Abstract

Carbon dioxide is one of the major greenhouse gases and a leading source of global warming. Several adsorbent materials are being tested for removal of carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere. The use of multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) as a CO2 adsorbent material is a relatively new research avenue. In this study, Fe2O3/Al2O3 composite catalyst was used to synthesize MWCNTs by cracking ethylene gas molecules in a fluidized bed chemical vapor deposition (CVD) chamber. These nanotubes were treated with H2SO4/HNO3 solution and functionalized with 3-aminopropyl-triethoxysilane (APTS). Chemical modification of nanotubes removed the endcaps and introduced some functional groups along the sidewalls at defected sites. The functionalization of nanotubes with amine introduced carboxylic groups on the tube surface. These functional groups significantly enhance the surface wettability, hydrophilicity and CO2 adsorption capacity of MWCNTs. The CO2 adsorption capacity of as-grown and amine-functionalized CNTs was computed by generating their breakthrough curves. BELSORP-mini equipment was used to generate CO2 breakthrough curves. The oxidation and functionalization of MWCNTs revealed significant improvement in their adsorption capacity. The highest CO2 adsorption of 129 cm3/g was achieved with amine-functionalized MWCNTs among all the tested samples.

1. Introduction

Global warming, due to the emission of greenhouse gases, is a challenging issue for the environment, which is gaining widespread attention within the research community [1]. The excessive use of fossil fuels has increased the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere above a safe level [2]. Roughly 60% of global warming is attributed to CO2 emissions, which is much higher than the total contribution of the rest of the greenhouse gases [3]. At present, CO2 content in the atmosphere is approximated to be 400 ppm, which is 25% higher than the pre-industrial level (300 ppm) [3]. Therefore, control over CO2 emissions and its removal from the atmosphere is an imperative, in order to keep concentration at or below the safe level. Many efforts are underway to remove CO2 from flue gases produced at large industrial units, such as steel manufacturing plants, thermal power stations and oil refineries [4].

Although a set of techniques, namely physical absorption, chemical absorption, adsorption and membranes are being used for CO2 capture; these techniques are in their infancy and are not yet fully mature. Over the past few years, extensive experimental work has been carried out to produce CO2 adsorbents that can adsorb large amounts of CO2 with low energy penalties on the method of regeneration [5]. As an outcome, numerous materials have been reported for CO2 adsorption. These materials include zeolites, carbon nanotubes, mesoporous spherical particles and activated carbon [6]. Among these materials, multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) are recognized as a promising adsorbent for CO2 because of their unique mechanical, chemical, thermal and electrical properties and extremely good characteristics at nanoscale, such as high surface area and porosity [7].

Relatively better CO2 adsorption capacity of MWCNTs is due to their graphitic structures, suitable pore size and the wide spectrum of functional groups attached to the tube surface. The functional groups are attached to the tube through a chemical process. The primary functional group to be attached to the tube surface is the amine group that can adsorb CO2 by means of chemisorption. The amine precursor such as 3-Aminopropyl-triethoxysilane (APTS) can be used to functionalize MWCNT to get an amine group. Gui et al. [8] revealed that the amine-functionalized MWCNTs produce more promising results on CO2 adsorption in a cost effective way. Similar kind of results were reported by Su et al. [9]. They found that MWCNTs, functionalized with APTS, exhibit fast kinetics and relatively better CO2 adsorption than the other adsorbent materials. However, a search of the previous literature demonstrates very limited scientific progress on this aspect of MWCNT. Further research would help to gain insight into the efficient use of MWCNTs as an adsorbent material for CO2 and other greenhouse gases.

CO2 adsorption capacity of MWCNTs is reported extremely sensitive to their structural properties [7,8]. Additionally, low cost production of nanotubes of good graphitic symmetry and controlled diameter distribution would be supportive to their use in mainstream industry. A review of the published work has revealed chemical vapor deposition (CVD) as a best approach for explicit results on synthesis of well-structured MWCNTs [10,11]. The expected advantages of a CVD method include flexible geometry, comparatively reduced process temperature, excellent parametric control and low production cost [11]. In a fluidized bed CVD method, the catalyst particles vigorously mix-up with fluidizing or precursor gas under suitable bed conditions. The significant process conditions are reaction time, reaction temperature and precursor flowrate. The catalyst particles are fully exposed to the precursor gas molecules when they are fluidized in the reaction column. The reactive surface area of the catalyst and diffusion of carbon atoms into the catalyst increase under fluidized bed state. The enhanced catalytic activity supports the rapid cracking of precursor gas molecules and thus the formation of carbon nanotubes (CNTs).

In this research, MWCNTs of controlled structural characteristics were produced by fluidizing Al2O3 supported iron oxide catalyst in a fluidized bed CVD chamber. Ethylene molecules were decomposed into hydrogen and carbon at a furnace temperature of 800 °C. The as-grown MWCNTs were treated with a H2SO4/HNO3 mixture and functionalized with 3-aminopropyl-triethoxysilane. The pristine and amine-functionalized MWCNTs were tested for their CO2 adsorption capacity. A BELSORP-mini equipment was used to generate the breakthrough curves of MWCNTs for the study of their CO2 adsorption capacity.

