Abstract

The aim of the present study was to analyze the association of bullying and cyberbullying with the level of Internet, cell phone, and video game use in children and adolescents. In total, 677 Spanish students (53.03% girls) aged 10 to 16 years (13.81 ± 1.56) participated. The association between variables and risk of exposure was carried out by analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) and binary logistic regression (odds ratio = OR), respectively. The effects of both victimization and perpetration in bullying and cyberbullying were analyzed separately to identify differences by role. All analyses were performed separately for boys and girls and adjusted for age, body mass index, mother’s education, and average weekly physical activity. The results showed that both victims and perpetrators of bullying and cyberbullying present a significant increase in and risk of abusive and inappropriate use of the Internet, cell phones, and video games. Girls involved in bullying/cyberbullying behaviors reached the highest levels of inappropriate use of the Internet, cell phones, and video games with respect to peers not affected by bullying behaviors. In all cases, girls, both victims and perpetrators of bullying and cyberbullying, multiplied the risk of harmful use of these devices by at least 3 times. It is suggested to implement educational policies to prevent situations, especially cyberbullying, in both victims and perpetrators, prioritizing student safety.

1. Introduction

In today’s society, Internet use among children and adolescents has increased considerably in recent years due to the easy access and expansion of technology (; ). Several studies have concluded that between 65% and 78% of children and young people, respectively, consume the Internet excessively on a daily basis (; ), and addiction to cell phones now affects all social strata, with 15% of young people spending more than four hours a day online (). This abuse in the use of mobile devices has aroused scientific interest due to the negative impact it has on physical, emotional, and social health (). At the physiological level, it has been shown that the overuse of electronic devices leads to structural changes in the brains of young people (; ) as impairment in cognitive control during emotional processing (; ) and reduction in functional connectivity in brain regions related to cognitive control of emotional stimuli (; ). On the other hand, the excessive consumption of video games in young people is associated with significant risks of low psychological well-being (), poor nutrition (), anxiety (), social isolation, and depression (). Despite the above, some video games, especially those with an interactive design, can promote physical activity and the development of social and cognitive skills (). In addition, factors such as the intrinsic and extrinsic motivation of young people can mediate the frequency of video game use due to the usefulness of these technologies and their integration in learning activities ().

According to recent studies, the excessive use of the Internet, mobile devices, and video games also impairs the cognitive control of young people and reduces their ability to manage emotions, considered key factors for maintaining healthy social relationships (). Another common aspect of the overuse of these technological applications is their relationship with the appearance of bullying behaviors or attitudes in children and adolescents, such as bullying and cyberbullying (; ). It seems that young people take refuge in new technologies to avoid situations of harassment or bullying because the virtual environment provides a temporary escape from reality (; ).

Although many studies consider that the abuse of technology can contribute to the development of bullying behavior, it is essential to consider the opposite effect as well. The consequences of bullying, considered as a manifestation of mistreatment between students, characterized by acts of physical or mental violence and maintained over time (), could generate a rebound effect by further increasing the time spent on the Internet, using cell phones, and playing video games (). Moreover, the repercussions of these bullying behaviors affect victims, as well as perpetrators and observers, manifesting themselves in behaviors of impulsivity, anger, and school violence (; ) that have a very negative influence on the educational environment of adolescents (; ; ). Cyberbullying, on the other hand, is characterized by its persistent nature and the ease with which perpetrators can hide their identity () and has more long-term implications for the students involved, such as low self-esteem (), mental health problems (), low social development (), and poor academic performance (; ).

Recent studies have also revealed that young people may respond differently to the above stimuli depending on their age (), body mass index [BMI] (), weekly physical activity (), and their parents’ level of studies (). A high BMI has been linked to a higher risk of victimization and lower self-esteem, which could favor greater dependence on online activities (). Likewise, regular physical activity is related to greater psychological well-being and may act as a protective factor against the problematic use of technologies and involvement in bullying situations (). Finally, maternal educational level is considered a predictor of cognitive development and self-regulation in adolescence, variables that influence both involvement in bullying behaviors and the responsible use of digital devices (; ). In addition, it appears that adolescents of different sexes tend to experience and engage in bullying unequally (). While boys are more likely to engage in direct and physical forms of bullying, girls are more likely to engage in relational bullying such as social exclusion and rumor spreading (). Girls may also be more vulnerable to cyberbullying due to their greater concern for appearance and social acceptance, which makes them more susceptible to virtual psychological attacks (). On the other hand, boys may pressure their peers to demonstrate their dominance and power through aggressive online behavior (). These dynamics, together with differential access to and use of technologies, contribute to the fact that the experiences and consequences of bullying and cyberbullying vary significantly between sexes.

Numerous studies have addressed the association of school bullying and cyberbullying with the abuse of Internet and cell phone use (; ; ; ) and video games (; ; ). However, the explicit association of victimization and perpetration with the excessive use of these technologies has been little explored (). The present research provides a pioneering approach in differentiating the roles of bullying, which may offer new insights into how both victims and perpetrators of bullying may overuse and addictively use new technologies (). Based on the above, the aim of the present study was to analyze the possible association of bullying and cyberbullying with the use of the Internet, cell phones, and video games in the Spanish school and adolescent population of both sexes, after adjusting for age, BMI, mother’s level of education, and average physical activity. We also sought to determine the level of risk involved in bullying victimization/perpetration and cyberbullying in relation to abusive use of the Internet, cell phones, and video games. We hypothesized that those young people with a higher level of participation in bullying and/or cyberbullying, regardless of their role, would in turn have higher levels of inappropriate Internet, cell phone, and video game use.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 677 primary and secondary school students aged 10–16 years (mean age ± standard deviation: 13.81 ± 1.56 years) (53.03% girls and 46.97% boys) participated in the present cross-sectional quantitative study. Data collection took place from February to May 2023. Seven educational centers in various provinces of Andalusia were studied, of which three were publicly owned and four subsidized—three rural and four urban centers of a medium socioeconomic level. The sample was selected by convenience. The anthropometric and sociodemographic characteristics are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Biometric characteristics; sociodemographic data of participants; average MVPA; bullying and cyberbullying variables; and Internet, cell phone, and video game use segmented by sex.

