Abstract

In order to attain high manufacturing productivity, industry 4.0 merges all the available system and environment data that can empower the enabled-intelligent techniques. The use of data provokes the manufacturing self-awareness, reconfiguring the traditional manufacturing challenges. The current piece of research renders attention to new consideration in the Job Shop Scheduling (JSSP) based problems as a case study. In that field, a great number of previous research papers provided optimization solutions for JSSP, relying on heuristics based algorithms. The current study investigates the main elements of such algorithms to provide a concise anatomy and a review on the previous research papers. Going through the study, a new optimization scope is introduced relying on additional available data of a machine, by which the Flexible Job-Shop Scheduling Problem (FJSP) is converted to a dynamic machine state assignation problem. Deploying two-stages, the study utilizes a combination of discrete Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and a selection based algorithm followed by a modified local search algorithm to attain an optimized case solution. The selection based algorithm is imported to beat the ever-growing randomness combined with the increasing number of data-types.

1. Introduction

Industry 4.0 (I4.0) has accustomed manufacturing to the digital age via Cyber Physical Systems (CPS) and Digital Twins (DTs). CPS and DTs are two integrated approaches of several intelligent tools that facilitate the use of data-driven approach in industry. A system can have the ability to physically interact the environment and collect data to virtually represent a complete description along system states progress. Such description causes a state of awareness or smartness that empowers smart manufacturers to take the place of conventional manufacturers [1]. Accordingly, the progress of sensor devices, communication technologies and enabling intelligent techniques have evolved for the sake of big data analytics [2]. Enabling techniques have been used in industry for more than three decades. However, what makes a difference is the perspective of data that empowers the intelligent techniques [3]. In a dynamic collaboration, CPS allow information communication between systems/sub-systems aspects, where the real physical phase and cyber phase are associated to fulfill the system awareness gap through data analysis [4,5]. While, DTs support integration between the dual states of data: static state and dynamic state. Data states are beneficial in creating a virtual model or emphasizing interdependent instances of included sub-systems, approaching a model-based system [6,7]. Briefly, both the CPS and DTs are employed to achieve cyber-physical pervasive integration [5].

The motive behind the three previous industries is still applied in I4.0 but is influenced by sustainability and adaptability. Sustainability is a requirement for the future, being one of the pillars that accompanies value added activities [8,9]. The latter term, adaptability, is accomplished through three self-functionalities: self-configuration, self-organization and self-maintenance [3]. The system exploits the available data to achieve the parameters of self-configuration and self-organization. While, system life-cycle data can be operated to address self-maintenance. The three terms target higher levels of automation compatibilities, approaching what is meant by awareness which enables the progress in the new manufacturing era.

The research topics in smart manufacturing are being pinpointed recently by academics in a number of review papers [10,11], declaring the new horizon of challenges. As expected, the challenges are conventional manufacturing challenges in real-time. Such instances result in a complex dynamic-oriented challenge. Accordingly, the solution seeks optimization from a comprehensive view in respect to the interdependent data between the subs. The main contributions of this piece of research can be concluded as follows:

- Regarding that, a projected literature review on a number of highlighted research studies are demonstrated (Section 4).

- A new perspective of FJSSP is outlined and tackled through a case study (Section 5).

- A proposed two stages approach is designed considering improved steps to enhance the neighborhoods shaking search (Section 6).

- Finally, the results and conclusion are present in Section 7, followed by the future discussion.

2. JSSP Evolution

In manufacturing systems, shop scheduling problems are initiated as a resources organization problem of a single or multiple identical machine(s) processing identical jobs of the same route. The problem was evolved quickly through the last decades to be a root of several distinct problems, differing in formation and complexity [12]. Three research problems have appeared the most often. The first is the Job Shop Scheduling Problem (JSSP), wherein each job follows its own predetermined route. Second, in a more general forum, the Flexible Job Shop Scheduling Problem (FJSP) discusses the alternative routes and assigned machines of each job to follow. Till that point, all studies focus on that field as a static approach. Third, the Dynamic Job Shop Scheduling Problem (DJSP) brings JSSP to real-time, in order to handle the disruptive events that happen in manufacturing, such as the arrival of new jobs and machines breaking down. Nevertheless, researchers during the recent decade urged that process planning and scheduling are two dependent processes that should be considered as a linked one [13,14,15,16]. In process planning, the machining process, tools and related configuration parameters are selected. The advances in CAD/CAM field has designed files that contain viable data for the scheduling problems [17]. The integration of the two processes is known as Integrated Process Planning and Scheduling (IPPS).

General speaking, JSSP related problems are crucial from more than one aspect and can stop the wasting of resources of a manufacturer. The new paradigm of manufacturing leverages technical devices to boost data that empowers knowledge of multiple aspects of a problem [18,19]. In such cases, future manufacturers will be able to adopt participating parts as an object-oriented entity that are completely describing the entity state. Regarding machines as an example, the enclosed life-time information is capable of drawing a detailed picture of the machining efficiency [20], the wearing that has occurred, and the expected maintenance time, etc. Such information paves the way for energy saving and predictive maintenance to be included in scheduling optimization considerations. Applying that upon a decision-making based problems [21], scheduling can be now considered as a multiple dynamic layers of optimization.

The JSSP complexity level is upgraded in conformity with variable insertion. In other words, FJSP and DJSP have higher complexity than the JSSP, following that sequence, additional integrations further increase the decision complexity, and hereafter, the cost of optimization increased.

3. Heuristics

Heuristics based algorithms are utilized heavily to find a solution for the JSSP based problems. In varied research topics, several heuristics and meta-heuristics taxonomies have been introduced for optimization an algorithms family [22,23,24,25,26,27], however, most of those taxonomies are influenced by relatively old anatomy. As an actively updated field, the recent years hold new discoveries in optimization techniques paired with a synchronous implementation in application based approaches. Hence, herein we produce a reshaped classification considering JSSP related spots respective to the inspired techniques, as in Table 1.

Table 1.

Meta-heuristics observed taxonomy.

3.1. Heuristics

Classical heuristic algorithms can be briefly interpreted as an algorithm initiated by a suggested solution, chasing an optimal solution or near optimal through an iterative process of sharing information. The algorithm can be executed in parallel mode in order to expedite the running process, and disclose the search space, as well [28,29]. Parallel mode distils the considered problem into smaller sub-problems of the same scheme, causing diverse scenarios of pointed solutions. This heterogeneous enlarges the ability to discover the search space [30].

Discovering the solution is a process of intensifying and diversifying the search space, where the algorithm manipulates the data to generate a solution over number of iterations in one of two forms. A population form lists several suggested solutions as a pool of solutions upgraded from parents’ generation to a children’s generation. A single solution form discovers the neighbors of a given initial solution. The rapid upgrade of Computing Processing Units (CPU) and Graphic Processing Units (GPU), plus the need for more hands to analyses data, attract both the evolutionary- and the mathematical model-based algorithms [31,32]. Hereby, both algorithms are capable of sharing information within multiple levels; the straightforward level as in mono-pool execution, and the plane level between the sub-populations—recognized as migration. Several topologies draw traces for the migration process such as: chain topology, ring topology, tours topology, etc., [33].

3.2. Common Components of Heuristic Based Algorithms

Being either population based or neighborhoods/single based, the study begins with a potential representation of individual(s) coded as genes. Multiple genes ensemble the assigned problem solution—known as chromosome or individual Thus, the first step is to introduce the code process.

3.2.1. Problem Encoding and Decoding

Encoding encrypts the concerned information of a problem in a handler format directly or indirectly, wherein the imported analyses model/method effectively able to operate it. In heuristic based, it is the process of representing the suggested solution of the performed problem as a chromosome of genes. The chromosome intra structure acclaimed as trees/graph, arrays/strings, lists, or any other objects. The inter representation, the gene, is coded as an element of binary or decimal numbers or in any other suitable representation. At this end, JSSP and its relatives concern arrays/strings and directed graph encoding, composed of bits, numbers, or rather values [22,34,35,36].

