further elucidate the resonance mechanism of the BMA, the electric field distributions on the surfaces of the Au and VO2 layers when VO2 is in the metallic phase are illustrated at the resonant frequencies of 6.1 and 11.91 THz in Figure 4. The simulation results indicate that, at 6.1 THz, the electric field vectors on the surfaces of the two layers are anti-parallel. Meanwhile, at 11.91 THz, the VO2 layer exhibits three distinct regions where the electric field directions in adjacent zones are opposite. By correlating these electric field distributions with the calculated real part of the magnetic permeability presented in Figure 3c, it can be concluded that magnetic resonance is the primary origin of the two observed absorption peaks [28].

Figure 4.

Electric field distribution on the Au layer and the VO2 one at a conductivity of 200,000 S/m for two resonance frequencies: 6.10 and 11.91 THz.

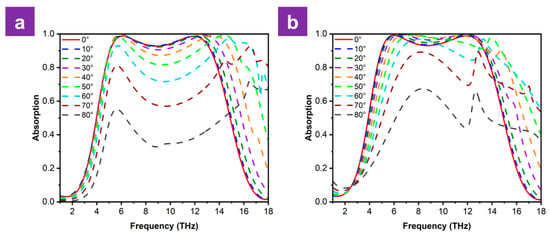

The incident angle of electromagnetic waves significantly influences the performance of metamaterial absorbers. Consequently, we simulated the effects of both TE and TM polarizations at varying incident angles on the absorption spectra. In general, the absorption peaks exceeding 90% exhibit significant angular stability, remaining largely insensitive to the incident angle for values up to 60°, while the broadband absorption performance remains stable for incidence angles up to 30° under TE polarization and extends to 40° for the TM mode. As can be seen in Figure 5, when the incidence angle increases further to 80° for both polarization modes, the absorption peaks in the TM mode are significantly better preserved than those in the TE mode. This superior stability is attributed to the inherent magnetic resonance nature of the peaks, which remains more robust under TM excitation.

Figure 5.

Performance of the absorber under (a) TE and (b) TM polarization.

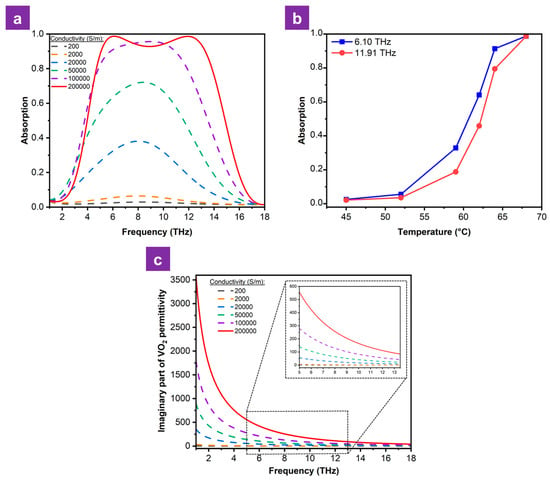

To investigate the influence of the phase-change material VO2 on the electromagnetic properties of the BMA structure, the absorption spectrum was simulated across different VO2 conductivities. As illustrated in Figure 6a, increasing the VO2 conductivity from 200 to 200,000 S/m results in a variation in absorption changing from 3% to 98.74%, with the center frequency remaining nearly unchanged. Moreover, Figure 6b demonstrates that the absorption characteristics of the metamaterial can be actively controlled through thermal regulation of the VO2 layer. By modulating the temperature, the device can be effectively switched from a transparent state to a near-perfect absorbing one, demonstrating high sensitivity to the VO2 phase transition. The observed phenomenon is due to the dependence of the dielectric constant of VO2 on its electrical conductivity. Based on Equations (1) and (2), the imaginary part of the dielectric constant VO2 for different conductivities is shown in Figure 6c. It can be seen that, as the conductivity of VO2 increases, the imaginary part of the dielectric constant also increases sharply in its magnitude, and the energy loss density is expressed by the following equation [29]:

with and are the angular frequency and electric field intensity of the incident wave, respectively. According to the expression above, the energy loss density is directly proportional to the imaginary part of the dielectric constant, which explains why, when VO2 gradually transitions to the metallic phase; thereby, the overall absorption of the designed metamaterial is enhanced.

Figure 6.

(a) Absorption spectra and (c) imaginary parts of the dielectric constant of VO2 at different conductivity levels. (b) Temperature-dependent absorption for the resonance peaks of 6.10 and 11.91 THz.

