Abstract

A cobalt-containing zeolitic imidazolate framework (ZIF-67) was carbonized by different routes to composite materials (cZIFs) composed of metallic Co, Co3O4, and N-doped carbonaceous phase. The effect of the carbonization procedure on the water pollutant removal properties of cZIFs was studied. Higher temperature and prolonged thermal treatment resulted in more uniform particle size distribution (as determined by nanoparticle tracking analysis, NTA) and surface charge lowering (as determined by zeta potential measurements). Surface-governed environmental applications of prepared cZIFs were tested using physical (adsorption) and electrochemical methods for dye degradation. Targeted dyes were methylene blue (MB) and methyl orange (MO), chosen as model compounds to establish the specificity of selected remediation procedures. Electrodegradation was initiated via an intermediate reactive oxygen species formed during oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) on cZIFs serving as electrocatalysts. The adsorption test showed relatively uniform adsorption sites at the surface of cZIFs, reaching a removal of over 70 mg/g for both dyes while governed by pseudo-first-order kinetics favored by higher mesoporosity. In the electro-assisted degradation process, cZIF samples demonstrated impressive efficiency, achieving almost complete degradation of MB and MO within 4.5 h. Detailed analysis of energy consumption in the degradation process enabled the calculation of the current conversion efficiency index and the amount of charge associated with O2•−/•OH generation, normalized by the quantity of removed dye, for tested materials. Here, the proposed method will assist similar research studies on the removal of organic water pollutants to discriminate among electrode materials and procedures based on energy efficiency.

1. Introduction

Carbon-based materials appeal to material scientists aiming to develop highly functional catalysts active for varying applications, from charge storage and electrocatalysis to environmental remediation [1,2,3,4,5,6]. The latter relies on the result from the former, where electroactivity may be used as the first step of an efficient procedure for the electrochemical degradation of organic water pollutants [7]. This advanced process, gathering the best of both physical and chemical remediation techniques, is being increasingly investigated, targeting a number of different pollutants, particularly in the degradation of contaminants such as dyes [8]. Dyes offer a wide range of structures to be used as model compounds, mimicking complex heteroatom-containing pollutants [9], or serving as targeted pollutants due to colorful clothing and the mass production industry of household items and foods [10,11]. Electrodegradation may be influenced by the properties of the pollutant dye and the operating conditions in the electrochemical system [12], in addition to the intrinsic physicochemical characteristics of carbons, which are used as electrode materials [13].

The formation of active carbon materials often starts with biowastes as precursors [14]. However, their diversity leads to inconsistencies in composition, functional groups, and a lack of well-defined structure. In search of neatly structured and high porosity precursors [15], different metal–organic framework (MOF) structures [16], especially zeolitic imidazolate frameworks (ZIFs), are promising materials for water remediation applications [17]. The synthesis of ZIF-derived carbons is commonly a two-step process: first, the synthesis of ZIF precursors is performed through coordination of metal ions with imidazole linkers, followed by thermal conversion into carbon materials in an inert atmosphere [18]. With their specific textural properties and adjustable surface chemistry, ZIF-derived carbon materials exhibit exceptional electroactivity and adsorption capacity, representing promising candidates for advanced electrochemical oxidation processes for pollutant treatment in aqueous environments [19].

Complex electrochemical processes, including adsorption, electron transfer, and oxidation, enable efficient degradation methodology, which is explored so far for different pollutants [20]. These methods offer an advantage over chemical oxidation methods [21] that often require rather acidic conditions, whereas natural waters have slightly basic pH values. Thus, electrochemical methods offer the advantage of electro-generated reactive species and electrolyte design to reflect real water in situ treatment [22]. Electrooxidation has been, so far, successfully applied for the degradation of pesticides using carbon monolith electrodes [23], as well as for the degradation of phenols on N-doped graphene [24] and O-doped carbon nanotubes within the electro-Fenton process [25]. The efficiency of H2O2 electrochemical activation relies on the formation of hydroxyl radicals (•OH) through peroxide reduction H2O2 + e− → •OH + OH−, and the associated process of formation of superoxide anion radical (O2•−) by the one-electron oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) O2(g) + e− → O2•− [26]. Setting a suitable potential enables dye molecule migration to the surface of the carbon electrode due to electrostatic interactions. Concomitantly, the generation of •OH and O2•− radicals through ORR in basic conditions offers highly oxidative surroundings able to mineralize dye molecules. This route is underinvestigated and somewhat different from anodic electrooxidation, where hydroxyl radicals are produced during water oxidation on electrodes at high overpotentials [22]. Under such conditions, concurrent oxygen evolution reaction is favored, which significantly decreases the energetic efficiency toward radical formation and thus the degradation of dyes.

