Abstract

Against the backdrop of continuously expanding global magnesium alloy applications and surging scrap generation, achieving efficient recycling and low-carbon regeneration of magnesium alloys has emerged as a key pathway for advancing green transformation in manufacturing. The AM50A recycled magnesium alloy was selected as the research subject, employing the attributional life cycle assessment (ALCA) methodology to systematically calculate its “cradle”-to-“gate” carbon footprint across three stages: raw material acquisition, transportation, and production. The results indicate that the carbon footprint of AM50A recycled magnesium alloy is 4.9399 kg CO2e/kg, with the production stage accounting for a significant 99.34% of emissions, identified as the primary source. The combined contribution from raw material acquisition and transportation stages is only 0.66%. Compared to magnesium alloys produced by the Pidgeon process, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions can be reduced by approximately 67.56% through the recycling process, highlighting its significant advantages in promoting low-carbon manufacturing and circular economic development for magnesium alloys. This study provides data support for the environmental performance assessment of recycled magnesium alloys and offers a scientific basis for optimizing energy conservation and emission reduction pathways in related industries.

1. Introduction

The density of metallic magnesium is 1.74 g/cm3, approximately two-thirds that of aluminum and one-fifth that of steel. Its significant advantages in lightweight applications are widely recognized. As a downstream product of magnesium, magnesium alloys feature low density, high specific strength, excellent machinability, and recyclability [1]. They are recognized as the lightest metal structural materials currently in practical application [2] and are widely used in the automotive industry, aerospace, electronics, and biomedical fields [3,4,5]. In recent years, the global demand for lightweight and high-performance materials has driven substantial expansion in magnesium alloy production and utilization [6]. China’s output reached 396,800 metric tons in 2024, reflecting a year-on-year growth of 14.95% [4]. Concurrently, the expanding application scope of magnesium alloys has led to a surge in waste generation, including process scrap from ingot casting production (where only 50% of metal feedstock is converted into finished castings) and end of life components [7], so the volume of discarded magnesium alloy components continues to rise. However, primary magnesium smelting exerts substantial environmental burdens due to its high energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions [8]. Given these challenges, magnesium alloy recycling is recognized as a critical pathway toward achieving resource sustainability and environmental protection [9,10].

As the world’s largest producer of primary magnesium and exporter of magnesium products, China has established an export-driven supply chain. Against the backdrop of global sustainable development and green low-carbon transformation, China’s magnesium industry has experienced rapid growth in foreign trade. However, this growth is accompanied by critically elevated energy intensity and persistent CO2 emission mitigation pressures [11]. Guo et al.’s research findings indicate that by 2050, China’s magnesium recycling potential is projected to exceed 4 million metric tons, with carbon dioxide emissions reductions surpassing 3 million metric tons [12]. According to the 2024 statistical report by the International Magnesium Association (IMA), magnesium alloy scrap can be 100% recycled. Due to reduced energy consumption, emissions from the Pidgeon process have decreased compared to 2011 levels. Production of magnesium by the Pidgeon process is a thermal reduction method that employs ferrosilicon as a reducing agent to convert calcined dolomite into metallic magnesium. The current average total GHG emissions for the Pidgeon magnesium process are reported at 28 kg CO2e/kg Mg [13], encompassing all upstream activities including ferrosilicon and fuel gas production. Specifically, the calcination stage contributes 6.7–9.1 kg CO2e/kg Mg, with the range depending on the energy source employed. Discrepancies in reported carbon intensity values for primary magnesium production often stem from variations in system boundaries, allocation methods for process by-products, and differences in energy mix composition. Notably, a 2013 life cycle assessment (LCA) of Israel’s primary magnesium electrolysis process revealed that greenhouse gas emissions are predominantly influenced by smelting energy consumption, while being partially offset by carbon credits attributed to process by-products. This system resulted in emissions of 14.0 kg CO2e per kilogram of magnesium produced [13]. This indicates that recycled magnesium alloys possess significant potential for energy conservation and emission reduction. However, domestic and international research has primarily focused on waste classification, recycling technologies, micro structural optimization, and performance optimization [14,15,16], with emphasis placed on enhancing magnesium alloy material properties and improving production processes [4,17,18]. Research addressing the environmental impact of magnesium alloys remains relatively underdeveloped [19]. While preliminary studies have addressed China’s magnesium recycling potential and its environmental implications, including GHG emissions from automotive applications [12], comprehensive methodological frameworks and robust datasets remain underdeveloped. Further systematic investigation is imperative to fully characterize the environmental impact mechanisms and quantify the emission reduction potential of recycled magnesium alloys.

