Abstract

Fine-Grained Visual Classification (FGVC) involves distinguishing highly similar subordinate categories within the same basic-level class, presenting significant challenges due to subtle inter-class variations and substantial intra-class diversity. While Vision Transformer (ViT)-based approaches have demonstrated potential in this domain, they remain limited by two key issues: (1) the progressive loss of gradient-based edge and texture signals during hierarchical token aggregation and (2) insufficient extraction of discriminative fine-grained features. To overcome these limitations, we propose a Gradient-Aware Token Injection Transformer, a novel framework that explicitly incorporates gradient magnitude and orientation into token embeddings. This multi-modal feature fusion mechanism enhances the model’s capacity to preserve and leverage critical fine-grained visual cues. Extensive experiments on four standard FGVC benchmarks demonstrate the superiority of our approach, achieving 92.9% top-1 accuracy on CUB-200-2011, 90.5% on iNaturalist 2018, 93.2% on NABirds, and 95.3% on Stanford Cars, thereby validating its effectiveness and robustness.

1. Introduction

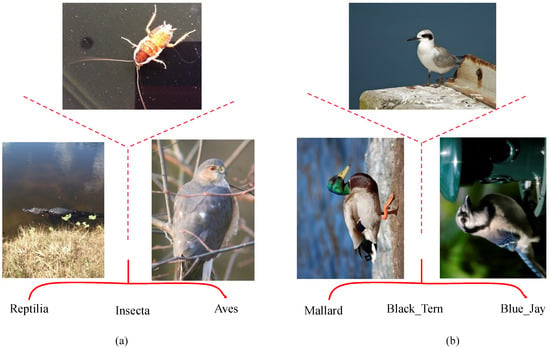

With the rapid progress of computer vision, visual classification has achieved remarkable success. Traditional methods aim to identify distinct basic-level categories such as cats, dogs, or cars, which typically exhibit substantial visual differences (Figure 1a). In contrast, fine-grained visual classification (FGVC) targets more challenging problems by distinguishing subordinate categories within the same basic-level class—for example, identifying different species of birds, breeds of dogs, or types of aircraft or flowers (see Figure 1b). This task is particularly challenging due to its low inter-class variance and high intra-class variance. Subtle differences such as feather patterns, beak shapes, or petal textures must be detected, which are often overlooked by conventional feature extraction approaches.

Figure 1.

(a) shows coarse-grained classification and (b) shows fine-grained classification.

Recent fine-grained visual classification (FGVC) methods can be broadly categorized into part localization–based approaches and attention-based approaches. Part localization methods explicitly detect and crop discriminative regions using predefined or learned rectangular anchors [1,2]. Although effective in isolating salient parts, these approaches often suffer from imprecise localization, inclusion of irrelevant background regions, and limited modeling of inter-part relationships, especially when discriminative cues are subtle or spatially fragmented.

Attention-based approaches alleviate the need for extra annotations by directly highlighting informative regions through learned attention mechanisms. In particular, Vision Transformers (ViTs) [3] dynamically reweight patch tokens via self-attention to capture global context and part-level importance [4,5,6]. Representative works include TransFG [7], which employs counterfactual attention to suppress background clutter and refine part-aware representations; MetaFormer-style models [8,9,10], which inject auxiliary meta-information into visual tokens to enhance semantic discrimination; and dual- or multi-stream fusion methods [11,12], which integrate features across layers or streams to improve representational capacity while remaining annotation-efficient. More recently, MPSA [13] introduces part sampling attention to enhance multi-granularity representations and implicitly adapt to object boundaries.

Despite these advances, we argue that existing FGVC methods still face fundamental limitations when distinguishing visually similar categories. Specifically, they predominantly rely on high-level semantic attention or part activation, while largely overlooking the explicit modeling of low-level gradient information that encodes fine-grained edge structures and subtle texture variations. ViT partitions input images into non-overlapping patches and converts them into tokens, which are then fed into stacked self-attention layers for global aggregation. The core issue leading to feature gradient attenuation lies in two key steps:

- 1.

- Patch Tokenization Step: Image feature gradients (capturing fine-grained spatial transitions, e.g., the edge of a car grille) are inherently defined at the pixel level. When converting pixels into fixed-size patch tokens, the local spatial gradient information is averaged within each patch, leading to an initial loss of high-frequency gradient details.

- 2.

- Self-Attention Aggregation Step: The self-attention mechanism fuses token features based on similarity scores, prioritizing global semantic consistency over local spatial gradient preservation. For stacked attention layers, this global fusion further smooths the spatial gradient information embedded in tokens: as tokens are repeatedly aggregated across layers, the distinct gradient cues that distinguish adjacent regions (e.g., between a headlight and the car body) are progressively diluted, resulting in attenuation of image content feature gradients.

As a result, even when attention successfully localizes relevant regions, the underlying representations may lack sufficient fine-grained detail to reliably separate closely related categories.

To address these challenges, we propose the Token Injection Transformer for Enhanced Fine-Grained Representation, which explicitly models image gradient magnitude and orientation as complementary cues to visual appearance. By extracting gradient information and encoding it into gradient tokens within the same embedding space as visual tokens, the proposed framework enables direct interaction between visual semantics and gradient-based structural information. This design preserves fine-grained edge and texture cues throughout the Transformer hierarchy, thereby enhancing the discriminative capacity of the model for FGVC tasks.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- 1.

- We provide an in-depth analysis of how multi-layer token aggregation in Vision Transformers progressively weakens gradient-based edge and texture information, highlighting an underexplored limitation of existing attention-based FGVC models.

- 2.

- We propose a token injection mechanism that encodes gradient magnitude and orientation into learnable tokens and integrates them with visual tokens via Transformer attention, enabling effective visual–gradient feature interaction without additional annotations.

- 3.

- Extensive evaluation on four standard FGVC benchmarks shows that the proposed Gradient-Aware Token Injection Transformer establishes new state-of-the-art accuracies of , , , and on CUB-200-2011, iNaturalist 2018, NABirds, and Stanford Cars, respectively, including a record-setting result on the NABirds benchmark.

2. Related Work

2.1. Fine-Grained Visual Classification

Fine-Grained Visual Classification (FGVC) aims to distinguish subordinate categories within the same basic object class (e.g., bird species or vehicle models), where inter-class differences are extremely subtle and models must focus on local discriminative features. Early approaches relied heavily on manually annotated parts or bounding boxes to guide the network’s attention to salient regions. While part-based annotation schemes provide precise localization of discriminative regions, the high annotation cost limits their scalability on large datasets.

To reduce dependence on manual annotations, subsequent studies have introduced self-supervised and weakly-supervised strategies. NTS-Net [1] employs a self-supervised mechanism for region proposal without part annotations; Bilinear CNN [14] uses outer-product operations to capture higher-order feature interactions; HBP [15] and DBTNet [2] enhance semantic representations via cross-layer bilinear structures and deep bilinear transformations, respectively. More recently, CAP [16] introduces context-aware attention pooling to improve semantic aggregation, and TransFG [7] integrates a part selection module within the Transformer framework to dynamically filter key tokens and boost classification accuracy.

In parallel, researchers have explored the incorporation of auxiliary modalities to enrich feature representations. KERL [8] fuses visual features with knowledge-graph nodes via graph neural networks; Presence-Only [9] integrates spatial-temporal priors during training; MetaFormer [10] combines textual descriptions, geolocation, and attribute information to generate more discriminative composite embeddings. Despite these advances, challenges remain in suppressing background noise and extracting the most representative fine-grained cues. To address this limitation, our work introduces Gradient Tokens, which explicitly encode high-frequency texture details and fuse them with semantic and spatial-temporal information through cross-modal attention, thereby enhancing discriminative power while preserving spatial coherence.

2.2. Transformer Architectures and Optimizations in Vision

The Transformer architecture, originally proposed by Vaswani et al. [17] for natural language processing, has become a dominant backbone due to its powerful global modeling capabilities. Dosovitskiy et al. [3] first adapted it to vision with the Vision Transformer (ViT), which partitions an image into fixed-size patches treated as tokens, achieving performance on par with or exceeding that of convolutional neural networks.

However, the quadratic complexity of global self-attention on high-resolution images has spurred numerous optimizations. ResMLP [18] replaces attention layers with pure MLP blocks to reduce computation, albeit at the expense of spatial modeling capacity; MetaFormer [19] explores pooling operations as substitutes for attention, which can lead to information loss; FourierFormer [6] seeks a balance between low- and high-frequency components but struggles to simultaneously capture both. Inspired by dual cross-attention mechanisms [5], some methods enhance interactions between global context and local high-response regions, while others [4,12] select salient tokens based on attention weights to capture subtle differences—yet often overlook explicit modeling of high-frequency textures.