2.2. Predictor/Independent Variables

Bullying and cyberbullying

The level of bullying was assessed using the “European bullying intervention project questionnaire” instrument, Spanish version, from (), 14 items. To assess cyberbullying, we used the Spanish version of the “European cyberbullying intervention project questionnaire” (ECIPQ; ) which includes 22 items. Reliability scores were high for both bullying (Crombach’s α victimization = 0.830 and Crombach’s α perpetration = 0.811) and cyberbullying (α cybervictimization = 0.821 and α cyberperpetration = 0.837). Both questionnaires were administered individually and employ a Likert-type scale with a score ranging from 1 = never to 5 = more than once a week. The items explore the frequency with which the described behaviors have occurred during the past two months, and both required approximately 15 min to complete.

2.3. Dependent Variables

Internet, cell phone, and video game use

The “Spanish PIUQ-9” instrument was used to quantify the level of Internet, cell phone, and video game use (), and it was designed to assess the psychological and behavioral impact of problematic Internet use along three main dimensions (obsession, neglect, and control disorder). “SAS-SV” () was used to measure the degree of dependence on cell phones and assess how it affects students’ emotional attachment, compulsion, withdrawal symptoms, and difficulty in reducing bullying, and, to assess the degree of dependence on cell phones, “Internet Gaming Disorder Scale–Short–Form (IGDS9–SF)” was used (). The latter measures dependence symptoms in online video game players by assessing problematic behaviors and experiences related to Internet gaming. Each instrument included 9 items and used a Likert-type scale, with scores ranging from 1 = never/totally disagree to 5 = almost always/always/totally agree, with the highest score being the maximum level of Internet, smartphone, and video game use addiction in the past year. All questionnaires were administered individually and presented high levels of reliability—Internet use (Crombach’s α = 0.831), cell phone use (Crombach’s α = 0.849), and video game use (Crombach’s α = 0.813).

2.4. Confounding Variables

Age, body mass index, mother’s education, and average weekly physical activity

The age and educational level of the mother of each participant were recorded by means of a sociodemographic data questionnaire. Age was considered a confounding variable given its relevance in previous studies, where it has been shown that maturational and emotional development, together with psychological factors, significantly influence the management of stress associated with bullying. Similarly, the maternal educational level has been related to cognitive development and self-regulation in adolescents, which may affect both their involvement in bullying behaviors and their use of digital technologies (; ; ; ). BMI was calculated using the Quetelet formula: weight (kg)/height2 (m). To obtain weight and height measurements, an ASIMED® type B, class III digital scale and a SECA® 214 portable measuring rod (SECA Ltd., Hamburg, Germany) were used. Both measurements were taken in light clothing and without footwear. The level of weekly physical activity was assessed using the “PACE+ Adolescent physical activity measure physical” questionnaire (). This consists of two items asking the number of days in which the participants have performed at least 60 min of physical activity at moderate or vigorous intensity during the last 7 days and during a typical week. The final score was obtained by averaging both responses (P1 + P2)/2). Its reliability index was α = 0.744. Both BMI and weekly physical activity were considered since they are related to physical and mental well-being, as well as to students’ learning and self-esteem (; ).

2.5. Procedure

Data collection was conducted during the 2022/2023 academic year. The purpose and nature of the study were communicated verbally and in writing to students, parents, and legal guardians. Authorization was obtained from the school administration and physical education teachers. All the students involved were informed, prior to filling out the questionnaires, about the concepts of bullying and cyberbullying, including examples of behaviors that can be identified with these forms of harassment. In order to preserve confidentiality and anonymity, the names of the participants were coded. During the completion of the questionnaires and weight and height measurements, a specialized researcher gave the instructions and controlled the time, while two research assistants observed possible doubts and any possible disturbances (e.g., separation space to guarantee the confidentiality of the answers, prevent noise outside the classroom, avoid confusing students, operate electronic tools, and provide an Internet connection). The estimated time to complete all questionnaires, relative to the dependent and independent variables, was approximately 15 min. This study was approved by the Bioethics Commission of the University of Jaén (Spain), reference NOV.22/2.PRY. The design took into account the current Spanish legal regulations governing clinical research in humans (Royal Decree 561/1993 on clinical trials), as well as the fundamental principles established in the Declaration of Helsinki (2013, Brazil).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Comparison of the continuous and categorical variables between boys and girls was carried out using Student’s t test and χ2 tests, respectively. The normality and homoscedasticity of the data were verified using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Levene tests, respectively. To study whether adolescents who had never experienced bullying and cyberbullying victimization/perpetration were more likely to abuse the Internet, cell phones, and video games than those who had been victims/perpetrators, an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed. Measures of Internet, cell phone, and video game use were used as dependent variables, and bullying victimization, bullying perpetration, cyberbullying victimization, and cyberbullying perpetration were introduced as fixed factors. The bullying and cyberbullying values were dichotomized such that participants who stated that they had never been a victim/offender of bullying and/or cyberbullying (questionnaire score = 1) were labeled as “Never”, and those who had ever been a victim/offender (questionnaire score = 2–5) were labeled as “Sometimes”. For the above categorization, the specific nature of the phenomenon of bullying has been taken into account, where it cannot be assumed that an occasional score (e.g., “sometime”) indicates the absence of victimization or aggression. It has been considered relevant to highlight any involvement, even if occasional, as even isolated events can have a significant impact on the psychological and social well-being of minors ().

Because many comparison groups had different sample sizes, effect sizes were calculated using Hedges’ ğ, where 0.2 = small effect, 0.5 = medium effect, and 0.8 = large effect (). The percentage of difference between groups was calculated as [(Large-measurement − small-measurement)/small-measurement] × 100. To determine the level of risk of bullying victimization/perpetration and cyberbullying as having lower values in the level of Internet, cell phone and video game use, a binary logistic regression was carried out. For this purpose, the dependent variables were dichotomized, taking the median as a reference (; ). Each strategy was classified as high ≥ median (reference group) vs. low < median (risk group). In addition to the dichotomous categorization of participants as “Never” vs. “Sometimes” involved in bullying/cyberbullying, an additional classification was introduced to distinguish the frequency of involvement. Following prior prevalence studies in Spanish school populations (; ), participants were classified as frequent if they reported involvement “once a week” or “more than once a week” (Likert score ≥ 4) and as occasional if they reported involvement “occasionally” or “once or twice a month” (Likert score = 2 or 3). This distinction was applied separately for both victimization and perpetration in traditional bullying and cyberbullying.

