Abstract

Erosion wear represents a significant issue in piping systems across energy and chemical industries, particularly in elbows. This study develops a prediction model for erosion wear based on tangential and normal impact energy for elbow tubes fabricated from zinc oxide-modified bidirectional E-glass fiber-reinforced epoxy resin composites (ZnO-BE-GFRP). Using a combined CFD-DEM approach, the wear characteristics under gas–solid two-phase flow conditions were systematically investigated. The model quantifies the contributions of tangential and normal impact energy to material removal through the specific energy for cutting wear (et) and the specific energy for deformation wear (en), with key parameters calibrated against experimental data from ZnO-BE-GFRP. This study shows that the increase in gas velocity significantly intensifies wear, and the wear area extends towards the middle of the elbow as the gas velocity increases. The 40–45° area of the elbow is a high-risk wear zone due to the concentration of particle kinetic energy and high-frequency collisions. The particle size distribution has a significant impact on wear: as the degree of particle dispersion increases, the wear on the elbow extrados decreases.

1. Introduction

Erosion wear presents a pervasive challenge across various industrial sectors, including energy, chemical processing, agriculture, mining, and metallurgy [1,2,3,4]. In the oil and gas industry, for instance, pipelines used for transportation are continuously exposed to gaseous, liquid, and multiphase flow media. Solid particles entrained within these fluids can lead to persistent erosion wear on the inner pipe walls. Since industrial equipment often operates under continuous operation, sustained wear of critical components may pose significant safety risks to production processes. Hence, developing accurate predictive models for erosion wear is of considerable engineering importance, as it aids in optimizing equipment structural design and extending service life.

In the 1960s, Finnie [5] proposed a micro-cutting theoretical model, laying the groundwork for the study of erosion wear in plastic materials. Subsequently, Bitter [6] systematically expanded the theoretical framework and developed a unified wear model applicable to both plastic and brittle materials. Neilson and Gilchrist [7] simplified Bitter’s model by employing approximate trigonometric functions to fit experimental data from plastic materials, thereby extending its applicability to brittle materials as well. Grant and Tabakoff [8] introduced a wear model suitable for steel and aluminum alloys, emphasizing the maximum impact angle as a key parameter. Oka et al. [9,10] established a general prediction framework for erosion wear based on material hardness parameters, significantly improving the model’s engineering applicability. Building upon Finnie’s wear model, Zhao et al. [11] enhanced an energy dissipation-based prediction model for plastic materials by correlating tangential impact energy with wear rate. The E/CRC model developed by Zhang et al. [12] incorporated mechanisms of gas–solid/liquid–solid multiphase flow erosion wear. Its numerical predictions show good agreement with laser Doppler velocimetry experimental data, demonstrating the model’s reliability in multiphysics coupling analysis.

However, establishing a wear model alone is insufficient to fully characterize the erosion wear phenomena in pipelines. Studies on pipeline erosion wear often require integration with multiphase flow systems for comprehensive analysis, such as liquid–solid two-phase flow [12], gas–solid two-phase flow [13], and gas–liquid–solid three-phase flow [14]. Therefore, it is essential to combine multiphase flow solution methods with wear prediction models. A systematic analysis of pipeline erosion wear can be achieved through coupled approaches that integrate flow field simulation and particle tracking. Currently, the mainstream multiphase flow solution methods include two typical paradigms: the Computational Fluid Dynamics—Discrete Phase Model (CFD-DPM) method [15] based on the Euler–Lagrange framework, and the Computational Fluid Dynamics—Discrete Element Method (CFD-DEM) [16].

Peng and Cao [17] employed a bidirectional coupling CFD-DPM method to simulate elbow erosion and assessed the relationship between the Stokes number and the location of maximum wear, thereby enabling the prediction of the most severe wear positions under various conditions. Lin et al. [18] combined the CFD-DPM method with a modified wear model based on the Edward model to investigate erosion distribution in tube elbows. Their findings indicated that gravity significantly influences the position of maximum wear in low-speed, high-pressure pipelines. Mohebi et al. [19] applied the CFD-DPM method to study erosion in bends with different curvature angles, and their simulation results showed high consistency with experimental measurements. A notable limitation of the CFD-DPM method, however, is its applicability to only dilute-phase particle systems.

For the study of dense-phase particle-laden multiphase flows, the CFD-DEM method is generally employed. The CFD-DEM coupling model developed by Chen et al. [20] revealed how elbow curvature affects the particle impact angle. Their results demonstrated that larger curvature elbows exacerbate erosion wear due to increased particle impact angles, leading to the proposal of an engineering optimization strategy that favors smaller curvature elbows. Ma et al. [21] utilized a CFD-DEM coupling model to analyze the flow characteristics of shotcrete within pipelines, highlighting significant pressure differences and secondary flow between the extrados and intrados surfaces of the elbow, which reduce the impact velocity of solid particles on the outer wall. Liao et al. [22] employed the CFD-DEM method to investigate wear characteristics during concrete pumping. Their study suggested that maintaining a pumping speed between 2 and 3 m/s and a coarse aggregate volume fraction of 15–20% can effectively balance wear and transportation efficiency. Beyralvand et al. [23] employed the CFD-DEM method to systematically evaluate the mitigating effects of elbow geometry on erosion wear in gas–solid flows. The study demonstrated that ribbed elbows with specific inclination angles can significantly reduce the maximum erosion rate. Xiao et al. [24] employed the CFD-DEM method to conduct a comparative analysis of the gas–solid flow characteristics and erosion behavior between a modified vortex elbow and a standard elbow. The results indicate that the modified vortex elbow can generate a stable axial gas vortex, leading to periodic particle flow. Through particle collisions and the formation of an accumulation layer within the vortex chamber, particle-wall impacts are transformed into particle-particle collisions, thereby significantly reducing erosion. Xu et al. [25] combined the CFD-DEM method with a coarse-grained approach to develop a wear prediction model suitable for dilute-phase gas–solid flows. Applying this model to simulate elbow erosion wear significantly enhances computational efficiency.

