Abstract

Scrap steel is known to influence the fluid flow characteristics of the melt pool in converter steelmaking. However, few studies have considered the effects of the scrap steel charging structure. In this study, a physical model of a 1:8.8 steel–scrap–gas three-phase flow converter was established to investigate the effects of scrap steel state, distribution, material type and shape on the fluid flow characteristics of the converter melt pool. The velocity distribution within the molten pool was measured using particle image velocimetry, while mixing time under various operating conditions was determined using the stimulus–response method. Considering the melting behaviour of scrap steel and the gas utilisation rate comprehensively, the results indicate that when scrap steel is arranged in a uniform position at the bottom of the converter—comprising 90% medium scrap in rectangular scrap and 10% heavy scrap in thin-plate form—and the gas flow rate is 750 m3/h, the overall dynamic conditions of the melt pool are optimal. At this time, the mixing time is 68.2 s (a reduction of up to 45.4%), average velocity is 0.117 m/s (a maximum increase of 207.9%) and turbulent energy dissipation rate is 0.0266 m2/s3 (a maximum increase of 141.8%). Finally, a relationship was established between stirring power and mixing time at different scrap steel charging structures, providing a methodological reference and data support for optimising the charging structure of scrap steel and efficiently using scrap steel in converters.

1. Introduction

Long-process converter steelmaking emits approximately 3–4 times more CO2 per ton of steel than short-process electric furnace steelmaking [1,2]. The growing availability of scrap steel as a green feedstock creates a more favourable structure for decarbonising converter-based production. According to a previous study, producing 1 ton of steel from scrap—rather than from iron ore—can save approximately 1.65 tons of iron ore; can cut energy use by 350 kg of standard coal; and can result in reductions of nearly 1.6 tons of CO2 [3], 80% of exhaust gases [4] and 3 tons of solid waste.

To increase the use of scrap steel in converter steelmaking, many researchers have investigated its melting behaviour within converters [5,6,7]. These investigations have primarily relied on high-temperature thermal simulations, numerical simulations, mathematical modelling and water simulation experiments [8,9,10,11]. Collectively, this body of research has focused on key aspects such as the melting mechanism, melting rate, melting morphology and the heat and mass transfer coefficients of scrap steel [12,13,14,15]. Their findings have revealed that the melting of scrap steel in the converter melt pool is primarily driven by the formation of temperature and concentration boundary layers on the surfaces of molten iron and scrap steel [16,17]. These boundary layers are influenced by coupled heat and mass transfer between the two phases [18,19]. Based on this understanding, the melting process can be divided into four stages: solidification layer formation, melting of the solidification layer, carburisation and steady-state melting [20,21]. Building on these findings, researchers have identified several factors that influence the melting rate of scrap steel. These include the temperature and carbon content of the molten iron, as well as the size, carbon content, shape, preheating temperature and porosity of the scrap steel itself [22,23]. Additionally, the degree of stirring in the converter melt pool plays a key role in determining both the melting rate and morphology of the scrap steel [24,25]. According to findings, the melting rate is directly proportional to the temperature and carbon content of the molten iron, the stirring force of the melt pool and the scrap’s own carbon content, while it is inversely proportional to scrap size [26,27]. In a related study, Xi [28] reported that when the porosity of scrap steel reaches 0.84, the melting time of multiple scrap pieces is comparable to that of a single piece.

Additionally, researchers [29,30] have used ice cubes to simulate scrap steel, based on similarity principles, and have investigated the effect of scrap steel addition on the mixing time of the converter melt pool through water simulation experiments. Their findings indicate that, after scrap steel is added to the converter, the mixing time of the melt pool is strongly influenced by the quantity, type and distribution of scrap, as well as the bottom-blowing flow rate. Subsequent studies have shown that light and heavy scrap steel exert markedly different effects on the mixing time of the melt pool [31]. For light scrap steel, the dominant factors influencing mixing time are the scrap amount and bottom-blowing flow rate, whereas for heavy scrap, distribution plays a more prominent role. Specifically, a uniform or inclined scrap distribution has been found to be more effective in shortening the melt pool mixing time. Moreover, during scrap addition to the converter, an excessively high bottom-blowing flow rate hinders effective stirring of the molten pool. Although these findings contribute valuable insights, most existing studies have concentrated on the melting behaviour of scrap steel, paying relatively little attention to the influence of scrap addition on the fluid flow characteristics of the converter melt pool. Even fewer investigations have explored the effect of different scrap charging methods on these flow dynamics.

Against this background, the current study investigated a 300-ton converter using physical simulation to establish a 1:8.8 two-dimensional water model of molten steel–scrap–gas three-phase flow. It examined how the distribution, state, material type and shape of scrap steel influence the fluid flow characteristics of the converter melt pool. The flow field distribution and mixing time of the melt pool under various operating conditions were recorded using particle image velocimetry (PIV) and stimulus–response techniques. Additionally, the velocity, turbulent characteristics and mixing time were compared and analysed across different scrap charging structures. Overall, the findings offer a theoretical basis for the classification of scrap steel processing and its effective utilisation in converter operations.

2. Materials and Methods

- Experimental Principle

A 1:8.8 physical water model, developed based on a 300-ton converter at a steel plant, was established to investigate the influence of scrap steel state, distribution, material type and shape on the flow field and mixing behaviour of the converter melt pool (the model did not consider the melting process of the scrap steel). This model was constructed in accordance with the principle of similarity [25,29]. Accordingly, compressed air was used to simulate bottom-blown argon gas and water was employed to represent molten steel. The physical properties of both the fluid prototype and the water model are presented in Table 1. According to the ‘approximate modelling method’ and ‘cold modelling method’ [32,33], when simulating the fluid flow characteristics of the converter melt pool, not only must we ensure geometric similarity between the converter prototype and model, but we also must ensure dynamic similarity of the fluid by ensuring that the (modified Froude number) in the similarity criterion is equal, as indicated in Equations (1)–(4) [25,29,33]:

where denote the feature dimensions of the model and prototype (m), respectively; represents the similarity ratio; denote the modified Froude numbers of the model and prototype, respectively; refer to the gas flow velocities of the model and prototype (m/s), respectively; denote the gas densities of the model and prototype (kg/m3), respectively; represent the liquid densities of the model and prototype (kg/m3), respectively; signify the gas flow rate of the model and prototype (Nm3/h); and g denotes gravitational acceleration (m/s2).

Table 1.

The physical properties of fluid [10,11,28].

Based on the similarity criterion, Equation (4) yields the following relationship between the gas flow rate of the bottom-blown gas in the model and prototype:

The bottom-blown gas flow rates for both the prototype and the water model are listed in Table 2. To present the experimental results more clearly, the bottom-blown gas flow rates have been categorised into different stages, as shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

The bottom gas flow rates of the prototype and model.

Table 3.

The classification stages of the bottom-blowing gas flow rate.

- Experimental Apparatus and Materials

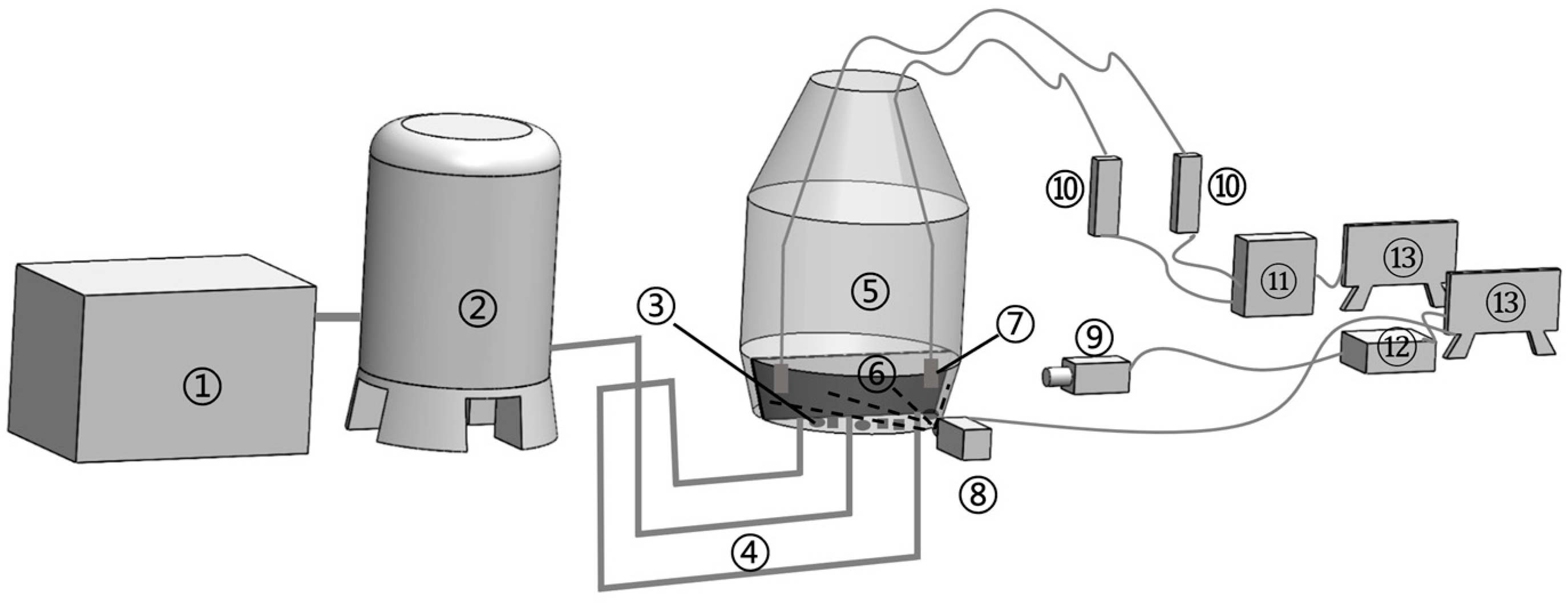

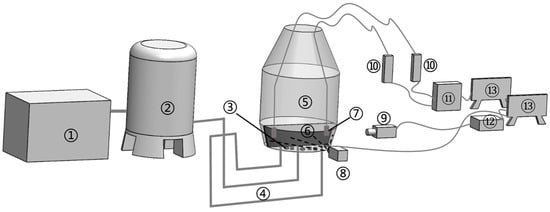

The physical model of the converter used in this study is illustrated in Figure 1. It consists of a gas supply system, a converter model, a PIV system and a DJ-800 data acquisition system. The shaded regions in the figure indicate the shooting surface. Components labelled ①–⑬ sequentially correspond to air compressors (Jiangsu Dailuo Medical Technology Co., Ltd., Jiangsu, China), gas storage tanks (Jiangsu Dailuo Medical Technology Co., Ltd., Jiangsu, China), scrap steel (Baoshan Iron & Steel Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), bottom-blowing nozzles (Tianchang Nanfang Organic Glass Factory, Anhui, China), the converter (Tianchang Nanfang Organic Glass Factory, Anhui, China), the shooting surface, electrode probes (Shanghai Yidian Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), charge-coupled device (high-speed CMOS) cameras (Hefei Zhongke Junda Shijie Technology Co., Ltd., Anhui, China), lasers (Hefei Zhongke Junda Shijie Technology Co., Ltd., Anhui, China), conductivity metres (China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research, Beijing, China), the DJ-800 system (China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research, Beijing, China), synchronisers (Hefei Zhongke Junda Shijie Technology Co., Ltd., Anhui, China) and computers (Dell (China) Co., Ltd., Xiamen, China).

Figure 1.

The schematic diagram of the physical model experimental setup.

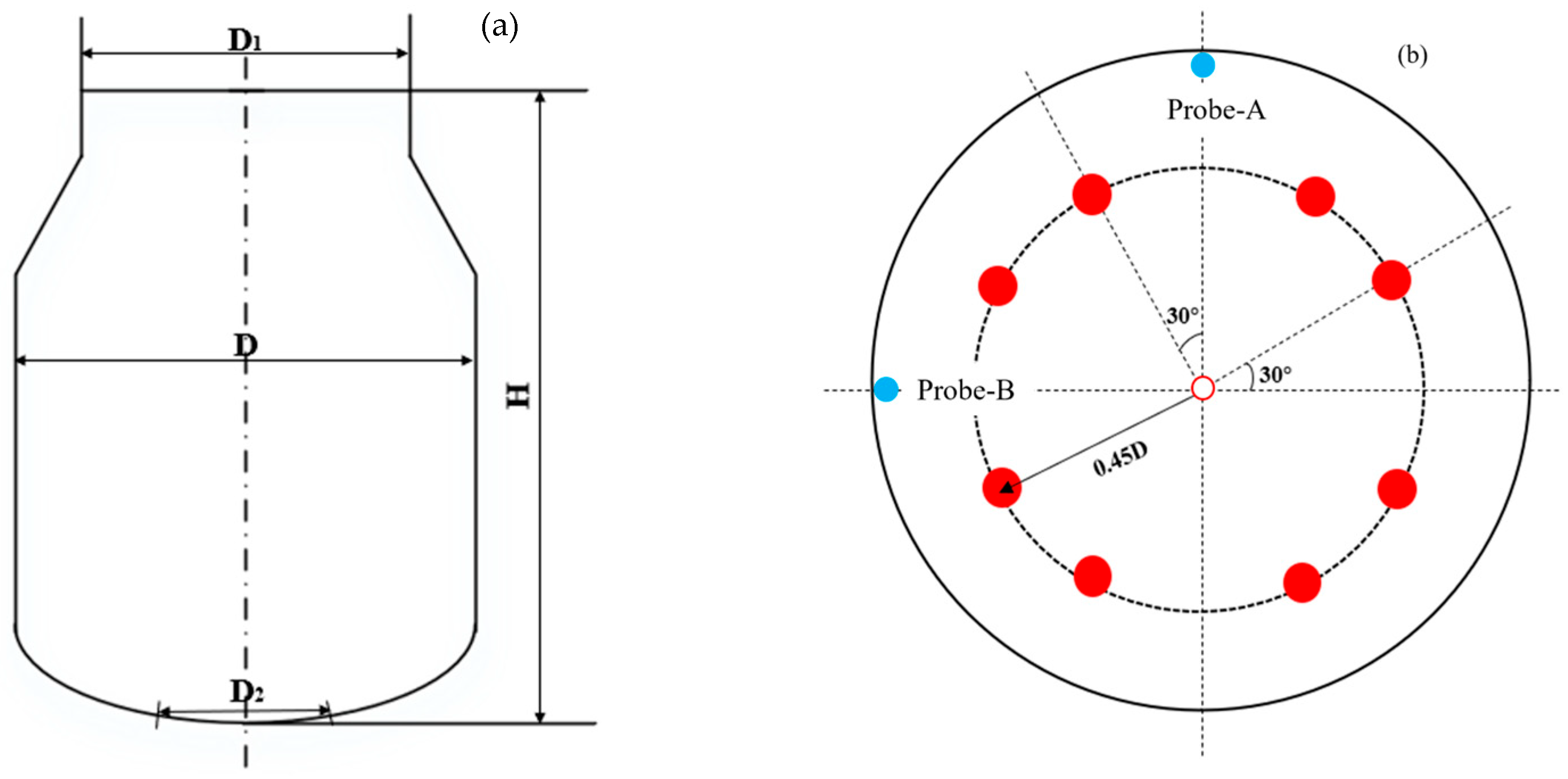

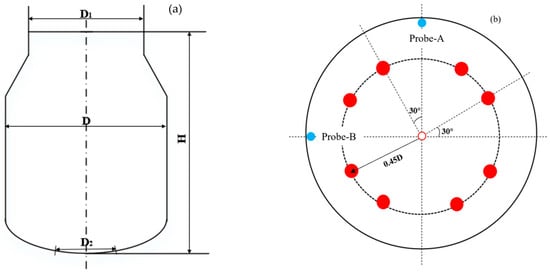

Moreover, a scaled physical model of the converter was fabricated using organic glass. To simulate the scrap steel, polyurethane of varying densities was selected based on the measured density and material characteristics of actual scrap samples from the steel plant. The scrap parameters are provided in Table 4. Figure 2 presents the schematic layout of the converter and the configuration of the bottom-blowing nozzles. A total of eight nozzles are arranged at a distance of 0.45D (where D is the diameter of the melt pool). These nozzles are oriented at a 30° angle relative to the ear axis and also form a 30° angle with the centreline perpendicular to the ear axis. The principal geometric parameters of the converter prototype and the physical model are summarised in Table 5.

Table 4.

Scrap parameters.

Figure 2.

The schematic diagram of the converter and arrangement of the bottom-blowing nozzle: (a) converter model; (b) layout schemes for eight bottom-blowing nozzles.

Table 5.

The principal geometric parameters of prototype and model.

When scrap steel is added to the converter, differences in density cause it to assume various states within the melt pool, such as hovering or settling to the bottom. In cases where the scrap settles, its distribution at the furnace bottom may vary depending on the addition location or the converter’s shaking operation. These distributions include concentrated accumulation at the bottom, uniform coverage or localisation to one side of the furnace base. Moreover, the type of scrap steel added to the converter affects the flow field distribution and mixing behaviour of the melt pool. For example, the proportion and shape of heavy scrap can influence these outcomes. To investigate these effects, this study designed experimental plans based on different scrap steel charging structures, examining how scrap state, distribution, material type and shape affect the velocity, mixing time and turbulent characteristics of the converter melt pool. The experimental scheme is detailed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Experimental scheme.

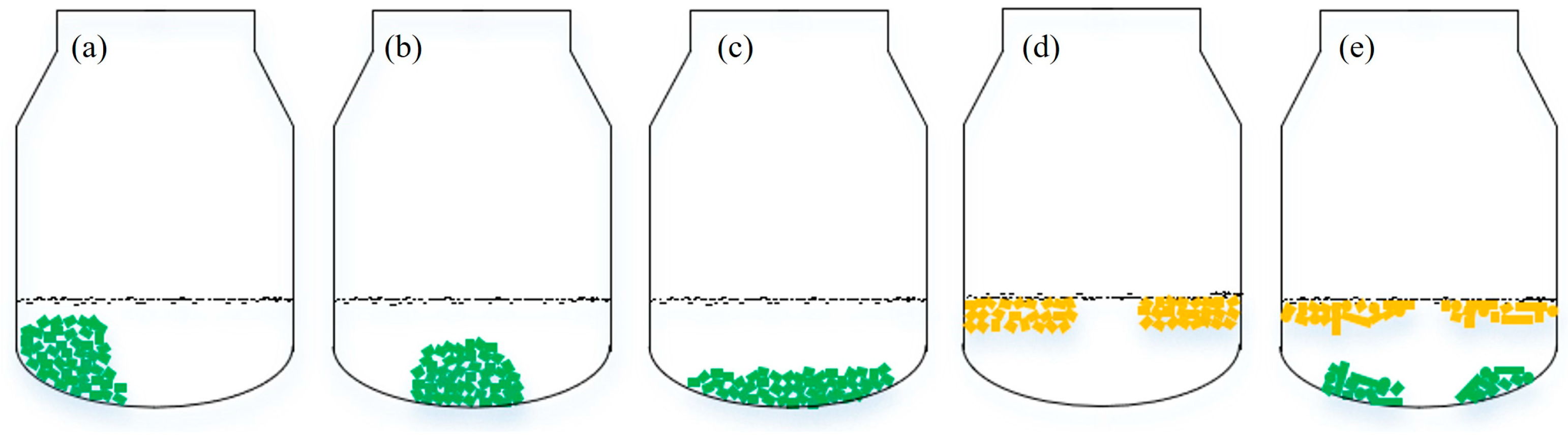

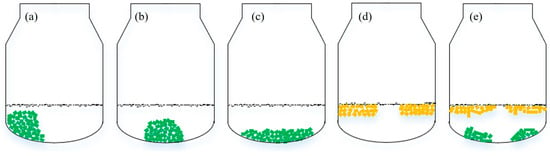

Figure 3 illustrates the various states of scrap steel within the converter: Figure 3a–c show inclined, concentrated and uniform distributions of settled scrap; Figure 3d depicts hovering scrap steel; and Figure 3e shows different shapes of both hovering and settled scrap steel.

