Abstract

The flotation efficiency of magnesite in the slurry system is critically influenced by its surface wettability. In this work, molecular dynamics (MD) and density functional theory (DFT) calculations were employed to investigate the interactions between water molecules and the magnesite (104) surface. To elucidate the underlying mechanisms, systematic evaluations were conducted, encompassing frontier orbital energies, water molecule adsorption behavior, and the water wetting process. Results indicate that electrons readily transfer from the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) of water to the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of magnesite. Specifically, the chemisorption of a single water molecule onto the magnesite surface was observed, with a calculated adsorption energy of −91.6 kJ/mol. This process involves an interaction between the oxygen atom of water and a surface magnesium atom, leading to the formation of an Mg–OW bond. This bond primarily arises from hybridization between the Mg 2p, Mg 2s, and OW 2p orbitals. Furthermore, water molecules within the first adsorbed monolayer exhibited an average adsorption energy of −66.3 kJ/mol, which further confirms the occurrence of chemisorption. Notably, minimal changes were observed in the orbital interactions between water molecules and surface Mg atoms, a trend consistent with the single-molecule adsorption case. The average adsorption energies for the second and third water layers were calculated to be −63.2 kJ/mol and −45.6 kJ/mol, respectively. The stabilization of the hydration layer structure is attributed to the hydrogen-bonding network formed among water molecules in the outer layers. As the number of water layers increases, the structural disorder of water molecules on the magnesite surface progressively intensifies. This decrease in adsorption energy with increasing layer number is attributed to the progressively enhanced contribution of hydrogen-bonding interactions between water molecules across different layers. Consequently, the magnesite surface exhibits a low contact angle, indicating high intrinsic hydrophilicity. Collectively, these findings provide molecular-level insights into the wettability of the magnesite surface, thereby contributing to a more fundamental understanding of magnesite flotation mechanisms.

1. Introduction

Magnesite (MgCO3), a widely occurring and economically significant magnesium carbonate mineral, serves as the primary magnesium resource in China. In natural deposits, it frequently coexists with silicate-, calcium-, and iron-bearing gangue minerals. Froth flotation is the predominant beneficiation method; however, separating magnesite from minerals that share similar anionic (CO32−) and cationic (Ca2+, Mg2+) compositions poses significant challenges, frequently leading to inefficient separation and poor recovery. A prominent example is the difficult separation between magnesite and the calcium-bearing mineral dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2), a critical challenge in the flotation-based purification of Chinese magnesite ores [1]. Studies indicate that both magnesite and dolomite exhibit pronounced surface hydrophilicity and undergo spontaneous hydration even in the absence of flotation reagents [2]. Minerals with stronger hydration tendencies exhibit greater surface hydrophilicity, whereas those with weaker hydration display increased hydrophobicity [3]. Moreover, water molecules within the hydration layers on mineral surfaces exhibit properties distinct from those of bulk water [4]. The presence of such structured hydration layers can impede direct interactions between specific ions or molecules and the mineral surface [5], while simultaneously influencing interparticle interactions within slurry systems [6]. Consequently, through these mechanisms, hydration layers exert a significant influence on mineral flotation behavior. Water adsorption during flotation critically influences separation selectivity and efficiency by modifying mineral surface properties, which in turn regulates flotation reagent effectiveness [7,8,9]. Therefore, a fundamental understanding of the structure and properties of hydration layers on magnesite, and their subsequent impact on flotation behavior, is essential.

A fundamental understanding of mineral surface wettability and hydration mechanisms lies at the core of flotation science [7]. This interaction—a complex interplay of interfacial forces—determines whether mineral particles report to the froth or remain in the pulp. Decoding this intricate behavior requires a multi-faceted experimental approach. For instance, advanced techniques such as atomic force microscopy (AFM) can directly probe nanoscale hydration forces and adhesion [8], whereas contact angle measurements provide macroscopic quantification of wettability. Spectroscopic methods, including X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS), elucidate surface chemistry and reagent adsorption. Vibrational spectroscopies (e.g., FTIR, SFG), conversely, offer insights into the structure and dynamics of interfacial water molecules [9,10,11,12,13]. However, experimental techniques often provide a static, time-averaged picture, failing to capture the transient and dynamic nature of interfacial processes. In this context, molecular dynamics (MD) and density functional theory (DFT) calculations have become indispensable, providing an atomic understanding of hydration layer structure, ion adsorption, and collector-mineral interactions [14,15]. Significant progress has been made in elucidating the electronic structure, wettability, and reagent adsorption mechanisms of various mineral surfaces [16,17].

Computational approaches, notably MD and DFT, have proven effective in providing detailed insights into water adsorption mechanisms and hydration layer properties. When coupled with techniques such as AFM and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), these simulations can characterize hydration layer structure [18]. For example, Li et al. employed DFT to investigate H2O interactions with ZnS and Cu-activated surfaces, analyzing distinct water adsorption modes [19]. Similarly, Ding et al. [20] examined water adsorption on copper mineral surfaces, thereby elucidating the mechanisms underlying their wettability. In the fluorapatite system, molecular simulation studies by Mkhonto and de Leeuw indicated that disordered water adsorption on anisotropic surfaces leads to the formation of distinct hydration layers [21]. In contrast, Zahn et al. analyzed the hydroxyapatite–water interface, revealing an ordered, layered distribution of water molecules—a finding corroborated by subsequent studies [22]. Despite discrepancies among these investigations, they have collectively advanced the theoretical understanding of microscale mineral–water interactions. Subsequent research has shifted focus toward elucidating the structure of mineral hydration layers and their governing factors. For instance, Emmerich et al. [23] reported on the interlayer hydration of Na-montmorillonite, suggesting that sodium ions induce a discontinuous three-layer hydration structure within the interlayer space. Furthermore, solution chemistry—including pH, ion type, and concentration—is recognized as a critical factor governing hydration layer thickness [24]. Notably, the presence of strongly hydrated ions can substantially increase this thickness [25]. Collectively, these studies offer valuable insights into mineral hydration mechanisms that are directly pertinent to flotation separation.

