Abstract

Water with a high fluoride content poses a serious threat to both public health and the natural environment. To enhance fluoride ion removal efficiency, a modified activated carbon adsorbent (HPAC-La) was synthesized by impregnating soybean protein in a lanthanum nitrate solution, followed by freezing–drying and carbonization. The results confirmed that lanthanum nitrate modification significantly improved the adsorption performance. Under optimised experimental conditions (pH = 2.0, [F−] = 300 mg·L−1, 12 h, 298 K), HPAC-La exhibited a maximum adsorption capacity for fluoride ions of 126.7 mg·L−1, significantly higher than that of unmodified HPAC (86.1 mg·L−1). The adsorption process followed the pseudo-second-order kinetic model and the Langmuir isotherm model, indicating monolayer chemisorption. The mechanism involves ion exchange via surface hydroxyl groups and fluoride coordination with La sites. This study proposes a method for developing highly efficient adsorbents for the treatment of fluoride-contaminated wastewater.

1. Introduction

Fluoride, often introduced into the human body through drinking water, plays a recognized role in dental caries prevention. However, excessive intake, particularly from fluoride-contaminated groundwater, poses significant health risks to dependent populations [1]. According to World Health Organization statistics, fluoride and arsenic are among the most harmful inorganic pollutants globally [2]. While arsenic contamination in groundwater has attracted widespread attention, the severity of fluoride pollution in drinking water has long been underestimated. Over the past decade, new areas of groundwater fluoride contamination have been identified across multiple regions worldwide, with over 100 countries reporting fluoride levels in groundwater exceeding the World Health Organisation’s safety standard of 1.5 milligrams per litre [3]. Current mainstream defluoridation technologies face significant limitations: chemical precipitation tends to generate secondary sludge pollution [4]; ion exchange is susceptible to interference from coexisting ions and entails high regeneration costs [5]; and membrane separation suffers from high energy consumption and challenges in concentrate treatment [6]. In contrast, adsorption is regarded as one of the most promising approaches for fluoride removal, owing to its operational simplicity, low cost, and environmental compatibility [7,8]. In particular, rare earth-modified biomass adsorbents not only retain the advantages of traditional adsorbents but also enhance adsorption capacity to 2–3 times that of commercial activated alumina through rare earth modification. This approach simultaneously avoids secondary pollution issues, offering a novel solution for advanced fluoride removal from industrial wastewater. However, rare earth-modified adsorbents may also face the challenge of the leaching of rare earth elements. Consequently, highly efficient, environmentally sound, and safe adsorbents represent the future of fluoride removal methods [9,10,11,12].

Depending on the type of adsorbent materials, adsorbents can be broadly classified into carbon-based adsorbents (such as activated carbon, graphene oxide (GO), bone char, and carbon nanotubes (CNTs)), metal-based adsorbents (including aluminum-based, iron-based, and rare-earth metal-based adsorbents, etc.), bio-adsorbents (such as lignite and lignin), and polymeric adsorbents (including ion-exchange resins and chitosan (CS)). Among these, carbon-based materials have become a major research focus owing to their exceptional mechanical properties, substantial specific surface area, outstanding electrical conductivity, compact size, and well-developed porous structure [13].

Previous research has demonstrated that modified activated carbon can exhibit enhanced fluoride uptake. For instance, Wan et al. [14] discovered a fluoride adsorption capacity of 85 mg·g−1 using magnesium-modified peanut shell activated carbon, while Zhang et al. [15] confirmed that aluminum modification significantly improves the defluoridation performance of biochar. Aworn et al. [16] investigated the effects of different activators (CO2 and steam) and activation temperatures on the pore structure and specific surface area of activated carbon using raw materials such as nutshells, corncobs, bagasse, and sawdust. The study demonstrated that even under relatively mild activation conditions at 500 °C, the aforementioned biomass feedstocks can yield activated carbon possessing a remarkably high specific surface area and abundant pore structure. Yadav et al. [17] prepared three types of activated carbon from sawdust, wheat straw, and bagasse, respectively. For fluoride-contaminated water at a concentration of 5 mg/L, their removal rates were 49.8%, 40.2%, and 56.4%, respectively, with maximum adsorption capacities of 1.73 mg/g, 1.93 mg/g, and 1.15 mg/g. Notably, a relatively high dosage of activated carbon was required, reaching 4 g/L, and the materials lacked the ability to be regenerated for repeated use. Sidique et al. [18] prepared two types of adsorbents, AC-CLP250 and AC-CLP500, by carbonizing local calamansi peels (Citrus microcarpa, CLP) mixed with a specific concentration of FeCl3 solution. The results indicated maximum adsorption capacities of 4.926 mg/g and 9.79 mg/g, respectively. Bkhta et al. [19] developed activated carbon using date palm waste (from date palm trees) as raw material, achieving a maximum adsorption capacity of 13.03 mg/g. Montoya et al. [20] synthesized a new activated carbon by modifying walnut shell-derived activated carbon with an acidified eggshell solution, which exhibited a maximum adsorption capacity of 2.3 mg/g. Jeyaseelan et al. [21] prepared sulfonated graphene oxide (SGO) as an adsorbent for fluoride removal by modifying graphene oxide (GO) with sulfonic acid. The SGO material is rich in sulfonic acid groups, which significantly enhances its adsorption performance. The adsorption behavior conforms to the Langmuir isotherm model, with a maximum adsorption capacity of 4.26 mg/g. Kanrar et al. [22] first synthesized a Fe3+–Al3+ mixed oxide (HIAMO) via chemical precipitation, and then synthesized a novel adsorbent, GO-HIAMO, using graphene oxide (GO) as a substrate. Fluoride removal experiments demonstrated that this adsorbent achieved an optimal adsorption capacity of 27.75 mg/g at 45 °C. Ruan et al. [23] prepared HAMWCNTs composite material using an in situ sol–gel method, which exhibited a maximum fluoride adsorption capacity of 30.22 mg/g. The adsorption process was identified as a spontaneous endothermic reaction, demonstrating a high initial adsorption rate. Affonso et al. [24] prepared a novel adsorbent, CNTs-CS, using carbon nanotubes (CNTs) produced by Nanostructured & Amorphous, Inc. and chitosan (CS) with a deacetylation degree of approximately 85%, with glutaraldehyde as the crosslinking agent. Experimental results indicated a maximum adsorption capacity of 975.4 mg/g. When treating actual fluoride-containing water, the adsorbent maintained effective adsorption–desorption capabilities over five cycles, with a regenerated adsorption capacity as high as (130.0 ± 6.0) mg/g, and consistent adsorption performance across all subsequent cycles.

According to the Lewis Hard-Soft Acid-Base theory, La3+, as a typical hard acid metal, shows a strong affinity for the hard base fluoride ion. In this study, soybean protein, rich in carboxyl (-COOH) and hydroxyl (-OH) groups, serves as an ideal hard base ligand to coordinate with La3+, forming a stable La3+-protein complex that enhances fluoride adsorption. The rare earth element lanthanum not only exhibits excellent fluoride adsorption performance but also offers advantages such as low toxicity and cost-effectiveness [25]. Liu Dekun’s team [26] significantly enhanced defluoridation efficiency using La/Ce-modified mesoporous alumina. Liang et al. [27] synthesized a novel nanocomposite adsorbent (La-NDMP) by loading lanthanum (La) hydroxide onto a magnetic polyacrylic anionic resin (NDMP), forming hydrated rare earth metal oxides. This material exhibits outstanding fluorine adsorption performance at 318 K, with an adsorption capacity as high as 41.46 mg/g. Asare et al. [28] prepared an adsorbent by sequentially modifying fly ash-derived zeolite with lanthanum and cellulose. This adsorbent demonstrates outstanding performance, achieving a maximum adsorption capacity of 98.33 mg/g. Anu Ratthika et al. [29] prepared a lanthanum-assisted aluminum metal-organic framework (LaAl@MOF) via the co-precipitation method for fluoride adsorption. The LaAl@MOF exhibited excellent fluoride removal performance, with an adsorption capacity of 140 mg·g−1.

