Abstract

Wet coffee pulp residues (WCPRs) are typically underutilized, and their accumulation increases alongside coffee production, generating significant environmental impacts. This study proposes a sustainable valorization approach through hydrothermal treatment followed by membrane filtration for the production of xylooligosaccharides (XOSs). Extractive-free WCPR contained 35.4% structural carbohydrates (20.4% cellulose and 15.0% hemicellulose) and 27.0% lignin. Hydrothermal treatments (180 °C, 3 °C min−1, 15–60 min) were performed with and without citric acid as an organic catalyst. The acid-assisted treatment (T4) enhanced hemicellulose depolymerization and xylose release (16 g·kg−1 dry biomass), whereas milder, non-acidic conditions (T3) promoted the selective formation and recovery of short-chain XOS, reaching cumulative biomass-normalized yields of up to 14 g·kg−1 of xylobiose (X2) and 9 g·kg−1 of xylotriose (X3). Subsequent membrane processing (UF–DF–NF) enabled progressive purification and enrichment of XOS fractions. Diafiltration was identified as the main step governing XOS enrichment, whereas nanofiltration primarily refined separation by directing monomeric sugars to the permeate rather than substantially increasing XOS yields. Additionally, Multiple Factor Analysis (MFA) integrated process and compositional variables, explaining 79.6% of the total variance. Dimension 1 represented process intensity and xylose transport, while Dimension 2 reflected molecular-weight-driven XOS fractionation. The acid-assisted process (T4) exhibited a distinct multivariate signature, characterized by enhanced carbohydrate mobilization and improved XOS recovery with reduced dependence on dilution. Overall, coupling hydrothermal pretreatment with membrane fractionation proved to be an efficient, and environmentally friendly strategy for coffee by-product valorization, consistent with hemicellulose-first biorefinery models and the principles of the circular bioeconomy.

1. Introduction

Coffee (Coffea arabica) represents approximately 70% of global coffee production and is the most cultivated and consumed species in South America. Together with Coffea canephora (robusta), it constitutes the two economically important varieties worldwide [1]. In 2023, national coffee production reached 82,734 tons.

Coffee processing is predominantly conducted using the wet method, where the cherries undergo depulping to remove the skin and mesocarp, generating coffee beans covered with a mucilaginous parchment layer. This operation produces large amounts of residual biomass composed of the pericarp, mesocarp, mucilage, and minor portions of parchment [2]. Only about 60% of the coffee cherry mass is converted into green coffee beans, while the remaining fraction—mainly pulp and mucilage—is typically discarded or underutilized [1,2].

Wet coffee pulp residues (WCPRs) constitute a major agro-industrial byproduct whose accumulation poses environmental challenges, particularly in coffee-producing regions. From a biorefinery perspective, WCPRs constitute a promising feedstock owing to their high levels of structural cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin [1,2]. Despite this compositional potential, most valorization studies have focused on energy-oriented applications, including hydrothermal conversion to biochar and bio-oil, biogas and hydrogen production, or the generation of adsorbent materials for environmental remediation [3,4,5,6].

In contrast, the selective recovery of hemicellulose-derived products from coffee pulp has received comparatively limited attention. Among these products, xylooligosaccharides (XOSs) have attracted increasing interest due to their recognized prebiotic functionality and applications in functional foods. XOSs selectively stimulate beneficial gut microbiota and have been associated with improved mineral bioavailability, immune modulation, and antioxidant activity, supporting their incorporation into nutraceutical and food formulations [7,8,9].

Hydrothermal treatment offers a green and tunable approach for hemicellulose depolymerization, enabling the production of low-degree-of-polymerization XOS under controlled temperature and pressure without the use of mineral acids [10,11,12]. However, studies on coffee pulp hydrothermal processing have largely evaluated this technology as a standalone step, with limited emphasis on downstream separation. Integrated hydrothermal–membrane systems, which can substantially enhance XOS purity and recovery through size-selective fractionation, remain scarcely explored for coffee pulp residue [13,14].

To address these gaps, the present study investigates an integrated hydrothermal–membrane strategy for the valorization of WCPR, introducing two main innovations compared to previous works: (i) the use of citric acid as a mild organic catalyst to assist hemicellulose depolymerization, which has not yet been systematically evaluated for coffee pulp; and (ii) the application of a multi-stage membrane sequence (ultrafiltration, diafiltration, and nanofiltration) to achieve progressive purification and fractionation of XOS.

In addition, Multiple Factor Analysis (MFA) is employed to simultaneously interpret process severity, membrane transport behavior, and product distribution. This multivariate approach provides an integrated framework for understanding the complex interactions governing XOS recovery and separation efficiency, and to the best of our knowledge, has not been previously applied to hydrothermal–membrane valorization of coffee pulp residues.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

All reagents used were of analytical grade. The chemicals included sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 72%, Emsure®, Darmstadt, Germany), sodium carbonate (Na2CO3, Emsure®), citric acid (C6H8O7, Emsure®), and disodium phosphate (Na2HPO4, Emsure®). High-purity standards such as D-cellobiose, D(+)-glucose, D(+)-xylose, and D(+)-galactose (Supelco, St. Louis, MO, USA) were employed, along with xylooligosaccharide (XOS) standards including xylose, xylobiose, xylotriose, and xylotetraose (Supelco). Ethanol 96% (Hersil) and HPLC-grade acetonitrile (CH3CN, Supelco) were used as solvents. The enzyme Cellic® CTec2 (Novozymes, Bagsværd, Denmark) was also employed for enzymatic assays.

2.2. Preconditioning of Wet Coffee Pulp Residues (WCPR)

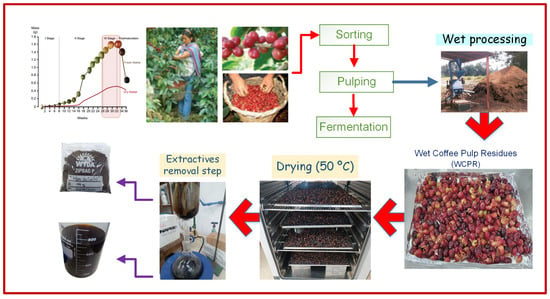

Wet coffee pulp residue (WCPR) from Coffea arabica L. var. Catimor was used as the lignocellulosic substrate. The material was obtained from wet processing of ripe coffee cherries was collected from farms located in the provinces of Jaén and San Ignacio, Cajamarca (Peru). After pulping at the farms, the WCPR was immediately transported to the Universidad Nacional de Jaén (UNJ), where it was subjected to convective drying at 50 °C until constant moisture (~10%) was reached. The dried material was then ground using a manual mill to reduce particle size to below 850 µm. Subsequently, the WCPR underwent a solid–liquid extraction (10%, raw material:solvent ratio) in a Soxhlet apparatus using 96% ethanol and distilled water as solvents to remove extractives. Each sample was siphoned within the Soxhlet for 2 h with ethanol and 6 h with distilled water, with solvent renewal every 2 h. This extraction procedure commonly used in NREL protocols effectively removes soluble sugars, phenolics, lipids, and other non-structural components. The extractive-free biomass was then oven-dried at 50 °C for 6 h until reaching ~10% final moisture and stored in airtight containers for subsequent chemical characterization and hydrothermal treatment (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sequence of preconditioning steps for wet coffee pulp residues (WCPR) from field to laboratory. Different arrow colors indicate distinct process stages: red arrows show the main processing flow, blue arrows denote wet processing, and purple arrows represent extractives removal; dashed lines indicate intermediate steps.

2.3. Morphological and Chemical Characterization of WCPR

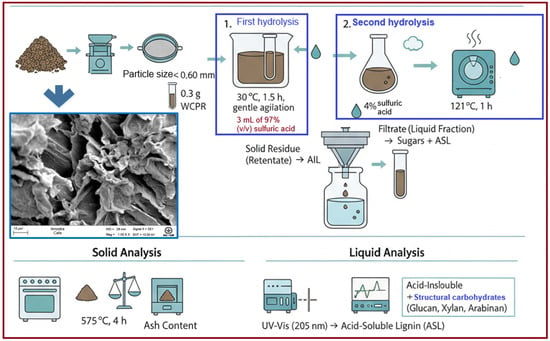

Morphological characterization was performed as a complementary analysis to the chemical studies. Samples were mounted on metallic stubs using double-sided carbon tape and coated with a ~10 nm gold layer using a MED020 sputter coater (BAL-TEC/MCS Multicontrol System, Balzers, Liechtenstein) to improve conductivity. SEM images were acquired with a LEO 1450VP microscope (LEO Electron Microscopy Ltd., Cambridge, UK) at 20 kV, using secondary electron detection and magnifications from 100× to 500×. The analyzed samples consisted of dried biomass. Figure 2 show SEM micrograph of the WCPR (1000×, 10 kV) showing a rough, porous, and irregular surface typical of biomass, indicating a large surface area and heterogeneous structure.