Beyond attention efficiency, recent studies in related vision tasks have highlighted the importance of explicitly modeling structural cues and inductive priors to improve visual representations. For example, CausalSR [20] introduces a structural causal model with counterfactual inference to disentangle structural information from spurious correlations in super-resolution tasks, demonstrating the benefits of incorporating structured priors into deep vision models. Although targeting a different task, such findings underscore the value of explicitly encoding structural information for enhanced representation learning.

To fill this gap, we propose the Gradient Token Extraction (GTE) module within the Transformer architecture. GTE directly extracts gradient-based descriptors from feature maps and employs cross-attention with the original spatial tokens, thereby maintaining global semantic consistency while more accurately capturing fine-grained texture variations and significantly improving classification performance.

3. Methodology

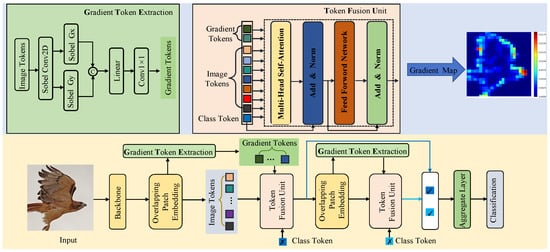

The overall architecture of the proposed Gradient-Aware Token Injection Transformer is illustrated in Figure 2. Given an input image, a convolutional backbone is first employed to extract dense feature maps, which are then converted into a sequence of image tokens through overlapping patch embedding to preserve local spatial continuity. However, standard tokenization schemes mainly encode appearance statistics and tend to suppress first-order spatial variations during successive feature aggregation. To explicitly preserve fine-grained gradient cues—such as edge contours and subtle texture transitions—that are critical for fine-grained recognition, we introduce a Gradient Token Extraction (GTE) module.

Figure 2.

Overview of the proposed Gradient-Aware Token Injection Transformer. The lower part shows the network pipeline. The upper part highlights the Gradient Token Extraction (GTE) module and the Token Fusion Unit (TFU) with corresponding gradient token visualizations. In the legend, ✗ denotes the initial token and ✓ the updated one.

The extracted gradient tokens are subsequently injected into the Transformer via a Token Fusion Unit (TFU), where they interact with image tokens and a learnable class token through multi-head self-attention. A two-stage fusion strategy is adopted to progressively refine token representations, and the class tokens from different stages are finally aggregated to produce the fine-grained classification output.

3.1. Image Tokenization

Fine-grained visual recognition requires preserving subtle local patterns while maintaining spatial coherence for subsequent global reasoning. Given an input image

we first extract hierarchical visual features using a convolutional backbone :

where B denotes the batch size, D is the channel dimension, and are the spatial resolutions of the backbone output. The convolutional backbone consists of a shallow convolutional stem followed by Mobile Inverted Bottleneck Convolution (MBConv) blocks equipped with squeeze-and-excitation modules, enabling efficient local feature extraction with adaptive channel-wise modulation.

This backbone is custom-designed for our framework and does not correspond to standard architectures such as EfficientNet or ConvNeXt. Its structure is fixed across all experiments and serves solely to introduce local convolutional inductive biases prior to Transformer-based global reasoning.

To transform the dense feature map Z into a sequence representation suitable for Transformer processing, we employ an overlapping patch embedding operator implemented via convolution. Using a kernel size k, stride , and appropriate padding, the operator performs spatial downsampling and feature projection simultaneously:

where d denotes the embedding dimension and is the number of patch tokens arranged on a spatial grid of size . Compared with non-overlapping partitioning, overlapping embeddings better preserve boundary continuity and fine texture variations, which are essential for distinguishing visually similar categories.

3.2. Gradient Tokenization

Although patch embeddings encode local appearance information, they do not explicitly emphasize first-order spatial variations such as edges or contour transitions. To enhance sensitivity to such structural cues, we derive gradient-aware tokens directly from the patch embeddings.

Specifically, the patch token sequence T is reshaped back into a spatial feature map:

which restores the two-dimensional neighborhood structure required for spatial derivative estimation.

We then compute channel-wise horizontal and vertical gradients using a single, fixed Sobel operator implemented as depth-wise convolutions. The Sobel kernels are defined as

Applying these kernels independently to each channel yields

where denotes depth-wise convolution with unit padding. The horizontal and vertical responses jointly encode gradient magnitude and directional information and are concatenated along the channel dimension:

Flattening the spatial dimensions produces an initial sequence of gradient descriptors:

where corresponds to the number of spatial locations and aligns with the number of visual patch tokens. To align descriptor dimensionality with the original patch embeddings, a learnable linear projection is applied:

resulting in projected gradient tokens .

To reduce redundancy and suppress noisy responses while retaining spatially consistent structural patterns, we further apply a lightweight one-dimensional convolution along the token dimension:

where is a predefined hyperparameter that controls the number of gradient tokens retained. This design balances gradient expressiveness and computational efficiency without excessive token growth. By default, N is fixed for a given backbone configuration; specific values used in our experiments are reported in the implementation details and ablation studies.

3.3. Token Fusion Unit

Different token types capture complementary visual cues: patch tokens encode local appearance, gradient tokens emphasize structural transitions, and a learnable class token aggregates global semantic context. To jointly exploit these heterogeneous representations, we introduce a Token Fusion Unit (TFU) that enables unified modeling through self-attention.

Let denote the learnable class token (broadcast across the batch), the patch tokens, and the refined gradient tokens. These tokens are concatenated in a global-to-local order:

where .

The fused token sequence is processed by a stack of Transformer layers with pre-normalization. For the n -th layer, the update equations are:

where denotes multi-head self-attention, is the position-wise feed-forward network, and represents Layer Normalization.

Within the attention module, normalized tokens are projected to queries, keys, and values:

where . To explicitly model interactions across different token types, a learnable bias matrix

is incorporated to modulate the attention logits:

By jointly attending over semantic, structural, and appearance cues, the proposed Token Fusion Unit facilitates the learning of more discriminative representations for fine-grained visual classification.

4. Results

This section provides an in-depth evaluation of the proposed Gradient-Aware Token Injection Transformer across four widely adopted benchmarks for fine-grained visual classification. We begin by introducing the datasets used in our experiments, followed by a detailed description of the experimental setup. Subsequently, we conduct comparative experiments against existing state-of-the-art methods, supported by quantitative results and visual analysis. Finally, ablation studies are carried out to evaluate the effectiveness and contribution of each individual component within the proposed framework.

4.1. Datasets and Implementation Details

4.1.1. Datasets

We evaluate our method on four widely adopted fine-grained classification benchmarks (Table 1): iNaturalist 2018 [21], NABirds [22], CUB-200-2011 [23], and Stanford Cars [24].

Table 1.

Dataset statistics and initial learning rates used in our experiments.

The iNaturalist 2018 dataset comprises large-scale, real-world RGB images spanning diverse categories such as plants, animals, and fungi, and is particularly challenging due to severe class imbalance and domain shifts. The Stanford Cars dataset focuses on fine-grained car model classification, where subtle appearance differences among hundreds of vehicle types demand strong discrimination capability. CUB-200-2011 targets bird species classification and is characterized by high inter-class similarity and large intra-class variations caused by lighting, pose, and viewpoint changes. NABirds builds upon CUB-200-2011 by incorporating a hierarchical taxonomy and introducing additional appearance variations due to seasonal changes. For all datasets, we strictly follow the officially provided training and testing splits.

All datasets consist of RGB images with varying original resolutions. Specifically, iNaturalist 2018 contains high-resolution natural images with diverse aspect ratios, typically exceeding pixels. CUB-200-2011 images are mostly centered bird photographs with resolutions around pixels. NABirds shows larger resolution variations due to varying capture conditions and camera settings. Stanford Cars images are generally high-quality RGB photographs, with resolutions ranging from approximately to above pixels. For the sake of ensuring consistency in training and evaluation, all images are resized to pixels, which helps to standardize the input data and facilitate fair comparison among different methods.

For datasets where auxiliary metadata are available (iNaturalist 2018 and CUB-200-2011), we follow prior works such as MetaFormer and incorporate the same metadata signals during training. For datasets without metadata (NABirds and Stanford Cars), all methods are evaluated under purely visual input settings. Our approach operates independently of metadata modeling (i.e., it does not rely on metadata for its core functionality) and focuses on enhancing visual representations through gradient-aware token integration.

4.1.2. Implementation Details

All experiments are conducted in a Linux environment using Python 3.8. Our implementation is based on PyTorch [25] (version 1.13.1) with torchvision version 0.14.1. We adopt the timm library (version 0.4.5) for model components and training utilities. NVIDIA Apex is used to enable mixed-precision training and performance optimization.Additional dependencies include OpenCV (opencv-python 4.5.1.48) for image processing and YACS (version 0.1.8) for configuration management.

