Abstract

The ecological status of lakes based on ichthyofauna, as defined by the Water Framework Directive, is assessed using intercalibrated methods. However, the methods adopted (in Poland, the Lake Fish Index LFI-EN method, based on results of one-off fishing with multi-mesh gillnets) are labor-intensive and do not allow for frequent repeat testing. Therefore, the concept of a simple model describing changes in the relative number of single traces in the vertical profile (according to the TS target strength distribution) in a lake is presented, as well as an index (the sum of deviations from such a model), enabling quantification of the similarity of TS distributions in lakes with this model. Preliminary analyses were conducted on acoustic data collected in Lake Dejguny. This lake—the condition of which could be estimated based on historical data using the relationships between LFI and the degree of lake eutrophication (expressed by Carlson’s TSI)—was assessed as having a good status in 2006, whereas in 2021, (based on LFI-EN) it had a moderate status. The study tested the TS distribution model, calculated as the arithmetic mean of the relative number of single traces in 2 m-thick layers. It was also shown that the proposed indicator can effectively signal deterioration of ecological status—the sum of the absolute values of the TS distribution deviations in 2021 (moderate status) from the model was more than seven times greater than the sum of the deviations of the distributions from which the model was built (good status). The obtained results confirmed the hypothesis about the possibility of determining a characteristic distribution of single traces in the vertical profile when the lake was classified as being in good condition.

1. Introduction

The EU Water Framework Directive [1] imposed on member states, among other requirements, the obligation to monitor all types of surface waters. This led to the development of a number of methods for monitoring the quality of aquatic ecosystems based on biological assessment elements, including the ecological status of lakes based on fish. The first such method for assessing the ecological status of waters—the Index of Biotic Integrity (IBI)—was developed in the 1980s. Based on several biotic indices that reflected various aspects of ichthyofauna communities, this index enabled the assessment of changes within these communities in shallow streams in the Midwestern United States [2]. Various versions of this index were developed, adapting it to the different characteristics of ichthyofauna in different regions and the objective of the Water Framework Directive, namely the assessment of the ecological status of lakes, rivers, and coastal waters [3]. Ultimately, in most European Union countries, various indicators have been developed, some of which are modifications of the IBI.

Two assessment methods have been developed in Poland. The older index, the Lake Fish Index (LFI+), is based on the response of the ichthyofauna structure to positive and negative environmental changes [4]. In this method, ecological status is determined based on the weight shares of species and their assortments in the total fish catch over ten years of commercial fishing. Because the fishing economy has changed in recent decades, and consequently, the number of lakes for which reliable catch data is available has significantly decreased, the LFI-EN method was developed, which is based on the results of monitoring catches conducted using Nordic net sets compliant with the EN 14757 standard [4]. The disadvantage of this method is the relatively high labor and time consumption, especially when applied to large and deep lakes (>1000 ha). According to the EN 14757 standard, up to 68 bottom-set Nordic gillnets should be deployed in such lakes, and pelagic gillnets should also be deployed in lakes deeper than 8 m. Their number depends on the lake depth, as they are to be set in a stepped pattern from the surface to the bottom [4]. Caught fish must be identified to species, separated into size groups, and weighed within these groups to the nearest 1 g. Calculations of the Lake Fish Index (LFI-EN) are based on the weight share (%) of fish species in the total catch. Calculations are performed separately for two types of lakes, stratified and non-stratified, and the obtained results are related to the reference lake model by calculating deviations from reference levels. In stratified lakes, the weight shares of bream, white bream, roach, bleak, and ruff are analyzed (they show an increase with increasing pressure indices, water transparency, phosphorus concentration, chlorophyll a concentration, and the complex Trophic State Index according to [5], as well as the weight shares of tench, rudd, and perch (they show a decrease). In unratified lakes, the group of fish whose weight share increases with increasing pressure indices also includes the share of pike-perch, while the second group (species showing a decrease) consists only of the weight shares of rudd and perch. The classification of lake ecological status is based on multiple regression equations, which are used to calculate the LFI-EN index values in individual lake equations. In cases where the species composition and structure of ichthyofauna in the assessed lake are shaped by human activities, the mathematical result is not reliable, and the final assessment is formulated by an expert [4].

