Abstract

This article proposes a bat algorithm that incorporates novel techniques inspired by maritime radars, referred to as the Radar-Bat algorithm. This proposed method allows each virtual bat to identify the position of the best solution at a given distance within the search space. It incorporates an adaptive threshold to maintain a constant false alarm rate (CFAR), enabling the acceptance of solutions based on the best value found, thus improving the exploitation of the search space. Furthermore, a systematic directional sweep balances exploration and exploitation effectively. This algorithm is used to solve complex optimization problems, essentially those with multimodal functions, demonstrating that the proposed algorithm achieves better convergence and robustness compared to the basic bat algorithm, highlighting its potential as a novel contribution to the field of metaheuristics. To evaluate the performance of the proposed algorithm against the basic bat algorithm, the Wilcoxon and Friedman non-parametric tests are applied, with a significance level of 5%. Computational experiments show that the proposed algorithm outperforms the state-of-the-art algorithm. In terms of quality, the proposed algorithm shows clear superiority over the basic bat algorithm across most benchmark functions. Regarding efficiency, although Radar Bat incorporates additional mechanisms, the experimental results do not indicate a consistent disadvantage in execution time, with both algorithms exhibiting comparable performance depending on the problem and dimensionality.

1. Introduction

Currently, complex optimization problems commonly arise in areas such as structural engineering, data science, and logistics and are typically characterized by multimodal and highly dimensional search spaces. Under these conditions, integer linear programming (ILP) methods are inefficient and impractical. Metaheuristic algorithms, inspired by natural or social processes, have proven to be a practical and effective solution for finding approximate optimal solutions in reasonable times [1]. An effective method for solving this type of optimization problem is the bat algorithm (BA), proposed by Xin She [2]. This algorithm uses the echolocation technique of bats to explore the solution space using pulse frequency, amplitude, and emission rate as parameters [3]. Some prominent applications of BA include structural design and parameter optimization in engineering, task scheduling and process planning [4], and data classification and pattern mining [1]. The BA in its most basic form exhibits local stagnation difficulties due to a loss of diversification when the amplitude and emission rate adjustment mechanism no longer enhances effective exploration in the solution space [5]. On the other hand, in highly multimodal spaces it has slow convergence and limited accuracy, especially when it lacks additional controls during search execution [6]. In the context of the recent literature on the BA and its variants (see Section 3), extensions have been proposed to improve exploration and exploitation through directional mechanisms, adaptive strategies, and hybrid schemes. Among these, directional variants stand out for improving the spatial coverage of the global best’s neighborhood, as well as enhanced versions incorporating diversification and dynamic parameter adjustments, and discrete, binary, and multi-objective extensions that broaden the BA’s scope to include combinatorial and multi-criteria problems. Due to the disadvantages of BA, this research proposes the incorporation of the following novel techniques inspired by maritime radar:

- Maritime radar-type directional sweep that allows for systematic exploration in multiple directions.

- Adaptive mapping to direct the search to less explored areas.

- CFAR-type adaptive dynamic threshold for accepting solutions based on the best current value.

The remainder of the article is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the materials and methods, including the structure of the proposed Radar-Bat algorithm and its radar-inspired components. Section 3 reviews the related work and the context of the bat algorithm and its variants. Section 4 describes the experimental design, including the benchmark functions, parameter configurations, and evaluation metrics. Section 5 presents and analyzes the computational results. Section 6 provides a discussion of the findings, and Section 7 includes the conclusions and outlines future research directions.

Research Hypotheses

H1.

Solution Quality: The integration of directional scanning, adaptive mapping, and CFAR acceptance in Radar Bat leads to improved objective function values compared to the basic BA across a diverse set of benchmark functions.

H2.

Exploration–Exploitation Balance: The coordination of the three radar-inspired modules reduces premature stalling and promotes more robust convergence in multimodal spaces.

H3.

Inter-Run Robustness: Radar Bat exhibits less performance variability between independent runs compared to the basic BA, maintaining quality advantages even with longer computation times due to the additional cost of the modules.

2. Materials and Methods

This section describes in detail the structure and components of the proposed algorithm (Radar Bat), whose main basis is BA, which includes techniques inspired by maritime radars to improve exploration and exploitation in complex environments.

2.1. Radar-Type Directional Sweep

In maritime radar, scanning is used to systematically cover angular space. The objective of directional scanning is to generate multiple solutions around the best global solution, , in an orderly and efficient manner, using a directional pattern. The main goal of this technique is to generate and evaluate candidate solutions in several directions with controlled steps. This allows for intensified exploitation without losing angular diversity or repeatedly re-exploring the same area. Equations (1) and (2) represent the directional scanning for each direction, d, in a set of D directions:

where

- : Best global solution.

- : Displacement in the d direction.

- : Random vector in n dimensions.

- s: Step size.

Then, the objective function is evaluated using Equation (3):

And finally, in Equation (4), the following is selected:

2.2. Adaptive Map

The adaptive map acts as a dynamic log, identifying which areas of the search space have been frequently visited, as this can lead the algorithm to small local optima. Its main objective is to redirect the search towards less explored regions. It records the visit density per region, penalizes the most visited areas, and prioritizes exploration of less saturated areas. There are two ways to represent this component: The first is through a grid that partitions the continuous space into cells of a fixed size per dimension. The second is through a hash structure that stores only the cells that have been visited; this is useful in high dimensions or large domains. When a bat proposes a new position, xi, the cell counter on the map is incremented, as described by Equation (5):

where cell(xi) is the cell-containing position, xi. The density at position x is defined as the normalized count of its cell and is represented by Equation (6):

where

- density(x): normalized density in the cell containing x.

- cell(x): cell that contains position x.

- count[cell(x)]: number of visits to that cell.

- global mean: global average of visits across all cells, and 1 stabilizes the scale by preventing division by zero in the initial stages. To avoid visiting saturated zones, a correction is applied to the objective function, as shown in Equation (7):

- f(xi): original value of the objective function.

- λ > 0: density penalty factor (0 < λ ≤ 0.2).

- density(xi): normalized density in the cell containing x. This component is integrated with the BA acceptance rule of the adaptive CFAR, maintaining a controlled false acceptance rate.

2.3. Directional Sweep

The directional sweep can consult the map to prioritize directions, d, towards less explored regions. Given the candidate position generated by the radar-type direction sweep module, priority is defined according to Equation (8):

- priority(d): priority assigned to address d.

- d: candidate direction in the sweep.

- : average density in the region towards the d direction. Low density promotes a high priority of visiting search spaces, while high density has low priority and fewer attempts to explore those areas.

2.4. CFAR-Type Adaptive Threshold

This component is inspired by the CFAR technique. It dynamically adjusts according to the best current solution found, and the threshold is defined according to Equation (9):

where θt is the adaptive threshold at iteration t, is the best value found so far, δ is the adjustment factor, and is a random component for variability. The acceptance condition is defined as follows: Accept xi if and u < Ai, where represents a random number, and Ai is the bat amplitude that controls the acceptance probability. If the acceptance rule is met, the amplitude and pulse emission parameters are subsequently updated using Equations (5) and (6), respectively.

