Abstract

We analyzed the behavior of a “Solar Wall” and validated the apparatus using three nanofluids (silver, titanium dioxide, and a hybrid compound) based on their photothermal conversion performance. The factors considered were the temperature gain in relation to the base fluid, the stored energy, and the specific absorption rate. A cost analysis was conducted to assess the cost associated with energy generation for each nanofluid. Five concentrations were studied for each nanofluid. A hybrid nanofluid formed by the previous ones was also tested. The results show that the Solar Wall demonstrates repeatability, indicating it is suitable for testing other nanofluids. The silver and hybrid nanofluids performed better; the former achieved a temperature increase of 10.2 °C relative to the base fluid, and the latter reached 9.9 °C. Regarding energy gain, the silver-based sample achieved 31.93%, and the hybrid sample achieved 34.52%. The SAR values for the silver nanCheckedofluid were higher than those for the titanium-based; the cost to generate an energy unit using the former was higher than in the titanium case. The silver-based and hybrid nanofluids obtained showed improved photothermal conversion, making them the most promising options.

1. Introduction

Environmental concerns have intensified in recent decades, driven largely by the environmental impacts associated with fossil fuel use. The generation of energy from conventional sources has resulted in environmental degradation, as evidenced by pollution levels, acid rain, and global warming [1]. Due to this problem, the search for renewable energy has increased significantly in recent years, making it an area of study for scientists and professionals [2]. One of the notable renewable energy sources is solar energy, which has applications both for converting solar energy into electrical (photovoltaic) energy and for converting solar energy into thermal energy, which thereafter can be applied for heating fluids for domestic and industrial use or electrical energy generation by power cycles.

The use of thermal energy to heat fluids occurs through solar collectors, where collector efficiency is a parameter of study that is often limited [3,4,5]. Conventional fluids used in solar systems are limited in capacity and thermal properties, so the use of nanofluids can be considered to address this issue [6]. Nanofluids are constituted by nanoparticles dispersed in a base fluid with a size ranging from 1 nm to 100 nm. Recent results have shown that characteristics such as thermal conductivity, viscosity, thermal diffusivity, and heat transfer coefficient are improved compared to those of conventional fluids [7]. Nanoparticles can be made of several materials, such as metals, non-metals, oxides, carbides, mixtures of nanoparticles (hybrid fluids), etc. [8,9,10].

Recent research on nanofluids has demonstrated their superiority over conventional fluids, showing that they have strong heat transfer potential [11]. A study that applied a silver nanofluid to an evacuated tube solar collector showed a 40% increase in efficiency [12]. Another study on a ribbed flat-plate solar collector showed a 10% increase in collector efficiency [2]. Zinc oxide increased the efficiency of a U-tube solar collector by 62.87% [13]. A new category of nanofluids, called hybrid nanofluids, consists of two or more types of nanoparticles dispersed within a base fluid. Recent research has revealed that the hybrid nanofluids have been increasingly outperforming ordinary nanofluids, thus enhancing their thermal properties when dispersed in the base fluid.

Graphene oxide and gold formed a hybrid solution that increased steam generation efficiency by 10.8% [14]. The hybrid nanofluid TiO2-MWCNT achieved a maximum increase in thermal conductivity of 34.31% [7]. The ternary nanoparticles rGO-Fe3O4-TiO2 showed an improvement in thermal conductivity of 13.3% [15]. Fe3O4/SiO2 improved the efficiency of a solar collector by 21.7% [16], and the thermal conductivity using SWCNTs-MgO increased by 35% at a temperature of 50 °C [17]. Other research has also shown that nanofluids exhibit higher thermal conductivity than the base fluid [18,19,20,21].

Another practical limitation associated with conventional solar collectors is the efficiency with which energy is transferred to the fluid. In this context, studies were conducted on direct absorption solar collectors (DASC), in which the fluid directly absorbs solar energy, thereby mitigating this efficiency limitation. A balance was observed between temperature and power gain in DASC, with an efficiency of 55% reported without major losses in temperature gain [22], and an efficiency of 40% for direct steam generation using gold nanofluids [23]. Works characterized the use of nanofluids, such as TiO2, and reviewed the properties of other nanofluids, including Ag (silver) and ZnO (zinc oxide) [24,25,26].

Given recent research efforts to characterize nanofluids, this work built, field-tested, and analyzed an apparatus called “Solar Wall” to evaluate its potential to provide a more consistent framework for testing different types of nanofluids under direct radiation absorption. In this Solar Wall, several concentrations of silver nanofluid, titanium dioxide, and a hybrid compound were used to verify, in a uniform manner, whether the results for photothermal conversion capacity were consistent with those reported in the literature. One of the main focuses was to validate the Solar Wall layout’s suitability for this task. Temperature gains relative to the base fluid, total stored energy, and the specific absorption rate per unit of mass (SAR) were measured and analyzed. In addition, the work estimated the production cost per energy unit (kW) for each tested nanoparticle. This study presents and validates an experimental setup for consistently and reproducibly evaluating nanofluids under direct solar irradiation. While much of the existing literature focuses on enhancing the performance of specific nanofluid formulations or collector configurations, the present work addresses the need for improved experimental consistency in direct-absorption solar research. The setup is used to compare silver-, titanium dioxide–based, and hybrid Ag/TiO2 nanofluids using common performance indicators, including temperature rise, stored thermal energy, and specific absorption rate. An economic analysis is also conducted to relate thermal performance to material cost. The observed repeatability across experimental campaigns indicates that the proposed methodology provides a sound basis for future investigations of direct-absorption solar energy systems.

2. Materials and Methods

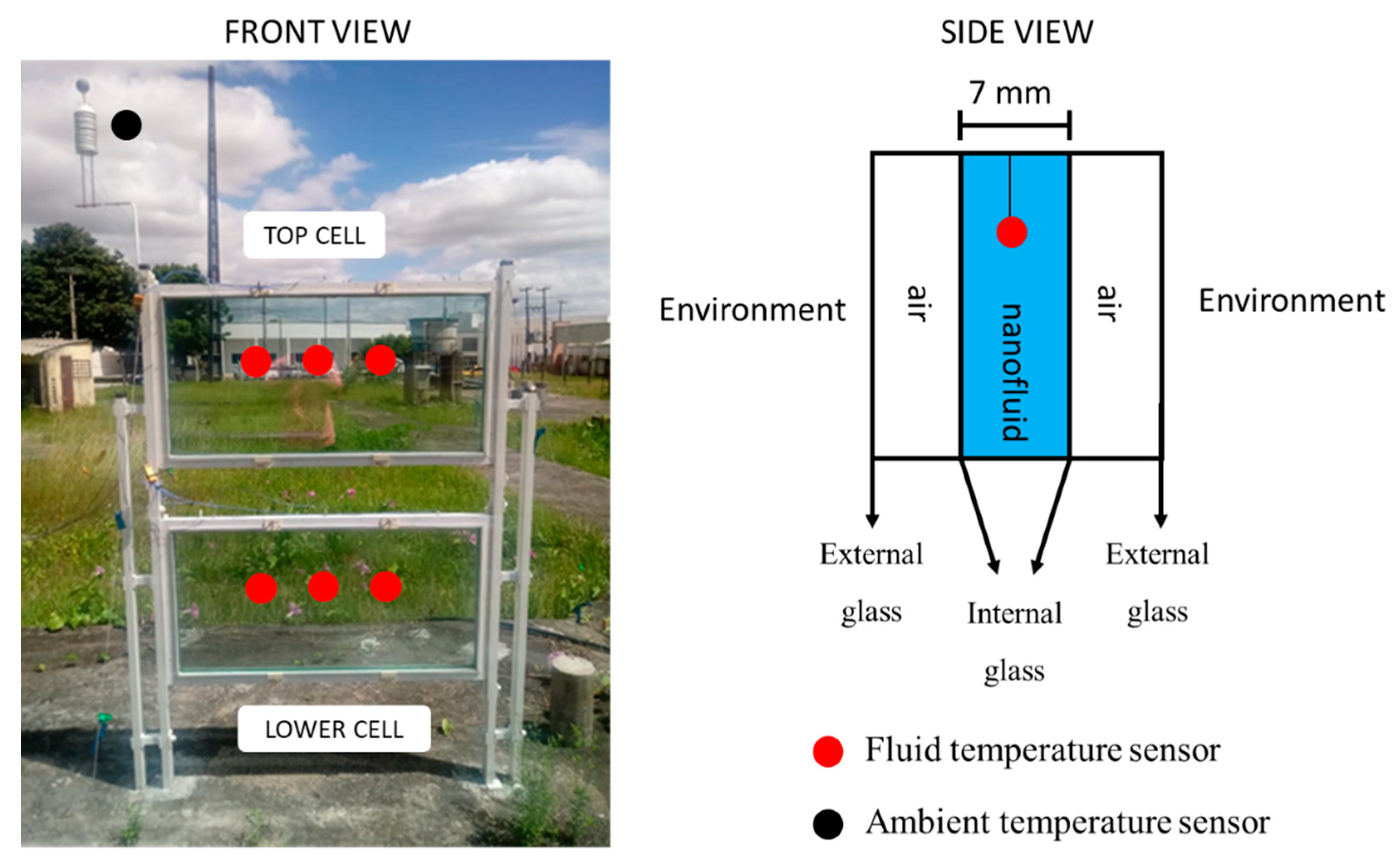

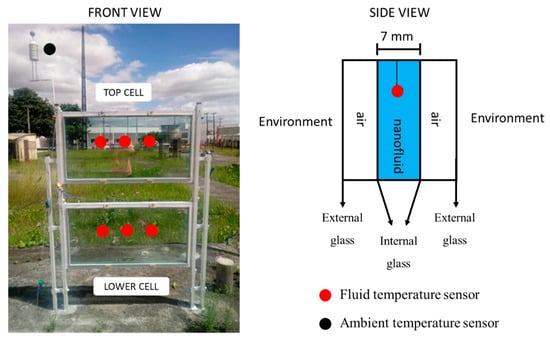

Figure 1 shows an experimental apparatus called “Solar Wall”, which was designed and built to enable uniform comparison of the performance of different nanofluids. Similar devices are available for analyzing nanofluids [3], and, in this regard, our intention was to use them as a model to standardize the performance values obtained. The bench consisted of an aluminum structure with glass cells at the bottom and the top; each cell had two windows of tempered glass, and the nanofluid occupied a volume of 3.5 L. The dimensions of the glasses were as follows: 8 mm thick, 1000 mm long, and 500 mm high. To minimize convection losses, two additional glasses were inserted into each cell, with the external glasses 4 mm thick. A white paint coating was applied to the aluminum structure to prevent it from heating and, consequently, from influencing the cell temperature. In addition, steel cables supported the structure.

Figure 1.

Solar Wall proposed for data acquisition. On the left, a picture of the mounted system is shown, whereas on the right, a schematic of the side view is depicted. The circles indicate the positions of the temperature sensors.