The concept of carbon footprint was first introduced in the United Kingdom as a systematic framework for quantifying direct and indirect greenhouse gas emissions associated with a product or service throughout its entire life cycle—encompassing raw material extraction, manufacturing, transportation, use, and disposal [20]. It has since evolved into a vital instrument for evaluating sustainability performance across multiple industries, including steel, chemicals, electronics, and automotive manufacturing [21,22]. Enterprises increasingly rely on carbon footprint assessments to formulate emission reduction strategies, optimize production processes, and enhance their environmental competitiveness. Recent years have witnessed growing research attention on the carbon footprint of magnesium alloy components. A study investigating the environmental impact of substituting aluminum alloy hub with magnesium alloy hub demonstrated that this substitution reduces global warming potential (GWP) by 39.6% and human toxicity potential (HTP) by 24.0% compared to aluminum alloy hub [17]. Moreover, a life cycle assessment comparison study of magnesium alloy rear hatchbacks indicated that under conventional, non-green production models, the carbon emission intensity of magnesium alloy components over their entire life cycle narrows considerably compared to carbon steel components—and may even exceed them in certain scenarios [8]. This finding underscores the decisive influence of energy structure and process selection during production on the overall carbon footprint of magnesium alloys. Conversely, when magnesium alloys are produced using green processes—such as utilizing renewable energy, enhancing electrolytic efficiency, and strengthening magnesium scrap recycling—their carbon footprint advantage becomes fully evident. Under such conditions, emissions fall significantly below those of traditional carbon steel components, demonstrating substantial low-carbon competitiveness. Therefore, the carbon reduction potential of magnesium alloys is not inherent but highly dependent on the adoption of clean production technologies and the establishment of circular economy systems.

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a systematic methodology for evaluating the resource consumption and environmental impacts of products or services across their entire life cycle [22]. The analysis encompasses all stages, including raw material extraction, production, processing, transportation, use, and final disposal. This approach is distinguished by its comprehensive coverage and rigorous logical coherence. LCA methodologies are fundamentally categorized into attributional life cycle assessment (ALCA) and consequential life cycle assessment (CLCA). ALCA primarily quantifies the directly attributable input resources, output emissions, and environmental burdens throughout a product’s entire life cycle. Its core methodological advantage lies in precisely identifying the key emission hotspots within a specific product system. For instance, in the case of AM50A recycled magnesium alloy production, ALCA enables stage-wise comparison of potential environmental impacts through direct process data analysis from stages such as raw material acquisition, transportation, and energy consumption. In contrast, CLCA transcends the boundaries of individual product systems by constructing dynamic system models to assess the indirect environmental effects of decision-making scenarios. This methodological extension makes it particularly suitable for dynamic or long-term strategic decision-making, accounting for system-level interactions and market responses [23]. Applying LCA to evaluate the lifecycle carbon footprint of recycled magnesium alloys holds significant implications. First, this approach enables the systematic quantification of the resource and environmental impacts throughout the “cradle”-to-“gate” stage and the entire life cycle of these alloys. It also facilitates a detailed characterization of the structure and distribution of key environmental indicators, such as carbon footprint and cumulative energy demand. Second, a comparative analysis with conventional primary magnesium production can scientifically validate the substantial emission reduction benefits achieved by recycling magnesium alloy scrap. This provides robust data to accurately quantify its low-carbon value. Finally, in the current research context, systematic LCA studies are well-positioned to address the existing literature gap—specifically, the lack of standardized assessments of the environmental performance of recycled magnesium alloys, particularly concerning their full life cycle carbon footprint. Therefore, such studies will establish a solid scientific foundation to support industrial green transformation and evidence-based policy formulation.

This study employs the ALCA methodology and introduces, for the first time, the use of waste AM50A magnesium alloy—commonly applied in the automotive sector—as a raw material for producing recycled magnesium alloy. Using the production of 1 kg of recycled AM50A as the functional unit, the carbon footprint is quantified across the full process chain, encompassing raw material acquisition, transportation, and the manufacturing of recycled AM50A products. The system boundary follows a “cradle”-to-“gate” approach.

This study employs a basic ALCA model with a cut-off approach, where on-site waste does not allocate carbon footprint. By developing a life cycle carbon footprint accounting model specific to AM50A recycled magnesium alloy, this work systematically identifies key emission hotspots throughout the process, from scrap recovery and remelting, refining to the preparation of the recycled alloy. These insights provide a scientific basis for optimizing recycling pathways and reducing environmental impacts. Furthermore, the study supplies fundamental data for greenhouse gas emission studies and carbon verification, supporting macro-level decision-making in energy conservation and emission reduction in China. Based on the findings, countermeasures are proposed to foster green and ecological development of the magnesium industry, contributing strategic value to the low-carbon transition of manufacturing and the achievement of China’s “dual carbon” goals.

