Abstract

During the transportation of oil and gas pipelines, the adhesion and aggregation of hydrate particles on the pipe wall are prone to cause pipeline blockage, which seriously impairs the safe and efficient transportation of energy. Taking cyclopentane hydrates as the research object, this study investigated the effects of contact time, wall wettability, and the concentration of kinetic hydrate inhibitor poly(N-vinylcaprolactam) (PVCap) on the adhesion force between hydrates and the wall of X80 pipeline steel by combining a high-precision micromechanical force measurement system with microscopic morphology observation and analysis. The results show that the adhesion force increases with prolonged contact time: it is dominated by capillary liquid bridge force in the initial contact stage with slow growth, and after exceeding the critical time, the sintering effect becomes the dominant factor, leading to a rapid rise in adhesion force that eventually tends to stabilize. Wall wettability significantly influences the adhesion force, and enhanced wettability improves the adhesion force by increasing the liquid bridge volume and the hydrate–wall contact area. PVCap concentration exerts a non-monotonic effect on adhesion force—first decreasing and then increasing. At low concentrations (0.25–1 wt%), PVCap molecules adsorb on the hydrate surface to form a physical barrier, reducing adhesion force. At high concentrations (1.5–2 wt%), excessive PVCap damages hydrate shell integrity, releasing free water to expand the liquid bridge volume and increase adhesion force. This study provides a theoretical basis for eliminating or reducing hydrate blockage in deep-sea oil and gas pipelines.

1. Introduction

With the continuous rise in global energy demand and the gradual depletion of onshore and shallow-sea oil and gas resources, deep-sea oil and gas has become a core area of energy development in the 21st century [1,2,3]. Deep-sea oil and gas fields account for more than 35% of the world’s newly added natural gas production [4,5], and the safety of subsea pipeline transportation is directly related to the stability of energy supply and the economic benefits of the industrial chain [6,7]. However, during actual transportation, liquid films or droplets are prone to form on the pipe wall surface [8,9], which transform into hydrate particles under certain temperature and pressure conditions [10,11,12]. These particles collide, aggregate, and deposit under fluid disturbance to form dense hydrate layers [13], ultimately leading to a reduction in pipe inner diameter, a sharp increase in transportation resistance, and even complete flow interruption in severe cases [14]. Therefore, the adhesion and deposition of hydrates have become a core safety hazard for the efficient transportation of deep-sea oil and gas.

The adhesion behavior between hydrates and the pipeline wall is the initial link of blockage, and the existence form and action mechanism of free water on the wall are key influencing factors [15]. Aspenes et al. found through experiments that when water droplets are deposited on the solid surface, the adhesion force between hydrates and the solid surface is more than 10 times higher than the cohesion force between hydrates. The water-saturated oil phase environment will further increase the adhesion force between hydrate particles, confirming that free water on the wall can promote the growth of hydrate crystals and enhance the bonding strength between particles [16]. Zhou et al. [17] observed through a high-pressure micromechanical force (HP-MMF) device that as the free water on the wall transforms from droplet state to low-saturation state and then to high-saturation state, the cohesion force (a category of generalized adhesion force) between hydrate particles and the wall continues to increase. The cohesion force in the high-saturation state reaches 1194.95 mN/m, which is significantly higher than 677.38 mN/m in the droplet state. Moreover, whether the free water is in the form of dispersed droplets or a continuous liquid film directly determines the compactness of hydrate growth, thereby affecting the final adhesion strength. Lee et al. also confirmed that the wetting behavior of free water is the core inducement for the increase in adhesion force, and the adhesion force can be indirectly inhibited by regulating the wetting of free water with salts [18]. Given the impact of hydrate adhesion force on pipeline blockage, how to weaken this effect through regulatory means and ensure the safety of pipeline transportation has become a key research direction in the field of deep-sea oil and gas transportation. Kinetic hydrate inhibitors (KHIs) have become the focus of current industrial applications and academic research because they can interfere with the hydrate growth and adhesion process [19].

As a widely used kinetic hydrate inhibitor in industry, the regulatory effect of polyvinylcaprolactam (PVCap) on hydrate adhesion force has attracted much attention. Gulbrandsen et al. supplemented from the thermodynamic level and found that PVCap not only delays hydrate formation kinetically but also increases the thermodynamic stability of hydrates, raising the dissociation temperature [20]. Zhou et al. found that 0~1.5 wt% PVCap can reduce the adhesion force between carbon dioxide hydrate particles (by reducing surface roughness and inhibiting particle agglomeration); however, when the concentration exceeds 2 wt%, excessive adsorption of PVCap on the hydrate cage structure interferes with gas–liquid mass transfer, leading to an increase in adhesion force instead [21]. Experiments by Wu et al. also showed that PVCap has an impact on both the adhesion force and cohesion force of cyclopentane hydrates: 0.005~0.5 wt% PVCap can reduce the average cohesion force between particles from 1.49 mN/m to 0.69 mN/m; if PVCap solution is coated on the particle surface, the adhesion force can be further reduced by 45%, and the hydrate growth can also be significantly slowed down [22]. In addition, based on the microscopic observation of the growth morphology and rate of CO2-CH4 hydrate under the action of PVCap, Zhang et al. found that the higher the PVCap concentration, the slower the hydrate growth rate. The slow growth process allows hydrate crystals to arrange orderly with sufficient time, reducing internal pores and surface defects, and further reducing the adhesion probability caused by defect interlocking between particles [23].

However, the above studies mostly focus on static structural characterization methods such as hydrate formation induction period, crystal structure analysis, or surface morphology observation, failing to fully explore the details of the changes in adhesion force and liquid bridge morphology with contact time, nor fully examining the effects of wall wettability and PVCap on hydrate adhesion force.

In this study, cyclopentane hydrate was used to systematically explore the phased influence characteristics of contact time on adhesion force, and reveal the synergistic effect mechanism combined with wall wettability and PVCap concentration. The results of this study can help manage hydrate blockage in subsea pipelines and provide a theoretical basis for ensuring the stability and safety of deep-sea oil and gas transportation.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Experimental Materials

The specific parameters of the key materials used in this experiment are shown in Table 1. Cyclopentane hydrate and methane hydrate in actual natural gas both have a clathrate crystal structure. Both construct a clathrate framework through hydrogen bonds of water molecules and are filled with hydrocarbon molecules as guests. They have good consistency in crystal growth kinetics (such as growth rate and crystal morphology evolution) and molecular adsorption rules with inhibitors (such as PVCap) [24,25], which can effectively simulate the interface interaction characteristics of natural gas hydrate.

Table 1.

Materials for atmospheric-pressure experiments.

