1. Introduction

Centrifugal pumps are essential components of contemporary infrastructure, utilized in various industries like chemical, pharmaceutical, metallurgical, nuclear, oil and gas operations and water supply. The cumulative installed capacity of the pump fleet is substantial, and the specific energy consumption for liquid pumping often constitutes a considerable portion of operational expenses [

1].

Current research in the field of impeller pumps is increasingly focused on optimisation and numerical analysis of pumps, which is an important area of contemporary research [

2,

3,

4]. Works like Gülich, J. F [

5] or Lobanoff, V. S. and Ross, R.R. [

6] provided comprehensive information on hydraulic design, the structure of three-dimensional flows in a pump, the problem of cavitation, vibration and noise, hydraulic forces, etc., and practically all aspects are considered in detail, in order to obtain meaningful results in such problems as increasing energy efficiency, at the moment only the application of Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations and complex optimisation methods can make a significant difference [

4,

7,

8,

9,

10].

The extensive list of tasks and approaches to solving them represents a significant field of activity for researchers in this area. González, J. et al.’s work [

11,

12] presents an analysis of the interaction between the impeller and the pump casing. Murovec, J et al. [

13] present the impact of this issue on the acoustic aspect. Arocena, V. and Danao, L. [

14] present an analysis of the impact of pulsation in pumps and methods for predicting cavitation.

The modern approach to optimising pumping equipment covers a broader spectrum than simply ensuring energy efficiency at a single stationary point. Operating conditions are such that pump units often function in modes that differ significantly from the point of maximum efficiency (BEP). Operation outside the design parameters inevitably leads to the occurrence of unsteady hydraulic phenomena, including reverse flows, vortex formation in the inter-blade channels, and cavitation [

14,

15,

16]. These processes have a negative impact on the integral characteristics of the pump and become a source of intense pressure pulsations, which leads to increased vibration and accelerated fatigue wear of the structure.

It should be noted that the geometry of the hydraulic components of pumps, including the impeller, involves many interrelated variables, such as blade angles β and meridional section profiles, where a change in one parameter leads to a nonlinear response of the entire system. Given the complex hydrodynamic conditions, traditional design methodologies, based on empirical dependencies [

5,

6] and sequential physical prototyping, lose their effectiveness due to the high labour intensity and duration of development cycles.

Thus, adequate analysis and design of modern flow parts become impossible without the use of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) tools. However, the direct sequential application of CFD simulation for iterative optimisation is also associated with significant computational costs due to the complexity of achieving optimal geometric parameters. Thus, this method actually reduces research time by shortening the physical testing stage of the prototypes obtained, but it is still inferior to the use of stochastic search algorithms.

To solve this problem, the method of surrogate modelling is actively used. Methods, response surface methodology (RSM) [

17,

18,

19], Kriging [

20,

21], the use of artificial neural networks (ANN) [

22] or optimisation using stochastic evolutionary algorithms such as NSGA-II or NSGA-III [

23,

24,

25,

26] significantly speed up the optimisation process and allow the optimal solution to be found within a reasonable time frame. This study also uses a surrogate metamodel based on the application of an evolutionary algorithm.

The main difference between this work and others is its focus on adapting the results obtained using the RSM method and EA to the specifics of centrifugal sealed pumps, as a result of the introduction of FSI simulation combined with tests of the physical prototype of the impeller on a hermetic centrifugal canned motor pump.

Fluid–structure interaction (FSI) modelling methods are used to assess the structural integrity of impellers during operation [

27,

28,

29]. Due to the fact that the impeller blades are subjected to complex, often unsteady, hydrodynamic loads, including pressure pulsations from rotor-stator interaction and cavitation phenomena, the resulting loads cause deformations and vibrations that can lead to a reduction in fatigue strength and, in the worst case, to resonance vibrations and failure. FSI analysis allows for an adequate assessment of the stress–strain state of the blades under real flow conditions and identification of stress concentration zones.

The impeller is the most important element in the design of centrifugal pumps, significantly affecting the overall efficiency of the system, which makes solving this problem extremely important for their manufacturers. The complex interaction of design parameters and computational costs makes it difficult to optimise the impellers of centrifugal pumps. The complex interaction of design parameters and computational costs makes it difficult to optimise centrifugal pump impellers [

1,

30].

This study is carried out with the aim of obtaining a fast and reliable model for the design and optimisation of impellers for a hermetic centrifugal pump of monoblock configuration, equipped with a canned asynchronous electric motor. This design ensures complete sealing, i.e., zero fugitive emissions, by eliminating dynamic shaft seals and combining the pump and motor into a single sealed unit. The stator and rotor are separated by thin-walled, non-magnetic, sealing sleeves. The pump rotor moves inside the sleeved stator, which allows the pumped medium to remove heat from the rotor and lubricate the internal hydrodynamic ceramic slide bearings.

The parameters of the pump under study are presented in

Table 1. The selected operating parameters were chosen due to the reduced size of the resulting pump impeller. In turn, the rotation speed of n = 2950 min

−1 is a limitation of the selected canned electric motor.

Analysing, in a preliminary approach, the relationship between the operating characteristics of the pump and its geometric parameters, we can note that the pump under study, with a speed ratio of n

q = 13 (Equation (1)), can be classified as a

low specific speed centrifugal pump with purely radial flow. Pumps of this class are designed to create high pressures at relatively low flow rates. Consequently, geometrically, an impeller with such specific speed values will have a large ratio of the outer diameter to the inlet diameter (D

2/D

1) and narrow blade channels b

2, which allow for the efficient conversion of kinetic into potential energy.

The aim of this work is to develop a fast and cost-effective methodology for designing impellers for centrifugal pumps for use in sealed monoblock centrifugal pumps. To solve this problem, this study uses a combined methodology linking CFD simulations, Response Surface Modelling (RSM) analysis in combination with Evolutionary Algorithms (EA) as an optimisation algorithm, as well as the use of Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) technology for prototyping the resulting pump impeller and applying it to a sealed monoblock centrifugal pump during bench testing. PA-12 was selected as the material for manufacturing the experimental model due to its high structural integrity and isotropic mechanical properties. According to the literature [

31], the tensile strength of sintered PA-12 varies between 45 and 50 MPa, which is consistent with the specifications of the PA-12 Industrial material used (48.7 MPa) [

32]. Critically important advantages of this polymer are its high impact strength and plastic deformation capacity. These qualities ensure the stability of the structure against pulsating loads arising from the hydrodynamic interaction of the rotor and stator. This choice favourably distinguishes PA-12 from materials for extrusion printing (such as ABS and PETG), which are characterised by pronounced anisotropy depending on the direction of layer deposition.

The novelty of the research consists of the applied engineering adaptation of the metamodel for optimising impellers for centrifugal hermetic monoblock pumps with canned motors. This methodology integrates CFD modelling, RSM and evolutionary algorithms, adapted to take into account the strict design constraints of centrifugal pumps with canned motors. Unlike general research in the field of optimisation, this study shifts the focus from algorithm development to the comprehensive adaptation of the resulting methodology to the specifics of this type of pump. A key distinguishing feature of the proposed methodology is the mandatory integration of fluid–structure interaction (FSI) analysis, given the use of additive technologies at the physical prototyping stage. Such close attention to this topic is necessary to prevent deformation of the impeller parts, to protect other parts of the pump, such as graphite plain bearings, from deformation or damage, and to prevent the pump rotor from jamming, to which this type of pump is much more prone than classic console pumps. A prototype impeller made from Pa-12 Industrial using SLS technology was tested for strength and stiffness, and functional testing of the pump with this prototype was also carried out. The study also identified the limits of PA-12 polymer applicability in hydraulic systems, providing practical recommendations for the design of a new generation of hermetic pump units. FSI data analysis was also performed on several other PA-12 centrifugal pump impellers to identify some limitations on the applicability of this material. The results provide practical recommendations for design engineers and will be used in the design of impellers for hermetical centrifugal pumps.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Optimisation Process Scheme

The process of optimising the hydrodynamic characteristics of centrifugal pump impellers is a rather complex, multi-parameter task that is costly in terms of computing resources. Direct optimisation, which directly links the search algorithm with the CFD solver, is inefficient due to excessive time costs and is not suitable for a large number of parameters. The optimisation process presented in the diagram combines CFD with optimisation methods, as described in detail below. The goal of optimisation is to increase the hydraulic efficiency of the impeller while maintaining its specified head of H = 20 mH

2O as a constraint. In turn, the geometric parameters of the impeller describing the shape of its meridional section, as well as its blades, were selected as optimisation parameters (described in more detail in

Section 2.3). The corresponding geometric design parameters were set in accordance with the technical requirements of the project.

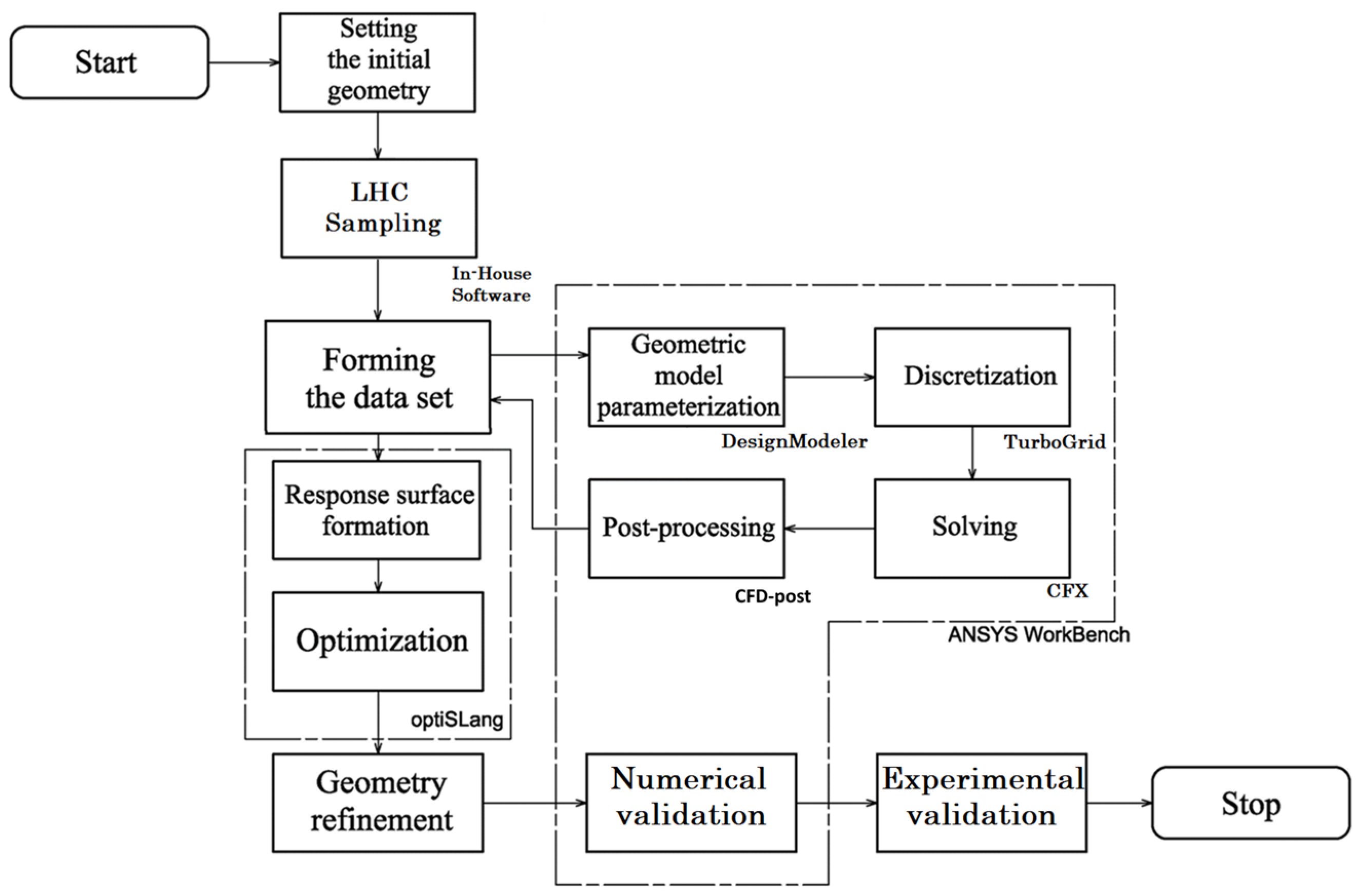

The optimisation cycle applied (

Figure 1) is almost completely integrated within the ANSYS Workbench 2024 R2 platform (Ansys, Inc., Canonsburg, PA, USA) (using optiSLang 2024 R2 as the optimiser program) and includes a series of sequential, interrelated steps covering digital validation of the initial model, geometric model parameterisation, Design of Experiments (DoE), RSM and the use of Evolutionary search Algorithms as the optimisation algorithm.

The primary task was to establish a reference point, i.e., a baseline design, which allowed us to obtain a preliminary assessment of the main geometric parameters of a centrifugal pump impeller with similar initial characteristics, and was also used for subsequent comparative analysis and evaluation of the effectiveness of optimisation procedures. The initial geometry was obtained based on an empirical model and represents a classic 6-blade impeller (detailed in

Section 2.3.3).

The next critical step was to develop a parametric model of the impeller, defining the space of design parameters for optimisation. Eleven key geometric characteristics were selected as variable (input) parameters, comprehensively describing the shape of the meridional section and the flow part of the blade: d- leading edge diameter (LE diameter), D2 outer diameter of the impeller, b2 width of the outlet blade, α angle between the hub and shroud at the blade outlet, β1, β2 and β3 blade angles, M2 location of the midpoint of blade curvature as a percentage of its length, i.e., analogue of θ, RH hub radius, RS shroud radius and z number of blades.

Then, the DoE methodology was applied using the Latin hypercube (LHS) technique to systematically investigate the design space and create a data set of various possible impeller designs. In-house software was used for better sampling because standard implementations of this method, integrated into commercial software packages, often impose significant limitations. For each geometry in the data set, CFD simulations were performed to evaluate the fluid flow and determine the corresponding criterion values. The settings of the modules used for simulation, namely: DesignModeler for model geometry generation, TurboGrid for its discretisation, CFX for the calculator program, and CFD-post for the post-processing module, which work in an optimisation cycle to ensure the formation of the dataset, are presented in

Section 2.2.

Based on the simulation results, an RSM was developed to determine the relationship between geometric parameters and criterion values. It allows for a quantitative assessment of the relationships between factors (geometric parameters of the impeller) and response (optimisation criteria), constructing a response surface based on data obtained from DoE planned experiments. The resulting surface allowed the optimisation algorithm to effectively determine the geometry that minimised the selected objective function (impeller torque). The next stage of the approach involved validating the optimised impeller design using URANS (Unsteady Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes) CFD simulations, taking into account the complete geometry of the pump section, namely the suction pipe, the pump impeller itself and its casing, to confirm the applicability of the solution in real operating conditions.

In parallel with the construction of the RSM, an in-depth sensitivity analysis was performed to understand the relationships within the system. A correlation matrix was constructed, which was used to quantitatively assess the linear relationships between all pairs of variables (input and output). In addition, a Coefficient of Performance (COP) matrix was obtained. This analysis made it possible to identify the most and least significant geometric parameters and compare them with well-known statistical data.

A prototype pump impeller was manufactured using additive manufacturing (AM), namely Selective Laser Sintering (SLS), for rapid experimental validation of the obtained results.

Experimental validation of the impeller optimisation methodology was carried out by bench testing on a CH series centrifugal sealed monoblock pump. The tests of the optimised pump impeller were carried out in full compliance with the requirements of ISO 9906:2012 [

33].

2.2. Setting up CFD Simulations Applied During the Optimisation Process

2.2.1. Initial Design and Geometric Model

The initial geometry of the impeller was taken as the initial model, which is a geometric model of a centrifugal pump impeller obtained by applying an empirical model [

34]. The geometric model for the subsequent optimisation cycle was constructed using the ANSYS DesignModeler design environment integrated into the Workbench platform.