We employ a convolutional backbone initialized with weights pretrained on iNaturalist 2021, and resize all input images to pixels. Training is conducted on two NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPUs using the AdamW optimizer [26] with a weight decay of , and the learning rate is scheduled using cosine annealing. Standard data augmentations—including random cropping, horizontal flipping, and color jitter—are applied, together with stochastic depth regularization (maximum drop rate of ). All models are trained for a total of 300 epochs with a batch size of 16. To stabilize convergence, a warm-up phase is adopted: 20 epochs for CUB-200-2011 and 5 epochs for the remaining datasets.

4.2. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Methods

4.2.1. Results on the iNaturalist 2018 Dataset

Table 2 presents a comparison of our model with several representative methods on the iNaturalist 2018 benchmark: Geo-Aware [27], which filters predictions using a whitelist of image cues in post-processing; Presence-Only [9], which incorporates spatio-temporal priors during training; and MetaFormer [10], which fuses visual features with spatio-temporal tokens via joint attention.

Table 2.

Comparison with state-of-the-art methods on iNaturalist 2018.

Building upon these approaches, our model introduces dedicated gradient tokens that explicitly encode high-frequency image details—such as edges, fine textures, and subtle pattern variations—often underrepresented by standard attention mechanisms applied to raw pixel embeddings. The inclusion of gradient information enables the model to better distinguish between visually similar species and suppress background distractions, resulting in more precise localization of discriminative regions. These gradient tokens are effectively integrated with class and spatio-temporal tokens through a cross-modal attention mechanism, allowing the network to dynamically balance texture-based cues with semantic and contextual information.

As shown in Table 2, our model achieves a top-1 accuracy of 90.5% on the large-scale iNaturalist 2018 dataset, demonstrating that explicit modeling of gradient information can significantly enhance performance in fine-grained visual classification.

4.2.2. Results on the CUB-200-2011 Dataset

As shown in Table 3, our model achieves a top-1 accuracy of 92.9% on CUB-200-2011, setting a new state-of-the-art performance benchmark and exceeding TransFG [7] by over 1.2%. While MetaFormer [10] leverages textual metadata to enrich representations, the Gradient-Aware Token Injection Transformer instead incorporates gradient tokens to explicitly encode fine-grained texture details. Previous methods like IELT [42] and FFVT [11] use separate attention heads to extract part features, but this can disrupt spatial coherence. To overcome this limitation, we introduce the Gradient Token Extraction (GTE) module, which restores lost texture information without sacrificing spatial structure. Embedding gradient cues in this way sharpens the model’s focus on subtle variations and underlies the improved classification performance.

Table 3.

Comparison with state-of-the-art methods on CUB-200-2011. MetaFormer (baseline) and our method are evaluated under different pretraining datasets to isolate the effect of initialization.

4.2.3. Results on the NABirds Dataset

As shown in Table 4, our model achieves a top-1 accuracy of 93.2% on NABirds, significantly surpassing TransIFC’s 90.9% [48] and MPSA’s 92.5% [13]. The performance gain can be attributed to our method’s ability to preserve the complete token sequence, thereby enriching the feature representations. Unlike MPSA, which relies on partial region sampling [13], our model directly integrates discriminative descriptors into the feature map, allowing for more effective capture of fine-grained visual distinctions and consequently enhancing classification accuracy.

Table 4.

Comparison with state-of-the-art methods on NABirds.

4.2.4. Results on the Stanford Cars Dataset

As shown in Table 5, our model achieves an accuracy of 95.3% on Stanford Cars, matching the current state-of-the-art performance. Unlike TransFG [7], which relies solely on spatial features and omits explicit gradient modeling, the Gradient-Aware Token Injection Transformer introduces dedicated gradient tokens that enhance the modeling of fine-grained details (e.g., badge textures) while preserving the overall shape information (e.g., vehicle silhouette). These gradient tokens are derived from image gradients and encode high-frequency texture cues that are often overlooked by standard attention mechanisms. By integrating these gradient cues into the spatial feature maps, the model more effectively captures subtle visual distinctions, demonstrating the potential benefit of gradient-aware modeling for fine-grained classification.

Table 5.

Comparison with state-of-the-art methods on Stanford Cars.

It is worth noting that our method yields tied performance with the baseline work MPSA [13]. After careful re-examination of the dataset and experimental results, we propose two potential explanations for this phenomenon:

- 1.

- Dataset-specific feature dominance: The Stanford Cars dataset contains a large number of images with highly similar geometric structures (e.g., same car models with different colors or backgrounds). In such cases, color and texture features may play a more dominant role than fine-grained geometric details in classification tasks. Gradient tokens, which are designed to highlight geometric features, thus do not provide a significant edge over existing methods on this dataset.

- 2.

- Limited feature discrimination: The current design of gradient tokens focuses on local geometric feature extraction but lacks a global feature aggregation mechanism. For car images with subtle differences in grilles/headlights, the local geometric cues captured by gradient tokens may not be sufficient to distinguish between similar categories, leading to saturated performance.

In future work, we plan to address this issue by exploring two directions: integrating cross-modal feature fusion to enhance feature representation and designing a dynamic weighting module to adaptively emphasize dataset-specific critical geometric regions.