2.2. Experimental Equipment

This experiment uses a micromechanical force (MMF) measurement system to achieve accurate measurement of hydrate–wall adhesion force. The core composition and operating conditions are as follows:

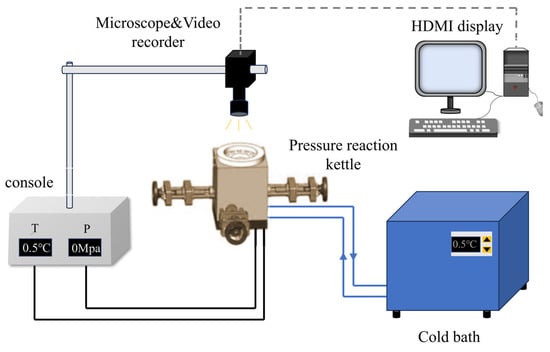

Core measurement device: The system includes a pressure reactor (stainless steel material, effective volume 500 mL), a temperature control system, and a data acquisition system. The reactor is equipped with a three-dimensional adjustable manipulator (precision 0.1 μm) to control the contact and separation between hydrate particles and the X80 steel wall; the data acquisition system consists of an optical microscope (magnification 100~1000 times) and a high-speed camera (resolution 1280 × 800 pixels) to synchronously record the liquid bridge morphology and adhesion force signals. Its structure and working principle are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of a high-pressure micromechanical force (HP-MMF) device.

Working principle: (1) The X80 steel sample is fixed on the bottom sample stage of the stainless steel pressure reactor (effective volume 500 mL); (2) Hydrate particles are attached to the glass fiber (force-sensing element, diameter 125 μm, elastic modulus = 750 GPa) mounted on the three-dimensional adjustable manipulator (precision 0.1 μm); (3) The manipulator controls hydrate particles to contact/separate from the steel surface at a rate of 0.1 mm/s, with a post-contact press-down of 0.01 mm to ensure sufficient contact; (4) The data acquisition system (optical microscope with 100~1000× magnification + high-speed camera with 1280 × 800 pixels) synchronously records the liquid bridge morphology and the glass fiber deformation process; (5) The adhesion force is calculated via Hooke’s law (F = kδ) using the calibrated elastic coefficient (k = 0.012 ± 0.001 N/m) of the glass fiber and the deformation displacement (δ) recorded by the computer.

Experimental conditions: Atmospheric pressure environment; temperature is stabilized at 0.5 °C (temperature control precision ±0.1 °C) through a constant temperature water bath and refrigeration unit; the contact rate between hydrate particles and the wall is 0.1 mm/s, and after contact, it is pressed down by 0.01 mm to ensure sufficient contact; the separation rate is 0.1 mm/s, and the contact time is set to 10~1000 s.

2.3. Experimental Procedures and Methods

2.3.1. X80 Steel Pretreatment

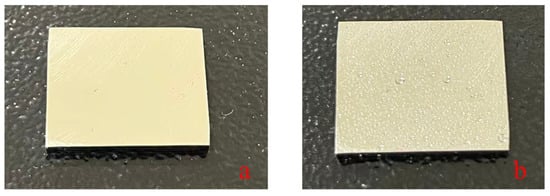

The pretreatment process of X80 steel samples is as follows: (1) Grind the surface with 200, 500, 1000, and 2000 mesh sandpapers in sequence, then polish to smooth with flannel; (2) Clean with deionized water, rust removal lubricating oil, and anhydrous ethanol for 10 min each to remove surface impurities and oxide layers; (3) Dry with cold air and store in a desiccator for later use (as shown in Figure 2).

Figure 2.

(a) Smooth and dry X80 steel. (b) Smooth and moist X80 steel (free water content 0.15 mL/cm2).

Preparation of moist X80 steel samples: Spray deionized water on the surface of dry X80 steel with a microinjector to control the free water content at 0.15 mL/cm2. The spray volume is monitored in real-time by an electronic balance with a precision of 0.1 mg. The prepared samples are used immediately to avoid water evaporation.

2.3.2. Preparation and Formation of Hydrate Particles

Preparation of hydrate particles: The preparation process of cyclopentane hydrate particles requires strict control of temperature, reaction time, and other parameters to ensure the uniformity and integrity of the particles. The specific steps are as follows: (1) Take a clean glass fiber (diameter 125 μm, length 5 cm), clean it with anhydrous ethanol for 10 min to remove surface stains, then dry it for later use; (2) Use a microinjector to absorb PVCap solutions of different concentrations (0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 1.5, and 2 wt%), drop the solution onto the end of the glass fiber, and control the droplet volume by adjusting the displacement of the syringe plunger so that the droplet radius reaches 0.8 ± 0.15 mm; (3) Fix the glass fiber with droplets on a special fixture and freeze it in a low-temperature environment of −20 °C for 2 h to completely solidify the droplets into ice particles, avoiding deformation of the droplets during subsequent hydrate formation.

Formation of hydrates: Take the frozen ice particles together with the fixture out of the refrigerator, quickly transfer them into a pressure reactor pre-cooled to 0.5 °C, and fix them on the three-dimensional manipulator; turn on the constant temperature water bath and refrigeration unit to stabilize the temperature in the reactor at 0.5 °C; use a microinjector to absorb excess cyclopentane (volume 1.5~3 times that of the ice particles), and drop the cyclopentane onto the surface of the ice particles through the sampling port on the top of the reactor; close the sampling port of the reactor, keep the reactor under atmospheric pressure, and start timing. The hydrate formation process lasts for 20 min, during which the growth morphology of hydrates is observed in real-time through an optical microscope.

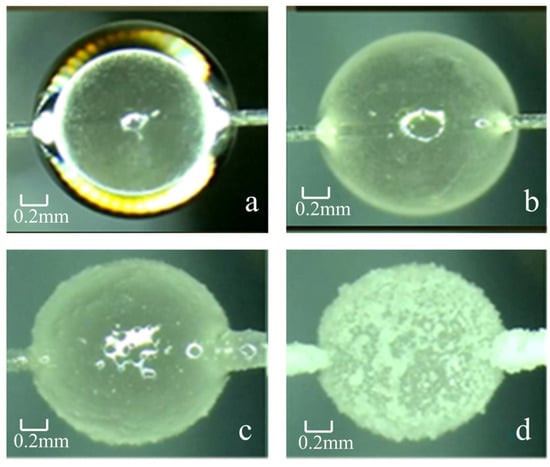

The hydrate formation process is divided into four stages (as shown in Figure 3): Stage a (0~1 min): Cyclopentane droplets quickly wrap the ice particles to form a water-in-oil structure, and the ice particles begin to melt slowly; Stage b (1~5 min): The melted water molecules react with cyclopentane molecules on the surface of the ice particles to form small hydrate cores; Stage c (5~10 min): The hydrate cores continue to grow and gradually diffuse into the ice particles, and the surface of the ice particles is gradually covered by hydrates; Stage d (10~20 min): Hydrate growth is basically completed, the ice particles are completely converted into hydrate particles, and the particle surface is translucent with a dense structure.