Despite significant advancements in magnesite beneficiation research [26]—particularly in flotation desilication technology—a comprehensive understanding of water adsorption on carbonate mineral surfaces, especially magnesite, remains limited. Most computational studies on magnesite have concentrated on the adsorption and interactions of flotation reagents (e.g., collectors and depressants) [15,27,28,29], offering valuable insights for separation process design. However, a detailed atomic-scale description of the intrinsic (reagent-free) hydration mechanism—which fundamentally governs surface wettability and sets the stage for subsequent reagent adsorption—remains lacking. A predictive understanding of the wettability and hydration of minerals such as magnesite requires an atomic-scale perspective that connects electronic structure, interfacial dynamics, and macroscopic properties. To address this fundamental gap, the present study employs a multi-scale computational approach, combining DFT and MD, to systematically unravel the hydration process of the magnesite (104) surface—from a single water molecule to a structured interfacial water film. This work distinctively shifts the focus from reagent interactions to the inherent mineral–water interface. Building on our previous DFT/MD investigations into collector adsorption on magnesite and dolomite [15,27,28,29], we herein analyze adsorption energies, geometric configurations, differential charge density, partial density of states, and Mulliken populations at the atomic level. Furthermore, by simulating the water wetting process, we connect these microscopic interactions to the macroscopic wettability. This work provides a coherent molecular narrative that directly links orbital interactions and electron transfer to the formation of stable hydration layers and the intrinsically hydrophilic character of magnesite. These findings establish a crucial baseline understanding of the native hydrated interface, which is essential for rationally interpreting and designing the competitive adsorption of flotation reagents in future studies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Structural Optimization of the Magnesite Surface

Magnesite, which belongs to the calcite group, crystallizes in the trigonal system with the rhombic-tripartite system. To facilitate subsequent simulations, the magnesite unit cell was first fully optimized. All calculations were performed using DFT as implemented in the CASTEP module of the Materials Studio 2017 R2 software package (BIOVIA, Dassault Systèmes, Paris, France) [30,31]. Geometry optimization of magnesite was carried out using the Perdew-Wang (PW91) generalized gradient approximation (GGA) functional [30,32,33,34]. The convergence criteria were set as follows: self-consistent field (SCF) tolerance of 2.0 × 10−6 eV/atom, maximum force of 0.5 eV/nm, maximum stress of 0.1 GPa, and maximum atomic displacement of 2.0 × 10−5 nm. An energy convergence criterion of 5.0 × 10−7 eV/atom was also applied. A plane-wave basis set with a kinetic energy cutoff of 450 eV was used. Brillouin zone integration was performed using a 2 × 2 × 2 Monkhorst–Pack k-point grid. A comparison between the experimental and optimized lattice parameters of magnesite is presented in Table 1. Experimental lattice parameters were sourced from the Mindat.org database and literature [35,36], whereas the optimized parameters resulted from the full structural relaxation described above. The optimized magnesite unit cell yielded lattice parameters of a = b = 0.4700 nm, c = 1.5270 nm, and angles α = β = 90°, γ = 120°. These optimized parameters show minimal deviation from the experimental data (a = b = 0.4663 nm, c = 1.5015 nm, α = β = 90°, γ = 120°), with a maximum relative error of 1.69%. This close agreement validates the computational setup for subsequent simulations.

Table 1.

Crystal structure parameters of magnesite.

2.2. Hydration System Optimization

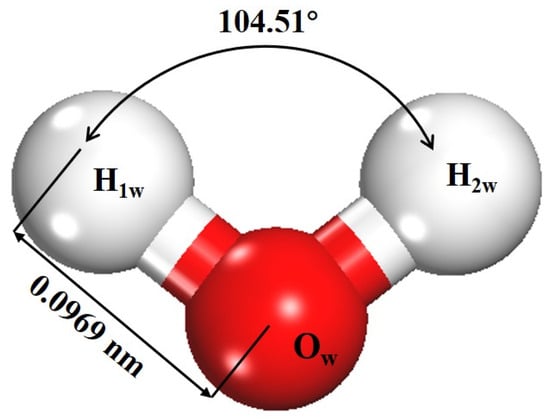

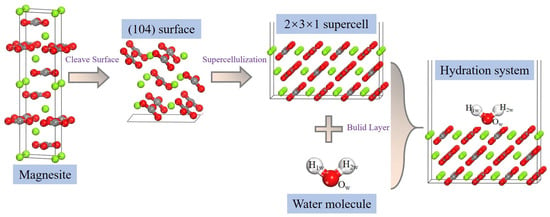

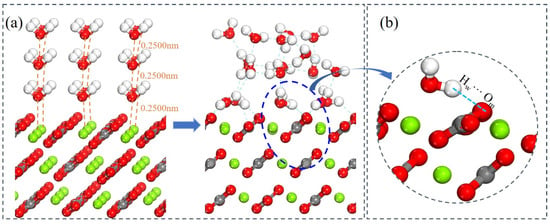

The magnesite (104) surface is widely recognized as the most thermodynamically stable cleavage plane under hydrated conditions [37,38]. Following systematic tests of surface terminations, slab thickness (3 atomic layers), and vacuum size, a 2 × 3 × 1 supercell of the magnesite (104) surface was constructed [39]. A vacuum layer of 2.0 nm was added along the surface normal (z-direction) to eliminate spurious interactions between periodic images of the slab. During optimization, the bottom atomic layer was fixed to represent the bulk substrate, while all upper layers were fully relaxed. Convergence tests confirmed that this slab model reliably describes surface relaxation and adsorption behavior. After optimization, the surface Mg atoms exhibited stable threefold coordination, consistent with previous reports [7,15], confirming their role as the primary reactive sites for water adsorption. An isolated water molecule was also optimized under the same DFT criteria (Figure 1), yielding an O–H bond length of 0.0969 nm and an H–O–H angle of 104.51°, in good agreement with experimental data [40]. Hydration models were then constructed by placing water molecules atop the surface Mg sites (Figure 2). The adsorption energy (ΔEads) for a water molecule was calculated using Equation (1) [41,42]:

where ΔEads is the adsorption energy, Ew/s is the total energy of the water-adsorbed magnesite surface, Ew is the energy of the isolated water molecule(s), and Es is the energy of the clean magnesite surface.

ΔEads = Ew/s − Ew − Es

Figure 1.

Optimized structure of the water molecule (white and red atoms represent H and O, respectively).

Figure 2.

Construction of the magnesite-water interaction system (gray and green atoms represent C and Mg, respectively).

2.3. Water Wetting Simulation

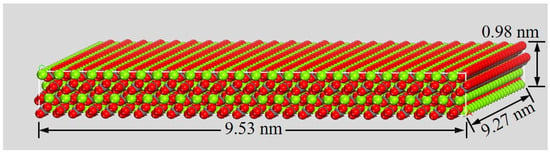

For the water wetting simulations, a larger substrate was created by expanding the optimized (104) surface model into a 4-layer supercell with in-plane dimensions of 18 × 21 unit cells. This yielded a superlattice surface measuring approximately 9.53 × 9.27 × 0.98 nm3 (Figure 3). Subsequently, a spherical water droplet containing 1000 molecules (approximate diameter: 2.0 nm) was constructed using the Amorphous Cell module. This droplet was then placed on the mineral surface substrate using a layer addition method to create the initial wetting model. A vacuum layer of 6.0 nm was retained above the droplet. All MD simulations employed the COMPASS II force field, which has been validated for modeling condensed-phase materials, minerals, and interfacial systems. Non-bonded interactions (van der Waals and electrostatic) were calculated using an atom-based summation method. A cutoff distance of 1.25 nm was applied to van der Waals interactions. Electrostatic interactions were treated using the Ewald summation method with an accuracy of 1.0 × 10−5 kJ/mol [7,15]. Following energy minimization, production MD simulations were performed in the NVT (canonical) ensemble at 298 K, using a Nosé–Hoover method with a coupling constant of 0.1 ps. The equations of motion were integrated using the Velocity Verlet algorithm with a time step of 1.0 fs. Each wetting simulation had a total duration of 500 ps. The first 100 ps were allocated for system equilibration, confirmed by monitoring the stabilization of total energy and droplet conformation. Trajectory data for analysis, including contact angle calculation, were collected from the subsequent 400 ps production run. To ensure statistical reliability and account for stochastic variations in initial droplet placement, three independent simulation trials were conducted.

