Abstract

This study focuses on modeling and dynamic identification of a reflux condenser in a batch reactor system. The model uses data from real industrial conditions, along with the Volterra series and Genocchi orthogonal polynomials, to capture the condenser’s nonlinear behavior. Identifying the dynamic behavior of the reflux condenser is essential for the safe and efficient production of phenolic resole resin in batch reactors. The condenser plays a key role in controlling the process temperature during exothermic polymerization by cooling and returning reflux material to the reactor. The model was validated with data from a 3500 kg industrial reactor, achieving a thermal energy prediction error of less than 2.5% during the critical polymerization phase. The results show that the model accurately reflects the condenser’s behavior, supporting its application in advanced control strategies for monitoring and regulating process temperature. Using these strategies can prevent uncontrolled reactions and improve operational safety and the quality of resole phenolic resin production.

1. Introduction

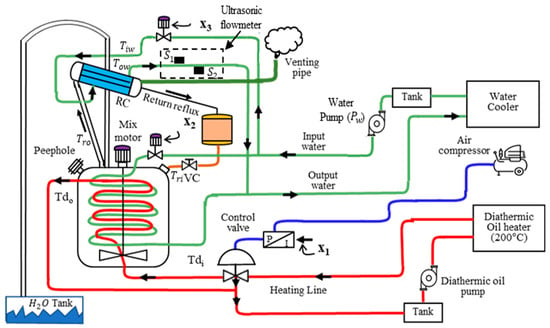

The synthesis of resole-type phenolic resins, through the polymerization of phenol and formaldehyde in an alkaline medium, is a vital process in the chemical industry. The process starts by heating the reactants from room temperature to 65–67 °C using a diathermic oil heating jacket (190–200 °C), controlled by signal X1 as viewed in Figure 1. It features high exothermicity and requires precise thermal control. In industrial practice, reagents—phenol, paraformaldehyde, water, and caustic soda (adjusted to a pH of 9.2)—are loaded into a batch reactor. They are initially heated to 65–67 °C to overcome the activation energy. From this temperature up to 99 °C, a cooling jacket prevents steep temperature gradients. Once polymerization begins, the process becomes highly exothermic, requiring careful management to avoid overheating and uncontrolled reactions. Modern reactors include an internal cooling jacket that circulates water, controlled by signal X2, to gradually heat the reactants to the optimal polymerization temperature within the ideal range of 100–102 °C [1], for which a reflux condenser is used. This condenser cools vapors (a mixture of water, phenol, and formaldehyde) to 40–50 °C and returns them to the reactor, maintaining isothermal conditions and preventing toxic gas emissions if the temperature exceeds 103.5 °C [2,3,4].

Figure 1.

Shows the phenolic resin production process, where the control valve manages the heating of the reactants to 65–67 °C (red line). Pump supplies water to the reflux condenser, which cools the reflux material, and to the cooling jacket (green line), which controls the heating rate and cools the resin. Tiw and Tow are the inlet and outlet temperatures of the RC, along with the flow rates detected by and , which together provide the RC energy readings. The blue line is air compressed. The arrows indicate the direction of flow.

This study presents Angelo Genocchi polynomials as a little-explored but valuable mathematical tool for identifying nonlinear systems, complementing traditional frameworks such as Laguerre, Hermite, and Legendre. Their implementation demonstrates that a reduced basis of orthogonal polynomials can efficiently represent Volterra series kernels, improving the identification of highly nonlinear systems. This allows for capturing complex dynamics and abrupt transients with greater flexibility and accuracy, offering an innovative and robust alternative for modeling industrial systems.

1.1. Research Gap and Contribution

Although the reflux condenser is critical for maintaining thermal stability, current studies are limited to linear models or empirical methods like neural networks, which require large datasets, such as those in [5,6], and often rely on linear approximations or steady-state assumptions, which fail to capture the system’s complex behavior. This work addresses that gap by proposing a dynamic model based on the second-order Volterra series, with kernels expressed using orthogonal Genocchi polynomials [7]. This approach was selected because it

- Represents the condenser’s nonlinearities and time variability without demanding excessive computational resources.

- Combines real-world production data with a rigorous theoretical framework, achieving errors below 2% during the key polymerization phase (30–90 min).

- Lays the foundation for advanced control strategies that improve product stability, safety, and quality.

1.2. Industrial Relevance and Practical Application

This model’s development holds particular relevance in industrial settings like the one described, where precise reflux control is crucial for the following:

- Harnessing the exothermic energy to optimize energy efficiency.

- Releasing excess energy in a controlled manner to prevent toxic emissions and ensure safety.

- Overcoming the limitations of traditional methods that are ill-suited for the process’s dynamic and nonlinear conditions.

Based on experience managing batch reactors, this study examines reflux condenser behavior and provides practical tools to optimize similar industrial processes, where the risk of uncontrolled reactions is ever-present. The validated methodology shows that it is possible to blend theoretical rigor with practical use, opening new opportunities for ongoing improvement in phenolic resin production.

1.3. Comparison with a Recent Study Identified a Nonlinear Process Using Volterra Series

The study exposed in [8] reveals significant differences between the traditional Volterra series and the Volterra series with function-based kernels. In this sense, the work employs a Volterra series model with 22 coefficients, optimized for the nonlinear calibration of amplifiers in electronic systems, where noise and harmonic distortion require high accuracy and a 3000-point data horizon. While effective for subtle distortions, this method demands greater computational effort. In contrast, the proposed model—whose Volterra kernels are represented by orthogonal polynomials—captures complex dynamics with only eight parameters, demonstrating its efficiency and robustness. This approach is promising for industrial systems with highly nonlinear dynamics and sudden transients, such as the reflux condenser in phenolic resin manufacturing.