Figure 3.

Formation of typical cyclopentane hydrate particles at 0.5 °C without additives. (a) Cyclopentane drop enveloping the water drop; (b) Hydrate core has been formed; (c) Hydrate core has grown to the surface of the particles; (d) Hydrate in its fully formed state.

2.3.3. Adhesion Force Measurement Method

The pull-off method is used to measure the hydrate–wall adhesion force. This method characterizes the adhesion force between the two by measuring the minimum force required to separate the hydrate particles from the wall [26], which has the advantages of simple operation and high measurement precision.

Fix the pretreated X80 steel sample (dry or moist) on the sample stage at the bottom of the pressure reactor to ensure the sample surface is horizontal; turn on the constant temperature water bath and refrigeration unit to stabilize the temperature in the reactor at 0.5 °C for 30 min to achieve thermal equilibrium between the sample and the reactor environment; adjust the three-dimensional manipulator to move the prepared hydrate particles to the front of the X80 steel sample surface, and observe through an optical microscope to ensure the particles are aligned with the sample.

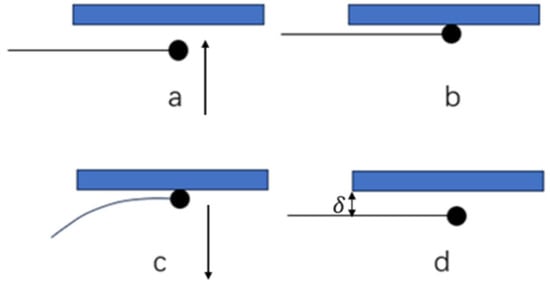

Control the three-dimensional manipulator to move forward at a rate of 0.1 mm/s to make the hydrate particles contact the surface of the X80 steel sample. After contact, continue to move down by 0.01 mm to ensure sufficient contact between the particles and the wall; maintain the contact state, set the contact time (10, 20, 30, 60, 100, 300, 1000 s), and record the formation and change process of the liquid bridge through a high-speed camera during the period; after the contact time ends, control the three-dimensional manipulator to move backward at a rate of 0.1 mm/s until the hydrate particles are completely separated from the surface of the X80 steel sample. During the entire measurement process, the computer records the deformation displacement of the fixed fiber, and the pull-off operation is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Hydrate particle–solid surface pull-off measurement operation diagram. (a) Before the hydrate comes into contact with the wall surface. (b) The moment the hydrate comes into contact with the wall surface. (c) The process of hydrate and wall pull-off. (d) The hydrates are completely pulled off from the wall surface.

The displacement δ of the lower particle during the separation of the two particles is recorded by a high-definition camera. Combined with the relative elastic coefficient of the lower glass fiber, the minimum force required to separate the two hydrate particles is calculated using Hooke’s law, which is the adhesion force between the hydrate particles:

where is the adhesion force (mN); is the relative elastic coefficient of the lower glass fiber (mN/m).

In the experiment, the data points under each specific working condition are the average of more than 40 measurement results, and the 95% confidence interval is calculated as the error bar. Considering that the diameters of hydrate particles in multiple experiments are different, and the change in particle diameter will affect the magnitude of the force, the normalized adhesion force between hydrate particles and the wall is equal to the measured actual force divided by the effective radius :

where is the normalized adhesion force (mN/m), is the measured adhesion force (mN), and is the effective radius of hydrate particles (m). This normalization eliminates the influence of particle size differences on force comparison.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of Contact Time on Hydrate Adhesion Force

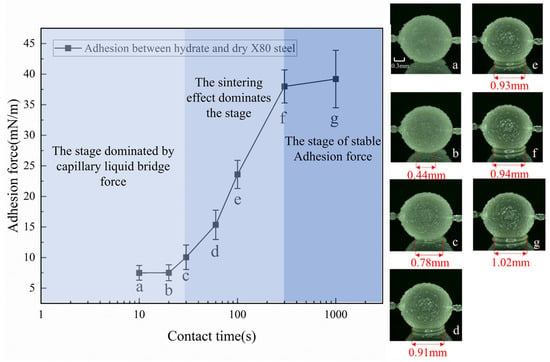

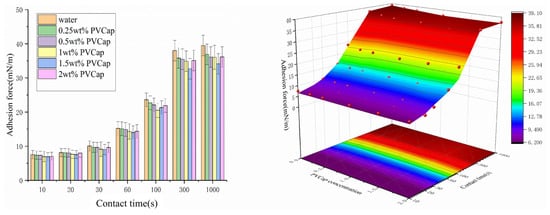

Contact time directly regulates the interaction intensity between hydrate particles and dry X80 steel wall surfaces, the evolution morphology of liquid bridges, and the process of the sintering effect, exhibiting distinct staged characteristics in its influence on the adhesion force (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The phased evolution of the adhesion force between hydrates and dry X80 steel with contact time and the microscopic morphology of the contact area. Hydrate in contact with the dry X80 steel for (a) 10 s, (b) 20 s, (c) 30 s, (d) 60 s, (e) 100 s, (f) 300 s, and (g) 1000 s.

At 10 s of contact (Figure 5a), the hydrate particles exhibited a smooth and translucent surface, with an almost zero liquid bridge width at the contact interface with the X80 steel wall. During the 10~30 s period, the moment the particles come into contact with the wall, the quasi-liquid layer (QLL) on the surface—a liquid water layer with a thickness of several nanometers to tens of nanometers formed by the thermal motion of molecules on the hydrate surface—rapidly flows toward the contact area under capillary action, gradually forming a liquid bridge [27]. At 20 s, the liquid bridge width is only 0.44 mm with a blurred boundary, indicating that the liquid bridge is not yet stable, and the adhesion force is 7.52 mN/m. As the contact time extends to 30 s (Figure 5c), the QLL diffuses more fully, the liquid bridge width increases to 0.78 mm, the boundary becomes clearly visible, and the liquid bridge volume tends to stabilize, with the adhesion force correspondingly rising to 10.05 mN/m. The average growth rate during this stage is 0.084 mN/(m·s). The core reason for the slow growth of adhesion force at this stage is that the particles are mainly in point contact with the wall; the small contact area results in a weak contribution of intermolecular van der Waals forces, making the capillary liquid bridge force the sole dominant factor of adhesion force. Meanwhile, the limited liquid bridge volume determines the small magnitude of adhesion force growth.

