Abstract

In this paper, a numerical study is performed to investigate the effect of a periodic magnetic field on three-dimensional free convection of MWCNT (Mutli-Walled Carbone Nanotubes)-water/nanofluid. Time-dependent governing equations are solved using the finite volume method under unsteady magnetic field oriented in the x-direction for various Hartmann numbers, oscillation periods, and nanoparticle volume fractions. The aggregation effect is considered in the evaluation of the MWCNT-water/nanofluid thermophysical properties. It is found that oscillation period, the magnitude of the magnetic field, and adding nanoparticles have an important effect on heat transfer, temperature field, and flow structure.

1. Introduction

The control of the fluid flow and heat transfer via the magnetic damping effect can be an optimisation parameter in thermal and engineering systems such as microscope design, healthcare devices, biomechanics, and so on [1].

Izadi et al. [2] performed a numerical investigation on nanofluid’s free convection inside a porous medium using the FEM (Finite Element Method). The authors considered the variable magnetic field and mentioned that, for higher Ra values, the heat transfer reduces considerably owing to the applied magnetic field. On the basis of the FEM, Hatami et al. [3] analysed the effects of Fe3O4 nanoparticles and the variable magnetic field on natural convection. They mentioned that, owing to the induced Lorentz force, increasing the Hartman number causes a decrease in heat transfer. Hashim et al. [4] focused on unsteady flow of non-Newtonian Williamson nanofluid under the effect of a variable magnetic field and observed an enhancement of heat transfer rate with the Schmidt number. Sheikholeslami and Vajravelu [5] studied the Fe3O4/water flow under constant heat flux using CVFEM (Control Volume Finite Element Method). They concluded that the Rayleigh number and nanoparticles’ concentration increase the average temperature.

Sandeep and Animasaun [6] reported a work on the enhancement of heat transfer by adding nanoparticles. They included magnetic field effects. They compared two nanofluids and found that heat transfer rate of water-AA7075/nanofluid is significantly higher than that of water-AA072/nanofluid. Hatami et al. [7] investigated the effects of variable magnetic field on the MHD (Magnetohydrodynamics) forced convection of Al2O3–water nanofluid. They considered a porous flat plate with nonlinear stretching. Shah et al. [8] studied the influence of a variable magnetic field on the viscous fluid flow, heat, and mass transfer using analytical and numerical techniques using the homotopy analysis method. They observed that pressure and torque on the discs are highly affected by the distance between discs.

Nimmagadda et al. [9] studied the effect of jet impingement uniform on heat transfer of nanofluid under a non-uniform magnetic field. They found that the enhancement of heat transfer can reach 173% for a volume fraction of 3%. Nassar et al. [10] applied the magnetic field on thermoelectric cooler (TEC) to control working conditions at different magnetic field intensities.

Kefayati [11] used the LBM (Lattice Boltzmann method) technique to simulate the natural convection under sinusoidally varying temperature under a magnetic field. Al-Salem et al. [12] investigate the mixed convection with a driven lid. They observed an important decrease of that transfer with the Hartmann number. Bao et al. [13] applied the non-uniform magnetic field to simulate the heat and mass transfer during evaporation of mixed nitrogen and liquid oxygen. The effects of magnetic field direction on film boiling nanofluid are studied by Malvandi [14]. He indicated that the direction is an important parameter on boiling. Nessab et al. [15] conducted work on ferrofluid jet flow and heat transfer with the presence of a magnetic field. They observed that the heat transfer is increased with the increase of the (Mn) number and reduces with the opening ratio (R). The effects of magnetic field are tested for carbon nanotubes suspensions [16], peristaltic flow of Jeffrey fluid [17], unsteady separated stagnation-point flow [18], and forced convection through semi-annulus [19]. Qin et al. [20] offers a new, simpler approach that, for the first time, makes it possible to continuously measure the reflectivity of non-touchable surfaces. More details about the subject can be found in the literature [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52].

The main purpose of this paper is to test the application of variable magnetic field on heat transfer and fluid structure in a three-dimensional cavity filled with MWCNT-nanofluid. On the basis of the authors’ knowledge and wide literature survey, natural convection in MWCNT-nanofluid filled 3D cavities under periodic magnetic field has not been studied. Thus, the study will help to readers to understand the mechanism of control of heat transfer via variable magnetic field.

2. Physical Model

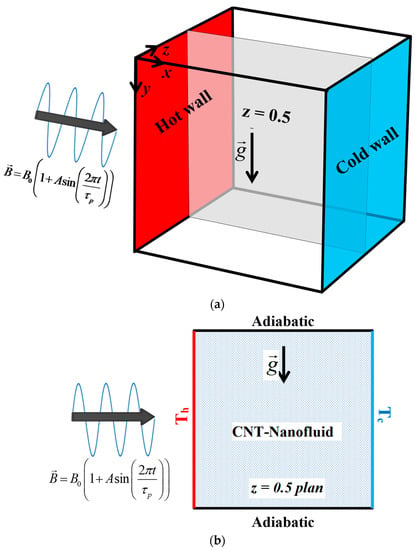

The considered configuration with boundary conditions is presented on Figure 1. The flow is considered as laminar and tow vertical walls are at a constant temperature (Th and Tc). The remaining walls are considered adiabatic. A periodic external magnetic field is applied along the x-direction. The cavity is filled with a MWCNT-water nanofluid. The properties of MWCNT and water are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

(a) Three dimensional configuration; (b) z = 0.5 plan with boundary conditions.