Figure 3.

A relaxed surface supercell model of magnesite (104) surface.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of Frontier Molecular Orbitals

According to molecular orbital theory, the strength of water-mineral interactions can be quantitatively evaluated by examining the energy levels of their frontier orbitals [39,40]. The frontier molecular orbital energy levels of magnesite were systematically calculated using the Dmol3 module. The bonding nature can be inferred from the wavefunction coefficients of the highest occupied (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied (LUMO) molecular orbitals; the corresponding values are listed in Table 2. A larger absolute value of an atomic orbital wavefunction coefficient indicates a greater contribution of that atom to the corresponding molecular orbital [41]. The O atoms are the primary contributors to the HOMO of magnesite, indicating that they act as potential electron-donating sites. For the LUMO, carbon (C) and magnesium (Mg) atoms are the main contributors, identifying them as electron-accepting sites.

Table 2.

Frontier orbital energy analysis of magnesite.

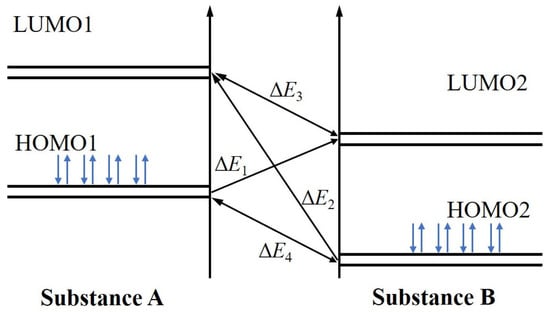

The frontier orbital interaction between two species (e.g., water and magnesite) is schematically illustrated in Figure 4, where the interaction strength is governed by the energy gaps ΔE1 and ΔE2. A smaller energy gap (ΔE) between the HOMO of one species and the LUMO of the other indicates a stronger propensity for electron transfer and interaction [42]. The calculated frontier orbital energy gaps for the water-magnesite system are listed in Table 3. The results show that ΔE1 is smaller than ΔE2. This indicates that electron transfer from the HOMO of water to the LUMO of magnesite is the energetically favored pathway.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of frontier orbital energy level matching between substances A and B (blue arrows represent a pair of spin-opposite electrons occupying the HOMO).

Table 3.

Frontier orbital interaction between magnesite and the water molecular.

3.2. Simulations of the Water Molecule Adsorption

3.2.1. Adsorption of a Single Water Molecule

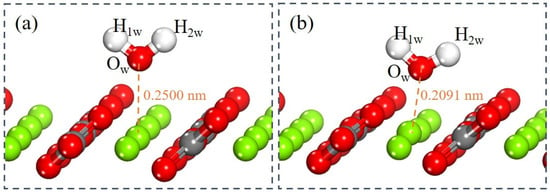

DFT simulations of a single water molecule adsorbed on the magnesite (104) surface were performed to elucidate the fundamental interaction mechanisms. This approach reveals key factors governing wettability and reactivity through calculations of adsorption energy, electron density distribution, and bonding characteristics, thereby establishing a theoretical basis for surface property regulation [28]. To examine the evolution of the hydration layer, water molecules were incrementally added to construct successive monolayers. Following the establishment of the first monolayer, subsequent layers were added to study interlayer connectivity, with the entire system re-optimized at each stage. This methodology allows for the examination of how the surface influence diminishes with increasing hydration layer thickness. Figure 5 illustrates the optimized configuration of a single water molecule before and after adsorption on the magnesite (104) surface. In the initial state (Figure 5a), the water oxygen atom (Ow) was positioned 0.2500 nm from the outermost surface Mg atom. After adsorption (Figure 5b), the Ow atom approaches the Mg atom, resulting in an Mg–Ow bond distance of 0.2091 nm. This distance is slightly less than the sum of the atomic radii of O and Mg (0.2100 nm) [29], suggesting covalent bond formation. The calculated adsorption energy of −91.6 kJ/mol for a single water molecule at the Mg site confirms a thermodynamically favorable and spontaneous process. This strongly negative value significantly exceeds the typical threshold for physisorption (approximately −40 kJ/mol), confirming strong chemisorption involving substantial charge transfer and the formation of a coordinative Mg–Ow bond [43]. Notably, this adsorption energy is more negative than values reported for water on the dolomite (104) surface (ranging from −65 to −80 kJ/mol) [44,45], highlighting a stronger water affinity for the magnesite surface. This energetic discrepancy provides a molecular-scale explanation for the distinct interfacial hydration and flotation responses observed between magnesite and dolomite [43]. These findings provide a molecular-level rationale for flotation strategies, suggesting that effective polar collectors must compete with this strongly bound hydration layer.

Figure 5.

Conformations of a single water molecule on magnesite (104) surface. (a) Before adsorption. (b) After adsorption.

- (1)