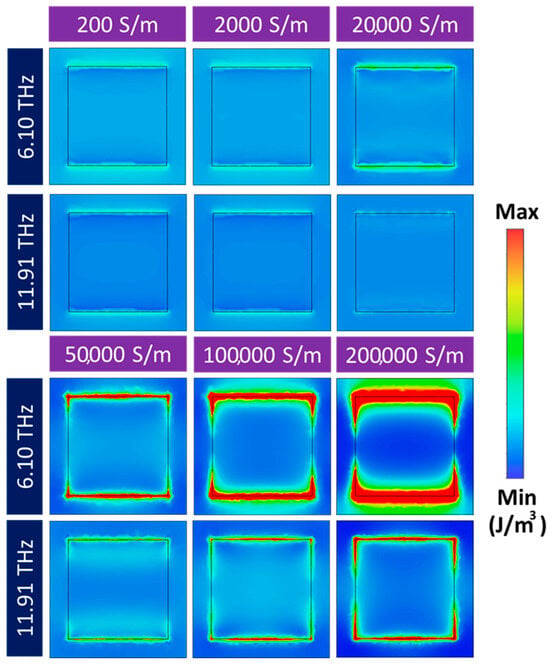

The electric field energy density for different conductivities of VO2 at 6.1 and 11.91 THz was simulated to understand the mechanism of switching between reflection and absorption of the investigated structure, which is shown in Figure 7. When VO2 is in the insulator phase, specifically at conductivity values of 200 S/m, 2000 S/m, and 20,000 S/m, the electric field energy density remains low and distributes almost uniformly. This indicates that no resonance occurs at these conductivities, where the investigated structure primarily acts as a reflector. As can be seen, when VO2 transitions to the metallic phase, the electric field energy is strongly concentrated at the edges of the square, especially the top and bottom edges of the VO2 layer. This simulation result demonstrates that, when the conductivity of VO2 is 200,000 S/m, there are more free electrons in the VO2 layer, and these electrons oscillate under the excitation of the incident electromagnetic wave, leading to the generation of surface currents. This phenomenon forms resonance peaks at two frequencies, 6.10 and 11.91 THz, which helps to increase the performance of absorbers.

Figure 7.

Simulated electric field energy density at frequencies of 6.10 and 11.91 THz for different electrical conductivities of VO2.

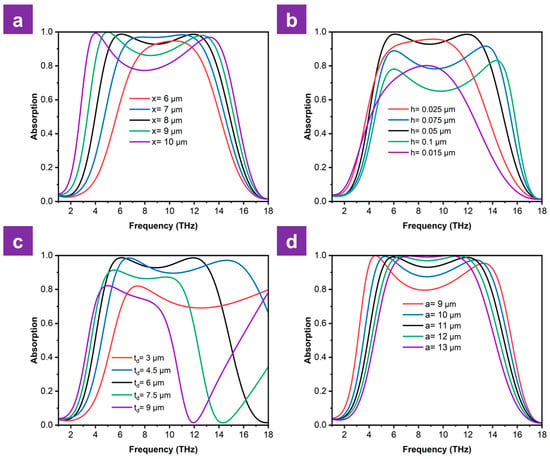

The performance of an absorber is highly sensitive to its geometric parameters; therefore, parameter optimization is crucial in obtaining the optimal performance. Figure 6 illustrates the influence of structural parameters on the absorption spectrum at a conductivity of 200,000 S/m. Figure 8a reveals that increasing the width x from 6 to 8 µm broadens the absorption bandwidth and increases the maximum absorption toward unity. As the width x continues to increase to 10 µm, the first resonance peak gradually shifts towards a lower frequency, whereas the second one experiences a blue shift. Although these shifts result in a broadening of the absorption spectrum, they lead to a degradation in absorption within the central frequency region, causing the structure to lose its broadband absorption characteristic. Thus, x = 8 µm is chosen as the optimum value.

Figure 8.

Variation in absorption spectra according to (a) VO2 layer size, (b) VO2 layer thickness, (c) dielectric layer thickness and (d) unit cell period.

Subsequently, the simulation results for different thicknesses of the VO2 layer are shown in Figure 8b. As the dielectric layer thickness h changes from 0.015 µm to 0.05 µm, both the absorption and the absorption spectrum are gradually enhanced. While the resonance peaks remain stable as the thickness increases up to 0.1 µm, the absorption itself exhibits a decline. This is caused by the degradation of impedance matching between the investigated structure and free space. Therefore, 0.05 µm is identified as the optimum thickness to guarantee the near-perfect impedance matching.

