Abstract

Shell-and-tube heat exchangers serve as critical energy conversion equipment in marine nuclear power systems, where their thermal performance directly determines operational safety and reliability. This study proposes a kind of shark-skin bionic structure tube to enhance compactness and power density. Key findings are: (1) The microstructures induce intensive secondary flows and helical vortices, substantially disrupting the thermal boundary layer and amplifying near-wall perturbations. Maximum enhancement reaches 56.7% in heat transfer coefficient and 33.1–58.3% in heat exchange capacity, with PEC consistently maintained at 1.25–1.30. (2) Fouling deposition significantly degrades heat transfer performance. The fouling layer is simplified using a homogenized model, where the thickness reaches 0.20 mm, the heat transfer capacity of the shark-skin bionic structure tube becomes essentially equivalent to that of a smooth tube, and the heat transfer enhancement effect is largely lost. (3) This study reveals the coupling mechanism between enhanced heat exchange and fouling deposition. On a macroscopic scale, the design and manufacturing of a shark-skin bionic structure tube are achieved, laying a theoretical and design foundation for the development of a new generation of marine heat exchangers with high anti-fouling performance.

1. Introduction

As pivotal energy conversion equipment in marine nuclear power plants, the thermal performance of shell-and-tube heat exchangers directly governs the safety and reliability of the entire system. By emulating continuously evolving biological structures in nature, bionic microstructures enable significant improvements in heat transfer performance while controlling flow resistance. Nevertheless, the intricate surface morphology of bionic microstructures may concurrently elevate the risk of fouling adhesion, exacerbating the overall deposition process of particulate and crystalline fouling. Particularly in the specialized operational environment of marine nuclear power plants, this issue assumes heightened severity: upon contact with seawater, heat exchangers become susceptible to biofilm formation, thereby accelerating the progression of global fouling deposition. Hence, synergistically considering anti-fouling performance during the development of enhanced heat transfer technologies carries profound significance.

Among various bionic structures, shark skin has demonstrated outstanding potential for drag reduction and fouling inhibition due to its distinctive V-shaped riblet configurations. In recent years, researchers have actively explored this domain: Yang [1] incorporated shark-skin bionic microstructures into battery cooling channels. Compared with non-bionic designs, this configuration achieved a remarkable reduction in both the maximum temperature (by 5.49 K) and the temperature difference (by 4.11 K) of the battery module. Zhao [2] proposed a microchannel heat sink integrated with shark-skin bionic microstructures and evaluated its thermal performance under boiling conditions. The results showed that these microstructures not only increase the heat transfer area but also offer abundant nucleation sites, which promote bubble formation and growth, ultimately significantly enhancing boiling heat transfer. At 25 °C, the heat transfer coefficient of the shark-skin microchannel heat sink reached 184% of that of a plain microchannel heat sink. Similarly, Li [3] designed a single-phase plate microchannel heat sink with shark-skin bionic microstructures and numerically analyzed its thermal characteristics and entropy generation behavior under laminar flow conditions. Within the Reynolds number range of 50–250, the shark-skin microchannel demonstrated superior heat transfer performance and lower entropy generation, with the heat transfer enhancement reaching up to 210%. Wang [4] further developed a shark-skin bionic microchannel heat sink that effectively improved the thermal performance of microchannel coolers, validating this design as a feasible strategy for high-performance chip cooling.

While microstructures can greatly enhance heat transfer, they also increase the probability of fouling attachment, which may lead to the deterioration or even loss of the thermal augmentation effect. As a result, research on fouling deposition has gained increasing attention among scholars. Awais and Bhuiyan [5] reviewed the recent advancements in fouling resistance and particle deposition in heat exchangers, focusing on how operating variables (such as flow velocity, temperature, and material surface properties) influence fouling behavior. Lu et al. [6] conducted numerical simulations of particle deposition in three-dimensional ribbed heat transfer channels using the Reynolds Stress Model and Discrete Phase Model. Meanwhile, Li et al. [7,8] performed numerical analyses to address local fouling deposition in pulsating flow channels and introduced an equivalent porous media model for simulating particulate fouling. Zhang [9] adopted an integrated approach combining numerical simulation and experimental methods to analyze the deposition behavior of particulate fouling substances (such as MgO, CaSO4, CaCO3, and SiO2). Darand and Jafarian [10] developed an efficient solver based on the OpenFOAM open source platform to simulate long-term calcium carbonate scaling processes, revealing the dynamic evolution of scale and fluid-scale interactions. Oon and Kazi [11] investigated calcium carbonate deposition on titanium-coated and uncoated heat exchanger surfaces, identifying effective strategies for fouling mitigation. Han and Xu [12,13,14,15,16,17] conducted extensive research on particulate and crystallization fouling using Eulerian and Lagrangian frameworks. Their work analyzed the global and local distributions of various fouling types on enhanced heat transfer surfaces. Moreover, they constructed an experimental setup with vortex generators to examine the effects of aperture size, transverse pitch, and longitudinal pitch on fouling characteristics, providing reliable validation data for subsequent numerical simulations.

In recent years, researchers have applied shark-skin microstructures to practical scenarios such as battery cooling plates and microchannel heat exchangers, confirming the enhanced heat transfer potential of shark-skin tubes. However, most existing achievements are concentrated on small-scale heat transfer elements, which do not align with the practical application requirements of large-scale heat exchange equipment like shell-and-tube exchangers. No manufacturing scheme compatible with industrial mass production has been proposed, making it difficult for current results to provide effective guidance for industrial heat exchanger design. Meanwhile, studies related to fouling deposition primarily focus on traditional tubing, such as smooth tubes and internally threaded tubes, with a lack of research targeted at novel bionic structures. Conducting predictive studies on heat transfer capacity under the influence of fouling deposition in bionic structures holds significant importance for practical engineering applications.