Figure 2.

Experimental workflow for the chemical and morphological characterization of coffee waste biomass, including two-step acid hydrolysis and subsequent solid and liquid analyses. The SEM image corresponds to wet coffee pulp residues (WCPR) prior to hydrothermal treatment, showing a porous and irregular surface typical of raw biomass. The asterisk (*) indicates the scale bar (10 µm) in the SEM micrograph.

WCPR was chemically characterized to determine its contents of extractives, cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, and ash. The analytical methods followed the standardized procedures established by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) [15]. Prior to analysis, the WCPR was ground and sieved using standard Tyler mesh sieves (28 mesh), obtaining a particle size smaller than 0.60 mm. The method employed a two-step acid hydrolysis to fractionate the biomass into components that could be more readily quantified by UV–Vis spectrophotometry and HPLC. The extractives and ash contents were also determined on a dry-matter basis.

In the first hydrolysis step, 0.3 g of extractive-free WCPR were weighed (based on the solid content determined from Equation (1)) and placed into test tubes. Subsequently, 3 mL of 97% (v/v) sulfuric acid were added. The tubes were maintained in a water bath at 30 °C for 1.5 h, with gentle agitation every 5 min, as shown in Figure 2.

The second step was initiated immediately after the first hydrolysis. The reaction mixture was transferred into 100 mL Erlenmeyer flasks, and 84 mL of distilled water were added to dilute the acid to approximately 4% H2SO4. The samples were then autoclaved at 121 °C for 1 h to complete the secondary hydrolysis of carbohydrates (Figure 2). After cooling, the samples were filtered through Gooch crucibles No. 3 under vacuum (Figure 2).

The filtrate (liquid fraction) was collected for sugar quantification by HPLC and for determination of acid-soluble lignin (ASL) by UV–Vis spectrophotometry at 205 nm. The solid residue (retentate) retained in the crucibles was dried at 105 °C for 5 h and weighed to estimate the acid-insoluble lignin (AIL) by mass difference (Figure 2).

The solid content, ash, extractives, acid-insoluble lignin (AIL), acid-soluble lignin (ASL), and structural carbohydrates were thus determined according to the NREL protocols. The solid content (%) was calculated by oven-drying the sample at 105 °C to constant weight, using Equation (1):

Ash content (%) was determined by calcining the dried sample at 575 °C for 4 h, as shown in Equation (2):

The extractives (%) were quantified after sequential Soxhlet extraction with 96% ethanol and distilled water, using Equation (3):

The acid-insoluble lignin (AIL) fraction was obtained as the residue after two-step acid hydrolysis (72% H2SO4 at 30 °C for 1 h, followed by 4% H2SO4 at 121 °C for 1 h). AIL was calculated as:

The acid-soluble lignin (ASL) was measured spectrophotometrically at 205 nm, according to Equation (5):

where A205 is the absorbance at 205 nm, D is the dilution factor, V is the total filtrate volume (L), M is the equivalent molecular weight of the lignin monomer (~100 g/mol), ε is the extinction coefficient (110 L g−1 cm−1), b is the path length (1 cm), and sample is the oven-dry mass (g).

The structural carbohydrates (glucan, xylan, arabinan, etc.) were determined from the hydrolysate by HPLC with a refractive index detector. The concentration of each monosaccharide (Ci) was used to calculate its corresponding polysaccharide content as follows:

where Ci is the concentration of each sugar (g/L), V is the total volume of hydrolysate (L), D is the dilution factor, and msample is the oven-dry mass (g).

To convert monosaccharides to their structural polysaccharide equivalents, the following anhydro correction factors were applied:

The factors 0.90 and 0.88 correspond to the anhydro-to-monomer mass ratios for hexoses and pentoses, respectively, and are standard corrections recommended by NREL.

2.4. Hydrothermal Treatment Processing for XOS Production

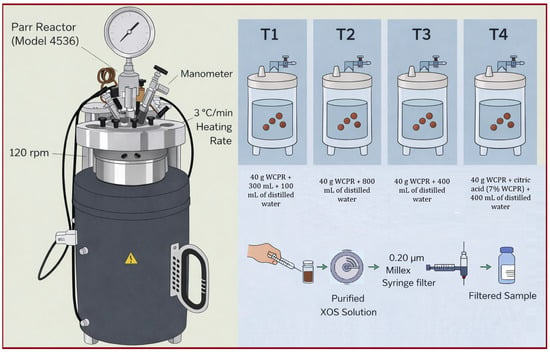

WCPR was subjected to hydrothermal treatment in a 1 L pressurized stirred-tank reactor (Model 4536, Parr Instrument Company, Moline, IL, USA), as shown in Figure 3. Four treatments were conducted (T1–T4). In T1, 40 g of WCPR were suspended in 300 mL of distilled water, and after 30 min of reaction, an additional 100 mL were added, totaling 400 mL. In T2, 40 g of WCPR were diluted in 800 mL of distilled water. In T3, 40 g of WCPR were mixed with 400 mL of distilled water. In T4, 40 g of WCPR were combined with citric acid (7% w/w, based on dry mass) and diluted in 400 mL of distilled water. The experimental setups for each treatment are illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Experimental setup and treatment conditions for hydrothermal treatment of WCPR in a Parr Reactor.

The process was evaluated at 15, 30, 45, and 60 min under fixed operating conditions: 180 °C, 120 rpm, and a heating rate of 3 °C min−1. Reaction time was recorded once the reactor reached the target temperature. During each treatment, 1 mL aliquots were withdrawn every 15 min, except for T1, where samples were collected at 30 and 60 min. Each aliquot was centrifuged for 5 min and filtered through a 0.20 µm syringe filter (Millex®, Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA), as shown in Figure 3. The effect of reaction time on XOS production was then analyzed using HPLC. After hydrothermal treatment, the reactor was cooled for approximately 5 min until the internal pressure dropped to atmospheric level. The resulting liquid and solid fractions were separated by filtration for subsequent XOS analysis. The liquid fractions from treatments T3 and T4 were selected for membrane purification. Concentrations of xylose and XOS (X2, X3, and X4) in the hydrolysate (liquid fraction) were determined using HPLC.

The experiments were performed in duplicate, and the results were expressed as average. Moreover, in all cases, the severity factor was calculated to assess and compare the intensity of the pretreatment. This parameter combines the effects of temperature (T) and time (t) into a single variable. For the hydrothermal treatment, the heating period (20–180 °C at 3 °C min−1) corresponded to approximately 53 min, followed by an isothermal phase of 30 min at 180 °C. The severity factor (log R0) integrates the effects of temperature and reaction time into a single parameter that quantifies the overall thermal load during hydrothermal treatment, allowing comparison of treatments conducted under different thermal conditions.

2.5. Membrane Filtration Process

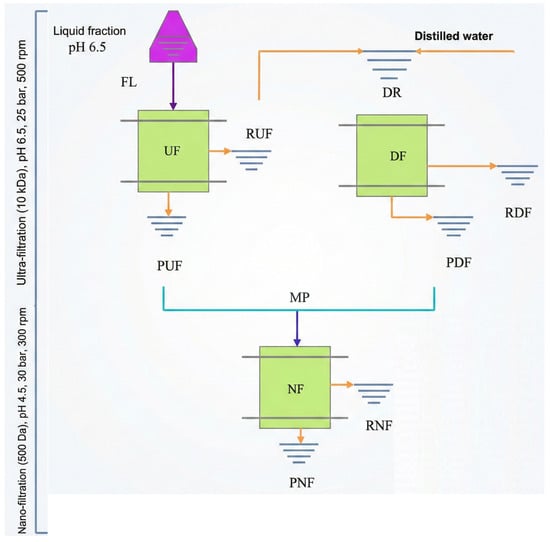

The hydrolysates obtained from treatments T3 and T4 after 60 min of hydrothermal treatment were independently subjected to ultrafiltration (UF), diafiltration (DF), nanofiltration (NF) (Figure 4). Before UF, the liquid fraction (feed liquid, FL) was adjusted from pH 8.0 to 6.5 and filtered using a Microdyn Nadir flat-sheet membrane (Microdyn Nadir GmbH, Wiesbaden, Germany) with a nominal molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) of 10 kDa at 25 bar and 500 rpm. This step generated a UF retentate (RUF), containing macromolecules >10 kDa, and a UF permeate (PUF), which included low–molecular-weight solutes that passed through the membrane.