2.1. Data Acquisition

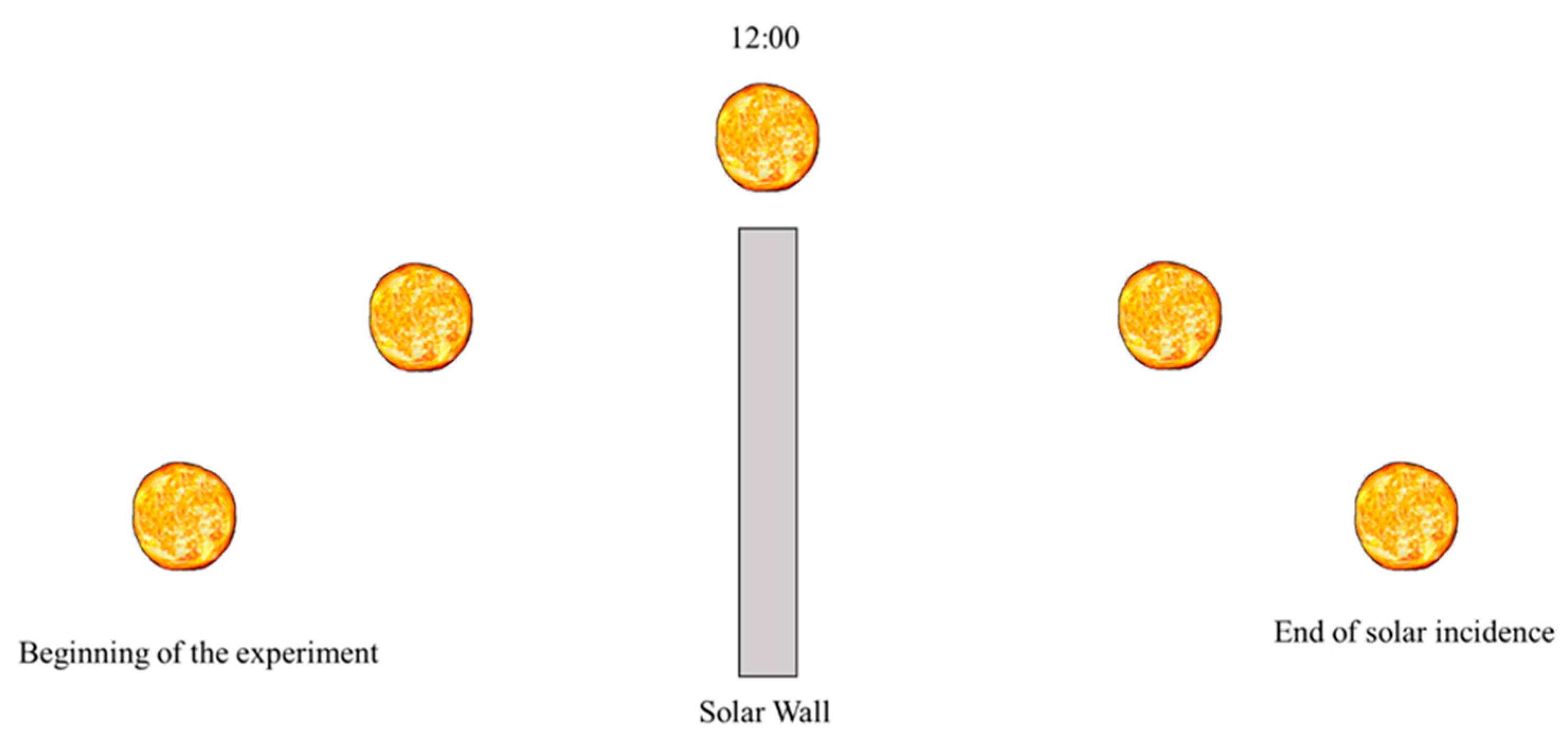

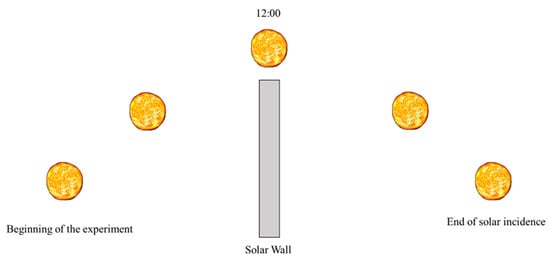

During the experiments, six type K thermocouples were used. They had 0.1 °C accuracy and a 2 Hz sampling frequency. They were calibrated in a thermostatic bath against a glass thermometer. Three thermocouples were placed in the lower cell, and the other three in the corresponding positions in the upper cell. They were equally spaced and fixed with resin supports. The recorded temperature was the arithmetic mean of the three measurements in each cell. For data acquisition, an OMEGA RX12 Datalogger (OMEGA Engineering, Inc., Norwalk, CT, USA) was used. The experiments were carried out at the Solar Energy and Natural Gas Laboratory (LESGN) of the Federal University of Ceará in the city of Fortaleza (Latitude: 03°43′02″ S, Longitude: 38°32′35″ W) 20 June 2019 and 16 October 2019. Measurements were taken from 5:30 a.m. to 9:30 p.m., the period during which a detectable temperature difference between the nanofluid and distilled water persisted. The experimental apparatus had one side facing east and the other facing west, so that solar radiation before and after noon penetrated the cells, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic side view of the solar incidence during the test hours (5:30–9:30 pm).

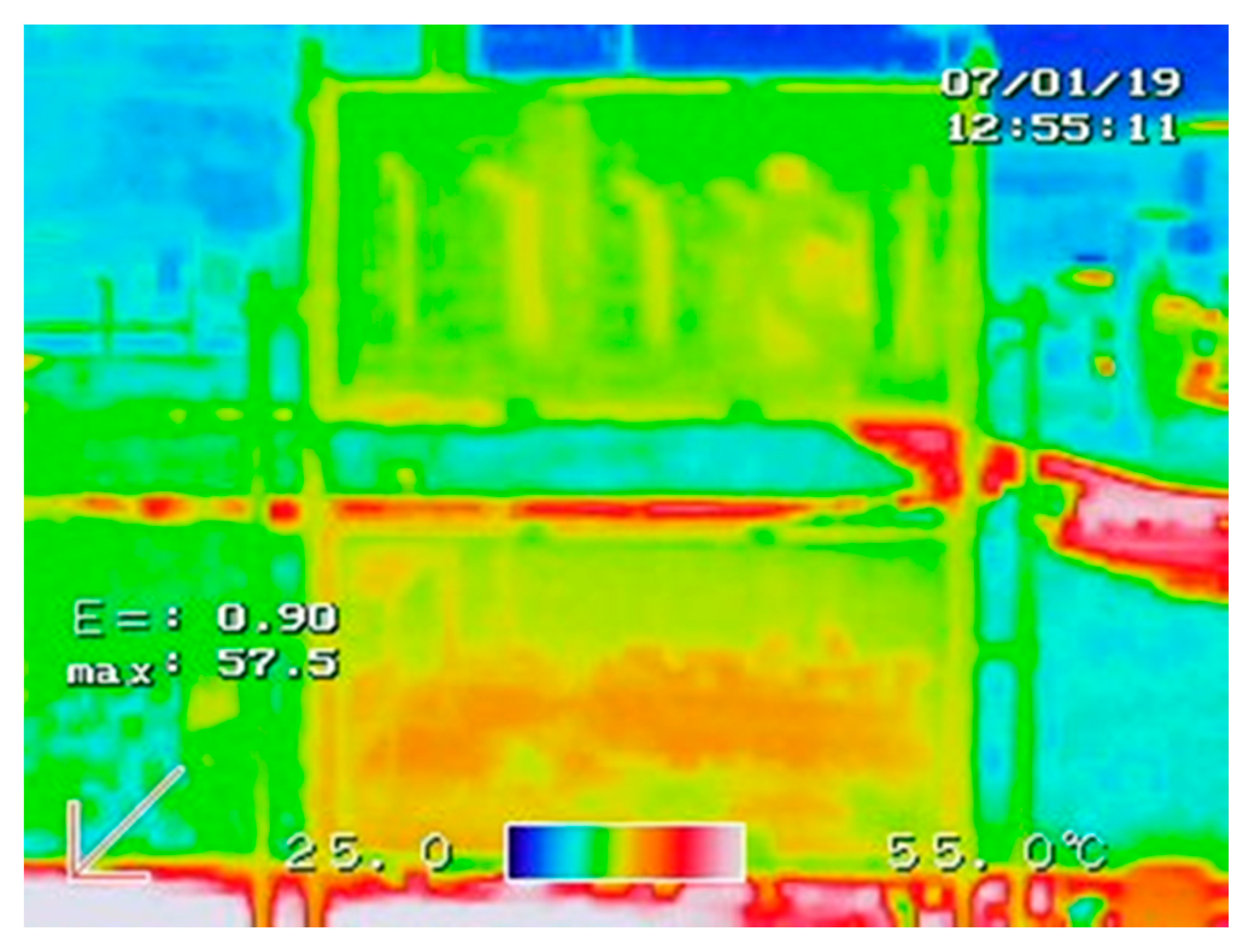

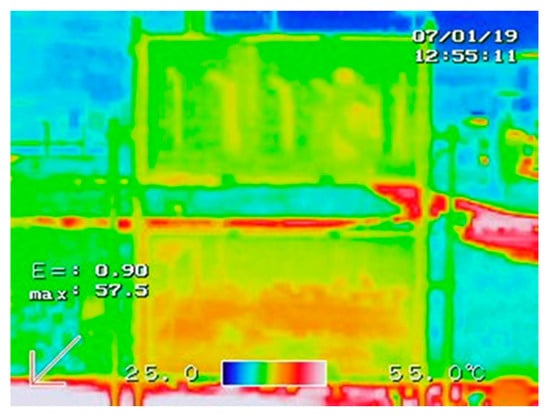

The temperature distribution across the glass surfaces was also verified to correct for any positional deviation in the measured temperatures and thus improve the reliability of the data obtained. A higher temperature was recorded in the lower glasses due to the reflection of the sun’s rays from the ground, as shown in Figure 3. Several tests were conducted with only the base fluid in the two cells to develop a correction equation that equalizes the temperature curves at each test instant. The effect was corrected by polynomial regression (), so that the temperature curves of the lower and upper glasses were then consistent.

Figure 3.

Temperature profile on the glass surface (blue for lower temperatures, red for higher temperatures, as shown in the center-bottom label). A small difference can be observed between the upper (colder) and lower (hotter) cells. A correction equation was developed.

2.2. Characterization of the Nanofluids

The experiments were carried out using water-based nanofluids of silver and titanium dioxide (TiO2) at several concentrations. The titanium dioxide nanofluid was obtained by dispersing TiO2 nanoparticles in water using ultrasound. The methodology for preparing the nanofluid is described in more detail in references [8,27]. In contrast, the production of silver nanofluid involves the chemical reduction of silver nitrate to form the nanoparticles within the nanofluid itself. Five concentrations of silver and titanium dioxide nanofluids were studied, as shown in Table 1. TiO2 was chosen for its ability to absorb heat in solar panels and other properties that make it a good fit for this application, as found in the literature [26].

Table 1.

Concentrations of the studied nanofluids.

Nanofluids with the same concentration (ppm) have different volume proportions (v/v) due to differences in density, but for comparison, it was preferable to use equal molar concentrations. Also seeking to improve the performance of the nanofluids, an analysis of hybrid nanofluids made of silver and titanium was carried out, where the titanium nanoparticle (23.2 ppm) was doped with the increase in several amounts of silver (0.40625; 0.8125; 1.625; 3.25), corresponding to the molar fractions of 3%, 6%, 12% and 25% respectively. The quantity of titanium dioxide remained fixed, since previous experiments showed the superiority of silver. In this sense, we applied the best concentration of titanium with silver increments. Table 2 details these samples. The concentration of 23.2 ppm was chosen to optimize the experiments. Due to the stability of this concentration, the dilution would also be stable.

Table 2.

Studied samples of the hybrid nanofluid.