When the contact time exceeds 30 s, the system enters the stage dominated by the sintering effect, with significant changes in both phenomena and mechanisms. Within the 30~300 s period, under the low-temperature environment of 0.5 °C, part of the free water in the liquid bridge begins to transform into hydrates. At 100 s (Figure 5e), the liquid bridge width further increases to 0.93 mm, obvious liquid bridge aggregation is observed in the central area, and the adhesion force rapidly rises from 10.05 mN/m to 23.6 mN/m, with an increase rate of 134.8%. At 300 s (Figure 5f), the liquid bridge width tends to stabilize, and the contact area between particles and the wall transforms from point contact to surface contact (the contact area increases to approximately 0.69 mm2), with the adhesion force further rising to 37.99 mN/m.

To quantitatively characterize the growth rate of adhesion force in different stages, the calculation formula is defined as follows:

where is the average growth rate of normalized adhesion force (mN/(m·s)), is the change in normalized adhesion force (mN/m), and is the time interval (s).

The average growth rate during this stage reaches 0.293 mN/(m·s), which is 3.5 times that of the previous stage. This rapid growth stems from the core role of the sintering effect: water molecules in the liquid bridge migrate to the hydrate crystal surface through surface diffusion, volume diffusion, and other means, and interact with the hydroxyl groups on the wall, promoting the continuous growth and fusion of crystals to form a preliminary dense hydrate bonding layer, which significantly enhances the interface bonding strength.

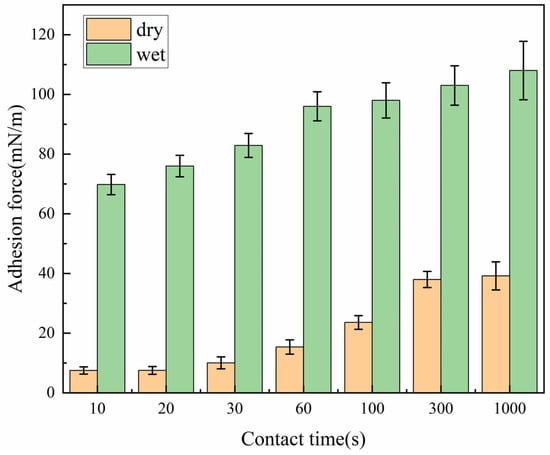

3.2. Effect of Wall Wetting Conditions on Adhesion Force

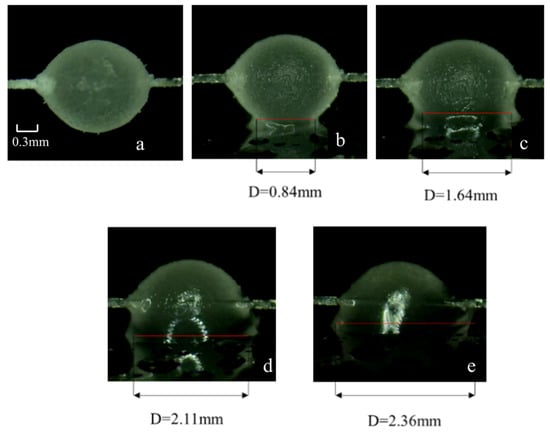

In this section, the adhesion force between hydrate particles and wetted wall surfaces was directly measured and compared with that for dry wall surfaces. The changes in the morphology and adhesion force of hydrate particles under different wall conditions at the same contact time were analyzed (Figure 6 and Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Microscopic morphology of cyclopentane hydrate at different contact times with a moist X80 steel wall (free water content 0.15 mL/cm2). (a) Before contact; (b) 10 s; (c) 30 s; (d) 100 s; (e) 1000 s.

Figure 7.

Normalized adhesion force of hydrates on dry and moist X80 steel (0.15 mL/cm2 water) versus contact time (0.5 °C, atmospheric pressure). Each data point represents the mean ± SD of 40 measurements (5 particles × 8 replicates per particle).

Before contact (Figure 6a), the surface of the moist X80 steel wall is covered with a uniform water film without bubbles or impurities, forming a sharp contrast with the dry wall. At the moment of contact (10 s), the water film on the wall quickly merges with the quasi-liquid layer on the surface of the hydrate particles. Due to the sufficient free water source provided by the water film, the liquid bridge reaches a width of 0.84 mm within 10 s, which is 1.8 times that of the dry wall in the same period (0.44 mm), and the liquid bridge boundary is complete. The adhesion force reaches 69.61 mN/m, which is 925.5% higher than that of the dry wall, with an increase close to an order of magnitude. At 30 s (Figure 6c), the liquid bridge width increases to 1.64 mm, and a small amount of dispersed hydrate crystals begin to appear in the liquid bridge. However, due to the continuous supply of free water from the wall water film to the contact area, the crystals cannot aggregate quickly, the liquid bridge volume is still expanding slowly, and the adhesion force rises to 85.32 mN/m, which is 748.9% higher than that of the dry wall.

At 100 s (Figure 6d), the liquid bridge width of the moist wall reaches 2.11 mm, and the adhesion force reaches 98.75 mN/m, which is 318.4% higher than that of the dry wall (23.6 mN/m); at 1000 s (Figure 6e), the liquid bridge width stabilizes at 2.36 mm, a mixed layer of hydrates and residual free water is formed in the contact area, most of the particles are wrapped by the water film, and the combination with the wall is extremely tight. The adhesion force reaches 108.25 mN/m, which is 174.1% higher than that of the dry wall (39.49 mN/m).

Analysis shows that the free water on the wall enhances adhesion through physical–chemical dual effects: at the physical level, the water film provides a continuous water source for the formation of the liquid bridge, and water molecules migrate rapidly to the contact area through the concentration gradient, which not only greatly increases the liquid bridge volume (the liquid bridge volume of the moist wall at 100 s is about six times that of the dry wall) but also increases the thickness of the quasi-liquid layer of the particles, enhances the surface fluidity of the particles, and promotes the rapid transformation of the contact area from point contact to surface contact (the contact area at 10 s is about three times that of the dry wall), significantly improving the action intensity of capillary liquid bridge force and intermolecular van der Waals force.