Following a scalable synthesis route, we recently gained highly electroactive N-doped carbon/Co/Co3O4 composites by direct carbonization of ZIF-67 [13]. Different methods were employed to form a comprehensive image of the resulting composites’ morphology, porosity, electrochemical behavior, and surface chemistry. Composites showed high electrical conductivity and excellent electrocatalytic activity toward ORR. Based on these results, we propose a novel application of ZIF-67-derived N-doped carbon composites for electrodegradation of dyes and examine key parameters concerning dye type and reaction kinetics in determining the mechanism of the adsorption and energy efficiency of the electrodegradation process. Two different types of synthetic dyes are selected as model compounds: methylene blue (MB), a cationic, phenothiazine, basic dye, widely used in the textile industry and medical applications; methyl orange, an anionic, azo, and acidic dye, commonly used as a pH indicator, as well as in the textile industry and printing. These compounds are toxic and considered harmful to the environment, so the development of efficient, cost-effective, sustainable methods for their removal from wastewater is challenging and has received great research attention.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

The detailed synthesis procedure for the ZIF-67 precursor is given in [13]. In short, cobalt nitrate hexahydrate aqueous solution was mixed with ammonia/triethylamine (TEA) solution of 2-methylimidazole (HMIM) in concentrations that give the final reaction mixture with Co(NO3)2:HMIM:NH3:TEA:H2O molar composition of 1:2:32:8:165, respectively. After 10 min of reaction, the mixture was dispersed in 500 mL of water, and after an additional 30 min, the precipitate was collected by filtering, rinsed, and vacuum-dried at 60 °C for 4 h.

For the carbonization of the ZIF-67 precursor, heating at a rate of 10 °C/min under argon in a horizontal tube furnace (Elektron, Banja Koviljača, Serbia) was applied up to 800 °C without holding time, and with holding at 800 °C and 900 °C for 3 h, resulting in final materials denoted as cZIF800, cZIF800/3, and cZIF900/3, respectively.

2.2. Characterization

The Nanoparticle Tracking Analyzer (NTA) NanoSight 300 (Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, Worcestershire, UK) was utilized to obtain particle size distribution profiles and determine the particle size values, using a dynamic mode. The samples were dispersed in distilled water to gain concentrations of 4–9 × 108 particles/mL that correspond to over 40 particles per frame (conditions optimal for particle tracking) and were sonicated for 1 min before NTA measurement. The sample dispersion was exposed to a 532 nm laser beam for five captures (video recordings) per measurement, with each capture recording distinct segments of the overall dispersion volume over 60 s. All measurements were performed at room temperature. The data from the resulting videos were analyzed using the NanoSight NTA 3.4 software.

Zeta (ζ) potential was measured using Zetasizer Nano ZS ZEN 3600 (Malvern, Panalytical, Malvern, Worcestershire, UK). For these measurements, 1 mg of the sample (ZIF-67 and cZIFs) was dispersed in 10 mL of 0.1 M KOH. After homogenization in an ultrasonic bath for 10 min, the zeta potential of dispersed particles was measured, and the results were expressed as the mean value of three measurements.

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy measurements were conducted using a Nicolet iS20 spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) employing the KBr pellet technique. Spectral data were collected within the wavenumber range of 4000–400 cm−1, with 32 scans per spectrum and a resolution of 4 cm−1.

2.3. Adsorption Study

The batch adsorption test was performed to investigate the retention capacity of the tested cZIFs for dye molecules, cationic (methylene blue, MB), and anionic (methyl orange, MO).