The absorption spectrum of the absorber depends on the dielectric layer thickness, as shown in Figure 8c. The simulation results show that, while the position of the first resonance peak remains almost unchanged, the second one exhibits red shifts as the dielectric layer thickness increases. For an optimized dielectric thickness of 6 µm, the center frequency of the absorption spectrum is approximately 9.19 THz, corresponding to a vacuum wavelength of 32.64 µm. Because the refractive index of the dielectric layer is , the wavelength in the dielectric layer decreases to approximately 23.82 µm. This absorption mechanism can be explained by the interference cancellation principle. When the dielectric layer thickness is approximately one-quarter of the wavelength in the dielectric layer, it satisfies the condition of canceling interference between the reflected and incident waves, allowing the proposed structure to obtain a broadband absorption of over 90%. As a result, the absorber shows strong absorption at this specific thickness.

As the unit cell period a of the metamaterial increases from 9 to 13 µm, the absorption spectrum demonstrates a clear trade-off between bandwidth and absorption stability above the 90% threshold, shown in Figure 8d. At the smallest period (a = 9 µm), the structure fails to maintain a continuous 90% absorption, since a significant dip occurs in the center of the band where absorption falls to approximately 80%. A gradual increase in the unit cell period causes the first resonance peak to exhibit a blueshift, whereas the other peak exhibits a redshift. This phenomenon initially facilitates a broadband absorption capability within the structure. However, as the period is further increased up to 13 µm, this trend persists, ultimately leading to a contraction of the bandwidth where absorption exceeds 90%. As evidenced in Figure 8d, a unit cell period of 11 µm yields the optimal bandwidth for high-efficiency absorption.