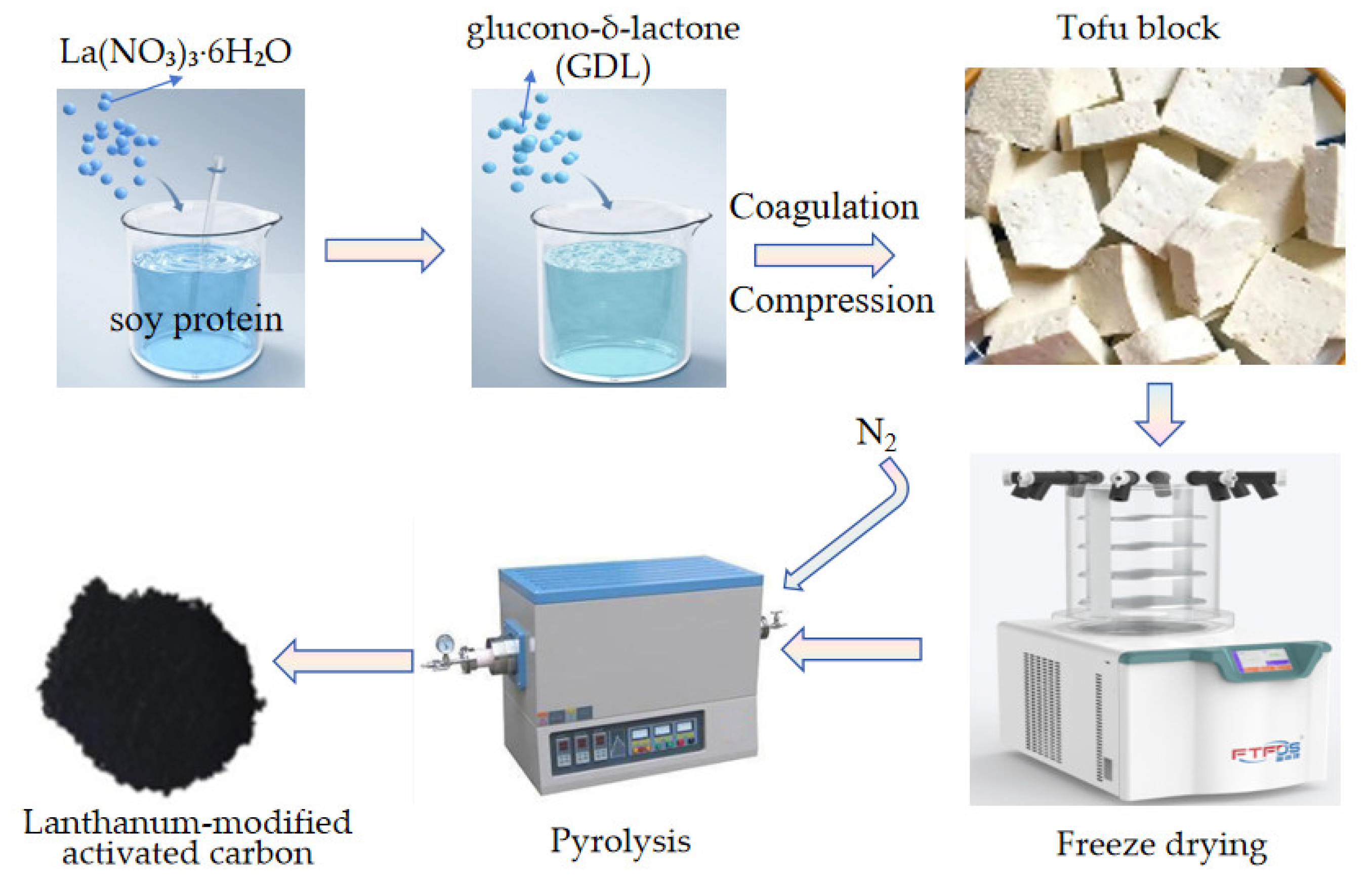

Therefore, unlike conventional modification methods that often involve post-synthesis impregnation or surface functionalization of pre-formed carbon, this study introduces an in situ integration approach. Lanthanum-modified activated carbon (HPAC-La) was prepared by mixing soybean protein with lanthanum nitrate, forming a bean curd-like block which was then freeze–dried and pyrolyzed. By mixing soybean protein with lanthanum nitrate to form a gel-like precursor prior to carbonization, the La species are uniformly embedded within the carbon matrix during its formation. This not only enhances dispersion and stability of active sites but also avoids the common issue of metal leaching associated with surface-loaded adsorbents.

For comparison, the non-lanthanum-modified carbon (HPAC) was obtained through the same procedure without adding lanthanum nitrate. This study employed a multi-parameter system to investigate the influencing factors of adsorption performance, such as pH value, temperature, contact time, fluoride ion concentration, and adsorbent dosage. Based on adsorption kinetics, isotherm experiments, and material characterization, the adsorption mechanisms of HPAC and HPAC-La were elucidated. Moreover, this study focuses on: (i) synthesizing La-modified porous carbon, (ii) evaluating its fluoride adsorption performance under varying conditions, and (iii) elucidating adsorption mechanisms through kinetics, isotherms, and material characterization, providing guidance for the optimization of material design and the enhancement of fluoride removal efficiency.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

Soy milk, sodium hydroxide (NaOH, Analytical Reagent, AR), lanthanum nitrate hexahydrate (La(NO3)3·6H2O, AR), sodium fluoride (NaF, AR), hydrochloric acid (HCl, AR), sodium chloride (NaCl, AR), sodium citrate (Na3C6H5O7, AR), glacial acetic acid (CH3COOH, AR), glucono-δ-lactone (GDL, AR), and fluoride ion calibration solution (1 mol·L−1) were used as raw materials. All chemicals and reagents used in this study were purchased from Nanning Blue Sky Laboratory Equipment Co., Ltd. (Nanning, China).

2.2. Characterization Techniques

Fourier transform infrared spectra (FT-IR) (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) of the adsorbent HPAC-La before and after adsorption were obtained at room temperature. Surface elements were analysed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) using an ESCALAB 250Xi spectrometer (ThermoFisher SCIENTIFIC, Waltham, MA, USA). Following Shirley-type background subtraction, high-resolution XPS peaks underwent subcomponent analysis using the XPS Peak 4.1 software package with a mixed Lorentzian–Gaussian function. During curve fitting, the peak widths (full width at half maximum or fwhm) of all components within specific spectra were maintained constant. Samples were referenced to the C1s sp2 peak at 284.6 eV. The microstructure of the material was characterised using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) (Phenom Pro 800-07334, Phenom-World Corporation, Eindhoven, North Brabant, The Netherlands). The specific surface area was determined by nitrogen adsorption–desorption measurements (BET method, Micromeritic TRISTAR II 3020, Micromeritics Instrument Corporation, Norcross, GA, USA). The fluoride ion concentration in solution was determined using the ion-selective electrode method, employing a fluoride ion-selective electrode (Shanghai Sanxin MP517 benchtop sodium ion concentrator, Shanghai, China), a saturated calomel reference electrode, a thermometer, and a magnetic stirrer.

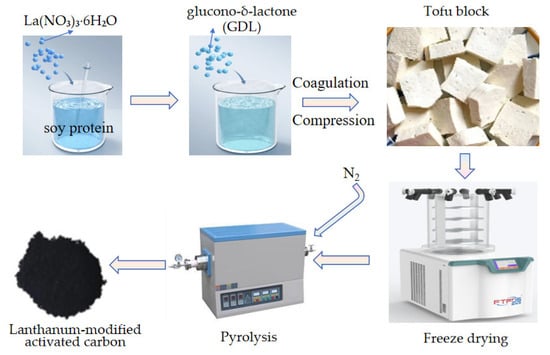

2.3. Activated Carbon Modification Procedure

A volume of 100 mL of 0.1 mol·L−1 lanthanum nitrate solution was prepared by dissolving 3.2492 g of lanthanum nitrate hexahydrate (La(NO3)3·6H2O) in deionized water. This solution was then thoroughly mixed with 500 mL of soy milk under continuous stirring. The mixture was maintained at a constant temperature of 90 °C in a water bath for 10 min, followed by the addition of 1.5 g of glucono-δ-lactone (GDL) to induce cooling and coagulation. The coagulated product was transferred into a tofu mold, pressed into blocks, and freeze–dried. Finally, the freeze–dried blocks undergo carbonization treatment in a tube furnace: the mixture is heated at a rate of 5 °C/min to 300 °C, 600 °C, and 750 °C under a continuous nitrogen flow (0.1 L/min). After holding at each temperature for 2 h, the material is allowed to cool naturally to yield the modified adsorbent material, as presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The preparation scheme of lanthanum-modified activated carbon (HPAC-La).

2.4. Fluoride Ion Measurement and Adsorption Methods

2.4.1. Fluoride Ion Measurement Method

The fluoride ion concentration was determined using an ion-selective electrode (ISE) method. Prior to analysis, the fluoride-selective electrode was calibrated with standard fluoride solutions corresponding to pF values of 3.00 and 5.00. For each measurement, the sample solution was mixed with a total ionic strength adjustment buffer (TISAB, prepared from sodium citrate and sodium chloride) at a volume ratio of 1:1 in a beaker equipped with a magnetic stir bar. The electrode was thoroughly rinsed with deionized water, gently dried, and then immersed in the mixed solution. The solution was stirred at a low, constant speed, and the stabilized meter reading was recorded as the fluoride ion concentration.

2.4.2. Adsorption Method

The adsorption performance of the adsorbent towards fluoride ions was evaluated using a single-variable control method. A fluoride stock solution with a concentration of 300 mg·L−1 was first prepared, and its pH was adjusted using 1 mol·L−1 HCl or 1 mol·L−1 NaOH as required. Subsequently, 0.01 g of the adsorbent was accurately weighed and added to 20 mL of the fluoride solution in a 30 mL glass vial. The mixture was agitated in a constant-temperature shaker at 140 r·min−1 to ensure sufficient contact between the adsorbent and the solution. After equilibration, the suspension was filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane. The fluoride ion concentrations before and after adsorption were determined, and the adsorption capacity Q (mg·g−1) and removal efficiency E (%) were calculated according to the following equations:

where C0 (mg·L−1) denotes the initial fluoride ion concentration, C1 (mg·L−1) represents the fluoride ion concentration in the solution after adsorption, and Ct (mg·L−1) is the fluoride ion concentration in the solution at time t. V (L) is the volume of the solution, and m (g) is the mass of the adsorbent.

2.4.3. Data Fitting Models

The Pseudo-First-Order (PFO) [30] and Pseudo-Second-Order (PSO) [31] kinetic models were used to fit the experimental data. The specific formulas are as follows:

where k1 (min−1) is the PFO kinetic rate constant, k2 (g·mg−1·min−1) is the PSO kinetic rate constant, Qe (mg·g−1) denotes the amount of metal ions adsorbed per unit mass of adsorbent at equilibrium, and Qt (mg·g−1) represents the amount of metal ions adsorbed per unit mass of adsorbent at time t (min).