In recent years, advancements in materials science have enabled composites to demonstrate superior corrosion resistance compared to traditional metallic materials. Miyazaki and Hamao [26] investigated the effect of fiber content and type on the erosion resistance of thermoplastic resins by subjecting the material surfaces to solid particle impact. Their results demonstrated that short fibers significantly enhance the erosion resistance of thermoplastic resins, with both fiber content and type exerting a considerable influence on performance. Bagci and Imrek [27] studied epoxy resin composites filled with boric acid reinforced glass fibers. The results revealed that the addition of boric acid reduced the corrosion resistance of the epoxy-based composites. Purohit et al. [28,29,30] investigated the influence of various fillers or fibers on the properties of polymer composites. A consistent finding across these research was the improvement in hardness and erosion wear resistance of the composite materials with the incorporation of fillers or fibers. Specifically, Linz-Donawitz sludge in polypropylene enhanced these properties. Conversely, the tensile and flexural strengths often exhibited a marginal decrease or an optimal value at intermediate filler loadings. Pradhan et al. [31] demonstrated that the incorporation of coconut shell dust as a filler enhanced the erosion wear resistance of epoxy composites, with erosion rate being predominantly influenced by erodent size, impingement angle, and impact velocity.

Piping systems are widely used in industrial sectors such as petrochemical and nuclear power to transport corrosive media—for instance, acidic gases in natural gas or boric acid coolant in nuclear reactors—which can induce chemical corrosion within the tubes. In addition, pipelines are subject to erosion wear caused by solid particles, with elbows experiencing particularly severe wear, reported to be up to 50 times greater than that in straight sections [18]. Specifically, elbow erosion typically occurs under high-pressure gas–solid two-phase flow conditions, with operating pressures ranging from approximately 2.6 MPa to 15.5 MPa. The conveying medium is often natural gas such as methane, containing fine spherical solid particles around 0.4 mm in diameter with a volume fraction generally below 0.08, indicating a dilute suspension [18]. Such a significant discrepancy not only threatens the structural integrity of the piping system but also compromises the safety of fluid transport. Composite materials, known for their superior corrosion resistance, can be applied as linings or coatings to protect pipelines. It is therefore essential to investigate the erosion mechanisms of composite elbows under gas–solid two-phase flow conditions and to evaluate their feasibility for engineering applications. This study focuses on modeling the erosion wear of elbows made from zinc oxide-modified bidirectional E-glass fiber-reinforced epoxy resin composites (hereinafter referred to as ZnO-BE-GFRP) and examines their erosion wear characteristics under various operating conditions. The ZnO-BE-GFRP (FZ16) composite consists of 55 wt.% bidirectional E-glass woven fabric, 29 wt.% epoxy resin (L285), and 16 wt.% zinc oxide nanoparticles. It was fabricated via a vacuum-assisted hand lay-up process: the filler was first mechanically stirred into the epoxy resin, followed by mixing with the hardener. Twenty layers of fabric were laid up in a 0/90° orientation with resin applied layer-by-layer, and the laminate was subsequently vacuum degassed and cured [32].

2. Mathematical Model and Numerical Method

2.1. Model of Particles

The translational and rotational motions of particles are described using Newton’s laws of motion as shown in Equations (1) and (2):

where m is the mass of the particle, dv/dt is the translational acceleration of the particle, dω/dt is the rotational acceleration of the particle, Fc is the contact force, Fb is the buoyancy, Fd is the drag force, FlM is the Magnus lift force, FlS is the Saffman lift force, I is the moment of inertia, Tc is the contact torque exerted on particle, Tf is torque from fluid. The formula for calculating buoyancy Fb is shown in Equation (3).

In the formula, Vp represents the volume of a single particle and ρf represents the density of the fluid. According to the linear elastic damping model proposed by Cundall et al. [33], the contact force Fc between particles is derived from Equations (4)–(6).

In the formula, Fc,t,ij is the tangential impact force between the particle and the wall. Fc,n,ij is the normal impact force between the particle and the wall. kt and kn are the tangential spring stiffness and the normal spring stiffness, respectively. δt and δn are the tangential displacement and the normal displacement, respectively. ηt and ηn are the tangential damping coefficient and the normal damping coefficient, respectively. vt,ij is the tangential relative velocity between the particle and the material surface; vn,ij is the normal relative velocity between the particle and the surface of the material. The method for calculating the damping coefficient is detailed in the study by Ting et al. [34]. When the tangential contact force and the normal contact force satisfy the relationship shown in Equation (7), Fc,t,ij can be calculated according to Equation (8):

where fs is the coefficient of sliding friction. The tangential torque of spherical particles Tc,ij can be calculated by Equation (9):

where r is the radius of the spherical particle and n is the unit normal vector.

2.2. Model of Fluid

Fluid motion is solved using the continuity equation and the momentum conservation equation. The fluid density is assumed constant. The fluid continuity equation and the momentum control equation are calculated by Equation (10) and Equation (11), respectively.

where u represents fluid velocity, p represents fluid pressure, x represents coordinate position, and μeff represents effective viscosity. The term Fs signifies the momentum exchange source from the particles to the fluid, adhering to Newton’s third law. Meanwhile, αf is the fluid volume fraction, which is calculated by Equation (12):

Vp,i is the volume occupied by the i-th particle sub-element within the CFD cell, n designates the total count of these sub-elements residing in the same cell, and Vcell is the total volume of the computational cell.

2.3. CFD-DEM Coupling Model

The drag force on the particles is calculated using the Di Felice model [35], which is calculated by Equation (13):

where dp is the particle diameter, v is the particle velocity, CD is the drag force coefficient, and the resistance coefficient of spherical particles is calculated as shown in Equation (14):

The Reynolds number Rep,α for the resistance of the particle is given by Equation (15):

where μf is the viscosity of the fluid. The coefficient γ in Equation (13) is calculated by Equation (16):

In a tubular flow system, when the translational and rotational speeds of the particles are relatively large, the lift force generated by the particle rotation and shear flow movement needs to be considered. The Magnus lift generated by the rotation of particles FlM can be calculated by Equation (17):

According to Oesterle and Dinh [36], the Magnus lift force coefficient ClM can be derived from Equation (18):

where Rep and Rer are the Reynolds numbers for the Magnus force and particle rotation, respectively, calculated by Equations (19) and (20). with ωp being the particle’s angular velocity. The Saffman lift force resulting from shear flow motion FlS is calculated by Equation (21):

According to Mei [37], the Saffman lift force coefficient ClS can be calculated by Equation (22):

where Rep is the Reynolds number of the Saffman lift on the particle, calculated in the same way as Equation (19). Also, ωf in Equation (21) is the angular velocity of the fluid, which is given by Equation (23), with the coefficient β of Equation (22) is calculated by Equation (24):

According to the research of Rubinow and Keller [38], the torque produced by the rotation of the particle Tf can be derived from Equation (25):

The rotational torque coefficient CR can be obtained from direct numerical simulations by Dennis et al. [39]. As shown in Equation (26).