2. Experiments and Methods

2.1. System Boundary

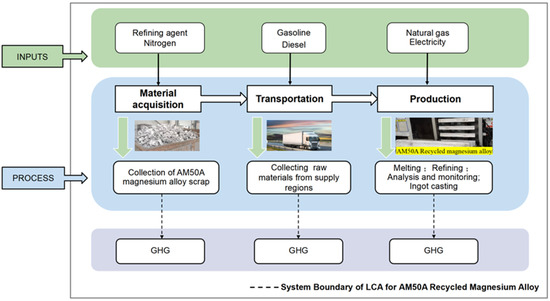

The functional unit was established as the production of 1 kg of AM50A recycled magnesium alloy. The preparation process of AM50A recycled magnesium alloy encompasses the acquisition of raw and auxiliary materials, their transportation, and the product manufacturing process. The primary feedstock comprises in-house generated ingot casting scrap exhibiting optimal recycling characteristics including clean surfaces, absence of oil contamination, and negligible corrosion. The high-efficiency iron removal recycling process for AM50A magnesium alloy [24] was adopted as the production method. The study adopted a cradle-to-gate system boundary. The system boundary is defined using a “cradle”-to-“gate” approach, encompassing the consumption of raw materials, auxiliary materials, and energy from the collection of original AM50A magnesium alloy scrap through to the production of recycled AM50A alloy. Excluded were the production and maintenance of manufacturing equipment, product transportation, recovery, disposal, and end-of-life processes. The inclusion/exclusion criteria were based on the mass ratio of each material input to the product mass or total process input. Upstream production data may be omitted for materials constituting less than 1% of the product mass, or for those containing rare, precious, or high-purity components constituting less than 0.1%. The total mass of omitted materials did not exceed 5%. To meet data quality requirements and ensure reliability, this study prioritized primary data obtained directly from manufacturers and upstream suppliers. Such primary data were acquired through field investigation, collection, and organization by the research team. Where primary data were unavailable, regional average databases or those reflecting specific technical conditions were used as substitutes. The assessment references the principles of ISO 14067:2018 [25], and GB/T 24067-2024 [26]. The detailed calculation boundaries are visually represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

System Boundary of LCA for AM50A Recycled Magnesium Alloy.

2.2. Life Cycle Inventory

2.2.1. Raw Material Acquisition

In the production system for AM50A recycled magnesium alloy, the core raw material is limited to solid magnesium alloy waste generated by other production lines within the same plant. This waste is directly transferred to the recycling line via an internal handling system, achieving closed-loop recycling. According to LCA principles for defining system boundaries and avoiding double-counting, the upstream production processes of this solid waste fall within the plant’s system boundary. Activity data and corresponding environmental impacts from internal processes, such as collection and transfer, have been fully accounted for in the energy and material consumption of the upstream virgin magnesium alloy production process. Therefore, in line with the closed-loop allocation procedure stipulated in GB/T 24067-2024 [26], the AM50A recycled magnesium alloy qualifies as a closed-loop product system. Under these conditions, since recycled material substitutes for virgin material, no allocation is required. For the carbon footprint calculation of the current recycling stage, the recycled material utilization rate was set at 100%, and the emission factor for this magnesium alloy scrap was defined as zero. This approach objectively reflects its status as an intermediate product within the plant and underscores the advantage of the recycling process in avoiding carbon emissions at the source.

Beyond the primary raw material of magnesium alloy scrap, the production of AM50A recycled magnesium alloy requires two key auxiliary materials: RJ-2 refining agent and nitrogen gas (N2). The RJ-2 refining agent is employed during the melting process to adsorb [27], dissolve, and separate [28] non-metallic inclusions and harmful elements from the molten magnesium, significantly improving the purity and mechanical properties of the final alloy. N2 serves as a protective gas, introduced into the smelting furnace and casting areas to effectively prevent oxidation and combustion of the molten magnesium at high temperatures [29], thereby ensuring production safety and final product quality. As both auxiliary materials are procured externally, the full life cycle carbon emissions of the RJ-2 refining agent and N2, encompassing production, filling, and transportation, must be independently calculated using corresponding emission factors and ultimately included in the product’s total carbon footprint. Information on the sources and regional representativeness of the greenhouse gas emission factors for the procured RJ-2 refining agent and N2 is provided in Table 1.

where represents GHG emissions during the raw material acquisition phase; represents the weight of product ; denotes the carbon emission coefficients for the production of raw material .

Table 1.

Carbon Footprint Coefficients of Different Raw Materials During Production Stages.

2.2.2. Raw Material Transportation

The primary raw material for AM50A recycled magnesium alloy is solid waste generated from other production lines within the same facility. This waste is transported from the original magnesium alloy production line to the recycled magnesium alloy smelting site. Activity data and corresponding environmental impacts associated with internal processes such as collection, transfer, and treatment have been fully accounted for within the energy and material consumption of the upstream virgin magnesium alloy product waste treatment process. In accordance with the closed-loop allocation procedure requirements of GB/T 24067-2024 [26], the AM50A recycled magnesium alloy constitutes a closed-loop product system. Based on the system boundary delineation principles and double-counting avoidance requirements within the LCA methodology, carbon footprint allocation need not be re-performed in this context.

