Abstract

This paper presents an efficient optimization framework for high-frequency control of active downhole Flow Control Valves (FCVs) under geological uncertainty. Traditional proactive optimization methods for FCVs, while capable of maximizing life-of-field objectives such as Net Present Value (NPV), are computationally prohibitive when frequent updates are required. Conversely, reactive approaches are efficient but often neglect long-term recovery objectives. To address these challenges, we integrate two complementary strategies within a reservoir simulator: a reactive nonlinear programming method to maximize instantaneous cash flow, and a proactive streamline-based Time-of-Flight (TOF) equalization approach to improve sweep efficiency by balancing flood front arrival times. The framework is demonstrated on synthetic and realistic reservoir models, including the Olympus and Almakman references. Results show that, compared to conventional annual control strategies, the proposed approach increases NPV by 15–25% while reducing water handling costs and deferring breakthrough by up to four years. Furthermore, hybrid optimization effectively neutralizes fracture uncertainty, improving both mean recovery and the certainty of outcomes. Three field-scale case studies highlight the practical benefits of FCVs in improving lift performance, maximizing recovery from bypassed hydrocarbons, and reducing the number of wells required to meet production targets. By combining reactive and proactive control within a computationally tractable workflow, this study advances the practical deployment of intelligent completions for closed-loop reservoir management.

1. Introduction

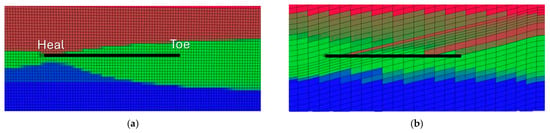

Lower completion flow control devices (FCDs) extend well control from the surface to the reservoir sandface. FCDs enable customized control of individual well zones to cancel out the negative impacts of reservoir heterogeneity, crossflow, and wellbore friction effects (Figure 1). Over the years, FCDs have grown in families and types to address different reservoir production challenges [1,2]. They can generally be classified into three families: passive, autonomous, and active devices. In this paper, we will focus on active devices, particularly flow control valves (FCVs) that are configurable after installation. Recent technologies have enabled remote sensing and control of FCVs, opening a new era of fast loop reservoir management.

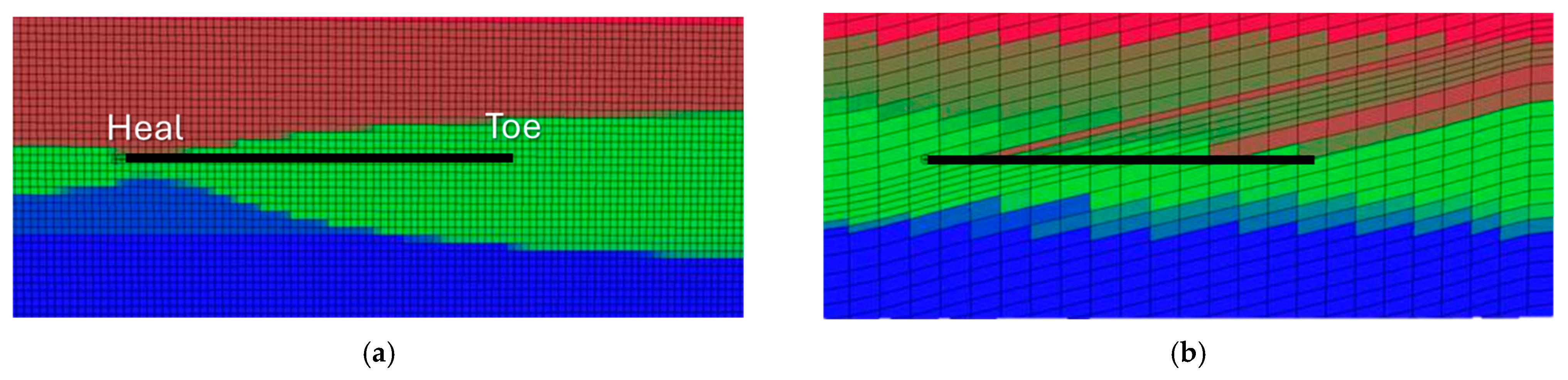

Figure 1.

Numerical simulation results illustrating key production challenges in highly deviated and horizontal wells. Fluid phases are color-coded: red for gas, green for oil, and blue for water. (a) In a homogeneous reservoir, the heel-to-toe effect emerges due to wellbore friction losses becoming significant relative to production drawdown. (b) In heterogeneous reservoirs, spatial variations in reservoir quality cause uneven well inflow, potentially accelerating water and/or gas breakthrough. The black line marks the trajectory of the producing well.

1.1. From Digital-Field Telemetry to High-Frequency Flow Control

Technological advances in downhole sensing, telemetry, and actuation have progressively shortened the classical “develop–implement–monitor–evaluate” reservoir-management cycle first formalized by Satter and Thakur [3]. Modern digital-oil-field infrastructures stream surface and down-hole measurements—volumetric flow rate, pressure, temperature, water cut, and gas–oil ratio—in real time, while intelligent completions equipped with remotely actuated flow control valves (FCVs) allow engineers to respond almost instantaneously. Numerous field trials have demonstrated that such intelligent completions lower unit development cost, reduce non-productive time, and improve ultimate recovery [4,5,6,7]. Numerical simulation and optimization of these devices need to evolve to provide reservoir and completion engineers with possible solutions during planning and operations.

1.2. Optimization Paradigms and Their Computational Burden

Existing optimization studies fall into two broad paradigms:

- Reactive (short-term) optimization uses instantaneous zonal rates or pressures to maximize immediate objectives such as incremental oil or water-cut reduction. Sequential linear programming, rule-based feedback, and critical water-cut heuristics have proven effective and computationally light, but they do not explicitly safeguard long-term recovery [8,9,10].

- Proactive (long-term) optimization formulates a life-of-field objective (typically net present value, NPV) and adjusts FCV settings on a prescribed schedule. Gradient-based and stochastic algorithms can find high-quality solutions [11,12,13], but their computational cost grows rapidly with update frequency, reservoir size, and uncertainty. For a 20-year horizon, monthly updates in a 20-FCV field involve ~4800 optimization variables, rendering brute-force simulation under ensembles impractical.

Streamline-based techniques alleviate some of this cost. Time-of-flight (TOF) analysis reallocates injector/producer rates to equalize flood arrival times and has been extended to well-level FCV control [14,15]. Yet applications to compartment-level valves and field-scale uncertainty remain limited.

1.3. Challenges and Research Gap

Among the principal challenges facing high-frequency optimization of FCVs, there are two of particular concern: (1) optimization turnaround compatible with high-frequency actuation cycles and (2) integration of short- and long-term control objectives within a single workflow. Existing proactive methods struggle with (1), while most reactive schemes neglect (2). Simple reactive methods, such as those suggested by Dilip and Jackson [9], may not be suitable to capture changing dynamics in reservoir or economic conditions.

Conversely, the proactive flow control device problem is usually posed as a global optimization problem, which requires hundreds of simulations to reach an optimum [13]. If the number of control steps is , and the number of optimization variables is , the total number of optimization variables is () in global optimization. Each iteration of global optimization is a full simulation run. Take, for example, the problem of optimizing 20 flow control devices over a period of 20 years. If the prediction period was divided into 10 bins, 2 years each, the total number of optimization variables is . While 2 years is quite a long time in reservoir management, the problem is also intractable for realistic full-field simulation models.

1.4. Contribution of This Study

This paper proposes an efficient dual-mode optimization framework—a reactive nonlinear-programming method and a streamline-based TOF equalization method—that addresses the above challenges and supports high-frequency control of active FCVs under geological uncertainty. Key features are:

- Reactive optimization maximizes instantaneous cash flow subject to drawdown and valve-setting constraints.

- Proactive, streamline-based optimization balances flood-front arrival times to delay water/gas breakthrough

- Single-case evaluation per realization

The problem is redefined such that one or two main objectives can be achieved: (1) zonal flow equalization and (2) appropriate reactive measures to reduce unwanted phases production.

The objectives can be mixed in a hybrid setup. These methods are integrated into the well solution routines of a reservoir simulator, where device settings are optimized during time-stepping. We use a next-generation reservoir simulator designed to handle complex physics efficiently [16]. The reservoir is discretized at the required resolution to represent the main geologic features and capture reservoir heterogeneities. Multiple equiprobable reservoir realizations can be generated, given the main reservoir uncertainties, to quantify the possible development risks. To represent the smart wells, the simulator employs the multi-segmented well model [17], accounting for hydrostatic, acceleration, and friction losses. Given the valve constriction flow area and a flow coefficient, the special segments model the pressure drop for each FCV.

The workflow is demonstrated on several synthetic and realistic simulation models, such as the OLYMPUS water-flood reference model. Compared with annual proactive control, the proposed approach boosts NPV by 25% through reduced water handling, while TOF-based scheduling defers breakthrough by 2–4 years. In another test case, Almakman, a reference for fractured carbonate reservoirs with 100 realizations, is tested. We demonstrate an FCV value preposition and quantification workflow through incremental recovery and uncertainty reduction. We also report several reservoir management use cases using real reservoir models to evaluate the benefits of installing flow control devices. By combining reactive and streamline-driven methods within a unified, computationally tractable framework, this work advances the practical deployment of intelligent FCVs for near-continuous closed-loop optimization.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 outlines the main types of subsurface flow control devices, highlighting how actively adjustable flow control valves enable real-time reservoir management. In Section 3, we compare global and local FCV optimization methods and their advantages and disadvantages. In Section 4, we define the optimization objectives, constraints, and formulation for both the reactive and proactive methods. Section 5 focuses on the comparison between reactive and proactive optimizations using the OLYMPUS reference simulation models. Section 6 presents hybrid optimization results in a fractured carbonate synthetic model. In Section 7, we present three case studies demonstrating FCVs in achieving efficiency gains in reservoir management. Section 8 presents the lessons learned after 7 years of evaluating FCV value in synthetic and realistic reservoir simulation models. Section 9 offers concluding remarks.

2. Flow Control Valves

Subsurface flow control devices can be broadly classified into three categories: passive, autonomous, and active devices. Passive and autonomous devices, such as Inflow Control Devices (ICDs) and Autonomous Inflow Control Devices (AICDs), are designed prior to well installation to optimize production performance. Their design can be tailored to reservoir-specific rock and fluid properties by selecting the appropriate number, size, and type of nozzles and devices. However, the settings of these devices are fixed upon installation and cannot be adjusted thereafter.

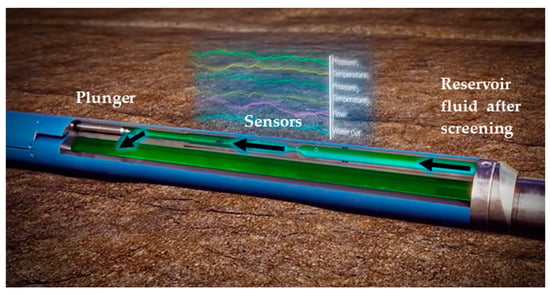

In contrast, Flow Control Valves (FCVs)—the focus of this article—enable active, possibly real-time control after installation. FCVs operate through various actuation mechanisms, including hydraulic, electric, or hybrid systems, depending on how their settings are adjusted. These valves can be either discrete, offering a set number of fixed positions, or continuous, allowing for any position between fully open and fully closed. Recent advancements have enabled FCVs to incorporate intelligent functionalities, enhancing their capability for reservoir management.