In the isothermal adsorption experiments, the Langmuir [32] and the Freundlich [33] isotherm models were employed to fit the experimental data in order to elucidate the adsorption behavior of fluoride ions on the adsorbent. The corresponding equations are given as follows:

where Qe (mg·g−1) is the adsorption amount at equilibrium; Ce (mg·L−1) is the ion concentration in the solution at adsorption equilibrium, Qmax is the maximum adsorption capacity from the adsorption experiment, KL (L·mg−1) is the Langmuir constant, Kf (mg1−n·Ln·g−1) is the Freundlich constant, and n is a coefficient related to adsorption intensity.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of Modifier and Pyrolysis Temperature on Fluoride Ion Adsorption

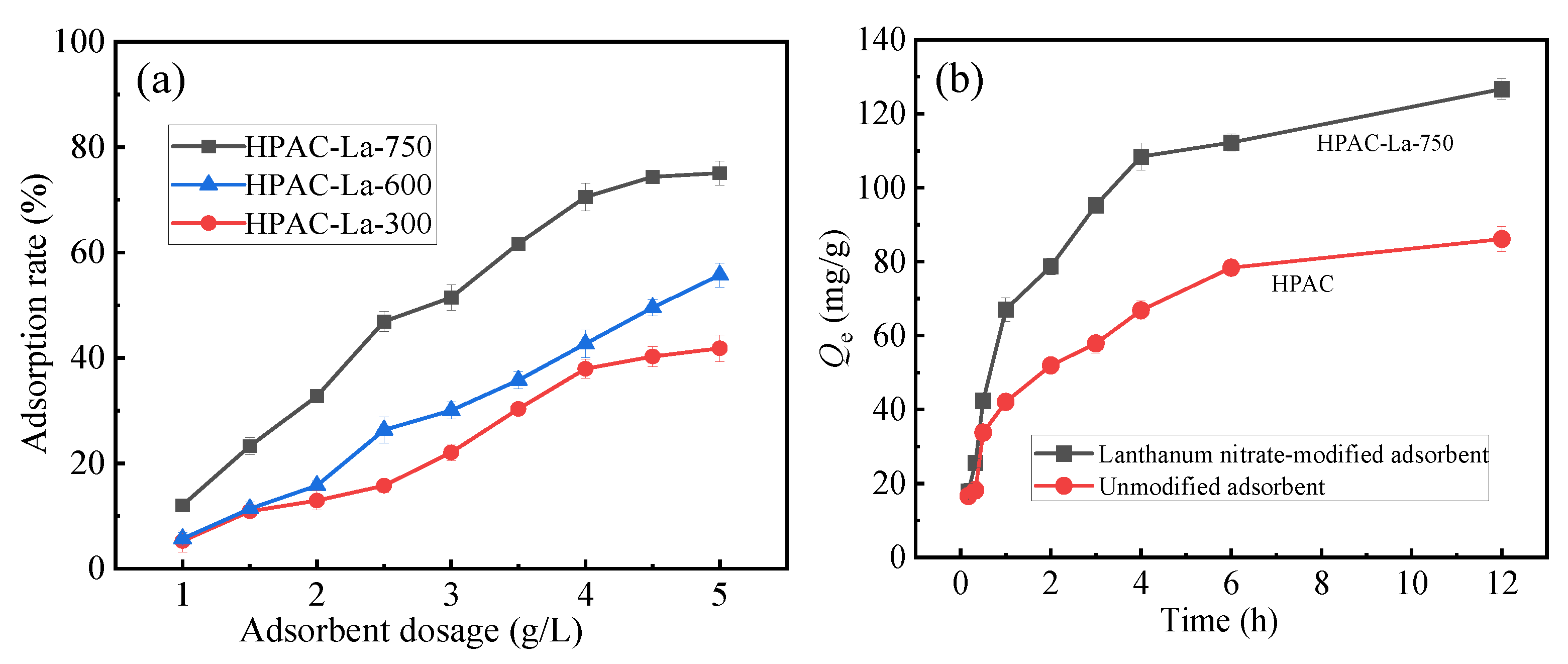

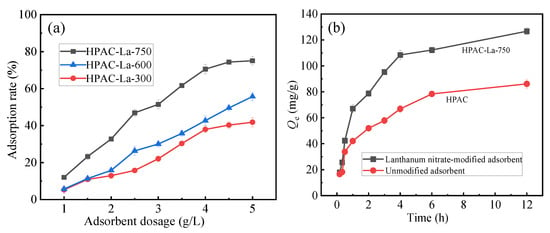

To enhance the fluoride removal efficiency of the adsorbent material, the regulatory effects of modifier type and pyrolysis temperature on adsorption performance were investigated. All adsorption experiments were conducted under the following conditions: 20 mL of a fluoride solution with a pH of 2 and a concentration of 300 mg·L−1 was shaken in a water bath shaker at 298 K for 10 min to 12 h.

As shown in Figure 2a, the effects of pyrolysis temperatures at 300 °C (HPAC-La-300), 600 °C (HPAC-La-600), and 750 °C (HPAC-La-750) were investigated. The results demonstrate that the adsorbent calcined at 750 °C (HPAC-La-750) showed a substantially higher fluoride ion removal efficiency than those prepared at lower temperatures. Based on these observations, lanthanum nitrate and a pyrolysis temperature of 750 °C were identified as the optimal modification conditions and were therefore adopted for all subsequent experiments. As shown in Figure 2b, the adsorbent modified with lanthanum nitrate exhibited markedly enhanced adsorption performance compared with the unmodified biochar.

Figure 2.

(a) Effect of different pyrolysis temperatures on adsorption performance, (b) effect of lanthanum modification on adsorption performance.

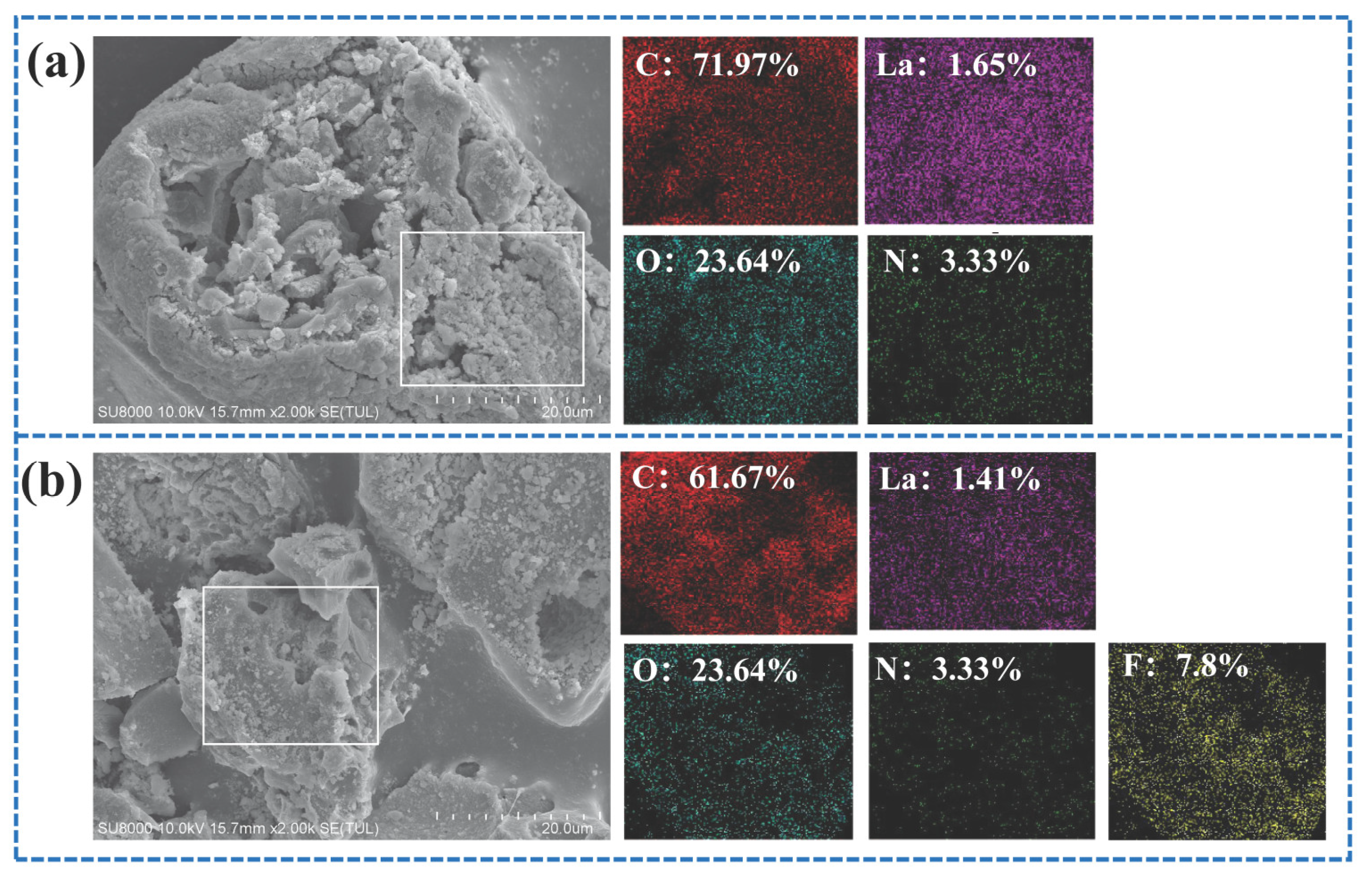

3.2. Materials Characterization (SEM-EDS and BET Analysis)

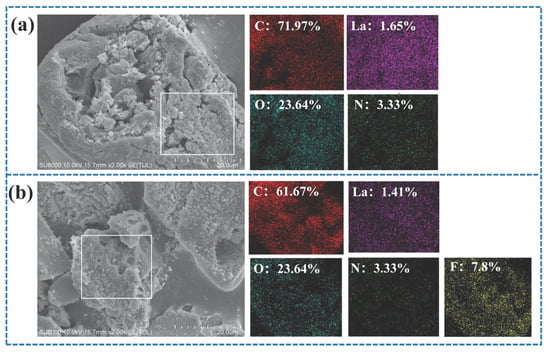

Figure 3a,b present the Energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) spectra of the soybean protein biochar, illustrating the elemental composition before and after fluoride adsorption. Prior to adsorption, the biochar exhibited a well-developed pore structure, providing abundant channels and active sites for fluoride ion diffusion and uptake. As shown in Figure 3a, the biochar contained carbon (C), oxygen (O), nitrogen (N), and lanthanum (La), with a La content of approximately 1.65%, confirming the successful incorporation of lanthanum into the activated carbon following lanthanum nitrate modification. After adsorption, the EDS spectrum in Figure 3b reveals the presence of fluorine (F), which is uniformly distributed across the biochar surface, indicating that fluoride ions have been effectively immobilized on the material. These observations demonstrate that the combination of a porous structure and lanthanum functionalization facilitates efficient fluoride adsorption by the biochar.