3. Results

3.1. Temperature Gain of Nanofluids

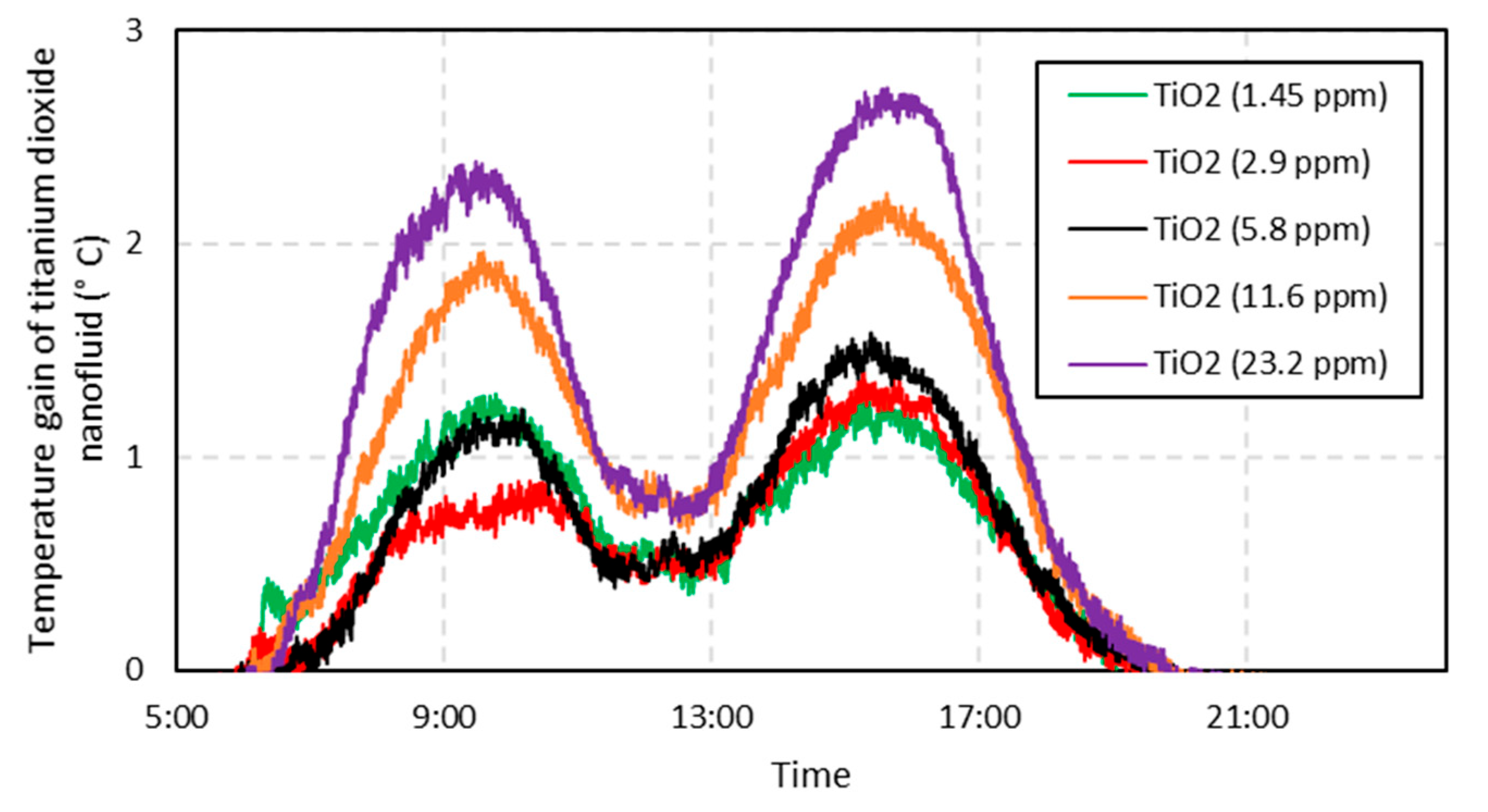

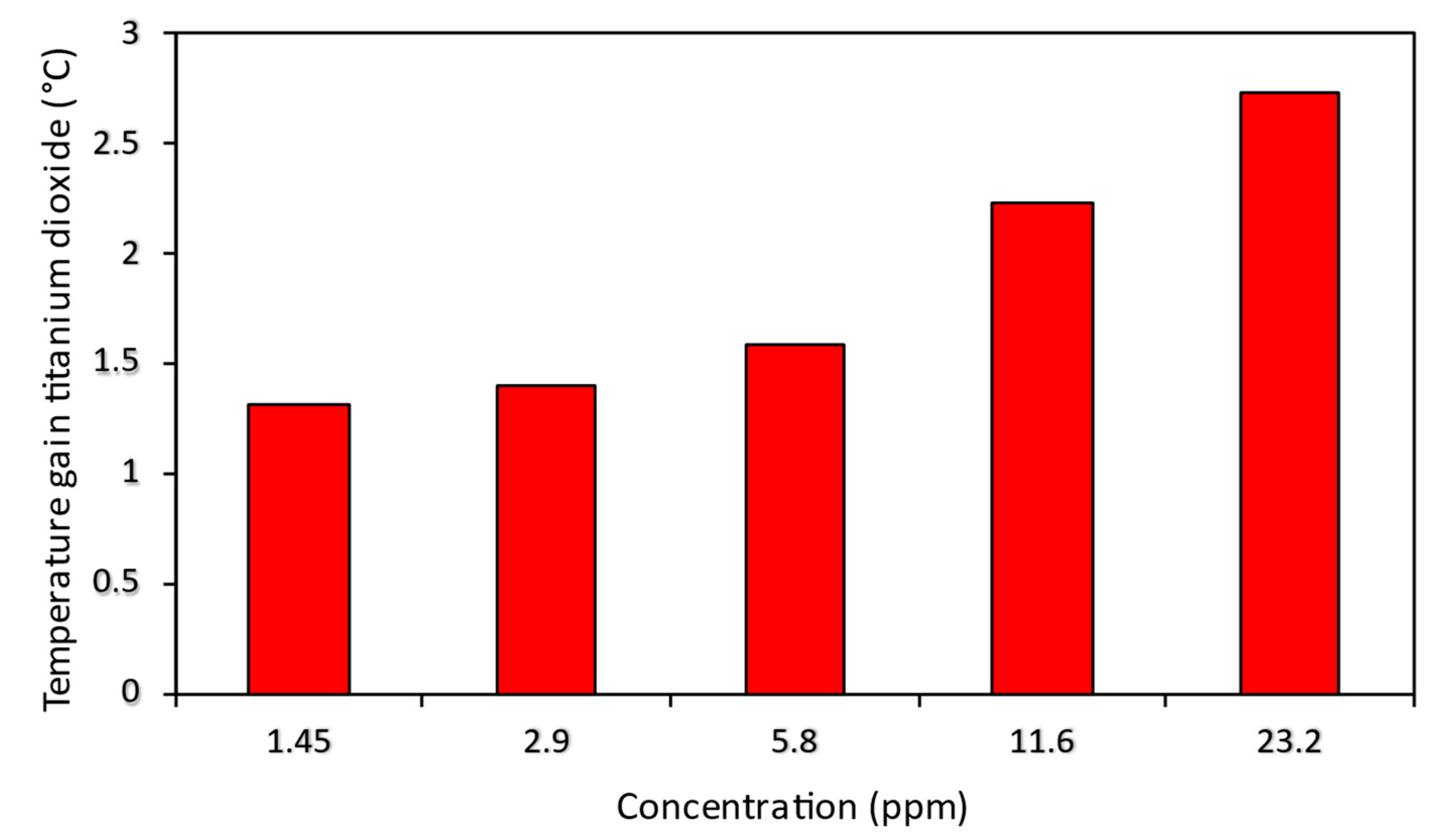

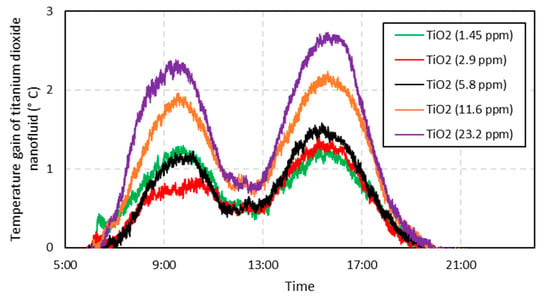

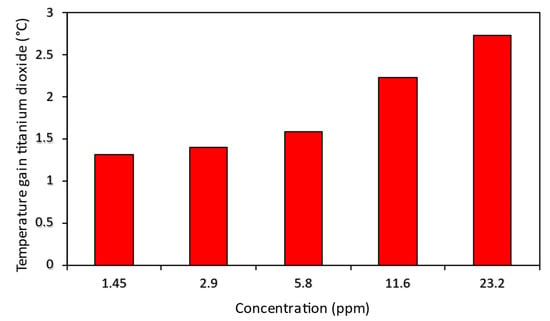

An analysis was conducted to determine the nanofluid’s temperature increase relative to the base fluid during the experiment. Figure 4 shows the temperature gains of the titanium dioxide nanofluid compared to water. The temperature profile shows an upward trend until 12:00, followed by a drop, as the angle of incidence of the solar rays on the Solar Wall approaches near-parallel, causing the drop. In the second half of the day, the temperature profile returns to normal behavior and presents similar values. Figure 5 shows the maximum gain for each TiO2 nanofluid concentration, indicating that higher nanoparticle concentration yields greater gain. The 23.2 ppm concentration showed a 2.7 °C increase (5%), i.e., an advantage with a relatively small magnitude, since the 1.45 ppm nanofluid shows a comparable gain. This limited relative improvement suggests not using the 23.2 concentration, since the 1.45 ppm concentration already yields similar gains, and the expense of nanoparticles is lower. The comparison with the silver nanofluid will provide even more justification for this choice. One of the limiting factors that may have caused the low temperature gain of this nanofluid is its white color, which may be responsible for the partial reflection of the sun’s rays, even though it presents a higher thermal conductivity than water. Some studies also found that TiO2 nanofluids were not as promising for direct absorption, consistently yielding inferior results compared with other nanofluids [28,29].

Figure 4.

Temperature gain of the titanium dioxide nanofluid compared to the base fluid. The values are referenced absolutely to the base fluid. It is observed that the system’s thermal inertia is evident to the right of the lines (after 5:30 p.m.), since almost no direct radiation reaches the apparatus after this time.

Figure 5.

Maximum temperature gains relative to the base fluid of the titanium dioxide nanofluid for each one-day test. Very high concentrations were tested, and they did not outperform the smallest value by the same proportion.

