Abstract

During the drilling operations of a shale gas well in Central China, a severe failure occurred in the pressure-resistant cylinder of the measurement while drilling (MWD) tool, with numerous microcracks observed on the outer surface of the cylinder. This significantly compromised the safety of the MWD tool and the reliability of the logging data. To determine the cause of the failure, macroscopic morphology analysis and physicochemical performance tests were conducted on the failed pressure-resistant cylinder, which is made of Cr20Ni11 (UNS 308) austenitic stainless steel. Additionally, scanning electron microscopy, X-ray energy dispersive spectroscopy, white light interferometry, and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy were employed to analyze the morphology and chemical composition of the corrosion products and cracks, thereby identifying the cause of the corrosion failure. It is demonstrated that the physicochemical properties of the pressure-resistant cylinder comply with the specifications of relevant standards. Nevertheless, the size of non-metallic inclusions in the material reaches 100 μm, which significantly enhances the material’s susceptibility to stress corrosion cracking (SCC). Meanwhile, solid particles and high-concentration Cl− present in the drilling fluid deteriorate the passive film formed on the substrate surface. EDS analysis reveals that the Cl− content is measured to be 4.09 wt%, which induces pitting on the substrate with a maximum pitting depth of 13.5556 μm. Under the synergistic effect of stress and corrosion, the pressure-resistant cylinder experiences SCC failure initiated by Cl−; specifically, cracks nucleate at the bottom of the pitting pits and propagate along the radial direction.

1. Introduction

Against the backdrop of the global energy transition and the increasingly prominent strategic role of unconventional oil and gas resources, shale gas, as an important component of clean energy, has become a hotspot for exploration and development worldwide [1,2]. China is rich in shale gas resources, with geological resources exceeding 100 trillion cubic meters and technically recoverable resources ranging from 10 × 1012 m3 to 32 × 1012 m3. These resources are primarily distributed in the Sichuan Basin and its surrounding areas. The large-scale commercial development of shale gas holds profound significance for ensuring national energy security and optimizing the energy consumption structure [3]. However, shale gas reservoirs in China are generally characterized by deep burial, complex formation pressure systems and poor rock drillability, posing unprecedented challenges to cost-effective development [4,5]. In this context, horizontal drilling and extended-reach directional drilling technologies, as key engineering methods to unlock the commercial potential of shale gas, have been extensively applied [6,7]. These technologies enable well trajectories to precisely navigate through thin, high-quality reservoirs thousands of meters underground, maximizing the contact area between the wellbore and the reservoir, thereby significantly enhancing single-well production and ultimate recovery rates [8,9].

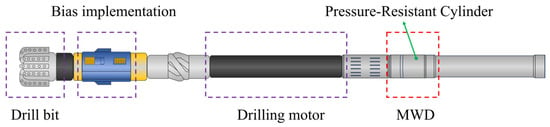

The successful implementation of directional drilling technology highly depends on the Rotary Steerable System (RSS). As shown in Figure 1, the RSS includes components such as the drill bit, bias implementation, drilling motor, and MWD tools [8]. The MWD tool is composed of multiple subs, with the pressure-resistant cylinder serving as the protective and pressure-bearing housing for each measurement sub. It contains internal sensors and signal processing circuits. The front end of the pressure-resistant cylinder is connected to power components such as the drill bit and the positive displacement motor, while the rear end is connected to the drill string. Consequently, during drilling operations, the tools are subjected to prolonged exposure to high-temperature and high-pressure environments, severe vibration and shock, as well as electrochemical corrosion caused by complex drilling fluids and acidic gases. The coupling of these multiple factors exposes drilling tools to significant failure risks, and numerous related incidents have been widely reported. Nabifo et al. [10] investigated the failure modes and causes of a drill bit during penetration into hard rock formations using methods such as macroscopic observation, microscopic analysis, and chemical analysis. They concluded that the failure originated from inherent manufacturing defects in the material, combined with the effects of direct impact, repetitive loading, and friction during drilling. Shen et al. [11] studied the fracture failure of an S135 drill pipe by integrating physicochemical performance tests, elemental analysis, fracture analysis, heat treatment simulation, and finite element analysis. They found that non-uniform heat treatment resulted in abnormal microstructures, including coarse bainite and ferrite in local sections of the drill pipe, leading to reduced material strength and eventual overload fracture in these abnormal zones. Yu et al. [12] analyzed a failure case of an S135 drill pipe through experimental testing and mechanical simulation. The results indicated that, although the physicochemical properties of the drill pipe met standard requirements, damage to the nickel plating exposed the base material to corrosion and erosion. This ultimately led to crack initiation at internal corrosion pits, with subsequent multiple circumferential extensions under stress concentration, resulting in fracture. Although failure of drilling tools has been extensively studied, current research remains predominantly focused on drill bits and drill pipes, while studies on the failure behavior of RSS are still relatively limited. Only a limited number of studies have focused on the failure cases of chromium-plated coatings on rotors in RSS. Cobo et al. [13] found that salt solutions penetrate into the substrate through macroscopic cracks. As the steel substrate corrodes, the chromium coating loses adhesion and spalls under the action of friction, resulting in the loss of protective effect and subsequent failure of the rotor. Ranjbar et al. [14] noted that the service environment of the rotor contains a high solid content and salts. The detachment and dissolution of the chromium-plated coating on the rotor surface are attributed to two main factors: on the one hand, the solid particles embedded in the stator cause cutting and spalling of the chromium coating; on the other hand, the high-speed solids induce erosion of the chromium coating.

Figure 1.

Structural components of the RSS.

In the RSS, MWD enables the real-time transmission of critical downhole engineering parameters (such as inclination, azimuth, and tool face angle) and geological parameters (such as natural gamma ray and resistivity) to the surface [15]. Engineers use this data to make precise decisions and dynamically adjust the drilling trajectory. Therefore, the operational stability of the MWD system directly determines drilling safety, the accuracy of wellbore trajectory control, and the efficiency of reservoir development. Among the various components of the MWD system, the pressure-resistant cylinder serves as the core pressure-bearing and protective component. It is typically manufactured from high-strength stainless steel or nickel-based alloys to shield internal electronic components from downhole high temperatures, high pressures, and corrosive substances.

In the oil and gas industry, the failure of oil country tubular goods typically involves multiple factors. Beyond the aforementioned abnormal microstructures and coating damage, stress corrosion cracking (SCC) represents a critical but insidious failure mode for high-strength steel. SCC is a sudden and severe failure mechanism in materials exposed to corrosive environments, particularly in chloride-rich and high-temperature conditions [16]. Chloride ions can damage the protective oxide layer and induce pitting corrosion, which in turn serves as the initiation site for SCC. High chloride concentrations typically accelerate crack propagation [17]. In synergy with temperature, the crack propagation rate can reach as high as 0.1 mm/day. Fu et al. [18] investigated the SCC case of 13Cr tubing in phosphate packer fluid and concluded that the primary cause of failure was the synergistic effect of KH2PO4 phosphate packer fluid and CO2 under tensile stress, which resulted in brittle transgranular fracture of the tubing. Similarly, Zhang et al. [19] also investigated the SCC case of 13Cr tubing in high-temperature and high-pressure gas wells and found that the mechanism of SCC is corrosion product film breaking. However, despite the wealth of discussion on SCC in tubing, there is a paucity of focused research on the SCC susceptibility of critical precision components within RSS/MWD.

