Abstract

Hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) is a promising material for vacuum ultraviolet (VUV) photodetection, owing to its ultra-wide bandgap and cost-effective synthesis. In this work, 2-inch high-quality hBN films were successfully deposited by magnetron sputtering, and 16×1 linear photodetector arrays were fabricated using a patterned electrode process. The fabricated devices exhibit excellent uniformity, achieving a dark current below 2 pA, a responsivity of 2.665 mA/W, a specific detectivity of 4.831 × 109 Jones, and rise/decay times of 91.31 and 147.25 ms, respectively. Furthermore, clear VUV images were obtained by using the photodetector array as the imaging unit of the imaging system. These results provide a convenient way to construct high-performance linear VUV photodetector arrays based on hBN films, and thus may push forward their future applications.

1. Introduction

Vacuum ultraviolet (VUV) photodetection is critically important in a variety of cutting-edge fields, including space science [1,2], radiation monitoring [3], electronic industry [4], and fundamental research [5,6]. The VUV detectors based on wide-bandgap semiconductors like silicon carbide (SiC) and gallium nitride (GaN) [7,8,9] are fundamentally limited by their narrower bandgaps, resulting in insufficient spectral selectivity within the VUV range. Ultra-wide bandgap semiconductor materials, such as diamond [10,11], magnesium oxide (MgO) [12,13], aluminum nitride (AlN) [14,15], and boron nitride (BN) [16,17,18,19], which exhibit more suitable optoelectronic properties for VUV detection, have attracted growing interest in recent years.

The hexagonal boron nitride (hBN, Eg ≈ 6 eV) exhibits great application potential in the fields of photodetection and flexible electronics due to its exceptional thermal conductivity, high breakdown electric field strength, and excellent physical and chemical stability [20,21]. Metal-semiconductor-metal (MSM) photodetectors based on hBN films combine straightforward fabrication and easy integration with superior performance, typically exhibiting extremely low dark current (on the order of pA or lower), strong responsivity to 185 nm illumination, and millisecond-scale response speed [17,22,23,24]. Zhang et al. demonstrated a VUV photodetector constructed from self-assembled hBN nanosheets that achieved a responsivity of 1.09 mA/W and a specific detectivity of 3.42 × 1011 Jones at 80 V bias, along with flexible photodetectors maintaining stable performance under bending conditions [17]. Chen et al. realized wafer-scale covalent heteroepitaxy of vertically aligned hBN on sapphire, achieving a responsivity of 11.60 mA/W at 185 nm, along with an ultrafast response of 270 ns/60 µs (rise/decay) and stable operation up to 500 °C [22]. By incorporating aluminum nanoprism arrays (Al-NPs), Liu et al. realized a plasmon-enhanced hBN-based detector with an external quantum efficiency (EQE) of 161% at 185 nm, and successfully fabricated an 8 × 8 detector array capable of VUV imaging [24].

However, advancing towards practical imaging systems with larger active areas and simpler readout architectures requires the development of scalable and integrable detector configurations. The linear array architecture, known for its simplified fabrication and straightforward signal readout, presents a promising pathway toward such systems. In this work, we fabricated a 16 × 1 linear photodetector array based on a 2-inch high-quality hBN film deposited via magnetron sputtering. The resulting device exhibits excellent response to 185 nm illumination and inherent VUV imaging capability, validating the linear array as an efficient and viable platform for next-generation VUV imaging systems.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Fabrication of hBN Films

The hBN films were prepared on c-plane sapphire substrates via radio-frequency magnetron sputtering at a growth temperature of 600 °C. A mixture of nitrogen and argon was used as the sputtering gas, with flow of 30 sccm and 10 sccm, respectively, and a chamber pressure maintained at 0.6 Pa. The BN target was sputtered using a power of 250 W for a duration of 100 min.