Table 1.

Properties of water and MWCNT nanoparticles.

2.1. Governing Equations

To simplify the resolution of the governing equations, the 3D vorticity vector potential formalism was used. In fact, it allows the elimination of the pressure gradient terms.

The vorticity and vector potential are expressed as follows:

and

To get the dimensionless governing equations, the variables , , , , , and , are divided by , , , , , , and , respectively, and

with

with

The effective thermophysical properties are evaluated using the following expressions:

- -

- Density:

- -

- Heat capacitance:

- -

- Dynamic viscosity:

Taking into account the fractal shape of aggregates [25], the modified nanoparticle volume fraction (volume fraction of the aggregates in water), , is expressed as follows:

where

- ra is the radii of the aggregates;

- rp is the radii of the primary solid particles;

- D is the fractal index depending on shear flow condition and type, size, and shape of the aggregates.

Thus, based on the Maron and Pierce model [26] and the expression of the modified volume fraction, the effective viscosity of the MWCNT-nanofluid can be expressed as follows:

On the basis of the experimental work of Halelfadl et al. [27] for MWCNT with = 1.5 μm and = 9.2 nm, it was determined that D = 2.1, = 0.0361, and ra/rp = 4.41.

- Thermal conductivity (Xue-model):

On the basis of Nan’s model [28] and taking into account the aggregates effect, the effective thermal conductivity of MWCNT is calculated using the following expressions:

where

- is the transverse thermal conductivity;

- is the longitudinal thermal conductivity;

- is the nanoparticle diameter;

- is the nanoparticle length;

- is the Kapitza radius;

- is the Kapitza resistance (fixed at 8.83 × 10−8m2 K/W);

- is volume fraction of the MWCNT in the aggregate.

- electrical conductivity:

The local and average Nusselt numbers are evaluated using the following:

As the applied magnetic field in this study is periodic, it is expected that will be periodic; thus, a time averaged Nusselt number () is defined as follows:

The solution is considered satisfactory if Equation (18) is satisfied in each time:

2.2. Boundary Conditions

The boundary conditions for the present problem are given as follows:

Temperature:

on the right wall, and on the left wall.

on the remaining walls.

Vorticity:

, , at and 1.

, , at and 1.

, , at and 1.

Vector potential:

at and 1.

at and 1.

at and 1.

Velocity:

on all walls.

Electric potential:

on all walls.

Current density:

on all walls.

3. Solution Procedure, Grid Sensitivity Test, and Validation

The central-difference scheme based control volume method is used to discretize Governing Equations (4)–(8). The fully implicit procedure and central-difference scheme are used to treat the temporal derivatives and the convective terms, respectively.

The grid independency test was performed for Ha = 50, φ = 0.05, and = 1. The tests were conducted for different grids. The time averaged Nusselt number was the sensitive parameter. The incremental increase between the grid 81 × 81 × 81 and 91 × 91 × 91 is only 0.333% (Table 2). For solution accuracy and time economy, a spatial mesh size of 81 × 81 × 81 is retained to perform all the simulations.

Table 2.

Grid independency test.

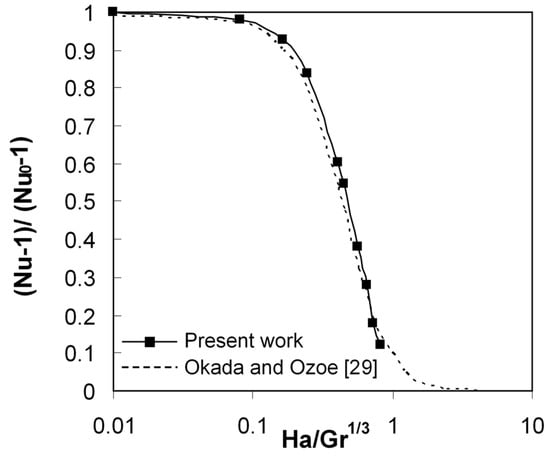

The verification of the present code is firstly performed by comparing with results Okada and Ozoe [29], who proposed an experimental correlation (Equation (19)) allowing the evaluation of the Nusselt number as function of the Hartman and Grashof numbers for the case of gallium filled cubical cavity. Figure 2 shows an excellent concordance with the results of Okada and Ozoe [29].

Figure 2.

Comparison with the results of Okada and Ozoe [29].