Figure 4.

UF, DF and NF processing of XOS extract obtained by hydrothermal treatment. FL = feed liquid; UF = ultrafiltration; DF = diafiltration; NF = nanofiltration; RUF = UF retentate; PUF = UF permeate; DR = diluted UF retentate entering DF; RDF = DF retentate; PDF = DF permeate; MP = mixed permeates (PUF + PDF) fed to NF; RNF = NF retentate; PNF = NF permeate. Different arrow colors indicate the sequence of membrane operations and permeate/retentate streams.

The UF retentate was subsequently diluted with distilled water (1:1 v/v) to produce the diluted retentate (DR) and processed by diafiltration (DF) under the same operating conditions (25 bar, 500 rpm, 10 kDa MWCO). DF acts as a washing step that removes additional low–molecular-weight compounds, generating a DF permeate (PDF) and a DF retentate (RDF). The permeate streams from UF and DF (PUF and PDF), which contained soluble saccharides and other small molecules, were combined to form the mixed permeate (MP). This composite feed was adjusted to pH 4.5 before nanofiltration.

The mixed permeate (MP) was then subjected to nanofiltration (NF) at 30 bar and 400 rpm using a Microdyn Nadir 150 Da MWCO membrane. NF produced a retentate (RNF), enriched in xylooligosaccharides (XOS) larger than 150 Da, and a permeate (PNF) containing monomeric sugars, organic acids, and other small molecules. This NF retentate contributed the highest-purity XOS fraction obtained in the process.

The overall sequence of membrane operations—including the definition and role of each retentate and permeate stream (FL, RUF, PUF, DR, RDF, PDF, MP, RNF, PNF)—is summarized schematically in Figure 4.

2.6. Analytical Methods

Sugar monomers and xylooligosaccharides, such as xylobiose (X2), xylotriose (X3), xylotetraose (X4), xylopentaose (X5), and xylohexaose (X6), were analyzed by High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) UltiMate 3000 System (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with a refractive index detector (RefractoMax 521). For monomeric sugars, an HPX-87H column (300 × 7.8 mm; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) was used, and conditions were the following: 45 °C column temperature, 0.01 N H2SO4 as mobile phase, 0.6 mL/min flow rate, and 20 µL injection volume. For XOS (X2–X6) analysis, an Hyperrez XP Carbohydrate H + 8UM (300 × 7.7 mm; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) column was used, and conditions were the following: 70 °C of column temperature, water as mobile phase, 0.6 mL/min flow rate, and 20 µL injection volume.

2.7. Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s test at a 5% significance level to determine differences among treatments, using R software (v4.5.2). Additionally, Multiple Factor Analysis (MFA) was applied to evaluate correlations within the hydrothermal treatment. Three groups of variables were considered: (i) process parameters (Treatment, Catalyst, Time, Ratio, and Severity Factor, SF); (ii) xylose concentration (X1); and (iii) xylooligosaccharides (XOS: X2–X4). All quantitative variables were centered and scaled to unit variance, while qualitative factors (Treatment and Catalyst) were treated as supplementary variables.

To further analyze the characteristics of the membrane filtration process, a Multiple Factor Analysis (MFA) was carried out to integrate the process parameters and response variables obtained from the hydrothermal treatments (T3 and T4). The data matrix included three groups of variables: (i) process parameter (reaction volume), (ii) feedstock composition (X1), and (iii) response variables related to XOS production (X2–X4). Each group was normalized and equally weighted to ensure balanced contributions to the factorial structure.

MFA was performed using the FactoMineR package (version 2.12) and factoextra package (version 1.0.7) in RStudio (v4.5.2). Before analysis, all quantitative variables were centered and scaled to unit variance. The MFA extracted the main components based on the covariance structure among the groups, enabling the simultaneous evaluation of correlations both within and between variable sets.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Characterization of WCPR

The chemical characterization of extractive-free wet coffee pulp residues (WCPRs) revealed a predominance of lignocellulosic components. The total carbohydrate fraction accounted for 35.43 ± 0.02% of the dry matter, consisting of 15.04 ± 0.02% hemicellulose and 20.39 ± 0.02% cellulose. These values fall within the typical range reported for Coffea arabica pulp, where cellulose usually ranges around 20% and hemicellulose around 17% [3,16,17,18]. These results indicate that structural polysaccharides represent a significant proportion of the biomass, suggesting its potential as a source of fermentable sugars for bioconversion processes. The lignin content (27.04%) was composed of 21.93% acid-insoluble lignin (AIL) and 5.11% acid-soluble lignin (ASL). These values are similar to those reported by [3,16,17,19], confirming that wet coffee pulp exhibits a recalcitrant structure typical of lignocellulosic biomass, which may limit the efficiency of hydrolysis or anaerobic digestion processes if suitable pretreatments are not applied.

Differences in the proportions of both lignin and carbohydrates are attributed to the extractive content, although most studies do not explicitly report this factor. In the present study, a high extractive content (46.32%) was obtained through a solid–liquid extraction process using ethanol and water, standing out compared to other reports. In several studies, the soluble fraction of coffee pulp has been reported to range between 15% and 27% of dry weight [16,17,20]. Extractives are organic compounds that are not part of the plant cell wall and are soluble in water, neutral organic solvents, or volatile steam. Due to the high amount of soluble compounds present in coffee pulp, the extractives content is considerably high. This variation can be attributed to the presence of secondary metabolites, such as caffeine, chlorogenic acids, and phenolic compounds, which are abundant in coffee pulp obtained through the wet processing method.

3.2. XOS Production by Hydrothermal Treatment

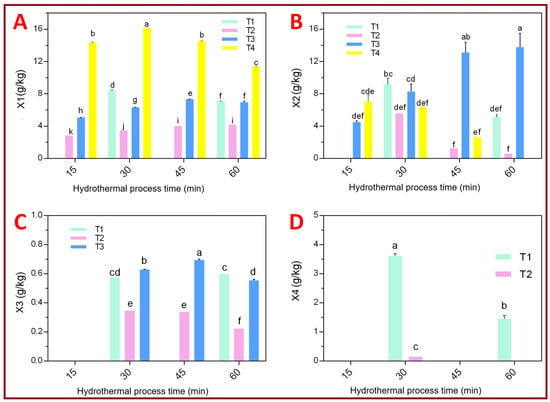

The hydrothermal treatment of wet coffee pulp residues (WCPRs) was carried out to assess the efficiency of structural carbohydrate conversion into xylooligosaccharides (XOSs) and xylose. The effects of dilution (solid-to-liquid ratio) and citric acid addition were examined to determine whether the acid exerted a synergistic catalytic effect on hemicellulose hydrolysis. In treatment T1, water was intentionally added in two sequential steps to ensure adequate mixing, hydration, and homogeneous heat transfer, considering the high water-absorption capacity of wet coffee pulp residues. This strategy resulted in a progressive increase in the effective solid-to-liquid ratio during the reaction, which directly influenced solubilization and product distribution. XOS were detected in the liquid fraction of all treatments and quantified relative to the initial dry mass. As shown in Figure 5, four hydrothermal treatments (T1–T4) were performed at 180 °C for 15–60 min, monitoring the evolution of xylose (X1), xylobiose (X2), xylotriose (X3), and xylotetraose (X4) by HPLC. Hydrothermal treatment uses pressurized hot water to promote hemicellulose autohydrolysis without the need for mineral catalysts, providing a clean and efficient alternative for lignocellulosic biomass conversion. The addition of citric acid improves selectivity toward XOS through a dual mechanism: as a weak organic acid, it promotes acid-catalyzed hydrolysis, and as a metal chelator, it sequesters trace metals, thereby facilitating selective β–O–4 bond cleavage in lignin-carbohydrate complexes while minimizing inhibitory by-product formation [21]. In the context of coffee pulp valorization, this approach allows the sustainable recovery of carbohydrate-rich fractions within an integrated biorefinery framework [3].