3.3. Effect of PVCap Concentration on Adhesion Force

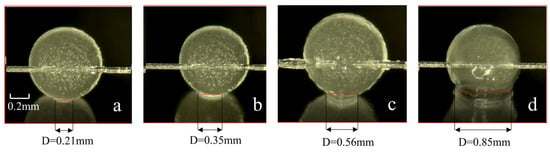

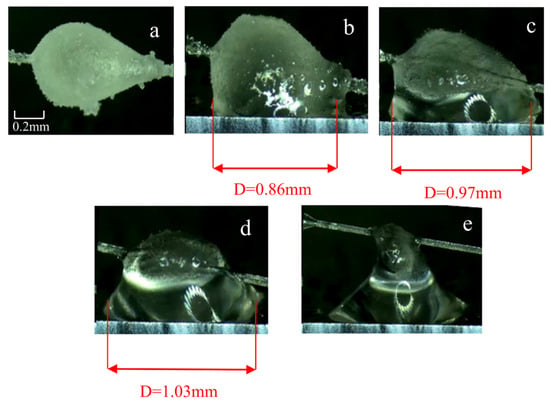

As a widely used hydrate kinetic inhibitor in industry, PVCap concentration affects the adhesion force between hydrate and X80 steel wall by changing its adsorption behavior at the hydrate–wall interface, the integrity of hydrate shell growth, and the evolution path of the liquid bridge. Moreover, its effect of reducing adhesion force varies significantly with contact time. Based on six PVCap concentration gradients (0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2 wt%) and combined with the optical microscope observation of liquid bridge morphology and normalized adhesion force data at different contact times (10, 30, 100, 300, 1000 s), this section systematically analyzes the change law of the effect of reducing adhesion force with time under each concentration (Figure 8 and Figure 9).

Figure 8.

Images of different contact times between cyclopentane and the wall surface of dry X80 steel under the PVCap (1 wt%). (a) Hydrate in contact with the wall for 10 s. (b) Hydrate in contact with the wall for 30 s. (c) Hydrate in contact with the wall for 100 s. (d) Hydrate in contact with the wall for 1000 s.

Figure 9.

The adhesion force between hydrates and the wall surface under different concentrations and contact times with dry X80 steel.

Due to insufficient molecular adsorption, 0.25 wt% PVCap has a gentle and overall small effect on reducing adhesion force with contact time. At 10 s of contact, the adhesion force is 7.36 mN/m, which is slightly lower than 7.52 mN/m of the pure water group, showing no reduction effect. At 100 s of contact, the adhesion force is reduced by 3.4% compared with the pure water group, showing a weak reduction effect. At 1000 s of contact, the adhesion force is 37.6 mN/m, which is 1.89 mN/m lower than 39.49 mN/m of the pure water group, with a reduction of 4.8%. The reduction effect is slightly enhanced with the extension of time but remains at a low level. This indicates that low-concentration PVCap requires a long time to accumulate sufficient adsorption capacity to form a relatively complete barrier layer, thereby initially reducing the adhesion force.

At 1 wt% PVCap, the adsorption rate of molecules matches the hydrate crystal growth rate, achieving a balance between effective barrier formation and hydrate shell integrity. Among all concentrations, 1 wt% PVCap exhibits the most significant effect in reducing the adhesion force. This effect gradually strengthens with prolonged contact time, reaches the optimum at 100 s, and remains stable thereafter—with the adhesion reduction effect at 100 s being significantly superior to that at 10 s. At 10 s of contact (as shown in Figure 8a), a uniform fog-like coating is formed on the surface of hydrate particles due to the dense adsorption of PVCap molecules. The liquid bridge width is only 0.21 mm (47.7% of that in the pure water group, 0.44 mm), with an irregular boundary and shrinkage gaps. At this stage, the adhesion force is 6.91 mN/m, which is 0.61 mN/m lower than that of the pure water group (7.52 mN/m), corresponding to a reduction rate of 8.1%. At this stage, PVCap has just formed an initial physical barrier on the particle surface, which can only inhibit the initial formation of the liquid bridge and exerts a limited effect on reducing the adhesion force. After 30 s of contact (as shown in Figure 8b), the liquid bridge width increases to 0.35 mm (50.7% of that in the pure water group, 0.62 mm), and the adhesion reduction rate rises to 8.2%. This indicates that with the extension of contact time, the hindering effect of the PVCap barrier layer on water molecule diffusion gradually becomes apparent, delaying crystal growth and slightly enhancing the reduction effect. When the contact time reaches 100 s (as shown in Figure 8c), the liquid bridge width is 0.56 mm, and the adhesion force is 20.5 mN/m—3.1 mN/m lower than that of the pure water group (23.6 mN/m), with a maximum reduction rate of 13.1%, making it the optimal node for the reduction effect among all contact times. At this stage, the PVCap barrier layer fully exerts its dual effects: on the one hand, it continuously hinders the expansion of the liquid bridge to reduce the capillary liquid bridge force; on the other hand, it effectively inhibits the growth and aggregation of hydrate crystals to avoid the sintering effect-induced enhancement of adhesion. Under the synergistic action of these two mechanisms, the adhesion reduction effect reaches its peak. At 1000 s of contact (as shown in Figure 8d), the reduction rate drops back to 8.1%, which is close to that at 10 s but with a higher absolute reduction value. At this point, the PVCap barrier layer does not show obvious degradation; the reduction effect fails to further enhance only because the adhesion force of the pure water group tends to stabilize, yet it still maintains an effective reduction effect.

1.5 wt% PVCap is the critical turning point concentration affecting the hydrate–wall adhesion force. It neither shows the stable and significant reduction effect of low concentration (such as 1 wt%) nor fully exhibits the promotion characteristics of high concentration (such as 2 wt%). Instead, its effect on adhesion force varies with the extension of contact time. At 10 s of contact, 1.5 wt% PVCap can still produce a weak reduction effect on adhesion force. From Figure 9, the adhesion force at this stage is 6.88 mN/m, which is 0.64 mN/m lower than that of the pure water group (7.52 mN/m), with a reduction of 8.5%. The core reason for this weak reduction effect is that when the contact time is short, the excessive PVCap molecules have not fully interfered with the initial formation of the hydrate shell. PVCap molecules (molecular weight ~104 Da) are adsorbed on the hydrate surface through hydrogen bonding between amide groups (–CONH–), and water molecules in the hydrate cage and the local adsorption layer can still form a small amount of hydrogen bonds with water molecules through polar amide groups [28], initially hindering the initial expansion of the liquid bridge, thereby slightly weakening the adhesion force [29]. When the contact time extends to 100 s, the reduction effect of 1.5 wt% PVCap is significantly attenuated and nearly disappears. At this time, the adhesion force is 21.3 mN/m, which is 4.3% higher than that of the 1 wt% group in the same period (20.5 mN/m), indicating that its reduction effect is weaker than that of the optimal concentration. When the contact time reaches 1000 s, the effect of 1.5 wt% PVCap on hydrate adhesion force still shows a decreasing trend. At this time, the adhesion force is 34.8 mN/m, which is 4.69 mN/m lower than that of the pure water group (39.49 mN/m), with a reduction of 11.9%, and the reduction effect reaches the peak. However, this reduction is due to the slight decrease in the adhesion force of the pure water group after reaching the peak. In fact, PVCap at this concentration has begun to damage the hydrate shell [30], and only the limited free water released by shell rupture under long-term action barely maintains the weak reduction effect. Adsorption site oversaturation on the hydrate surface leads to molecular aggregation, forming uneven adsorption layers. Local high concentrations of PVCap disrupt the ordered growth of hydrate cages, resulting in structural defects (e.g., lattice distortion, microcracks) in the hydrate shell [31].