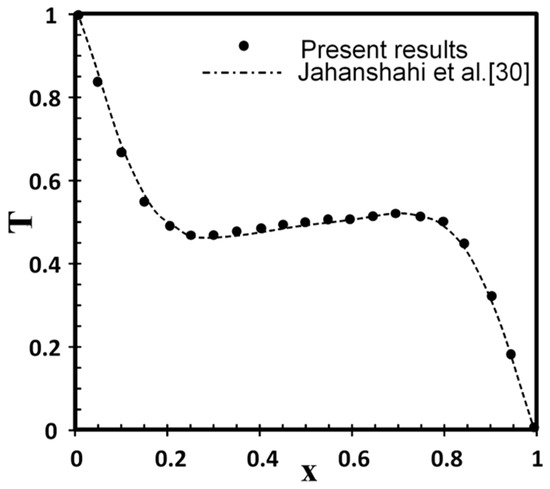

In the case of nanofluids, a comparison was performed with the results of Jahanshahi et al. [30]. As presented in Figure 3, the comparison also shows a good agreement.

Figure 3.

Comparison with the results of Jahanshahi et al. [30].

4. Results and Discussion

A finite volume based computational work was performed to investigate the three-dimensional natural convection of MWCNT-water/nanofluid filled cavity under variable magnetic field. While adding MWCNT particles enhances the heat transfer owing to high effective thermal conductivity, the application of a magnetic field opposes this enhancement. Thus, the simultaneous influence of a variable magnetic field and adding nanoparticles on the 3D flow and heat transfer is investigated.

The periodic magnetic field is considered along the x-direction. The Rayleigh number is fixed at Ra = 105 and the amplitude (A) is fixed at 0.5, so that the magnitude of the magnetic field oscillates between 0.5B0 and 1.5B0. Owing to the relatively low considered volume fractions, the single phase model is adopted. The ranges of Hartman number, MWCNT volume fraction, and oscillation period are (0 ≤ Ha ≤ 100), (0 ≤ φ ≤ 0.05), and (0.01 ≤ ≤ 10), respectively.

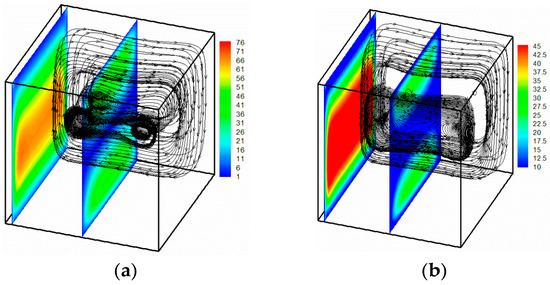

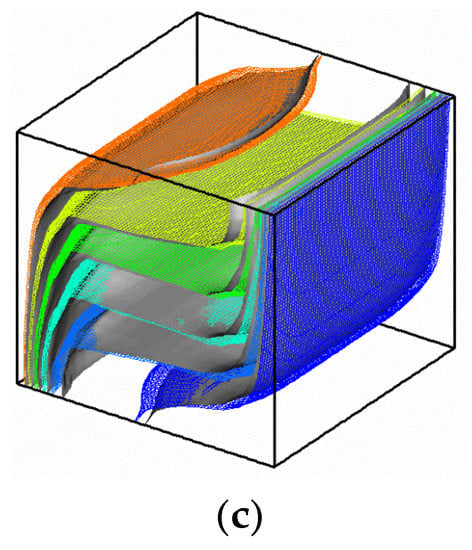

In absence of a magnetic forces, the flow structure and temperature field are presented in Figure 4. The flow structure is shown via some particle trajectories. For φ = 0 (pure water), two central clockwise vortices characterize the flow structure. Adding MWCNT particles was found to enhance the buoyancy forces and to increase the size of the vortices. The particle paths are shifted towards the isothermal walls and the vortices become adjacent to these walls.

Figure 4.

Flow structure (a): φ = 0 and (b) φ = 0.05 and temperature field (c): φ = 0.05 (coloured) and φ = 0 (grey).

It is to be noted that the maximum of the velocity magnitude is lowered by adding nanoparticles owing to the inter-particular friction caused by the increase of the viscosity. The maximal values of the magnitude of the velocity are located near to the active walls because of the important gradients of temperatures in these regions.

Figure 4c presents the temperature field for Ha = 0. The iso-surfaces of temperature are vertically stratified at the core region and distorted near of the active walls. This phenomenon becomes more pronounced by adding the MWCNT nanoparticles with an increase of the temperature gradient.

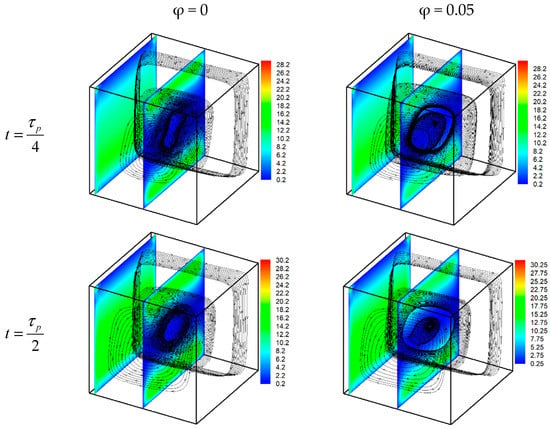

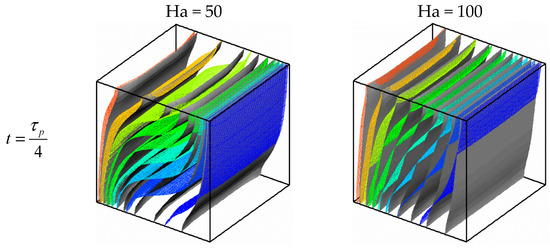

Figure 5 presents the 3D pathlines and velocity magnitude at different times of the oscillation period for Ha = 50 and = 1. The results for pure water are presented on the left side and those of MWCNT-water nanofluid with φ = 0.05 are presented on the right. The interaction between the magnetic field and the fluid motion generates a Lorentz force that opposes the buoyancy forces, causing the damping effect. This damping is more important near the active walls, except near the corners. In fact, because of the electric insulation of the walls, the electric current is redirected, and thus the Lorentz force vanishes in these regions. In addition, a merging phenomenon occurs and the pathlines become characterized by only one clockwise vortex.