Figure 5.

Xylose and XOS (X2, X3, and X4) production from WCPR in hydrothermal conditions. Black vertical bars are the standard deviations. Different letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences among treatments according to Tukey’s HSD test (p < 0.05). (A): Effect of the treatment on xylose (X1) production; (B): Effect of the treatment on xylobiose (X2); (C): Effect of the treatment on xylotriose (X3); (D): Effect of the treatment on xylotetraose (X4).

Citric-acid-assisted hydrolysis (T4) yielded the highest xylose concentration (16 g·kg−1 at 30 min), indicating enhanced hemicellulose depolymerization and greater process severity (logR0 ≈ 4.17). In contrast, non-acidic conditions (T3) promoted the selective accumulation of xylobiose (14 g·kg−1) and xylotriose (0.7 g·kg−1), suggesting controlled depolymerization. Higher oligomers (X4) were preserved only under milder conditions (T1–T2), confirming that increased severity leads to complete hemicellulose hydrolysis, while moderate conditions favor XOS selectivity.

As shown in Figure 5A, the citric-acid treatment (T4) consistently produced the highest xylose concentrations across all reaction times, peaking at 16 g·kg−1 at 30 min and slightly decreasing to 11 g·kg−1 at 60 min. This decline reflects secondary degradation of xylose into furfural and organic acids under high-severity conditions. In comparison, T3 reached a maximum of 7 g·kg−1 at 45 min, T2 maintained moderate values (~4 g·kg−1) between 45 and 60 min, and T1 showed intermediate results (9 g·kg−1 at 30 min), which can be directly attributed to the two-step water addition strategy applied in this treatment. The gradual increase in water availability promoted biomass hydration and solubilization while simultaneously introducing a dilution effect, resulting in moderate xylose yields compared to single-step dilution treatments. Statistical analysis revealed significant differences among treatments, though residence time had no major effect. According to Tukey’s test, T1 and T3 formed a homogeneous group, indicating similar depolymerization behavior.

Overall, the addition of citric acid increased process severity, accelerating xylose release and hemicellulose breakdown. Comparable patterns have been observed in beech wood and pineapple residues under hydrothermal conditions [21,22]. However, when the severity exceeds log R0 > 4, the values promote the progressive depolymerization of XOS into xylose monomers through enhanced hydrolysis of glycosidic bonds, secondary reactions intensify, promoting the formation of furfural and organic acids that reduce xylose recovery [23]. Thus, precise control of pH (~2.5–3.5) and residence time is essential to balance conversion efficiency and minimize degradation.

Figure 5B indicates that X2 production was enhanced under moderate, non-citric acidic conditions. Treatment T3 (solid-to-liquid ratio 1:10) achieved the highest X2 yield (14 g·kg−1 at 60 min), followed by T1 (9 g·kg−1 at 30 min). In T1, the staged water addition contributed to controlled depolymerization by improving mass transfer and limiting excessive severity at early reaction stages, thereby favoring xylobiose accumulation despite the absence of an added acid catalyst. In contrast, T4 (with citric acid) reached only 7 g·kg−1 at 15 min, while T2 displayed the lowest values, decreasing from 5 g·kg−1 at 30 min to 0.55 g·kg−1 at 60 min. Statistical analysis (letters above bars) shows that treatment significantly affected X2 production, though reaction time had no marked influence. According to Tukey’s test, T1, T2, and T4 formed a homogeneous group, whereas T3 differed statistically, confirming that acid-free conditions favored xylobiose accumulation. Moderate hydrothermal conditions without acid addition promote the formation of low–degree oligomers such as X2, as similarly observed in agricultural residues subjected to mild autohydrolysis [24]. This trend reflects a controlled partial hydrolysis that preserves the structural integrity of the oligosaccharides, maintaining their prebiotic potential [25]. Therefore, such conditions are advantageous for bioprocesses aimed at producing functional XOS rather than fermentable sugars.

Figure 5C shows that X3 was detected in treatments T1, T2, and T3, with concentrations below 1 g·kg−1. The highest value (0.70 g·kg−1) occurred in T3 at 45 min, followed by T1 (0.60 g·kg−1 at 60 min) and T2 (0.34 g·kg−1 at 30–45 min). Both treatment and reaction time significantly influenced X3 production (p < 0.05). Tukey’s test indicated no significant difference between T1 and T3, suggesting that both provided moderate hydrolysis conditions that favored X3 accumulation while limiting its further conversion to monomers. The detection of X3 in low concentrations supports the formation of intermediate oligomers under controlled hydrolysis conditions prior to their degradation into monosaccharides. This trend agrees with previous studies showing that X3 and X4 appear as transient intermediates during the autohydrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass [26]. Thus, kinetic control of the hydrothermal treatment plays a crucial role in modulating the molecular weight distribution of XOS, which directly determines their functional and prebiotic properties.

Figure 5D shows that X4 was detected only in treatments T1 and T2, with T1 yielding the highest concentration (3.67 g·kg−1) at 30 min, while T2 reached only 0.14 g·kg−1 at the same time. Both treatment and residence time significantly influenced X4 formation (p < 0.05). These findings indicate that high-degree oligomers such as X4 are maintained only under mild hydrothermal conditions characterized by higher dilution and the absence of acid whereas under more severe conditions (T3 and T4), they are quickly hydrolyzed into smaller XOS or monomeric xylose. This behavior confirms that long-chain oligomers are highly susceptible to degradation under harsh conditions, consistent with reports on rice straw and sugarcane bagasse, where X4–X6 are preserved only during the early stages of hydrolysis [12]. The selectivity toward longer oligomers is closely linked to temperature intensity and pH, suggesting that careful adjustment of these parameters is essential to optimize the functional value of the final XOS fraction.

Overall, the incorporation of citric acid increased process severity (logR0 ≈ 4.17), intensifying hemicellulose hydrolysis and favoring the complete conversion of polysaccharides into xylose. Conversely, variations in water availability, particularly the two-step water addition applied in T1, played a measurable role in moderating reaction severity through dilution and improved biomass hydration. This effect was later captured by the multivariate analysis, where the solid-to-liquid ratio emerged as a significant contributor to product distribution. Conversely, moderate acid-free conditions (T3) promoted the selective accumulation of low–degree XOS (X2–X3), demonstrating that reaction medium composition and residence time are key parameters to control product selectivity during hydrothermal treatment. This tunability enables the targeted production of either fermentable sugars or functional XOS from coffee pulp residues within an integrated biorefinery framework. From a broader perspective, these findings highlight hydrothermal treatment as a versatile platform within lignocellulosic biorefineries, capable of generating fermentable sugars for bioenergy applications [27] or functional oligosaccharides for the food industry and prebiotic potential of short-chain lies in their ability to selectively promote the proliferation of probiotic bacteria, notably Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species, in the human gut [28]. Moreover, the valorization of coffee by-products such as pulp, husk, and silverskin-supports circular economy strategies and strengthens sustainability in coffee-producing regions [7].

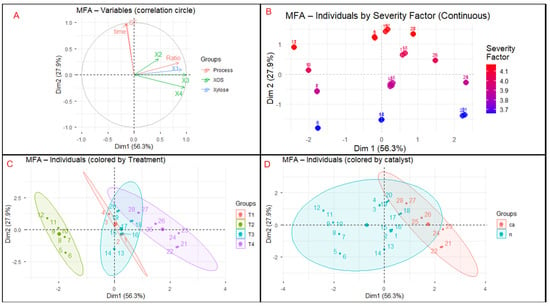

Multiple Factor Analysis (MFA) was applied to integrate and explore correlations among three variable groups: (i) process parameters (Treatment, Catalyst, Time, Ratio, and Severity Factor, SF), (ii) xylose concentration (X1), and (iii) xylooligosaccharides (XOS: X2–X4). The resulting factorial map (Figure 6) revealed two main dimensions explaining most of the total variance. Dimension 1 (58.3%) represented process intensification, characterized by longer residence times, higher severity, and citric acid catalysis—all positively correlated with xylose release. Dimension 2 (18.9%) captured variations related to the formation and stabilization of longer-chain XOS. Samples treated with citric acid (T4) clustered positively along Dim1, reflecting enhanced hydrolysis efficiency and greater xylose production, while non-acidic treatments (T3) grouped on the negative side, indicating milder depolymerization. X2–X4 loaded strongly and coherently on Dim2, evidencing their shared origin and covariance within the oligomeric fraction. This dimensional separation highlights two complementary mechanisms governing hemicellulose conversion: (i) thermal–catalytic intensification driving depolymerization toward monomeric sugars, and (ii) secondary stabilization dynamics regulating XOS production or degradation. Such behavior aligns with previous reports on hydrothermal treatment and citric-acid-assisted hydrolysis, which modulate polymer distribution within the DP 2–6 range. Overall, MFA provided an integrated multivariate framework to differentiate severity-driven xylose release from oligomer preservation, offering a robust chemometric tool to optimize hydrothermal selectivity for hemicellulose valorization in lignocellulosic biorefineries.

