Abstract

The enrichment laws and key controlling factors of coalbed methane (CBM) in the Xishanyao Formation of the Hedong mining area remain unclear, restricting exploration progress. Based on well data and experimental analyses, this study investigates CBM enrichment characteristics and geological controls using genetic identification diagrams. Results demonstrate that CBM exhibits a “high in northwest and low in southeast” planar distribution. Vertically, CBM content is extremely low above 360 m due to weathering oxidation and burnt zone effects, increases within the 360–950 m interval (peaking at 750–950 m), and declines from 950 to 1200 m because of limited gas contribution. Genetic analysis indicates predominantly primary biogenic gas, with a minor component of early thermogenic gas. Enrichment is controlled by structure and hydrogeology: the medium-depth range (358–936 m) on the northern syncline limb and western part of the northern monoclinal zone forms a high-efficiency enrichment zone due to compressive stress from reverse faults and high mineralization groundwater (TDS > 8000 mg/L). While the southern limb, characterized by high-angle tensile fractures and active groundwater runoff, suffers gas loss and generally low gas content (<3.5 m3/t). This study clarifies CBM enrichment laws and enrichment mechanisms, supporting exploration of low-rank CBM in the Hedong mining area.

1. Introduction

Against the backdrop of a low-carbon energy transition, the strategic importance of coalbed methane (CBM) as a clean energy resource is increasingly evident [1,2]. Its efficient development serves the dual purposes of safeguarding energy security and achieving China’s “dual-carbon” goals. Chinese CBM resources are characterized by basin-centered distribution, with the Junggar Basin representing a key strategic replacement area [3]. Results of the national oil and gas resource assessment during the 13th Five-Year Plan indicate that the geological CBM resource in the Junggar Basin totals 3.11 × 1012 m3, accounting for 11.07% of the national total [4]. Along the southern margin of the basin, the Hedong mining area in Urumqi features numerous and thick coal seams, demonstrating significant resource potential. Since 2017, over 100 CBM appraisal and production wells have been drilled in the mining area, achieving a production capacity of 0.5 × 108 m3/a. Initial gas production has been promising, confirming development feasibility. However, complex geological conditions have prevented a systematic characterization of CBM enrichment laws and controlling factors. To date, the mining area’s development remains in its early stages, highlighting the urgent need for deeper geological theory and exploration technology research.

Analysis of CBM enrichment laws and investigation of multi-factor synergistic control mechanisms are fundamental for overcoming theoretical barriers and achieving scientific development. International studies generally agree that CBM accumulation is jointly controlled by structural and hydrogeological conditions, coal reservoir properties, gas content, and metamorphic degree [5]. In the United States, CBM resources are concentrated in low-rank coal basins in the West; studies in the San Juan Basin indicate that synergistic effects of fault compression and groundwater entrapment create high-pressure gas accumulation zones [6]. In Australia, over 90% of CBM production originates from the Bowan and Surat foreland basins in the northeast, where CBM accumulation is governed by a coupling mechanism between imbricate structural stacking and a weak, flow-dominated hydrogeological system [7]. In Canada’s Alberta Basin, a mixed gas-source model has been proposed for low-rank CBM, dominated by biogenic gas with thermogenic gas supplementation; active microbial activity together with favorable paleotemperature conditions drive large-scale generation of secondary biogenic methane.

Since its inception in the 1980s, China’s CBM exploration and development industry has established a sector covering all coal ranks with distinctive regional characteristics by introducing international theories and pursuing independent technological breakthroughs [8]. CBM resources are developed across different coal ranks: in North China, high-rank Pennsylvanian–Permian CBM is exemplified by the Qinshui Basin and the eastern margin of the Ordos Basin, with the Qinshui Basin pioneering the country’s first 100-billion-cubic-meter-scale production base; exploration of high-rank CBM in southern Sichuan and northern Guizhou has also achieved new breakthroughs in recent years [9]. In Northwest China, Jurassic mid- to low-rank resources in basins such as Junggar and Turpan-Hami are representative, while in Northeast China, low-rank Cretaceous CBM has achieved commercial success in the Fuxin and Tiefa Basins, together forming potential zones for replacement development [10]. Vertical enrichment laws of CBM are prominent: at shallow burial depths, CBM is mainly enriched in syncline cores; in large fold structures, CBM tends to accumulate in limb slope zones; as burial depth increases further or in compressional stress environments, structural highs become favorable accumulation sites [11]. In deep coal seams, CBM occurrence changes—for example, in regions of the eastern Ordos Basin and western Guizhou where burial depth exceeds 2000 m, the proportion of free gas significantly increases. Currently, shallow CBM resources (burial depth < 1000 m) in China have become the main focus of development, owing to lower exploration costs and relatively easier exploitation [12].

CBM accumulation and preservation are jointly controlled by multiple factors including structural framework, hydrogeology, and reservoir properties. Regional structural evolution dictates the macroscopic distribution of CBM. stable structural units favor preservation, whereas active fault zones promote gas leakage. Structural geometry governs local accumulation and dispersion; syncline cores tend to form enrichment units due to sealing effects, while anticline cores, characterized by low-pressure environments, often experience gas escape. The in situ stress field influences fracture development and permeability distribution in coal reservoirs. Brittle deformation zones develop extensive fractures and exhibit high permeability, whereas ductile deformation zones act as low-permeability barriers [13]. Hydrogeological conditions affect CBM preservation and migration through variations in hydraulic regimes; quiescent-flow, stagnant-water environments create hydraulic seals, while active-flow zones compromise reservoirs via adsorption–dissolution–migration processes. In the southern Qinshui Basin, overpressured stagnant aquifers maintain the adsorption equilibrium of CBM, forming classic enrichment units, and field practices in the eastern Ordos Basin’s pressure-charged water zones further validate the coupling effect of structure and hydrogeology on gas control.

Gas genesis plays a key role in regulating the vertical distribution of CBM. In the Fukang mining area, CBM is supplemented by three sources: biogenic gas, thermogenic gas and deep-migrated gas [14]. Gas composition and isotopic indicators are traditional tools for origin identification: for example, δ13C (CH4) = −55‰ serves as the boundary between thermogenic and biogenic gas, and δD (CH4) values distinguish CO2-reduction biogenic gas (−250‰ to −150‰) from acetate-fermentation biogenic gas (−400‰ to −250‰) [15,16]. Milkov and Etiope, based on 20,000 global data sets, revised the genetic classification by defining microbial direct metabolic products as primary biogenic gas and alteration products derived from thermogenic gas as secondary biogenic gas, thereby providing a new framework for reservoir gas-genesis analysis [17].

The layout and development direction of CBM in Xinjiang highlight that elucidating the accumulation characteristics, enrichment laws, and primary controlling factors of southern Junggar Basin CBM is a critical theoretical foundation. Current research in the study area indicates that gas content varies across different structural positions and that CO2 concentrations in CBM are anomalously high [18]. Coal seams in the mining area generally exhibit steep dips and complex geological conditions due to multiple phases of structural movement. Although domestic and international studies provide valuable references for CBM exploration and development in this area, they do not fully align with its specific conditions, and research on CBM enrichment laws remains insufficient, particularly regarding comprehensive controlling mechanisms. To address these issues, this study investigates the horizontal and vertical distribution characteristics of CBM, integrates gas composition, stable isotope data, and the latest natural gas genetic identification diagrams to determine gas origins, and comprehensively analyzes the synergistic control of geological factors on CBM enrichment.

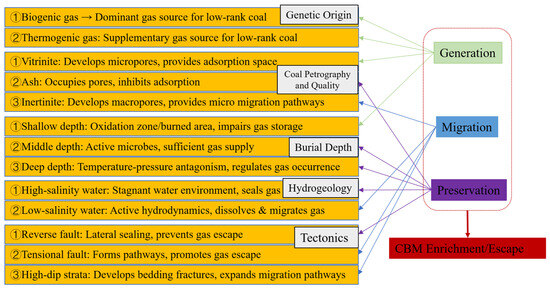

Given the complexity of this synergistic control, a conceptual framework diagram is specifically constructed as shown in Figure 1 to help readers better grasp the research logic of this study and lay a clear foundation for the subsequent in-depth analysis. The aim is to provide a reference for CBM research in the study area and in southern Junggar Basin at large, as well as to offer theoretical support for CBM exploration and development.

Figure 1.

CBM Enrichment Framework of Xishanyao Formation.

2. Geological Background

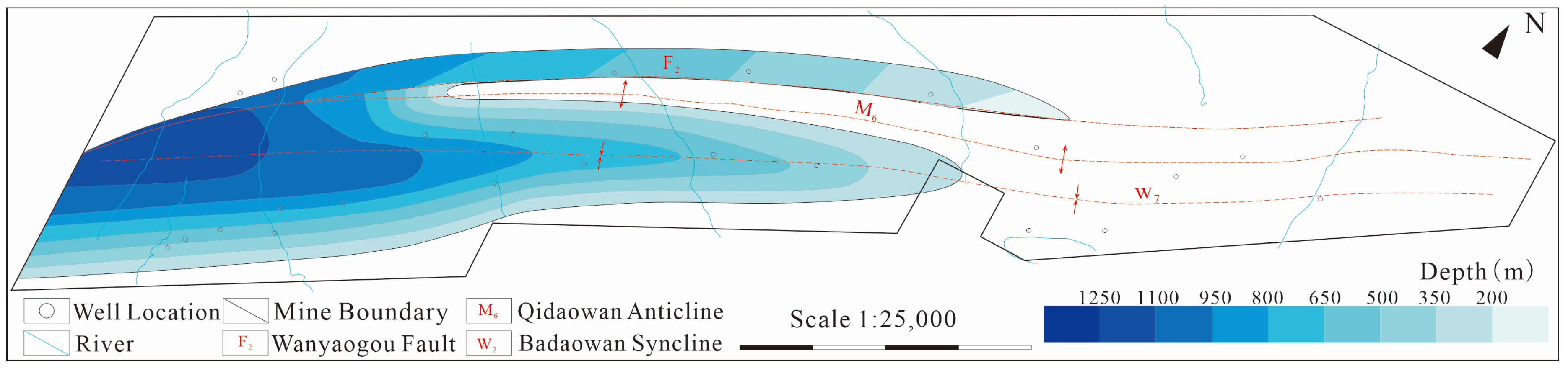

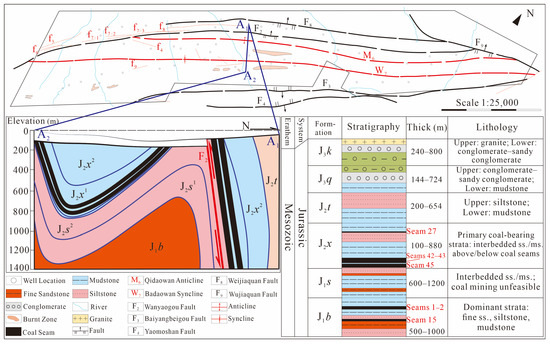

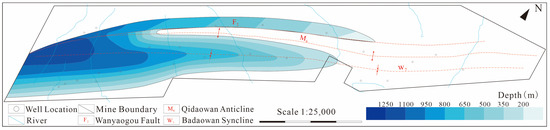

The study area is located on the northern margin of the Tianshan fold belt, within the Urumqi foreland depression. The Badaowan Syncline (W7) and Qidawan Anticline (M6) serve as the main structures, dividing the region into three structural units: the southern limb of the Badaowan Syncline, the northern limb of the Badaowan Syncline, and the northern monocline. Major faults include the Wanyaogou Fault (F2), Baiyang North Gully Fault (F3), Yaomoshan Reverse Fault (F4), and Weijiaquan Reverse Fault (F8), with numerous secondary faults (f) also developed (Figure 2) [19].

Figure 2.

Structural and stratigraphic framework of the study area [19].

The climate in the study area is arid, and atmospheric precipitation provides minimal groundwater recharge. The Urumqi River, Baiyang River, and other rivers—fed by snowmelt, storm runoff, and fracture springs—have incised the coal-bearing strata. Aquifers and aquitards are interbedded, and hydraulic connectivity between aquifers is weak. Spontaneous combustion of coal seams is common; burned zones are primarily distributed on the southern limb of the syncline between lines 21 and 25, at depths exceeding 100 m.

Coal-bearing strata, from bottom to top, consist of the Jurassic Badaowan Formation (J1b), Sangonghe Formation (J1s), and Xishanyao Formation (J2x). The Xishanyao Formation (J2x) is the primary coal-bearing unit, with a total coal seam thickness of 334.87–414.01 m (average 350.69 m), net coal thickness of 50.28–147.43 m (average 112.32 m), and a coal-bearing coefficient of 15.60%. There are 18–20 mineable coal seams (groups), with a total mineable thickness of 102.26–127.80 m (average 106.31 m). Among these, coal seams Nos. 42–43 and No. 45 are regionally distributed, which exhibit strong lateral continuity and stable thickness, and serve as the main gas-producing seams.

The study area’s unique structural framework, arid climate-driven hydrology, multilayered coal-bearing strata, and extensive burned zones collectively lays the geological foundation for CBM generation, occurrence, and enrichment, constraining coal quality evolution and pore structure of the Xishanyao Formation’s main seams and supporting subsequent analysis of CBM enrichment controlling factors.

3. Coal and Gas Characteristics

The data in this study are mainly derived from the test and analysis results of 32 CBM parameter wells and production wells. The sampling scope covers three core structural units: the southern wing, northern wing of Badaowan Syncline, and the northern monocline (Table A1). The wells are evenly arranged along Exploration Lines 1 to 41. Vertically, the samples cover Coal Seams 2 to 45 with a burial depth range of 269.65–1250.04 m, ensuring the representativeness of samples in terms of space and stratigraphic horizons. Among them, the planar distribution map of gas content is based on the main coal seams (Seams 42–43 and 45), which are widely distributed with sufficient samples and high data reliability. Information on other coal seams (Table 1, Figure 3 and Figure 4) is used to compare the differences among different coal seams, further highlighting the research value of the main coal seams.

Table 1.

Gas content and composition of coal seams in the study area.