2. Phenolic Resin, Materials, Basic Principles in Resin Production Materials and Methods

2.1. Phenolic Resin

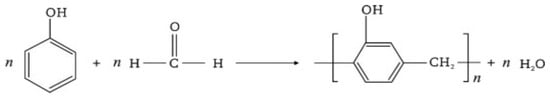

Phenolic resin is a compound resulting from the reaction of phenol with excess formaldehyde in an alkaline environment [9]. The chemical process is shown in Figure 2 aligns with the chemical reaction for phenolic resin described in Equation (1) [10].

Figure 2.

Scheme of the reactions in the synthesis of resole-type phenolic resin: first, phenol methylation in an alkaline medium with excess formaldehyde, followed by a condensation reaction between methylol groups, forming methylene bonds and releasing water, which promotes polymer chain growth.

Phenolic resin synthesis is a complex chemical reaction with water loss [11], known as condensation. In this reaction, the activation energy depends on the catalyst concentration [12]. Therefore, a catalyst concentration that results in an average pH index 9.2 is used to improve phenolic resin manufacturing efficiency. Under these conditions, the reactants are heated by diathermic oil through a heating jacket to approximately 65–67 °C to overcome the activation energy, about 47 .

After the external heating phase, no additional external thermal energy is required for the following three phases, as the exothermic process supplies it, making the manufacturing process more efficient. Furthermore, it is crucial to note that during polymerization, the reactor temperature must be maintained between 100 and 102 °C to prevent runaway reactions; therefore, excess thermal energy must be removed using the reflux condenser.

2.2. Materials and Equipment

The identification of RC dynamics was conducted using data collected from the process selected as a production pattern within several phenolic resin batch production processes, utilizing the following materials and equipment:

- A 3500 kg capacity (IMPLA, Udine, Italy) batch reactor equipped with external heating jackets, internal cooling jackets, a motorized stirrer, and a heat exchanger with a venting pipe in the reflux line.

- The raw materials for each batch include 800 L of water, 1 200 kg of phenol (90% w/w, Feno Resinas S.A de C.V., Tizayuca, Mexico), charged by vacuum pump, 700 kg of paraformaldehyde (92% w/w, ERCROS S.A., Barcelona, Spain), and finally, 7 kg of caustic soda (98% w/w, Quimpac, Callao, Peru) diluted in 20 L of water, which is added so that the reaction reaches in an average pH index 9.2.

- A programmable logic controller (PLC LOGO SIEMENS, Lima, Peru) with a data logger to record the reactor and heat exchanger cooling water temperatures. The PLC supports a SIM card and stores data in CSV format, accessible via the Ethernet port. The sampling time was set to 10 s to ensure accurate readings and a good signal-to-noise ratio. The PLC has been programmed for start and stop functions.

- The Pt100 sensors operate in AM2RTD expansion modules connected to a Siemens LOGO 12-24 RCE VDC 8E4S PLC. They are calibrated with the PLC running, using a diathermal oil bath and a laboratory-grade standard thermometer with an accuracy of approximately 1%. Table 1 shows the locations of the RTDs used in the process, as well as the temperature ranges and working temperature of each one.

Table 1. Location of the Pt100s in the process, as well as the operating temperatures.

Table 1. Location of the Pt100s in the process, as well as the operating temperatures. - Ultrasonic Flo/Heat Meter (F-U2B/DILGER, Dalian, China), with temperature sensors capable of measuring thermal energy, connected to a data logger. The flowmeter must be installed in an area with low mechanical noise, with the ultrasonic transmitter and receiver positioned horizontally—one at the top of the pipe and the other at the bottom—as shown in Figure 1. Additionally, the flowmeter must be calibrated using the pipe’s material, thickness, and diameter data. Fine calibration is achieved by adjusting the sensor spacing to attain a steady-state accuracy of 1%. For this, a dedicated water pump for the reflux condenser, operating at a constant flow rate, is used.

- A computer running MATLAB 2018 software for testing RC model algorithms.

2.3. Basic Principles of Dynamics in Phenolic Resin Production, Resole Type in Batch Reactors

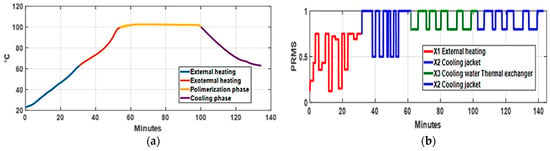

The behavior of an RC used in manufacturing phenolic resins must be modeled based on changes in reactant temperature. Such changes are shown in Figure 3a; the blue line indicates the external heating phase, which ends at 65–67 °C, while the red line represents the self-heating phase, which concludes at 100–102 °C. At this point, the yellow line shows that phenol and formaldehyde begin to polymerize. The excess water boils off, and vapor containing phenol and formaldehyde is pushed into the RC. To achieve the temperature changes of the reagents, the PRMS signals shown in Figure 3b were used.

Figure 3.

Reactor temperature and process PRMS signals: (a) reactor temperature: the blue indicates external heating, the red represents exothermic heating, the orange signifies the exothermic polymerization phase, and the violet shows the cooling phase; (b) PRMS signals the activation of the system valves across all phases of resin manufacturing.

When the reactants’ temperature drops to 99 °C, polymerization is complete (minute 100), but unexpected reactions might occur; to prevent this, the resin is cooled to 40–50 °C, as shown by the green line. Since these tests aim to gather data for RC modeling, the signals controlling the reactor temperature were of the PRMS type, as exposed in [13].

2.3.1. Heating Phase by an External Heat Source

The external heating phase begins at minute 15 and ends at minute 40, during which the temperature reactor (Equation (2)) increases through the flow of diathermic oil , at 220 °C to heat the reactants. The signal controls this flow, which opens a three-way pneumatic valve. The phase starts at room temperature and concludes when the reactants reach the activation energy at 65–67 °C, indicated by the blue trace in Figure 3a. During this phase, only minimal amounts of steam are produced in the reactor. As a result, the gas outlet through the reflux tube is minimal, leading to minimal thermal energy absorption described by Equation (3).