2.5. Proposed Radar-Bat Algorithm

In step 1 of Algorithm 1, the following parameters are initialized: the population size (n), the frequency range [fmin, fmax], the initial amplitude (Ai), the initial emission rate (ri) for each bat, the coefficients α and γ that control the updating of Ai and ri, and the iteration counter (t). Steps 2 through 4 initialize the exploration map, which divides the space into cells (in a grid or a hash structure). Each cell store visits a counter. The cell size, δ, is set. In steps 5 through 9, the initial population is created, where each bat, i, is assigned: a random position (xi), a random velocity (vi), and a frequency (fi) within the range [fmin, fmax]. In steps 10 and 11, the objective function, f(xi), is evaluated for all bats, and the initial best global solution, , is determined, respectively. In steps 12 and 13, while the stopping criterion is not met, t is incremented, and each bat is processed. In steps 15 to 18, a random number, β ∈ [0, 1], is generated, and the frequency, fi, is adjusted. Subsequently, the velocity, vi, is updated, and a new position, xi, is assigned. This process combines attraction to the best solution and controlled variation to search for improvements. In steps 19 to 29, if rand > ri, the bat activates a radar-like directional sweep around . This sweep allows for the generation of several unit directions, ϵ(d), and in each direction, a candidate solution, , is constructed. For each candidate solution, the density on the map is calculated, and an angular priority, (d), is obtained. Addresses with lower density receive higher priority; the top-k candidate directions are ordered and evaluated first (those with the most promising coverage). In steps 30 to 32, for the current position, xi, its cell is located, and the normalized density (local visits relative to the global average) is calculated. This density is used to adjust the evaluation of so that highly visited areas become slightly less attractive, thus promoting diversity. In step 33, an estimate of the depth level, Pn(t), is made from the reference cell (excluding the reference cell). In step 34, a dynamic threshold, Tt, is set. In step 35, a decision is made as to whether to accept xi to maintain a constant false acceptance rate, and it is determined which candidate solutions continue in the process. If xi is accepted, in steps 37 and 38 the amplitude, Ai, is decreased and the pulse emission rate, ri, is updated. If the new position improves the value of f, = xi is updated in step 41. Subsequently, in step 43, the visit counter for the cell of xi is incremented. This keeps the adaptive map updated on which regions are being explored. This process continues if there is no stopping criterion. Finally, the algorithm returns the best global solution found, .