3.1. Coal Rock and Coal Quality Characteristics

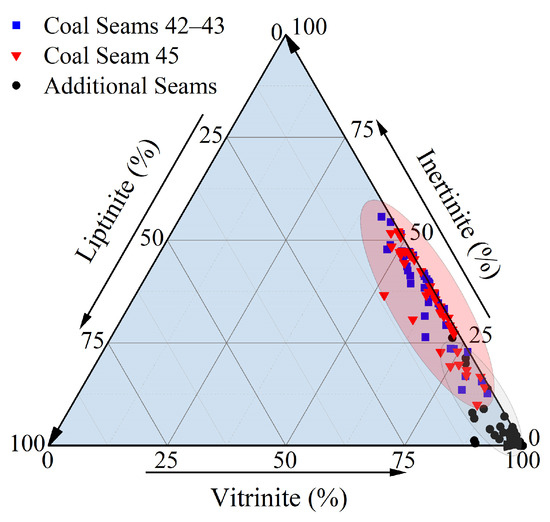

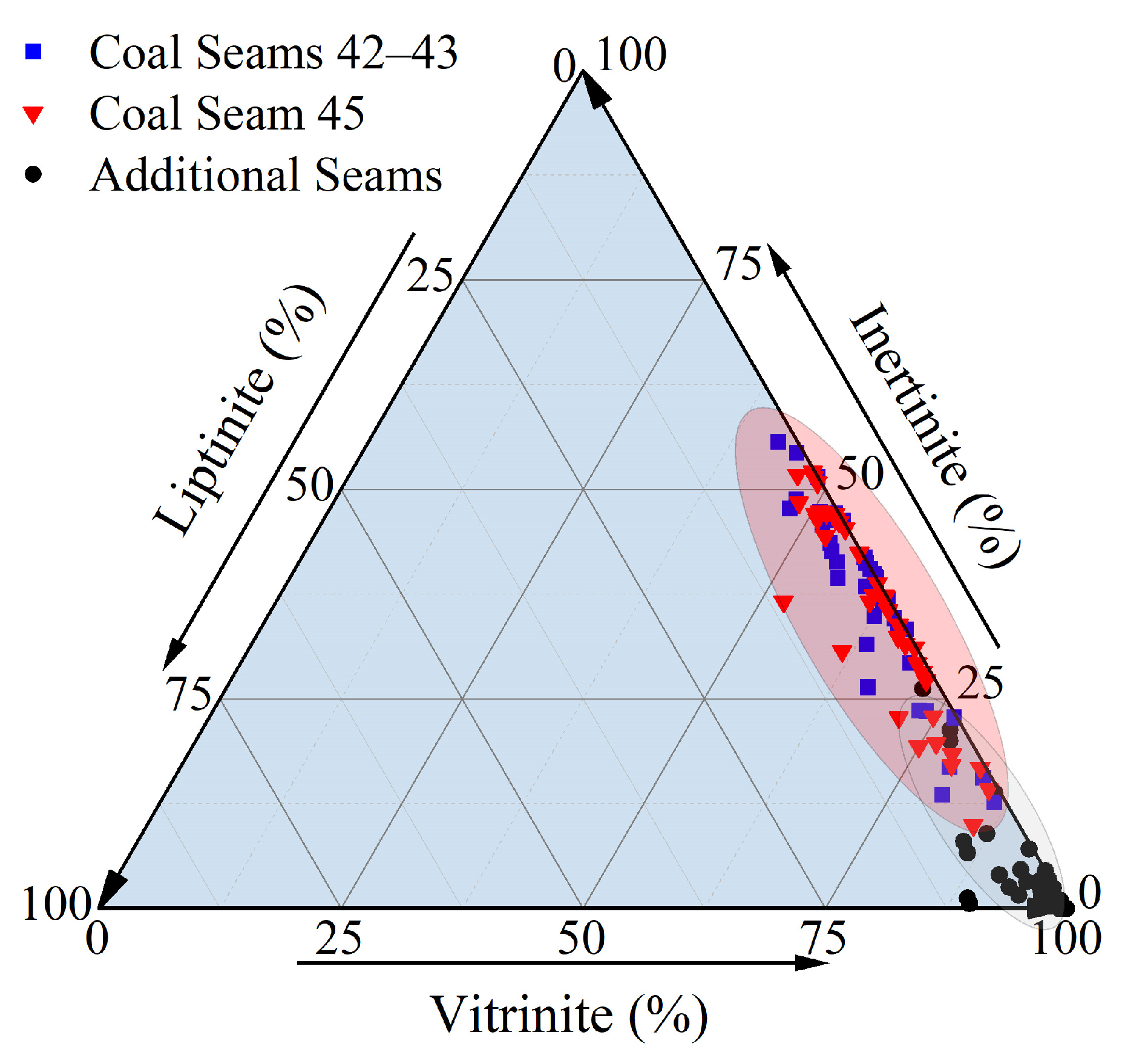

The coal samples from the study area have relatively intact seam structure, consisting mainly of primary structural coal with minor fragmented coal. The maximum vitrinite reflectance (RO,max) of coal samples ranges from 0.50% to 0.78%, which is in the middle and low metamorphic stage. The metamorphic degree not only adapts to the temperature and pressure conditions of biogas generation but also forms a certain adsorption pore space. The organic macerals in the coal account for 82.83–98.69% of the whole rock, of which vitrinite comprises 41.60–99.89% (average 70.30%). The high vitrinite content provides the core carrier for methane adsorption, and its rich microporous structure is the key space for coalbed methane reservoir. Inertinite content ranges from 0.39% to 55.36% (average 28.54%), and the low proportion of inertinite further improves the adsorption potential of coal reservoir. Liptinite content is generally low, ranging from 0.01% to 15.40% (average 1.16%), which has limited influence on coalbed methane enrichment (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Ternary diagram of maceral composition proportions in the study area.

Figure 3.

Ternary diagram of maceral composition proportions in the study area.

Based on inter-seam correlation, it is observed that Seams 42–43 and 45 exhibit significantly higher vitrinite content and noticeably lower inertinite content than those of other coal seams. Vitrinite typically forms under conditions of subaqueous reduction, whereas inertinite reflects a water-deficient, oxygen-rich environment. It is inferred that the environmental mutation in the coal-forming period of these two sets of coal seams may strengthen the coalification and finally shape its better reservoir adsorption conditions.

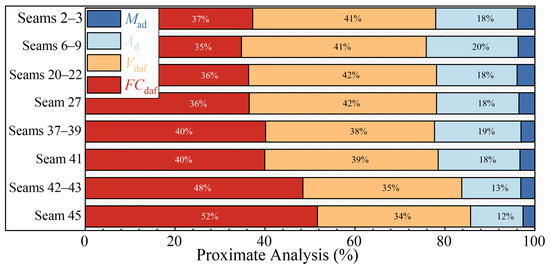

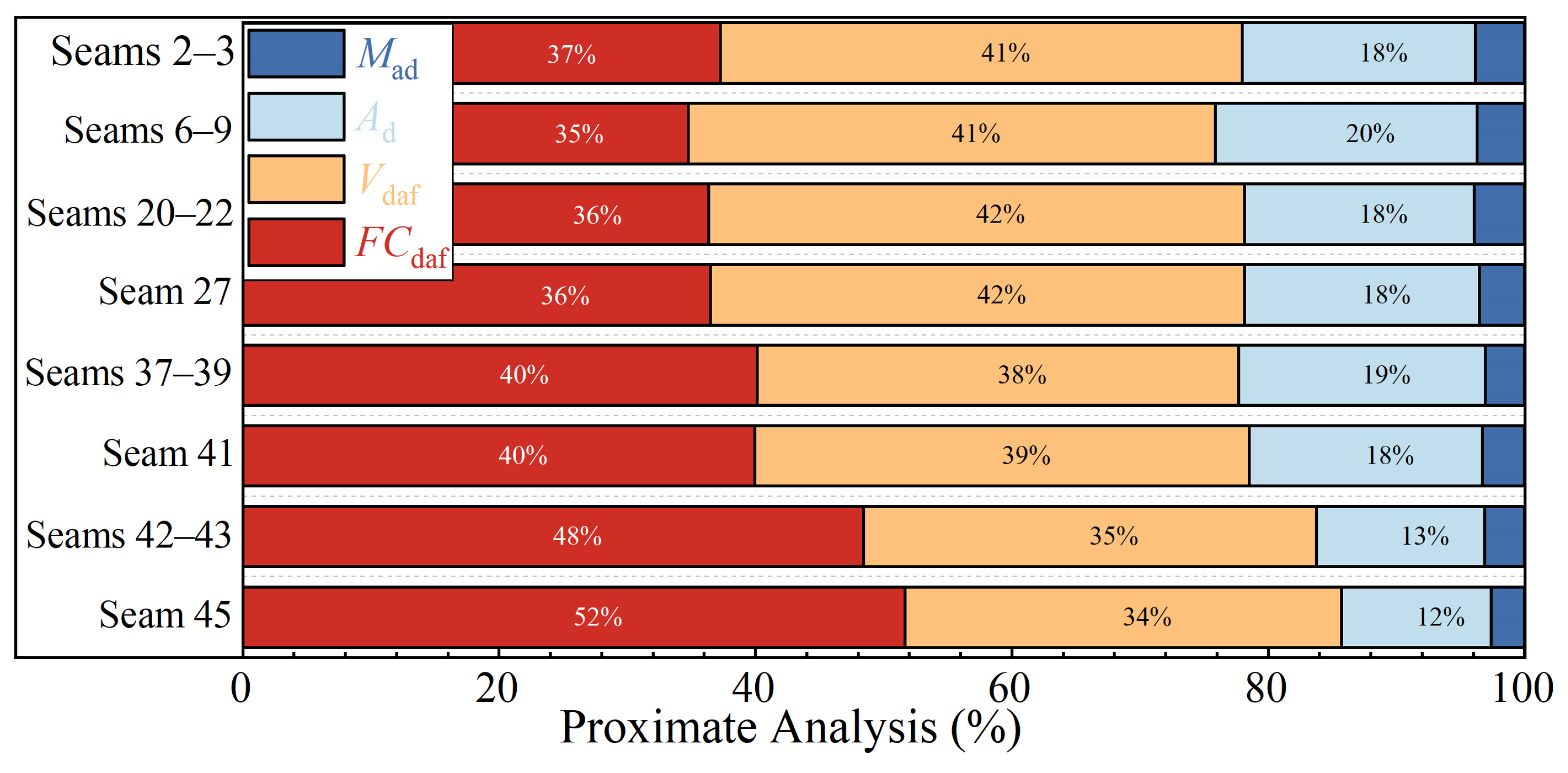

The moisture content of coal in various seams within the study area ranges from 0.42% to 6.80%, with an average of 2.45%, classifying it as ultra-low moisture coal. Low moisture reduces the occupation of adsorption sites and is conducive to methane preservation. The ash content ranges from 0.55% to 59.51%, with an average of 15.20%. Notably, Seams 42–43 and 45 have an average ash content of less than 13%, which reduces the blockage of pores by inorganic minerals and has better methane adsorption performance. The volatile matter content varies between 25.61% and 54.93%, with an average of 37.23%, placing it in the category of medium-high to high volatile coal. Fixed carbon content shows a wide fluctuation from 10.14% to 89.18%; with an average of 45.12%, it falls under the category of low fixed carbon coal.

Vertically, fixed carbon content increases with depth, whereas volatile matter and moisture content decrease slightly. This reflects higher metamorphic degree and stronger CH4 adsorption capacity of deeper coal seams. Thus, coal seams 42–43 and 45, with the comprehensive advantages of suitable metamorphic degree, high vitrinite content, and low ash content, represent favorable CBM generation and storage reservoirs (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Proximate analysis of major coal seams in the study area.

Figure 4.

Proximate analysis of major coal seams in the study area.

3.2. Gas-Bearing Feature

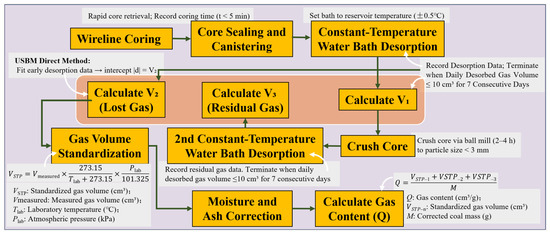

In this paper, the USBM direct method was adopted to determine the gas content of coal samples. The measurement equipment and sample preparation comply with the requirements of GB/T 19559-2021 [20]. During the measurement process, strict lost gas correction (with loss gas content estimated via the modified Smith-Williams formula), residual gas measurement, and temperature-pressure condition corrections were implemented. The specific measurement process is shown in Figure 5 [21].

Figure 5.

Gas content determination process diagram.

The results of gas content and gas composition show that the measured gas content of coal seams in the study area varies greatly, generally ranging from 0.01 to 16.31 m3/t, with an average of 5.32 m3/t. Methane (CH4) dominates the gas composition, with volume fractions ranging from 42.59% to 99.95%, averaging 79.12%. The volume fraction of CO2 typically ranges from 0.01% to 46.75%, averaging 15.11%, while N2 volume fractions range from 0.01% to 41.44%, averaging 5.64% (Table 1).

