Abstract

Ferrate as an environmentally friendly oxidant has been widely used in the environmental remediation and versatile functionalization of carbon-based materials. In this study, we investigated its ability to induce surface wettability of polymers and its emerging applications in separating mixed plastics through flotation for recycling. It was found that ferrate (VI) formed oxygen-containing groups on the surface of polycarbonates (PCs) by selectively oxidizing the sp3-hybridized carbon atoms into hydroxyl and carboxyl moieties, in addition to introducing nanoscale iron oxides. This facilitated the selective hydrophilization of PC with a water contact angle of 60.7° but did not clearly affect the surface wettability of polyvinyl chloride (PVC). This difference in surface wettability highlighted the distinct floatability properties of PC and PVC, which can be utilized to separate mixtures of these plastics with the aid of flotation. A central composite design (CCD) utilizing response surface methodology (RSM) was applied to model ferrate oxidation and to optimize flotation. Under the optimized conditions, mixtures of PC and PVC were efficiently separated with recovery and purity values of more than 99.8 ± 0.3%. Our findings provide a rational understanding of polymer wettability tailoring and expand its emerging applications in waste plastic recycling to address environmental problems.

1. Introduction

As one of the strongest oxidizers among the iron species, ferrate (VI) has attracted the interest of the scientific community because of its abundance in the earth, low toxicity, strong oxidizing capability, and easy removal after use in contrast to other oxidants [1,2]. Ferrate (VI), with its tetrahedral coordination geometry and d2 electron configuration, has a high oxidizing ability with a high redox potential (E° = 2.2 V vs. HNE) in acidic media [3]. Theoretically, 1 mol of ferrate (VI) could capture 3 mol of electrons during its sequential reduction process, Fe (VI) → Fe (V) → Fe (IV) → Fe (III), generating terminal ferric hydroxides in situ [4]. Among these iron intermediates, Fe (V) and Fe (IV) have greater oxidation efficiency [5]. In addition, the nanoscale ferric hydroxides have a high dispersity and a large amount of hydroxyl moieties, enabling it to serve as an excellent coagulant based on multiple interactions such as chemical bonds and H-bonding. The aforementioned characteristics endow ferrate (VI) with wide utilization in environmental remediation, such as oxidation degradation of electro-rich organics, fabrication of magnetic porous biochar, disinfection of pathogens, and eliminating soluble humic substances serving as precursors of halogenated disinfection byproducts (DBPs) [6,7,8]. In addition, ferrate (VI) has been applied in chemical synthesis, super metal batteries, and generating oxygen from the splitting of water [1,9].

In recent years, based on the single-electron (forming radical intermediates) and two-electron transfer reactions initiated by high-valent iron species, interest has increased regarding the use of ferrate (VI) to functionalize various carbon-based materials for environmental decontamination. In previous studies, ferrate (VI) was first utilized to exfoliate and oxidize graphite in concentrated sulfuric acid, rapidly producing single-layer graphite oxide (GO) [10]; graphite oxidization was also explored in a study conducted by Zdeněk Sofer et al., with autodecomposition products and atomic oxygen [O] used synergistically. In the latter study, after ferrate (VI) oxidation, low-oxidation degree graphite was obtained, though the ferrate (VI) showed extreme instability [11]. Likewise, other studies have investigated the application of ferrate (VI) in the oxidative functionalization of fullerene (C60), graphite, and carbon nanotubes, with these carbon-based materials showing lower oxidization in the aqueous phase than in the solid phase [12,13,14]. Based on these previous studies, ferrate (VI) shows promise for the surface functionalization of carbon-based materials by introducing functional groups.

For functionalization of polymers, some methods such as coating, plasma treatment, wet modification, UV irradiation, and gas discharge have been intensively studied in biomedical applications towards tailoring interactions with surrounding biological environment [15,16,17]. Basically, the surface functionalization of polymers is based on modifications of surface composition and topography [18]. More recently, surface functionalization of polymers has attracted increasing interests as an emerging application in the recycling of waste plastics, namely flotation separation of plastic mixtures [19]. Due to the extensive production and consumption of plastic products, a large amount of plastic waste has been generated, resulting in severe environmental pollution. Mechanical recycling, as one of the most effective methods to eliminate the problem of waste plastics, possesses environmentally and economically beneficial perspectives [20,21]. However, in a heterogeneous waste stream, different types of plastics are generally mixed together, severely restricting waste plastic recycling due to physicochemical incompatibility [22,23], and efficient separation techniques are therefore required. Of the various proposed separation methods, flotation is particularly promising due to its simplicity and distinct advantages in separating different types of plastics with similar densities.

Intrinsically, flotation separation is based on the varying surface wettability between different types of polymers, as surfaces with high and low wettability exhibit differences in floatability due to the selective attachment of air bubbles. Most polymers are hydrophobic, meaning that they must be functionalized prior to flotation separation [24]. Some functionalization methods, such as wave/heat treatment [25], nano-metal calcium composite coating [26], permanganate oxidation [27], and zinc oxide coating/microwave, have been used to selectively modify the surface of polymers for flotation separation [28]. For example, UV and microwave irradiations have been utilized to modify the surface wettiability of plastics and facilitated the flotation separation of plastic mixtures [29,30]. However, these methods involve complicated treatment procedures, hazardous reagents, and poor practicality. In this regard, simple and green functionalization methods for polymers are necessary. Given that the separation of widely used polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and polycarbonate (PC) is still a major challenge in the recycling process, we therefore attempted to utilize ferrate (VI) modification to enhance the flotation separation of PVC and PC during recycling.