In that respect, permutation encoding adopts a string of real numbers in sequence. Hence, permutation encoding is preferable in problems having violent ordering or precedence constraint(s). Instead of numbers, value encoding approves values in a suitable form regarding the represented problem.

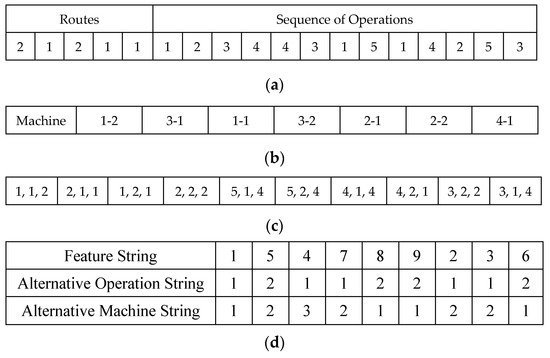

As a still growing problem, job scheduling based problems have brought viable derivatives of the aforementioned encoding forms. Therefore, the performance of the implemented algorithm depends to a great extent on the encoding strategy. Job, operation and machine information, three terms mainly govern the FJSSP, but the FJSSP is not limited to them. Thus, researchers tried to represent the individual as a single string of tuples, of three or more elements accordingly. Others have carried double and triple strings for each. The presence of information may be found as an indication, for case of explanation, operation cell could refer to the used strategy of performed path not the operation itself. Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 represent varied examples of the chromosomes constructions.

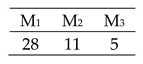

Figure 1.

The Acyclic Directed Graph (DAG) depicts the precedence operations of two jobs, where O1,1, O1,2 and O1,3 represent job 1 operations and O2,1, O2,2 and O2,3 represent job 2 operations. O1,3 and O2,3 processed in combination, the corresponding setup time present as an edge number [37].

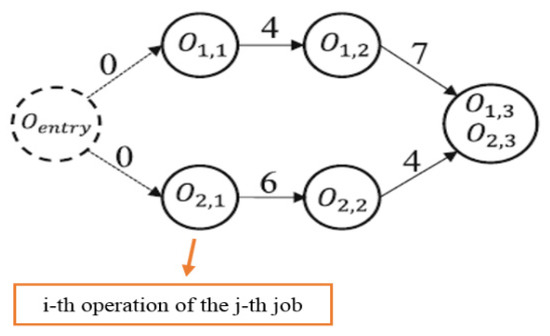

Figure 2.

Disjunctive graph of three jobs: the nodes contain the processing machine, the conjunctive arc connects consecutive operations, Φi is a dummy node associated to the ith job completion time. Another disjunctive graph of the operation is created in pair with the machine graph [38].

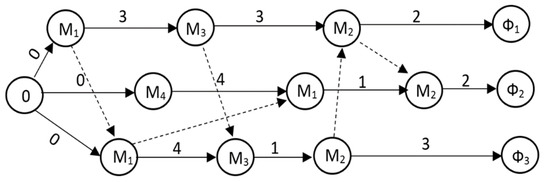

Figure 3.

Examples of chromosome coding: (a) chromosome is a bi-part coding multiple routes of a job indexation and the corresponding operation sequence [39], (b) chromosome is a machine coded of job-operation number as a tuple, (c) chromosome cell is a triple tuple of job-operation-machine coding [40], and (d) three chromosomes of a single cell information represents job as a feature string followed by operation and machine strategy indexation.

3.2.2. Mating Procedures

In a more general construction, population based algorithms are rather a discrete nature or a continuous nature. As the JSSP approach is a discrete field, applying discrete heuristic based algorithms in such an approach is a forthright process. The process observes the evolution of chromosomes through a crossover and mutation procedures. Wherein, the evolution mostly follows a pattern of two-to-two mating that is two individuals—parents—produce corresponding two updated individuals—children—e.g., GA.

In different circumstances, continuous algorithms evolve, relying on adjustment of a point in a continuous solution space. Continuous based algorithms dominate the optimization race, since they achieve better results than the discrete based algorithms [41]. To make use of continues based algorithms in discrete approaches several suggestions have been contributed. The premise behind most of these suggestions is to project continuous variable parameters as a logical or a crossover method [17,42]. Through that, the related evolution pattern appeared as a multiple-to-one pattern, mostly two-to-one.

- a.

- Crossover Procedure

In discrete space, crossover operation mimics the natural chromosomes mating process, aiming to recombine parents’ genes, in order to produce new chromosome(s). Crossover is the main engine that defines how children inherit genes from their parents, since crossover manipulates the genes and in turn the genes representation directs the used crossover method. As discussed previously, an array of indexes coding is frequently used, thus, correspondingly array based crossover forming the main cluster [43]. Additionally, it is worth mentioning that the number of individuals resulting from the crossover process varied depending on the way the evolution based algorithm implements the mating procedure.

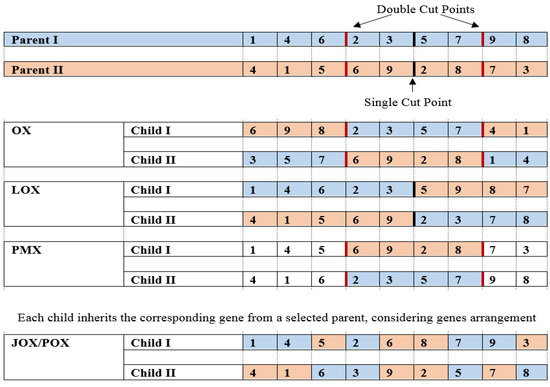

Earlier discussions in crossover partitioned a single parent array of genes around a cut-point, creating two shortened arrays—sub-arrays. With parent I and parent II, either part of parent I, the sub-array attached to the opposite part of parent II sub-array generates a chromosome. The procedure is known as Single Point crossover (SPX). SPX expanded to Double cut-points crossover (DPX), and also multiple points—known as uniform crossover. In a wider scope, if it is a two-to-two mating process, the second chromosome will be generated by merging the unused complementary parts in the same positioned order. The inherited parts are similarly traversed in an opposite complementary manner. In the case of determining specified genes permutations, repeated genes appear while others are absence. For the sake of solution feasibility, Choi et al. [44] exchanged only a sub-array and rearrange the missing genes regarding to the opposite sub-array. The arrangement order derived additional types of crossovers, known as Ordered crossover (OX), Linear Ordered crossover (LOX), and Partially Mapped crossover (PMX) [43,45]. Besides, the generalized form of OX and PMX that taken into count permutation repetition demands had acronyms of GOX and GPMX respectively [46].

Selecting the crossover point(s) is where most of new trends in crossover studies have evolved. The simplest way is to select point(s) randomly. Recently, in a crossover sub-scale, methods such as local search neighborhood, distributed mathematical models mostly as a filter/mask and evolution based strategies have emerged to determine the selected cut-points. As a particular case, in FJSP wherein multiple combined-chromosomes represented a job-operation-machine, Xinyu et al. [47] presented two crossovers, which exhibits multiple points as masked points applied to the job chromosome and operation strategy chromosome shorted as JOX and POX, respectively. Figure 4 depicts some of the frequently mentioned strategies.

Figure 4.

Frequently used crossover strategies based in JSSP.

- b.