To obtain a parameterised model of the blades, ANSYS BladeEditor tools were used, which represent the integration of the tools presented in the ANSYS BladeModeler module, which in turn provides the ability to fully control the variation in the blade shape by changing the blade angles

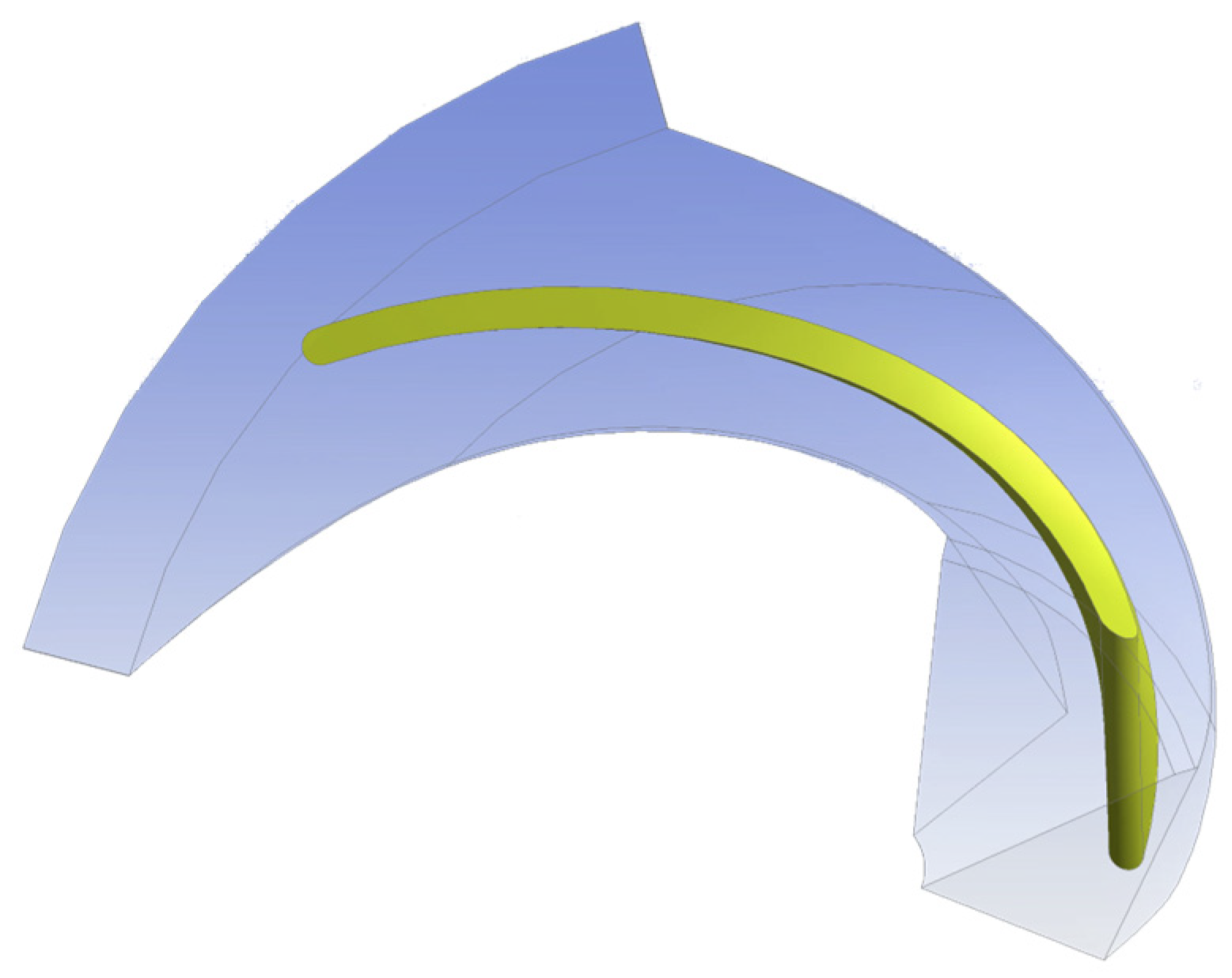

β, wrap angles θ, etc. The pump impeller parametrised model used in this study is shown in

Figure 2.

The blade geometry was parameterised at 3 points (n1 ... n3) by changing the blade angle β (β1, β2, β3). Since the position of point n1 is determined by the position of diameter d describing the location of the leading edge, and the position of point n3 is determined by the diameter D2 of the impeller, only the position of point n2 is a free parameter transmitted via angular coordinates. The blade geometry was described by keeping the blade thickness distribution constant along the entire blade length, identical to the distribution of the original pump impeller, and was not presented as an optimisation parameter.

In order to minimise the computational resources consumed, the geometric model was created for a single blade. Although the blade angle/pitch angle distribution function β/θ remained the same, the addition of additional sections (layers) describing the flow part allowed for a smooth construction of the blade surface from layer to layer, including the blade inlet surface.

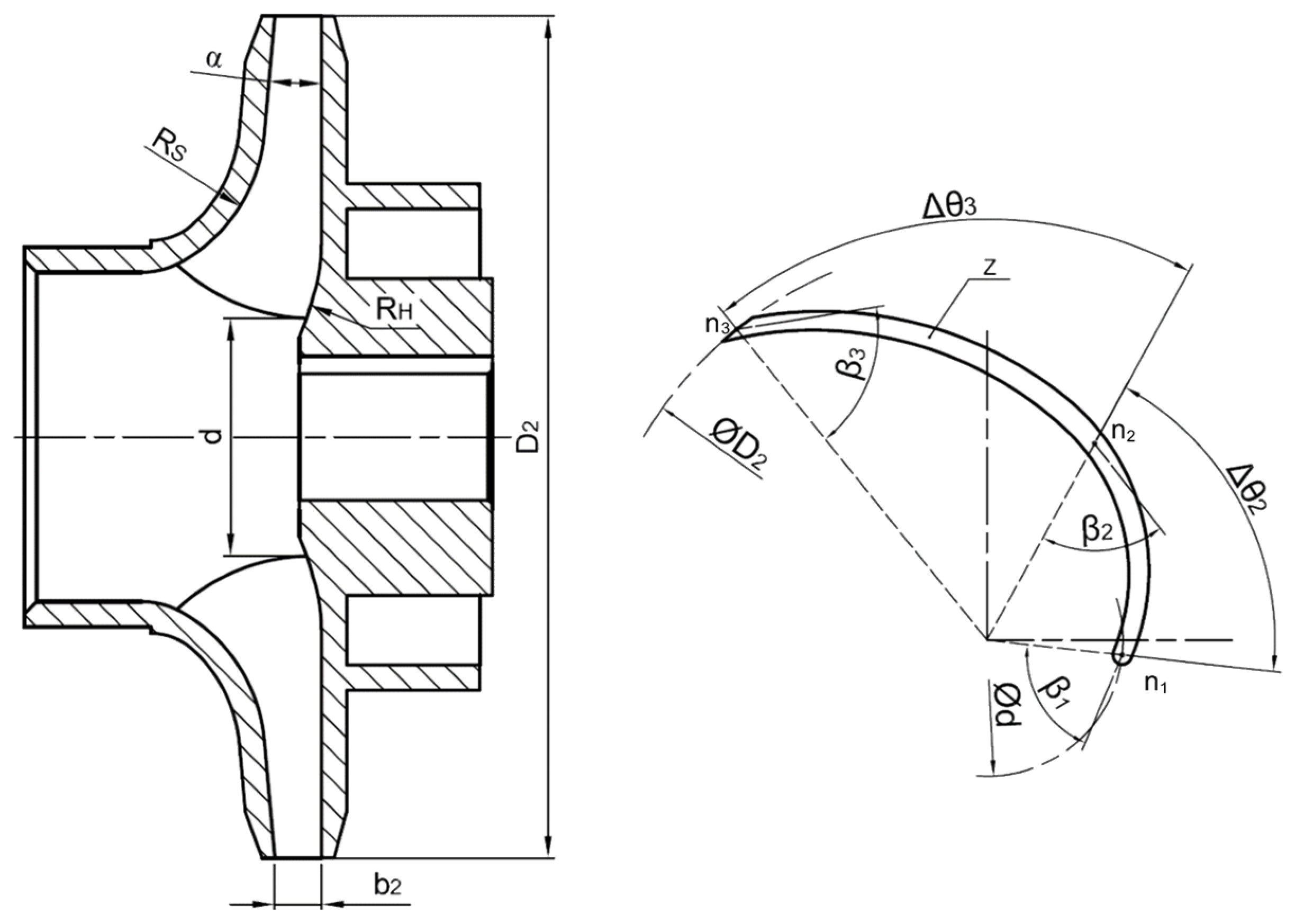

The diameter of the impeller throat was not considered as an optimisation parameter, as we are strictly bound to the diameter of the suction pipe. The angle of inclination α and the radius of the shroud Rs of the ring were selected as the geometric parameters describing the shroud of the impeller. The surface of the hub is described by the radius R

H, and the distance between the hub and the shroud is described by the width of the impeller outlet channel b

2. The pump impeller’s parameterisation scheme used in this study is shown in

Figure 3.

2.2.2. Discretisation of the Geometric Model

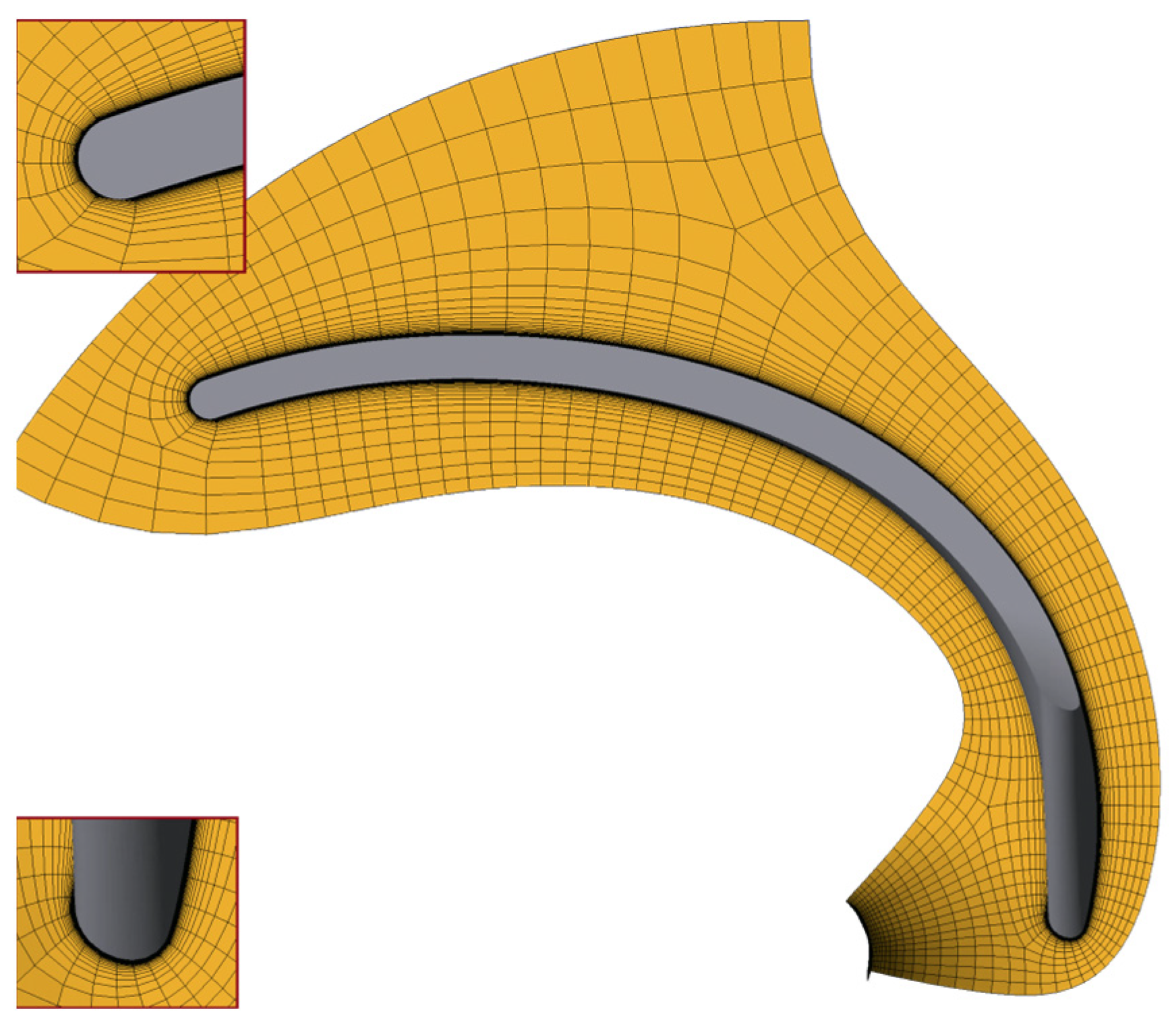

ANSYS TurboGrid was selected for the discretisation of the geometric model of the impeller. TurboGrid is designed to generate high-quality, structured hexahedral meshes for the analysis of the flow part of turbomachines and, unlike ANSYS ICEM, allows this to be done automatically, without human intervention to rebuild the topology, which was a key factor in choosing this ANSYS module for selecting it as the discretisation module for configuring the optimisation process with multiple iterations.

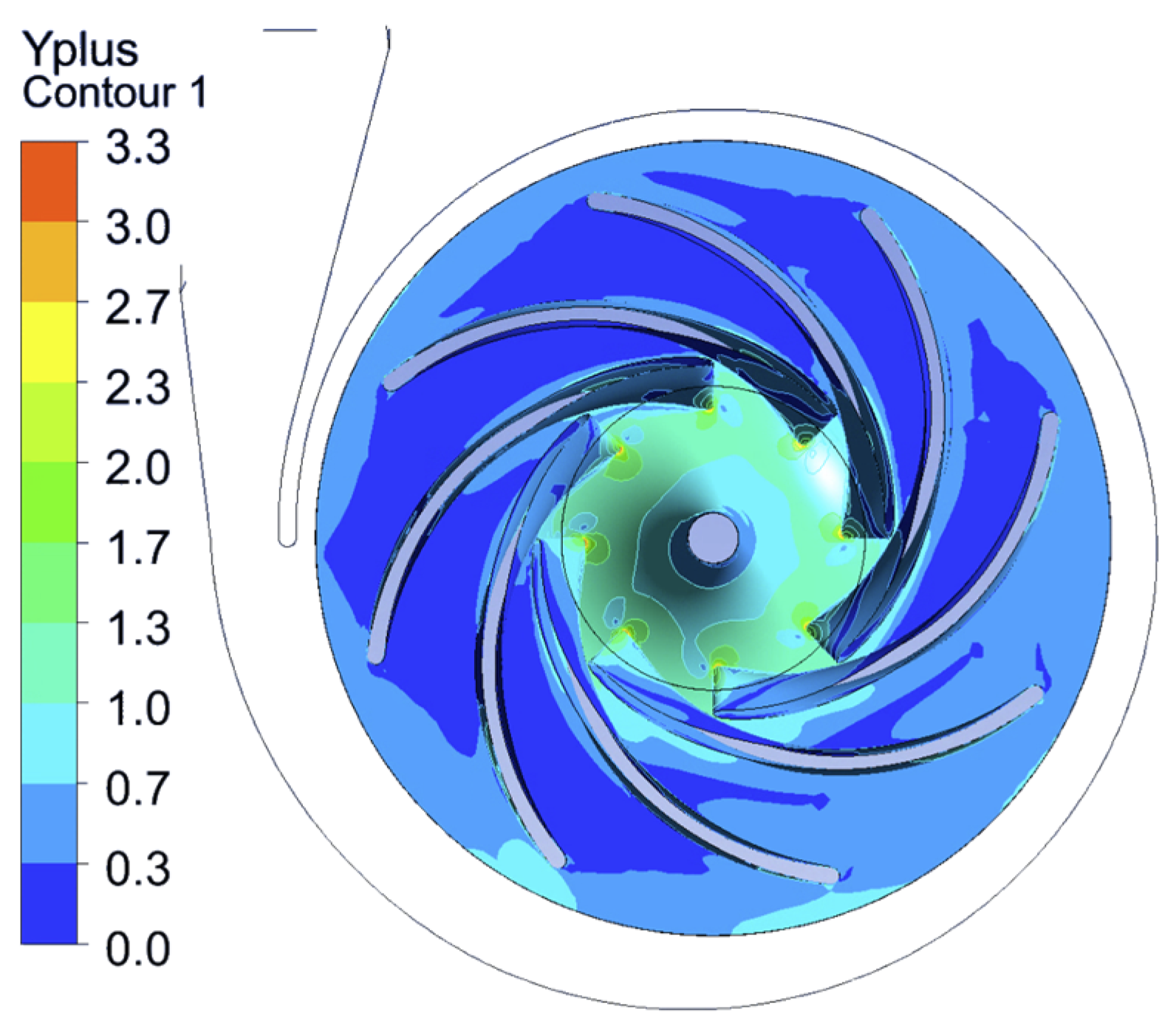

The figure below (

Figure 4) shows a cross-section of the grid created in ANSYS TurboGrid. The desired parameter y

+ = 1 was used as a metric to describe the mesh density, with an expected Reynolds number of the fluid flow in the pump equal to Re = 1·10

6. Based on this parameter, the TurboGrid algorithms control the mesh density in the boundary layer on the surface of the blades. The Hub and Shroud surfaces were described in a similar way, and the Element count and size method was used to specify the mesh density in the meridian section, with a specified mesh density of 52 elements with 8 elements of constant size. The proprietary ATM topology single-round symmetric was used as the Topology Set, as it was most suitable for this blade shape.