2.3.2. The Self-Heating Phase Due to the Exothermic Energy

This phase starts with the reactants at a temperature of 65–67 °C (shown in Figure 3a), which must be high enough to overcome the activation energy. Then, the exothermic reaction begins. During this stage, signal X2 controls the water flow through the cooling jacket, lowering the temperature gradient until the polymerization temperature reaches 100–102 °C without overheating. As a result, the RC work, which was minimal, increases because the excess water begins to boil, as described by Equation (4).

Consistent with the Arrhenius law [14], the function depends of the temperature due to the energy released by the reaction, where Ci is the molar concentration of the reactants (phenol, formaldehyde, water, and caustic soda), is the activation energy, is the universal gas constant, and is the reactor temperature. In Equation (5) expressed the minimal energy absorbed by the reflux condenser.

2.3.3. The Polymerization Phase and the Cooling Action of Reflux

The polymerization stage forms intermediate resole resins that contain reactive methyl and hydroxyl groups because the resin has not fully polymerized. These products are used to impregnate kraft paper and produce high-pressure laminates. To accomplish this, it is crucial to halt polymerization while the resin remains in a liquid state, before reaching the gel point, so that it can be stored for at least 5 days for use in impregnating kraft paper for the laminate industry [15], among other applications. Additionally, this phase must occur isothermally (Equation (6)), providing energy (Equation (7)) for the reaction while excess heat is removed through cooling in RC. Maintaining resin quality, operational safety, free of genotoxic gases (formaldehyde) [16], relies on effective reflux condenser control.

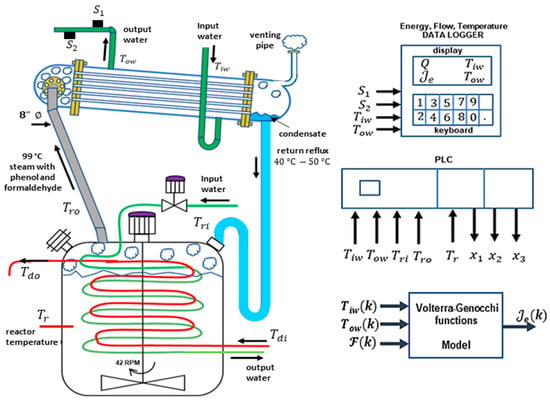

The RC acts as a cooling device, condensing reflux material and returning it to the reactor at 40–50 °C, as shown in green pipe in Figure 4. Using previous criteria, the phase can be expressed as a function involving activation energy , on the Arrhenius law, in addition to the cooling flow , and water temperature differences in RC.

Figure 4.

The schematic of the batch reactor shows the acquisition of flow water rate (green line) data and and temperatures entering the flowmeter, as well as data on the (grey line), (blue line) temperatures of the reflux pipe, and of the reactor. The red line is for external heating. All of this information is necessary for modeling the reflux condenser .

2.3.4. Cooling of the Resin and Distillation of Excess Water

At this stage, the polymerization process is halted before the material gels. To achieve this, the resin must be cooled to a temperature of 40–50 °C by the cooling jacket system to reduce its reactivity and prevent polyphenol changes. The cooling can be described by a function that depends on the flow in the cooling jacket and the valve signal X2, as described by Equation (8).

3. Volterra–Genocchi Functions Identifying Reflux Condenser

3.1. Volterra Series

The dynamics of engineering systems are often nonlinear. An important aspect is that they behave similarly to analytic functions. This supports the idea that all such dynamics can be approximated by mathematical functions, as exposed in [17]. Based on the previous criteria, the identification of is feasible using the Volterra series with a truncated horizon and degree. The proposal is founded on Karl Weierstrass’s approximation theorem [18], as follows:

Theorem 1.

Given a function continuous and an arbitrary , there is an algebraic polynomial as expressed in Equation (9).

The response of the model that expresses the system, by a Volterra series in continuous time [19], will be turned into discrete time of infinite degree, , corresponding to the sum of the endless contributions that act on the delayed inputs . Then, a nonlinear system with infinite degree and infinite horizon is described by Equation (10).

where are the output and input variables, and the kernel of the Volterra series.

Considering that (Equation (11)) corresponds to a causal and stable system, the convolutions is described by (Equation (12)) can be approximated using a Volterra series of degree and a maximum prediction horizon ; an acceptable expression should represent the system within an allowable error as exposed in [20].

3.2. The Genocchi Polynomials

Genocchi polynomials are not solutions to ordinary differential equations (ODEs). They algebraically relate a polynomial of order to the derivative of an polynomial.

3.2.1. Criteria to Generate the Genocchi Polynomials

The Genocchi polynomials are consistent with a type of Appell sequence [21,22], in which the polynomial and its derivative are related as described by Equation (13).

Additionally, a generating function (Equation (14)) must be used to obtain the Genocchi polynomials, which must satisfy the Appel condition.

The expression of the polynomials can be obtained by applying the similar criterion for identifying the coefficients of the Taylor series, as described by Equation (15).

On the other hand, it is essential as a verification method to evaluate the polynomials at , as indicated in Equation (16).

3.2.2. The Orthogonalization of the Genocchi Polynomials

Modeling based on approximation theory using the Riesz–Fischer theorem [23] requires an orthogonal basis functions (OBF) [24] to represent the Volterra series kernels and reduce their parameters. The Riesz–Fischer theorem supports the approximation criterion of Volterra series kernels by employing a finite set of orthogonal polynomials. In the case study, 820 first-order and 820 s-order kernels are represented with 8 polynomials. In other words, using only 8 weight factors or parameters simplifies the model. A simpler orthogonalization method for than the Gram–Schmidt process [25] is achieved by combining the Catalan number (Equation (17)) [26], and the shifted Legendre polynomials [27] as explained in Equation (18).