- Mutation Procedure

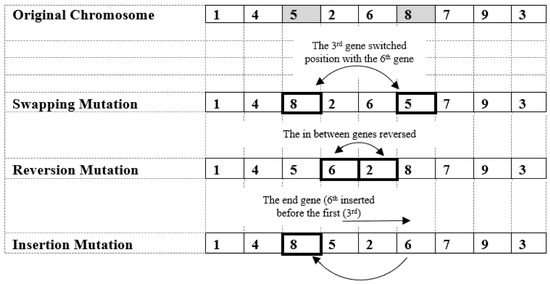

Mutation is a unary evolutionary operator that has a tendency to manipulate a single individual functioning in a probability factor to produce another version of it. Mutation diversifies the search space. The search space type and gene probability evoke varied types of mutation methods [48]. In discrete space, especially in a JSSP based instance, mutation is best represented as swapping operator, reversion operator and insertion operator, pictured in Figure 5. There is also, a fragment mutation, where the child inherits the exact gene(s) from a specified parent. Similar to the crossover operator, mutated genes/points are frequently selected randomly. Recently, uniform random mutation and normally distributed mutation have prevailed, as well as heuristics based in mutation sub-scales [34].

Figure 5.

Famous mutation strategies.

- c.

- Selection Procedure

Selection is a priority engine that defines the chance of a solution to be recommended over others regarding to the occupied strategy. The selected strategy defines a weight that supports the solution probability to be selected. To the best of our knowledge, there is no concise explanation supports a strategy over another in JSSP based fields. However, some strategies are utilized on a large scale through the population generating mechanism. Tournament selection strategy, a prescribed number of solutions are randomly selected and the fittest represented as a winner of a race. In tournament, a weight is responsible for the times the procedure implemented. Displaying a trade-off between intensification and diversification, Roulette Wheel Selection (RWS) yields a weight proportional to the relative fitness of a solution. Thus, as a role of thumb, the higher the fitness, the higher the probability of a solution to be picked. Rank Based Selection (RBS) normalizes the RWS, producing a weight corresponds to the solution rank [43].

- d.

- Objective Function

A fitness function is used to evaluate the quality of a chromosome, also known as objective function. The comprehensive perspective of optimization problems disclose interdependency among diverse elements, either as a configuration set or a consequence results. In other words, multiple conflicts, wherein enhancing the objective of one aspect affects another, a manner that may be a cycle of deterioration in total. Such an instance—which is almost everywhere in real-world—triggers a multi-objective optimization algorithm. Multi-objective optimization is mainly discussed as: aggregation selection, criterion selection and Pareto selection.

Aggregation selection presses linearly a multi-objective case to a mono-objective. For that purpose, the multi-objectives is aggregated as a penalty cost in terms of weight, constraint, or as a goal with a priority, depending on the studied circumstance. Aggregation based is commonly functioned in large number of evolutionary based studies in both general perspectives and JSSP related perspectives. Criterion based methods paid attention to the fitness function one at a time. Late studies focused on Pareto selection based, wherein a representative set deploying a relation based dominance [49,50], as depicted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Literature survey.

A typical JSSP based instance mostly uses make-span/completion time, labor cost and total profit as optimized targets. A few studies have paid marginal attention to dynamic JSSP throughout new job arrival cases. With the big data tool and industry 4.0 concepts, the JSSP objective is extended to cope with higher levels of real-time factors and resources enriched manufacture consensus. Energy sustainability directs the evaluation to attain machine-energy consumption. Material resources, predictive maintenance and workload, however, they are not common along the new trends studies, they present a salient and viable analysis tool.

4. Literature Review

Several studies have been introduced in JSSP fields. Notable here are the recent studies introduced in Table 2, as they show premises scopes and higher information manipulation that serve smart manufacturing best. The table introduces those studies respecting to the previous discussed elements for better comprehensive view. The review mostly focuses on the recent years to avoid redundant information and to be more integrated and process planning oriented.

5. Case Study Formulation

For flexibility terms, there are a large number of research papers in that field, however, a lot of them suffer from limited flexibility dimensions [15], as they ignore alternative machine/operation strategies [47], or rather discuss flexibility from a single machine point of view. A number of them do not examine precedence constraints. The studies are conflicted between suboptimal and optimal problems [83], where limited information about the environment or the time life cycle were eliminated. Furthermore, expanding the problem to adopt more information (i.e., inserted tool information, features location, machining speed, etc.) reflects upon the structure of the chromosomes, and hence the searching space. The more the available data types are increased the more the chromosomes total numbers—in vertical structural chromosomes or length in horizontal designed chromosomes—increased. As a consequence, the randomness exploration progressed between generations may result as exhausted diversification steps of the increased number of chromosomes.

The current case study is going to tackle the JSSP based problem as a FJSP problem with dynamic term that is being submitted as machine-tool state. In that, a path based assignation strategy is designed to explore the searching space with less randomness. The new perspective of the problem formulation is designed as the discussed following points:

- (1)

- Each work-piece has its job that is independent from others.

- (2)

- Each machine within the cell can process a single job per time, and each machining concurrent time slot can only has a job once.

- (3)

- No job pre-emption present.

- (4)

- A machine availability is governed by its efficiency.

- (5)

- An operation may be performed by multiple machines.

- (6)

- Processing a job along machines takes into count the transmission time, no immediate processing.

- (7)

- Tool insertion setup time is considered.

- (8)

- Supporting flexibility, alternative strategies for machining present in more than a level: feature level, process level and machine level.

- (9)

- Precedence constraints are considered during feature-operation level or operation machine level.

Depending on the aforementioned, this study urges that, no matter the number of variables to be considered during the machining process, the complexity of the new perspectives can be transferred to computational levels only. Meaning that, the valid suggested solutions through optimization levels are better differentiated and may lead to a specified solution, wherein, the data can be handled to a realistic optimized solution.

6. The Proposed Algorithm

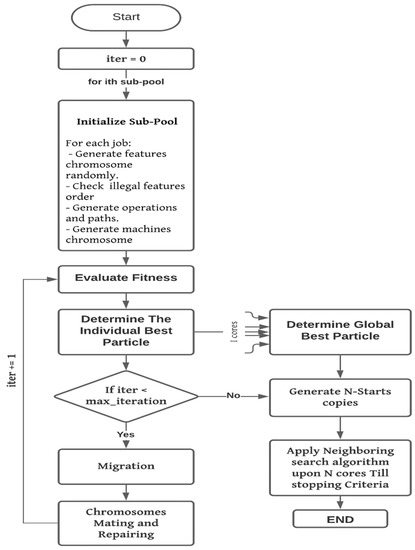

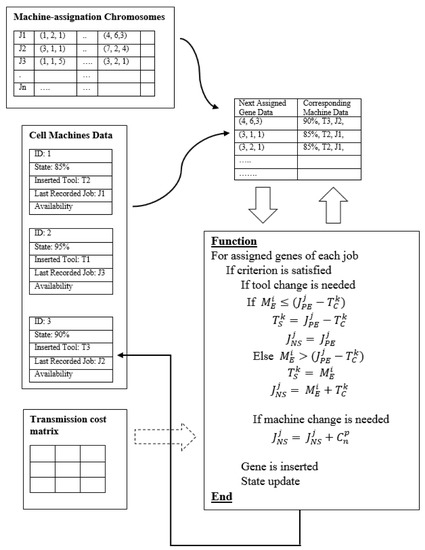

Now, since the potential elements are identified, the modification on that elements can be introduced through the proposed method. This study tackles the problem in two sequential stages. The first stage is capable of producing earlier proper valid chromosomes that can be the near enough to the optimal solution. The second stage is where a neighbor search checks the near optimal solution, targeting the optimal individual. The two stages have a dual beneficial influence, the first stage enhances the quality of the second stage initial solution, where the second ensures escaping from a local optima, if the first step result stuck in it. The following steps are applied in compatible sequence with the flow chart indicated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The proposed algorithm.