| Algorithm 1. Radar-Bat Algorithm |

| Input: |

| Define objective function f(x) |

| Parameters/Variables: |

| n: number of bats |

| fmin, fmax |

| Ai: initial loudness |

| ri: initial rate |

| α, γ: update coefficients |

| t: iteration counter |

| Output: |

| : global best solution |

| 1: Initialize parameters |

| 2: //Initialize adaptive map |

| 3: : δ = cell size per dimension |

| 4: : count[cell] = 0 (or empty dictionary) |

| 5: for each bat i //Generate initial population |

| 6: xi = random position |

| 7: = random speed |

| 8: fi = random frequency in [fmin, fmax] |

| 9: end foreach |

| 10: Evaluate objective function f(xi) for all |

| 11: = best solution found |

| 12: while the stopping criterion is not met |

| 13: t = t + 1 |

| 14: for each bat i //BA standard update |

| 15: β ϵ [0, 1] random |

| 16: |

| 17: |

| 18: |

| 19: |

| 20: Generate a set of directions |

| 21: for each address |

| 22: |

| 23: |

| 24: |

| 25: |

| 26: end foreach |

| 27: Sort by descending priority(d) |

| 28: Evaluate candidates (top − k) and choose the best for trial |

| 29: end if |

| 30: //Evaluation penalized by map |

| 31: |

| 32: //CFAR threshold and acceptance |

| 33: average of over references (excluding for the reference cell) |

| 34: |

| 35: |

| 36: Accept xi |

| 37: |

| 38: |

| 39: end if |

| 40: //Global best |

| 41: |

| 42: end if |

| 43: //Map update (always) |

| 44: end foreach |

| 45: end while |

| 46: return |

| 47: end |

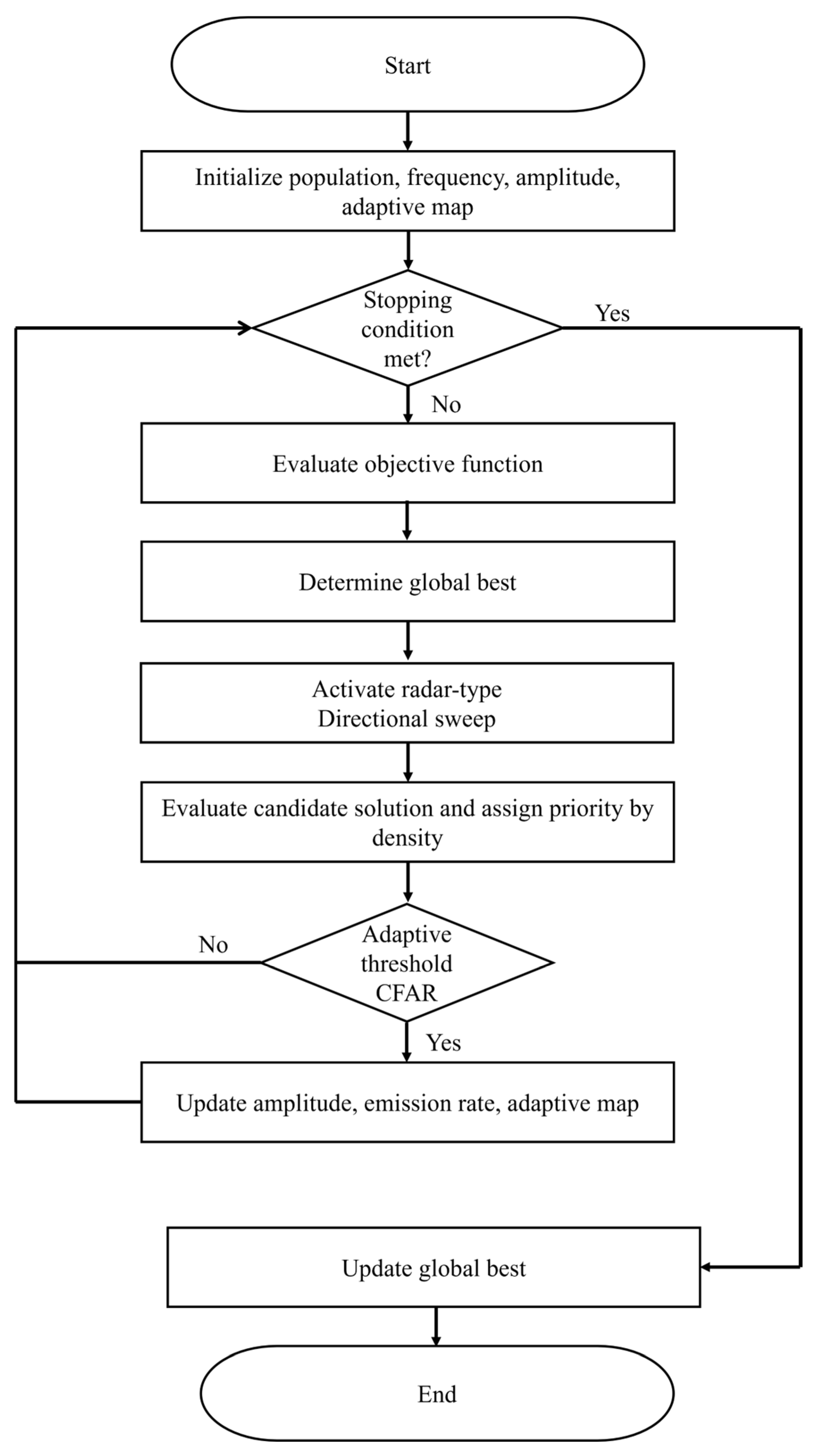

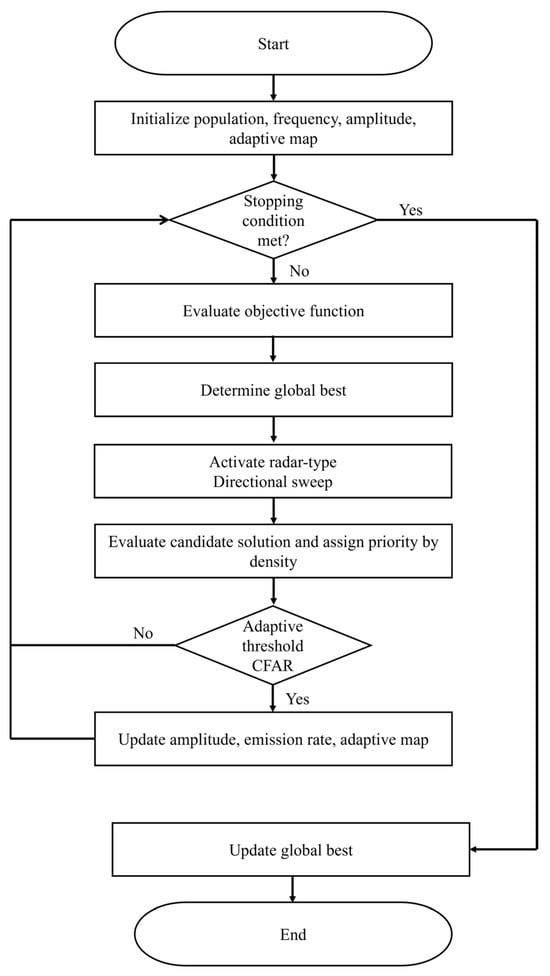

The above process is shown in Figure 1, where the interaction of all the elements incorporated in the Radar-Bat algorithm can be observed in a more general way.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the Radar-Bat algorithm process.

3. Related Work

This section describes previous studies and the most relevant developments related to basic BAs and their variants. The main idea is to provide an overview of the state of the art, identifying proposed improvements to overcome the limitations of the basic BA, such as premature convergence and a lack of diversity in multimodal spaces. Some approaches include hybrid techniques, multi-objective optimization, and decomposition-based strategies, as well as recent applications in areas such as reinforcement learning.

3.1. Bat Algorithm (BA)

The BA was first proposed in 2010 by Xin She [2] as a metaheuristic algorithm inspired by bat echolocation. The original basic version of the BA was validated by comparing it with a Genetic Algorithm (GA) and a Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm, respectively. The BA has certain limitations reported in the state of the art because it exhibits susceptibility to premature convergence, which causes problems with diversification, especially when the update is guided by the global best solution, leading to stagnation at local optima. Furthermore, its performance decrements in highly multimodal scenarios when the search process is not controlled [6,7]. The BA is described by the following equations where each bat, i, is characterized by its position (xi), velocity (vi), frequency (fi), amplitude (Ai) and pulse emission rate (ri). The frequency is updated using Equation (10):

where β ∈ [0, 1] represents a random number uniformly distributed between 0 and 1. This value is used to generate variations in the frequency, fi, of each bat, ensuring that the frequencies are distributed within the range fmin, fmax. This mechanism introduces controlled randomness, which helps to diversify the population, preventing all bats from clustering in the same search space. The speed is adjusted according to Equation (11):

where corresponds to the current velocity of bat i in iteration t, which is the velocity in iteration t − 1, and is the current best global solution. The bat’s position is updated using Equation (12):

where is the current position of the bat, and corresponds to the previous position. To intensify the local search, a new solution is generated through Equation (13):

where ϵ represents a random value in the range [−1, 1]. On the other hand, the amplitude is updated with Equation (14):

where represents the current amplitude of bat i at iteration t; this parameter controls the intensity of the local search, and α corresponds to a value (0 < α < 1) that progressively reduces the amplitude. To update the pulse emission rate of bat i at iteration t + 1, Equation (15) is used:

where is the initial value of the emission rate, γ is a control parameter that determines the rate of increase in emissions and that allows for regulation of the exploration and exploitation of the BA.

3.2. Variants of the BA

3.2.1. Multi-Objective Bat Algorithm (MOBA)

The BA was extended to multi-objective optimization (MOBA), integrating Pareto criteria and validating it on test functions and problems, such as the design of welded beams [8]. The most recent research explores MOBA with the State–Action–Reward–State–Action (SARSA) reinforcement learning strategy, showing improvements in frontline diversity and hypervolume [9]. Other decomposition-based approaches (MOBA/D) incorporate differential evolution operators to strengthen front diversity and uniformity [10].

3.2.2. Integrated BA with Functional Link Artificial Neural Network (BAT-FLANN)

The integration of the BA with a Functional Link Artificial Neural Network (BAT-FLANN) was applied to microarray data classification, where the BA optimizes classifier weights and outperforms basic FLANN techniques and the PSO FLANN algorithm [11]. The FLANN literature supports the use of the model as an efficient, low-complexity nonlinear approximator, which explains its compatibility with optimizers such as the BA [12,13,14].

3.2.3. Discrete BA (DABA/IDBA)

Several discrete versions of the BA have been proposed, such as the Directed Artificial Bat Algorithm (DABA) for discrete/combinatorial spaces. In the area of automatic multi-document summarization, the Discrete Bat Algorithm for Multi-Document Summarization (DBAT-MDS) has been developed, which is an improved version of the BA for working with discrete data, such as words or phrases, and incorporates improvements in the Recall-Oriented Study for Gisting Evaluation (ROUGE) metrics compared to other metaheuristic algorithms [15]. In the area of manufacturing, an improved discrete version called the Improved Discrete Bat Algorithm (IDBA) was designed, which replaces continuous formulas with adaptive operators and solves partial disassembly lines in parallel, clearly outperforming the NSGA II/III, SPEA II, and MOEA/D algorithms in real-world problems [16].

3.2.4. Binary BA (BBA)

To address binary problems, the Binary Bat Algorithm (BBA), an adaptation of the BA for discrete spaces, has been developed. Its efficiency has been validated through a comparative study of algorithms such as Binary Particle Swarm Optimization (BPSO) and the GA, using a set of 22 references functions. The results show a statically significant superiority, confirmed by the Wilcoxon non-parametric test, and its practical application in the design of optical buffers is also reported, highlighting its potential in telecommunication environments [17].

3.2.5. Enhanced BA (EBA)

The Enhanced Bat Algorithm (EBA) aims to prevent premature convergence through adaptive exploration and exploitation mechanisms, as well as population diversification. In the non-convex economic dispatch problem with 20 thermal units, the EBA reduces transmission costs and losses compared to the traditional BA and other methods and improves late-stage convergence [18]. In industrial control, the EBA has been used for tuning controllers in drilling processes and outperforms PSO and the Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) in timing specifications and error metrics [19].

3.2.6. Directional BA (dBA)

To improve search space exploration, the directional BA (dBA) is proposed, which introduces directional echolocation and three other improvements over the basic BA. These improvements demonstrate that the dBA is superior through tests performed on the standard set of reference functions from the 2005 Contest of Evolutionary Computation (CEC 2005) and non-parametric analyses [7,20]. It has also been applied in reliability-based design optimization (RBDO), integrating reliable design spaces and constraint handling using the ϵ − method [21].

3.3. Works That Include Radar-Inspired Techniques

3.3.1. Adaptive Constant False Alarm Rate (CFAR)

CFAR is a technique used in radars to dynamically adjust the detection threshold, maintaining a constant false alarm probability even in noisy and interfering environments. This technique prevents the radar from detecting multiple false targets when noise levels vary. Some existing variants have been improved with techniques such as fuzzy fusion and deep learning for complex environments like multiple-input multiple-output (MIMO) radars [22,23,24,25], among which the following stand out:

- Cell Averaging (CA-CFAR) calculates the threshold by averaging neighboring cells [26].