2. Materials and Methods

Fe2O3/Al2O3 composite was used as a catalyst for the synthesis of MWCNTs. The synthesis route and morphology of the catalyst are discussed in our previous work [12]. Ethylene was decomposed over Fe2O3/Al2O3 composite under optimum CVD conditions. A fluidized bed setup with CVD arrangement was used for the synthesis of MWCNTs. [12]. The as-grown CNTs were characterized for their surface morphology and internal structures by using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Through acid treatment and amine functionalization, some functional groups were subsequently attached to CNT structures. Finally, pristine, acid treated and amine functionalized CNTs were tested for their CO2 adsorption.

2.1. Fluidized Bed CVD Synthesis of MWCNTs

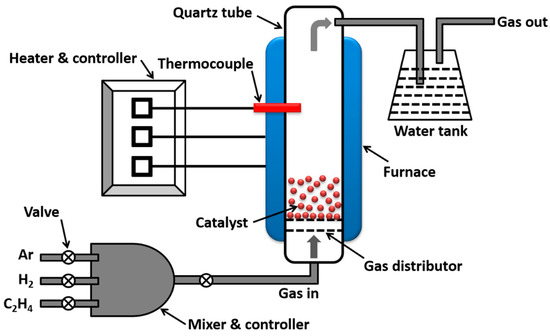

An OTF-1200X-80-VT fluidized bed CVD reactor with vertical quartz tube arrangement was used for synthesis of MWCNTs. A schematic illustration of the OTF-1200X-80-VT setup is given in Figure 1. This configuration consisted of a splitable vertical tube furnace. The vacuum sealed furnace with 80 mm tube diameter was capable of fast heating, up to 1200 °C, creating a thermal gradient by regulating the temperature of heating zone and heating the samples in the vacuum and gas flow regimes. A gas mixing device was used to supply the quartz tube with blended gases. Digital flow controllers were used to regulate the flow of gases. Fe2O3/Al2O3 catalyst was put on a grit, fixed inside the quartz tube, and MWCNTs were synthesized by decomposing ethylene over catalyst particles. Since highest temperature was noticed in the mid-zone of the tube furnace, the catalyst particles were fluidized in this zone for improved activity of the catalyst. The optimum conditions for this CVD setup are identified in our previous work [12]: The optimum catalyst weight is 0.3 g, ethylene flowrate is 100 sccm and CVD temperature is 800 °C. In this work, similar conditions have been used to synthesize MWCNTs. The catalyst (0.3 g) was placed on grit and fluidized by bottom-up flow of argon gas at a flowrate of 250 sccm. The temperature of the heating zone in the furnace was raised from room temperature to 800 °C at the rate of 15 °C/min. At this stage, 100 sccm of ethylene and 250 sccm of hydrogen were also mixed with argon and supplied to the reaction chamber. The cracking of ethylene for CNT synthesis was performed for an hour, after which the CVD chamber was left to cool at room temperature by providing only argon gas.

Figure 1.

Schematic of fluidized bed CVD setup.

2.2. Acid Treatment and Functionalization

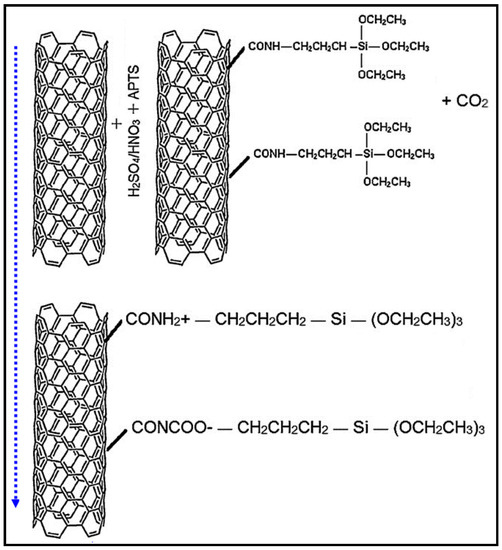

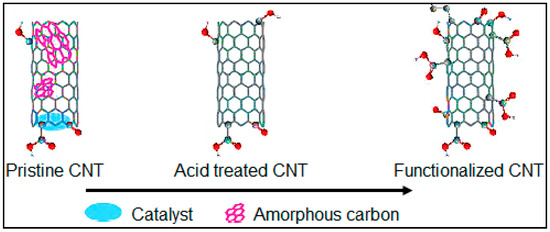

For CO2 adsorption study, CNTs were subjected to an acid treatment followed by functionalization with APTS. Firstly, the nanotubes were treated with a mixture of 4 M HNO3 and H2SO4. Thereafter, the acid treated CNTs were functionalized with APTS. All the acids, APTS and toluene were supplied by the Sigma-Aldrich. The acid treatment of MWCNTs was primarily conducted for the removal of catalyst particles and the carboxylation of the pristine nanotubes prior to amine-functionalization, as shown in Figure 2. Mild acids were chosen for the oxidation of CNTs and to keep the tube structure intact. Acid treatment also loosens the agglomerated and entangled nanotubes that usually form due to van der Waals attraction between tubes. For acid treatment, 1 g of MWCNTs was taken in a beaker containing 4 M of HNO3/H2SO4 (v:v; 1:1). The dispersion was stirred vigorously at 500 rpm for 15 h. To ensure uniform mixing of nanotubes in the acidic medium, the high stirring rate of 500 rpm was chosen. After 15 h of acid treatment, the mixture was filtered in a vacuum filtration unit with 0.45 μm filter paper. The sample was cleaned several times with deionized water and dried in an oven at 80 °C for 12 h.