4.3. Visual Analysis

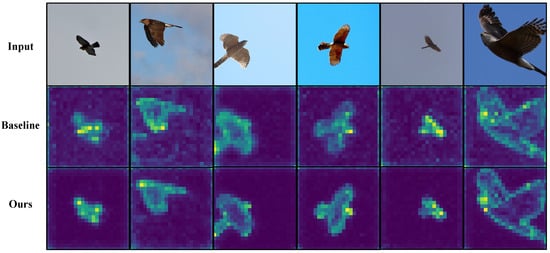

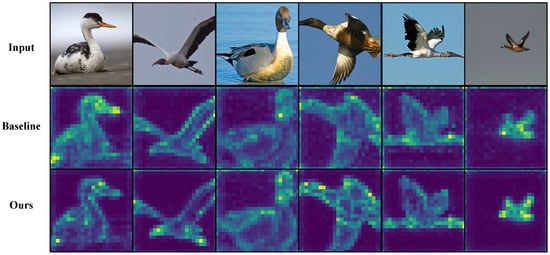

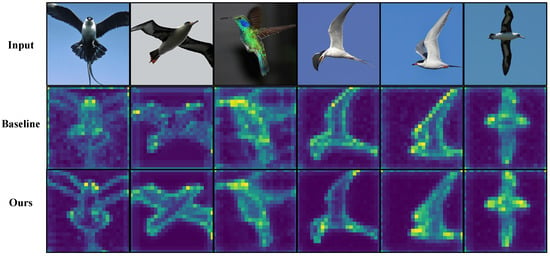

4.3.1. Qualitative Attention Analysis Across Datasets

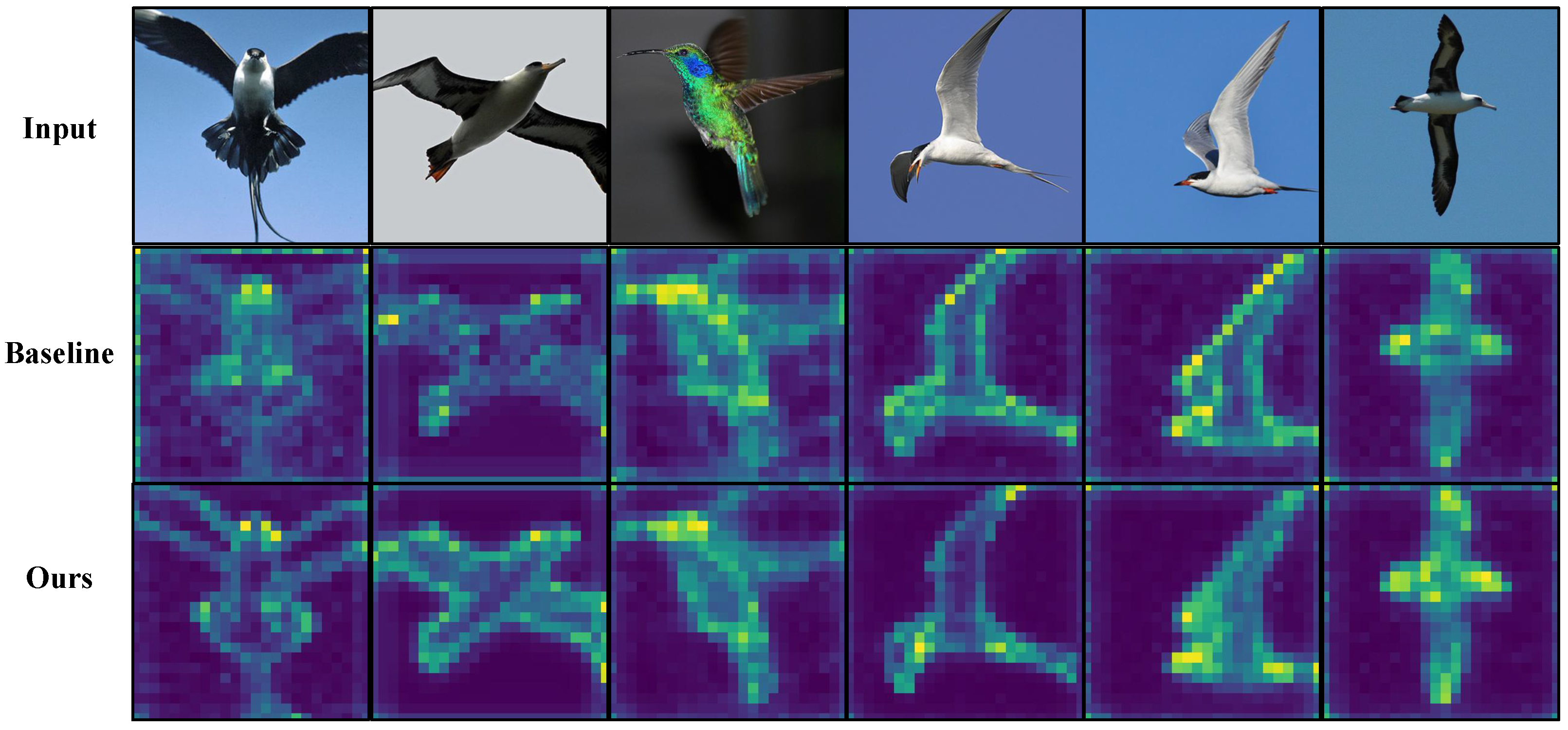

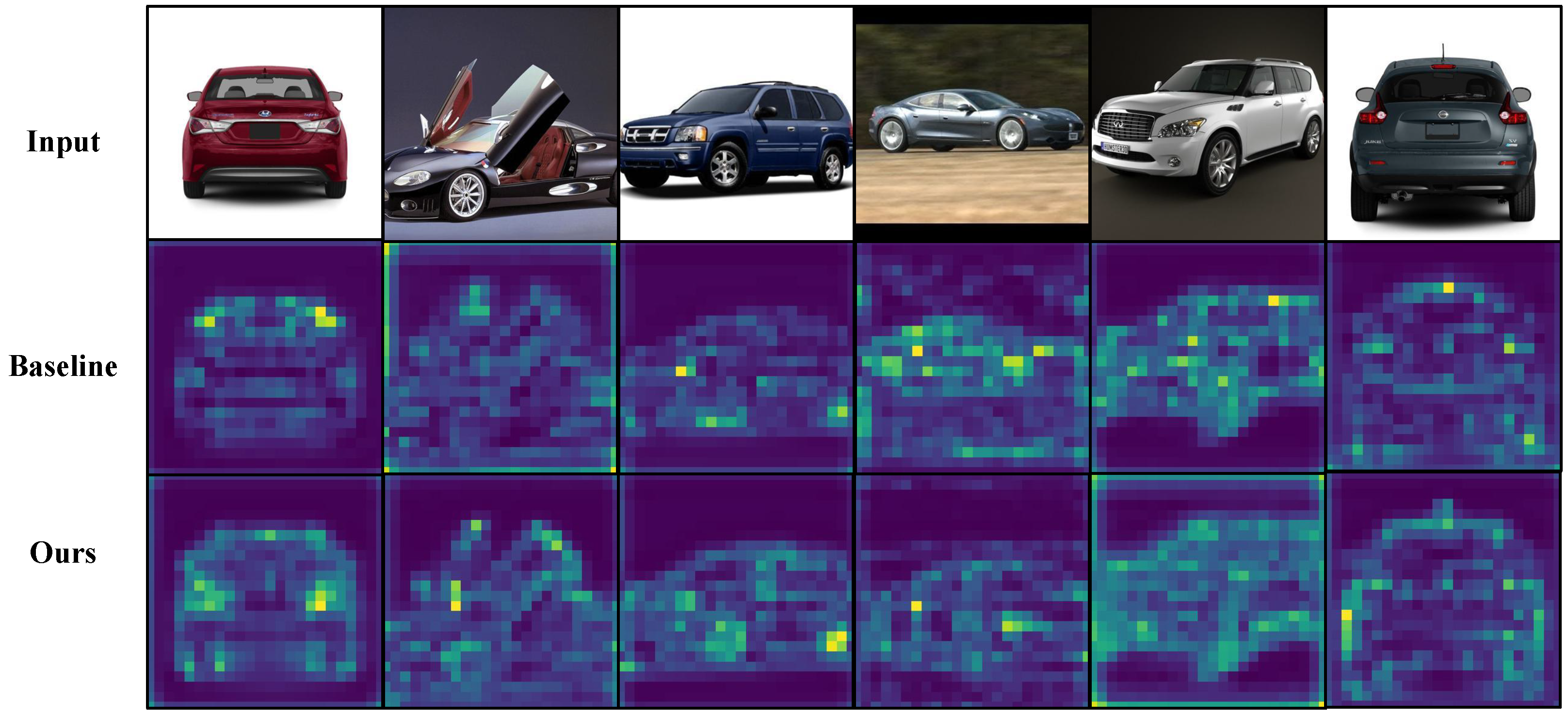

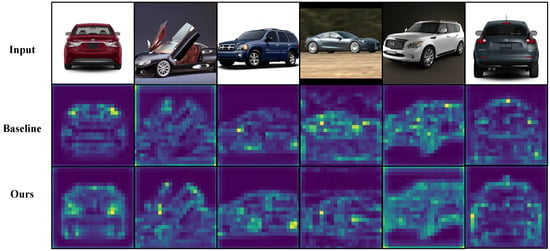

To better understand how gradient-aware token injection influences model behavior, we conduct a qualitative token-level attention analysis across all four datasets. Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 present representative examples from iNaturalist 2018, NABirds, CUB-200-2011, and Stanford Cars, respectively. Each figure contains three rows: the input image (top), the attention map produced by the baseline MetaFormer model without gradient token extraction (middle), and the attention map generated by our Gradient-Aware Token Injection Transformer (bottom).

Figure 3.

Qualitative results on iNaturalist 2018. The first row shows the input images, the second row shows the baseline results, and the third row shows the results of our method. Light-colored regions indicate higher responses to the class token. Our method shows improved focus on species-specific textures and patterns despite high intra-class variation and cluttered scenes.

Figure 4.

Qualitative results on NABirds. The first row shows the input images, the second row shows the baseline results, and the third row shows the results of our method. Light-colored regions indicate higher responses to the class token. Our method achieves better object localization under complex backgrounds and varying poses, while the baseline often drifts to irrelevant regions.

Figure 5.

Qualitative results on CUB-200-2011. The first row shows the input images, the second row shows the baseline results, and the third row shows the results of our method. Light-colored regions indicate higher responses to the class token. The proposed method generates more precise attention on discriminative parts (e.g., head, beak, wings), with reduced background distraction.

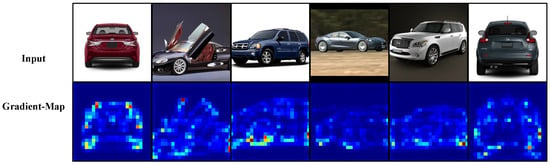

Figure 6.

Qualitative results on Stanford Cars. The first row shows the input images, the second row shows the baseline results, and the third row shows the results of our method. Light-colored regions indicate higher responses to the class token. The proposed method focuses more consistently on key structural components (e.g., headlights, grille, wheels), capturing fine-grained shape differences better than the baseline.

From these visualizations, we observe that the baseline model frequently distributes attention over background regions or coarse object areas, reflecting its reliance on global semantic aggregation. In contrast, after injecting gradient tokens, the model exhibits more spatially concentrated attention on object contours, texture boundaries, and fine structural regions that are known to be discriminative in fine-grained recognition. Notably, this effect is most evident in regions with strong edge or texture variations, such as feather boundaries in birds and part outlines in vehicles.

These qualitative differences indicate that gradient-aware token injection does not merely reweight existing attention patterns, but instead provides explicit high-frequency structural cues that guide attention toward physically meaningful local details. Importantly, the observed attention refinement is consistent across datasets with diverse visual characteristics, suggesting that the proposed mechanism systematically mitigates the attenuation of gradient information during token aggregation. This behavior offers a qualitative explanation for the observed performance improvements, particularly in scenarios where subtle edge and texture cues are critical for distinguishing visually similar categories.