Consequently, the Genocchi orthogonal polynomials in Table 2 can be obtained from Equation (19) [28].

Table 2.

The first seven Genocchi polynomials and its associated orthogonal polynomials .

4. Methodology for Modeling the Reflux Condenser

As a crucial step in the heat exchanger modeling process, data from tests of the entire reactor system are collected, as shown in Figure 4. These tests focus on the thermal behavior of the CR in the industrial reactor, validate the model, and highlight its importance in developing processes with exothermic reactions. In this context, Figure 4 displays the use of ultrasonic flow meters and Pt100 sensors, which enable real-time monitoring of the flow rate , temperature differences , and energy profiles for producing a batch of resole-type phenolic resin.

The reflux condenser and reactor data, combined with previously developed mathematical tools, will support the development of a gray-box model that can accurately describe the heat exchanger’s behavior in reactor systems like the one used in this research. Consequently, the model will help predict the dynamic response of the RC and improve overall control strategies for the batch reactor.

4.1. The Variables to Model the Reflux Condenser

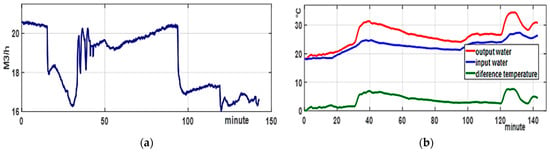

As explained, the RC model is built using Volterra–Genocchi functions along with the main variables in an RC, such as the water flow rate shown in Figure 5a, which is used to cool the exchanger; also, the increase in water temperature during the process cycle, as depicted in Figure 5b, and it is described in Equation (20).

Figure 5.

Model variables: (a) water flow rate for cooling in the reflux condenser; (b) temperature difference between the cooling water inlet and outlet in the RC. Note that the flow changes between 20 and 16 m3/h are due to the exothermic heating phase, during which the slope is smoothed with cooling in the inner jacket, and the cooling phase in the inner jacket at the end of the process.

4.2. Volterra Model of the Reflux Condenser

The significant work of RC begins when the reactants reach the activation energy, especially in the polymerization of phenol with formaldehyde. Equation (21) describes the reaction energy resulting from the exothermic process subtracting the energy extracted by reflux condenser .

The proposed reflux condenser model uses a second-order Volterra series with a maximum prediction horizon of = 820, encompassing all manufacturing process phases. The behavior of throughout the process, supported by Volterra series, can be expressed by Equation (22).

In the previous model, the number of kernels is high. Therefore, it is suggested that it be reduced using Genocchi polynomials.

4.3. Convergent Approximation of Volterra Series Kernels with Genocchi Polynomials

To decrease the number of parameters in the Volterra model, the kernels are expressed using Genocchi polynomials. This approach is based on a summarized version of the Riesz–Fischer theorem, which states that in every infinite-dimensional separable Hilbert space , there exists an orthonormal basis , onto which the kernels can be projected. However, to reduce the number of parameters, the orthogonal basis can be of finite dimension ; consequently, the kernels will approximate with an acceptable error, as described in Equation (23).

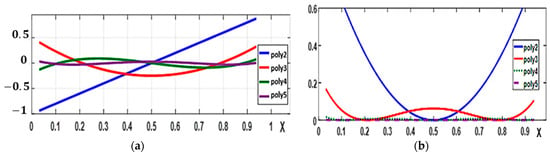

Additionally, a function (OBF) built with polynomials is used to represent the first-order kernels, as shown in Figure 6a and described by Equation (24).

Figure 6.

OBF Genocchi Polynomials: (a) first-order polynomials; (b) first polynomials squared.

Based on orthogonality criteria described in Equation (25), the simplified second-order kernels are represented by an orthogonal basis function (OBF) as described in Equation (26). The basis used in this model is shown in Figure 6b.

4.4. Volterra–Genocchi Second-Order Model of the Reflux Condenser

Based on the criteria above, the proposed model for the energy absorbed by the reflux condenser uses a second-order Volterra series and a maximum prediction horizon = 820, along with an OBF consisting of orthogonal Genocchi polynomials. The model is primarily focused on the polymerization phase. However, all stages of the process were understood with reasonable accuracy. Modeling the complete dynamics of the reflux condenser within the reactor system will provide tools for implementing reactor temperature control strategies. From Equations (24) and (26), the model is described by Equation (27).

In the model, (Equation (28)) is the energy absorbed by the RC; and are the model’s responses in its linear, and second-order modes, and is the identification error. Note that depends on the flow rate within the RC and the temperature differences between the cooling water inlet and outlet.

To simplify the expressions, the matrices describing the process over the entire work horizon are expressed using the variable instead of in Equations (29)–(31).

In the matrix, the column space equals and must match the number of weightings factors of the OBF. The number of rows, , must correspond to the entries in the matrix shown in Equation (32).

In Equation (32), the values of (∙) correspond to the response of the nonlinear system, and the values of involve the product of the polynomials with the model variables, . Moreover, the entries of are in accordance with the unknown parameters of the model. These parameters are called the model weight factors, which were obtained by minimizing a quadratic cost function using the regularized least squares technique with a factor [29] as described in Equations (33) and (34).

To minimize the identification error , the gradient of must be zero. The solution is (Equation (35)), similar to the Moore–Penrose pseudoinverse of the matrix [30].

where is an identity matrix and is the regularization factor.

Since the nonlinear system has a maximum prediction horizon , and the rank of the matrix is ( 1) and has a rank (), the number of solutions for is equal to . Therefore, a suitable set of entries must be selected from all options to minimize identification errors within the system horizon.