Figure 2.

Mechanism of treatment of MWCNTs with acid and amine.

Functionalization of acid treated MWCNTs was conducted with APTS treatment, which introduced a series of chemical reactions along the interface and consequently increased CO2 adsorption capacity of MWCNTs. The amine-functionalization introduces peptide bonds through chemical reaction of carboxyl groups, attached on the tube surface during acidic treatment, with the amine-groups from APTS, as shown in Figure 2. In this process, 60 vol.% APTS solution was prepared by adding 60 mL of 97% pure APTS in 40 mL of 99.8% pure toluene. Hereinafter, 1 g of acid treated MWCNTs was dispersed in APTS solution in a glass flask [8]. The dispersion was refluxed for 2 h by heating at 100 °C. The vigorous mixing of the blend was carried out by continuous stirring at 500 rpm. The mixture was then left to cool down at ambient temperature. Finally, the mixture was filtered with a membrane filter paper of 0.45 μm pore size. To remove the excess APTS, the sample was washed with toluene and dried for 2 h at 120 °C.

2.3. CO2 Adsorption Test

The adsorption capacities of pristine, acid treated and amine functionalized MWCNTs were studied using a BELSORP-mini (BEL Japan, Inc.) instrument. It is a comparatively simple and user-friendly gas adsorption measuring technique. The powders and porous media were analyzed through this technique to measure distribution of pore size and surface area. The automated CO2 adsorption tests were conducted after setting the sample cells in the ports. The extracted data was analyzed using BELSORP-mini dedicated software. This software has a system-check feature for diagnosing the system performance automatically. Three CNT samples were screened simultaneously, and for each sample, autonomous isotherm of CO2 adsorption was produced.

Experiments on CO2 adsorption began with pre-treatment of CNT samples followed by an estimation of dead volume and production of adsorption isotherms. Feed gas was a mixture of 80% nitrogen and 20% CO2. Selection of the gases was made to comply with environmental conditions and to prevent corrosion of the flow-line due to the acidic nature of CO2. To obtain only CO2 adsorption isotherms, the experiments were conducted at a fixed temperature of 25 °C. Nitrogen works as a standard adsorptive at −196.15 °C, therefore this temperature condition should be met for adsorption of nitrogen by any material [13,14]. As CO2 adsorption measurements were taken at 25 °C, only CO2 was adsorbed by MWCNTs. Considering the acid-base concept, the role of amine groups was to assist CO2 adsorption by CNTs [15]. Amine acted as a base while CO2 acted as an acid during the adsorption process. The results, obtained with the BELSORP-mini, were the data plots between partial pressure and CO2 volume adsorbed by 1 g of MWCNTs (cm3/g).

3. Results and Discussion

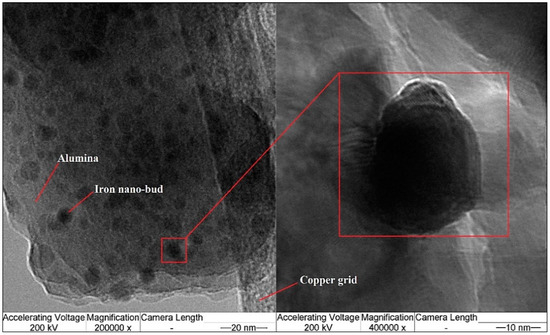

Alumina is a relatively better catalyst support compared to other materials, enabling high metal dispersion and density of active catalytic sites [16,17]. Chemical interactions between alumina (Al2O3) and metal catalysts accelerate the oxidation occurring at catalyst–Al2O3 interfaces. Such catalyst morphology minimizes the aggregation of metal species and the formation of unwanted big clusters, leading to the growth of CNTs with many structural defects [18]. Zhao et al. [19] advised that although CNTs are being synthesized using compound catalysts having iron as one component, it is difficult to increase the yield, growth rate and length of nanotubes proportionally with the weight percentage of iron in the catalyst. It was found that more and more catalyst particles work as “seeds” for rapid nucleation of CNTs with an increase in iron content in the catalyst. TEM analyses of the catalyst were conducted to elaborate on the morphology of the alumina surface and iron nanoparticles dispersed on the surface. TEM images of iron particles, grown over alumina support, are shown in Figure 3. The magnified TEM micrograph show that the iron nanoparticles are embedded on the alumina surface. The bright field in the micrographs is the surface of the large alumina particle. The dark field or dark spots on relatively brighter background are iron nanoparticles. The magnified view of the catalyst confirms the spherical shape of the iron buds having a diameter between 9 nm and 15 nm. The average diameter of the iron nanoparticles was measured to be about 12.3 nm. It is discernible that iron particles are well dissolved and crystallized on alumina surfaces to form a mixed oxide system [20].

Figure 3.

TEM micrographs of iron nanoparticles grown over alumina support.