Figure 3.

The various states of scrap steel within the converter: (a) inclined, (b) concentrated, (c) uniform, (d) hovering, (e) hovering and settling.

2.1. Flow Velocity Measurement

PIV is a non-contact, transient, full-field velocity measurement technique based on optical principles. The measurement system comprises a high-frequency pulsed laser, high-speed CMOS camera imaging equipment, timing controller, data processing terminal and optical transmission components. During the experimental measurement of the converter flow field, tracer particles with a density matching that of the fluid were first introduced into the melt pool. Before measurement, tiny tracer particles with a density matched to the fluid were uniformly seeded into the physical model. For the PIV measurement, a synchronizer (timing controller) was employed to precisely coordinate the pulsed laser sheet illumination and the high-speed CMOS camera’s exposure. The laser illuminated the monitored area (shaded in Figure 1) at precise intervals. Operating in double-frame mode, the high-speed CMOS camera captured sequential image pairs of the tracer particles at a frequency of 1.92 Hz, resulting in 48 image pairs over a period of 25 s for each experimental condition. These image pairs were transferred to the computer via a high-speed interface. The velocity distribution/fields of the flow field under different operating conditions were finally calculated through cross-correlation analysis of the sequential image pairs using dedicated PIV software (PIV-3D3C-STD520). The PIV system used in this experiment was manufactured by Hefei Zhongke Junda Shijie Technology Co., Ltd. Hefei, China. The specific system model was the Qianyanlang PIV-3D3C-STD520, which primarily consisted of a laser (a dual-pulse Nd:YAG laser with a wavelength of 532 nm and a dual-pulse energy of 30 mJ), four high-speed cameras (Qianyanlang X150 high-speed CMOS cameras with a full-frame resolution of 2560 × 1920 pixels, a full-frame acquisition rate of 2000 FPS and an inter-frame interval of 400 ns) and PIV analysis software (RFlow3). Tecplot360 software (2024R1) was used for post-processing the images and performing a quantitative analysis of the flow velocity distribution under various scrap steel configurations. Based on the two-dimensional PIV velocity field data, the turbulent kinetic energy and energy dissipation rate under each operating condition were further calculated using Equations (6) and (7) [34]:

where is the turbulent kinetic energy (m2/s2), is the turbulent kinetic energy dissipation rate (m2/s3) and t denotes time (s). Further, and denote the radial and vertical pulsation velocities, respectively, and are calculated using Equations (8) and (9) [34].

In these equations, denotes the mean velocity (m/s) and the subscripts r and v refer to the radial and vertical directions, respectively.

2.2. Mixing Time Measurement

The mixing time was determined using the stimulus–response method. The experimental system comprised a converter water model, a gas supply unit, a flow metre, electrode probes, a conductivity metre, a DJ-800 data acquisition system and a computer, as illustrated in Figure 1. The procedure was as follows:

- (1)

- Once the gas flow in the melt pool stabilised, 35 mL of saturated NaCl solution (Shanghai Bohr Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was rapidly injected as a tracer.

- (2)

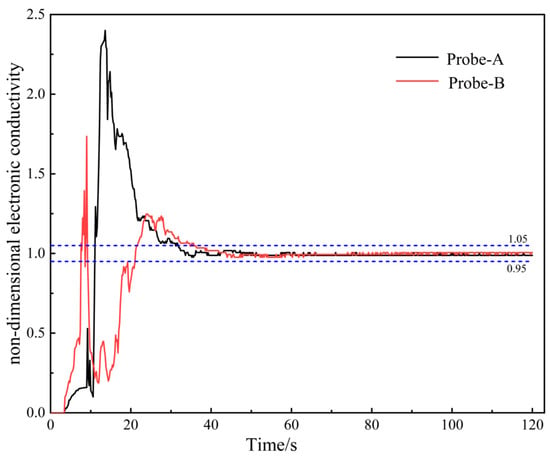

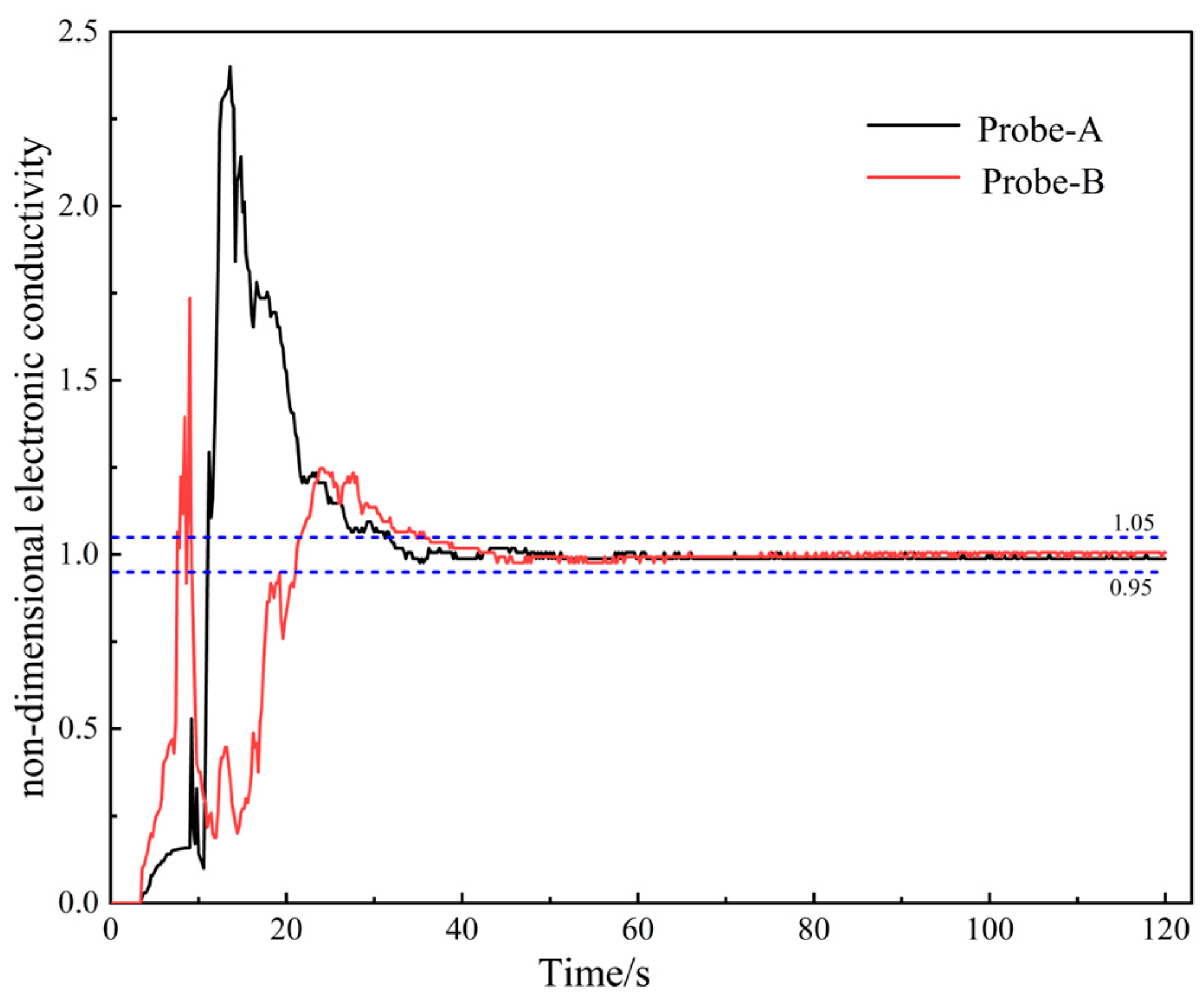

- The electrode probe continuously monitored changes in conductivity. These data were transmitted to the DJ-800 acquisition system via the conductivity metre and converted into digital signals. Figure 4 presents the dynamic conductivity curves recorded by the two probes during the water model experiments.

- (3)

- When the conductivity fluctuation remained within ±5% of the final equilibrium value, the melt pool was considered to have reached a mixed state. The mixing time was defined as the interval between tracer injection and the attainment of this mixed state.

- (4)

- Each test was repeated three times to minimise random error, and the average value was taken as the mixing time for that probe, as defined in Equation (10) [10]. Owing to the use of two electrode probes, the final mixing time was calculated as the average of the two measured values.

Figure 4.

The dynamic conductivity curves over time.

Figure 4.

The dynamic conductivity curves over time.

3. Results

3.1. Impact of Scrap Steel State

3.1.1. Influence of Scrap Steel State on the Mixing Time of the Melt Pool

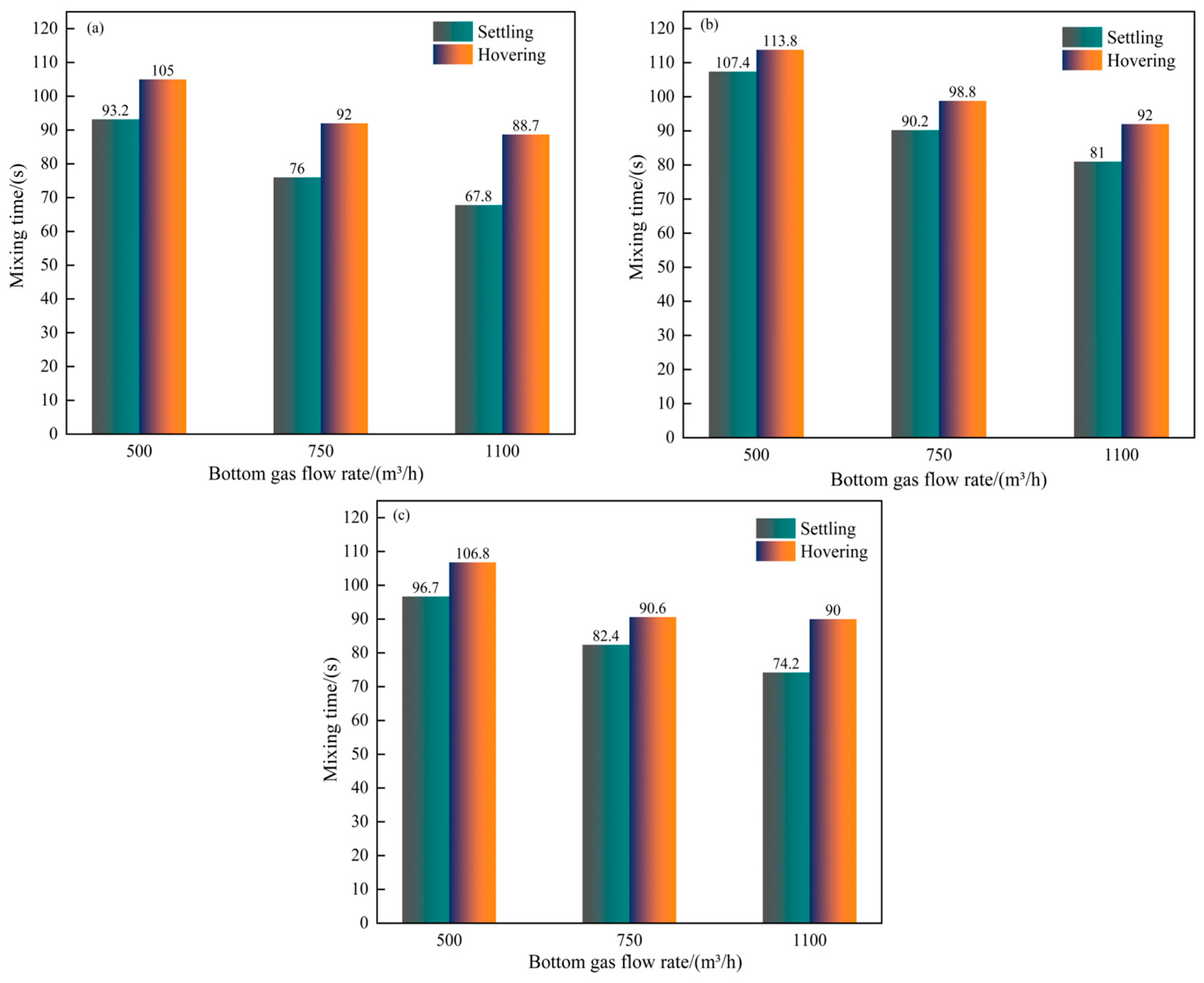

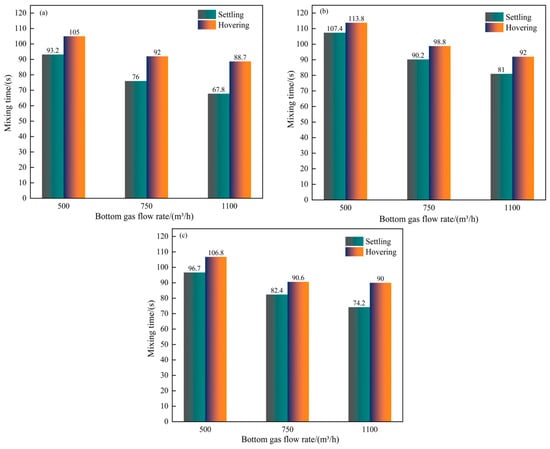

Figure 5 illustrates the relationship between the mixing time of the melt pool, the scrap steel state when the scrap ratio in the converter is 20% and the flow rate of bottom-blowing gas. The data indicate that the mixing time is shorter when the scrap steel is in a settling state. For instance, when settled scrap steel has a rectangular shape and the bottom-blowing gas flow rates are 500, 750 and 1100 m3/h, the mixing time is reduced by 11.8, 16 and 20.9 s, respectively, in the hovering state, representing reductions of 11.2%, 17.4% and 23.6%. This trend can be attributed to the fact that, when scrap steel settles at the bottom of the converter, it alters the path of the bottom-blown gas, increases the residence time of gas within the melt pool and strengthens the stirring force. These changes collectively contribute to a shorter mixing time.

Figure 5.

The relationship between the mixing time of the melt pool and scrap steel state: (a) cuboid; (b) cylindrical; (c) thin plate.

Moreover, the figure illustrates that increasing the bottom-blowing gas flow rate has a greater effect on reducing the mixing time of the molten pool when the scrap steel is in a settling state. For instance, when the scrap steel has a rectangular shape and the bottom-blowing gas flow rate increases from 500 m3/h to 750 m3/h, the reduction in mixing time is 18.5% in the settling state, compared to 12.4% in the hovering state. When the flow rate further increases from 750 m3/h to 1100 m3/h, the reduction in mixing time is 10.8% for the settling state, while it is only 3.6% for the hovering state.

Finally, the figure shows that among the three shapes of scrap steel—rectangular, thin plate and cylindrical—the rectangular form results in the shortest molten pool mixing time, followed by the thin plate, with the cylindrical form yielding the longest time. For example, when the bottom-blowing gas flow rate is 750 m3/h and the scrap steel is in a settling state, the mixing time with rectangular scrap is reduced by 7.8% and 15.7%, respectively, compared to the thin-plate and cylindrical forms. Therefore, when rectangular scrap steel is added to the converter in a settling state, the mixing performance of the molten pool is optimal.