Therefore, this study proposes a shark-skin bionic heat transfer tube applicable to shell-and-tube heat exchangers. Having accomplished the manufacturing process and prototype testing, the research aims to systematically investigate its enhancement effect on flow and heat transfer characteristics from a macroscopic perspective. Specifically, it analyzes the gain in heat exchange power and investigates the influence patterns of fouling deposition, thereby providing a theoretical basis and design guidance for developing next-generation marine heat exchange equipment characterized by both high efficiency and anti-fouling performance.

2. Geometric Structure and Simulation Models

2.1. Physical Models

In the context of marine nuclear power systems, shell-and-tube heat exchangers serve the purpose of cooling the primary loop water through seawater cooling circuits. To be more precise, seawater circulates within the tube side, and the primary loop water flows through the shell side. These two fluid streams are configured in a counter-current arrangement, which is a strategic design to boost thermal performance. The key operating parameters are detailed in Table 1. Specifications and simplifications of the working fluids are provided as follows:(1) The tube-side fluid is seawater, neglecting chemical influences. (2) The shell-side fluid is freshwater. (3) Both sides undergo single-phase flow without phase change. (4) The heat transfer tubes are made of titanium alloy. (5) The fouling deposit is modeled using its primary component, CaCO3.

Table 1.

Shell-and-tube heat exchanger operating parameters.

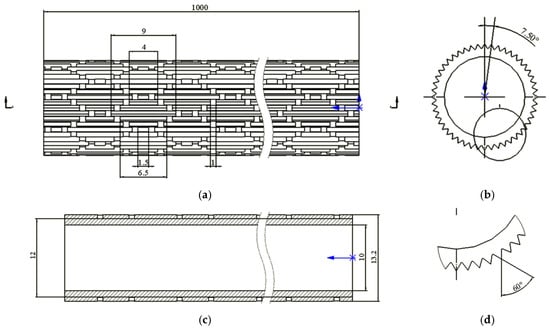

Shark-skin microstructures pertain to the riblet-like dermal denticles that coat the shark’s epidermis. These denticles are typically aligned in parallel with the local flow direction. The natural shark skin is composed of a multitude of micro-scale ridges that are oriented along the streamlines and arranged in an interlocking diamond pattern. This unique morphology plays a crucial role in effectively minimizing hydrodynamic drag. Due to this remarkable characteristic, such structures hold great promise in the fields of enhanced heat transfer. Guided by bionic principles, this research devises a heat exchange tube that integrates micro-grooves inspired by shark skin, and its geometric details are depicted in Figure 1. Four riblet dimensions (1.5 mm, 4.0 mm, 6.5 mm, and 9.0 mm) were adopted to form the shark-skin V-shaped unit cells, with a riblet interval of 1 mm. The ribs were arranged in an equilateral triangular configuration, comprising a total of 48 individual riblet units.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of shark-skin bionic structure tube: (a) Front View; (b) Side View; (c) Section View; (d) Partial View.

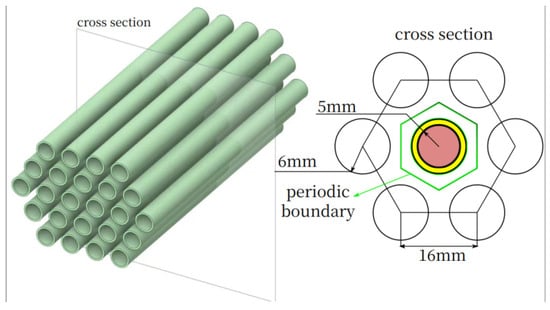

Considering that shell-and-tube heat exchangers in marine nuclear power plants usually consist of hundreds of tubes, the computational domain was streamlined. This simplification was carried out to cut down on the computational workload while still maintaining an adequate representation of the flow and heat transfer characteristics. A single heat exchange tube encircled by a hexagonal fluid zone was chosen as the representative unit. This tube has a length of 1.0 m, an inner diameter of 10 mm, and an outer diameter of 12 mm. Periodic boundary conditions were implemented to simulate the actual periodic arrangement of tubes in the heat exchanger. Separate models were constructed for the solid domain (the tube wall) and the fluid domains (the shell-side and tube-side flows). As illustrated in Figure 2, the white area represents the shell-side fluid domain, the yellow area represents the solid domain of the microstructured heat exchange tube, and the pink area corresponds to the tube-side fluid domain.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the computational domain.

Based on the established geometric model, numerical calculations were carried out by CFD software STAR-CCM+ 2402 considering the actual operating conditions of the heat exchanger. The initial and boundary conditions were configured as follows: the tube-side fluid velocity was set at 2.3 m/s with an inlet temperature range of 277.15–307.15 K, while a pressure outlet condition was applied. For the shell side, the incoming flow cross-sectional area was evenly distributed to determine the flow rate, with an inlet velocity ranging from 0.28 m/s to 0.68 m/s, and the shell-side fluid inlet temperature was specified as 319.15 K, also employing a pressure outlet setup. The SST k-ω turbulence model was utilized, with the wall boundaries configured for conjugate heat transfer conditions. The hexagonal shell side utilized periodic boundary conditions and was designated as adiabatic walls. Pressure–velocity coupling was handled using the SIMPLE algorithm, and second-order upwind schemes were applied for discretizing all governing equations. To ensure computational accuracy, convergence residuals for all equations except continuity were set below 10−6, while the residual for the continuity equation remained below 10−4.

2.2. Mathematical Equations

Before simulating the heat transfer and flow traits of the enhanced tubes, the following basic assumptions were formulated. These assumptions aim to simplify the numerical model while still maintaining its practical engineering value: (1) The working fluid is regarded as incompressible. This assumption holds true for low-speed flow situations frequently seen in heat exchange systems. (2) The flow state is assumed to be in a steady-state turbulent regime, which aligns with the operating conditions of the majority of industrial heat transfer equipment. (3) Natural convection triggered by gravitational forces is ignored because forced convection plays a dominant role in the heat transfer process. (4) Thermal radiation effects are overlooked, given the relatively low temperature range covered in this research. Based on the assumptions stated above, the governing conservation equations (including mass, momentum, and energy equations) are presented in the following form.