2.2.3. Initial and Boundary Conditions

An INLET boundary type was set at the entrance to the calculation domain, with the direction of fluid flow normal to the boundary plane. A total pressure of Pinlet = 9806 Pa or 10 mH2O was specified at the entrance to the domain, with a low initial degree of turbulence. The reference pressure in this series of simulations is zero.

An OUTLET boundary type was specified at the outlet of the calculation domain. A mass flow rate corresponding to the nominal flow rate was applied at the inlet to the domain, namely Qoutlet = 1.75 kg/s/n, where n is the blade number in this particular calculation. The turbulence characteristics at the outlet of the calculation domain are calculated by the Zero Gradient model.

A rotation speed of 2950 min−1 is also applied to the calculated domain. The simulation was performed using an isothermal flow model at a temperature of 25 °C. The simulations use a single-phase fluid model, water at 25 °C. It was decided not to simulate the cavitation process in this series of calculations, as this significantly increased the calculation time and the computer resources required for the calculation.

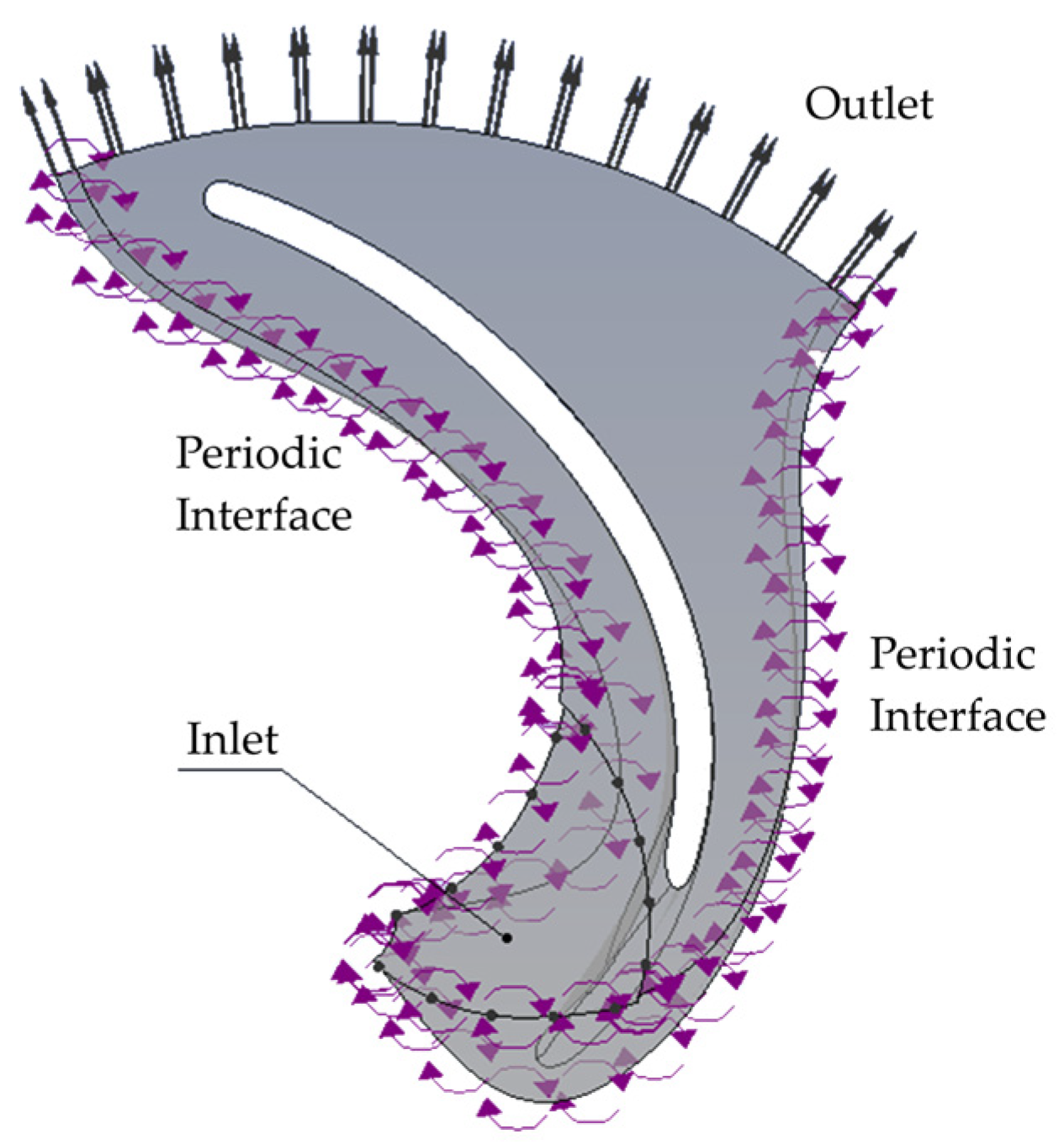

For the boundary conditions of the Wall area, the “No Slip” specification is applied, i.e., flow without slippage (and in this case without taking into account the roughness of the wall surfaces), i.e., the velocity in the immediate vicinity of the wall tends to zero, which facilitates the simulation of wall phenomena in accordance with Boundary layer flow. A periodic rotation interface (Periodic Interface) (

Figure 5) was applied to the boundary surfaces of the calculation domain to reduce calculation time and computer resources.

As for the calculation parameters, due to limited resources, a steady-state calculation was used, which represents the desired turbulent flow fields by averaging over time. The Physical Timescale option was selected as the time discretisation parameter. Since the main movement studied in this simulation is the rotation of the impeller, the Physical Timescale option was set to 1/ω = 0.0032 s, where ω is the angular frequency.

It should be noted that the simulation of the fluid flow inside the pump to obtain realistic numerical results is based on an appropriately selected mathematical model of turbulence. One of the main problems in fluid flow modelling is significant fluctuations in the flow field in time and space [

35], which can have a significant impact on the flow pattern. Turbulence occurs when the inertial forces of a fluid become significant compared to its viscous forces and is characterised by a Reynolds number reaching 10

6 [

5].

Given that a steady-state model was used in these series of simulations, a turbulence model based on RANS (Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes) equations was selected, which uses a statistical averaging process. This process is used to obtain equations that significantly reduce the computational resources used. This study uses the RANS SST (Menter’s Shear Stress Transport) turbulence model [

36]:

where:

xj represents the partial spatial coordinates, with the subscript

j indicating the spatial directions (x, y, z),

uj denotes the mean flow velocity components in the

j-direction,

k is the turbulent kinetic energy,

ω represents the specific dissipation rate,

μ is the dynamic viscosity,

νt is the turbulent kinematic viscosity,

μt is the turbulent (eddy) viscosity,

ρ is the fluid density and

P—the turbulence production term.

The SST model provides a higher accuracy compared to other models, especially in flows with unfavourable pressure gradients and separation. This advantage is due to the model’s ability to improve predictions of turbulent shear stress in areas characterized by high shear and unfavourable pressure gradients. The advantage of the SST model over other models based on RANS equations is that the hybrid model combines the k-ε and k-ω models, allowing the advantages of both models to be exploited and providing a high accuracy for flows with unfavourable pressure gradients and separation [

37]. The use of the SST model improves the prediction of turbulent shear stress in areas with high shear and unfavourable pressure gradients [

38]. The model combines the advantages of the k-ε (free fluid flow description) and k-ω (boundary layer flow description) models [

34].

2.2.4. Processing and Post-Processing

To improve the efficiency of calculations, ensuring numerical convergence with reduced execution time, the following criteria were selected: a finite number of 500 calculation iterations, or stopping the calculation when the tolerance for the root mean square error of the residual 10

−5 is reached. A series of simulations was performed with impellers with different sets of geometric parameters, which showed that the criteria presented were sufficient for convergence. Below is an example of the distribution of the y+ field (

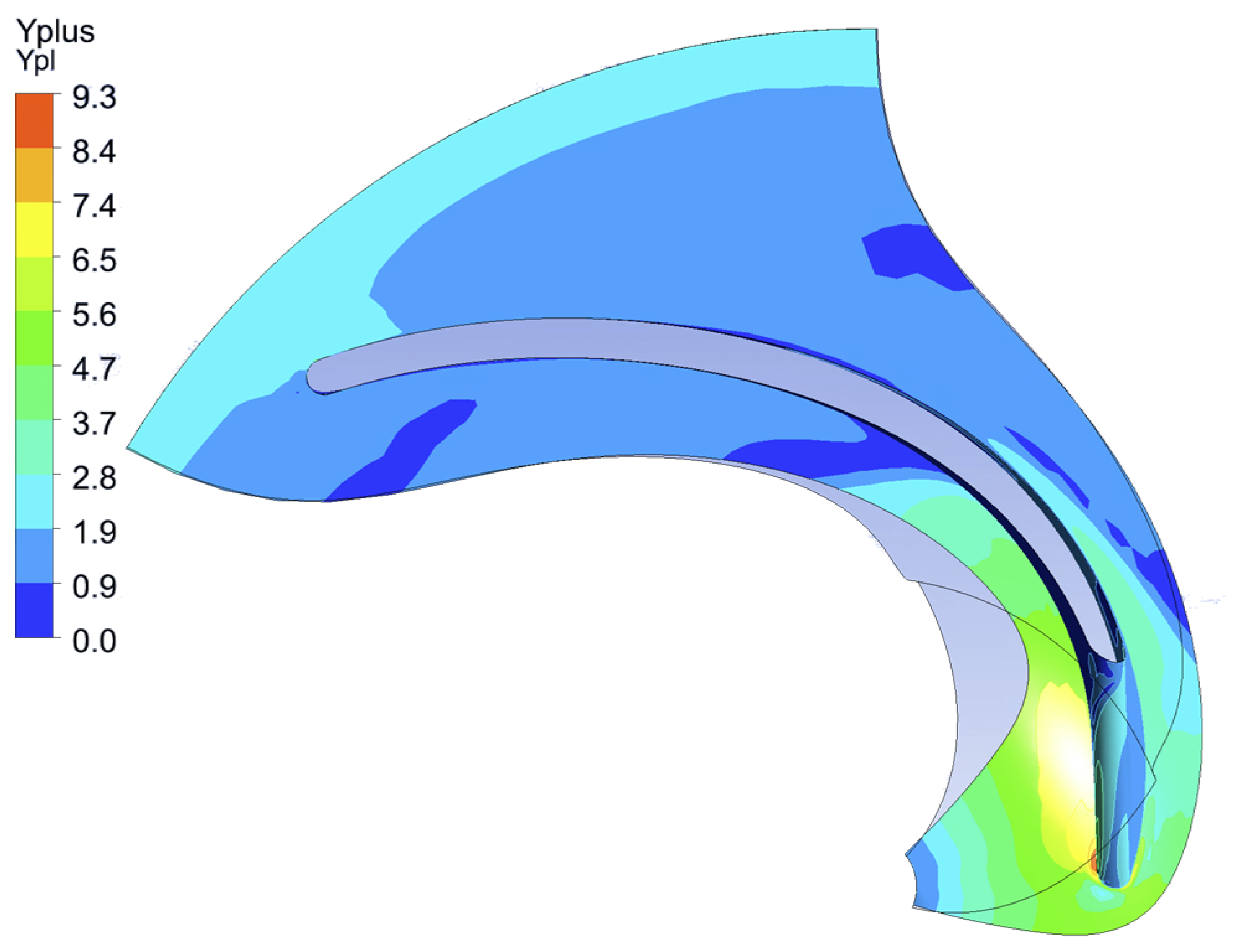

Figure 6) obtained during the simulation of one of the geometries. After performing the calculation, the system presents the pressure at the impeller outlet and its torque relative to the Z axis of rotation as the values of the optimisation criteria.

2.3. Applying the Optimisation Process

2.3.1. Parameters Sampling and Dataset Formation

The limits of parameter variation are presented in

Table 2. Regarding the limits of parameter variation, they were selected based on two approaches:

- -

Firstly, based on the available geometric dimensions of the existing pump, such as the shaft diameter or pump casing dimensions, here we may refer to parameters such as d hub diameter, Rh hub radius or maximal impeller diameter D2.

- -

Secondly, based on a preliminary analysis of the model conducted to identify the limits allowing robust application of the model, in this case we are talking about parameters such as blade angles β.

Parameters were sampled within the established limits using the Latin hypercube method. This method was chosen because of its high efficiency compared to the basic Monte Carlo method, since the LHS method contributes to a more uniform and stratified study of the parameter space, thereby maximising the amount of information obtained about the behaviour of the system with a minimum number of necessary simulations.

Sampling is necessary to obtain random combinations of parameter values. A total of 1500 design points were obtained, with 250 parameter combinations for each blade number (from 3 to 8). As a result of parameterisation based on these parameter combinations, 853 successful geometries were created, which were subjected to CFD modelling and subsequently optimised. In order to increase the obtaining results speed and to save computer resources, it was decided to perform calculations only at Qnom flowrate, since verifying the methodology for obtaining the highest efficiency at the Qnom flowrate point was the main objective of the study.