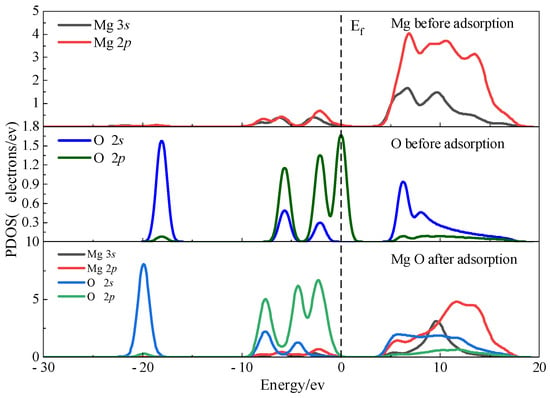

- Partial density of states analysis

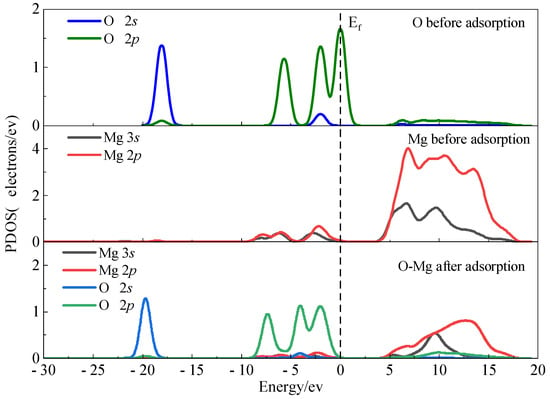

The optimized configuration after single-water-molecule adsorption was analyzed to elucidate the hydration mechanism. Partial density of states (PDOS) analysis, widely used to examine electronic state changes upon adsorption [46], reveals that significant electron transitions localize near the Fermi level (set to 0 eV). As shown in Figure 6, the PDOS of the adsorbed water oxygen (Ow) exhibits a noticeable shift to lower energy, suggesting orbital hybridization with surface Mg states. The Mg 2p states, being core-level orbitals, show minimal contribution to bonding near the Fermi level. These results indicate that water adsorption occurs via specific Ow–Mg interactions. The Ow 2p orbitals stabilize below the Fermi level, generating three distinct peaks between −10 and 0 eV that are more intense than the Mg 2p features. In the energy range of 5–20 eV, the PDOS profiles of the Mg 3s and 2p orbitals show broadening and flattening, suggesting orbital hybridization. Partial overlap between the Mg 2p and Ow 2s orbitals is observed between 0.5 and 17 eV; however, the limited spatial overlap indicates weak orbital coupling.

Figure 6.

PDOS plots before and after adsorption of Ow on the magnesite surface.

- (2)

- Mulliken population analysis

Mulliken population analysis provides quantitative insights into charge transfer, bonding characteristics, and adsorption mechanisms in mineral–water interactions [47,48,49,50]. This method is particularly advantageous for resolving subtle electronic rearrangements at the atomic scale, a regime where traditional experimental techniques face limitations. Table 4 presents the evolution of Mulliken charges and orbital populations during the adsorption of a water molecule at a Mg site. The analysis reveals that the total electron population on the Mg atom remains nearly constant, with a net loss of <0.01 |e|. However, a minor redistribution of electron density between its 3s and 3p orbitals is observed, indicating subtle rehybridization upon adsorption. Conversely, the Ow atom undergoes a significant increase in its negative Mulliken charge (from −1.05 to −1.97 |e|), signifying substantial electron gain. This charge gain is complemented by a population increase of 0.04 in its 2s/2p orbitals. This result is consistent with the formation of a coordinative bond where Ow acts as an electron donor, leading to a net charge transfer from the surface Mg to the Ow atom. The charges on the hydrogen atoms (H1w, H2w) change minimally, confirming that the intramolecular H–O bonds are not fundamentally altered.

Table 4.

Mulliken population analysis of the key atoms at the adsorption interface.

Table 5 summarizes the Mulliken bond populations and bond length evolution during adsorption. The post-adsorption Mg–Ow interaction shows a transition toward more ionic character. The elongated bond length suggests a binding strength weaker than that of bulk Mg–O bonds. The increased ionic character may enhance adsorption stability under specific solution conditions. The Hw–Ow covalent bond in the isolated water molecule has a population of 0.51 and a length of 0.0987 nm. Upon adsorption, the bond population increases to 0.56 and the bond length shortens to 0.0975 nm, reflecting enhanced covalent character due to optimized orbital overlap.

Table 5.

Mulliken bond populations and bond lengths before and after adsorption.

The z-axis displacements of the surface Mg atom and the water molecule (Ow, H1w, H2w) upon adsorption are detailed in Table 6. Positive values denote displacement outward from the surface (away from the bulk), while negative values indicate inward movement. Upon hydration, the surface Mg atom relaxes outward by 0.0176 nm. This outward relaxation is consistent with phenomena observed on hydrated metal oxide surfaces. Conversely, the water molecule displaces inward by 0.0303–0.0526 nm, indicating strong adsorbate-substrate attraction driven by electrostatic complementarity. This coordinated movement highlights the dynamic interplay between surface restructuring and adsorbate accommodation.

Table 6.

Relaxation distances of Ow, H1w, H2w and Mg along z-axis before and after adsorption.

- (3)

- Electrostatic potential analysis

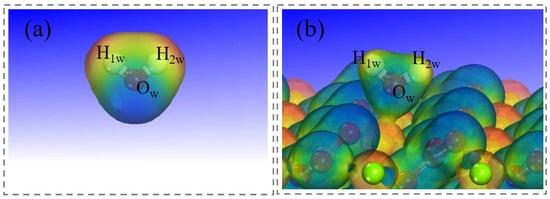

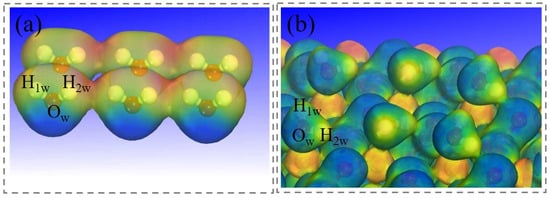

The electrostatic potential distribution of the hydrated magnesite (104) surface was analyzed to clarify interfacial charge behavior. As shown in Figure 7, the electrostatic potential map exhibits distinct spatial polarization. Blue regions (negative potential) concentrate around surface O atoms and the adsorbed water molecule, indicating electron-rich areas. Red regions (positive potential) localize over exposed Mg atoms, reflecting electron-deficient areas. The adsorbed water molecule retains lone electron pairs on its Ow atom, generating a localized negative potential that enhances electrostatic stabilization with adjacent Mg sites.

Figure 7.

Electrostatic potential distribution diagram. (a) An individual water molecule. (b) The single water molecule adsorbed on magnesite.

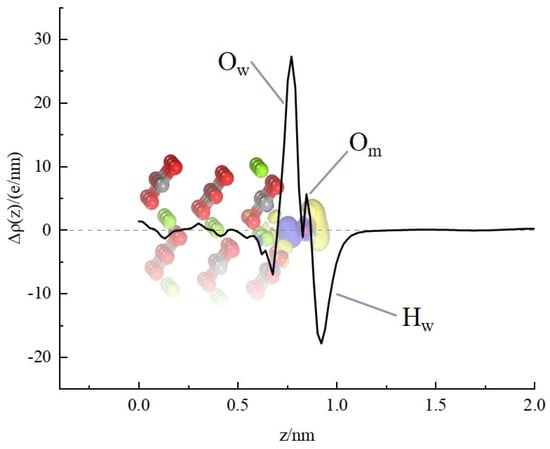

Furthermore, the plane-averaged charge density difference along the surface normal (z-axis, Figure 8) was analyzed to quantify interfacial charge transfer. Charge redistribution normal to the surface is shown, where positive (yellow) and negative (blue) isosurfaces correspond to charge accumulation and depletion, respectively [51]. Significant charge redistribution is localized at the water–magnesite interface. Pronounced charge reorganization is observed at the adsorption site: electron accumulation on the Ow and adjacent lattice oxygen atoms contrasts with depletion at the Hw atoms. These results are consistent with the Mulliken population analysis (Table 5). The atomic-scale evidence for strong, site-specific water chemisorption on Mg sites provides a fundamental explanation for the inherent hydrophilicity of magnesite. Consequently, in the context of flotation, effective collector molecules must compete directly with water for these specific Mg sites. This competition necessitates that collectors possess not only an affinity for Mg but also sufficient energy to displace the tightly bound water molecules.