- Greatest Of (GO-CFAR) uses the higher value between two windows for environments with interference edges [22,27].

- Smallest Of (SO-CFAR) uses the lower value for scenarios with strong interference [22,28].

- Ordered Statistic (OS-CFAR) orders the samples and selects a specific position to calculate the threshold [29].

3.3.2. Systematic Directional Sweep

Radar systems perform mechanical or electric directional sweeps to systematically explore angular space [30,31]. Different patterns can be used to perform these sweeps, such as a fan beam, pencil beam, conical sweep, and monopulse, each designed to cover space with varying accuracy and speed [32,33,34]. The scanning process introduces losses that affect detectability [35], such as pulse eclipse, off broadside scanning losses, moving target indicator (MIT) losses, and CFAR losses [36,37].

3.4. Recent Advances in Metaheuristics and Applied Optimization

In recent years, metaheuristics have emerged to expand exploration and exploitation mechanisms, highlighting the importance of designs with coordinated modules and adaptive filters, such as those in Radar Bat. One example is the Schrödinger Optimizer, which incorporates quantum duality principles for stochastic optimization, achieving competitive results and demonstrating the trend toward integrating physical concepts into a global search [38].

Following the trend of local improvements coupled with swarm techniques, QPSOL combines quadratic interpolation and local search with PSO for photovoltaic parameter estimation, showing improvements in accuracy and convergence. This work illustrates how hybridizing an intensification scheme with the core of PSO allows for explicit modulation of the exploration–exploitation balance and reports advantages over recent CEC sets and real-world cases [39].

Additionally, Moth Flame algorithms enhanced with local escape operators (LEOs) have demonstrated increased diversity and escape of local optima in photovoltaic parameter estimation. The integration of LEOs emphasizes the value of adaptive local operators in stabilizing the acceptance rate of new solutions without sacrificing fine-tuning, an idea like the acceptance filters we use in Radar Bat [40].

Finally, on the large-scale scalability front, the Salp Swarm Algorithm with a Local Escaping Operator (SSALEO) has undergone extensive evaluations in CEC 2017, CEC 2008 Large-Scale Global Optimization (200–1000 variables), and restricted CEC 2020, demonstrating competitiveness (and in several cases superiority) against high-performance algorithms, with statistical validation (Wilcoxon/Friedman). These results underscore the importance of designing methods that maintain performance and stability as dimensionality increases or constraints tighten, aligning with our discussion of complexity, scalability, and trade-offs in Radar Bat [41].

All this evidence converges on two main trends: the first lies in the explicit coordination of modules (e.g., local intensification, escape operators, and adaptive thresholds), which improves robustness and quality, and the second concerns scalability, which requires controlling the additional cost of such modules. In this context, the proposed Radar-Bat algorithm offers a novel combination of systematic directional scanning, adaptive density mapping, and CFAR acceptance as a probabilistic filter for new solutions, integrated into a single flow to modulate the balance between exploration and exploitation. This solution method aligns with current trends and offers an interpretation inspired by radar principles (scanning, detection thresholds, and false alarm control) applied to contemporary metaheuristics.

3.5. Conceptual and Operational Differences of Radar Bat Compared to Existing Variants

Existing BA variants, designed to improve exploration and exploitation, include the dBA, which uses directional echolocation, and the EBA, which features adaptive diversification, among other hybrid approaches with various learning techniques for improved accuracy. Radar Bat is distinguished by its coordinated integration of three radar-inspired mechanisms that do not appear together in the previous literature:

- Systematic directional sweep with angular prioritization. Radar Bat generates multiple directions around the global best and prioritizes them based on density (lower density ⇒ higher priority). This avoids redundant assessments in saturated sectors and focuses exploitation on promising “angles,” while maintaining angular diversity. Unlike the dBA, which does not model spatial saturation or reorder directions by coverage, Radar Bat uses an explicit priority criterion linked to the adaptive map.

- Adaptive visit map and density penalty. The algorithm maintains a dynamic record of visit density per cell in the search space. This structure guides movement toward underexplored regions and applies a mild penalty during evaluation to discourage overvisited areas. This concept introduces explicit spatial control, absent in the basic BA, EBA, and dBA, which becomes crucial in multimodal functions with a high probability of premature convergence.

- Adaptive acceptance based on CFAR. Radar Bat dynamically adjusts an acceptance threshold relative to the current best value, regulating the incorporation of new solutions to maintain a constant false alarm rate. This mechanism acts as a probabilistic filter that protects the quality of the exploitation process without slowing down the scan and is not found in the dBA, the EBA, or multi-target/discrete variants.

Operational integration (coordinated flow): At the execution level, Radar Bat integrates the three modules into a single cycle: directional sweeping and querying the adaptive map to prioritize and penalize based on density and CFAR acceptance with amplitude and emission rate updates. This closed flow creates feedback between scanning (angular coverage and density) and exploitation (CFAR-filtered acceptance), offering a systematic balance that previous variants did not achieve in a unified way.

Methodological contribution: The combination of systematic scanning, spatial density control, and CFAR acceptance constitutes a novel methodological approach that translates radar detection and scanning principles to a bio-inspired metaheuristic, reinforcing robustness in multimodal spaces and improving the quality of solutions compared to the basic BA and reference variants. In our experiments, this integration resulted in significant improvements in the objective value for most of the evaluated functions (see Tables 5–7). Table 1 summarizes the conceptual and operational differences between Radar Bat and representative variants of the BA.

Table 1.

Conceptual and operational comparison between Radar Bat and representative variants of the BA.

3.6. Applications of the BA in Real-World Problems

The BA has proven to be a versatile tool for solving complex problems in various domains (see Table 2). Representative and recent examples illustrating its applicability are presented below:

Table 2.

Applications of the BA in different domains.

- Structural design and topology optimization: The BA has been used to optimize parameters in complex structures, achieving weight reduction and improved strength compared to traditional methods, such as the GA and PSO [43]. Variants such as the Binary Bat Algorithm have allowed for the elimination of gray areas in designs, generating manufacturable solutions [44].

- Industrial processes and manufacturing: Dao & Nguyen [4] report applications of the BA in production planning, supply chain management, and process optimization, highlighting improvements in efficiency and cost reduction.

- Smart systems and IoT: Improved versions of the BA have optimized routing and energy efficiency in IoT networks, helping to extend the lifespan of devices [45].

- Electrical systems and economic dispatch: The BA has been applied to the integration of renewable energy into electrical grids, reducing operating costs and improving system stability [46].

- Machine and federated learning: The FedBat variant has accelerated convergence in federated learning environments up to five times faster than FedAvg, with 40% improvements in accuracy [47]. Hybrid BA + GWO methods have also been developed to optimize the training of convolutional neural networks [48], improving classification on complex datasets.

- Mobile robotics: The Leader-Based Bat Algorithm (LBBA) has been applied to data fusion for robot localization, achieving greater accuracy and lower computational consumption [48].

4. Computational Experiments

This section describes a set of experiments designed to evaluate the performance of the proposed Radar-Bat algorithm against the basic BA. Twenty widely used benchmark functions from the optimization community were selected from the CEC 2005, CEC 2010, CEC 2017, and CEC 2020 suites. The parameters used, the computational environment, and the evaluation metrics considered are also described, including the objective value, execution time, and non-parametric statistical tests.