Despite the acknowledged severity of downhole environments and the critical role of MWD tools in directional drilling, there remains a significant knowledge gap. Specifically, systematic research on the failure mechanisms of MWD pressure-resistant cylinders in the context of deep shale gas wells is notably limited.

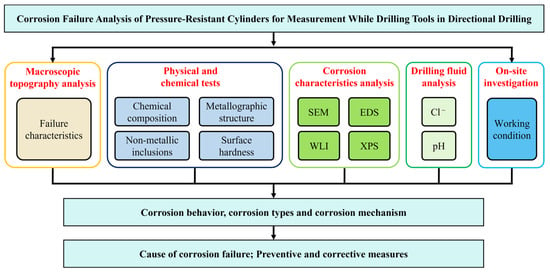

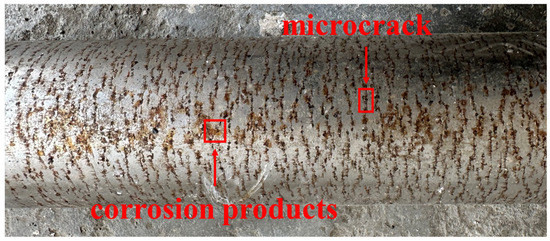

To bridge this gap, the study systematically analyzes the causes of corrosion cracking in the external pressure-resistant cylinder of a directional drilling MWD tool used in a shale gas drilling operation in Central China. The cylinder is made of Cr20Ni11 austenitic stainless steel in a quenched and tempered condition. When the drilling depth exceeded 3800 m, the bottomhole temperature reached 135 °C. Upon pulling out of the hole, annular dense corrosion streaks were observed on the surface of the external pressure-resistant cylinder (Figure 2). Samples were taken for analysis, and the physicochemical properties of the pressure cylinder were tested. Furthermore, Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) were used to examine the corrosion morphology on the surface and cross-sections. White Light Interferometry (WLI) was employed for quantitative analysis of the corrosion morphology, and X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) was used for qualitative analysis of the corrosion products. These methods were applied to clarify the cause of the corrosion failure of the pressure-resistant cylinder, and corresponding protection strategies are proposed to enhance its service life. The analysis method and flow chart are shown in Figure 3. This study aims to: (1) definitively identify the root cause of failure; (2) elucidate the detailed mechanism of Cl−-induced crack initiation and growth; and (3) provide actionable insights for material selection, manufacturing quality control, and operational protection to enhance the reliability of MWD tools in aggressive drilling environments.

Figure 2.

Morphology of the failure pressure-resistant cylinder.

Figure 3.

Analysis method and flow chart.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Physical and Chemical Performance Test

The chemical composition was determined to verify whether the material of the pressure-resistant cylinder meets standard requirements. The chemical composition of the pressure-resistant cylinder was analyzed using a SPECTRO MAXx07-F optical emission spectrometer (SPECTRO, Kleve, Germany) according to ASTM A751-20. Microstructural examination was conducted to identify key features that influence SCC susceptibility, including the matrix phase, grain boundaries, and most critically, the size, distribution, and type of non-metallic inclusions, which can act as initiation sites for pitting and cracking. A specimen measuring 10 mm × 15 mm × wall thickness was sectioned from the substrate of the failed pressure cylinder. After sequential grinding with 360, 600, 800, 1000, and 1200 grit sandpaper, followed by polishing with a diamond polishing compound, the specimen was etched using a 4% nital solution. Subsequently, it was rinsed with tap water, dehydrated with alcohol, and dried with cool air. The microstructure of the metal was then observed using an SOPTOP RX50M (Sunny Instruments, Singapore) metallurgical microscope. The microstructure of the pressure cylinder cross-section was analyzed, and non-metallic inclusions in the steel were examined and rated, along with grain size rating, with reference to standards GB/T 13298-2015 [20], GB/T 10561-2023 [21], and GB/T 6394-2017 [22]. Since SCC is affected by the tensile strength and yield strength of materials, tensile tests were conducted using a microcomputer-controlled electro-hydraulic servo universal testing machine (MTS SHT4106-G, MTS, Eden Prairie, MN, USA) in accordance with the ISO 6892-1:2019 standard [23]. Verify whether the hardness of the pressure-resistant cylinder material meets the requirements of the API standard, as excessively low hardness may make it difficult to withstand friction during drilling operations. In addition, studies have shown that the greater the hardness of steel, the greater the susceptibility to SCC [24]. The Vickers hardness of the pressure cylinder was tested using a Huayin Digital Microhardness Tester (HVS-1000, Huayin, Yantai, China) in accordance with GB/T 4340.1-2024 [25], with a test load of 10 g.

2.2. Microscopic Corrosion Morphology and Composition Test

The surface and cross-section of the pressure-resistant cylinder were examined using a SEM (JSM-7500F, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with EDS (INCA X-max50, Oxford Instruments, Oxford, UK) to observe the microscopic morphology of the corrosion products and analyze their elemental composition. After removing the corrosion products from the surface of the pressure-resistant cylinder with a cleaning solution, the corrosion morphology and depth were observed using a WLI (Bruker Contour GT-In Motion GTK-16, Billerica, MA, USA). The composition of the corrosion products on the pressure-resistant cylinder was analyzed by XPS (Thermo Scientific K-Alpha, Waltham, MA, USA), with calibration performed using the C1s peak binding energy (284.6 eV). All peaks were fitted using the XPS Peak 4.1 software [26].

3. Results

3.1. Macroscopic Observation

The macroscopic morphology of the failed surface of the pressure-resistant cylinder is shown in Figure 4. No significant corrosion traces were observed near the pin end of the failed pressure-resistant cylinder, and its external surface exhibited a metallic luster. Irregular pitting corrosion spots, appearing black in color, were found in the transition area between the pin and the tube body. The corroded area on the tube body of the pressure-resistant cylinder displayed parallel brown microcracks. Closer observation revealed that these cracks either penetrated or connected elliptical black corrosion pits.

Figure 4.

Macro corrosion morphology of pressure-resistant cylinder surface.