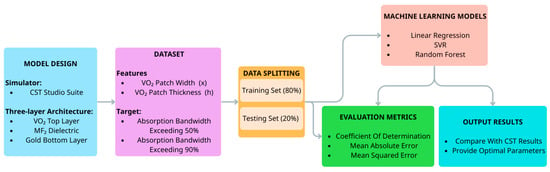

3.2. Machine Learning Prediction Results

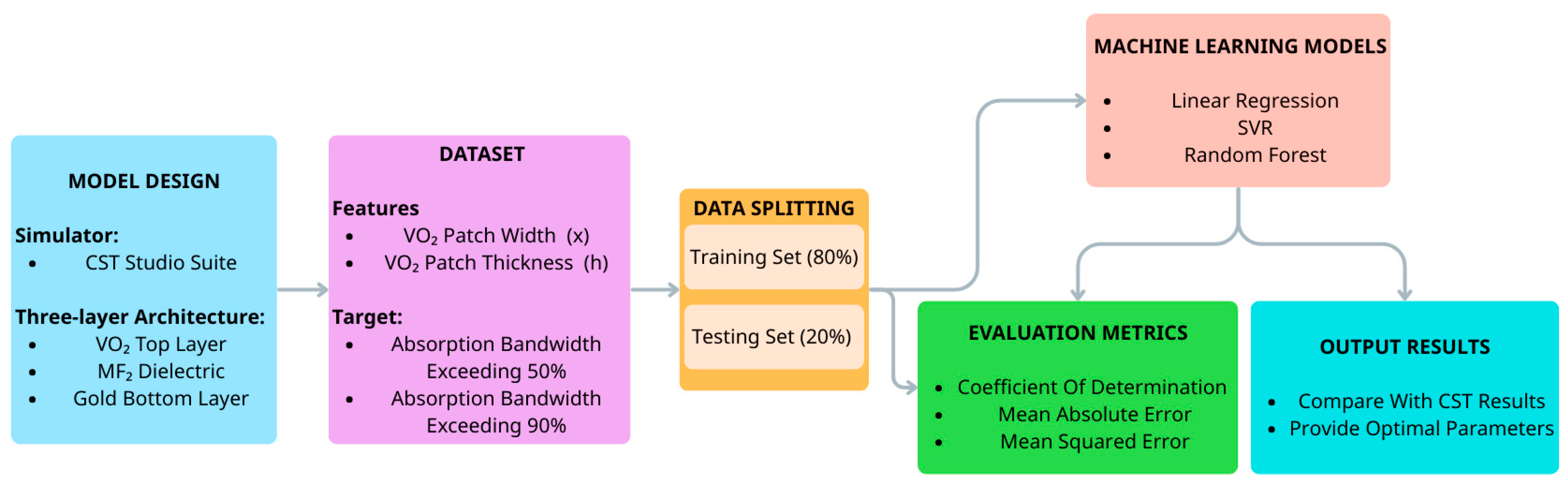

Figure 9 illustrates the process of using an ML model trained by a dataset consisting of 2010 data points. This process began with simulating and exporting data from CST software, followed by labeling and scaling the data. After preprocessing, the dataset was split into a test sample (20%) and a training one (80%). Finally, the results predicted by the ML model are compared with the simulation results by CST. To clarify, the 2010 data points were generated by using a parametric sweep sampling strategy via CST simulations. The parameter space was covered uniformly to avoid any sample imbalance. Specifically, the parameter x was sampled to be 1 to 11 µm with a step size of 0.05 µm (201 points), and the parameter h was sampled from 0.01 to 0.1 µm with a step size of 0.01 µm (10 points). Three regression models were used: Linear Regression (LR), Support Vector Regression (SVR), and Random Forest (RF). LR was employed as a baseline to evaluate the linearity of the design space. For SVR, a radial basis function kernel and an -insensitive loss function were utilized to capture non-linear characteristics, while the RF model was trained by minimizing the mean squared error loss function. To ensure optimal predictive accuracy and prevent overfitting, a grid search strategy was performed for hyperparameter optimization. Model performance was rigorously evaluated by using the coefficient of determination, mean absolute error, and mean squared error. The targets are the absorption bandwidth with absorption above 50% and 90%.

Figure 9.

Flow chart showing the workflow of the proposed study.

Based on evaluation metrics including R2, MAE and MSE shown in Table 3, it is possible to provide a comprehensive assessment of the performance of three ML models. Among the three algorithms, the Linear Regression model exhibits the worst performance. Specifically, R2 values on the test set reach only approximately 0.855 and 0.280 for predicting the absorption bandwidth exceeding 50% and 90%, respectively. Moreover, the error parameters for both output results are also relatively high, with MAE values of nearly 1.48 and 1.46, and MSE values of around 3.79 and 4.26 on the test set. In contrast, the SVR model presents significantly better performance than the LR model, with the R2 values on the test set improving strongly, reaching 0.987 and 0.981 for the two target variables. Furthermore, both MAE and MSE values on the test set decrease substantially, demonstrating a superior capability in modeling non-linear features.

Table 3.

Evaluation metrics for ML models. MAE is the mean absolute error, and MSE is the mean squared error.

However, RF outperformed the others. R2 values on the testing dataset approach unity for both output results, and the error metrics are all less than 0.06, indicating high predictive accuracy and robust generalization capability. Notably, the minimal divergence between the evaluation parameters on the training and test sets, as presented in Table 4, illustrates that the model effectively mitigates overfitting. This advantage is attributed to the nature of the RF algorithm, which aggregates predictions from multiple decision trees, thereby reducing variance and enhancing model stability.

Table 4.

Comparison of R2, MAE and MSE values on training and validating dataset for RF model.