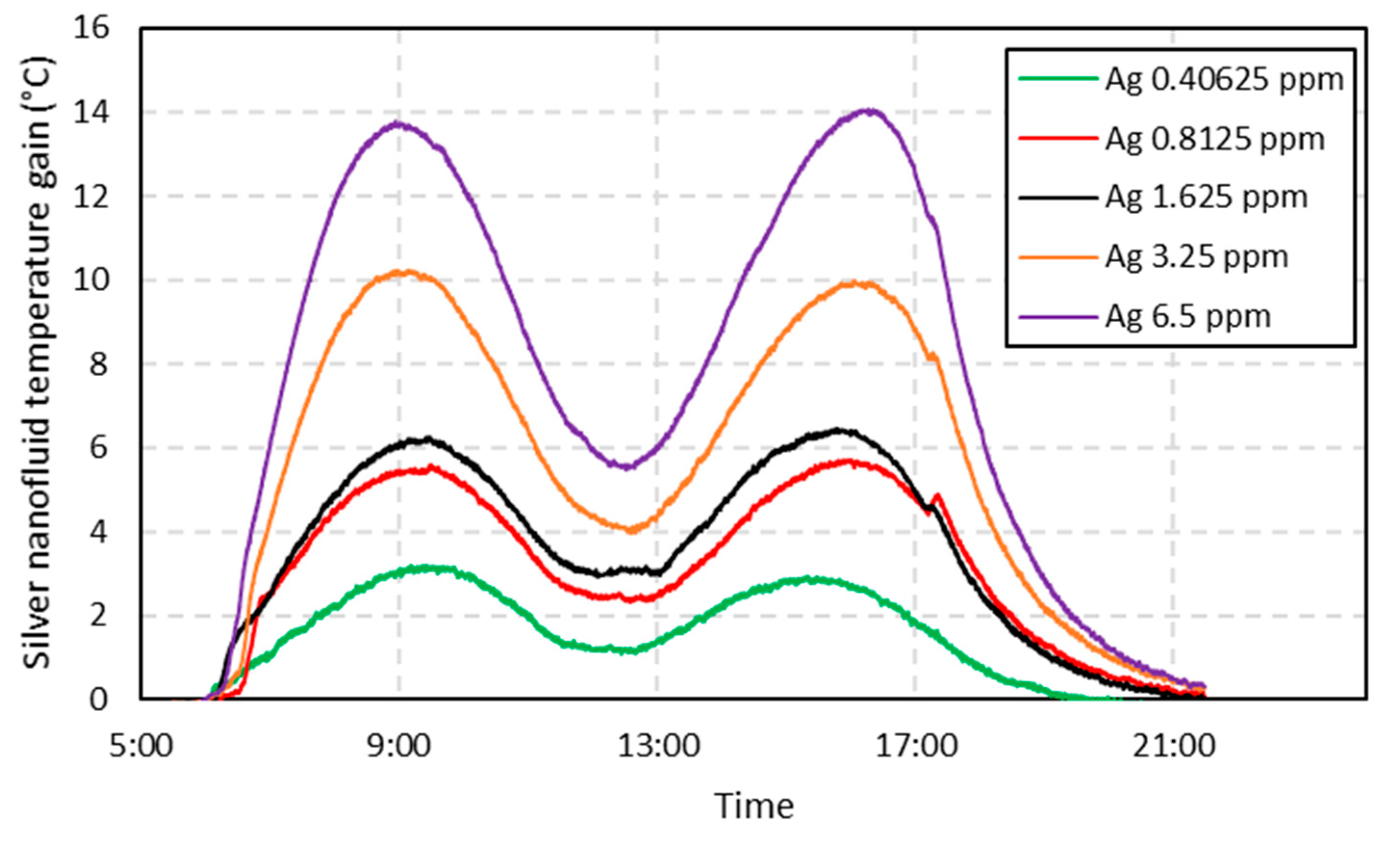

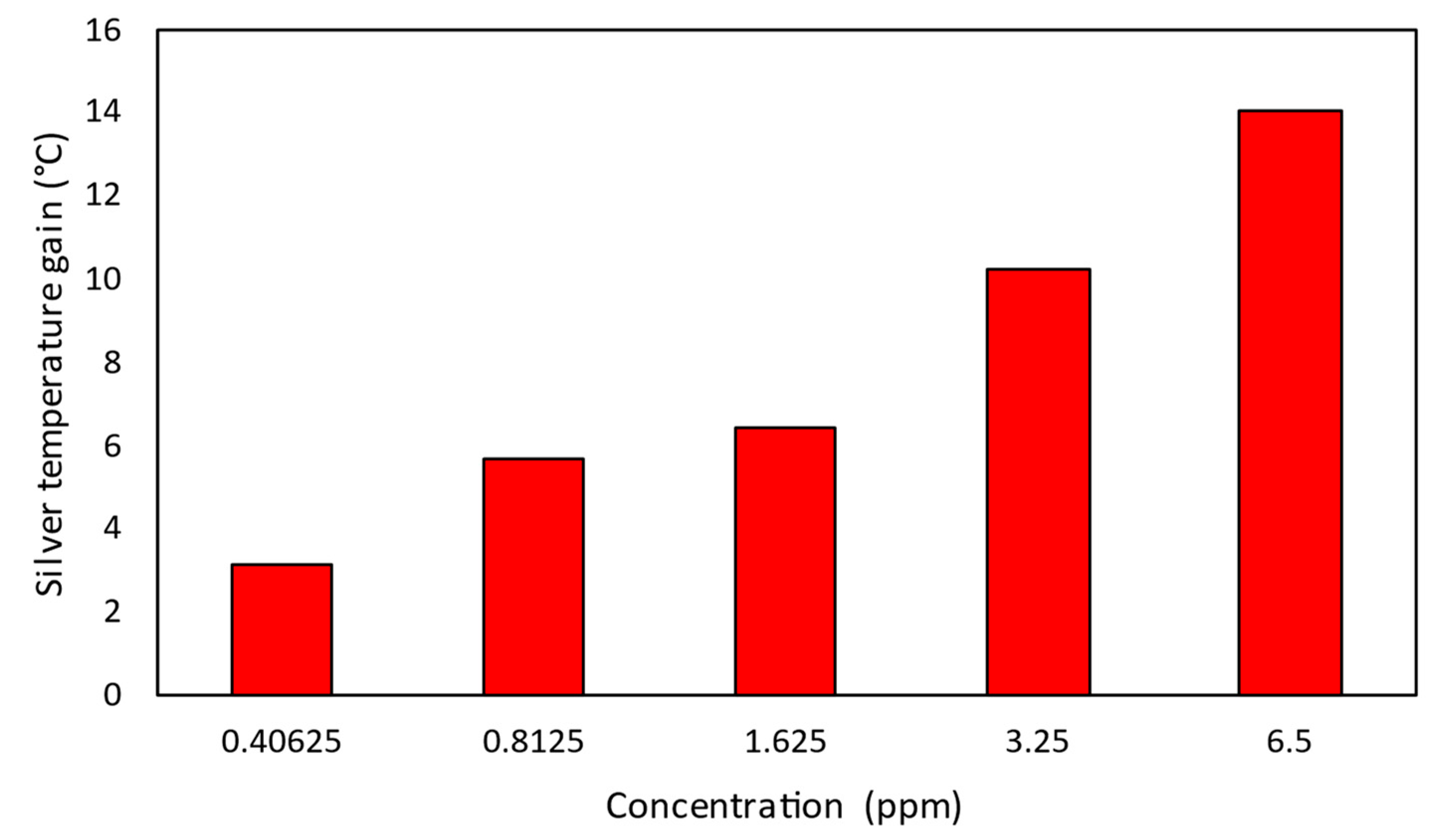

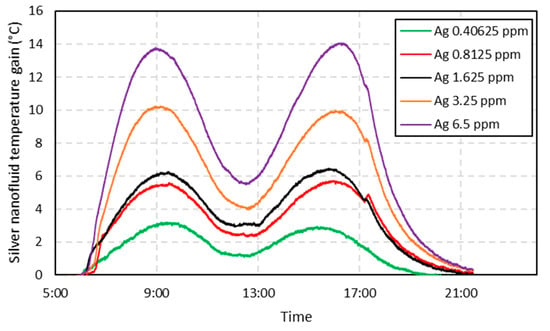

The same analysis was carried out for the silver nanofluids, and the resulting temperature profiles are comparable. A strong correlation between nanoparticle concentration and temperature gain is observed, as can be seen in Figure 6. Silver nanofluids have reached energy gains well above titanium nanofluids, showing a maximum gain of 14 °C (26% gain compared to the base fluid) for a 6.5 ppm concentration (Figure 7). The gains from silver nanofluids with increasing concentration were also very pronounced. In this analysis, the strong influence of nanoparticle concentration on the temperature increase implies that, in both cases, the higher the concentration, the greater the energy gain. For other authors, silver also yielded satisfactory results. In [3], the authors found that silver nanofluids increased stored energy by 144%.

Figure 6.

Temperature gain of the silver nanofluids compared to the base fluid, for a one-day test. Each curve represents a different test concentration.

Figure 7.

Maximum temperature gain of the silver nanofluid for each one-day test.