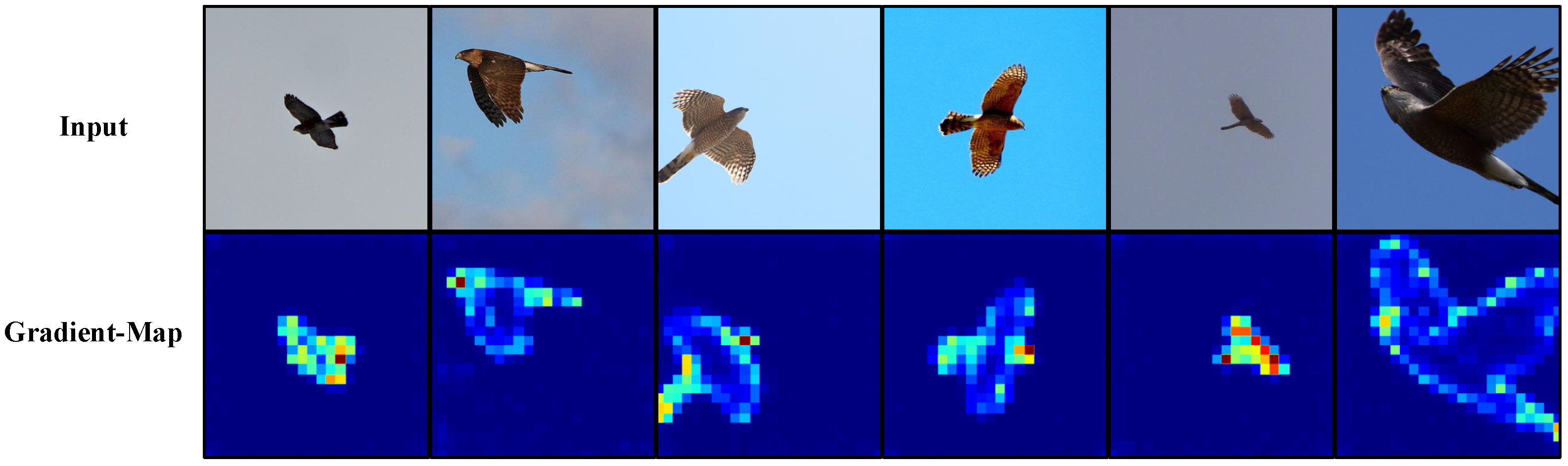

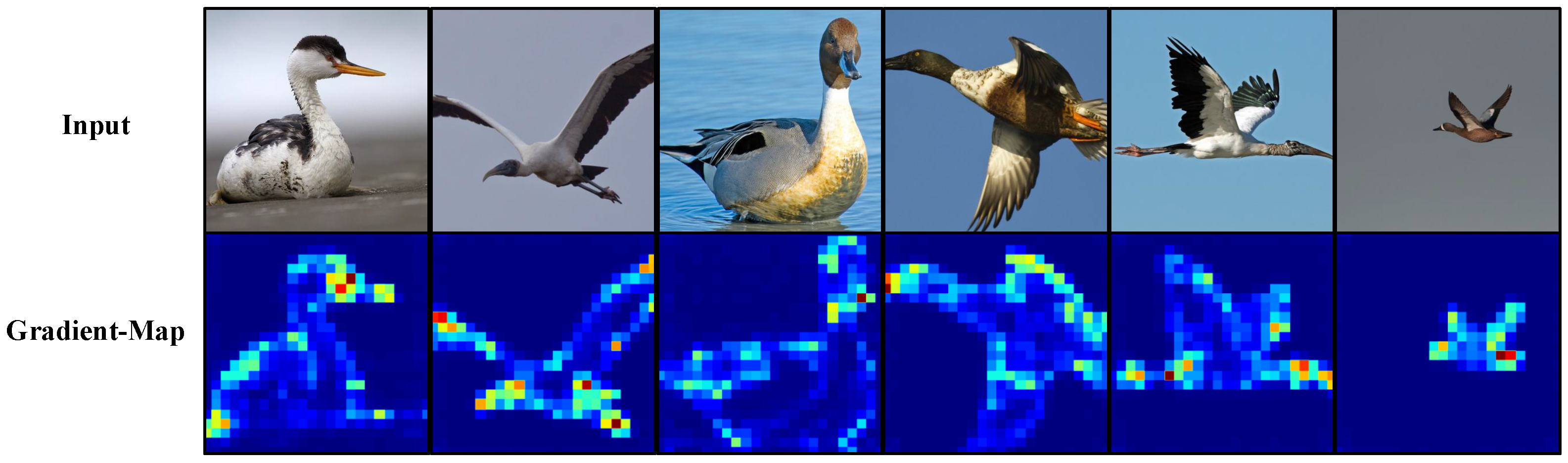

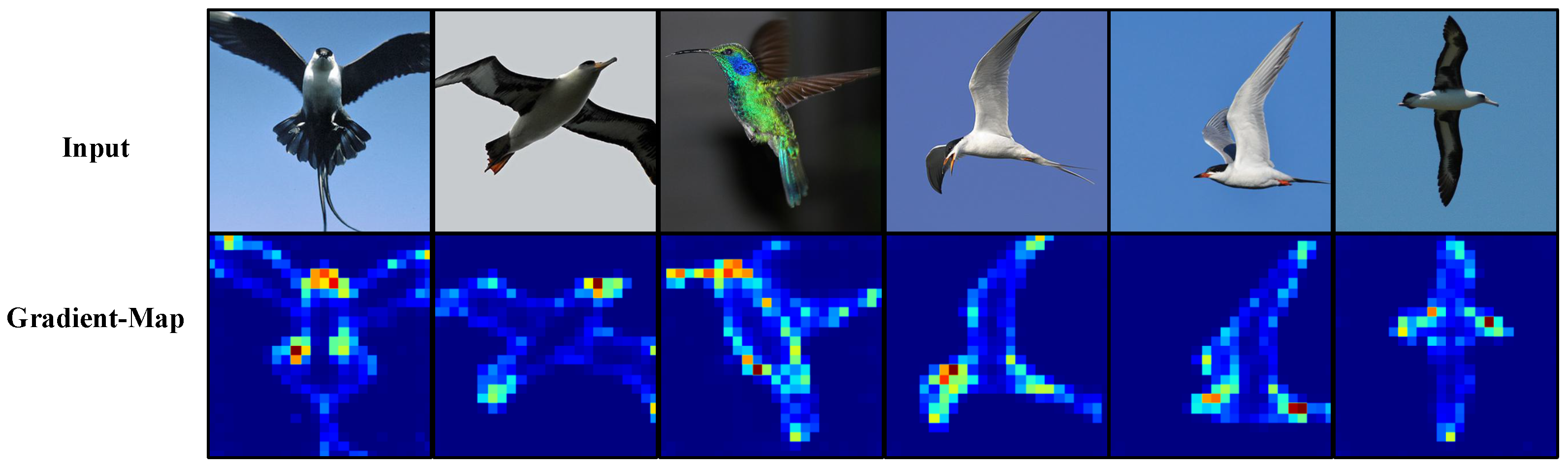

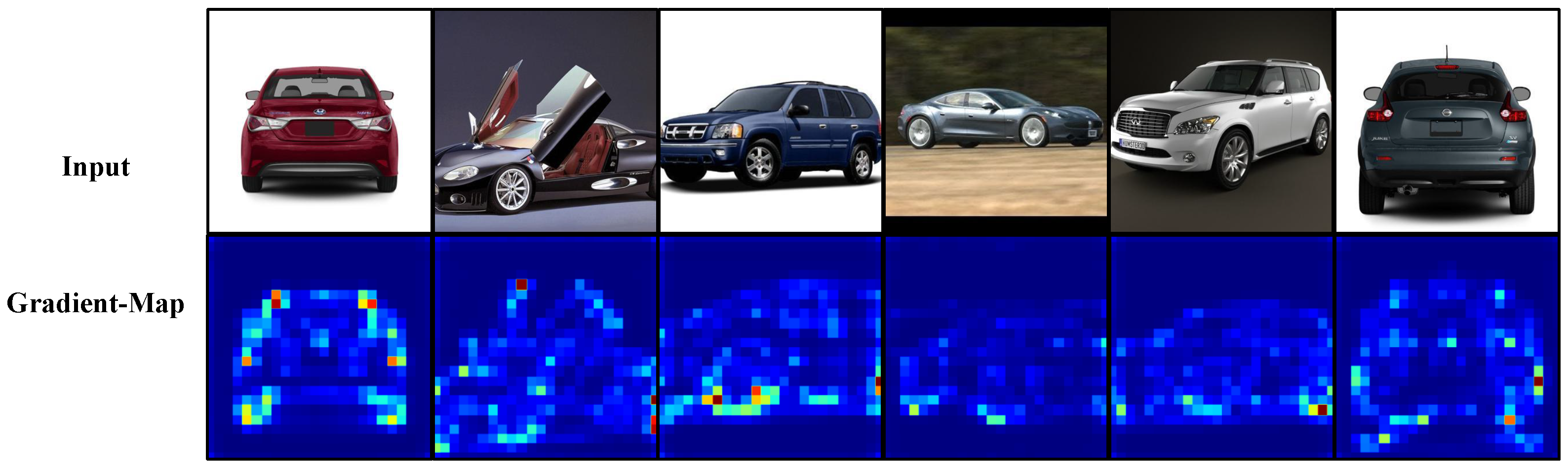

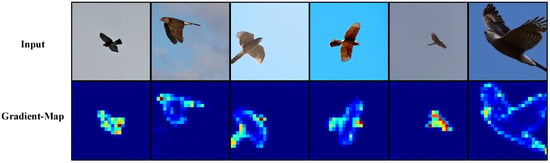

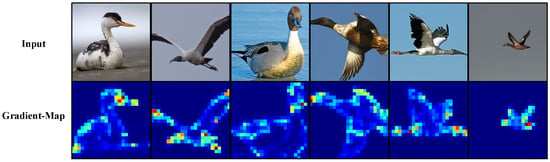

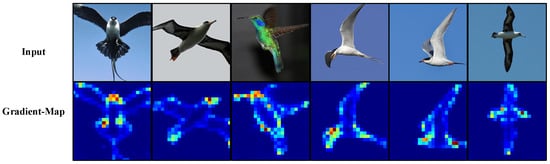

4.3.2. Gradient Token Activation Maps

To further analyze the role of the proposed Gradient Token Extraction (GTE) module, we visualize gradient token activation maps across multiple fine-grained benchmarks, including CUB-200-2011, NABirds, iNaturalist 2018, and Stanford Cars. Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10 present representative examples from each dataset. Each visualization consists of two rows: the input image (top) and the corresponding gradient token activation map (bottom).

Figure 7.

Gradient visualization on iNaturalist 2018. Gradient tokens effectively highlight species-specific textural patterns, even under significant intra-class variation and occlusion. Lighter colors indicate stronger gradient responses.

Figure 8.

Gradient visualization on NABirds. Despite cluttered backgrounds and varying poses, the gradient tokens capture clear object boundaries and local texture variations which are critical for accurate recognition. Lighter colors indicate stronger gradient responses.

Figure 9.

Gradient visualization on CUB-200-2011. The activation map (bottom) strongly responds to fine feather patterns, wing edges, and beak contours, aligning well with discriminative visual cues. Lighter colors indicate stronger gradient responses.

Figure 10.

Gradient visualization on Stanford Cars. The response emphasizes sharp geometric structures such as headlights, grilles, and wheel arches, capturing shape-defining edges with high fidelity. Lighter colors indicate stronger gradient responses.

Across all datasets, the gradient token activations predominantly respond to high-frequency structural components, such as object contours, part boundaries, and localized texture transitions. These regions are well known to encode discriminative cues in fine-grained recognition tasks, particularly when inter-class differences are subtle. Importantly, the activation patterns remain spatially coherent under variations in pose, illumination, and background clutter, indicating that the GTE module consistently captures intrinsic structural information rather than dataset-specific appearance biases.