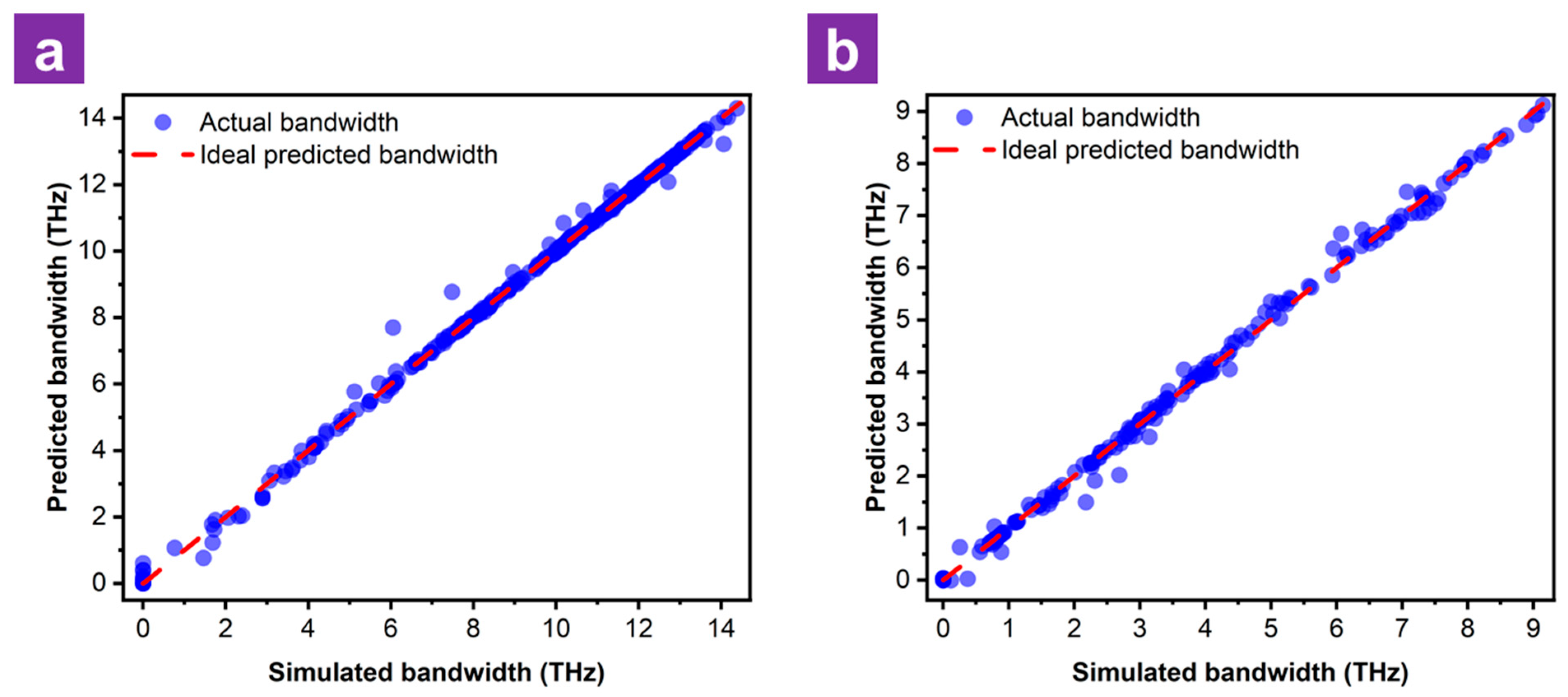

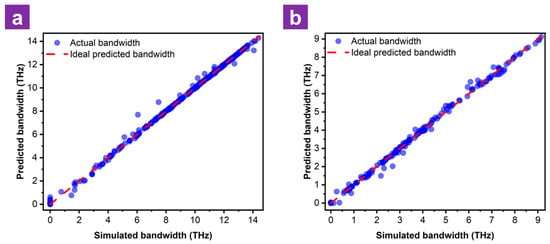

To evaluate the accuracy of the proposed ML approach, we analyzed the relationship between the predicted outcomes and the simulated results in the testing dataset. Figure 10 illustrates the scatter plots for the absorption bandwidths at the 50% and 90% thresholds. The tight alignment of the test samples along the diagonal line confirms that the RF effectively captures the non-linear relationship between the geometric parameters and absorption performance. To further clarify the actual accuracy of the model by using the RF algorithm, the prediction results are compared with some simulation results (not included in the test set) by employing the CST software, and are shown in Table 5. Based on the comparison table of the simulation and prediction results, the RF model shows fairly high accuracy in most cases, with relatively small errors. In particular, the model predicts with absolute accuracy in cases where the absorption bandwidth is 0 THz.

Figure 10.

Scatter plots of RF show the relationship between the predicted and simulated values (blue dots) of (a) absorption bandwidth above 50% and (b) absorption bandwidth above 90% in the testing dataset. The red dashed line represents the ideal fit of the absorption bandwidth.

Table 5.

Comparison of simulated and predicted values by using CST software and RF model, respectively.