The suspension used in the batch adsorption test comprised 1 mg/mL of cZIF sample and different MB (Merck, Rahway, NJ, USA) or MO (Merck, Rahway, NJ, USA) solutions, so that their concentration ranged from 10 to 100 mg/L. Equilibration of the suspensions took place over 24 h on a laboratory shaker (OLS Shaking bath, Grant Instruments, Delhi, India) operating at 110 rpm and 23 °C. Following centrifugation to separate the solid phase, the remaining dye in the supernatant was quantified using an Evolution 220 UV–vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

The adsorption isotherm data were fitted using three often used Freundlich, Langmuir, and Langmuir–Freundlich (LF) models to cover empirical, theoretical, and combination isotherm equations. The Langmuir–Freundlich isotherm, q = qmKCe1/n (1 + KCe1/n)−1, describes processes on nonuniform surfaces with Ce being the equilibrium concentration (mg/L); q is the amount of adsorbate adsorbed at the surface (mg/g), K is a constant reflecting binding energy, while qm represents the maximum monolayer theoretical capacity for adsorbate (mg/g). The heterogeneity index (1/n) suggests a homogeneous surface when approaching one, while deviations indicate heterogeneity. Since a majority of adsorption data is subjected to erroneous fitting procedures, improperly boosting correlation through linear models [27], we tested non-linear equations with suitability determined based on the coefficient of determination (R2) and adjusted R2 (Adj. R2).

2.4. Electrochemical Measurements

Electrochemical investigations utilized a glassy carbon (GC) electrode coated with a thin film of cZIF sample as a working electrode. A liquid ink suspension was prepared by sonicating 5 mg of the tested sample in a mixture of 0.5 mL ethanol, water, and Nafion (Chemours, Villers-Saint-Paul, France). Loading of the tested material, calculated from the difference in the mass of the GC electrode with and without cZIF material on its surface, amounted to 1.2 mg. The electrochemical measurements assessed the degradation of MB/MO using chronoamperometry (CA), in a conventional three-electrode cell with a Pt wire counter electrode and a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) as the reference electrode, in 0.1 M KOH electrolyte. An Ivium VO1107 potentiostat/galvanostat (Ivium Technologies, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) was employed to apply the potential and measure the current response. Throughout the experiment, a slight flow of oxygen was maintained through the electrolyte to ensure its saturation. All measurements were conducted under standard pressure and ambient temperature. Combined UV–vis spectroscopy (UV-1800, Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan) and electrochemical CA measurements were performed with a solution containing 10 ppm MB (MO) in 0.1 M KOH, continuously stirred at 900 rpm during the measurement process. CA was carried out at a constant potential (−0.8 V vs. SCE; ORR plateau with constant radical generation [9]) with 3 mL aliquots being drawn periodically during 270 min from the studied MB (MO)/KOH solution for UV–vis measurements. The monitoring of the whole UV/vis range was applied to detect whether or not the decolorization resulted from colorless leuco-MB (the reduced form of MB) [28] or from MB degradation and subsequent reduction in colored degradation products [29,30]. Degradation kinetics and energy consumption were assessed to further determine the cZIF material’s efficiency in dye degradation.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Particle Size of ZIF-67 and c(ZIF)s by Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis

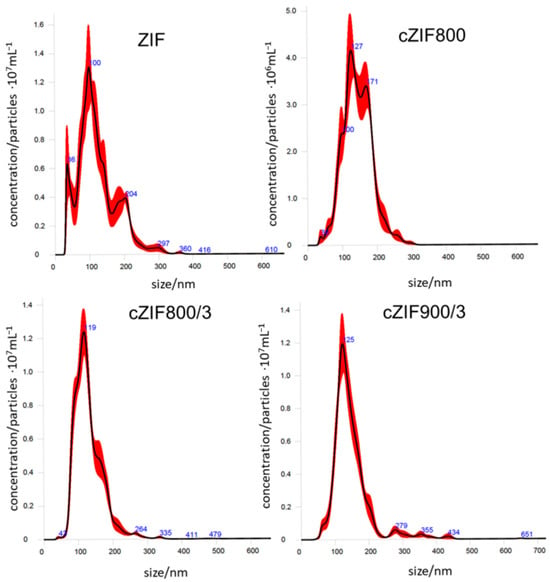

To determine the particle sizes of the materials studied, which are important for their adsorption performance, NTA measurements were conducted. Graphs depicting particle size distributions are presented in Figure 1. The particle sizes of dispersed samples are presented in terms of the average particle size value (mean diameter) and the most frequent particle size value (diameter mode). The mean diameter of the ZIF-67 precursor is 122 nm, and the diameter increases upon carbonization to 144 nm, 130 nm, and 148 nm for cZIF800, cZIF800/3, and cZIF900/3, respectively. The highest average particle diameter measured for the sample produced at 900 °C can be explained by some agglomeration of particles. The most frequent particle size value increases from 100 nm for the precursor ZIF-67 sample to 130 nm (cZIF800), 116 nm (cZIF800/3), and 131 nm (cZIF900/3). Measured particle size parameters for cZIF800/3 are lower than values detected for cZIF800 and cZIF900/3. Literature data on particle size measurements using the NTA technique for MOF-based materials are scarce. Here, measured values of the mean diameter for cZIFs are similar to the value reported recently for carbonized MOF-5 (132 nm) [31].