Unlike attention maps, which reflect the model’s allocation of importance during classification, gradient token activation maps directly reveal the type of information encoded by the injected tokens. The observed activations suggest that GTE explicitly preserves low-level gradient cues that are otherwise weakened during deep token aggregation. This complementary evidence supports the effectiveness of gradient-aware token learning as a mechanism for retaining fine-grained structural details throughout the Transformer hierarchy.

4.4. Ablation Study

4.4.1. Effectiveness of the Proposed Modules

A key component of the proposed Gradient-Aware Token Injection Transformer is the Gradient Token Extraction module (GTE), which explicitly encodes image gradient cues—such as edges and fine textures—into dedicated tokens to augment the standard visual representation. As shown in Table 6, integrating the GTE module into MetaFormer [10] consistently improves performance across multiple fine-grained benchmarks. On iNaturalist 2018, the enhancement reaches nearly 2%, demonstrating the effectiveness of gradient-aware modeling in complex, real-world biodiversity scenes with significant intra-class variation. Notably, on the challenging NABirds dataset, our model achieves an accuracy of 93.2%, the highest reported to date. These results highlight that the GTE module not only provides complementary high-frequency structural cues but also generalizes well across diverse and realistic fine-grained classification scenarios.

Table 6.

Ablation studies of the proposed Gradient Token Extraction (GTE) module. All results are based on the MetaFormer [10] backbone.

4.4.2. Effect of Gradient Token Count on Model Performance

We study the impact of the number of gradient tokens in the GTE module. As shown in Table 7, performance on the CUB-200-2011 dataset peaks with 16 tokens, achieving the optimal balance between accuracy and computational efficiency. This configuration is adopted as the default. Similar trends are observed on other datasets, suggesting that 16 gradient tokens provide consistent and generalizable performance across different fine-grained classification tasks.

Table 7.

Effect of the number of gradient tokens on model accuracy (%) on CUB-200-2011.

4.4.3. Evaluation Beyond Accuracy

To provide a more comprehensive assessment, we evaluate our model using macro and weighted F1-scores, as well as macro AUC, in addition to top-1 and top-5 accuracy. As shown in Table 8, our model achieves consistently strong performance across all datasets, demonstrating both high accuracy and robust class-wise discrimination.

Table 8.

Performance of the model on fine-grained datasets in terms of top-1/top-5 accuracy, F1-scores, and macro AUC. All values are rounded to two decimal places.