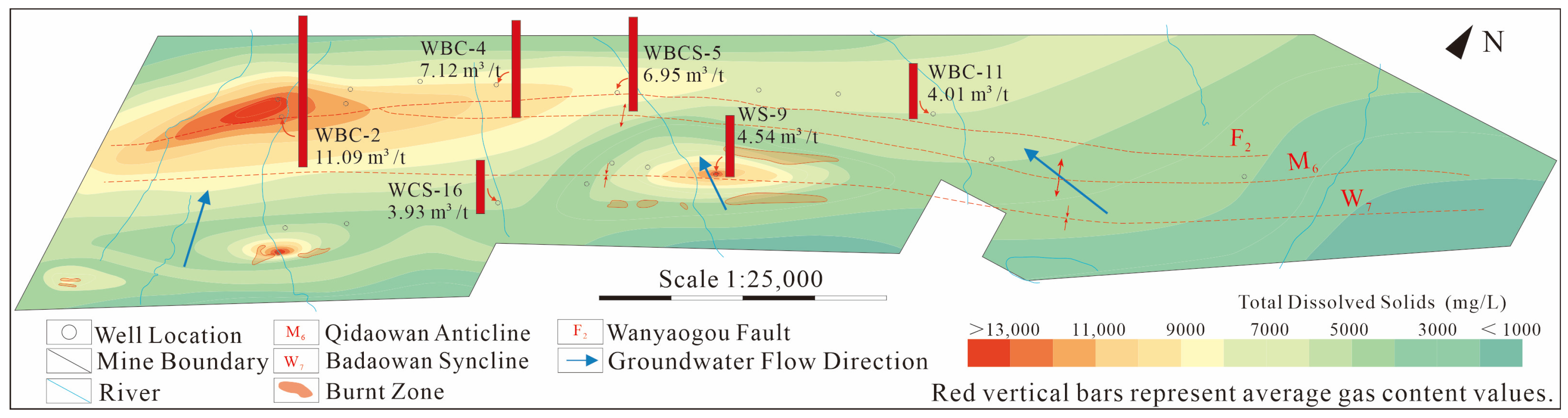

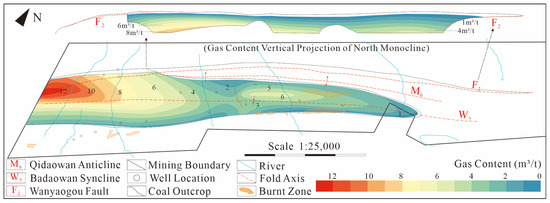

The gas-bearing coal seams in the study area are primarily distributed in the western region, controlled by the Badaowan syncline Qidaowan anticline, exhibiting strong vertical continuity and extensive planar distribution. In contrast, the eastern region has fewer coal seams with poor continuity. Using the distribution of major coal seams such as 42–43 and 45 as control boundaries, the gas content isopleths were drawn, revealing strong regularity. Planarly, the gas content in the study area is characterized higher values in the west and north, and lower values in the east and south (Figure 6). High gas content areas are concentrated in the northern limb of the syncline and the western side of the Wanyaogou fault. The northern monocline (the footwall of the Wanyaogou fault) generally exhibits higher gas content. Across different structural units, the gas content in the northern monocline typically ranges from 1.42 to 14.27 m3/t, with an average of 6.36 m3/t. The coal seams on the northern limb of the syncline are developed between 250 and 1200, resulting in a wide variation in gas content, generally from 1.25 to 16.31 m3/t, with an average of 6.01 m3/t. The limb of the syncline features uplifted strata with more surface-exposed coal seams, constrained by deeper weathering and oxidation zones and thermal disturbances from burned zones, leading to generally lower gas content, typically ranging from 0.50 to 5.20 m3/t, with an average of 3.50 m3/t.

Figure 6.

Contour map of gas content in coal seams in the study area.

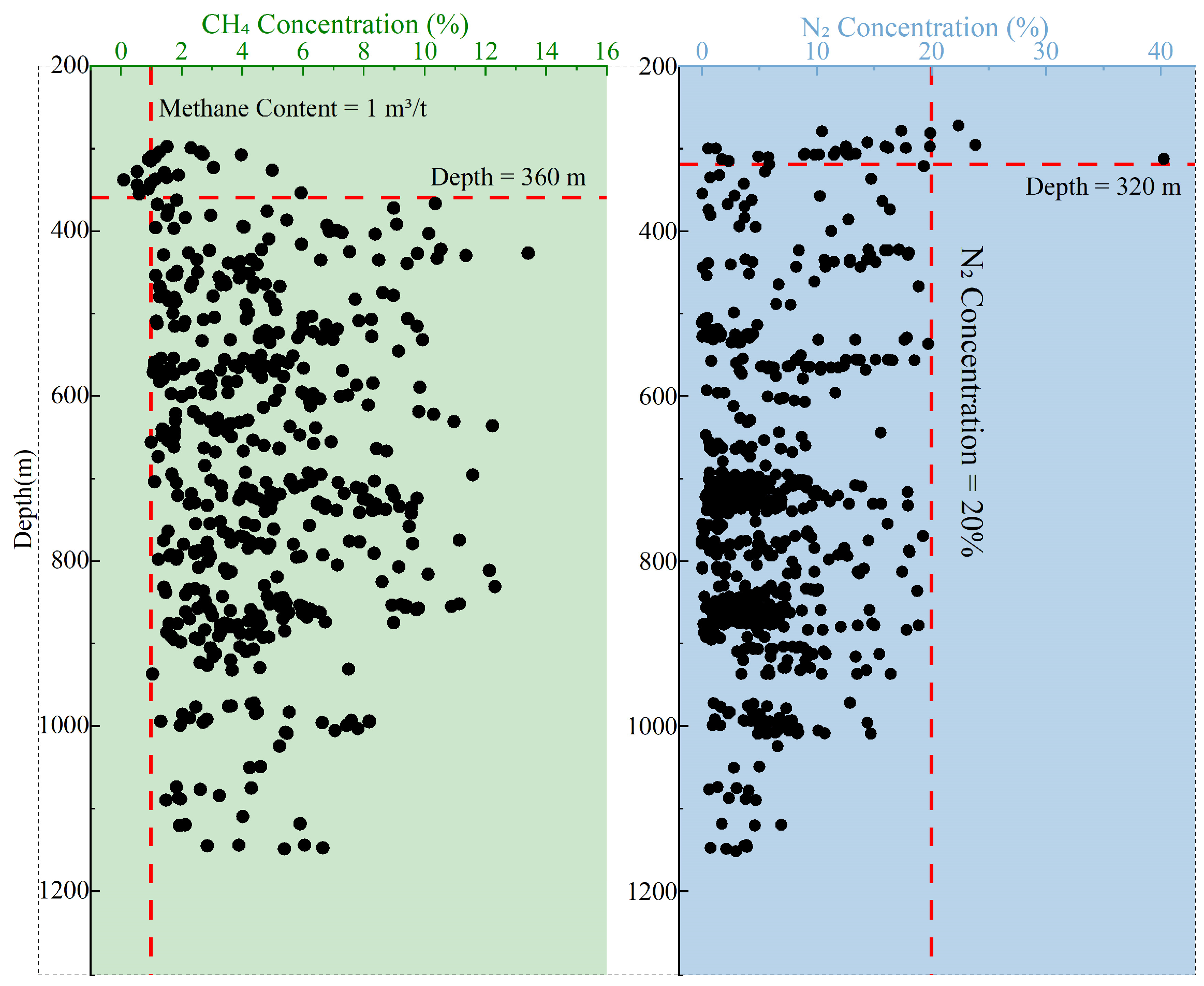

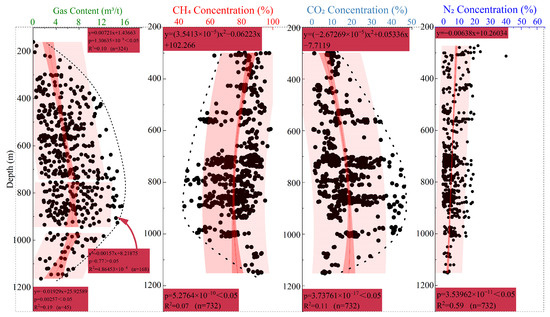

Vertically, the gas-content variation is relatively complex. Statistical analysis by dividing burial depth intervals shows the following: for coal seams shallower than 750 m, the gas contents ranging from 0.01 to 15.70 m3/t (average 5.25 m3/t), increasing rapidly with burial depth. Between 750 and 950 m, gas contents range from 0.24 to 16.31 m3/t (average 5.74 m3/t), remaining at relatively high levels, with many samples exceeding 12 m3/t. Below 950 m, gas content declines, ranging from 0.15 to 11.17 m3/t (average 5.08 m3/t). Overall, gas content first rises with increasing depth, then briefly maintains a peak, and finally decreases, indicating that burial depth is a critical factor affecting coal seam gas content (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Relationship between coal seam gas content/composition and burial depth in the study area.

Vertical variations in CBM composition also exhibit distinct trends. Fitting results show that CH4 concentration first decreases and then increases with burial depth. According to the lower-envelope trend, CH4 concentration drops rapidly above 750 m, averaging 78.63%; remains at its lowest level between 750 and 950 m, averaging 74.22%; and then rises sharply below 950 m, averaging 80.46%, with the inflection point coinciding with that of gas content. CO2 concentration varies in a pattern highly similar to that of gas content: it increases with depth, stabilizes at its maximum level, and then decreases rapidly. CH4 and CO2 concentrations exhibit an inverse relationship, dividing into three stages at 750 m and 950 m, with average CO2 concentrations of 15.04%, 18.29%, and 14.28% from shallow to deep, indicating competitive adsorption between the two gases. N2 concentration decreases with depth but remains relatively stable and at low levels overall; the average N2 concentrations for the three stages are 6.61%, 5.53%, and 4.95%, respectively. Relatively high N2 concentrations at shallower depths are attributed to reservoir damage during later gas accumulation and to active water–gas exchange with groundwater.

The distribution characteristics of coal seam gas content in the study area show significant heterogeneity, and the gas composition is characterized by abnormal enrichment of CO2 and obvious N2 intrusion in shallow seams. This feature is the result of comprehensive control by multiple factors such as burial depth, structure and hydrology.

4. Key Controlling Factors

The enrichment law of CBM results from the combined effects of internal reservoir properties and external geological conditions: intrinsic factors such as gas origin and coal petrology directly determine gas generation potential and adsorption capacity; the depth of the oxidation zone, burial depth, and thermobaric field jointly regulate vertical gas distribution; and hydrogeological conditions along with structural characteristics comprehensively control reservoir sealing versus gas escape.

4.1. Control of Genetic Types

When CO2 concentration exceeds 60%, CBM is considered to be of inorganic origin. In the study area, CO2 concentrations range from 0.58% to 45.06%, with an average of 15.03%, which is well below the inorganic gas threshold; thus, a mantle-derived inorganic origin can be excluded [17,22]. Based on the dryness coefficient (C1/∑C1–5), CBM can be classified as ultra-wet gas (<0.85), wet gas (0.85–0.95), dry gas (0.95–0.99), or ultra-dry gas (>0.99). In the study area, the dryness coefficient generally exceeds 0.95, indicating dry to ultra-dry gas characteristics. Although both biogenic and thermogenic gases exhibit dry-gas signatures, coal-rock RO,max values in the region range from 0.50% to 0.78%, averaging approximately 0.65%, indicating a relatively low maturity. Since thermogenic gas generation typically requires RO,max values greater than 2.0%, the preliminary analysis indicates that CBM in the study area is organic in origin, dominated by biogenic gas.

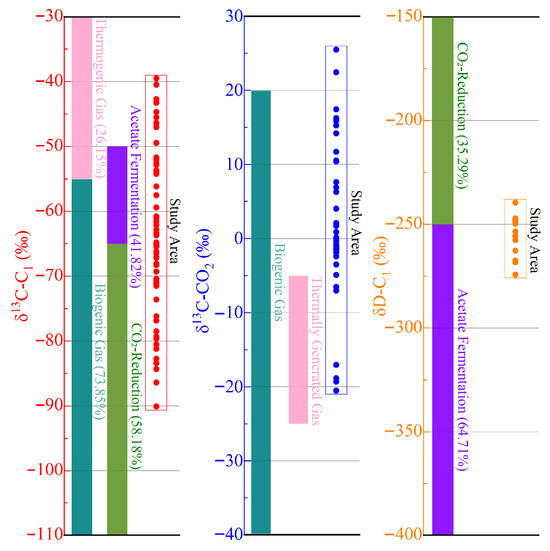

The δ13C-C2 values in the study area range from −28.56‰ to −17.17‰, with an average of −23.43‰. Values greater than −28.00‰ indicate coal-derived gas, suggesting a high proportion of coal-type gas [23]. Analysis of δ13C-C1 (−90.1‰ to −39.5‰, average −63.86‰) and δ13C-CO2 (−20.50‰ to 25.47‰, average 2.09‰) reveals the presence of thermogenic gas, although biogenic gas predominates at 73.85% (Figure 8). Additionally, δ13C-C1 and δD-C1 values (−274.29‰ to −239.55‰, average −257.01‰) indicate that both CO2 reduction (CO2 + 4H2 → CH4 + 2H2O) and acetate fermentation (CH3COOH → CH4 + CO2) pathways exist for biogenic gas generation. According to δ13C-C1, CO2-reduction gas accounts for 58.18% of biogenic gas, while acetate-fermentation gas accounts for 41.82%; however, δD-C1 indicates the opposite, with acetate fermentation comprising 64.71% and CO2 reduction 35.29%. The core cause of the inconsistency between the two isotopic indicators lies in differences in material sources and fractionation intensities: the hydrogen source of δD-C1 depends on coal seam water, so its identification results are significantly disturbed by hydrogeochemical conditions—microorganisms preferentially use light hydrogen (1H) during biogenic gas generation, leading to 2H depletion in methane and lighter δD-C1 values, which cause more samples to fall into the acetate-fermentation pathway range (>−250‰); In contrast, δ13C-C1 has coal-measure organic matter as its parent material, with stronger parent material inheritance and less interference from hydrogeology. Under the background of complex hydrogeology in the study area, it is more suitable as an identification indicator; thus, the conclusion that the CO2-reduction pathway is dominant (58.18%) derived from δ13C-C1 is closer to the actual situation.

Figure 8.

Distribution of stable gas isotopes in the study area.

Overall, CBM in the study area exists as a mixed gas dominated by biogenic origins, with a minor thermogenic contribution.

In isotopic determinations of gas origin, overlapping boundaries or contradictory results can occur. For example, δ13C-C1 = −55‰ is often used to distinguish thermogenic from biogenic gas, whereas the upper limit for acetate-fermentation-derived biogenic gas is −50‰. Additionally, when subdividing biogenic gas types using δ13C-C1 and δD-C1, the results may be inconsistent. This is not only potentially related to the number of isotopic samples, but more crucially reflects the limitations of a single method—exemplified by the preliminary 26.15% thermogenic gas proportion from single-isotope classification, which cannot accurately reflect the true origin due to the subjectivity of previous classification standards and overlapping/contradictory defined ranges. Therefore, detailed classification of gas origins in the study area requires further confirmation by integrating genetic identification diagrams.