The development of electronic technology gave hydroacoustics many advantages, including the ability to obtain data with varying spatiotemporal resolution compared to traditional sampling methods. However, researchers using hydroacoustics have noted that the results of acoustic surveys can be influenced by the orientation of fish relative to the transducer, the density and distribution of fish, and many other factors, including the degree of acoustic coverage of the body of water—defined as the ratio of the length of all transects to the square root of the lake surface [6]. It has been shown that when it is greater than (5-)7, the distribution and abundance of fish in the water column do not change significantly [7]. Many equations have been developed to describe the mathematical relationship between the target strength (TS) and total length (longitudo totalis—LT) or individual weight of fish, taking into account the aforementioned fish orientation [8,9]. Fish biomass in the lake was also determined using the acoustically estimated number of fish and the average weight of an individual in kg obtained from trawl fishing [10]. Numerous studies combining results obtained using acoustic tools and traditional sampling methods have shown that acoustic methods can be used to monitor fish populations [11,12,13,14]. However, it was emphasized that to ensure comparability of results, it is necessary to develop universally accepted standards for data collection and analysis in various systems [15]. All these aspects led to an attempt to develop a method (procedure) for acoustic monitoring and estimating changes in the ecological quality of lakes based on ichthyofauna and, ultimately, after the necessary calibration, to develop a method for classifying the ecological status/potential of lakes.

Previous analyses based on acoustic data have demonstrated that the vertical distribution of target strength (TS) in 2 m water layers can illustrate significant changes in the structure of ichthyofauna over time, and analysis of fish distribution in selected 2 m water layers in autumn in the same lake after thirteen years showed a significant reduction in the space available to fish below 24 m depth, which was associated with a reduction in dissolved oxygen concentration below this depth to a value lower than 2.5 mg L−1 [16]. Subsequent studies allowed for determining the uncertainty associated with measurements, including the natural movement of fish in lakes, which enables quantification of elements of fish structure assessment, i.e., the vertical distribution of target strength (TS) and the depiction of fish spatial distribution in 2 m water layers on maps. It was shown that even in shallow water (and in those studies in the 2–4 m and 4–6 m layers), the empirical probability of obtaining a statistically different (when Kendall’s τ coefficient < 0.7) vertical distribution of the TS target strength was 2/9 (i.e., 22%), although it is commonly assumed that such environments (shallow water) require the use of horizontally oriented transducers to maximize the acoustically searched water volume [17]. However, the fish occurrence areas in two out of nine replicates (with transects oriented east–west and zigzag on the third day of the study) in the 4–6 m layer differed statistically significantly from the mean area for all replicates by more than 14%, although this error was as high as 56–66% [18]. It was suggested that it would be possible to develop a simple index to assess changes in fish population structure, based, similarly to the Large Fish Index, on the ratio of large to small fish. The results confirmed that the proposed acoustic data analysis methods could be used to decide whether or not to conduct an assessment using the Polish national LFI-EN method based on the results of single-day fishing with Nordic multi-mesh gillnets.

This study conducted an extended analysis of acoustic data collected in Lake Dejguny in 2005, 2008, and 2021. Lake Dejguny, classified as a vendace lake in the fisheries classification system, was recognized by Associate Professor Witold Białokoz as one of the most valuable lake ecosystems in Poland, which had undergone only minor negative changes by the beginning of the 21st century, giving rise to hope for the maintenance or eventual restoration of its natural ecological systems [19]. The aims of the analyses were to (1) determine the probable ecological state of the lake in the second half of the first decade of the 21st century and (2) determine whether it is possible to determine a model describing a certain ecological state.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Lake Description

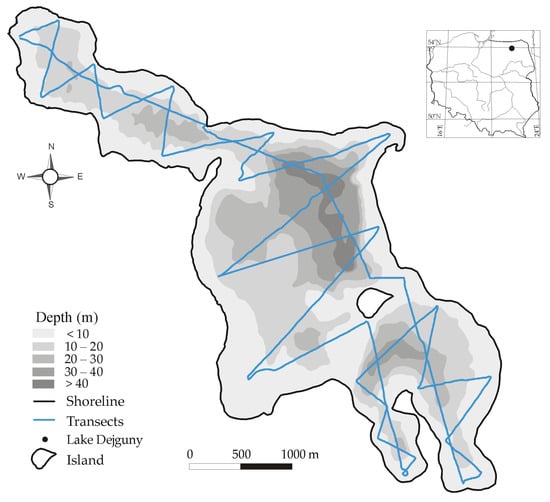

Lake Dejguny has a total area of 765.3 ha, a volume of 92.6 × 106 m3, a mean depth of 12.0 m, a maximum depth of 45.0 m, a maximum length of 6.5 km, and a maximum width of 2.4 km (Figure 1). It is located in the Masurian Lake District (northeastern Poland). The shape of the lake basin allows for the distinction of three parts: the northwestern part (with a maximum depth of 29 m), which is separated by a not-so-narrow isthmus, the central part (with a maximum depth of 45 m), and the southeastern part of the lake (with a maximum depth of >30 m). This reservoir was identified by Witold Białokoz in 2010 as one of the most valuable natural lake ecosystems, having undergone “the least negative changes to date,” retaining “its mesotrophic character,” and the lake “holds promise for the maintenance or eventual restoration of its natural habitats”. This lake was “fishing-oriented, focused on managing a strong vendace population based on stocking and harvesting.”