Figure 6.

(A) Correlation circle showing the associations between process variables (Time, Severity Factor, solid-to-liquid Ratio) and product groups (xylose and XOS). (B) Individuals plotted by Severity Factor, illustrating the gradient of hydrolysate composition along Dim1. (C) Individuals grouped by treatment (T1–T4), evidencing the influence of process intensification and citric acid addition. (D) Individuals grouped by catalyst, highlighting the separation between citric-acid-catalyzed (ca) and non-catalyzed (n) samples.

The correlation circle (Figure 6A) revealed that Time, Severity Factor (SF), and solid-to-liquid Ratio were positively associated with Dim1 and were closely associated with xylose (X1) and xylobiose (X2). This relationship indicates that prolonged residence times and higher severity levels enhance xylose release through progressive hemicellulose depolymerization. In contrast, xylotriose (X3) and xylotetraose (X4) were oriented along Dim2, suggesting that longer-chain XOS are influenced by secondary phenomena such as diffusion constraints or controlled fragmentation rather than direct thermal intensity. The clustering of X2–X4 confirms their shared origin, while the orthogonal position of X1 reflects a trade-off between oligomer preservation and monomer formation. This relationship between process variables and hydrolysate composition is consistent with kinetic models developed for hydrothermal treatment of wood and bagasse, where severity levels (logR ≈ 3.5–4.5) govern the transition from XOS to monomeric xylose [29]. The orthogonal orientation between XOS and X1 further illustrates the well-known competition between oligomer retention and their degradation to furfural under high-severity conditions [30].

Figure 6B showed a clear severity-driven gradient of individuals along Dim1, reinforcing the relationships previously observed in the correlation circle (Figure 6A). Samples processed under higher Severity Factor (SF) values clustered on the positive side of Dim1, where xylose (X1) and short-chain XOS (X2) also exhibited strong positive loadings. This spatial distribution confirms that increasing thermal intensity promotes hemicellulose depolymerization and accelerates the transition from oligomeric fractions toward monomer release, as supported by the kinetic patterns described for hydrothermal treatment of lignocellulosic biomass [29]. In contrast, samples exposed to milder conditions appeared on the negative side of Dim1, reflecting limited cleavage of hemicellulosic chains and lower solubilization of XOS and xylose. The continuous progression of points along Dim1 also mirrors the gradual shift described earlier between XOS preservation and their subsequent degradation into monomers at higher severities. This behavior aligns with the orthogonality between X1 and higher–degree XOS (X3–X4) observed in Figure 6A, where the contribution of longer-chain oligomers was predominantly captured by Dim2. Together, these findings illustrate a coordinated severity-dependent mechanism in which moderate SF values favor XOS formation, whereas more intense conditions increase monomeric xylose release. The distribution pattern in Figure 6B is therefore consistent with the known competitive pathways in hydrothermal systems, where depolymerization, diffusion constraints, and secondary fragmentation collectively define the hydrolysate composition [30].

Figure 6C revealed a clear grouping of treatments according to their level of process intensification. Treatments T3 and T4, which involved 2 solid-to-liquid ratios and citric acid addition, were positioned in the positive quadrant of Dim1, associated with greater solubilization of xylose and XOS. In contrast, T1 and T2 clustered near the origin or on the negative side of Dim1, reflecting lower hydrolysis efficiency. The compact shape of the ellipses indicated consistent behavior within each treatment, while their progressive displacement from T1 to T4 illustrated a gradual increase in process severity. This clustering pattern confirms the coherence of the experimental design and its accurate reflection in the chemometric space. Comparable trends have been reported in continuous-flow reactor studies, where temperature and residence time directly modulate the XOS/xylose ratio, enabling precise control of process selectivity [31]. Such gradual behavior supports the applicability of severity-based models as reliable predictors of hydrolysis performance and conversion efficiency.

Figure 6D revealed a clear separation between citric-acid-catalyzed (ca) and non-catalyzed (n) samples. Reactions performed with citric acid were positioned toward positive values on Dim1, associated with higher concentrations of xylose (X1) and short-chain XOS (X2–X4), indicating greater hydrolysis efficiency. In contrast, non-catalyzed treatments were projected toward the negative side of Dim1, reflecting milder depolymerization and lower product release. Citric acid acted as a weak organic catalyst that enhanced hemicellulose solubilization and accelerated hydrolysis reactions, consistent with previous observations in microwave-assisted and autohydrolysis systems, where organic acidity improved xylan conversion efficiency without compromising the structural integrity of the remaining material [21,32]. This distinction underscores the role of citric acid as a key parameter for process intensification in hydrothermal treatments.

Supplementary Figure S1 provides additional MFA outputs that reinforce the interpretation of the main results. The group representation (Figure S1A) shows that the Process group dominates the variance along Dim1, while XOS and Xylose contribute orthogonally, confirming that they describe complementary aspects of hydrolysate composition. The partial projections (Figure S1B) highlight the coordinated influence of process variables on monosaccharide and oligomer release, consistent with the patterns observed in Figure 6A–D. The variable contributions (Figure S1C) indicate that xylose and low–degree XOS are the main drivers of Dim1, supporting the interpretation of this axis as a conversion gradient shaped by severity. Finally, the time-grouped distribution (Figure S1D) illustrates the expected progression from oligomer-rich to monomer-rich profiles as reaction time increases. Together, these supplementary analyses validate the mechanistic trends identified in the main MFA without overloading the primary figures.

3.3. Membrane Concentration off the Liquid Fraction for XOS Production

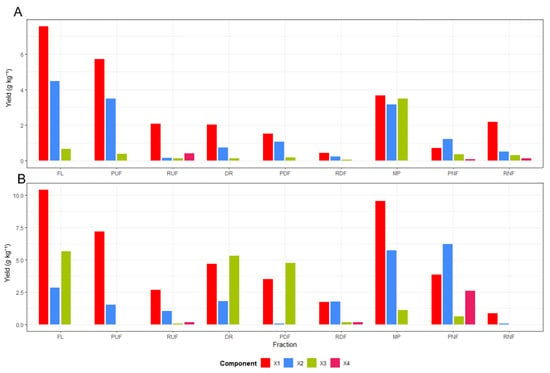

The sequential membrane system comprising ultrafiltration (UF), diafiltration (DF), and nanofiltration (NF) enabled efficient molecular-weight-based separation and enrichment of xylooligosaccharides (XOS), expressed as biomass-normalized yields (g·kg−1 dry biomass), from hydrolysates obtained in treatments T3 and T4 after 60 min of hydrothermal treatment (Figure 7). The process began with UF (10 kDa), which removed suspended solids and lignin-rich macromolecules, followed by DF, which enhanced washing and recovery of soluble carbohydrates through selective dilution with distilled water (1:1 v/v). The final NF step (150 Da) concentrated low-molecular-weight oligomers (X2–X3) in the NF retentate (RNF), yielding purified XOS fractions with reduced levels of furfural and organic acids. In the case of T3, the increase observed in the RNF fraction mainly reflects redistribution during nanofiltration rather than an actual enhancement in overall XOS recovery. The acid-assisted treatment (T4) produced higher short-chain XOS yields, with xylobiose (X2) reaching ≈2.0 g·kg−1 (dry biomass basis) in the DF retentate (RDF), while nanofiltration mainly redistributed mono- and oligosaccharides between PNF and RNF, confirming the synergistic effect of citric acid catalysis and membrane selectivity. Overall, the integrated UF–DF–NF configuration provided a selective, solvent-free strategy for purifying and concentrating XOS from lignocellulosic hydrolysates, representing an efficient approach for hemicellulose valorization within sustainable biorefinery frameworks [33,34]. Altogether, this membrane sequence demonstrated high efficiency for valorizing hemicellulose-derived hydrolysates produced by hydrothermal treatment.