2.2. Device Fabrication

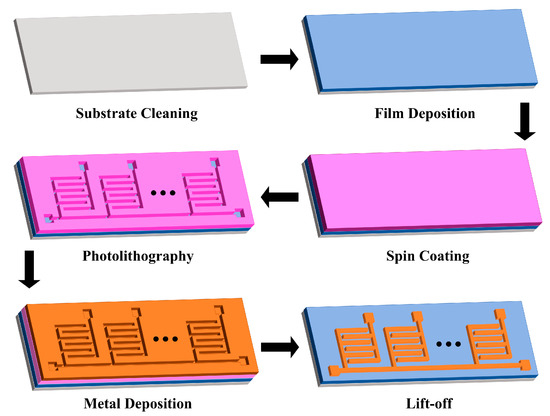

Linear photodetector arrays were fabricated on the hBN films using a standard photolithography process followed by electron-beam deposition, as shown in Figure 1. Nickel (Ni) was chosen as the electrode material, with an 80 nm-thick layer precisely deposited. Each unit within the arrays consists of interdigitated electrodes with a finger width and spacing of 30 μm.

Figure 1.

Fabrication process of the 16×1 Linear VUV photodetector array based on hBN film.

2.3. Characterization

The surface morphology of the hBN films were characterized using a field-emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM, FEI Quanta 250FEG, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) system and atomic force microscope (AFM, SPM-9700HT, Shimadzu, Japan). Raman spectra was conducted on a ViaQontor (Renishaw, UK) with a laser of 532 nm. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was conducted to confirm the composition of the hBN films (Thermo Fisher ESCALAB Xi+, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The optical absorption properties of hBN were verified by using the UV-visible near-infrared spectrophotometer (Lambda 950, PerkinElmer, USA).

Current-voltage (I-V) characteristics were measured at room temperature using a probe station equipped with a semiconductor parameter analyzer (Agilent 4155C, Agilent, USA). A low-pressure mercury lamp (185 nm) was employed as the light source, with its output power monitored by an optical power meter (3A-ROHS, Ophir Optronics, Israel).

3. Results and Discussion

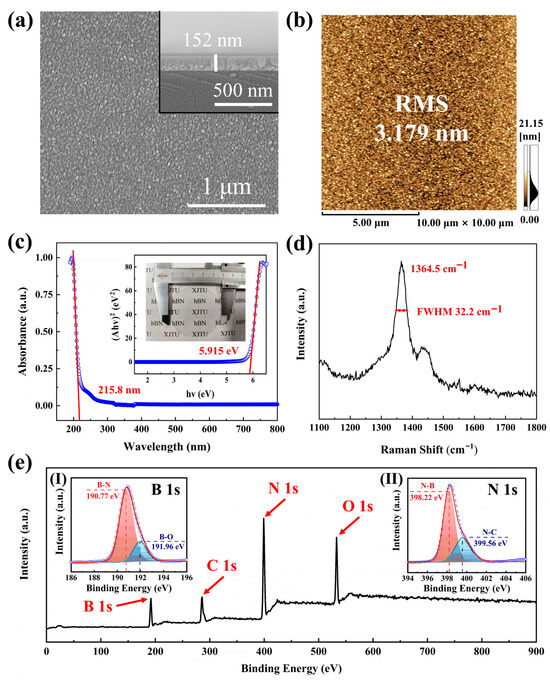

The microstructure and surface topography of the hBN film were systematically investigated. SEM image in Figure 2a reveals a continuous, dense, and crack-free surface with a thickness of 152 nm. AFM analysis (Figure 2b) further confirms the film uniformity, showing a smooth surface with a root-mean-square (RMS) roughness of 3.179 nm. The optical properties of the 2-inch hBN film on sapphire substrates were characterized by UV-vis absorption spectroscopy (Figure 2c). The absorption spectrum exhibits a characteristic peak at 202 nm and an absorption edge at 215.8 nm, from which the corresponding Tauc plot (inset) yields a direct optical bandgap of 5.915 eV.

Figure 2.

Characterizations of hBN films on sapphire: (a) SEM image. (b) AFM topography. (c) UV-vis absorption spectrum (inset: Tauc plot and photographic image. (d) Raman spectrum. (e) XPS survey spectrum (insets: high-resolution B 1s and N 1s spectra).