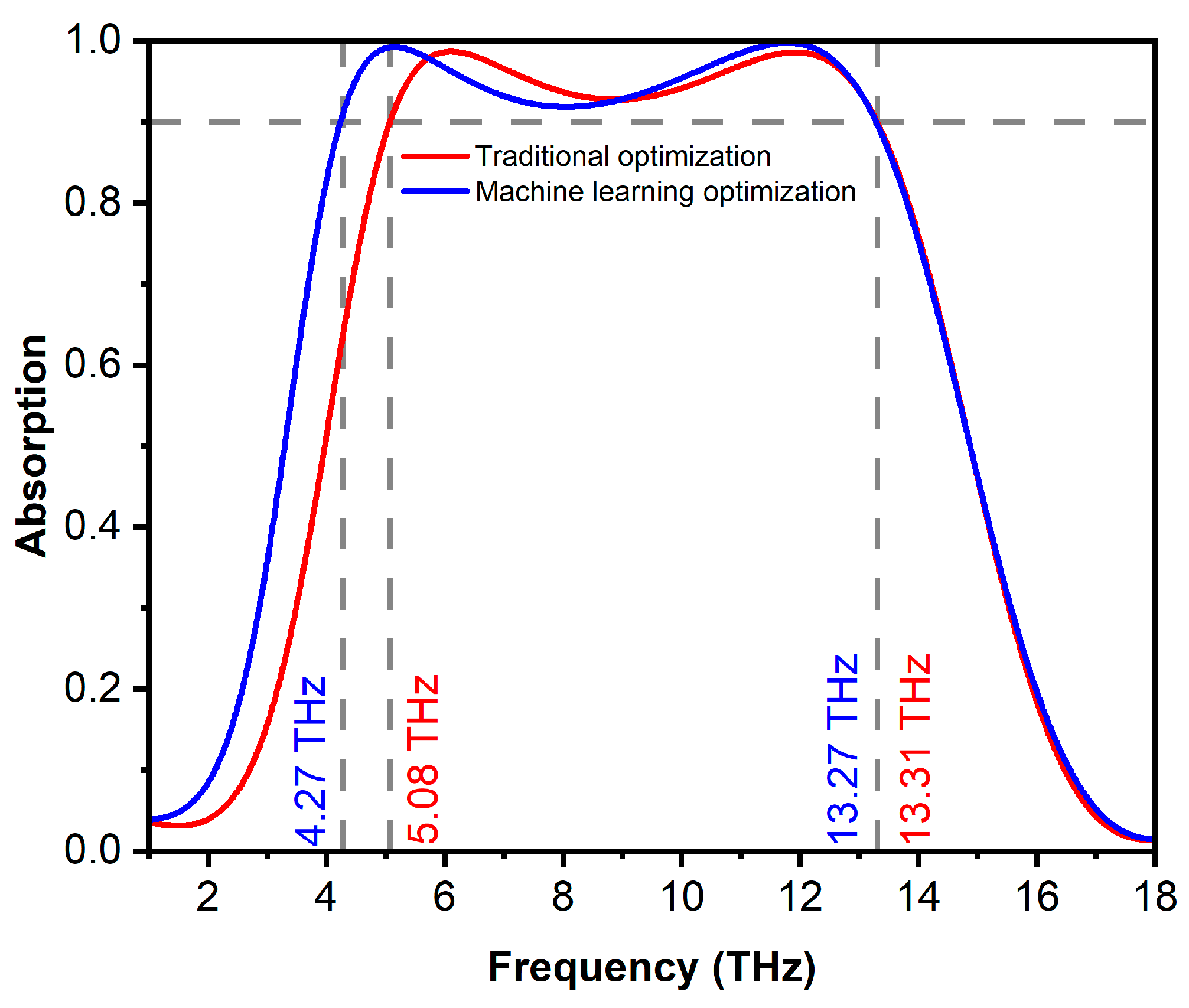

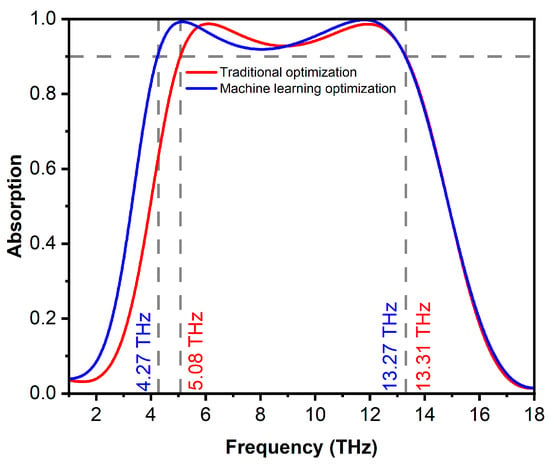

After successfully training the RF model, a grid of input values is generated to find the optimal parameters. To be more specific, the predicted results are analyzed to identify the pair of structure parameters reaching the maximal absorption bandwidth above 90%. The obtained parameters are x = 8.96 µm and h = 0.04 µm, corresponding to a predicted bandwidth of 9.19 THz. As shown in Figure 11, the actual simulation result for these parameters yielded a bandwidth of 9 THz, representing a 9.4% improvement compared to the optimal result obtained by the traditional method. Moreover, the ML approach reduces the total computational time by several orders of magnitude while ensuring a more comprehensive exploration of the design space. Generating 2010 samples required approximately 4020 min of simulation time. Once the model is successfully trained, it can instantaneously predict the bandwidth for both 50% and 90% absorption for any new set of structural parameters and provide the optimal parameters.