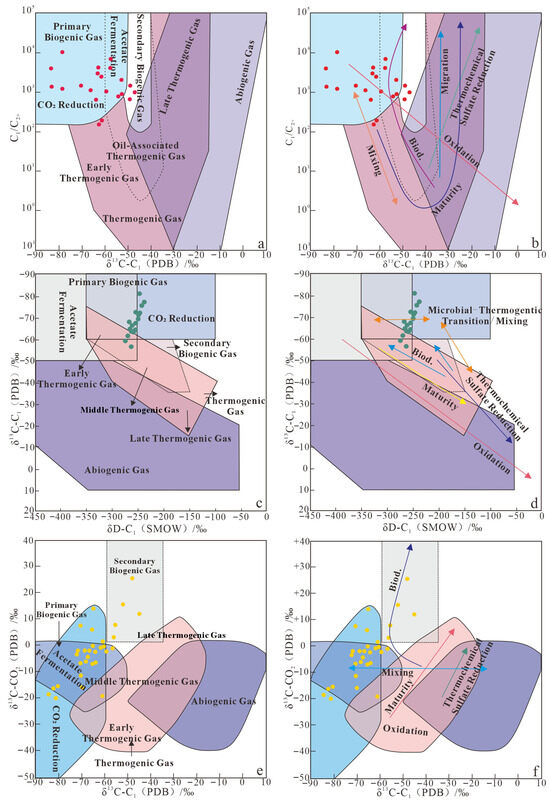

Milkov and Etiope (2018) [17] proposed an updated natural gas genetic identification diagram that classifies gas generated directly from organic matter via CO2 reduction or acetate fermentation as primary biogenic gas, and gas produced by anaerobic microbial alteration of thermogenic or other non-biogenic gases as secondary biogenic gas; thermogenic gas is further subdivided into early, oil-associated, and late stages. In this study, three genetic identification diagrams are employed in combination to analyze CBM origin types in the study area [17].

Using the δ13C-C1 versus C1/C2+ diagram (Figure 9a), biogenic gas accounts for 90.48% (19 of 21) of all gas samples in the study area, among which primary biogenic gas accounts for 76.19% (16 of 21)—10 of these indicate CO2 reduction and 6 indicate acetate fermentation—while 3 samples (14.29%) fall in the secondary biogenic gas field and early thermogenic gas accounts for only 9.52% (2 of 21, at depths of 1046.00 m and 1159.00 m). As shown in Figure 9b, early thermogenic gas and primary biogenic gas coexist in a mixed system, suggesting that the study area has not yet entered a stage of extensive thermogenic gas generation and that early thermogenic gas has been partially altered by microbial activity to form secondary biogenic gas. By applying the δ13C-C1 versus δD-C1 diagram (Figure 9c) to further identify CBM origin and biogenic gas generation pathways, 3 samples occupy the overlapping zone of primary biogenic, secondary biogenic, and thermogenic gas. When counting, samples that exhibit multiple genetic characteristics are included in the statistics of their corresponding genetic types. Therefore, biogenic gas accounts for 86.96% (20 of 23), among which primary biogenic gas accounts for 73.91% (17 of 23), and both secondary biogenic gas and early thermogenic gas account for 13.04% (3 of 23), which is largely consistent with the δ13C-C1 versus C1/C2+ results. Figure 9d shows that CBM in the study area exhibits a mixed signature of biogenic gas and microbially altered thermogenic gas. Finally, using the δ13C-C1 versus δ13C-CO2 diagram (Figure 9e) to distinguish primary biogenic, secondary biogenic, and high–maturity thermogenic gas, 1 sample falls in the overlap between primary biogenic and early thermogenic gas. After counting this sample into its corresponding genetic types, respectively, biogenic gas accounts for 96.88% (31 of 32), among which primary biogenic gas accounts for 81.25% (26 of 32), secondary biogenic gas accounts for 15.63% (5 of 32), and only 3.12% (1 of 32) indicates early thermogenic gas.

Figure 9.

(a) δ13C-C1 versus C1/C2+ genetic identification diagram and (b) related geological influence processes; (c) δ13C-C1 versus δD-C1 genetic identification diagram and (d) related geological influence processes; (e) δ13C-C1 versus δ13C-CO2 genetic identification diagram and (f) related geological influence processes [17].

After verification with multiple indicators, the actual proportion of thermogenic gas is much lower than 26.15%. Despite minor discrepancies in gas contribution rates identified by different methods, the results fully support the conclusion that CBM in the study area is of mixed origin, dominated by biogenic gas with a small amount of early thermogenic gas. It should be noted that “early thermogenic gas” is a classification method from the Milkov–Etiope diagrams (classified into early, middle, and late stages based on thermal evolution). Previous studies have classified thermogenic gas into thermocatalytic gas and thermal cracking gas by formation mechanism. As clearly stated earlier, only thermocatalytic gas (not thermal cracking gas) is generated in the study area. Therefore, these two terms (early thermogenic gas and thermocatalytic gas) refer to the same gas source in this manuscript.

Integrating CBM composition and stable isotope characteristics with the Milkov–Etiope identification diagrams indicates that gas in the study area is mainly of biogenic origin, with a minor early thermogenic component. Within the biogenic gas fraction, primary biogenic gas predominates; subsequent microbial alteration of thermogenic gas generates a small amount of secondary biogenic gas. Primary biogenic gas is produced via both CO2 reduction and acetate fermentation pathways. This understanding suggests that focus should be placed on areas with both biogenic gas generation potential and early gas preservation conditions. Such areas are more likely to form high-gas enrichment zones, providing a targeted prospecting direction for CBM exploration in the study area.

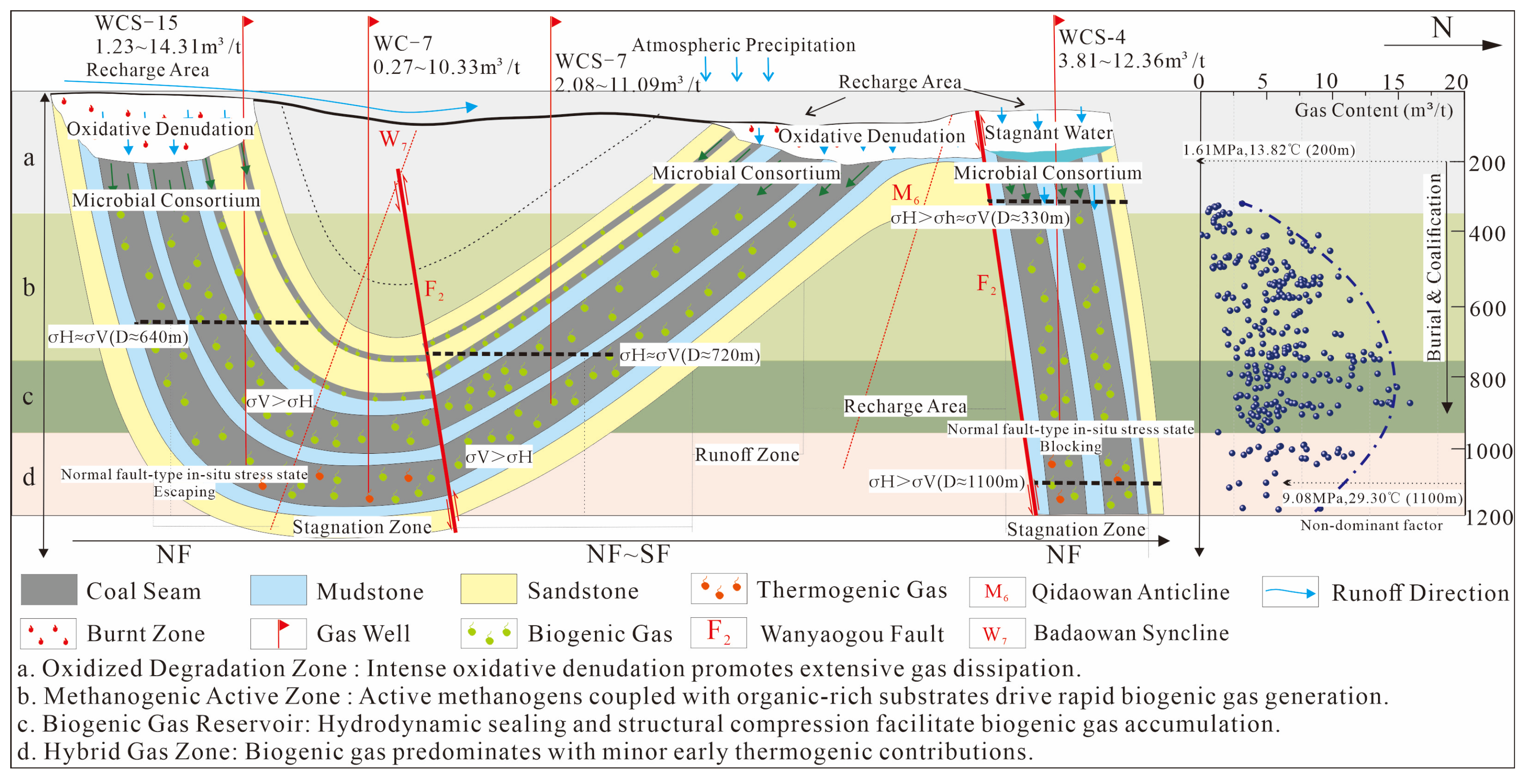

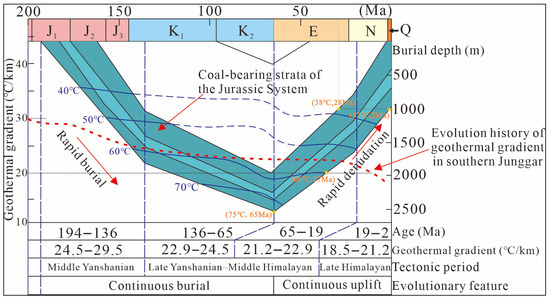

Gas origin types can reflect the coal-forming environment or coalification stage and, by influencing gas supply intensity and preservation conditions, jointly control the spatial distribution of CBM. In the study area, CBM exhibits a mixed signature of abundant biogenic gas and a minor thermogenic component, a pattern closely related to the regional burial history with significant spatial differences—unlike the high-temperature areas in the eastern and central parts of the Junggar Basin, the southern margin (study area) is the region with the lowest geothermal temperature in the basin (Figure 10) [24].

Figure 10.

Key Burial History Map of Jurassic Coal-Bearing Strata in Southern Junggar Target Area [25,26].

In the Late Cretaceous (ca. 65 Ma), Jurassic coal seams in the southern Junggar Basin area reached a maximum burial depth of approximately 2500 m, with reservoir temperatures of about 75 °C (temperature range: 60–75 °C) [25,26]. This temperature condition falls within the temperature window of “bio-thermocatalytic transitional zone gas” and corresponds to a vitrinite reflectance (RO) range of 0.5–0.78%. During this period, the immature to low-maturity thermogenic gas identified in the study area was essentially such transitional zone gas, formed by decarboxylation and dealkylation of organic matter under the catalysis of clay minerals and the mechanochemical effect of tectonic stress [27]. However, owing to the relatively low coal rank (RO < 0.8%) and the relatively tight deep reservoir conditions, the efficiency of thermogenic gas generation was poor, and the volume of generated gas was limited. After the initiation of the Himalayan movement at the end of the Cretaceous (ca. 65 Ma), the study area entered a continuous uplift stage; by approximately 37 Ma, the coal seam temperature dropped below 60 °C (the lower limit of the thermal degradation window), and the thermogenic gas generation process terminated. During the late Himalayan period (ca. 28–2 Ma), the strata were rapidly uplifted to depths shallower than 1000 m, and the temperature dropped below 38 °C.

With the shallow burial environment formed, the coalbed water in the study area (age: 43.5–2000 ka) recorded the evolutionary process of fluid activity: in the early Quaternary, atmospheric precipitation and shallow groundwater recharged the coal seams through fractures, forming a low mineralization freshwater environment and carrying methanogenic bacteria into the coal seams [28]. Relying on the favorable conditions of abundant organic matter (TOC > 45%) and weakly alkaline formation water (pH 7.2–8.0), methanogenic bacteria produced biogenic gas on a large scale. In addition, microbial communities degraded and transformed residual early thermogenic gas into secondary biogenic gas. With the gradual shift in the Quaternary climate toward aridification, the recharge of atmospheric precipitation decreased significantly, the circulation and exchange capacity of coalbed water weakened, and intense evaporation led to continuous increase in water mineralization—and when TDS exceeded 4000 mg/L, methanogenic activity became relatively low. This stagnant high mineralization water environment limited microbial gas generation while sealing the previously formed gas. Consequently, the preservation of both residual thermogenic gas and later-generated biogenic gas occurred in advantaged settings—such as high-stress zones and water-retention areas—resulting in the present complex multi-origin gas characteristics [29].

The pronounced biogenic signature of CBM in the study area explains why coal seam gas content increases with burial depth until approximately 950 m, then decreases. Biogenic gas is generated via two pathways: acetate fermentation, which produces CO2 as a byproduct accompanying CH4 generation; and CO2 reduction, which consumes CO2 but incorporates four hydrogen atoms from formation water into CH4. These processes require that surface runoff and groundwater deliver microbial communities and CO2 into the coal seams. Consequently, coal seam CO2 concentrations are anomalously high—often exceeding 40% and averaging 15.11%—demonstrating CO2’s contribution to biogenic gas [15]. Fitting of CO2 concentration versus depth shows a rapid increase above 750 m, persistence at high levels between 750 and 950 m, and a subsequent decrease below 950 m. This trend closely mirrors the gas content profile with depth, indicating that CO2 concentration, as a key component of biogenic gas, substantially supplements total gas content above 950 m. Microbial gas generation is controlled by hydrogeological characteristics. Currently, the mineralization of coalbed water shows a characteristic of increasing with increasing burial depth. Therefore, during the microbe-dominated gas generation period, a stagnant high mineralization water environment is formed earlier in the deep part, which inhibits the activity of methanogenic bacteria. Meanwhile, the thermogenic gas generation capacity is limited, leading to a subsequent decrease in coal seam gas content. In addition, the decrease in gas content at depths greater than 950 m may be related to temperature, pressure, or fractures developed in deep-seated structures.