Under the concentration of 2 wt% PVCap, before contact (as shown in Figure 10a), hydrate particles form an irregular and rough morphology. This is because excessive inhibitor molecules are densely adsorbed on the surface of hydrate crystal nuclei, but the adsorption is not uniformly distributed. In areas with local desorption or weak adsorption, crystals grow rapidly to form protrusions. At 10 s of contact (as shown in Figure 10b), the hydrate particles are transparent and rough-surfaced, with a liquid bridge width of 0.86 mm and an adhesion force of 7.23 mN/m—only 0.29 mN/m lower than that of the pure water group (7.52 mN/m), with a reduction rate of 7.2%, showing almost no practical reduction effect. At 100 s of contact (as shown in Figure 10d), the liquid bridge width is 1.03 mm (110.4% of that in the pure water group), and the liquid bridge is filled with free water. The adhesion force is 21.9 mN/m, which is only 1.7 mN/m lower than that of the pure water group (23.6 mN/m). At this stage, some particles rupture and release internal free water, further expanding the liquid bridge volume. Figure 10e shows the pull-off image when the contact time reaches 1000 s. At this point, the hydrate particles are incomplete due to the loss of a large amount of free water, and the measured adhesion force is 38.1 mN/m—1.39 mN/m lower than that of the pure water group (39.49 mN/m), with a reduction rate of 3.5%. However, this reduction is a result of the natural decline in the adhesion force of the blank group; in reality, excessive PVCap has completely lost its ability to reduce the adhesion force due to shell damage and liquid bridge volume expansion.

Figure 10.

Images of different contact times between cyclopentane and the wall surface of dry X80 steel with the PVCap (2 wt%). (a) Before hydrate particles come into contact with the wall surface. (b) Hydrate in contact with the wall for 10 s. (c) Hydrate in contact with the wall for 30 s. (d) Hydrate in contact with the wall for 100 s. (e) Hydrate in contact with the wall for 1000 s.

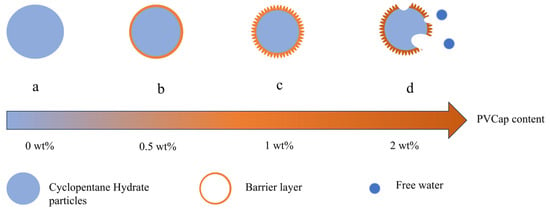

To further clarify the concentration-dependent mechanism of PVCap on hydrate–wall adhesion, Figure 11 schematically summarizes the core interactions, which are fully supported by the aforementioned experimental results and microscopic observations: (Figure 11a) Pure water system (0 wt% PVCap): Hydrate particles form dense block-like structures with a rough surface. Free water on the particle surface easily forms stable liquid bridges with the X80 steel wall, leading to high adhesion force (e.g., 39.49 mN/m at 1000 s). (Figure 11b) Low concentration (0.5 wt% PVCap): PVCap molecules adsorb sparsely, forming a thin barrier layer. This partially inhibits liquid bridge formation but requires prolonged contact time, resulting in loose powder-like aggregates with reduced adhesion. (Figure 11c) Optimal concentration (1 wt% PVCap): PVCap molecules form a uniform and dense barrier layer without damaging the hydrate shell. The barrier layer not only blocks liquid bridge expansion (liquid bridge width = 0.56 mm at 100 s, 47.7% of the pure water group) but also inhibits hydrate crystal sintering. The hydrate surface becomes smooth, minimizing contact area and achieving the maximum adhesion reduction rate (13.1% at 100 s). (Figure 11d) High concentration (2 wt% PVCap): Excessive PVCap molecules saturate the hydrate surface, causing uneven aggregation and hydrate shell defects (e.g., microcracks). Under contact pressure, the defective shell ruptures, releasing encapsulated free water that merges with the QLL to expand liquid bridge volume (110.4% of the pure water group at 100 s). Additionally, aggregated PVCap forms physical bridges between hydrates and the wall, leading to transparent and fragile particles with increased adhesion force.

Figure 11.

Schematic diagram of the influence mechanism of PVCap concentration on hydrate–wall adhesion: (a) Pure water system (0 wt% PVCap): Hydrate particles form dense block-like structures with a rough surface; (b) Low concentration (0.5 wt% PVCap): PVCap molecules adsorb sparsely, forming a thin barrier layer, resulting in loose powder-like aggregates; (c) Optimal concentration (1 wt% PVCap): PVCap molecules form a uniform and dense barrier layer without damaging the hydrate shell; (d) High concentration (2 wt% PVCap): Excessive PVCap molecules cause hydrate shell defects and free water exudation, leading to transparent and fragile particles.

Based on the above experimental results, the influence mechanism of PVCap on the adhesion behavior of hydrates is proposed, as shown in Figure 11. Analysis indicates that the effect of PVCap on reducing hydrate adhesion force is correlated with its concentration: low concentrations (0.25~0.5 wt%) require a long time to accumulate sufficient adsorption capacity to exert a significant effect; high concentrations (1.5~2 wt%) lead to excessive PVCap molecules damaging the structural integrity of the hydrate shell, resulting in shell fragilization. With the extension of contact time, such high concentrations not only fail to reduce the adhesion force but also cause it to increase.

The above experimental conclusions on hydrate–wall adhesion mechanisms provide important theoretical support for the industrial control of hydrate blockage in deep-sea oil and gas pipelines. By combining cutting-edge technologies reported in recent studies, the practical application scenarios of our methodology can be further expanded, forming targeted engineering solutions. Combining the in situ ultrasonic characterization technology proposed by Chen [32], our adhesion force data can be integrated into non-destructive testing (NDT) systems for pipeline integrity monitoring. Referring to the surface engineering strategy of Shui [33] for oil–water separation membranes, we propose modifying pipeline inner walls with superhydrophobic coatings (e.g., fluorinated polymers) to reduce wettability. This synergizes with our finding that dry walls reduce adhesion force by 60–80%—coating modification combined with 1 wt% PVCap can reduce hydrate adhesion by over 90%, significantly lowering blockage risks in deep-sea pipelines. Some recent studies [34,35] showed that temperature-sensitive polymers can reversibly switch between hydrophilic and hydrophobic states under mild thermal stimulation, which aligns with our finding that wall wettability is a key determinant of adhesion force. From the perspective of concentration regulation, the on-site application should prioritize the selection of a PVCap concentration range of approximately 1~1.5 wt%, which can maximize the reduction in adhesion force during the critical period of contact between hydrate particles and the pipe wall (around 100 s).