4.5. Parameters That Define the Experimental Model Using Volterra–Genocchi Functions

From Equation (31), it is concluded that the number of valid solutions for the entries of (Equation (34)) ranges between . Therefore, the RC can be reliably modeled accurately using an OBF with Genocchi polynomials to approximate the second-order kernels of the Volterra series.

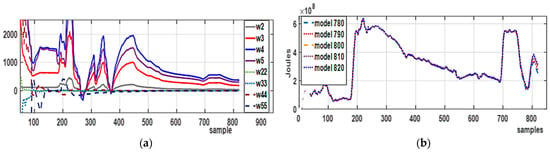

The parameter evolution, shown in Figure 7a, illustrates the dynamic changes in the process. Among these, those from sample 780 were selected, as shown in Table 3. A prediction horizon of about 5% within the working horizon was also achieved. Figure 7b demonstrates that the models exhibit convergent approximation, as seen in models 780 to 820. The result is a reliable model built with 820 samples that closely approximates a nonlinear function expressed with eight parameters, and , instead of the 1640 parameters required by the Volterra series.

Figure 7.

Parameters and model response. (a) Evolution of the parameters that weigh the OBF for first- and second-order polynomials throughout the working horizon; (b) models ranging from sample 780 to 820 to test the uniform convergence of the proposed model.

Table 3.

Weights of the Genocchi polynomials of the model.

4.6. Methodology for Data Acquisition and Model Identification of the Reflux Condenser

4.6.1. Preliminary Steps for Processing a Batch of Phenolic Resin and Data Collection

Verify that the diathermal oil heater is at 200 °C with valve X1 closed. Turn on the agitator motor, reflux condenser water pump, valve X3, and the air compressor.

Add water, paraformaldehyde, ensuring phenol is added using a vacuum pump, and finally caustic soda to reach a pH of 9.2. Set the ultrasonic sensors ( and ) with 10 s sampling intervals and the Pt100 sensor (, ) on the flowmeter, conditioned to measure flow rate, temperature, and energy. Additionally, set the PLC with a sampling time of 10 s (, , , , and ).

4.6.2. Processing Phenolic Resin Manufacturing

The process begins by activating the heating signal X1, which starts data acquisition from the flow meter and the PLC. The reactor temperature must be constantly monitored. If reaches 67 °C and the activation energy is exceeded, the pneumatic heating valve closes, X1 returns to zero, and the airflow is shut off. Ensure that the X2 signal operates between 67 °C and 99 °C.

When reaches 99 °C, verify that X2 is deactivated, X3 is activated, and is between 40 and 50 °C (check the flow rate and temperatures on the flow meter). When is between 100 and 102 °C, verify the behavior of the temperatures , , , and to ensure that the polymerization remains isothermal.

If reaches 99.5 °C, polymerization is complete. In this case, the reflux material is excess water and should not be returned to the reactor; instead, it is stored in a service tank for future processes. Valve X2 is opened to cool the resin to 40–50 °C to prevent sudden reactions. At this point, the process is ending.

4.6.3. Data Download

The flow rate, energy absorbed by the reflux exchanger, , and data are obtained from the flow meter, while the , , , , and data are collected from the PLC, ensuring that samples are taken at very close intervals. The data is then loaded into an Excel file and graphed to verify continuity and to ensure that any unexpected values are within an acceptable range. If the noise is not significant, the data is considered suitable for modeling; any present noise will be used to test the model’s robustness.

4.6.4. Model Selection

The second-order Volterra series is used to model the nonlinearities. By approximating its kernels with an orthogonal basis, the system’s nonlinear characteristics are captured accurately, and the number of parameters needed in the Volterra model is reduced. The integral data of the process within the working horizon must be included; in our case, .

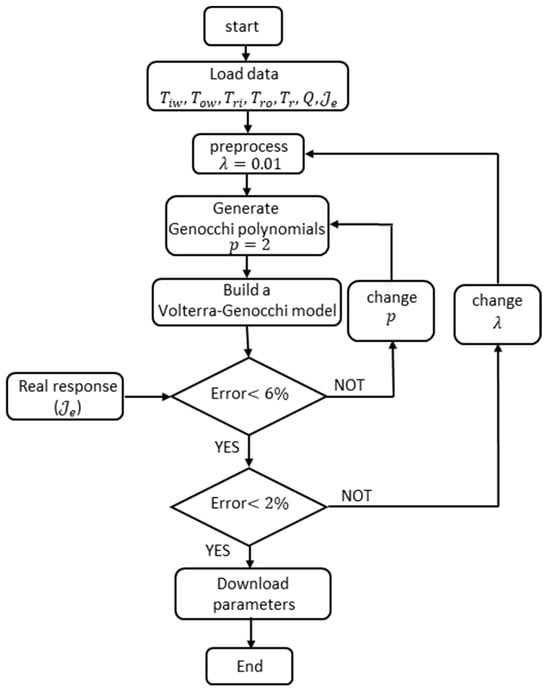

4.6.5. Flowchart for Extracting the Model Parameters

Figure 8 shows how to obtain the parameters for the second-order Volterra–Genocchi model. It also shows how to adjust the number of polynomials needed by the model and how to tune the regularization factor to enhance the stability of the model parameters.

Figure 8.

The figure shows the flow diagram for obtaining the parameters of the Volterra-Genocchi model using energy data, flow rate, and temperatures at the inlet and outlet of the cooling water in the reflux condenser for the phenolic resin manufacturing process.

5. Tests and Results

The results of modeling the reflux condenser using process data from the reactor system and the Volterra–Genocchi functions, as described in Equations (36) and (37), demonstrate the robustness of the model, even with noisy signals such as flow rate and energy during the reactor process that produces resole-type phenolic resin.