Figure 11.

Simulated absorption spectra of the optimal structure by using the traditional method and ML techniques.

4. Conclusions

This study simulates and investigates a broadband metamaterial absorber integrated with vanadium dioxide operating in the THz regime. The simulation results demonstrate a wide absorption bandwidth of 8.23 THz (spanning from 5.08 to 13.31 THz), with the capability to modulate absorption from 3% to 98.74% by varying the conductivity of the VO2 layer. Specifically, at a conductivity of 200,000 S/m, two magnetic resonance peaks emerge at 6.1 and 11.91 THz, satisfying the impedance matching condition with the free space and enabling a broadband absorption within the operating frequency range. In addition to structural design, this paper confirmed the efficacy of applying ML to accelerate the design process. Among the three algorithms investigated, RF demonstrated superior performance by accurately capturing complex non-linear relationships that Linear Regression failed to address. The machine learning algorithm not only provided predictions closely aligned with the simulation results but also optimized the structural parameters more effectively than manual tuning methods, resulting in a 9.4% improvement in the absorption bandwidth.

Author Contributions

N.P.V. and B.X.K. conceived the idea. The electromagnetic simulation and calculation were carried out by B.S.T., H.D.T., L.Y., N.H.A. and N.P.H. N.P.V., L.C. and V.D.L. analyzed and wrote the article. Y.L. reviewed and supervised the article. All of the authors discussed and commented on the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Royal Society IES/R1/251098, VAST (NCXS02.01/26-27), and by the Shanghai Science and Technology Commission under grant #24110714600.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this paper is available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gao, W.; Chen, F.; Yang, W. Temperature and Refractive Index Sensor Based on Perfect Absorber in InSb Double Rectangular Ring Resonator Metamaterials. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 40, 109461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Lin, Y.-S. Tunable Perfect Meta-Absorber with High Sensitivity for Refractive Index Sensing Application. Sens. Bio-Sens. Res. 2024, 45, 100676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuyen, B.X.; Tan, P.D.; Tung, B.S.; Hai, N.P.; Tuan, P.D.; Phong, D.X.; Tung, D.K.; Anh, N.H.; Giang, H.T.; Vinh, N.P.; et al. Numerical Optimization of Metamaterial-Enhanced Infrared Emitters for Ultra-Low Power Consumption. Photonics 2025, 12, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Wang, Z.; Sun, T.; Song, Q.; Yi, Z.; Tang, C.; Zeng, Q.; Cheng, S.; Wu, P. Ultra-Broadband Absorber and near-Perfect Thermal Emitter Based on Multi-Layered Grating Structure Design. Energy 2025, 316, 134594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.A.; Mohsin, A.S.M.; Bhuian, M.B.H.; Rahman, M.M. Analysis of an Ultra-Broadband TiN-Based Metasurface Absorber for Solar Thermophotovoltaic Cell in the Visible to near Infrared Region. Sol. Energy 2024, 284, 113064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, K.; Islam, F.; Mahdy, M.R.C. A Tri-Layered Fibonacci Spiral-Inspired Metamaterial Absorber Exhibiting Enhanced Solar Energy Harvesting with an Emphasis on Thermophotovoltaic Cells. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2026, 29, 101448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landy, N.I.; Sajuyigbe, S.; Mock, J.J.; Smith, D.R.; Padilla, W.J. Perfect Metamaterial Absorber. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 207402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.P.; Rhee, J.Y.; Yoo, Y.J.; Kim, K.W. Metamaterials for Perfect Absorption; Springer Series in Materials Science; Springer: Singapore, 2016; Volume 236. [Google Scholar]