Figure 1.

Bathymetric map of Lake Dejguny with marked boat routes during hydroacoustic surveys in November 2005, October 2008, and 2021 (according to Hutorowicz et al., [16]).

Lake Dejguny was covered by monitoring studies only in 1989, as part of State Environmental Monitoring. At that time, physicochemical indicators were taken into account (average oxygen saturation of hypolimnion water, oxygen concentration in the bottom layer in summer, COD, BOD5, phosphorus and nitrogen concentrations, electrolytic conductivity, total seston as total dry mass, and Secchi disk visibility) and “field observations” (“the occurrence of fish kills or mass mortality of other aquatic organisms excluded the lake from classification”). On this basis, the lake water was classified as class II (on a three-point scale) [20]. According to the assessment “Assessment of the condition of lakes in the years 2010–2015”, Lake Dejguny was assessed as high ecological status (however, it was an “assessment extrapolated on the basis of pressure”) [21]. However, based on studies conducted in 2021 as part of State Environmental Monitoring, the LFI-EN index value was determined to be 0.53, and the lake was assessed as being of moderate status [22]. The above data suggest that the ecological condition of the lake has deteriorated since 2010. This may justify comparing acoustic data to confirm their suitability for imaging changes in ecological condition.

2.2. Acoustic Data

This study used hydroacoustic data collected on 15 November 2005, 13 October 2008, and 7 October 2021. Hydroacoustic research was carried out at night, starting one hour after sunset. This is due to the dispersion of fish, which allows for the registration of individuals [23]. In 2005, a 7° × 7° transducer was used, and in 2008 and 2021, a 4° × 10° elliptical transducer [24]. The transducer was mounted on a kite designed by Bronisław Długoszewski. This kite was attached to a rope and floated freely on the surface of the water from the side of the boat, just behind its bow.

The pulse duration was set to 0.3 ms, and the pulse interval was set to the fastest possible in the system control software. Hydroacoustic measurements were conducted at a speed of 2.0–2.5 km h−1 along zigzag transects covering the entire lake area (Figure 1). Data from 2008 and 2021 were previously used in previous studies [16].

These data met the assumptions adopted in the previous study [16]: they must be collected using an identical method (the same probe, the same lake search routes, a comparable period (month) of fieldwork, and an identical data processing procedure). The only exception to these requirements was the inclusion of research from October 2005, i.e., 32 and 39 days later than during the research conducted in 2008 and 2021, respectively.

Hydroacoustic data were processed using the Simrad EP500 ver. 5.3 echo processing system, which is dedicated to this echosounder [25]. In each echogram, the number of single traces (NST) was determined separately for water layers 2 m-thick, starting from the layer at a depth of 2–4 m. Since NST in this study is related to the length of tracks, an important condition for the reproducibility of the results is that the coefficient of variation in the estimated number of single traces is less than 10%. According to Aglen [6], this condition is fulfilled when the ratio of the cumulative length of hydroacoustic transects (km) to the square root of the lake surface (km2), i.e., the degree of coverage, was at least 3.0, and preferably around or above 6.0 [16]. The total length of the routes on which the Lake Dejguny was acoustically searched, about 8.4 km, and the degree of coverage was 6.5.

Since the potential future method is to be related to the official LFI-EN method, it was assumed that it would have to take into account the low effectiveness of gillnets in catching small fish, i.e., those with a total length less than 40–50 mm [26]. Therefore, it was already assumed in previous publications that such fish would be excluded from the analyses. The calculated target force (TS) is −50 dB, according to the regression function defined by Frouzová et al. [9] for fish with an overall length of 35 mm, while according to the relationship determined by Świerzowski and Doroszczyk [27] specifically for whitefish in Lake Pluszne with a total length of 58.9 mm. Therefore, as in the previous study, signals in the range from −50 dB to −17 dB with a TS class resolution of 3 dB [16]. Class resolution is based on the capabilities of the Simrad EP500 software [25].

2.3. Environmental Data

The study used measurements of temperature and concentration of dissolved oxygen, as well as the Trophic State Index (TSI). The sources of these data and sampling dates are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of data used in the study on the physicochemical and biological properties of water in Lake Dejguny.