3.2. Physical and Chemical Tests

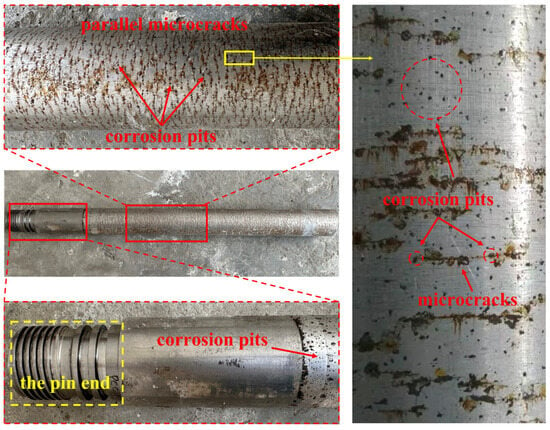

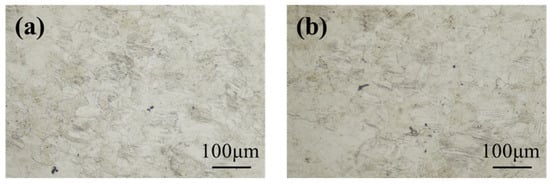

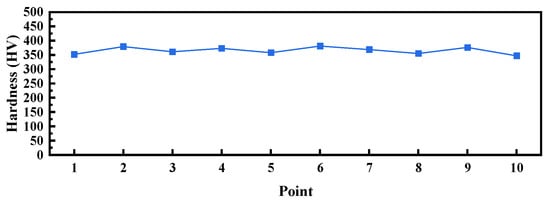

Table 1 presents the chemical composition test results of the pressure-resistant cylinder. Compared with the API standard [27], the contents of P and S in the corroded cylinder are significantly lower than the limits specified by the API standard. In general, low levels of P and S in austenitic stainless steel substantially improve its resistance to SCC [24,28]. However, the occurrence of SCC in this case demonstrates that the beneficial effect of low P and S was insufficient to prevent failure. This can be attributed to the overriding influence of other critical factors. Table 2 shows the ratings for non-metallic inclusions, microstructure, and grain size of the pressure-resistant cylinder, while Figure 5 and Figure 6 display the non-metallic inclusions and microstructure, respectively. Analysis of Table 2 and Figure 5 indicates that the non-metallic inclusions in the pressure-resistant cylinder are rated as C1.0, D1.0, and DS2.0–DS4.0. From Table 2 and Figure 6, the microstructure is identified as austenite, with pitting pits and accumulated corrosion products present in some areas, and slight damage or spalling of the structure observed in individual locations. The grain size rating is 6.0. Large-sized non-metallic inclusions not only destroy the continuity of the matrix and reduce the material strength but also easily become stress concentration sources [29,30]. During the operation of the rotary steerable system, the rotation and vibration of the drill string subject the pressure-resistant cylinder to alternating cyclic stresses. Additionally, when drilling in high-dogleg sections, wellbore curvature imposes significant bending stress on the pressure-resistant cylinder. Under the coupling of multiple stresses and downhole corrosive media, cracks readily initiate and propagate rapidly at the interface between inclusions and the matrix, ultimately inducing stress corrosion cracking (SCC) and corrosion fatigue [31,32,33,34]. Tensile specimens were prepared from the pressure-resistant cylinder, and three independent replicate tests were conducted. The average ultimate tensile strength and yield strength of the pressure-resistant cylinder were determined to be 559 MPa and 266 MPa, respectively. Figure 7 shows the Vickers hardness test results. Each test specimen was measured 10 times, and the average value was taken as the Vickers hardness value. The results show that the average Vickers hardness of the pressure-resistant cylinder reaches 366 HV, which meets the requirements of the API standard.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of the failed pressure-resistant cylinder (wt%).

Table 2.

Analysis results of non-metallic inclusions, structure and grain size of the failed pressure-resistant cylinder.

Figure 5.

Non-metallic inclusions: (a) Horizontal; (b) Vertical.

Figure 6.

Microstructure: (a) Horizontal; (b) Vertical.

Figure 7.

Vickers hardness test result of the pressure-resistant cylinder.

3.3. Analysis of Corrosion Characteristics of Failure Locations

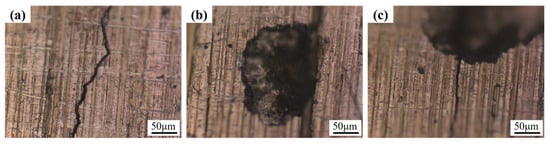

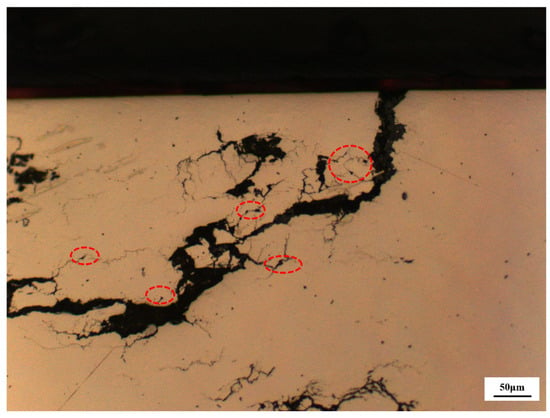

A sample was taken from the wall of the pressure-resistant cylinder and initially examined using an optical microscope, with the results shown in Figure 8. The wall surface of the pressure-resistant cylinder was covered with numerous fine cracks, while clearly extended cracks and approximately elliptical black corrosion pits were observed. By tracing the crack back to its origin, it was found that one end of the crack was connected to a corrosion pit, indicating that the crack initiated from this corrosion pit. This phenomenon closely resembles typical SCC. Generally, corrosion pits serve as stress concentration points for crack initiation, while sustained stress promotes crack propagation from these defects [35].

Figure 8.

Preliminary observations under the optical microscope: (a) cracks, (b) corrosion pit, (c) crack initiation at a corrosion pit.

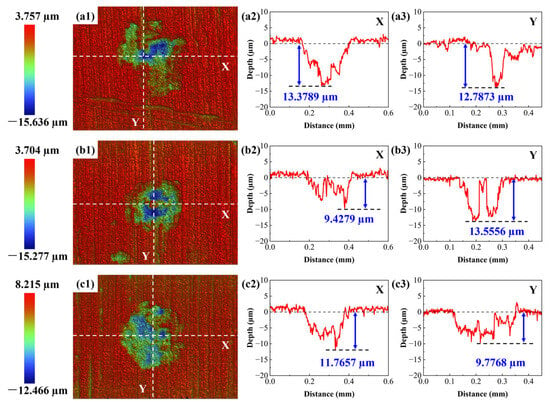

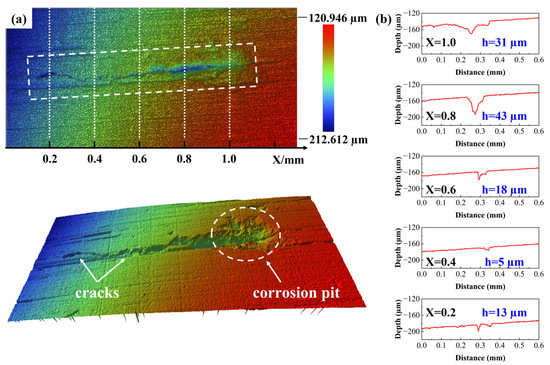

To quantitatively analyze the corrosion pits and cracks on the wall of the pressure-resistant cylinder, a sample was taken from the cylinder wall and examined using WLI. The corrosion products were removed from the sample surface via a chemical pickling procedure prior to WLI analysis. The sample was immersed in a freshly prepared pickling solution (500 mL HCl + 500 mL H2O + 3.5 g C6H12N4) at room temperature for 2–5 min. During immersion, the surface was very gently agitated with a soft-bristled nylon brush to assist in the removal of adherent deposits, with the process closely monitored to prevent over-etching of the base metal. Cleaning was considered complete when visible scale was removed and gas evolution ceased. Subsequently, the sample was thoroughly rinsed with flowing deionized water for at least 3 min, followed by ultrasonic cleaning in analytical-grade acetone for 5 min to displace residual water. Finally, the sample was dried using a gentle stream of warm nitrogen gas. Quantitative analysis of the corrosion morphology was performed on multiple representative fields of view. In a selected area of 1 mm2, a total of 9 corrosion pits were counted, yielding an average pit density of approximately 9 pits/mm2. The measurement results of the three selected corrosion pits are shown in Figure 9. The corrosion pits exhibited elliptical and irregular shapes, with depths ranging between 9.4279 μm and 13.5556 μm. At this stage, no cracks were observed around the corrosion pits. Furthermore, the average aspect ratio (depth/width) of three typical cracks emanating from pit bottoms was measured to be 76.97, indicating the formation of sharp, deep cracks conducive to high stress concentration and sustained propagation.