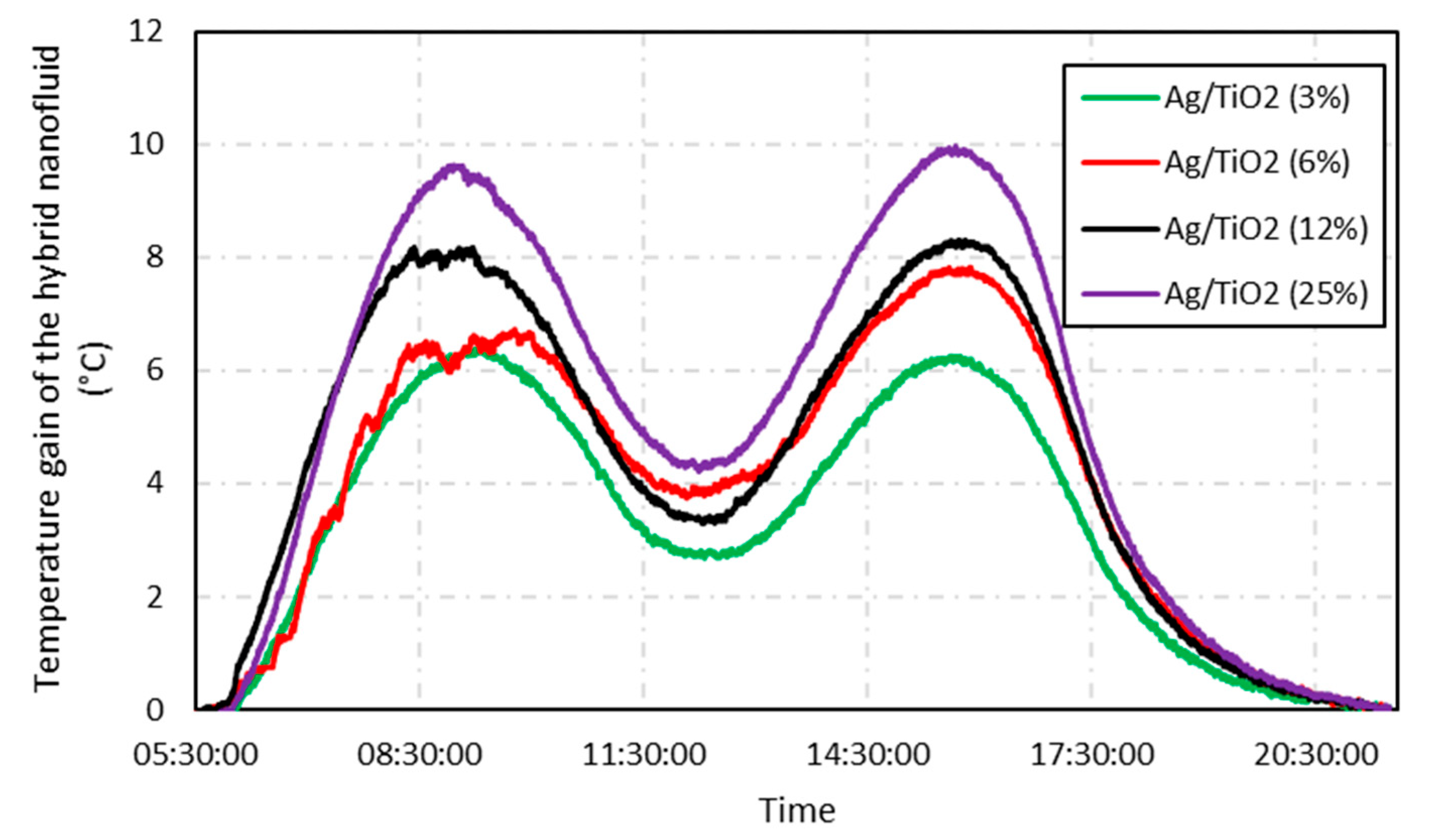

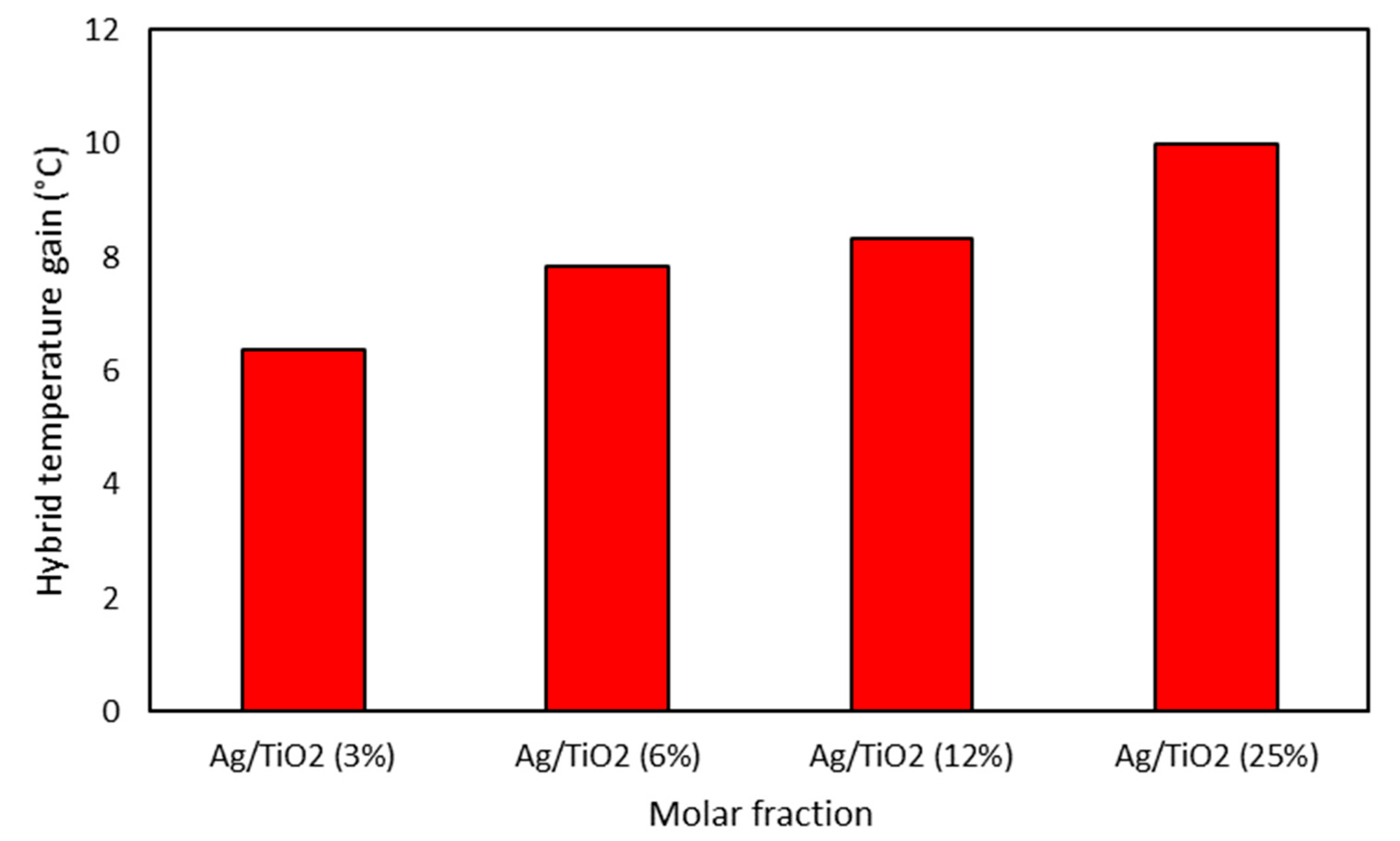

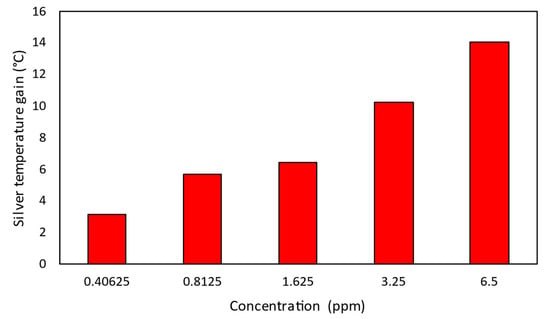

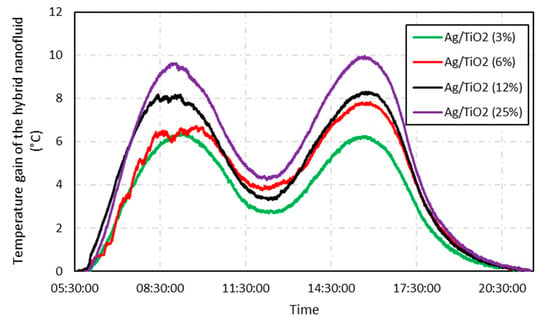

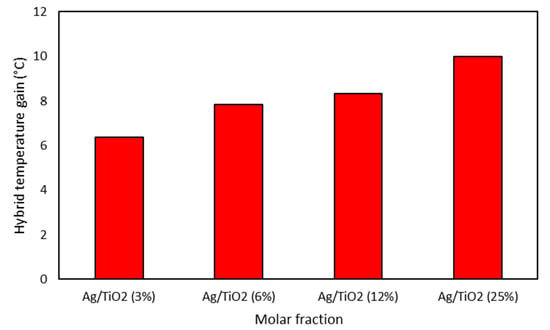

Figure 8 presents a similar analysis for the hybrid nanofluid, and, once again, the same temperature profile shape was observed compared with the isolated nanofluids, demonstrating the high repeatability of the Solar Wall in collecting temperature data. The titanium nanoparticle concentration was fixed at 23.2 ppm, and the nanofluids were doped with a doubling of the silver nanoparticle concentration (0.4025, 0.8125, 1.625, 3.25 ppm). As a result, the hybrid nanofluid with a 25% molar fraction achieved a gain of 9.9 °C, an improvement of 18.3% over the base fluid. Figure 9 shows the behavior of the hybrid nanofluid: the higher the silver content relative to the titanium nanoparticles, the greater the temperature increase, which is a prominent factor in this work. Notably, this gain exceeds the algebraic sum of the isolated gains from silver and titanium dioxide nanofluids.

Figure 8.

Temperature gain of the hybrid nanofluid compared to the base fluid, for a one-day test. Each curve represents a different test concentration.

Figure 9.

Maximum temperature gain of the hybrid nanofluid for each one-day test.

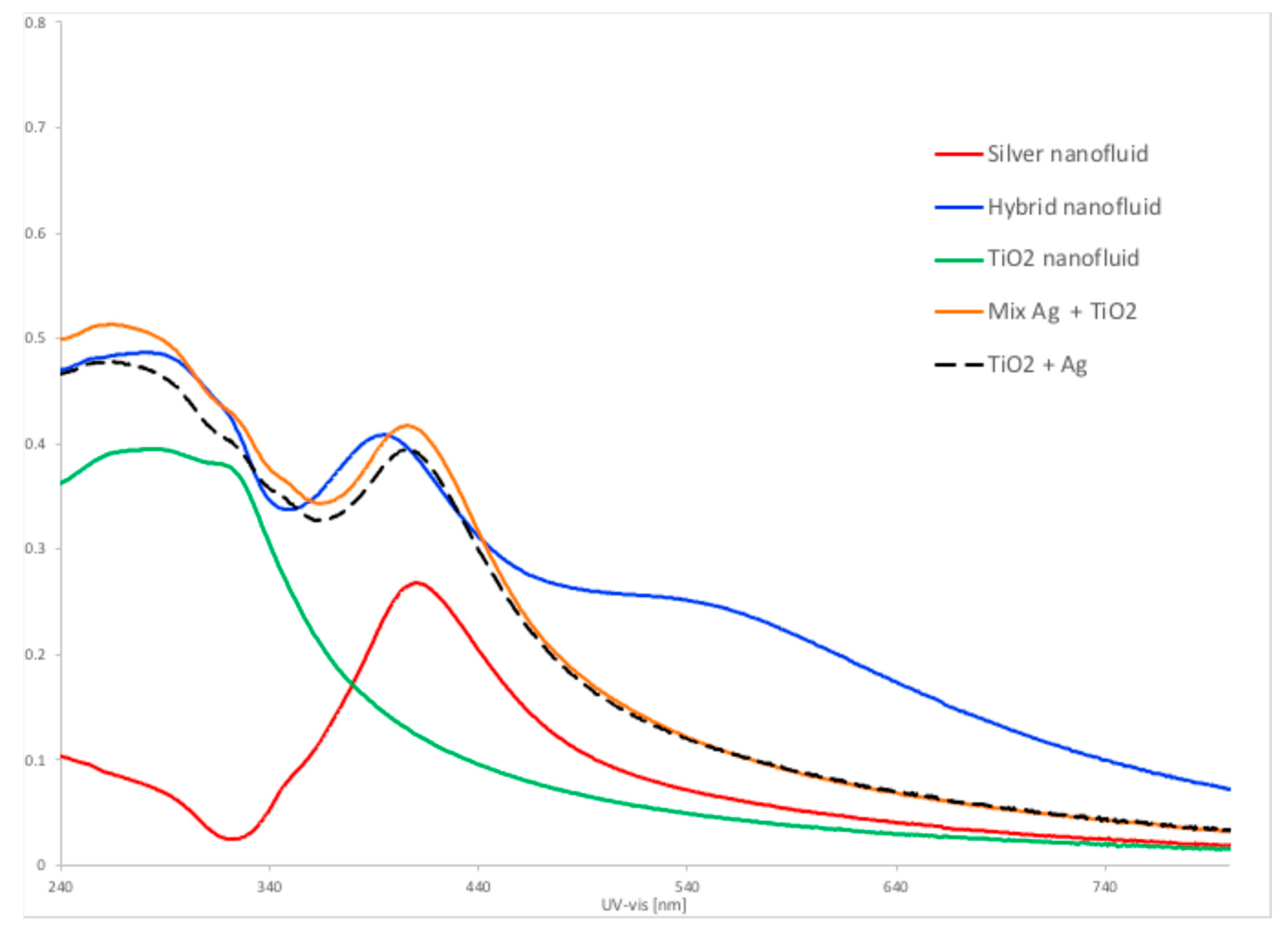

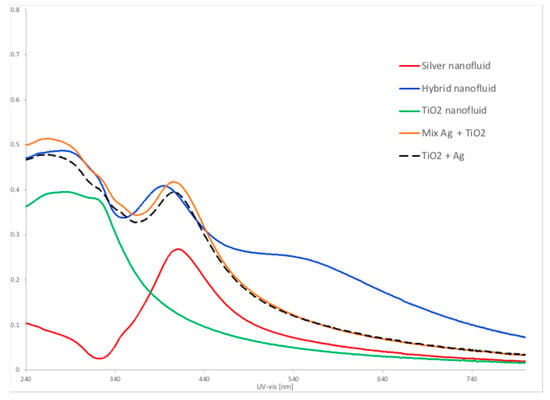

These findings can be explained because the hybrid fluid is not a mixture of two nanoparticles, i.e., Ag + TiO2, in the water-based fluid. Instead, the silver nanoparticles are formed onto TiO2 nanoparticles dispersed in water by chemical reduction of silver nitrate. These approaches cause a significant difference in the ultraviolet light absorption spectra of the fluids.

Figure 10 shows a laboratory experiment in which four types of nanofluids, namely silver, titanium oxide, a mixture of these two nanofluids, and a hybrid Ag/TiO2 nanofluid, were analyzed by UV-VIS. The silver nanofluid exhibits a peak at 415 nm (red line), while the TiO2 spectrum shows a broad band from 240 to 280 nm (green line). A mixture of these two nanofluids in the same proportion as the hybrid fluid results in a curve (orange line) that closely matches the calculated algebraic sum of the two separate spectra (dashed black lines). In contrast, the hybrid Ag/TiO2 nanofluid exhibits an absorption curve (blue line) that, in addition to the two characteristic bands of TiO2 and Ag, shows a new broad band between 480 nm and 740 nm, not observed in the original fluids or in their mixture. This indicates that new nanoparticles form a composite of both species. As a result, light absorption is enhanced across a broader spectral range. The absorption observed for TiO2 is as expected, since this wavelength range is where the band gap of the electronic structure of this oxide is usually found. When Ag and TiO2 are mixed, a “red shift” occurs, that is, a slight displacement of the curve toward the visible spectrum. Peaks in the ultraviolet that were absent when Ag was pure can be observed. These peaks are especially due to the influence of titanium dioxide in the mixture, since it is known to absorb in the UV range of the light spectrum.

Figure 10.

UV-VIS spectra of Silver nanofluid (red line), Titanium oxide nanofluid (green line), mixture of Ag and TiO2 nanofluids, Silver/Titanium oxide hybrid nanofluid (blue line), and the algebraic sum of the Silver nanofluid and Titanium oxide nanofluid curves (dashed black curve).