Figure 1.

Averaged finite track length adjustment (FTLA) concentration vs. particle size graphs from NTA measurements for ZIF-67 precursor and carbonized derivatives cZIFs, with the standard error of the mean as a red shaded area.

A substantial improvement in uniformity of particle size was attained through the extension of the carbonization time to 3 h when graphs for cZIF800 and cZIF800/3 were compared. The central peak of cZIF800 at 127 nm shifts to around 119 nm, while the other two lower peaks found in the cZIF800 particle size distribution profile merged as shoulders on either side of the central peak for cZIF800/3. For sample cZIF900/3, the central peak positioned at 125 nm narrowed, while its shoulders weakened. To conclude, an extension of 800 °C treatment leads to more uniform particles, while an increase in temperature to 900 °C leads to particle enlargement alongside improved particle size uniformity.

3.2. ζ-Potential Measurements

The zeta potential of carbon materials is often investigated and is dependent on suspension acidity [32]. To ascertain the effect of the surface charge of the tested materials on their behavior in the electrochemical system for targeted dyes degradation, we have tested cZIF samples in 0.1 M KOH electrolyte dispersion. The values of ζ-potentials of all samples reveal that the charge of starting ZIF-67 (−26.5 mV) lowers to −20.7 mV for the composite sample cZIF800. The extended carbonization at 800 °C for 3 h only slightly lowers the negative charge to −19.3 mV. Interestingly, carbonization at a higher temperature of 900 °C increases the negative charge to −27.6 mV, surpassing the value measured for the parent ZIF-67 sample. Slight alterations in zeta potential arise from variations in the amount of thermally stable surface groups in the tested cZIF samples, as revealed by XPS analysis [13]. Their negative values of ζ-potential can be explained by the presence of acidic functional groups, such as –COOH and –OH, which dissociate in alkaline media to form negatively charged species (–COO–, –O–). Li et al. investigated the zeta potential of starch-derived carbons, acquiring a negative charge at high pH, which was also witnessed for the cZIFs in this study, resulting in increased interaction with MB [33].

3.3. Dye Adsorption

To establish the potential of physical remediation that precursor ZIF-67 and derived cZIFs offer, we first inspected their retention capacities for targeted dyes, MB and MO. It was reported that, for ZIF structures investigated for dye removal, the external surface was crucial for accomplished capacities since pore structure is not available for large molecules [34]. Here, a progressive enhancement in dye adsorption from the original ZIF-67 (maximum adsorption capacities 32 mg/g for MB, and 36 mg/g for MO) to its carbonized forms, cZIFs, which represent N-doped carbon/metallic Co/Co3O4 composites, is documented.

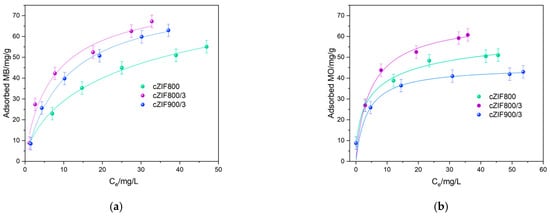

The adsorption isotherm data were fitted using the most appropriate models, namely Langmuir, Freundlich, and Langmuir–Freundlich. The Langmuir–Freundlich (LF) isotherm was the best-suited model to describe dye adsorption on cZIF samples (Figure 2). Different surface groups formed during ZIF-67 carbonization (such as C–O–C, O–C=O, C–OH, C=N, Co–O, N–Co) [13] offer a variety of adsorption sites, influencing surface heterogeneity, which is in accordance with literature findings on MB adsorption on activated carbons [35]. Composites cZIFs outperformed parent ZIF-67, despite its higher surface area and larger mesopore diameter [13]. The estimated MB monolayer content (from the LF isotherm model), qm, is similar among the tested cZIF samples, with the highest value found for cZIF800 (100 mg/g), followed by cZIF800/3 (80 mg/g), and cZIF900/3 (80 mg/g) (Table 1). The maximum experimentally determined adsorption capacity for MB amounts to 67, 63, and 55 mg/g for cZIF800/3, cZIF900/3, and cZIF800, respectively. Inspection of the adsorption isotherms indicates that it is evident that prolonged carbonization treatment yields a relatively high 1/n factor (the heterogeneity index), while monolayer capacity is not reached.