Figure 2d presents the Raman scattering spectrum of the hBN film, showing a characteristic peak at 1364.5 cm−1, which corresponds to the E2g in-plane vibration mode of hBNsingle crystal (1365 cm−1) [25]. The full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the peak is approximately 32.2 cm−1, serving as a key indicator of crystalline quality where a narrower linewidth signifies improved crystallinity and reduced structural defects. The XPS characterization was further conducted to analyze the chemical states of the film (Figure 2e). The insets (I) and (II) show the peak-fitting results of the B 1s and N 1s core-level spectra, respectively. Deconvolution of the B 1s spectrum reveals a dominant peak at 190.6 eV, corresponding to B-N bonds. A minor peak observed at 192.0 eV is assigned to B-O bonding, resulting from the reaction of interstitial boron atoms with adsorbed oxygen [26]. The N 1s spectrum indicates that the majority of nitrogen atoms are bonded to boron, with the main peak positioned at 398.22 eV. A weak feature at 399.59 eV suggests the presence of N-C bonds, possibly due to surface carbon adsorption.

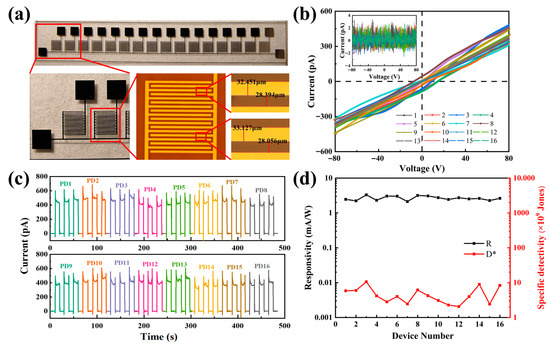

The 16×1 linear photodetector array, fabricated by patterning a Ni metal layer through photolithography and electron-beam evaporation, features interdigitated electrodes with a width and spacing of 30 μm (Figure 3a). The optoelectronic performance of each unit was evaluated by current–voltage measurements under dark condition and 185 nm ultraviolet illumination (30 μW/cm2), as shown in Figure 3b.

Figure 3.

Performance and uniformity of the hBN-based linear photodetector array: (a) Photograph and optical micrograph of the fabricated device. (b) I-V characteristics under 185 nm illumination (inset: dark condition), (c) Current-time (I-t) curves measured at 80 V. (d) Responsivity(R) and Specific Detectivity(D*) at 80 V bias.

The dark current of the linear photodetector array exhibits significant fluctuation over the ±80 V bias range, as its exceptionally low values (predominantly below 2 pA, corresponding to a current density of ~0.41 nA/cm2) approaches the measurement limit of the semiconductor parameter analyzer and thus becoming susceptible to environmental noise. This ultralow dark current originates from the ultra-wide bandgap of hBN, which effectively suppresses thermal carrier generation, thereby enabling high-sensitivity detection. Under 185 nm illumination, the device demonstrated a strong photoresponse, with the photocurrent reaching 309~481 pA at 80 V bias—a dramatic enhancement over the dark current level.

The transient response of the hBN linear photodetector array was evaluated under periodic 185 nm illumination at 80 V bias. As shown in Figure 3c, all units exhibited highly stable and reproducible switching behavior. The representative unit (PD1) exhibited a sharp on/off switching behavior, with the photocurrent rapidly rising to stable 450 pA under illumination and recovers promptly to the dark current level when the light was turned off. The corresponding responsivity and specific detectivity of 16 units are summarized in Figure 3d. The array showed uniform responsivity of 2.124~3.309 mA/W, while the specific detectivity varied from 2.062 × 109 to 1.062 × 1010 Jones due to the considerable variation in dark current.

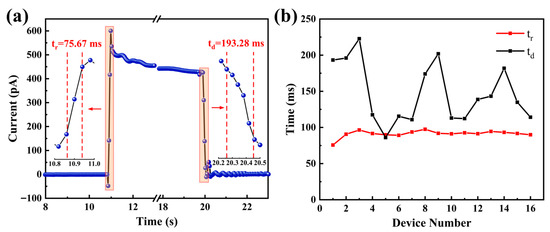

The response time of photodetectors is typically characterized by rise time (τᵣ) and decay time (τd), representing the photocurrent increase from 10% to 90% of maximum and subsequent decrease from 90% to 10%, respectively. Figure 4a displays the response curve of PD1 in a single cycle. The rising and falling edges of the curve are enlarged, demonstrating a fast response with τᵣ and τd of 75.67 and 193.28 ms, respectively. Statistical analysis across the array (Figure 4b) reveals significantly larger variation in decay time (85.99–222.75 ms) compared to rise time (75.67–96.52 ms).