- Ngoc, N.V.; Hien, N.T.; Ha, D.T.; Tung, B.S.; Hai, B.X.S.; Lam, V.D.; Xuan Khuyen, B. A Rectangle-Quartet Metamaterial for Dual-Band Perfect Absorption in the Visible Region. Commun. Phys. 2022, 32, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khuyen, B.X.; Viet, N.N.; Son, P.T.; Nguyen, B.H.; Anh, N.H.; Chi, D.T.; Hai, N.P.; Tung, B.S.; Lam, V.D.; Zheng, H.; et al. Multi-Layered Metamaterial Absorber: Electromagnetic and Thermal Characterization. Photonics 2024, 11, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, R.M.H.; Saeed, M.A.; Choudhury, P.K.; Baqir, M.A.; Kamal, W.; Ali, M.M.; Rahim, A.A. Elliptical Metallic Rings-Shaped Fractal Metamaterial Absorber in the Visible Regime. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baqir, M.A. Wide-Band and Wide-Angle, Visible- and near-Infrared Metamaterial-Based Absorber Made of Nanoholed Tungsten Thin Film. Opt. Mater. Express 2019, 9, 2358–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viet, N.N.; Lam, V.D.; Tung, B.S.; Khuyen, B.X.; Son, P.T.; Anh, N.H.; Hai, N.P.; Tung, D.K.; Chi, D.T. Expanding the Absorption Bandwidth with Two-Layer Graphene Metamaterials in Gigahertz Frequency Range. Commun. Phys. 2024, 34, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouhan, B.S.; Ghosal, S.; Rohith, K.M.; Ray, S.; Giri, P.K.; Ahmad, A.; Kumar, G. Ultra-Broadband Actively Tunable Terahertz Modulator Based on Multi-Stacked Metamaterial. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerniauskas, G.; Sadia, H.; Alam, P. Machine Intelligence in Metamaterials Design: A Review. Oxf. Open Mater. Sci. 2024, 4, itae001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Holtz, M.; Fan, Z.; Bernussi, A.A. Effect of Substrate Orientation on Terahertz Optical Transmission through VO_2 Thin Films and Application to Functional Antireflection Coatings. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2012, 29, 2373–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, M.; Liang, Y.; Liang, R.; Zhao, L.; Xu, N.; Guo, J.; Wang, F.; Meng, H.; Liu, H.; Wei, Z. Dynamically Temperature-Voltage Controlled Multifunctional Device Based on VO2 and Graphene Hybrid Metamaterials: Perfect Absorber and Highly Efficient Polarization Converter. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Wang, Y.; Cui, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, K. Vanadium Dioxide-Based Terahertz Metamaterial Devices Switchable between Transmission and Absorption. Micromachines 2022, 13, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Hwang, H.Y.; Tao, H.; Strikwerda, A.C.; Fan, K.; Keiser, G.R.; Sternbach, A.J.; West, K.G.; Kittiwatanakul, S.; Lu, J.; et al. Terahertz-Field-Induced Insulator-to-Metal Transition in Vanadium Dioxide Metamaterial. Nature 2012, 487, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, H.; Cui, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wu, D. Tunable Multifunctional Terahertz Metamaterial Device Based on Metal-Dielectric-Vanadium Dioxide. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 181, 111629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Rukhlenko, I.D.; Premaratne, M. Graphene Metamaterial for Optical Reflection Modulation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 102, 241914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordal, M.A.; Long, L.L.; Bell, R.J.; Bell, S.E.; Bell, R.R.; Alexander, R.W.; Ward, C.A. Optical Properties of the Metals Al, Co, Cu, Au, Fe, Pb, Ni, Pd, Pt, Ag, Ti, and W in the Infrared and Far Infrared. Appl. Opt. 1983, 22, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, R.; Habib, S.; Hai, N.H.; Jyoti, O.; Islam, I.B.; Hasan, R.; Alam, M.S. Multifunctional THz Absorber Using a Hybrid VO2 -Graphene Metasurface: Modeling and Performance Analysis. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 174332–174348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.B.M.A.; Khaleque, A. Multi-Functional and Actively Tunable Terahertz Metamaterial Absorber Based on Graphene and Vanadium Dioxide Composite Structure. Opt. Contin. 2024, 3, 921–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhou, Z.; Zheng, X.; Wang, L.; Zhu, S.; Liu, H.; Zhou, Y. Broadband Tunable Chiral Selective Metamaterial Absorber Using Vanadium Dioxide. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2025, 64, 082003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Lin, H.; Tian, G.; Zhou, H.; Zhu, H.; Xiong, H.; Wang, B.-X. Triple-Band and Ultra-Broadband Switchable Terahertz Meta-Material Absorbers Based on the Hybrid Structures of Vanadium Dioxide and Metallic Patterned Resonators. Materials 2023, 16, 4719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Grzegorczyk, T.M.; Wu, B.-I.; Pacheco, J.; Kong, J.A. Robust Method to Retrieve the Constitutive Effective Parameters of Metamaterials. Phys. Rev. E 2004, 70, 016608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dayal, G.; Anantha Ramakrishna, S. Multipolar Localized Resonances for Multi-Band Metamaterial Perfect Absorbers. J. Opt. 2014, 16, 094016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Tang, Z.; Liu, X.; Huang, K. Power Loss Density of Electromagnetic Waves in Unimolecular Reactions. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 26546–26550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.