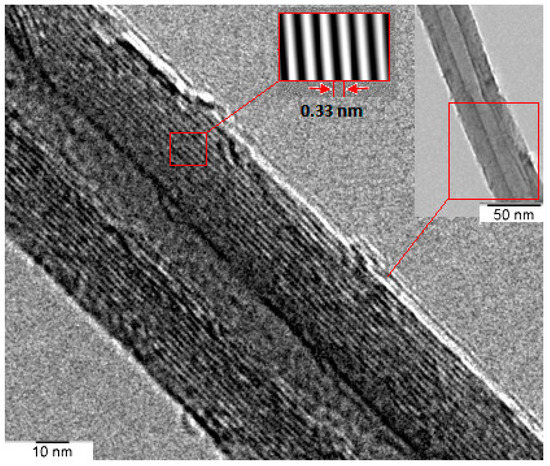

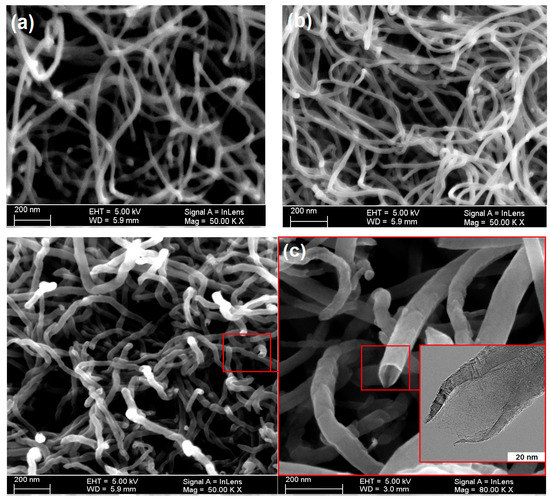

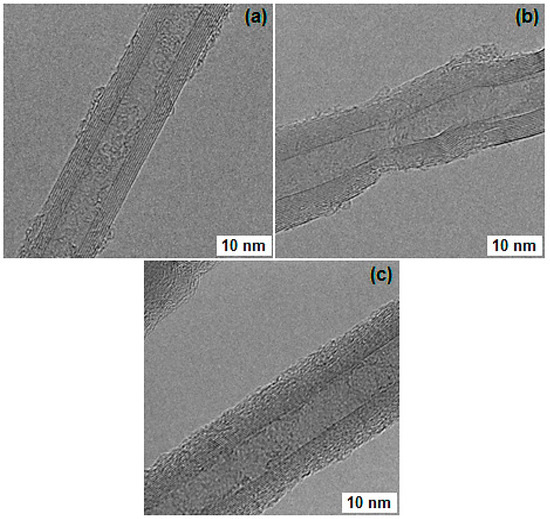

Good catalytic activity of Al2O3 nanoparticles promotes decomposition of precursor gas and minimizes the catalyst poisoning. Fine structures of MWCNTs were obtained with the distribution of tube diameter in the range of 20–25 nm. The TEM image in Figure 4 reveals that fine graphite sheets were rolled in the form of MWCNTs. No catalyst particles or amorphous carbon were spotted in CNT structures. The inter-layer spacing in a MWCNT was measured to be about 0.33 nm. CNTs were distributed evenly in ethanol by conducting ultrasonic agitation prior to TEM imaging. Most of the unused catalyst particles and other impurities had been washed away during the sonication process.

Figure 4.

TEM micrograph of pristine MWCNTs.

3.1. Morphology of Pristine and Chemically Modified MWCNTs

High chemical stability of MWCNTs restricts the formation of functional groups at the tube surface. CNTs generally work with organic functional groups to enhance their solubility and dispersion [5]. MWCNTs are usually functionalized through both covalent and non-covalent bonds in order to overcome their hydrophobicity and to alter the surface properties chemically [21]. These bonds improve the wettability of MWCNTs in water and other polar solvents. At the same time, these groups work as active sites to anchor the functional groups through electrostatic, covalent and hydrogen bonds. Before functionalization, CNTs are purified through chemical oxidation. During chemical oxidation, the catalyst particles are dissolved in the acidic medium. The purification step removes the amorphous carbon, improves the surface area of the tube, and reduces or raises the volume of the mesopores and micropores. Purification also induces additional functional groups by decomposing the existing functional groups, as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Illustration of the removal of catalyst and amorphous carbon from pristine CNTs through acid treatment and functionalized through APTS treatment.

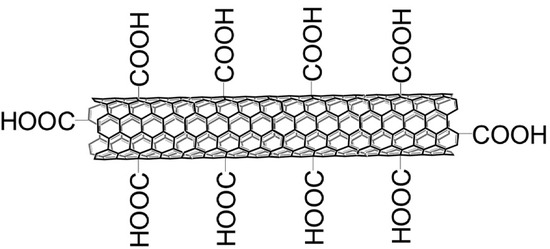

The acid treatment loosened up the agglomerated and entangled nanotubes, which normally form due to van der Waals attraction. The acid treated MWCNTs were functionalized through APTS treatment, which introduced a number of functional groups on the tube surface. These functional groups may improve CO2 adsorption capacity of nanotubes. SEM micrographs of acid treated and amine functionalized MWCNTs are shown in Figure 6. It was seen that chemical treatment did not tailor the tube morphology. No damaging or cutting of tubes took place after acid treatment. The ends of most of the nanotubes were found opened after chemical treatment. The open ends would be supportive to the attachment of maximum number of function groups to the tube surface, as illustrated in Figure 7. Since a mild acidic solution was used to treat nanotubes, open ended nanotubes with minimum damages were obtained during the oxidation process. If an aqueous solution is used for the oxidation of nanotubes, it may damage the tube surface. These results are in line with the findings of Goyanes et al. [22].