Figure 3.

(a) SEM-EDS image of HPAC-La-750 prior to adsorption, (b) SEM-EDS image of HPAC-La-750 after adsorption, (c) N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of the adsorbent, (d) Pore size distribution of the adsorbent.

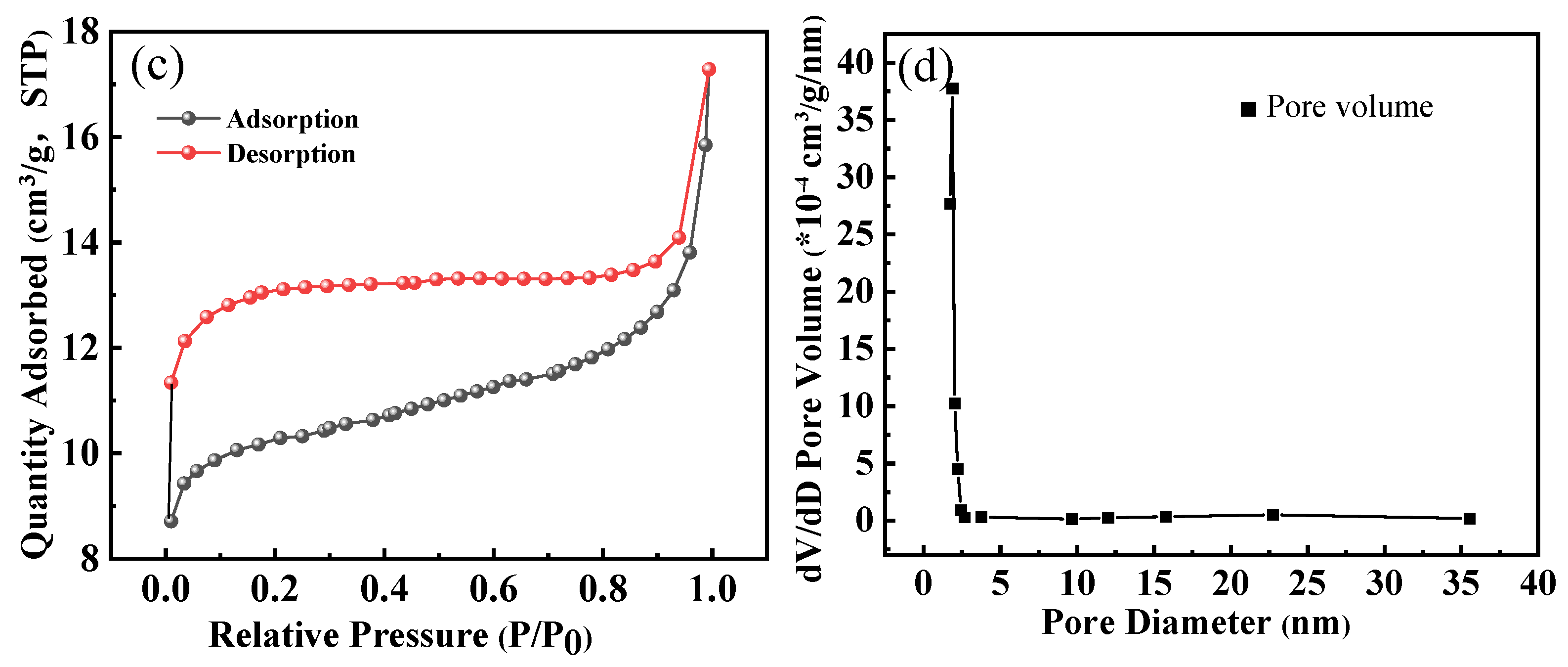

The plotted results in Figure 3c,d indicate that the nitrogen adsorption of HPAC-La-750 is weak at low pressures (P/P0 ≤ 0.9), and nitrogen adsorption rises strongly at high pressures (0.9–1.0), exhibiting a narrow hysteresis loop compared to HPAC-La-750. According to Gibbs isotherm classification, this type of adsorption isotherm represents an example of type IV adsorption for mesoporous materials curve [34]. The surface area and pore volume of HPAC-La-750 were 40.1 m2/g and 0.013 cm3/g, respectively.

This preparation method integrated soybean protein with the lanthanum nitrate precursor prior to pyrolysis, which critically shaped the resulting porous architecture. As evidenced by the nitrogen adsorption isotherm (Type IV with a narrow hysteresis loop, Figure 3c,d), the process successfully generated a mesoporous structure with a specific surface area of 40.1 m2/g. This well-developed pore network (Figure 3a insert) provided the essential channels and active sites for mass transport. Furthermore, the EDS analysis confirmed that lanthanum was uniformly incorporated into this carbon matrix at a content of 1.65%.

3.3. Effect of pH on Fluoride Ion Adsorption

The adsorption experiment was conducted under the following conditions: a solid–liquid ratio of 0.5 g/L, a fluoride ion concentration of 300 mg·L−1, a temperature of 298 K, and an adsorption time of 4 h.

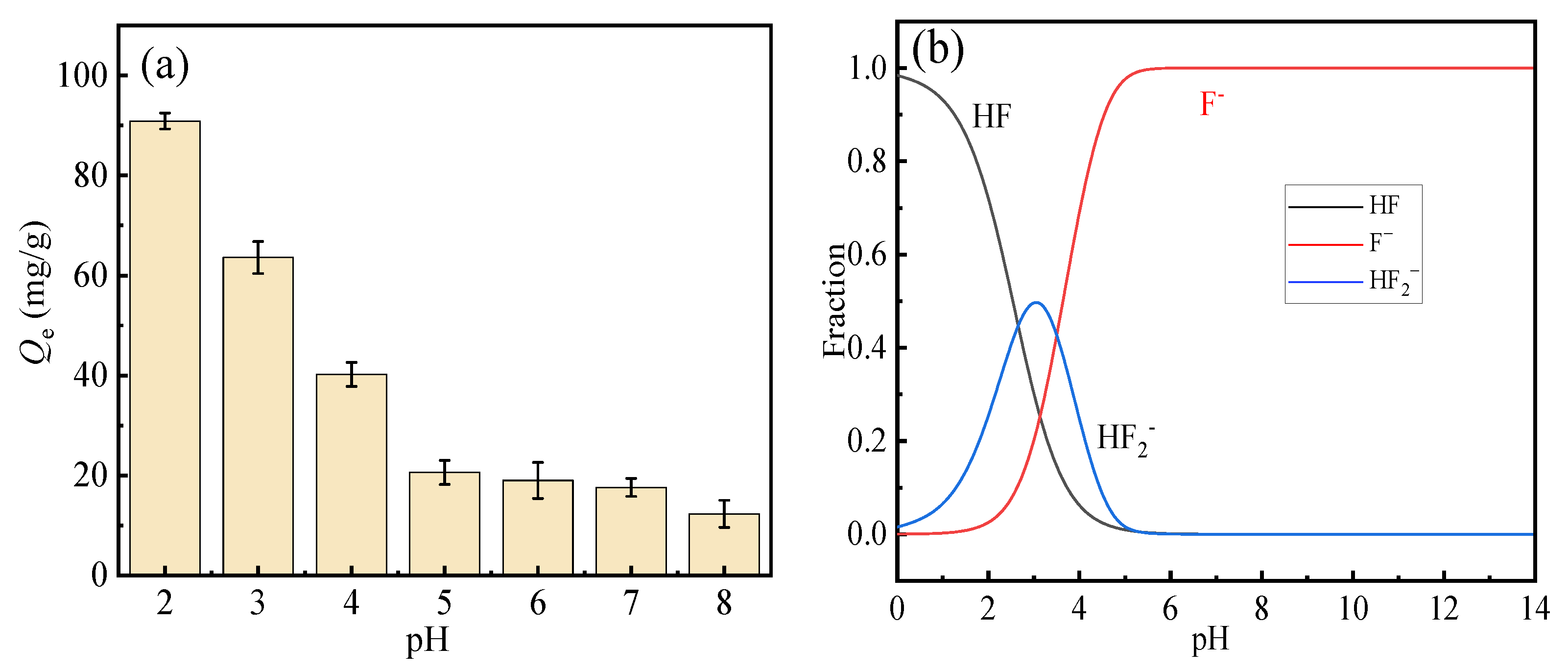

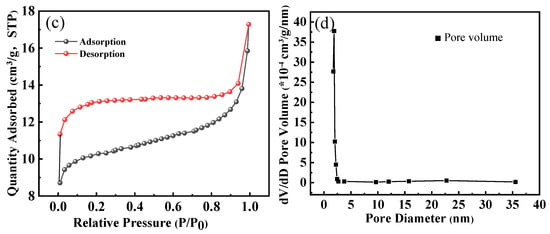

The effect of solution pH on the fluoride adsorption performance of HPAC-La-750 is illustrated in Figure 4a. As depicted, the fluoride adsorption capacity of the biochar exhibited a pronounced dependence on the pH within the range of 2–8, achieving the maximum removal efficiency at pH 2. A progressive decline in adsorption capacity was observed with increasing pH, a trend consistent with the findings in reference [35]. This is most likely due to the weakening of electrostatic attraction and the intensified competition from hydroxide ions under higher pH conditions.

Figure 4.

(a) Effect of pH on fluoride ion adsorption performance, (b) fluorine predominance diagram.

The adsorbed solution was subjected to inductively coupled plasma (ICP, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) analysis, confirming negligible lanthanum leaching (<0.1 mg/L), thereby eliminating potential environmental concerns.

3.4. Adsorption Time and Kinetics

The adsorption experimental conditions were as follows: pH = 2, fluoride ion concentration 300 mg·L−1, solid–liquid ratio 0.5 g/L (HPAC-La-750), temperature 298 K, and adsorption time ranging from 0 to 12 h.