4.2. Effects of Coal Petrology and Quality

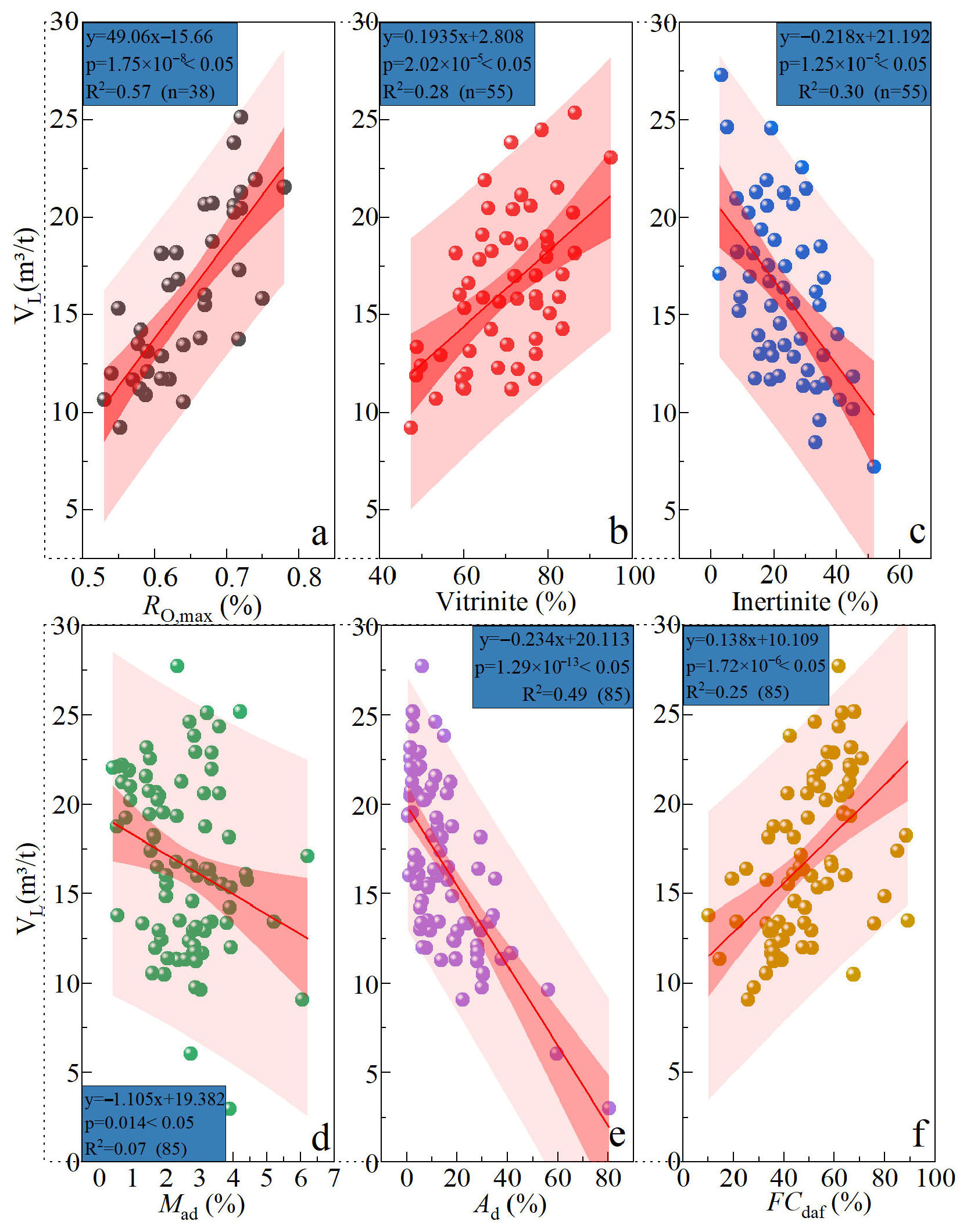

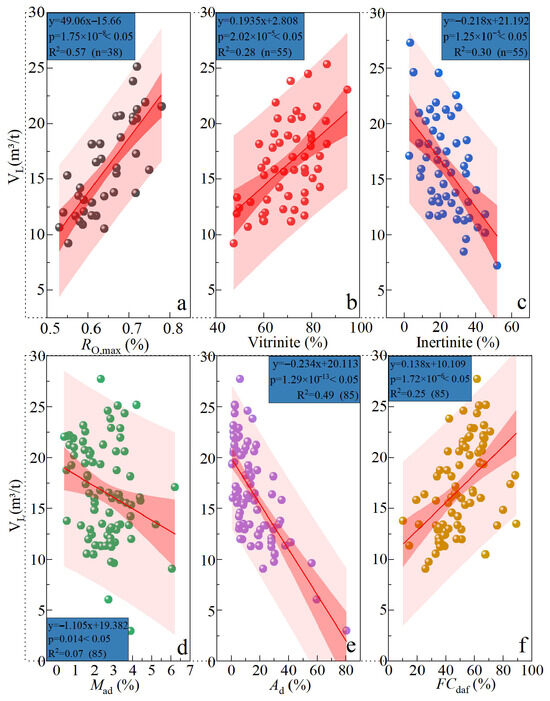

Measured gas content provides a direct indication of CBM occurrence; however, its correlation with any single factor is often weak due to the combined influences of coal adsorption capacity and subsequent preservation conditions. Langmuir volume directly reflects a coal’s adsorption potential, and coal petrology serves as the material foundation for CBM adsorption capacity, exerting a strong control over Langmuir volume.

Coal rank is a key factor influencing methane adsorption capacity. In the study area, coal RO,max values range from 0.50% to 0.78%, showing a monotonic increase in Langmuir volume with increasing reflectance; when RO,max is below 0.6%, Langmuir volume remains below 15 m3/t, but above 0.6%, it rises sharply, exceeding 25 m3/t (Figure 11a). For medium- to low-rank coals, higher coalification enhances both hydrocarbon generation and adsorption capacity, leading to increased gas content. However, the overall low coal rank in the study area limits adsorption capacity relative to high-rank coals, resulting in lower gas contents.

Figure 11.

Relationships between coal adsorption capacity and (a) vitrinite reflectance, (b) vitrinite content, (c) inertinite content, (d) moisture, (e) ash, and (f) fixed carbon in the study area.

Vitrinite is the dominant organic-rich component in coal and the core component for enhancing methane adsorption capacity. During its thermal evolution, it develops a large number of micropores (pore size < 2 nm) and mesopores (2–50 nm), which provide sufficient space for methane adsorption; in addition, numerous micropores and small pores form a multi-level pore-throat network, increasing the pore specific surface area and total pore volume. The higher the vitrinite content, the more adsorption sites are provided for coalbed methane occurrence, resulting in a stronger gas adsorption capacity (Figure 11b). Data fitting shows that vitrinite content has a positive correlation with Langmuir volume (R2 = 0.76): when vitrinite content increases from 55% to 80%, the Langmuir volume increases from 13.45 m3/t to 18.29 m3/t, which directly reflects the positive regulatory effect of vitrinite.

Inertinite develops more macropores (pore size > 50 nm) and some mesopores. Although it participates in gas adsorption by coal, gas in coal is preferentially adsorbed in smaller pores. Moreover, the inertinite content in the study area is significantly lower than that of vitrinite, so the methane adsorption effect of inertinite is weak; inertinite, due to its developed macropores, is more conducive to the diffusion and seepage of methane in coal. The average inertinite content in the study area is 18.7%, and its content is negatively correlated with Langmuir volume: when inertinite content increases from 10% to 40%, the Langmuir volume decreases from 19.01 m3/t to 12.47 m3/t (Figure 11c).

Moisture content is negatively correlated with Langmuir volume (Figure 11d). Liquid water fills pore spaces, reducing accessible adsorption sites; water molecules also compete with gas molecules for surface sites on the coal matrix and bind more strongly, further displacing methane. Additionally, moisture reduces permeability, hindering gas transport and re-adsorption.

Ash content in the study area shows a significant negative correlation with Langmuir volume (Figure 11e). Ash is mainly composed of inorganic substances like clay minerals, quartz, and calcite; its surface lacks organic functional groups, cannot provide effective adsorption sites, and thus has no methane adsorption activity itself. It inhibits methane adsorption mainly by filling pores in the coal matrix to directly reduce effective space and lowering organic matter proportion in coal to indirectly decrease adsorption sites. Additionally, charge repulsion exists between some charged minerals (e.g., iron oxides) and methane, further weakening adsorption potential. Fitting results show that when ash content is <10%, Langmuir volume generally exceeds 17 m3/t; when >35%, it drops below 12 m3/t.

Fixed carbon is positively correlated with Langmuir volume (Figure 11f). As the main organic component, higher fixed carbon content increases the proportion of organic matter available for methane adsorption, thereby raising Langmuir volume. The hydrophobic carbon matrix reduces the adverse effects of moisture on methane adsorption, and its ordered layered structure enhances adsorption strength through van der Waals interactions.

4.3. Impact of Burial Depth

Coal seam enrichment is governed by multiple depth-dependent factors. Burial depth suppresses CH4 escape through pressure-sealing effects; the depth of the oxidative weathering zone guides vertical zonation of shallow-seated seams; and the thermobaric field acts synergistically, with low-temperature domains (<30 °C) sustaining biogenic gas generation while pressure controls adsorption–desorption equilibrium. Together, these factors dictate the vertical differentiation of CBM in the study area.

Taking Seams 42–43 as an example, strata in the northwest have subsided, with the depression center located at the syncline core, resulting in greater burial depths. To the south and east, strata gradually uplift, causing shallower burial and even surface exposure. Thus, burial depth is significantly greater in the west than in the east and increases from south to north—trends that mirror the planar distribution of gas content (Figure 12). Vertically, at depths shallower than 950 m, gas content increases continuously with depth. This is because increased overburden thickness stabilizes the structural environment, effectively shielding the reservoir from surface weathering, oxidation, and hydrodynamic disturbances. Greater burial depth also lengthens diffusion pathways and increases migration resistance, enhancing gas preservation. Below 950 m, gas content declines. It is analyzed that coal seams within this interval are situated below the neutral surface of the syncline axis, where a tensile stress regime prevails and shear fractures are developed, leading to enhanced gas escape. Furthermore, the weakening of microbial gas generation intensity, resulting in insufficient gas supply to the deep coal seams, is also one of the reasons for the slight decrease in gas content.

Figure 12.

Planar distribution of burial depth for Seams 42–43.

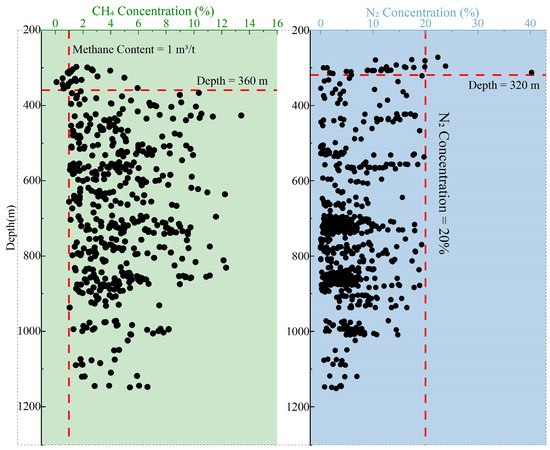

Shallow seams are severely depleted by uplift-induced exposure, oxidation, and hydrodynamic activity; within 300 m of the surface, measured gas contents are mostly below 1 m3/t, and seams shallower than 200 m contain virtually no CH4. Therefore, accurately defining the oxidative weathering zone is essential for CBM exploration and development. According to GB/T 5751-2009 [30], the oxidative weathering depth is defined by CH4 volume fractions < 80% and long-flame coal CH4 contents < 1 m3/t. In the study area, CH4 concentrations range from 42.59% to 99.95%, averaging 79.12%; moreover, elevated CO2 from burned zones and biogenic inputs causes many seams to fall below 80% CH4, rendering this method unsuitable and risking exclusion of valuable reservoirs.

Generally, near-surface zones receive atmospheric N2, so N2 concentration decreases with depth. In the study area, N2 follows this trend, leading to a revised criterion for the oxidative weathering zone: N2 > 20% and CH4 < 1.0 m3/t [31]. CH4 content consistently exceeds 1.0 m3/t below 360 m, and N2 remains below 20% below 320 m. Applying a “conservative maximum” principle from the CBM Resource Evaluation Standard, the oxidative weathering depth is determined to be 360 m (Figure 13). A deep weathering zone and extensive burned zones on the syncline’s southern limb cause near-surface seams to be heavily damaged, facilitating fracture-mediated gas escape and lowering reservoir gas content.

Figure 13.

Variation of CH4 content and N2 with burial depth in the study area.

Beyond the aforementioned effects, the three mechanisms of methane oxidation, desorption and escape, and N2 dilution in the oxidative weathering zone are superimposed with the organic matter consumption and permeability enhancement caused by burned zones along lines 21–25 on the southern limb of the syncline. Meanwhile, water-gas exchange between surface water and shallow groundwater further consumes and carries away CBM, collectively leading to the extremely low shallow CBM content in the study area.