In all analyses, age, BMI, mother’s educational level, weekly physical activity, and academic performance were used as covariates. Analyses were performed separately for boys and girls. A 95% confidence level (p < 0.05) was used for all results. All calculations were performed with the statistical program SPSS, v. 25.0 for WINDOWS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results

General Descriptive Analysis

As previously detailed in the Methods section, the participants were further classified as frequent or occasional according to their responses to the questionnaires. Frequent involvement was considered to be that for whom frequency was once a week or more (Likert score ≥ 4), and occasional involvement was considered to be less than once a week (scores 2–3).

In relation to traditional bullying victimization, 82.3% of the student body indicated that they had been victims at some time. Of these, 7.7% were classified as frequent victims, while 74.6% were occasional victims. Only 17.7% stated that they had never been assaulted. Regarding perpetration, 4.3% were frequent offenders and 65.9% were occasional offenders, compared to 29.8%, who reported having never been bullied. In terms of sexes, boys showed slightly higher percentages of frequent aggressive behaviors (3.2% once a week vs. 1.9% of girls).

On the other hand, in the case of cyberbullying, 2.6% of the student body were frequent victims, compared to 52.9% of occasional victims, while 44.5% reported never having suffered it. Cyberbullying perpetration was referred to by 3.4%, who were frequent offenders, and 43.1%, who were occasional offenders. Girls showed a higher prevalence in occasional cyberbullying victimization (51.7%) compared to boys (45.3%).

Covariance analysis of victimization and perpetration in bullying and cyberbullying with respect to internet use.

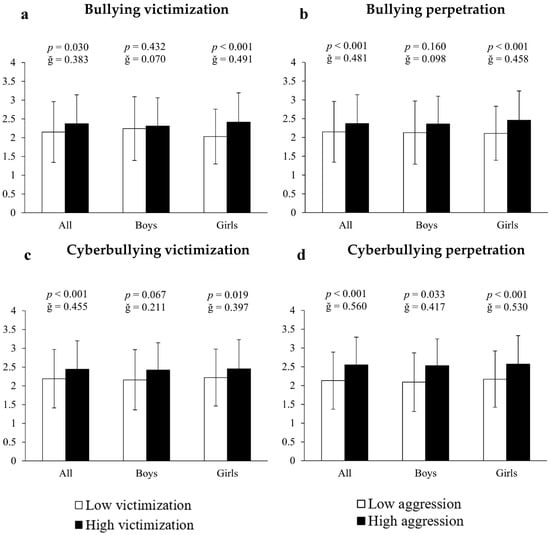

Analysis of covariance employing inappropriate internet use as the dependent variable and bullying measures as the fixed factor showed that, in all cases, victims and perpetrators of bullying, as well as victims and perpetrators of cyberbullying, presented significantly higher scores (10.23%, 13.68%, 11.42% and 19.72%, respectively) of internet abuse compared to all other participants (all F[1,661] > 11.213, p < 0.030, ğ > 0.383, Figure 1a–d). When the results were differentiated by sex it was found that, in all cases, girls immersed in bullying situations had significantly higher scores of inappropriate internet use: (A) for bullying victims = 18.72% (2.41 ± 0.78 vs. 2.03 ± 0.73 a.u., F[1,351] = 13.351, p < 0.001, ğ = 0.491, 1 − β = 0.954, Figure 1a); (B) for bullying perpetrators = 16.59% (2.46 ± 0.78 vs. 2.11 ± 0.72 a.u., F[1,351] =16.242, p < 0.001, ğ = 0.458, 1 − β = 0.980, Figure 1b); (C) for cyberbullying victims = 10.36% (2.45 ± 0.78 vs. 2.22 ± 0.76 a.u., F[1,351] = 14.609, p < 0.019, ğ = 0.397, 1 − β = 0.927, Figure 1c) and (D) for cyberbullying perpetrators = 18.43% (2.57 ± 0.76 vs. 2.17 ± 0.75 a.u., F[1,351] = 27.807, p < 0.001, ğ = 0.530, 1 − β = 0.999, Figure 1d). For boys, the results showed 21.05% more inappropriate internet use in cyberbullying perpetrators (2.53 ± 0.71 vs. 2.09 ± 0.78 a.u., F[1,304] = 21.894, p = 0.033, ğ = 0.5876, 1 − β = 0.967). No significant differences were found in either victims or victims/offenders of bullying (all p > 0.05).

Figure 1.

Association of victimization and perpetration in bullying and cyberbullying with respect to internet use.

Covariance analysis of victimization and perpetration in bullying and cyberbullying with respect to cell phone use.