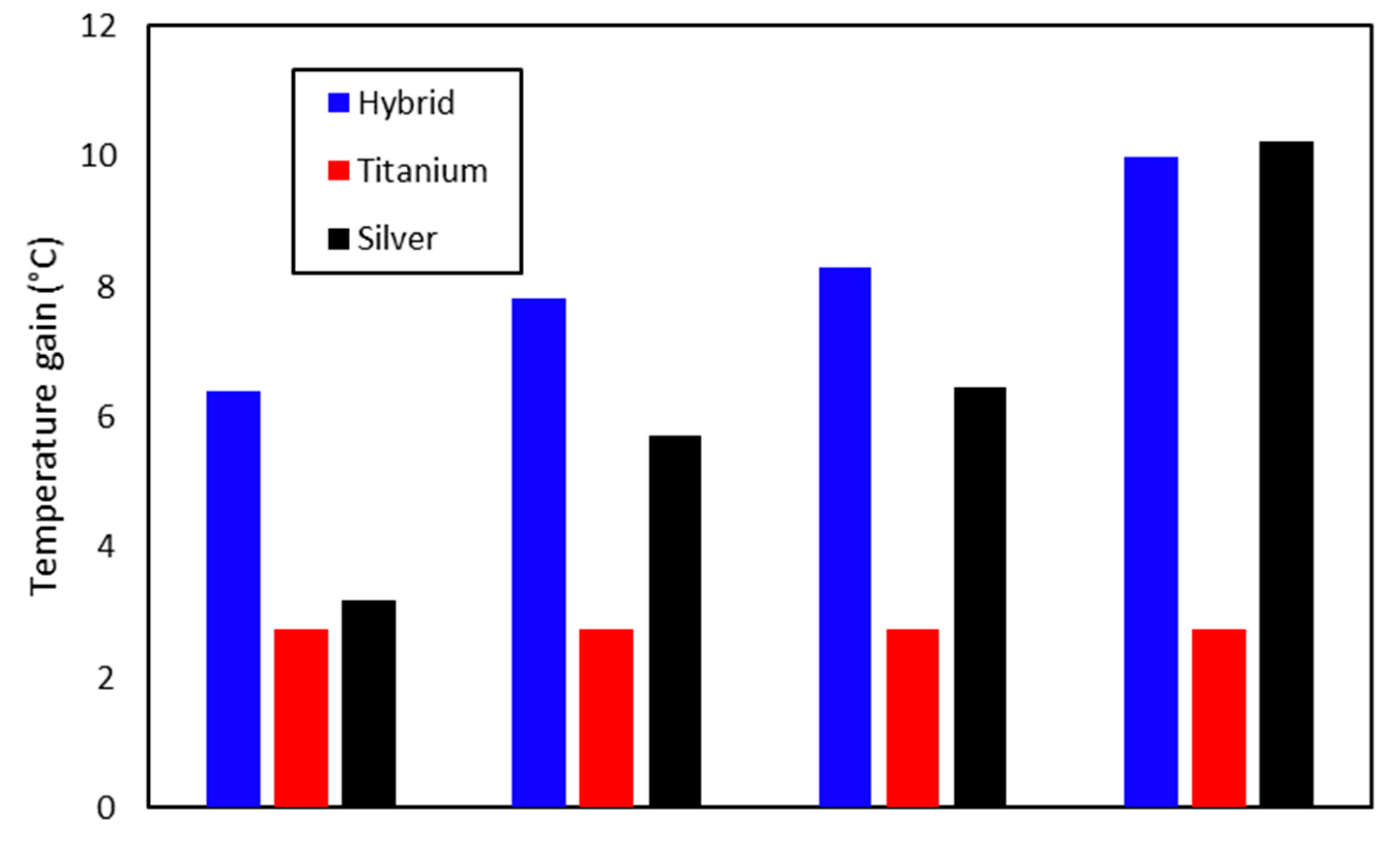

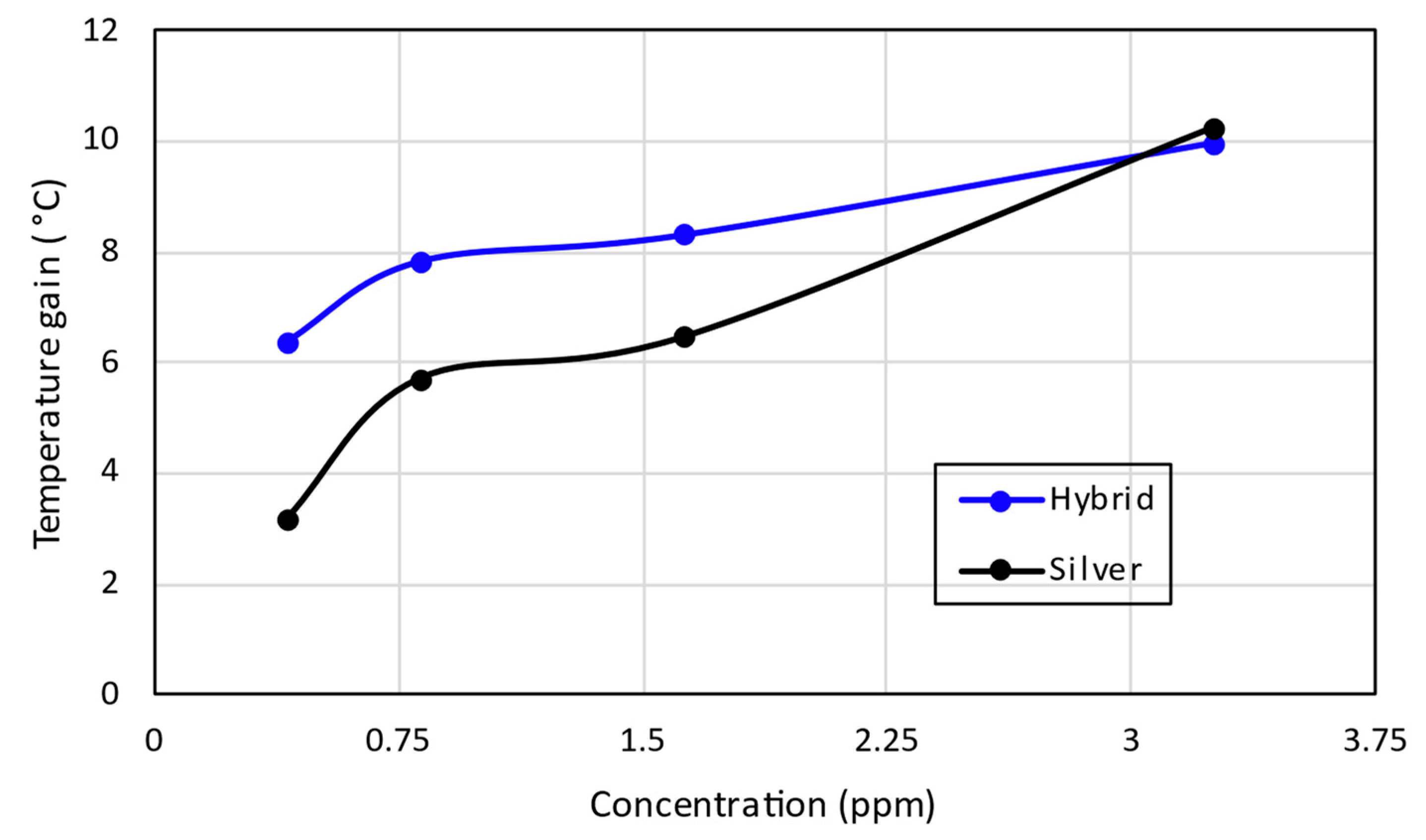

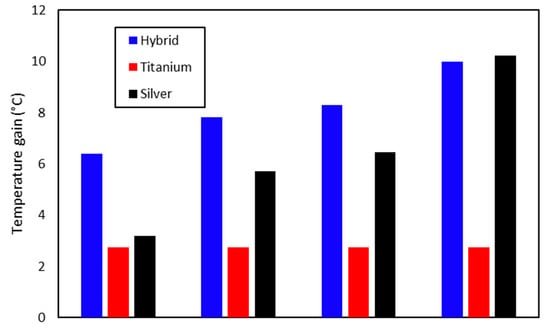

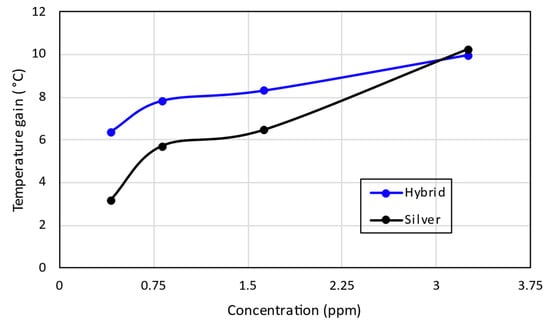

A comparison was made of the three situations involved in the tests with the solar wall. Figure 11 shows the maximum temperature gain for each molar fraction of the hybrid and the corresponding concentrations of silver and titanium dioxide nanofluids. It is observed that the hybrid nanofluid has a significantly higher gain than silver and titanium at a 3% molar fraction. Nevertheless, the silver nanofluid shows greater differential gains with increasing concentration, eventually achieving higher temperature gains than the hybrid nanofluid. Figure 12 shows that the 3.5 ppm silver nanofluid achieved a temperature increase of 10.2 °C, while the hybrid nanofluid reached 9.9 °C. Therefore, it is possible to infer the unfeasibility (regarding the temperature gain) of the hybrid nanofluid for higher silver concentrations. The lower gain for the TiO2 can be explained by the very low absorption that this fluid has based on the UV spectra; there are no peaks in the visible light or in the infrared of the sunlight spectra.

Figure 11.

Comparison of the three tests performed on the solar wall using silver nanofluids (0.4025 ppm, 0.8125 ppm, 1.625 ppm and 3.5 ppm), titanium dioxide (23.2 ppm) and the hybrid nanofluid.

Figure 12.

Comparison of the hybrid nanofluid temperature gain against the silver nanofluid as a function of the tested concentrations.

The heat gains observed for the Ag-TiO2 mixture can be explained by the presence of UV peaks and the red shift shown in Figure 10. The mixture appears to have more absorption peaks across a wider range of the light spectrum than the pure Ag, especially in the ultraviolet.

3.2. Total Energy Stored

The total energy stored in the nanofluids was calculated during the heating period:

where and are the mass, specific heat, and temperature, and the subscript refers to the nanofluid.

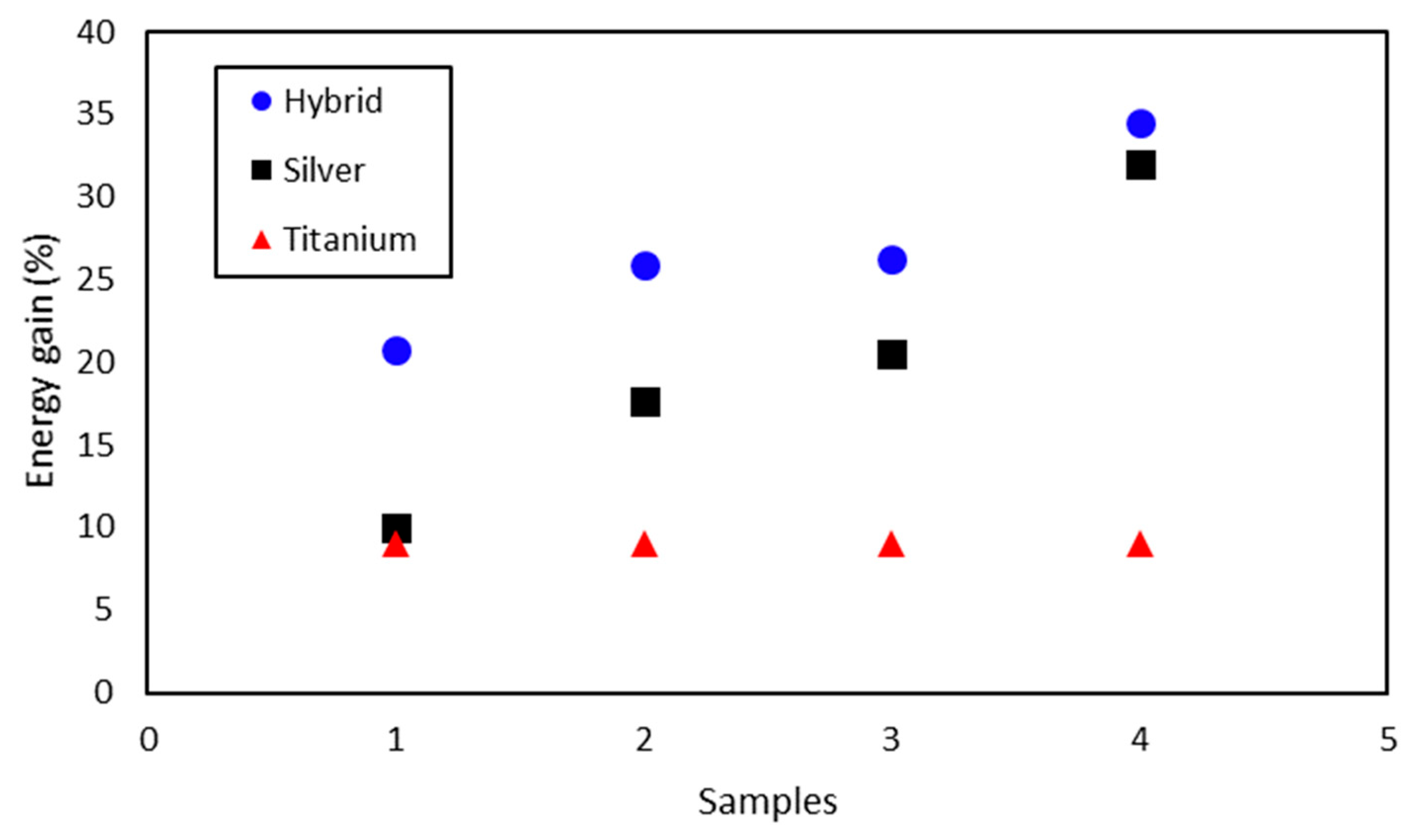

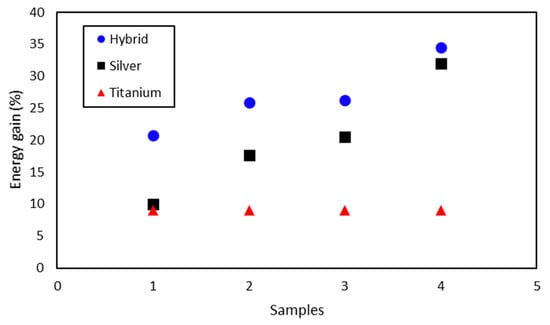

The energy gain for each tested nanofluid was calculated relative to the base fluid, and the results are shown in Figure 13. The four samples of the hybrid nanofluid were compared with the silver and titanium dioxide nanofluids. The hybrid nanofluid consistently achieved a higher energy gain across all samples, while the titanium dioxide nanofluid showed gains much lower than the other nanofluids. The silver nanofluid showed a relatively small energy gain, but increasing its concentration brought results closer to those of the hybrid, with the most concentrated silver nanofluid showing an energy gain of 31.93% compared to the base fluid, while the hybrid achieved 34.52% (e.g., titanium dioxide achieved 9.04%). These results again demonstrate the effectiveness of the solar wall, with the hybrid nanofluid’s superior performance expected and confirmed compared to isolated nanofluids, even at relatively low concentrations.