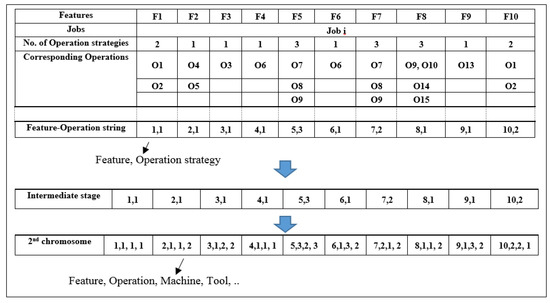

6.1. Coding Steps

The objective of this step is to represent the features, operations and assigned machines of the cell jobs as geno-types (machines encoded sequence). This piece of research adopts two strings upon two-steps, dealing with multiple alternative levels. A single gene of the first string codes a tuple of a selected feature paired with the assigned operation strategy, as shown in Figure 7. The second is a selection operation that produces an operation-machine that can accept any additional inserted data, i.e., tool, etc., the string refers to machine path. For either string, the position of each gene refers to the execution order. The occurrence pairs the feature-operation and machining data as a path enable feature-operation precedence check as an intra-check, and machines precedence check as inner-check.

Figure 7.

Coding procedure.

6.2. Path Creation Phase

Machining an operation on the ith machine requires additional data, such as inserted tool or feature position, which makes a list of collocations to choose between. Each collocation in that list is a machining path to be considered. A designed function is created to select a machining path, structured on a modified roulette-wheel selection. The roulette-wheel suffers from ignoring less occurred probability that may diminish appearance of available solutions over generation, and thus affects diversification. Therefore, the wheel gained score built on exponential mapping, as following:

Such that a single path probability increases exponentially respecting to the total number of feasible paths scored on the ith machine over a single path. Considering only a tool as additional data, a single presented as:

And,

For a job, is the machine transmission cost between the ith machine and the previous recorded machine, is the tool changing cost, is the duration cost regarding machine efficiency , and is the ideal operation machining duration. Setup configuration duration can be added to the calculation as well. In cases where there are large differentiation between the scored paths cost, is used to save the computation resources. If the path has a machine with efficiency gain less than a specific threshold value, the path will be eliminated conditioned to the maintenance action.

6.3. Mating Phase

The algorithm uses a modified two-parents-to-single child mating as a discrete version of PSO to be implemented in parallel. A single PSO particle has a predefined feature-operation string to follow based on the crossover and mutation procedures, but, the machine chosen path has is selected by step. In other words, the particle own experience term in continuous algorithm discretized in path list selection step. The designed sub-pool attaches chromosomes respecting to the survival rate and the migration rate.

Survival rate: A rate that defines the number of candidate chromosomes to be transferred from generation to the next. The candidates follow score pattern, which categorizes the sub-pool into classes based on the fitness.

Migration rate: For the parallel computing, depending on the chosen migration topology, each sub-pool communicates with the adjacent one through sending and receiving candidate chromosomes.

Both rates are defined using a practical trial and error. Tracing back the PSO structure, a sub-population elects a lead/local-best chromosome respecting the best scored fitness, and a global best respecting the history of the best local. The global-best mates all other individuals to generate new off-springs.

6.3.1. Crossover

The applied crossover is a LOX on feature part of chromosome and POX upon operation strategy part, respectively.

6.3.2. Mutation Procedure

A random single point mutation is performed along a feature-operation strategy. In the case where one of the swapped results exceeds the chosen limitation, the strategy is randomly chosen from the operation available strategies.

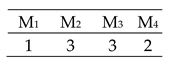

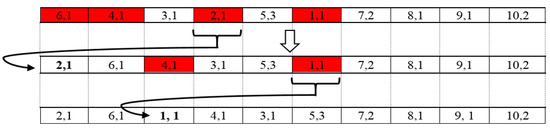

6.3.3. Precedence Repairing Mechanism

The resulted off-spring undergoes a precedence repair mechanism to reconsider the precedence constraints, to avoid wasting resources upon illegal chromosomes Awad et al. [84]. The mechanism is performed before the machine assignment step (path creation), in order to correct any confliction happened after the crossover and mutation procedures. As a shifting based strategy, wherein a dependent gene is dropped out from the string and the must-be-preceded genes shifted back corresponds to the gap gene, then the dropped out gene placed at the end array gap, as depicted in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Features 4 and 6 are locked by features 1 and 2, respectively.

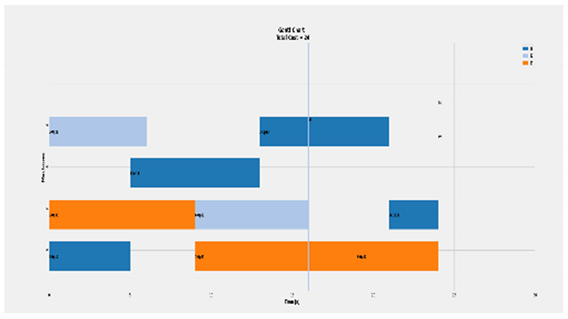

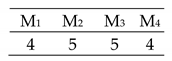

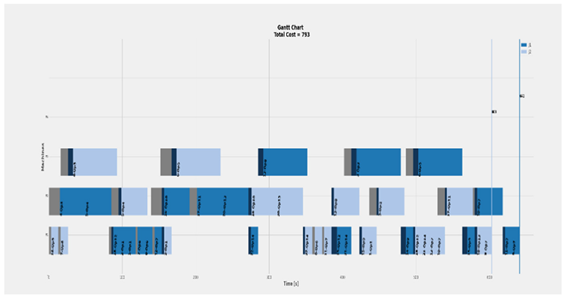

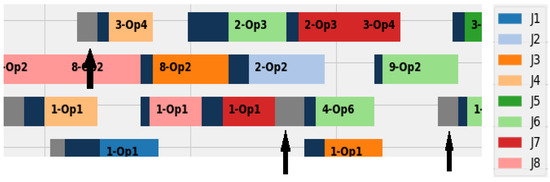

6.4. Objective Function

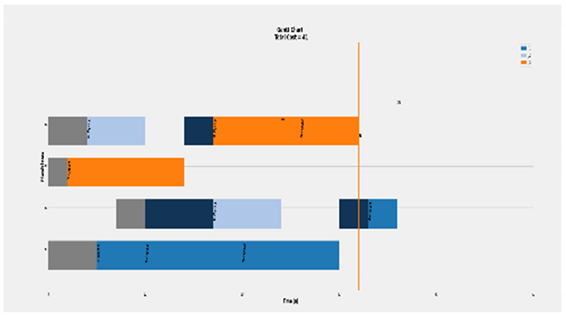

The objective function is a machine oriented programmed function. During each assignation step, the corresponding machine record the duration slots as in Figure 9, while Figure 10 indicates the difference between assigning tool change and machine transmission cost. The machine class has a history record that includes, the assigned job, feature, operation and the actual duration, plus the corresponding duration cost. During each new assignation the job-machine data is updated. Based on that the station cost is calculated regarding the completed working time of all machines, for machine ith, the machine ends at , and station cost is:

Figure 9.

Objective function calculations, For the jth job and ith machine, the previous machining performed at and next implementing machining starts at , while machine last assigned job ends at . The considered setups machine transmission of an instant job from previous to next machines or kth tool change indicated as and , respectively. Tool setup starts at .

Figure 10.

An example of the tool change calculation: Each job is represented by a different colour assigned to a feature-operation, the tool change duration is coloured in grey, where the three arrows pointed, and machine transmission duration is in navy blue. While job 4, feature 1 is assigned to operation, running on machine 3, machine 5 prepares the operation 4 selected tool that performs feature 3, of the same job. The same logic applied for job 6 and 8, as long as there is available time.