Meanwhile, the on-site application needs to synergistically consider the wall wettability conditions: in pipeline areas with moist wall surfaces or severe condensation, the PVCap concentration should be appropriately reduced to 0.5~1 wt% to avoid excessive expansion of liquid bridge volume caused by the combined action of free water on the wall and high-concentration PVCap; under dry wall conditions, a concentration of 1 wt% can be maintained to continuously inhibit liquid bridge formation and sintering effect through the barrier layer effect. In addition, it is recommended to combine PVCap concentration control with measures such as pipeline flow rate regulation and thermal insulation temperature control. By shortening the effective contact time between hydrate particles and the pipe wall, the duration of the inhibitory effect of PVCap can be prolonged, further reducing the risk of blockage.

4. Conclusions

Taking cyclopentane hydrate as the model system, combined with a high-precision micromechanical force measurement system, this study systematically explores the influence mechanisms of contact time, wall humidity, and PVCap concentration on hydrate–wall adhesion force. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) Contact time affects the adhesion force between hydrate particles and the wall through a phased mechanism of capillary liquid bridge force–sintering effect. The period of 10~30 s is the stage dominated by capillary liquid bridge force, and the adhesion force slowly increases from 7.52 mN/m to 10.05 mN/m, with an average growth rate of 0.084 mN/(m·s). In this stage, the formation and growth of the liquid bridge mainly depend on the quasi-liquid layer on the hydrate surface, and the capillary liquid bridge force is the main source of adhesion force. The period of 30~1000 s is the stage dominated by the sintering effect, and the adhesion force rapidly increases from 10.05 mN/m to 39.49 mN/m, with an average growth rate of 0.293 mN/(m·s) in the early stage (30~300 s), and tends to be stable in the later stage (300~1000 s). In this stage, the free water in the liquid bridge is converted into hydrate crystals, and the particles form a dense bonding layer with the wall, so the sintering effect becomes the dominant factor for the increase in adhesion force.

(2) The free water on the wall significantly enhances the adhesion force between hydrate particles and the wall through physical–chemical dual effects: the physical enhancement is that the free water on the wall increases the liquid bridge volume and the hydrate–wall contact area. At 10 s, the adhesion force of the moist wall (69.61 mN/m) is 925.5% higher than that of the dry wall (7.52 mN/m); the chemical enhancement is that the free water forms a hydrogen bond network with the hydrates and the hydroxyl groups on the wall surface, enhancing the intermolecular force. At 1000 s, the adhesion force of the moist wall reaches 108.25 mN/m, which is 174.1% higher than that of the dry wall. The synergistic effect of the dual effects makes the adhesion force of the moist wall significantly higher than that of the dry wall, and the growth trend is more obvious.

(3) The effect of PVCap on adhesion force has a transition from inhibition to promotion. At low concentrations (0.25~1 wt%), it reduces adhesion force through the adsorption-barrier mechanism, and the maximum reduction in adhesion force reaches 13.1% at 1 wt%; PVCap molecules are adsorbed on the hydrate surface to form a 2~5 nm barrier layer, hindering the formation of liquid bridges and molecular diffusion. At high concentrations (1.5~2 wt%), it weakens the inhibition effect through the shell defect-free water exudation mechanism, and the adhesion force at 2 wt% is 5.0% higher than that of the 1 wt% system; excessive PVCap leads to the fragility of the hydrate shell, and free water exudes during contact, increasing the liquid bridge volume. The optimal concentration range of PVCap in this study is 1~1.5 wt%. Within this range, the inhibition effect is significant at most contact times, and only 1.5 wt% shows a weak promotion at long contact times (such as 100 s), with the best comprehensive inhibition efficiency.

These findings are of great significance for understanding the deposition of hydrates on pipeline surfaces and optimizing the application of kinetic inhibitors in deep-water oil and gas transportation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Z.; methodology, G.Q.; software, Y.L.; validation, W.W.; formal analysis, Z.L.; investigation, G.Q.; resources, G.Q.; data curation, G.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, G.Q.; writing—review and editing, G.Q.; visualization, G.Q.; supervision, G.Q.; project administration, Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 51974037, 52004039 and 52274061), the CNPC Innovation Foundation (Grant No. 2022DQ02-0501), and the Major Project of Universities Affiliated to Jiangsu Province Basic Science (Natural Science) Research (Grant No. 24KJA440001), all of which are gratefully acknowledged.