Figure 7.

Distribution of xylose (X1) and xylooligosaccharides (X2–X4) across membrane fractions obtained from (A) xylose and XOS distribution in T3, (B) xylose and XOS distribution in T4. FL = feed liquid; RUF = UF retentate; PUF = UF permeate; DR = diluted UF retentate entering DF; RDF = DF retentate; PDF = DF permeate; MP = mixed permeates (PUF + PDF) fed to NF; RNF = NF retentate; PNF = NF permeate.

In treatment T3, the liquid fraction (FL) exhibited a heterogeneous composition predominantly composed of xylose (X1) and xylobiose (X2), while higher oligomers (X3 and X4) were detected only in trace amounts. During ultrafiltration (UF), most of the low–molecular–weight sugars (X1–X2) permeated through the 10 kDa membrane, confirming their small molecular size, whereas the retentate (RUF) retained a minor portion of larger XOS. The subsequent diafiltration (DF) step effectively washed and recovered soluble carbohydrates, as evidenced by the decreased X1–X2 content in the retentate (RDF) and their increased presence in the permeate (PDF).

After combining the permeates (MP) and performing nanofiltration (NF), a molecular separation was observed in T3, with xylose (X1) and xylobiose (X2) preferentially recovered in the permeate (PNF), while the retentate (RNF) contained only minor amounts of oligomeric species. This distribution indicates molecular redistribution rather than effective enrichment of xylooligosaccharides under non-acidic conditions (T3).

This fractionation behavior confirms that 10 kDa UF membranes function as an effective clarification step, allowing free passage of mono and disaccharides, whereas the 150 Da NF membrane preferentially retains oligomers with a degree of polymerization (DP ≥ 3). Similar trends were reported for rice-straw hydrolysates, where the UF–NF configuration yielded XOS fractions with purities above 77% [14]. The concentration increase observed in the RNF highlights the ability of this integrated membrane process to selectively concentrate functional XOS without chemical additives, making it highly suitable for food and biotechnological applications [35].

For the citric-acid-assisted hydrolysate (T4), a markedly different compositional behavior was observed compared to the non-acidic treatment. The liquid fraction (FL) and the UF retentate (RUF) exhibited similar proportions of xylose (X1) and xylobiose (X2), whereas the diafiltration step (PDF–RDF) substantially enhanced the recovery of medium-chain oligomers particularly in the RDF fraction, where xylobiose (X2) reached ≈2.0 g·kg−1 (dry biomass basis). This trend suggests that mild acid catalysis promoted partial and selective depolymerization of hemicellulose, generating oligomers with a degree of polymerization between 2 and 3 that were efficiently retained and concentrated during DF.

In the final nanofiltration (NF) stage, monomeric sugars were preferentially recovered in the permeate (PNF), while the RNF showed only limited retention of oligomeric species, confirming that nanofiltration mainly contributed to the separation of mono- and oligosaccharides rather than to XOS enrichment. Compared to treatment T3, T4 showed a clearer enrichment of short-chain XOS during diafiltration, highlighting the influence of citric acid on both hydrolysate composition and membrane selectivity. The presence of citric acid in T4 thus enabled a controlled hydrolysis regime, producing fractions rich in short-chain oligomers (DP 2–3) that were efficiently concentrated by DF and NF. Similar behavior has been reported in organic acid–assisted hydrolysis systems, where moderate severity levels (logR0 ≈ 4) allow the production of high-purity XOS with minimal monomer content [36,37]. The enhanced enrichment of X2–X3 in the RDF also suggests a synergistic interaction between acid catalysis and membrane selectivity, consistent with observations in sugarcane and coffee byproduct hemicelluloses [34].

The overall findings confirm that the sequential membrane process effectively fractionated the hydrolysates according to molecular weight, achieving both purification and enrichment of xylooligosaccharides (XOSs). Under non-acidic conditions (T3), the membrane system mainly promoted carbohydrate redistribution without significant XOS enrichment, whereas acid-assisted processing (T4) favored the recovery of short-chain XOS, with diafiltration identified as the key step governing XOS enrichment. These outcomes demonstrate that coupling hydrothermal treatment with membrane fractionation provides a selective, solvent-free, and environmentally benign strategy for recovering XOS from coffee pulp hydrolysates, suitable for use as prebiotic ingredients or fermentation substrates. Collectively, these results validate the efficiency of integrating hydrothermal and membrane technologies for hemicellulose valorization. This hybrid approach enables the production of high-purity XOS with proven prebiotic functionality, comparable to those obtained from other lignocellulosic sources such as rice straw and sugarcane bagasse [38]. Furthermore, the use of membrane-based separations minimizes energy demand and eliminates the need for solvents or ion-exchange resins, reinforcing its applicability within sustainable biorefinery frameworks [28]. From a broader perspective, this strategy aligns with the “hemicellulose-first” paradigm, prioritizing the selective recovery of XOS before cellulose and lignin conversion, thus maximizing the comprehensive utilization of agroindustrial coffee residues.

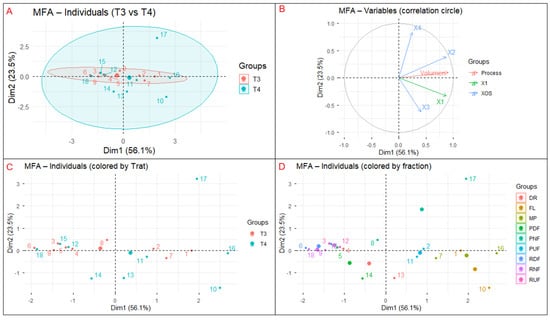

The Multiple Factor Analysis (MFA) was applied to integrate and explore global relationships among process and compositional variables derived from hydrothermal treatments T3 and T4, providing a multivariate perspective on membrane separation behavior. The analysis encompassed three variable groups: (i) process parameter (reaction volume), (ii) compositional variable (X1), and (iii) xylooligosaccharide responses (X2–X4). The first two dimensions (Dim1 = 56.1% and Dim2 = 23.5%) together explained 79.6% of the total variance, indicating a robust factorial structure that effectively captured the system’s multivariate variability. The application of MFA enabled the identification of nonlinear interrelationships between process parameters and compositional responses, overcoming the limitations of univariate analysis. This approach is particularly valuable for complex separation systems such as membrane-based processes, where hydrodynamic conditions, treatment severity, and molecular composition interact simultaneously. Recent studies highlight the relevance of multivariate techniques for optimizing hemicellulose fractionation in biorefineries, demonstrating that over 70% of process variability can be attributed to the synergistic influence of operational parameters and oligomer distribution [8,28].

The individual factor map (Figure 8A) distinguishes treatments T3 and T4, with T4 samples predominantly associated with positive Dim1 values, whereas T3 samples cluster closer to the origin or toward negative Dim1 values. This distribution indicates that acid-assisted hydrothermal treatment promotes higher solute mobilization and transport through the membrane system, while non-acidic conditions result in lower overall carbohydrate displacement. The separation between treatments reflects the influence of reaction severity on hemicellulose depolymerization and solubilization, in agreement with previous studies showing that controlled hydrothermal severity favors oligomer release prior to extensive monomer formation [39].

Figure 8.

(A) Individual factor map, (B) the correlation circle, (C) the projection of individuals by treatment, (D) the distribution of fractions.

The correlation circle (Figure 8B) shows that reaction volume and xylose (X1) are strongly aligned with Dim1, indicating that this axis primarily represents transport intensity and monosaccharide mobility within the membrane system. In contrast, xylooligosaccharides (X2–X4) load preferentially along Dim2, defining a second, independent axis associated with molecular-weight-driven fractionation. This pattern suggests that while xylose transport is governed mainly by process-related factors such as dilution and permeate flow, XOS behavior is controlled by selective retention mechanisms linked to oligomer size. Similar decoupling between monosaccharide transport and oligomer fractionation has been reported in membrane-assisted XOS purification systems [37].