Figure 8.

Adsorption system plane-averaged charge density gain/loss (blue and yellow regions correspond to charge density accumulation and depletion).

3.2.2. Adsorption of Monolayer Water Molecules

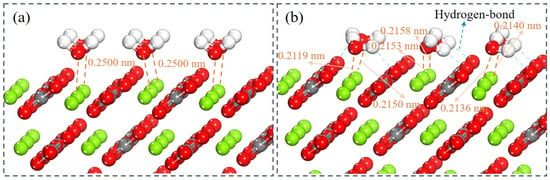

Following the elucidation of the single-molecule adsorption mechanism, simulations of a complete water monolayer are essential for understanding the more complex physicochemical processes at realistic hydrated interfaces [52,53]. To this end, a monolayer adsorption configuration was constructed on the magnesite (104) surface with six water molecules arranged at equidistant Mg sites. The resulting hydrogen-bonding network is illustrated with blue dashed lines in Figure 9. This model employed a subset of six water molecules, rather than occupying all nine available Mg sites on the 2 × 3 surface supercell. This approach was adopted for two reasons. First, three edge sites were excluded to mitigate artifacts from periodic boundary conditions, which could otherwise distort the adsorption energetics. Second, the reduced density prevents steric overcrowding, allowing the water molecules to relax into a stable, hydrogen-bonded network [52,53]. The computed average adsorption energy per water molecule within the monolayer was −66.3 kJ/mol. This value is significantly less negative than that for the single isolated molecule (−91.6 kJ/mol). This reduction in average binding energy implies an attenuated per-molecule binding strength within the monolayer, a consequence of competitive intermolecular interactions among adsorbed water molecules [54].

Figure 9.

State of a layer of water molecules on the surface of magnesite. (a) Before adsorption. (b) After adsorption.

Structural analysis revealed an average Mg–Ow bond distance of 0.2130 nm. The chemisorbed water molecules exhibit characteristic tilting, as the Hw atoms form hydrogen bonds with adjacent surface oxygen atoms. Molecules near the supercell boundaries exhibit a preferential planar orientation, likely due to heterogeneity in adsorption energy mediated by differential hydrogen-bonding environments. As shown in Figure 9, Hw tilt angles are smaller for molecules in central regions compared to those at edge positions. This spatial variation correlates with stronger hydrogen bonding at the periphery. The Hw–Ow bond lengths display spatial dependence upon adsorption: bonds in central regions remain near their original length (0.097 nm), whereas peripheral bonds elongate to 0.1001 nm. This elongation facilitates partial Hw–Ow bond dissociation, promoting surface hydroxylation. The resulting molecular disordering relative to the ideal initial configuration aligns with known interfacial ensemble effects [55].

- (1)

- Partial density of states analysis

PDOS analysis of the interfacial Ow and surface Mg atoms before and after monolayer adsorption (Figure 10) indicates that electronic states near the Fermi level are dominated by Ow 2p and Mg 3s/3p orbitals. In the energy range from approximately −6 to 0 eV, noticeable hybridization occurs between Ow 2p and Mg 3s states, signifying the formation of coordination bonds at the interface. In contrast, the deeper Mg 2p and Ow 2s states, located below −15 eV, remain largely unaffected by adsorption, consistent with their character as core-level orbitals.

Figure 10.

PDOS plots before and after monolayer adsorption of Ow on the magnesite surface.

- (2)

- Mulliken population analysis

Table 7 presents the average Mulliken bond populations and corresponding bond lengths per water molecule within the adsorbed monolayer. The average bond populations for Om–Hw bonds (between water Hw and surface oxygen, Om) and for intermolecular Ow–Hw bonds are negligible. This is attributed to the elongation and weakening of the original Hw–Ow bonds due to hydrogen bond formation. The Mg–Ow bond exhibits an average population of 0.11, confirming its ionic character and its central role in the adsorption bond. In contrast, the intramolecular Hw–Ow bonds retain higher bond populations, reflecting their more covalent nature. However, the elongation of specific Hw–Ow bonds (notably for one hydrogen, H2w) reduces the interatomic force, promoting bond dissociation and hydroxyl (−OH) group formation, thereby facilitating surface hydroxylation.

Table 7.

Average Mulliken bond populations and bond lengths for the adsorbed monolayer.

- (3)

- Electrostatic potential analysis

The electrostatic potential distribution for the adsorbed water monolayer (Figure 11) is consistent with that observed for the single-molecule case. The Hw atoms are electrostatically attracted to surface oxygen atoms, leading to hydrogen bond formation. The negative potential around Ow atoms promotes interaction with surface Mg atoms, enhancing adsorption. Concurrently, this electrostatic environment facilitates Hw–Ow bond dissociation. The electrostatic potential distribution confirms that the attraction between Hw and surface Om atoms drives hydrogen bond formation, which in turn results in Hw–Ow bond elongation and dissociation. This analysis provides a more realistic representation of the hydrated interface than the single-molecule model.

Figure 11.

Electrostatic potential distribution diagram. (a) An individual layer of water molecules. (b) The layer of water molecules adsorbed on magnesite.

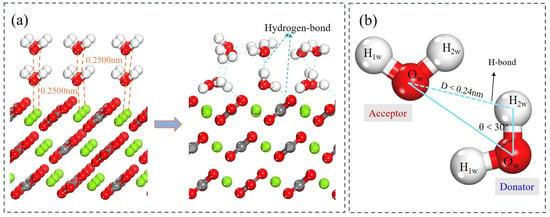

3.2.3. Adsorption of Multilayer Water Molecules

In practical flotation systems, mineral surfaces are invariably covered by multilayer hydration structures. To more accurately simulate the actual hydration environment in flotation, a second and then a third water layer were incrementally introduced onto the established monolayer. This stepwise approach enables a systematic evaluation of how hydration film thickness and structure evolve, which ultimately governs collector adsorption competition and interfacial water dynamics. The optimized structures reveal that the magnesite surface induces ordering in the proximate water layer, but this templating effect rapidly decays with distance from the surface. As additional layers are added, the water molecular arrangement becomes increasingly disordered, approaching the structure of bulk water. The average adsorption energy per water molecule decreases to −63.2 kJ/mol in the bilayer (Figure 12a) and further to −45.6 kJ/mol in the trilayer system (Figure 13a). This progressive decrease confirms that strong chemisorption dominates the first monolayer, while intermolecular hydrogen bonding contributes increasingly to the stability of outer layers.

Figure 12.

(a) Conformations of the bilayer system of water molecules adsorbed on magnesite (104) surface. (b) Schematic diagram of hydrogen bond formation.

Figure 13.

(a) Conformations of the trilayer system of water molecules adsorbed on magnesite (104) surface. (b) Schematic diagram of hydrogen bond formation.