4.1. Benchmark Function Set

Table 3 presents information on the twenty mathematical functions used in this research. The first column represents the name of each function, and the second and third columns correspond to the lower and upper bounds, respectively. The fourth column represents the known optimum value [50]. Each algorithm was executed independently 30 times, and the averages of their 30 medians were calculated for the objective value (OV) and execution time (Time). The time used by the algorithms is measured in milliseconds.

Table 3.

Mathematical function values.

The selected test functions include a diverse set of twenty standard problems widely recognized in the literature, chosen to cover a broad spectrum of difficulty profiles and characteristics. This set comprises:

- Unimodal, convex and separable functions, which serve as a benchmark for measuring convergence speed and accuracy [51,52].

- Periodic multimodal functions, which are designed to evaluate exploration capacity and avoidance of local optima [53].

- Non-convex multimodal functions with external flat regions, which allow for the evaluation of the ability to escape plateaus and convergence toward narrow global wells [54,55,56].

- Ill-conditioned and non-separable functions, which test robustness in complex landscapes [57].

- Penalized and constrained functions, which included analyzing performance under constraint management and penalty-based adaptation [57].

This expanded selection ensures a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed algorithm in different modalities, separability conditions, and constrained scenarios, providing a more rigorous and representative validation. These twenty functions have known global optima and standard domains widely used in repositories [51,52,54,56]. Furthermore, they appear as canonical cases in recognized suites, such as CEC 2005, CEC 2010, CEC 2017 and CEC 2020, which guarantees traceability and comparability with the metaheuristic literature [50,56,57].

4.2. Variables/Parameters Used

Table 4 shows the assigned values of the variables and parameters used in computational experiments for the twenty functions.

Table 4.

Variables and parameters used to evaluate the twenty functions.

Most of the values assigned to the parameters of the proposed Radar-Bat algorithm were chosen from the state of the art of the BA and its experimental guidelines (e.g., frequency ranges, loudness and pulse rate schemes, and population sizes), in accordance with foundational reports and expert reviews [2,3]. Furthermore, the experimental design follows best practices from the CEC 2005, CEC 2010, CEC 2017, and CEC 2020 evaluation suites, which facilitates statistical comparison using non-parametric tests [53]. On the other hand, certain parameters specific to the radar module (e.g., the CFAR factor and window, as well as the number and coefficient of scan directions) were set through iterative experimental tuning to balance the false acceptance rate and computational cost, based on the principle of CA-CFAR [31].

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

To evaluate the performance of both algorithms, the following were used:

- The objective value (OV) achieved.

- The execution time (Time).

- Non-parametric statistical tests (Wilcoxon and Friedman), with a significance level of 5%.

These criteria follow standard recommendations in comparative studies of metaheuristics.

4.4. Computer Architecture and Software

The experiments were conducted under the following conditions: a computer with a Ryzen 7 processor, 16 GB of RAM, and a 512 GB SSD was used. The Microsoft Visual studio Community C# language software version 18.2.0 was used to implement the algorithms in a Windows 11 operating system environment.

5. Results

Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 show a performance comparison between the BA and the proposed improved version of Radar Bat on twenty benchmark functions. The first column represents the twenty functions used in the experiments; the second, the worst, best, and average measurements (the standard deviation is shown as a subscript in the average); and the third and fourth columns show the objective values (OVs) and the times at which the best solution (Time) is found for the algorithm being compared. The fifth and sixth columns show the objective value and the times at which the best solution is found, respectively. Columns seven and eight represent the p-values obtained from the non-parametric Wilcoxon test, with respect to OVs and Time respectively. The gray-shaded cell represents the lowest objective value or the shortest time at which the best solution is found, as applicable. The symbol ↑ represents a significant difference in favor of the proposed algorithm (Radar Bat). The symbol ↓ represents a significant difference in favor of the algorithm being compared (BA). The symbol = indicates that there is no significant difference in favor of either of the compared algorithms. The results show that Radar Bat achieves considerably lower OVs in most cases, indicating better optimization capabilities, while the BA maintains lower execution times.

Table 5.

Results obtained with the BA and Radar-Bat algorithms with 10 dimensions.

Table 6.

Results obtained with the BA and Radar-Bat algorithms with 30 dimensions.

Table 7.

Results obtained with the BA and Radar-Bat algorithms with 50 dimensions.

As can be seen, in terms of quality, the two algorithms perform similarly. In terms of efficiency, the BA is better on 11 of the 20 functions evaluated.

In the experiments with 30 dimensions, it can be observed that in terms of quality the proposed algorithm is better in 14 of the 20 functions evaluated, while in terms of efficiency it is better in 9 of the 20 functions evaluated.

The feasibility tests with 50 dimensions demonstrate that in terms of quality the proposed algorithm is better in 16 of the 20 functions evaluated, while in terms of efficiency it is better in 10 of the 20 functions evaluated.

Table 8 includes the p-values obtained by applying the non-parametric Friedman test, with a significance level of 5%, to evaluate the significance of the differences observed between the two solution methods.

Table 8.

Results obtained using Friedman’s non-parametric test.

Based on these results, it can be stated that the Radar-Bat algorithm is a competitive alternative to the BA and that incorporating techniques inspired by maritime radars to balance the exploration and exploitation of search spaces improves the performance of the algorithm. Even though the BA is more efficient, we can affirm that the proposed algorithm demonstrates a clear superiority in the quality of its results in terms of the objective function.

5.1. Sensitive and Robust Analysis of Parameters

An evaluation was performed on how moderate variations of Radar-Bat-specific parameters affect solution quality, computation time, and operational stability of the acceptance filter. The analysis focuses on the incorporated modules radar-type directional scanning, adaptive density mapping and a CFAR-type acceptance threshold, as previously defined in Section 2 and in Algorithm 1. The evaluated parameters are the following: the number of scanning directions, k; the CFAR factor, kcfar; the density penalty, α; the CFAR window size, wcfar; the step coefficients of the sweep, stepCoeff; and the size of the subset of top − k priority addresses according to low density. All these parameters are derived from the modules and rules described in Section 2.1, Section 2.2, Section 2.3 and Section 2.4 and in the Algorithm 1 flow. For the experimental design, an OFAT (one factor at a time) approach was used: for each parameter, a variation of ±20% with respect to its base value was applied (see Table 4), keeping the other parameters fixed. Each configuration was run independently on the set of 20 reference functions and in the 3 dimensions considered (10D, 30D and 50D), with 30 runs per case, following the general experimentation protocol of the article.

The metrics evaluated are OV, Time and acceptance rate (AR) (see Table 9), the latter defined as the percentage of proposed candidates that simultaneously satisfy the CFAR condition and the probabilistic restriction by amplitude in the Radar-Bat acceptance rule. This definition operationalizes the dynamics of Section 2.4, where acceptance requires f(xi) < θt and u < Ai for a u∼U(0, 1).

Table 9.

Sensitivity analysis of Radar-Bat parameters.

The density penalty is applied to a normalized density of the map and acts as an additive term in Equation (7), so its effect remains limited unless it posits excessive values. The CFAR threshold is adaptively adjusted around the best available value and, together with the amplitude condition, regulates the acceptance rate and the exploration–exploitation balance. These properties explain the stability observed in the aggregate results.

Main considerations:

- Number of sweep directions (k). Increasing the value of k enriches the angular coverage and tends to improve the OV to a point of diminishing returns. In parallel, it increases the cost per iteration (generation and evaluation of candidates) and can increase the Time if a moderate range is exceeded. In practice, a medium k, together with a cautious top k, offers good performance.

- CFAR threshold factor (kcfar). High values make the filter too strict (low AR and slower convergence), and low values make it permissive (high AR and risk of accepting lower quality candidates). Adjusting kcfar around the base value in Table 4 preserves a stable acceptance rate and good balance.