The treatment projection (Figure 8C) confirms that T4 samples exhibit higher scores along both Dim1 and Dim2, reflecting enhanced carbohydrate mobilization together with improved short-chain XOS recovery. This behavior is consistent with kinetic trends observed in hydrothermal hemicellulose conversion, where moderate severity conditions favor oligomeric products over monomeric sugars [23]. In contrast, T3 samples show limited displacement along Dim2, supporting the observation that non-acidic treatment primarily induces carbohydrate redistribution rather than effective XOS enrichment.

Finally, the fraction distribution map (Figure 8D) reveals clear differentiation among membrane streams. Low–molecular–weight fractions (FL, PNF, PDF) are mainly located along Dim1, reflecting transport-dominated behavior, whereas retentate fractions (RUF, RDF, RNF) tend to project toward positive Dim2 values, consistent with molecular-weight-dependent retention. Notably, RDF samples are more strongly associated with Dim2 than RNF, indicating that diafiltration plays a more relevant role than nanofiltration in XOS enrichment under the conditions evaluated. This separation reflects classical membrane sieving effects and is consistent with ultrafiltration studies of hemicellulose-derived oligosaccharides, where chain length governs retention and permeation behavior [34].

Supplementary Figure S2 provides additional insight into the mechanistic interpretation of the MFA results. The partial individual projections (Figure S2A) show that process variables primarily drive xylose-related displacement, while XOS variables follow a distinct trajectory dominated by Dim2. The contribution map (Figure S2B) confirms that Dim1 is mainly driven by reaction volume and X1, whereas Dim2 is dominated by XOS variables, particularly X3 and X4, highlighting the role of molecular size in governing separation behavior. The group representation (Figure S2C) illustrates the near-orthogonality between Process, X1, and XOS groups, reinforcing that membrane performance is governed by two complementary but largely independent mechanisms.

Overall, the MFA indicates that membrane performance is driven by two principal axes: a transport-related axis (Dim1) associated with reaction volume and xylose mobility, and a molecular-weight axis (Dim2) governing selective XOS fractionation. These trends confirm that hydrothermal treatment coupled with membrane separation enables effective molecular differentiation of hemicellulose-derived streams, supporting the design of integrated, hemicellulose-first biorefinery processes [10].

4. Conclusions

The integration of hydrothermal treatment and membrane filtration proved effective for valorizing wet coffee pulp residues into xylooligosaccharides (XOS). Under citric-acid-assisted conditions (T4), increased reaction severity promoted hemicellulose solubilization and xylose formation, reaching a maximum yield of approximately 16 g·kg−1 dry biomass, whereas moderate non-acidic conditions (T3) favored the preservation and recovery of functional short-chain oligomers (X2–X3). In this case, cumulative biomass-normalized yields of up to 14 g·kg−1 for xylobiose (X2) and 9 g·kg−1 for xylotriose (X3) were achieved across the membrane sequence, directly supporting the selective XOS production pathway identified.

Membrane fractionation (UF–DF–NF) enabled effective molecular-weight-based separation of hydrothermal hydrolysates, with contrasting behaviors between treatments. Under non-acidic conditions (T3), the membrane sequence mainly promoted carbohydrate redistribution, with xylose and xylobiose preferentially recovered in permeate streams and only minor XOS accumulation in retentates. In contrast, the citric-acid-assisted treatment (T4) enhanced XOS recovery, with diafiltration identified as the key enrichment step, yielding up to ~1.8 g·kg−1 of xylobiose (X2) in the DF retentate. Nanofiltration primarily acted as a polishing step, directing monomeric sugars to the permeate and refining XOS-rich fractions without substantially increasing oligomer yields. Overall, the results confirm that membrane performance is strongly governed by upstream hydrothermal severity, with DF controlling XOS enrichment and NF improving product selectivity.

Multivariate analysis further reinforced these findings. Multiple Factor Analysis (MFA) revealed two complementary process pathways: (i) a transport- and severity-driven axis (Dim1) associated with reaction intensity, dilution effects, and xylose formation, and (ii) a molecular-weight-driven axis (Dim2) governing XOS fractionation, particularly for higher-degree oligomers. This quantitative multivariate interpretation confirms the mechanistic basis underlying the observed yield distributions across membrane fractions.

From a biorefinery perspective, this study demonstrates the feasibility of a hemicellulose-first strategy, aligned with cascading biorefinery and circular bioeconomy principles. By selectively recovering prebiotic-grade XOS from hemicellulose prior to cellulose and lignin processing, the proposed hydrothermal–membrane platform provides a scalable, aqueous, and environmentally benign route that maximizes the functional and economic value of coffee agroindustrial residues while avoiding the use of organic solvents.

Finally, given the significant extractive content of coffee pulp, further characterization of these fractions including potential low-molecular-weight oligosaccharides may open additional valorization pathways and warrants future investigation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pr14010153/s1.