Equation of mass conservation:

Equation of momentum conservation:

Equation of energy conservation:

The equations defining crucial physical parameters that describe heat transfer and flow performance, such as the Reynolds number (Re), Nusselt number (Nu), friction factor (f), and performance evaluation criterion (PEC), are provided below.

2.3. Numerical Validation

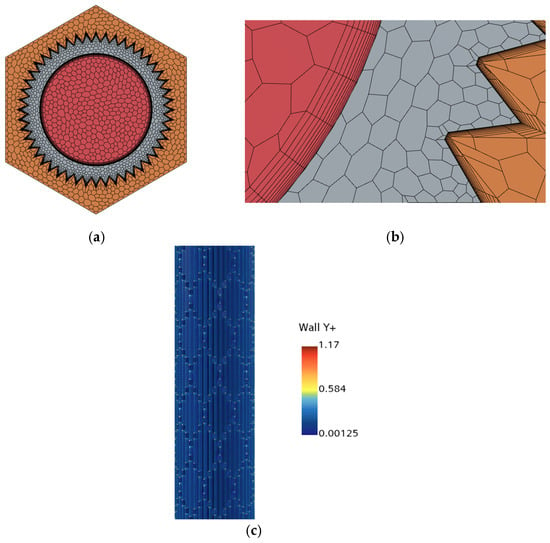

Computational meshing was performed on the model, as illustrated in Figure 3. To enhance simulation accuracy, grid refinement was applied to the shark-skin microstructure surfaces, accompanied by a grid independence study. The heat exchange power, being a primary concern in engineering applications of heat exchangers, was selected as the monitoring parameter. According to Table 2, when the mesh count increased from 2471 w to 3000 w, the variation in heat exchange power remained below 1%. Consequently, the 2471 w mesh configuration was adopted for subsequent numerical computations.

Figure 3.

Grid schematic diagram, wall Y+ distribution, with Reynolds number 11,766: (a) Grid; (b) Partial View; (c) Wall Y+.

Table 2.

Grid Sensitivity Analysis.

The SST k-ω turbulence model [18] can accurately resolve complex flows in the near-wall region without relying on wall functions. By balancing computational accuracy and efficiency, this study employs this model for numerical simulations. Under the high Reynolds number condition of Re = 11,766 considered in this work, the distribution of Y+ on the microstructured wall surface is examined. The results show that the Y+ values along the wall are predominantly below 1, which meets the resolution requirement for the viscous sublayer in the near-wall region.

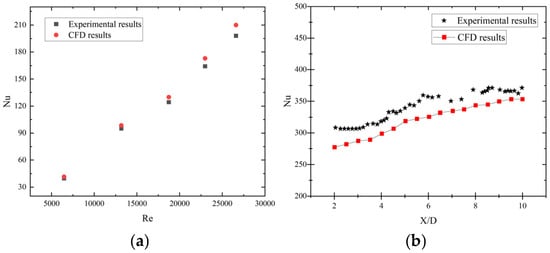

To ensure the applicability of the selected model, its validity must be verified. For this purpose, the experimental results from Kumar and Chamoli [19] were used as a reference. A corresponding physical model was established based on their experiment, and a comparative validation between simulation and experiment was conducted using an enhanced heat transfer tube with structural parameters e = 2 mm, x/d = 10, y/d = 10, and e/d = 1. The results (shown in Figure 4a) indicate that the maximum calculation error for the Nusselt number is 6.1%. Although there are certain discrepancies in the physical model, similar validation methodologies have been rigorously applied in analogous studies of related configurations, as referenced in [20,21]. To enhance the persuasiveness of the model validation, supplementary verification was conducted using experimental data from a plate heat exchanger featuring riblet structures [22]. The comparison was performed in the fully developed region (x/D > 4). The calculated results show a maximum deviation of 8.9% from the experimental data. Both errors fall within the acceptable range of engineering accuracy. This cross-verification supports the reliability of the proposed numerical framework for analyzing the flow and heat transfer characteristics within the shark-skin-inspired heat exchange tube.

Figure 4.

Comparison chart of experimental and simulation errors: (a) Pipe Flow; (b) Flat Plate Flow.