Figure 7a shows how the model parameters change over time. Initially, during external heating of samples 0 to 100, the parameters do not stabilize. Subsequently, from sample 100 to 200, some stability is observed because the system operates with exothermic energy, which is smoothed by cooling the materials using the cooling jacket. Between 360 and 750, the system reaches stability because polymerization has practically stopped. The parameters indicate that most of the nonlinearity is captured by first-order polynomials, while fine-tuning is achieved with second-order polynomials.

Figure 7b shows five models of the reflow condenser that demonstrate the convergent approximation characteristic.

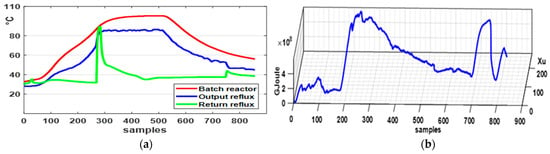

In Figure 9a, the results show that the reactor temperature, indicated by the red line, is closely related to the dynamics of the reflux condenser, which cools the reflux material, indicated by the blue line, and returns it to the reactor at the temperature shown by the green line. Additionally, it is noteworthy that, despite exothermic energy gradients exceeding 20%, as shown in Figure 9b, the polymerization temperature in the reactor remains isothermal.

Figure 9.

Results for a typical phenolic resin process using RC: (a) the temperatures shown by the red line correspond to the batch reactor, the blue line to the outlet of the reflux material sampled every 10 s, and the green line to the return reflux material entering the reactor; (b) the energy absorbed by the RC during whole process of the reflux material, sampled every 10 s.

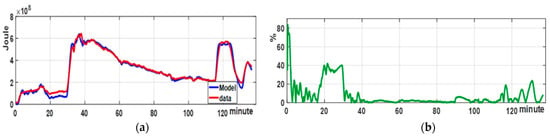

Figure 10a shows the energy evolution in the reflux condenser (red line), manufacturing phenolic resin, compared to the experimental Volterra–Genocchi model (blue line). The model of thermal energy (Equation (36)) matches the flow rate measurements, cooling water temperature differences, and the values of the on (Table 3), which assign weights to the polynomials representing the Volterra kernels.

Figure 10.

Results of the reflow condenser modeling using the Volterra–Genocchi model: (a) RC model behavior compared to test data during phenolic resin production; (b) relative percentage error of the RC model behavior with respect to production data. It is worth noting that the error stays below 2.5% during the polymerization phase, which is important for defining resin quality and the system’s operational safety.

Figure 10b displays the model percentage relative error; however, the error during the heating phase (from 0 to 30 min) is not representative of the polymerization phase, since the reflux condenser performs minimal work due to the limited steam in the reactor. Nonetheless, the reactor performs significant work between 30 and 125 min. Additionally, it should be noted that the error in the cooling phase increases because the return material is water and does not enter the reactor to prevent resin dilution. Additionally, to better understand the model’s success in capturing the dynamics of the RC, we include a table of error metrics.

In Table 4, it is helpful to clarify the following:

Table 4.

Metrics for modeling a reflux condenser using the Volterra–Genocchi model.

- MAE and RMSE: Both are lower in the polymerization zone, indicating that the model fits better during this critical period.

- NMSE: Low values in both cases demonstrate that the model effectively captures most of the reflux condenser dynamics.

- NMRSE: Although slightly higher in the polymerization phase, this is due to the smaller data range in that interval, not a decline in the model’s quality. The lower RMSE and MAE confirm that the model is more accurate in this phase. Overall, the model shows excellent performance, in the polymerization phase.

Finally, the simulation and modeling results of the RC used in the exothermic process, mainly to regulate the temperature of the reactants during polymerization, show that the model is a promising tool as a control variable for polymerizing phenol and formaldehyde, helping prevent harmful formaldehyde emissions [9] through the venting pipe. Additionally, proper operation of the RC ensures it remains free of runaway reactions.

6. Discussion

The polymerization of phenol and formaldehyde involves complex reaction kinetics, and the pH-dependent rate constants complicate modeling, as measuring concentrations and pH takes 5 min, hindering reactor control. Then, the proposed model is justified because it does not require concentration or pH measurements and is faster to control.

The process becomes even more complex under basic conditions, when short, highly branched molecules called resoles are formed. The danger lies in exceeding the polymerization temperature of 5 °C, as this increases the risk of uncontrolled reactions. In such cases, the material can explode or solidify within the reactor, releasing genotoxic gases.

Therefore, mathematical modeling of RC, based on experimental data, is crucial for controlling polymerization processes at 100–102 °C. This method, in operational terms, works better than the Zavitsas model [31], developed to predict the behavior of the reaction between phenol and formaldehyde under NaOH catalysis. The Zavitsas model was designed to predict resole formation over a temperature range of 30–70 °C.

6.1. Model Variables

The proposed model considers the energy absorbed by the cooling water as the dependent variable, with the flow rate through the reactor and the temperature difference between the inlet and outlet of the cooling water as independent variables. This model uses Genocchi polynomials to model the nonlinearities in the Volterra series kernels.

The batch reactor signals used as variables are influenced by noise and unexpected values. Using these signal types helps ensure the model is robust and can function under typical conditions in industrial facilities.

A pending task is to verify the formaldehyde pollution index to ensure emissions are within the range of the Short-Term Exposure Level (STEL) and Time-Weighted Average (TWA) indices around the processes. Although the resulting model is relevant, it would also be important to include energy loss due to environmental effects and radiation at the reactor surface, along with the influence of water hardness, as variables to improve the model’s accuracy.