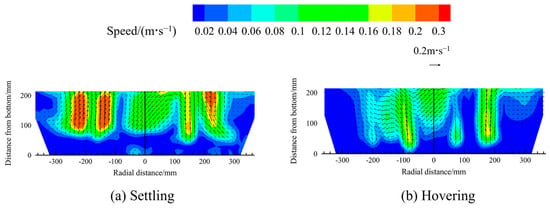

3.1.2. Influence of Scrap Steel State on the Velocity of the Melt Pool

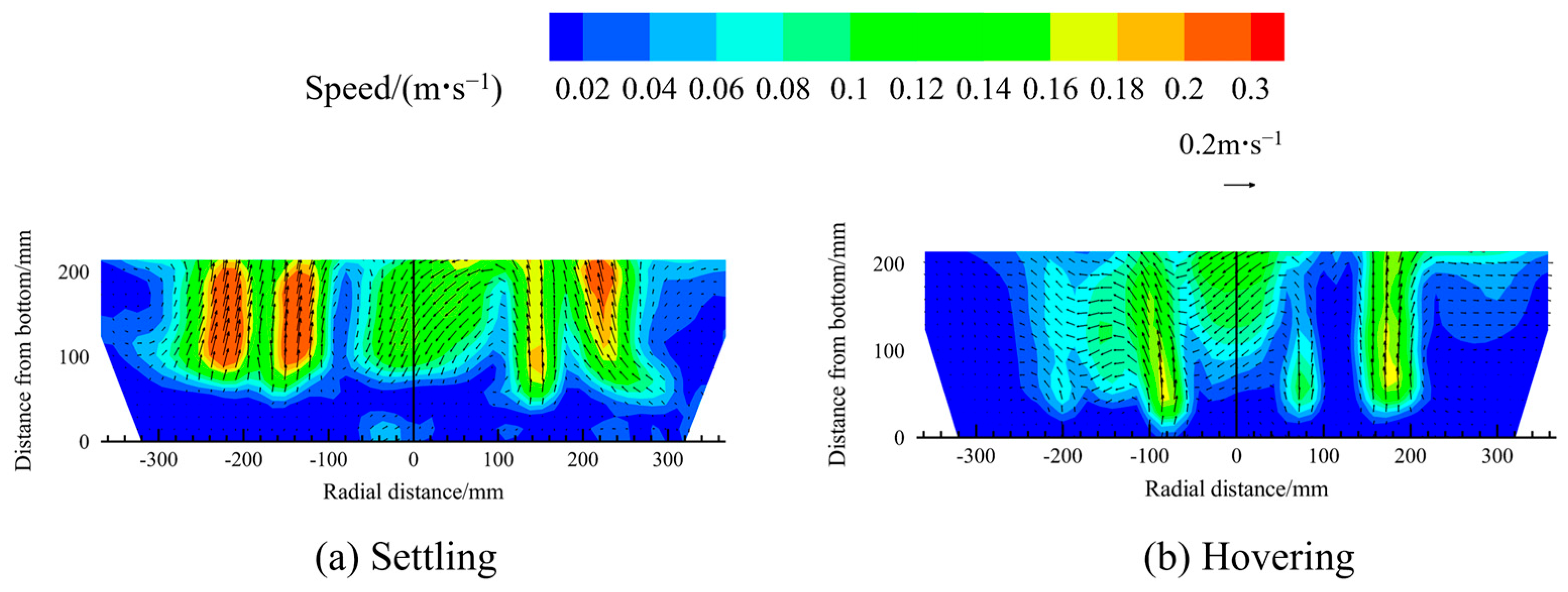

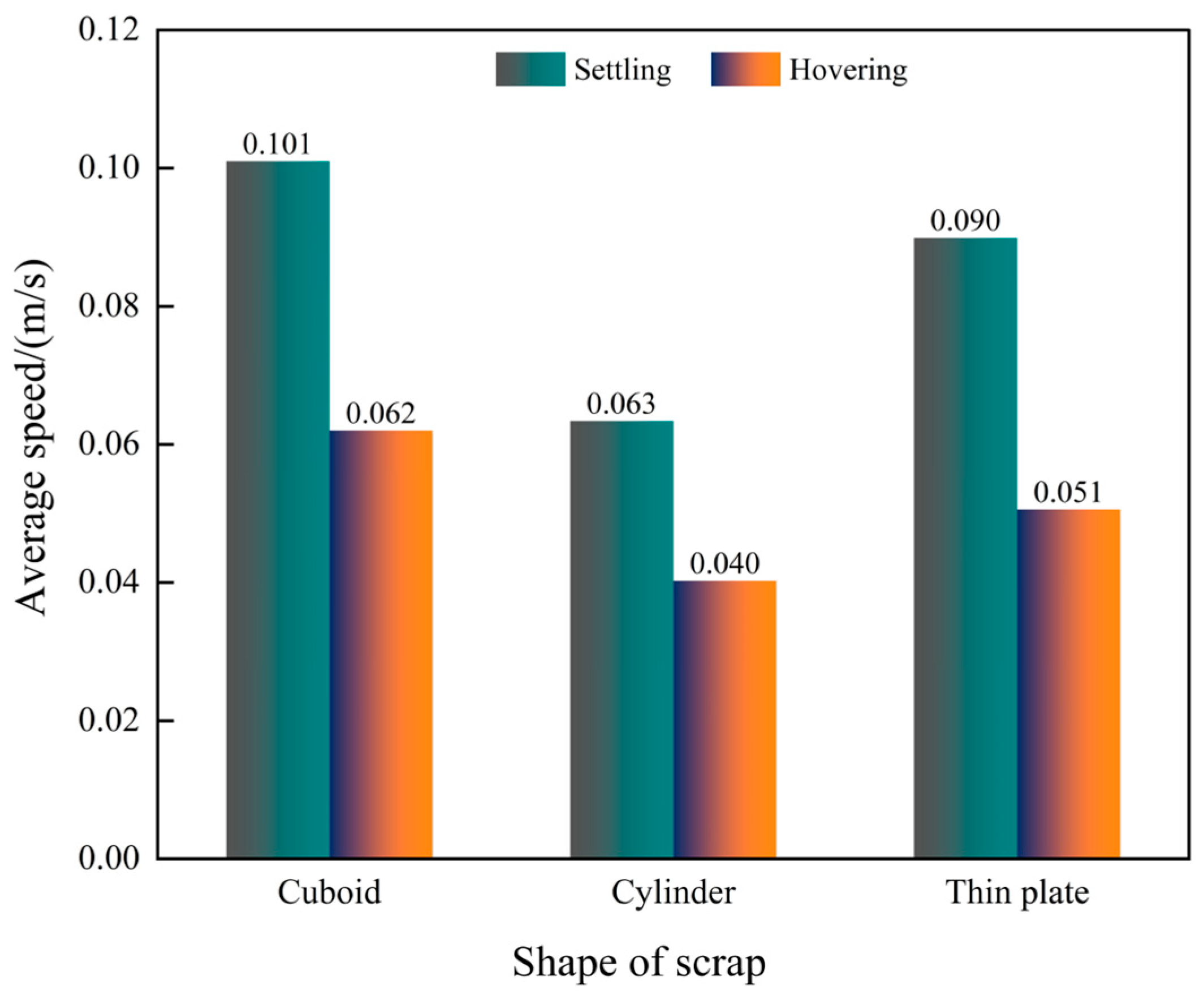

Figure 6 presents the contour maps of the velocity distribution in the melt pool when the scrap steel is in either a settling or a hovering state. In the cloud map, the colour gradient and arrow lengths indicate the magnitude of velocity. First, the velocity of the melt pool above the bottom-blowing nozzle is higher than that in other regions of the pool, as observed in the figure. Second, when the scrap steel is hovering in the molten steel, gas stirring begins closer to the bottom-blowing nozzle compared to that in the settling condition. However, under the settling condition, the melt pool velocity is greater. To quantitatively assess the influence of scrap steel state on average velocity in the melt pool, the velocity is calculated and statistically analysed under different scrap steel states, as depicted in Figure 7. When the scrap steel is shaped as a rectangular prism, the average melt pool velocity increases by 62.9% under the settling condition compared to that under the hovering condition. For cylindrical and thin-plate scrap steel, the respective increases are 57.4% and 77.7%. Furthermore, under the premise that the scrap steel is in a settled state, the average velocity when the scrap is in the shape of a rectangular prism is 60.3% higher than when it is cylindrical, and 12.2% higher than when it is in the form of a thin sheet. When the scrap is in a floating state, these values are 55% and 21.5%, respectively.

Figure 6.

The contour maps of the velocity distribution for different scrap steel states.

Figure 7.

The average velocity of the melt pool for different scrap steel states.

3.1.3. Influence of Scrap Steel State on the Turbulent Characteristics of the Melt Pool

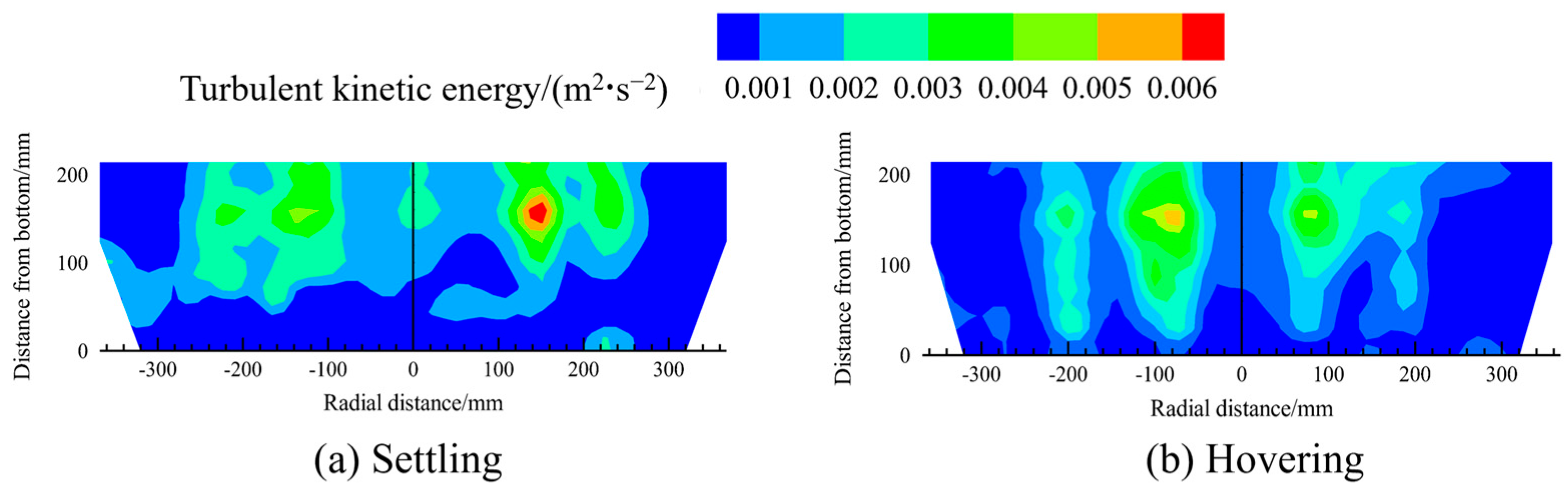

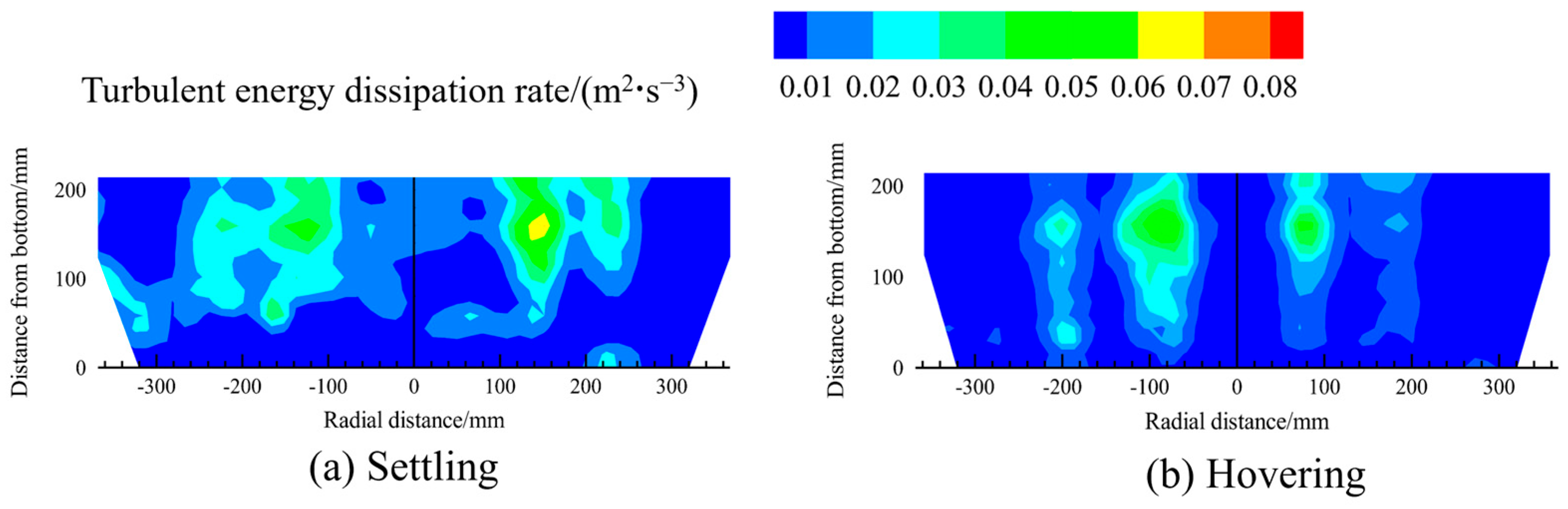

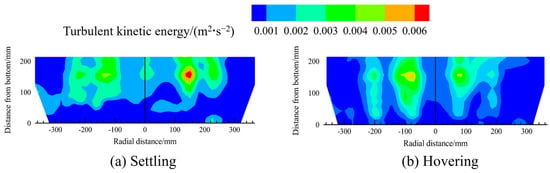

Figure 8 and Figure 9 illustrate the contour maps of the distribution of the turbulent kinetic energy and turbulent kinetic energy dissipation rates in the melt pool under different scrap steel states.

Figure 8.

The contour maps of the distribution of the turbulent kinetic energy in the melt pool for different scrap steel states.

Figure 9.

The contour maps of the distribution of the turbulent energy dissipation rate in the melt pool for different scrap steel states.

The distribution patterns of turbulent kinetic energy and its dissipation rate in the melt pool are consistent with the velocity distribution: both are higher above the bottom-blowing nozzle compared to other regions. In addition, the figures indicate that when the scrap steel is in a settling state, the turbulent kinetic energy and dissipation rate in the melt pool are greater than in the hovering state.

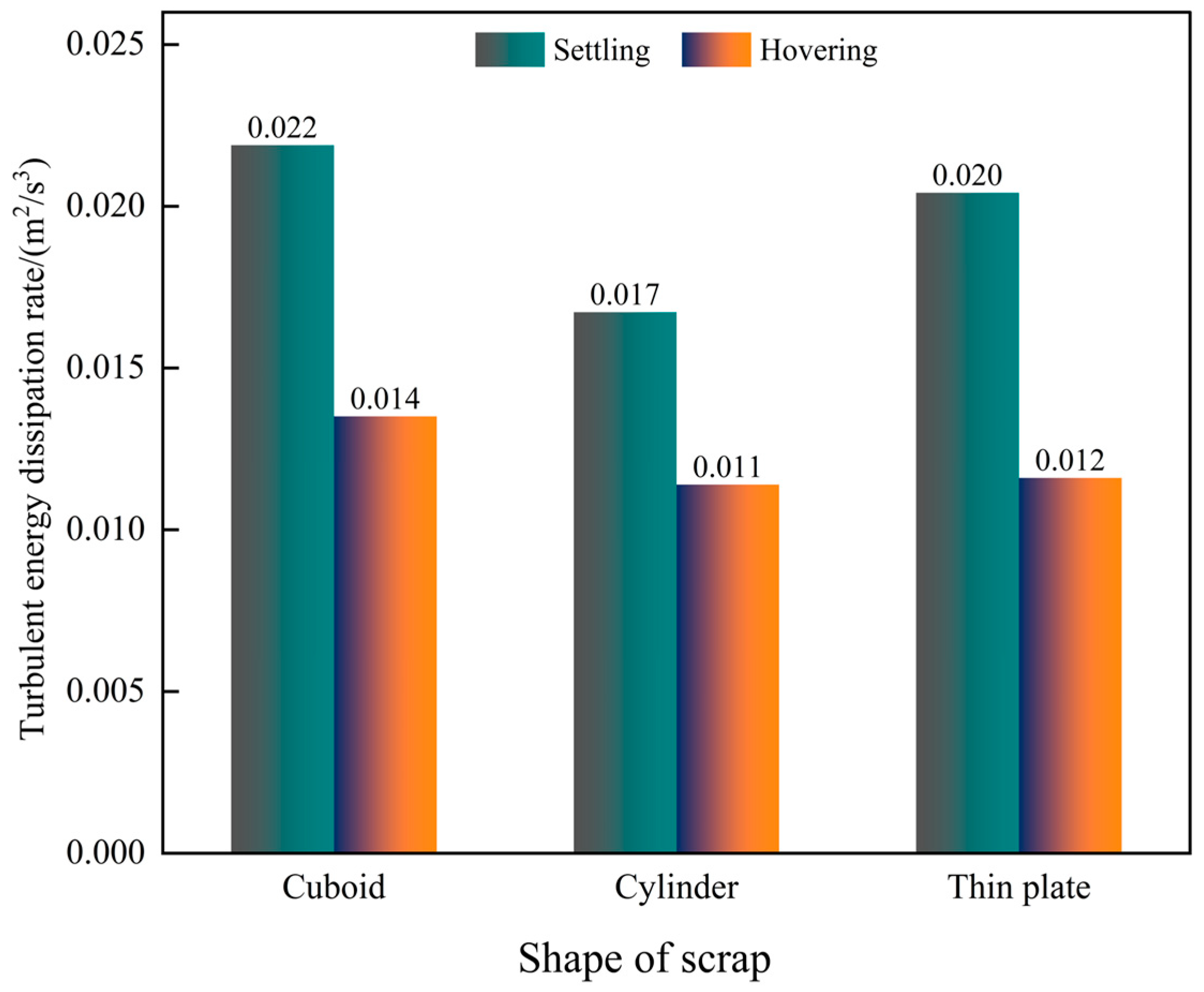

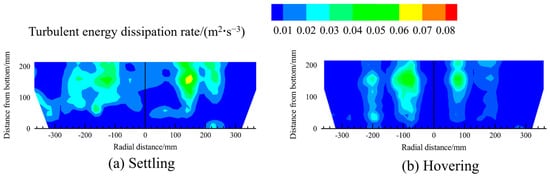

To quantitatively evaluate the influence of different scrap steel states on the average turbulent kinetic energy dissipation rate, the rate is calculated and statistically analysed under various scrap steel states, as shown in Figure 10. The data indicate that the variation trend of the average turbulent energy dissipation rate is inversely related to that of the melt pool mixing time. Moreover, when the scrap steel is rectangular and in a settling state, the average turbulent energy dissipation rate increases by 62% compared to that in the hovering state. For cylindrical and thin-plate scrap steel, the respective increases are 46.7% and 76%. Therefore, based on the above analysis, adding scrap steel with a density higher than that of molten steel can improve the dynamic conditions of the melt pool.

Figure 10.

The average turbulent energy dissipation rate of the melt pool for different scrap steel states.