Initially, we studied the effects of ferrate (VI) oxidation on the surface characteristics of PC and PVC, including wettability, zeta potentials, topographies, and functional groups. Afterward, insights concerning ferrate (VI)-induced functionalization mechanisms of polymers were proposed. Furthermore, the application of ferrate (VI)-induced tailoring wettability of polymers in flotation separation of plastic mixtures was studied and optimized with central composite design (CCD) of response surface methodology (RSM). Finally, models were created to determine the effect of ferrate (VI) oxidation on PC and PVC floatability and optimize experimental conditions, successfully separating a mixture of PC and PVC.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Wettability Tailoring

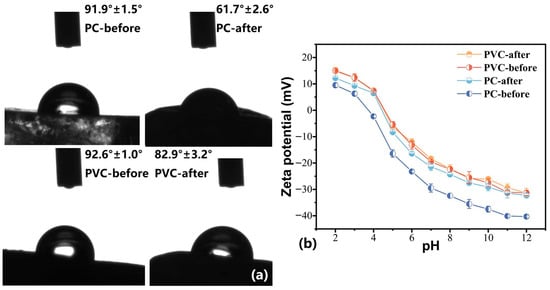

The surface wettability was measured by WCAs on the surfaces of plastics before and after ferrate (VI) oxidation (Figure 1a). After oxidation, the WCAs of all surfaces decreased by varying degrees, meaning that the intrinsic surface hydrophobicity of the plastics was successfully transformed into hydrophilicity through ferrate (VI) oxidation-induced wettability tailoring. A greater effect was seen in PC samples, with a larger decrease in WCA observed from 91.9° to 61.7°. Furthermore, the surface charge of PC and PVC samples was measured with zeta potentials (Figure 1b). The zeta potentials of both PC and PVC decreased rapidly with the increase in pH. The zeta potential of PC showed an obvious decrease after wettability tailoring, while PVC did not show obvious changes. Meanwhile, while measuring zeta potential, we observed that the powder of PC showed a better aqueous dispersibility, in contrast to its counterparts before tailoring. Functional groups and morphological features have been proved to play a role in modulating the surface wettability of materials [31,32]. Therefore, SEM images were recorded to visualize the surface morphology of the plastics.

Figure 1.

CAWs (a) and zeta potential (b) of the plastics.

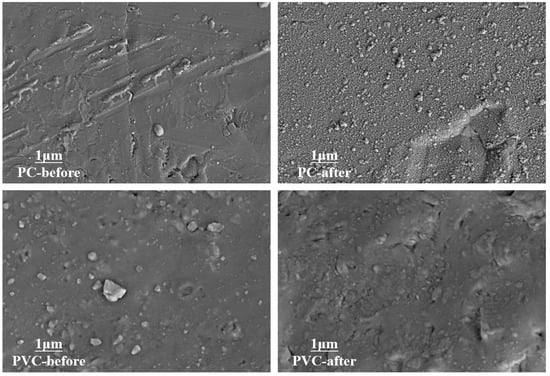

SEM images of plastics exhibit a characteristic planar pattern, which proves that their surface topography is not clearly affected by oxidation (Figure 2). In particular, a few heterogeneous protuberances are observed on the surface of plastic, which are ascribed to the smashing process for sample preparation. Accordingly, we could speculate that ferrate (VI) oxidation induces the surface functionalization of plastics by mainly modifying surface chemistry.

Figure 2.

SEM images of plastics.

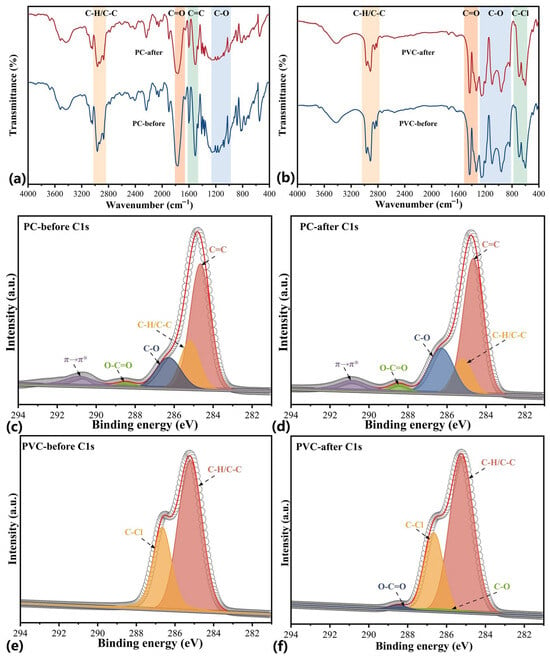

The chemical groups of plastics were ascertained with FT-IR spectra (Figure 3a,b). For PC, the intensities of the O=C-O absorption band at 1770 cm−1, and the C-O absorption bands at 1150 cm−1 and 1230 cm−1 seem to increase after wettability tailoring, while no obvious changes were found in the FT-IR spectra of PVC [33,34], probably because the oxidation mainly occurred on the outermost surface and the C–Cl backbone of PVC is chemically inert to ferrate (VI) oxidation [35]. Furthermore, we performed XPS analysis to ascertain the changes in surface compositions (Figure S1), since XPS can measure the chemical compositions on the outermost layers of the surface of materials (about 5.0–10.0 nm) [9]. Based on the atomic ratios obtained, the O/C ratio of PC increased by 8.98%, and that of PVC increased by 1.11% with a simultaneous decrease in Cl/C ratio by 0.96%. The trace Fe element on the surface of PC after tailoring was also detected at a surface proportion of 0.44%. The high-resolution Fe 2p spectrum is shown in Figure S2. Interestingly, the Fe spectrum with two deconvoluted major peaks at 710.8 eV (Fe 2p3/2) and at 724.8 eV (Fe 2p1/2) revealed the formation of residual ferric oxides. These ferric oxides have also been considered as moieties with hydrophilic characteristics [36].