An example is the Manara™ production system (Figure 2), a fully electric FCV suitable for installation in various well architectures, including conventional vertical, horizontal, extended reach, and multi-lateral wells. The Manara system provides in-lateral and junction flow control and is equipped with sensors for measuring zonal flow rates, pressure, temperature, and water cut. Its control and telemetry signals are communicated to the surface via induction coupling [18].

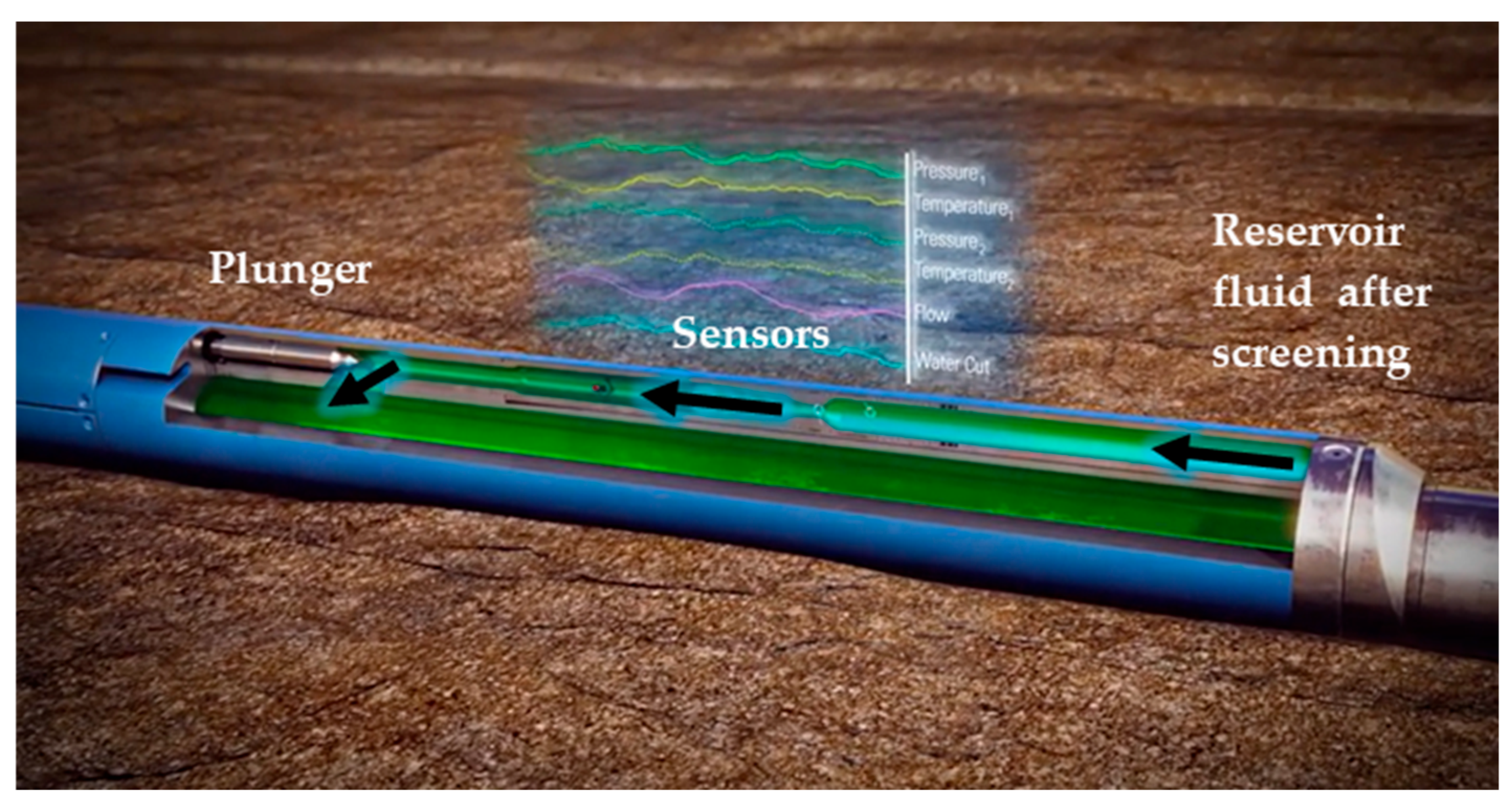

Figure 2.

An example of a FCV, with sensors for measuring temperature, pressure, flow rate, and water cut. The plunger on the left-hand side can be electrically actuated to be fully open, fully closed, and any position in between [19].

3. Global vs. Local FCV Optimization

Reservoir optimization studies [20,21] differentiate between two classes of optimization problems:

- (1)

- Local | Short-Term | Instantaneous Optimization Problems: These are mostly routine tasks carried out to achieve short-term optimization of well/asset production. Examples of these tasks include gas-lift optimization, well rate allocation, and smart well optimization problems.

- (2)

- Global | Long-Term | Big Loop Optimization Problems: These are mainly investment decisions concerning the field development plan, such as the number and type of wells to be drilled, the optimum capacity for surface treatment facilities, and the number of rigs available for drilling and workover operations.

Local optimization problems can be more efficiently handled at runtime. That is, the optimization can be applied as part of flexible controls in field management. Some local optimization tasks, such as gas-lift optimization, have been adopted as standard functionality in many reservoir simulators [22]. In addition, smart well optimization as part of the reservoir simulation run has been implemented in some studies [8]. Although a long-term optimum solution is not guaranteed, the advantage of local optimization is its efficiency. Often, short-term optimization parameters are dealt with within global optimization workflows [23].