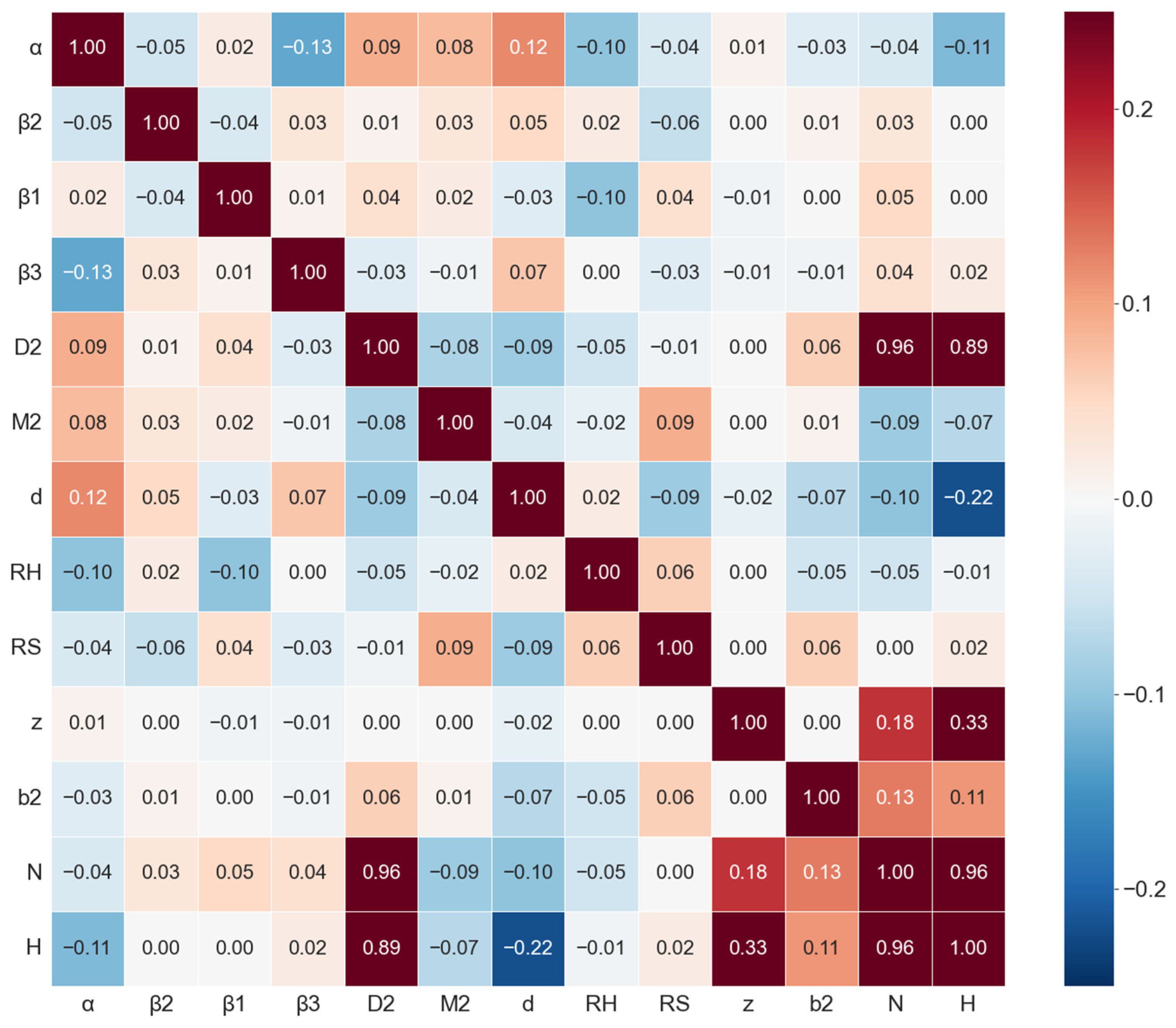

Below is a statistical analysis of the correlation matrix based on a dataset representing data consisting of parameters obtained by sampling using the LHC method and the output values of criteria obtained as a result of numerical CFD modelling of a parametric model of a centrifugal pump impeller.

The purpose of the analysis is to determine and quantitatively assess the degree of influence of 11 basic geometric parameters on two criteria for optimising the output characteristics of the impeller’s torque and its head.

A systematic study of Pearson’s correlation matrix clarifies the hierarchy of influence of geometric factors on the hydraulic and energy characteristics of the pump. This figure shows Pearson’s correlation coefficient r, which is a statistical tool that analyses the strength and direction of the linear relationship between two variables. The value of r can vary from −1 (perfect negative correlation) to +1 (perfect positive correlation). If the value of r is zero, it means that there is no dependency. This analysis focuses on two end results, impeller torque N and pump head H, as target optimisation functions and constraints.

The data array presented in

Figure 7 was obtained as a result of multi-parameter analysis in the Ansys optiSLang software package. The software calculated the values of Pearson’s correlation coefficient for the variables presented, followed by exporting the resulting matrix. For effective visualisation of the identified correlations, the results were processed using the specialised Seaborn v.0.13.2 (Python v.3.14) library, which allowed them to be presented in the form of a heat map for clear identification of the most significant influencing parameters.

Correlation analysis of head H reveals several influencing factors, primarily the outer diameter of the impeller D

2, which shows a very strong positive dependence on head r = 0.89, in accordance with the fundamental principles of turbomachinery (Euler’s equation), since the theoretical head Ht is directly proportional to the square of the circumferential velocity at the outlet u

2, which is linearly dependent on the impeller diameter D

2 [

5].

It can be noted that the next factor in terms of influence is the number of blades z, which has a moderate positive dependence on the pressure r = 0.33. This factor also correlates with theoretical data. The diameter LE—d also has a weak negative dependence r = −0.22, since this factor affects the shape and size of the blades, as does the width of the outlet blade b2.

An analysis of the required torque N, which is directly related to the energy consumption of the pump, showed an even clearer hierarchy. The outlet diameter D2 is the most important factor affecting the torque N, similar to the head. The correlation coefficient r = 0.96 shows a significant dependency, as it directly affects the blade’s surface area. The same logic applies to the moderate negative dependency of the diameter LE—d and the positive dependency on the height of the blade at the outlet of the impeller b2.

An important observation is the almost perfect positive correlation between pressure H and torque N, r = 0.96. This means that these two objective functions are not independent in the parameter space under consideration and that the classic optimisation problem is “minimising torque N while maintaining pressure H”.

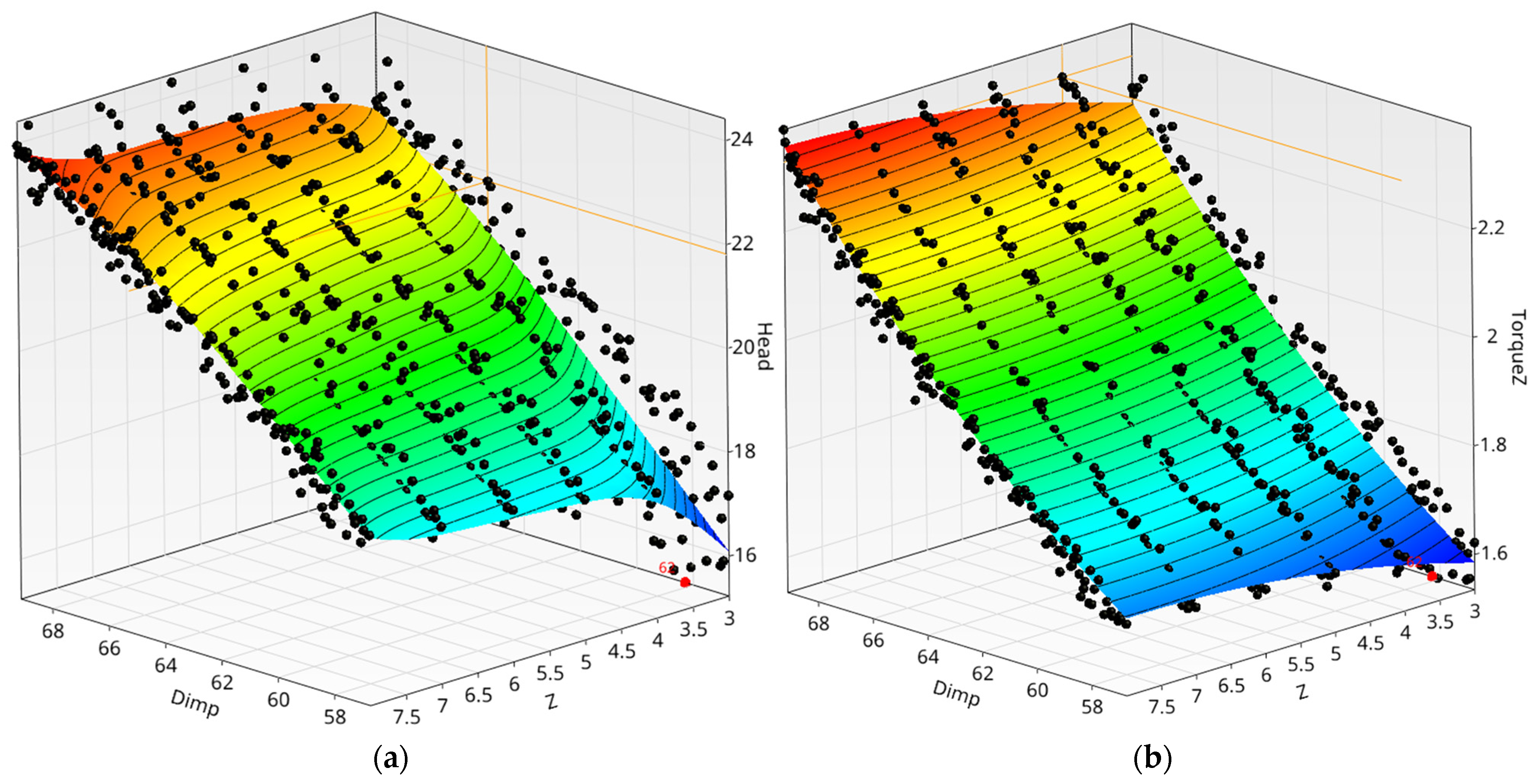

2.3.2. Response Surface Formation

When forming the response surface (

Figure 8), the anisotropic kriging method was used for the pressure task and classical kriging for the torque. The classical or isotropic kriging used for torque assumes that the correlation between points in the design space depends solely on the distance between them, but not on the direction. This method was chosen in view of the structure of the data forming the dataset.

At the same time, an improved Anisotropic Kriging method was applied to the pressure model. By automatically determining different correlation lengths, the model varies the sensitivity of the result to parameter changes.

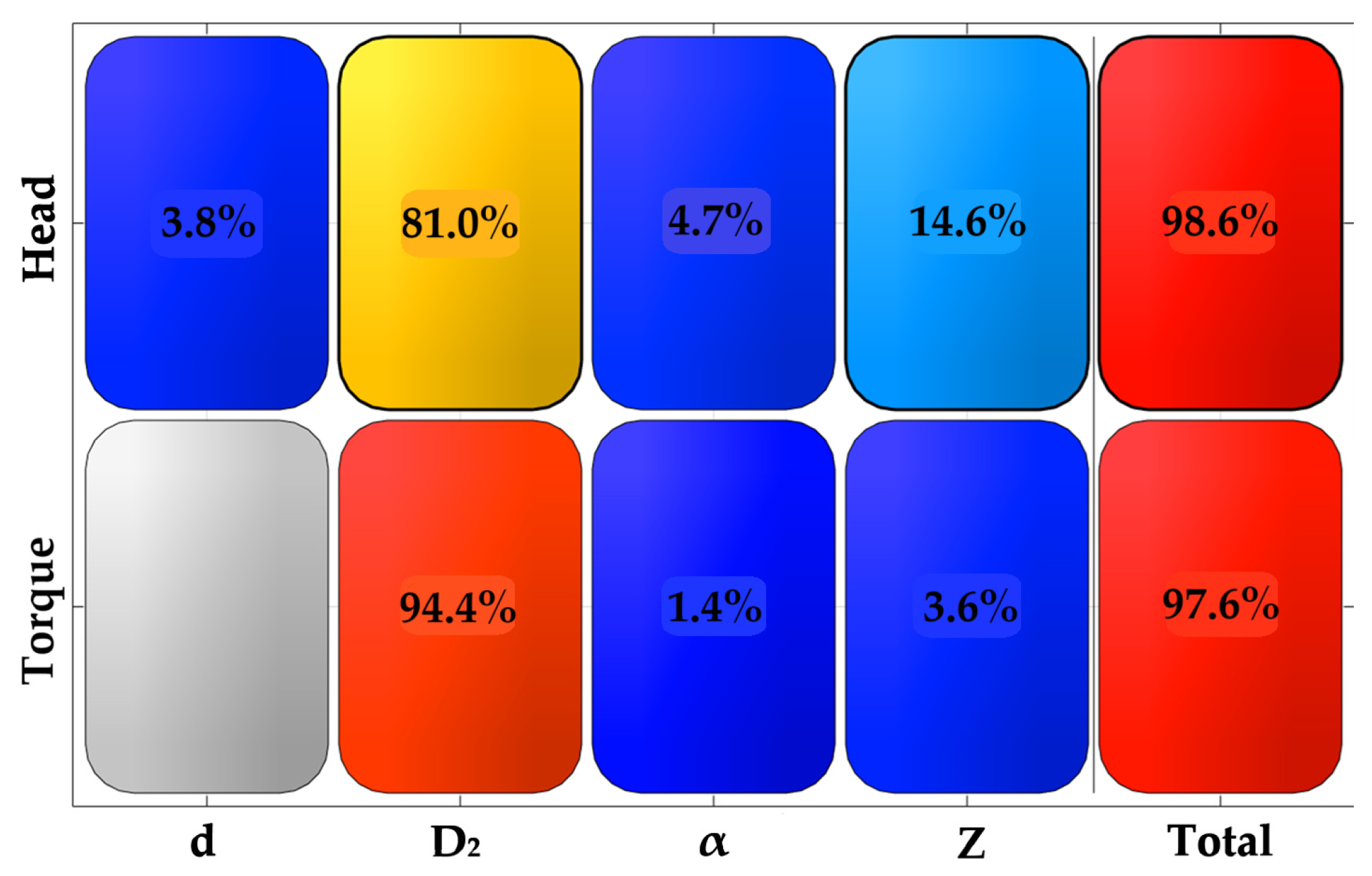

The presented correlation matrix

, which is also a coefficient of prediction (CoP) matrix (

Figure 9), shows high aggregate CoP R

2 values exceeding 97% for both functions, indicating the high predictive power of the constructed response surface. This testifies to the adequacy of the metamodel and its suitability for solving the optimisation problem. As for the values of the optimisation parameters, they correspond to the results analysed in the study of the correlation matrix.

2.3.3. Application of the Optimisation Algorithm

The optimisation strategy applied is based on EA, which was performed on the basis of a pre-constructed RSM response surface. The configuration and application of EA were implemented in the ANSYS optiSLang environment.

At the initial stage of the study, preference was given to a simpler gradient method, namely NLPQL (non-linear programming by quadratic Lagrangian); however, since a discrete parameter, namely the number of blades, was chosen as the optimisation parameter, nature-inspired optimisation methods began to be considered as the optimisation algorithm. Preference was given to the EA, which, in turn, provides a better picture in this type of optimisation, better avoids local minimum, and also works better with less influential parameters. As a result of the optimisation process, several runs of the evolutionary algorithm were performed to identify the best algorithm settings. The impact of the settings on the algorithm results was analysed by examining the convergence of the objective function.

The choice of EA parameters indicates a strategy focused on model refinement and exploitation, equally reflected in the compromise between population size and number of generations [

39]. The set population size of 16 individuals is sufficient when working with RSM, where the cost of calculations is extremely low compared to CFD calculations, allowing the algorithm to focus on a small group of elite candidates, sequentially improving them over a very large number of generations (maximum number of generations equal to 625), with a set maximum limit of 20,000 samples, which gave the algorithm complete freedom to exhaustively explore the response surface in search of a global optimum, limited only by the stagnation criterion of 20 generations, the criterion for stopping in the absence of further improvements.

The fitness evaluation mechanism was performed using a weighted sum method constrained by rank order and was supplemented by a rank order constraint. This ensures that the final optimum will lie in an acceptable, rather than simply a highly efficient region.

Selection based on linear ranking is a more stable method than selection based on raw fitness values, as it prevents premature domination by “super-individuals”. In turn, the stochastic selection method with 10 parents out of 16 individuals provides moderate selection pressure, allowing the best solutions to advance while preserving some genetic diversity. Recombination, implemented through uniform crossover with a 50% probability, promotes active mixing of genetic information. A fixed mutation rate 12% is applied to compensate for the moderate population size.