Figure 3.

FT-IR spectra of PC (a) and PVC (b). The fitting of C 1s peak of PC plastics before (c) and after (d) oxidation. The fitting of C 1s peak of PVC plastics before (e) and after (f) oxidation.

The peak deconvolution of the core-region C 1s spectra was performed (Figure 3c–f). The fitting results of C 1s peaks are summarized in Table 1. Regarding PC after wettability tailoring, the C 1s peaks corresponding to the C-O peak at 286.3 eV and the C=O-O peak at 288.5 eV were found to increase with increased contents by 6.69% and 0.95%, respectively, in good agreement with FT-IR analysis. This was also accompanied by an apparent decrease of 7.46% for sp3-hybridized carbon (sp3-C, C-C/C-H) at 285.2 eV [32]. In terms of PVC after wettability tailoring, the C-O and C=O-O peaks newly appeared with contents of 2.27% and 1.31%; meanwhile, the contents of the sp3-C and the C-Cl peaks decreased by 1.35% and 2.23%, respectively. Note that prior to wettability tailoring, the contents of original C=O-O and C-Cl peaks on the surfaces of PC and PVC are not consistent with their macromolecular structure, respectively, which can be referred to in terms of hydrophobic regeneration through the inverse migration of polar groups and components with low-surface energy [37]. In conclusion, the above results demonstrated that ferrate (VI) oxidation introduces oxygen groups, including carboxyl and hydroxyl moieties, on the surface of plastic, and these groups are responsible for the increased surface wettability [38].

Table 1.

The types and content (%) of C1s fitting peaks on the surface of plastics.

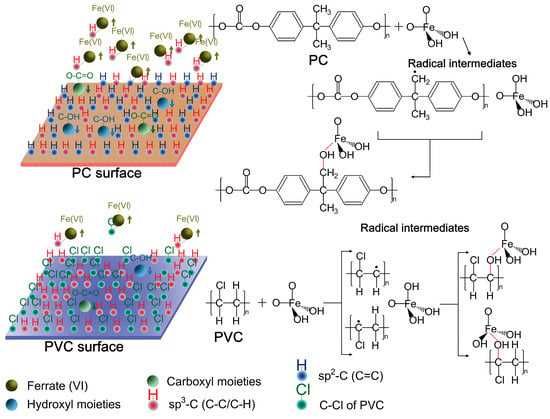

As XPS revealed, the amount of carboxyl and hydroxyl moieties introduced was approximately equivalent to the amount of decreased sp3-C peak for PC, and as to PVC, this value corresponded with the amount of decreased sp3-C and C-Cl peaks. In this regard, it could be speculated that sp3-C moieties with high reactivity in the molecular structures of plastics can be preferentially oxidized by ferrate (VI). This is highly consistent with previous studies that report how ferrate (VI) preferentially hydroxylated the sp3-C of fullerene (C60), graphite, and carbon nanotubes rather than the sp2-C [12]. Regarding PVC, ferrate (VI) oxidation was also effective within the C-Cl groups and induced dechlorination reactions. Accordingly, the major mechanism of wettability tailoring of polymers was to selective surface oxidation. The possible pathways of major reactions are presented in Figure 4. Single-electron transfer reactions may occur on the sp3-C of plastics and induce the formation of radical intermediates, which can be hydroxylated by ferrate (VI) [2]. Then, these hydroxyl moieties can be further oxidized into carboxyl moieties. In addition, atomic oxygen [O] generated from the autodecomposition of ferrate (VI) can also oxidize the plastic surface [10]. The surface’s changed wettability and zeta potentials were attributed to these introduced carboxyl and hydroxyl moieties, along with the changed morphology.

Figure 4.

Schematic mechanism of ferrate (VI) oxidation of plastics.

Most functionalized carbon-based materials such as carbon nanotubes and polymers have been applied in material science [39,40] and biomedical applications [31]. In this study, we found that ferrate (VI) showed functionalization potentials for PC and PVC, resulting in clearly different surface wettability. This difference inspired us to try to apply ferrate (VI)-induced wettability tailoring in the flotation separation of mixtures of PC and PVC towards material recycling. Thus, a hypothesis can be made that after wettability tailoring, hydrophilic PC and hydrophobic PVC samples would possess different floatability, resulting in the effective separation of their mixtures. In order to achieve the efficient separation of PC and PVC, we intensively studied the conditions [ferrate (VI) concentration, contact time, temperature, and stirring rate], generated the prediction models for describing separation performance, and optimized conditions.