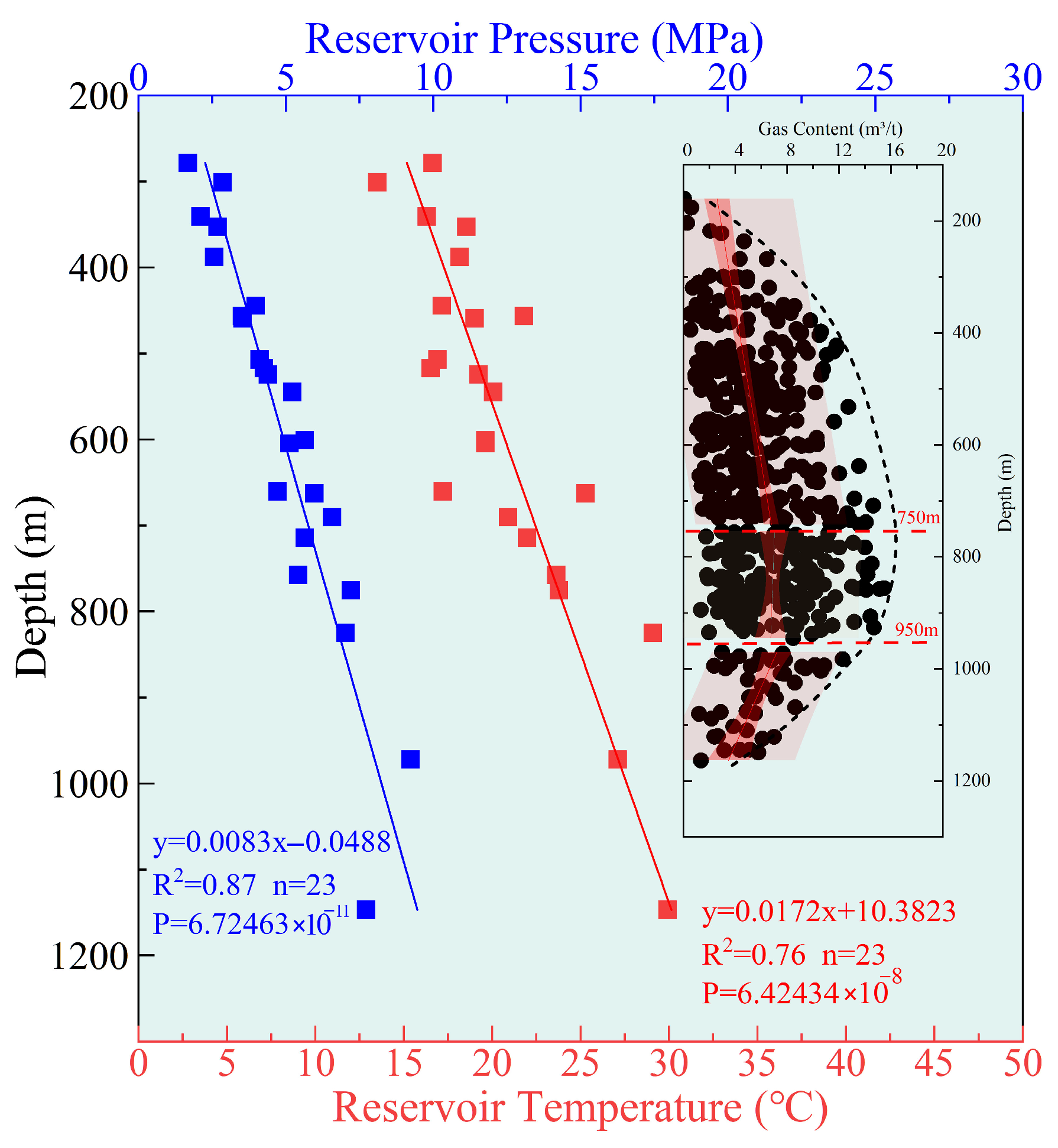

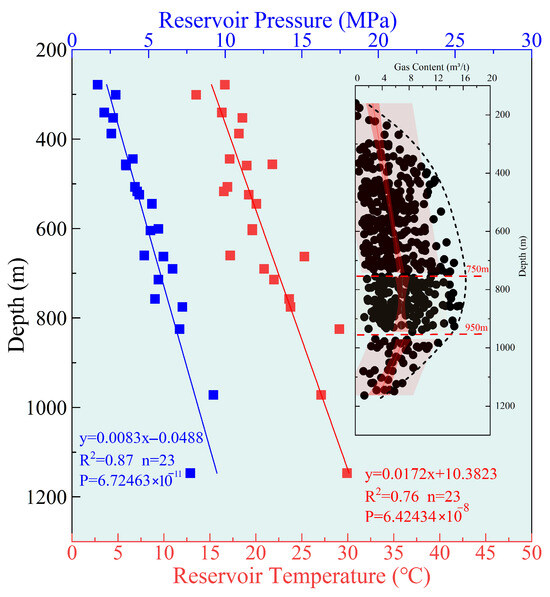

Burial depth directly influences reservoir pressure and temperature, and their combined effects govern methane adsorption in coal seams. Well test data show that, within the 200–1200 m depth range, reservoir pressure increases linearly with depth, ranging from 1.67 to 9.22 MPa (average < 5 MPa), classifying these as underpressured reservoirs. The pressure gradient varies between 0.60 and 0.96 MPa/100 m (average 0.83 MPa/100 m), indicating predominantly low- to normal-pressure conditions with some overpressure (Figure 14). Planar maps reveal reservoir pressure increasing toward the northwest depression center, mirroring the CBM distribution pattern. Within the same depth interval, reservoir temperature rises from 13.49 to 29.91 °C (average 20.51 °C), with a geothermal gradient of 0.84–7.14 °C/100 m (average 2.34 °C/100 m). Above 600 m, the gradient exhibits greater variability, likely due to disturbance from burned zones.

Figure 14.

Relationships among reservoir pressure, temperature, burial depth, and gas content in the study area.

Pressure exerts a positive effect on methane adsorption, whereas temperature has a negative effect [32]. Overall, structural uplift in the study area has led to insufficient reservoir pressure and low gas-saturation levels, resulting in an average gas content below 6 m3/t. Vertically, at depths shallower than 750 m, both reservoir pressure and gas content increase with depth, demonstrating the strong positive influence of pressure on CH4 adsorption. Below 750 m, although pressure continues to rise, gas content plateaus or declines, indicating that at greater depths other factors—such as rising temperature or reduced biogenic-gas supply—become more influential.

Regarding temperature, although higher temperatures can inhibit CH4 adsorption, reservoir temperatures shallower than 1200 m remain relatively low—for example, at 1146 m depth the temperature is only 29.91 °C—so the inhibitory effect on gas content is minimal. Furthermore, these seams lie above the critical depth for thermal domination and thus still fall within the “biogenic-active” zone. At depths shallower than 950 m, conditions are favorable for methanogenic bacteria, providing significant biogenic-gas supply and markedly enhancing gas content in shallow seams. Therefore, temperature’s negative effect on adsorption does not primarily drive the gas-content decline between 950 and 1200 m; rather, the low-temperature environment is beneficial for shallow biogenic-gas enrichment.

4.4. Hydrogeological Controls

Hydrogeological processes control CBM generation and preservation through dual mechanisms: hydraulic sealing and microbial activity constraint. The sealing effect is reflected in the fact that high mineralization indicates a weak runoff-stagnant state of groundwater and a closed-semi-closed hydrogeological system. Due to the recharge volume being much smaller than the evaporation volume and extremely slow flow rates, a natural hydraulic barrier is formed, which can effectively block the lateral migration and vertical escape of methane. Furthermore, in high mineralization environments, salt ions compete with methane for water molecule gaps and disrupt the hydrogen bond structure between water molecules, leading to a decrease in methane solubility. This reduces the loss of methane through dissolution in water, allowing more methane to remain in coal seams in an adsorbed or free state. The quantitative relationship between microbial activity and water mineralization shows that methanogenic activity is highest when TDS < 4000 mg/L; as TDS exceeds 4000 mg/L, the activity decreases significantly; and when TDS > 10,000 mg/L, methanogenic bacteria basically die [26,33].

Multiple aquifer–aquitard sequences are developed within the coal measures of the study area, with weak hydraulic connectivity between layers, forming a vertically sealed hydraulic system. Coal seam water has total dissolved solids (TDS) ranging from 1025 to 24,078 mg/L and pH values of 7 to 9. Cations are dominated by Na+ and K+, with minor Ca2+ and Mg2+, resulting in a water type that ranges from weakly to strongly mineralized, is weakly alkaline and classified as Cl–HCO3–Na (Table 2).

Table 2.

Major ion concentrations and water types of coal seam water samples in the study area.

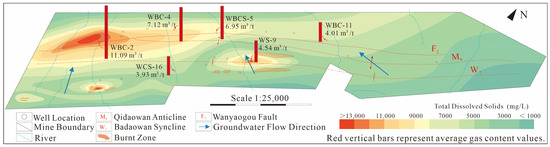

Planar distribution shows TDS decreasing from west to east and increasing from south to north, forming a high mineralization zone in the northwest with average TDS > 8000 mg/L, whereas southeastern areas generally exhibit low mineralization (TDS = 1000–4000 mg/L) (Figure 15). Typically, mineralization increases along groundwater flow directions, consistent with regional flow paths. However, the syncline’s southern limb—where burned zones are prevalent—experiences evaporation concentration, mineral oxidation, and stagnant-water effects, producing anomalously high mineralization; for example, around WCS-14 and WS-21 wells, TDS can exceed 15,000 mg/L. Vertically, water samples from 350 to 930 m show marked interlayer differences in mineralization, transitioning from weakly mineralized Quaternary water (TDS = 1330–2400 mg/L) to locally strongly mineralized Xishanyao Formation water (TDS = 24,078 mg/L), indicating an upward-increasing trend in TDS.

Figure 15.

Planar distribution of TDS in the study area.

Mineralization is a key hydrogeological indicator, and its spatial distribution is highly coupled with gas content. High mineralization centers (TDS > 8000 mg/L) occur in the northern monocline (358–936 m) and the western flank of the syncline’s north limb (545–911 m), where wells such as WBC-2 (11.09 m3/t) and WBC-4 (7.12 m3/t) show significantly elevated gas contents. In contrast, non-burned zones of the syncline’s southern limb (620–890 m) typically have TDS < 5000 mg/L and gas contents < 4 m3/t (e.g., WCS-16). Above 950 m, the coincidence of high gas content zones with TDS > 8000 mg/L underscores the regulatory role of hydrogeology in CBM generation and preservation.

Overall, the northern monocline and the syncline’s north limb serve as end-points for regional flow, where weakened groundwater flow fosters high mineralization. This environment suppresses methanogenic activity and limits biogenic gas generation but significantly enhances hydraulic sealing, promoting gas retention. Conversely, the syncline’s southern limb features low mineralization conditions and weakly alkaline water chemistry that support methanogen metabolism, and the abundant organic matter in seams 42–43 and 45 favors biogenic gas production. However, active groundwater flow dissolves CH4 and transports it along flow paths, undermining gas preservation. Additionally, in burned zones, groundwater evaporation and heat-induced ion release lead to concentrated, high TDS while consuming organic matter or gas, and fractures facilitate rapid gas escape. Eastern areas of the mining district exhibit low mineralization but have thin, scarce, and discontinuous seams, resulting in insufficient gas supply.

4.5. Structural Controls

The study area is characterized by intense tectonic activity. Located in the foreland thrust belt on the southern margin of the Junggar Basin, it has formed a complex syncline-thrust fault zone composite tectonic system under the sustained northeastward compression of the Himalayan Tianshan orogenic belt. The current tectonic framework and in situ stress field characteristics jointly control the preservation and distribution of coalbed methane (CBM).

There are significant differences in the attitude of tectonic units within the area: the southern limb of the syncline has a dip angle of 62–85°, the northern limb 30–65°, and the northern monocline 70–85°. Theoretically, the steeper the dip angle of the fold limbs, the more developed the tensile fractures, and the more CBM escape channels. Actually, due to the relatively gentle dip angle of the northern syncline limb, the development of tensile fractures is limited, resulting in better gas-bearing properties than the southern limb. For example, the average gas contents of Wells WCS-7 and WC-7 are 5.70 m3/t and 5.11 m3/t, respectively. Additionally, local secondary compressive minor folds (near Lines 19 and 23) provide auxiliary sealing, making the reservoir sealing property of the northern limb superior to that of the southern limb. The southern syncline limb has significantly lower gas content—for instance, the average gas contents of Wells WCS-5 and WCS14 are both less than 4 m3/t—confirming the adverse impact of large stratal dip angles on CBM storage. However, despite a steep dip angle of 70–85°, the northern monocline has better gas-bearing properties than the gentler-dipping syncline limbs. For example, the main coal seams encountered by Wells WBCS-7 and WBCS-5 are distributed at depths of 717.4–833.0 m, with average gas contents both exceeding 7 m3/t. This is jointly attributed to the lateral sealing of the Wanyaogou Reverse Fault and the preservation effect of high mineralization stagnant water on deep coal seams in the northern monocline.

The preservation mechanism of high mineralization stagnant water has been elaborated in the previous text and will not be repeated here. The lateral sealing mechanism of the Wanyaogou Reverse Fault involves a series of processes in which compressive stress induces fault lithological transformation and permeability reduction. Controlled by the compressive stress at the northern margin of the Tianshan Mountains, a thrust fault was formed. During this tectonic activity, rocks on both sides of the fault plane underwent brittle fragmentation, forming a cataclastic rock zone with a width of 8–30 m. Meanwhile, mudstones from the coal seam roof and floor were mixed into the fault zone due to compressive folding, increasing the argillaceous content to approximately 30%. Sustained horizontal compressive stress further promoted the dense arrangement of cataclastic rock particles; argillaceous particles filled pores and underwent cementation, reducing the permeability of the fault zone to less than 0.1 mD. With ultra-low permeability or tight layer characteristics, the fault zone effectively blocks CBM escape channels along the fault in the northern monocline, forming a physical sealing barrier. Core records show that Well WBCS-7 passes through the footwall of the Wanyaogou Reverse Fault; the cataclastic rock in the fault zone is mainly mudstone interbedded with carbonaceous mudstone, and the permeability of the 850–862 m core interval is only 0.02 mD. Moreover, the Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) of the coal seam in this well reaches 13,292.51 mg/L, showing the characteristics of stagnant confined water. The difference in gas content between the southern syncline limb and the high-dip strata of the northern monocline reflects the mechanism of CBM enrichment controlled by the lateral sealing of the Wanyaogou Reverse Fault and the stagnant water environment [34].