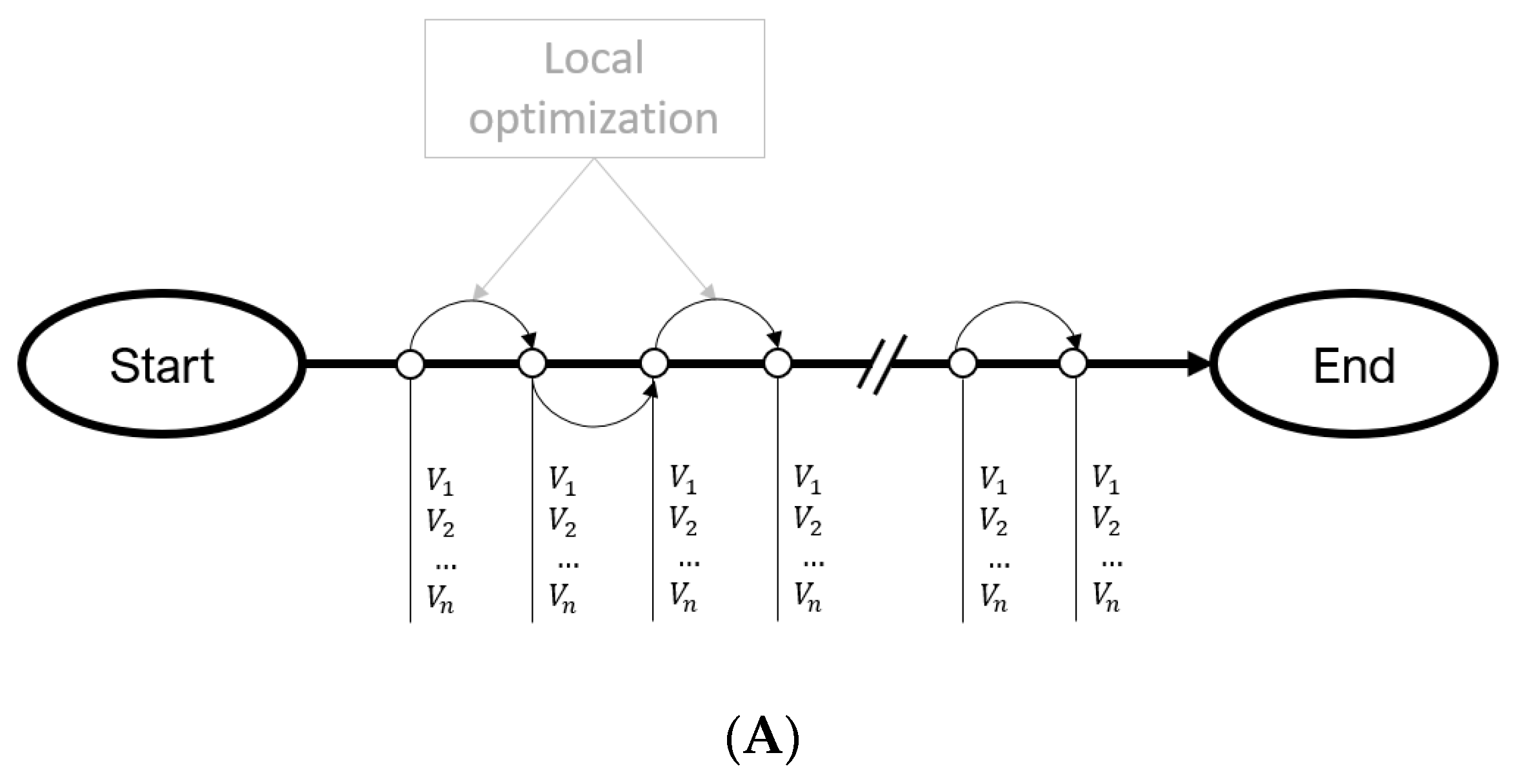

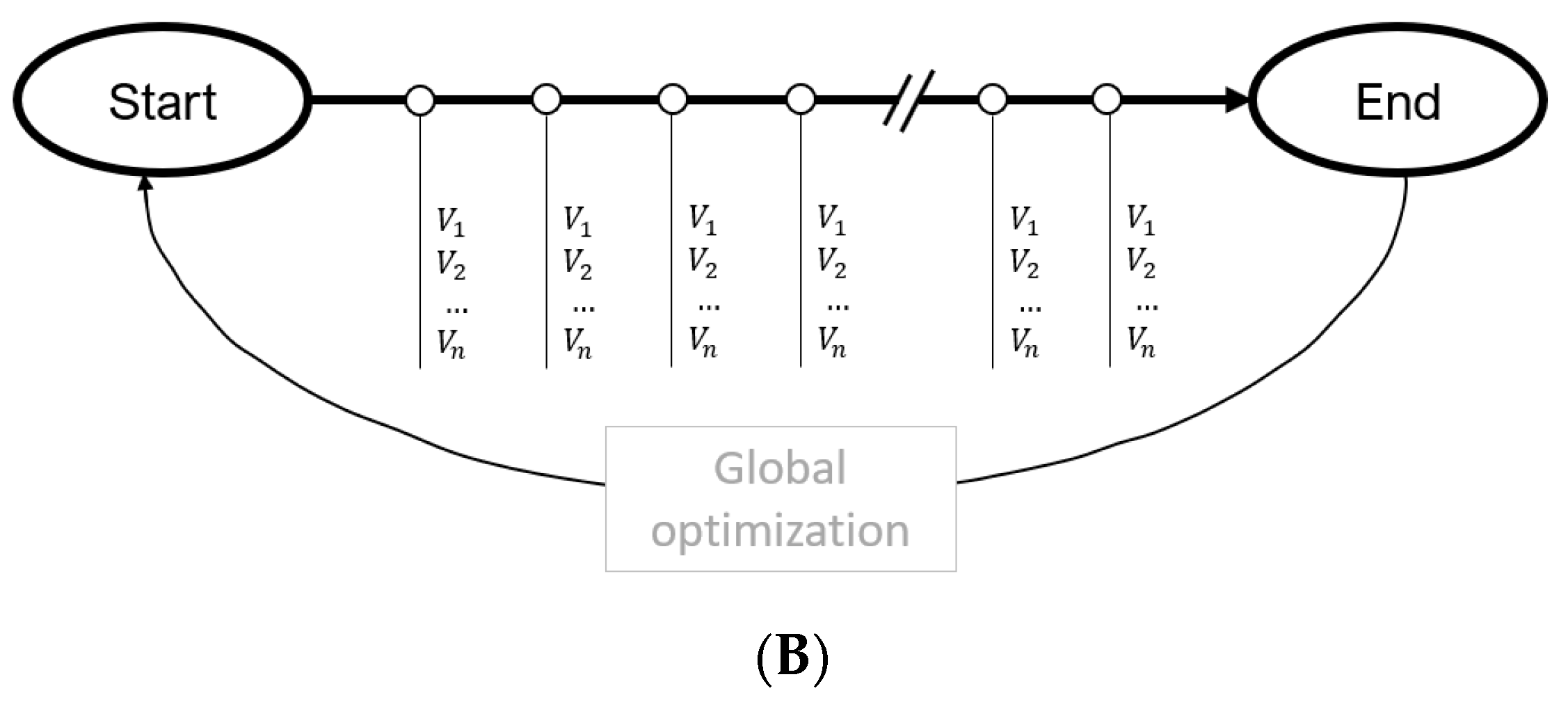

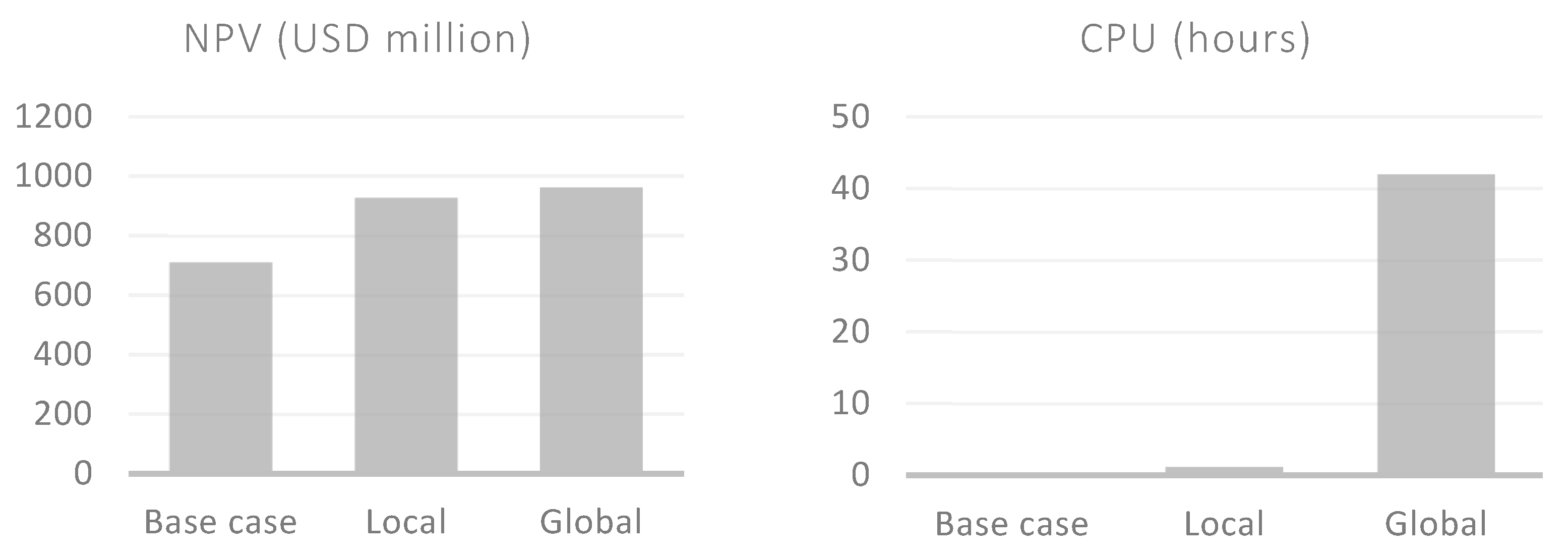

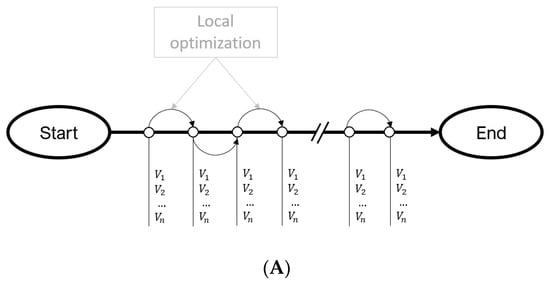

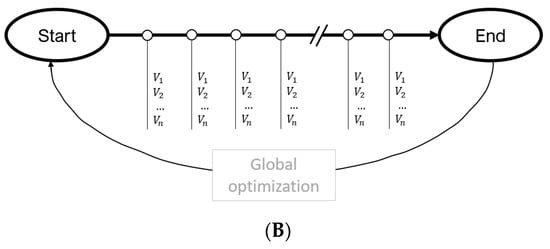

Figure 3 compares the number of optimization variables and optimization cycles between local and global optimization workflows. If the number of control steps is , and the number of optimization variables is , the total number of optimization variables is () in global optimization. Each iteration of global optimization is a full simulation run. In local optimization, the number of optimization variables considered is , and their cycle is during the simulation timestep. As a result, local optimization can be achieved within a single simulation run. Figure 4 is a comparison of cost and objective results between local and global optimization of 20 flow control devices over a period of 20 years. The prediction period is divided into 10 bins, 2 years each. The total number of optimization variables is . Hence, the global optimization workflow required hundreds of simulations to reach an optimum. Results show that the local optimization achieves 96% of the global optimization objective, but only at 3% of the computational cost.

Figure 3.

(A) A local optimization workflow applied for repetitive field operations. The small circles represent control steps, each containing optimization variables. (B) A global optimization workflow applied to repetitive field operations. The total number of variables is prohibitively large, especially for high-frequency FCV setting optimization.

Figure 4.

Results of applying local and global flow control device optimization on Olympus realization (1). There are 10 optimization intervals covering a prediction period of 20 years.

4. The Optimization Problem

In this section, we define the optimization problem and the objective functions. For further details of the optimization process, refer to [24,25]. The valve setting, , described as the fractional open area, is a dynamic property that can change with time to allow setting the valve to fully open, 1, fully closed, 0, and any value in between. An optimization problem can be formulated at the well or field levels to achieve a set of objectives, subject to linear and non-linear constraints. We represent the problem as follows:

Equation (1) represents the minimization of the objective function given control valve fractional openings, , for a number of FCVs. Equation (2) represents the set of linear constraints bounding the range of allowable fractional openings for each FCV between a minimum value, , and a maximum value, . Equation (3) represents the set of non-linear inequality constraints applied at the well and FCV levels (e.g., max flow rate). Table 1 lists these constraints.

Table 1.

Type and level of constraints applicable during optimization.

4.1. Proactive Strategies

4.1.1. Flow Balancing

In this proactive strategy, the zonal production contribution is equalized to avoid excessive production from high-permeability zones. The objective function, , is a mismatch between the target and actual zonal flow rates, and .

By default, all zones contribute equally. Otherwise, balance factors can be introduced to control the target zonal rates. Balancing zonal contributions can help cancel out the heel-to-toe effect and unequal production due to permeability variations. The target zonal rate can be weighted by the total permeability-perforation-thickness (kh) to allow the least flow resistive path, while the optimizer can set additional controls to prevent crossflow.

4.1.2. Streamline-Based Proactive Optimization

Fully integrated within the reservoir simulator, streamlines are generated at a prescribed frequency. The streamlines are bundled depending on the receiving FCV, then a time of flight (TOF) analysis is performed to predict the front breakthrough time at each FCV. TOF, , of a streamline, , is related to the reservoir displacement pore volume, , and flow rate, , at the location, , along the streamline through the following relationship:

The flow rate is a function of dynamic properties such as pressure, mobility, and permeability (Darcy’s law), naturally leading to a variable TOF profile for the different FCVs. The equation establishes an inverse relationship between TOF and the flow rate, as the pore volume can be considered constant. However, as FCVs can be used to control flow-rates, the streamline method can calculate a target flow rate by equalizing the front arrival TOF for each FCV such that:

The translation of the target flow rates to FCV settings is not a trivial task, given the non-linearity of the fluid flow problem in the well and the surrounding reservoir. Hence, an interior-point method (IPM) non-linear optimizer is utilized by treating the target flow rates calculated during the streamline analysis as constraints.

4.2. Reactive Strategies

4.2.1. Fiscal Optimization

The objective in this reactive method is to maximize the instantaneous returns at a specific timestep. The fiscal objective function then takes oil price, water, and gas handling cost per unit (, , ) as input parameters to balance oil production against water and gas production rates. The objective function to maximize can be written as:

where is a bias factor to ignore or emphasize the completion device for zone in the optimization, and the subscripts , , refer to oil, water, and gas phases. Recall that the optimization is instantaneous and cannot, therefore, capture a full NPV objective including discounting.

4.2.2. Rate Penalty

In this method, zones producing water, gas, or both are penalized based on water cut or gas–oil ratio. The penalty is based on a heuristic relationship such as that suggested by Addiego-Guevara et al. [26] and Vasper et al. [10]. The objective function to maximize is as follows:

where is a penalty term that combines gas and water sub-components based on the gas–oil ratio and water cut, respectively.