The forces that particles exert on the fluid are given by Equation (27) in accordance with Newton’s third law:

where n corresponds to the number of sub-elements present in the cell, and a smoothing algorithm was employed for stability assurance [40].

2.4. Wear Model

This paper proposes a novel wear model for predicting the erosion of ZnO-BE-GFRP, based on both tangential and normal impact energy. The core concept involves first determining the specific energy for cutting wear and the specific energy for normal wear of the material. The tangential and normal energy components acting on the material surface are then computed using the CFD-DEM method, enabling the separate quantification of wear due to cutting and deformation mechanisms. The model is applicable to scenarios involving both abrasive and deformable wear. Following the approach of Zhao et al. [11], the tangential impact energy Et of particles acting on the material surface is given by Equation (28), and the normal impact energy En is calculated in the same form as the tangential impact energy

where vij is the velocity between the particle and the surface of the material. t0 is the start time of the impact. t1 is the ending time of the impact. It should be noted that the tangential impact energy Et is converted to wear only when the condition and are satisfied. Since composites differ from traditional plastic and brittle materials, both cutting wear and deformation wear should be taken into account when calculating wear, and the volume W of material carried away by particles when impacting the surface of the material is calculated by Equation (29):

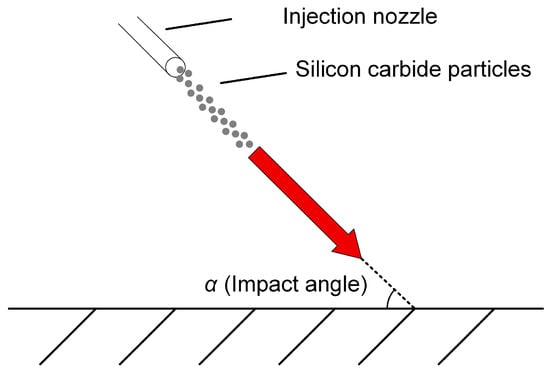

where et and en are, respectively, the specific energy for cutting wear and the specific energy for deformation wear, physically meaning the impact energy required for each unit volume of material to be worn. The values of both are related to the type of material. This study is calibrated based on the ZnO-BE-GFRP data provided by Öztürk et al. [32], with simulation parameters summarized in Table 1. The manner of particle impact on the composite plate is shown in Figure 1. The specific energy for deformation wear (en) was determined from the wear rate at an impact angle of 90°. The specific energy for cutting wear (et) was subsequently obtained by averaging the wear rates at four impact angles: 20°, 30°, 45°, and 60°. The wear rate is calculated by Equation (30)

Here, ρm represents wall the density of the composites, qm is particle mass flow rate, and t is the impact time of the particles.

Table 1.

Simulation parameters used to build the wear model.

Figure 1.

Impact of silicon carbide particles on a composite plate.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Validation of Erosion Wear Model Proposed

First, the accuracy of the new wear model proposed in this paper is validated for ZnO-BE-GFRP [32]. The DEM was employed to simulate the impact of silicon carbide particles on ZnO-BE-GFRP at various impact angles. The simulation parameters, listed in Table 1, were configured in accordance with the experimental conditions established by Öztürk et al. [32]. Note that in all simulations, particles are assumed not to undergo fracture or wear themselves. The impact angle was initially set to 90° to allow the particle stream to strike the composite sample, thereby determining the specific energy for deformation wear en (J/mm3). Subsequently, based on the impact energy at lower angles (20–60°), the corresponding specific energy for cutting wear was derived for each of the four angle intervals. The average of these values was taken to obtain the specific energy for cutting wear et (J/mm3). As detailed in Equation (31).

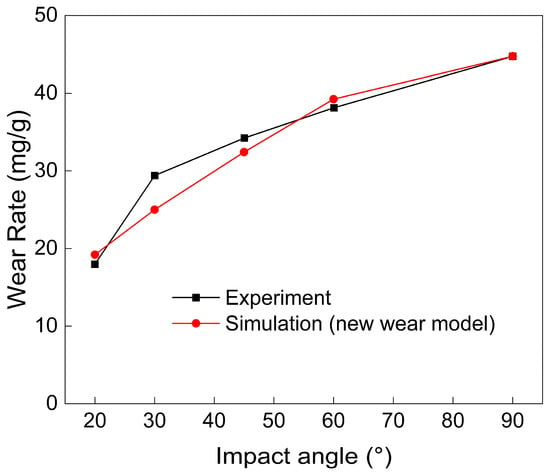

The wear rates corresponding to each impact angle were obtained using the new wear model combined with the DEM method and compared with experimental results, as shown in Figure 2. The results indicate that the new wear model underestimates the wear rate at an impact angle of 30°, while its predictions for the other four angles agree closely with experimental data. The specific energy for cutting wear at a 30° impact angle is lower than the average value across all angles except vertical impact, indicating that less energy is required to remove a unit volume of material at this angle. Consequently, the actual wear exceeds the predicted value obtained using the average specific energy. According to Zhao et al. [11], the tangential impact energy exhibits a nonlinear relationship with the impact angle, initially increasing and then decreasing. This suggests that the material is most susceptible to cutting wear near 30°, resulting in an actual specific energy for cutting wear that is lower than the average value. Since the specific energies derived from experiments at other angles deviate only slightly from the mean, the model predictions generally align well with the experimental outcomes. In the following section, the erosion wear of composite elbows under various operating conditions will be investigated to further analyze their wear behavior.

Figure 2.

Comparison of experimental results with simulation results.