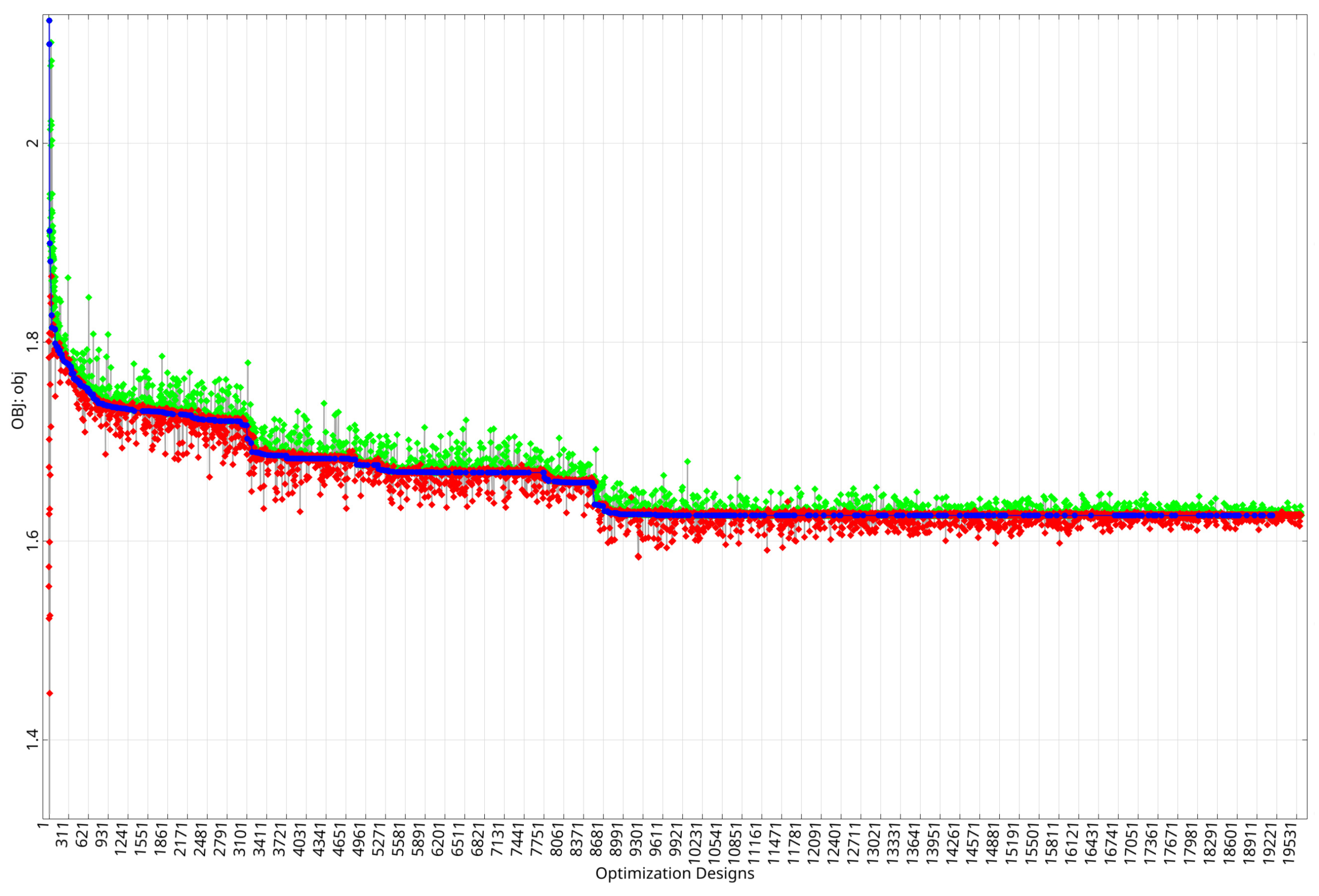

The dynamics of changes in the values of the objective function during the iterative search of the final algorithm run are shown in

Figure 10. Analysis of the convergence graph allows us to evaluate the performance of the evolutionary algorithm as effective, demonstrating the stability of the solution obtained. The total number of calculations was 19,604 iterations, which provides a sufficient statistical basis for convergence verification.

Analysis of the optimisation curve allows us to identify two characteristic phases of the process, namely the stochastic search phase and the local exploitation phase. At the initial stage (approximately the first 500 iterations), high volatility of the target function values is observed. The values vary widely, and several outliers can be seen. This high amplitude of fluctuations indicates a significant diversity of the population and the complex nature of the response surface. As the number of generations increases, the process gradually stabilises. Starting from the 1000th iteration, the trend becomes asymptotic. The algorithm enters the phase of exploiting the found local optimum, refining the solution in the vicinity of the target function value of 1.62.

Analysing the last 2000 iterations confirms the fact of convergence. In this section, the average value of the objective function is μ ≈ 1.626. Thus, the convergence analysis confirms the correctness of the evolutionary algorithm parameters, which ensured a balance between space exploration and rapid convergence to a stable solution. The geometric parameters of the resulting impeller are presented in

Table 3.

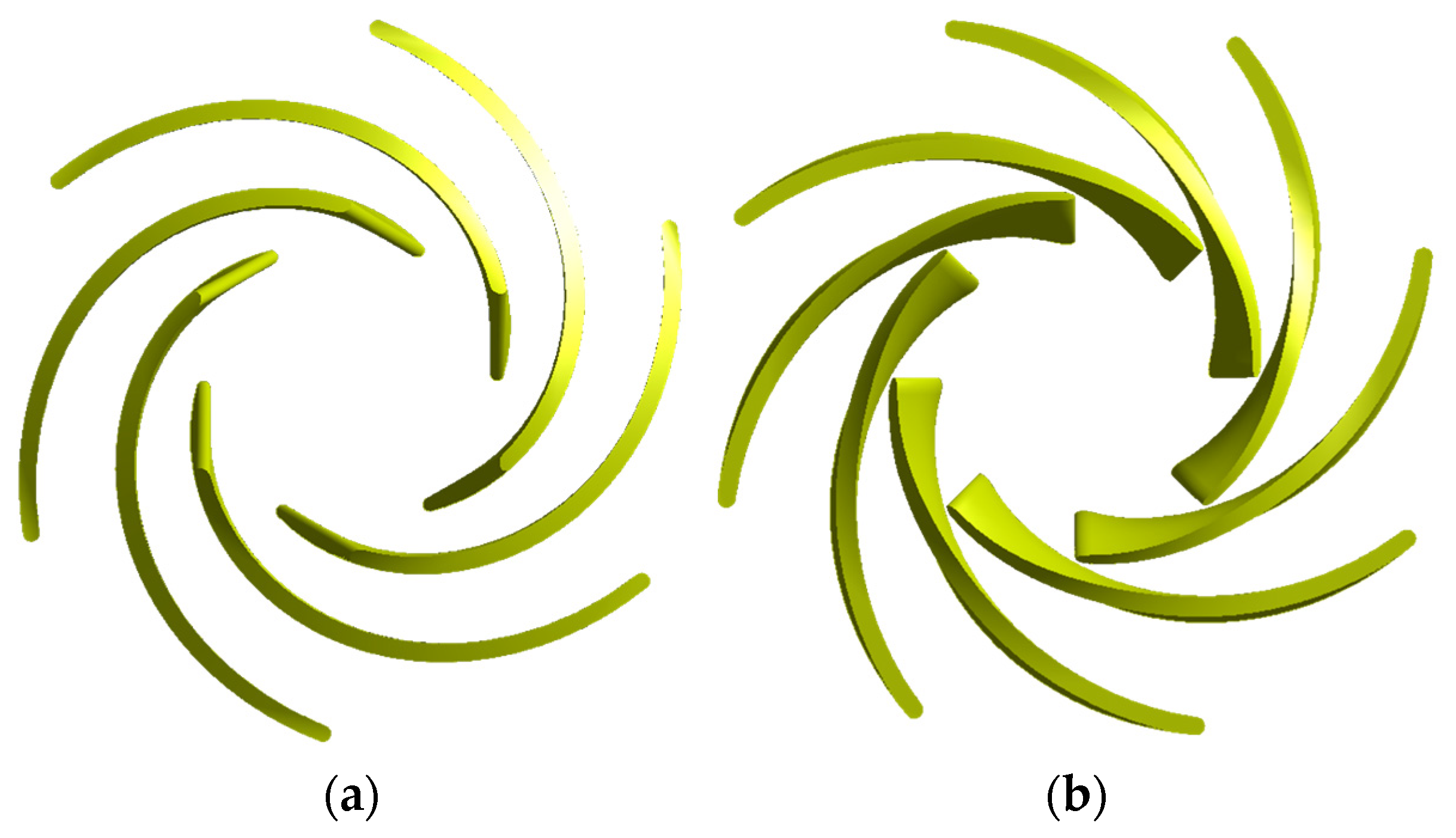

It can be seen that the fully optimised impeller has 8 blades, unlike the original 6-blade impeller. This is because the rotational torque of the impeller depends equally on the number of blades and the shape of the blades, i.e., during the optimisation of the impeller, an impeller with a reduced pitch angle θ and an increased number of blades z was obtained, which increased from 6 to 8 (

Figure 11).

2.4. Unsteady Calculation of the Obtained Geometry

A full-scale unsteady simulation was performed to verify the numerical analysis and obtain accurate hydrodynamic loads required for subsequent FSI analysis, as well as for preliminary analysis of the hydraulic characteristics of the pumps. Unlike the Steady-State RANS simulations used at the optimisation stage for a quick assessment of hydraulic characteristics, the URANS (Unsteady Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes) model was used at this validation stage.

This approach, although more computationally expensive, is important because it allows the unsteady hydrodynamic interaction between the rotating blades of the resulting impeller and the stationary elements of the pump to be resolved in time. To close the URANS system of equations, the two-parameter vortex model URANS SST was selected, which has repeatedly proven its robustness and high accuracy in tasks related to predicting flows in turbomachines [

5].

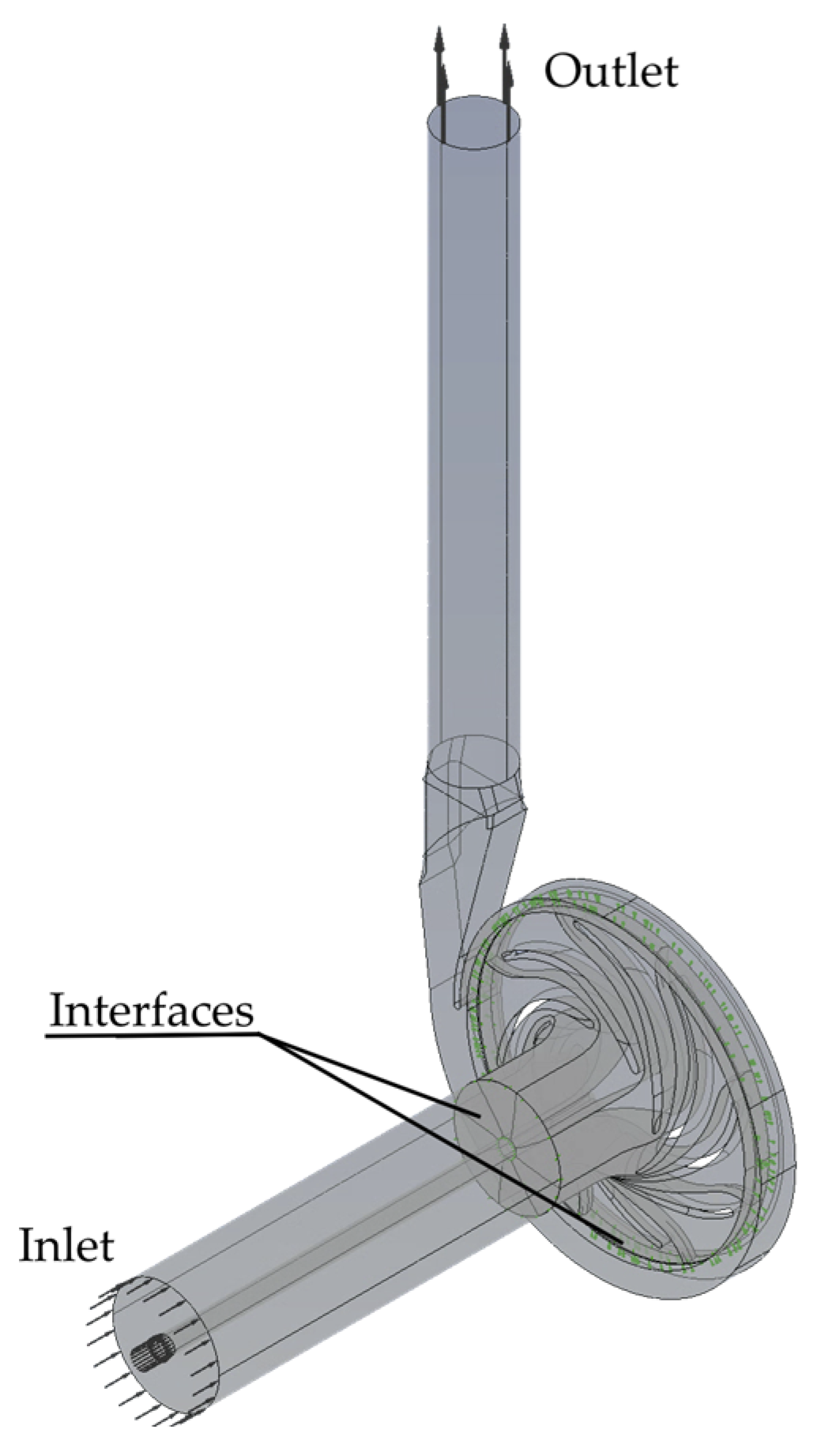

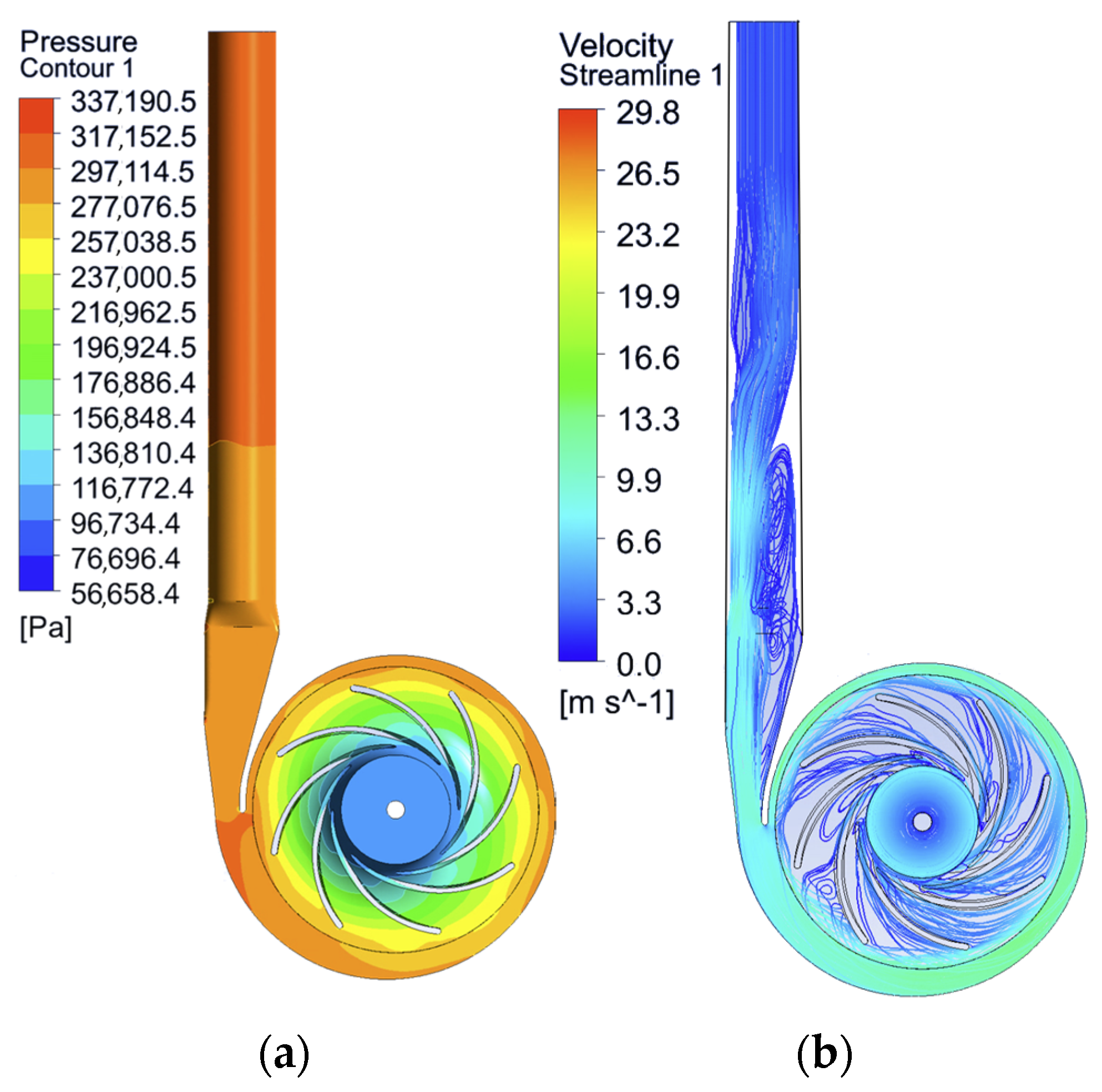

The calculation domain (

Figure 12) was defined as a complete assembly, geometrically representing the entire flow path: the suction pipe, the impeller itself, and the pump casing volute. Modelling the complete geometry made it possible to adequately account for the asymmetric effects that inevitably arise when the blades interact with the pump volute tongue.