Figure 6.

SEM micrographs of (a) pristine MWCNTs, (b) acid treated MWCNTs, and (c) amine functionalized MWCNTs.

Figure 7.

Illustration of the attachment of oxygen containing groups during the oxidation of MWCNTs.

TEM micrographs, shown in Figure 8, reveal some structural defects in the hexagonal structures of nanotubes after performing the acid treatment. These structural defects, induced by acid treatment, functioned as active sites for anchoring mine-groups during APTS treatment [8]. The smooth surface of as-grown MWCNTs was changed to groovy surface during functionalization, due to appearance of functional groups on the outer surface. After functionalization, the transparency of nanotubes also reduced, potentially due to the attachment of functional groups on the tube surface [15,16]. The diameter of pristine CNTs ranged from 20 nm to 25 nm, which was slightly increased after functionalization. This increase in diameter is attributed to the COOH-group which attached to the outer tube surface. This result reconfirms the successful attachment of COOH-group onto the surface of MWCNTs [23]. The tube defects created during acidic treatment may also change the sp2 hybridization of MWCNT to sp3 hybridization [24].

Figure 8.

TEM micrographs of (a) pristine MWCNTs, (b) acid treated MWCNTs, and (c) amine functionalized MWCNTs.

Open ends and sidewalls of nanotubes might have various oxygen containing groups. The amines may attach to the carboxylic groups formed during acid treatment of CNTs [25,26]. Pan and Xing [27] reported that the functional groups can change the wettability of CNTs by making them more hydrophilic. These CNTs may show good adsorption capacity for polar compounds and for those with lower molecular weights. An acid treatment is given to open the pores blocked by the amorphous carbon and catalyst particles. Particles from the catalyst mostly cap the ends of the nanotubes.

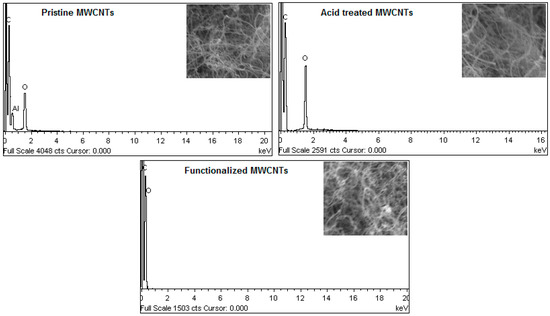

EDX spectra, reported in Figure 9, show appreciable differences in oxygen content of pristine and chemical modified MWCNTs. The new functional groups that also contain oxygen were grafted on the tube surface. The overall oxygen amount in the sample was increased from 2.89% to 6.26% after performing acidic treatment. With amine-functionalization of the acid treated MWCNTs, the oxygen content was further increased to 9.48%. It reveals that oxidation not only introduces –OH and –COOH groups to the tube surface but also generates new active sites for effective functionalization. By creating amide bonds, the induced groups allowed covalent coupling of the molecules [28].

Figure 9.

EDX spectra of pristine and chemically modified MWCNTs.

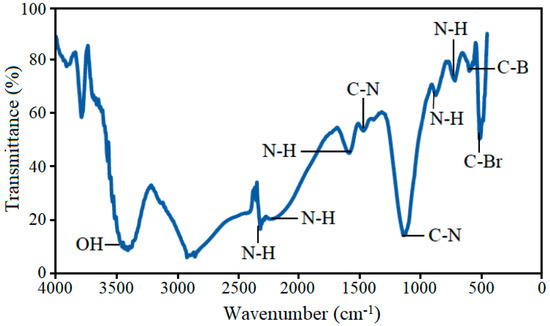

The most important characteristic of functionalized MWCNTs is the presence of amine groups on the tube structure. FT-IR technique was employed to detect the functional groups. The modified MWCNTs were expected to have the carboxyl group with additional attachment of hydrophilic groups, such as the amino group, due to the existence of a nitrogen element in the acid mixture (HNO3/H2SO4). Figure 10 shows the FT-IR spectrum of functionalized MWCNTs. Hydroxyl group (OH) attachment on MWCNTs was observed at 3406.59 cm−1. The FT-IR peak at 3440 cm−1 is assigned to OH- group, which appears due to water in KBr and/or moisture in the CNT sample [29]. As discussed earlier, acid treatment of MWCNTs induced some defects in their hexagonal structures. The amine functionalization of these CNT structures was much easier than the pristine CNT structures [23]. The other hydrophilic groups, found in an acid treated sample, are OH stretching at a wave number of 2401 cm−1. According to Kyotan et al. [30], amino group is considered as hydrophilic group and pristine CNTs can never be a better adsorbent than modified CNTs. High hydrophobicity and bundling issues limit the adsorption capacity of pristine CNTs.