6.5. Neighborhood Searching Algorithm

As a starting point to evade from local optima repercussion, our problem-solving methodology employs a later stage of heuristic to ensure optimality in such complicated case. For that sake, a comparison is made between two modified single heuristics algorithms to find the best suitable next added stage. The considered modified single heuristics is an adaptive SA based and TS based as the following discussion. This section starts by stating the shared modified element that is shared through both modifications: the neighbors’ local search. In neighborhood searching techniques, the effectiveness of an algorithm depends on the strategy of the employed local search.

In general, single heuristics provide higher chances for near optimal solutions to escape local optima, which makes it more appropriate to be extensively utilized throughout a followed stage to the population based heuristics [68,85]. TS and SA used at JSSP are based as supplemented algorithms. The reason behind that can be deduced from two reciprocal inferences. One of them relates to the used single solution search itself. Applying upon the aforementioned techniques as the common used techniques. In SA, temperature behavior propels the early achieved solutions to better influence the individual progress, while in TS case, memory list length to ovoid repetitions [86,87,88]. On the same hand, in a discrete searching space with a single discovering step, available neighbor permutations run in O(n2) time, what is appeared as size-quality trade-off. Thus in order to satisfy near optimality in search space, the iterations gained extensive cost [43].

The local search improvements distilled to a parallel multi-start and a straightforward looping. The former enhancing step is wherein parallel multi-cores that can provide the advantage of emerging a Multi-Start (MS). While the straightforward step coordinates the variable neighbors search. Thus, instead of a large iterative local search, the adaptive single search algorithm is compressed into alleviated straightforward enhanced shake along each job upon a single-core and another horizontal shake up among cores at the same time.

6.5.1. Modified SA

The SA adaptability is entailed in three terms seeking improvements in neighbor local search as aforementioned and the move condition. The MS-SA shakes the best aforementioned chromosome resulted from the previous stage in random differently. Moreover, additional enhancement step is performed upon the rejection condition to avoid going through the same path of a deadlock progress. In that, where no progress happened in the inner phase of, the search back to the last scored best solution as a new initiated point. The adaptive SA for a single core is introduced in Table 3.

Table 3.

Modified SA Procedure.

6.5.2. Modified TS

Parallelization introduces a small memory for each core. As an accumulated case, the neighbors are explored in feature-of-job arrangement and feature-of-cell arrangement. The feature-of-job arrangement utilizes the variable neighbors’ structure adopted by Li et al. [15] to discover per job feature adjacent combinations amidst consistent adjacent jobs. The feature-of-cell arrangement switches the search between adjacent jobs as an intra-loop.

7. Results and Discussions

In the software context, all the models coding and formulation are executed in python upon a Spyder 4.1.4 environment. The codes are implemented on Lenovo PC with an Intel Core i7-4720HQ processor of 2.6GHZ. The result of this study is discussed considering a number of problems that were recorded as benchmarks from previous studies. The algorithm is carried out on python Spyder 4.1.4 environment, meanwhile, the parallel implementation is performed through the CPU using the encapsulated DEAP library. To further evaluate the proposed algorithm accurately, the benchmarks are tested as their original studies suggest with the same parameters mapped on the designed algorithm. Then, some of them are tested respecting to the new considerations. The desired fitness function is structured to obey the following criteria:

- Minimum transmission cost.

- Workload to maintenance balance based.

- Minimum make-span.

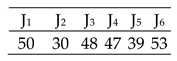

7.1. Experiments Set

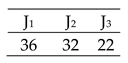

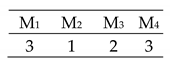

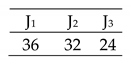

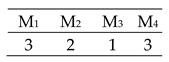

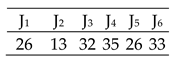

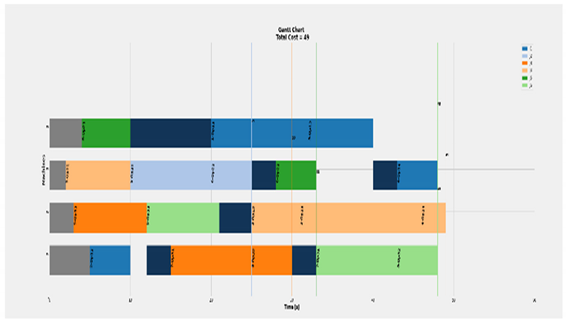

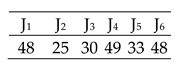

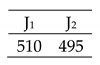

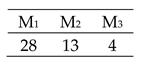

The first group of experiments are carried out through the original data sets taken from Kacem et al. [89,90], Chan et al. [91], Gao et al. [92], Teekeng et al. [93], Zhang et al. [94,95], as indicated in Table 4, in order to check the algorithm validity using varied configurations. The data sets have no precedence constraints, which make them sufficient to test only the first stage of the proposed method. GA algorithms the simple two-to-two mating termed as GA and the GA introduced by Li et al. [47], and two types of PSO, the designed PSO (DPSO) and the PSO mating according to Li et al. [15], all are implemented upon parallel CPU, and the parameters are tuned as in Table 4.

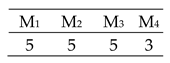

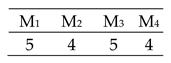

Table 4.

Parallel implementation parameters.

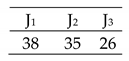

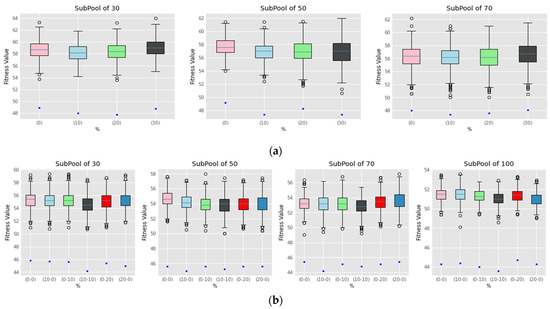

The second set of data recorded by Naseri et al. [96], Li et al. [15], Shao et al. [97] and Leung et al. [98] display a precedence constraints and machine transmission is considered.

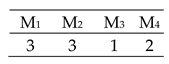

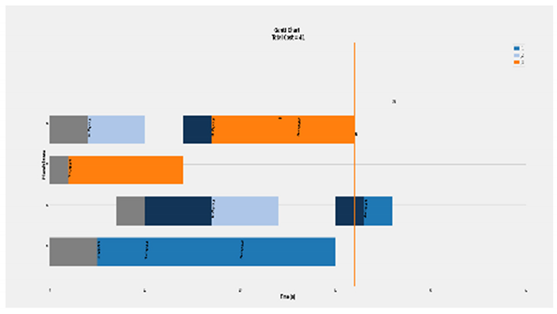

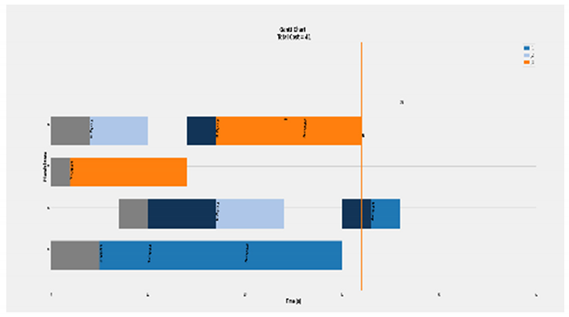

The second set of experiments are designed to trace the effect of first stage migration and history rates. Figure 11 concludes the rates effect by example upon 12 × 7 case included in Table 5, where the rates presented as a percentage of the total number of chromosomes of sub-pool size. Supplementing the sub-pool with around 10 % of its total number of chromosomes shows a stable improvement along the GA and the DPSO algorithms. This may be resulted as enhancement in the explored solution or the minimum hit fitness value. That progress encourages the experiments to follow the 10:15 % rate divided between the rates as indicated in Table 5.

Figure 11.

Migration - history rate effect upon: (a) GA sub-pool of sizes of 30, 50 and 70, respectively. (b) PSO sub-pool of sizes 30, 50, 70 and 100, respectively.