2.2. Application in Separation of Plastics

2.2.1. Determination of Critical Factors

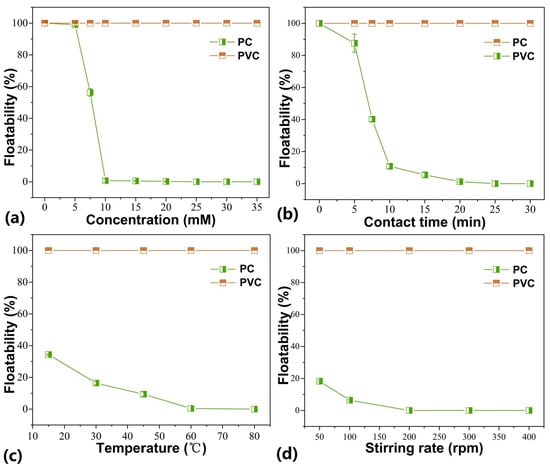

PBD experiments, as a widely used approach for screening critical factors, are suitable in determining the critical factors from 2 to 47 factors, and this specialized design with two-level factors assumes the absence of interactions [41]. The design matrix and experimental results are shown in Table 2. A simple linear equation was used to fit the relation between the response and variables, and the results of the ANOVA analysis are shown in Table S1. From Table S1, D (stirring rate) had the largest p-value among these variables, which indicated that stirring rate had the lowest significance on the response. Therefore, concentration, contact time, and temperature as critical factors were selected to further optimize for achieving the efficient flotation separation of plastic mixtures. On the other hand, preliminary SFEs were also conducted to determine the range of factors in optimization design (Figure 5). As shown in Figure 5, the PC and PVC samples exhibited differing floatability after wettability tailoring, which validated the above hypothesis and proved the feasibility of utilizing ferrate (VI) functionalization to separate polymers via flotation. After wettability tailoring, the floatability of PC showed a remarkable decline as the tested factors increased, while PVC displayed negligible changes. Accordingly, we can conclude that (1) ferrate (VI)-induced functionalization selectively resulted in the decreased floatability of PC, and (2) the ranges of factors for further CCD optimization were within 10.0–30.0 mM for ferrate (VI) concentration, 10.0–25.0 min for contact time, and 45.0–80.0 °C for temperature.

Table 2.

The design matrix and results of PBD experiments.

Figure 5.

The results of SFEs for determining the range of factors in optimization: (a) concentration, (b) contact time, (c) temperature, and (d) stirring rate.

2.2.2. Analysis of Regression and Modeling

The CCD optimization design matrix and factual Δ-floatability are summarized in Table 3. We performed multiple regression analysis, which suggested the use of a modified quadratic equation to fit the empirical relationship between Δ-floatability and the factors tested. The final equations, in accordance with the coded and actual factors, are shown as Equations (1) and (2) below, respectively.

Table 3.

CCD matrix and the factual values of Δ-floatability.

ANOVA was utilized to evaluate the adequacy of this model (Table 4). The F-value 27.80 revealed that the model was statistically significant, which was further confirmed with the model p-Value (<0.0001). For the model terms, significant terms included linear terms (A, B, and C) and quadratic terms (A2, B2, and C2), while interaction terms (AB and AC) were insignificant. The Lack of Fit F-value was significant, indicating that there was only 0.01% chance it could occur due to noise. The determination coefficient (R-Squared) and adjusted determination coefficient (Adj R-Squared) were 0.9529 and 0.9186, respectively, indicating that this model showed good fit to the data [42]. As a measure of the signal-to-noise ratio, a greater Adeq Precision than 4 is desired, and this model with an Adeq Precision of 15.857 indicated an adequate signal. In addition, residuals, namely the difference between the factual and predicted values, were also a general measure for evaluating the adequacy of a prediction model. Standard probability plots of the model are illustrated in Figure S3. From Figure S3, the residuals were randomly scattered around the diagonal, which revealed reasonably well-behaved residuals. Overall, this statistically significant model can be used in depicting ferrate (VI)-induced wettability tailoring of polymers and predicting Δ-floatability in subsequent flotation separation.

Table 4.

ANOVA of the generated model.

2.2.3. Interactions Among the Factors

The interactive effect of single factors on Δ-floatability is shown by the three-dimensional plots (Figure S4). From Figure S4a, at a constant temperature of 62.5 °C, Δ-floatability increased remarkably and slowly with the increase in concentration and contact time, respectively, and their interactive effect on Δ-floatability was insignificant with a very low p-Value of 0.6448. The slight effect of contact time was ascribed to the solution changing from a homogeneous state to a heterogeneous state due to the formation of iron hydroxide precipitates, restricting the effective contact between ferrate (VI) and plastics [43]. As shown in Figure S4b, at a constant contact time of 17.5 min, Δ-floatability also rapidly increased with temperature, which can be explained by the enhanced oxidation potential of high ferrate (VI) concentration and high temperature [12]. This could induce the oxidation of polymers by introducing a large amount of carboxyl and hydroxyl moieties, resulting in a much more hydrophilic PC. Temperature and concentration had an insignificant interactive effect on Δ-floatability, with a high p-Value of 0.9202. Overall, after wettability tailoring, PC and PVC had a distinct floatability due to the difference in surface wettability, and thus Δ-floatability can be enhanced simultaneously by the investigated factors.