Figure 10.

FT-IR spectrum of amine functionalized MWCNTs.

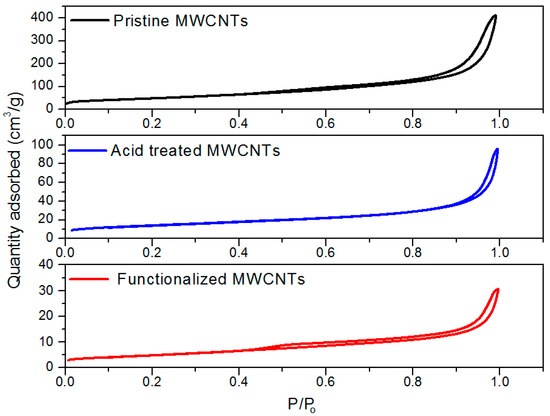

The textural and physical properties of MWCNTs, including surface area, distribution of pore sizes and pore volume were analyzed with surface area and porosity (SAP) analyzer. BET technique was employed to obtain isotherms of nitrogen adsorption at 77 K temperature and relative pressure of 0.0001–0.99. The highest surface area and pore volume were exhibited by pristine MWCNTs, followed by acid treated MWCNTs, and amine functionalized MWCNTs. The adsorption/desorption isotherms of nitrogen are shown in Figure 11. Pristine CNTs adsorbed the highest amount of nitrogen among all the tested samples. The lowest adsorption of nitrogen was observed with amine functionalized MWCNTs. Since most of the porosity of functionalized MWCNTs was supposed to be grafted and blocked by functional groups [31], APTS concentration caused attachment of excessive amine precursor molecules on the tube surface by giving lower nitrogen adsorption [32]. From theses isotherm plots, it can be concluded that functionalized MWCNTs would experience lower nitrogen adsorption due to attachment of carboxyl and hydrophilic groups.

Figure 11.

Adsorption/desorption isotherms of pristine and modified MWCNTs.

The isotherm for pristine and modified MWCNTs exhibited an I–V shape where nitrogen adsorption capacity revealed an increasing trend with relative pressure [32]. As the samples were characterized mostly for mesopores, ranging from 2 nm to 5 nm, the hysteresis phenomenon happened when relative pressure reached the maximum value of 1. This phenomenon describes the existence of capillary nitrogen condensation in the mesopores. [33]. The pristine MWCNTs posed high pore volume and surface area among all the tested samples. A reduction in pore size reflects that amine groups may block the pore openings during functionalization of CNTs. Many of the pores were inaccessible to nitrogen gas. By comparing the physical characteristics of pristine and chemically modified CNTs, it is discovered that surface area and pore volume decrease mainly due to blocking of pore openings with primary amine groups. [31,34]. Similar results for different APTS-modified adsorbents are reported in the published literature [35].

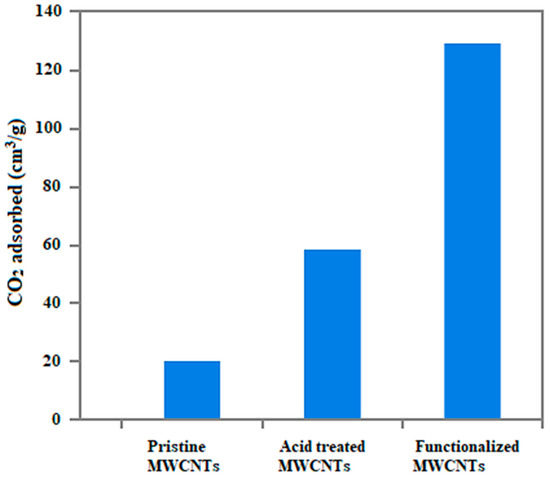

3.2. CO2 Adsorption Capacity of MWCNTs

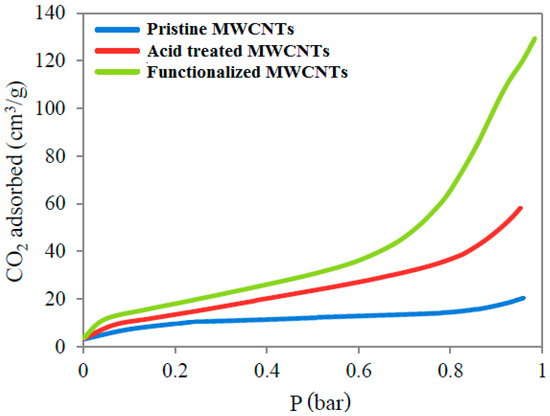

Both pristine and modified MWCNTs were further tested for their CO2 adsorption capacity by generating adsorption isotherms. Figure 12 shows CO2 adsorption profiles of pristine and modified MWCNTs. Pristine MWCNTs had lowest CO2 adsorption of 20 cm3/g followed by acid treated (59 cm3/g) and amine functionalized (129 cm3/g) MWCNTs. After amine functionalization of CNTs, CO2 adsorption capacity was increased by 545%. The presence of amine groups on the surface of nanotubes permitted the adsorption of CO2 via chemisorption. Physical adsorption also occurred due to CO2 capturing at several sites of MWCNTs, such as internal surface, interstitial channels, external groove sites and external surface.