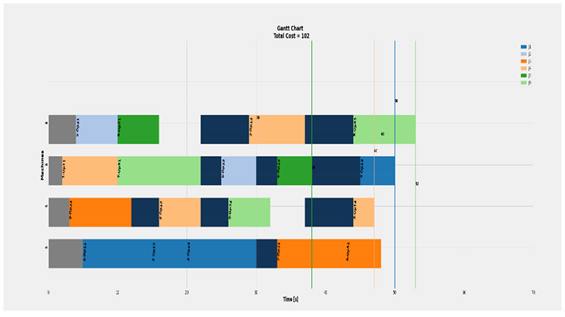

Table 5.

Recorded results.

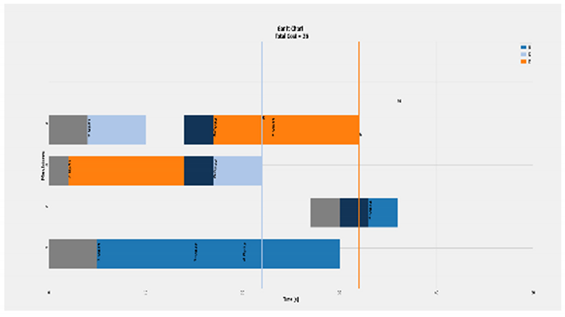

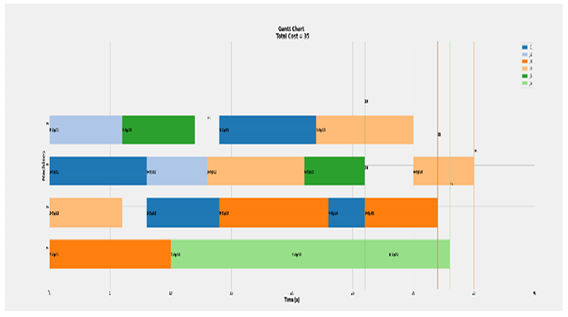

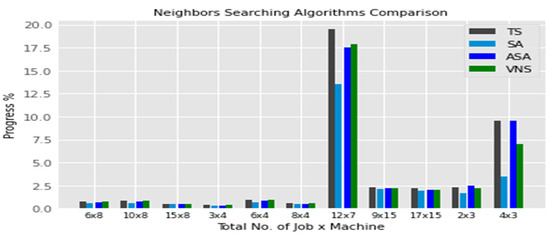

Till that point, the first stage is studied in strict scope, which moves the investigation to the second stage. The used neighbors searching algorithm is going to be the multi-start TS algorithm, since it produces the best followed progress across studied cases, some of them are used during the comparison. As declared by Figure 12, the multi-start adaptive SA (ASA) improves the SA results as expected, but multi-start TS is still obtaining the overall best scored values.

Figure 12.

Neighbors searching algorithms comparisons.

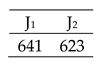

7.2. Experiments Set 2

This set of experiments are performed upon the previous mentioned data sets, in addition to Falih et al’s [99] recorded benchmark, in addition to other extended problems. The corresponding solutions are presented in Table 6. The transmission cost, the tool change cost and the work-load effect are included later, where the Table 7 is referring to that case as a complete case. In Table 7, total cost exhibits the resulted final cost considering the penalties, where actual cost points the exact time duration of the executed jobs. A threshold value is set equal to 50%, since if a tool exceeds that point, a tool change is needed. During that set, the tool electricity profiles are recorded as an indicator referring to machine-tool efficiency. The recorded profiles are calibrated before applied to the cosine similarity measure. Furthermore, a deterioration factor is tuned roughly for the sake of a tool model life-cycle wearing. Here, a deterioration factor of 0.98 is included during the process, such that a deterioration penalty balances the workload with the operation duration Od and machine-tool state Ms as:

Penalty = Od * (−log(Ms))

Table 6.

Falih et al. [98] based problems best recorded solutions.

Table 7.

Complete progress of different resulted scenarios.

8. Conclusions and Future Work

This study discusses FJSP scheduling as a case that can benefit from the smart manufacturing big data in order to make scheduling more realistic and up to date with the machine life cycle. Via that available new data, the scheduling will be able to gain awareness as the other manufacturing terms. In that, the machine tool change and maintenance can be scheduled as a part of the FJSP scheduling cycle. The challenge is in how the inserted data will be handled to serve the diversification and the intensification terms of the heuristic based algorithms without fall only in the diversification terms.

The designed algorithm utilizes the PSO with a modified selection algorithm implement such a continuous algorithm in the discrete domain considering the machine/tool efficiency data. The suggested data can be extended to include the features position in future cases. Energy consumption and the tool cracking through an image processing based techniques can be added as well.

In terms of implementations, the advances in parallel computing have brought GPU techniques into the spotlight. These techniques may be inserted in a future work with the current tested CPU parallel implementation, especially when image processing comes into action. Therefore, the JSSP based problems will be capable of achieving fully dynamic environment.

Author Contributions

Methodology, software, validation, and formal analysis, H.M.A.-E.; investigation, and data curation, M.A.A. and H.M.A.-E.; writing—original draft preparation, H.M.A.-E.; writing—review and editing, H.M.A.-E.; supervision, M.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results can be found contacting authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pereira, A.C.; Romero, F. A review of the meanings and the implications of the Industry 4.0 concept. Procedia Manuf. 2017, 13, 1206–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalenogarea, L.S.; Beniteza, G.B.; Ayalab, N.F.; Franka, A.G. The expected contribution of Industry 4.0 technologies for industrial performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 204, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronau, N. Determining the appropriate degree of autonomy in cyber-physical production systems. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2019, 26, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Peng, Y.; Wang, B.; Yao, S.; Liu, Z. Review on cyber-physical systems. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2017, 4, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Qi, Q.; Wang, L.; Nee, A. Digital Twins and Cyber–Physical Systems toward Smart Manufacturing and Industry 4.0: Correlation and Comparison. Engineering 2019, 5, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachalek, J.; Bartalsky, L.; Rovny, O.; Sismisova, D.; Morhac, M.; Loksik, M. The digital twin of an industrial production line within the industry 4.0 concept. In Proceedings of the 2017 21st International Conference on Process Control (PC), Strbske Pleso, Slovakia, 6–9 June 2017; pp. 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koulamas, C.; Kalogeras, A. Cyber-Physical Systems and Digital Twins in the Industrial Internet of Things Cyber-Physical Systems. Computer 2018, 51, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Foropon, C.; Godinho Filho, M. When titans meet—Can industry 4.0 revolutionise the environmentally-sustainable manufacturing wave? The role of critical success factors. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 132, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolio, T.; Copani, G.; Terkaj, W. Key esearch priorities for factories of the future: The Italian flagship initiative. In Factories of the Future: The Italian Flagship Initiative; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 1–494. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, R.Y.; Xu, X.; Klotz, E.; Newman, S.T. Intelligent Manufacturing in the Context of Industry 4.0: A Review. Engineering 2017, 3, 616–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, O.; Watson, N.; Porcu, L.; Bacon, D.; Rigley, M.; Gomes, R.L. Cloud manufacturing as a sustainable process manufacturing route. J. Manuf. Syst. 2018, 47, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinedo, M.L. Scheduling: Theory, Algorithms, and Systems, 5th ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ausaf, M.F.; Li, X.; Gao, L. Optimization algorithms for integrated process planning and scheduling problem—A survey. In Proceedings of the 11th World Congress on Intelligent Control and Automation, Shenyang, China, 29 June–4 July 2014; pp. 5287–5292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gao, L.; Shao, X. An active learning genetic algorithm for integrated process planning and scheduling. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 6683–6691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gao, L.; Wen, X. Application of an efficient modified particle swarm optimization algorithm for process planning. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2013, 67, 1355–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzanji, R.; Naderi, B.; Begen, M.A. Decomposition algorithms for the integrated process planning and scheduling problem. Omega 2020, 93, 102025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, W.; Mileham, A.; Owen, G. Applications of particle swarm optimisation in integrated process planning and scheduling. Robot. Comput. Manuf. 2009, 25, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Jiang, P. A Cyber-physical System Architecture in Shop Floor for Intelligent Manufacturing. Procedia Cirp 2016, 56, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gyulai, D.; Bergmann, J.; Gallina, V.; Gaal, A. Towards a connected factory: Shop-floor data analytics in cyber-physical environments. Procedia Cirp 2019, 86, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Tao, F.; Nee, A. Digital Twin Enhanced Dynamic Job-Shop Scheduling. J. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 58, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, P.; Pinto, A.; Moniz, S.; Silva, C. Thirty Years of Flexible Job-Shop Scheduling: A Bibliometric Study. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 180, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoch, S.; Chauhan, S.S.; Kumar, V. A review on genetic algorithm: Past, present, and future. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 8091–8126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezugwu, A.E.; Shukla, A.K.; Nath, R.; Akinyelu, A.A.; Agushaka, J.O.; Chiroma, H.; Muhuri, P.K. Metaheuristics: A comprehensive overview and classification along with bibliometric analysis. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2021, 54, 4237–4316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, G.; Kumar, V. Spotted hyena optimizer: A novel bio-inspired based metaheuristic technique for engineering applications. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2017, 114, 48–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harifi, S.; Mohammadzadeh, J.; Khalilian, M.; Ebrahimnejad, S. Giza Pyramids Construction: An ancient-inspired metaheuristic algorithm for optimization. Evol. Intell. 2020, 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegherr, H.; Heider, M.; Hähner, J. Classifying Metaheuristics: Towards a unified multi-level classification system. Nat. Comput. 2020, 2020, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, J.; Lanka, K.; Rao, A.N. A Review of Dynamic Job Shop Scheduling Techniques. Procedia Manuf. 2019, 30, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johar, F.M.; Azmin, F.A.; Suaidi, M.K.; Shibghatullah, A.; Ahmad, B.H.; Salleh, S.N.; Aziz, M.Z.A.A.; Shukor, M.M. A review of Genetic Algorithms and Parallel Genetic Algorithms on Graphics Processing Unit (GPU). In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Control System, Computing and Engineering; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), Penang, Malaysia, 29 November–1 December 2013; Volume 8, pp. 264–269. [Google Scholar]