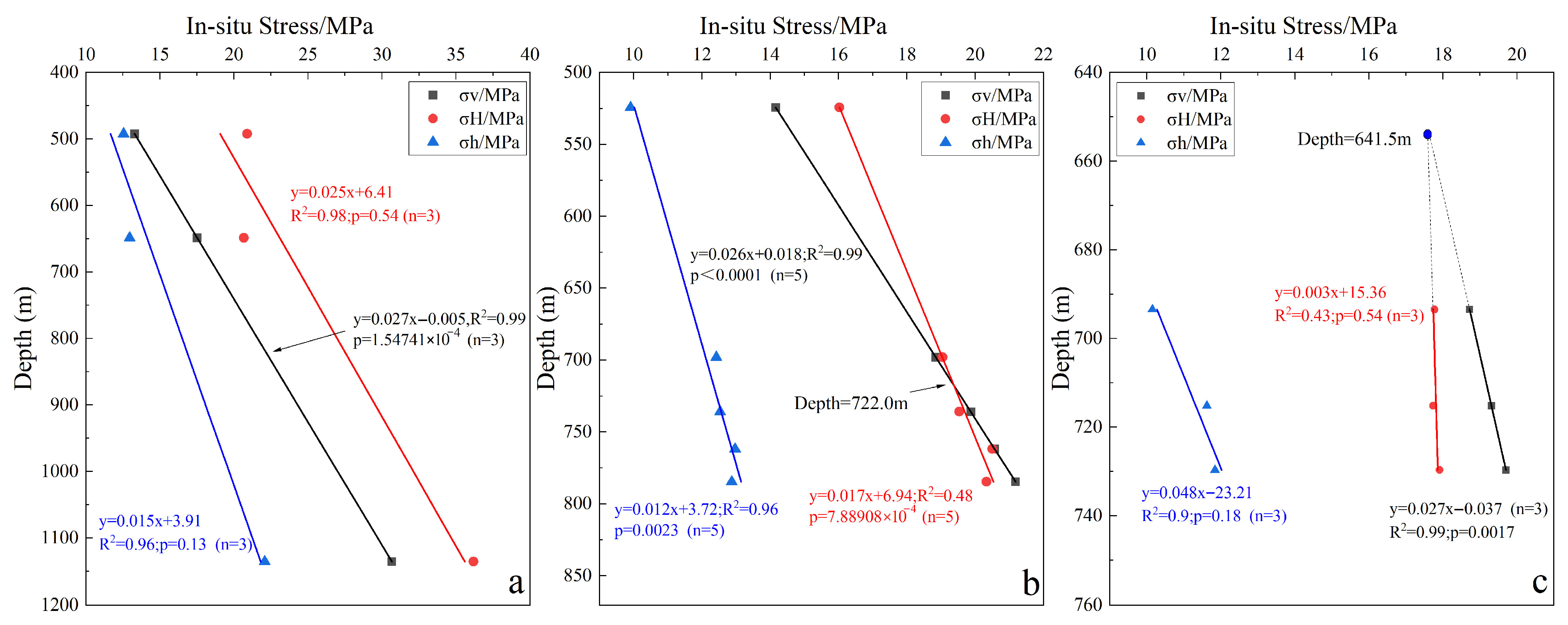

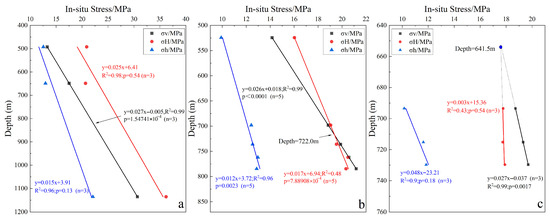

In addition to the physical sealing effect of the fault zone, the distribution characteristics of the regional present-day in situ stress field further enhance the differences in CBM preservation conditions among different tectonic units. The present ground stress characteristics of each tectonic unit in the study area are shown in Table 3 [35].

Table 3.

In situ Stress Characteristics of Different Structural Units in the Study Area.

In the depth range of 491.96–1135.42 m, the northern monocline exhibits a strike-slip fault-type (SF) in situ stress state with σH > σV > σh, and the horizontal stress difference ranges from 7.72 to 14.10 MPa. In the depth interval of 524.26–784.62 m, the northern syncline limb shows transitional in situ stress characteristics from shallow strike-slip type (σH > σV) to deep type (σH ≈ σV), with a horizontal stress difference of 6.11–7.53 MPa. In the depth interval of 693.43–729.67 m, the southern syncline limb presents a normal fault-type tensile in situ stress state with σV > σH > σh, and the horizontal stress difference is 6.07–7.62 MPa. It is inferred that the in situ stress state transitions from strike-slip type (σH > σV) to deep type (σH < σV) at a burial depth of approximately 640 m.

The distinct in situ stress characteristics of each unit affect CBM enrichment and loss through fracture modification. The northern monocline is in a strong compressive stress environment; the horizontal compression-dominated stress state not only enhances fault tightness but also effectively inhibits the development and expansion of tensile fractures in coal seams, thereby reducing gas seepage and escape channels and creating a favorable stress environment for CBM preservation. This critical favorable mechanical background further offsets the potential adverse impact of steeply dipping strata. The northern syncline limb is located in the NF-SF transitional zone and under a relatively favorable compressive stress environment. Although its in situ stress state shows a transition from shallow strike-slip type to deep type (σH ≈ σV), it is still affected by horizontal compression overall. This moderate-intensity compression effectively inhibits fracture expansion; in addition, local stress concentration zones formed by secondary compressive folds near Lines 19 and 23 further enhance fracture closure and local sealing capacity. The southern syncline limb is dominated by a tensile stress field, which is unfavorable for gas preservation. Furthermore, the sustained tensile environment below 640 m is conducive to fracture development and maintenance of openness, and the large-dip strata further amplify the tensile effect—making fracture networks prone to connectivity and providing preferential channels for gas escape, resulting in an overall poor reservoir sealing property (Figure 16).

Figure 16.

Relationship between three-dimensional in situ stress and burial depth in different structural units of the study area ((a): Northern Monocline; (b): Northern Wing of Badaowan Syncline; (c): Southern Wing of Badaowan Syncline; Data points in the figure are from [35]).

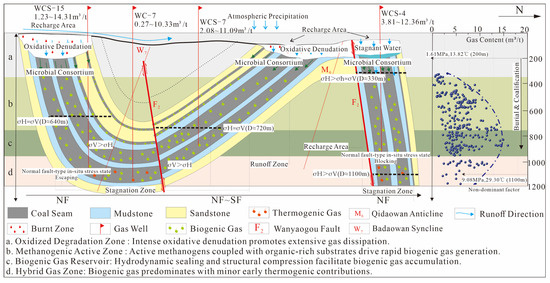

4.6. Integrated Geological Controls

The enrichment characteristics of CBM in the study area result from the complex spatiotemporal interplay of gas generation, reservoir properties, and preservation conditions. Measured gas contents range from 0.01 to 16.31 m3/t, with CH4 volume fractions averaging 79.12%. This pronounced planar heterogeneity and vertical zonation are the integrated outcome of multi-factor synergy and their dynamic interactions.

The temporal sequence of gas generation provides the material basis. A limited volume of early thermogenic gas, genetically identified as transitional zone gas, was formed during the Late Cretaceous under low maturity conditions (RO,max ≈ 0.5–0.78%). Following Cenozoic uplift into a shallow, low-temperature regime (<38 °C), meteoric recharge introduced microbial consortia that generated widespread primary biogenic gas, while partially converting the early gas into secondary biogenic gas. Critically, the present high mineralization environment (TDS commonly > 8000 mg/L) suppresses large-scale methanogenesis but acts as an effective seal for paleo-gas accumulations. This evolutionary path underscores a key temporal decoupling: the conditions most favorable for biogenic gas generation (lower mineralization, active recharge) preceded the establishment of the current high mineralization, stagnant regime that optimizes gas sealing.

The preservation and current distribution of this mixed-origin gas are governed by structural and hydrogeological conditions, which vary significantly across structural units. The enrichment in each unit results not merely from the presence of individual factors, but from their specific coupling and net effect. Deep seams (750–950 m) in the northern monocline constitute the most favorable enrichment zone, where a synergistic combination exists: the Wanyaogou reverse fault (F2) provides lateral sealing through its low-permeability fault zone, and high-TDS stagnant water inhibits vertical migration under a strike-slip stress regime (σH > σV), creating a composite seal more effective than either mechanism alone. The northern syncline limb represents a moderate enrichment area, benefiting from a deep oxidative weathering zone (base ~360 m) and water-retentive slopes under a transitional stress state. In contrast, the southern syncline limb is a gas migration and loss zone, where steep dips, a tensile stress field (σV > σH), and active groundwater flow lead to low gas contents (<3.5 m3/t). The syncline core, while hydrodynamically stagnant, has insufficient gas supply in deep seams (>1000 m) due to limited early gas and inhibited microbial activity. The observed decrease in gas content below ~950 m, despite increasing burial pressure, highlights a critical process competition: the positive effect of pressure on adsorption is eventually offset by the diminishing biogenic gas supply (inhibited under high TDS) and the increasing influence of temperature and fracture-associated escape pathways.

In summary, the CBM enrichment pattern is a legacy of the basin’s burial-uplift history, shaped by dynamic and often competing interactions between controlling factors. Past biogenic and transitional-zone gases are preferentially preserved in structural compartments that combine effective lateral fault sealing, hydrodynamic stagnation, and a stress state favoring fracture closure. This differential coupling explains the distinct “high in the northwest, low in the southeast” planar distribution and the vertical enrichment peak at 750–950 m (Figure 17).

Figure 17.

Combined structural–hydrogeological gas control model for the study area [36].

5. Conclusions

(1) Coal in the study area is of a medium–low rank (RO,max 0.50–0.78%; coal rank I–II). The dominant maceral is vitrinite (average 70.30%). Low fixed carbon (average 45.12%), high volatility (25.61–54.93%, average 37.23%), and elevated ash (11.65–20.44%) and moisture (1.75–3.95%) significantly suppress Langmuir volume. Seams 42–43 and 45 of the Xishanyao Formation, with high vitrinite (>80%) and low ash (<12%), constitute the optimal CBM reservoirs.

(2) Gas content ranges from 0.01 to 16.31 m3/t, exhibiting a planar heterogeneity that is high in the northwest and low in the southeast. Vertically, three zones are evident: oxidation loss in shallow seams (<360 m), concentrated enrichment at mid-depth (360–950 m), and attenuation in deep seams (950–1200 m). The peak interval (750–950 m) yields average gas contents of 6–10 m3/t. CH4 volume fractions are relatively low (average 79.12%), and CO2 is anomalously enriched (average 15.11%) due to microbial activity and inputs from burned zones.

(3) The CBM in the mining area is predominantly of primary biogenic origin, generated primarily via CO2 reduction with a subsidiary contribution from acetate fermentation. A minor component of early thermogenic gas is present, exhibiting characteristics of thermocatalytic transitional zone gas. Microbial degradation and alteration of this early thermogenic gas yielded a portion of secondary biogenic gas. Shallow burial depths (<1000 m), low temperatures (<38 °C), and weakly alkaline formation water (pH > 7.2) favored biogenic gas generation and preservation, simultaneously constraining large-scale thermogenic gas production.

(4) The migration and enrichment of CBM in the mining area are primarily governed by burned zones, the depth of the oxidative weathering zone, and structural-hydrodynamic coupling. Burned zones and a relatively deep oxidative weathering zone (360 m) are the primary causes of gas escape from shallow seams. Gas dissipation is exacerbated on the southern syncline limb by steeply dipping seams and active groundwater flow, resulting in low gas content (<3.50 m3/t). In the mid-depth zones (360–950 m) of the northern syncline limb and the northern monocline, the synergistic combination of lateral sealing by the F2 reverse fault and high-TDS stagnant water creates favorable conditions for CBM enrichment. In the deep core of the Badaowan Syncline, a transition to a normal-fault stress regime (σH < σV) and insufficient supply of both biogenic and thermogenic gas jointly lead to a decrease in gas content.

6. Exploration and Development Implications

Based on the CBM enrichment laws and comprehensive gas control mechanisms (including genesis, coal quality, burial depth, structure, and hydrogeology) of the Xishanyao Formation in the Hedong mining area, the following key recommendations for CBM exploration and development under similar geological conditions are proposed:

(1) Prioritize precise target selection based on “structural-hydrodynamic coupling”: Give priority to compressional stress structural locations superimposed by lateral sealing of reverse faults and high mineralization stagnant water environments (e.g., below the weathering zone of the northern monocline in this study area). The high-mineralization stagnant water zones provide effective hydraulic sealing for paleo-gas accumulations. Vertically, the 360–950 m interval is the most favorable: it avoids gas escape from the shallow weathering-oxidation zone and coincides with the primary gas-generating layer of ancient microbial communities. This interval represents the optimal depth where “structural sealing” and “gas supply” synergistically combine.

(2) Avoid major geological risks and implement differentiated development: Proactively avoid tectonically uplifted limbs with steeply dipping strata, developed tensile fractures, and active groundwater (e.g., the southern syncline limb). For favorable areas such as the northern monocline, optimize wellbore structure to adapt to steeply dipping strata; considering the dominance of biogenic gas, explore suitable microbial enhancement stimulation technologies to tap the potential of continuous gas production.

(3) Deepen the understanding of gas genesis to guide exploration and evaluation directions: In similar medium-low rank coal areas, establish the reservoir-forming concept of “biogenic gas dominance”. The focus of exploration and evaluation should shift from searching for deep thermogenic gas to comprehensively evaluating current hydrogeological conditions and biogenic gas generation potential, so as to more accurately guide exploration decisions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.W. and X.Z.; methodology, S.Y. and N.Z.; validation, X.W. and L.W.; investigation, P.L.; resources, H.W., S.Y., S.S. and Y.W.; data curation, X.Z., Y.F. and X.W.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Z.; writing—review and editing, H.W. and X.L.; supervision, S.S.; funding acquisition, H.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42262021, 41902171), Major Science and Technology Projects of Xinjiang Major Science and Technology Special Project (2023A01004-1), Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Tianshan Talent Plan (2023TSYCLJ0005).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Yibing Wang and Peng Lai were employed by the company Xinjiang Yaxin Coalbed Methane Investment and Development (Group) Co., Ltd. and the Xinjiang Yaxin Coalbed Methane Resource Technology Research Limited Liability Company. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CBM | Coalbed Methane |

| TOC | Total Organic Carbon |

| TDS | Total Dissolved Solids |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Sampling Information of Core Samples in the Study Area.

Table A1.