Furthermore, analysis of the z-axis displacements of atoms within the water layers provides insight into the evolving interaction strength between magnesite and successive water layers [56,57]. Hydrogen bonding is a key indicator for analyzing both water–water and water–magnesite interactions. A hydrogen bond was identified using geometric criteria: an O···H distance < 0.2400 nm and an O–H···O angle > 150° (equivalent to a donor angle < 30°) (Figure 12b) [58]. As detailed in Table 8, surface Mg atoms exhibit an outward relaxation (toward the aqueous phase) upon hydration. The magnitude of this displacement is greatest for the bilayer and attenuates with the addition of the third layer. This indicates that the structural rearrangement of the magnesite surface is most sensitive to the first few hydration layers. The Ow atoms of the first monolayer undergo inward relaxation. In contrast, the oxygen atoms of outer water molecules display outward relaxation, driven by hydrogen bonding with the layer beneath. Consequently, while Ow atoms in the second layer form H-bonds with the first layer, the effective bonding force per molecule weakens in the third layer, leading to a reduced average outward displacement.

Table 8.

Relaxation distance along z-axis after adsorption stabilization of each atom in different water molecule layers.

The number and length of hydrogen bonds within the interfacial water network are direct indicators of hydration layer stability and strength [59]. Table 9 summarizes the number and average length of hydrogen bonds within the hydration structures. The total number of hydrogen bonds increases with each added layer, facilitating the formation of an extensive, interconnected hydrogen-bonding network. The first (inner) water layer is primarily involved in chemisorption via direct Mg–Ow bonds, complemented by hydrogen bonds between Hw and surface Om atoms (Figure 13b). In contrast, water molecules in outer layers interact predominantly through shorter, stronger hydrogen bonds with adjacent water layers, resulting in a physisorbed network. This structured hydrogen-bonded network extends several molecular layers from the surface. Collectively, these results demonstrate that the structured hydration layer plays a decisive role in flotation. This layer presents a dual barrier: it lowers the surface energy, and more importantly, it creates a physical and energetic barrier that collectors must penetrate to reach the specific Mg adsorption sites. Therefore, the design of effective flotation reagents for hydrophilic minerals like magnesite must account for this hydration barrier. Promising strategies could involve functional groups capable of either displacing tightly bound water molecules (competitive adsorption) or penetrating the hydrogen-bond network via cooperative interactions.

Table 9.

Changes in the number of hydrogen bonds and bond lengths after adsorption on different water molecule layers.

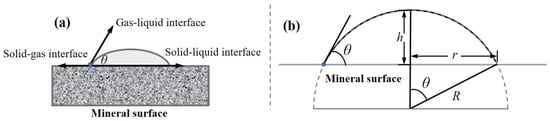

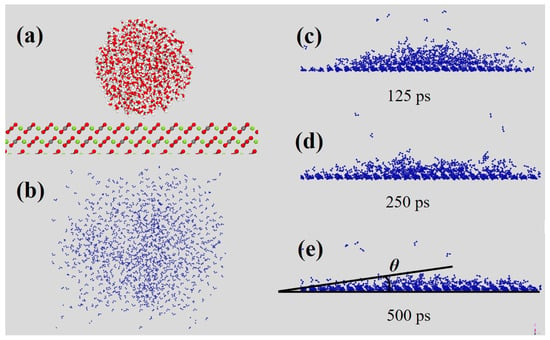

3.3. Simulations of the Water Wetting Process

The contact angle (θ), formed at the three-phase (solid–liquid–gas) contact line under equilibrium conditions, quantifies surface wettability (Figure 14a). A larger contact angle indicates lower surface wettability. The system reached equilibrium within the 500 ps simulation. Therefore, the final equilibrium structure (at 500 ps) was selected as the representative configuration, with snapshots at 125 ps, 250 ps, and 500 ps extracted to illustrate the wetting dynamics (Figure 15). The contact angle was calculated from the equilibrated droplet profile using the geometric method illustrated in Figure 14b and detailed in Equations (2) and (3) [60]:

R2 = (R − h)2 + r2

Figure 14.

(a) Schematic diagram of a contact angle. (b) Various parameters of a simulated contact angle.

Figure 15.

Wetting behavior of water droplets on magnesite. (a) Conformations of the water molecules on magnesite (104) surface. (b) Top view of adsorbed water molecules. (c–e) Front view of changes in water molecules over time after adsorption.

The MD simulations provide a quantitative analysis of the dynamic hydration behavior and wettability of the magnesite surface. The time evolution of the water droplet (Figure 15) clearly demonstrates a spontaneous spreading process, driven by the strong hydration affinity of the magnesite surface. The initially spherical droplet rapidly wets the surface, with water molecules dissociating and migrating to form a stable, expanded hydration film. This behavior is indicative of a high-surface-energy, thermodynamically favorable wetting process. The initial configuration is shown in Figure 15a. For clarity in subsequent analysis, water molecules in the top and side views (Figure 15b–e) are highlighted in dark blue, with the mineral substrate rendered transparent.

The contact angle was derived from extensive sampling and fitting of the equilibrated droplet profile. The reported value represents an average from three independent simulations to ensure statistical reliability (Table 10). The simulated water contact angle for the magnesite (104) surface is 9.2°, confirming its strongly hydrophilic nature. This value aligns well with experimental measurements on pristine, cleaved carbonate surfaces, which typically report contact angles in the range of 0–10° due to rapid surface hydration [61,62]. The minor discrepancy between the simulated angle and some lower experimental values can be attributed to the idealized nature of the computational model (atomically smooth, defect-free surface), transient surface restructuring or contamination in experiments, and the inherent approximations of the force field. Nonetheless, the close quantitative and excellent qualitative agreement confirms that our model accurately captures the essential physics governing the highly hydrophilic magnesite-water interface. This molecular-scale view of the wetting process directly illustrates how the stable, multi-layer hydration network characterized in previous sections manifests as macroscopic hydrophilicity. It reinforces the conclusion that effective collector design must overcome this inherent hydration barrier on the mineral surface.

Table 10.

Relevant data of the simulated contact angle on magnesite surfaces.

4. Conclusions

In contrast to prior studies focused primarily on flotation reagent adsorption, this work elucidates the intrinsic wettability and hydration mechanism of the magnesite-water interface from a multiscale perspective. Combined DFT and MD simulations were employed to systematically investigate atomic-scale interactions, from a single water molecule to a multilayered hydration film, on the magnesite (104) surface. The principal findings are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- Frontier orbital analysis reveals spontaneous electron transfer from the HOMO of water to the LUMO of magnesite. A single water molecule undergoes strong chemisorption at surface Mg sites, forming a stable Mg–Ow bond (length: 0.2091 nm) with an adsorption energy of −91.6 kJ/mol. PDOS and Mulliken population analyses confirm significant electron transfer from surface Mg atoms to the water oxygen (Ow), mediated by hybridization between Mg 2s/2p and Ow 2p orbitals. This interaction drives a distinct outward relaxation of the surface Mg atom and enhances the interfacial electron density.