Figure 5.

Pathlines and velocity magnitude for Ha = 50 and = 1.

The lateral flow (near of the walls) is also affected by the applied magnetic field and the longitudinal flow becomes less pronounced owing to the reduction of the 3D character (MHD bi-dimensionalization). The structure and the intensity of the flow change slightly during the oscillation period. In fact, the size and the shape of the vortexes change periodically with the time.

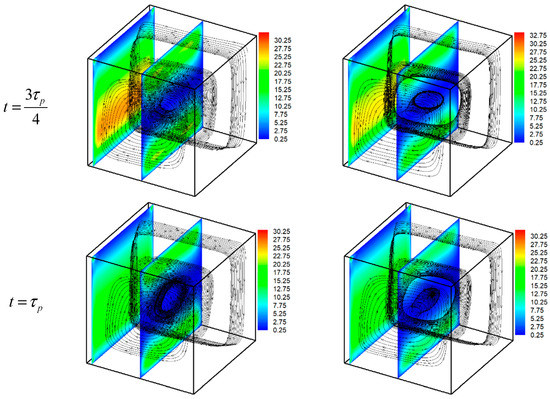

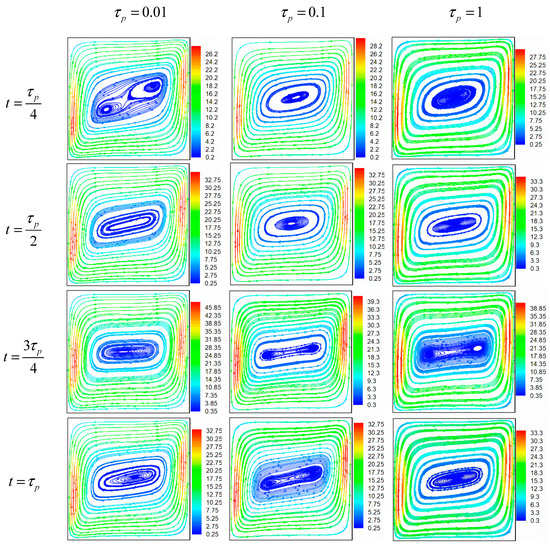

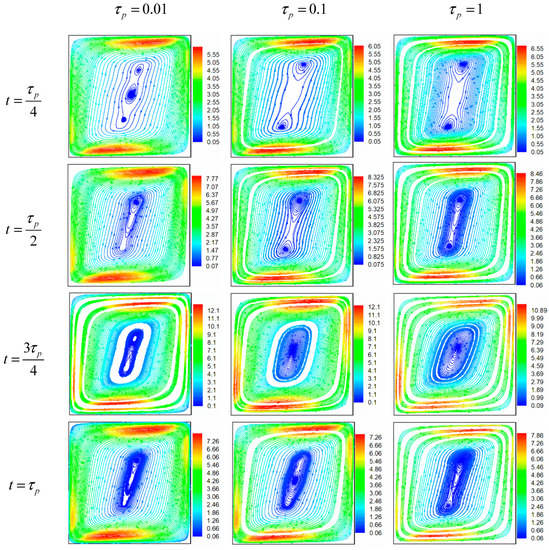

Figure 6 shows the velocity vectors projection at z = 0.5 plan for φ = 0.05, Ha = 25, and A = 0.5 at different times and different oscillation periods. Owing to the magnetic effect, there is a change from a roll structure to a square structure; this conclusion was also mentioned by Al-Najem et al. [31]. It is seen that, for all chosen oscillation periods, the main flow structure changes periodically with time. In fact, vortexes’ merging and division occur during the period for all considered values. Thus, owing to the periodic magnitude of the magnetic field, the flow structure oscillates between one and two central vortexes. In addition to the number of vortexes, their shape also changes with time.

Figure 6.

Streamlines for φ = 0.05, Ha = 25, and A = 0.5.