3.2. Solution and Simulation Conditions

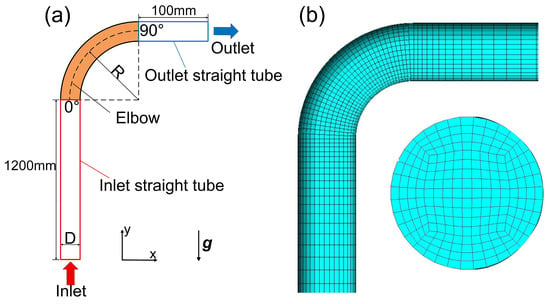

The geometry and mesh of the elbow model are shown in Figure 3a,b. It should be noted that a grid independence study was already performed and validated in a prior publication [25]. Thus, it is omitted from the present discussion. This study focuses on the erosion wear in a 90° elbow induced by a dilute gas–solid two-phase flow. The initial gas velocity was set to 45.72 m/s. Due to the high gas velocity, the Reynolds number of the gaseous flow field was correspondingly high. Therefore, the SIMPLEC algorithm was employed to solve the gas-phase governing equations, and the QUICK differencing scheme was selected for discretizing the convective terms. The flow field was computed using a pressure-based implicit solver. The solid phase was simulated using an in-house developed code, and gas–solid coupling was implemented through user-defined functions. The motion of solid particles in the DEM was resolved using an explicit time integration method.

Figure 3.

Elbow geometry model and mesh: (a) geometry model; (b) mesh.

Owing to the limited availability of experimental data on erosion wear in composite elbows, all parameters other than the intrinsic material properties of the elbow were configured with reference to the experimental work of Chen et al. [41]. The computational domain was divided into three sections: the inlet straight tube, the elbow, and the outlet straight tube. Air enters through the inlet section at a velocity of 45.72 m/s. Sand particles are introduced with a mass flow rate of 0.000208 kg/s. The gas–solid two-phase flow passes through the elbow and exits via the outlet straight tube. The mesh configuration is illustrated in Figure 3b. To accurately capture wear distribution within the elbow region, the local mesh volume was refined to a size ranging from 3.5 × 10−9 m3 to 7 × 10−9 m3. For computational efficiency, the inlet velocity was simplified by setting a fluctuation velocity of 2.7 m/s, and the initial particle velocity was uniformly specified as 2.5 m/s. Turbulence effects on the time-averaged flow field were modeled using the standard k–ε turbulence model. The turbulent kinetic energy k and turbulent dissipation rate ε were determined as 4.77 m2/s2 and 963 m2/s3, respectively, based on the inlet Reynolds number and the expected turbulence length scale. The remaining parameters are provided in Table 2, with the DEM simulation time step set to 1.5 × 10−7 s.

Table 2.

Simulation parameters for the composite elbow.

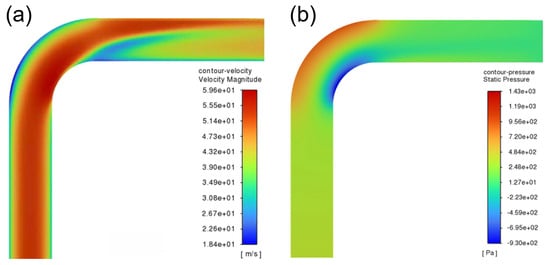

3.3. Effects of Different Air Velocities on Composite Elbow Wear Rate

As observed in Figure 4a, a distinct low-speed zone appears at the extrados. a distinct low-velocity region is present near the extrados. Simultaneously, another low-velocity zone forms along the intrados surface. This flow behavior can be explained by the pressure distribution illustrated in Figure 4b, which shows a low-pressure zone at the intrados surface. This pressure deficit induces flow recirculation, resulting in the formation of the low-velocity region.

Figure 4.

Flow field characteristics at a gas velocity of 45.72 m/s: (a) velocity distribution; (b) pressure distribution.

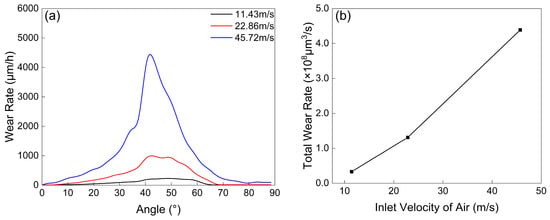

As shown in Figure 5a,b, the erosion wear of the extrados and total wear rate increases notably with rising gas velocity, and areas of higher wear also exhibit a circumferential expansion (Figure 6). Compared with the findings of Xu et al. [25], at a gas velocity of 45.72 m/s, the wear rate of the composite elbow was significantly higher than that of the aluminum elbow. Interestingly, even when the particle mass flow rate for the aluminum elbow was 100 times greater than that for the composite elbow, the maximum wear at the extrados was similar between the two materials. This behavior can be attributed to the substantial difference in their specific wear energies. The cutting wear energy for aluminum is 4.33 J/mm3, whereas it is only about 0.183 J/mm3 for the composite.

Figure 5.

Comparison between localized and total wear rates on the extrados of the elbow: (a) distribution of localized wear rates across the extrados; (b) total wear rate of the entire elbow. Results are shown for gas velocities of 45.72, 22.86, and 11.43 m/s.

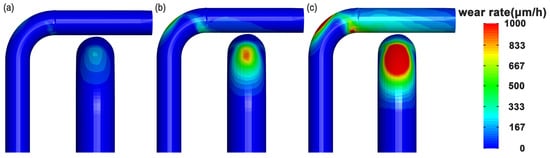

Figure 6.

Erosion wear distribution on the extrados of the elbow at different gas velocities: (a) 11.43 m/s, (b) 22.86 m/s, (c) 45.72 m/s.