Figure 9.

Measurement results of corrosion pit depths. (a1–c1) 2D morphology images of corrosion pits; (a2–c2) X-direction contour curve of corrosion pits; (a3–c3) Y-direction contour curve of corrosion pits.

The area where a crack connects to a corrosion pit was selected for observation. The results, as shown in Figure 10, indicate that the crack originated from the corrosion pit and propagated along the negative X-axis direction. Measurements were taken at positions of 0.2 mm, 0.4 mm, 0.6 mm, 0.8 mm, and 1.0 mm along the crack and corrosion pit. The position at 1.0 mm corresponded to a large, irregular corrosion pit, while the other measurement points corresponded to narrow, elongated cracks. As the crack propagated, both the width and depth of the crack showed a continuous decreasing trend.

Figure 10.

Measurement results of the crack. (a) 2D and 3D morphology images of the crack; (b) contour plots of crack cross-sections measured at different positions.

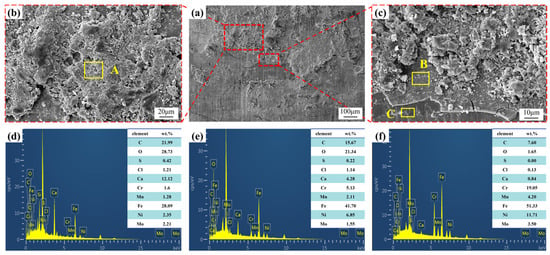

To clarify the failure cause of the pressure-resistant cylinder, further analysis was conducted on the corrosion pits and cracks on its wall. Two different corroded areas from Figure 11 were selected, and SEM combined with EDS was used to analyze the micromorphology and elemental composition of the corrosion products and microcracks on the failed surface. Figure 12 shows the SEM observations and EDS results of the corrosion products on the failed tube’s surface, with the EDS test area marked by the yellow box in Figure 12.

Figure 11.

Sampling locations for microscopic analysis of corrosion pits and cracks.

Figure 12.

SEM morphology photos of the corrosion pit and the energy spectrum analysis of marked points. (a) microscopic morphology under low-power microscope; (b,c) locally magnified images in figure (a); (d) elemental content of marked point A; (e) elemental content of marked point B; (f) elemental content of marked point C.

As shown in Figure 12, the corrosion products on the tube surface were unevenly distributed. Some areas, including location A, were composed of corrosion products. The accumulation of these corrosion products was loose with numerous pores. Studies indicate that due to the small atomic radius and strong penetration ability of chlorine, these pores provide channels for Cl− to enter the metal matrix [36,37]. Chemical composition analysis of location A showed that the corrosion products primarily consisted of C, O, Ca, and Fe, with contents of 21.99%, 28.73%, 12.12%, and 28.09%, respectively. It also contained smaller amounts of Cr, Mn, Ni, and Mo, which are the main alloying elements of the pressure-resistant cylinder. Additionally, 0.42% S and 1.21% Cl were detected.

The area indicated by location B showed a layer of corrosion product film, but it exhibited severe cracking and peeling, exposing the metal substrate, where it had spalled off. Under the combined action of chloride ions and stress, the adhesion at the interface between the corrosion products and the metal matrix is lost. Consequently, the corrosion product layer undergoes cracking and spalling. Chemical composition analysis of locations B and C revealed that the corrosion products at location B were mainly composed of C, O, and Fe, with contents of 15.67%, 21.34%, and 41.7%, respectively. Furthermore, the contents of Ca, S, and Cl were 4.28%, 0.22%, and 1.14%, respectively. At location C, the contents of elements such as C, O, Ca, and Cl decreased significantly to 7.60%, 1.65%, 0.84%, and 0.13%, respectively. No S element was detected. In contrast, the substrate elements of the pressure-resistant cylinder, such as Fe, Cr, Mn, Ni, and Mo, all increased, with the Fe content reaching as high as 51.33%. This indicates that location C is the metal substrate exposed by the spalling of corrosion products.

Compared to the substrate area, locations A and B showed significantly higher O content and markedly lower base metal element content, indicating severe oxygen-induced corrosion of the pressure-resistant cylinder. However, the corrosion products were loosely accumulated, and the corrosion product film exhibited extensive cracking, providing poor protection to the substrate. Simultaneously, Cl− can penetrate through the cracks into the inner layers of the corrosion product film, further promoting pitting corrosion of the metal [38].

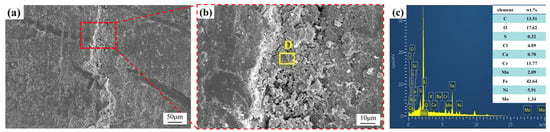

Figure 13 shows the SEM observation results and EDS analysis data of the microcracks on the surface of the failed cylinder, where the EDS test area corresponds to location D in Figure 13. As can be seen from Figure 13, the microcracks are filled with corrosion products, which are loose and contain numerous pores. The corrosion products at Location D are mainly composed of C, O, Fe and Cr, with contents of 13.51%, 17.62%, 42.64% and 11.77%, respectively. In addition, the contents of Ca, S and Cl elements are 0.70%, 0.32% and 4.09%, respectively. It is worth noting that the content of Cl− in the microcracks is relatively high, and austenitic stainless steel has high susceptibility to stress corrosion cracking in chloride-containing environments [39]. Therefore, it is inferred that the microcracks on the surface of the pressure-resistant cylinder are caused by Cl−-induced stress corrosion cracking.

Figure 13.

SEM morphology photos of the crack and the energy spectrum analysis of marked points. (a) microscopic morphology under low-power microscope; (b) locally magnified image in figure (a); (c) elemental content of marked point D.

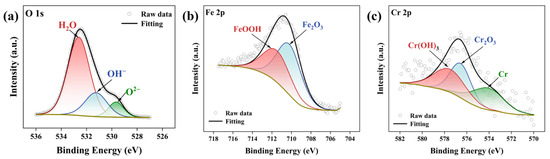

To analyze the corrosion products on the surface of the pressure-resistant cylinder, XPS analysis was performed on these products. Figure 14a–c presents the high-resolution scan spectra for O 1s, Fe 2p, and Cr 2p, respectively. In the Fe 2p spectrum, the peak observed around 711.8 eV corresponds to FeOOH, while the peak around 710.3 eV corresponds to Fe2O3 [40]. According to previous studies, FeOOH in the passive film exhibits an amorphous structure, which tends to generate more hydroxyl vacancies, thereby reducing the protective capability of the passive film [41,42]. In the Cr 2p spectrum, the peak around 574 eV corresponds to Cr atoms, whereas the peaks around 577.7 eV and 576.6 eV correspond to Cr(OH)3 and Cr2O3, respectively [43]. In the O 1s spectrum, the profile consists of three peaks located near 529.7 eV, 531.2 eV, and 532.5 eV, corresponding to O2−, OH−, and H2O, respectively. Research indicates that O2− and OH− correspond to metal oxides and hydroxides, while H2O represents bound water within the passive film [44]. In summary, it can be determined that the primary corrosion products are Fe2O3, FeOOH, Cr(OH)3, and Cr2O3.

Figure 14.

XPS high-resolution spectra results of O 1s, Fe 2p3/2, and Cr 2p3/2. (a) O 1s; (b) Fe 2p3/2; (c) Cr 2p3/2.