3. Analysis of Flow Heat Transfer Characteristics

3.1. Velocity Field

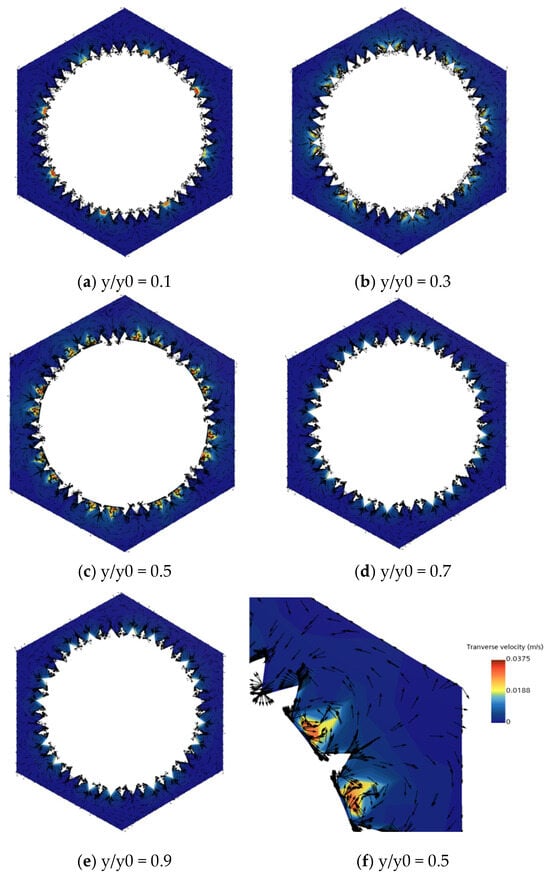

Figure 5 presents the transverse velocity profiles at axial dimensionless positions (y/y0 = 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7, 0.9) along the heat exchange tube, where y0 is the total tube length, and y is the axial coordinate. The streamlines indicate flow direction, and the contour is colored by the magnitude of transverse velocity. As shown in Figure 5a,b, the initial interaction between the microstructure and the flow induces discrete peaks in transverse velocity, generating localized small-scale vortices. However, the circumferential distribution remains discontinuous, and the main flow is still predominantly unidirectional along the axial direction. The secondary flow is in a “triggering stage.” In Figure 5c,d, the flow enters a development region, where the discrete vortices gradually merge into a circumferentially continuous band of annular vortices. The streamlines evolve from isolated disturbances into regular annular vortex patterns. The mainstream flow begins to exhibit lateral deflection (with a deflection angle of approximately 15°), and the secondary flow starts to dominate the momentum transport of the global flow field. In Figure 5e, the vortex structure stabilizes, showing no significant difference in transverse velocity magnitude compared to the development region. The streamline pattern is highly uniform, indicating that the flow has reached a dynamically balanced turbulent state, where the disturbance intensity and decay rate of the secondary flow achieve equilibrium.

Figure 5.

Tranverse velocity vector with Reynolds number 11,766.

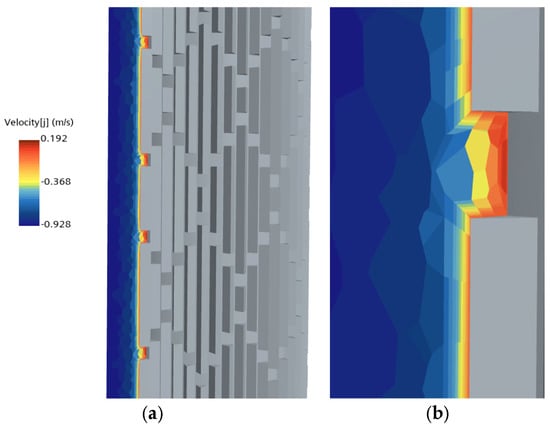

Figure 6 presents the velocity profile along the normal direction of the heat exchange tube, primarily illustrating the flow characteristics near the base of the micro-ribs. As shown, a reverse flow occurs at the base of the micro-rib structure, forming a small-scale recirculation vortex. The peak velocity at the base reaches 0.192 m/s, which is sufficient to significantly disturb the boundary layer. The formation of this reverse flow is primarily attributed to the presence of the wall microstructure, which induces periodic pressure fluctuations along the wall. A high-pressure zone develops at the leading edge of the micro-rib due to the oncoming flow, while flow separation at the trailing edge creates a low-pressure region. According to the Navier–Stokes equations, the resulting pressure gradient drives fluid from the high-pressure zone to the low-pressure zone. This process disrupts the boundary layer at the rib base, generating streamwise-oriented vortices.

Figure 6.

Axial velocity distribution with Reynolds number 11,766: (a) Velocity [j]; (b) Partial View.

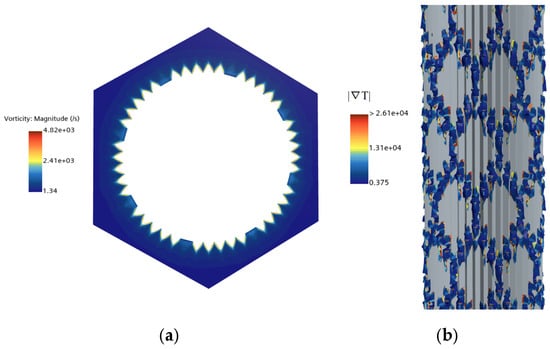

To objectively identify the structure and intensity of the secondary flow vortices, Figure 7a presents the vorticity contour plot on the axial cross-section (y/y0 = 0.5) of the bio-inspired heat exchange tube. Vorticity exhibits distinct peaks in the vicinity of the micro-ribs, reaching a maximum of 4.82 × 103 s−1. This indicates a significant enhancement in the intensity of the secondary flow vortices induced by the V-shaped ribs. Figure 7b employs a visualization method combining the Q-criterion isosurface (Q = 1.0 × 104) with the superimposed temperature gradient magnitude (∣∇T∣). This approach clearly delineates the three-dimensional vortex structure: the core region of the secondary flow vortex (the region of high Q-criterion value) spatially corresponds with the region of peak temperature gradient. Conversely, the temperature gradient is significantly lower at the periphery of the vortex structure. This spatial correspondence directly reveals the heat transfer enhancement mechanism of the vortices: the rotational motion of the vortex pumps fluid from the mainstream toward the wall, while simultaneously transporting fluid away from the near-wall region. This process facilitates efficient mixing between the hot and cold fluids.

Figure 7.

Vorticity magnitude and Q-criterion isosurface with Reynolds number 11,766: (a) Vorticity: Magnitude; (b) Q-criterion isosurface.

Figure 8 presents the velocity magnitude contours on axial cross-sections at dimensionless positions (y/y0 = 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7, 0.9) along the heat exchange tube. As shown in Figure 8a,b, only localized, discrete velocity peaks (approximately 0.6 m/s) are observed in the near-wall region, with a discontinuous circumferential distribution. The velocity in the mainstream region remains uniform (approximately 0.4 m/s), indicating that the disturbance induced by the V-shaped micro-ribs is in its initial stage, and the flow is in a “triggering phase.” In Figure 8c,d, the local peaks merge to form a circumferentially continuous high-velocity band, with the magnitude increasing to 0.8 m/s—a 33% increase compared to the inlet section. The mainstream region begins to exhibit slight fluctuations due to the disturbance from the secondary flow, marking a transition toward “global enhancement”. As shown in Figure 8e, the velocity magnitude distribution becomes fully consistent with that in the development region: the magnitude of the near-wall high-velocity band (0.8 m/s), the fluctuation amplitude in the mainstream region (0.05 m/s), and the velocity gradients in the radial profiles all stabilize. This indicates that the flow has entered a fully developed turbulent state.