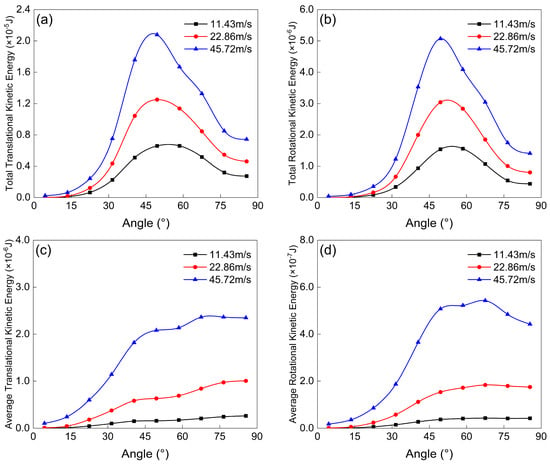

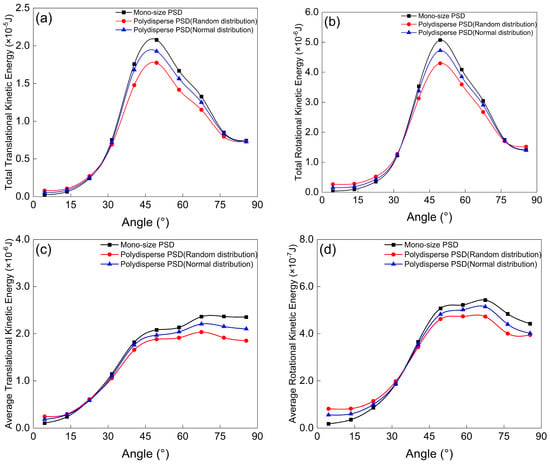

It should be noted that the total kinetic energy of particles, as defined in this study, refers to the combined translational and rotational kinetic energy of particles in the near-wall region of the extrados per unit time. As shown in Figure 7a,b, both the translational and rotational kinetic energy of particles near the extrados wall increase with rising gas velocity. The peaks of translational and rotational kinetic energy occur within the angular range of 40° to 60°, which also corresponds to the location of maximum erosion wear in the elbow.

Figure 7.

Distribution of near-wall particle kinetic energy on the extrados across different gas velocities: (a) total translational kinetic energy; (b) total rotational kinetic energy; (c) average translational kinetic energy; (d) average rotational kinetic energy.

In this study, the average translational kinetic energy and average rotational kinetic energy are calculated as the arithmetic mean of the total translational and rotational kinetic energies of particles within the corresponding intervals. As shown in Figure 7c, the average translational kinetic energy of particles within the 0–50° region increases significantly with gas velocity. Notably, at all three gas velocities, the rate of increase in average translational kinetic energy declines markedly around the 45° position. This phenomenon may be attributed to two main factors: first, a large number of particles collide with the extrados within the 40–60° region, resulting in a loss of kinetic energy. Second, some particles migrate toward the extrados within the elbow section, and the deviation between the particle motion direction and the airflow direction reduces the translational kinetic energy transferred from the gas to the particles. Figure 7d illustrates the distribution of the average rotational kinetic energy, indicating that the increase in rotational kinetic energy becomes more pronounced as the gas velocity rises. Notably, the growth rate of the average rotational kinetic energy within the 0–50° region significantly accelerates under higher gas velocities.

Based on the foregoing analysis, it is evident that the degree of erosion wear in the 90° elbow is positively correlated with the magnitude of the gas velocity. The region between 40° and 50° along the extrados is subjected to more severe wear. Furthermore, as the gas velocity increases, the zones of elevated wear exhibit a shift further into the elbow section. Additionally, an approximately linear relationship is observed between the gas velocity and the wear amount on the elbow.

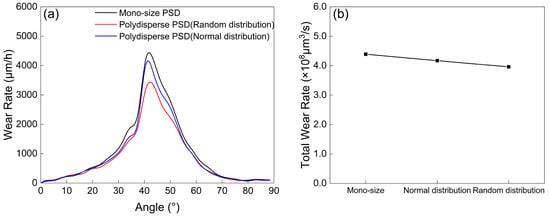

3.4. The Effect of Particle Size Distribution on the Wear Rate of the Elbow

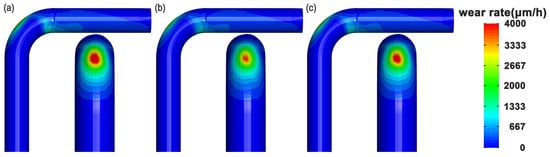

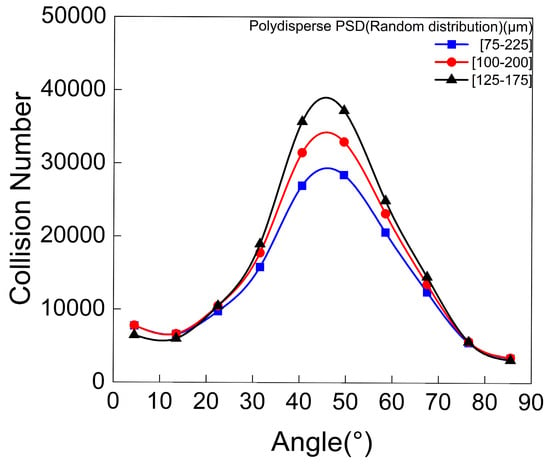

In practical engineering applications, the particle sizes responsible for erosion wear are never perfectly uniform. Accordingly, this section investigates the influence of sand particle size distribution (PSD) on the erosion wear characteristics of composite elbows. For the mono-dispersed case, a uniform particle size of 150 μm was used. Normal and random distributions were set within the range of 100–200 μm. In all cases, the particle mass flow rate was maintained constant at 0.000208 kg/s. As illustrated in Figure 8a, wear at the extrados under the random distribution is less severe compared to both the mono-dispersed and normal distributions, with the highest wear occurring under the mono-dispersed condition. Figure 8b shows that the total wear rate at the elbow decreases as the particle size distribution becomes more dispersed.

Figure 8.

Comparison between localized and total wear rates of the elbow under different particle sizes: (a) distribution of localized wear rates across the extrados; (b) total wear rate of the entire elbow.