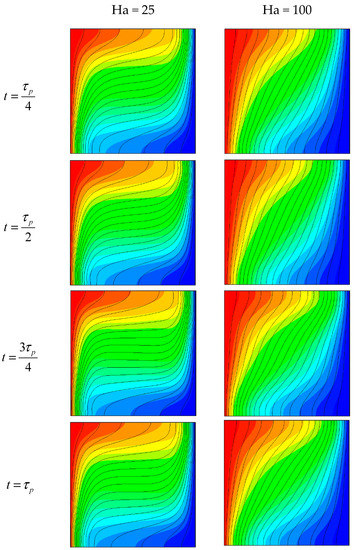

As presented in Figure 7, for higher Hartman numbers (Ha = 100), the merging-division phenomenon persists, but with a flow structure having a slope that approaches the vertical. The flows near the active walls are more attenuated owing to the magnetic damping. This result is also recalled by Ozoe and Okada [29], by mentioning that the induced Lorentz force opposes the flow perpendicular to the direction of the magnetic field. In fact, compared with the Ha = 25 case, in which the maximum values of velocity magnitude are near of the active walls, for Ha = 100, the maximums become near to the top and bottom walls. In opposition with all other values, for when the merging occurs at , the central symmetry disappears, in fact, the vortex is located in the highest region of the enclosure.

Figure 7.

Streamlines for φ = 0.05, Ha = 100, and A = 0.5.

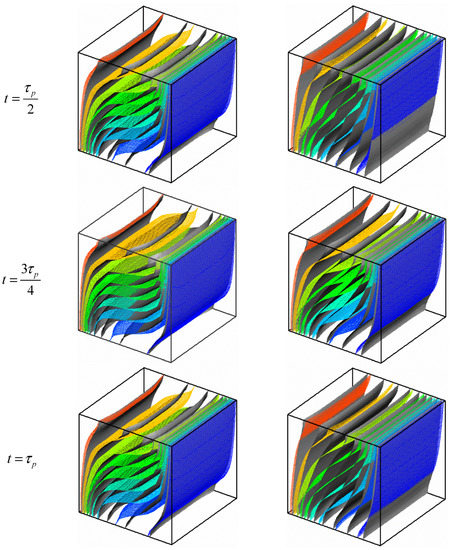

Figure 8 presents a sequence of the temperature field for different Hartmann numbers. The vertical stratification described in Figure 4 is reduced by applying the magnetic (Ha = 50) and, for high values of Hartman number (Ha = 100), the stratification disappears completely. Owing to the suppression of the convective forces opposed by the Lorentz force, the temperature field becomes similar to the conductive regime with an important decrease of the temperature gradients near to the active walls. This conclusion is confirmed by the experimental work of Xu et al. [32]. Owing to their high thermal conductivity, the addition of MWCNT nanoparticles opposes the heat transfer diminution caused by the presence of the magnetic field. Thus, the reduction of the vertical stratification is less pronounced for the case of MWCNT-water compared with pure water. Similarly to the flow structure, the temperature field also changes during the period. For a better understanding of this change, the isotherms at the central plan (Figure 9) for = 1, φ = 0.05, and A = 0.5.

Figure 8.

Isosurfaces of temperature for different Ha and times; φ = 0.05 (multicolour) and φ = 0 (grey).

Figure 9.

Isotherms for different Ha at = 1, φ = 0.05, A = 0.5, black (/4), red (/2), blue (3 /4), and green (); (a) Ha = 50; (b) Ha = 100.

From this figure, it is seen that isotherms are clearly modified with time, especially at the core of the cavity. In fact, near of the active walls, the isotherms are almost similar during the period and different at the core region. It is to be noted that these changes are more pronounced for higher Hartman values owing to the increase of the extremum of the magnitude of the magnetic field.

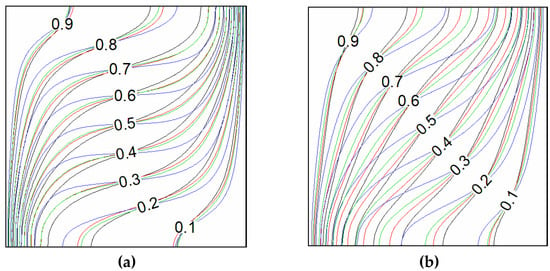

Figure 10 illustrates the effect of adding nanoparticles on isotherms at the central plan for = 0.1 and A = 0.5 (flood (φ = 0.05) and line (φ = 0)). As seen from the figure, that addition of nanoparticle to base fluid has an important effect on temperature distribution. Isotherms become steeper with the increasing Ha number. This means that heat transfer turns to conduction mode. As mentioned above, the isotherms’ structure varies during the period, especially in the central zones for all Hartman values and nanoparticles concentrations.

Figure 10.

Isotherms for = 0.1, A = 0.5 flood (φ = 0.05), and line (φ = 0).