The ANSYS TurboGrid module was used to discretise the pump impeller, as in the case of calculations performed in the optimisation cycle, the only difference being an increase in the Size Factor to 1.8, and an increase in the mesh density at the Hub and Shroud surfaces; the element count and size were increased to 60 elements. As a result, a sufficiently dense mesh was obtained to achieve the y+ parameter in area 1 (

Figure 13). The geometric models of the suction pipe and the pump casing spiral were meshed using ANSYS Mesher. For the suction pipe, a minimum element size of ΔS = 2 mm and 22 inflation layers were used for meshing, and for the pump casing, ΔS = 1 mm and 24 inflation layers were used. As a result, a mesh with 5.42·10

6 elements was obtained.

Convergence analysis is a key step in verifying CFD numerical simulations related to fluid flow and heat transfer. It ensures that the numerical results obtained do not depend on the selected model discretisation, in particular on the size of the finite elements. For the mesh used at this stage, the following options from 1·106 to 5.42·106 were investigated. The pressure obtained converged already at 2.5·106 (20.7 mH2O), and at a value of 5.42·106 it was equal to (20.52 mH2O).

Figure 14 shows a visualisation of the static pressure field, as well as streamlines with velocity indication. The data obtained does not visually contradict similar simulations.

2.5. FSI Simulation of the Obtained Structure

2.5.1. Problem Description

Given that the resulting impeller geometry is quite complex, with non-axisymmetric geometry of the impeller blades, a reduced inter-blade channel relative to the original impeller, and a low blade height at the impeller outlet, these factors complicate the production of a prototype using conventional machining methods.

To produce the prototype and conduct experimental verification, it was decided to use an impeller created using 3D printing technology. This section presents a digital analysis of the strength characteristics of the resulting centrifugal pump impeller in order to analyse the structural integrity of this assembly.

The impeller is a key element in the design of a centrifugal pump and is subjected to complex hydrodynamic loads during operation. Underestimating these loads can lead to deformation and damage to the impeller. Due to the complex geometry of the impeller and disproportionate loads, several stress concentration zones are created in the impeller, usually most pronounced at the joints between the blades and the hub or shroud. This problem is particularly common in open impellers.

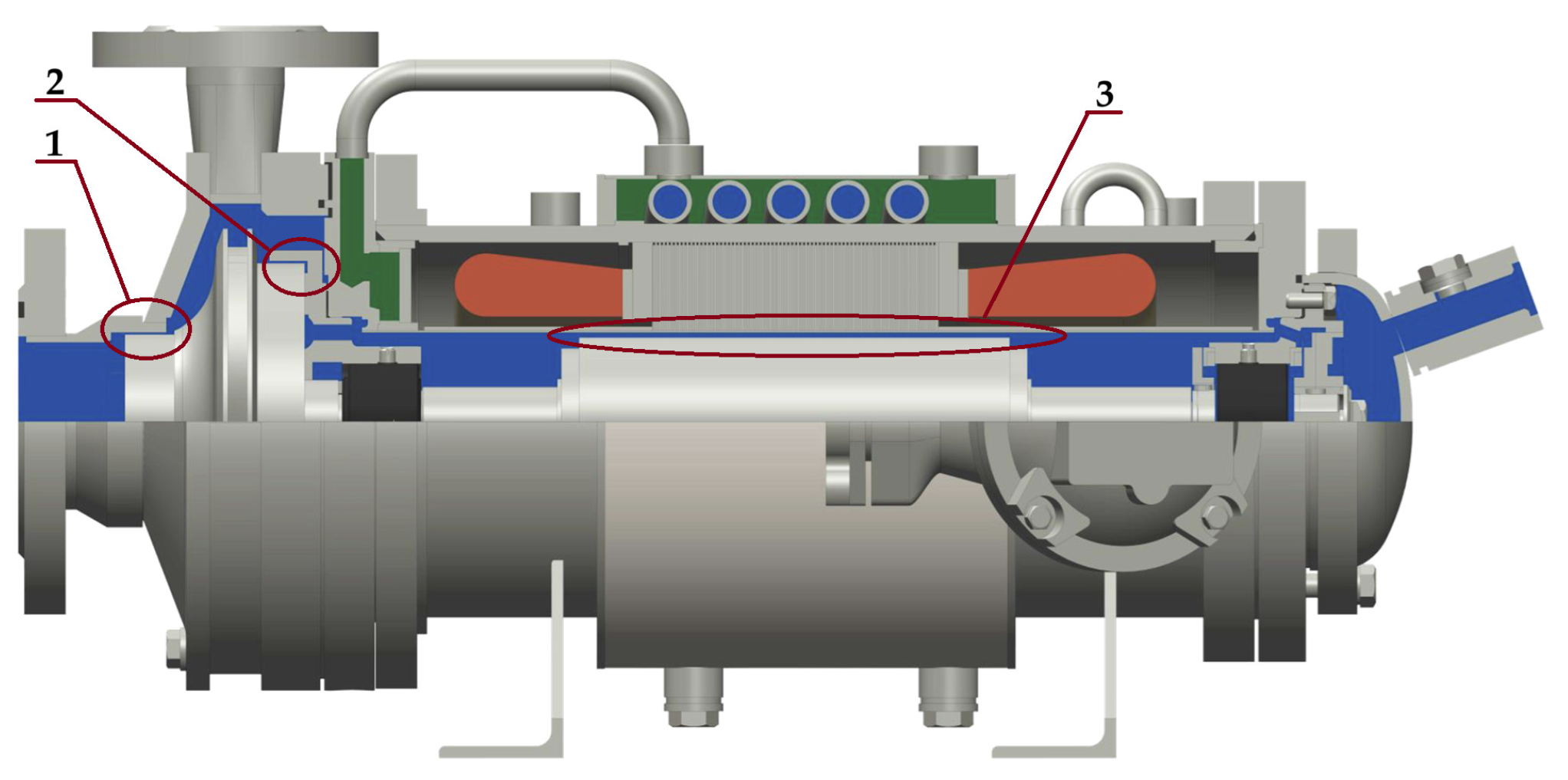

Taking into account the fact that the pump test was planned to be carried out on a monoblock centrifugal pump (

Figure 15), due to the risk of damage to the pump impeller there is also a risk of damaging the pump itself. In the event of damage to the impeller, its particles may get stuck in the front (item 1,

Figure 15) and rear gap seal (pos. 2,

Figure 15) between the impeller and the pump casing or in the gap between the rotor and stator of the pump section (pos. 3,

Figure 15), thereby jamming them or causing other damage. For these reasons, it was decided to perform a Fluid–Structure Interaction (FSI) simulation that would calculate the consequences of the interaction between the fluid flow and the structure.

The stress–strain analysis was performed in ANSYS Mechanical (Transient-Structural). The mathematical model for this calculation is based on the equation of motion for a linearly elastic body, which in matrix form has the following form [

40]

where: u represents the displacement vector of the node,

is its velocity vector, and

is its acceleration vector. On the other hand,

is the mass matrix,

is the damping matrix,

is the stiffness matrix of the structure under study, and

is the vector applied to it.

If we take into account the equivalent stiffness of the connection, we obtain the following Equation (4) [

29]:

where:

is the fluid pressure, and

is the equivalent stiffness of the connection.

2.5.2. Geometric Model

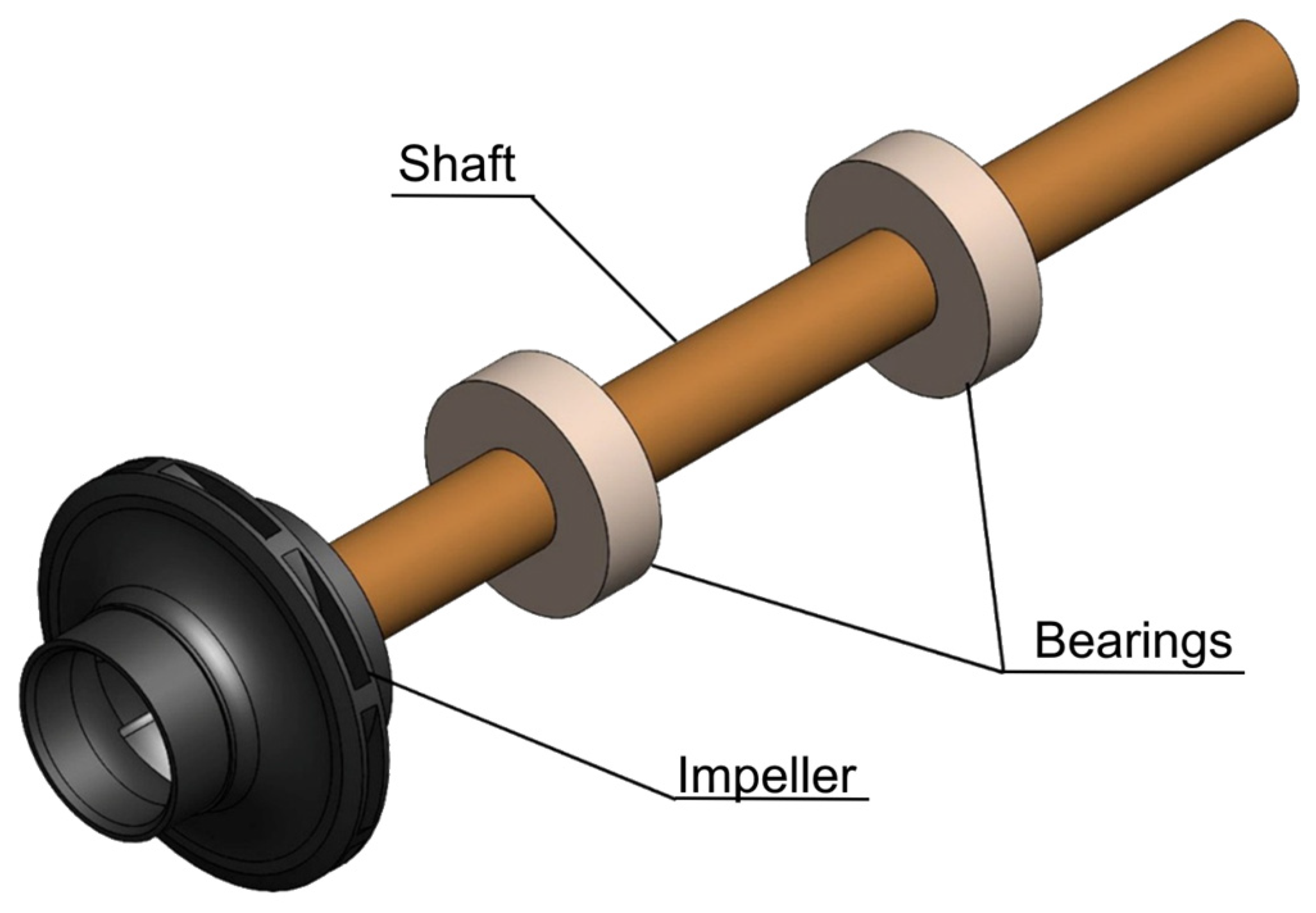

The simulation area was limited to the impeller and its associated components, i.e., shaft and bearings (

Figure 16). The model included the impeller itself, a simplified model of the drive shaft, and simplified models of the bearing supports. Simplifying the shaft and bearings is a standard practice in such tasks, where the main focus is on the impeller’s structural dynamics [

32]. The shaft is necessary for the correct transmission of kinematic torque and the application of rotational motion, while the bearing supports serve to impose adequate mechanical boundary conditions (restrictions on degrees of freedom) and fix the kinematic position of the impeller in space.

A one-way coupling strategy was used for this calculation, as the expected deformation of the impeller was expected to be relatively small due to the properties of the material selected for the prototype impeller.

It should be noted that the material for the pump impeller was selected as Nylon PA 12 Industrial (Powder) (see

Section 2.6), which is sufficiently rigid and durable, while the material for the other parts of the assembly was selected as AISI 321 Stainless Steel. The properties of the materials used in the calculation are presented in

Table 4.

2.5.3. Discretisation Model

The quality and adequacy of the grid used in digital research are key factors in achieving more accurate results. Numerical modelling of the interaction between fluid and structure in centrifugal pumps requires improved discretisation of the computational domain, taking into account geometric features and complex physical phenomena.

To perform the Transient-Structural simulation, the analysed area (

Figure 16) was discretised using Quadratic Finite Elements. This type of element was selected for the discretisation of all structural components. A convergence analysis was performed, the results of which are presented in

Table 5.

It can be noted that convergence was achieved for all evaluation criteria for the mesh used in the final calculation with 12.91·10

6 elements (

Figure 17). For the discretisation of the shaft and bearings, the maximum element size of ΔS = 2 mm was used, which in turn ensures a balance between the computing resources expended and the accuracy of the calculation. As for the impeller, a key element of the design, a maximum element size of ΔS = 0.5 mm was used for discretisation to accurately describe the areas where the blades and other stress concentrators meet.

2.5.4. Preparing the FSI Simulation

FSI analysis is an advanced computational approach for studying systems in which the interaction between fluid and solid structures is important [

41,

42]. The interaction can be divided into two main categories: one-way and two-way. In this study, a one-way coupling technique was used, in which the effect of the fluid on the mechanical structure is calculated repeatedly and simultaneously, ensuring the accuracy of the solution at the interaction boundary.

The simulation was performed using the Ansys Workbench platform, which facilitates modular connection between the Ansys CFX hydrodynamics solver and the Ansys Transient-structural mechanics solver. Data transfer between the two analysis environments is performed using a special algorithm called System Coupling, which controls time synchronisation and load transfer at the FSI fluid-solid interface. The use of the interface made it possible to transfer loads from the structural solver to the fluid solver and vice versa. System Coupling controls time synchronisation and load transfer at the FSI. The use of the interface made it possible to transfer the results obtained in

Section 2.4 (hydrodynamic and inertial loads) for strength analysis that was performed in a non-stationary setting. The boundary conditions include the application of fixed support-type constraints on the surfaces corresponding to the bearings’ exterior surfaces, blocking all degrees of freedom at these points and thus simulating the fixing conditions of the bearings.