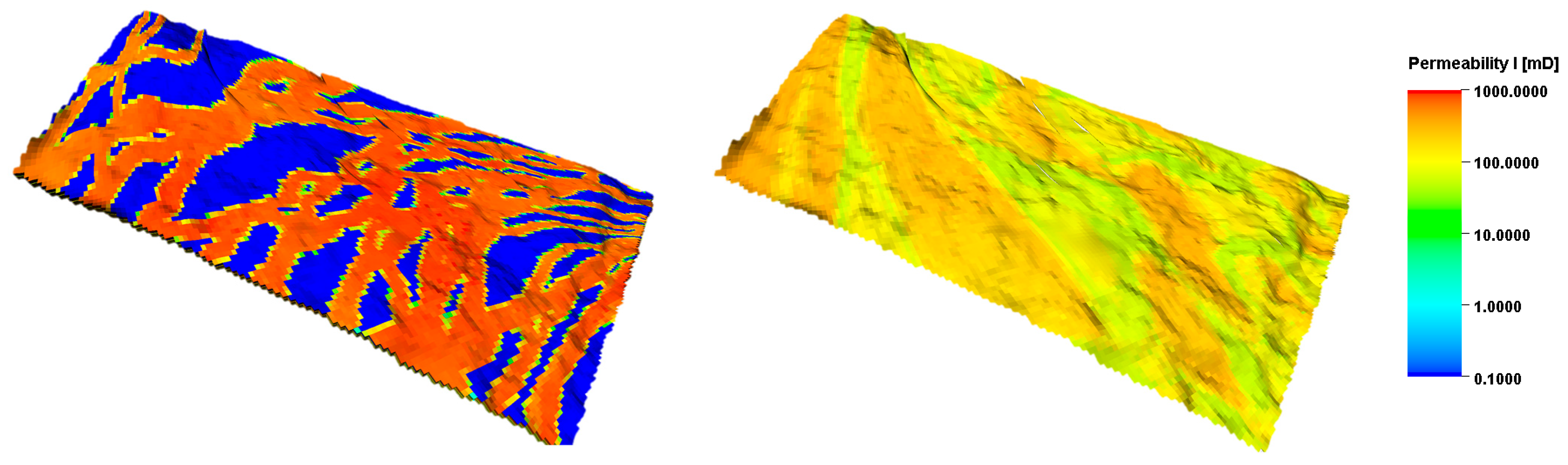

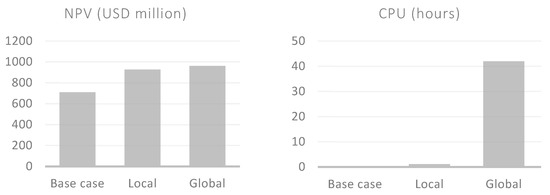

5. Reactive vs. Proactive Optimization

In this section, we review the results of running pure reactive and proactive methods compared to no downhole control cases. In OLYMPUS reference models, there are 50 simulation models (realizations) that represent uncertainty in a hypothetical green field [27]. The synthetic model is inspired by the BRENT group reservoirs in the North Sea. It comprises two reservoirs separated by an impermeable shale layer. The upper reservoir contains highly permeable channels in a background of tight flood-plain sands (Figure 5). The lower reservoir has coarse, medium, and fine-grained sands with less heterogeneity compared to the upper reservoir. The OLYMPUS model dimensions are 118 × 180 × 16 with the total number of cells of 339,840.

Figure 5.

The permeability distribution in the upper (left) and lower (right) reservoirs in one realization of the OLYMPUS model.

Our implementation of the proactive optimizer focuses on equalizing flood fronts using the FCV settings at the producers. The objective, thus, is to improve flooding efficiency by delaying breakthrough times. The reactive optimizer, on the other hand, uses an instantaneous objective function to maximize oil production and minimize water production. The optimization runs were subject to the following constraints:

| Minimum valve setting (fraction) | 0.0001 |

| Maximum valve setting (fraction) | 1.0 |

| Maximum setting change per month | 1.0 |

| Maximum water cut (fraction) | 0.80 (above which the valve is closed) |

| Minimum liquid rate (m3/day) | 1.0 (to avoid crossflow) |

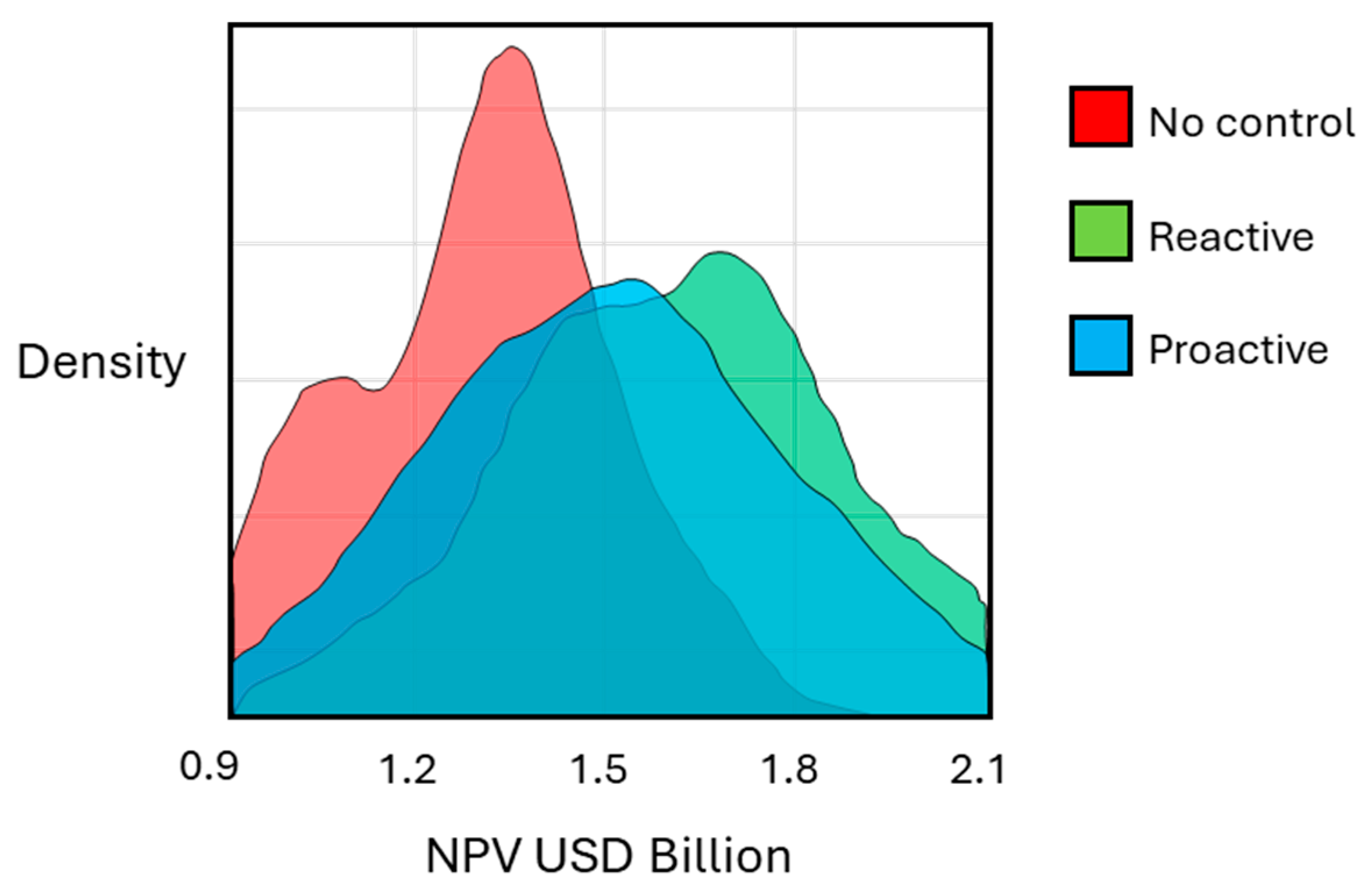

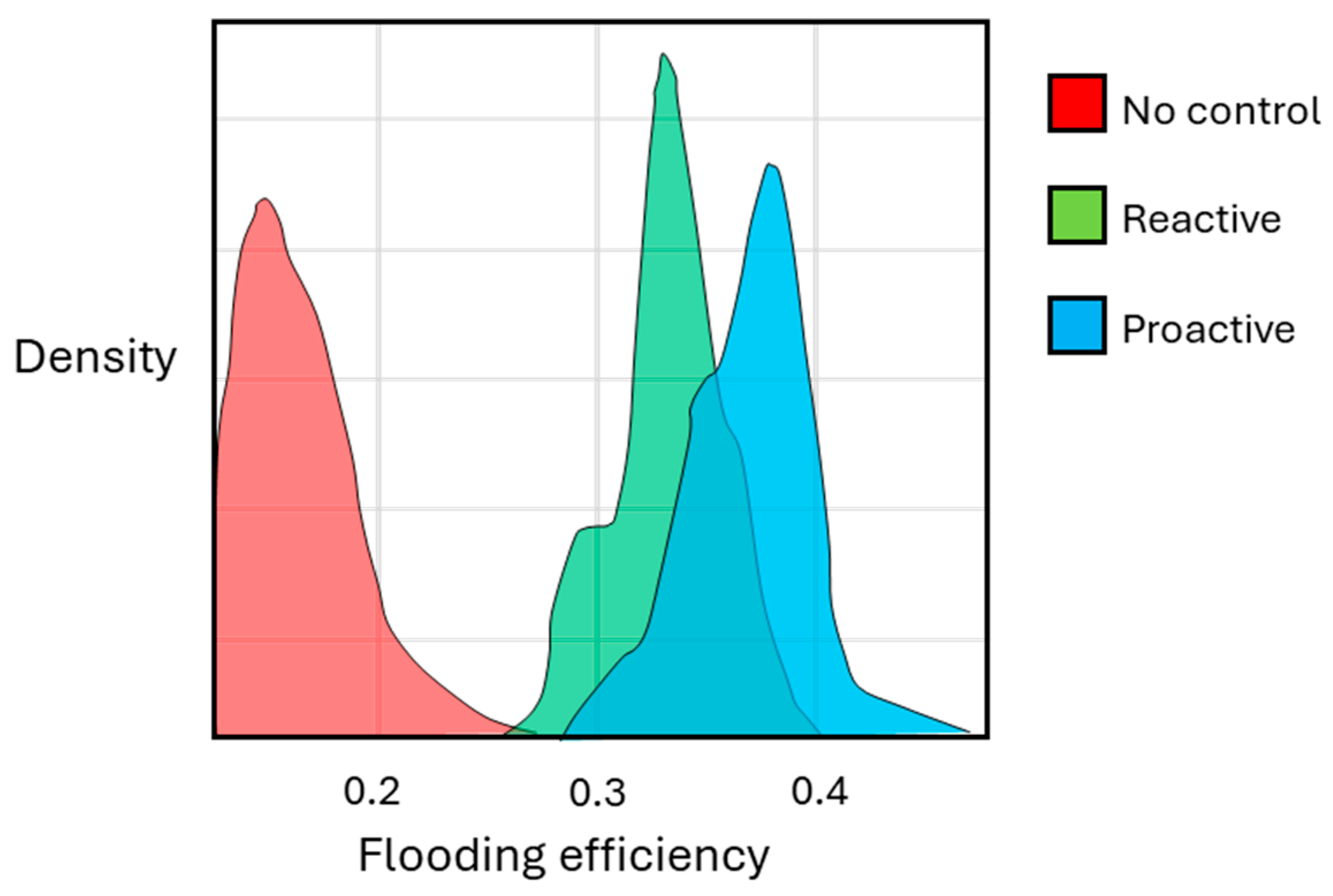

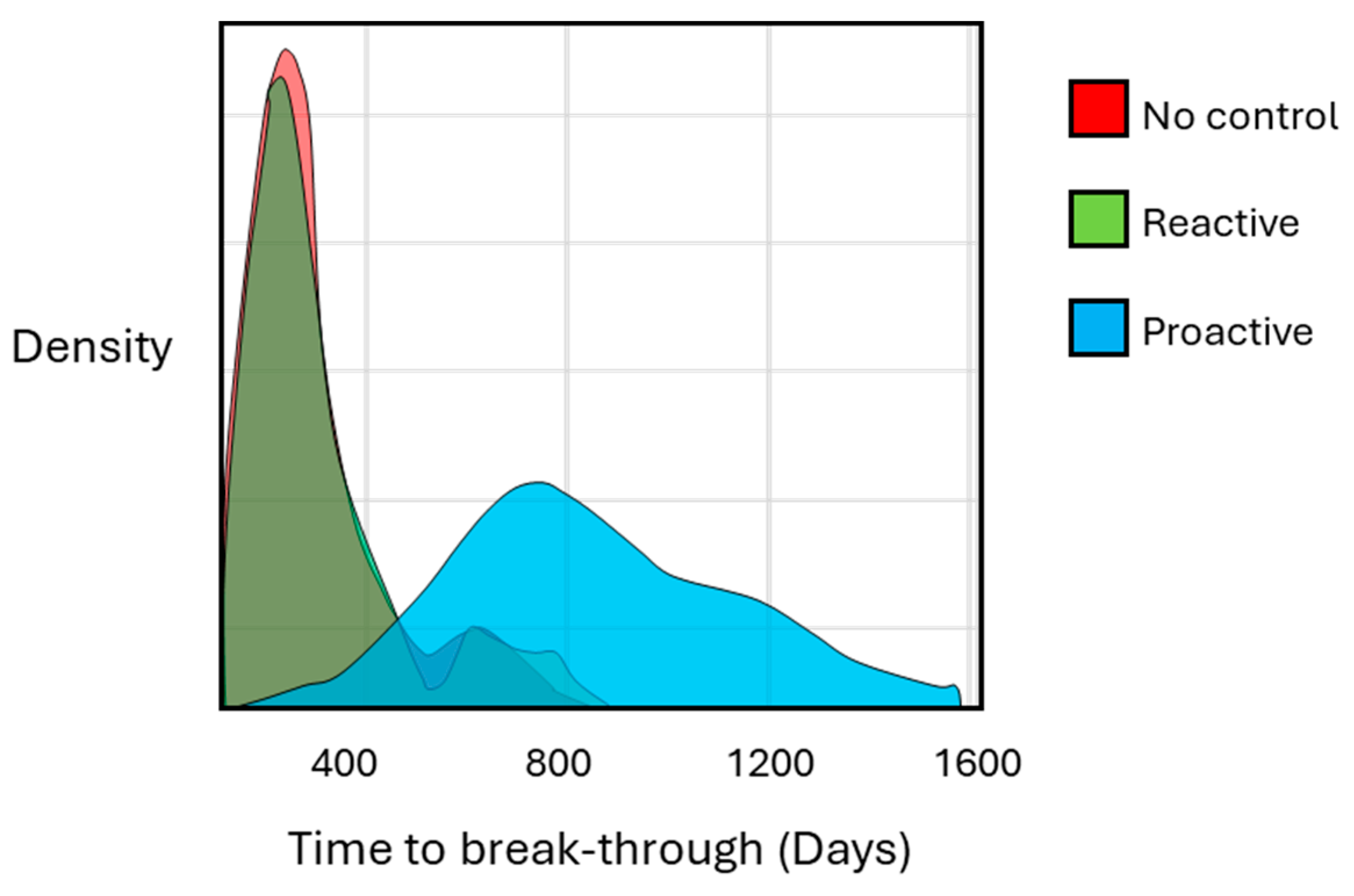

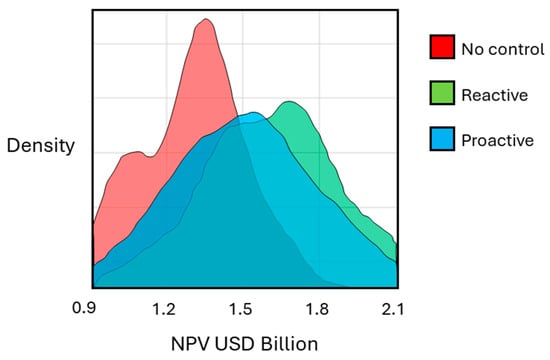

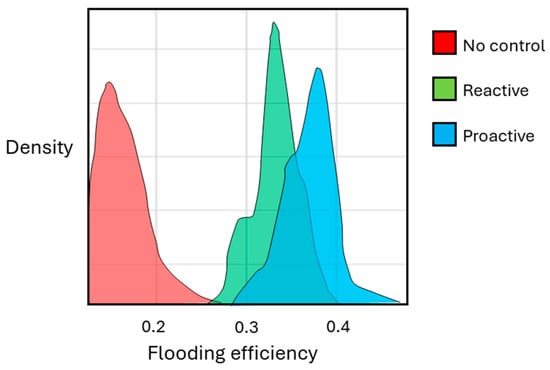

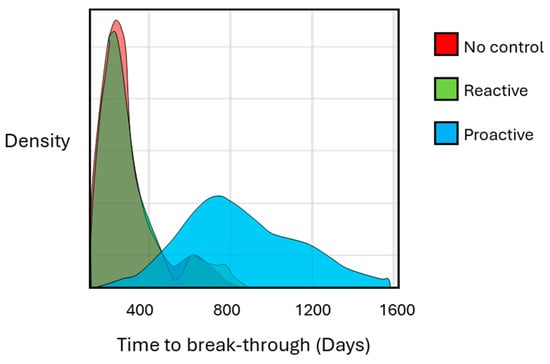

The optimization results showed similar overall oil recovery compared to the base cases (no control). For example, in realization 1, the cumulative oil production is 6.3 million sm3 in the base case and 6.7 million sm3 in the FCV optimized cases. However, due to reduced water production and injection, the average NPV increased from USD 1.31 × 109 for the base cases to USD 1.51 × 109 by proactive optimization, and USD 1.62 × 109 by reactive optimization (Figure 6). Hence, the NPV is expected to improve by 15–25% by optimizing the flow area of FCVs. Both optimization methods, proactive and reactive, improved injection efficiency, as shown in Figure 7. The high permeability channels in the upper reservoir pose a clear risk to water flooding, as water preferentially follows the channels to cause early water breakthrough. The proactive optimizer controls the arrival times, whereas the reactive optimizer minimizes water production after breakthrough to maximize the NPV. Hence, the proactive optimizer was most effective in delaying the breakthrough time (Figure 8).

Figure 6.

Histograms showing the NPV distributions for the base cases (no control) and reactive and proactive optimization.

Figure 7.

The efficiency results in the base cases (no control) and reactive and proactive optimization strategies. The flooding efficiency is calculated as [oil production/(water production + water injection)].

Figure 8.

Water breakthrough time analysis for base cases and reactive and proactive strategies.

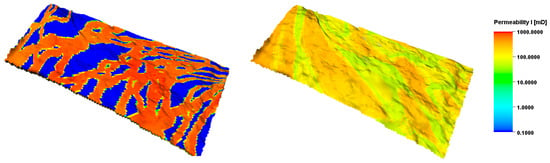

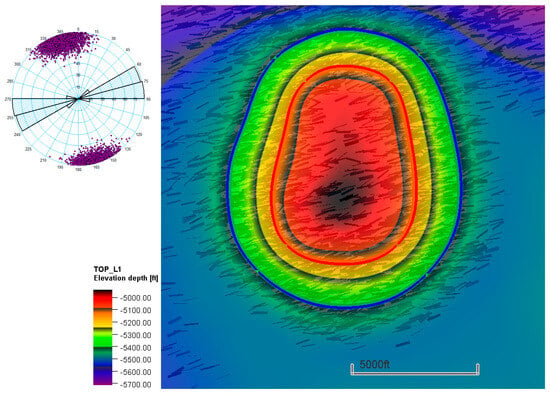

6. FCV Impact on Neutralizing Fracture Uncertainty

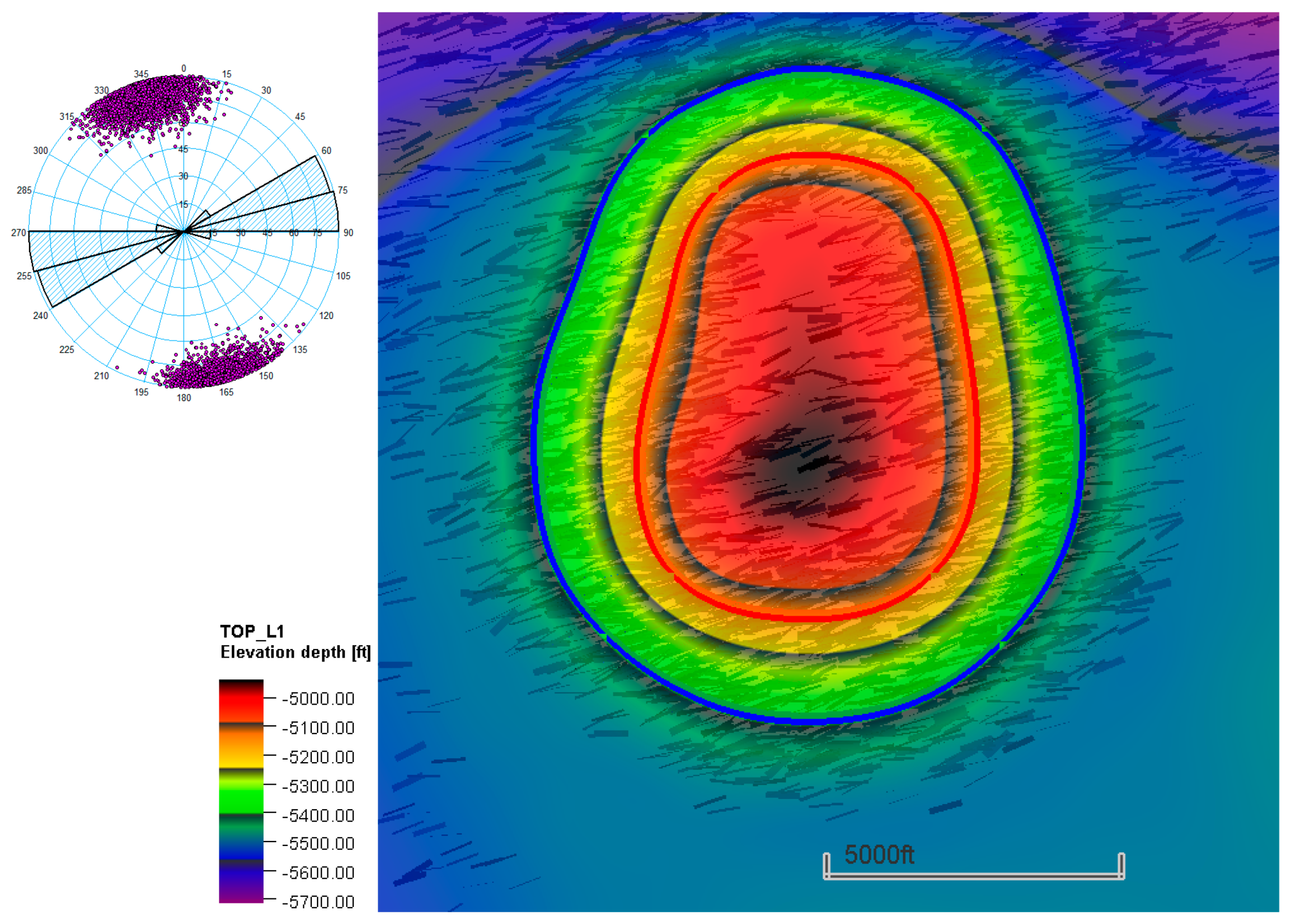

Almakman is a synthetic offshore carbonate model with 100 realizations [28]. The reservoir structure is a typical four-way dip closure, and it is composed of three geological formations. The petrophysical properties are inspired by the Lawyer Canyon window, a carbonate ramp deposit of San Andres Formation [29,30,31,32]. The formations are fractured, with an East–West-oriented set of through-going fractures. The intensity of the fracturing is related to the dip of the formation (Figure 9). The total number of cells is 400,000.