Figure 2.

Adsorption isotherms fitted using the LF model for (a) MB and (b) MO adsorption on cZIF samples.

Table 1.

Adsorption parameters derived from LF isotherms for MB and MO adsorption on cZIFs.

Similar results were seen for MO adsorption, with somewhat lower adsorption capacities, almost reaching estimated monolayer values. Lower adsorption capacity is combined with a slightly higher adsorption constant and matching heterogeneity, suggesting that ion–ion interaction is not a dominant retention mechanism. This finding points to accessible surface groups enabling hydrogen bonding with dye molecules regardless of their cationic/anionic nature. For MO adsorption, we also noticed an alteration in cZIF’s efficiency, since cZIF800/3 (61 mg/g) again outperformed cZIF800 (51 mg/g) and cZIF900/3 (43 mg/g), remaining the best adsorbent amongst cZIFs. The reason for the higher adsorption capacity of cZIF800/3 for both dye molecules may be due to its textural properties, whereby it displays the highest mesopore volume of 0.138 cm3/g [13] as compared to the other two samples—0.124 cm3/g (cZIF800) and 0.122 cm3/g (cZIF900/3). Zheng et al. showed that porosity and pore diameter are of the essence in accommodating MO molecules in carbonized ZIF-67 structures [17]. Generally, an open pore structure is essential for effective dye adsorption on carbon materials [36]. Mesopore diameter according to the B.J.H method goes from 18.1 nm (cZIF800), over 16.8 nm (cZIF800/3), to 15.1 nm (cZIF900/3) [13], all being larger than the diameter of MB (1.5 nm) and MO (6–8 nm) [37], allowing for significant adsorption capacities. The lower adsorption capacity of pristine ZIF-67 for both dyes points to the importance of active sites rather than the specific surface area or mesopore diameter in terms of governing the retention of dyes on pristine ZIF samples. For carbonized ZIF-67 materials, featuring N/Co-doped carbons, spacious porous structures govern acidic dye adsorption through pyrrolic/pyridinic N-sites [17]. A promising MB removal potential of 98% was also reported for hydrogel composited with biochar-decorated ZIF-67, with a 10 mg/L suspension [38]. Although doped carbons can achieve high adsorption capacities, complete pollutant elimination ultimately relies on electrodegradation as a part of an integrated removal strategy.

3.4. Electro-Assisted Dye Degradation

As remediation techniques require the complete degradation of pollutants, the intrinsic catalytic activity of cZIFs for the electrodegradation of dyes in basic conditions is tested. Oxygen reduction reaction electrocatalysis by tested cZIF composites was assessed in our previous publication [13], and it was found to be diffusion-controlled at the electrode potential applied in this work. The oxygen reduction mechanism includes the formation of relatively short-lived, highly reactive species O2•− and •OH [39] at or near the electrode surface, which are known to be efficient in organic pollutant removal [39]. Therefore, the amperometric method was used for the generation of highly reactive radical species and to assess the potential of cZIFs for MB/MO degradation/removal. Koutecký–Levich (K-L) analysis revealed the apparent number of exchanged electrons per oxygen molecule to be above three in the whole potential range [13], indicating a mix of 2e−/4e− reduction pathways, ensuring the formation of reactive oxygen species [40].

Predominant removal techniques in the literature include the electrooxidation of MB via the OH• radical species generated at the anode side through water decomposition at high overpotentials. The reported decomposition can reach over 86% of MB (10 mg/L) when the high voltage of 9 V is applied to the fly ash–red mud electrode [41]. Electrooxidation degradation on flexible graphite electrodes was studied by Goren et al. [12] who reported complete MB removal (26.5 mg/L) at pH 4, with an applied potential of 3 V. However, little attention is paid to the cathode degradation option where oxygen is reduced to form the same reactive radical species but at significantly lower overpotential and without excessive bubble formation characteristic of high current electrooxidation processes.

It is expected that the cathodically formed reactive oxygen species will participate in the chemical degradation of MB, where in alkaline and alkaline/peroxide systems [29], O2•− nucleophiles can degrade phenothiazine derivatives, and electro-generated O2•− may be employed for the degradation of different pollutants [39].