The primary auxiliary materials, namely the RJ-2 refining agent and N2, were procured from external suppliers. The transportation distances for both materials are based on data provided by the suppliers. Information pertaining to the origin and regional representativeness of their greenhouse gas emission factors is detailed in Table 2. GHG emissions from raw material transportation are calculated by:

where represents GHG emissions from raw material transportation; denotes the weight of product ; is the carbon emission coefficients for transporting raw material .

Table 2.

Carbon Footprint Coefficients for Transporting Different Raw Materials.

2.2.3. AM50A Recycled Magnesium Alloy Production

The production of AM50A recycled magnesium alloy consists of four consecutive stages: melting, refining, purity monitoring, and ingot casting. The AM50A magnesium alloy high-efficiency iron removal refining process is detailed in reference (Mg 95.2%, Al 4.4%, Mn 0.24%, Fe 0.08%, Zn 0.05%, others) [24]. The primary energy sources utilized are natural gas and electricity, as shown in Table 3. Further lifecycle inventory data has been refined in the Supplementary Materials.

Table 3.

Carbon Footprint Coefficients for Different Energy Sources.

- (1)

- Melting

The process is conducted in a dedicated melting furnace heated by natural gas to approximately 720 °C. Under this temperature, magnesium alloy scrap is transformed into a homogeneous liquid. To prevent oxidation, a protective atmosphere of nitrogen—supplied from external bottles—is maintained inside the sealed furnace. At standard temperature and pressure, N2 has a density similar to air. However, under specific process conditions, by carefully controlling the flow rate and pressure of the N2 introduced, an effective surface shielding layer can be formed on the surface of the molten magnesium alloy. This layer protects the magnesium alloy from oxidation and combustion.

- (2)

- Refining

Once fully melted, the optimal refining temperature for AM50A magnesium alloy Fe removal is 670 °C, the optimal refining time is 40 min, and the optimal refining agent ratio is 1.5%. The Fe ion removal rate of AM50A Mg alloy refined by the optimal refining process can reach up to 96.20% [24]. Under constant temperature and agitation, the agent adsorbs and suspends non-metallic inclusions and impurities, allowing them to be separated from the melt. This refining stage is maintained for a set duration to achieve thorough purification and improve alloy purity.

- (3)

- Melt purity analysis and monitoring

After refining, melt samples are extracted and analyzed to evaluate key quality indicators, including chemical composition, gas content, and inclusion levels. This step serves as a critical quality control checkpoint. Only qualified melts are approved for the subsequent ingot casting stage.

- (4)

- Ingot casting

The qualified molten alloy is transferred via a pump to the injection chamber of a cold-chamber ingot casting machine. A metered quantity of the melt is injected into the shot sleeve and held for approximately one second to stabilize. It is then forced at high pressure into a preheated mold cavity, where it rapidly solidifies into the desired ingot shape. The solidified ingot is finally extracted by an integrated robotic arm, completing the production cycle.

GHG emissions of the AM50A recycled magnesium alloy during the production process are calculated by:

where represents GHG emissions from energy consumption per kg of AM50A recycled magnesium alloy produced; denotes the consumption of energy source ; is the carbon emission coefficient for energy source .

3. Results

3.1. Carbon Footprint of AM50A Recycled Magnesium Alloy

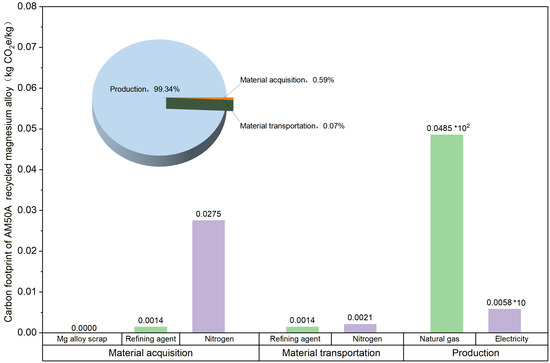

The LCA results demonstrate that producing 1 kg of recycled AM50A magnesium alloy generates 4.9399 kg CO2e emissions under cradle-to-gate system boundaries (Figure 2 and Table 4). Regarding the contribution of each stage to the carbon footprint, the raw material acquisition stage accounted for 0.59% of total carbon emissions, the transportation stage only 0.07%, while the production stage dominated with 99.34%, identified as the absolute primary source of carbon emissions.

Figure 2.

Carbon Footprint Structure of AM50A Recycled Magnesium Alloy.

Table 4.

Detailed Carbon Emissions per Functional Unit for AM50A Magnesium Alloy.