- Density penalty (λ). A moderate λ favors diversity and reduces stagnation. An excessive λ excessively penalizes useful regions and can degrade convergence. Since the density is normalized, its impact is gradual and controllable within ±20%.

- CFAR window size (wcfar). Larger windows stabilize the threshold (lower variance in AR) with marginal time costs. Small windows react faster but can induce volatility in acceptance.

- stepCoeff and top − k priority (low density). stepCoeff regulates the intensity of the directional displacement: very low values limit local exploitation. Very high prices increase unproductive revaluations. Selecting a top − k that is too large dilutes the focus; one that is too small reduces angular diversity.

Within the ±20% range, moderate robustness is observed: the changes in OVs and Time are consistent with the logic of the algorithm (quality improvements by reinforcing coverage and acceptance control, with controlled cost overruns), without evidencing structural instabilities. This behavior harmonizes with the results in Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7, where Radar Bat shows quality improvements over the BA in many features in 10D, 30D and 50D, with competitive times depending on the feature and dimensionality.

The recommended practical recommendation is to make an adjustment of k and kcfar initially, according to multimodality and temporal budgets; keep λ in a moderate range to preserve diversity without excessive penalty; choose wcfar that stabilizes AR without overdoing it; and configure stepCoeff and top − k to balance intensification and angular coverage.

5.2. Complexity, Scalability, and Quality–Time Trade-Offs

The Radar-Bat algorithm incorporates additional mechanisms (directional sweeping, adaptive mapping, and CFAR acceptance) that increase the computational cost compared to the basic BA. Each iteration includes:

- Directional sweeping: This involves the generation and evaluation of k addresses → additional cost is proportional to k × n (n = number of bats).

- Queries and updates of the adaptive map: This includes an operation O(1) per batch but with accumulated overhead in high-dimensional spaces.

- CFAR filtering: This involves a calculation of the dynamic threshold → cost O(1) per evaluation.

Therefore, the complexity per iteration changes from O(n) in the basic BA to approximately O(n × k) in Radar Bat, where k is the number of scan directions. Theoretically Radar Bat is more expensive, but empirically its time can be comparable or even less than the BA depending on the function and dimensionality, and this can be observed in the results in Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7.

Scalability:

- In low-dimensional problems (≤30 variables), the increase in time is moderate , while in high-dimensional problems (≥50 variables) it can exceed 4×, due to the increase in evaluations per sweep.

- The adaptive map scales well because it uses a hash structure, but the number of addresses, k, is the most critical factor.

Quality–time trade-offs:

- Radar Bat achieves significant improvements in quality (OV) in multimodal and complex functions, reducing premature convergence.

- Although Radar Bat incorporates additional mechanisms such as directional scanning, adaptive mapping, and CFAR filtering, experimental results show that the increase in computational cost does not always translate into longer execution times. On several benchmark functions in 10D, 30D, and 50D, Radar Bat matches or even outperforms the BA in runtime, and non-parametric tests do not indicate any consistent statistical advantage in favor of the BA in efficiency.

For applications with strict real-time constraints, it is still advisable to adjust parameters such as the number of scan directions, k, or the CFAR factor to control overhead. However, empirical evidence suggests that Radar Bat offers a favorable balance between quality and time, making it suitable not only for precision-oriented or offline problems but also for scenarios where moderate computational budgets are acceptable.

6. Discussion

The experimental results presented in Section 5 and synthesized in Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 allow us to analyze in detail the behavior of the proposed Radar-Bat algorithm compared to the basic BA, simultaneously considering solution quality, computation time, robustness between executions and parameter sensitivity.

6.1. Comparative Synthesis (OV vs. Time)

In terms of quality, Radar Bat achieves consistently lower target values on most test functions, particularly those that are multimodal and non-separable. This behavior aligns with the design of the method: systematic directional sweeping intensifies exploitation around the global best without losing angular diversity; the adaptive density map redirects the search towards underexplored regions; and the CFAR adaptive threshold filters out low-quality candidates when exploitation becomes dominant.

Regarding efficiency, although Radar Bat incorporates additional mechanisms that theoretically increase the computational cost, experimental results do not show a systematic disadvantage in execution time. Across several features and dimensions, Radar Bat matches (or even outperforms) the BA in runtime, and non-parametric tests do not indicate a consistent statistical advantage in favor of the BA. The effect of dimensionality and the number of sweep directions can increase cost in some cases, but the impact is not uniform across all benchmarks, reflecting an empirically favorable trade-off between quality and time.

6.2. Effect of Dimensionality

The advantage of Radar Bat in solution quality is consistently maintained at 10D, 30D and 50D for multiple functions. Although the theoretical computational cost increases with dimensionality, as iteration complexity grows from O(n) in the basic BA to approximately in Radar Bat, where k represents the number of scan directions, this does not always translate into proportionally longer execution times. In lower dimensions, the additional overhead tends to be moderate, while in higher dimensions the cost of the sweep mechanism can become more noticeable. Still, empirical results show that this temporal increase is not uniform across all benchmark functions, and in several cases Radar Bat matches or outperforms the BA in runtime. Overall, the gains in target value remain substantial, particularly in complex and multimodal functions, justifying the additional computational effort in scenarios where solution quality is a priority.

6.3. Robustness Between Independent Runs

Variability between runs decreases under Radar Bat, especially in features with highly multimodal landscapes. Two mechanisms explain this effect: the adaptive map penalizes saturated cells and encourages visiting little explored regions, and the CFAR stabilizes the acceptance rate of new solutions, avoiding degradations when exploitation intensifies. Section 5.1 suggests that this stability is maintained within reasonable configuration ranges.

6.4. Statistical Validity

Non-parametric tests (Wilcoxon and Friedman) support the previous observations: differences in objective value (OV) frequently favor Radar Bat, confirming its superior solution quality, while differences in execution time do not show a consistent statistical advantage in favor of the BA. In several benchmark functions, the runtimes of both algorithms are statistically indistinguishable, and in some cases Radar Bat even achieves lower times. Taken together, the statistical evidence supports the central hypothesis that the radar-inspired mechanisms improve the exploration–exploitation balance and the final solution quality, without implying a systematic increase in execution time across all functions and dimensions.

6.5. Parameter Sensitivity and Operational Trade-Offs

Section 5.1 identifies the number of sweep directions and the CFAR factor as the most influential parameters.

- Number of sweep directions (addresses): Increasing the number of directions enriches angular diversity but also adds computational overhead. Too many directions produce noticeable time growth with limited additional benefits, whereas reducing them excessively decreases directional coverage and weakens exploration.

- CFAR factor: A high CFAR value leads to excessive filtering, reducing the acceptance rate and slowing convergence. Conversely, a very low CFAR increases the acceptance of suboptimal candidates, which may degrade the final solution quality. Parameters such as the density penalty and CFAR window size exhibit moderate and stabilizing effects, helping maintain a controlled acceptance rate.

6.6. Practical Implications and Limits

- Radar Bat should be used: in offline scenarios, fine-accuracy optimization, or multimodal and complex problems where solution quality and robustness are a priority. Given its coordinated radar-inspired modules, it provides superior exploration–exploitation balance and more stable convergence, and empirical results show that its execution time can remain competitive depending on the problem and dimensionality.

- The BA should be used: when execution time is the primary constraint, particularly in scenarios with very high dimensionality and limited computational budget, or when a good-enough solution is acceptable. Its simpler structure ensures consistently low overhead.