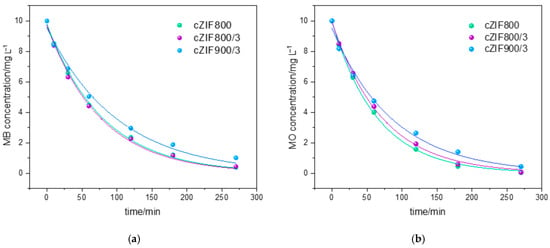

The degradation of MB on cZIF composites studied here follows pseudo-first-order kinetics (Figure 3a) with calculated rate constants of the same order, from (0.013 ± 0.001) min−1 for cZIF800/3 and (0.0125 ± 0.0004) min−1 for cZIF800 to (0.010 ± 0.001) min−1 for cZIF900/3. It is important to note that MB can be reversibly reduced to a colorless leuco-MB form [42], or undergo nucleophile demethylation [29,30]. Without a detected increase in the intensity of the UV absorption band at 255 nm attributed to leuco-MB evolution, we can conclude that all dye molecules were degraded by electro-generated O2•− and/or •OH radicals [43]. The inherent degradation of MB in KOH (without an electrode present) was assessed in a separate measurement and accounted for a 23% MB decrement after 4.5 h. The individual contributions of the electrochemical system, i.e., alkaline hydrolysis, mixing, and electrochemical degradation, were systematically evaluated previously [9]. Approximately two-thirds of the total MB removal originates from electrochemical degradation. Thus, the observed dye removal is predominantly due to electrochemical processes rather than adsorption.

Figure 3.

Electrooxidation/electrodegradation kinetics for (a) MB and (b) MO dyes using cZIF electrodes.

One possible reaction pathway for MO degradation involves the oxidation of MO by the hydroperoxyl radical to form intermediates through the cleavage of the azo bond (–N=N–) present at high pH, as witnessed in foto/sono degradation [44], while another route involves direct reduction in the azo group by the hydroperoxyl radical.

In our system, electro-assisted degradation of MO on cZIF electrodes follows pseudo-first-order kinetics (Figure 3b) with calculated rate constants lowering from (0.0155 ± 0.0003) min−1 for cZIF800 and (0.0140 ± 0.0004) min−1 for cZIF800/3h, to (0.0115 ± 0.0008) min−1 for cZIF900/3h. Ma et al. [45] recently showed that Co, Fe, and Co/Fe@PorousCarbon, obtained by the carbonization of the MIL-101(Fe, Co) precursor, can achieve 98% degradation of MO under a high current of 60 mA through OH• radical formation. Similarly, Bai et al. [46] put forward Cu-Co3O4@C, obtained by ZIF-67 calcination, as a highly active electrode for the degradation of organic pollutants (including MO) through the formation of hydroxyl, superoxide anion radical, and/or singlet oxygen. The same reactive species are responsible for the degradation of MO on other electrode materials like Ti4O7, with removal below 92% for 10 mA/cm2 current density and 100 mg/L dye concentration [47] for PbO2/Ti in an active carbon-packed electrode reactor (complete mineralization of MO) [48] and fluidized bed electrochemical oxidation on activated carbon [49]. Our tested system offers a significant advantage due to the significantly lower potential applied and current density of 3 mA/cm2, which minimizes energy consumption while maintaining high efficiency and 99% removal.

From Figure 3, it can be seen that cZIF900/3 behaves worse as an electrode material in the degradation of both dyes compared to the other two materials synthesized at a lower temperature, cZIF800/3 and cZIF800. This is based on the XPS surface composition data of the studied cZIFs [13] and findings that increased Co2+/Co3+ surface ratio in Co3O4-containing carbon materials is favorable for ORR due to the formation of oxygen vacancies on the Co3O4 surface, which promotes O2 adsorption and electron transfer [50]. The better electrocatalytic behavior of cZIF800/3 and cZIF800 in the degradation of MB and MO can be explained by a significantly higher Co2+/Co3+ surface ratio compared to cZIF900/3. In addition, materials produced at 800 °C possess suitable textural properties (specific surface area) and the surface content of functional groups, such as C–O–C, Co–N and Co–O, serving as efficient active centers for ORR [13].