The adopted LCA methodology excluded the upstream carbon allocation for magnesium alloy scrap in this study, making production-phase energy consumption (natural gas and electricity) the sole emission source. Compared to the product carbon footprint report of Shanxi Bada Magnesium Co., Ltd., which employs the Pidgeon process to produce magnesium alloy ingots (AM50A), the carbon footprint per kilogram of magnesium alloy ingot produced is 15.2256 kg CO2e (the system boundary is defined as cradle-to-gate, which includes the upstream manufacturing of raw materials, the manufacturing of packaging materials, transportation, and the production of the magnesium alloy product). To ensure comparability, the carbon footprint associated with packaging manufacturing (0.0128 kg CO2e) was excluded from the analysis, as it constituted only 0.08% of the total product footprint (15.2384 kg CO2e). Among the considered processes, upstream raw material manufacturing was the most significant contributor, accounting for 6.4195 kg CO2e or 42.16% of the total carbon footprint.) [31]. The total carbon footprint of the recycled AM50A magnesium alloy in this study was approximately 67.56% lower, the proportion of carbon footprint attributable to the raw material acquisition stage decreased from 42.16% to 0.59%, quantitatively validating the GHG reduction potential of scrap-based recycling.

3.1.1. GHG Emissions During Raw Material Acquisition

The production of 1 kg of AM50A recycled magnesium alloy has a material input of 1.0048 kg magnesium alloy scrap, 0.0150 kg RJ-2 refining agent, and 0.0200 kg nitrogen. Based on established life cycle assessment (LCA) methodologies and corresponding emission factors, the carbon emissions attributed specifically to this raw material acquisition stage amounted to merely 0.0289 kg CO2e. According to the International Magnesium Association (IMA)’s 2024 report on the carbon footprint of magnesium production and the life cycle assessment of magnesium component applications [13], the average greenhouse gas emissions range for traditional primary magnesium production (such as that produced by the Pigeon process or electrolytic magnesium processes) was assessed to be 5.3–28 kgCO2e/kg. When the system boundary is defined as cradle-to-gate, one type of primary magnesium produced by electrolytic magnesium plants utilizes magnesium chloride (MgCl2) brine as feedstock, where the brine is a waste product from a nearby enterprise. Due to the further utilization of chlorine gas—a by-product of the electrolytic magnesium production process—and the resulting carbon credits, coupled with the use of renewable energy, the total emissions for magnesium electrolysis can be reduced to 5.3 kg CO2e per kilogram of magnesium. In contrast, the Pidgeon process achieved an average total emissions level of 28 kg CO2e, encompassing all upstream processes and utilizing conventional energy sources. This disparity primarily stems from differing magnesium smelting techniques, variations in energy sources employed, and whether by-products or resource recycling are incorporated into the process. The magnesium alloy scrap recycling process studied here directly utilizes scrap generated within the facility, thereby bypassing energy-intensive and greenhouse gas-intensive stages of primary magnesium smelting, such as ore mining, brine processing, or electrolytic reactions. Furthermore, reusing scrap reduces transportation and processing steps in the raw material supply chain, further enhancing carbon reduction during the magnesium alloy raw material acquisition phase. This highlights the significant potential of recycled magnesium alloys in advancing low-carbon manufacturing and the circular economy.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate that recycled magnesium alloys can effectively decouple material production from the traditionally associated high levels of carbon emissions. This establishes a viable and scalable low-carbon manufacturing strategy.

3.1.2. GHG Emissions During Raw Material Transportation

As illustrated in Figure 2, the transportation phase constitutes a negligible portion of the total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the life cycle of AM50A recycled magnesium alloy, amounting to only 0.0035 kg CO2e per functional unit. A detailed breakdown revealed that the transport of nitrogen is the dominant contributor, responsible for approximately 60% of the emissions from this stage, a consequence of its logistics relying on heavy-duty diesel trucks. At the same distance, replacing fuel-powered vehicles with new energy transport vehicles would further reduce carbon emissions during the transportation phase. The magnesium alloy scrap used in the production of AM50A recycled magnesium alloy primarily originates from waste generated by other production lines within the same facility, eliminating the need for external procurement. This approach avoids greenhouse gas emissions associated with the procurement and transportation of raw materials.

The analysis of auxiliary materials further clarifies this emission profile: the RJ-2 refining agent, sourced from Henan and transported via 8-ton gasoline trucks, had a marginal impact on the overall footprint. The primary emission source was conclusively identified as the locally sourced nitrogen from Chongqing, which, despite its short transport distance, is delivered using 30-t diesel trucks with a higher emission intensity. This analysis reveals that transportation carbon footprints are predominantly determined by auxiliary material logistics and vehicle selection.