- (2)

- Water molecules in the first complete monolayer are likewise chemisorbed via direct Ow–Mg bonds. Concurrently, Hw atoms form hydrogen bonds with surface oxygen atoms, which promotes Hw–Ow bond elongation/dissociation and induces surface hydroxylation. PDOS analysis corroborates that the dominant interfacial interactions involve the Ow atoms.

- (3)

- Hydration proceeds via a layered mechanism: strong chemisorption in the first layer, followed by physisorption in outer layers stabilized by an extensive hydrogen-bond network. The chemisorbed, hydroxylated first layer anchors subsequent water layers. The second and third layers are stabilized predominantly by hydrogen bonding, with structural disorder increasing with distance from the surface. The average adsorption energy decreases progressively from −66.3 kJ/mol (monolayer) to −63.2 kJ/mol (bilayer) and −45.6 kJ/mol (trilayer), reflecting this transition from direct chemisorptive to indirect physisorptive interactions.

- (4)

- MD simulation of the water wetting process yields a contact angle of 9.2° for the reagent-free surface, quantifying its strong intrinsic hydrophilicity.

Collectively, these results provide atomic-level insights into the strong intrinsic hydrophilicity of magnesite, which originates from its high affinity for water chemisorption and the stability of the interfacial hydrogen-bonded network. The findings elucidate the molecular origin of the challenging flotation behavior of magnesite, suggesting that effective reagent design must overcome this structured hydration barrier, either by disrupting the network or competing for the primary Mg adsorption sites. Therefore, the novel contribution of this work lies in systematically deconstructing the native (reagent-free) hydrated interface of magnesite. This establishes a crucial molecular-scale baseline for understanding and predicting the competitive adsorption of flotation reagents.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.T.; methodology, D.H.; software, L.Y. and W.Y.; investigation, L.Y.; data curation, L.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, L.Y. and Y.F.; writing—review and editing, Z.L.; supervision, Y.T.; funding acquisition, Y.T. and D.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52104263), Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (2023BCB079), Open Project of Changjiang River Scientific Research Institute (CKWV20231183/KY), and the Graduate Innovation Fund Project of Wuhan Institute of Technology (CX2024049).