Figure 9.

Top surface of Almakman and initial fluid contacts (blue = water–oil contact, red = gas–oil contact). The map shows background fractures with an east–west orientation, as indicated in the Rose diagram (top-left). The intensity of the fractures is related to the structural dip.

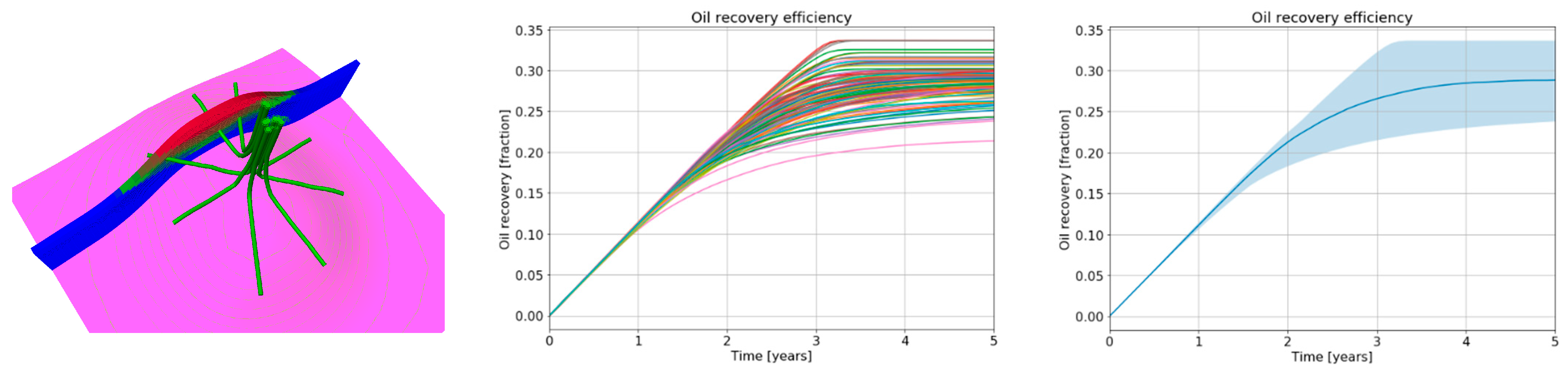

The main uncertainty lies with fracture properties: fracture intensity, fracture length, fracture orientation distribution, and aperture. These properties were varied according to common distributions using a Monte Carlo sampler to create 100 realizations of discrete fracture models. Using a single porosity approach, the fracture models were then upscaled to calculate effective permeability distributions for the 100 realizations. While horizontal wells can delay water breakthroughs, the presence of fractures impacts the potential hydrocarbon recovery. Figure 10 shows the field production profiles without FCV controls.

Figure 10.

Almakman base depletion strategy with 8 horizontal wells (left), the corresponding oil recovery results from the full ensemble (center), and oil recovery results from the full ensemble extracted showing P50 (solid line) with confidence interval [P01–P99] (right).

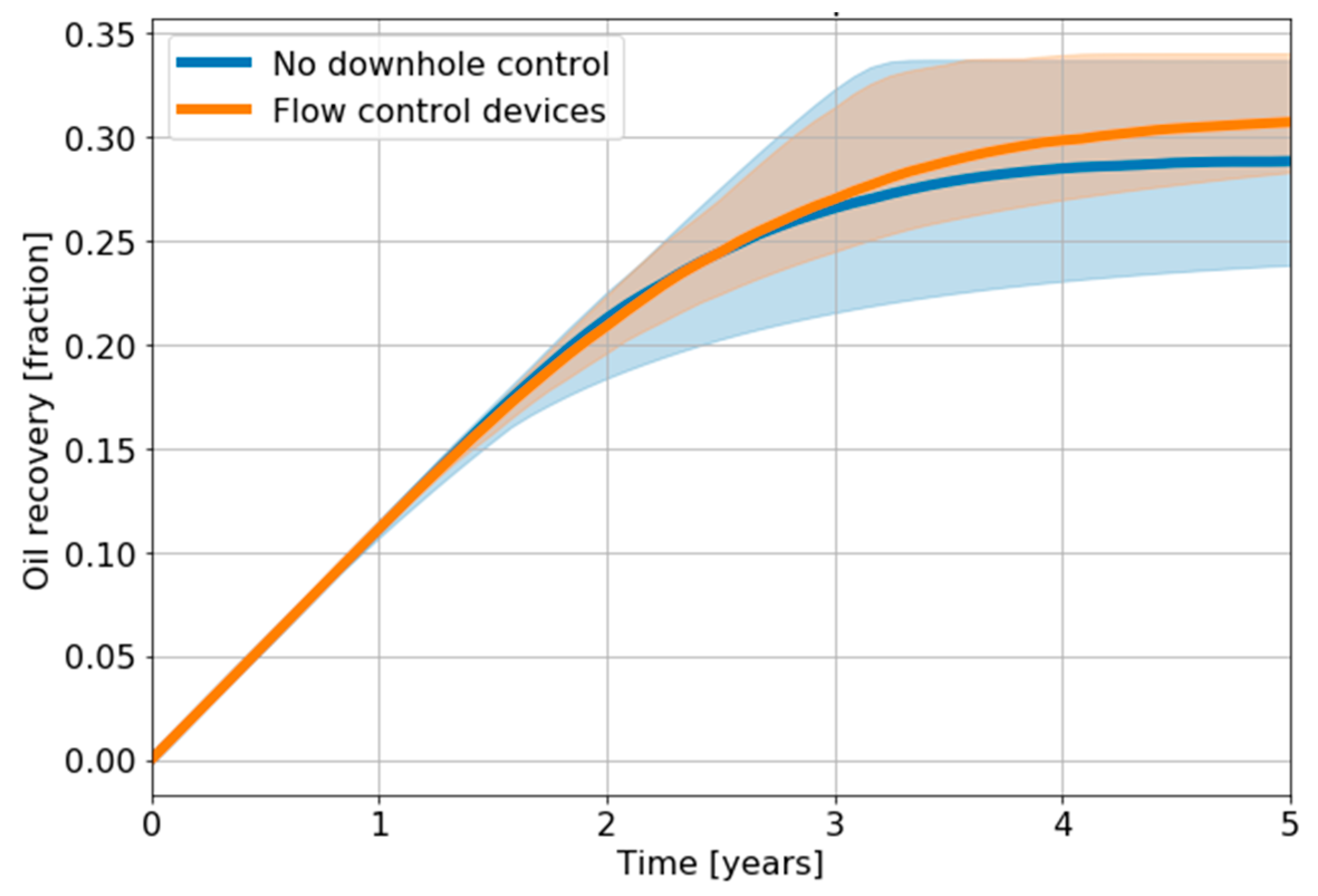

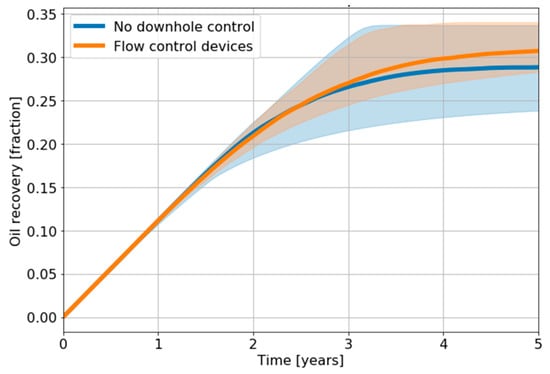

Flow control devices offer an increased resolution to control reservoir sweep efficiency. They can be used in reactive and/or proactive strategies to reduce production of unwanted phases and balance fluid fluxes from different well zones. Here, we implement a hybrid proactive and reactive strategy to operate flow control valves: All wells are completed with three zones, each allocated a flow control device. Initially, the objective is to obtain balanced production from the different well zones. When the GOR of one of the zones exceeds 10,000 SCF/STB, the objective switches to a reactive strategy to achieve gas and water production minimization. The control valve settings are updated every 6 months, making a total of 240 variables (8 × 3 × 10) per realization. The results show the potential benefits of downhole control in a fractured reservoir (Figure 11), an improved recovery, and a reduced uncertainty range.

Figure 11.

Full ensemble results with and without downhole control optimization.

The average computational time for each case run with FCV optimization in the Almakman study was 950 s on four CPUs, compared to 500 s for the base case without optimization. FCV settings were optimized on a monthly basis, resulting in a computational time ratio of 1.8 between the optimized and base cases.

7. Reservoir Management Case Studies

This section presents three applications of instantaneous optimization methods to evaluate the impact of FCVs on reservoir forecasts using real reservoir models.

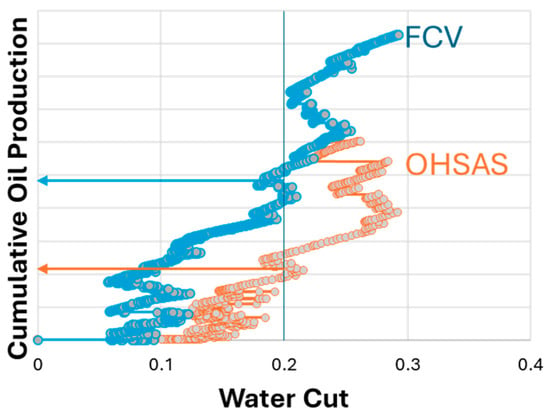

7.1. Delaying the Onset of High Water Cut at the Sector Level

This case study examines a large onshore carbonate reservoir composed of multiple units with diverse petrophysical properties, developed using a combination of peripheral and infill water injection. A major operational challenge is sustaining production as water cut increases, particularly since gas-lift efficiency declines sharply when water cut exceeds 30%, resulting in lower well productivity. To mitigate this, horizontal wells in a selected sector were completed with three equally spaced flow control devices each. A hybrid optimization strategy was employed, combining proactive measures to delay water breakthrough with reactive adjustments to restrict water production post-breakthrough. This approach enabled subsurface control and optimization that nearly doubled oil production rates prior to reaching the critical water-cut threshold, significantly extending the productive lifespan of the wells.