2.2.4. Separation Efficiency

The overall desirability function was used to numerically optimize the separation efficiency of plastic mixtures (Section S1). The physical properties of polymers can be remarkably deteriorated even if a little PVC is present during the recycling process. In this regard, the desired separation efficiency was set to 100.0%, and then the optimized conditions were determined, including a concentration of 29.99 mM, a contact time of 10.01 min, and a temperature of 79.12 °C. Confirmatory experiments were performed to verify the optimized conditions and results revealed Δ-floatability reached 99.9%, demonstrating that the factual values were in good agreement with the predicted values. RecoveryPVC, PurityPVC, RecoveryPC, and PurityPC reached 100.0 ± 0.0%, 99.8 ± 0.3%, 99.8 ± 0.3%, and 100.0 ± 0.0%, respectively. We conducted a detailed comparison of the reported methods for separating of mixtures of PC and PVC, which indicated that our method was more effective (Section S2). As a green oxidant, ferrate (VI) improves the sustainability and environmental friendliness of the method [43,44]. In addition, a simple economic feasibility analysis proves that ferrate (VI)-induced wettability tailoring of polymers was feasible to be applied in separating plastic mixtures with flotation (Section S3). Accordingly, ferrate (VI)-induced wettability tailoring of polymers is effective and green, and it can be envisioned to be used in the separation of plastic mixtures toward mechanical recycling to eliminate the environmental problems of plastic waste. Nevertheless, the feasibility of ferrate (VI) oxidation-facilitated flotation separation needs to be further evaluated with a pilot or large-scale experiment, to assess its practical application in the near future.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Plastic Samples and Equipment

Plastic samples of about 2–3 mm in size were purchased (Beijing, China), washed with tap water and ultrapure water successively, dried in a vacuum drier at 40 °C, and identified by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR). PVC and PC, along with molecular structures and FT-IR spectra, are shown in Supporting Information (SI) Figure S5. Ferrate (VI), namely potassium ferrate (K2FeO4), and terpineol were of analytical grade and purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Ultrapure water with a resistivity of about 18.2 MΩ was used throughout the experiments. A self-designed flotation column was used in flotation tests as previously described [45]. In detail, the flotation column is 580 mm height and 60 mm inside with a sand core as a flow diffuser plate installed at the bottom. Design Expert@software, Version 10.0 (Stat-Ease, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was used for optimizing experiment design.

3.2. Wettability Tailoring and Characterization

In single systems, wettability tailoring using ferrate (VI) oxidation was performed. Typically, ferrate (VI) was added to ultrapure water of 100.0 mL in a 200 mL conical flask, PC or PVC samples of 1.0 g were added into the flask, and the mixtures were treated under 0.1 M, at 60.0 °C, for 30.0 min. After reaction, samples were filtrated with standard sieves (2 mm) and washed with ultrapure water several times. The characterization including wettability, surface charge, chemical structures, oxidation degree, and morphology was performed with water contact angle (WCA), zeta potentials measurements, FT-IR, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). WCA was measured with an OCAH200 (Dataphysics, Germany), and the average value of three measurements were reported. During measuring zeta potentials, two measurements were included, and pH was adjusted by adding 0.1 M NaOH or 0.1 M HCl. XPS patterns were recorded using an ESCALAB 250Xi (Thermo Fisher, USA) with an Al Kα radiation. FT-IR (Nicolet iS5, Thermo Scientific, USA) and zeta potentials (SOE-070, Delsa Nano C, Beckman Coulter, USA) were recorded based on a distinct experimental procedure, and the details are shown in Supporting Information Section S4. SEM images were recorded on a S-3400 II (Hitachi, Japan) after gold spraying (10.0 mA) for 3.0 min.

3.3. Flotation Separation Procedures of Plastic Mixtures

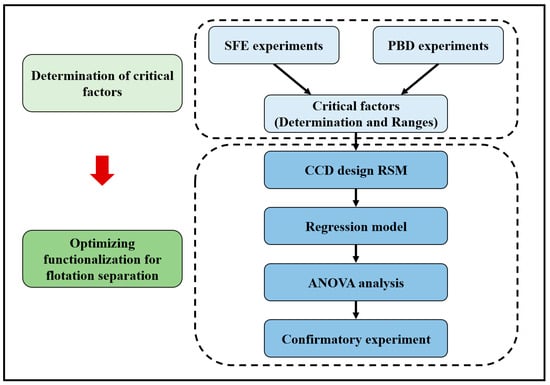

The investigation and optimization were conducted to apply tailoring wettability of polymers into separating mixtures of PC and PVC with flotation. The methodology for the optimization procedures adopted in this work is presented in Figure 6. Initially, the critical factors in ferrate (VI) oxidation were determined with Plackett–Burman design (PBD), and the ranges of factors were confirmed with single-factor experiments (SFEs). In SFE, the conditions included concentration (0–35 mM), contact time (0–30 min), temperature (15–80 °C), and stirring rate (50–400 rpm). Then, we utilized CCD of RSM to regress the model of the tailoring wettability process, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate statistical significances. Lastly, numerical optimization was performed based on the model, and confirmatory experiments were conducted to verify the simulated optimized conditions. For SFE and CCD experiments, two replicates were included and the average values were reported.

Figure 6.

Methodology of the optimization procedure for flotation separation.

- (1)

- Determination of Critical Factors

PBD experiments are suited to multiple factors and assume the absence of interactions of single factors, which is helpful for ruggedness testing to find critical factors. We applied SFE and PBD experiments to screen the critical factors in ferrate (VI) oxidation, and the factors included concentration, contact time, temperature, and stirring rate. The conditions of SFE are shown in Supporting Information Table S2. Typically, mixtures of PVC (5.0 g) and PC (5.0 g) were added into a conical flask with ferrate (VI) solutions of 100 mL under preset conditions. After reaction, plastic samples were washed with similar procedures as in characterization for performing flotation tests under preset conditions (terpineol 16.0 mg/L, flotation time 1.0 min, and air flow rate 7.2 mL/min). These flotation conditions were generally selected for flotation separation of plastic mixtures with similar particle sizes to our study [45]. Then, floated and sunk samples in flotation tests were collected. For PBD experiments, two replicates were included and the average values were reported. Floatability as a direct indicator is used to evaluate separation efficiency, and thus we selected its floatability as the response in this section, which is defined as follows in Equation (3).

where δi is the floatability of plastic i, %; wfi and wsi are the floated and sunk plastic i in flotation tests, g.