- Current limitations: The additional mechanisms in Radar Bat introduce extra computational costs, especially when the number of sweep directions, k, is large; the algorithm is sensitive to parameters such as k and the CFAR factor; and its implementation is inherently more complex than that of the basic BA. These aspects must be considered when choosing between both methods.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

In this work, the Radar-Bat algorithm is proposed, an extension of the BA that integrates three radar-inspired mechanisms: systematic directional scanning with density-based angular prioritization, an adaptive visit map with penalties for saturated cells, and a CFAR-type acceptance threshold designed to maintain a controlled false acceptance rate. The methodology was experimentally validated on 20 benchmark functions from the CEC 2005/2010/2017/2020 suites and in three-dimensional settings (10, 30, and 50), comparing Radar Bat against the basic BA using objective values (OVs), runtime, and non-parametric Wilcoxon and Friedman tests at the 5% significance level.

- (H1) Solution quality. Confirmed. Radar Bat obtains lower OVs than the BA in most functions, with statistically significant differences in multiple cases. This advantage is most pronounced in multimodal, composition, and non-separable problems.

- (H2) Exploration–exploitation balance. Confirmed. The interplay between directional sweeping, the adaptive density map, and the CFAR acceptance rule reduces premature stagnation and promotes more robust convergence, as reflected in the OV improvements and the reduced dispersion between independent runs.

- (H3) Robustness between runs. Confirmed (with nuances). Radar Bat exhibits lower variability across independent executions, especially in multimodal functions. Although the added modules theoretically increase the computational cost, in practice, the execution time does not always increase proportionally, and in several functions Radar Bat matches or even outperforms the BA in runtime.

Advantages. Radar Bat consistently offers superior solution quality (OV) across most evaluated functions, with statistically validated improvements. It also mitigates local stagnation through directional sweeping and density-based prioritization, reduces variability between runs, and incorporates a CFAR mechanism that stabilizes acceptance rates during exploitation-dominated phases.

Disadvantages. Radar-inspired modules introduce additional computational overhead, particularly when the number of scanning directions, k, is large, and the algorithm is sensitive to the settings of both k and the CFAR factor, as extreme values can affect convergence or degrade the final quality. Additionally, Radar Bat requires more complex implementation than the basic BA due to the integration of the adaptive map and CFAR components. Another limitation of this research work is that Radar Bat was compared exclusively to the basic BA. This choice was intentional to isolate the contribution of radar-inspired mechanisms and avoid confounding effects arising from hybrid or other variant-specific improvements. However, in future work we will expand the comparison to include recent variants of the BA (e.g., the dBA and EBA) and other state-of-the-art methodology, with the goal of providing a broader and more comprehensive verification of the algorithm’s performance.

Based on these limitations, several improvement paths are suggested. Regarding computational costs, efficiency may be increased by adaptively adjusting the number of sweeping directions based on local landscape information, parallelizing sweeping and evaluations (including GPU acceleration) or incorporating intelligent sampling and surrogate models. For self-tuning, dynamically regulating the CFAR factor to maintain a target acceptance rate, applying phase-dependent density penalties, and using k-adaptive schedules to intensify scanning only in promising regions are promising strategies. In terms of scalability, extending Radar Bat to multi-objective problems through Pareto-based or vector-CFAR mechanisms, integrating feasibility-handling schemes for constrained optimization, and employing block-based or adaptive-subspace decomposition for high dimensionality are natural next steps. Finally, future evaluations should include optimization problems with noise or heterogeneous evaluation costs, real high-dimensional engineering tasks, and real-time scenarios that may benefit from accelerated or hybrid versions of Radar Bat. Finally, a more detailed analysis of the internal dynamics, including diversity metrics, trajectories or ablation studies, is outside the scope of this contribution but is considered a valuable line for future work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.A.G.-M.; methodology: R.S.-C.; research: R.S.-C.; software: B.M.-E.G.-M. and M.A.G.-M.; formal analysis: J.F.-S.; writing, proofreading, and editing: M.A.G.-M., B.M.-E.G.-M., J.R.-G. and J.F.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

B.M.-E.G.-M. thanks the Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación (SECIHTI), formerly CONAHCyT, for scholarship No. 4010284 for doctoral studies (CVU 464864).

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zebari, A.Y.; Almufti, S.M.; Abdulrahman, C.M. Bat algorithm (BA): Review, applications and modifications. Int. J. Sci. World 2020, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.S. A new metaheuristic bat-inspired algorithm. In Nature Inspired Cooperative Strategies for Optimization (NICSO 2010); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.S.; He, X. Bat algorithm: Literature review and applications. Int. J. Bio-Inspired Comput. 2013, 5, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, T.K.; Nguyen, T.T. A review of the bat algorithm and its varieties for industrial applications. J. Intell. Manuf. 2025, 36, 5327–5349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, S.U.; Rashid, T.A.; Ahmed, A.M.; Hassan, B.A.; Baker, M.R. Modified Bat Algorithm: A Newly Proposed Approach for Solving Complex and Real-World Problems. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.15318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, M.; Duhan, M. Bat algorithm: A survey of the state-of-the-art. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2015, 29, 617–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakri, A.; Khelif, R.; Benouaret, M.; Yang, X.S. New directional bat algorithm for continuous optimization problems. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, 69, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.S. Bat algorithm for multi-objective optimisation. Int. J. Bio-Inspired Comput. 2011, 3, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, C.L.; Cheng, C.S.; Shen, Y.H. A Reinforcement Learning-Based Multi-Objective Bat Algorithm Applied to Edge Computing Task-Offloading Decision Making. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jia, C.; Zhao, R. Multi-objective Bat Algorithm Based on Decomposition. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2015, 46, 316–324. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, S.; Shaw, K.; Mishra, D. A new meta-heuristic bat inspired classification approach for microarray data. Procedia Technol. 2012, 4, 802–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Chen, B. FLANN Adaptive Filter. In Efficient Nonlinear Adaptive Filters: Design, Analysis and Applications; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 83–161. [Google Scholar]

- Muja, M.; Lowe, D. Flann-Fast Library for Approximate Nearest Neighbors User Manual; Computer Science Department, University of British Columbia: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2009; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Muja, M.; Lowe, D.G. Flann, fast library for approximate nearest neighbors. In International Conference on Computer Vision Theory and Applications (VISAPP’09); INSTICC Press: Setúbal, Portugal, 2009; Volume 3, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, K.A.N.; Lakshmi, L.; Devi, K.D.S.; Rao, K.S.; Prasad, S.N.; Nookala, V. Discrete Bat Algorithm for Efficient Multi-Document Summarization. Ing. Syst. D’information 2024, 29, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Xing, Y.; Yao, M.; Wang, J.; Guo, X.; Qin, S.; Qi, L.; Huang, F. An improved discrete bat algorithm for multi-objective partial parallel disassembly line balancing problem. Mathematics 2024, 12, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Mirjalili, S.M.; Yang, X.S. Binary bat algorithm. Neural Comput. Appl. 2014, 25, 663–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, K.; Zhu, W.; Salleh, M.N.M.; Ali, H.; Talpur, N.; Naseem, R.; Ahmad, A.; Ullah, A. Enhanced bat algorithm for solving non-convex economic dispatch problem. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Soft Computing and Data Mining, Iizuka, Japan, 28–29 August 2019; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 419–428. [Google Scholar]

- Naji, R.M.; Dulaimi, H.; Al-Khazraji, H. An optimized PID controller using enhanced bat algorithm in drilling processes. J. Eur. Systèmes Autom. 2024, 57, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.S. (Ed.) Nature-Inspired Algorithms and Applied Optimization; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 744. [Google Scholar]