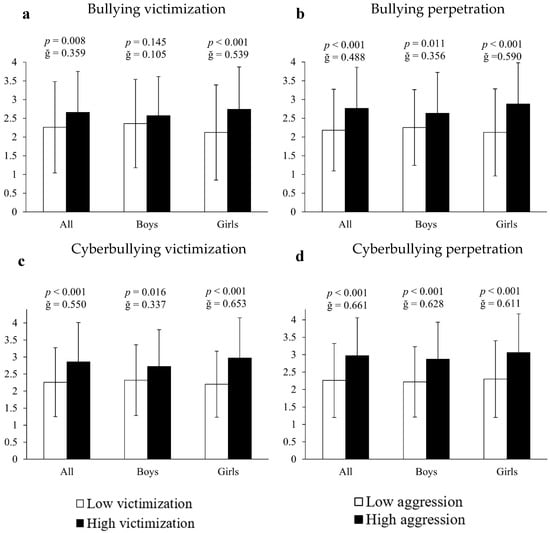

The analysis of covariance employing inappropriate or unhealthy cell phone use as the dependent variable and bullying measures as the fixed factor showed that, in all cases, victims and perpetrators of bullying, as well as victims and perpetrators of cyberbullying, presented higher indicators of cell phone abuse (26.55%, 26.61%, 26.55% and 31.42%, respectively) compared to all other participants (all F[1,661] > 14.363, p < 0.009, ğ > 0.358; Figure 2a–d). Results segmented by sex showed that, in all cases, girls involved in bullying contexts had significantly higher scores of inappropriate cell phone use: (A) bullying victims = 29.25% (2.74 ± 1.13 vs. 2.12 ± 1.17 a.u., F[1,351] = 14.171, p < 0.001, ğ = 0.539, 1 − β = 956, Figure 2a); (B) bullying perpetrators = 35.85% (2.88 ± 1.11 vs. 2.12 ± 1.16 a.u., F[1,351] = 35.474, p < 0.001, ğ = 0.590, 1 − β = 0.999, Figure 2b); (C) cyberbullying victims = 35% (2.97 ± 1.15 vs. 2.2 ± 1.1 a.u., F[1,351] = 56.333, p < 0.001, ğ = 0.653, 1 − β = 0.999, Figure 2c) and (D) cyberbullying perpetrators = 33.04% (3.06 ± 1.11 vs. 2.3 ± 1.1 a.u., F[1,351] = 46.874, p < 0.001, ğ = 0.611, 1 − β = 0.991, Figure 2d). For their part, boys immersed in bullying situations manifested significantly more inappropriate cell phone use: (A) bullying perpetrators = 16.89% (2.63 ± 1.09 vs. 2.25 ± 1.01 a.u., F[1,304] = 9.497, p = 0.011, ğ = 0.357, 1 − β = 0.719, Figure 2b); (B) cyberbullying victims = 14.01% (2.64 ± 1.04 vs. 2.27 ± 1.08 a.u., F[1,304] = 9.753, p = 0.016, ğ = 0.337, 1 − β = 0.845, Figure 2c) and (C) cyberbullying perpetrators = 29.28% (2.87 ± 1.09 vs. 2.22 ± 1.01 a.u., F[1,304] = 28.272, p < 0.001, ğ = 0.628, 1 − β = 0.979, Figure 2d). However, no significant differences were found in boys who were victims of bullying (p > 0.05).

Figure 2.

Association of victimization and perpetration in bullying and cyberbullying with respect to cell phone use.

Covariance analysis of bullying and cyberbullying victimization with respect to video game use.

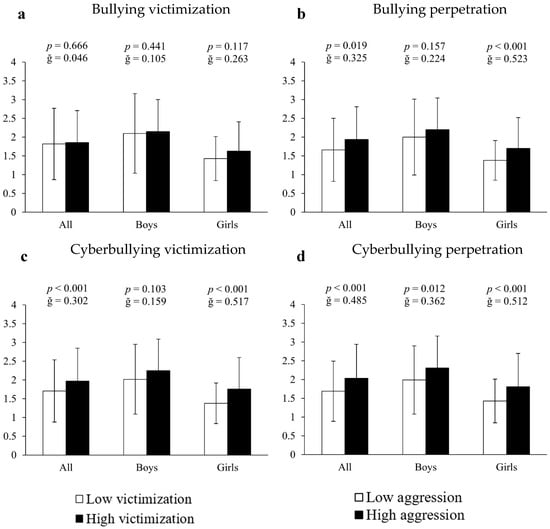

Analysis of covariance using inappropriate or unhealthy video game use as the dependent variable and bullying measures as the fixed factor showed that both bullying perpetrators and cyberbullying victims and offenders had higher values of video game abuse (16.87%, 15.20% and 20.71%, respectively) compared to the rest of the participants (all significant: F[1,661] > 13.158, p < 0.020, ğ > 0.301; Figure 2b–d). Sex-segmented analysis revealed inappropriate video game use in: (A) bullying perpetrators = 23.19% (1.7 ± 0.82 vs. 1.38 ± 0.53 a.u., F[1,351] = 24.315, p < 0.001, ğ = 0.523, 1 − β = 0.945, Figure 3b); (B) cyberbullying victims = 27.54% (1.7 ± 0.82 vs. 1.38 ± 0.53 a.u., F [1,351] = 26.416, p < 0.001, ğ = 0.517, 1 − β = 0.979, Figure 3c) and (C) cyberbullying perpetrators = 26.57% (1.81 ± 0.89 vs. 1.43 ± 0.58 a.u., F[1,351] = 27.916, p < 0.001, ğ = 0.512, 1 − β = 0.966, Figure 3d). In boys, inappropriate video game use was observed in cyberbullying perpetrators = 16.08% (2.31 ± 0.85 vs. 1.99 ± 0.91 a.u., F[1,304] = 6.424, p = 0.012, ğ = 0.362, 1 − β = 0.715, Figure 3d), but not between victims and perpetrators of bullying and victims of cyberbullying (all p > 0.05, Figure 3a–c).

Figure 3.

Association of victimization and perpetration in bullying and cyberbullying with respect to the use of video games.

Binary logistic regression on bullying and cyberbullying victimization and perpetration with respect to internet, cell phone and video game use.

The data showing the risk of exposure to bullying and cyberbullying (victimization and perpetration) with respect to internet, cell phone and video game abuse are presented in Table 2. Overall, bullied schoolchildren were shown to have 1.60 and 2.07 times the risk of inappropriate use of the internet (OR = 1.606; p < 0.001) and cell phone (OR = 2.017; p < 0.001) than those who were not bullied, respectively. Bullied girls had a higher risk of abusing the internet (OR = 2.080; p < 0.001), cell phone (OR = 2.898; p < 0.001) and video games (OR = 1.767; p < 0.001). On the other hand, bullying perpetrators expressed 2.11, 2.52 and 3 times more risk of inappropriate use of internet, cell phone and video games, respectively (all p < 0.001). Both bullying boys and bullying girls were more likely to have unhealthy internet (OR = 1.503; p = 0.027 and OR = 3.826; p < 0.001, respectively) and cell phone use (OR = 1.659; p = 0.006 and OR = 8.068; p < 0.001, respectively). On the other hand, the risk of inappropriate use of video games was increased 3.40 times in bullying girls (p < 0.001) but not in boys (p > 0.05).

Table 2.

Odds ratio (OR) and confidence intervals (95% CI) for levels of victimization/perpetration in bullying and cyberbullying. Internet, cell phone and video game use were included in the logistic regression as a categorical variable (low vs. high). The OR was adjusted for age, body mass index, mother’s educational level and average weekly physical activity.