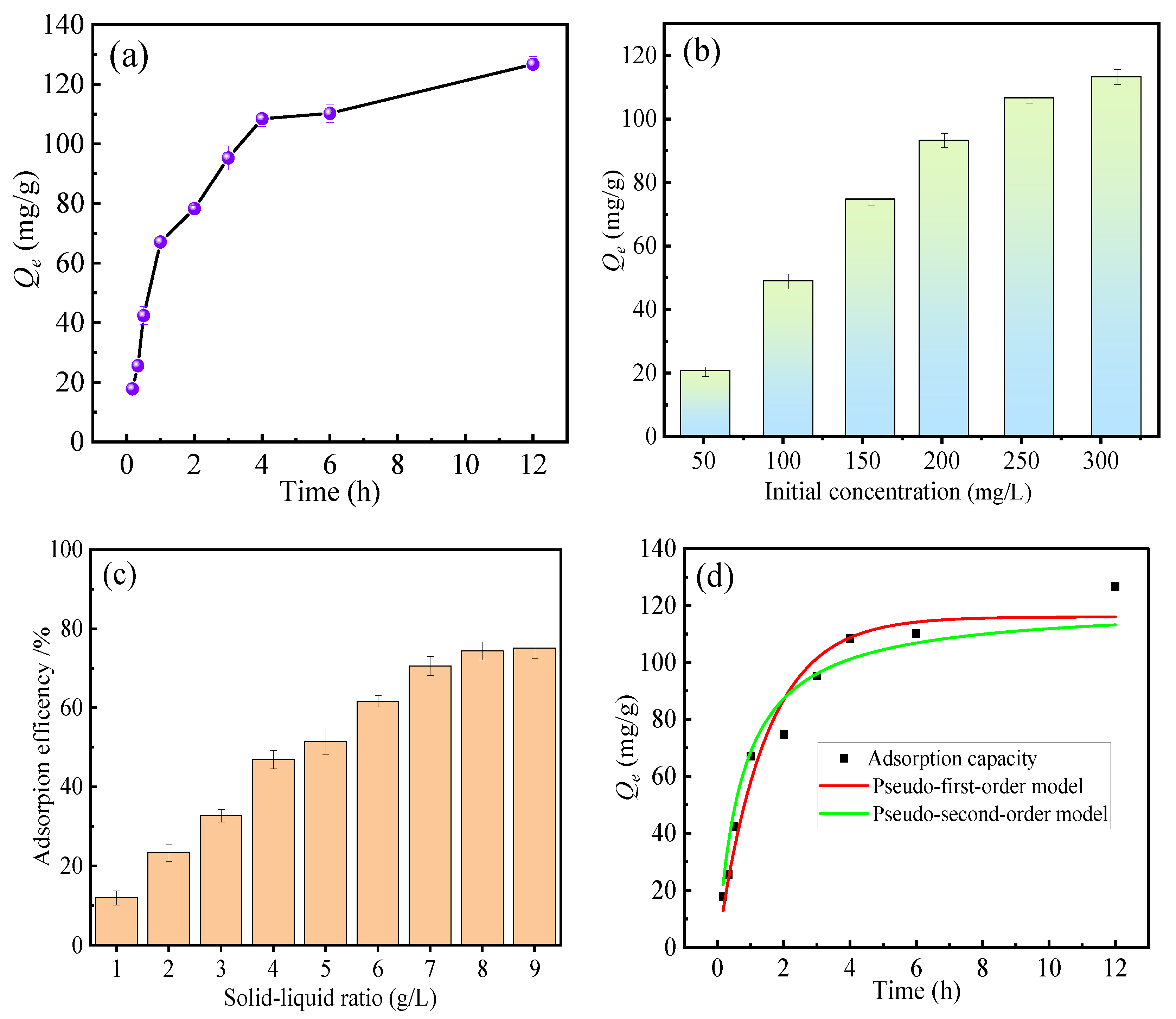

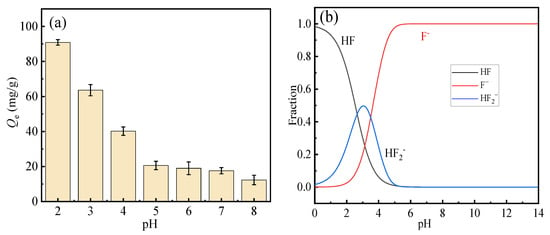

Figure 5a presents the effect of adsorption time on the fluoride uptake of HPAC-La-750. As observed, the adsorption process exhibited two distinct stages. In the initial stage, rapid fluoride removal occurred within the first 4 h, reaching a capacity of 110 mg·g−1, which reflects the high affinity of the adsorbents and fast adsorption kinetics. In the subsequent stage, the adsorption rate gradually declined as the number of available active sites decreased, leading to a slower approach toward equilibrium. The system ultimately reached adsorption equilibrium after approximately 12 h [35].

Figure 5.

(a) Effect of adsorption time on fluoride removal, (b) Effect of initial concentration on fluoride removal, (c) Effect of solid–liquid ratio on fluoride removal, (d) Fitting curves of adsorption kinetic equations.

Figure 5b illustrates the effect of initial fluoride ion concentration on adsorbent performance. Adsorption capacity increases with rising concentration, reflecting that higher solute concentrations provide stronger driving forces. Figure 5c illustrates the effect of solid–liquid ratio on fluoride ion adsorption efficiency. Removal efficiency progressively increases with rising solid–liquid ratio, reaching equilibrium when the ratio exceeds 4 g·L−1. This indicates that highly efficient adsorption can be achieved at a solid–liquid ratio of approximately 4 g·L−1.

To investigate the adsorption kinetics, the pseudo-first-order (PFO) and pseudo-second-order (PSO) models were applied. The corresponding fitting parameters are summarized in Table 1, and the model fitting curves are presented in Figure 5d. As shown in Table 1, the PSO model exhibited a higher correlation coefficient (R2) approaching 1, and the values of Prob > F and χ2 for PSO are higher than those for PFO, indicating that fluoride adsorption conforms to pseudo-second-order kinetics. This result implies that chemisorption is the primary rate-limiting mechanism governing the adsorption process.

Table 1.

Kinetic equation fitting parameters.

3.5. Adsorption Isotherm Models

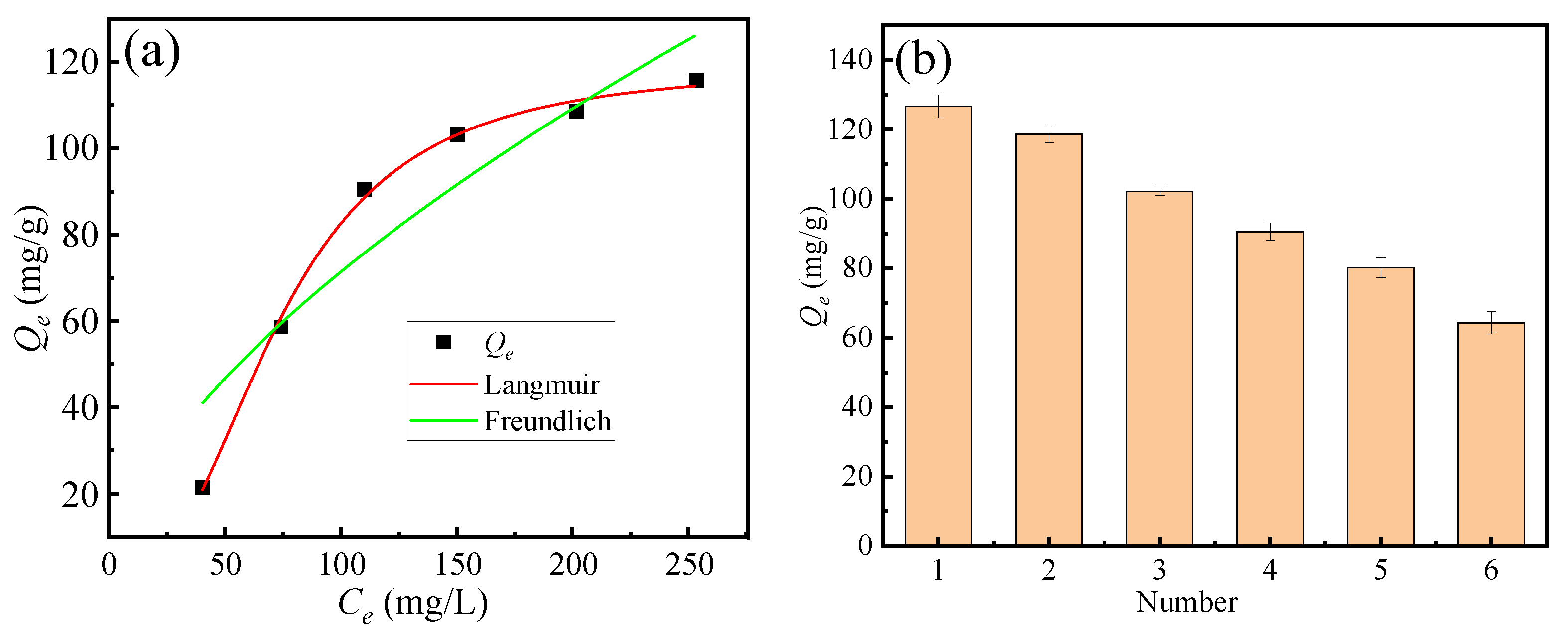

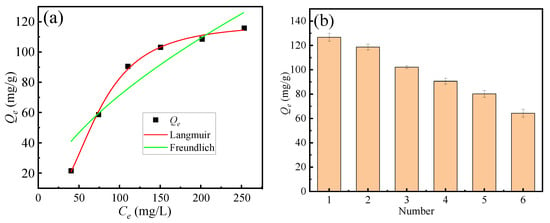

Figure 6a illustrates the effect of fluoride ion concentration on the saturated adsorption capacity of the adsorbent. Experimental conditions were as follows: pH = 2, fluoride ion concentration ranging from 50 to 300 mg·L−1, adsorption temperature of 298 K, and solid–liquid ratio of 0.5 g/L. The Langmuir and the Freundlich adsorption isotherm models are commonly employed to describe adsorption equilibrium behavior. The Langmuir model assumes uniform monolayer adsorption, whereas the Freundlich model characterizes adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces. The solid lines in Figure 6a correspond to the Langmuir and the Freundlich model fitting curves for the adsorbent. Figure 6b shows that adsorption–desorption cycling tests (6 cycles) using alkaline elution, demonstrating good regenerability (>50% capacity retention).