Data Availability Statement

Most of the data presented in this paper is included in the main manuscript, and additional data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zou, C.; Zhai, G.; Zhang, G.; Wang, H.; Zhang, G.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Wen, Z.; Ma, F.; Liang, Y.; et al. Formation, Distribution, Potential and Prediction of Global Conventional and Unconventional Hydrocarbon Resources. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2015, 42, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Zhang, G.; Wang, Z.; Wen, Z.; Tian, Z.; Wang, H.; Ma, F.; Wu, Y. Distribution and Potential of Global Oil and Gas Resources. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2018, 45, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Limmer, L.; Frey, H.; Kelland, M.A. N-Oxide Polyethers as Kinetic Hydrate Inhibitors: Side Chain Ring Size Makes the Difference. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 4067–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Meng, J.; Long, Y.; Yan, Y.; Li, M.; Huang, Z.; Liang, Y. Reducing Carbon Footprint of Deep-Sea Oil and Gas Field Exploitation by Optimization for Floating Production Storage and Offloading. Appl. Energy 2020, 261, 114398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmawan, A.; Eka Saputra, R.; Astuti, Y. Structural, Thermal and Surface Properties of Sticky Hydrophobic Silica Films: Effect of Hydrophilic and Hydrophobic Precursor Compositions. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2020, 761, 138076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Xiao, S.; Zhou, D.; Zhu, H.; Bao, Y.; Li, T.; Tu, J.; Kyazze, M.S.; Han, Z. Numerical Analysis of Coarse Particle Two-Phase Flow in Deep-Sea Mining Vertical Pipe Transport with Forced Vibration. Ocean Eng. 2024, 301, 117550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Zhou, J.; You, Y.; Wang, X. Time-Domain Analysis of Vortex-Induced Vibration of a Flexible Mining Riser Transporting Flow with Various Velocities and Densities. Ocean Eng. 2021, 220, 108427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhou, C.; Li, M.; Tong, S.; Qi, M.; Wang, Z. Direct Measurements of the Interactions between Methane Hydrate Particle-Particle/Droplet in High Pressure Gas Phase. Fuel 2023, 332, 126190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J. Prediction of the Internal Corrosion Rate for Oil and Gas Pipelines and Influence Factor Analysis with Interpretable Ensemble Learning. Int. J. Press. Vessels Pip. 2024, 212, 105329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; Dou, B.; Liu, N.; Yang, M.; Song, Y. Hydrate Formation and Blockage in Inlet/Outlet and Slope Pipes of Gas–Water–Oil Transportation Pipeline. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 18489–18501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Yin, Z.; Linga, P.; Veluswamy, H.P.; Liu, C.; Chen, Q.; Hu, G.; Sun, J.; Wu, N. Experimental Investigation on the Production Performance from Oceanic Hydrate Reservoirs with Different Buried Depths. Energy 2022, 242, 122542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, G.; Xu, M.; Ou, W.; Niu, C.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, N.; Sun, J. Interfacial Strength between Ice and Sediment: A Solution towards Fracture-Filling Hydrate System. Fuel 2022, 330, 125553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xu, Z.; Song, K.; Xu, T.; Qian, Y.; Yao, M.; Song, G.; Li, Y. Study on Decomposition Characteristics of Natural Gas Hydrate in Pipeline under the Condition of Thermodynamic Inhibitor. Langmuir 2025, 41, 15106–15119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, W.; Hu, X.; Song, S.; Yang, F. Blockage Detection Techniques for Natural Gas Pipelines: A Review. Gas Sci. Eng. 2024, 122, 205187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, H.; Liu, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhang, L. The Effect of Subcooling on Hydrate Generation and Solid Deposition with Two-Phase Flow of Pure Water and Natural Gases. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 301, 120718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspenes, G.; Dieker, L.E.; Aman, Z.M.; Høiland, S.; Sum, A.K.; Koh, C.A.; Sloan, E.D. Adhesion Force between Cyclopentane Hydrates and Solid Surface Materials. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2010, 343, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Ren, Z.; Yu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Du, H.; Lv, X.; Yuan, Q. Study of Sintering Behavior of Methane Hydrate Particles on the Wall Surface. Langmuir 2024, 40, 6537–6549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Baek, S.; Kim, J.-D.; Lee, J.W. Effects of Salt on the Crystal Growth and Adhesion Force of Clathrate Hydrates. Energy Fuels 2015, 29, 4245–4254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navaneetha Kannan, S.; Delgado-Linares, J.G.; Makogon, T.Y.; Koh, C.A. Synergistic Effect of Kinetic Hydrate Inhibitor (KHI) and Monoethylene Glycol (MEG) in Gas Hydrate Management. Fuel 2024, 366, 131326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulbrandsen, A.C.; Svartaas, T.M. Effect of Poly Vinyl Caprolactam Concentration on the Dissociation Temperature for Methane Hydrates. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 8505–8511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.-D.; Zhao, Y.-E.; Yu, H.-J.; Xiao, Y.-Y.; Li, X.-Y.; Ma, Q.-L.; Du, H. Study of the Microscopic Effect of PVCap on CO2 Hydrate Generation and Adhesion. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 6195–6204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Aman, Z.M.; May, E.F.; Kozielski, K.A.; Hartley, P.G.; Maeda, N.; Sum, A.K. Effect of Kinetic Hydrate Inhibitor Polyvinylcaprolactam on Cyclopentane Hydrate Cohesion Forces and Growth. Energy Fuels 2014, 28, 3632–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Lang, C.; Yang, L.; Zhao, J.; Song, Y. Crystal Growth of CO2–CH4 Hydrate on a Solid Surface with Varying Wettability in the Presence of PVCap. Cryst. Growth Des. 2024, 24, 4697–4706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Kumar, A.; Johns, M.L.; May, E.F.; Aman, Z.M. Experimental Investigation to Elucidate the Hydrate Anti-Agglomerating Characteristics of 2-Butoxyethanol. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 471, 144288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, P.; Lv, X.; Yu, Y.; Yu, W.; Ma, Q.; Wang, C.; Zhou, S.; et al. Rheological and Dissociation Characteristics of Cyclopentane Hydrate in the Presence of Amide-Based Surfactants and Span 80: From Slurry to Particle. Energy 2025, 328, 136601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Liu, H.; Qiu, G.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Du, H.; Li, S.; Fan, K. Effects of Pipeline Wall Surface Corrosion and PVP on Adhesion Behavior between Cyclopentane Hydrate and Inner Surface of Pipeline. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 18631–18642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aman, Z.M.; Leith, W.J.; Grasso, G.A.; Sloan, E.D.; Sum, A.K.; Koh, C.A. Adhesion Force between Cyclopentane Hydrate and Mineral Surfaces. Langmuir 2013, 29, 15551–15557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Guo, J.; Chen, G.; Zhong, J.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, J. Molecular Insights into the Kinetic Hydrate Inhibition Performance of Poly(N-Vinyl Lactam) Polymers. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2020, 83, 103504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulbrandsen, A.C.; Svartås, T.M. Effects of PVCap on Gas Hydrate Dissociation Kinetics and the Thermodynamic Stability of the Hydrates. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 9863–9873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olarinoye, F.O.; Kang, S.-P.; Ajienka, J.A.; Ikiensikimama, S.S. Synergy between Two Natural Inhibitors via Pectin and Mixed Agro-Waste-Based Amino Acids for Natural Gas Hydrate Control. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 239, 212967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminnaji, M.; Anderson, R.; Hase, A.; Tohidi, B. Can Kinetic Hydrate Inhibitors Inhibit the Growth of Pre-Formed Gas Hydrates? Gas Sci. Eng. 2023, 109, 104831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Qiu, F.; Xia, L.; Xu, L.; Jin, J.; Gou, G. In Situ Ultrasonic Characterization of Hydrogen Damage Evolution in X80 Pipeline Steel. Materials 2024, 17, 5891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shui, G.; Zhao, Q.; Chu, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y. Engineering the surface wettability: Recent advances in oil-water separation membranes. Energy Environ. Sustain. 2025, 1, 100040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Cheng, Z.; Yu, N.; Tian, Y.; Meng, J. A flexible skin material with switchable wettability for trans-medium vehicles. Int. J. Smart Nano Mater. 2025, 16, 419–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhou, S.; Li, B.; Wei, Y.; Wang, H. Investigation Interfacial Wetting Behavior of Copper Matte/Slag/Fe3O4 Enriched Intermediate Layer During High Temperature Smelting. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2025, 56, 449–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.