Figure 4.

Response speed of the linear photodetector array: (a) Photo-response of PD1 to determine the response time. (b) Rise and decay time of 16 units.

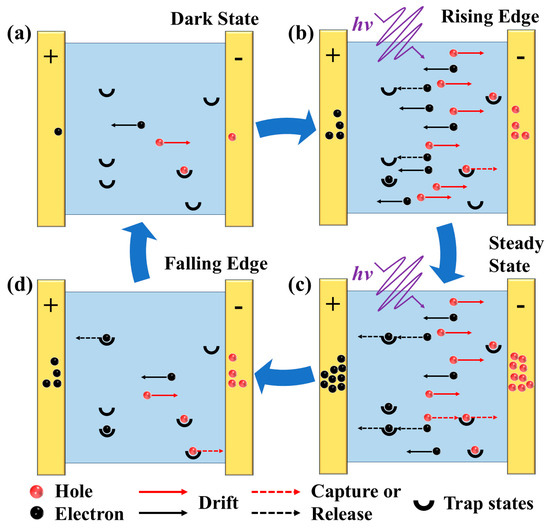

This divergence in response times stems from fundamentally distinct physical mechanisms, as detailed in Figure 5. The operational cycle of the hBN-based MSM photodetector encompasses four key stages of carrier dynamics: (a) Under dark equilibrium, the device exhibits minimal dark current, sustained only by sparse thermally generated carriers, while trap states remain largely unoccupied. (b) Upon illumination onset, a surge of photogenerated electron–hole pairs undergoes rapid field-driven drift. The concurrent trapping of carriers has negligible influence on the photocurrent rise, owing to the predominance of free carriers. (c) In the steady state, trap saturation is achieved, and a dynamic equilibrium is established between carrier generation and collection, yielding a stable photocurrent. (d) During the recovery phase, a biphasic decay emerges: an initial rapid sweep-out of free carriers, followed by a slow tail arising from thermal emission of carriers—especially holes—from deep-level trap states.

Figure 5.

Photo response mechanism of the hBN-based photodetector: (a) Dark equilibrium governed by thermally generated carriers, (b) Illumination-induced rise dominated by carrier drift transport, (c) Steady state with saturated traps under continuous illumination, (d) Recovery phase controlled by trap-mediated carrier release.

The rise time demonstrates high uniformity across the array, as it is governed by carrier transit time and the RC constant—parameters primarily determined by the interdigital electrode spacing and bias conditions. In contrast, the decay time is dominated by trap-assisted slow emission, where spatial variation in deep-level trap density and energy landscape within the hBN film directly accounts for the pronounced dispersion in τd across different units [11,27].

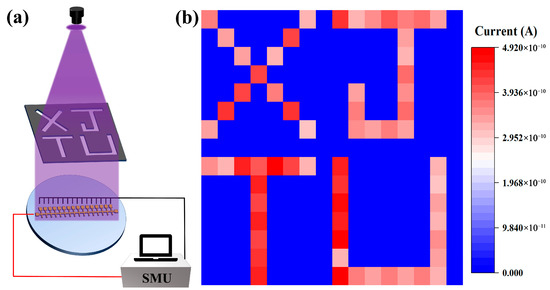

To demonstrate the imaging capability of the hBN-based linear photodetector array, a scanning imaging system was constructed, as schematically illustrated in Figure 6a. A hard mask with the hollow letters “XJTU” served as the target object and was translated along the axis perpendicular to the detector array. During the scanning process, the current signals from 16 units were sequentially recorded along with their corresponding spatial coordinates. The final image was reconstructed by mapping the current signals to the positional data, as shown in Figure 6b. The resulting image clearly resolves the “XJTU” pattern with sharp edges and low background noise, demonstrating high imaging fidelity. This successful reconstruction confirms the excellent spatial uniformity and response consistency of the hBN linear photodetector array, satisfying the essential requirements for application in VUV imaging systems.