The cyberbullying data indicated that cyberbullying victims had a 4.53, 7.98 and 4.61 times higher risk of misusing the internet compared to those who did not suffer cyberbullying. According to gender, in boy and girl victims of cyberbullying, there was a higher probability of abusive use of the internet (OR = 3.279; p = 0.006 and OR = 5.998; p < 0. 001, respectively), cell phone (OR = 4.585; p = < 0.001 and OR = 16.473; p < 0.001, respectively) and video games (OR = 3.999; p = 0.049 and OR = 5.484; p < 0.001, respectively) compared to those who were not bullied. Furthermore, it was detected that schoolchildren perpetrators of cyberbullying had a significant risk of making unhealthy use of internet (OR = 5.782; p < 0.001), cell phone (OR = 14.367; p < 0.001) and video games (OR = 3.839; p < 0.001). This high probability of risk was confirmed in both boy and girl perpetrators with respect to non-perpetrators (all p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

The aim of the present study was to analyze the association of bullying and cyberbullying with the use of the Internet, cell phones, and video games in children and adolescents between 10 and 16 years of age. In general, the results showed that both victims and perpetrators of bullying and cyberbullying have higher percentages and a higher risk of abusive use of the Internet, cell phones, and video games than their unaffected peers. In all cases, girls, both victims and perpetrators of bullying and cyberbullying, multiply the risk of harmful use of the Internet, cell phones, and/or video games at least ×3. In both sexes, cyberbullying has a greater negative impact on the abusive use of the Internet, cell phones, and/or video games than traditional bullying. More specifically, the highest risk values are observed in perpetrator boys, who multiply the risk by up to 8.4, and victim girls, who multiply the risk by 16.5 times.

According to the results of this study, young people affected by bullying, both victims and perpetrators, abuse the Internet more (10.2% in both cases) than those who are not affected by bullying. In addition, inappropriate use of the Internet is more prevalent in girls who are victims and perpetrators of bullying (18.7% and 16.6%, respectively) than in boys. Similar results were found by (), who analyzed the relationship between bullying and cyberbullying and Internet and cell phone use in a sample of 3188 young people aged 12–17 years, as well as those found by (), who studied the effect of high levels of Internet use on mental well-being in 1140 students aged 12–18 years. Both studies concluded that both bullying and cyberbullying appear to be associated with abusive and problematic Internet use, as well as directly affecting the mental well-being of adolescents. Regarding gender, some studies have associated bullying and cyberbullying with problematic Internet use more in girls than in boys (; ). The present study also found that, although the results are significant in both boys and girls, the risks are higher in girls. For example, in bullying and cyberbullying perpetration, the risks amount to 8.07 and 14.33, respectively.

Furthermore, our results have also revealed that both victimization and perpetration, related to cyberbullying, have a higher negative impact (11.42% and 19.72%, respectively) and twice the risk of abusive Internet use than those affected only by traditional bullying. According to these findings, recent research suggests that cyberbullying has negative associations with respect to Internet use, not as clearly evident in traditional bullying (; ). However, some previous research also considers the use of the Internet as a cause of cyberbullying and not as a consequence (; ; ). It appears that cyberbullying, due to its pervasive and anonymous nature, may have a more profound impact than traditional bullying, due to the ease of access to the Internet that technologies provide and the association of Internet use with the search for emotional comfort or support on digital platforms (; ; ).

On the other hand, our results reveal that students who are victims of cyberbullying are up to four times more likely to abuse the use of cell phones. Several previous studies have also concluded that students who suffer bullying and cyberbullying have a higher inappropriate use of cell phones than those not involved in bullying situations (; ). According to our results, gender emerges as a differentiating factor since female victims have a higher risk (×2.9 for bullying and ×16.5 for cyberbullying) of inappropriate use of cell phones. These findings coincide with those obtained by (), who found that, in young people aged 12–17 years, girls affected by bullying or cyberbullying abuse cell phones to a greater extent than boys. It seems that girls, both victims and perpetrators, have a greater addiction to social networks than boys and therefore a greater dependence on the use of digital devices such as cell phones ().

Regarding the type of bullying, data have shown that the main associations with inappropriate use of video games are found in victims (15.2%) and perpetrators (20.7%) of cyberbullying. Previous studies have revealed that young people involved in cyberbullying are those who present a greater abuse of video games () or online games (). In terms of gender, we found a greater addiction to video games among girls who were victims of cyberbullying (27.54%) and perpetrators of bullying (23.19%) and cyberbullying (26.57%). However, other recent research has attributed greater use of video games among boys (; ; ) and even observed no differences by sex ().

Finally, another aspect that can generate controversy is the differentiating role between victims and perpetrators in the use of video games. In general, there seems to be a consensus that being a victim or perpetrator of bullying or cyberbullying affects screen time (; ; ). The data presented in this study reveal that the most negative associations of bullying and cyberbullying, towards the abusive use of video games, occur in perpetrators. These findings coincide with those of (), whose study, carried out on 3707 adolescents aged 12–19 years, showed that exposure to video games had a significant positive association with perpetration behaviors in bullying and cyberbullying. Therefore, exposure to video games would in turn be associated with a greater likelihood of perpetrating cyberbullying. Although the significant differences between victims and perpetrators are not always evident (; ), cyberbullying perpetrators appear to show the highest association with psychological problems linked to excessive video game use compared to victims ().

Limitations and Strengths

The study has limitations, such as the impossibility of establishing causality due to its cross-sectional design and the dependence on the sincerity of the participants’ responses, which could have been biased. In addition, convenience sampling limits its representativeness. However, the use of anonymity techniques, reliable and valid instruments, a rigorous collection process, and the inclusion of key covariates (age, BMI, maternal education level, and physical activity) are noteworthy, providing novel results in educational research. Finally, despite the above, and although valid and reliable instruments have been used for this study, the results should be interpreted with caution because the categorization of the participants was based on subjective criteria.