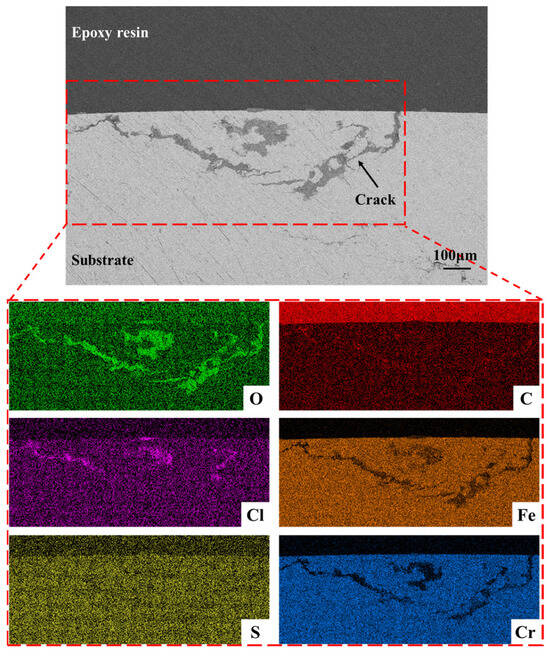

To further clarify the crack propagation characteristics, the cross-section of the micro-crack was characterized using SEM, EDS and a metallographic microscope. Figure 15 shows the cross-sectional morphology of the microcrack in the failed surface and the EDS elemental mapping results. Based on previous analysis and Figure 15, it can be observed that the crack originated at the bottom of a corrosion pit on the outer surface and propagated in the direction of the wall thickness. The crack exhibits dendritic branching, which differs from the morphology of cracks caused solely by mechanical stress. The crack is filled with a certain amount of corrosion products, indicating typical characteristics of SCC [45]. The relationship between cracks and inclusions was observed under a metallographic microscope. The results are presented in Figure 16, revealing the phenomenon that cracks connect or propagate through inclusions. This indicates that the presence of inclusions reduces the material strength and induces the direction of crack propagation. Similar phenomena have been reported in existing studies. Lou et al. [46] investigated the adverse effects of silicon oxide-rich inclusions on the SCC characteristics of 316L austenitic stainless steel and found that the silicon oxide-rich phases along grain boundaries preferentially dissolved, which appeared to accelerate oxidation and result in extensive crack branching. Zhong et al. [47] studied the SCC behavior of 310S austenitic stainless steel under different temperatures and pressures and observed that SCC cracks initiated from inclusions and small pits within the matrix, then gradually propagated through the cross-section into the matrix until final fracture occurred.

Figure 15.

The cross-sectional morphology of the micro-crack in the failed surface.

Figure 16.

Cracks connect or propagate through inclusions.

The EDS analysis results reveal a significant enrichment of O element along the crack path, suggesting the in-situ formation of iron oxides during crack propagation, which is consistent with observations reported by other researchers [48]. Simultaneously, a notable enrichment of Cl element is observed in the crack region, and the crack is filled with corrosion products. Furthermore, the high degree of overlap between the enriched areas of O and Cl elements demonstrates that the crack in the pressure-resistant cylinder was induced by Cl−-mediated SCC.

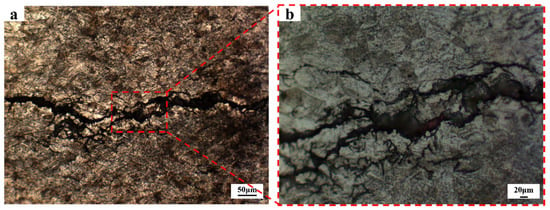

Then, the cross-section was etched with an etchant to observe the crack propagation mode. As illustrated in Figure 17, the cracks are relatively wide and propagate across the grains, corresponding to a transgranular cracking mode. Therefore, the cracking observed in this study originates from pitting corrosion pits formed by the breakdown of the passive film induced by high-concentration chloride ions, and it is identified as near-neutral pH SCC with a transgranular propagation characteristic.

Figure 17.

Crack propagation mode. (a) microscopic morphology under low-power microscope; (b) locally magnified image in figure (a).

4. Failure Mechanism Analysis

SCC is a common failure mode in the petroleum industry. Generally, the occurrence of SCC involves the synergistic effects of material properties, environmental factors, and applied stresses. Therefore, the SCC mechanism of the pressure-resistant cylinder is explained below mainly from these three aspects.

First, an analysis is conducted based on the service environment of the pressure-resistant cylinder. Field drilling fluid samples were collected and analyzed in this study. The test results showed that the chloride ion concentration in the drilling fluid was as high as 156,500 mg/L, with a pH value of 5.75 and a solid content of approximately 20%. Typically, SCC of metals can be classified into two categories according to the environmental pH value [49,50]: the first is anodic dissolution-type SCC, which occurs in high-pH solutions (pH range: 9–10) [51]; the second is SCC induced by the combined effects of anodic dissolution and hydrogen embrittlement, which takes place in near-neutral pH solutions (pH range: 6.5–7.5) [50,51]. Studies have confirmed that high chloride ion concentrations significantly increase the SCC susceptibility of materials in near-neutral environments [17]. Meanwhile, the higher the pH value (up to approximately 7), the more prone the electrolyte is to inducing near-neutral pH SCC [52]. Therefore, in this case, the extremely high chloride ion concentration and near-neutral pH value greatly increased the likelihood of near-neutral pH SCC occurring in the pressure-resistant cylinder. In addition, due to the strong permeability of chloride ions, they pose a severe threat of pitting corrosion to the passive film of the pressure-resistant cylinder. Notably, pitting corrosion pits are often the preferential sites for the initiation of Cl-SCC.

Second, the analysis focuses on the material characteristics of the pressure-resistant cylinder. Metallographic analysis and non-metallic inclusion testing of the failed pressure-resistant cylinder indicated that it had a grain size grade of 6, an austenitic matrix structure, and slight damage or spalling in localized areas. The non-metallic inclusions were rated as C1.0, D1.0, and DS2.0–DS4.0. Although relevant standards do not impose strict restrictions on the inclusion rating of pressure-resistant cylinders, extensive studies have shown that non-metallic inclusions may increase the SCC susceptibility of materials and even act as the root cause of failure in some cases [53,54]. Consistently, in this case, microscopic observations (as shown in Figure 18) revealed that cracks connect or propagate through inclusions. This further demonstrates that the presence of inclusions reduces material strength and induces the direction of crack propagation. According to previous studies [18,55], the inclusion ratings should be controlled at the level of 0.5 to avoid the adverse effects of inclusions on the strength and performance of the material.

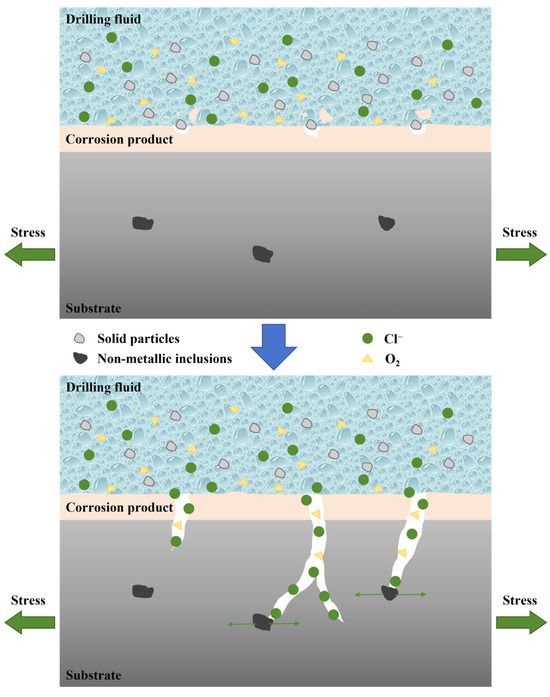

Figure 18.