Figure 8.

Velocity magnitude distribution schematic diagram with Reynolds number of 11,766.

The shark-skin bionic structure induces periodic secondary flow disturbances through its specific geometric features, evolving from localized, isolated vortices to a globally continuous annular vortex structure and ultimately forming a fully developed turbulent flow field. Driven by the pressure gradient, reverse flow forms near the base of the micro-ribs, significantly disturbing the near-wall thermal boundary layer and enhancing wall shear stress and momentum exchange. The core region of the secondary vortex structure spatially coincides with the peak temperature gradient. Its rotational motion efficiently transports near-wall fluid into the mainstream, promoting fluid mixing. Through the synergistic mechanisms of geometry-induced flow, flow field evolution, and heat transfer enhancement, simultaneous augmentation of momentum transfer and heat transfer is achieved.

3.2. Temperature Field

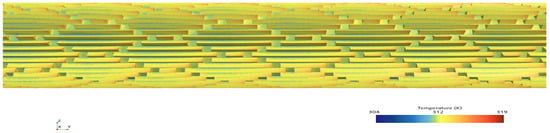

As shown in Figure 9, once the flow and heat transfer processes reach a stable state, the wall temperature distribution of the heat exchange tube shows significant unevenness. On the wind-facing side of the shark-skin microstructure, relatively high wall temperatures, along with local peaks, are observed. This can be ascribed to the effects of fluid impingement and local flow stagnation. The design of the microstructure induces helical flow patterns with significant tangential velocity components. These patterns effectively impede the development of the thermal boundary layer and improve the mixing of the near-wall fluid, thus achieving local heat transfer enhancement. However, in the root areas of the intermediate flow channels between adjacent diamond-shaped units of the shark-skin microstructure, flow separation occurs as the structural surfaces lift the flowing fluid. These areas are characterized by lower flow velocities and slower rates of fluid renewal. Coupled with thicker thermal boundary layers, this results in wall temperatures that are notably lower than those in the surrounding areas. These zones correspond to lower local Nusselt numbers and relatively weaker heat transfer performance.

Figure 9.

Wall temperature distribution schematic diagram with Reynolds number 11,766 and inlet temperature 297.15 K.