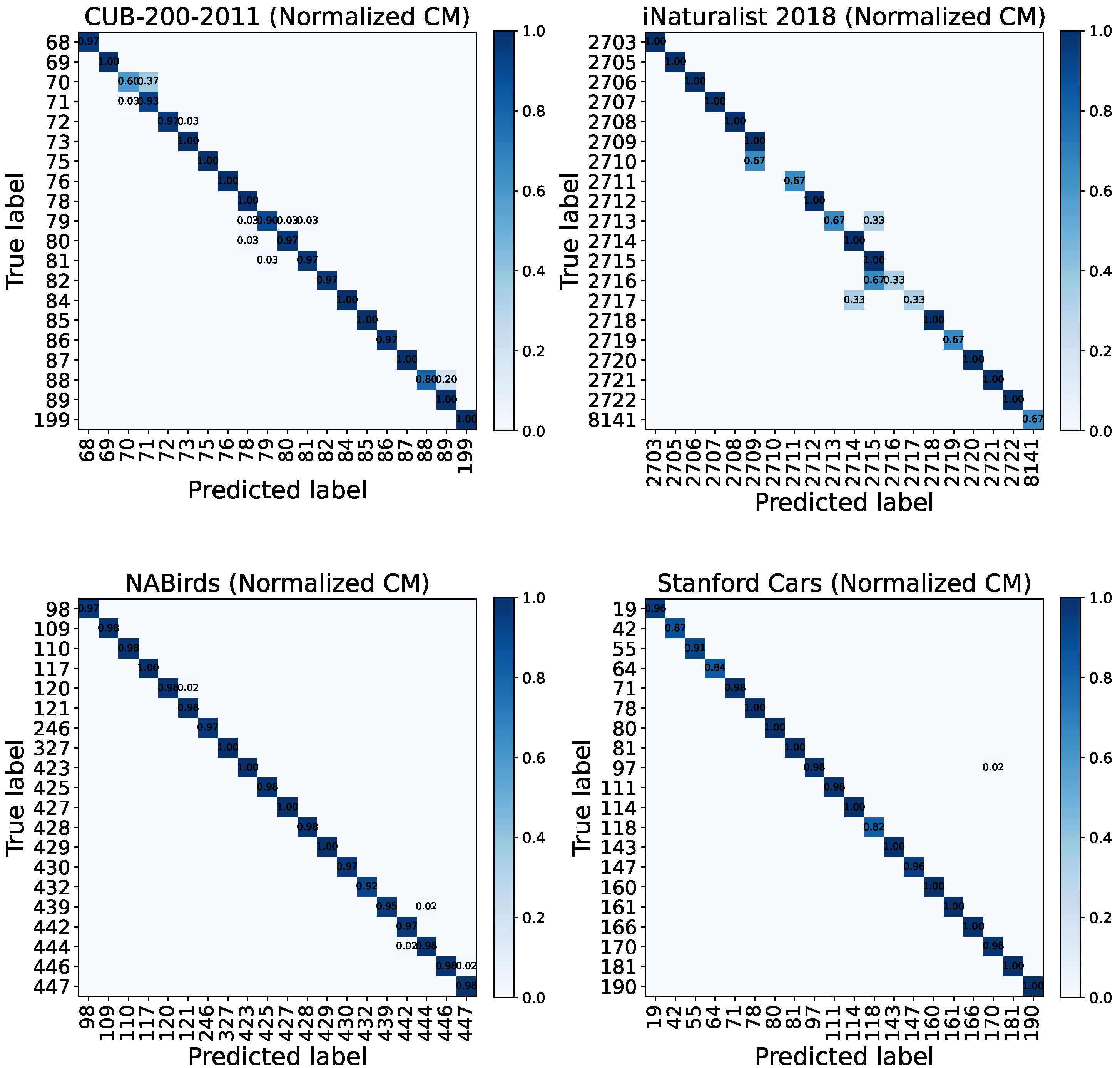

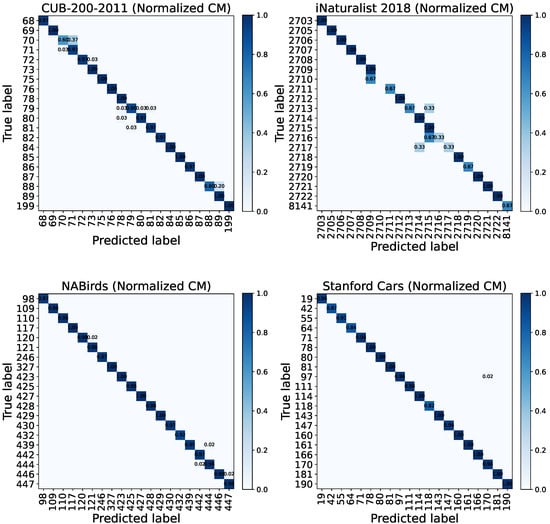

4.4.4. Confusion Matrix Analysis

To gain a deeper understanding of the model’s behavior, Figure 11 presents the normalized confusion matrices on several representative fine-grained benchmarks. Overall, most classes exhibit strong diagonal dominance, indicating consistent and reliable per-class discrimination.

Figure 11.

Normalized confusion matrices for the top-20 classes () on four fine-grained datasets.

Across datasets, misclassifications are sparse and mainly concentrated among visually similar classes. In particular, CUB-200-2011 and NABirds show near-perfect diagonals with only minor localized confusions, while Stanford Cars exhibits almost uniform diagonal dominance, reflecting strong discrimination for man-made object categories. In contrast, iNaturalist 2018 displays relatively more off-diagonal probability mass, which can be attributed to its long-tailed distribution and higher intra-class variance.

Overall, the confusion-matrix analysis is consistent with the quantitative results (accuracy, F1-score and macro AUC as in Table 8) and suggests that the proposed method learns robust and class-discriminative representations, with remaining errors largely driven by dataset-intrinsic challenges rather than random mispredictions.

4.5. Model Complexity Evaluation

As shown in Table 9, the proposed method achieves an excellent trade-off between model complexity and recognition performance. Taking MetaFormer as the baseline, our model introduces only a marginal increase in parameters (86.9 M vs. 81.0 M) and FLOPs (51.35 G vs. 50.01 G), while improving accuracy from 92.8% to 93.2%. This demonstrates that the proposed design effectively enhances feature representation under a strictly controlled computational budget. All measurements are conducted on a single NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 with a batch size of 16, and values are averaged over multiple runs after a proper warm-up phase to ensure reliability.

Table 9.

Comparison of input resolution, parameters, GFLOPs, and top-1 accuracy (%) on the NABirds dataset.

Specifically, the MetaFormer baseline achieves an inference throughput of 44.16 images/s with a peak GPU memory consumption of 9170 MB. In contrast, our method yields a throughput of 39.10 images/s and a peak GPU memory usage of 11,234 MB. The slight decrease in throughput and increase in memory footprint can be directly attributed to the additional feature-enhancement blocks we introduced, which bring extra model parameters and intermediate activation computations.

Notably, this minor computational overhead is well justified by the performance gain: our method improves classification accuracy by 0.4% (from 92.8% to 93.2%) with only a marginal increase in parameters (+5.9 M, from 81.0 M to 86.9 M) and FLOPs (+1.34 G, from 50.01 G to 51.35 G). Collectively, these comprehensive results demonstrate that our proposed method maintains an excellent trade-off between recognition performance and computational cost.

5. Conclusions

We have presented a Gradient-Aware Token Injection Transformer for fine-grained visual classification. This method explicitly extracts the gradient magnitude and orientation from intermediate feature maps using a fixed Sobel operator and injects them as dedicated gradient tokens. These gradient tokens are aligned and jointly processed with visual tokens through self-attention mechanisms. By facilitating direct interaction between appearance tokens and gradient tokens, the model captures complementary structural cues, thereby enhancing its sensitivity to subtle texture-, shape-, and part-level differences.

Extensive experiments on four standard fine-grained visual classification (FGVC) benchmarks demonstrate that our approach consistently improves performance over strong baselines while only incurring a marginal increase in model complexity. This, in turn, shows that explicit gradient-token modeling serves as an effective and lightweight complement to Transformer-based recognition pipelines. The analysis of confusion matrices and the assessment of complementary metrics (accuracy, F1, macro AUC) reveal that the residual errors are structured, primarily occurring between inherently similar classes rather than randomly. This suggests that the model learns robust and class-discriminative representations.

Future work will involve replacing the fixed Sobel filtering with adaptive or learnable gradient extraction modules. We will also evaluate the token injection strategy across different backbone networks and in related structure-sensitive tasks, such as species identification, medical imaging, and remote sensing. Additionally, integrating gradient-aware tokens into multimodal or weakly supervised training regimes will be explored to further enhance the model’s robustness and interpretability. We hope that this work will inspire further exploration of explicit low-level structural cues within high-level Transformer representations for fine-grained recognition.

Author Contributions

B.M.: conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, visualization; Z.J.: methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation; J.L. (Junyi Li): Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization and Data curation; J.L. (Jindong Li): writing—review and editing, supervision; P.Z.: writing—review and editing, supervision, funding acquisition. X.S.: resources, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition; B.J.: conceptualization, validation, resources, writing—review and editing, project administration, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Joint Fund of Henan Province Science and Technology R&D Program (245200810007, 225200810117 and 235200810035), the Fundamental Research Fund of Henan Academy of Sciences (20250620007), the Key Research and Development Project of Henan Province (251111210100), Major Science and Technology Special Project of Henan Province (231100210200), the Young Scientists Fund of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (12304240), and the Scientific and Technological Research Project of Henan Academy of Sciences (20252320005, 20252320006).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All code and post-processed data used in this study are publicly available at https://github.com/bingbeu/GATIT (accessed on 26 January 2026). The open-source datasets used for evaluation are publicly accessible at https://github.com/visipedia/inat_comp (iNaturalist 2018, first released in 2018); https://github.com/cyizhuo/Stanford_Cars_dataset (Stanford Cars, first released in 2013); https://data.caltech.edu/records/65de6-vp158 (CUB-200-2011, first released in 2011); and https://dl.allaboutbirds.org/nabirds (NABirds, first released in 2015).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yang, Z.; Luo, T.; Wang, D.; Hu, Z.; Gao, J.; Wang, L. Learning to Navigate for Fine-Grained Classification. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2018: 15th European Conference, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; Proceedings, Part XIV. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 438–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Fu, J.; Zha, Z.J.; Luo, J. Learning deep bilinear transformation for fine-grained image representation. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; pp. 4227–4236. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.C.; Chen, Z.D.; Wang, Y.; Luo, X.; Xu, X.S. Vit-fod: A vision transformer based fine-grained object discriminator. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.12816. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Ke, W.; Li, D.; Liu, J.; Tian, L.; Shan, Y. Dual Cross-Attention Learning for Fine-Grained Visual Categorization and Object Re-Identification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 4682–4692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Han, K.; Guo, J.; Xu, C.; Li, Y.; Xu, C.; Wang, Y. An Image Patch Is a Wave: Phase-Aware Vision MLP. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 10935–10944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Chen, J.N.; Liu, S.; Kortylewski, A.; Yang, C.; Bai, Y.; Wang, C. TransFG: A transformer architecture for fine-grained recognition. In Proceedings of the 36th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 22 February–1 March 2022; Volume 36, pp. 852–860. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Lin, L.; Chen, R.; Wu, Y.; Luo, X. Knowledge-embedded representation learning for fine-grained image recognition. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.00505. [Google Scholar]