3.2. Influence of Scrap Steel Distribution Pattern

3.2.1. Influence of Scrap Steel Distribution on Melt Pool Mixing Time

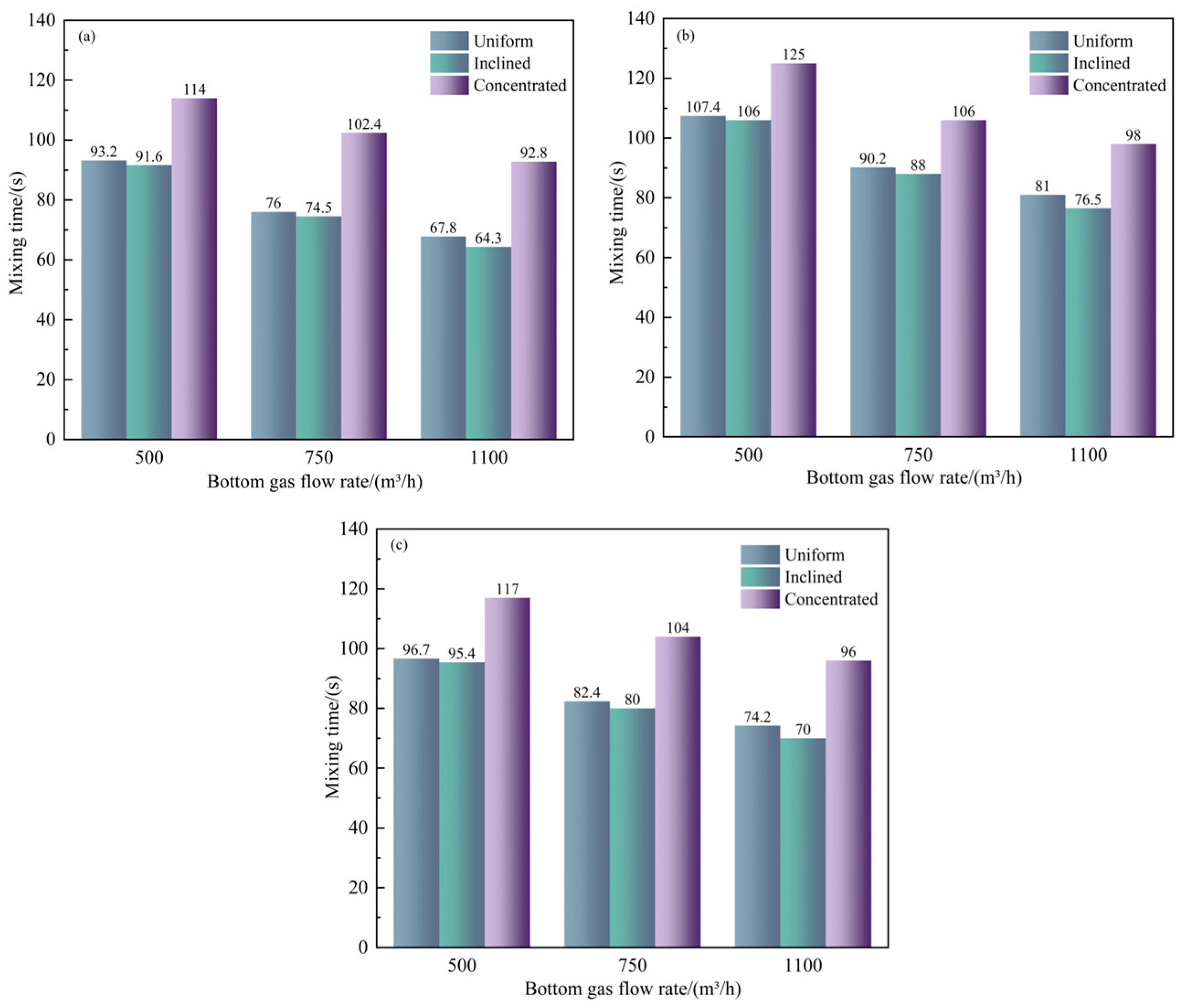

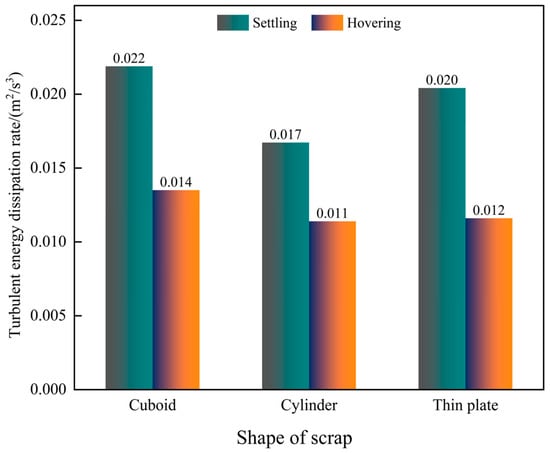

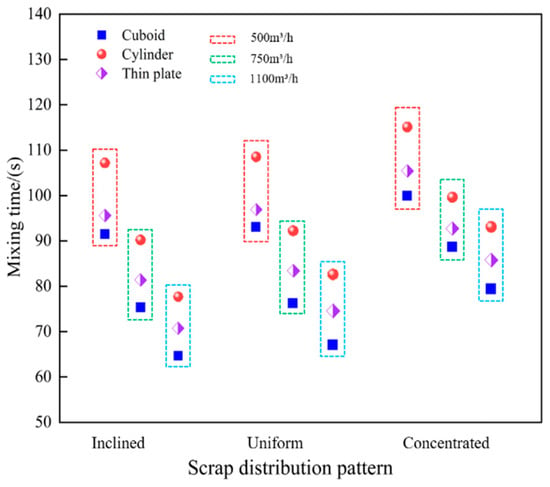

Figure 11 illustrates the relationship between melt pool mixing time, the scrap steel distribution pattern when the converter scrap ratio is 20% and the bottom-blowing gas flow rate.

Figure 11.

The relationship between melt pool mixing time and the scrap steel distribution pattern: (a) cuboid; (b) cylinder; (c) thin plate.

First, the figure indicates that the effectiveness of scrap steel distribution in reducing mixing time follows the following order: inclined > uniform > concentrated. However, the mixing times for inclined and uniform distributions are not substantially different. For instance, when the scrap steel is rectangular and the bottom-blowing gas flow rates are 500, 750 and 1100 m3/h, the differences in mixing time between the inclined and uniform distributions are only 1.6, 1.5 and 3.5 s, respectively. In contrast, under the centralised distribution, the mixing times are 114, 102.4 and 92.8 s, respectively. Compared to the uniform distribution, the inclined distribution reduces the mixing time by 1.7%, 2% and 5.2%, respectively. Meanwhile, compared to the centralised distribution, the inclined configuration reduces the mixing time by 19.6%, 27.2% and 30.7%, respectively. This is because when bottom-blowing gas enters the molten pool, an inclined distribution of scrap steel forms an asymmetric gas–liquid stirring zone between the scrap steel side and the non-scrap steel side, thereby enhancing horizontal flow and reducing the mixing time. In contrast, when the scrap steel is evenly distributed, the residence time of the injected gas is extended. This prolonged gas retention increases the stirring area, thereby reducing the mixing time. Meanwhile, when the scrap steel is concentrated in the converter melt pool, it obstructs the radial stirring of the bottom-blown gas, reducing mixing efficiency and increasing the mixing time.

Moreover, the figure confirms that the effect of scrap steel shape on mixing time follows the same order as before: cuboid > thin plate > cylinder. For example, at a bottom-blowing gas flow rate of 750 m3/h and under a settling or an inclined distribution, rectangular scrap steel reduces mixing time by 6.9% and 15.3%, respectively, compared to thin-plate and cylindrical steel.

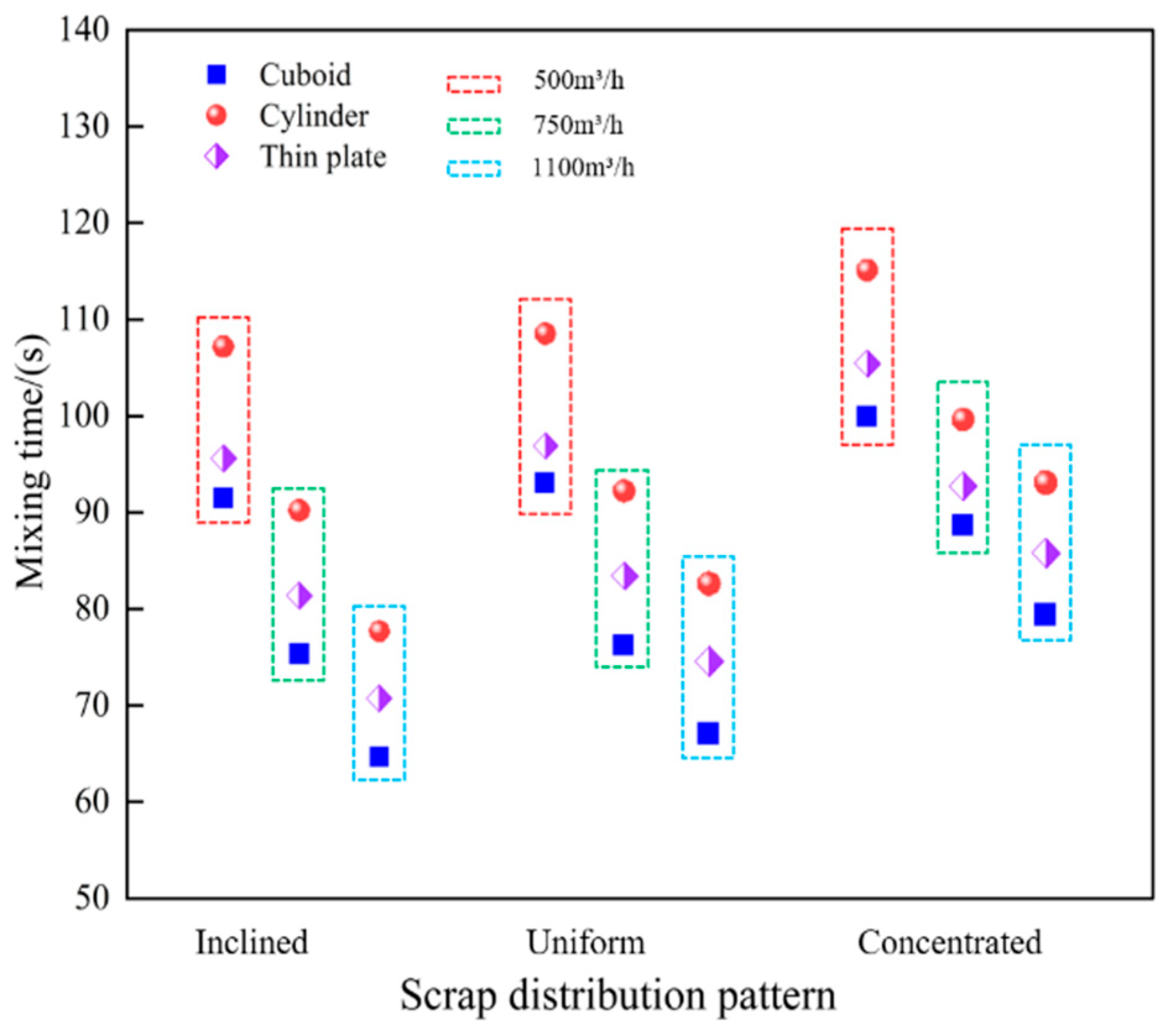

To better show how scrap shape and distribution affect mixing in the converter melt pool, their relationship with mixing time was established, as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

The relationship between melt pool mixing time and scrap shape and distribution pattern.

The figure shows that shaping the scrap as a rectangular prism and arranging it in an inclined or uniform distribution improves mixing. Considering the melting behaviour of scrap, an even distribution in the converter is more suitable.

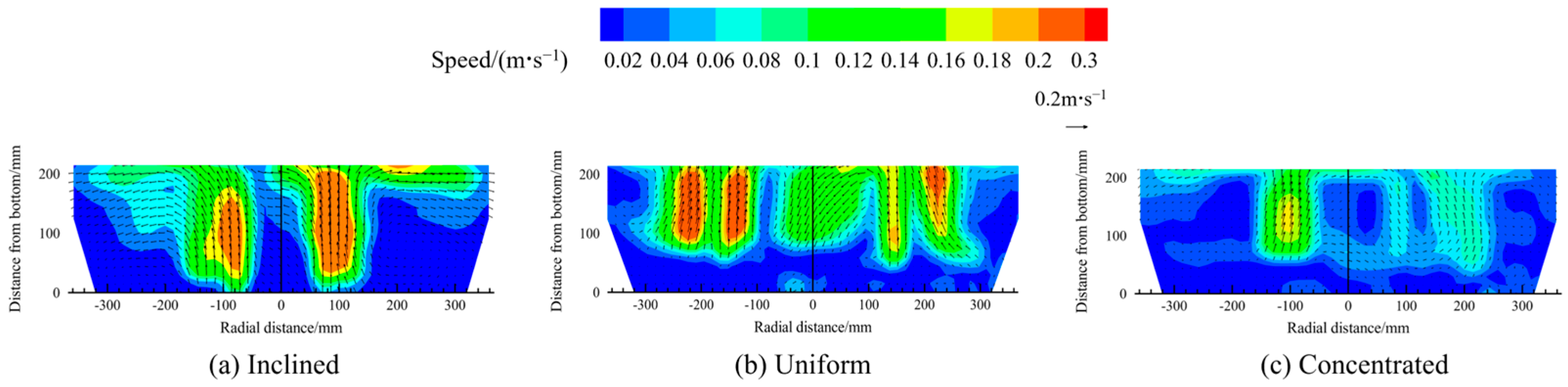

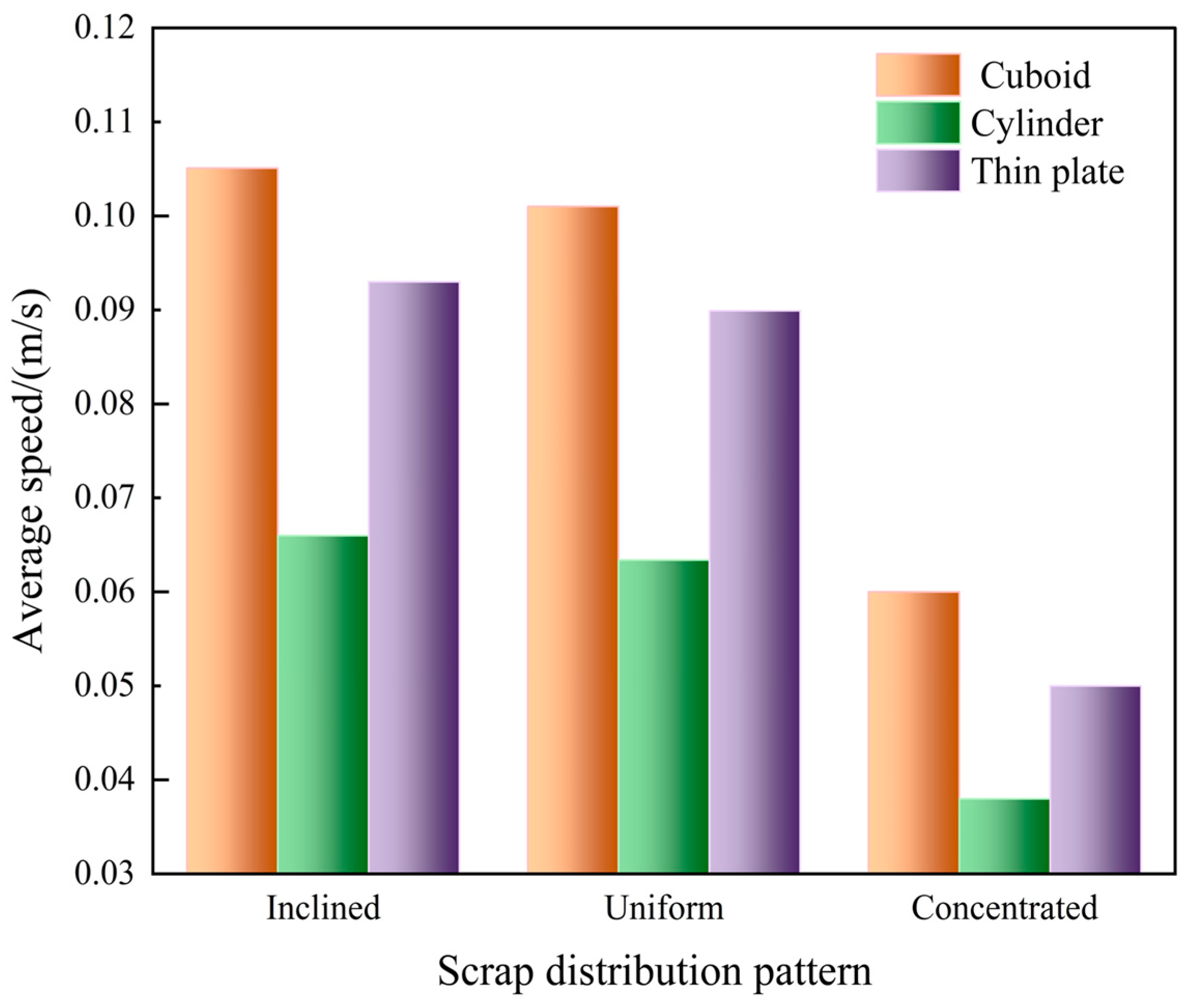

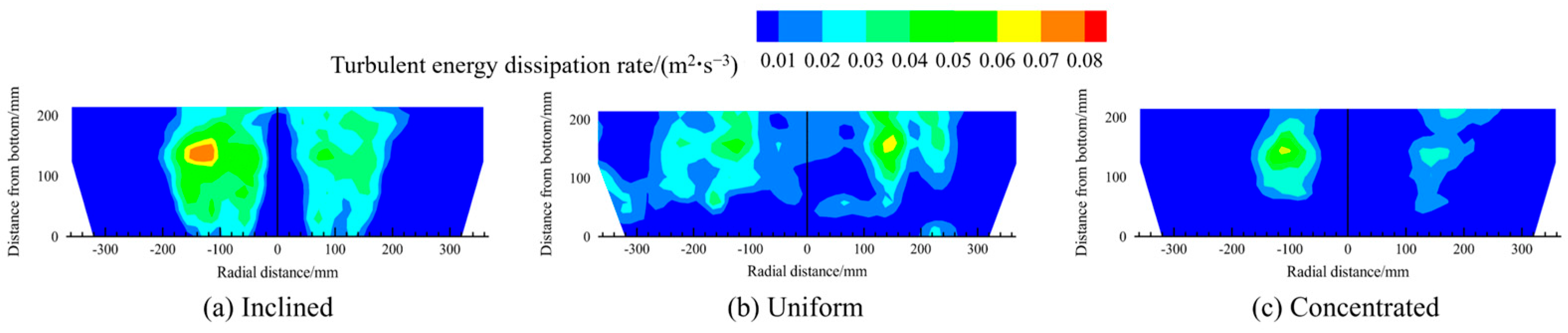

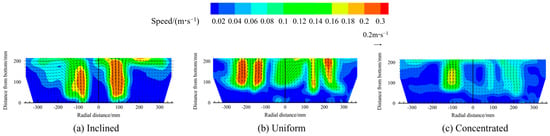

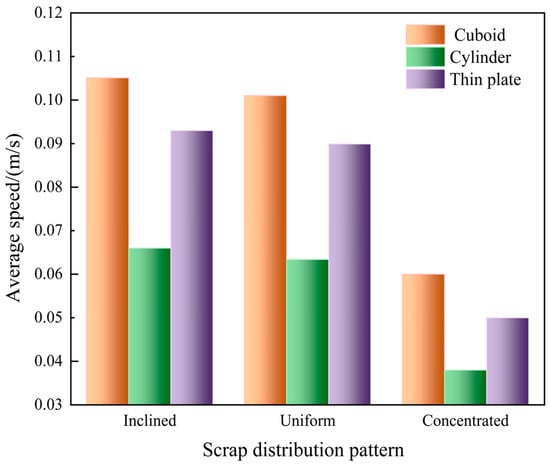

3.2.2. Influence of Scrap Steel Distribution on Melt Pool Velocity

Figure 13 illustrates the contour maps of the velocity distribution in the melt pool when scrap steel is distributed inclinedly, uniformly and concentratedly. The colour of the cloud map and the length of the arrows indicate the magnitude of the velocity. The figure shows that the melt pool velocity above the bottom-blowing nozzle is higher than that in other areas. When the scrap steel is distributed in an inclined manner, the velocity field of the gas blown into the melt pool exhibits a radial pattern. In contrast, under a uniform or concentrated distribution, the velocity field is primarily axial.

Figure 13.

The contour maps of the velocity distribution in the melt pool for different scrap steel distribution pattern.

To quantitatively assess the influence of scrap steel distribution on the average velocity in the melt pool, the average velocity under different scrap steel distribution patterns is calculated and statistically analysed, as shown in Figure 14. When the scrap steel is rectangular, the average velocity increases by 4% and 75.1%, respectively, under an inclined distribution compared to a uniform and a concentrated distribution. In contrast, when the scrap steel is cylindrical, the corresponding increases are 4.1% and 73.7%. Meanwhile, for thin-plate scrap, the respective values are 3.4% and 86%.

Figure 14.

The average velocity of the melt pool for different scrap steel distribution patterns.