6.2. Model Validation

The Volterra–Genocchi model is notable for its energy efficiency and thermal stability because the reflux condenser acts as an active control element. Unlike the automation approach [32], which requires continuous external heating and cooling with large temperature swings (90–94 °C), our model uses the exothermic energy of the reaction, limiting the initial heating to 67 °C.

Additionally, when comparing the Volterra–Genocchi model to the patent proposal mentioned in patent [33], which relies on chemical initiators to control polymerization, our method, in contrast, does not require additives, making operation simpler and reducing the risk of instability. Table 5 highlights the key differences between the models.

Table 5.

Comparison of polymerization processes to other batch reactors.

7. Usefulness in Industry and Operational Considerations

Implementing the Volterra–Genocchi model in industrial settings provides significant benefits, especially for managing exothermic reactions. This is especially relevant since the phenolic resin market is expected to reach $24.71 billion by 2033, with a compound annual growth rate of 5.7% starting in 2024 [34].

Previous factors highlight the importance of focusing on process optimization, efficiency, profitability, and operational safety.

7.1. Generalization and Process Safety

The proposed modeling approach is highly adaptable to other exothermic batch systems where reflux cooling serves as the main heat removal method. In the production of resole resin, the reflux condenser functions both as a control device and a safety device.

Failure to remove excess heat during the polymerization phase can cause an uncontrolled reaction, leading to the irreversible solidification of the resin within the reactor and resulting in a catastrophic operational failure. By keeping modeling errors under 2.5%, our model ensures the batch reactor stays within the safe isothermal range (101–102 °C) and avoids reaching the critical gelation point too early or runaway.

7.2. Technical Limitations and Environmental Requirements

Despite its effectiveness, the industrial adoption must consider the following specific hardware and safety restrictions:

- Emissions Control: Since the model is optimized for reflux condensation processes of the material in the reactor, the system must include a vent pipe to release water-phenol-formaldehyde gases, especially when the reflux return temperature is around 70 °C.

- Pollution Mitigation: Because of formaldehyde’s carcinogenic properties, an integrated adsorption system is required to treat venting pipe gases, which increases the complexity of the plant design.

- Operating Range: The model’s high fidelity is designed for temperatures where the mixture’s vapor pressure is sufficient to maintain a constant reflux rate, typically 100 to 104 °C.

8. Conclusions

The model matches the one selected by the resin factory managers, as it produces higher-quality resin and improves operational safety. To ensure manufacturing process consistency, it is essential to trace its trajectory. Therefore, the model, which uses experimental data collected during phenolic resin production, was combined with the Volterra series and Genocchi orthogonal polynomials to characterize its kernels, obtaining a valuable model for identifying the reflux condenser.

In this context, modeling and simulating complex systems with convergent approximations enables an adequate representation of nonlinear dynamics. These criteria confirm the reliability of using experimental data to develop a reflux condenser model. Therefore, it is concluded that the experimental approach, combined with mathematical tools, enables effective modeling of reflux condenser dynamics throughout all phases of resole-type phenolic resin manufacturing, with acceptable error margins.

Regarding scalability, the model can be adapted for larger reactors (up to 20,000 kg) by adjusting the equipment capacity parameters. To scale up, a proportional increase in the heat-extraction rate of the cooling jacket is necessary, from 65 °C to 99 °C, along with a larger reflux condenser capacity to handle the isothermal polymerization phase. The current mathematical approach allows engineers to determine these requirements using energy data already validated in our model’s 3500 kg system.

Furthermore, the model simulated the polymerization process with an error of less than 2.5%, ensuring that the system will not experience runaway reactions and contributing to high-quality production and environmental safety, including reduced formaldehyde emissions. Finally, the tests confirm that the proper functioning of the reflux condenser ensures polymerization in the batch reactor occurs under isothermal conditions, promoting highly repeatable processes as required by the chemical industry in the global market.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M. and R.M.; methodology, C.M. and D.C.; software, C.M. and D.C.; validation, W.R., C.M. and R.P.; formal analysis, R.M.; testing reactor, C.M. and R.P.; investigation, C.M. and W.R.; resources, C.M.; data curation, D.C. and J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.; writing—review and editing, D.C.; visualization, R.P. and J.B.; supervision, C.M.; project administration, C.M.; funding acquisition, W.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería, in accordance with RR-UNI No. 1960-2025, art.6. Cap III. The funding was 2400 CHF ad 3000 PEN.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author, as they were obtained from the resole resin manufacturing processes at PISOPAK PERU SAC facilities, and authorization to publish the data from their processes must be obtained.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank DIGI-UNI and the Faculty of Electrical and Electronic Engineering at the National University of Engineering for their academic support, and PISOPAK PERÚ S.A. for generously providing access to the batch reactor plant facilities during this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MAE | Mean absolute error |

| NMRSE | Normalized root mean square error |

| NMSE | Normalized mean square error |

| OBF | Orthogonal Basis Function |

| pH | Potential hydrogen |

| PLC | Programmable Logic Controller |

| PRMS | Pseudo Random Multi-Level Sequence |

| RMSE | Root mean square error |

| STEL | Short-Term Exposure Level |

| TWA | Time-Weighted Average |

References

- Kamarudin, N.; Biak, D.R.A.; Abidin, Z.Z.; Cardona, F.; Sapuan, S.M. Rheological study of phenol formaldehyde resole resin synthesized for laminate application. Materials 2020, 13, 2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivero, J.C.S.; Heggs, P.J. The re-commissioning of a vent and reflux condensation research facility for vacuum and atmospheric operation. In Advanced Computational Methods in Heat Transfer; WIT Transactions on Engineering Sciences: Southampton, UK, 2006; pp. 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannister, R.N.; Hardwick, F. Phenol Formaldehyde Resins Their Manufacture and Use. U.S. Patent US4132699A, 2 January 1979. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/US4132699A/en (accessed on 18 January 2026).