Figure 6.

(a) Fitting curves of adsorption isotherm equations, (b) cycling tests.

Comparison of the correlation coefficients (R2) in Table 2 shows that the Langmuir model achieved a substantially higher R2 than the Freundlich model under identical experimental conditions. This observation suggests that fluoride adsorption on soybean protein biochar predominantly occurs as monolayer adsorption on a relatively homogeneous surface, consistent with the assumptions of the Langmuir model, rather than heterogeneous multilayer adsorption described by the Freundlich model.

Table 2.

Fitting parameters of adsorption isotherm models.

Table 3 presents the comparison of defluorination performance for different carbon-based adsorbents. Data analysis indicates that lanthanum-modified pyrolytic activated carbon HPAC-La-750 demonstrated outstanding performance in terms of maximum saturation adsorption capacity, exhibiting significantly superior adsorption properties compared to the reference materials.

Table 3.

Comparison of defluorination performance for different carbon-based adsorbents.

3.6. Adsorption Mechanism

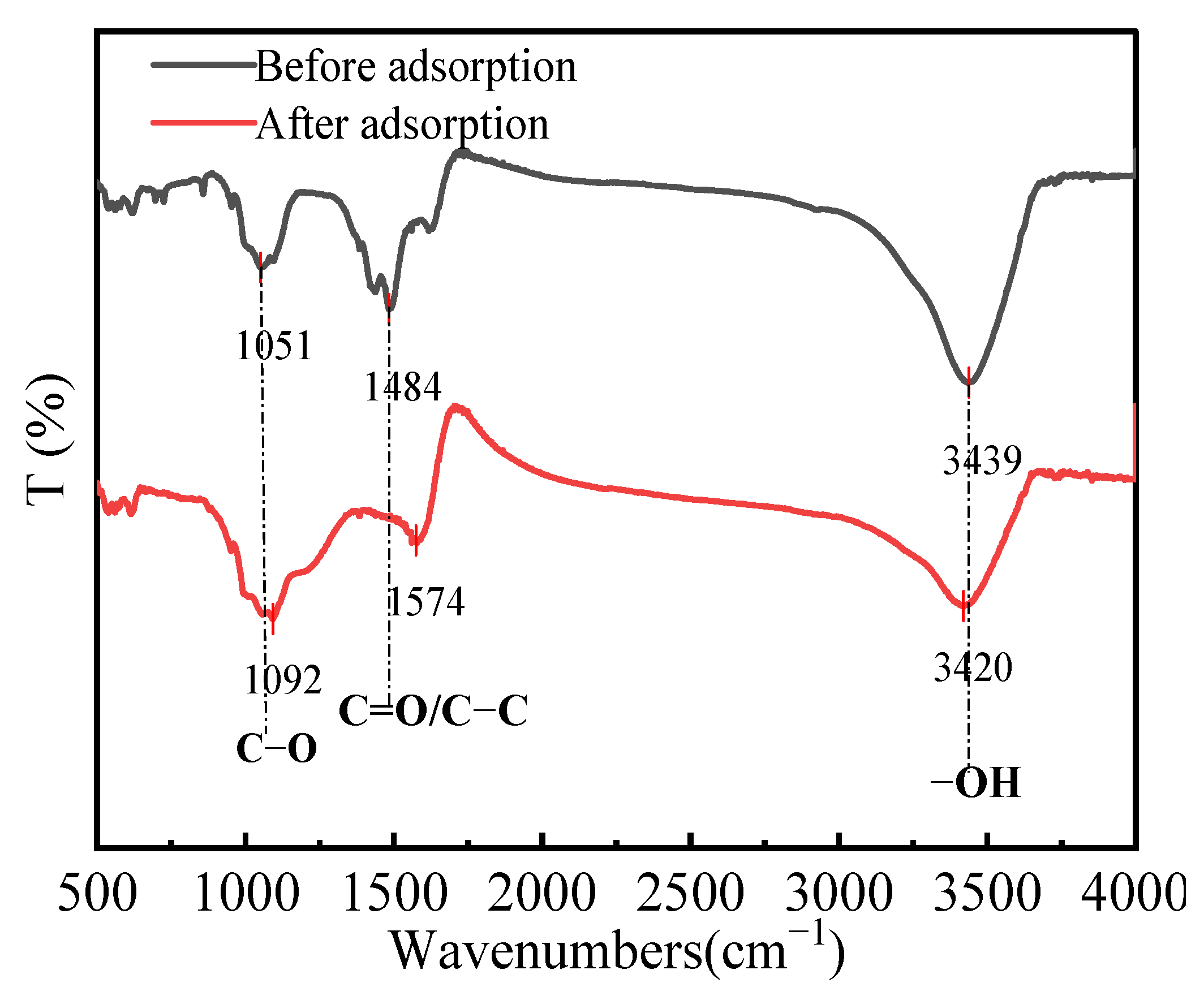

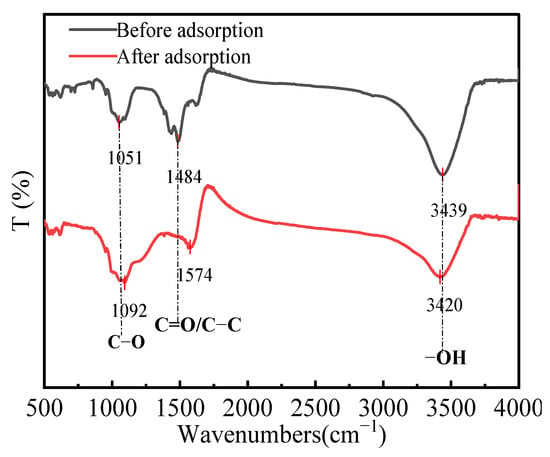

3.6.1. FT-IR Analysis

The FT-IR spectra of HPAC-La-750 before and after fluoride ion adsorption are shown in Figure 7. The comparison reveals marked changes in functional groups, elucidating the interactions with fluoride ions. Notably, shifts in the absorption peaks of hydroxyl and carbonyl groups indicate that polar surface groups participated in adsorption, likely via ion exchange. Specifically, oxygen-containing groups (-COOH and -OH) may undergo an ion-exchange process where La3+ replaces H+, subsequently forming complexes with F−. These results demonstrate that both the surface functional groups and the incorporated lanthanum contribute to the effective fluoride adsorption by HPAC-La-750.

Figure 7.

XPS full spectra of HPAC-La-750 before and after adsorption.

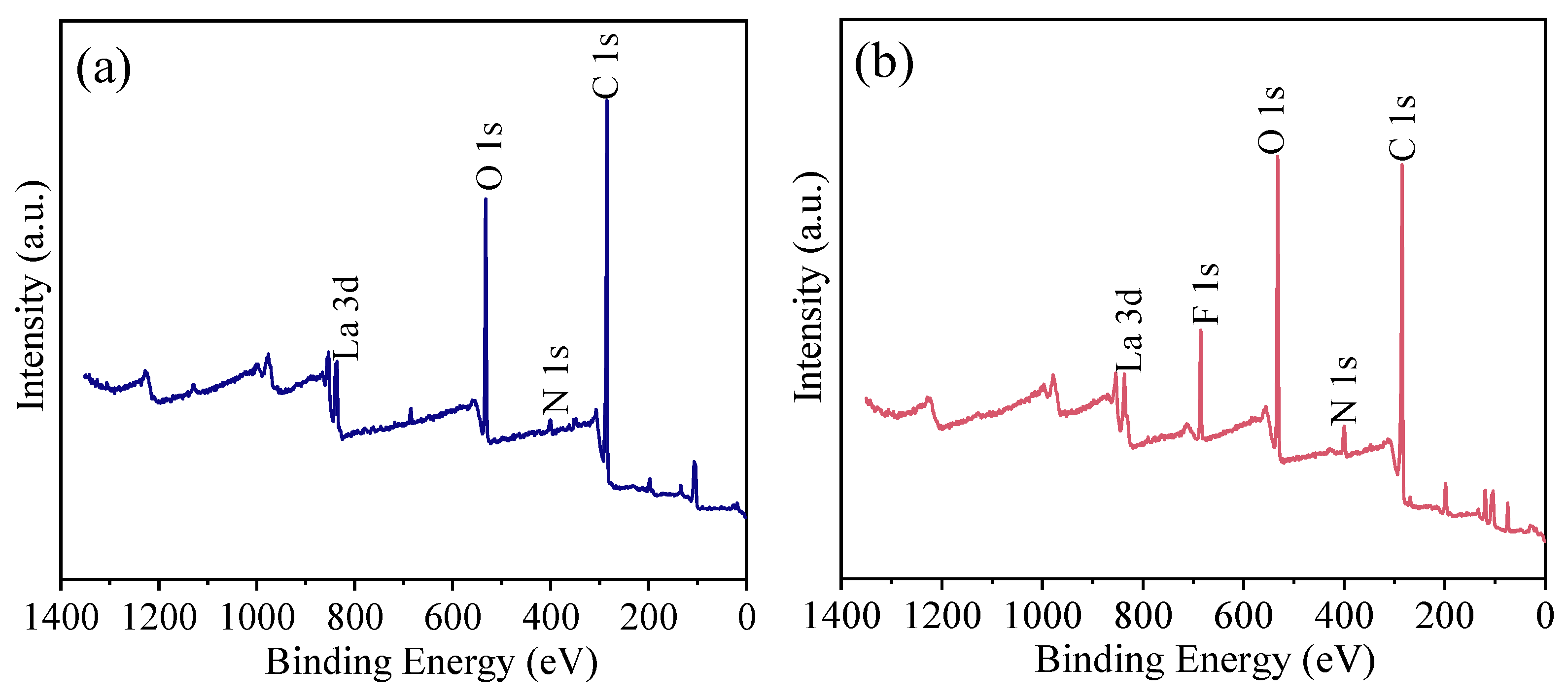

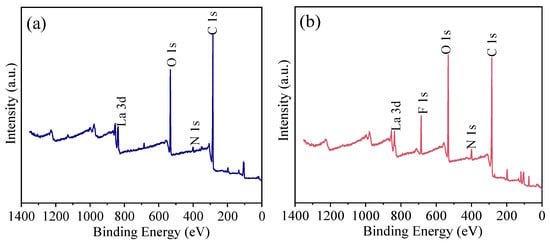

3.6.2. XPS Analysis

The full-spectrum scan in Figure 8 shows that the HPAC-La-750 surface primarily contains carbon (C), oxygen (O), and nitrogen (N), derived from the carbon skeleton, oxygen-containing groups, and nitrogen-containing groups of the soybean protein. After fluoride adsorption, a distinct fluorine (F) peak emerges in the spectrum, confirming the successful uptake of fluoride ions onto the biochar. These results corroborate the elemental analysis and affirm that fluoride was adsorbed onto HPAC-La-750.