2.4. Data Analysis

Following the pattern adopted in previous studies, the number of single traces (NST) was presented in vertical distributions (in 2 m-thick layers), taking into account the assumed target strength classes with a resolution of 3 dB [16,18].

The method of describing the vertical distributions of TS was adopted based on the descriptions of elution profiles in HPLC chromatography [30]. Among the important features of these profiles are the time of the peak and its height. A preliminary inspection of the TS profiles suggested that the characteristic properties of TS profiles are the depth (location) of the appearance of a larger number of single traces and their height, i.e., the number of single traces. It was considered that just as in mountain ranges, there may be mountain peaks of different heights next to each other, so in TS profiles, we can also talk about several peaks. This was also evidenced by the division into TS classes, which clearly showed that these peaks were formed by other fish, if not a different species, then at least to a large extent by fish of different LT.

In this study, the basis for further analyses was the number of single traces (NST), calculated according to the following formula:

where is the number of single traces identified in layer e in the l-th vertical profile of the TS distribution; l is the ordinal number of the analyzed target strength distribution TS (TS profile registered in the next test date); e is the number (from 1 to emax) of the subsequent analyzed water layers (e.g., 2–4 m; 4–6 m, etc.).

Based on the NST, the relative number of single traces was calculated, i.e., the share of NST (SNST) in a given water layer in the total number of single traces identified on a given day of the study, according to the following formula:

In accordance with the assumption that in a lake with unchanged ecological conditions, the vertical distribution of target force does not differ significantly in autumn in subsequent years of study, a temporary model (M) was calculated, illustrating changes in the number of single traces with depth, according to the following formula:

where is the share of single traces in layer e in the vertical profile of the target strength distribution (TS); e is the number (from 1 to emax) of the subsequent analyzed water layers (e.g., 2–4 m; 4–6 m, etc.) (in this study emax = 2); is the share of the number of single traces in layer e in the l-th vertical profile of the TS distribution (TS profile recorded in the next research date).

According to the Water Framework Directive, a metric that allows for the classification of a given lake into a given ecological status class should express the difference between the biological indicator value in unaltered (reference) lakes and the indicator value calculated based on data collected in the lake being assessed. In this study, the best possible condition was assumed as the reference condition, specifically the condition described by the above-mentioned model (Equation (1)). Deviations of the relative number of single traces from this model were assumed to be a measure of dissimilarity. It was assumed that the metric would be expressed by the following formula:

where Δ is the sum of absolute values of deviations of the share of the number of fish in layer e in the total number of single traces of the compared (marked with the symbol x) distribution of target strength TS from the value of the share of the number of single traces in layer e in the model vertical profile of the distribution of target strength TS.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fish Size Structure