Figure 12.

CO2 adsorption capacities of pristine and modified MWCNTs.

The breakthrough curves in Figure 13 show that CO2 adsorption by all samples was quite slow at the beginning. However, adsorption by acid treated and amine functionalized MWCNTs was drastically increased after 0.7 bar pressure. Minimum CO2 was adsorbed by pristine MWCNTs because of the absence of amine functional groups on CNT structures. The most of CO2 adsorption in pristine CNTs happened through physisorption phenomenon rather than chemisorption. Contrarily, in chemically modified MWCNTs, the amine groups on the tube surface contributed to the chemisorption during CO2 adsorption. In the pressure range of 0 to 0.6 bar, chemisorption was expected to occur, involving the chemical bonding between amine groups and CO2. Thereafter, physisorption was expected to play its role in the drastic increase of CO2 adsorption from 20 cm3/g to 129 cm3/g. CO2 adsorption via chemisorption is always slower than physisorption [36], which justifies the trend of breakthrough curves at lower pressures (0 to 1 bar).

Figure 13.

Adsorption breakthrough curves of pristine MWCNTs, acid treated MWCNTs, and amine functionalized MWCNTs.

4. Conclusions

MWCNTs were synthesized by decomposing ethylene over Fe2O3/Al2O3 composite in a fluidized bed CVD reactor. These MWCNTs were acid treated and amine-functionalized for the study of their CO2 adsorption capacity. Both pristine and functionalized MWCNTs were tested for their surface morphology and CO2 adsorption capacity. Chemical modification was mostly restricted to opening the caps and attaching the functional groups on the sidewalls with active sites. Thereafter, amine functionalization introduced a number of carboxylic groups on the tube surface. These functional groups appreciably changed the wettability of tube surfaces and consequently made MWCNTs more hydrophilic and suitable for CO2 adsorption. The breakthrough curves revealed that the modified MWCNTs show high CO2 adsorption as compared to the pristine and acid treated MWCNTs. Overall, CO2 uptake by pristine nanotubes, acid treated and amine functionalized nanotubes was measured to be about 20 cm3/g, 59 cm3/g and 129 cm3/g, respectively. Furthermore, the amount of CO2 taken-up by both pristine and modified MWCNTs was increased with an increase in partial pressure. It reveals that nanotubes were consistent in CO2 adsorption from the start to the end of the adsorption process.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S. and N.M.M.; methodology, M.Y.N.; validation, K.A.I., and N.M.A.-S.; formal analysis, S.S.; investigation, M.Y.N.; resources, A.G.; data curation, N.M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S; writing—review and editing, M.Y.N.; visualization, K.A.I.; supervision, S.S.; project administration, A.G.; funding acquisition, K.A.I. and N.M.A.-S.

Funding

This research was funded by Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia under the Research Group Project No. RG-1438-020.

Acknowledgments

This work is sponsored by King Saud University, Saudi Arabia under the Research Project No. RG1438-020.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Naz, M.Y.; Sulaiman, S.A. Slow release coating remedy for nitrogen loss from conventional urea: A review. J. Control. Release 2016, 225, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez, J.P.; Erdmann, E.; Manca, D. Optimal Design of a Carbon Dioxide Separation Process with Market Uncertainty and Waste Reduction. Processes 2019, 7, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, S.; Ghoreyshi, A.A.; Jahanshahi, M. Carbon dioxide captured by multiwalled carbon nanotube and activated charcoal: A comparative study. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 19, 153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Ahn, W.S. CO2 capture using mesoporous alumina prepared by a sol-gel process. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 166, 646–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, M.M.; Yap, Y.X.; Chai, S.-P.; Mohamed, A.R. Multi-walled carbon nanotubes modified with (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane for effective carbon dioxide adsorption. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2013, 14, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drage, T.C.; Blackman, J.M.; Pevida, C.; Snape, C.E. Evaluation of Activated Carbon Adsorbents for CO2 Capture in Gasification. Energy Fuels 2009, 23, 2790–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lua, A.C.; Guo, J. Activated carbon prepared from oil palm stone by one-step CO2 activation for gaseous pollutant removal. Carbon 2000, 38, 1089–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, M.M.; Yap, Y.X.; Chai, S.-P.; Mohamed, A.R. Amine-functionalization of multi-walled carbon nanotubes for adsorption of carbon dioxide. Asia-Pac. J. Chem. Eng. 2013, 8, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F.; Lu, C. CO2 capture from gas stream by zeolite 13X using a dual-column temperature/vacuum swing adsorption. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 9021–9027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukrullah, S.; Mohamed, N.M.; Shaharun, M.S. Optimum temperature on structural growth of multiwalled carbon nanotubes with low activation energy. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2015, 58, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See, C.H.; Harris, A.T. A Review of Carbon Nanotube Synthesis via Fluidized-Bed Chemical Vapor Deposition. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2007, 46, 997–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukrullah, S.; Mohamed, N.M.; Shaharun, M.S.; Naz, M.Y. Parametric study on vapor-solid-solid growth mechanism of multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2016, 176, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverria, J.; Morera, M.; Mazkiarán, C.; Garrido, J. Characterization of the porous structure of soils: Adsorption of nitrogen (77 K) and carbon dioxide (273 K), and mercury porosimetry. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 1999, 50, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, K.; Cracknell, R.F.; Nicholson, D. Nitrogen adsorption in slit pores at ambient temperatures: Comparison of simulation and experiment. Langmuir 1994, 10, 4606–4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanthana, J. In Situ Infrared and Mass Spectroscopic Study on Amine-Immobilized Silica for CO2 Capture: Investigation of Mechanisms and Degradation. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Akron, Akron, OH, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraju, N.; Fonseca, A.; Konya, Z.; Nagy, J.B. Alumina and silica supported metal catalysts for the production of carbon nanotubes. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2002, 181, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Ando, Y. Chemical Vapor Deposition of Carbon Nanotubes: A Review on Growth Mechanism and Mass Production. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2010, 10, 3739–3758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ago, H.; Nakamura, K.; Uehara, N.; Tsuji, M. Roles of Metal−Support Interaction in Growth of Single- and Double-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Studied with Diameter-Controlled Iron Particles Supported on MgO. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 18908–18915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, W.Z.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, H.T.; Gong, J.; Kim, I.J. Synthesis and growth of multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWNTs) by CCVD using Fe-supported zeolite templates. J. Ceram. Process. Res. 2011, 12, 392–397. [Google Scholar]