Schematic diagram showing the SCC of pressure-resistant cylinder.

Finally, the analysis is based on the load-bearing conditions of the pressure-resistant cylinder. As introduced in the introduction, due to its special installation position, the pressure-resistant cylinder is connected to drilling tools at both its front and rear ends. Therefore, during drilling operations, the pressure-resistant cylinder is subjected to complex stresses, especially in well sections with high dogleg severity. In addition, since a dense passive film forms on the surface of the pressure-resistant cylinder, it is necessary to consider the stresses generated during the rupture-dissolution-regeneration cycle of the corrosion product film. This phenomenon, also known as SCC induced by passive film dissolution, has been widely reported in numerous studies. Zhang et al. [19] investigated an SCC case of super 13Cr tubing used in high-temperature and high-pressure (HTHP) gas wells and concluded that the tubing fracture was induced by SCC, with the core mechanism being the rupture of the corrosion product film. In another study, Zhang et al. [56] focused on the corrosion resistance of Mg-Al-Mn-Ca alloys and found that high aluminum solute content and trace Ce/Y alloying elements enhance the corrosion resistance of the material by reducing the Volta potential difference and forming a dense corrosion product film. However, such dense films are prone to severe rupture during the SCC process, thereby accelerating crack initiation. Chen et al. [57] studied the anodic dissolution-induced SCC behavior of flat specimens and U-shaped edge-notched specimens, revealing that the stress generated by the corrosion product film itself and the subsequent film rupture promote SCC initiation. Similarly, in this study, the high chromium content in the pressure-resistant cylinder facilitated the formation of a dense passive film on its surface, thereby inhibiting severe general corrosion. Nevertheless, in high-temperature environments, chloride ions in the drilling fluid pose a significant threat to this passive film. Under tensile stress, the passive film further ruptures, causing pitting corrosion and exposing the fresh underlying metal matrix. Due to the potential difference between the metal matrix and the corrosion product film, the matrix acts as the anode and undergoes continuous dissolution, followed by the reformation of a new corrosion product film. The stress concentration at the bottom of the pitting pits then causes the newly formed corrosion product film to rupture again, and this cyclic process repeats continuously. When the tensile stress exceeds the critical SCC threshold of the material, cracks initiate at the bottom of the pitting pits, ultimately leading to SCC failure.

In addition, studies have shown that under the synergistic effects of tensile stress, high-chloride ion environment erosion, and elevated temperature conditions, Cl-SCC gradually manifests through the process of crack initiation and propagation [16]. Residual stress is widely recognized as one of the key factors inducing stress corrosion cracking. Microcracks induced by residual stress can damage the protective oxide film on the metal surface, thereby creating channels for corrosive media to invade the material surface and crack tips [58]. Zhang et al. [58] investigated the effect of residual stress on the stress corrosion cracking characteristics of 316L stainless steel and found that higher residual stress leads to higher crack initiation rate and crack density. Ghosh et al. [59] explored the effect of residual stress generated during material processing on its stress corrosion cracking susceptibility, and their results showed that even in the absence of any external load, residual stress can still render austenitic stainless steel highly susceptible to chloride-induced stress corrosion cracking. Pal et al. [60] conducted stress corrosion cracking tests on F304 stainless steel in boiling magnesium chloride solution in accordance with the ASTM G36 standard [61], and observed that the specimens underwent complete fracture after 16 h of immersion, driven by residual stress. All the above studies indicate that residual stress accelerates the material degradation process and increases the crack propagation rate. Although the presence of residual stress was not directly observed in this case, residual stress is still a potential influencing factor for the initiation of stress corrosion cracking in the high-temperature (135 °C) and high-chloride ion environment. Therefore, to ensure the safe service of the pressure-resistant cylinder, residual stress deserves consideration.

In summary, the cracking of the pressure-resistant cylinder is the result of the synergistic effects of multiple factors. As illustrated in Figure 18, high-concentration chloride ions in the drilling fluid impair the protective effect of the passive film on the substrate, ultimately facilitating the formation of pitting corrosion pits. The formation of pitting pits induces significant stress concentration at their bottoms, which act as the initiation sites for SCC. The exposed metal substrate functions as the anode and undergoes continuous dissolution, promoting the cycle of passive film regeneration and rupture, and further elevating the stress level within the pitting pits. When the complex stresses exceed the SCC threshold of the material, cracks initiate from the bottoms of the pits and propagate in a transgranular mode under the combined influence of inclusions and stresses.

5. Measures and Recommendations

The research findings indicate that the corrosion-induced cracking failure on the surface of the pressure-resistant cylinder was caused by inherent defects in the substrate material itself, combined with exposure to drilling fluid containing high Cl− levels and harsh service conditions. To prevent similar failures from recurring, the following preventive measures are proposed:

(1) Material Selection: Austenitic stainless steels with superior resistance to SCC should be selected, such as grades with high Cr and Ni content, and low or ultra-low C content. Alternatively, the content of alloying elements like Cr, Ni, and Mo in existing materials can be increased. Cr enhances the stability of the passive film, while Mo significantly improves the material’s resistance to Cl− corrosion, reducing the occurrence of pitting and SCC.

(2) Material Processing: Attention should be paid to eliminating residual stresses and controlling non-metallic inclusions during material processing. Processes such as solution treatment or stress relief annealing can be applied to components to remove residual stresses introduced during manufacturing. Controlling non-metallic inclusions is a key aspect of material optimization. Smelting processes should be improved by adopting refining techniques (e.g., vacuum refining, argon-protected pouring) to reduce the content of non-metallic inclusions in the molten steel. Simultaneously, pouring and rolling processes should be optimized to ensure uniform distribution and refinement of inclusion sizes. Comprehensive testing of inclusion ratings, grain size, and other indicators should be conducted on incoming materials during tool acceptance to ensure the material quality meets the requirements for resisting SCC.

(3) Surface Protection: Enhance the surface protection treatment of the pressure-resistant cylinder to improve its corrosion resistance. Apply coatings resistant to high temperature, high pressure, and wear on the surface of the cylinder, such as using laser cladding technology to form a dense protective layer, preventing direct contact between the drilling fluid and the metal substrate.

(4) Drilling Fluid Control: Manage the Cl− content in the drilling fluid by optimizing the drilling fluid formulation, opting for low-chloride or chloride-free drilling fluids. Additionally, use purification equipment (e.g., centrifuges, desanders) to remove formation cuttings from the drilling fluid, ensuring that both Cl− content and solid particle levels are controlled within safe limits. Maintaining the drilling fluid pH within the alkaline range of 9–11 can promote the formation of a stable passive film on the cylinder surface, enhancing its protective performance. Furthermore, adding appropriate amounts of reducing agents or oxygen scavengers can lower the dissolved oxygen content in the drilling fluid, thereby reducing the accelerating effect of oxygen on corrosion.