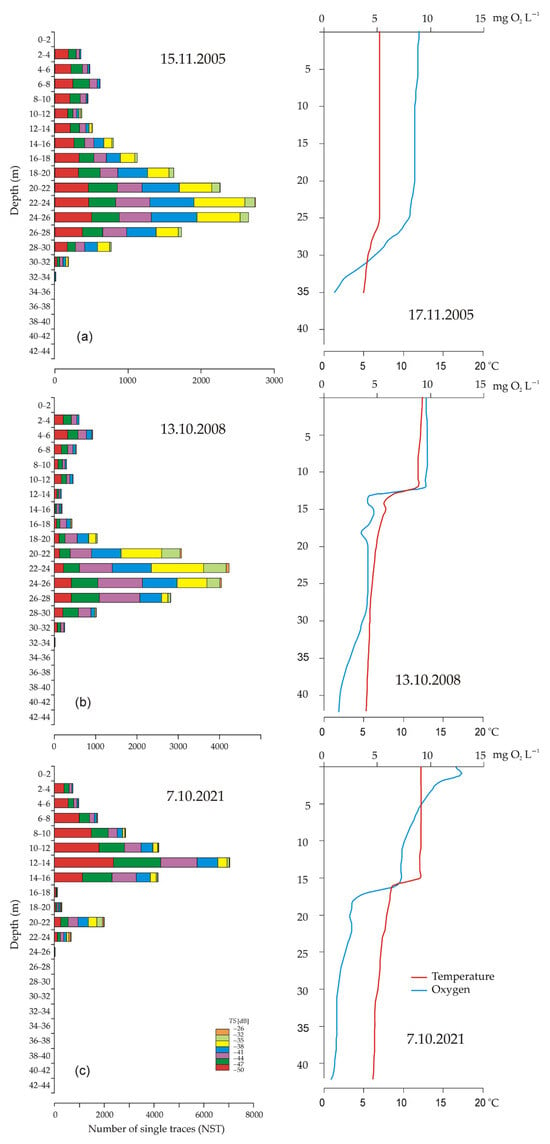

In November 2005, the NST was recorded as 16,713 in the water column. Two peaks were observed in the vertical profile—a significantly smaller one at a depth of 6–8 m and one with more than four times as many NST (>2700) between 22 and 24 m depth (Figure 2a). Near the surface, smaller fish with TS ≤ −41 dB dominated (NST of 1917, representing 99.5% of all single traces detected in this layer). Deeper, the share of larger fish with TS > −41 dB was significantly higher. Between 18 and 28 m of depth, it reached 27.5%, but below 30 m of depth, it decreased to 18%.

Figure 2.

Target strength (TS) distribution in 2 m-thick layers and oxygen and temperature profiles in Lake Dejguny on (a) November 2005, (b) October 2008, and (c) October 2021 (data after [16,28]).

In October 2008, the total NST was recorded as 20,100 (16.8% more than in autumn 2005). The vertical profile of the TS was very similar to that of November 2005. A smaller peak, located closer to the water surface, was observed this time at a depth of 4 to 6 m (Figure 2b). This was created by a total NST of 925, 46% more than in autumn 2005. The second peak, with a maximum NST of 4237 (54% more), was recorded at the same depth, between 22 and 24 m. Similarly to November 2005, up to a depth of 14 m, the share of small fish, with TS ≤ −41 dB, ranged between 82% and 91%, while below a depth of 14 m, with the exception of the water layer between 20 and 24 m, it ranged from 53% to 93%. At the aforementioned depth of 20–24 m, small fish accounted for 29–33%.

In October 2021, the largest number of single traces was recorded, 24,794, which is 23% more than in the fall of 2008 and 48% more than in November 2005. Fish were observed exclusively to a depth of 28 m, although only four signals were detected in this layer (24–26 m, unfortunately not visible in Figure 2 due to scale). The largest number of single traces (i.e., 7035 single traces, approximately 28% of all detected) was recorded in the layer from 12 to 14 m (Figure 2c). The second peak, more than three times smaller, occurred at a depth of 20–22 m. It consisted of an NST of 1993, which constituted only 8% of all NST detected. At depths from 2 m to 18 m, small fish with TS ≤ −41 dB dominated, constituting 79–94% of all traces detected in these layers.

In 2008 and 2021, the lowest number of single traces (albeit greater than 0) was observed near the thermocline. In 2008, only a total NST of 174 was recorded in the water layer at a depth of 12–14 m, or <0.9% of all detections, and in 2021, just below the thermocline, in the layer 16–18 m, only a total NST of 119 was found, or about 0.5% of all detections. In November 2005, the minimum was recorded at a depth of 10–12 m, but a total NST of 365 was recorded there, representing 2.8% of all detections.

The distributions of TS target strength in the water layers of Lake Dejguny from November 2005 and October 2008 did not differ significantly. The Kendall’s tau coefficient (τ) for the total single traces count series was τ = 0.662 at p = 0.002. According to Guilford’s interpretation of the significance of correlation (Aswegen and Engelbrecht [31]), this indicates the existence of a moderate correlation and, therefore, a statistically significant relationship between the number of single traces recorded at individual depths on these dates.

However, Kendall’s tau coefficient when comparing the TS target strength distribution from October 2021 with the remaining distributions took the value τ = 0.09 at p = 0.62 and τ = −0.06 at p = 0.741, respectively, which indicates almost no relationship. This signals a significant change that can be linked to a change in ecological status.

3.2. Ecological Condition of the Lake

As already mentioned in the lake description (Section 2.1), based on studies conducted in 2021 as part of State Environmental Monitoring, the index value LFI-EN was determined to be 0.53, and the lake was assessed, based on ichthyofauna, as moderate ecological status [22].

Using the relationship between the LFI and the TSI pressure index, described by the authors of the Lake Fish Index (LFI) [32], the ecological status of Lake Dejguny was estimated as good in the mid-2000s. This was possible thanks to processed data on the Secchi disk visibility and chlorophyll concentration measured in the summer of 2006 in Lake Dejguny, which indicated a mesoeutrophic state of this lake, as well as a TSI value of 53 [29]. According to Białokoz and Chybowski, the TSI values of 53.6 and 57.5 in two deep vendace lakes in the Wel River basin [after 32] indicated that their condition was assessed as good based on the above-mentioned TSI and LFI relationship (LFITSI index).