Sampling Information of Core Samples in the Study Area.

| Structural Part | Well Number | Sample Number | Coal Seam | Sampling Depth (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Monocline | WBC-1 | WBC-1-43-1 | 42–43 | 309.74 |

| WBC-1-43-20 | 42–43 | 383.92 | ||

| WBC-1-45-15 | 45 | 483.20 | ||

| WBC-2 | WBC-2-1 | 41 | 274.80 | |

| WBC-2-14 | 41 | 356.35 | ||

| WBC-2-20 | 42–43 | 421.00 | ||

| WBC-2-26 | 45 | 438.90 | ||

| WBC-3 | WBC3-1 | 2–3 | 434.28 | |

| WBC3-2 | 2–3 | 446.32 | ||

| WBC3-3 | 4–5 | 539.4 | ||

| WBC3-4 | 4–5 | 546.08 | ||

| WBC3-5 | 4–5 | 549.01 | ||

| WBC3-6 | 4–5 | 552.08 | ||

| WBC-4 | WBC-4-12 | 41 | 359.16 | |

| WBC-4-27 | 41 | 396.86 | ||

| WBC-4-42 | 42–43 | 479.17 | ||

| WBC-4-45 | 45 | 532.28 | ||

| WBC-9 | WBC-9-1 | 41 | 774.35 | |

| WBC-9-9 | 42–43 | 882.35 | ||

| WBC-9-25 | 42–43 | 984.85 | ||

| WBC-9-31 | 45 | 1023.37 | ||

| WBC-10 | WBC-10-20-1 | 10–12 | 699.85 | |

| WBC-10-X-1 | 10–12 | 702.84 | ||

| WBC-10-X2-1 | 10–12 | 707.70 | ||

| WBC-10-X2-7 | 20–22 | 822.49 | ||

| WBC-11 | WBC-11-5 | 2–3 | 385.00 | |

| WBC-11-10 | 2–3 | 435.65 | ||

| WBC-11-30 | 4 | 630.20 | ||

| WBC-11-42 | 6–9 | 647.70 | ||

| WBC-12 | WBC-12-11-1 | 10–12 | 278.38 | |

| WBC-12-15-1 | 41 | 337.88 | ||

| WBC-12-15-6 | 41 | 342.55 | ||

| WBC-12-15-1 | 42–43 | 741.36 | ||

| WBC-12-15-2 | 42–43 | 747.81 | ||

| WBC-13 | WBC-13-5 | 41 | 526.54 | |

| WBC-13-16 | 41 | 577.54 | ||

| WBC-13-20 | 42–43 | 751.54 | ||

| WBC-13-33 | 42–43 | 796.54 | ||

| WBCS-5 | WBCS-5-1 | 42–43 | 503.50 | |

| WBCS-5-2 | 45 | 780.10 | ||

| WBCS-5-3 | 20–22 | 1141.20 | ||

| WBCS-5-4 | 20–22 | 1144.90 | ||

| WBCS-5-5 | 27 | 1050.30 | ||

| WBCS-5-6 | 20–22 | 1151.40 | ||

| WBCS-7 | WBCS-7-41-4 | 41 | 663.90 | |

| WBCS-7-4X1-4 | 42–43 | 730.90 | ||

| WBCS-7-43-4 | 45 | 800.20 | ||

| WBCS-7-43-11 | 45 | 833.43 | ||

| WBS-2 | WBS-2-1 | 42–43 | 286.00 | |

| WBS-2-2 | 42–43 | 358.50 | ||

| WBS-2-3 | 42–43 | 377.80 | ||

| WBS-2-5 | 45 | 716.50 | ||

| Northern wing of Badaowan Syncline | WCS-7 | WCS-7-41-1 | 41 | 559.90 |

| WCS-7-4X-1 | 41 | 597.03 | ||

| WCS-7-43-5 | 42–43 | 699.81 | ||

| WCS-7-43-18 | 42–43 | 741.02 | ||

| WCS-7-45-17 | 45 | 879.31 | ||

| WS-8 | 42-43-1 | 42–43 | 704.59 | |

| 42-43-11 | 42–43 | 731.79 | ||

| 45-1 | 45 | 828.50 | ||

| 45-10 | 45 | 852.40 | ||

| 45-17 | 45 | 874.00 | ||

| WS-9 | 42-43-1 | 42–43 | 769.50 | |

| 42-43-9 | 42–43 | 790.67 | ||

| 45-1 | 45 | 886.50 | ||

| 45-9 | 45 | 908.50 | ||

| 45-16 | 45 | 935.50 | ||

| WS-10 | 42-43#-1 | 42–43 | 585.30 | |

| 42-43#-2 | 42–43 | 601.60 | ||

| 45#-1 | 45 | 694.00 | ||

| 45#-2 | 45 | 706.00 | ||

| 45#-3 | 45 | 726.50 | ||

| WS-11 | WS-11-1 | 42–43 | 628.40 | |

| WS-11-2 | 42–43 | 707.50 | ||

| WS-11-4 | 45 | 742.80 | ||

| WS-12 | WS-12-1 | 42–43 | 545.30 | |

| WS-12-2 | 42–43 | 582.40 | ||

| WS-12-3 | 45 | 683.10 | ||

| WS-12-4 | 45 | 714.50 | ||

| WS-13 | WS-13-1 | 42–43 | 588.50 | |

| WS-13-2 | 42–43 | 596.30 | ||

| WS-13-4 | 45 | 673.00 | ||

| WS-13-5 | 45 | 680.90 | ||

| WS-17 | WS-17-1 | 42–43 | 352.00 | |

| WS-17-2 | 42–43 | 439.00 | ||

| WS-17-3 | 45 | 693.00 | ||

| WS-17-4 | 45 | 722.00 | ||

| WS-4 | 43#-1-1 | 42–43 | 695.30 | |

| 43#-1-2 | 42–43 | 744.60 | ||

| 43#-1-3 | 42–43 | 773.50 | ||

| 45#-1 | 45 | 896.30 | ||

| 45#-2 | 45 | 951.80 | ||

| WS-5 | WS-5-1 | 42 | 792.40 | |

| WS-5-2 | 42 | 802.00 | ||

| WS-5-3 | 43 | 842.00 | ||

| WS-5-4 | 43 | 898.90 | ||

| WS-6 | WS-6-1 | 41 | 683.00 | |

| WS-6-2 | 42–43 | 756.30 | ||

| WS-6-3 | 42–43 | 883.80 | ||

| WS-6-4 | 45 | 934.10 | ||

| WS-21 | WS-21-1 | 42–43 | 436.60 | |

| WS-21-2 | 42–43 | 486.00 | ||

| WS-21-3 | 42–43 | 502.90 | ||

| WS-21-4 | 45 | 573.50 | ||

| WS-21-5 | 45 | 644.60 | ||

| Southern wing of Badaowan Syncline | WCS-22 | 6-1 | 6–9 | 299.40 |

| 8 | 6–9 | 438.30 | ||

| 11-3 | 10–12 | 595.50 | ||

| 16 | 10–12 | 737.30 | ||

| 20-2 | 20–22 | 874.80 | ||

| WCS-5 | WCS-5-1 | 42–43 | 812.05 | |

| WCS-5-2 | 42–43 | 985.50 | ||

| WCS-5-3 | 42–43 | 1007.05 | ||

| WCS-5-4 | 45 | 1135.40 | ||

| WCS14 | WCS14-43-1 | 42–43 | 702.75 | |

| WCS14-43-6 | 42–43 | 740.80 | ||

| WCS14-45-1 | 45 | 855.10 | ||

| WCS14-45-10 | 45 | 869.30 | ||

| WCS-15 | WS-15-43-1-1 | 42–43 | 792.30 | |

| WS-15-43-2-1 | 42–43 | 851.50 | ||

| WS-15-43-2-9 | 42–43 | 862.20 | ||

| WS-15-45-1 | 45 | 992.72 | ||

| WS-15-45-16 | 45 | 1009.10 | ||

| WCS-16 | 43-1 | 42–43 | 538.46 | |

| 43-8 | 42–43 | 610.00 | ||

| 43-13 | 42–43 | 670.00 | ||

| 45-1 | 45 | 843.50 | ||

| 45-10 | 45 | 886.40 | ||

| WCS-4 | 43-1 | 42–43 | 518.70 | |

| 43-11 | 42–43 | 534.30 | ||

| 45-1 | 45 | 691.70 | ||

| 45-7 | 45 | 718.00 | ||

| 45-11 | 45 | 734.90 | ||

| WCS-3 | WCS-3-2 | 42–43 | 724.90 | |

| WCS-3-3 | 42–43 | 747.50 | ||

| WCS-3-4 | 45 | 807.37 | ||

| WCS-3-5 | 45 | 854.40 | ||

| W5-X1 | X1-1 | 42–43 | 601.75 | |

| X1-2 | 42–43 | 625.45 | ||

| X1-3 | 42–43 | 651.00 | ||

| W5-X2 | X2-1 | 45 | 840.00 | |

| X2-2 | 45 | 870.20 | ||

| X2-3 | 45 | 938.64 |

References

- Cao, L.L.; Lv, M.; Li, C.Y.; Sun, Q.; Wu, M.Q.; Xu, C.X.; Dou, J.W. Effects of Crosslinking Agents and Reservoir Conditions on the Propagation of Fractures in Coal Reservoirs During Hydraulic Fracturing. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.Y.; Liu, J.Y.; Xia, Y.F. Risk Prediction of Gas Hydrate Formation in the Wellbore and Subsea Gathering System of Deep-Water Turbidite Reservoirs: Case Analysis from the South China Sea. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Chen, S.D.; Pan, Z.J. Current status, challenges, and policy suggestions for coalbed methane industry development in China: A review. Energy Sci. Eng. 2019, 7, 1059–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, M.; Chen, H.; Chen, Y.P.; Zeng, L.J.; Chen, S.S.; Jiang, X.C. Methods and results of the fourth round of national CBM resources evaluation. Coal Sci. Technol. 2018, 46, 64–68. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/doi/10.13199/j.cnki.cst.2018.06.011 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Tao, C.Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.B.; Ni, X.M.; Wu, X.; Zhao, S.H. Characteristics of deep coal reservoir and key control factors of coalbed methane accumulation in linxing area. Energies 2023, 16, 6085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.R.; Kaiser, W.R.; Ayers, W.B., Jr. Thermogenic and secondary biogenic gases, San Juan Basin, Colorado and New Mexico—Implications for coalbed gas producibility. AAPG Bull. 1994, 78, 1186–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, S.K.; Esterle, J.S.; Golding, S.D. Geological interpretation of gas content trends, Walloon subgroup, eastern Surat Basin, Queensland, Australia. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2012, 101, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.Y.; Zhang, H.D.; Zhou, Z.; Ge, Z.L.; Chen, C.J.; Hou, Y.D.; Ye, M.L. Current status and effective suggestions for efficient exploitation of coalbed methane in China: A review. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 9102–9123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Lin, X.; Zhao, M.; Song, Y.; Liu, S. The upper Paleozoic coalbed methane system in the Qinshui basin, China. AAPG Bull. 2005, 89, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xiong, X.Y.; Xu, L.F.; Xu, F.Y.; Zhang, W.Q.; Xie, J.F.; Li, Y. Inspirations of typical commercially developed coalbed methane cases in China. Coal Sci. Technol. 2025, 53, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Song, Y.; Zhao, W.; Bo, D.; Liu, S.; Hao, J.Q. Main controlling factor of coalbed methane enrichment area in southern Qinshui Basin, China. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2024, 14, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.C.; Xu, F.Y.; Wang, H.Y.; Li, S.G.; Lin, W.J.; Wang, W.; Hao, S. Exploration and development process of coalbed methane in eastern margin of Ordos Basin and its enlightenment. Coal Geol. Explor. 2022, 50, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.J.; Sang, S.X. Progress of research on coalbed methane exploration and development. Pet. Geophys. Prospect. 2022, 61, 951–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.F.; Sun, B.; Lu, J.; Tian, W.G. Comparative analysis on the enrichment patterns of deep and shallow CBM in Junggar Basin. J. China Coal Soc. 2019, 44, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiticar, M.J. Carbon and hydrogen isotope systematics of bacterial formation and oxidation of methane. Chem. Geol. 1999, 161, 291–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.X.; Qi, H.F.; Song, Y.; Guan, D.S. Coalbed methane components, carbon isotope types and their genesis and significance in China. Sci. China Ser. B-Chem. Biol. Agric. Med. Earth Sci. 1986, 16, 1317–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milkov, A.V.; Etiope, G. Revised genetic diagrams for natural gases based on a global dataset of >20,000 samples. Org. Geochem. 2018, 125, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.Z.; Yang, S.G.; Tang, S.L.; Tao, S.; Chen, S.D.; Zhang, A.B.; Pu, Y.F.; Zhang, T.Y. Advance on exploration-development and geological research of coalbed methane in the Junggar Basin. J. Coal 2021, 46, 2412–2425. Available online: https://www.mtxb.com.cn/en/article/id/ced84ddd-2fa5-413b-9bf4-c3c014357207?viewType=HTML (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Yang, S.Y.; Wei, L.; Yuan, X.H.; Zheng, S.J.; Yao, Y.B. Analysis of coal reservoir gas characteristics and main controlling factors in Hedong mining area, Urumqi city, Xingjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. Nat. Gas Earth Sci. 2019, 30, 1667–1675. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 19559-2021; Method of Determining Coalbed Methane Content. State Administration for Market Regulation; Standardization Administration: Beijing, China, 2021.

- Wu, J.; Zhang, S.H.; Jia, T.F.; Chao, W.W.; Peng, W.C.; Li, S.L. Analysis of pressure-maintaining coring process in deep coal seams and gas content determination methods. Pet. Geol. Exp. 2025, 47, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, H.L.; Wang, H.C.; Tian, J.J.; Yang, S.B.; Cheng, X.Q. Discussion on the genesis of coalbed methane in Fukang mining area. Coal Mine Saf. 2021, 52, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.X.; Ni, Y.Y.; Qin, S.F.; Huang, S.P.; Peng, W.L.; Han, W.X. Geochemical characteristics of ultra-deep natural gas in the Sichuan Basin, SW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2018, 45, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, N.S.; Yang, H.B.; Wang, X.L. Tectono-Thermal evolution in the Junggar Basic. Chin. J. Geol. 2002, 37, 423–429. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279691475_Tectono-thermal_evolution_in_the_Junggar_Basin (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Wang, B.; Li, J.M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.Y.; Liu, H.L.; Li, G.Z.; Ma, J.Z. Geological characteristics of low rank coalbed methane, China. Pet. Explor. Dev. China 2009, 36, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]