Data Availability Statement

All data can be provided as required.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Zhang, H.; Liu, W.; Han, C.; Hao, H. Effects of monohydric alcohols on the flotation of magnesite and dolomite by sodium oleate. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 249, 1060–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Liu, W.; Zhao, B.; Wang, X.; Wang, D.; Hu, Y. Novel insights into the adsorption mechanism of the isopropanol amine collector on magnesite ore: A combined experimental and theoretical computational study. Powder Technol. 2019, 343, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, H.; Miller, J.D. Some physicochemical aspects of water-soluble mineral flotation. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 235, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewan, S.; Carnevale, V.; Bankura, A.; Eftekhari-Bafrooei, A.; Fiorin, G.; Klein, M.L.; Borguet, E. Structure of water at charged interfaces: A molecular dynamics study. Langmuir 2014, 30, 8056–8065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, D.F.; Ninham, B.W. Surface charge reversal and hydration forces explained by ionic dispersion forces and surface hydration. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2011, 383, 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Min, F.; Peng, C.; Liu, L. Investigation on hydration layers of fine clay mineral particles in different electrolyte aqueous solutions. Powder Technol. 2015, 283, 368–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Xu, C.; Chen, Q.; Li, Q.; He, D.; Li, Z.; Fu, Y. Effect of a novel environmental-friendly chelating depressant DTPMP on the flotation separation of magnesite and dolomite. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 690, 162650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landoulsi, J.; Dupres, V. Direct AFM force mapping of surface nanoscale organization and protein adsorption on an aluminum substrate. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 8429–8440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdaguer, A.; Sacha, G.M.; Bluhm, H.; Salmeron, M. Molecular structure of water at interfaces: Wetting at the nanometer scale. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 1478–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelgani, S.C.; Hart, B. TOF-SIMS studies of surface chemistry of minerals subjected to flotation separation—A review. Miner. Eng. 2014, 57, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito e Abreu, S.; Brien, C.; Skinner, W. ToF-SIMS as a new method to determine the contact angle of mineral surfaces. Langmuir 2010, 26, 8122–8130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Peng, M.; Hu, Y.; Nguyen, A.V.; Sun, W. An SFG spectroscopy study of the interfacial water structure and the adsorption of sodium silicate at the fluorite and silica surfaces. Miner. Eng. 2019, 138, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, S.J.; Lafferty, B.J.; Sparks, D.L. An ATR-FTIR spectroscopic approach for measuring rapid kinetics at the mineral/water interface. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2008, 320, 177–185. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, M.; Xu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y. Scale inhibition mechanism of calcium sulfate by gum Arabic: Experimental testing, quantum chemical calculations, and molecular dynamics simulations. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1319, 139516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Sun, H.; Yin, W.; Yang, B.; Cao, S.; Wang, D.; Kelebek, S. Computational modeling of cetyl phosphate adsorption on magnesite (104) surface. Miner. Eng. 2021, 171, 107123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Forestier, L.; Muller, F.; Villieras, F.; Pelletier, M. Textural and hydration properties of a synthetic montmorillonite compared with a natural Na-exchanged clay analogue. Appl. Clay Sci. 2010, 48, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, B.; Zhong, J.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X. Exploring the interfacial stability mechanism between minerals and calcium silicate hydrate from a microscopic perspective. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 473, 141029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Choi, S.; Zhang, Z.; Bai, L.; Chung, S.; Jang, J. Molecular features of hydration layers: Insights from simulation, microscopy, and spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 126, 8967–8977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Y. DFT simulation on interaction of H2O molecules with ZnS and Cu-activated surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 3048–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, P.; Wang, M.; Xu, Q.; Xin, Z.; Wang, X.; Guan, J.; Hou, D. First-principle insights of initial hydration behavior affected by copper impurity in alite phase based on static and molecular dynamics calculations. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 398, 136478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkhonto, D.; de Leeuw, N.H. A computer modelling study of the effect of water on the surface structure and morphology of fluorapatite: Introducing a Ca10(PO4)6F2 potential model. J. Mater. Chem. 2002, 12, 2633–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahn, D.; Hochrein, O. Computational study of interfaces between hydroxyapatite and water. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2003, 5, 4004–4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmerich, K.; Koeniger, F.; Kaden, H.; Thissen, P. Microscopic structure and properties of discrete water layer in Na-exchanged montmorillonite. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 448, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Min, F.; Liu, L.; Chen, J. Hydration properties of alkali and alkaline earth metal ions in aqueous solution: A molecular dynamics study. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2019, 727, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.S.; Fenter, P.; Nagy, K.L.; Sturchio, N.C. Monovalent ion adsorption at the muscovite (001)-solution interface: Relationships among ion coverage and speciation, interfacial water structure, and substrate relaxation. Langmuir 2012, 28, 8637–8650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, N.; Wei, D.; Shen, Y.; Han, C.; Zhang, C. Elimination of the adverse effect of calcium ion on the flotation separation of magnesite from dolomite. Minerals 2017, 7, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Yin, W.; Kelebek, S. Magnesite-dolomite separation using potassium cetyl phosphate as a novel flotation collector and related surface chemistry. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 508, 145191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Yin, W.; Kelebek, S. Selective flotation of magnesite from calcite using potassium cetyl phosphate as a collector in the presence of sodium silicate. Miner. Eng. 2020, 146, 106154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Yin, W.; Kelebek, S. Molecular dynamics simulation of magnesite and dolomite in relation to flotation with cetyl phosphate. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 610, 125928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segall, M.D.; Lindan, P.J.D.; Probert, M.J.; Pickard, C.J.; Hasnip, P.J.; Clark, S.J.; Payne, M.C. First-principles simulation: Ideas, illustrations and the CASTEP code. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2002, 14, 2717–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenzel, J.; Oliveira, A.F.; Jardillier, N.; Heine, T.; Seifert, G. Semi-relativistic, self-consistent charge Slater-Koster tables for density-functional based tight-binding (DFTB) for materials science simulations. Zeolites 2004, 2, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Perdew, J.P.; Chevary, J.A.; Vosko, S.H.; Jackson, K.A.; Pederson, M.R.; Singh, D.J.; Fiolhais, C. Atoms, molecules, solids, and surfaces: Applications of the generalized gradient approximation for exchange and correlation. Phys. Rev. B 1992, 46, 6671–6687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monkhorst, H.J.; Pack, J.D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 1976, 13, 5188–5192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiejna, A.; Lundqvist, B.I. First-principles study of surface and subsurface O structures at Al(111). Phys. Rev. B 2001, 63, 085405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mindat. Magnesite (MgCO3). Available online: https://www.mindat.org/min-2482.html (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Brik, M.G. First-principles calculations of structural, electronic, optical and elastic properties of magnesite MgCO3 and calcite CaCO3. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2011, 406, 1004–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Sun, W.; Hu, Y.; Liu, X. Anisotropic surface broken bond properties and wettability of calcite and fluorite crystals. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2012, 22, 1203–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Feng, Y.; Li, H.; Yang, J.; Liu, M.; Cui, Y. First-principles study on the surface properties and floatability of magnesite tailings and its main gangue. Asia-Pac. J. Chem. Eng. 2024, 19, e3040. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, X.; Mao, S.; Zhang, T. Application progress of molecular simulation in phosphate ore flotation. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2023, 8, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, H.; Entel, P.; Hafner, J. Physisorption of water on salt surfaces. Surf. Sci. 2001, 488, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leenaerts, O.; Partoens, B.; Peeters, F.M. Adsorption of H2O, NH3, CO, NO2, and NO on graphene: A first-principles study. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 77, 125416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, Z.; Chen, D.; Hu, B.; Zhang, C. Adsorption mechanism of water molecules on hematite (104) surface and the hydration microstructure. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 550, 149328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, M.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Zhao, C.; Mu, X. A density functional based tight binding (DFTB+) study on the sulfidization-amine flotation mechanism of smithsonite. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 458, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escamilla-Roa, E.; Sainz-Díaz, C.I.; Huertas, F.J.; Hernandez-Laguna, A. Adsorption of molecules onto (1014) dolomite surface: An application of computational studies for microcalorimetry. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 34, 17583–17590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ao, X.; Cao, Y.; Li, C.; Jiang, C. A first-principle study of the effect of Fe/Al impurity defects on the surface wettability of dolomite. Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process. 2022, 58, 150702. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.K.; Park, J.; Zhang, X.; Park, J.; Bae, J. Numerical study of sub-gap density of states dependent electrical characteristics in amorphous In-Ga-Zn-O thin-film transistors. Electronics 2020, 9, 1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Long, X.; Zhao, C.; Duan, K.; Jin, G. DFT calculation on relaxation and electronic structure of sulfide minerals surfaces in presence of H2O molecule. J. Cent. South Univ. 2014, 21, 3945–3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Long, X.; Li, Y. DFT study of coadsorption of water and oxygen on galena (PbS) surface: An insight into the oxidation mechanism of galena. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 420, 714–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Song, X.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, C. Adsorption behaviors of different water structures on the fluorapatite (001) surface: A DFT study. Front. Mater. 2020, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Cui, W.; Li, L.; Ye, J.; Zhang, Q. Structural, electronic properties with different terminations for fluorapatite (001) surface: A first-principles investigation. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2017, 126, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, D.J.; Bredow, T.; Chandra, A.P.; Cavallaro, G.P.; Gerson, A.R. The effect of iron and copper impurities on the wettability of sphalerite (110) surface. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 2022–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Sun, W.; Ou, L.; Han, H.; Jiang, F.; Pooley, S.; Chen, J.; Peng, J. A case study of the separation of copper-gold sulfide ore from pyrite using a novel flotation reagent scheme: Insight from first-principles calculations. J. Cent. South Univ. 2023, 30, 1552–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, D.; Wu, C.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Lu, Z.; Wang, P.; Li, J.; Ding, Q. Insights on the molecular structure evolution for tricalcium silicate and slag composite: From 29Si and 27Al NMR to molecular dynamics. Compos. Part B Eng. 2020, 202, 108401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y. Adsorption of ethyl xanthate on ZnS (110) surface in the presence of water molecules: A DFT study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 370, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Cao, D.; Wang, X.; Jiao, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Chen, M.; Luo, H.; Zhu, P. Structure of CO2 monolayer on KCl(100). Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 339, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenter, P.; Zhang, Z.; Park, C.; Sturchio, N.C.; Hu, X.M.; Higgins, S.R. Structure and reactivity of the dolomite (104)–water interface: New insights into the dolomite problem. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2007, 71, 566–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leeuw, N.H.; Parker, S.C. Surface–water interactions in the dolomite problem. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2001, 3, 3217–3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti, J. Analysis of the hydrogen bonding and vibrational spectra of supercritical model water by molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 110, 6876–6886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.; Chen, J.; Pang, X.; Jiang, F.; Hui, S.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, D.; Cong, Q.; Wang, T.; Xiao, H.; et al. Wettability of different clay mineral surfaces in shale: Implications from molecular dynamics simulations. Pet. Sci. 2023, 20, 689–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.F.; Cagin, T. Wetting of crystalline polymer surfaces: A molecular dynamics simulation. J. Chem. Phys. 1995, 103, 9053–9061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gence, N. Wetting behavior of magnesite and dolomite surfaces. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2006, 252, 3744–3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Feng, Q.; Zhang, G.; Deng, H. A novel method to improve depressants actions on calcite flotation. Miner. Eng. 2014, 55, 186–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.