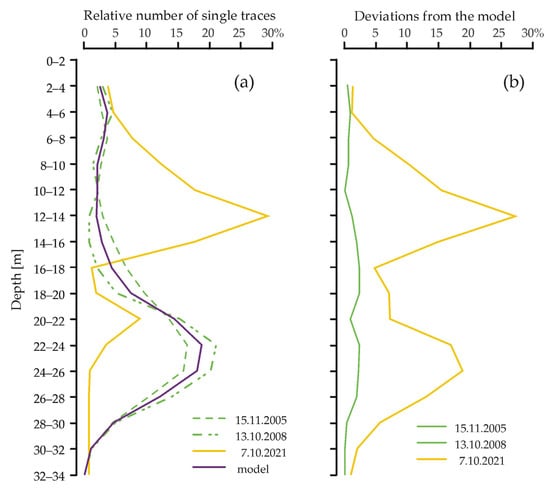

3.3. Model

A preliminary model was built to determine characteristic features (i.e., changes with depth) of the total number of identified NST in the vertical profile of Lake Dejguny in 2005 and 2008, when TS distributions showed significant similarity (Figure 2a,b). For this purpose, the NST in TS distributions was expressed as a percentage of all NST detected during acoustic surveys on a given day according to formula 2, and arithmetic means were calculated in each water layer according to Formula (3) (Figure 3a). Calculation of deviations (Δ) between the TS distribution from autumn 2021 and the preliminary model (Formula (4)) showed that the sum of the absolute value of deviations was as much as 138%, while for the distributions consistent with the model (in this case, forming this model), it was only 18% (Figure 3b). This indicates that in future studies, this preliminary model could be adopted as a starting point for the search for a more general model describing the distribution of TS in vendace-type lakes classified as at least good condition.

Figure 3.

Distribution of relative number of single traces (%) in 2 m-thick layers in Lake Dejguny on 15 November 2005, 13 October 2008, and 7 October 2021 (a) and the distribution of shape deviations (Δ) of these profiles from the model (b).

In Europe, 24 fish-based assessment systems have been developed under the Water Framework Directive [33], each generating between 2 and 13 indicators. These indicators include abundance and biomass, relative abundance of Perca fluviatilis, Rutilus rutilus, and Abramis brama, dietary preferences, sensitive species, and non-native species. Most often, these systems are based on results from multi-mesh gillnet fishing or a combination of non-standard gillnet fishing, fyke net fishing, and electrofishing [33]. According to a summary published by Poikane in 2017, hydroacoustics, along with multimesh gillnet fishing and electrofishing, is used exclusively in the Czech Republic [34].

Of course, a simple model—a curve illustrating changes in fish numbers with depth—can be only one of the partial metrics of a more comprehensive assessment system, which will take into account other features visible in the TS target strength distributions, such as fish abundance in size classes (total length). This aspect may, to some extent, compensate for the inability to identify species based on acoustic surveys. However, since monitoring covers over 1000 lakes in Poland, the ecological status/potential of most lakes is determined in six-year cycles. Only in 22 benchmark lakes are monitoring studies conducted on a three-year cycle [35]. Therefore, would it not be worthwhile to attempt to develop even a simplified system that would enable more frequent verification of changes in ecological status, and perhaps, after prior positive calibration, even conduct the assessment itself?

4. Conclusions

The conducted research did not rule out the possibility of building a model illustrating the characteristic autumn fish distribution pattern in the vertical profile of deep vendace-type lakes. The small differences between the vertical distributions of fish numbers in two different years (2005 and 2008 in Lake Dejguny) suggest that, by maintaining the same research procedure, it is possible to obtain relatively similar data enabling the creation of models quantifying the characteristic features of fish distribution in a lake in a specific ecological state.

The model presented in this study can be considered only preliminary. The reasons include the extremely small number of cases analyzed and the lack of data enabling the definition of reference conditions. Furthermore, the model only considers one aspect—the number of fish in the water layers—and, therefore, can be treated as one of the metrics that will form a future system for assessing changes in ecological status. Hence, there is a need for continued research.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Inland Fisheries Research Institute in Olsztyn as part of the statutory research activity (topic no. Z-017).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- European Environment Agency. Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy. Off. J. Eur. Communities 2000, L 327, 0001–0073. [Google Scholar]

- Szlachciak, J. Ocena stanu ekologicznego jezior z wykorzystaniem ichtiofauny. In Biologiczne Metody Oceny Stanu Środowiska. Tom 2. Ekosystemy Wodne; Ciecierska, H., Dynowska, M., Eds.; Uniwersytet Warmińsko-Mazurski w Olsztynie: Olsztyn, Poland, 2013; pp. 237–258. [Google Scholar]