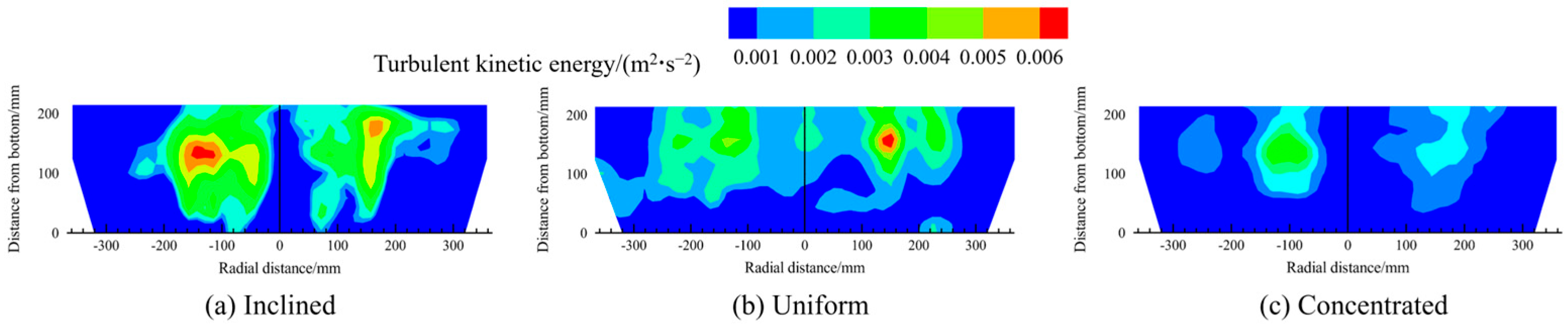

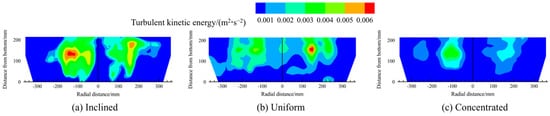

3.2.3. Influence of Scrap Steel Distribution on the Turbulent Characteristics of the Melt Pool

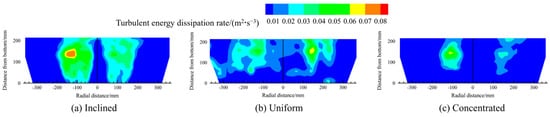

Figure 15 and Figure 16 illustrate the contour maps of the distribution of the turbulent kinetic energy and turbulent kinetic energy dissipation rate in the melt pool under different scrap steel distribution patterns. The distribution of turbulent kinetic energy and the energy dissipation rate in the melt pool is consistent with the velocity distribution. Both values are higher above the bottom-blowing nozzle than in other regions.

Figure 15.

The contour maps of the distribution of the turbulent kinetic energy in the melt pool for different scrap steel distribution patterns.

Figure 16.

The contour maps of the distribution of the turbulent energy dissipation rate in the melt pool for different scrap steel distribution patterns.

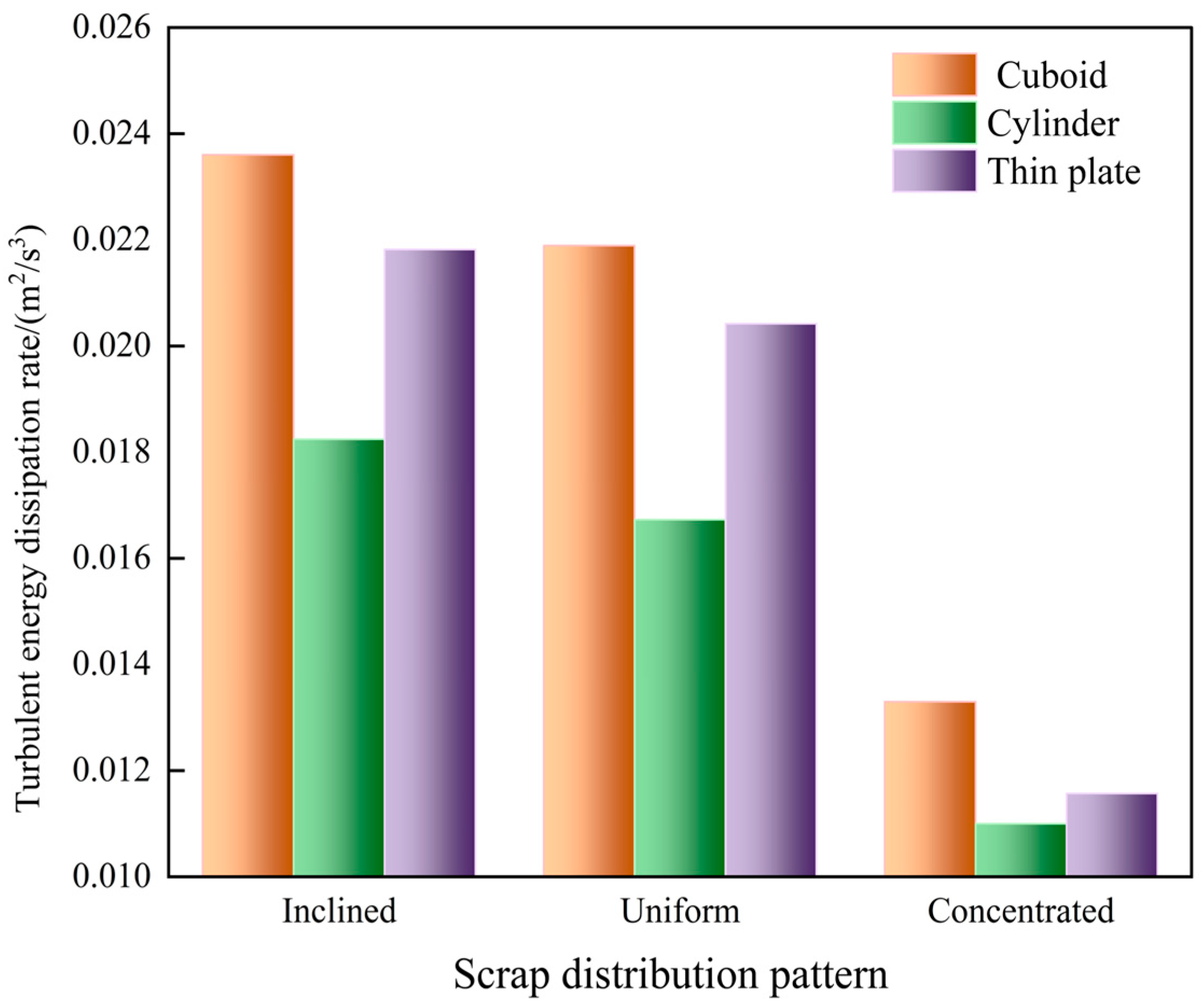

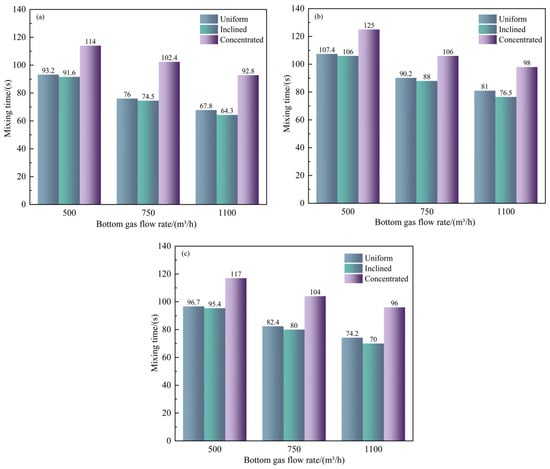

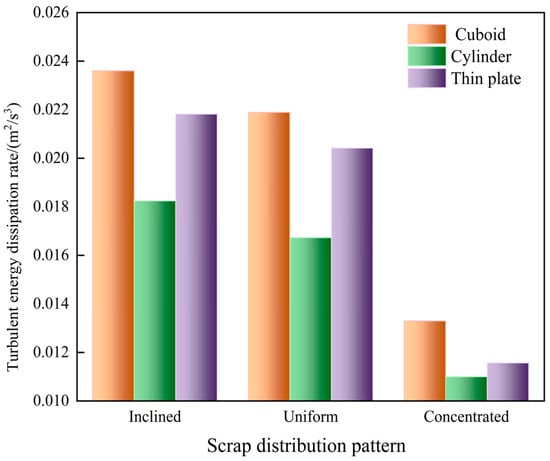

To quantitatively assess the influence of scrap steel distribution on the average turbulent kinetic energy dissipation rate, the rates under different scrap steel distribution patterns were calculated and statistically analysed, as shown in Figure 17.

Figure 17.

The average turbulent energy dissipation rates of the melt pool for different scrap steel distribution patterns.

The figure indicates that when the scrap steel shape is rectangular, the average dissipation rate increases by 7.8% and 77.4%, respectively, under an inclined distribution compared to a uniform and a central distribution. Meanwhile, when the scrap steel is cylindrical, the corresponding values are 9.1% and 65.9%. For thin-plate scrap, the respective increases are 6.9% and 88.6%. In line with the melting process of scrap steel, a uniform distribution in the converter is more suitable.

3.3. Influence of Scrap Steel Material Type

3.3.1. Influence of Scrap Steel Material Type on the Mixing Time of the Melt Pool

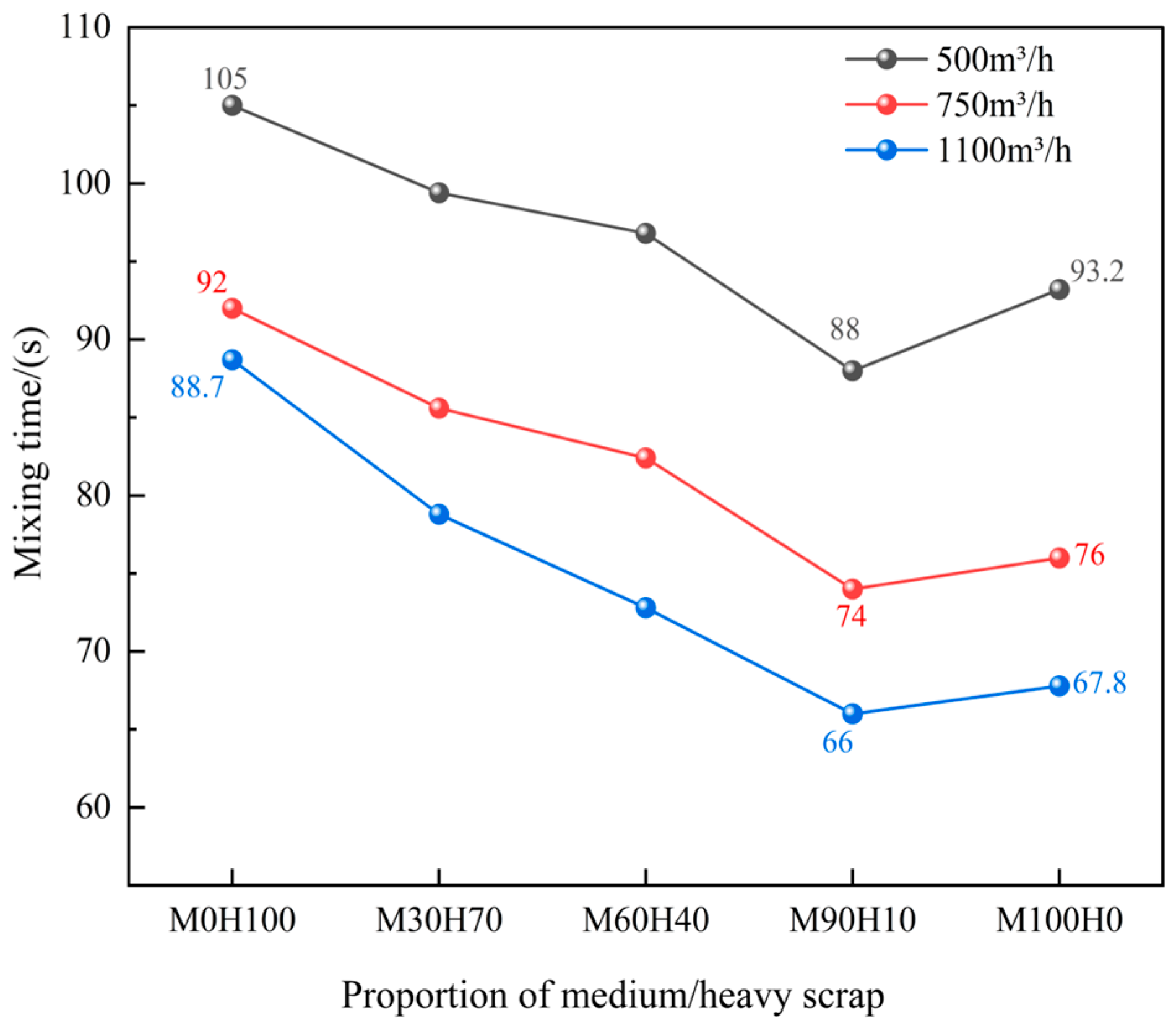

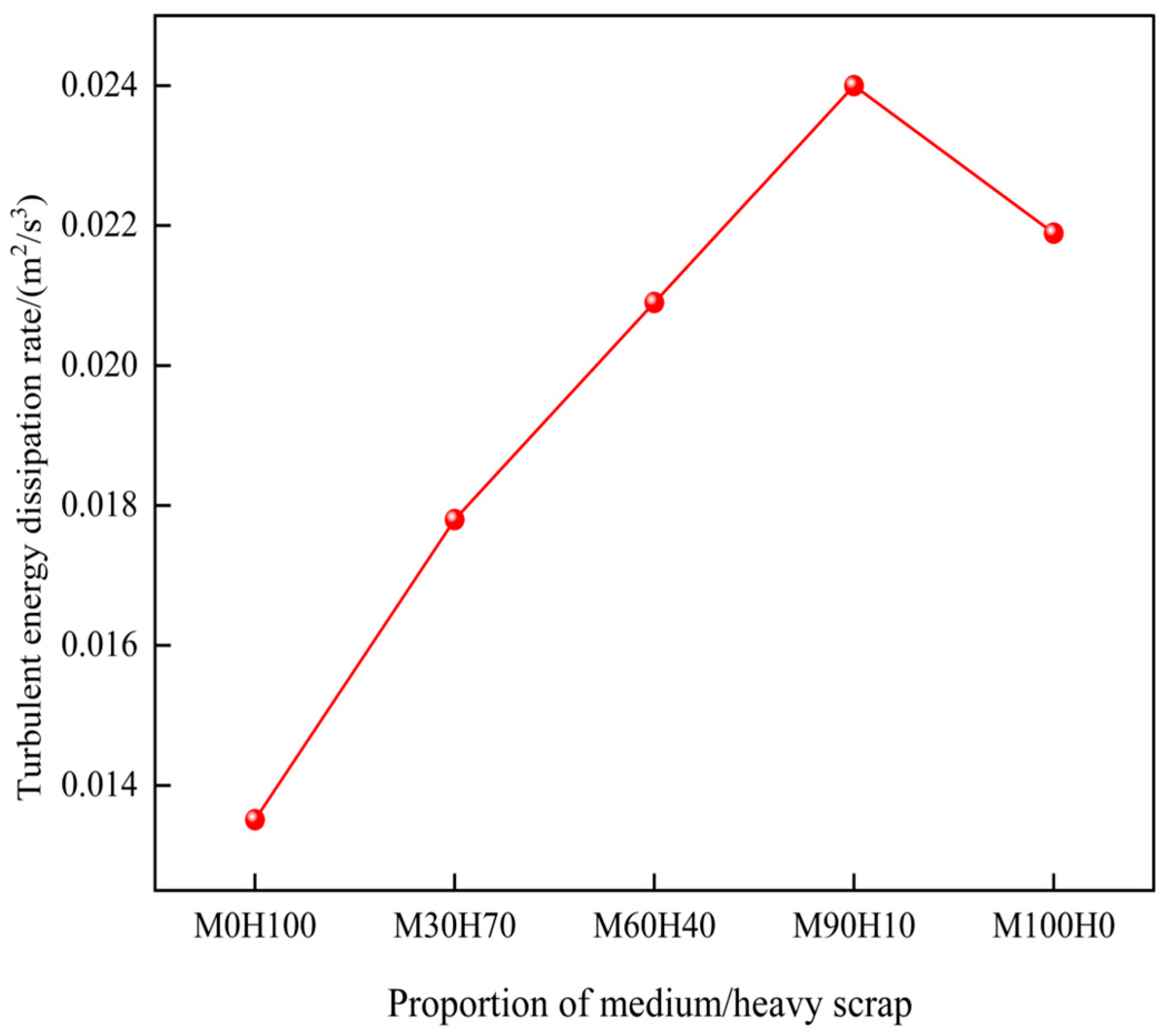

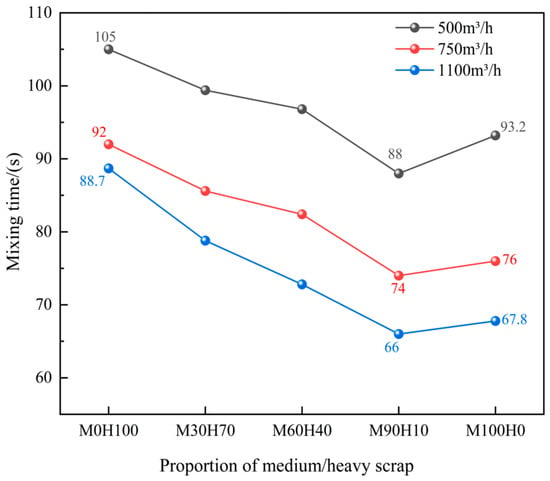

Figure 18 illustrates the relationship between the proportion of medium and heavy scrap steel and the mixing time of the converter melt when the scrap steel ratio is 20% and the scrap is rectangular in shape. The graph shows that as the proportion of medium scrap increases, the mixing time first decreases and then increases. This trend occurs because the medium scrap settles within the converter, and when present in an appropriate proportion, it extends the stirring path of the gas blown into the melt pool. Additionally, both settling and hovering scrap are present in the converter. When the two collide, the settling scrap breaks the bottom-blown gas into smaller bubbles. As these bubbles rise to the surface under buoyancy and collide with the hovering scrap, gas escape from the steel surface is suppressed. This increases bubble residence time, enhances the stirring effect and reduces the mixing time of the melt pool.

Figure 18.

The relationship between melt pool mixing time and the proportion of medium and heavy scrap steel.

When the scrap ratio in the 300-ton converter is 20%, adding 90% medium scrap and 10% heavy scrap results in the shortest mixing time. At bottom-blowing flow rates of 500, 750 and 1100 m3/h, the corresponding mixing times are 88, 74 and 66 s, respectively. Under this structure, the mixing times are reduced by 17, 18 and 22.7 s, representing reductions of 16.2%, 19.6% and 25.6%, respectively, compared to when only heavy scrap is used. Meanwhile, the mixing times are reduced by 5.2, 2.0 and 1.8 s, representing reductions of 5.6%, 2.6% and 2.7%, respectively, compared to when only medium scrap is used.

Moreover, the graph indicates that as the bottom-blowing gas flow rate increases, the mixing time of the converter melt pool decreases; however, the extent of this reduction diminishes progressively. For example, under operating condition M0H100—corresponding to 0% medium scrap and 100% heavy scrap—the bottom-blowing gas flow rate increases from 500 m3/h to 750 m3/h, while the mixing time of the melt pool decreases from 105 s to 92 s. For every 100 m3/h increase in the bottom-blowing gas flow rate, the mixing time decreases by 5.0%. When the bottom-blowing gas flow rate increases from 750 m3/h to 1100 m3/h, the mixing time further decreases from 92 s to 88.7 s. In this case, each 100 m3/h increase results in only a 1.0% reduction in mixing time. Table 7 presents the decreases in mixing time for different proportions of medium and heavy scrap steel per 100 m3/h increase in bottom-blowing gas flow rate. According to the table, the greatest reduction in mixing time is observed under operating condition M90H10, where the proportion of medium scrap is 90% and heavy scrap is 10%.