5. Conclusions

The present study concludes that, in general, both victims and perpetrators of bullying and cyberbullying show significantly higher values of inappropriate use of the Internet, cell phones, and video games than their classmates not affected by bullying behaviors. Girls involved in bullying/cyberbullying behaviors reach the highest percentages of inappropriate use of the Internet (≥10.36%), cell phones (≥29.25%), and video games (≥23.19%). In all cases, girls, both victims and perpetrators of bullying and cyberbullying, multiply the risk of harmful use of these devices by at least ×3. It was also found that the highest risk values were observed in cyberbullying behaviors, where the perpetrator boys multiply the risk by 8.4 times and victim girls by 16.5 times. Finally, in young people involved in bullying behaviors, excessive and inappropriate use of cell phones reached the highest values of association and risk among the devices analyzed.

Given this, victims and perpetrators of bullying and cyberbullying show harmful use of the Internet, cell phones, and video games, affecting girls more than boys, and perpetrators are particularly prone to high levels of technological abuse, with cyberbullying being an intensifying factor. It is recommended that strategies and policies be developed to prevent and address bullying and cyberbullying in the educational context by prioritizing student safety. Teachers should provide specialized counseling to the students involved, with an emphasis on girls. Likewise, families should take an active role in digital education, supervise the use of technologies, and work together with schools to ensure a protected educational environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R.-M. and E.J.M.-L.; methodology and formal analysis, J.E.M.-G. and A.R.-M.; data analysis, J.E.M.-G.; writing the original draft, J.E.M.-G., A.R.-M., F.A.P.-V. and E.J.M.-L.; review and editing, J.E.M.-G., A.R.-M., F.A.P.-V. and E.J.M.-L.; and supervision, J.E.M.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (grant number PID2022-137432OB-I00). Support was also received from the University Teacher Training Program, implemented by the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport of the Government of Spain [Reference: AP-2020-03217].

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Jaén (Spain) (protocol code: NOV.22/2.PRY approved on 13 January 2023) for studies involving human subjects. Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects and their guardians involved in this study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy of the participants.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants and centers involved in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the existing affiliation information. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