Author Contributions

J.V.: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation and analysis, Supervision, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. I.P.R.H.: Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing. D.L.B.: Resources, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing—review and editing. R.T.H.: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Supervision. R.C.L.B.R.: Formal analysis, Data curation, Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Programa de Proyectos de Investigación, Innovación y Desarrollo Tecnológico (PROINTEC 2021) of the Universidad Nacional de Jaén (UNJ, Peru), through the project “Production of fermented kefir with coffee husk residues enriched with xylooligosaccharides”, Execution Agreement (Resolución 004-2022-UNJ/PCO).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Authors gratefully acknowledges the coffee producers from the rural communities of Las Sidras (La Coipa, San Ignacio), El Laurel (Las Pirias), and Santa Fé (Jaén) for providing the biological material used in this research. Special thanks are also extended to the UNJ for access to the Food Technology Laboratory, the UNTRM for the Postharvest Laboratory facilities, and the UCSM for the use of the Bioprocess Laboratory.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cañas, S.; Rebollo-Hernanz, M.; Cano-Muñoz, P.; Aguilera, Y.; Benítez, V.; Braojos, C.; Gila-Díaz, A.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, P.; Cobeta, I.M.; de Pablo, Á.L.L.; et al. Critical Evaluation of Coffee Pulp as an Innovative Antioxidant Dietary Fiber Ingredient: Nutritional Value, Functional Properties, and Acute and Sub-Chronic Toxicity. Proceedings 2020, 70, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Ramírez, A.; Rebollo-Hernanz, M.; Cañas, S.; Monedero Cobeta, I.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, P.; Gila-Díaz, A.; Benítez, V.; Arribas, S.M.; Aguilera, Y.; Martín-Cabrejas, M.A. Unveiling the Nutritional Profile and Safety of Coffee Pulp as a First Step in Its Valorization Strategy. Foods 2024, 13, 3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remón, J.; Ravaglio-Pasquini, F.; Pedraza-Segura, L.; Arcelus-Arrillaga, P.; Suelves, I.; Pinilla, J.L. Caffeinating the Biofuels Market: Effect of the Processing Conditions during the Production of Biofuels and High-Value Chemicals by Hydrothermal Treatment of Residual Coffee Pulp. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 302, 127008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa Montoya, A.C.; da Silva Mazareli, R.C.; Silva, E.L.; Amâncio Varesche, M.B. Improving the hydrogen production from coffee waste through hydrothermal pretreatment, co-digestion and microbial consortium bioaugmentation. Biomass Bioenergy 2020, 137, 105551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalihah, N.; Setiawan, A.; Muhammad, M.; Riskina, S. Properties of hydrochar derived from Arabica coffee agro-industry residues under wet torrefaction method. J. Eng. Technol. Sci. 2023, 55, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronix, A.; Pezoti, O.; Souza, L.S.; Souza, I.P.A.F.; Bedin, K.C.; Souza, P.S.C.; Silva, T.L.; Melo, S.A.R.; Cazetta, A.L.; Almeida, V.C. Hydrothermal carbonization of coffee husk: Optimization of experimental parameters and adsorption of methylene blue dye. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 4841–4849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiyaso, T.; Yakul, K.; Jirarat, W.; Tapingkae, W.; Leksawasdi, N.; Rachtanapun, P. Valorization of Coffee Silverskin via Integrated Biorefinery for the Production of Bioactive Peptides and Xylooligosaccharides: Functional and Prebiotic Properties. Foods 2025, 14, 2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Tian, S.; Du, K.; Xue, X.; Gao, P.; Chen, Z. Preparation and Nutritional Properties of Xylooligosaccharide from Agricultural and Forestry Byproducts: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 977548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, C.; González, A.; Ballesteros, I.; Gullón, B.; Negro, M.J. In Vitro Assessment of the Prebiotic Potential of Xylooligosaccharides from Barley Straw. Foods 2023, 12, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manicardi, T.; Baioni e Silva, G.; Longati, A.A.; Paiva, T.D.; Souza, J.P.M.; Pádua, T.F.; Furlan, F.F.; Giordano, R.L.C.; Giordano, R.C.; Milessi, T.S. Xylooligosaccharides: A Bibliometric Analysis and Current Advances of This Bioactive Food Chemical as a Potential Product in Biorefineries’ Portfolios. Foods 2023, 12, 3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.-Y.; Xu, L.-H.; Zhang, C.; Guo, K.-N.; Yuan, T.-Q.; Wen, J.-L. A Synergistic Hydrothermal-Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES) Pretreatment for Rapid Fractionation and Targeted Valorization of Hemicelluloses and Cellulose from Poplar Wood. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 341, 125828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cao, X.; Zhang, R.; Xiao, L.; Yuan, T.; Shi, Q.; Sun, R. Evaluation of Xylooligosaccharide Production from Residual Hemicelluloses of Dissolving Pulp by Acid and Enzymatic Hydrolysis. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 35211–35217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas Vega, F.E.; Sanchez Muñoz, S.; Severo Gonçalves, I.; Terán Hilares, F.; Rocha Balbino, T.; Soares Forte, M.B.; da Silva, S.S.; dos Santos, J.C.; Terán Hilares, R. Carbohydrates Valorization of Quinoa (Chenopodium Quinoa) Stalk in Xylooligosaccharides and Carotenoids as Emergent Biomolecules. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 194, 116274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrales Centeno, A.; Sanchez Muñoz, S.; Severo Gonçalves, I.; Sanchez Vera, F.P.; Soares Forte, M.B.; da Silva, S.S.; dos Santos, J.C.; Terán Hilares, R. Valorization of Rice Husk by Hydrothermal Processing to Obtain Valuable Bioproducts: Xylooligosaccharides and Monascus Biopigment. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2023, 6, 100358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluiter, A.; Hames, B.; Ruiz, R.; Scarlata, C.; Sluiter, J.; Templeton, D.; Crocker, D. Determination of Structural Carbohydrates and Lignin in Biomass. Lab. Anal. Proced. 2008, 1617, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Menezes, E.G.T.; do Carmo, J.R.; Alves, J.G.L.F.; Menezes, A.G.T.; Guimarães, I.C.; Queiroz, F.; Pimenta, C.J. Optimization of Alkaline Pretreatment of Coffee Pulp for Production of Bioethanol. Biotechnol. Prog. 2014, 30, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussatto, S.I.; Machado, E.M.S.; Carneiro, L.M.; Teixeira, J.A. Sugars Metabolism and Ethanol Production by Different Yeast Strains from Coffee Industry Wastes Hydrolysates. Appl. Energy 2012, 92, 763–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleissner, D.; Neu, A.-K.; Mehlmann, K.; Schneider, R.; Puerta-Quintero, G.I.; Venus, J. Fermentative Lactic Acid Production from Coffee Pulp Hydrolysate Using Bacillus Coagulans at Laboratory and Pilot Scales. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 218, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chala, B.; Oechsner, H.; Latif, S.; Müller, J. Biogas Potential of Coffee Processing Waste in Ethiopia. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussatto, S.I.; Machado, E.M.S.; Martins, S.; Teixeira, J.A. Production, Composition, and Application of Coffee and Its Industrial Residues. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2011, 4, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Li, H.; Ren, J.; Deng, A.; Li, W.; Liu, C.; Sun, R. Production of Xylooligosaccharides by Microwave-Induced, Organic Acid-Catalyzed Hydrolysis of Different Xylan-Type Hemicelluloses: Optimization by Response Surface Methodology. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 157, 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, R.; Singhania, R.R.; Patel, A.K.; Chen, C.-W.; Dong, C.-D. A Circular Biorefinery Approach for the Production of Xylooligosaccharides by Using Mild Acid Hydrothermal Pretreatment of Pineapple Leaves Waste. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 388, 129767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moniz, P.; Pereira, H.; Duarte, L.C.; Carvalheiro, F. Hydrothermal Production and Gel Filtration Purification of Xylo-Oligosaccharides from Rice Straw. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 62, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcondes, W.F.; Milagres, A.M.F.; Arantes, V. Co-Production of Xylo-Oligosaccharides, Xylose and Cellulose Nanofibrils from Sugarcane Bagasse. J. Biotechnol. 2020, 321, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdi, P.; Hansawasdi, C. Assessment of the Prebiotic Potential of Oligosaccharide Mixtures from Rice Bran and Cassava Pulp. LWT- Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 63, 1288–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, T.; Biely, P.; Uhliariková, I.; Sato, N.; Makishima, S.; Mizuno, M.; Nozaki, K.; Kaneko, S.; Amano, Y. Structural Characterization of Hemicellulose Released from Corn Cob in Continuous Flow Type Hydrothermal Reactor. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2019, 127, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, C.; Dixit, P.; Momayez, F.; Jönsson, L.J. Hydrothermal pretreatment of lignocellulosic feedstocks to facilitate biochemical conversion. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 846592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsin, S.; Scherzinger, M.; Kaltschmitt, M. Energy-Related Assessment of a Hemicellulose-First Concept—Debottlenecking of a Hydrothermal Wheat Straw Biorefinery. Molecules 2025, 30, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunc, M.S.; Van Heiningen, A.R.P. Autohydrolysis of Mixed Southern Hardwoods: Effect of P-Factor. Nord. Pulp Pap. Res. J. 2009, 24, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Cui, R.; Tang, W.; Fan, B.; He, Y. Co-Producing Xylo-Oligosaccharides, 5-HMF, Furfural, Organic Acids, and Reducing Sugars from Waste Poplar Debris by Clean Hydrothermal Pretreatment. Processes 2025, 13, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makishima, S.; Mizuno, M.; Sato, N.; Shinji, K.; Suzuki, M.; Nozaki, K.; Takahashi, F.; Kanda, T.; Amano, Y. Development of Continuous Flow Type Hydrothermal Reactor for Hemicellulose Fraction Recovery from Corncob. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 2842–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebadi, S.E.; Ashaari, Z.; Jawaid, M. Optimization and Empirical Modelling of Physical properties of Hydrothermally Treated oil palm Wood in different buffered Media Using response surface methodology. BioResources 2021, 16, 2385–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitzsche, R.; Etzold, H.; Verges, M.; Gröngröft, A.; Kraume, M. Demonstration and Assessment of Purification Cascades for the Separation and Valorization of Hemicellulose from Organosolv Beechwood Hydrolyzates. Membranes 2022, 12, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Andrés, M.; Andrés-Iglesias, C.; García-Serna, J. Production of Molecular Weight Fractionated Hemicelluloses Hydrolyzates from Spent Coffee Grounds Combining Hydrothermal Extraction and a Multistep Ultrafiltration/Diafiltration. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 292, 121940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.D.; Muir, J.; Arora, A. Concentration of Xylooligosaccharides with a Low Degree of Polymerization Using Membranes and Their Effect on Bacterial Fermentation. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining 2021, 15, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, H.; Sasaki, K.; Kahar, P.; Rahmani, N.; Hermiati, E.; Yopi, Y.; Ogino, C.; Prasetya, B.; Kondo, A. High Enzymatic Recovery and Purification of Xylooligosaccharides from Empty Fruit Bunch via Nanofiltration. Processes 2020, 8, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, M.G.; Forte, M.B.S.; Franco, T.T. A Serial Membrane-Based Process for Fractionation of Xylooligosaccharides from Sugarcane Straw Hydrolysate. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 278, 119285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buruiana, C.-T.; Gómez, B.; Vizireanu, C.; Garrote, G. Manufacture and Evaluation of Xylooligosaccharides from Corn Stover as Emerging Prebiotic Candidates for Human Health. LWT 2017, 77, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.R.M.; Ávila, P.F.; Pereira, M.A.F.; Pereira, G.N.; Bordignon, S.E.; Zanella, E.; Stambuk, B.U.; de Oliveira, D.; Goldbeck, R.; Poletto, P. Hydrothermal Treatment on Depolymerization of Hemicellulose of Mango Seed Shell for the Production of Xylooligosaccharides. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 253, 117274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.