Figure 6.

Imaging based on 16×1 linear photodetector array: (a) Schematic illustration of the imaging system. (b) Imaging of the “XJTU” letters patterned by a hard mask.

4. Conclusions

In this work, we have demonstrated the successful realization of a high-performance VUV linear photodetector array based on wafer-scale hBN films. Through magnetron sputtering deposition, we achieved uniform, high-quality hBN films on 2-inch sapphire substrates, with comprehensive structural and optical characterization confirming their hexagonal phase and excellent material properties. The fabricated 16×1 linear photodetector array with MSM structure exhibited remarkable unit-to-unit uniformity and outstanding detection capabilities. At 80 V bias, the devices achieved a dark current below 2 pA, a responsivity of 2.665 mA/W, a specific detectivity of 4.831 × 109 Jones, with rise and decay time of 91.31 and 147.25 ms, respectively. Furthermore, the implementation of a scanning imaging system utilizing the photodetector array successfully resolved clear “XJTU” patterns, validating its practical capability for VUV imaging applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.L.; methodology, Y.C. and H.L.; validation, J.L. and Z.L.; investigation, Q.L.; resources, W.F., H.L., X.Z. and A.L.; data curation, W.F. and Y.C.; writing—original draft preparation, W.F.; writing—review and editing, Q.L.; visualization, X.Z. and A.L.; supervision, F.Y. and T.W.; project administration, J.L. and Z.L.; funding acquisition, Q.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Nos. xzy022024061, xzd012023045, xzy012022088).