References

- Ak, Ş., Özdemir, Y., & Sağkal, A. S. (2022). Understanding the mediating role of moral disengagement in the association between violent video game playing and bullying/cyberbullying perpetration. Contemporary School Psychology, 26(3), 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Turif, G. A. R., & Al-Sanad, H. A. R. (2023). The repercussions of digital bullying on social media users. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1280757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anbumalar, C., & Binu Sahayam, D. (2024). Brain and smartphone addiction: A systematic review. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2024, 5592994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arul-Prasath, V., Perumal, B. M., & Samuel, S. G. (2022). Prevalence, underlying factors and consequences of mobile game addiction in school going children of six to twelve years in Kanyakumari district. International Journal of Contemporary Pediatrics, 9(4), 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, V., Piccoliori, G., Engl, A., & Wiedermann, C. J. (2024). Impact of digital media, school problems, and lifestyle factors on youth psychosomatic health: A cross-sectional survey. Children, 11(7), 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlett, C. P., Bennardi, C., Williams, S., & Zlupko, T. (2021). Theoretically predicting cyberbullying perpetration in youth with the BGCM: Unique challenges and promising research opportunities. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 708277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinka, L., Stašek, A., Šablatúrová, N., Ševčíková, A., & Husarova, D. (2023). Adolescents’ problematic internet and smartphone use in (cyber)bullying experiences: A network analysis. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 28(1), 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourou, A., & Papageorgiou, E. (2023). Prevalence of aggressive behavior in greek elementary school settings from teachers’ perspectives. Behavioral Sciences, 13(5), 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagirkan, B., & Bilek, G. (2021). Cyberbullying among Turkish high school students. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 62(4), 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M. A., & Camilleri, A. C. (2020). The students’ readiness to engage with mobile learning apps. Interactive Technology and Smart Education, 17(1), 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, P., Monasso, G. S., Karhunen, V., Ronkainen, J., Mancano, G., Howe, C. G., Niu, Z., Zeng, X., Guan, W., Dou, J., Feinberg, J. I., Mordaunt, C., Pesce, G., Baïz, N., Alfano, R., Martens, D. S., Wang, C., Isaevska, E., Keikkala, E., … Sebert, S. (2024). Maternal educational attainment in pregnancy and epigenome-wide DNA methylation changes in the offspring from birth until adolescence. Molecular Psychiatry, 29(2), 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chun, J. W., Choi, J., Cho, H., Choi, M. R., Ahn, K. J., Choi, J. S., & Kim, D. J. (2018). Role of frontostriatal connectivity in adolescents with excessive smartphone use. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciacchini, R., Orrù, G., Cucurnia, E., Sabbatini, S., Scafuto, F., Lazzarelli, A., Miccoli, M., Gemignani, A., & Conversano, C. (2023). Social media in adolescents: A retrospective correlational study on addiction. Children, 10(2), 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, F., Tenuta, F., De Giacomo, A., Trabacca, A., & Costabile, A. (2021). A systematic review of problematic video-game use in people with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 82, 101726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, W., Boniel-Nissim, M., King, N., Walsh, S. D., Boer, M., Donnelly, P. D., Harel-Fisch, Y., Malinowska-Cieślik, M., Gaspar de Matos, M., Cosma, A., Van den Eijnden, R., Vieno, A., Elgar, F. J., Molcho, M., Bjereld, Y., & Pickett, W. (2020). Social media use and cyber-bullying: A cross-national analysis of young people in 42 countries. Journal of Adolescent Health, 66(6), S100–S108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rey, R., Casas, J. A., Ortega-Ruiz, R., Schultze-Krumbholz, A., Scheithauer, H., Smith, P., Thompson, F., Barkoukis, V., Tsorbatzoudis, H., Brighi, A., Guarini, A., Pyzalski, J., & Plichta, P. (2015). Structural validation and cross-cultural robustness of the European Cyberbullying Intervention Project Questionnaire. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, H. N., Onyango, B., Prakash, R., Tran, B. X., Nguyen, Q. N., Nguyen, L. H., Nguyen, H. Q. T., Nguyen, A. T., Nguyen, H. D., Bui, T. P., Vu, T. B. T., Le, K. T., Nguyen, D. T., Dang, A. K., Nguyen, N. B., Latkin, C. A., Ho, C. S. H., & Ho, R. C. M. (2020). Susceptibility and perceptions of excessive internet use impact on health among Vietnamese youths. Addictive Behaviors, 101, 105898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabio, R. A., Stracuzzi, A., & Lo Faro, R. (2022). Problematic smartphone use leads to behavioral and cognitive self-control deficits. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(12), 7445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feijóo, S., Foody, M., Norman, J. O., Pichel, R., & Rial, A. (2021). Cyberbullies, the cyberbullied, and problematic internet use: Some reasonable similarities. Psicothema, 33(2), 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S. (2022). The detrimental effects of mobile game addiction on Chinese primary school students and possible interventions. Science Insights Education Frontiers, 13(2), 1911–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festl, R., & Quandt, T. (2016). The role of online communication in long-term cyberbullying involvement among girls and boys. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(9), 1931–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foerster, M., Henneke, A., Chetty-Mhlanga, S., & Röösli, M. (2019). Impact of adolescents’ screen time and nocturnal mobile phone-related awakenings on sleep and general health symptoms: A prospective cohort study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(3), 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisén, A., & Berne, S. (2020). Swedish adolescents’ experiences of cybervictimization and body-related concerns. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 61(1), 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J., Wang, X., Wang, Y., Lei, L., & Wang, P. (2022). “If you love me, you must do.” Parental psychological control and cyberbullying perpetration among Chinese adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(9–10), NP7932–NP7957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gmmash, A., Alonazi, A., Almaddah, M., Alkhateeb, A., Sabir, O., & Alqabbani, S. (2023). Influence of an 8-week exercise program on physical, emotional, and mental health in saudi adolescents: A pilot study. Medicina, 59(5), 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohal, G., Alqassim, A., Eltyeb, E., Rayyani, A., Hakami, B., Al Faqih, A., Hakami, A., Qadri, A., & Mahfouz, M. (2023). Prevalence and related risks of cyberbullying and its effects on adolescent. BMC Psychiatry, 23(1), 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadlington, L. J. (2015). Cognitive failures in daily life: Exploring the link with Internet addiction and problematic mobile phone use. Computers in Human Behavior, 51, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C. Y., Rutherford, R., Chang, H., Chang, F. C., Shumei, L., Chiu, C. H., Chen, P. H., Chiang, J. T., Miao, N. F., Chuang, H. Y., & Tseng, C. C. (2022). Children’s mobile-gaming preferences, online risks, and mental health. PLoS ONE, 17, e0278290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J., Zhong, Z., Zhang, H., & Li, L. (2021). Cyberbullying in social media and online games among chinese college students and its associated factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iñiguez-Berrozpe, T., Orejudo-Hernández, S., Ruiz-Eugenio, L., & Elboj-Saso, C. (2021). School networks of positive relationships, attitudes against violence, and prevention of relational bullying in victim, bystander, and aggressor agents. Journal of School Violence, 20(2), 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, S. J., Quer, G., Galarnyk, M., Steinhubl, S. R., Topol, E. J., & Owens, R. L. (2020). Association of sleep duration and variability with body mass index: Sleep measurements in a large US population of wearable sensor users. JAMA Internal Medicine, 180(2), 1694–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, M. R., van der Wel, K. A., & Bråthen, M. (2023). Adolescent mental health disorders and upper secondary school completion–The role of family resources. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 67(1), 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y., Burns, R. D., Lee, D. C., & Welk, G. J. (2021). Associations of movement behaviors and body mass index: Comparison between a report-based and monitor-based method using Compositional Data Analysis. International Journal of Obesity, 45(1), 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkbride, J. B., Anglin, D. M., Colman, I., Dykxhoorn, J., Jones, P. B., Patalay, P., Pitman, A., Soneson, E., Steare, T., Wright, T., & Griffiths, S. L. (2024). The social determinants of mental health and disorder: Evidence, prevention and recommendations. World Psychiatry, 23, 58–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobel, S., Wartha, O., Amberger, J., Dreyhaupt, J., Feather, K. E., & M Steinacker, J. (2022). Is adherence to physical activity and screen media guidelines associated with a reduced risk of sick days among primary school children? Journal of Pediatrics, Perinatology and Child Health, 6(3), 401–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotozaki, Y., Chen, C., Gan, X., Jin, X., K-n, Q., G-x, X., Qin, K.-N., & Xiang, G.-X. (2023). The relationship between parental neglect and cyberbullying perpetration among Chinese adolescent: The sequential role of cyberbullying victimization and internet gaming disorder. Frontiers in public health, 11, 1128123. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, M., Lee, J. Y., Won, W. Y., Park, J. W., Min, J. A., Hahn, C., Gu, X., Choi, J. H., & Kim, D. J. (2013). Development and validation of a smartphone addiction scale (SAS). PLoS ONE, 8(2), e56936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesinskienė, S., Šambaras, R., Butvilaitė, A., Andruškevič, J., Kubilevičiūtė, M., Stanelytė, U., Skabeikaitė, S., Jūraitytė, I., Ridzvanavičiūtė, I., Pociūtė, K., & Istomina, N. (2024). Lifestyle habits related to internet use in adolescents: Relationships between wellness, happiness, and mental health. Children, 11(6), 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Wu, Y., & Hesketh, T. (2023). Internet use and cyberbullying: Impacts on psychosocial and psychosomatic wellbeing among Chinese adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 138, 107461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L., Chen, X., & Li, H. (2020). Bullying victimization, school belonging, academic engagement and achievement in adolescents in rural China: A serial mediation model. Children and Youth Services Review, 113, 104946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Blasco, R., Quilez-Robres, A., Rodriguez-Araya, R., & Casanovas-López, R. (2022). Addiction to new technologies and cyberbullying in the costa rican context. Education Sciences, 12(12), 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-López, E. J., de la Torre-Cruz, M., Suárez-Manzano, S., & Ruiz-Ariza, A. (2017). Analysis of the effect size of overweight in muscular strength test among adolescents: Reference values according to sex, age and body mass index. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 32(5), 1401–1414. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez, I., Jorquera Hernández, A. B., & Ruiz-Esteban, C. (2020). Profiles of mobile phone problem use in bullying and cyberbullying among adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 596961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirza, M. (2020). A comparative study of cyber bullying among online and conventional students of higher education institutions in Pakistan. Journal of Educational Sicences & Research, 7(2), 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Moller, A. C., Sousa, C. V., Lee, K. J., Alon, D., & Lu, A. S. (2023). A comprehensive systematic review and content analysis of active video game intervention research. Digital Health, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumford, E. A., Maitra, P., Rothman, E. F., & Sheridan-Johnson, J. (2023). The victim-offender overlap in technology-facilitated abuse: Nationally representative findings among U.S. young adults. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 26(12), 904–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nain, A., Bohra, N. S., Bansal, M., Narang, M., & Scholar, R. (2023). Persistent bullying in higher education institutions: A comprehensive research study. Tuijin Jishu/Journal of Propulsion Technology, 44(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasti, C., Sangiuliano Intra, F., Palmiero, M., & Brighi, A. (2023). The relationship between personality and bullying among primary school children: The mediation role of trait emotion intelligence and empathy. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 23(2), 100359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, A. B. (2019). Preventing and Intervening with Bullying in Schools: A Framework for Evidence-Based Practice. School Mental Health, 11(1), 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Ruiz, R., Del Rey, R., & Casas, J. A. (2016). Evaluar el bullying y el cyberbullying validación española del EBIP-Q y del ECIP-Q. Psicologia Educativa, 22(1), 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons-Salvador, G., Zubieta-Méndez, X., & Frias-Navarro, D. (2022). Parents’ digital competence in guiding and supervising young children’s use of the Internet. European Journal of Communication, 37(4), 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontes, H. M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2015). Measuring DSM-5 internet gaming disorder: Development and validation of a short psychometric scale. Computers in Human Behavior, 45, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J. J., Sallis, J. F., & Long, B. (2001). A physical activity screening measure for use with adolescents in primary care. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 155(5), 554–559. [Google Scholar]