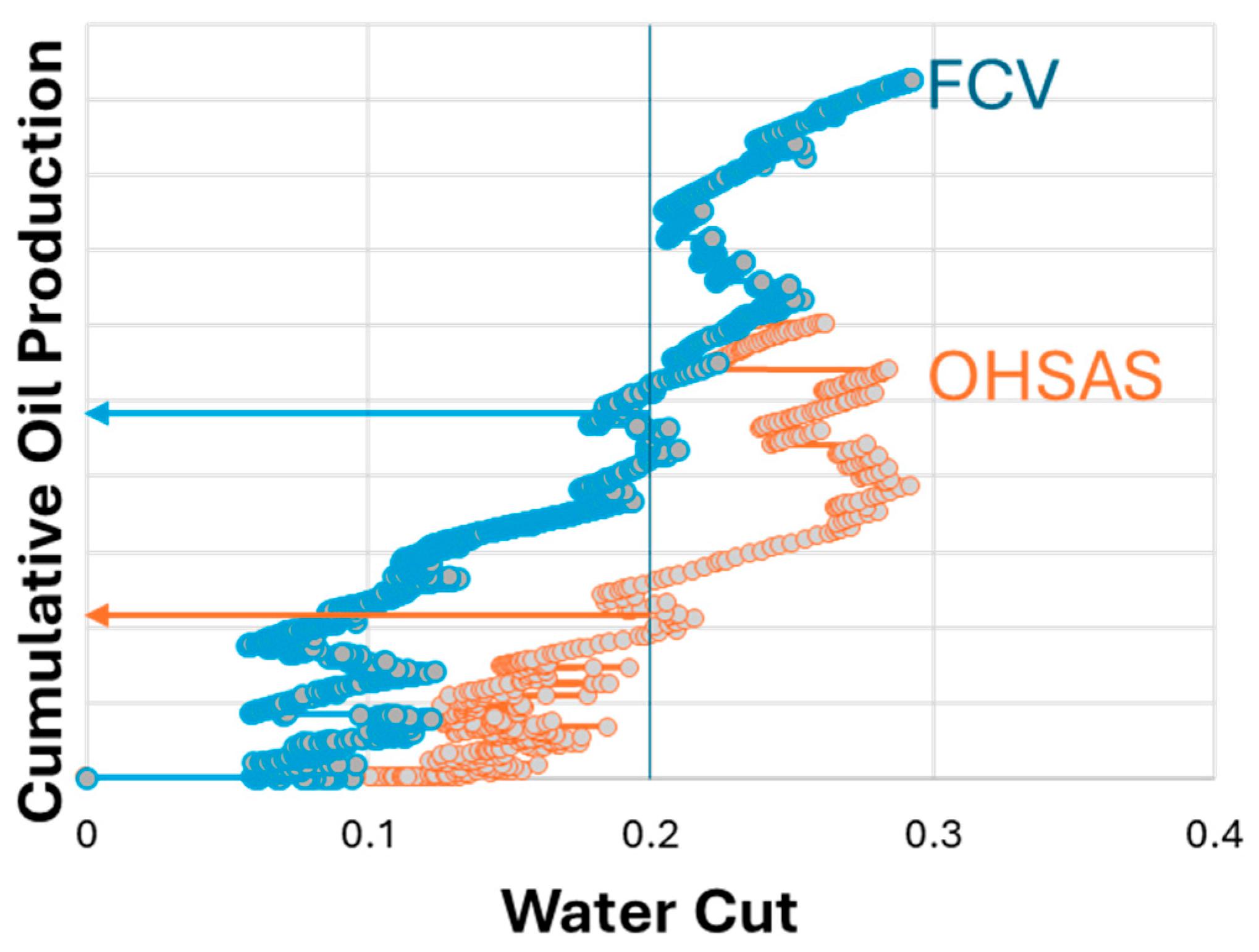

Simulation results indicated that while optimizing flow control valves (FCVs) at the single-well level enhances individual well performance, it does not substantially affect overall field recovery. In contrast, deploying FCVs across multiple wells (60+) yields a significant improvement in total field oil recovery. Figure 12 presents a cross-plot of water cut versus cumulative production for wells equipped with FCVs, demonstrating that cumulative oil produced at 20% water cut more than doubled compared to wells without FCVs.

Figure 12.

Cumulative oil production vs. water cut for a collection of wells in a carbonate reservoir with and without FCVs. OHSAS: open-hole stand-alone screen. The arrows indicate the cumulative oil production when the water cut reaches 20% for the two cases.

7.2. Enhancing Production and Injection Efficiency in a Mature Offshore Field

In this offshore brownfield redevelopment, the asset team explored strategies to revitalize a depleted North Sea reservoir composed of the heterogeneous BRENT Group formations. Key challenges included differential depletion and fluid bypass through high-permeability zones. Simply optimizing production wells proved inadequate to meet recovery goals; therefore, a dual approach was adopted, simultaneously optimizing both production and injection wells to improve flood conformance and maximize sweep efficiency. This integrated control strategy significantly enhanced oil recovery and overall flooding performance compared to conventional methods.

The field’s main geological units are the Rannock, Etive, and Ness formations, with the Ness formation exhibiting notably higher permeability and thickness. Historically, field development led to preferential depletion of the Ness, as injection fluids migrated along the path of least resistance. Optimizing only the production wells was insufficient due to high development costs and inefficiency in accessing bypassed oil. Introducing downhole control to injection wells enabled better distribution of injected water into the tighter Rannock and Etive formations, driving oil that would otherwise be bypassed toward the producers. Application of a flow balancing strategy (Equation (4)) on injection wells resulted in a 27% increase in oil production, a 48% decrease in water production, and a 37% reduction in water injection volumes relative to the base case.

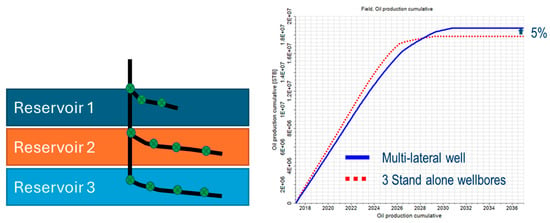

7.3. Replacing Three Separate Boreholes with a Single Multi-Lateral Well

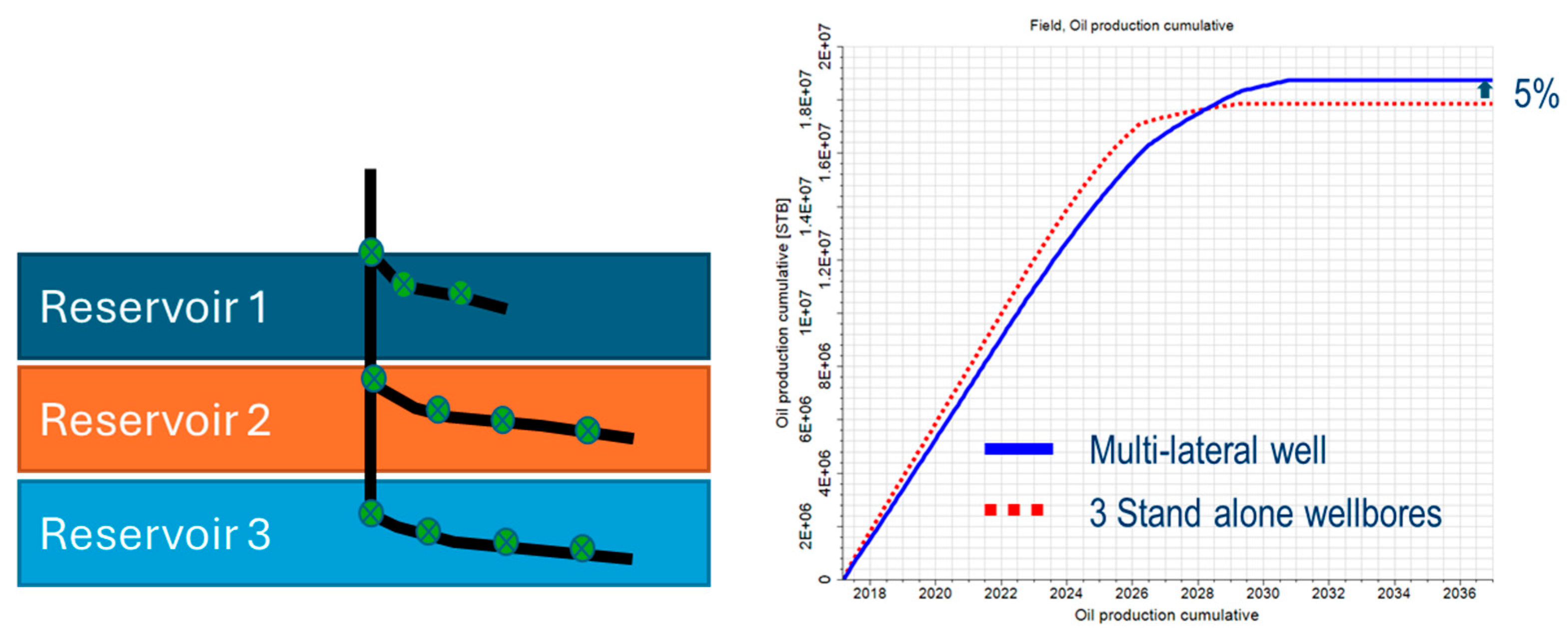

This case study concerns an offshore field where a limited number of drilling slots constrained the ability to maximize reservoir contact. The target development required access to three separate reservoirs containing fluids of different compositions and contrasting petrophysical properties, which could not be commingled due to a high risk of crossflow. A multi-lateral well design was evaluated as an alternative to drilling three individual boreholes (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

(Left): a schematic of the multi-lateral well. (Right): simulation results comparing the cumulative oil production for the multi-lateral and the combined three stand-alone wells.

Flow control valves were implemented for junction control and in-lateral water and gas management. Simulation results demonstrated that the single multi-lateral well equipped with FCVs achieved performance comparable to the combined production from three separate wells. This outcome highlighted the potential of FCVs to deliver efficient reservoir management solutions while meeting drilling and surface facility constraints. The FCV optimization was focused on eliminating crossflow and maximizing production. It achieved similar results as the combined stand-alone wells (Figure 13).

8. Discussion

The comparison conducted on the OLYMPUS model (Figure 3) demonstrates that short-term optimization objectives can be handled efficiently through local, timestep-driven optimizers. In the Almakman study, for example, the average CPU time for locally optimized cases was 971 s using eight-way parallel processing, compared to 540 s for the base cases—a modest increase in computational cost (approximately 1.8×) relative to the performance gains achieved. Because local optimization requires only a single simulation run per realization, it also reduces data handling complexity compared to global optimization workflows. However, it is important to note that local methods optimize production only at fixed points in time and do not guarantee convergence to a global optimum. Earlier work [8] showed that purely instantaneous optimization can, in some cases, deliver inferior results relative to simpler operational strategies. The results of this study demonstrate that high-frequency, short-term optimization steps can be implemented efficiently and are adequate for assessing the potential value of subsurface control valves.

The OLYMPUS benchmark further highlights the distinct behaviors of reactive and proactive strategies. Reactive optimization primarily targets the economic objective of maximizing short-term cash flow by penalizing unwanted water production and dynamically choking high water-cut zones. The degree of choking depends on the relative weighting of oil price versus water handling costs, meaning that adjusting these economic parameters leads to different optimization outcomes. Proactive streamline-based optimization, on the other hand, focuses on delaying water breakthrough by equalizing flood front arrival times across completions. Consequently, the proactive strategy achieved the highest flood efficiency, while reactive optimization delivered the largest improvements in NPV.

Despite the reduction in water production achieved by both approaches, neither led to consistently higher ultimate oil recovery across all realizations compared to base cases. This observation is consistent with the distinction between pressure-controlled and rate-controlled production problems described by Brouwer and Jansen [33]. In pressure-controlled scenarios—where wells operate under minimum bottomhole or tubing head pressure constraints—FCVs alone may not improve overall recovery. Because FCVs impose additional pressure drop to selectively restrict certain zones, their full potential is realized in rate-controlled contexts, where increased drawdown can drive higher oil production. Supplementary measures such as enhanced injection or artificial lift may be necessary to unlock these gains.

The Almakman case study illustrates the value of downhole control to manage subsurface uncertainty (e.g., fractures or thief zones). In this context, FCVs provided an effective means of neutralizing the impact of highly conductive fractures, improving the P50 recovery profile and narrowing the uncertainty range compared to cases without downhole control. This capacity to reduce downside risk is a compelling argument for the use of FCVs in heterogeneous reservoirs.