Figure 8.

XPS full spectra of HPAC-La-750 (a) before and (b) after adsorption.

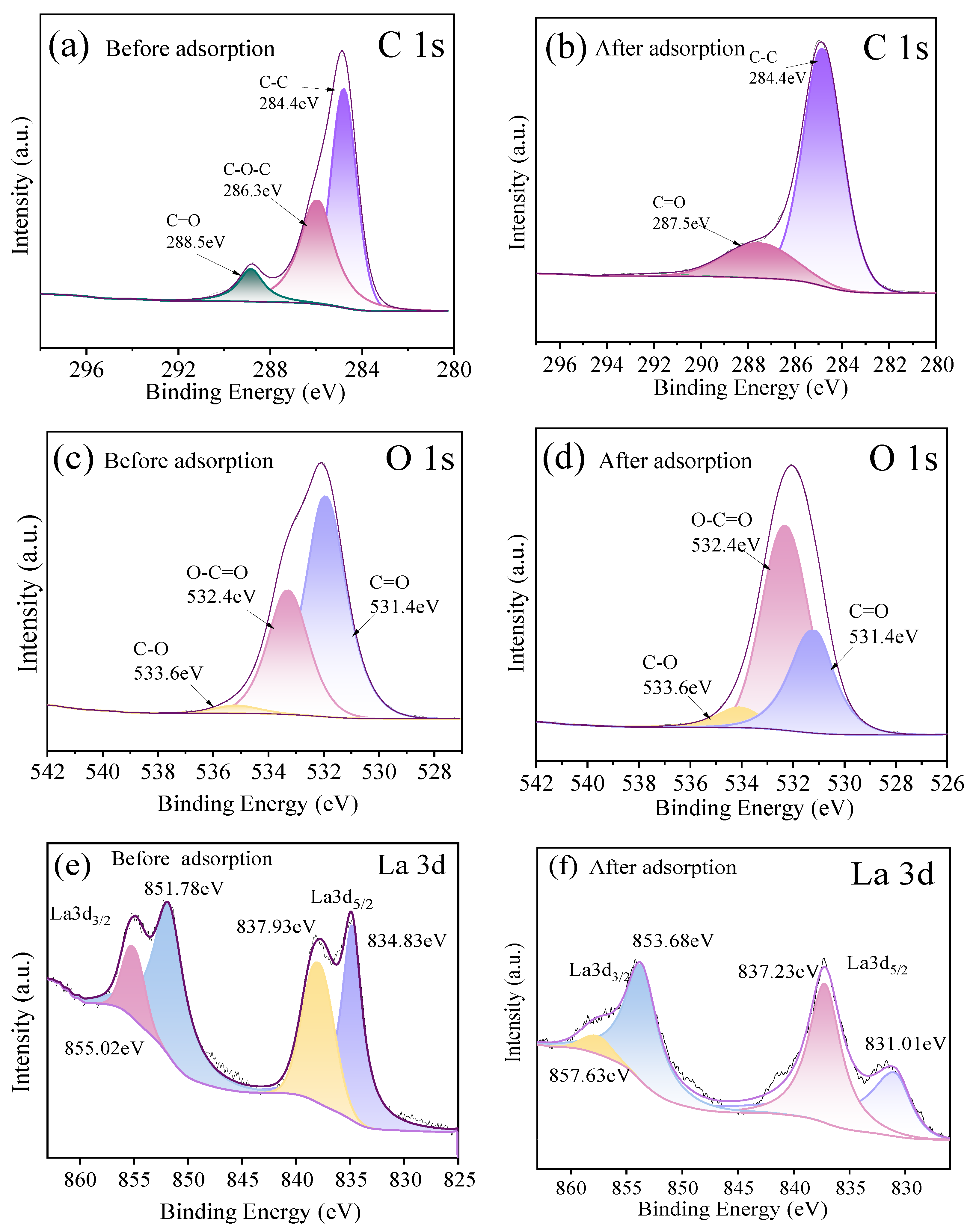

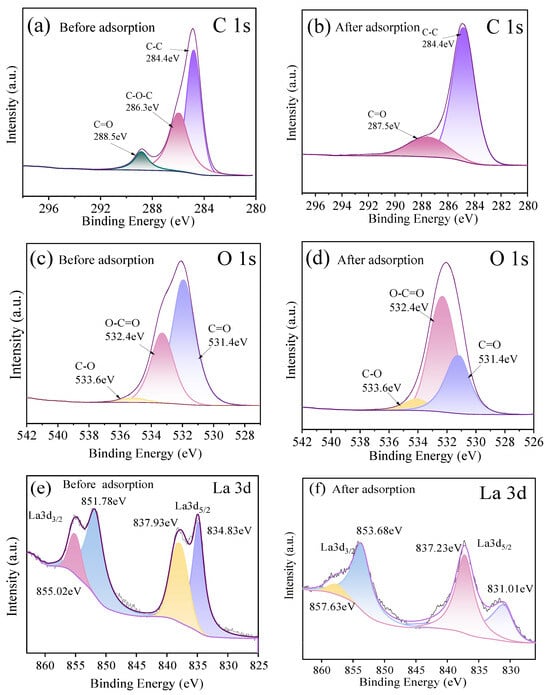

Narrow-line spectra of C 1s and O 1s before and after adsorption of fluoride ions on HPAC-La-750, as shown in Figure 9a, Figure 9b and Figure 9c, and Figure 9d, respectively. The C 1s spectrum of HPAC-La-750 prior to adsorption resolves into three peaks: 284.8 eV (C-C/C=C, representing the carbon skeleton), 286.3 eV (C-O, corresponding to hydroxyl, ether, and related groups), and 288.5 eV (O=C-OH, carboxyl groups). Following fluorine adsorption, significant changes were observed: the C-O peak disappeared, and the binding energy component of the C=O peak shifted by 1 eV. These changes indicate that carbon–oxygen functional groups on the biochar surface underwent chemical interactions with fluoride ions, altering the electron density of certain C-O bonds and providing strong evidence for chemisorption. The O 1s spectrum of the pristine biochar comprises two peaks: 531.4 eV, corresponding to carbonyl (C=O) and carboxyl (O-C=O) groups, and 532.4 eV, corresponding to hydroxyl and ether (C-O) groups. After adsorption, the intensity of the 532.4 eV peak increased markedly, with its area proportion rising from 45% to 58%, indicating that carbonyl and carboxyl groups played a critical role in fluoride binding, likely through ion exchange or complexation, which altered their chemical environment. In the La 3d spectrum (Figure 9e,f), the La 3d5/2 peak shifts towards lower binding energies, while the La 3d3/2 peak shifts towards higher binding energies. Furthermore, the satellite peak intensity diminishes, demonstrating that La3+ forms a stable La-F coordinate bond with F−. Combined with the coordination environment changes observed via FT-IR, this demonstrates that fluoride ions form a more stable La-F coordination bond with La3+ by replacing hydroxyl groups. This ternary synergistic mechanism involving the ‘functional group-La3+-F−’ complex encompasses both proton exchange between carboxyl/hydroxyl groups and the specific coordination of La3+.

Figure 9.

(a,b) C 1s XPS spectra of HPAC-La-750 before and after adsorption; (c,d) O 1s XPS spectra of HPAC-La-750 before and after adsorption; (e,f) La 3d XPS spectra of HPAC-La-750 before and after adsorption.

Overall, these observations confirm that chemisorption dominates the fluoride adsorption process on HPAC-La-750, with oxygen-containing functional groups, such as hydroxyl and carboxyl, being essential for efficient fluoride removal through chemical complexation and ion exchange. Combining FT-IR and XPS analyses, the adsorption mechanism primarily involves the dual action of surface oxygen-containing functional groups synergizing with lanthanum sites.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that lanthanum nitrate modification is a highly effective strategy for developing high-performance fluoride adsorbents. The impregnation of soybean protein with lanthanum nitrate, followed by freeze–drying and carbonization, successfully yielded a modified activated carbon (HPAC-La). The modification dramatically enhanced the adsorption performance, increasing the maximum saturated adsorption capacity from 86.1 mg·g−1 (unmodified HPAC) to 126.7 mg·g−1 (HPAC-La) under optimized conditions (initial [F−] = 300 mg·L−1, pH 2.0). The adsorption process, which followed pseudo-second-order kinetics and the Langmuir isotherm, is identified as a monolayer chemisorption governed by ion exchange via surface hydroxyl groups and specific coordination with La sites.

However, this study has the following significant limitations: (1) The optimal pH 2.0 condition poses considerable challenges in practical applications. The strongly acidic environment not only exacerbates equipment corrosion and increases operational costs but also conflicts with the neutral pH conditions typical of most industrial wastewater streams; (2) The experiments employed simulated fluoride solutions only, failing to investigate the influence of coexisting ions commonly found in real water samples (such as Cl−, SO42−, HCO3−, etc.) on adsorption performance; (3) Long-term stability verification under actual water quality parameters (e.g., complex organic compounds, multi-ionic systems, variable pH conditions) is lacking.