Table 7.

The decrease in mixing time based on the proportion of medium and heavy scrap steel.

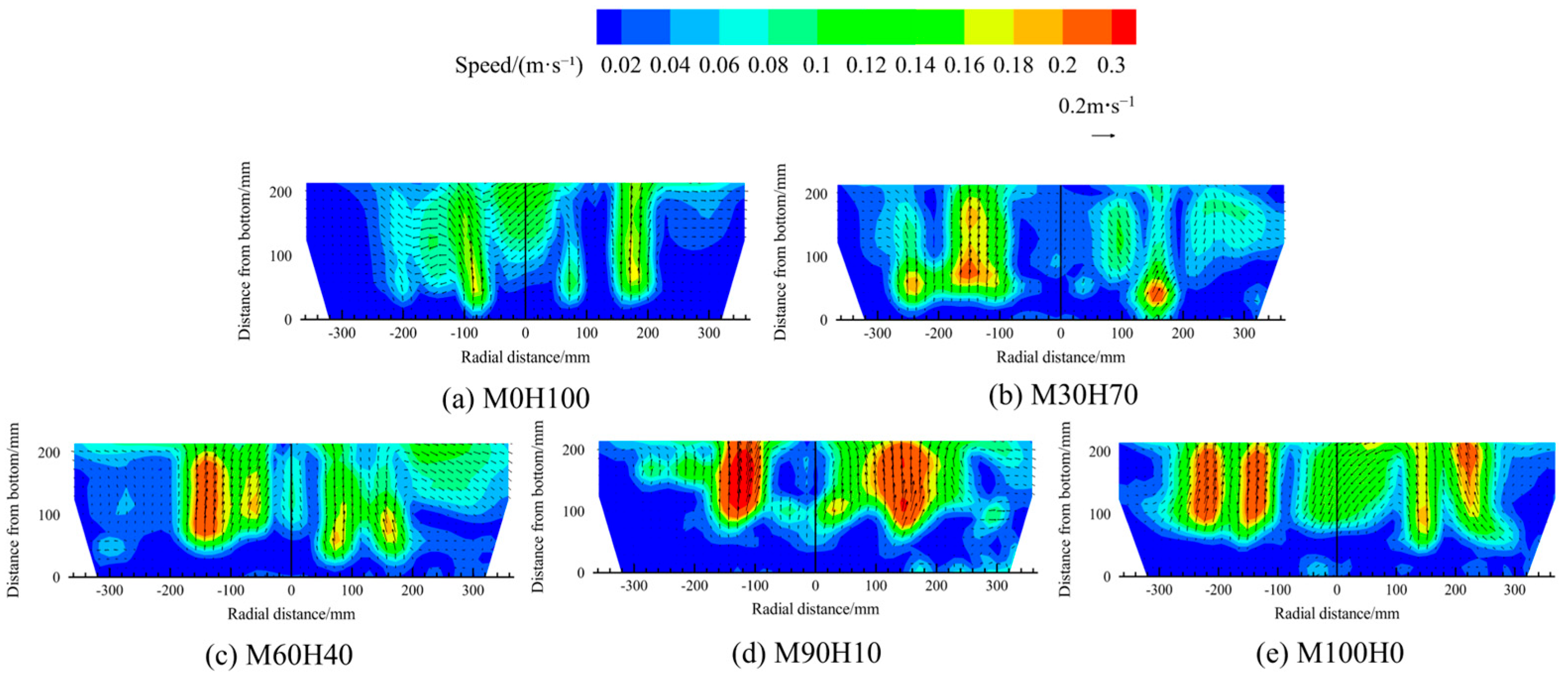

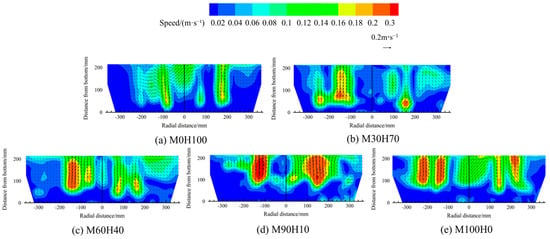

3.3.2. Influence of Scrap Steel Material Type on Melt Pool Velocity

Figure 19 presents the contour maps of the velocity distribution in the melt pool for different medium-to-heavy scrap ratios at a constant converter scrap ratio of 20%. The colour gradient and arrow length in the cloud map represent the magnitude of the velocity field. First, the figure indicates that the velocity of the melt pool above the bottom-blowing nozzle is higher than that in other regions. Second, as the proportion of medium scrap increases, the initial point of molten steel stirring gradually shifts upwards from a location near the bottom-blowing nozzle.

Figure 19.

The contour maps of the velocity distribution in the melt pool for different medium-to-heavy scrap ratios.

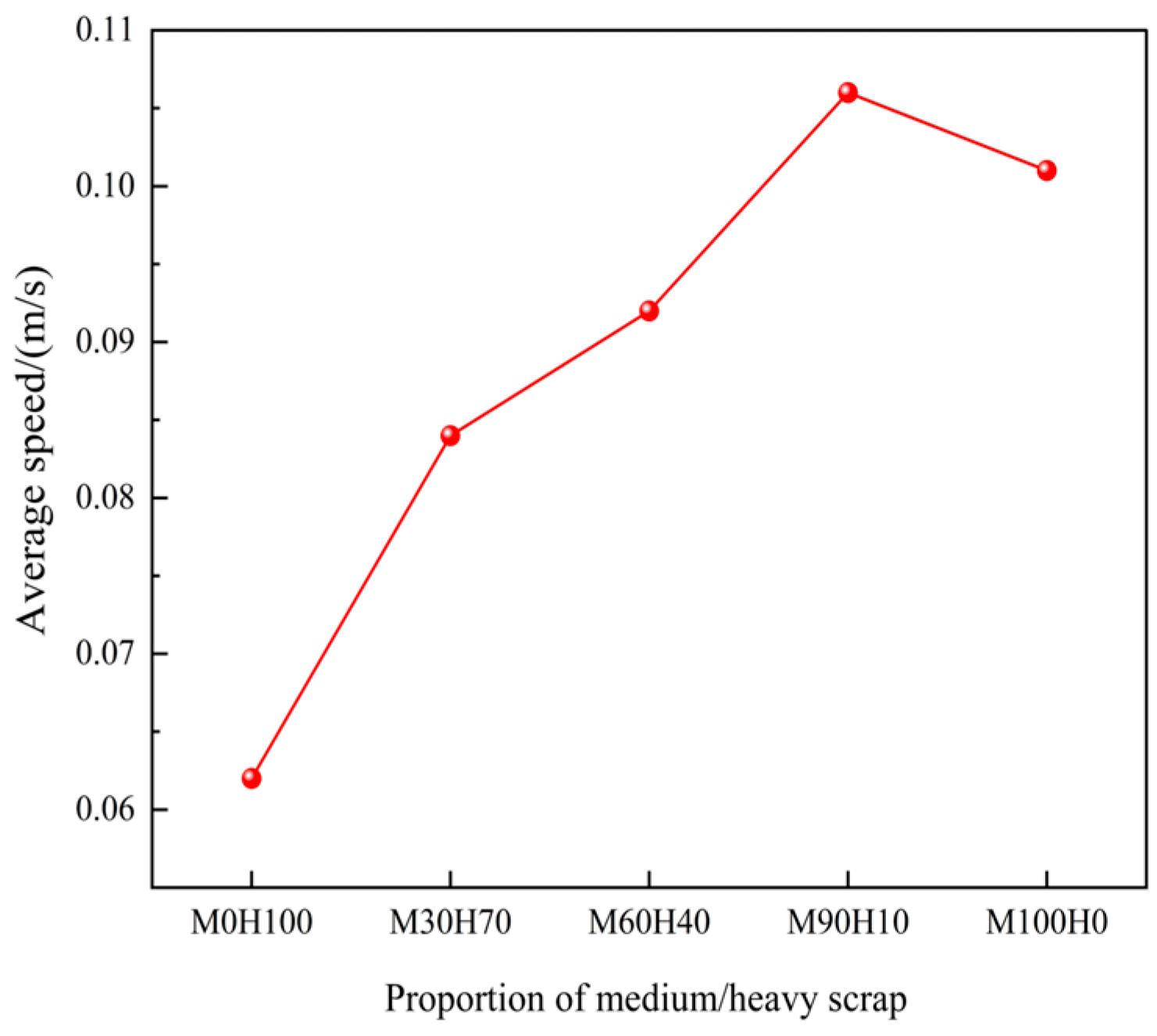

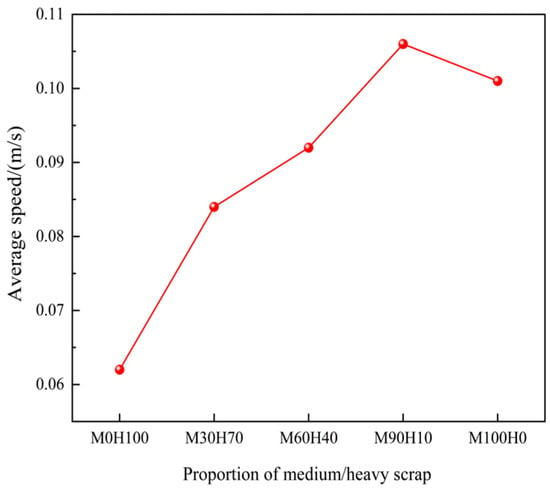

To quantitatively assess the effect of scrap steel material type on average velocity in the melt pool, the average velocity under various medium-to-heavy scrap ratios is calculated and statistically analysed, as illustrated in Figure 20. The graph indicates that the highest average melt pool velocity—0.106 m/s—is observed when the proportion of medium scrap is 90% and that of heavy scrap is 10% (the optimal condition). Compared with this optimal condition, the average melt pool velocity increases by 71% with 100% heavy scrap and by 5% with 100% medium scrap.

Figure 20.

The average velocity of the melt pool for different medium-to-heavy scrap ratios.

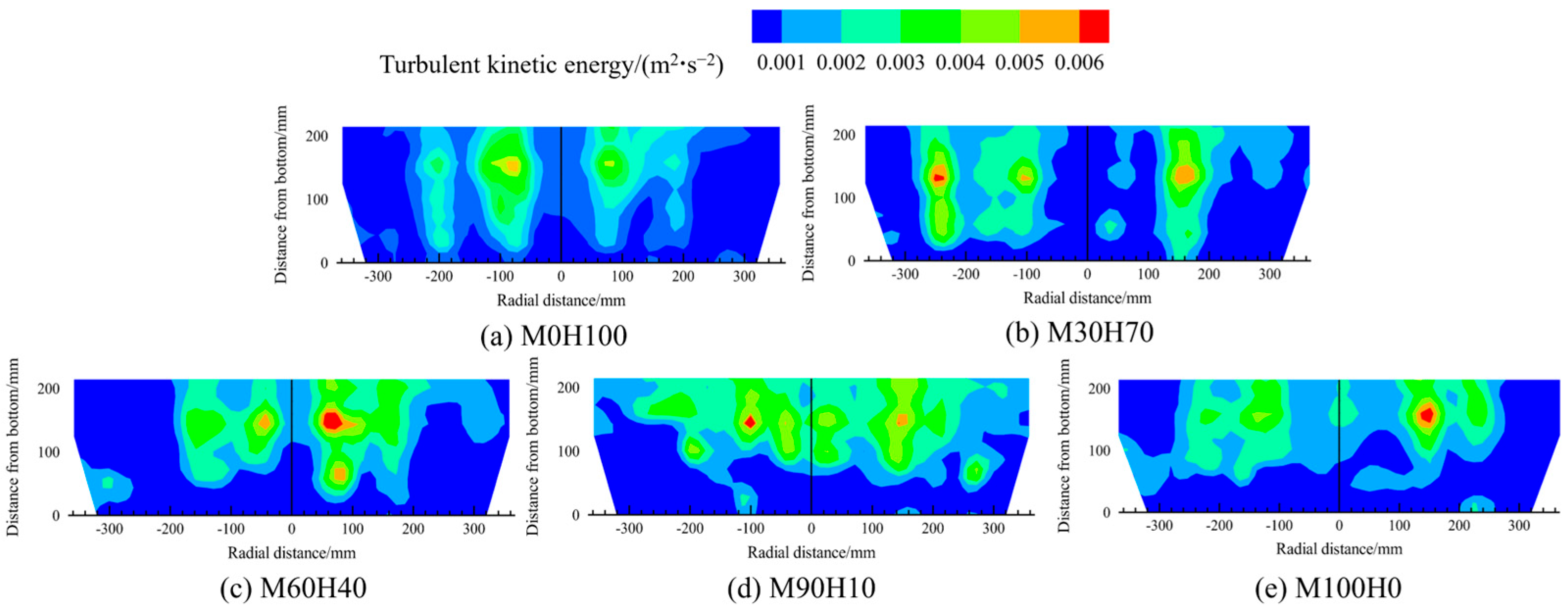

3.3.3. Influence of Scrap Steel Material Type on the Turbulent Characteristics of the Melt Pool

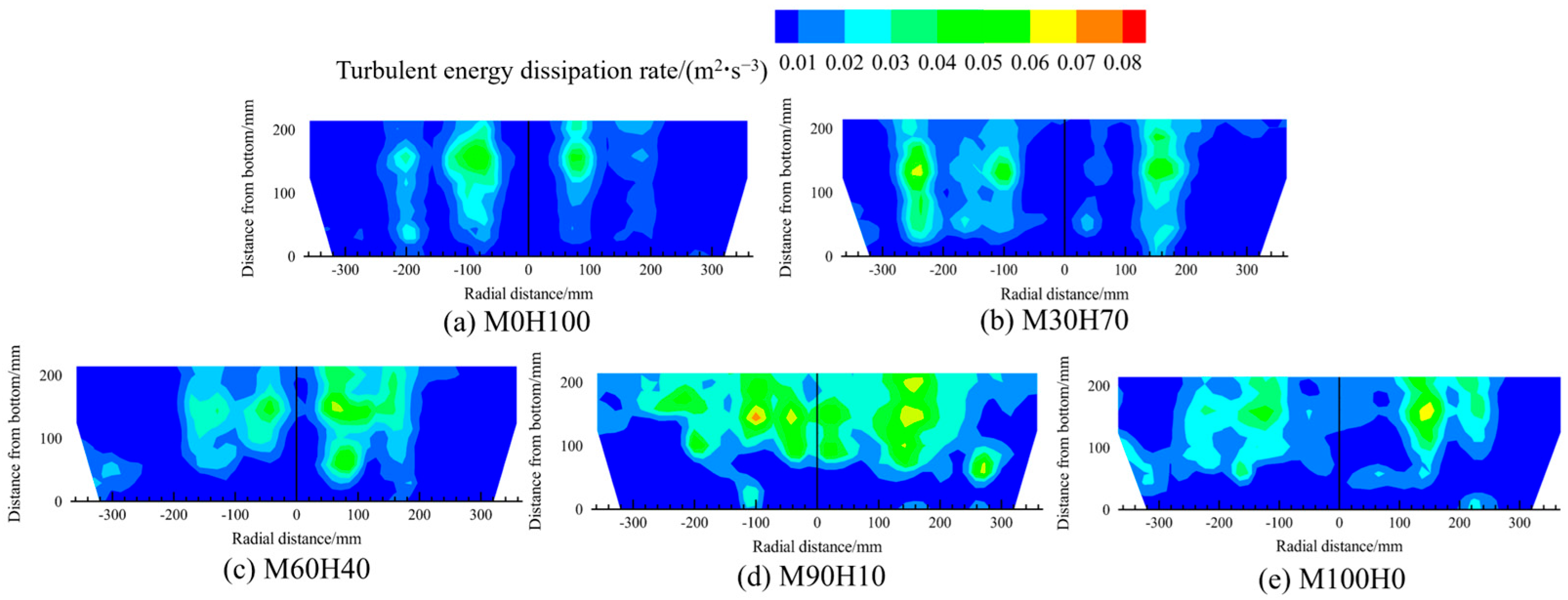

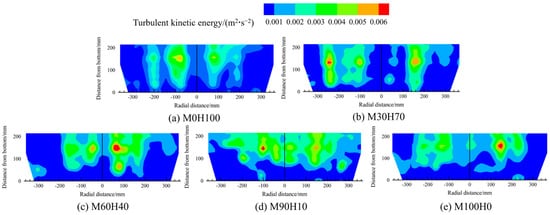

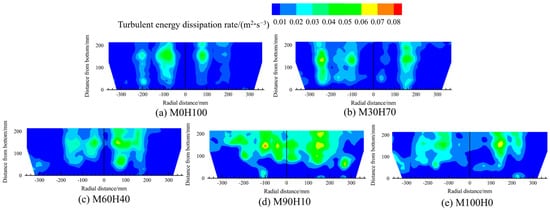

Figure 21 and Figure 22 present the contour maps of the distribution of the turbulent kinetic energy and the turbulent energy dissipation rate in the melt pools containing various medium-to-heavy scrap ratios under a constant converter scrap ratio of 20%. The distribution patterns of both parameters are consistent with the melt pool velocity distribution: compared with other regions, the turbulent kinetic energy and dissipation rate are higher above the bottom-blowing nozzle.

Figure 21.

The contour maps of the distribution of the turbulent kinetic energy in the melt pool for different medium-to-heavy scrap ratios.

Figure 22.

The contour maps of the distribution of the turbulent energy dissipation rate in the melt pool for different medium-to-heavy scrap ratios.

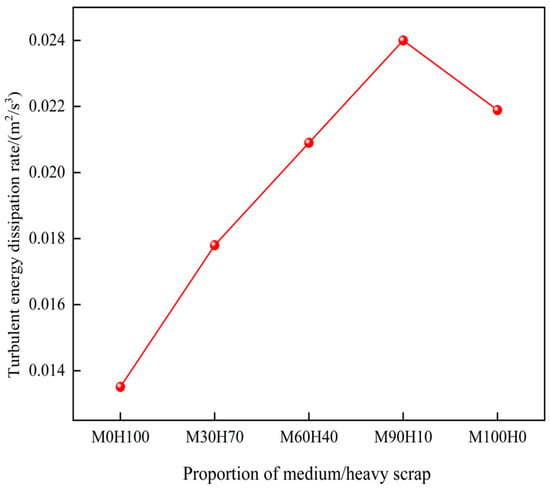

To quantitatively evaluate the effect of scrap steel material type on the average turbulent dissipation rate of the melt pool, rates under different medium-to-heavy scrap ratios are calculated and statistically analysed, as illustrated in Figure 23. The highest average turbulent dissipation rate is observed when 90% medium scrap and 10% heavy scrap are used. This rate is 77.6% higher than that with 100% heavy scrap and 9.6% higher than that with 100% medium scrap. Therefore, applying a 9:1 medium-to-heavy scrap ratio results in improved dynamic conditions within the converter melt pool.

Figure 23.

The average turbulent energy dissipation rate of the melt pool for different medium-to-heavy scrap ratios.