The transient structural analysis was performed over a time interval of 20 s, providing a comprehensive characterisation of the system’s dynamic behaviour. The results of the FSI simulation are presented in

Table 6.

The maximum total deformation recorded was 0.0473 mm (

Figure 18a), indicating an adequate structural rigidity under the applied loads. Directional deformations exhibited near-perfect symmetry, with extreme values of −0.0126 mm and 0.0128 mm, reflecting a balanced distribution of stresses.

Maximum equivalent stresses reached 11.81 MPa (

Figure 18b), a value significantly below the yield limit of the PA 12 Industrial material, confirming the structural integrity of the rotor under the simulated operational conditions. The maximum principal stress of 12.83 MPa occurred concentrated in the blade fillet areas, consistent with expectations for this type of structure. The distribution of equivalent elastic deformations with a peak value of 0.00624 indicates a moderate linear-elastic response of the material throughout the analysed area.

2.6. Application of Additive Technologies for Obtaining Pump Impeller’s Prototype

The design, optimisation and production of impellers is a difficult task due to the complex geometry of the impeller’s blades. Typical manufacturing technologies used in the production of centrifugal pump impellers are casting, most often using lost wax models, or a combination of 3- or 5-axis machining followed by welding of the shroud disc. These methods of producing impellers have their strengths and weaknesses, which primarily affect the cost and time of production.

In conducting this study, it was decided to use additive manufacturing (AM) technologies, namely selective laser sintering (SLS), as an alternative to milling the prototype due to the complex geometry of the blade, the narrow inter-support channel and the low blade height b2 at the impeller outlet.

PA12 Industrial is characterised by a wide sintering window, i.e., the difference between the melting point and the recrystallisation temperature, which ensures process stability and minimises warping of the part during manufacture. PA12 has high mechanical strength, heat resistance, and biocompatibility. It has a good chemical resistance to substances such as alcohol, concentrated/diluted alkalis, esters, etc. [

43]. The hygroscopic properties of PA12 Industrial should also be noted. The low hygroscopicity of PA 12 Industrial is a determining factor for its use in precision pump components such as impellers. It should be noted that the low hygroscopicity of PA 12 allows for high dimensional stability with stable mechanical properties, which is very important primarily for maintaining the clearances in the front (main) and rear gap seals between the impeller (p.1,

Figure 19) and the pump housing (p.2,

Figure 19).

The prototype of the impeller was manufactured using the Sinterit Lisa X SLS system. This system uses a fibre-coupled diode IR laser with a power of 30 W, a wavelength of 1064 nm and a build volume of 130 × 180 × 330 mm. To prevent thermo-oxidative destruction of polyamide powder at high process temperatures during sintering, the process was carried out in a controlled nitrogen atmosphere.

The manufacturing process began with pre-processing in Sinterit Studio software v. 1.10.9.0, where the model was positioned horizontally (with the axis of rotation perpendicular to the working platform). This orientation was specifically chosen to minimise the staircase effect on the hydraulic surfaces of the blade channels and reduce the overall print height, which optimised production time (

Figure 20).

Essential process parameters included a layer thickness of 0.125 mm (a total of 697 layers were performed) and a chamber temperature of approximately 170 °C. The selected layer height of 125 µm provides surface quality comparable to investment casting (Ra ≈ 25 µm) while maintaining manufacturing efficiency.

Verification of the accuracy of the print and the conformity of the resulting impeller prototype to the geometric model was carried out not only using standard tools, but also using a 3D optical scanning system. The Creaform Handyscan 700 Elite (Metrology-Grade Handheld 3D Laser Scanner) system (Creaform Inc., Lévis, QC, Canada) was used for analysis. This system is used to capture complex object details using laser scanning technology and has a power of 7 laser crosses (on coherent blue spectrum radiation sources). It should be noted that the volumetric accuracy (depending on the size of the part) is 0.020 mm + 0.040 mm/m. The data obtained are presented in

Figure 21.

Based on the 3D scan, it can be noted that the resulting part has good accuracy. Most external surfaces are within ±0.1 mm or close to it. The only surface with a higher deviation is the inner surface of the casing, within +0.3–+0.4 mm, which is small enough not to affect the functional characteristics of the impeller.

It should be noted that the internal dimensions of the impeller inlet and the internal diameter of the blades had the highest error, which correlates with the data on volumetric shrinkage. The resulting pattern is consistent with the characteristics of the sintering technology.

To maintain the clearances in the front and rear seals between the impeller (position 1,

Figure 15) and the pump casing (position 2,

Figure 15), these surfaces were machined on a lathe (

Figure 22). The material demonstrated good machinability. The rotor assembly was also balanced prior to testing.

2.7. Experimental Testing

Experimental validation of the resulting impeller was carried out using a hermetic monoblock centrifugal pump of the CH series, manufactured by CRIS Hermetic Pumps (Chișinău, Republic of Moldova) and evaluated in accordance with the requirements of ISO 9906:2012.

The main objective of the experimental validation (

Figure 23a) was to determine the main characteristics of the pump (total pump head, current and power consumption).

In the experimental validation (

Figure 23b), a closed test method was used, in which a constant fluid flow rate was maintained, and the pressure in the tank was used as an independent variable. Pure cold water was used as the working fluid, the temperature of which was controlled by a thermometer to determine the exact density. The pump was started at a set flow rate measured by a flow meter installed on the suction line. The flow rate was set in accordance with the Q-H characteristic point under study, i.e., at least with the gate valve closed, at the minimum flow rate Q

min = 2 m

3/h, at the nominal value (BEP) Q

nom = 6.3 m

3/h and at the maximum flow rate Q

max = 9 m

3/h. The head was recorded using pressure gauges installed on the suction and discharge lines.

3. Results

3.1. Numerical Validation

To verify the obtained geometry of the impeller and quantitatively assess the effectiveness of the proposed geometry, a comparative numerical analysis was performed. The comparison was made between the baseline pump model and the optimised configuration obtained as a result of EA.

Since the steady-state method (RANS) used at the response surface construction stage does not allow for a full assessment of the dynamic characteristics of the flow, the final numerical validation was performed using unsteady Reynolds equations (URANS). This approach is necessary to correctly take into account the effects of rotor–stator interaction (RSI) and to analyse unstable vortex structures arising in the inter-blade channels and spiral discharge. This section compares the integral energy characteristics and flow patterns in the flow section.

In the first instance,

Figure 24 shows a visualisation of the static pressure field displayed on the unfolded transverse surface at half the blade height (50% span). It can be seen that the optimised impeller creates a pressure zone with a smoother transition at the impeller’s outlet.

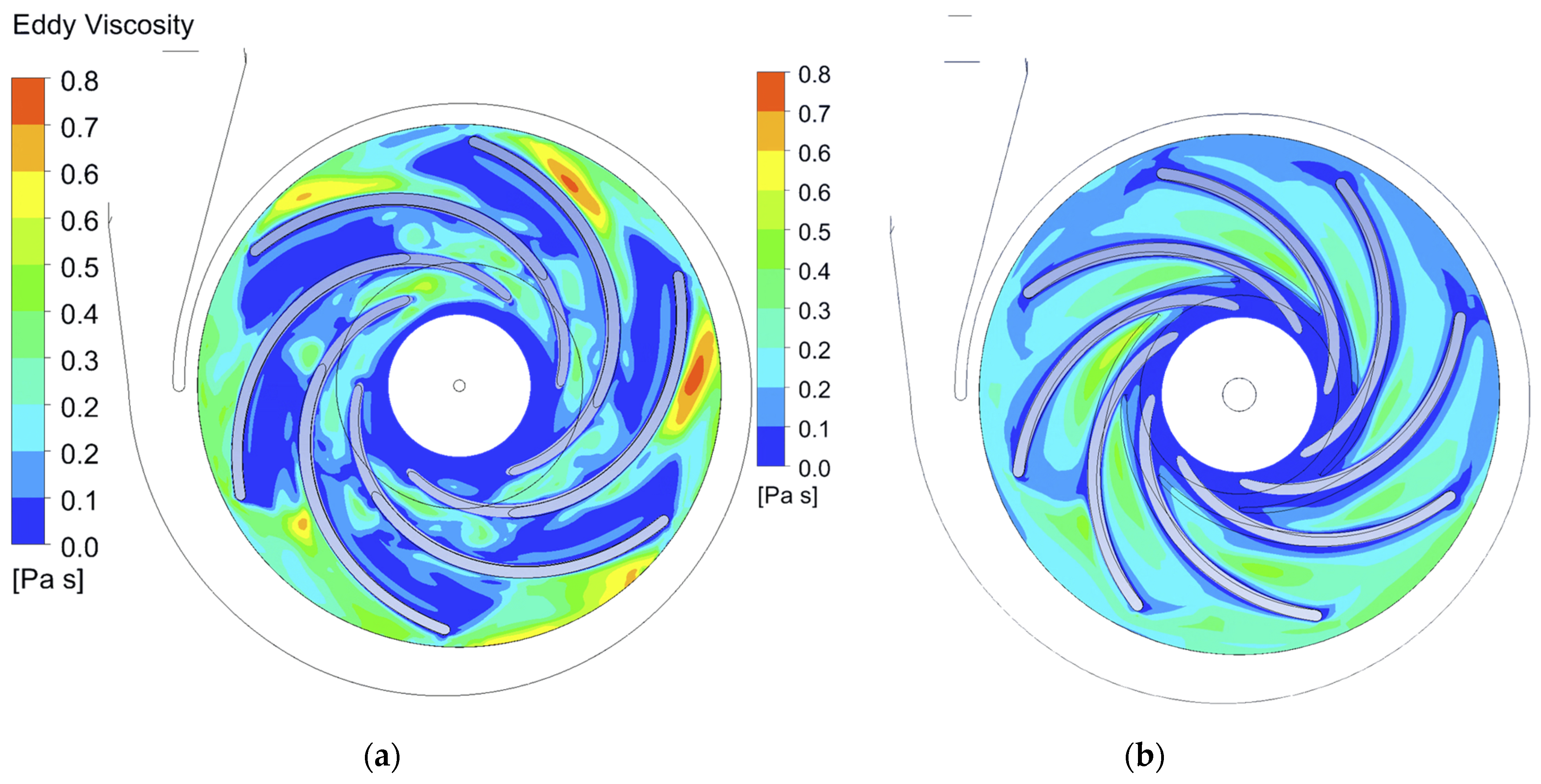

A comparative analysis of vortex (turbulent) viscosity fields, shown in

Figure 25, demonstrates a qualitative improvement in the flow structure in the optimised model. Unlike the base geometry, where extensive areas with critically high vortex viscosity values were observed on the suction side of the blade (especially near the trailing edge), these issues were successfully eliminated in the optimised configuration. This improvement’s physical significance stems from its ability to suppress excessive turbulence.

Eddy viscosity serves as an indicator of the intensity of turbulent mixing and dissipation of the kinetic energy of the flow. The high-velocity gradients and pressure irregularities characteristic of the base model led to increased hydraulic losses. Consequently, the elimination of high-viscosity zones in the inter-blade channels and at the impeller outlet indicates flow stabilisation, which directly leads to an increase in the hydraulic efficiency of the pump.

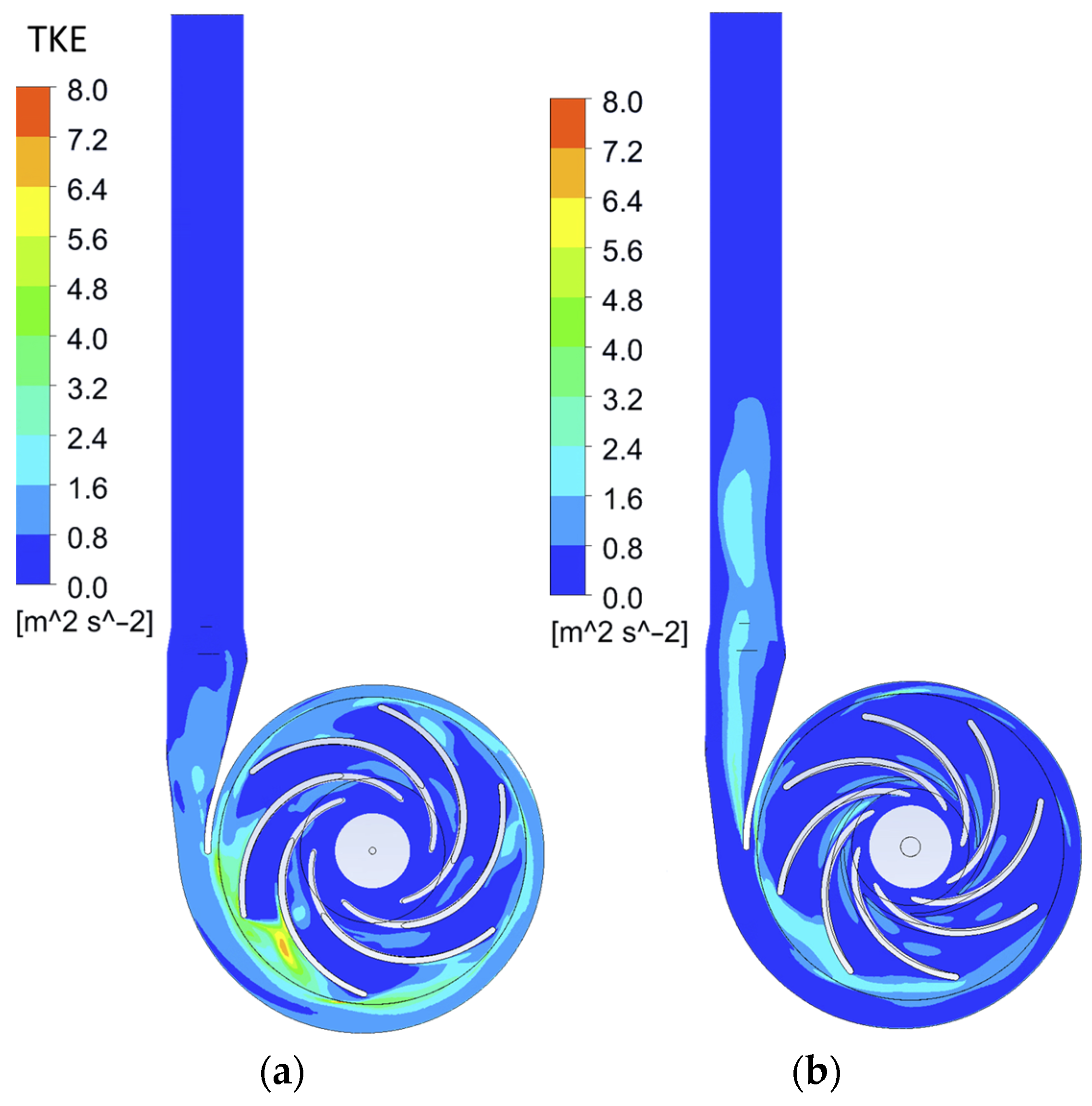

In addition to the analysis of eddy viscosity, an analysis of turbulent kinetic energy was performed (

Figure 26). Turbulent Kinetic Energy (TKE) is a direct indicator of the intensity of velocity pulsations, which are the main source of unsteady loads on the impeller blades. For prototypes manufactured using SLS, assessing the turbulent kinetic energy level is critical, as a reduction in the pulsation component directly correlates with a reduction in the risk of fatigue failure and vibrations. Thus, turbulent kinetic energy field analysis allows verification of not only energy efficiency but also the operational reliability of the optimised geometry.