- Belpaire, C.; Smolders, R.; Vanden Auweele, I.; Ercken, D.; Breine, J.; Van Thuyne, G.; Ollevier, F. An Index of Biotic Integrity characterizing fish populations and the ecological quality of Flandrian water bodies. Hydrobiologia 2000, 434, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, M.; Prus, P. Ryby w jeziorach. In Podręcznik do Monitoringu Elementów Biologicznych i Klasyfikacji Stanu Ekologicznego Wód Powierzchniowycy. Aktualizacja Metod; Kolada, A., Ed.; Biblioteka Monitoringu Środowiska: Warszawa, Poland, 2020; pp. 297–324. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, R.A. Trophic State Index for Lakes. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1977, 22, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algen, A. Random Errors of Acoustic Fish Abundance Estimates in Relation to the Survey Grid Density Applied. In FAO Fisheries Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1983; pp. 293–298. [Google Scholar]

- Doroszczyk, L.; Długoszewski, B.; Godlewska, M. Badania hydroakustyczne ichtiofauny jeziora Hańcza. In Środowisko i Ichtiofauna Jeziora Hańcza; Kozłowski, J., Poczyczyński, P., Zdanowski, B., Eds.; Wydawnictwo IRS: Olsztyn, Poland, 2008; pp. 191–201. [Google Scholar]

- Kubečka, J.; Duncan, A. Acoustic size vs. real size relationships for common species of riverine fish. Fish. Res. 1998, 35, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frouzová, J.; Kubečka, J.; Balk, H.; Frouz, J. Target strength of some European fish species and its dependence on fish body parameters. Fish. Res. 2005, 75, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godlewska, M.; Doroszczyk, L.; Długoszewski, B.; Kanogowska, E.; Pyka, J. Long-term decrease of the vendace population in Lake Pluszne (Poland)—Result of global warming, eutrophication or both? Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 2014, 14, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doroszczyk, L. Wykorzystanie Metod Hydroakustycznych do Oceny Populacji Sielawy na Przykładzie Jeziora Pluszne. Ph.D. Thesis, The St. Sakowicz Inland Fisheries Institute, Olsztyn, Poland, 2011; p. 81. [Google Scholar]

- Emmrich, M.; Winfield, I.J.; Guillard, J.; Rustadbakken, A.; Vergès, C.; Volta, P.; Jeppesen, E.; Lauridsen, T.L.; Brucet, S.; Holmgren, K.; et al. Strong correspondence between gillnet catch per unit effort and hydroacoustically derived fish biomass in stratified lakes. Freshw. Biol. 2012, 57, 2436–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillard, J.; Lebourges-Dhaussy, A.; Balk, H.; Colon, M.; Jóźwik, A.; Godlewska, M. Comparing hydroacoustic fish stock estimates in the pelagic zone of temperate deep lakes using three sound frequencies (70, 120, 200 kHz). Inland Waters 2014, 4, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tušer, M.; Guillard, J.; Rustadbakken, A.; Mehner, T. Comparison of fish size spectra obtained from hydroacoustics and gillnets across seven European natural lakes. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2022, 79, 2179–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samedy, V.; Wach, M.; Lobry, J.; Selleslagh, J.; Pierre, M.; Josse, E.; Boët, P. Hydroacoustics as a relevant tool to monitor fish dynamics in large estuaries. Fish. Res. 2015, 172, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutorowicz, A. Use of Hydroacoustic Methods to Assess Ecological Status Based on Fish: A Case Study of Lake Dejguny (Poland). Water 2024, 16, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godlewska, M.; Frouzová, J.; Kubečka, J.; Wiśniewolski, W.; Szlakowski, J. Comparison of hydroacoustic estimates with fish census in shallow Malta Reservoir—Which TS/L regression to use in horizontal beam applications? Fish. Res. 2012, 123–124, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutorowicz, A. Repeatability of Hydroacoustic Results versus Uncertainty in Assessing Changes in Ecological Status Based on Fish: A Case Study of Lake Widryńskie (Poland). Water 2024, 16, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białokoz, W. Funkcjonowanie Mezotroficznego Jeziora z Liczną Populacją Sielawy, na Przykładzie Jeziora Dejguny (Północno-Wschodnia Polska); Lake Fisheries Department of the Inland Fisheries Institute Named after St. Sakowicz: Giżycko, Poland, 2010; p. 9, Unpublished Materials. [Google Scholar]

- Wróblewska, H. Monitoring jezior. In Raport o Stanie Środowiska Województwa Warmińsko-Mazurskiego w 2008 Roku [Report on the State of the Environment of the Warmia-Masuria Voivodship in 2008]; Kochańska, E., Ed.; Biblioteka Monitoringu Środowiska: Olsztyn, Poland, 2009; pp. 38–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ocena Stanu Jezior w Latach 2010–2015 [Assessment of the Condition of Lakes in the Years 2010–2015]. Tabela 4.8.4_Zbiorcza Ocena wód_dane zestawione.xlsx. Available online: https://wody.gios.gov.pl/pjwp/publication/LAKES/87 (accessed on 9 December 2023).