3.4. Impact of Scrap Steel Types

3.4.1. Influence of Scrap Steel Types on Melt Pool Mixing Time

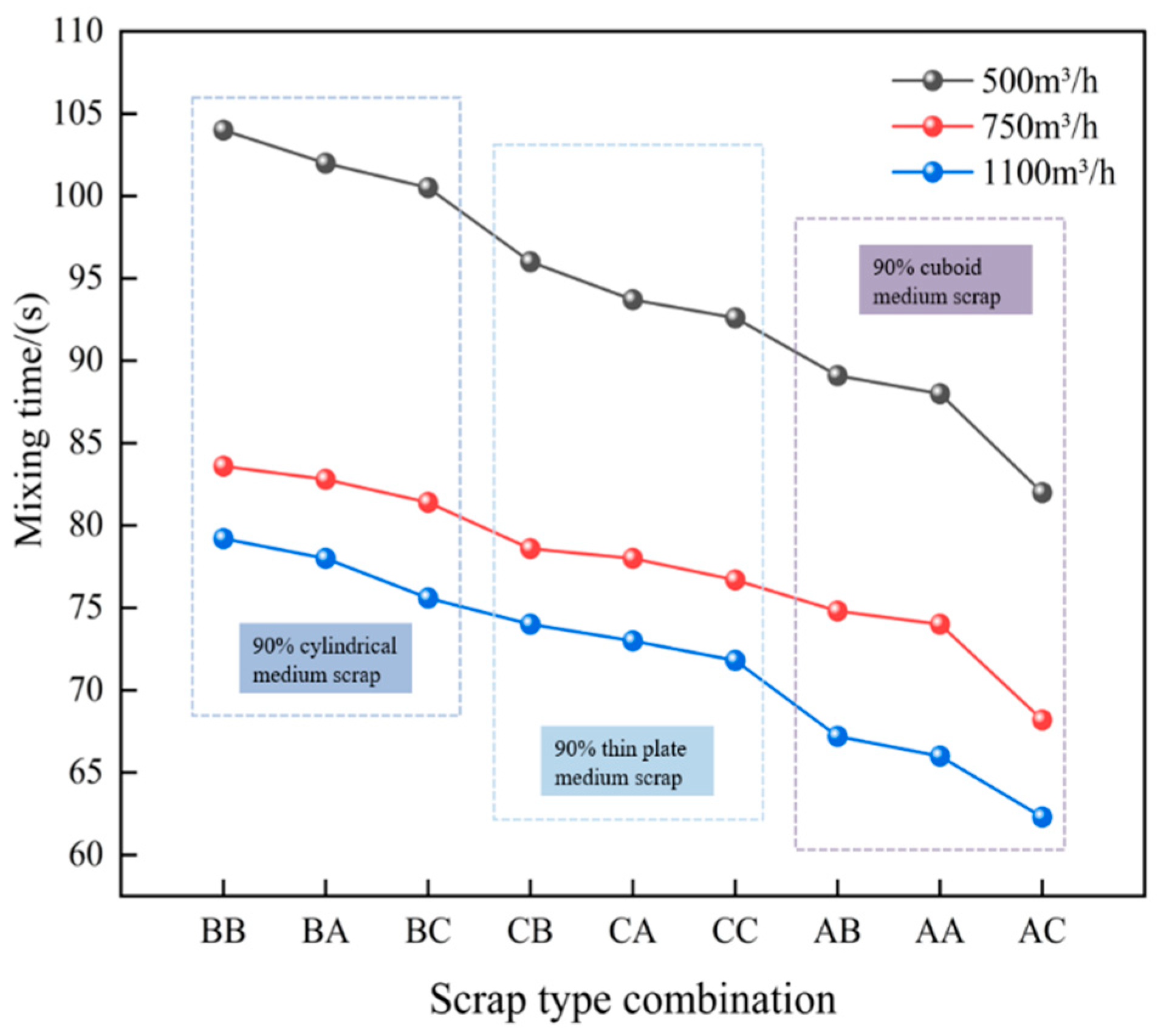

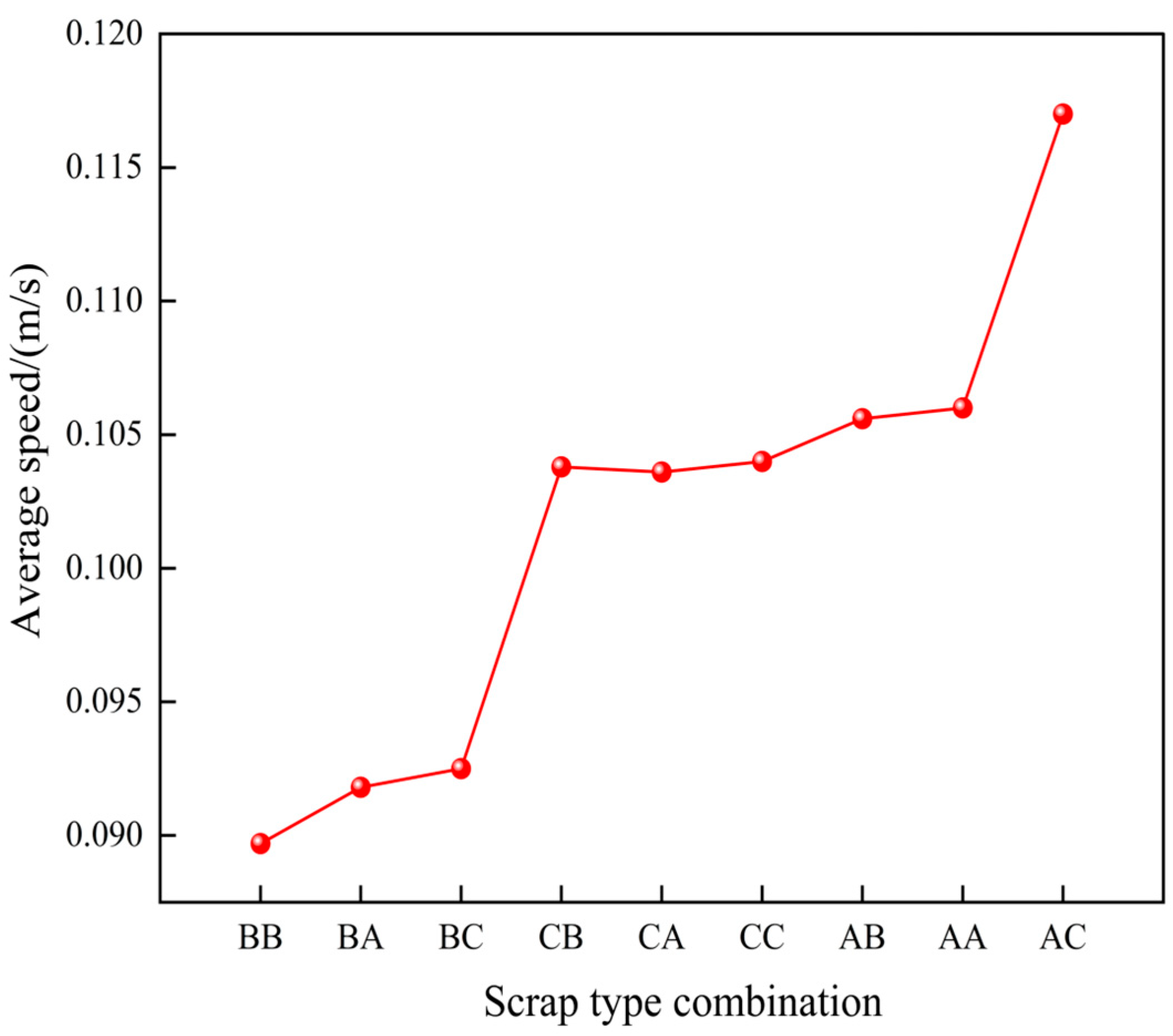

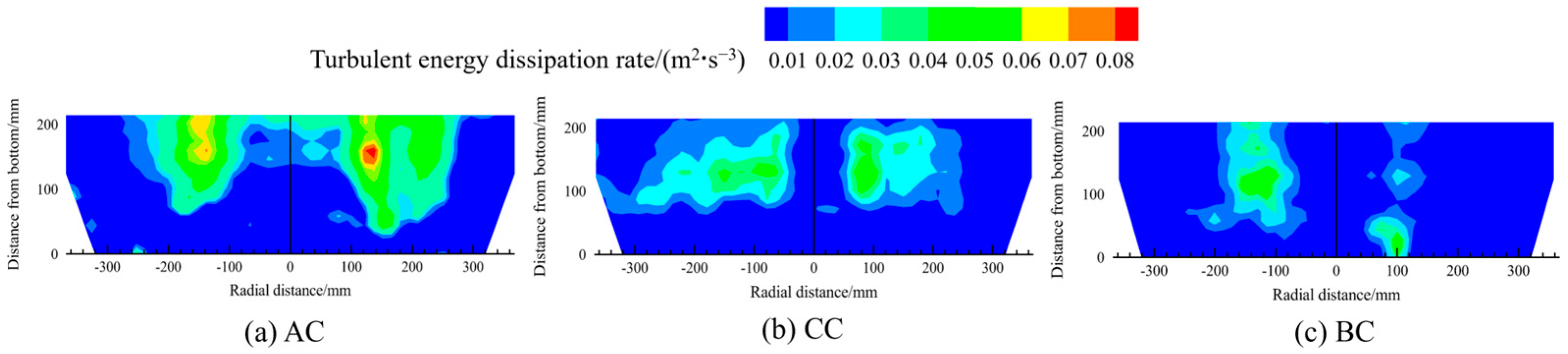

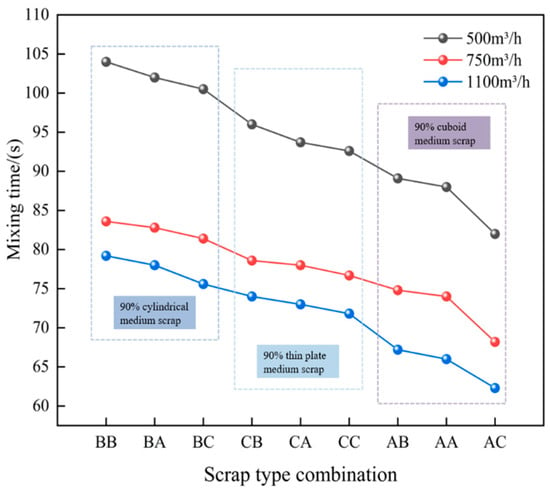

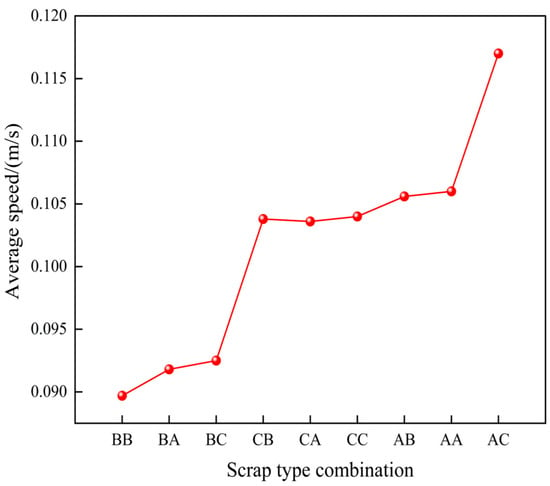

Based on the above analysis, the shortest melt pool mixing time is observed at a converter scrap ratio of 20% and a medium-to-heavy scrap ratio of 9:1. To simplify on-site loading while accounting for shape variations, only two scrap steel shapes are charged in the melt pool as a hypothetical premise. The influence of scrap steel type on converter melt pool mixing time is then investigated, as illustrated in Figure 24. For convenience in discussing the results, A, B and C denote rectangular, cylindrical and thin-plate shapes, respectively.

Figure 24.

The relationship between melt pool mixing time and scrap steel types.

Figure 24 indicates that, at a converter scrap ratio of 20%, the melt pool mixing effect is most pronounced when 90% of the scrap is rectangular, followed by thin-plate shapes. The weakest mixing is observed when 90% of the scrap is cylindrical, consistent with earlier observations. The best mixing performance is achieved with scrap type AC, comprising 90% rectangular medium scrap and 10% thin-plate heavy scrap. At bottom-blowing flow rates of 500, 750 and 1100 m3/h, the corresponding mixing times are 82, 68.2 and 62.3 s, respectively. Compared with scrap type CC (90% medium scrap in thin-plate form and 10% heavy scrap in thin-plate form), scrap type AC reduces the mixing time by 11.4%, 11.1% and 13.2%, respectively. Similarly, relative to scrap type BC (90% medium scrap in cylindrical form and 10% heavy scrap in thin-plate form), scrap type AC reduces the mixing time by 18.4%, 16.2% and 17.6%, respectively. This improvement is attributed to the rectangular scrap, which disperses the bottom-blown gas into smaller bubbles. Furthermore, the large specific surface area of the thin-plate scrap enhances bubble retention by impeding their escape from the molten steel. This increases the residence time of bubbles in the melt pool, intensifies stirring and thereby reduces the mixing time.

In summary, at a converter scrap ratio of 20%—with 90% medium scrap and 10% heavy scrap—the recommended scrap combinations for achieving effective melt pool mixing, in order of performance, are as follows: rectangular medium scrap with thin-plate heavy scrap, rectangular medium scrap with additional rectangular medium scrap and rectangular medium scrap with cylindrical heavy scrap.

Furthermore, the graph indicates that as the bottom-blowing gas flow rate increases, the mixing time of the converter melt pool decreases; however, the rate of this reduction also diminishes. For example, under condition BB—comprising 90% medium scrap in cylindrical form and 10% heavy scrap in cylindrical form—the bottom-blowing gas flow rate increases from 500 m3/h to 750 m3/h, while the melt pool mixing time decreases from 104 s to 83.6 s. For every 100 m3/h increase in the bottom-blowing gas flow rate, the mixing time decreases by 7.8%. When the bottom-blowing gas flow rate increases from 750 m3/h to 1100 m3/h, the mixing time further decreases from 83.6 s to 79.2 s. In this interval, each 100 m3/h increase in the bottom-blowing gas flow rate results in only a 1.5% reduction in mixing time. For other scrap types, Table 8 presents the decreases in the converter melt pool mixing time for the different scrap steel types at various bottom-blowing gas flow rates per 100 m3/h increment.

Table 8.

The decreases in mixing time for the different scrap steel types.

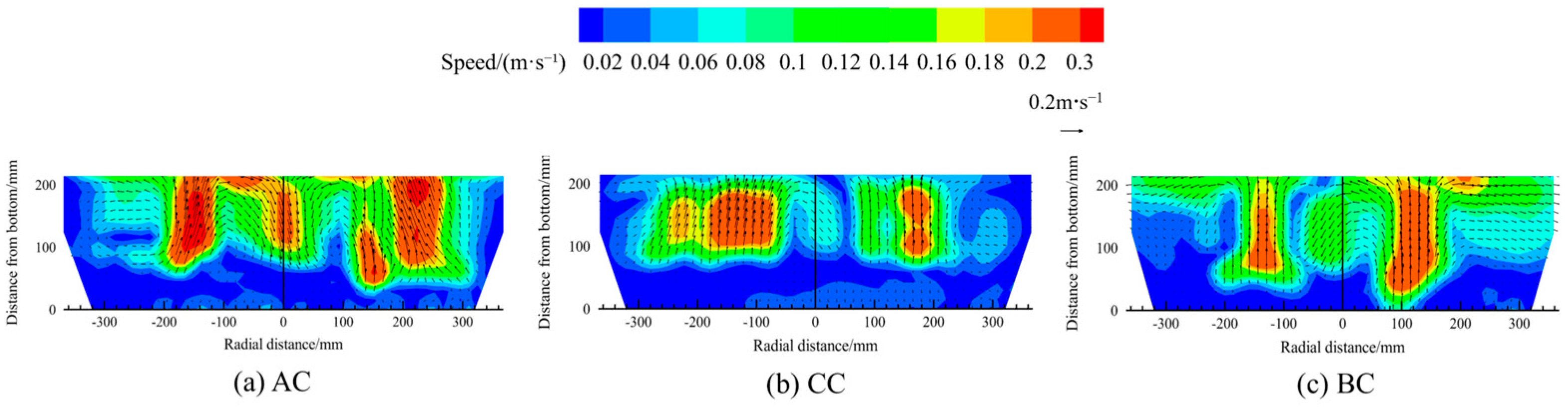

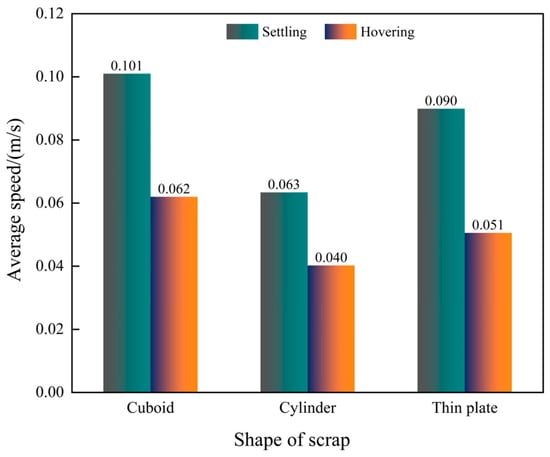

3.4.2. Influence of Scrap Steel Type on Melt Pool Velocity Distribution

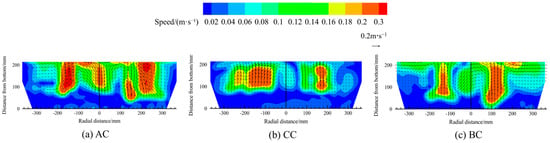

Figure 25 presents the contour maps of the velocity distribution in the melt pool for different scrap steel types based on a fixed 9:1 medium-to-heavy scrap ratio. The colour gradient and arrow length in the cloud map represent velocity magnitude.

Figure 25.

The contour maps of the velocity distribution in the melt pool for different scrap steel types.

The figure indicates that, compared to other regions, melt pool velocity is highest above the bottom-blowing nozzle. When 90% of the scrap is rectangular, the melt pool velocity reaches its maximum. When 90% of the scrap is in thin-plate form, the gas-stirring zone initiates farthest from the bottom-blowing nozzle. In contrast, with 90% cylindrical scrap, the gas stirring zone initiates nearest to the bottom-blowing nozzle.

To quantitatively assess the influence of scrap steel type on average velocity in the melt pool, velocities under different scrap steel types are calculated and statistically analysed, as shown in Figure 26. When 90% of the scrap is rectangular, the average melt pool velocity is highest, followed by that for thin-plate and cylindrical forms. For scrap type AC, the average melt pool velocity increases by 12.5% and 26.5% relative to types CC and BC, respectively.

Figure 26.

The average velocity of the melt pool for different scrap steel types.