Figure 13.

Percentage of energy gain of the samples for the three nanofluids under study.

According to [27], the amount of water used in the tests was much higher than the amount of solutes, which diminished the influence of the solutes’ properties. Further details on the properties of TiO2, such as viscosity and surface tension, and how they relate to its function as a nanofluid for heat transfer can be found in [30].

3.3. Economic Viability Evaluation

The cost of applications using nanofluids should also be considered, as it plays a crucial role in industrial analysis. This study examined the performance-related costs of nanofluids, estimating how nanoparticle prices relate to their ability to produce thermal energy. Specifically, the research investigated the cost associated with generating one unit of thermal energy [31]:

in this evaluation, the specific absorption rate per unit mass is given by:

where represents mass, is specific heat, is temperature, and is time. The subscripts , and represent the base fluid, nanofluid, and nanoparticle, respectively.

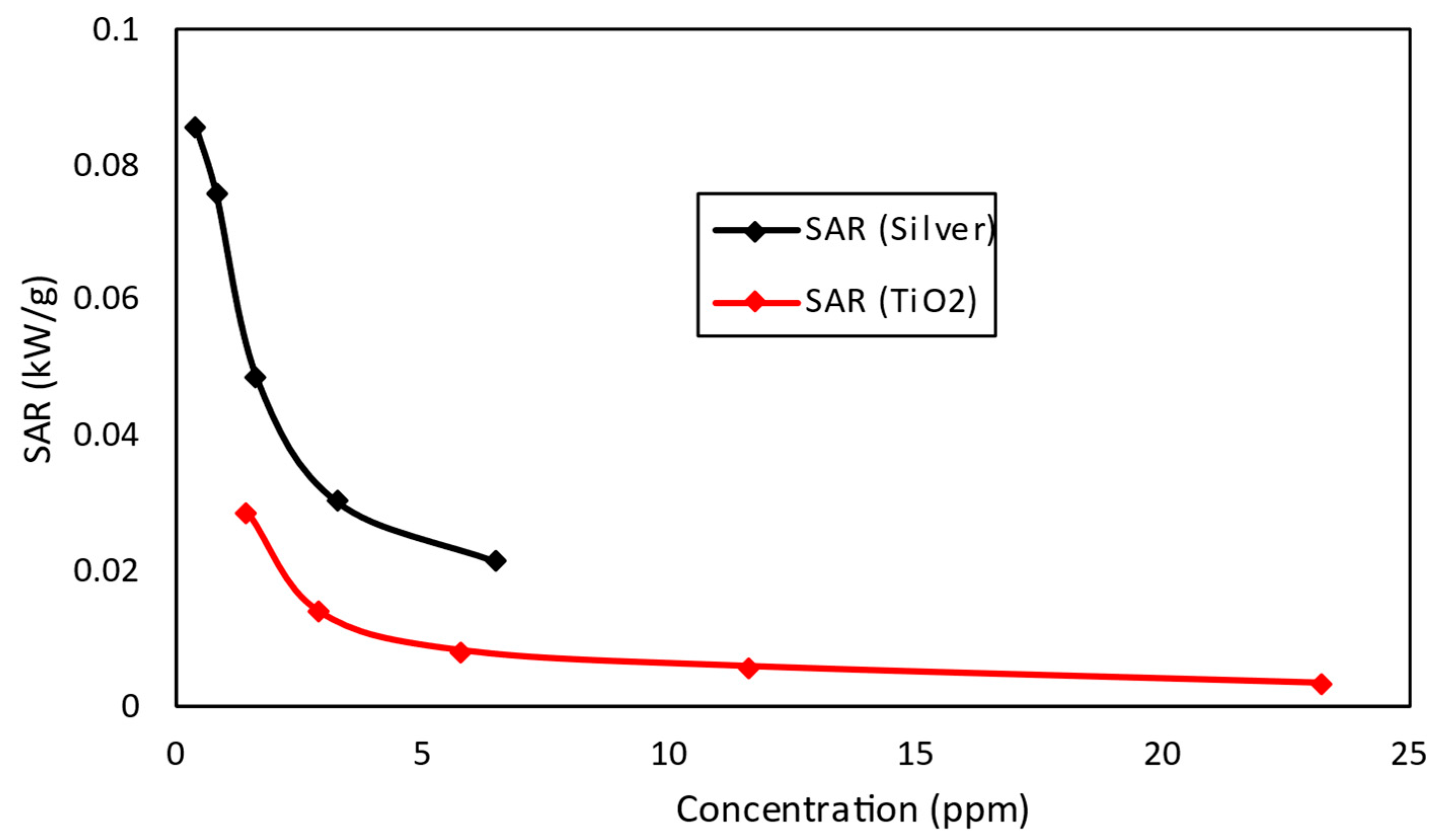

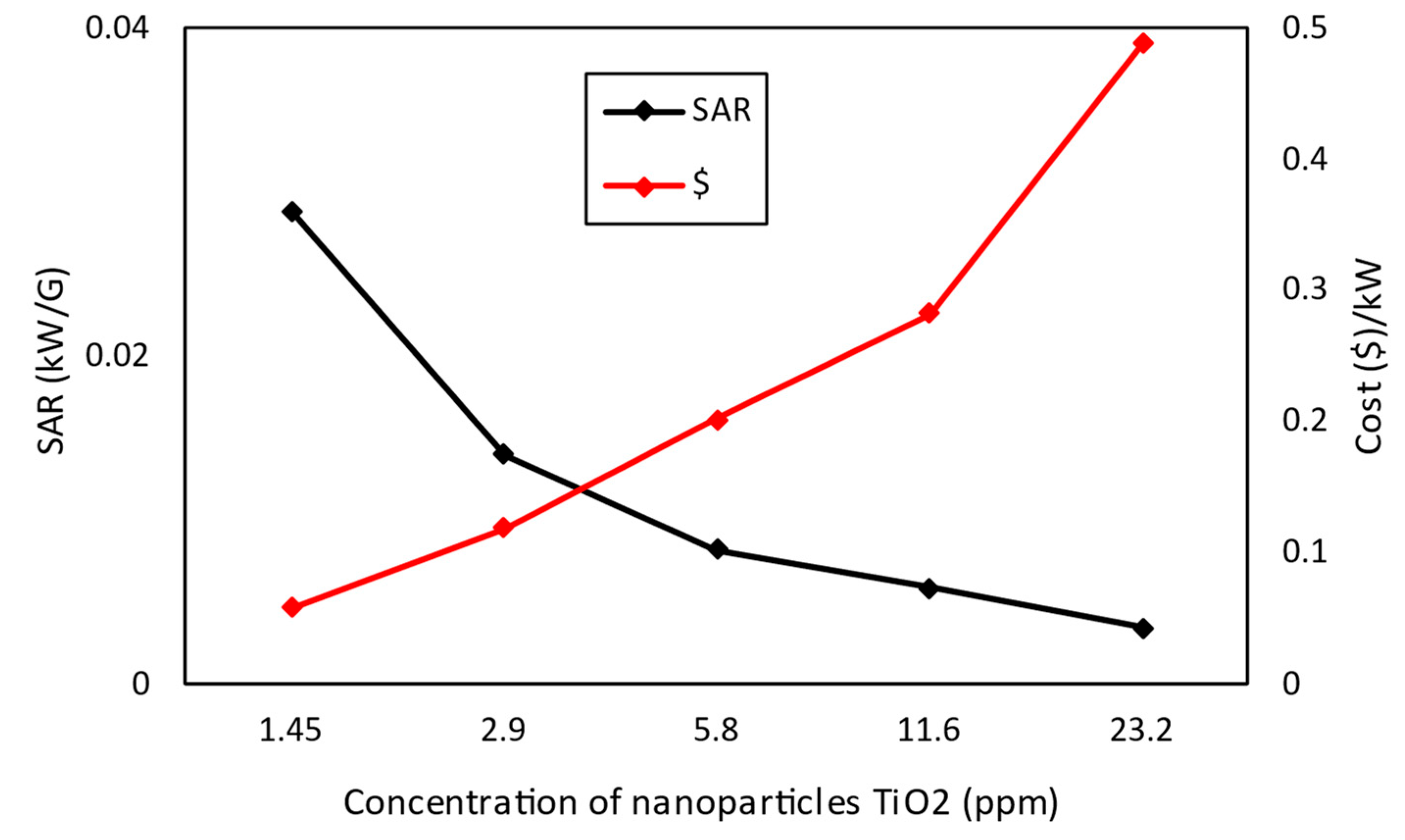

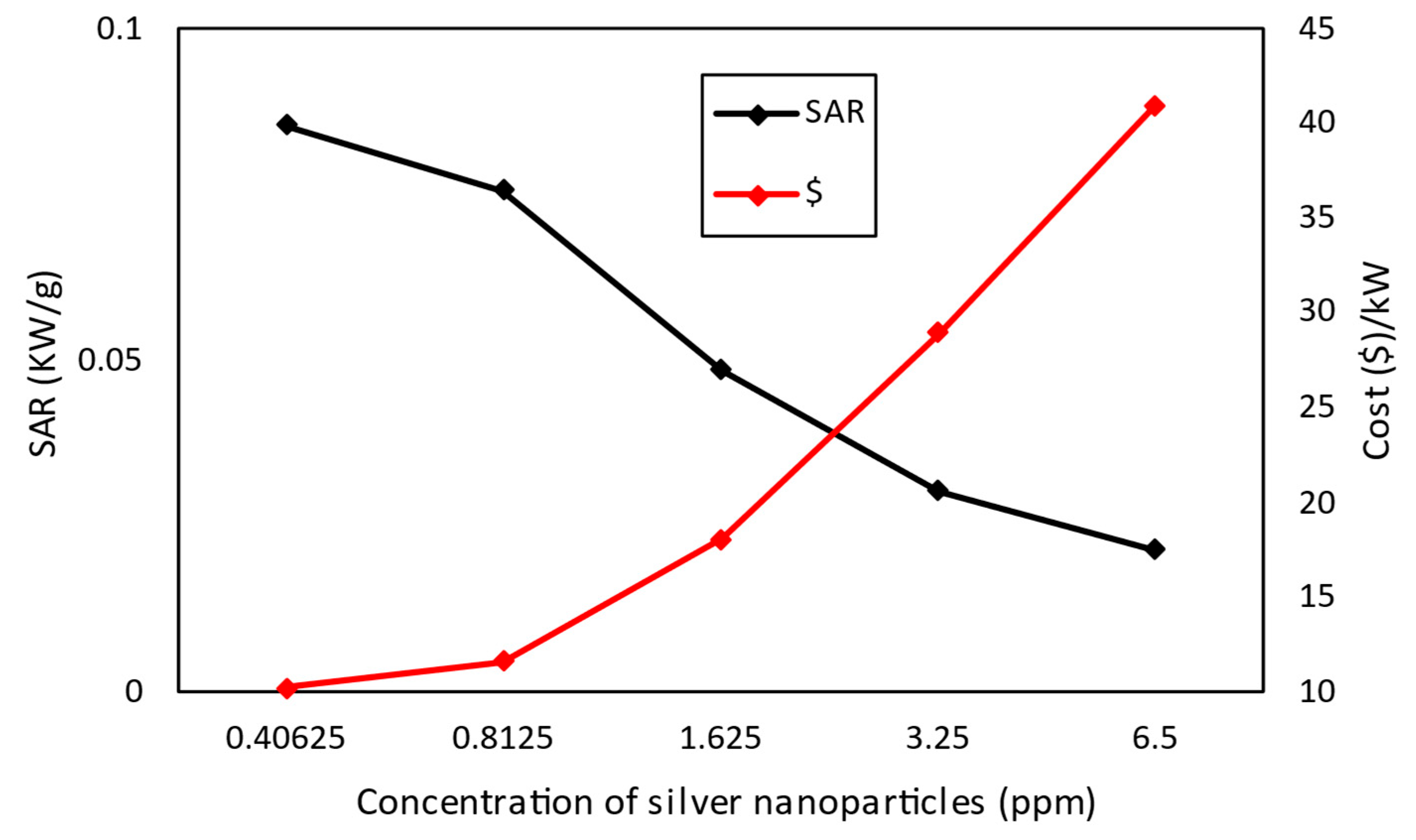

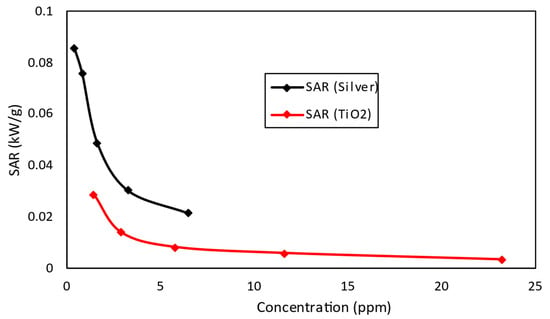

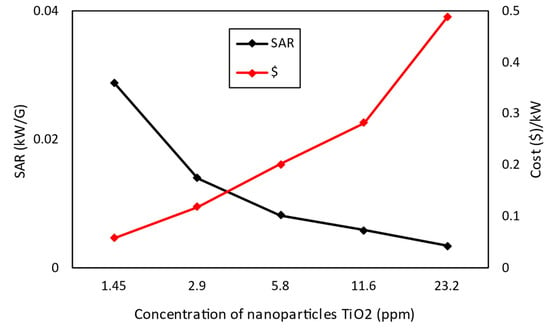

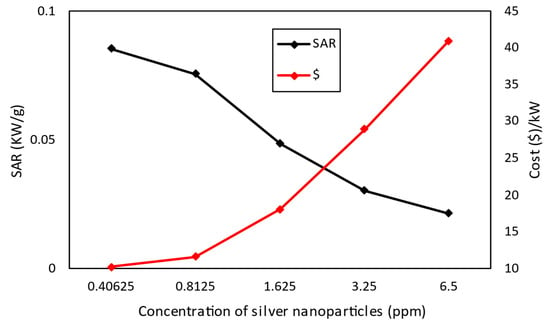

Figure 14 shows that silver nanofluids have a SAR consistently higher than that of titanium dioxide nanofluids at corresponding concentrations, and thus have a greater absorption capacity per unit mass. Nevertheless, in Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16, it can be seen the economic viability for the production of nanofluids with these nanoparticles, where the cost of silver nanofluid to produce 1 kW of energy at a concentration of 0.40625 ppm is close to US $10, while the cost of producing 1 kW of energy for TiO2 at the highest concentration of 23.2 ppm is close to US $0.49. This comparison highlights the higher cost of silver-based nanofluids, but when considering the type of application, the cost–benefit of nanofluids must also be weighed.

Figure 14.

Comparison between the SAR values of silver and titanium dioxide nanofluids.

Figure 15.

Economic viability of titanium dioxide nanofluid for the studied concentrations.

Figure 16.

Economic viability of silver nanofluid for the studied concentrations.

4. Conclusions

This study experimentally evaluated a dedicated setup for acquiring nanofluid performance data under direct solar irradiation. It demonstrated suitability for evaluating the direct absorption of solar radiation by nanofluids, focusing on the photothermal conversion capabilities of three nanofluids: silver, titanium dioxide, and a hybrid nanofluid combining the two. The following conclusions were made:

- The Solar Wall device was found suitable for direct energy absorption tests, with results showing high repeatability across three types of nanofluids at several concentrations.

- Regarding temperature gain, titanium dioxide nanofluids were less effective than silver nanofluids and hybrid compounds. Silver obtained a gain of 10.22 °C in the nanofluid concentration of 3.5 ppm, while the hybrid obtained a gain of 9.97 °C in the molar fraction of 25%, indicating that higher molar fractions may not be advantageous for the hybrid compound, since silver alone leads to a better result.

- At a maximum concentration (i.e., 23.2 ppm of TiO2), the nanofluid achieves an energy gain in relation to the base fluid of less than 10%, and the additional increase in concentrations did not imply any significant energy gain. This fact justifies not using higher concentrations, since 1.45 ppm already obtains similar results similar to those obtained with higher concentrations.

- For the concentrations studied, silver nanofluids have shown significant improvements, achieving an energy increase of up to 45.75% at a concentration of 6.5 ppm compared with the base fluid.

- The comparison between the three types of nanofluids indicated a better performance of the hybrid nanofluid in the Solar Wall, which achieves an energy gain of 34.52% in the molar fraction of 25%, while the silver in the concentration of 3.5 ppm obtained an increase of 31.93% in the concentration of 3.5 ppm and the titanium dioxide gained 9.04%.

- Silver nanofluids have shown a direct absorption capacity per unit mass always greater than that of titanium dioxide.

- During the tests, no instability such as sedimentation was observed for the nanofluid.

- Regarding temperature gain, it appears that at some point silver overtakes the hybrid nanofluid, while titanium dioxide does not achieve comparable gains.

- It can also be seen that silver nanofluids increase energy gain faster than hybrid nanofluids, until the gains become practically the same.

- Considering the cost analysis, silver is less economically viable, as it requires approximately US $10 to produce an energy unit (kW), whereas titanium dioxide requires US $0.49.

Author Contributions

R.J.P.L.—data acquisition, data curation, writing; J.P.d.A.N.—data acquisition, data curation, writing; V.F.N.—writing, review and editing; A.V.B., review and supervision; C.F.d.A.—review and supervision; M.E.V.d.S.—resources and supervision; P.A.C.R.—writing, resources, editing, review and supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001 and accomplished with the support of the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico—Brasil (CNPq)—Grant No. 303585/2022-6 and 405896/2016-6, both Brazilian governmental agencies.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be provided if requested.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Suman, S.; Khan, M.K.; Pathak, M. Performance enhancement of solar collectors—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 49, 192–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazdidi-Tehrani, F.; Khabazipur, A.; Vasefi, S.I. Flow and heat transfer analysis of TiO2/water nanofluid in a ribbed flat-plate solar collector. Renew. Energy 2018, 122, 406–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandarra Filho, E.P.; Mendoza, O.S.H.; Beicker, C.L.L.; Menezes, A.; Wen, D. Experimental investigation of a silver nanoparticle-based direct absorption solar thermal system. Energy Convers. Manag. 2014, 84, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalsamy, V.; Rajasekaran, K.; Baccoli, R. Experimental and analytical evaluation of nanofluid based parabolic trough solar collector under varying concentrations, flow rates, and ambient temperatures. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 75, 107219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmnifi, M.; Aleksandrovna, D.T.; Fadiel, A.F.A.; Shehata, A.I.; Moharram, N.A.; Taha, A.A. Unlocking hybrid solar efficiency: Experimental integration of aluminum foam fins and nanofluids in PVT collectors. Results Eng. 2026, 29, 108751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi-Moghadam, A.; Mohseni-Gharyehsafa, B.; Farzaneh-Gord, M. Using artificial neural network and quadratic algorithm for minimizing entropy generation of Al2O3-EG/W nanofluid flow inside parabolic trough solar collector. Renew. Energy 2018, 129, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, A.; Zareh, M.; Afrand, M.; Khayat, M. Effects of temperature and volume concentration on thermal conductivity of TiO2-MWCNTs (70-30)/EG-water hybrid nano-fluid. Powder Technol. 2020, 362, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim Neto, J.P.d.; Lima Pontes, R.J.; Rocha, P.A.C.; Marinho, F.P.; Silva, M.E.V. análise experimental de um sistema solar térmico utilizando nanofluido híbrido de prata e dióxido de titânio. Tchê Quím. 2020, 17, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainz-Manas, M.; Vossier, A.; Garcia, R.; Caliot, C.; Bataille, F.; Flamant, G. On-sun performance and stability of graphene nanofluids in concentrating direct absorption solar collectors. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2025, 83, 104605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathish, T.; Santhosh, A.J. Colloidal Er2O3 nanofluids for enhanced thermal and exergy performance of flat plate solar collectors: Interfacial insights and energy sustainability implications. Int. J. Thermofluids 2025, 30, 101478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beicker, C.L.L.; Amjad, M.; Filho, E.P.B.; Wen, D. Experimental study of photothermal conversion using gold/water and MWCNT/water nanofluids. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2018, 188, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozsoy, A.; Corumlu, V. Thermal performance of a thermosyphon heat pipe evacuated tube solar collector using silver-water nanofluid for commercial applications. Renew. Energy 2018, 122, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, H.; Arslan, K.; Eltugral, N. Experimental investigation of thermal performance of an evacuated U-Tube solar collector with ZnO/Etylene glycol-pure water nanofluids. Renew. Energy 2018, 122, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Mei, T.; Wang, G.; Guo, A.; Dai, G.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Wang, X. Investigation on enhancing effects of Au nanoparticles on solar steam generation in graphene oxide nanofluids. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 114, 961–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakmak, N.K.; Said, Z.; Sundar, L.S.; Ali, Z.M.; Tiwari, A.K. Preparation, characterization, stability, and thermal conductivity of rGO-Fe3O4-TiO2 hybrid nanofluid: An experimental study. Powder Technol. 2020, 372, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, M. Experimental investigation of first and second laws in a direct absorption solar collector using hybrid Fe3O4/SiO2 nanofluid. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2018, 136, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfe, M.H.; Esfandeh, S.; Amiri, M.K.; Afrand, M. A novel applicable experimental study on the thermal behavior of SWCNTs(60%)-MgO(40%)/EG hybrid nanofluid by focusing on the thermal conductivity. Powder Technol. 2019, 342, 998–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, S.; Venkitaraj, K.P.; Selvakumar, P.; Chandrasekar, M. Synthesis of Al2O3–Cu/water hybrid nanofluids using two step method and its thermo physical properties. Colloid Surf. A-Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2011, 388, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonomo, B.; Manca, O.; Marinelli, L.; Nardini, S. Effect of temperature and sonication time on nanofluid thermal conductivity measurements by nano-flash method. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2015, 91, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedkar, R.S.; Shrivastava, N.; Sonawane, S.S.; Wasewar, K.L. Experimental investigation and theoretical determination of thermal conductivity and viscosity of TiO2-ethylene glycol nanofluid. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2016, 73, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfellag, M.A.; Kazi, S.N.; Hasnain, S.U.; Nawaz, R.; Shaikh, K. Experimental evaluation of flat-plate solar collector performance with eco-friendly MWCNTs/hBN hybrid nanofluids: Energy, exergy, hydrothermal, economic, and environmental analysis. Energy 2025, 339, 139070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharaf, O.Z.; Al-Khateeb, A.N.; Kyritsis, D.C.; Abu-Nada, E. Energy and exergy analysis and optimization of low-flux direct absorption solar collectors (DASCs): Balancing power- and temperature-gain. Renew. Energy 2019, 133, 861–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; He, Y.; Liu, X.; Shi, L.; Zhu, J. Investigation of photothermal heating enabled by plasmonic nanofluids for direct solar steam generation. Sol. Energy 2017, 157, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalsi, S.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, A.; Alam, T.; Dobrota, T. Thermophysical properties of nanofluids and their potential applications in heat transfer enhancement: A review. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16, 105272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattad, A.; Awad, M.M. Thermophysical Properties of Nanofluid. In Nanofluid Heat Transfer; Awasthi, M.K., Gupta, R., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifin, Z.; Prasetyo, S.D.; Tjahjana, D.P.; Rachmanto, R.A.; Prabowo, A.R.; Alfaiz, N.F. The application of TiO2 nanofluids in photovoltaic thermal collector systems. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 1371–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, P.A.C.; Santos, R.F.M.; Lima, R.J.P.; Silva, M.E.V. A Review on Nanofluids: Preparation Methods and Applications. Tchê Quím 2019, 16, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wang, S.; Ma, J.; Tian, F.; Ren, Y. Experimental Study on the Light-Heat Conversion Characteristics of Nanofluids. Nanosc. Nanotechnol. Lett. 2011, 3, 494–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjad, M.; Zeiny, A.; Raza, G.; Bai, L. Photothermal Conversion Characteristics of Direction Solar Absorption Nanofluids. In Crossroads of Particle Science and Technology—Joint Conference of 5th UK-China and 13th UK Particle Technology Forum; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Hu, Y. Toward TiO2 Nanofluids—Part 1: Preparation and Properties. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeiny, A.; Jin, H.; Bai, L.; Lin, G.; Wen, D. A comparative study of direct absorption nanofluids for solar thermal applications. Sol. Energy 2018, 161, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.