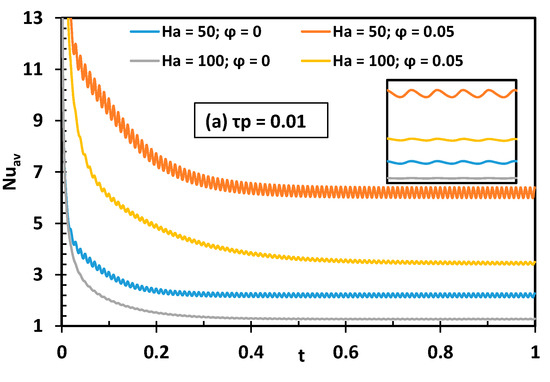

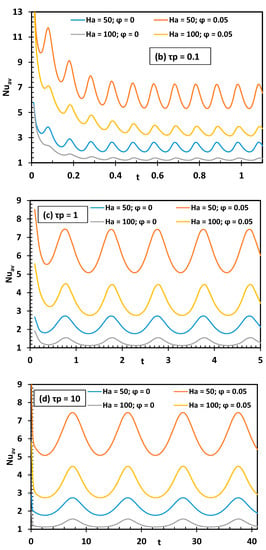

Figure 11 presents the effect of the time-periodic magnetic field magnitude on the average Nusselt number at a certain value of Hartman numbers and nanoparticles volume fraction. As the magnetic field is periodic, it is obvious that the results show the fluctuation in amplitude of the average Nusselt number around a certain value. By decreasing the oscillation period (), the fluctuation decreases, especially for high Hartman values (Figure 11), but it does not become zero. It is to be noted that the average value around which the Nusselt number fluctuates decreases by increasing ; this is an interesting result when the purpose is to reduce the heat transfer. Obviously, the effects of the applied magnetic field and adding nanoparticles are opposite. In fact, the Nusselt number decreases with Ha and increases with φ.

Figure 11.

Temporal evolution of the Nusselt number for different magnetic field oscillation period, Hartmann number, and nanoparticle concentration.

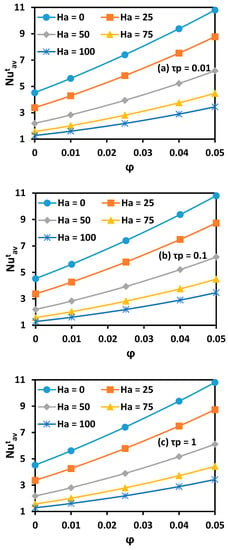

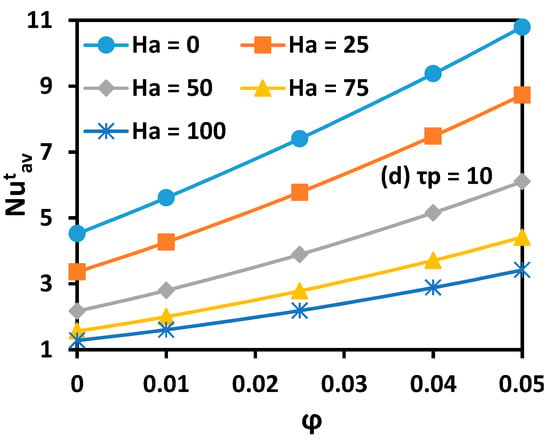

Figure 12 illustrates the effect of nanoparticles volume fraction on the time-averaged Nusselt number () for different Ha and . Firstly, it is noted that the effect of on () is very limited. The applied magnetic field reduces the heat transfer for all values of and Ha. In opposition, owing to the higher thermal conductivity, increasing nanoparticles volume fraction enhances considerably the heat transfer.

Figure 12.

MWCNT volume fraction effect on time averaged Nusselt number ( ) for different Ha and .

5. Conclusions

A computational work was conducted on heat transfer and fluid flow inside a three-dimensional closed space under a variable magnetic field. The main findings are as follows:

- The addition of MWCNT particles enhances the convective heat transfer, increases the vortices’ sizes, and promotes the vertical stratification of the temperature field.

- Lower heat transfer is observed with the increasing Hartmann number and the variation of heat transfer is almost smooth. In other words, oscillation of heat transfer becomes very weak.

- For the same Hartmann number, higher heat transfer and lower amplitude are formed at a higher nanoparticle volume fraction.

Author Contributions

In this paper, L.K., H.F.O. and K.G. conceived and designed the numerical experiments. L.K. and M.A.A. performed the experiments. H.A.M., H.B. and N.A.-H. analyzed the data. H.F.O., K.G. and L.K. wrote the paper.

Funding

This research was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University through the Fast track Research Funding Program.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