- Crowl, D.A.; Tipler, S.A. Sizing Pressure-Relief Devices; American Institute of Chemical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 68–76. Available online: https://www.aiche.org/sites/default/files/cep/20131068_r.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2026).

- Vojtesek, J.; Dostal, P. Simulation of adaptive control of continuous stirred tank reactor. Int. J. Simul. Model. 2009, 8, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeykoon, C. Modelling of Heat Exchangers with Computational Fluid Dynamics. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Fluid Flow, Heat and Mass Transfer (FFHMT’21), Virtual, 21–23 May 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.M.; Peng, Z.K.; Zhang, W.M.; Meng, G. Volterra-series-based nonlinear system modeling and its engineering applications: A state-of-the-art review. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2017, 87, 340–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centurelli, F.; Monsurr, P.; Scotti, G.; Tommasino, P.; Trifiletti, A. Methods for Model Complexity Reduction for the Nonlinear Calibration of Amplifiers Using Volterra Kernels. Electronics 2022, 11, 3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarudin, N.; Biak, D.R.A.; Abidin, Z.Z.; Cardona, F.; Salit, M.S. Synthesis of Phenol Formaldehyde Resin with Paraformaldehyde and Formalin. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 778, 012024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.P.; Wang, L.T.; Wang, C.J.; Chang, C.M.; Tseng, J.M. Evaluation of thermal hazards in phenol-formaldehyde polymerization. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2017, 49, 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyigue, L.; Kubiangha, E.O. Estimation of Product Yield and Kinetic Parameters of Phenolic- Resin Pre-Polymer Synthesis using Acid and Base as Catalyst. IOSR J. Eng. 2018, 8, 14–25. Available online: https://iosrjen.org/Papers/vol8_issue9/Version-5/C0809051425.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2026).

- Pilato, L. (Ed.) Phenolic Resins: A Century of Progress; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, H.A.; Godfrey, K.R. System identification with multi-level periodic perturbation signals. Control Eng. Pract. 1999, 7, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, B.; Jun, N.; Park, S.; Seok, C.S.; Hong, U.S. A study on the modified Arrhenius equation using the oxygen permeation block model of crosslink structure. Polymers 2019, 11, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thébault, M.; Kandelbauer, A.; Eicher, I.; Geyer, B.; Zikulnig-Rusch, E. Properties data of phenolic resins synthetized for the impregnation of saturating Kraft paper. Data Brief 2018, 20, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, S.; Ladeira, C.; Nunes, C.; Malta-Vacas, J.; Gomes, M.; Brito, M.; Mendonca, P.; Prista, J. Genotoxic effects in occupational exposure to formaldehyde: A study in anatomy and pathology laboratories and formaldehyde-resins production. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2010, 5, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, S.; Chua, L.O.; Desoer, C.A. Analytical foundations of volterra series. IMA J. Math. Control Inf. 1984, 1, 243–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, D.; Quintana, Y. A survey on the Weierstrass approximation theorem. arXiv 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voscoboynikov, Y.; Solodusha, S.; Markova, E.; Antipina, E.; Boeva, V. Identification of Quadratic Volterra Polynomials in the ‘Input–Output’ Models of Nonlinear Systems. Mathematics 2022, 10, 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libera, A.D.; Carli, R.; Pillonetto, G. A novel multiplicative polynomial kernel for volterra series identification. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2020, 53, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas, L.M.; Ruiz, F.J.; Varona, J.L. Appell polynomials as values of special functions. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2018, 459, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dere, R.; Simsek, Y. Genocchi polynomials associated with the Umbral algebra. Appl. Math. Comput. 2011, 218, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brive, B.; Finet, C.; Tkebuchava, G.E. A generalization of the Riesz-Fischer theorem and linear summability methods. J. Approx. Theory 2012, 164, 841–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassouna, S.; Ouvrard, R.; Coirault, P.; Bibes, G. Estimating volterra kernels expanded on orthonormal bases. In Proceedings of the 2001 European Control Conference (ECC), Porto, Portugal, 4–7 September 2001; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 1846–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casazza, P.G.; Kutyniok, G. A generalization of Gram-Schmidt orthogonalization generating all Parseval frames. Adv. Comput. Math. 2007, 27, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, S. An Introduction to Catalan Numbers; Birkhäuser Cham: Basel, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, R.; Heydari, A.; Bagherzadeh, A.S. Using shifted Legendre orthonormal polynomials for solving fractional optimal control problems. Iran. J. Numer. Anal. Optim. 2022, 12, 513–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phang, C.; Isah, A.; Toh, Y.T. Poly-genocchi polynomials and its applications. AIMS Math. 2021, 6, 8221–8238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libera, A.D.; Carli, R.; Pillonetto, G. Kernel-based methods for Volterra series identification. Automatica 2021, 129, 109686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barata, J.C.A.; Hussein, M.S. The Moore-Penrose Pseudoinverse: A Tutorial Review of the Theory. Braz. J. Phys. 2012, 42, 146–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atthajariyakul, S.; Vanichseni, S. Development of Kinetic Model for Resol Type Phenolic Resin Formation. Thammasat Int. Sc. Tech. 2001, 6, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, A.R.L.; Cruz, S. Propuesta de automatización para el proceso químico de elaboración de un polímero funcional en un reactor discontinuo. Revista Mutis 2023, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westmijze, H.; Meulenbrugge, L.; Vanduffel, K.A.K.; Van Swieten, A.P. Reactor de Polimerización con Mayor Rendimiento por Usar un Sistema Iniciador Específico. Patente ES 2 307 011 T3, 16 November 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Grand View Research, Phenolic Resins Market Size & Share|Industry Report, 2033, 2024. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/phenolic-resins-market (accessed on 18 January 2026).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.