6. Conclusions

This study investigated the corrosion-induced cracking failure of the pressure-resistant cylinder in the Measurement While Drilling tool of a rotary steerable system. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) The basic physical and chemical properties of the pressure-resistant cylinder meet the requirements. However, large-sized non-metallic inclusions are detected in its microstructure. The inclusion ratings exceed 0.5, which increases the susceptibility of the material to SCC.

(2) Multiple pitting corrosion pits are present on the surface of the pressure-resistant cylinder, with the observed pit depth ranging from 10 to 15 μm. Meanwhile, the average aspect ratio (depth/width) of cracks initiated from the bottoms of these pits was measured to be 76.97. A significant enrichment of O and Cl elements is detected along the crack propagation paths.

(3) The cracking of the pressure-resistant cylinder is attributed to the chloride ions in the drilling fluid, which impair the protective performance of the passive film and induce pitting corrosion. When the coupling effect of passive film dissolution and service stress exceeds the SCC threshold of the material, cracks initiate from the bottoms of the pitting pits and propagate in a transgranular mode under the combined influence of inclusions and stresses.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, conceptualization, project administration, Y.W.; writing—review and editing, software, resources, X.C.; validation, investigation, supervision, W.C.; formal analysis, visualization, W.P.; formal analysis, J.Z.; visualization, J.L.; data curation, H.Z.; methodology, conceptualization, visualization, D.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Yufei Wang, Xin Chen, Wei Chen, Wenxue Pu, Jiaxin Zeng are employed by Geosteering & Logging Research Institute, Sinopec Matrix Corporation. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- McMahon, T.P.; Larson, T.E.; Zhang, T.; Shuster, M. Geologic Characteristics, Exploration and Production Progress of Shale Oil and Gas in the United States: An Overview. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2024, 51, 925–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M.K.; Kishor, K.; Singh, A.K.; Kumar, A.; Mustapha, K.A.; Saxena, A. Multi-Analytical Assessment of Shale Gas Potential in the West Bokaro Basin, India: A Clean Energy Prospect. Energy Geosci. 2025, 6, 100434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.Z.; Zhou, Z.; Nie, H.K.; Zhang, L.F.; Song, T.; Liu, W.B.; Li, H.H.; Xu, Q.C.; Wei, S.Y.; Tao, S. Distribution Characteristics, Exploration and Development, Geological Theories Research Progress and Exploration Directions of Shale Gas in China. China Geol. 2022, 5, 110–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; He, X.; Li, X.; Li, K.; He, J.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, W. Shale Gas Exploration and Development in the Sichuan Basin: Progress, Challenge and Countermeasures. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2022, 9, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Feng, Y.; Zhao, L.; Li, N.; Luo, Z. Technical Status and Challenges of Shale Gas Development in Sichuan Basin, China. Petroleum 2015, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafarian, H.; Ameri, M.; Vaghasloo, Y.A.; Soleymanpour, J. Error Reduction of Tracking Planned Trajectory in a Thin Oil Layer Drilling Using Smart Rotary Steerable System. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 196, 107668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gao, D.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H. Study on Open-Hole Extended-Reach Limit Model Analysis for Horizontal Drilling in Shales. J. Nat. Gas. Sci. Eng. 2016, 34, 520–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C.P.S.; Saavedra, J.L.; Tunkiel, A.; Sui, D. Rotary Steerable Systems: Mathematical Modeling and Their Case Study. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2021, 11, 2743–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soeder, D.J. The Successful Development of Gas and Oil Resources from Shales in North America. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2018, 163, 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabifo, B.; Olakanmi, E.O.; Leso, T.P.; Prasad, R.V.S.; Setswalo, K.; Botes, A.; Ndeda, R.; Ematang, N.Y. Integrated Failure Analysis of Tri-Cone Drill Bits Using Experimental Techniques. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 182, 109977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Tong, K.; Fan, Z.H.; Yang, W.Z.; Liu, Q.; Li, H.; Zhao, J.L.; Cong, S. Failure Analysis of S135 Drill Pipe Body Fracture in a Well. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 145, 106998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Zeng, D.; Hu, S.; Zhou, X.; Lu, W.; Luo, J.; Fan, Y.; Meng, K. The Failure Patterns and Analysis Process of Drill Pipes in Oil and Gas Well: A Case Study of Fracture S135 Drill Pipe. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 138, 106171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, E.O.; Baldo, R.A.S.; Bessone, J.B. Corrosion of chromium plated rotor in drilling fluid. Surf. Coat. Technol. 1999, 122, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar, K.; Sababi, M. Failure assessment of the hard chrome coated rotors in the downhole drilling motors. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2012, 20, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wang, C.; Zheng, F.; Li, J.; Liu, G.; Zheng, S. Factors Affecting the Attenuation of Mud Positive Pulse Signals in Measurement While Drilling and Optimization Strategies. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2025, 247, 213726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakili, M.; Koutník, P.; Kohout, J.; Gholami, Z. Analysis, Assessment, and Mitigation of Stress Corrosion Cracking in Austenitic Stainless Steels in the Oil and Gas Sector: A Review. Surfaces 2024, 7, 589–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhu, Y. Full-Life Simulation of the Stress Corrosion Cracking Behaviour of the Pipeline Steel for Oil and Gas. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2026, 219, 105682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, A.; Long, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhao, M.; Xie, J.; Su, H.; Li, X.; Yuan, J.; Lei, X.; Yin, C.; et al. Stress Corrosion Cracking Behavior of Super 13Cr Tubing in Phosphate Packer Fluid of High Pressure High Temperature Gas Well. Eng. Fail Anal. 2022, 139, 106478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, W.; Liu, M.; Gao, W.; Shi, T. Stress Corrosion Crack Evaluation of Super 13Cr Tubing in High-Temperature and High-Pressure Gas Wells. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2019, 95, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 13298-2015; Inspection Methods of Microstructure for Metals. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2015.

- GB/T 10561-2023; Determination of Content of Nonmetallic Inclusions in Steel—Micrographic Method Using Standard Diagrams. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2023.

- GB/T 6394-2017; Determination of estimating the average grain size of metal. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2017.

- ISO 6892-1:2019; Metallic Materials—Tensile Testing—Part 1: Method of Test at Room Temperature. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Manuel, Q.A.L.; Noé, R.O.J.; Del Rosario, D.A.Y.; Ariadna, A.J.I.; Vicente, G.F.; Icoquih, Z.P. Analysis of the Physicochemical, Mechanical, and Electrochemical Parameters and Their Impact on the Internal and External SCC of Carbon Steel Pipelines. Materials 2020, 13, 5771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 4340.1-2024; Metallic Materials—Vickers Hardness Test—Part 1: Test Method. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2024.