- Chakri, A.; Yang, X.S.; Khelif, R.; Benouaret, M. Reliability-based design optimization using the directional bat algorithm. Neural Comput. Appl. 2018, 30, 2381–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourouz, S.L.; Baadeche, M.; Soltani, F. Adaptive CFAR detection for MIMO radars in Pearson clutter. Signal Image Video Process. 2025, 19, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xiu, C. Adaptive Constant False Alarm Detector Based on Composite Fuzzy Fusion Rules. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunbo, X.I.U.; Yifan, L.I. Adaptive Constant False Alarm Rate Detector Based on Long Short-term Memory Network. Radioengineering 2025, 34, 132–142. [Google Scholar]

- Salem, A.I.; Hafez, A.E.D.S.; Amar, A.S. Intelligent Adaptive CFAR for Radar Signal Processing. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Telecommunications Conference (ITC-Egypt), Alexandria, Egypt, 13–15 July 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Shrivathsa, V.S. Cell averaging-constant false alarm rate detection in radar. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. IRJET 2018, 7, 2433–2438. [Google Scholar]

- Kamal, M.S. Multi-Target. Detection in Cutter-Edge environments using modified GOCFAR. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2016, 7, 330–344. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. CFAR-based interference mitigation for FMCW automotive radar systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 23, 12229–12238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohling, H. Radar CFAR thresholding in clutter and multiple target situations. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2007, 4, 608–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stimson, G.W.; Griffiths, H.D.; Baker, C.J.; Adamy, D. Stimson’s Introduction to Airborne Radar, 3rd ed.; SciTech Publishing: Raleigh, NC, USA, 2014; Available online: https://web.xidian.edu.cn/junli/files/20140415_104344.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Skolnik, M.I. Radar handbook. IEEE Aerosp. Electron. Syst. Mag. 2008, 23, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, D.D. Tracking Radar. In Radar Handbook, 3rd ed.; Skolnik, M.I., Ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2008; Available online: http://www.helitavia.com/skolnik/Skolnik_chapter_18.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Barrett, R. AP3302—Radar Theory. RAF STTN. Available online: http://www.radarpages.co.uk/theory/ap3302/sec1/ch3/sec1ch334.htm (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Sherman, S.M.; Barton, D.K. Monopulse Principles and Techniques, 2nd ed.; Artech House: Norwood, MA, USA, 2011; Available online: https://api.pageplace.de/preview/DT0400.9781608071753_A25417435/preview-9781608071753_A25417435.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- MathWorks. Introduction to Scanning and Processing Losses in Pulse Radar. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/help/radar/ug/introduction-to-scanning-and-processing-losses-in-pulse-radar.html (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- MathWorks. cfarloss—Loss Due to CFAR Adaptive Processing (Gregers-Hansen Universal Curve). Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/help/radar/ref/cfarloss.html (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Antipov, I.; Baldwinson, J. Estimation of a Constant False Alarm Rate Processing Loss for a High-Resolution Maritime Radar System; No. DSTOTR2158; Defence Science and Technology Organization (DSTO): Canberra, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, N.K.; Qaraad, M.; El Najjar, A.M.; Farag, M.A.; Elhosseini, M.A.; Mirjalili, S.; Guinovart, D. Schrödinger optimizer: A quantum duality-driven metaheuristic for stochastic optimization and engineering challenges. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 328, 114273. [Google Scholar]

- Qaraad, M.; Amjad, S.; Hussein, N.K.; Farag, M.A.; Mirjalili, S.; Elhosseini, M.A. Quadratic interpolation and a new local search approach to improve particle swarm optimization: Solar photovoltaic parameter estimation. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 236, 121417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaraad, M.; Amjad, S.; Hussein, N.K.; Badawy, M.; Mirjalili, S.; Elhosseini, M.A. Photovoltaic parameter estimation using improved moth flame algorithms with local escape operators. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2023, 106, 108603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaraad, M.; Amjad, S.; Hussein, N.K.; Mirjalili, S.; Halima, N.B.; Elhosseini, M.A. Comparing SSALEO as a scalable large scale global optimization algorithm to high-performance algorithms for real-world constrained optimization benchmark. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 95658–95700. [Google Scholar]

- Rujan, L.; Neagoe, V.E. A Hybrid Technique Based on Fusion of Bat Algorithm (Ba)-Grey Wolf Optimizer (Gwo) Deep Cnn for Classification of Military Ground Vehicles in Sar Aerial Imagery. In Proceedings of the 2025 17th International Conference on Electronics, Computers and Artificial Intelligence (ECAI), Târgoviște, Romania, 26–27 June 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.S.; Hossein Gandomi, A. Bat algorithm: A novel approach for global engineering optimization. Eng. Comput. 2012, 29, 464–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafer, A.A.; Al-Bazoon, M.; Dawood, A.O. Structural topology design optimization using the binary bat algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, R.; Kannagi, L.; Karthikeyan, G.; Ratheesh, R.; Abijith, G.R. An Improved Bat Optimization Algorithm for Knowledge Discovery for Routing and Energy Efficiency in the Internet of Things Environment. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Innovative Computing, Intelligent Communication and Smart Electrical Systems (ICSES), Chennai, India, 12–13 December 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, H.; Liu, Y.; Shen, Y.; Li, F.; Man, Y. A hybrid bat algorithm for economic dispatch with random wind power. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2018, 33, 5052–5061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, C. Rapid Federated Learning Powered by Bat Algorithm. In Neural Information Processing; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 16–31. [Google Scholar]

- Araujo-Neto, W.; Olivi, L.R.; Villa, D.K.D.; Sarcinelli-Filho, M. Data fusion applied to the leader-based bat algorithm to improve the localization of mobile robots. Sensors 2025, 25, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naser, M.Z.; Al-Bashiti, M.K.; Tapeh, A.T.G.; Eslamlou, A.D.; Naser, A.; Kodur, V.; Hawileeh, R.; Abdalla, J.; Khodadadi, N.; Gandomi, A.H. A review of 315 benchmark and test functions for machine learning optimization algorithms and metaheuristics with mathematical and visual descriptions. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.09581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surjanovic, S.; Bingham, D. Sphere Function. Simon Fraser University (SFU)—Optimization Test Problems. Available online: https://www.sfu.ca/~ssurjano/spheref.html (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- BenchmarkFcns. Sphere Function. Available online: https://benchmarkfcns.info/doc/spherefcn.html (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- García-Portugués, E.; Verdebout, T. sphunif: Uniformity Tests on the Circle, Sphere, and Hypersphere. Vignette. CRAN R-Project. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/sphunif/vignettes/sphunif.html (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Surjanovic, S.; Bingham, D. Ackley Function. Simon Fraser University (SFU)—Optimization Test Problems. Available online: https://www.sfu.ca/~ssurjano/ackley.html (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Ackley, D. A Connectionist Machine for Genetic Hillclimbing; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 28. [Google Scholar]

- Molga, M.; Smutnicki, C. Test Functions for Optimization Needs (Technical Report). 2005. Available online: https://robertmarks.org/Classes/ENGR5358/Papers/functions.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Suganthan, P.N.; Hansen, N.; Liang, J.J.; Deb, K.; Chen, Y.P.; Auger, A.; Tiwari, S. Problem Definitions and Evaluation Criteria for the CEC 2005 Special Session on Real-Parameter Optimization; KanGAL Report; 2005005; Nanyang Technological University: Singapore, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.; Raju, S. Metaheuristic optimization algorithms: A comprehensive overview and classification of benchmark test functions. Soft Comput.-A Fusion Found. Methodol. Appl. 2024, 28, 3123. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.