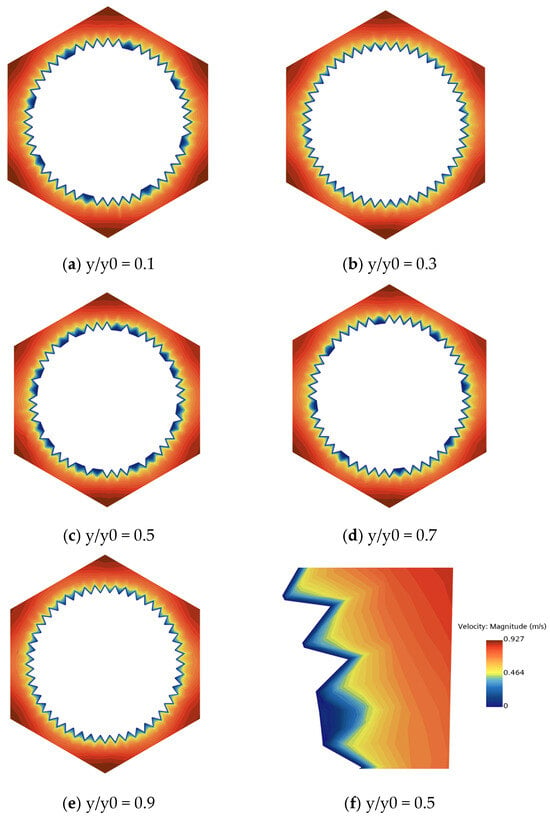

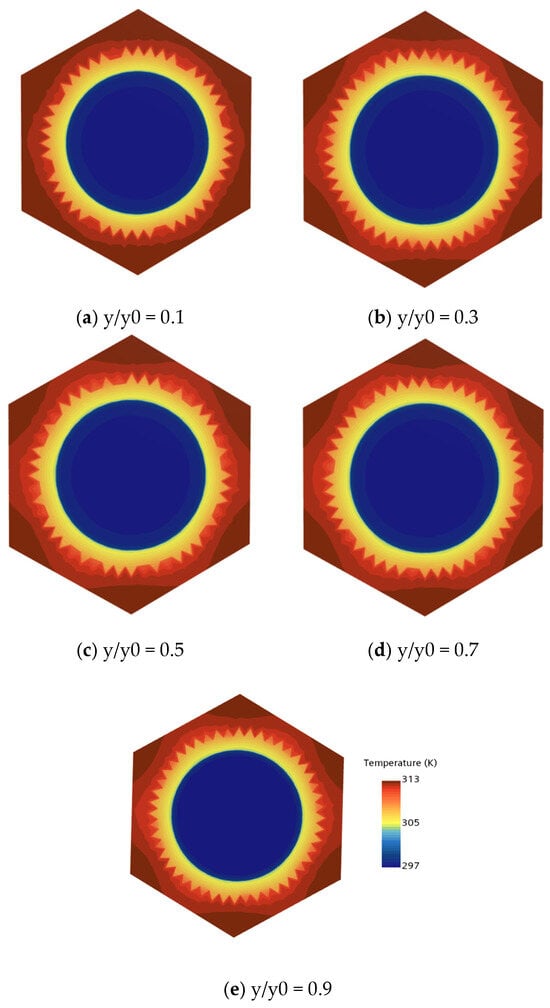

Figure 10 presents the temperature contours at different dimensionless axial positions along the heat exchange tube. In the inlet section, the temperature distribution exhibits a stratified structure characterized by a lower temperature at the center and a higher temperature near the wall, accompanied by a small temperature gradient. The flow is predominantly unidirectional along the axial direction, and heat transfer relies mainly on molecular diffusion. As the flow progresses downstream, the gradual development of secondary flow enhances flow disturbance. The swirling motion of vortices transports fluid away from the near-wall region toward the core, while simultaneously pumping core fluid toward the wall. This process periodically thins the thermal boundary layer, thereby enhancing heat transfer efficiency. The high-temperature region near the wall gradually expands toward the center, whereas the central low-temperature zone diminishes. The isotherms become uniformly distributed, and the temperature field reaches a stable state.

Figure 10.

Temperature field distribution schematic diagram with Reynolds number 11,766 and inlet temperature 297.15 K.

3.3. Heat Transfer Coefficient and Pressure Drop

As shown in Figure 11a, as the inlet temperature rises, the average temperature difference between the shell-side and tube-side fluids diminishes, leading to a decrease in the average heat transfer coefficients of both the shark-skin microstructure tube and the smooth tube. Nevertheless, under the same inlet temperature and Reynolds number conditions, the shark-skin microstructure tube shows remarkable heat transfer improvement. At inlet temperatures of 277.15 K, 287.15 K, 297.15 K, and 307.15 K, its heat transfer coefficient is enhanced by 56.7%, 46.1%, 43.2%, and 45.8%, respectively, when compared to the smooth tube. Figure 11b shows the variation in normalized temperature with normalized radial position, comparing the radial temperature distribution characteristics between the smooth tube and the shark-skin bionic tube. The difference in the radial distribution of the dimensionless temperature gradient essentially results from the regulation of the near-wall thermal boundary layer by the shark-skin microstructure. According to Fourier’s law, the wall heat flux is directly determined by the near-wall temperature gradient. Meanwhile, the heat transfer coefficient increases with the rise in heat flux. Therefore, the increase in the near-wall temperature gradient is the core mechanism for the enhancement of the heat transfer coefficient in the bionic tube.

Figure 11.

Comparison analysis: (a) Heat transfer coefficient; (b) Nomalized temperature; (c) Pressure drop; (d) PEC.

Figure 11c,d demonstrate that as the inlet velocity increases, along with a corresponding increase in the Reynolds number, the shell-side pressure drop rises significantly for both the microstructure-enhanced tube and the smooth tube. Due to the additional flow resistance introduced by the microstructures, the pressure drop of the bionic tube is consistently higher than that of the smooth tube at different flow velocities. Despite this, the performance evaluation criterion (PEC) of the shark-skin-inspired tube remains stable within the range of 1.25–1.30. This indicates that while achieving substantial heat transfer augmentation, the microstructural design effectively alleviates the negative impacts of increased frictional resistance, thus showing favorable comprehensive performance. Further optimization of geometric parameters, such as rib height, spacing, and attack angle, is anticipated to yield higher PEC values, suggesting great potential for engineering applications.

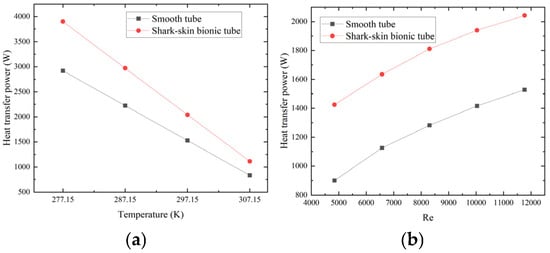

3.4. Heat Transfer Power

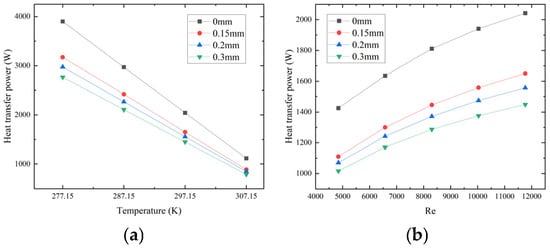

From the perspective of practical engineering application, the macroscopic performance of a heat exchanger primarily focuses on the variation in heat transfer power. To achieve the miniaturization design of heat exchangers, a comparative analysis of the heat transfer power between the bionic tube and the smooth tube is conducted. Figure 12a reveals that, in stark contrast to the smooth tube, the shark-skin microstructure heat exchange tube demonstrates remarkably higher heat transfer rates. When the Reynolds number is held constant at Re = 11,766, and the inlet temperatures are set at 277.15 K, 287.15 K, 297.15 K, and 307.15 K, respectively, the heat transfer rate of the shark-skin tube is augmented by 34.0%, 33.6%, 33.7%, and 33.1% compared to the smooth tube. Throughout diverse operating conditions, the heat transfer capacity of the shark-skin tube persistently outshines that of the smooth tube.

Figure 12.

Heat transfer power variation with inlet temperature and velocity: (a) Temperature; (b) Velocity.

Figure 12b reveals that, with a fixed inlet temperature of 297.15 K, as the inlet velocity escalates, the percentage increments in the heat transfer rate of the shark-skin microstructure tube relative to the smooth tube are 58.3%, 45.2%, 37.0%, and 33.6%, respectively. These findings suggest that under constant temperature circumstances, an increase in the inlet velocity has a more substantial impact on the extent of heat transfer enhancement offered by the microstructure.