- Zeng, D.; Luo, J.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, C.; Chen, X.; Zeng, W.; Chen, H.; Dong, B. Unraveling the Impact of Cr Content on the Corrosion of Tubing Steel in High CO2 and Low H2S Environments. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025, 34, 16244–16254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Petroleum Institute. API Spec 7-1; Specification for Rotary Drill Stem Elements; API Publishing Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mohtadi-Bonab, M.A. Effects of Different Parameters on Initiation and Propagation of Stress Corrosion Cracks in Pipeline Steels: A Review. Metals 2019, 9, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.T.; Li, Z.D.; Jiang, L.; Wang, X.; Xu, P.; Ma, Y.X.; Yan, Y.P.; Yang, C.F.; Yong, Q.L. An Investigation into the Role of Non-Metallic Inclusions in Cleavage Fracture of Medium Carbon Pearlitic Steels for High-Speed Railway Wheel. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 131, 105860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Park, Y.; Kang, B.; Huh, N.S. Failure Analysis of the Rotating Shaft in the Rail Grinding Car. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 159, 108100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhu, T.; Yang, B.; Xiao, S.; Yang, G. Failure Analysis of Stress Corrosion Cracking in Welded Structures of Aluminum Alloy Metro Body Traction Beam in Service. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 163, 108564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkaiam, L.; Hakimi, O.; Aghion, E. Stress Corrosion and Corrosion Fatigue of Biodegradable Mg-Zn-Nd-y-Zr Alloy in in-Vitro Conditions. Metals 2020, 10, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, E.A.; Giorgetti, V.; Júnior, C.A.d.S.; Marcomini, J.B.; Sordi, V.L.; Rovere, C.A.D. Stress Corrosion Cracking and Corrosion Fatigue Analysis of API X70 Steel Exposed to a Circulating Ethanol Environment. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2022, 200, 104846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, D.; Musuva, J.K.; Radon, J.C. The Significance of Stress Corrosion Cracking in Corrosion Fatigue Crack Growth Studies. Eng. Fract. Mech. 1981, 15, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.Y.; Wang, J.; Huang, Q.Y.; Xiao, Y.H.; Li, H.; Zhang, Q.H.; Liu, P.; Wu, L.K.; Cao, F.H. An Integrated In-Situ Micro-Electrochemical Investigation on the Corrosion Mechanism of Stress Corrosion Crack in X80 Pipeline Steel. Corros. Sci. 2026, 258, 113415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Zeng, D.; Xiao, G.; Shang, J.; Liu, Y.; Long, D.; He, Q.; Singh, A. Effect of Cl- Accumulation on Corrosion Behavior of Steels in H2S/CO2 Methyldiethanolamine (MDEA) Gas Sweetening Aqueous Solution. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2016, 30, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, G.; Fu, A.; Liu, Z.; Cao, X. The Corrosion and Tribological Behaviors of DLC Film in CO2 Saturated NaCl Solution with High Cl− Concentration. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2024, 144, 111016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, M.; Yang, L.; Liu, G. Study on Corrosion Behavior and Mechanism of Fe-Cr Alloy in Chloride-Containing Environments Based on Reactive Molecular Dynamics. Electrochim. Acta 2025, 543, 147576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Qu, H.J.; Mao, K.S.; Wharry, J.P. Chloride-Induced Stress Corrosion Crack Propagation Mechanisms in Austenitic Stainless Steel Are Mechanically Driven. Scr. Mater. 2025, 262, 116652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Luo, H.; Li, C.; Yan, B.; Liang, G. Hydrogen Charging-Induced Corrosion Behavior Evolution of an Additive-Manufactured Austenitic Stainless Steel in Sulfuric Acid Medium. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 178, 109753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Q.; Wu, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X. Long Term Semiconducting and Passive Film Properties of a Novel Dense FeCrMoCBY Amorphous Coating by Atmospheric Plasma Spraying. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 495, 143600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cheng, Y.F. Passive Film Growth on Carbon Steel and Its Nanoscale Features at Various Passivating Potentials. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 396, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Cui, H.; Huang, T.; Liang, B.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Liu, Z.; Du, C.; Li, X. Stress Corrosion Cracking Behavior and Mechanism of Stainless Steel Coiled Tubing Served for CO2 Flooding Injection Well in CCUS-EOR Environments. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 180, 109847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Du, C.; Wan, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, X. Influence of Sulfides on the Passivation Behavior of Titanium Alloy TA2 in Simulated Seawater Environments. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 458, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Wang, C.; Lu, H.; Suo, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H. Effect of Strain Rates on Stress Corrosion Sensitivity of 7085-T7452 Thick-Plate Friction Stir Welding Joint. Mater. Charact. 2024, 218, 114554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, X.; Andresen, P.L.; Rebak, R.B. Oxide Inclusions in Laser Additive Manufactured Stainless Steel and Their Effects on Impact Toughness and Stress Corrosion Cracking Behavior. J. Nucl. Mater. 2018, 499, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Zhou, C.; Chen, S.; Wang, R. Effects of Temperature and Pressure on Stress Corrosion Cracking Behavior of 310s Stainless Steel in Chloride Solution. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. (Engl. Ed.) 2017, 30, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Li, S.; Li, Z.; Xiao, X.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; He, C.; Yang, Y.; Yang, K.; Wang, Q. Corrosion-Fatigue Fracture Mechanisms in Q690qNH Steel: Dislocation Mediated Crack Tip Dissolution. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2025, 329, 111630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhou, W.; Kang, J. A Review of Crack Growth Models for Near-Neutral PH Stress Corrosion Cracking on Oil and Gas Pipelines. J. Infrastruct. Preserv. Resil. 2021, 2, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.F. Stress Corrosion Cracking of Pipelines; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Beavers, J.A.; Harle, B.A. Mechanisms of High-PH and near-Neutral-PH SCC of Underground Pipelines. J. Offshore Mech. Arct. Eng. 2001, 123, 54069911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; King, F.; Jack, T.R.; Wilmott, M.J. Environmental Aspects of Near-Neutral PH Stress Corrosion Cracking of Pipeline Steel. Metall. Mater. Trans. A Phys. Metall. Mater. Sci. 2002, 33, 1429–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, J.; Zhong, Y.; Shi, T.; Zhang, J.; Li, S. Failure Analysis on Aluminum Alloy Drill Pipe with Pits and Parallel Transverse Cracks. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 131, 105809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Luo, K.; Wang, J.; Feng, D.; Zhang, H.; Cao, X. Failure Analysis of an Offshore Drilling Casing under Harsh Working Conditions. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2021, 120, 105018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, N.; Zhao, M.; Wu, Z.; Wang, P.; Feng, C.; Xie, J.; Long, Y.; Song, W.; Xiong, M. Collapse Failure Analysis of S13Cr-110 Tubing in a High-Pressure and High-Temperature Gas Well. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 148, 107187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, D.; Cao, F.; Wang, C.; Li, M.X.; Yang, Y.; Zha, M. Negatively Correlated Corrosion and Stress Corrosion Cracking of Mg-Al-Mn-Ca Based Alloys. Corros. Sci. 2024, 227, 111747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Su, Y.; Volinsky, A.A. Cohesive Zone Modelling of Anodic Dissolution Stress Corrosion Cracking Induced by Corrosion Product Films. Philos. Mag. 2019, 99, 1575530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Fang, K.; Hu, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, X. Effect of Machining-Induced Surface Residual Stress on Initiation of Stress Corrosion Cracking in 316 Austenitic Stainless Steel. Corros. Sci. 2016, 108, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Rana, V.P.S.; Kain, V.; Mittal, V.; Baveja, S.K. Role of Residual Stresses Induced by Industrial Fabrication on Stress Corrosion Cracking Susceptibility of Austenitic Stainless Steel. Mater. Des. 2011, 32, 3823–3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S. Role of Residual Stresses Induced by U-Bending on Stress Corrosion Cracking Susceptibility of F304 Stainless Steel. Adv. Mater. Process. Technol. 2024, 10, 2165991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM G36; Standard Practice for Evaluating Stress-Corrosion-Cracking Resistance of Metals and Alloys in a Boiling Magnesium Chloride. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.