- Somani, A.; Singh, D.P. Parallel Genetic Algorithm for solving Job-Shop Scheduling Problem Using Topological sort. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Advances in Engineering Technology Research (ICAETR-2014), Singapore, Singapore, 29–30 March 2014; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, G.; Yao, X.; Macleod, I.; Kang, L.; Chen, Y. Parallel genetic algorithm on PVM. Wuhan Univ. J. Nat. Sci. 1996, 1, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; El Baz, D.; Xue, R.; Hu, J. Solving the dynamic energy aware job shop scheduling problem with the heterogeneous parallel genetic algorithm. Futur. Gener. Comput. Syst. 2020, 108, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, P.; Silva, C. Parallel Metaheuristics for Shop Scheduling: Enabling Industry 4.0. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 180, 778–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.R.; Gen, M. Accelerating genetic algorithms with GPU computing: A selective overview. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 128, 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gen, M.; Cheng, R. Genetic Algorithms and Engineering Optimization; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.-K.; Chen, Y.-P.; Chou, J.-H. Solving Distributed and Flexible Job-Shop Scheduling Problems for a Real-World Fastener Manufacturer. IEEE Access 2014, 2, 1598–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.M.; Yin, H.L.; Wang, J. Genetic algorithm with new encoding scheme for job shop scheduling. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2009, 44, 977–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, E.T.; Li, D.; Murlidhar, B.R.; Armaghani, D.J.; Kassim, K.A.; Komoo, I. The effects of ABC, ICA, and PSO optimization techniques on prediction of ripping production. Eng. Comput. 2019, 36, 1355–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharkan, I.; Saleh, M.; Ghaleb, M.A.; Kaid, H.; Farhan, A.; Almarfadi, A. Tabu search and particle swarm optimization algorithms for two identical parallel machines scheduling problem with a single server. J. King Saud Univ.-Eng. Sci. 2020, 32, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Zhou, L.; Hu, B.; Lin, C. An Adaptive Scheduling Algorithm for Dynamic Jobs for Dealing with the Flexible Job Shop Scheduling Problem. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2019, 61, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- García-León, A.A.; Dauzère-Pérès, S.; Mati, Y. An efficient Pareto approach for solving the multi-objective flexible job-shop scheduling problem with regular criteria. Comput. Oper. Res. 2019, 108, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Sui, Y. Bi-objective Optimization of Multiple-route Job Shop Scheduling with Route Cost. IFAC-Pap. 2019, 52, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defersha, F.M.; Rooyani, D. An efficient two-stage genetic algorithm for a flexible job-shop scheduling problem with sequence dependent attached/detached setup, machine release date and lag-time. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 147, 106605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbi, E.-G. Metaheuristics: From Design to Implementation; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, I.-C.; Kim, S.-I.; Kim, H.-S. A genetic algorithm with a mixed region search for the asymmetric traveling salesman problem. Comput. Oper. Res. 2003, 30, 773–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalzala, A.M.S.; Fleming, P.J. Genetic Algorithms in Engineering Systems; Institution of Electrical Engineers: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bierwirth, C. A generalized permutation approach to job shop scheduling with genetic algorithms. Oper. Res. Spectr. 1995, 17, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gao, L.; Pan, Q.; Wan, L.; Chao, K.-M. An Effective Hybrid Genetic Algorithm and Variable Neighborhood Search for Integrated Process Planning and Scheduling in a Packaging Machine Workshop. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2018, 49, 1933–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanat, A.; Almohammadi, K.; Alkafaween, E.; Abunawas, E.; Hammouri, A.; Prasath, V.B.S. Choosing Mutation and Crossover Ratios for Genetic Algorithms—A Review with a New Dynamic Approach. Information 2019, 10, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nedjah, N.; de Macedo Mourelle, L. Real-World Multi-Objective System Engineering; Nova Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, W.; Yurcik, W.J.; Yin, X. Outsourcing internet security: Economic analysis of incentives for managed security service providers. In International Workshop on Internet and Network Economics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 947–958. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, E.; Zandieh, M.; Farrokh, M.; Emami, S.M. A multi objective optimization approach for flexible job shop scheduling problem under random machine breakdown by evolutionary algorithms. Comput. Oper. Res. 2016, 73, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.R.; Mahapatra, S. A quantum behaved particle swarm optimization for flexible job shop scheduling. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2016, 93, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Peng, Z.; Du, B.; Guo, J.; Xu, W.; Zhuang, K. Hybrid artificial bee colony algorithm with a rescheduling strategy for solving flexible job shop scheduling problems. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2017, 113, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouiri, M.; Bekrar, A.; Jemai, A.; Trentesaux, D.; Ammari, A.C.; Niar, S. Two stage particle swarm optimization to solve the flexible job shop predictive scheduling problem considering possible machine breakdowns. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2017, 112, 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, R.H.; Gnanavelbabu, A.; Vaidyanathan, T. An effective backtracking search algorithm for multi-objective flexible job shop scheduling considering new job arrivals and energy consumption. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 149, 106863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Sun, Y. A green scheduling algorithm for flexible job shop with energy-saving measures. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 3249–3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, A.; Wu, X.; Peng, J.; Yan, P. Energy-efficient bi-objective single-machine scheduling with power-down mechanism. Comput. Oper. Res. 2017, 85, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, H.; Hasani, A. An energy-efficient multi-objective optimization for flexible job-shop scheduling problem. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2017, 104, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Tang, D.B.; Xu, Y.C.; Li, W.D. Energy-aware Integrated Process Planning and Scheduling for Job Shops. In Sustainable Manufacturing and Remanufacturing Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 13–36. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Li, W.; He, F. A multi-granularity NC program optimization approach for energy efficient machining. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2018, 115, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Zhang, C.; Shao, X.; Ren, Y. MILP models for energy-aware flexible job shop scheduling problem. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 710–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Tang, D.; Giret, A.; Salido, M.A. Multi-objective optimization for energy-efficient flexible job shop scheduling problem with transportation constraints. Robot. Comput. Manuf. 2019, 59, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodjanloo, M.; Tavakkoli-Moghaddam, R.; Baboli, A.; Bozorgi-Amiri, A. Flexible job shop scheduling problem with reconfigurable machine tools: An improved differential evolution algorithm. Appl. Soft Comput. 2020, 94, 106416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrogio, G.; Guido, R.; Palaia, D.; Filice, L. Job shop scheduling model for a sustainable manufacturing. Procedia Manuf. 2020, 42, 538–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, G.; Su, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, T. A population-based iterated greedy algorithm for no-wait job shop scheduling with total flow time criterion. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2020, 88, 103369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Z.; Hua, J.; Yi, Z. Multi-objective Integrated Optimization Problem of Preventive Maintenance Planning and Flexible Job-Shop Scheduling. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management 2016; 2017; pp. 137–141. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.2991/978-94-6239-255-7_25 (accessed on 20 September 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, C.-S.; Li, P.-Y.; Wei, J.-M.; Wu, M.-C. Integration of process planning and scheduling for distributed flexible job shops. Comput. Oper. Res. 2020, 124, 105053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Tang, R.; Peng, T.; Tao, L.; Jia, S. A method for minimizing the energy consumption of machining system: Integration of process planning and scheduling. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 1647–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Dong, M.; Chen, F. Single-machine-based joint optimization of predictive maintenance planning and production scheduling. Robot. Comput. Manuf. 2018, 51, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavari, M.; Isvandi, S. Integrated decision making for parts ordering and scheduling of jobs on two-stage assembly problem in three level supply chain. J. Manuf. Syst. 2018, 46, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yang, J.-J.; Zheng, L.-Y. Multi-Agent Based Hyper-Heuristics for Multi-Objective Flexible Job Shop Scheduling: A Case Study in an Aero-Engine Blade Manufacturing Plant. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 21147–21176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.-H.; Wu, M.-C.; Tan, H.; Peng, Y.-H.; Chen, C.-F. A genetic algorithm embedded with a concise chromosome representation for distributed and flexible job-shop scheduling problems. J. Intell. Manuf. 2018, 29, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Shen, X.; Li, C. The flexible job-shop scheduling problem considering deterioration effect and energy consumption simultaneously. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 135, 1004–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhou, X. Flexible job-shop scheduling problem with job precedence constraints and interval grey processing time. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 149, 106781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Huang, M.; Wang, Z.Y.; Zhu, Q.B. Robust scheduling based on extreme learning machine for bi-objective flexible job-shop problems with machine breakdowns. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 158, 113545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiee, M.; Zandieh, M.; Ramezani, P. Bi-objective partial flexible job shop scheduling problem: NSGA-II, NRGA, MOGA and PAES approaches. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2012, 50, 7327–7342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vela, C.R.; Afsar, S.; Palacios, J.J.; González-Rodríguez, I.; Puente, J. Evolutionary tabu search for flexible due-date satisfaction in fuzzy job shop scheduling. Comput. Oper. Res. 2020, 119, 104931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Hu, Y.; Sun, J.; Zhang, W. An improved genetic algorithm for the flexible job shop scheduling problem with multiple time constraints. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2020, 54, 100664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarghandi, H. Solving the no-wait job shop scheduling problem with due date constraints: A problem transformation approach. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 136, 635–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Chen, R.; Li, Y.; Peng, Z.; Guo, S.; Du, Y. Flexible job-shop scheduling with tolerated time interval and limited starting time interval based on hybrid discrete PSO-SA: An application from a casting workshop. Appl. Soft Comput. 2019, 78, 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotskov, Y.N.; Gholami, O. Mixed graph model and algorithms for parallel-machine job-shop scheduling problems. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2014, 55, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanjul-Peyro, L. Models and an exact method for the Unrelated Parallel Machine scheduling problem with setups and resources. Expert Syst. Appl. X 2020, 5, 100022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacini, E.; Mateos, C.; Garino, C.G. Dynamic Scheduling based on Particle Swarm Optimization for Cloud-based Scientific Experiments. CLEI Electron. J. 2014, 17, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, M.A.; Abd-Elaziz, H.M. An Efficient Modified Genetic Algorithm For Integrated Process Planning-Job Scheduling. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Mobile, Intelligent, and Ubiquitous Computing Conference (MIUCC), Cairo, Egypt, 26–27 May 2021; pp. 319–323. [Google Scholar]