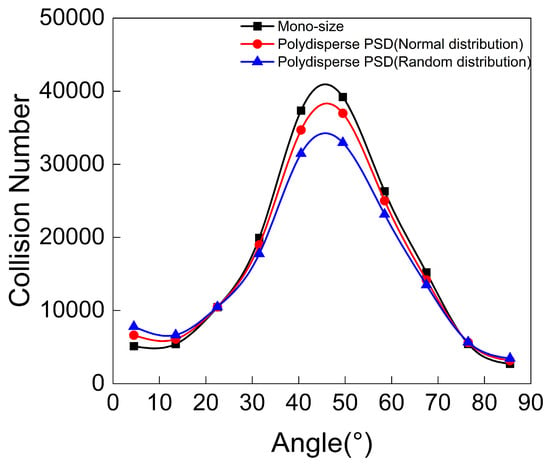

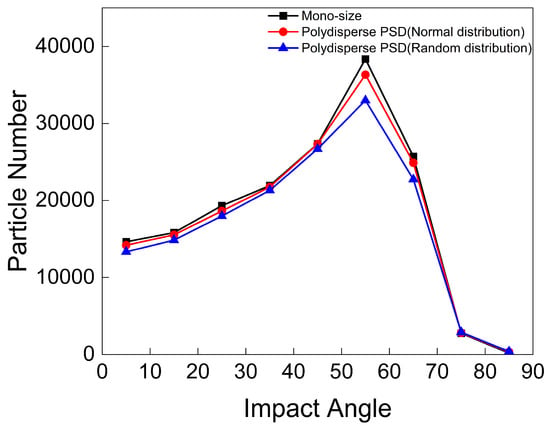

Figure 9 shows the number of particle impacts on the extrados for the three particle size distributions. It can be observed that as the particle size distribution becomes more concentrated, impacts within the 40–50° region of the extrados occur more frequently. This region also experiences the most severe wear. Furthermore, as indicated in Figure 10, the number of particles impacting at 60° is lower under the random distribution compared to the other distributions. According to Equation (31), the calibrated specific energy for deformation wear is lower than that for cutting wear, which indicates that the new wear model is more sensitive to deformation wear. Consequently, particles impinging at high impact angles cause more significant wear. Thus, under the random distribution, both the total number of impacts and the number of high-angle impacts on the extrados are reduced, resulting in the least wear among the three cases.

Figure 9.

Comparison of collision frequency with the extrados for mono-size PSD, random distribution, and normal distribution.

Figure 10.

Comparison of particle impact Angle distribution near the extrados among mono-size PSD, Random distribution, and Normal distribution.

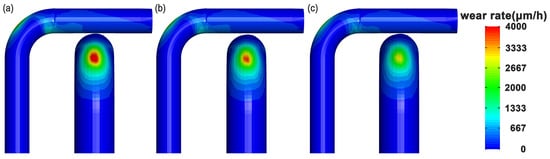

The wear distributions on the extrados for the three particle size conditions are presented in Figure 11. The results demonstrate that more concentrated particle sizes lead to more severe wear within the 40–50° region. It is also noted that under more concentrated particle sizes, circumferential connectivity emerges in the wear zone near the outlet end of the elbow, indicating enhanced circumferential wear.

Figure 11.

Erosion wear distribution on the extrados under different particle size conditions: (a) mono-size PSD; (b) random distribution; (c) normal distribution.

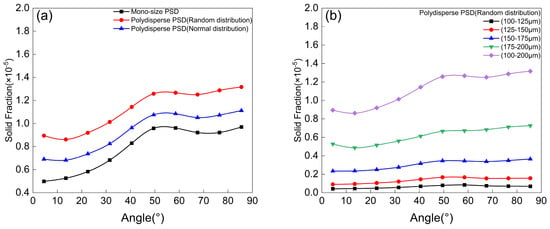

As shown in Figure 12a, the solid volume fraction within the elbow is positively correlated with the degree of particle size dispersion. A statistical analysis of the solid volume fraction under the random particle size distribution was conducted, and the results are presented in Figure 12b. It can be observed that in multi-sized particle conditions, large particles contribute the majority of the solid volume fraction. Statistical results indicate that the ratio of the solid volume fraction between large and small particles is significantly greater than their numerical ratio for an equal number of particles. This suggests that the number of large particles within the elbow is substantially higher than that of small particles. According to Figure 9, this phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that although the solid volume fraction increases, large particles may exhibit fewer impacts on the extrados, resulting in comparatively less wear.

Figure 12.

Solid volume fraction in the elbow: (a) different types of PSD; (b) different size distribution ranges under random distribution.

As shown in Figure 13a,b, the total kinetic energy of particles near the extrados is inversely proportional to the degree of particle size dispersion. It is inferred that as the particle size distribution broadens, the number of small particles increases. These smaller particles are more likely to follow the gas flow and may exit the elbow without colliding with the wall. This behavior results in a reduction in the number of particle impacts on the extrados under random distributions (Figure 9), which may account for the decreased wear observed in this region. According to Equation (28), the impact energy of the particles strongly influences both the tangential and normal kinetic energy components, which in turn govern the wear process. Consequently, under mono-dispersed particle conditions, the total kinetic energy of the particles reaches its maximum, leading to the most severe wear on the extrados.

Figure 13.

Distribution of near-wall particle kinetic energy on the extrados for mono-dispersed, randomly distributed, and normally distributed particle sizes: (a) translational kinetic energy; (b) rotational kinetic energy; (c) average translational kinetic energy; (d) average rotational kinetic energy.

As shown in Figure 13c, the average translational kinetic energy of particles in the region corresponding to the latter half of the extrados (67–85°) remains relatively stable. In conjunction with Figure 9, it can be observed that the number of particle collisions within this interval is limited, indicating restrained kinetic energy transfer to the wall. Furthermore, as illustrated in Figure 11, particles contribute to wear on the curved surface within the outlet straight tube section. Figure 13d demonstrates that the average rotational kinetic energy is higher within the 50–67° range. When correlated with Figure 9 and Figure 10, this suggests frequent particle collisions occurring in this region, predominantly through oblique impacts, which leads to elevated average rotational kinetic energy within the interval.