- Mac Aodha, O.; Cole, E.; Perona, P. Presence-Only Geographical Priors for Fine-Grained Image Classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Korea, 27–2 November 2019; pp. 9595–9605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Wen, B.; Sun, J.; Yuan, Z. Metaformer: A unified meta framework for fine-grained recognition. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.02751. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Yu, X.; Gao, Y. Feature fusion vision transformer for fine-grained visual categorization. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.02341. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; Chen, T.; Yin, J.; See, S.; Liu, J. Learning Gabor Texture Features for Fine-Grained Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 1621–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, Q.; Jiang, B.; Luo, B.; Tang, J. Multi-Granularity Part Sampling Attention for Fine-Grained Visual Classification. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2024, 33, 4529–4542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; RoyChowdhury, A.; Maji, S. Bilinear CNNs for fine-grained visual recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 1449–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Zhao, X.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, P.; You, X. Hierarchical Bilinear Pooling for Fine-Grained Visual Recognition. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 574–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, A.; Wharton, Z.; Hewage, P.R.P.G.; Bera, A. Context-Aware Attentional Pooling (CAP): For fine-grained visual classification. In Proceedings of the 35th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI), Virtual, 2–9 February 2021; Volume 35, pp. 929–937. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, H.; Bojanowski, P.; Caron, M.; Cord, M.; El-Nouby, A.; Grave, E.; Izacard, G.; Joulin, A.; Synnaeve, G.; Verbeek, J.; et al. Resmlp: Feedforward networks for image classification with data-efficient training. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 45, 5314–5321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Luo, M.; Zhou, P.; Si, C.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, X.; Feng, J.; Yan, S. MetaFormer Is Actually What You Need for Vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 10819–10829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Lu, B.; Wang, F. CausalSR: Structural causal model-driven super-resolution with counterfactual inference. Neurocomputing 2025, 646, 130375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Horn, G.; Mac Aodha, O.; Song, Y.; Cui, Y.; Sun, C.; Shepard, A.; Adam, H.; Perona, P.; Belongie, S. The iNaturalist Species Classification and Detection Dataset. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 8769–8778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Horn, G.; Branson, S.; Farrell, R.; Haber, S.; Barry, J.; Ipeirotis, P.; Perona, P.; Belongie, S. Building a Bird Recognition App and Large Scale Dataset with Citizen Scientists: The Fine Print in Fine-Grained Dataset Collection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wah, C.; Branson, S.; Welinder, P.; Perona, P.; Belongie, S. The Caltech-UCSD Birds-200-2011 Dataset; Technical Report CNS-TR-2011-001; California Institute of Technology: Pasadena, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, J.; Stark, M.; Deng, J.; Fei-Fei, L. 3d object representations for fine-grained categorization. In Proceedings of the IEEE international Conference on Computer Vision Workshops, Sydney, Australia, 1–8 December 2013; pp. 554–561. [Google Scholar]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2019, 32, 8024–8035. [Google Scholar]

- Diederik, K. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, G.; Potetz, B.; Wang, W.; Howard, A.; Song, Y.; Brucher, F.; Leung, T.; Adam, H. Geo-Aware Networks for Fine-Grained Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCV Workshops), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27–28 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Lu, H.; Li, J.; Xie, Y.; Li, T.; Yang, X.; Zhang, L.; Yan, J. Rethinking Classifier Re-Training in Long-Tailed Recognition: Label Over-Smooth Can Balance. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Virtual, 28 April–2 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Han, P.; Ye, C.; Tong, J.; Jiang, C.; Hong, J.; Fang, L.; Li, X. Enhancing Features in Long-tailed Data Using Large Vision Model. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Rome, Italy, 30 June–5 July 2025; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Hong, Y.; Heo, B.; Yun, S.; Choi, J.Y. The majority can help the minority: Context-rich minority oversampling for long-tailed classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 6887–6896. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, J.; Zhong, Z.; Liu, S.; Yu, B.; Jia, J. Parametric contrastive learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 715–724. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, H.; Cord, M.; El-Nouby, A.; Verbeek, J.; Jégou, H. Three things everyone should know about vision transformers. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 497–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Zhong, Z.; Tian, Z.; Liu, S.; Yu, B.; Jia, J. Generalized parametric contrastive learning. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 46, 7463–7474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Huang, X.; Zheng, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, H. MixMAE: Mixed and masked autoencoder for efficient pretraining of hierarchical vision transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 6252–6261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touvron, H.; Cord, M.; Sablayrolles, A.; Synnaeve, G.; Jégou, H. Going deeper with image transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Virtual, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Wang, W.; Zhu, X.; Dai, J.; Qiao, Y. VL-LTR: Learning class-wise visual-linguistic representation for long-tailed visual recognition. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Heo, B.; Han, D. DenseNets reloaded: Paradigm shift beyond ResNets and ViTs. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; pp. 395–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girdhar, R.; Singh, M.; Ravi, N.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Joulin, A.; Misra, I. Omnivore: A single model for many visual modalities. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 16102–16112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Misra, I.; Joulin, A.; Van Der Maaten, L. Revisiting weakly supervised pre-training of visual perception models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Chen, X.; Xie, S.; Li, Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Masked autoencoders are scalable vision learners. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 16000–16009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryali, C.; Hu, Y.T.; Bolya, D.; Wei, C.; Fan, H.; Huang, P.Y.; Aggarwal, V.; Chowdhury, A.; Poursaeed, O.; Hoffman, J.; et al. Hiera: A hierarchical vision transformer without the bells-and-whistles. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; pp. 29441–29454. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q.; Wang, J.; Jiang, B.; Luo, B. Fine-grained visual classification via internal ensemble learning transformer. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2023, 25, 9015–9028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, X.; Tian, Y. Part-guided relational transformers for fine-grained visual recognition. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 30, 9470–9481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, K.; Xu, Y.; Tian, Y. Fine-grained object classification via self-supervised pose alignment. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 7399–7408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Chen, G.; Lu, J.; Zhou, J. Counterfactual attention learning for fine-grained visual categorization and re-identification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Virtual, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 1025–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, A.; Athitsos, V. Domain adaptive transfer learning on visual attention aware data augmentation for fine-grained visual categorization. In Proceedings of the 15th International Symposium on Visual Computing (ISVC), San Diego, CA, USA, 5–7 October 2020; pp. 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, C.; Bai, H.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, Y. Cross-part learning for fine-grained image classification. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 31, 748–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, C.; Deng, Y.; Xie, B.; Liu, T.; Li, Y.F. TransIFC: Invariant cues-aware feature concentration learning for efficient fine-grained bird image classification. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2023, 25, 11894–11907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Yang, S.; Ding, W.; Liu, R.; Xin, W.; Liu, X.; Miao, Q. Learning multi-scale attention network for fine-grained visual classification. J. Inf. Intell. 2025, 3, 492–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Nam, J.; Ko, B.C. ViT-Net: Interpretable vision transformers with neural tree decoder. In Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Baltimore, MD, USA, 17–23 July 2022; pp. 11162–11172. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.; He, X.; Peng, Y. Sim-Trans: Structure information modeling transformer for fine-grained visual categorization. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia (ACM MM), Lisbon, Portugal, 10–14 October 2022; pp. 5853–5861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Tang, H.; Gao, J.; Du, X.; He, S.; Li, Z. Delving into multimodal prompting for fine-grained visual classification. In Proceedings of the 38th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 23–27 February 2024; Volume 38, pp. 2570–2578. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.C.; Chen, Z.D.; Wang, Y.; Luo, X.; Xu, X.S. A vision transformer for fine-grained classification by reducing noise and enhancing discriminative information. Pattern Recognit. 2024, 145, 109979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, S.; Li, S.; Zheng, H. Fine-Grained Visual Classification via Adaptive Attention Quantization Transformer. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Q.; Zhou, B.; Ji, W.; Xia, G.S. Universal Fine-Grained Visual Categorization by Concept Guided Learning. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2025, 34, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yan, K.; Huang, F.; Li, J. Graph-based high-order relation discovery for fine-grained recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Virtual, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 15079–15088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, P.; Wang, Y.; Qiao, Y. Learning attentive pairwise interaction for fine-grained classification. In Proceedings of the 34th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI), New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; Volume 34, pp. 13130–13137. [Google Scholar]

- Du, R.; Xie, J.; Ma, Z.; Chang, D.; Song, Y.Z.; Guo, J. Progressive learning of category-consistent multi-granularity features for fine-grained visual classification. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 44, 9521–9535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, X.; Cai, Y.; Chen, B.; Liu, H.; Guo, W. Granularity-aware distillation and structure modeling region proposal network for fine-grained image classification. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 137, 109305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Hong, Q.; Yan, Y.; Li, J. LDH-ViT: Fine-grained visual classification through local concealment and feature selection. Pattern Recognit. 2025, 161, 111224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Miao, Q.; Zhao, P.; Li, C.; Li, X.; Feng, G.; Liu, R. Exploration of class center for fine-grained visual classification. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 34, 9954–9966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.