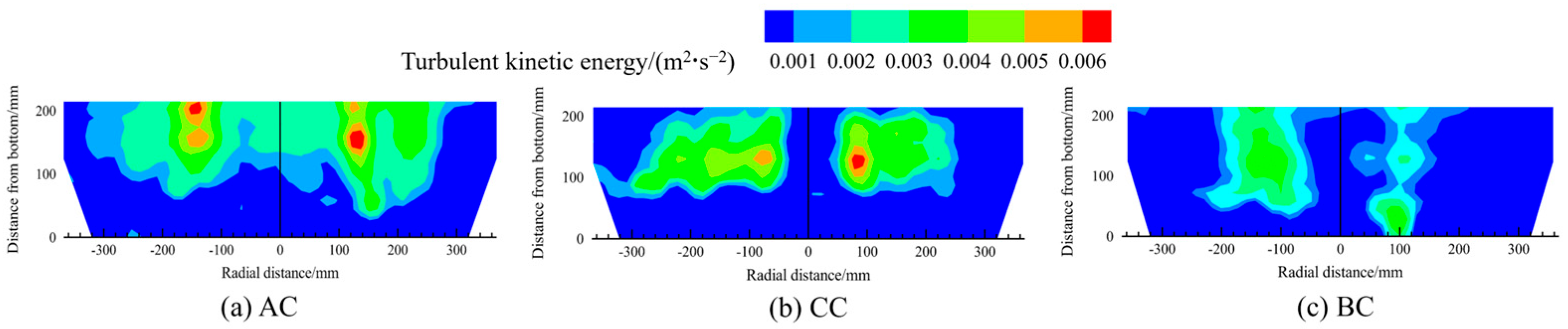

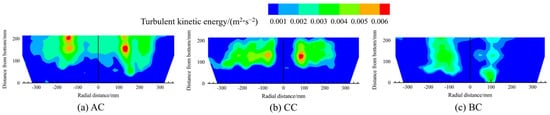

3.4.3. Influence of Scrap Steel Type on Melt Pool Turbulent Characteristics

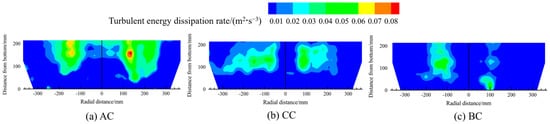

Figure 27 and Figure 28 present the contour maps of the distribution of the turbulent kinetic energy and the turbulent energy dissipation rate in the melt pool, based on a fixed 9:1 medium-to-heavy scrap ratio across different scrap steel types. The distribution patterns of turbulent kinetic energy and dissipation rate mirror that of melt pool velocity: compared to other regions, both quantities are higher above the bottom-blowing nozzle. The graph also indicates that, for scrap type AC, the turbulent kinetic energy and dissipation rate are relatively high.

Figure 27.

The contour maps of the distribution of the turbulent kinetic energy in the melt pool for different scrap steel types.

Figure 28.

The contour maps of the distribution of the turbulent energy dissipation rate in the melt pool for different scrap steel types.

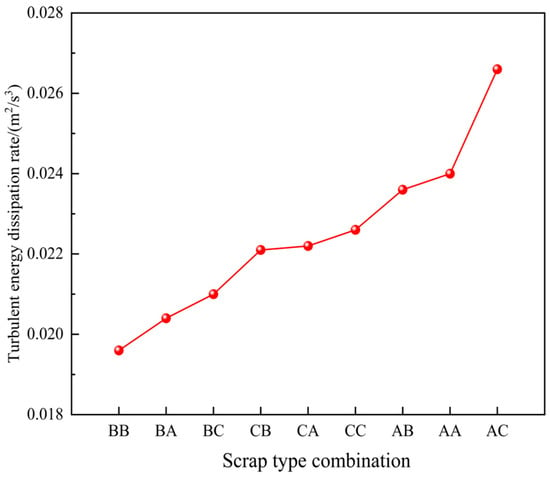

To quantitatively assess the influence of scrap steel type on average turbulent energy dissipation rate, rates under different scrap steel types are calculated and statistically analysed, as illustrated in Figure 29. Notably, when 90% of the scrap is rectangular, the average turbulent energy dissipation rate is highest, followed by that for the thin-plate and cylindrical forms. For scrap type AC, the average turbulent energy dissipation rate increases by 17.7% and 26.7% relative to types CC and BC, respectively. Therefore, based on the above analysis, using 90% rectangular scrap results in improved melt pool dynamics.

Figure 29.

The average turbulent energy dissipation rate of the melt pool for different scrap steel types.

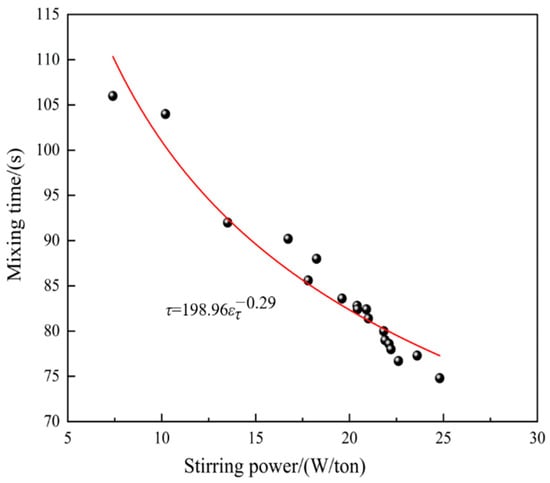

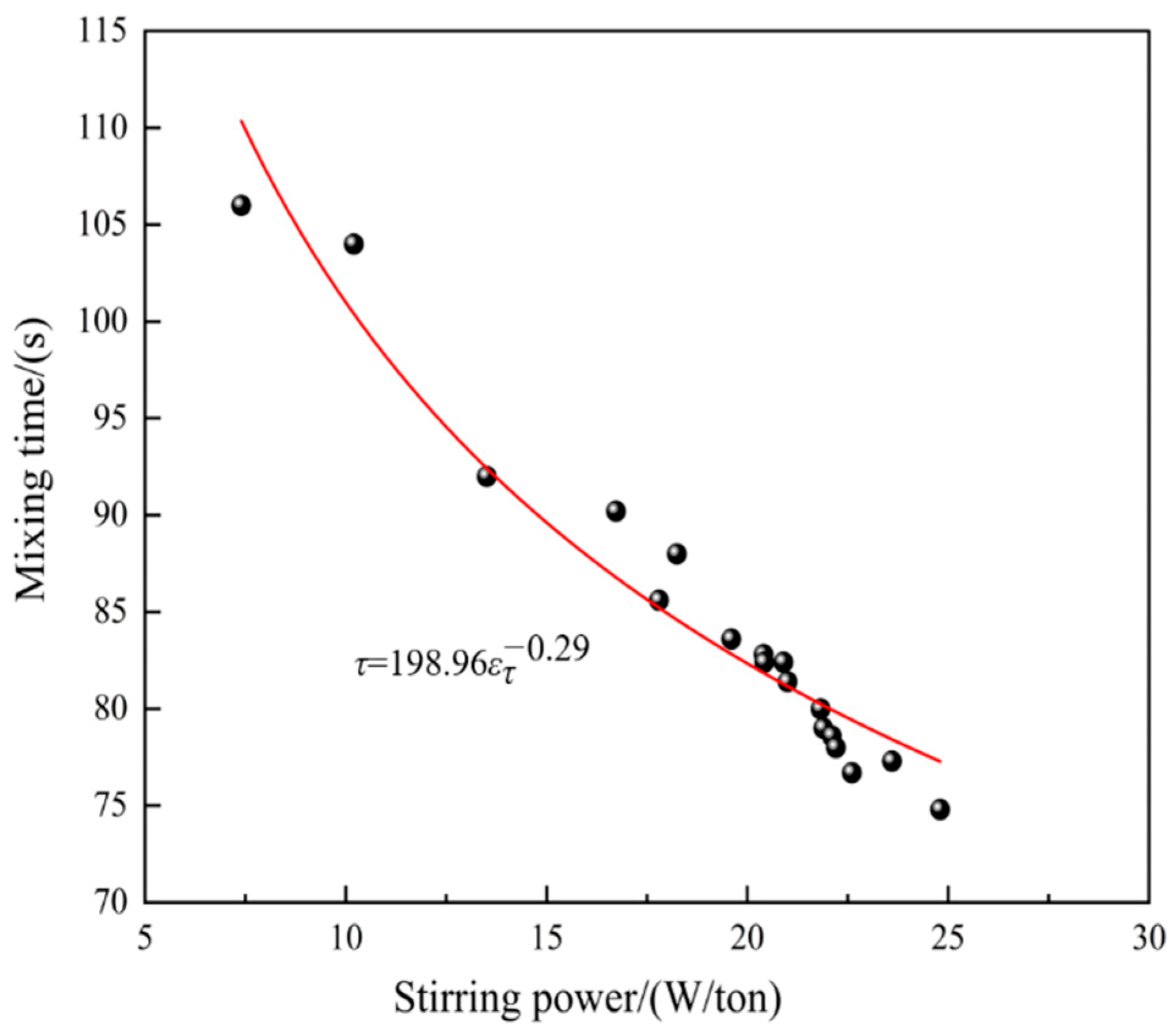

Based on the above findings, the state, distribution, material type and shape of scrap steel all influence the mixing time of the converter melt pool. This influence can be represented by the stirring power. Accordingly, an empirical formula (Equation (11)) is developed to describe the relationship between stirring power and mixing time under various scrap steel charging structures. The fitted curve is presented in Figure 30, with an R2 value of 0.93, indicating a strong functional relationship between stirring power and melt pool mixing time and confirming that the regression model exhibits a good fit. The graph illustrates that as the stirring power increases, the mixing time decreases. Here, stirring power is calculated by dimensionally converting the turbulent energy dissipation rate, as shown in Equation (12) [34].

In these equations, denotes the stirring power (W/ton) and represents the mixing time (s).

Figure 30.

The relationship between stirring power and mixing time under various scrap steel charging structures.

Figure 30.

The relationship between stirring power and mixing time under various scrap steel charging structures.

4. Conclusions

This study establishes a physical model of a 1:8.8 steel–scrap–gas three-phase flow furnace based on the principle of similarity. PIV technology and the stimulus–response method are employed to investigate the flow field distribution and mixing time of the converter melt pool under various scrap steel charging structures. It should be noted that this study established a pure isothermal physical water model; it did not simulate the melting and heat exchange processes of the scrap steel. Therefore, the conclusions are confined to the scope of fluid stirring efficiency, and this work serves as a foundation for subsequent, more complex models that incorporate melting, heat transfer and other processes—for example, the inclusion of light scrap and interactions among different types of scrap, slag and other factors represent important directions for future, more in-depth research.

The following conclusions are derived:

- (1)

- When scrap steel settles within the converter, the molten pool demonstrates enhanced dynamic behaviour. Specifically, when the scrap is rectangular in shape and the bottom-blowing gas flow rate is 750 m3/h, the mixing time decreases by 17.4%, the average velocity increases by 62.9% and the average turbulent energy dissipation rate rises by 62% compared to the hovering configuration.

- (2)

- When scrap steel is inclined within the converter, the molten pool exhibits more favourable dynamic characteristics. For instance, with rectangular scrap and a bottom-blowing gas flow rate of 750 m3/h, the mixing time decreases by 2% and 27.2%, the average velocity increases by 4% and 75.1% and the average turbulent energy dissipation rate rises by 7.8% and 77.4% compared to uniform and concentrated distributions, respectively. Nevertheless, from the perspective of scrap melting behaviour, uniform distribution remains the most appropriate configuration.

- (3)

- When the scrap steel comprises 90% medium scrap and 10% heavy scrap, the dynamic conditions of the molten pool are improved. Specifically, when the scrap is rectangular in shape and the bottom-blowing gas flow rate is 750 m3/h, the mixing time decreases by 19.6%, the average velocity increases by 71% and the average turbulent energy dissipation rate increases by 77.6% compared to the condition with all heavy scrap. Relative to the condition with all medium scrap, the mixing time decreases by 2.6%, average velocity increases by 5% and average turbulent energy dissipation rate increases by 9.6%.

- (4)

- When 90% of the scrap is rectangular in shape, the dynamic conditions of the molten pool are the most favourable, followed by those with thin plates and then those with cylindrical forms. At a bottom-blowing gas flow rate of 750 m3/h and under scrap steel type AC, the mixing time is reduced by 11.1% and 16.2%, respectively, compared to scrap types CC and BC. Similarly, the average velocity increases by 12.5% and 26.5% and the average turbulent energy dissipation rate increases by 17.7% and 26.7%, respectively.

- (5)

- The state, distribution, material type and shape of scrap steel each affect the mixing time of the converter melt pool, and this influence is captured by the stirring power. To quantify this relationship, an empirical formula is established for the converter water model melt pool under varying scrap steel charging structures: . This result illustrates that as stirring power increases, the mixing time of the melt pool decreases.

Finally, although this study reveals the significant enhancing effect of scrap structure optimisation on flow characteristics in a physical model, its scaling to industrial applications still requires consideration of practical constraints. Major challenges may include the equipment requirements for precise large-scale scrap steel distribution and the need to fine-tune similarity criteria due to variations in the physical properties of scrap steel across different steel plants, among others. However, from the perspective of application potential, this approach provides a new idea for enhancing bath stirring and improving smelting efficiency through scrap steel structure optimisation as a “low-cost” or “no-cost” method. It does not rely on additional energy input or equipment modification and its core value lies in unlocking the potential of existing processes through “intelligent charging”. Future research will involve collaboration with industry to conduct semi-industrial trials to quantify the specific benefits in terms of time and energy savings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.Y., X.L. (Xuan Liu) and A.X.; Methodology, F.Y., X.L. (Xuan Liu) and A.X.; Software, F.Y., X.L. (Xuan Liu) and X.L. (Xueying Li); Validation, F.Y., X.L. (Xuan Liu) and A.X.; Resources, A.X.; Data curation, X.L. (Xuan Liu) and X.L. (Xueying Li); Writing—original draft, F.Y. and X.L. (Xuan Liu); Writing—review and editing, A.X.; Supervision, A.X.; Funding acquisition, F.Y. and A.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Science and Technology Major Project (2025ZD1602500) and Advanced Materials—National Science and Technology Major Project (2025ZD0611200).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, X.-D.; Shangguan, F.-Q.; Xing, Y.; Hou, C.-J.; Tian, J.-L. Research on the low-carbon development technology route of iron and steel enterprises under the “double carbon” target. Chin. J. Eng. 2023, 45, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immonen, J.; Weingaertner, D.; Ketkaew, J.; Prasher, R.; Powell, K.M. Process intensification and comparison of electrolytic hydrogen green steel plants for industrial decarbonization. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 490, 144812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, G.; Liu, Y. Sustainable practices in steel manufacturing: Substitution elasticities between waste, raw materials, and energy for greenhouse gas emission reduction. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 477, 143845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Cai, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Peng, F.; Guo, R.; Peng, K.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, G. Coordinating interprovincial scrap supply for technology transition to minimize carbon emissions of china’s iron and steel industry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 6004–6015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, G.; Zhu, R.; Tang, T.; Dong, K. Study on the melting characteristics of steel scrap in molten steel. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2019, 46, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehlke, R.; Goodell, P.; Dunlap, R. Kinetics of steel dissolution in molten pig iron. Trans. Met. Soc. AIME 1965, 233, 1420–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosaka, M.; Minowa, S. Mass-transfer from graphite cylinder into liquid Fe-C alloy. Tetsu-to-Hagane 1967, 53, 1467–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, X.; Li, S.; Yang, S.; Zhao, M.; Li, J. Melting characteristics of steel scrap with different carbon contents in liquid steel. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2020, 47, 1087–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Gao, J.-T.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Yang, S.-F. Simulation on scrap melting behavior and carbon diffusion under natural convection. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2021, 28, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, X.; Yang, S.; Li, J.; Wu, J.; Zhao, M.; Ye, M. Physical model experiment and theoretical analysis of scrap melting process in electric arc furnace combined blowing system. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2020, 47, 748–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penz, F.M.; Schenk, J.; Ammer, R.; Klösch, G.; Pastucha, K. Evaluation of the influences of scrap melting and dissolution during dynamic linz–donawitz (LD) converter modelling. Processes 2019, 7, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Y. Experimental study on mass transfer during scrap melting in the steelmaking process. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2020, 47, 1006–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Nomura, H. Study on the rate of scrap melting in the steelmaking process. Tetsu-to-Hagane 1969, 55, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J. Steel dissolution in quiescent and gas stirred Fe/C melts. Metall. Trans. B 1989, 20, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penz, F.M.; Schenk, J.; Ammer, R.; Klösch, G.; Pastucha, K. Dissolution of scrap in hot metal under linz–donawitz (ld) steelmaking conditions. Metals 2018, 8, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penz, F.M.; Schenk, J. A review of steel scrap melting in molten iron-carbon melts. Steel Res. Int. 2019, 90, 1900124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruskopf, A. A model for scrap melting in steel converter. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2015, 46, 1195–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.K.; Deo, B. Scrap dissolution in molten iron containing carbon for the case of coupled heat and mass transfer control. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2013, 44, 1407–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Fang, Q.; Jia, J.; Huang, K.; Shi, W.; Liu, C.; Zhang, H. Melting mechanism of steel scrap in a converter with combined blowing. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 27, 7047–7058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Xu, A.; Yang, G.; Wang, H. Analyses and calculation of steel scrap melting in a multifunctional hot metal ladle. Steel Res. Int. 2019, 90, 1800435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gol’dfarb, E.; Sherstov, B. Heat and mass transfer when melting scrap in an oxygen converter. J. Eng. Phys. 1970, 18, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosaka, M.; Minowa, S. Dissolution of steel cylinder into liquid Fe-C alloy. Tetsu-to-Hagane 1967, 53, 983–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Ma, G.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, D. Numerical simulation on the melting kinetics of steel scrap in iron-carbon bath. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2022, 34, 101995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-U.; Pehlke, R. Mass transfer during dissolution of a solid into liquid in the iron-carbon system. Metall. Trans. 1974, 5, 2527–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Chen, C.; Lin, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhu, J.; Yang, S. Water model experiment on motion and melting of scarp in gas stirred reactors. Chin. J. Process Eng. 2022, 22, 954–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, P. Scrap dissolution effect in BOF converter process. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2023, 50, 1434–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isobe, K.; Maede, H.; Ozawa, K.; Umezawa, K.; Saito, C. Analysis of the scrap melting rate in high carbon molten iron. Tetsu-to-Hagane 2010, 76, 2033–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, X.; Chen, S.; Yang, S.; Ye, M.; Li, J. Melting characteristics of multipiece steel scrap in liquid steel. ISIJ Int. 2021, 61, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.K.; Dmitry, R.; Volkova, O.; Scheller, P.R.; Deo, B. Cold model investigations of melting of ice in a gas-stirred vessel. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2011, 42, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Lin, W.; Sun, J.; Sun, L.; Guo, W. An attempt to visualize the scrap behavior in the converter for steel manufacturing process using physical and mathematical methods. Mater. Trans. 2018, 59, 1829–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Deng, N.; Zhou, X.; Wang, D.; Peng, S. Influence of steel scrap on the mixing of converter bath. Chin. J. Process Eng. 2019, 19, 1178–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K. Principles of Metallurgical Transport; Metallurgical Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2011; ISBN 978-7-5024-5530-9. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, Y.W.M. Tundish Package Metallurgy; Metallurgical Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2019; ISBN 9787502482039. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, X.-Y.; Duan, H.-J.; Li, D.-H.; Xu, A.-J.; Zhang, L.-F. Water modeling on fluid flow and mixing phenomena in a BOF steelmaking converter. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2024, 31, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.