| Magnetic field () | |

| Be | Bejan number |

| Cp | Specific heat at constant pressure (J/kg·K) |

| Dimensionless electric field | |

| Direction of magnetic field | |

| g | Gravitational acceleration (m/s2) |

| Dimensionless density of electrical current | |

| k | Thermal conductivity (W/m.K) |

| l | Enclosure width |

| n | Unit vector normal to the wall |

| Dimensionless local generated entropy | |

| Nu | Local Nusselt number |

| Pr | Prandtl number |

| Ra | Rayleigh number |

| t | Dimensionless time () |

| T | Dimensionless temperature [ |

| Cold temperature (K) | |

| Hot temperature (K) | |

| To | Bulk temperature [To = (c + h)/2] |

| Dimensionless velocity vector () | |

| x, y, z | Dimensionless Cartesian coordinates (, , ) |

| Greek symbols | |

| Thermal diffusivity (m2/s) | |

| Thermal expansion coefficient (1/K) | |

| Density (kg/m3) | |

| Dynamic viscosity (kg/m.s) | |

| Kinematic viscosity (m2/s) | |

| Dimensionless electrical potential | |

| Nanoparticle volume fraction | |

| Electrical conductivity | |

| Dimensionless vector potential () | |

| Dimensionless vorticity () | |

| Dimensionless temperature difference | |

| Subscripts | |

| av | Average |

| c | Cold |

| h | Hot |

| fr | Friction |

| f | Fluid |

| n | Normal |

| nf | Nanofluid |

| s | Solid (nanoparticle) |

| x, y, z | Cartesian coordinates |

| Superscript | |

| ′ | Dimensional variable |

References

- Jaafar, M.; Gomez-Herrero, J.; Gil, A.; Ares, P.; Vazquez, M.; Asenjo, A. Variable-field magnetic force microscopy. Ultramicroscopy 2009, 109, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izadi, M.; Mohebbi, R.; Delouei, A.A.; Sajjadi, H. Natural convection of a magnetizable hybrid nanofluid inside a porous enclosure subjected to two variable magnetic fields. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2019, 151, 154–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatami, M.; Zhou, J.; Geng, J.; Jing, D. Variable magnetic field (VMF) effect on the heat transfer of a halfannulus cavity filled by Fe3O4-water nanofluid under constant heat flux. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2018, 451, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, A.; Khan, M. Unsteady mixed convective flow of Williamson nanofluid with heat transfer in the presence of variable thermal conductivity and magnetic field. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 260, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikholeslami, M.; Vajravelu, K. Nanofluid flow and heat transfer in a cavity with variable magnetic field. Appl. Math. Comput. 2017, 298, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandeep, N.; Animasaun, I.L. Heat transfer in wall jet flow of magnetic-nanofluids with variable magnetic field. Alex. Eng. J. 2017, 56, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatami, M.; Khazayinejad, M.; Jing, D. Forced convection of Al2O3–water nanofluid flow over a porous plate under the variable magnetic field effect. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2016, 102, 622–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.A.; Khan, A.; Shuaib, M. On the study of flow between unsteady squeezing rotating discs with cross diffusion effects under the influence of variable magnetic field. Heliyon 2018, 4, e00925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimmagadda, R.; Haustein, H.D.; Asirvathamb, L.G.; Wongwises, S. Effect of uniform/non-uniform magnetic field and jet impingement on the hydrodynamic and heat transfer performance of nanofluids. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2019, 479, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, M.S.; Hegazi, A.A.; Mousa, M.G. Combined effect of pulsating flow and magnetic field on thermoelectric cooler performance. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2019, 13, 100403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kefayati, G.H.R. Lattice Boltzmann simulation of MHD natural convection in a nanofluid-filled cavity with sinusoidal temperature distribution. Powder Technol. 2013, 243, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Salem, K.; Oztop, H.F.; Pop, I.; Varol, Y. Effects of moving lid direction on MHD mixed convection in a linearly heated cavity. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2012, 55, 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.R.; Zhang, R.P.; Rong, Y.; Zhi, X.Q.; Qiu, L.M. Interferometric study of the heat and mass transfer during the mixing and evaporation of liquid oxygen and nitrogen under non-uniform magnetic field. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 136, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvandi, A. Film boiling of magnetic nanofluids (MNFs) over a vertical plate in presence of a uniform variable-directional magnetic field. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2016, 406, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nessab, W.; Kahalerras, H.; Fersadou, B.; Hammoudi, D. Numerical investigation of ferrofluid jet flow and convective heat transfer under the influence of magnetic sources. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 150, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraj, E.N.; Shaiq, S. Instigated magnetic field effect on carbon nanotubes suspensions encompassing variable thermophysical characteristics. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2019, 132, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, M.M.; Ellahi, R.; Zeeshan, A. Study of variable magnetic field on the peristaltic flow of Jeffrey fluid in a non-uniform rectangular duct having compliant walls. J. Mol. Liq. 2016, 222, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandy, S.K.; Mahapatra, T.R.; Pop, I. Unsteady separated stagnation-point flow over a moving porous plate in the presence of a variable magnetic field. Eur. J. Mech. B Fluids 2015, 53, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikholeslami, M.; Vajravelu, K.; Rashidi, M.M. Forced convection heat transfer in a semi annulus under the influence of a variable magnetic field. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2016, 92, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Luo, J.; Chen, Z.; Mei, G.; Yan, L.-E. Measuring the albedo of limited-extent targets without the aid of known-albedo masks. Sol. Energy 2018, 171, 971–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rashed, A.A.A.; Kalidasan, K.; Kolsi, L.; Aydi, A.; Malekshah, E.H.; Hussein, A.K.; Kanna, P.R. Three-Dimensional Investigation of the Effects of External Magnetic Field Inclination on Laminar Natural Convection Heat Transfer in CNT–Water Nanofluid Filled Cavity. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 252, 454–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rashed, A.A.A.; Kolsi, L.; Oztop, H.F.; Aydi, A.; Malekshah, E.H.; Abu-Hamdeh, N.; Borjini, M.N. 3D magneto-convective heat transfer in CNT-nanofluid filled cavity under partially active magnetic field. Phys. E Low Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2018, 99, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rashed, A.; Kolsi, L.; Kalidasan, K.; Malekshah, E.H.; Borjini, M.N.; Kanna, P.R. Second law analysis of natural convection in a CNT-Water Nanofluid filled inclined 3D Cavity with incorporated Ahmed Body. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2017, 130, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rashed, A.A.A.; Aich, W.; Kolsi, L.; Mahian, O.; Hussein, A.K.; Borjini, M.N. Effects of movable-baffle on heat transfer and entropy generation in a cavity saturated by CNT suspensions: Three dimensional modeling. Entropy 2017, 19, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolthers, M.H.G.; Duits, D.; van den Ende, J. Mellema. Shear history dependence of aggregated colloidal dispersions. Rheology 1996, 40, 799–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, M.M. Viscosity-concentration-shear rate relations for suspensions. Rheol. Acta 1975, 14, 402–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halelfadl, S.; Estellé, P.; Aladag, B.; Doner, N.; Maré, T. Viscosity of carbon nanotubes water based nanofluids: Influence of concentration and temperatureInt. J. Sci. 2013, 71, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, C.W.; Liu, G.; Lin, Y.; Li, M. Interface effect on thermal conductivity of carbon nanotube composites. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004, 85, 3549–3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozoe, H.; Okada, K. The Effect of the Direction of the External Magnetic Field on the Three-Dimensional Natural Convection in a Cubical Enclosure. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1989, 32, 1939–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanshahi, M.; Hosseinizadeh, S.F.; Alipanah, M.; Dehghani, A.; Vakilinejad, G.R. Numerical simulation of free convection based on experimental measured conductivity in a square cavity using Water/SiO2 nanofluid.Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2010, 37, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Najem, N.M.; Khanafer, K.M.; El-Refaee, M.M. Numerical Study of Laminar Natural Convection in Tilted Enclosure with Transverse Magnetic Field. Int. J. Numer. Meth. Heat Flow 1998, 8, 651–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Li, B.Q.; Stock, E. An Experimental Study of Thermally Induced Convection of Molten Galliumin Magnetic Fields. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2006, 49, 2009–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikholeslami, M. New computational approach for exergy and entropy analysis of nanofluid under the impact of Lorentz force through a porous media. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2019, 344, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikholeslami, M. Numerical approach for MHD Al2O3-water nanofluid transportation inside a permeable medium using innovative computer method. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2019, 344, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikholeslami, M. Application of Darcy law for nanofluid flow in a porous cavity under the impact of Lorentz forces. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 266, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikholeslami, M. Finite element method for PCM solidification in existence of CuO nanoparticles. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 265, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikholeslami, M. Solidification of NEPCM under the effect of magnetic field in a porous thermal energy storage enclosure using CuO nanoparticles. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 263, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikholeslami, M.; Omid, M. Enhancement of PCM solidification using inorganic nanoparticles and an external magnetic field with application in energy storage systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 963–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikholeslami, M.; Haq, R.; Shafee, A.; Li, Z.; Elaraki, Y.G.; Tlili, I. Heat transfer simulation of heat storage unit with nanoparticles and fins through a heat exchanger. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 135, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikholeslami, M.; Haq, R.; Shafee, A.; Li, Z. Heat transfer behavior of Nanoparticle enhanced PCM solidification through an enclosure with V shaped fins. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 130, 1322–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikholeslami, M.; Shehzad, S.A.; Li, Z.; Shafee, A. Numerical modeling for Alumina nanofluid magnetohydrodynamic convective heat transfer in a permeable medium using Darcy law. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 127, 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikholeslami, M.; Li, Z.; Shafee, A. Lorentz forces effect on NEPCM heat transfer during solidification in a porous energy storage system. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 127, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikholeslami, M.; Jafaryar, M.; Saleem, S.; Li, Z.; Shafee, A.; Jiang, Y. Nanofluid heat transfer augmentation and exergy loss inside a pipe equipped with innovative turbulators. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 126, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikholeslami, M.; Ghasemi, A.; Li, Z.; Shafee, A.; Saleem, S. Influence of CuO nanoparticles on heat transfer behavior of PCM in solidification process considering radiative source term. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 126, 1252–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikholeslami, M.; Darzi, M.; Li, Z. Experimental investigation for entropy generation and exergy loss of nano-refrigerant condensation process. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 125, 1087–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikholeslami, M.; Shehzad, S.A.; Li, Z. Water based nanofluid free convection heat transfer in a three dimensional porous cavity with hot sphere obstacle in existence of Lorenz forces. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 125, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikholeslami, M.; Jafaryar, M.; Li, Z. Nanofluid turbulent convective flow in a circular duct with helical turbulators considering CuO nanoparticles. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 124, 980–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikholeslami, M.; Ghasemi, A. Solidification heat transfer of nanofluid in existence of thermal radiation by means of FEM. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 123, 418–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikholeslami, M.; Shehzad, S.A. CVFEM simulation for nanofluid migration in a porous medium using Darcy model. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 122, 1264–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikholeslami, M.; Seyednezhad, M. Simulation of nanofluid flow and natural convection in a porous media under the influence of electric field using CVFEM. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 120, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikholeslami, M.; Rokni, H.B. Numerical simulation for impact of Coulomb force on nanofluid heat transfer in a porous enclosure in presence of thermal radiation. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 118, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikholeslami, M.; Shehzad, S.A. Numerical analysis of Fe3O4-H2O nanofluid flow in permeable media under the effect of external magnetic source. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 118, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).