4. Analysis of Fouling Deposition Characteristics

To evaluate the long-term performance influence of fouling deposition on the heat transfer tube with enhanced microstructure, the fouling deposition process is simplified in this section, and the influence mechanism of a uniform fouling layer thickness is simulated and analyzed. The primary objective of this study is to systematically evaluate the overall impact of “fouling thermal resistance accumulation” on heat transfer performance under steady-state conditions. For this purpose, a parametric uniform fouling layer model was developed, and the findings presented herein should be regarded as a “preliminary analysis.”

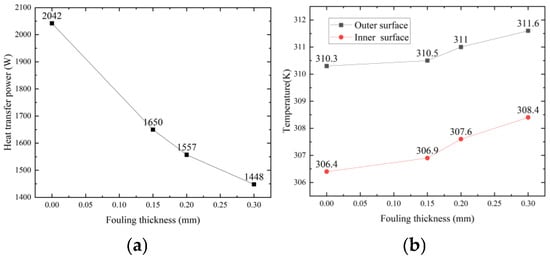

4.1. Deposition Layer Thickness

As depicted in Figure 13, the gradual thickening of the fouling layer brings about a notable decline in thermal performance. When the fouling layer thickness (δ) is 0.15 mm, 0.20 mm, and 0.30 mm, respectively, the heat transfer rates experience reductions of 19.2%, 23.8%, and 29.1% in comparison to the clean state (δ = 0). Significantly, when δ reaches 0.20 mm, the heat transfer capacity of the microstructured tube approaches that of the smooth tube, indicating that the heat transfer enhancement effect originally provided by the bio-inspired structure has been largely diminished.

Figure 13.

Analysis of heat transfer under different scale deposition thicknesses: (a) Heat transfer power; (b) Surface Temperature.

Concurrently, the augmented thermal resistance due to the fouling layer causes a substantial increase in wall temperatures. At δ = 0.30 mm, the maximum temperature rise for both the inner and outer walls hits 2.0 K, which directly confirms the inhibitory impact of fouling on the heat transfer process. This quantitative analysis lays vital groundwork for the design of anti-fouling-enhanced heat transfer components.

4.2. Inlet Temperature

As shown in Figure 14a, under a constant Reynolds number (Re = 11,766), the average temperature difference between the shell-side and tube-side fluids shows a downward trend as the inlet temperature rises, leading to a marked reduction in heat transfer. Taking the case at T = 277.15 K as a reference, the heat transfer rates under clean conditions decrease by 23.8%, 47.6%, and 71.4% when the inlet temperatures are 287.15 K, 297.15 K, and 307.15 K, respectively. Moreover, fouling deposition further intensifies the performance decline. For fouling thicknesses of δ = 0.15 mm, 0.20 mm, and 0.30 mm, the maximum decreases in heat transfer rate within the studied temperature range reach 72.0%, 71.4%, and 71.8%, respectively.

Figure 14.

Heat transfer power comparison analysis under different inlet temperatures and Reynolds numbers: (a) Temperature; (b) Reynolds numbers.

4.3. Inlet Flow Rate

As illustrated in Figure 14b, under a constant inlet temperature (297.15 K), an increase in the inlet velocity, accompanied by a corresponding rise in the Reynolds number (Re), substantially enhances the heat transfer capacity. Using Re = 4800 as a benchmark, the heat transfer rates under clean conditions increase by 14.7%, 27.1%, 36.1%, and 43.3%, respectively, as Re increases. Similar trends are observed for different fouling thicknesses. At δ = 0.15 mm, 0.20 mm, and 0.30 mm, the maximum increments in heat transfer within the tested velocity range are 48.6%, 31.2%, and 29.8%, respectively.

In conclusion, fouling deposition has a threefold weakening effect on the heat transfer enhancement of shark-skin bionic microstructure tubes. Firstly, the attenuation induced by thermal resistance is the primary factor contributing to performance degradation. When δ ≥ 0.20 mm (Tin = 297.15 K), the heat transfer power drops by more than 23.8% compared to the clean state, and the thermal benefit derived from the bio-inspired configuration is entirely negated by the fouling-induced degradation. Secondly, the synergistic coupling of temperature exacerbates the performance deterioration. Under high-temperature operation (307.15 K), the reduction in heat transfer caused by fouling reaches 71.8%. This results from the two-way reinforcement between the decreased average temperature difference and the accelerated fouling rate. Thirdly, the compensation provided by velocity is limited. Although high-speed flow improves heat transfer (with a maximum enhancement of 48.6% at δ = 0.15 mm), it cannot fundamentally eliminate the inherent thermal resistance caused by fouling deposits, which poses a fundamental limitation for the engineering implementation of long-lasting enhanced heat exchangers.

5. Conclusions

This research delves into the flow and heat transfer traits of shark-skin bionic microstructure heat exchange tubes within shell-and-tube heat exchangers via numerical simulation, while also examining the influence of fouling deposition. The key findings are presented as follows:

- (1)

- The shark-skin microstructure substantially disrupts the thermal boundary layer by generating secondary vortices and helical flows, which in turn heighten near-wall disturbances. This leads to a maximum improvement of 56.7% in the heat transfer coefficient. Meanwhile, the enlarged effective heat transfer area contributes to an increase in the heat transfer rate, varying from 33.1% to 58.3%. Within the investigated parameter scope, the tube showcases favorable overall thermohydraulic performance (PEC = 1.25–1.30), which validates the engineering viability of the bionic structure for large-scale heat exchange apparatuses.

- (2)

- Fouling deposition weakens the heat transfer enhancement capacity of the bionic structure through a triple-effect mechanism. Thermal resistance plays a dominant role, temperature coupling exacerbates the situation, and the compensatory effect from the increased flow velocity is limited. Under-rated operating conditions, when the fouling layer thickness reaches 0.20 mm, the heat transfer capacity of the shark-skin-inspired heat exchange tube becomes essentially equivalent to that of the smooth tube, and its heat transfer enhancement effect is largely negated.