- Puolitaival, T., Sieppi, M., Pyky, R., Enwald, H., Korpelainen, R., & Nurkkala, M. (2020). Health behaviours associated with video gaming in adolescent men: A cross-sectional population-based MOPO study. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radesky, J. S., Weeks, H. M., Ball, R., Schaller, A., Yeo, S., Durnez, J., Tamayo-Rios, M., Epstein, M., Kirkorian, H., Coyne, S., & Barr, R. (2020). Young Children’s use of smartphones and tablets. Pediatrics, 146(1), e20193518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, J., Marchica, L., Ivoska, W., & Derevensky, J. (2021). Bullying victimization and problem video gaming: The mediating role of externalizing and internalizing problems. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riffle, L. N., Kelly, K. M., Demaray, M. L., Malecki, C. E., Santuzzi, A. M., Rodriguez-Harris, D. S. J., & Emmons, J. D. (2021). Associations among bullying role behaviors and academic performance over the course of an academic year for boys and girls. Journal of School Psychology, 86, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano, Á., Sanz, R., Cabanillas, J. L., & López-Lujan, E. (2023). Socio-emotional competencies required by school counsellors to manage disruptive behaviours in secondary schools. Children, 10(2), 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, W., & Kim, H. W. (2023). Problematic mobile phone use and cyberbullying perpetration in adolescents. Behaviour and Information Technology, 42(4), 424–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simion, I. (2023). Bullying in school a real problem for teacher-students-parent. Euromentor Jorunal-Studies About Education, 14(2), 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Sittichai, R., & Smith, P. K. (2020). Information technology use and cyberbullying behavior in South Thailand: A test of the goldilocks hypothesis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(19), 7122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slonje, R., Smith, P. K., & Frisén, A. (2013). The nature of cyberbullying, and strategies for prevention. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(1), 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P. K., & Berkkun, F. (2017). How research on cyberbullying has developed. In Bullying and Cyberbullying: Prevalence, Psychological Impacts and Intervention Strategies (pp. 11–27). ACAMH. ISBN 978-1-53610-064-8. [Google Scholar]

- Soto-García, O., Sainz, V., Maldonado, A., & Calmaestra, J. (2024). The TEI program for peer tutoring and the prevention of bullying: Its influence on social skills and empathy among secondary school students. Social Sciences, 13(1), 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Z., Nie, Q., Zhu, Z., & Guo, C. (2020). Violent video game exposure and (Cyber)bullying perpetration among Chinese youth: The moderating role of trait aggression and moral identity. Computers in Human Behavior, 104, 106193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trisano, S. O., Cortez-Vergara, C., & Vega-Dienstmaier, J. M. (2022). Validación psicométrica de la traducción al español del cuestionario original sobre el uso problemático de internet en jóvenes estudiantes de primer ciclo de una universidad privada de Lima Metropolitana. Persona, 25(1), 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsaousis, I. (2016). The relationship of self-esteem to bullying perpetration and peer victimization among schoolchildren and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 31, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uludasdemir, D., & Kucuk, S. (2019). Cyber bullying experiences of adolescents and parental awareness: Turkish example. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 44, e84–e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unni, V., & Prasanna Kumar, N. (2023). A study of sleep quality in adolescents: The impact of over use of mobile cell phone in urban setting: A cross sectional study. International Journal of Scientific Research, 12(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacks, Y., & Weinstein, A. M. (2021). Excessive smartphone use is associated with health problems in adolescents and young adults. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 669042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T., Tomokawa, Gregorio, R., Mannava, P., Nagai, M., & Sobel, H. (2020). School-based interventions to promote adolescent health: A systematic review in low- and middle-income countries of WHO western pacific region. PLoS ONE, 15(3), e0230046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Zhang, Z., Liu, J., & Cao, H. (2023). Interactive effects of sleep and physical activity on depression among rural university students in China. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1240856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Q., Zhou, R., Huang, Y. N., Chen, H. W., Liu, H. M., Huang, Z., Yuan, Z., Wu, K., Cao, B. F., Liu, K., Fan, W. D., Liang, Y. Q., & Wu, X. B. (2023). The independent and joint association of accelerometer-measured physical activity and sedentary time with dementia: A cohort study in the UK Biobank. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 20(1), 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zsila, Á., Urbán, R., Griffiths, M. D., & Demetrovics, Z. (2019). Gender differences in the association between cyberbullying victimization and perpetration: The role of anger rumination and traditional bullying experiences. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17(5), 1252–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).