Traditionally, completion optimization under uncertainty has aimed to define a robust, single sequence of valve settings that would improve performance across all realizations. While this approach provides clear operational guidance, in practice, reservoir models evolve as new data is acquired, often rendering precomputed control strategies obsolete. The configurable nature of FCVs makes them especially well-suited to reactive and proactive optimization approaches that adapt settings dynamically to each realization as conditions change.

Finally, the three reservoir management case studies underscore the versatility and strategic value of FCVs. Whether improving gas-lift performance in high water-cut settings, coordinating injection and production to enhance sweep efficiency in mature reservoirs, or enabling multi-lateral developments in slot-constrained fields, flow control devices consistently proved to be an enabler of higher-value, more flexible field development strategies.

Owing to their computational efficiency, instantaneous FCV optimization workflows can also guide the design and configuration of passive and autonomous flow control devices. As shown by Ahmed Elfeel et al. [34], insights derived from the optimization of active devices can be generalized to inform the optimal placement and sizing of other FCD types. Recent advances—such as the machine learning-aided optimization approach demonstrated by Ahdeema et al. [35]—are opening new avenues for rapid, data-driven decision making. Furthermore, the results of instantaneous optimization across multiple control steps can be compiled into comprehensive datasets that capture well configurations, reservoir states, and corresponding optimal solutions. These datasets can then be used to train machine learning algorithms to efficiently determine FCV settings, potentially eliminating the need for repeated full-physics simulations. Future research should further investigate these synergies, aiming to develop fully closed-loop optimization frameworks that integrate real-time model updating and automated control.

9. Conclusions

This work demonstrates that integrating reactive and proactive optimization strategies can significantly enhance the performance of intelligent flow control valves in reservoir management. Reactive optimization alone offers near-instantaneous adjustment of FCV settings to maximize short-term objectives, such as minimizing unwanted water and gas production. Proactive streamline-based optimization, in contrast, improves sweep efficiency and delays breakthrough events by equalizing flood-front arrival times across well zones. When combined, these strategies deliver higher NPV, improved reservoir drainage, and reduced uncertainty compared to static or purely reactive approaches.

The synthetic benchmarks and real-field case studies confirm that, while proactive optimization yields the greatest improvements in flood efficiency, reactive optimization delivers greater gains in immediate economic value under production constraints. Additionally, in fractured reservoirs with high geological uncertainty, downhole flow control demonstrably reduces the downside risks associated with highly conductive fractures and thief zones, and stabilizes recovery expectations.

Importantly, the efficiency of local, timestep-driven optimization workflows makes them practical for routine deployment within reservoir simulators without incurring the prohibitive computational costs of global optimization. As smart completion technologies and real-time data acquisition continue to evolve, the approaches outlined here can inform the design of next-generation control strategies, not only for active FCVs but also for passive and autonomous flow control devices. Future work should focus on extending this framework to integrate updated reservoir models in a fully closed-loop optimization environment and exploring its application to multi-well coordinated control in complex field developments.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Mohamed Ahmed Elfeel was employed by SLB. The author declares that the research was conducted independently and without any commercial or financial relationships that could be perceived as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Al-Khelaiwi, F.T.M. A Comprehensive Approach to the Design of Advanced Well Completions. Ph.D. Thesis, Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Eltaher, E.M.K. Modelling and Applications of Autonomous Flow Control Devices. Ph.D. Thesis, Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Satter, A.; Thakur, G.C. Integrated Petroleum Reservoir Management: A Team Approach; PennWell Books: Tulsa, OK, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Steen, E. An evolution from smart wells to smart fields. In Proceedings of the SPE Intelligent Energy International Conference and Exhibition, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–13 April 2006; p. SPE-100710. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Arnaout, I.H.; Al-Buali, M.H.; Al-Mubarak, S.M.; Al-Driweesh, S.M.; Zareef, M.A.; Johansen, E.S. Optimizing Production in Maximum Reservoir Contact Wells with Intelligent Completions and Optical Downhole Monitoring System. In Proceedings of the Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition and Conference, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 3–6 November 2008; p. SPE-118033. [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri, L.; Macdonald, J. How 24/7 real-time surveillance increases ESP run life and uptime. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Florence, Italy, 20–22 September 2010; p. SPE-134702. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khelaiwi, F.T.; Zarea, M.A.; Al-Khamis, M.N.; Al-Ghamdi, A.A.; Al-Amri, M.A. Intelligent-Field Technologies on a Mass Scale: Change for Efficiency Improvement. In Proceedings of the International Petroleum Technology Conference, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 10–12 December 2014; p. IPTC-17330. [Google Scholar]

- Naus, N.M.J.J.; Dolle, N.; Jansen, J.D. Optimization of commingled production using infinitely variable inflow control valves. SPE Prod. Oper. 2006, 21, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilib, F.A.; Jackson, M.D. Closed-loop feedback control for production optimization of intelligent wells under uncertainty. In Proceedings of the SPE Intelligent Energy International Conference and Exhibition, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 27–29 March 2012; p. SPE-150096. [Google Scholar]

- Vasper, A.; Mjos, J.E.; Duong, T.T. Efficient optimization strategies for developing intelligent well business cases. In Proceedings of the SPE Intelligent Energy International Conference and Exhibition, Aberdeen, UK, 6–8 September 2016; p. SPE-181062. [Google Scholar]

- Yeten, B.; Brouwer, D.R.; Durlofsky, L.J.; Aziz, K. Decision analysis under uncertainty for smart well deployment. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2004, 44, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.J.; Oliver, D.S. Smart-well production optimization using an ensemble-based method. SPE Reserv. Eval. Eng. 2010, 13, 884–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighat Sefat, M.; Elsheikh, A.H.; Muradov, K.M.; Davies, D.R. Reservoir uncertainty tolerant, proactive control of intelligent wells. Comput. Geosci. 2016, 20, 655–676. [Google Scholar]

- Alhuthali, A.H.; Oyerinde, A.; Datta-Gupta, A. Optimal waterflood management using rate control. SPE Reserv. Eval. Eng. 2007, 10, 539–551. [Google Scholar]

- Alhuthali, A.H.; Datta-Gupta, A.; Yuen, B.; Fontanilla, J.P. Field applications of waterflood optimization via optimal rate control with smart wells. SPE Reserv. Eval. Eng. 2010, 13, 406–422. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H.; Crumpton, P.I.; Schrader, M.L. Efficient general formulation approach for modeling complex physics. In Proceedings of the SPE Reservoir Simulation Conference, The Woodlands, TX, USA, 2–4 February 2009; p. SPE-119165. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, J.A.; Barkve, T.; Lund, Ø. Application of a multisegment well model to simulate flow in advanced wells. In Proceedings of the SPE Europec Featured at EAGE Conference and Exhibition, Leipzig, Germany, 8–12 June 1998; p. SPE-50646. [Google Scholar]

- Bouldin, B.; Verma, C.; Bellaci, I.; Black, M.; Dyer, S.; Algerøy, J.; De Oliveira, T.; Pan, Y. Prototype test of an all-electric intelligent-completion system for extreme-reservoir-contact wells. SPE Drill. Complet. 2014, 29, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SLB. Manara System Station [Video]. Available online: https://www.slb.com/videos/manara-system-station (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Cullick, A.S.; Heath, D.; Narayanan, K.; April, J.; Kelly, J. Optimizing multiple-field scheduling and production strategy with reduced risk. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Denver, CO, USA, 5–8 October 2003; p. SPE-84239. [Google Scholar]

- Litvak, M.; Onwunalu, J.; Baxter, J. Field development optimization with subsurface uncertainties. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Denver, CO, USA, 30 October–2 November 2011; p. SPE-146512. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, K. Optimal allocation procedure for gas-lift optimization. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2010, 49, 2286–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, A.C.A.; Booth, R.; Bertolini, A.; Prange, M.; Bailey, W.J.; Teixeira, G.; Emerick, A.; Pacheco, M.A. Proactive and reactive strategies for optimal operational design: An application in smart wells. In Proceedings of the Offshore Technology Conference Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 27–29 October 2015; p. D011S009R006. [Google Scholar]

- Tonkin, T.G.; Watanabe, S.; Worthington, M.; Ahmed Elfeel, M. Method and SYSTEM for reactively Defining Valve Settings. U.S. Patent 11,585,192, 21 February 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, S.; Bratvedt, F.; Worthington, M.; Tonkin, T.G. Streamline Based Creation of Completion Design. U.S. Patent 12,146,395, 19 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Addiego-Guevara, E.A.; Jackson, M.D.; Giddins, M.A. Insurance value of intelligent well technology against reservoir uncertainty. In Proceedings of the SPE Improved Oil Recovery Conference, Tulsa, OK, USA, 19–23 April 2008; p. SPE-113918. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, R.M.; Della Rossa, E.; Emerick, A.A.; Hanea, R.G.; Jansen, J.D. Overview of the Olympus field development optimization challenge. In Proceedings of the ECMOR XVI—16th European Conference on the Mathematics of Oil Recovery, Barcelona, Spain, 3–6 September 2018; Volume 2018, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed Elfeel, M.; Ali, S.; Giddins, M.A. Efficient optimization of field management strategies in reservoir simulation. In Proceedings of the SPE Reservoir Characterisation and Simulation Conference and Exhibition, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 17–19 September 2019; p. D011S005R001. [Google Scholar]

- Senger, R.K.; Lucia, F.J.; Kerans, C.; Ferris, M.; Fogg, G.E. Geostatistical/Geological Permeability Characterization of Carbonate Ramp Deposits in Sand Andres Outcrop, Algerita Escarpment. In Proceedings of the SPE Permian Basin Oil and Gas Recovery Conference, Midland, TX, USA, 18–20 March 1992; p. SPE-23967. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, J.W., Jr.; Ruppel, S.C.; Ward, W.B. Geostatistical analysis of permeability data and modeling of fluid-flow effects in carbonate outcrops. SPE Reserv. Eval. Eng. 2000, 3, 292–303. [Google Scholar]

- Kerans, C.; Lucia, F.J.; Senger, A.R. Integrated characterization of carbonate ramp reservoirs using Permian San Andres Formation outcrop analogs. AAPG Bull. 1994, 78, 181–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed Elfeel, M.O.; Al-Dhahli, A.; Jiang, Z.; Geiger, S.; Van Dijke, M.I. Effect of rock and wettability heterogeneity on the efficiency of WAG flooding in carbonate reservoirs. In Proceedings of the SPE Reservoir Characterisation and Simulation Conference and Exhibition, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 16–18 September 2013; p. SPE-166054. [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer, D.R.; Jansen, J.D. Dynamic optimization of waterflooding with smart wells using optimal control theory. SPE J. 2004, 9, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed Elfeel, M.; Goh, G.; Biniwale, S. Advanced Completion Optimization ACO: A Comprehensive Workflow for Flow Control Devices. In Proceedings of the International Petroleum Technology Conference, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 23–25 March 2021; p. D012S045R062. [Google Scholar]

- Ahdeema, J.; Moradi, A.; Haghighat Sefat, M.; Muradov, K.; Moldestad, B.M. Bridging the performance gap between passive and autonomous inflow control devices with a hybrid dynamic optimization technique integrating machine learning and global sensitivity analysis. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 240, 213037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.