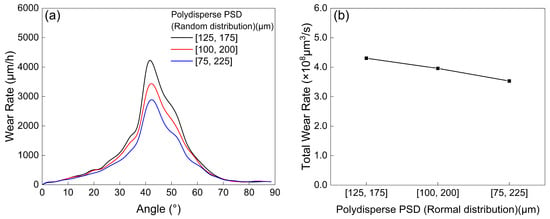

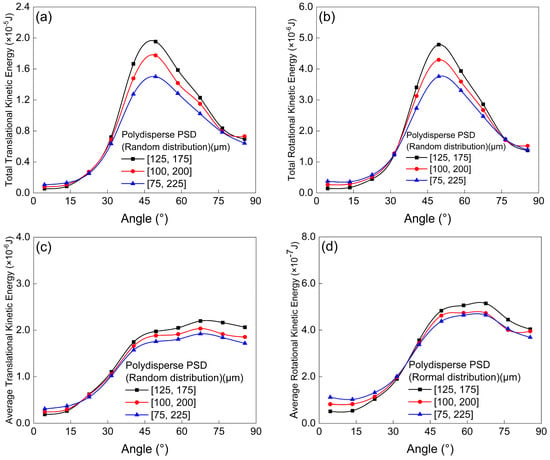

A further quantitative analysis was conducted to investigate the effect of particle size distribution range on the erosion wear of the elbow. Three particle size intervals were considered: 125–175 μm, 100–200 μm, and 75–225 μm, all following a random distribution. As shown in Figure 14a and Figure 15, the wear rate at the extrados decreases as the range of the random particle size distribution increases. This observation is consistent with the earlier finding that more concentrated particle sizes lead to more severe wear on the extrados. indicates that the number of particle impacts on the extrados decreases with increasing particle size dispersion. These results confirm that the reduction in particle collisions within the 40–50° region of the extrados with increased particle dispersion remains valid even under approximately uniform distribution across particle sizes (Figure 16). As illustrated in Figure 17a,b, the total translational and rotational energy exhibit a negative correlation with the particle size distribution range, consistent with the trend observed in Figure 13a,b. Additionally, Figure 17c,d show that the distribution patterns of the average translational and rotational energy are essentially consistent with those observed under different particle size distribution modes (Figure 13c,d).

Figure 14.

Comparison between localized and total wear rates of the elbow under polydisperse PSD (random distribution): (a) Distribution of localized wear rates across the extrados; (b) Total wear rate of the entire elbow.

Figure 15.

Erosion wear distribution on the extrados for random distribution with different ranges: (a) 125–175 μm; (b) 100–200 μm; (c) 75–225 μm.

Figure 16.

Comparison of collision number with the extrados for random distribution.

Figure 17.

Distribution of particle kinetic energy near the wall of elbow with random distribution: (a) translational kinetic energy; (b) rotational kinetic energy; (c) average translational kinetic energy of particles; (d) average rotational kinetic energy of particles.

In summary, greater dispersion of the particle size range leads to reduced wear at the extrados. This effect can be primarily attributed to the increased proportion of small particles under more dispersed distributions. Owing to their stronger ability to follow the gas flow, a larger number of small particles exit the elbow directly without colliding with the extrados. As a result, not only are the total number of impacts reduced, but the number of particles striking the extrados at high impact angles also decreases. Since high-angle impacts are associated with more severe deformation wear, this dual reduction in both impact frequency and critical impact events collectively contributes to the overall decrease in erosion.

4. Conclusions

This study investigates the erosion wear mechanism of ZnO-BE-GFRP elbows under gas–solid two-phase flow conditions. A predictive model for erosion wear applicable to this composite was developed, and the effects of various operational conditions on wear characteristics were systematically analyzed. The main conclusions are as follows:

1. An erosion wear model specifically to ZnO-BE-GFRP was developed and validated against experimental data. The ZnO-BE-GFRP elbow exhibits higher susceptibility to wear compared to aluminum elbows. Particles predominantly impact the 40–50° region of the extrados, which experiences the most severe wear.

2. Increased gas velocity significantly increases wear on the extrados of the elbow. Based on the current data, in general, as gas velocity increases, the wear region tends to expand toward the central extrados, with the total wear rate showing an overall linear growth trend. At a gas velocity of 45.72 m/s, the peak wear rate at the extrados is 19.3 times higher than that at 11.28 m/s.

3. Under consistent mass flow conditions, greater dispersion in particle size leads to a larger proportion of fine particles, which more closely follow the fluid stream and exit the elbow without impacting the extrados. Concurrently, the number of high-angle impacts on the extrados is reduced. These combined effects result in decreased overall wear in the extrados.

The current wear model has two main limitations. First, its parameters are calibrated based on experimental data from a specific epoxy-based composite material, and its applicability has not yet been extended to other material systems. Second, the model is constructed based on the assumption of dilute-phase flow, making it difficult to accurately predict wear behavior under high-concentration dense-phase flow conditions. These limitations stem from the model’s reliance on specific material data and its simplified treatment of inter-particle interactions.

Future research will further investigate the wear mechanisms of composite materials and develop wear models suitable for dense-phase flows, with a focus on exploring their application as protective coatings to mitigate pipeline erosion, thereby enhancing the model’s engineering applicability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.X., S.B. and Y.Z.; methodology, L.X., S.B., X.D. and Y.Z.; software, L.X.; validation, Y.S.; formal analysis, L.X.; investigation, L.X., Y.S. and X.Z.; resources, L.X.; data curation, Y.S.; writing—original draft preparation, L.X. and Y.S.; writing—review and editing, L.X. and Y.Z.; visualization, Y.S. and X.C.; supervision, L.X., S.B., X.D. and Y.Z.; project administration, L.X.; funding acquisition, L.X. and X.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, Grant No. 52205172 and 52075489), the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. LY23E050015 and No. LTGS24E010002).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| DEM | Discrete Element Method |

| DPM | Discrete Phase Model |

| ZnO-BE-GFRP | zinc oxide-modified bidirectional E-glass fiber-reinforced epoxy resin composites |