- (3)

- By quantifying the coupled interaction mechanism between heat transfer enhancement and fouling deposition, the shark-skin-inspired bionic structure provides substantial support for the macro-scale application of shell-and-tube heat exchangers, and the fabrication of the prototype has been preliminarily completed (as shown in Figure 15), establishing both a theoretical and a design foundation for the development of next-generation marine heat exchange equipment with high-efficiency anti-fouling performance.

Figure 15. Schematic diagram of the shark-skin-inspired bionic heat exchange tube prototype.

Figure 15. Schematic diagram of the shark-skin-inspired bionic heat exchange tube prototype.

5.1. Limitations

In alignment with practical engineering applications and the design objective of heat exchanger miniaturization, this study primarily focuses on the overall variation in the heat transfer capacity of the tubes. The fouling model adopted a simplified uniform layer assumption, which does not account for complex mechanisms such as marine chemical interactions. Furthermore, specific validation for dynamic fouling deposition processes is currently lacking—both represent important directions for our future work.

5.2. Future Work

A comprehensive performance evaluation and experimental testing of the shark-skin-inspired structure will be conducted, aiming to develop a novel type of heat exchange tube that exhibits both excellent performance and long-term stability, with the goal of achieving practical engineering application.

Author Contributions

M.L. proposed the research point and performed numerical simulation and manuscript writing. J.S. and S.Y. participated in data analysis process. H.X. and X.Z. provided critical feedback and revised the manuscript. X.L. participated in the drawing of the picture. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Key Basic Research Projects of the Foundation Strengthening Plan, grant number 2023-JCJQ-ZD-131-00.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Nomenclature

| Cp | specific heat capacity, kJ/(kg·K) |

| D | diameter of the tube, mm |

| f | friction factor |

| h | convective heat transfer coefficient, W/(m2·K) |

| L | test section length, m |

| Nu | Nusselt number |

| ΔP | pressure drop, Pa |

| PEC | performance evaluation criterion |

| Re | Reynolds number |

| T | temperature, K |

| u | velocity, m/s |

| δ | fouling thickness, mm |

| Λ | heat conductivity, W/(m·K) |

| υ | kinetic viscosity, Pa·s |

| μ | dynamic viscosity, m2/s |

| ρ | density, kg/m3 |

| Subscripts | |

| c | for the average |

| f | for the fluid |

| s | for the solid |

| in | for the inlet |

| x, y, z | coordinates |

| w | for the wall |

| 0 | for the smooth tube |

References

- Yang, W.; Zhou, F.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y. Performance analysis of axial air cooling system with shark-skin bionic structure containing phase change material. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 250, 114921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Lu, M.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Chen, X. A high-fidelity sharkskin inspired placoid-scales structured microchannel (SPMC) for advancement of heat transfer performance. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 224, 125301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Guo, D.; Huang, X. Heat transfer enhancement, entropy generation and temperature uniformity analyses of shark-skin bionic modified microchannel heat sink. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 146, 118846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Shi, Y.; Chen, J.; Dai, Y. A Biomimetic Microchannel Heat Sink for Enhanced Thermal Performance in Chip Cooling. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awais, M.; Bhuiyan, A.A. Recent advancements in impedance of fouling resistance and particulate depositions in heat exchangers. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 141, 580–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Quan, Y. A CFD study of particle deposition in three-dimensional heat exchange channel based on an improved deposition model. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2021, 178, 121633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Han, Z.; Liu, W.; Xu, Z. The local particulate fouling characteristics of curved rectangular vortex generators in a pulsating flow channel. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 158, 107860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Han, Z.; Liu, W.; Wang, T.; Chang, H. Study on the effect of the porous media equivalent particulate fouling model on heat transfer performance in heat exchanger channels. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 266, 125709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Wei, X.; Yang, Q.; Li, N.; Yao, E. Numerical simulation and experimental study of the growth characteristics of particulate fouling on pipe heat transfer surface. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 55, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darand, J.; Jafarian, A. Long-term simulation of crystallization fouling in a forced circulation crystallizer. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 231, 125845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oon, C.S.; Kazi, S.N.; Hakimin, M.A.; Abdelrazek, A.H.; Mallah, A.R.; Low, F.W.; Tiong, S.K.; Badruddin, I.A.; Kamanger, S. Heat transfer and fouling deposition investigation on the titanium coated heat exchanger surface. Powder Technol. 2020, 373, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Xu, Z.; Yu, X. CFD modeling for prediction of particulate fouling of heat transfer surface in turbulent flow. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 144, 118428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Xu, Z. Experimental and numerical investigation on particulate fouling characteristics of vortex generators with a hole. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 148, 119130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Fan, H.; Han, Z. The comparison between integral and local calculation methods on the simulation of crystallization fouling. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2022, 171, 107252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, C.; Zhou, X. Local deposition characteristics of calcium carbonate fouling in different enhanced tubes. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 54, 104048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Li, J.; Chen, Z.; Liu, W. An improved CFD particulate fouling simulation method: The local fouling method. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 154, 107439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Z. Characteristics of local deposition of CaCO3 fouling on rough wall surfaces of heat exchanger channels. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2025, 163, 108718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menter, F. Zonal Two Equation Kw Turbulence Models for Aerodynamic Flows; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VI, USA, 1993; p. 2906. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Kumar, A.; Chamoli, S.; Kumar, M. Experimental investigation of heat transfer enhancement and fluid flow characteristics in a protruded surface heat exchanger tube. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2016, 71, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, X.; Ran, L.; Xiao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, N.; Ding, M. Analysis of enhanced heat transfer characteristics in a bionic fish scale tube for turbulent flow. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2025, 57, 103715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, A.L.; Ooi, K.T. Scale-inspired enhanced microscale heat transfer in macro geometry. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2017, 113, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gao, J.; Gao, T. Forced convection heat transfer of steam in a square ribbed channel. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2012, 26, 1291–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.