Despite these limitations, HPAC-La demonstrates promising application potential. Subsequent research will focus on optimizing the material’s performance within neutral pH ranges, evaluating its practical efficacy through real wastewater experimental systems, and developing material modification strategies suitable for complex water qualities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.H.; methodology, C.H., Z.J. and Z.H.; validation, C.H.; formal analysis, G.Z. and W.B.; investigation, G.Z.; data curation, W.B. and G.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, G.Z. and Z.H.; writing—review and editing, C.H. and Zhengnan Jiang; supervision, Z.H.; project administration, C.H.; funding acquisition, C.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the China National University Student Innovation & Entrepreneurship Development Program, grant number 202510593031, Guangxi Science and Technology Major Project, grant number AA24263044, the Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi Province, China, grant number 2024GXNSFAA010485, and the Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 52364022.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Zhenhai Huang was employed by the Guangxi Yusheng Germanium Industry High-tech Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DETA | Diethylenetriamine |

| EDTA | Ethylene Diamine Tetraacetic Acid |

References

- Jha, S.K.; Singh, R.K.; Damodaran, T.; Mishra, V.K.; Sharma, D.K.; Rai, D. Fluoride in Groundwater: Toxicological Exposure and Remedies. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part B 2013, 16, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hug, S.J.; Winkel, L.H.E.; Voegelin, A.; Berg, M.; Johnson, A.C. Arsenic and Other Geogenic Contaminants in Groundwater—A Global Challenge. Chimia 2020, 74, 524–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaji, E.; Sarath, K.V.; Santosh, M.; Krishnaprasad, P.K.; Arya, B.K.; Babu, M.S. Fluoride contamination in groundwater: A global review of the status, processes, challenges, and remedial measures. Di Xue Qian Yuan 2024, 15, 101734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Wu, B.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, S. Coagulation removal of fluoride by zirconium tetrachloride: Performance evaluation and mechanism analysis. Chemosphere 2019, 218, 860–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guo, M.; Zheng, S.; Yang, X.; Zheng, X. Self-inhibition mechanism of competitive ions for low-cost, highly selective ion removal in a standard ion-exchange resin-packed column process. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 359, 130603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes-Pereira, J.; Lima, R.; Choudhary, G.; Sharma, P.R.; Ferdov, S.; Botelho, G.; Sharma, R.K.; Lanceros-Méndez, S. Highly efficient removal of fluoride from aqueous media through polymer composite membranes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 205, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collivignarelli, M.C.; Abbà, A.; Carnevale Miino, M.; Torretta, V.; Rada, E.C.; Caccamo, F.M.; Sorlini, S. Adsorption of Fluorides in Drinking Water by Palm Residues. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Fang, L.; Shi, X.; Li, T.; Sui, Z.; Zhong, J.; Li, K. Efficient defluoridation of high-fluoride water using rare earth-based adsorbents: Adsorption performance, mechanism, and kinetics. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 42709–42715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgin, J.; Franco, D.S.P.; Manzar, M.S.; Meili, L.; El Messaoudi, N. A critical and comprehensive review of the current status of 17β-estradiol hormone remediation through adsorption technology. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 24679–24712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Messaoudi, N.; Franco, D.S.P.; Gubernat, S.; Georgin, J.; Şenol, Z.M.; Ciğeroğlu, Z.; Allouss, D.; El Hajam, M. Advances and future perspectives of water defluoridation by adsorption technology: A review. Environ. Res. 2024, 252, 118857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehmani, Y.; Ba Mohammed, B.; Oukhrib, R.; Dehbi, A.; Lamhasni, T.; Brahmi, Y.; El-Kordy, A.; Franco, D.S.P.; Georgin, J.; Lima, E.C.; et al. Adsorption of various inorganic and organic pollutants by natural and synthetic zeolites: A critical review. Arab. J. Chem. 2024, 17, 105474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şenol, Z.M.; El Messaoudi, N.; Ciğeroglu, Z.; Miyah, Y.; Arslanoğlu, H.; Bağlam, N.; Kazan-Kaya, E.S.; Kaur, P.; Georgin, J. Removal of food dyes using biological materials via adsorption: A review. Food Chem. 2024, 450, 139398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Malloum, A.; Igwegbe, C.A.; Ighalo, J.O.; Ahmadi, S.; Dehghani, M.H.; Othmani, A.; Gökkuş, Ö.; Mubarak, N.M. New generation adsorbents for the removal of fluoride from water and wastewater: A review. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 346, 118257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; Lin, J.; Tao, W.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; He, F. Enhanced Fluoride Removal from Water by Nanoporous Biochar-Supported Magnesium Oxide. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res 2019, 58, 9988–9996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Qi, Y.; Chen, Z.; Song, N.; Li, X.; Ren, D.; Zhang, S. Evaluation of fluoride and cadmium adsorption modification of corn stalk by aluminum trichloride. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 543, 148727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aworn, A.; Thiravetyan, P.; Nakbanpote, W. Preparation and characteristics of agricultural waste activated carbon by physical activation having micro- and mesopores. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2008, 82, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.K.; Abbassi, R.; Gupta, A.; Dadashzadeh, M. Removal of fluoride from aqueous solution and groundwater by wheat straw, sawdust and activated bagasse carbon of sugarcane. Ecol. Eng. 2013, 52, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, A.; Nayak, A.K.; Singh, J. Synthesis of FeCl3-activated carbon derived from waste Citrus limetta peels for removal of fluoride: An eco-friendly approach for the treatment of groundwater and bio-waste collectively. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 10, 100339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhta, S.; Sadaoui, Z.; Lassi, U.; Romar, H.; Kupila, R.; Vieillard, J. Performances of metals modified activated carbons for fluoride removal from aqueous solutions. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2020, 754, 137705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Montoya, V.; Ramírez-Montoya, L.A.; Bonilla-Petriciolet, A.; Montes-Morán, M.A. Optimizing the removal of fluoride from water using new carbons obtained by modification of nut shell with a calcium solution from egg shell. Biochem. Eng. J. 2012, 62, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyaseelan, A.; Viswanathan, N.; Naushad, M.; Albadarin, A.B. Eco-friendly design of functionalized graphene oxide incorporated alginate beads for selective fluoride retention. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2022, 121, 108747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanrar, S.; Debnath, S.; De, P.; Parashar, K.; Pillay, K.; Sasikumar, P.; Ghosh, U.C. Preparation, characterization and evaluation of fluoride adsorption efficiency from water of iron-aluminium oxide-graphene oxide composite material. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 306, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Z.; Tian, Y.; Ruan, J.; Cui, G.; Iqbal, K.; Iqbal, A.; Ye, H.; Yang, Z.; Yan, S. Synthesis of hydroxyapatite/multi-walled carbon nanotubes for the removal of fluoride ions from solution. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 412, 578–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affonso, L.N.; Marques, J.L.; Lima, V.V.C.; Gonçalves, J.O.; Barbosa, S.C.; Primel, E.G.; Burgo, T.A.L.; Dotto, G.L.; Pinto, L.A.A.; Cadaval, T.R.S. Removal of fluoride from fertilizer industry effluent using carbon nanotubes stabilized in chitosan sponge. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 388, 122042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatnagar, A.; Kumar, E.; Sillanpää, M. Fluoride removal from water by adsorption—A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 171, 811–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Zhang, J.; Hu, Y.; Han, R. Preparation of Novel Magnetic Microspheres with the La and Ce-Bimetal Oxide Shell for Excellent Adsorption of Fluoride and Phosphate from Solution. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2019, 64, 3641–3651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Fan, J.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, W. Enhanced fluoride removal by nanosized lanthanum hydroxide loaded on magnetic resin. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 725, 137715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asare, J.A.; Alhassan, S.I.; Anaman, R.; Amanze, C.; Gang, H.; Wei, D.; Wang, H.; Huang, L. Synergistic influence of lanthanum and cellulose on fly ash synthesized zeolite for enhanced fluoride removal from wastewater: Performance and mechanism. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 379, 134810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratthika, S.A.; Ramkumar, K.; Elanchezhiyan, S.S.; Kumar, R.; Meenakshi, S. Synthesis and characterization of lanthanum-assisted aluminium metal-organic frameworks for the removal of fluoride ions from an aqueous environment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 118181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.-C.; Ning, S.; Xu, J.-N.; Guo, F.; Li, Z.; Wei, Y.-Z.; Dodbiba, G.; Fujita, T. Study on the adsorption behavior of tin from waste liquid crystal display using a novel macroporous silica-based adsorbent in one-step separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 292, 121006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.-S. Review of second-order models for adsorption systems. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 136, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Ning, S.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Chen, L.; Fujita, T.; Wei, Y. Preparation of a mesoporous ion-exchange resin for efficient separation of palladium from simulated electroplating wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 106966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yin, X.; Zheng, N.; Lin, Z.; Fujita, T.; Ning, S.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X. Flexible self-supporting Na3MnTi(PO4)3@C fibers for uranium extraction from seawater by electro sorption. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 461, 132664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-Q.; Bon, V.; Darwish, S.; Wang, S.-M.; Yang, Q.-Y.; Xu, Z.; Kaskel, S.; Zaworotko, M.J. Insight into the Gas-Induced Phase Transformations in a 2D Switching Coordination Network via Coincident Gas Sorption and In Situ PXRD. ACS Mater. Lett. 2024, 6, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechnou, I.; Oukkass, S.; El kartouti, A.; Hlaibi, M.; Saleh, N.i.; Alanazi, A.K. High adsorption capacity of diclofenac and paracetamol using OMWW based W-carboxylate doped activated carbon. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 378, 134719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Kamila, B.; Paul, S.; Hazra, B.; Chowdhury, S.; Halder, G. Optimizing fluoride uptake influencing parameters of paper industry waste derived activated carbon. Microchem. J. 2021, 160, 105643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.K.; Hota, G. Surface functionalization of GO with MgO/MgFe2O4 binary oxides: A novel magnetic nanoadsorbent for removal of fluoride ions. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 2918–2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.