| PSD | particle size distribution |

References

- Peng, W.; Cao, X. Numerical Prediction of Erosion Distributions and Solid Particle Trajectories in Elbows for Gas–Solid Flow. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2016, 30, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Luo, K.; Zhao, Y.; Fan, J.; Cen, K. Multiscale Investigation of Tube Erosion in Fluidized Bed Based on CFD-DEM Simulation. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2018, 183, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhondizadeh, M.; Fooladi Mahani, M.; Rezaeizadeh, M.; Mansouri, S. Prediction of Tumbling Mill Liner Wear: Abrasion and Impact Effects. J. Eng. Tribol. 2016, 230, 1310–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wen, J.; Li, H.; Xia, Y.; Tan, S.; Xiao, H.; Duan, W.; Hu, J. Particle Erosion in 90-Degree Elbow Pipe of Pneumatic Conveying System: Simulation and Validation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 216, 108534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnie, I. Erosion of Surfaces by Solid Particles. Wear 1960, 3, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitter, J.G. AA Study of Erosion Phenomena. Wear 1963, 6, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neilson, J.H.; Gilchrist, A. Erosion by a Stream of Solid Particles. Wear 1968, 11, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, G.; Tabakoff, W. An Experimental Investigation of the Erosive Characteristics of 2024 Aluminum Alloy; The University of Cincinnati: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Oka, Y.I.; Okamura, K.; Yoshida, T. Practical Estimation of Erosion Damage Caused by Solid Particle Impact. Wear 2005, 259, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, Y.I.; Yoshida, T. Practical Estimation of Erosion Damage Caused by Solid Particle Impact. Wear 2005, 259, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Ma, H.; Xu, L.; Zheng, J. An Erosion Model for the Discrete Element Method. Particuology 2017, 34, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Reuterfors, E.P.; McLaury, B.S.; Shirazi, S.A.; Rybicki, E.F. Comparison of Computed and Measured Particle Velocities and Erosion in Water and Air Flows. Wear 2007, 263, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njobuenwu, D.O.; Fairweather, M. Modelling of Pipe Bend Erosion by Dilute Particle Suspensions. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2012, 42, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tan, R.; Chang, B.; Chen, B.; Li, J.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, T. Simulation of Elbow Erosion of Gas–Liquid–Solid Three-Phase Shale Gas Gathering Pipeline Based on CFD-DEM. Processes 2024, 12, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patankar, N.A.; Joseph, D.D. Modeling and Numerical Simulation of Particulate Flows by the Eulerian–Lagrangian Approach. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2001, 27, 1659–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, Y.; Kawaguchi, T.; Tanaka, T. Discrete Particle Simulation of Two-Dimensional Fluidized Bed. Powder Technol. 1993, 77, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Cao, X. Numerical Simulation of Solid Particle Erosion in Pipe Bends for Liquid–Solid Flow. Powder Technol. 2016, 294, 266–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.; Lan, H.; Xu, Y.; Dong, S.; Barber, G. Effect of the Gas–Solid Two-Phase Flow Velocity on Elbow Erosion. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2015, 26, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohebi, A.R.; Najafi, F.; Mozaffarian, M.; Dabir, B.; Esmaeilian Amrabadi, N. Fluid Dynamics and Erosion Analysis in Industrial Naphtha Reforming: A CFD-DPM Simulation Approach. Powder Technol. 2024, 436, 119417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; He, R.; Han, S.; Chen, Y. Erosion Prediction of Liquid-Particle Two-Phase Flow in Pipeline Elbows via CFD–DEM Coupling Method. Powder Technol. 2015, 275, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Ma, H.; Sun, Z. Simulation of Two-Phase Flow of Shotcrete in a Bent Pipe Based on a CFD–DEM Coupling Model. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Cheng, K.; Sun, W.; Zhao, Y. Study on Pumping Wear Characteristics of Concrete Pipeline Based on CFD-DEM Coupling. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyralvand, D.; Banazadeh, F.; Moghaddas, R. Numerical Investigation of Novel Geometric Solutions for Erosion Problem of Standard Elbows in Gas-Solid Flow Using CFD-DEM. Results Eng. 2023, 17, 101014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Luo, M.; Huang, F.; Zhou, M.; An, J.; Kuang, S.; Yu, A. CFD–DEM Investigation of Gas-Solid Flow and Wall Erosion of Vortex Elbows Conveying Coarse Particles. Powder Technol. 2023, 424, 118524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Chen, X.; Wu, X.; Liang, J.; Bao, S.; Zheng, Q. Coarse-Grained CFD-DEM Simulation of Elbow Erosion Induced by Dilute Gas-Solid Flow: A Multi-Level Study. Powder Technol. 2024, 443, 119916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, N.; Hamao, T. Solid Particle Erosion of Thermoplastic Resins Reinforced by Short Fibers. J. Compos. Mater. 1994, 28, 871–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagci, M.; Imrek, H. Solid Particle Erosion Behaviour of Glass Fibre Reinforced Boric Acid Filled Epoxy Resin Composites. Tribol. Int. 2011, 44, 1704–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purohit, A.; Dehury, J.; Rout, L.N.; Pal, S. A Novel Study of Synthesis, Characterization and Erosion Wear Analysis of Glass–Jute Polyester Hybrid Composite. J. Inst. Eng. India Ser. E 2023, 104, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purohit, A.; Gupta, G.; Pradhan, P.; Agrawal, A. Development and Erosion Wear Analysis of Polypropylene/Linz-Donawitz Sludge Composites. Polym. Compos. 2023, 44, 6556–6565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purohit, A.; Satapathy, A.; Swain, P.T.R. Analysis of Erosion Wear Behavior of LD Sludge Filled Polypropylene Composites Using RSM. Mater. Sci. Forum 2020, 978, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, P.; Purohit, A.; Mohanty, I.; Jena, H.; Sahoo, B.B. Erosion Wear Analysis of Coconut Shell Dust Filled Epoxy Composites Using Computational Fluid Dynamics and Taguchi Method. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2023, 237, 5653–5662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, B.; Gedikli, H.; Kılıçarslan, Y.S. Erosive Wear Characteristics of E-Glass Fiber Reinforced Silica Fume and Zinc Oxide-Filled Epoxy Resin Composites. Polym. Compos. 2020, 41, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cundall, P.A.; Strack, O.D.L. A Discrete Numerical Model for Granular Assemblies. Géotechnique 1979, 29, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, J.M.; Corkum, B.T. Computational Laboratory for Discrete Element Geomechanics. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 1992, 6, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Felice, R. The Voidage Function for Fluid-Particle Interaction Systems. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 1994, 20, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oesterlé, B.; Dinh, T.B. Experiments on the Lift of a Spinning Sphere in a Range of Intermediate Reynolds Numbers. Exp. Fluids 1998, 25, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, R. An Approximate Expression for the Shear Lift Force on a Spherical Particle at Finite Reynolds Number. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 1992, 18, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinow, S.I.; Keller, J.B. The Transverse Force on a Spinning Sphere Moving in a Viscous Fluid. J. Fluid Mech. 1961, 11, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, S.C.R.; Singh, S.N.; Ingham, D.B. The Steady Flow Due to a Rotating Sphere at Low and Moderate Reynolds Numbers. J. Fluid Mech. 1980, 101, 257–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Li, T.; Ma, H.; Liu, Z.; Dong, Y.; Zhao, Y. Development and Verification of an Unresolved CFD-DEM Method Applicable to Different-Sized Grids. Powder Technol. 2024, 432, 119127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; McLaury, B.S.; Shirazi, S.A. Application and Experimental Validation of a Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD)-Based Erosion Prediction Model in Elbows and Plugged Tees. Comput. Fluids 2004, 33, 1251–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.