Data Availability Statement

Data underlying the results presented in this paper can be obtained from the authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the Instrumental Analysis Center of Xi’an Jiaotong University for helping in material analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cruden, B.A. Spectrally and Spatially Resolved Radiance Measurement in High-Speed Shock Waves for Planetary Entry. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2011, 39, 2718–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shugarov, A.; Sachkov, M. Spektr–UF Mission Spectrograph Space Qualified CCD Detector Subsystem. Photonics 2023, 10, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Zheng, W.; Huang, F. Vacuum-ultraviolet photodetectors. Photonix 2020, 1, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chini, M.; Wang, X.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, H.; Wu, Y.; Cunningham, E.; Li, P.-C.; Heslar, J.; Telnov, D.A.; Chu, S.-I.; et al. Coherent phase-matched VUV generation by field-controlled bound states. Nat. Photonics 2014, 8, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, B.; Averbukh, V. Single-Photon Laser-Enabled Auger Spectroscopy for Measuring Attosecond Electron-Hole Dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 111, 083004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Ooi, T.; Higgins, J.S.; Doyle, J.F.; von der Wense, L.; Beeks, K.; Leitner, A.; Kazakov, G.A.; Li, P.; Thirolf, P.G.; et al. Frequency ratio of the 229mTh nuclear isomeric transition and the 87Sr atomic clock. Nature 2024, 633, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, S.K.; Nag, R.; Mandal, K.C. Self-Biased Mo/n-4H-SiC Schottky Barriers as High-Performance Ultraviolet Photodetectors. IEEE Electr. Device Lett. 2023, 44, 733–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xi, X.; Li, X.; Lin, S.; Ma, Z.; Xiu, H.; Zhao, L. Ultra-High and Fast Ultraviolet Response Photodetectors Based on Lateral Porous GaN/Ag Nanowires Composite Nanostructure. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2020, 8, 1902162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetto, L.D.; Licciardo, G.D.; Erlbacher, T.; Bauer, A.J.; Rubino, A. A 4H-SiC UV Phototransistor With Excellent Optical Gain Based on Controlled Potential Barrier. IEEE Trans. Electron. Dev. 2020, 67, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balducci, A.; Marinelli, M.; Milani, E.; Morgada, M.E.; Tucciarone, A.; Verona-Rinati, G.; Angelone, M.; Pillon, M. Extreme ultraviolet single-crystal diamond detectors by chemical vapor deposition. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2005, 86, 193509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, N.; Lin, Z.; Cai, W.; Cheng, L.; Lu, X.; Zheng, W. Ultrafast Diamond Photodiodes for Vacuum Ultraviolet Imaging in Space-Based Applications. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2025, 13, 2402601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Lin, R.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Ji, X.; Huang, F. Vacuum Ultraviolet Photodetection in Two-Dimensional Oxides. Acs Appl. Mater. Inter. 2018, 10, 20696–20702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, L.; Liu, K.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, J.; Cheng, Z.; Chen, X.; Li, B.; Liu, L.; Shen, D. MBE-Grown MgO Thin Film Vacuum Ultraviolet Photodetector With Record High Responsivity of 3.2 A/W Operating at 400 °C. IEEE Electr. Device Lett. 2024, 45, 913–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BenMoussa, A.; Hochedez, J.F.; Dahal, R.; Li, J.; Lin, J.Y.; Jiang, H.X.; Soltani, A.; De Jaeger, J.-C.; Kroth, U.; Richter, M. Characterization of AlN metal-semiconductor-metal diodes in the spectral range of 44–360 nm: Photoemission assessments. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008, 92, 022108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, N.; Zhu, S.; Zheng, W. 193 nm immersion photodetector with an ultra-high EQE of 83.7%. Nano Today 2024, 56, 102281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Lin, R.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, F. Vacuum-Ultraviolet Photodetection in Few-Layered h-BN. Acs Appl. Mater. Inter. 2018, 10, 27116–27123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, Q.; Chen, R.; Zhang, M.; Fang, W.; Li, J.; Wang, M.; Yun, F.; Wang, T.; Hao, Y. Large-Area Self-Assembled Hexagonal Boron Nitride Nanosheet Films for Ultralow Dark Current Vacuum-Ultraviolet Photodetectors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2315149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, N.; Wei, X.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, W. Cubic boron nitride Schottky diode for vacuum ultraviolet photodetection. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2025, 234, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wu, T.; Zhao, J.; Zhu, J.; Chen, X.; Yu, H.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Z. High-Sensitivity Amorphous Boron Nitride Vacuum Ultraviolet Photodetectors. IEEE Electr. Device Lett. 2025, 46, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Feng, Y.; Wang, F.; Yang, Z.; Wang, J. Two dimensional hexagonal boron nitride (2D-hBN): Synthesis, properties and applications. J. Mater. Chem. C 2017, 5, 11992–12022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, J.D.; Aharonovich, I.; Cassabois, G.; Edgar, J.H.; Gil, B.; Basov, D.N. Photonics with hexagonal boron nitride. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2019, 4, 552–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ma, H.; Liu, C.; Wang, D.; Han, Z.; Tai, J.; Liang, H.; Yin, H. Covalent Heteroepitaxy of Large-Area Vertical Hexagonal Boron Nitride for High-Temperature VUV Photodetectors. Laser Photonics Rev. 2024, 18, 2400304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Xu, R.; Xu, S.; Liu, B.; Zhuang, Z.; Tao, T.; Pan, J.; et al. Easy-peeling growth of triangular hBN flakes and their demonstration in vacuum ultraviolet photodetectors. J. Mater. Chem. C 2025, 13, 17270–17277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ji, X.; Wu, T.; Yu, H.; Zhao, J.; Chen, X.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Z. Plasmon-Enhanced Hexagonal Boron Nitride Vacuum Ultraviolet Photodetector With Aluminium Nanoprism Array. IEEE Electr. Device Lett. 2025, 46, 1155–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, Y.; Watanabe, K.; Tsuda, O.; Taniguchi, T. Deep Ultraviolet Light-Emitting Hexagonal Boron Nitride Synthesized at Atmospheric Pressure. Science 2007, 317, 932–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Fang, W.; Wang, L.; Yun, F.; Wang, T.; Hao, Y. High-Crystallinity and High-Temperature Stability of the Hexagonal Boron Nitride Film Grown on Sapphire. Cryst. Growth Des. 2023, 23, 8783–8792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Mastro, M.A.; Tadjer, M.J.; Kim, J. Solar-Blind Metal-Semiconductor-Metal Photodetectors Based on an Exfoliated β-Ga2O3 Micro-Flake. ECS J. Solid. State Sc. 2017, 6, Q79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).