- (2)

- CCD Optimization

CCD optimization of RSM was generated using Design Expert@software, Version 10.0 to model the wettability tailoring and optimize separation efficiency of mixtures of PC and PVC. Critical factors confirmed in PBD experiments were selected as variables, and each variable included three levels (Table S3). The difference between the floatability of PVC and the floatability of PC (Δ-floatability) was selected as the response since it directly determines the separation efficiency. Wettability tailoring of plastics was conducted with same procedures as in PBD experiments under preset conditions, and particularly stirring rate in this section was set at 200 rpm. The total runs generated consist of 8 factorial points, 6 axial, 12 points, and 6 center points.

- (3)

- Regression Modeling and Statistical Analysis

Based on the results of CCD optimization, Δ-floatability was variable and well fitted to a quadratic model. ANOVA was used to evaluate the statistical significances of the model and the terms of factors, and, in particular, a p < 0.05 can be considered statistically significant. The overall desirability function was utilized to optimize separation efficiency and numerically simulate the optimized conditions, and its details are shown in Section S1. The quadratic model used is shown as follows in Equation (4).

where Y is response (Δ-floatability), and Xi and Xj are independent variables (namely critical factors); α0, αi, αii, and αij are the constant, liner, quadratic, and interactive coefficients, respectively.

- (4)

- Separation Efficiency

The confirmatory experiments were performed to verify the model soundness, and these experiments were conducted under the optimized conditions via simulation. For confirmatory experiments, three replicates were included and the average values were reported. In addition, the recovery of PVC (RecoveryPVC), the purity of PVC (PurityPVC), the recovery of PC (RecoveryPC), and the purity of PC (PurityPC) were selected as the indicators for evaluating the separation efficiency of proposed method. Results indicated that PVC samples as floated products and PC samples as sunk products were collected after wettability tailoring in flotation tests, and thus RecoveryPVC, PurityPVC, RecoveryPC, and PurityPC are defined as follows in Equations (5)–(8), respectively.