- Baykasoğlu, A.; Madenoğlu, F.S.; Hamzadayı, A. Greedy randomized adaptive search for dynamic flexible job-shop scheduling. J. Manuf. Syst. 2020, 56, 425–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, F. Tabu Search—Part I. Informas J. Comput. 1989, 1, 190–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rego, C.; Alidaee, B. Metaheuristic Optimization via Memory and Evolution Tabu Search and Scatter Search; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.C.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Chen, T.-L.; Lin, J.Z. Comparison of simulated annealing and tabu-search algorithms in advanced planning and scheduling systems for TFT-LCD colour filter fabs. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2016, 30, 516–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacem, I.; Hammadi, S.; Borne, P. Approach by Localization and Multiobjective Evolutionary Optimization for Flexible Job-Shop Scheduling Problems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part C (Appl. Rev.) 2002, 32, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacem, I.; Hammadi, S.; Borne, P. Pareto-optimality approach for flexible job-shop scheduling problems: Hybridization of evolutionary algorithms and fuzzy logic. Math. Comput. Simul. 2002, 60, 245–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, F.T.; Kumar, V.; Tiwari, M.K. Optimizing the Performance of an Integrated Process Planning and Scheduling Problem: An AIS-FLC based Approach. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE Conference on Cybernetics and Intelligent Systems, Bangkok, Thailand, 7–9 June 2006; Volume 59, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gao, J.; Gen, M.; Sun, L. Scheduling jobs and maintenances in flexible job shop with a hybrid genetic algorithm. J. Intell. Manuf. 2006, 17, 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teekeng, W.; Thammano, A. Modified Genetic Algorithm for Flexible Job-Shop Scheduling Problems. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2012, 12, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, G.; Shao, X.; Li, P.; Gao, L. An effective hybrid particle swarm optimization algorithm for multi-objective flexible job-shop scheduling problem. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2009, 56, 1309–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, H.E.; Driss, O.B.; Ghédira, K. Solving the flexible job shop problem by hybrid metaheuristics-based multiagent model. J. Ind. Eng. Int. 2017, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin-Naseri, M.R.; Afshari, A.J. A hybrid genetic algorithm for integrated process planning and scheduling problem with precedence constraints. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2012, 59, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Li, X.; Gao, L.; Zhang, C. Integration of process planning and scheduling—A modified genetic algorithm-based approach. Comput. Oper. Res. 2009, 36, 2082–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.; Wong, T.; Mak, K.; Fung, R.Y.K. Integrated process planning and scheduling by an agent-based ant colony optimization. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2010, 59, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falih, A.; Shammari, A.Z.M. Hybrid constrained permutation algorithm and genetic algorithm for process planning problem. J. Intell. Manuf. 2020, 31, 1079–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).