- Shukrullah, S.; Naz, M.Y.; Mohamed, N.M.; Ibrahim, K.A.; Ghaffar, A.; AbdEl-Salam, N.M. Production of bundled CNTs by floating a compound catalyst in an atmospheric pressure horizontal CVD reactor. Results Phys. 2019, 12, 1163–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, S.; Myers, K.; Subramanian, V. Amino-functionalized and acid treated multi-walled carbon nanotubes as supports for electrochemical oxidation of formic acid. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2011, 103, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyanes, S.; Rubiolo, G.R.; Salazar, A.; Jimeno, A.; Corcuera, M.A.; Mondragon, I. Carboxylation treatment of multiwalled carbon nanotubes monitored by infrared and ultraviolet spectroscopies and scanning probe microscopy. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2007, 16, 412–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Thu, L.; Long, N.C.; Trung, L.Q.; Tung, N.T.; Nghia, N.D.; Thanh, V.M. Surface modification and functionalization of carbon nanotube with some organic compounds. Adv. Nat. Sci. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2013, 4, 035017. [Google Scholar]

- Okpalugo, T.I.T.; Papakonstantinou, P.; Murphy, H.; McLaughlin, J.; Brown, N.M.D. High resolution XPS characterization of chemical functionalised MWCNTs and SWCNTs. Carbon 2005, 43, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, S.; Ghoreyshi, A.A.; Jahanshahi, M.; Pirzadeh, K. Enhancement of Carbon Dioxide Capture by Amine-Functionalized Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotube. Clean Soil Air Water 2013, 41, 939–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Ji, L.; Liu, H.; Hu, G.; Zhang, S.; Yang, M.; Yang, Z. Functionalized carbon nanotubes containing isocyanate groups. J. Solid State Chem. 2004, 177, 4394–4398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Xing, B. Adsorption Mechanisms of Organic Chemicals on Carbon Nanotubes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 9005–9013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buang, N.A.; Fadil, F.; Majid, Z.A.; Shahir, S. Characteristic of mild acid functionalized multiwalled carbon nanotubes towards high dispersion with low structural defects. Dig. J. Nanomater. Biostruct. 2012, 7, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, P.C.; Mo, S.Y.; Tang, B.Z.; Kim, J.K. Dispersion, interfacial interaction and re-agglomeration of functionalized carbon nanotubes in epoxy composites. Carbon 2010, 48, 1824–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyotani, T.; Nakazaki, S.; Xu, W.H.; Tomita, A. Chemical modification of the inner walls of carbon nanotubes by HNO3 oxidation. Carbon 2001, 39, 782–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F.; Lu, C.; Chen, H.-S. Adsorption, Desorption, and Thermodynamic Studies of CO2 with High-Amine-Loaded Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes. Langmuir 2011, 27, 8090–8098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Bai, H.; Wu, B.; Su, F.; Hwang, J.F. Comparative Study of CO2 Capture by Carbon Nanotubes, Activated Carbons, and Zeolites. Energy Fuels 2008, 22, 3050–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Jiang, J.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Pan, H.; Shi, Y. Adsorption of Low-Concentration Carbon Dioxide on Amine-Modified Carbon Nanotubes at Ambient Temperature. Energy Fuels 2012, 26, 2497–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grondein, A.; Belanger, D. Chemical modification of carbon powders with aminophenyl and aryl-aliphatic amine groups by reduction of in situ generated diazonium cations: Applicability of the grafted powder towards CO2 capture. Fuel 2011, 90, 2684–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Cai, N. Continuous CO2 Capture in Dual Fluidized Beds Using Silica Supported Amine. Energy Procedia 2013, 37, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Speight, J.G.; Ozum, B. Petroleum Refining Processes; Chemical Industries, Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2002; Volume 85, p. 706. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).