3.1.3. GHG Emissions During Production

The production of AM50A recycled magnesium alloy is characterized by a GHG emission profile dominated by energy consumption, specifically from natural gas and electricity. Based on operational data, the manufacturing of one kilogram of this alloy requires 2.17 m3 of natural gas and 0.11 kWh of electricity. As illustrated in Figure 2, the production phase generates total GHG emissions of 4.9075 kg CO2e, with natural gas combustion accounting for 98.83% (4.85 kg CO2e) of this total, underscoring its role as the primary emission source. Magnesium alloy production demonstrates significant natural gas dependency due to its inherent thermal processing requirements. The smelting process necessitates maintaining temperatures at 700–800 °C for effective metal liquefaction and slag removal. Natural gas combustion provides high-temperature heat sources with superior overall energy efficiency compared to electricity, justifying its relatively high consumption. Although electricity consumption accounts for a smaller proportion and is primarily used to power production equipment, it remains a non-negligible component of carbon emissions.

Under the current production process framework, in addition to advancing energy-saving technological innovations, it is essential to optimize energy management practices. Specifically, the adoption of third-generation regenerative combustion systems—capable of achieving up to 95% waste heat recovery—can significantly reduce natural gas consumption. Assuming a 50% reduction in natural gas consumption, the total carbon footprint per functional unit of recycled magnesium alloy products could be reduced by approximately 2.00 kg CO2e. Enhancing the recovery and utilization of waste heat and pressure, along with implementing refined energy control strategies, will further improve the overall energy efficiency. The transition to clean energy also presents a viable pathway for decarbonization. This includes exploring green hydrogen as an alternative heat source for smelting, leveraging its zero-carbon combustion characteristics, and assessing electric melting technologies powered by renewable electricity to replace natural gas-based thermal processes. Additionally, automated control can shorten insulation time to minimize energy waste. These measures are expected to play a critical role in reducing greenhouse gas emissions during the production phase.

3.2. Uncertainty Analysis

The calculation of data uncertainty in this study was based on the DQI methodology [32]. This methodology employs a weighted and composite assessment index to synthesize multiple dimensions and indicators of data quality, including technical representativeness, geographical representativeness, and temporal representativeness, thereby providing a semi-quantitative evaluation of data quality. This yields a comprehensive data quality index reflecting the degree of data uncertainty. Each qualitative data quality indicator undergoes evaluation and weighting, culminating in a numerical data quality metric. This enables the quantification of data uncertainty, facilitating comparative analysis based on specific values to support quantitative data analysis and decision-making.

The uncertainty formula are calculated by:

where U1–U5 are the uncertainties of the five data quality indicators, Ui is the uncertainty of data quality indicator i, Ub is fundamental uncertainty. Ud,i is the data-related uncertainty of i and Ub is the fundamental uncertainty of i.

According to the comprehensive uncertainty analysis presented in Table 5, the raw material transportation stage was identified as exhibiting the highest data-related uncertainty (Ud,i = 0.0534). This uncertainty level was determined to be 23.3% higher than that of the raw material acquisition stage (Ud,i = 0.0433) and 36.6% higher than the energy usage stage (Ud,i = 0.0391). The elevated uncertainty in transportation was attributed to its Level 3 ratings in both technical and geographical representativeness, which were found to be the highest among all assessed stages. Consequently, this stage was confirmed as a primary contributor to overall carbon footprint calculation uncertainty. Based on these findings, improving data quality in the transportation phase was identified as a key strategic focus for reducing overall uncertainty in carbon footprint assessments.

Table 5.

Uncertainty quantification results of the Carbon Footprint for the AM50A Recycled Magnesium Alloy.

4. Conclusions

Recycled magnesium alloys demonstrate substantial carbon reduction potential, with AM50A recycled magnesium alloy exhibiting a carbon footprint of 4.9399 kg CO2e/kg, representing a 67.56% reduction compared to conventional Pidgeon process alloys (15.2256 kg CO2e/kg). This reduction primarily stems from the direct utilization of magnesium alloy scrap, eliminating energy-intensive and GHG emission-intensive processes inherent in primary magnesium smelting. It also reflects the increasing maturity of recycled magnesium alloy manufacturing processes, which now possess the conditions for large-scale implementation.

GHG emissions are highly concentrated in the production stage (4.85 kg CO2e/kg), accounting for 99.34% of total emissions, with natural gas combustion contributing 98.83% and electricity contributing 1.17% of these GHG emissions. Due to the absence of upstream GHG emissions from scrap materials, the raw material acquisition and transportation stage accounts for only 0.66% of total GHG emissions, highlighting the low-carbon characteristics of the recycled process in the raw material phase. However, the transportation segment demonstrates elevated uncertainty levels (Ud,i = 0.0534), as identified in Table 5, with modal selection significantly influencing the overall carbon footprint estimation. Consequently, optimizing transport modal selection emerges as a pivotal intervention point for enhancing the accuracy of carbon footprint assessments. As a major producer and consumer of magnesium alloys, China possesses abundant magnesium alloy scrap resources, providing a material foundation for advancing recycled magnesium alloy development.