- Klasyfikacja Wskaźników i Grup Wskaźników w Jednolitych Częściach Wód Powierzchniowych Jezior za Rok 2021 [Classification of Indicators and Groups of Indicators in Lake Surface Water Bodies for 2021]. Available online: https://wody.gios.gov.pl/pjwp/publication/LAKES/87 (accessed on 9 December 2023).

- Dembiński, W. Vertical distribution of vendance Coreginus albula L. and other pelagic fish species in some Polish lakes. J. Fish. Biol. 1971, 3, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorosczyk, L.; Dlugoszewski, B. Rozmieszczenie, Wielkość i Biomasa Ryb w jez. Dejguny w sierpniu 2005 r. [Distribution, Size and Biomass of Fish in Lake Dejguny in August 2005; Inland Fisheris Institute: Olsztyn, Poland, 2010; p. 22, Unpublished Materials. [Google Scholar]

- Simrad EP 500, Echo Processing System, 1997, Instruction Manual. [This is the manual that came with the EY 500 fishfinder. It was published in 1997 (version 5.3)]. SIMRAD A Kongsberg Company: Horten, Norway, 1997; 1–69.

- Prchalová, M.; Kubečka, J.; Říha, M.; Mrkvička, T.; Vašeka, M.; Jůza, T.; Kratochvíl, M.; Peterka, J.; Draštíka, V.; Křížekd, J. Size selectivity of standardized multimesh gillnets in sampling coarse European species. Fish. Res. 2009, 96, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świerzowski, A.; Doroszczyk, L. Seasonal differences in in situ measurements of the target strength of vendance (Coregonus albula L.) in Lake Pluszne. Hydroaousstics 2004, 7, 217–226. [Google Scholar]

- Dorosczyk, L.; Dlugoszewski, B. Rozmieszczenie, Wielkość i Biomasa ryb w jez. Dejguny w listopadzie 2005 r. [Distribution, Size and Biomass of Fish in Lake Dejguny in November 2005; Inland Fisheris Institute: Olsztyn, Poland, 2010; p. 8, Unpublished Materials. [Google Scholar]

- Pyka, J.P.; Zdanowski, B.; Stawecki, K.; Prusik, S. Trends in environmental changes in the selected lakes of the Mazury and Suwałki Lakelands. Limnol. Rev. 2007, 7, 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm, C.; Volkmar, P.; Lohmann, C.; Becker, A.; Meyer, M. The HPLC-aided pigment analysis of phytoplankton cells as a powerful tool in water quality control. J. Water SRT-Aqua 1995, 44, 132–141. [Google Scholar]

- Van Aswegen, A.S.; Engelbrecht, A.S. The relationship between transformational leadership, integrity and an ethical climate in organisations. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 7, 1–9. Available online: https://sajhrm.co.za/index.php/sajhrm/article/view/175 (accessed on 24 February 2024). [CrossRef]

- Białokoz, W.; Chybowski, Ł. Ichtiofauna. Guidelines for Integrated Assessment of Ecological Status of Rivers and Lakes to Support River Baisin Management Plans. In Ecological Status Assessment of the Watres in the Wel River Catchment; Soszka, H., Ed.; Wydawnictwo IRS: Olsztyn, Poland, 2011; pp. 217–234. [Google Scholar]

- Ritterbusch, D.; Blabolil, P.; Breine, J.; Erős, T.; Mehner, T.; Olin, M.; Peirson, G.; Volta, P.; Poikane, S. European fish-based assessment reveals high diversity of systems for determining ecological status of lakes. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 802, 149620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poikane, S.; Ritterbusch, D.; Argillier, C.; Białokoz, W.; Blabolil, P.; Breine, J.; Jaarsma, N.G.; Krause, T.; Kubečka, J.; Lauridsen, T.L.; et al. Response of fish communities to multiple pressures: Development of a total anthropogenic pressure intensity index. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 586, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monitoring Jezior [Lake Monitoring]. Available online: https://www.infish.com.pl/content/monitoring-jezior (accessed on 24 February 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.