A comparison of TKE contours shows that the base model is characterised by extensive areas of high turbulence, particularly along the suction side of the blade and extending into the wake region at the outlet of the impeller. These elevated levels indicate the presence of strong shear layers and flow separation, where the average flow energy is actively converted into turbulent oscillations, while the pronounced intensity of the wake suggests a strong interaction with the stationary spiral tongue. On the other hand, it can be seen that the optimised geometry demonstrates a noticeable weakening of turbulent kinetic energy formation, where high-energy turbulent zones in the passages between the blades are significantly suppressed, and the wake at the trailing edge is significantly reduced in both magnitude and spatial extent. This reduction in turbulent kinetic energy has profound implications for both performance and reliability.

Analysing the quantitative results, we can note that the optimisation output demonstrates a significant improvement in the internal dynamics of the impeller flow. In particular, the analysis shows the elimination of large-scale recirculation zones previously observed on the suction sides (rear surfaces) of the blades. In the baseline design, these zones were characterised by high turbulent viscosity values reaching 0.8 Pa·s. In the optimised geometry, this parameter was reduced to the range of 0.3–0.4 Pa·s, with no local peaks observed, indicating a more uniform and stable flow distribution. A similar trend is observed in the distribution of turbulent kinetic energy. Extensive areas with high turbulence intensity, where TKE values reached 8.0 m2/s2 in the original design, were significantly mitigated. In the optimised version, peak TKE values decreased to 2.4 m2/s2. This reduction in TKE and viscosity confirms the suppression of flow separation and energy dissipation, which directly correlates with the recorded increase in the hydraulic efficiency of the pump.

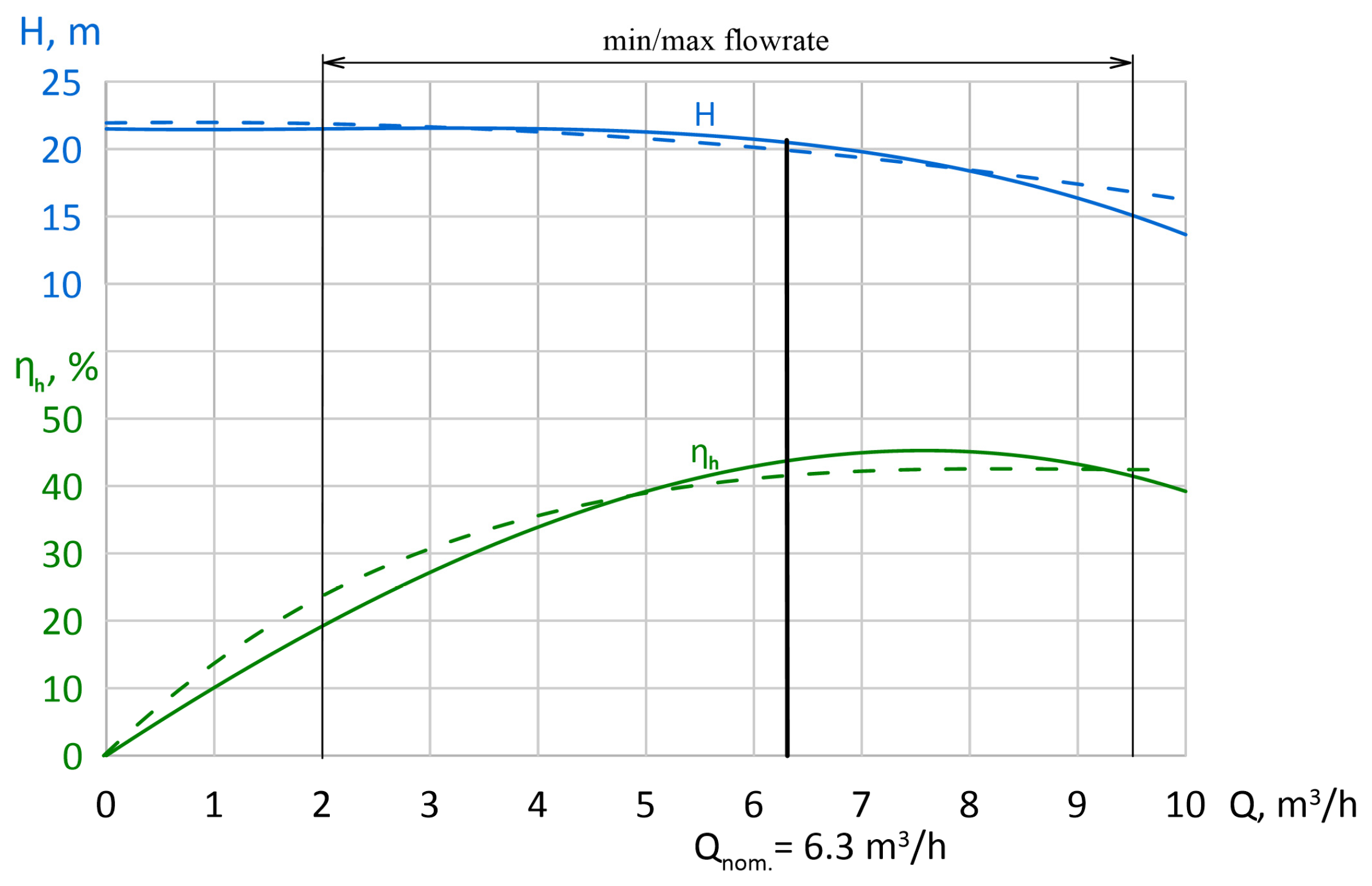

We can note that increasing the number of blades while decreasing the wrap angle reduces the hydrodynamic load on each individual blade. The optimised blade design distributes the load more evenly, suppressing separation without excessive friction losses. This compromise between load and friction losses is defined as the hydraulic optimum for this particular flowrate at BEP. However, analysing the comparison of the integral characteristics of the baseline and optimised impeller geometry presented in

Figure 27, a number of conclusions can be drawn. Analysis of the H

sim curves shows that both geometries demonstrate a similar characteristic shape over a wide range of flow rates. However, in the maximum flow rate Q

max zone, it can be seen that the head of the optimised impeller decreases to 15.1 mH

2O. This phenomenon is due to the increased number of blades to 8, which leads to a narrowing of the inter-blade channels. Considering that at high flow rates and as a result of a significant rise in flow velocity, an increase in the hydraulic resistance of the impeller can be observed.

A comparison of efficiency characteristics demonstrates a qualitative improvement in performance. The maximum hydraulic efficiency of the optimised pump has shifted to the BEP point Qnom = 6.3 m3/h, reaching a value of ηh = 43.72%, for comparison, the peak efficiency of the baseline geometry was only ηh = 40.85%

3.2. Results of FSI Analysis

The calculation results indicate that the equivalent stress is 11.81 MPa, which remains below the tensile strength of the PA-12 Industrial material (48.7 MPa). The deformations are within the usual range. This indicates that the impeller prototype can be fabricated utilizing the SLS process and evaluated for hydraulic properties.

Table 7 presents the main technical characteristics of the pump models under study, according to the methodology used in

Section 2.5.4, and the results of the equivalent stress calculations.

The analysis shows that, for the CH 6.3/20 and CH 100/32 pumps, the stress levels (11.8 and 24.45 MPa, respectively) are within the safe range, not exceeding 50% of the strength limit of PA-12 material (48.7 MPa). This confirms the possibility of manufacturing the impellers of these pumps using the SLS method. However, for the high-pressure model CH 100/125, the calculated equivalent stress is 51.7 MPa, which exceeds the strength limit of sintered polyamide. This indicates limitations in the applicability of PA-12 additive technologies for high-power pumps without additional structural reinforcement or material modification, which in turn indicates the mandatory implementation of FSI simulations in the centrifugal pump optimisation scheme when testing prototypes obtained by additive manufacturing.

3.3. Results of Experimental Validation

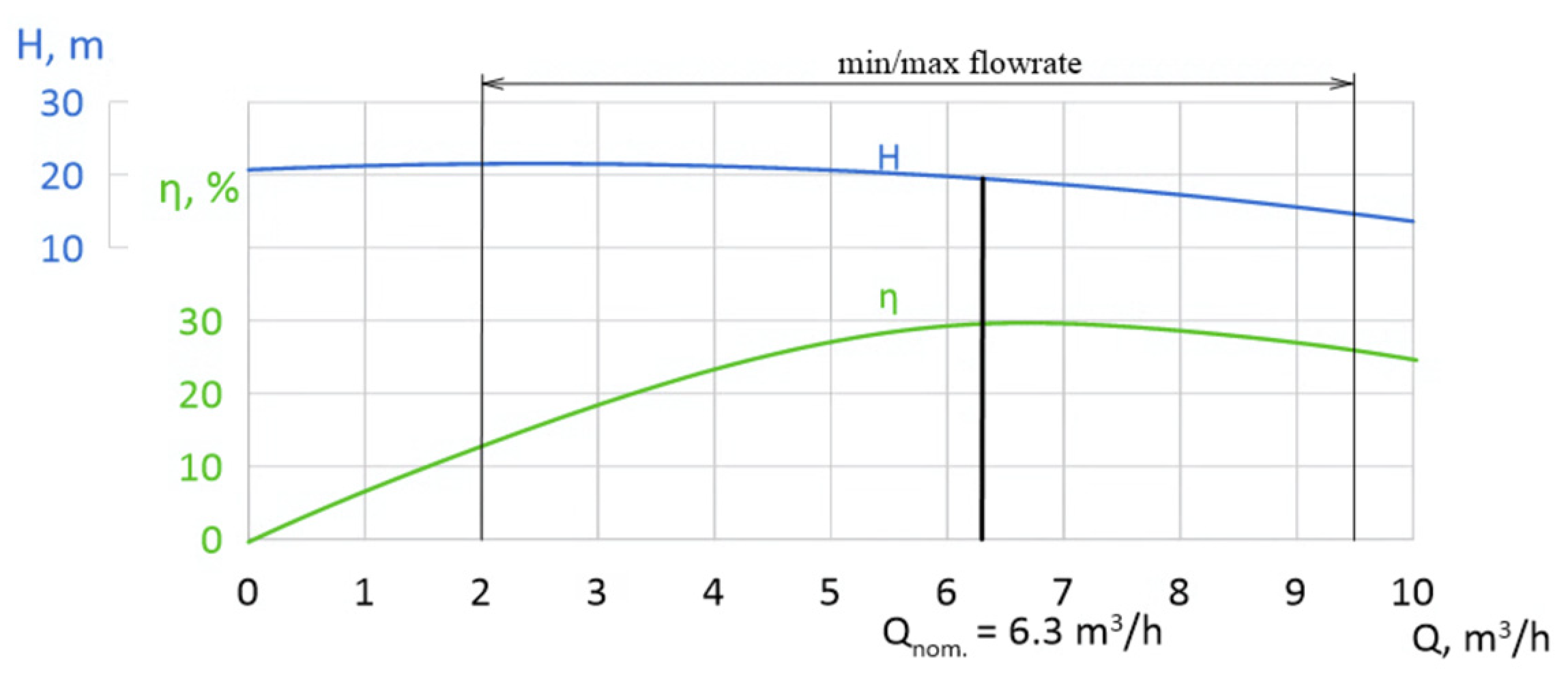

To verify the results of numerical optimisation and evaluate the actual characteristics of the impeller manufactured using SLS technology, experimental tests were conducted on a hydraulic test bench using a sealed turbulent pump model.

The experimental characteristic curves (Q-H and Q-η) obtained for the optimised prototype are shown in

Figure 28. The results show a strong correlation with the numerical predictions obtained using URANS simulations.

Before conducting a detailed analysis of the hydraulic characteristics, a thorough uncertainty assessment was performed to verify the reliability of the experimental data. The total relative error in the efficiency calculation was determined using the root mean square (RMS) method and was found to be ±0.93%.

This aggregate error was obtained based on the measurement accuracy of the main variables: the relative errors of flow rate Q, power consumption N, and rotational speed n did not exceed ±0.5%, while the measurement accuracy of head H remained within ±0.6%. Such a small error confirms the high accuracy of the measurements and the reliability of the subsequent comparative analysis.

The main result of the experimental verification is the empirical confirmation of the increase in efficiency predicted by the numerical model. As shown in the performance curves, the pump equipped with an optimised impeller geometry achieved a pump unit efficiency of 29.6%. This value confirms the data obtained in the digital validation, considering the nominal declared efficiency of the shielded motor of 72%.

To confirm the numerical accuracy, the simulated head Hsim was compared with the experimental head Hexp at the nominal point. The numerical model predicted a head of 20.52 m, while the experimental tests gave a value of 19.9 m. The relative discrepancy obtained is approximately 3.1%.

This deviation is considered acceptable and can be largely explained by the complex volumetric losses inherent in pumps with sealed motors, in particular, the recirculation flow required for the secondary circuit (rotor cooling and bearing lubrication), which is difficult to fully account for in a simplified hydraulic CFD model.

4. Discussion

The key result of the work was the development of a methodology for the rapid technical modernisation of sealed centrifugal pumps manufactured in the Republic of Moldova. The aim of the research was not only to theoretically improve hydrodynamic characteristics, but also to increase the competitiveness of local manufacturers through the introduction of affordable R&D tools.

As a result of optimisation, a working wheel geometry was obtained that differed structurally from the original model. The evolutionary algorithm converged to a configuration with 8 blades (compared to 6 in the original model) and a reduced wrap angle θ. Increasing the blade pitch while simultaneously adjusting the wrap angle θ of the blades improved the turbulent flow characteristics, which, as shown in the

Section 3, led to a decrease in turbulent viscosity and an increase in efficiency.

The data obtained justifies the use of Steady-State RANS simulations in the computationally intensive iterative stage of the optimisation cycle. Although RANS inherently simplifies the flow physics, our comparison shows that it accurately reflects the average flow trends and performance gradients necessary for effective surface response mapping. The main advantage of the RANS approach is a significant reduction in computational costs. By using a single-blade channel model with periodic boundary conditions, the discretised mesh was reduced from 5.42·106 nodes (full URANS model) to 0.5·106 nodes.

For a study involving 1200 DP, this reduction proved decisive, cutting the optimisation time from several months to approximately 2–3 weeks. Such efficiency is important for industrial design cycles, where iterative exploration of the design space is required.

A comparative analysis of the optimised geometry shows that the RANS model predicted an Hsim head of 20.7 m, which is slightly higher than the 20.52 m calculated by the URANS (Unsteady RANS) model on the full geometric model, as well as a slight reduction in torque. This discrepancy is directly related to the steady-state formulation of the problem and the absence of pressure pulsations caused by the passage of the impeller blades past the spiral casing tongue. Despite this slight overestimation of performance, the RANS model remains a reliable tool for determining optimal geometric trends.

An important aspect of implementing this methodology is the economic feasibility of using additive technologies in the manufacture of prototypes.

The production of an experimental prototype from PA-12 polyamide using the SLS method cost 145 euros, while the cost of producing a similar prototype using traditional methods (milling and metal welding) is estimated by suppliers at 600 euros. A fourfold reduction in prototyping costs significantly lowers the entry threshold for R&D in small and medium-sized enterprises, allowing for iterative product improvements without capital expenditure.

Although in this study the validation was carried out using a pump with a low specific speed nq = 13, the developed optimisation structure has no strict geometric constraints. The parametric definition of the meridional profile and blade angles used is universal and can be adapted for the design of pumps with different centrifugal pump configurations. Thus, the demonstrated workflow serves as a generalised proof-of-concept.

Despite successful validation, the authors acknowledge the need for further development of the methodology. The following tasks have been identified as priority areas for future research:

Research into the reinforcement of plastic prototypes (e.g., the use of composites or hybrid materials) is planned to increase their service life under high loads, where pure PA-12 may not be sufficiently reliable.

The current optimisation focused on efficiency at the nominal point. Future iterations of the algorithm will take into account additional factors, such as minimising cavitation margin (NPSH), which is critical for industrial pumps.

To ensure stable operation across the entire operating range, we plan to expand the scope of research to include not only the nominal flow rate Qnom in the objective function, but also the minimum Qmin and maximum Qmax performance modes. This will allow us to create pumps with a flatter efficiency curve that are resistant to changes in the consumer’s system.