Currently, systematic research and data accumulation on the greenhouse gas reduction potential of recycled magnesium alloys remain insufficient. Establishing a more comprehensive LCA system and supporting database is particularly urgent. Future research should focus on establishing a unified carbon footprint accounting standard for recycled magnesium alloys, which is essential. Future efforts should prioritize short-term operational improvements, including enhanced waste heat recovery, furnace insulation optimization, reduced nitrogen consumption, and shortened material supply distances. These can be followed by mid-term strategies such as green power procurement agreements, pilot-scale electric melting trials, and process automation to minimize idle time. In the long-term, developing hydrogen-based heat treatment processes, on-site nitrogen generation via pressure swing adsorption, and logistics emission reductions will be critical. Such a phased approach, coupled with industrial chain collaboration and scalable scrap recycling networks, will fully unlock the emission reduction potential of recycled magnesium alloys in support of green manufacturing and circular economy objectives.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pr14010044/s1, Table S1: Overall input and output data for raw material acquisition; Table S2: Overall input and output data for raw material transportation; Table S3: Overall input and output data for AM50A recycled magnesium alloy production; Table S4: Uncertainty quantification results of the Carbon Footprint for the AM50A Recycled Magnesium Alloy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.Z., C.G. and W.Z.; methodology, Q.Z. and Y.M.; software, X.D. and G.F.; validation, S.J. and W.Z.; formal analysis, Q.Z., B.L., Z.C. and Y.M.; investigation, Q.Z. and S.J.; resources, Q.Z.; data curation, Q.Z. and Y.M.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.Z. and Y.M.; writing—review and editing, X.Y. and W.Z.; visualization, Q.Z.; supervision, C.G.; project administration and funding acquisition, W.Z. and X.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Chongqing Technical Innovation and Application Development Special Project (grant no. cstc2021jscx-dxwtBX0022).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

Thank you for the support from Chongqing Technical Innovation and Application Development.

Conflicts of Interest

Qingshuang Zhang, Gai Fu, Xing Deng, Wang Zhou and Xiaowen Yu are employed by the company Chongqing CEPREI Industrial Technology Research Institute Co., Ltd. Shaowei Jia and Cong Gao are employed by the company Chongqing Changan Automobile Co. Ltd. Yalan Mao, Bolin Luo and Zhao Chen are employed by the company CEPREI Innovation (Chongqing) Technology Co., Ltd.

References

- Wang, G.G.; Weiler, J.P. Recent developments in high-pressure die-cast magnesium alloys for automotive and future applications. J. Magnes. Alloys 2023, 11, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Tian, Y.; Yang, B.; Xu, B.Q.; Wu, J.; Wang, L.P. Progress on recycling of waste magnesium alloys. Chin. J. Nonferrous Met. 2024, 34, 3274–3293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Li, X. Development and application of magnesium alloy parts for automotive OEMS: A review. J. Magnes. Alloys 2023, 11, 15–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Yu, Z.; Yi, F.; He, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, Z.; Zhao, G.; Tiwari, S.K. Cleaner production techniques in magnesium alloy recycling Optimizing. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1026, 180083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Song, J.; Zhang, A.; You, G.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, B.; Qin, X.; Xu, C.; Pan, F. Progress and prospects in Mg-alloy super-sized high pressure die casting for automotive structural components. J. Magnes. Alloys 2023, 11, 4166–4180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Duo, X. Recycling and regeneration analysis of magnesium alloy waste. Sci. Technol. Innov. 2015, 15, 126+128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Qi, W.; Wang, J.; Li, Y. The progress of solid state recycling magnesium alloy. Mater. Res. Appl. 2015, 9, 78–84. [Google Scholar]