where α1 and β1 are RecoveryPVC and PurityPVC, α2 and β2 are RecoveryPC and PurityPC, respectively; wf1, ws1, wf2, and ws2 are PVC floated, PVC sunk, PC floated, and PC sunk, g, respectively.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we evaluated ferrate (VI)-induced polymer wettability tailoring and its application in separating mixtures of PC and PVC via floatation for recycling. Ferrate (VI) was found to selectively facilitate the wettability tailoring of PC via oxidation. The sp3-C (C-C/C-H) on the surfaces of PC as original sites can be selectively oxidized into oxygen functionalities, including carboxyl and hydroxyl moieties, by ferrate (VI). This tailoring was found to be more effective for PC than PVC, endowing PC with a more hydrophilic surface. Based on this selectivity, ferrate (VI)-induced wettability tailoring was applied to the flotation separation of mixtures of PC and PVC. Optimizing ferrate (VI) treatment was conducted using CCD of RSM to generate models for depicting the wettability tailoring process and obtaining the optimized conditions. After wettability tailoring under the optimized conditions, PC and PVC exhibited distinct floatability in flotation, and their mixtures can be separated effectively. RecoveryPVC, PurityPVC, RecoveryPC, and PurityPC reach up to 100.0 ± 0.0%, 99.8 ± 0.3%, 99.8 ± 0.3%, and 100.0 ± 0.0%, respectively. Overall, this work could contribute to the fundamental understanding of ferrate-induced wettability tailoring of polymer materials, and also expand its emerging applications in the mechanical recycling of waste plastics for eliminating the severe pollution of plastic waste.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/separations13010005/s1, Figure S1: The full XPS spectra of plastics before and after ferrate (VI) oxidation; Figure S2: The Fe 2p spectrum on the surface of PC plastics obtained from the XPS analysis; Figure S3: The normal probability plots of the model; Figure S4: Three-dimensional plots for the effect of factors on Δ-floatability; Figure S5: The FT-IR, molecular structures, and images of plastics; Figure S6 The set of various factors and the results of optimization; Table S1: The ANOVA results of PBD experiment for screening critical factors; Table S2: The experimental design of SFEs for ferrate (VI) oxidation; Table S3: The levels and codes of variables in CCD optimization; Section S1: The details of overall desirability function in CCD optimization [46,47,48]; Section S2: A detailed comparison of reported methods for separation of the PC and PVC plastic mixtures [27,49,50]; Section S3: A simple analysis of economic feasibility for the proposed method; Section S4: The experimental procedures for recording FT-IR spectra and measuring zeta potential of plastics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.S. and Y.J.; methodology, X.S.; software, Q.W.; validation, X.S., Y.J. and Q.W.; formal analysis, X.C.; investigation, X.S.; resources, Q.W.; data curation, X.C.; writing—original draft preparation, X.S.; writing—review and editing, Y.W.; visualization, Y.J.; supervision, Y.W.; project administration, Y.W.; funding acquisition, Y.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding authors. Due to institutional policy restrictions, they are not publicly available.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to all research group members for their valuable suggestions, technical assistance, and continuous support throughout this study. The authors also thank all colleagues and friends who provided help and encouragement during the experiments and manuscript preparation process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sarma, R.; Angeles-Boza, A.M.; Brinkley, D.W.; Roth, J.P. Studies of the di-iron (VI) Intermediate in ferrate-dependent oxygen evolution from water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 15371–15386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.K.; Chen, L.; Zboril, R. Review on High Valent Fe VI (Ferrate): A Sustainable Green Oxidant in Organic Chemistry and Transformation of Pharmaceuticals. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2015, 4, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Chu, W.; Xu, K.; Xia, X.; Gong, H.; Tan, Y.; Pu, S. Efficient degradation, mineralization and toxicity reduction of sulfamethoxazole under photo-activation of peroxymonosulfate by ferrate (VI). Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 389, 124084–124096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.S.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.L.; Jiang, J.; Xue, M.; Xu, C.B.; Zhen, Y.F.; Wang, Y.C.; Ma, J. Impact of Phosphate on Ferrate Oxidation of Organic Compounds: An Underestimated Oxidant. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 13897–13907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, V.K.; Feng, M.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Zhou, H.C.; Jinadatha, C.; Manoli, K.; Smith, M.F.; Luque, R.; Ma, X.; Huang, C.H. Reactive High-Valent Iron Intermediates in Enhancing Treatment of Water by Ferrate. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Goodwill, J.E.; Tobiason, J.E.; Reckhow, D.A. Impacts of ferrate oxidation on natural organic matter and disinfection byproduct precursors. Water. Res. 2016, 96, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hang, J.; Guo, Z.; Zhong, C.; Sun, A.; He, K.; Liu, X.; Song, H.; Li, J. A super magnetic porous biochar manufactured by potassium ferrate-accelerated hydrothermal carbonization for removal of tetracycline. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 435, 140470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Zhao, Y.; Qv, C.; Mao, X.H. Mechanism and Efficiency of Tetracycline Removal by Ferrate and Ferrous-Enhanced Ferrate System. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2023, 234, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.Q.; Lloyd, B. Progress in the development and use of ferrate (VI) salt as an oxidant and coagulant for water and wastewater treatment. Water Res. 2002, 36, 1397–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Xu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wei, Y.; Sun, H.; Li, Z.; Zhao, X.; Gao, C. An iron-based green approach to 1-h production of single-layer graphene oxide. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 5716–5725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofer, Z.; Luxa, J.; Jankovsky, O.; Sedmidubsky, D.; Bystroň, T.; Pumera, M. Synthesis of Graphene Oxide by Oxidation of Graphite with Ferrate (VI) Compounds: Myth or Reality? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 11965–11969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, X.; Li, J.; Li, T. Versatile Functionalization of Carbon Nanomaterials by Ferrate (VI). Nano-Micro Lett. 2020, 12, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.Y.; Xu, X.C. Nondestructive covalent functionalization of carbon nanotubes by selective oxidation of the original defects with K2FeO4. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 346, 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura, S.; Jiang, Y.; Vassalini, I.; Gianoncelli, A.; Alessandri, I.; Granozzi, G.; Calvillo, L.; Senes, N.; Enzo, S.; Innocenzi, P.; et al. Graphene Oxide/Iron Oxide Nanocomposites for Water Remediation. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2018, 1, 6724–6732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, S.; Hagiwara, K.; Hasebe, T.; Hotta, A. Surface modification of polymers by plasma treatments for the enhancement of biocompatibility and controlled drug release. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2013, 233, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Nishimura, S.; Nishiyama, K.; Aso, Y.; Nishida, H.; Cho, S.; Sekino, T. Direct In Situ Polymer Modification of Titania Nanomaterial Surfaces via UV-irradiated Radical Polymerization. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2024, 13, e202400270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilfanov, S.A.; Timoshina, Y.A. Influence of Gas-Discharge Modification on Physical and Chemical Properties of the Surface of Polymer Materials. High Energy Chem. 2024, 58, S323–S326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Fukazawa, K.; Ishihara, K. Photoreactive Polymers Bearing a Zwitterionic Phosphorylcholine Group for Surface Modification of Biomaterials. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2015, 7, 17489–17498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Yue, D. Optimization of Surface Treatment Using Sodium Hypochlorite Facilitates Coseparation of ABS and PC from WEEE Plastics by Flotation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 2086–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerhuber, P.F.; Wang, T.; Krause, A. Wood–plastic composites as potential applications of recycled plastics of electronic waste and recycled particleboard. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 121, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villard, A.; Lelah, A.; Brissaud, D. Drawing a chip environmental profile: Environmental indicators for the semiconductor industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 86, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Xu, M.; Wang, H.; Zuo, T. To realize better Extended Producer Responsibility: Redesign of WEEE fund mode in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 164, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, S.S.; Mohanty, S.; Nayak, S.K. Preparation and characterization of recycled blends using Poly (vinyl chloride) and Poly (methyl methacrylate) recovered from waste electrical and electronic equipments. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 149, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohr, T.; Ogletree, D.F.; Svec, F.; Fréchet, J.M.J. Surface Functionalization of Thermoplastic Polymers for the Fabrication of Microfluidic Devices by Photoinitiated Grafting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2003, 13, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truc, N.T.T.; Lee, B.K. Sustainable and Selective Separation of PVC and ABS from a WEEE Plastic Mixture using Microwave and/or Mild-heat Treatment with Froth Flotation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 10580–10587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallampati, S.R.; Heo, J.H.; Park, M.H. Hybrid selective surface hydrophilization and froth flotation separation of hazardous chlorinated plastics from E-waste with novel nanoscale metallic calcium composite. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 306, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Huang, L. A novel process for separation of polycarbonate, polyvinyl chloride and polymethyl methacrylate waste plastics by froth flotation. Waste Manag. 2017, 65, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truc, N.T.T.; Lee, B.K. Selective separation of ABS/PC containing BFRs from ABSs mixture of WEEE by developing hydrophilicity with ZnO coating under microwave treatment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 329, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.K.; Wang, H.; Novel, A. Clean, and Low Reagent Consumption Ultraviolet (UV) Irradiation-Plastic Flotation Process for Separating Multi-plastics. J. Polym. Environ. 2024, 32, 4348–4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbari, S.; Movahed, S.O.; Jourabchi, S. Application of a dual depressant system and microwave irradiation for flotation-based Separation of Polyethylene Terephthalate, Polyvinyl Chloride, and Polystyrene Plastics. Polym. Polym. Compos. 2024, 32, 09673911241248418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Paino, M.; Amer, M.H.; Nasir, A.; Crucitti, V.C.; Thorpe, J.; Burroughs, L.; Needham, D.; Denning, C.; Alexander, M.R.; Alexander, C.; et al. Polymer Microparticles with Defined Surface Chemistry and Topography Mediate the Formation of Stem Cell Aggregates and Cardiomyocyte Function. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2019, 11, 34560–34574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, I.S.; Singh, G.; Smith, P.; Kim, S.; Yang, J.-H.; Joseph, S.; Yusup, S.; Singh, M.; Bansal, V.; Talapaneni, S.N.; et al. Oxygen functionalized porous activated biocarbons with high surface area derived from grape marc for enhanced capture of CO2 at elevated-pressure. Carbon 2020, 160, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.S.; Kurose, K.; Okuda, T.; Nishijima, W.; Okada, M. Separation of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) from automobile shredder residue (ASR) by froth flotation with ozonation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 147, 1051–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, T.; Kurose, K.; Nishijima, W.; Okada, M. Separation of Polyvinyl Chloride from Plastic Mixture by Froth Flotation after Surface Modification with Ozone. Ozone Sci. Eng. 2007, 29, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, R.K.; Neyhouse, B.J.; Young, M.S.; Fagnani, D.E.; McNeil, A.J. Revisiting poly (vinyl chloride) reactivity in the context of chemical recycling. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 5802–5813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, K.C.; Xuan, S.; Lo, C.M. Reversible switching between hydrophilic and hydrophobic superparamagnetic iron oxide microspheres via one-step supramolecular dynamic dendronization: Exploration of dynamic wettability. ACS Appl. Mater Interfaces 2009, 1, 2005–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keefe, A.J.; Brault, N.D.; Jiang, S. Suppressing Surface Reconstruction of Superhydrophobic PDMS Using a Superhydrophilic Zwitterionic Polymer. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 1683–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Jiang, H.; Du, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, H. Surface alcoholysis induced by alkali-activation ethanol: A novel scheme for binary flotation of polyethylene terephthalate from other plastics. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 314, 128096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behboodi-Sadabad, F.; Trouillet, V.; Welle, A.; Messersmith, P.B.; Levkin, P.A. Surface Functionalization and Patterning by Multifunctional Resorcinarenes. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2018, 10, 39268–39278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duch, J.; Mazur, M.; Golda-Cepa, M.; Podobiński, J.; Piskorz, W.; Kotarba, A. Insight into the modification of electrodonor properties of multiwalled carbon nanotubes via oxygen plasma: Surface functionalization versus amorphization. Carbon 2018, 137, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejaegher, B.; Dumarey, M.; Capron, X.; Bloomfield, M.S.; Heyden, Y.V. Comparison of Plackett-Burman and supersaturated designs in robustness testing. Anal. Chim. Acta 2007, 595, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastyar, W.; Zhao, M.; Yuan, W.; Li, H.; Ting, Z.J.; Ghaedi, H.; Yuan, H.; Li, X.; Wang, W. Effective Pretreatment of Heavy Metal-Contaminated Biomass Using a Low-Cost Ionic Liquid (Triethylammonium Hydrogen Sulfate): Optimization by Response Surface Methodology–Box Behnken Design. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 11571–11581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Jung, C.; Liang, Y.; Goodey, N.; Waite, T.D. Ferrate (VI) Decomposition in Water in the Absence and Presence of Natural Organic Matter (NOM). Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 334, 2335–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.K. Potassium ferrate (VI): An environmentally friendly oxidant. Adv. Environ. Res. 2002, 6, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.C.; Wang, H. Fenton treatment for flotation separation of polyvinyl chloride from plastic mixtures. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 187, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattoraj, S.; Mondal, N.K.; Das, B.; Roy, P.; Sadhukhan, B. Biosorption of carbaryl from aqueous solution onto Pistia stratiotes biomass. Appl. Water Sci. 2014, 4, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthilkumaar, S.; Kalaamani, P.; Subburaam, C.V. Liquid phase adsorption of Crystal violet onto activated carbons derived from male flowers of coconut tree. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 136, 800–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, P.; Chowdhury, S.; Gupta, S.; Kumar, I.; Kumar, R. Assessment on the removal of malachite green using tamarind fruit shell as biosorbent. Clean Soil Air Water 2010, 38, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupo, E.; Moroni, M.; La, M.F.; Fulco, S.; Pinzi, V. Investigation on an innovative technology for wet separation of plastic wastes. Waste Manag. 2016, 51, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hui, W.; Wang, C.; Zhang, L.; Tao, W.; Long, Z. A novel process for separation of hazardous poly (vinyl chloride) from mixed plastic wastes by froth flotation. Waste Manag. 2017, 69, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.