- Van-Tri, L.; Amal, R.; Scott, J.A.; Ehrenberger, S.; Tran, T. A comparison of carbon footprints of magnesium oxide and magnesium hydroxide produced from conventional processes. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 202, 1035–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liang, D.; Yu, R.; Wang, M.; Tian, Y.; Ma, T.; Yang, B.; Xu, B.; Jiang, W. Progress and prospects in magnesium alloy scrap recycling. J. Magnes. Alloys 2024, 12, 4828–4867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, A. China’s goal of achieving carbon peak by 2030 and its main approaches. J. Beijing Univ. Technol. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 21, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Lu, C.; Tang, C.; Kong, Y.; Xue, B. The carbon footprint in the production process of raw magnesium in China. J. Liaoning Univ. (Nat.) 2020, 47, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Geng, Y.; Zhou, L.; Biao, Z.; Ding, X. Uncovering magnesium recovery potential and correspondingenvironmental impacts mitigation in China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 112, 107785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMA. The International Magnesium Association Releases Carbon Footprint of Magnesium Production and Life Cycle Assessment of Magnesium Component Applications. China Nonferrous Metals News 23 March 2021. Available online: https://www.cnmn.com.cn/ShowNews1.aspx?id=426701 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Zhan, L.; Kong, C.; Zhao, C.; Cui, X.; Zhang, L.; Song, Y.; Lu, Y.; Xia, L.; Ma, K.; Yang, H.; et al. Recent advances on magnesium alloys for automotive cabin components materials, applications, and challenges. J. Mater. Res. Mater. Res. Technol.-JMRT 2025, 36, 9924–9961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Ayoub, I.; He, J.; Yang, J.; Zhang, H.; Hao, Q.; Cai, Z.; Ola, O.; Tiwari, S.K. Magnesium alloys wiht rare-earth elements: Research trends applications, and future prospect. J. Magnes. Alloys 2025, 13, 3524–3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M. Study on Microstructure and Mechanical Property of AZ91D Magnesium Alloy Prepared by Solid State Recycling. Ph.D. Thesis, Harbin University of Science and Technology, Harbin, China, 2008. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=BbvBZ4vy5aR-X7ZasfpUYakHg1UpL7tOQfb6H8JeB_hMBUKOV0jA2nLKhjTd0G5xd3z_sn1ptYkaFLIlhVbK1Pw_IYxcyqeO3xZw2gyogBqFjTMSTHFfStABiX7poADg1pPC340sTKCk_WXhkRC4nAhLX9JK_vAND3qvCaiDkIeqOTG2FZdNCw==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Yi, Q.; Tang, C. Environmental impact assessment of magnesium alloyautomobile hub based on life cycle assessment. J. Cent. South Univ. 2018, 25, 1870–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R. Quality Control of Recycling Magnesium Alloy Ingot and the Casting Machine Design. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2007. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=BbvBZ4vy5aRyYFv7Oe_utb3K3BXsWSp79vcaq4KfpJZ7R6gWSS9cQTOLs1USfuF120uZK3jgZCdBFhEI-TAxWxwttd0TlCXYq6fJ4rFphAleeH_1WciOZD3B1eDKSBo80lQ168Y1MzlDw3MGCii_IeMSgDTv6RirxBvPCRaFeo3sn_QJDsd0ig==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Guo, Y.; Xue, H.; Lei, L. Characteristics of magensium alloy products processing technology and pollution control. Environ. Eng. 2016, 34, 460–463. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, L.A.; Cadarso, M.A.; Zafrilla, J.; Arce, G. The carbon footprint of the U.S. multinationals’ foreign affiliates. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Zhang, T.; Shen, X.; Ma, X.; Hong, J. Development of life cycle assessment method. Resour. Sci. 2021, 43, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, L.; Pang, M. A review on hybrid life cycle assessment:development and application. J. Nat. Resour. 2015, 30, 1232–1242. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, S.; Li, S. Case analysis of GHG emission and reduction from food consumption of Beijing relish restaurant based on life cycle. Clim. Change Res. 2021, 17, 140–150. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Zhou, C.; Liu, W.; Chen, S.; Gao, C.; Jia, S.; Yu, X.; Zhou, W.; Luo, B.; Zhang, Q. Research on Fe removal, regeneration process, and mechanical properties of Mg alloy AM50A. Crystals 2024, 14, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14067:2018; Greenhouse Gases—Carbon Footprint of Products—Requirements and Guidelines for Quantification. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- GB/T 24067-2024; Greenhouse Gases—Carbon Footprint of Products—Requirements and Guidelines for Quantification. China National Institute of Standardisation: Beijing, China, 2024.

- Zhang, H.; Bai, P.; Li, S. Study on purifying treatment Technologies of Aluminum and Aluminum Alloy. Res. Into Heat Treat. Process. Mater. 2009, 7, 126–129. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, T.; Li, X. Research on the process, energy consumption and carbon emissions of different magnesium refining processes. Materials 2023, 16, 3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, P. Research on control technology of impurity ironand aluminum content in electrolytic magnesium. Light Met. 2025, 2, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MEE. Announcement No. 33 of 2024 Announcement on the Release of the 2022 Power Sector Carbon Dioxide Emission Coefficients by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment and National Bureau of Statistics. 2024. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/xxgk2018/xxgk/xxgk01/202412/t20241226_1099413.html (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Bada, M.C.L. Carbon Footprint Assessment Report for Products of Shanxi Bada Magnesium Co., Ltd. 2025. Available online: http://www.sxbada.com/industry/71 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Wang, J.; Sha, C.; Ly, S.; Wang, H.; Sun, Y.; Guo, M. Life cycle carbon emissions and an uncertainty analysis of recycled Asphalt Mixtures. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.