3.5. FTIR Analysis of the Electrodes

The vibrational FTIR and Raman spectral features of prepared cZIFs are discussed in detail in our previous contribution [13]. Namely, prolonged thermal treatment results in the evolution of bands due to Co-O stretching vibrations (668 and 568 cm−1) bands seen in FTIR spectra for cZIF800/3 and cZIF900/3. The resulting metal oxide moiety thus offers significant heterogeneous active sites for adsorption and catalysis [13].

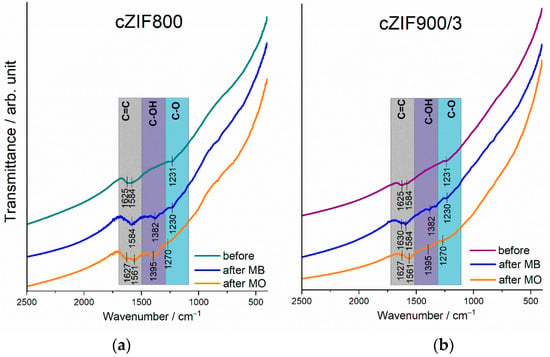

Here, we employed FTIR spectroscopy to inspect the surface groups on the electrodes prior to and after the reaction in the MO(MB)/KOH solution (Figure 4). In the region 2500–500 cm−1, in addition to the existing bands of cZIFs at 1584 and 1231 cm−1, which is attributable to C=C and C-O vibrations, respectively, an evolution of new vibrational bands is evidenced for both cZIF800 and cZIF900/3 electrodes after electrochemical treatment in dye solution at 1385/1395 cm−1 (O–H deformation vibration), arising from basic electrolyte and ORR introducing C–OH functionalities [51]. Additional changes are observed in the region of C=C/C=N stretching vibrations, where distinct sharp peaks appear (e.g., for the MO case, the peaks at 1627 and 1561 cm−1 for cZIF800 and the peak at 1561cm−1, with a low intensity band at 1627 cm−1 for cZIF900/3), which is most probably due to the bound products of dye degradation. The increased polarity of the surface may induce additional electrostatic interaction, preferentially hydrogen bonding between hydroxyls and MB/MO nitrogen functionalities.

Figure 4.

FTIR spectra of (a) cZIF800 and (b) cZIF900/3 electrodes before and after CA experiments to assess the electrooxidation of MB and MO.

3.6. Electrodegradation Efficiency

All samples degraded up to 96% of MB and 99% of MO after 4.5 h; therefore, to assess their activity, we studied closely the degradation within the first hour. Here, we propose a calculation of the current conversion efficiency index (φ in MC mol−1), which represents the amount of charge associated with O2•−/•OH generation, normalized by the quantity of removed dye, i.e., charge needed to remove one mole of the initial dye. The lowest values of φ for MB degradation were found for cZIF800 (0.65; 1.08; 1.73) after 10, 30, and 60 min, respectively, which puts cZIF800 as the most active catalyst for degradation since it needs the least amount of energy to degrade 1 mol of MB and does so quickly. The sample cZIF800 is followed by cZIF800/3 and cZIF900/3, with φ values of 0.81, 1.20, 1.78, and 1.06, 1.59, 2.10, respectively. If we assume a one-electron process for the generation of a reactive species, based on Faraday laws, 7.75 × 10−6 mol of O2•−/•OH is generated. Using the calculated amount of radical species, 9.28 × 10−7 mol of MB is degraded, corresponding to around nine reactive species needed to attack one MB molecule. This makes sense as with a low initial pollutant concentration (10 ppm), some reactive species are converted to OH− before they can react with dye molecules and initiate degradation. Results also suggest that dye molecules need to be near the surface where reactive species are formed to start the degradation. All studied samples generate enough reactive species; however, the difference lies in their specific surface area (SSA), with cZIF800 having 265 m2/g, cZIF800/3 238 m2/g, and cZIF900/3 197 m2/g. SSA follows the same trend as their activity for MB, pointing towards the fact that the process of MB degradation on these materials is a surface-determined one and can be an explanation for cZIF800 being the most active. Additionally, the loss of protons by the MB molecule in the alkaline electrolyte [52] prevents the irreversible retention of MB at the electrode surface, which could block active sites for the ORR process.

Electrochemical degradation of MO follows a similar pattern to MB degradation, even though the dye is anionic. Sample cZIF800 is the most active with the lowest φ values (0.14; 0.14; 0.12) while samples cZIF800/3 (0.21; 0.16; 0.15) and cZIF900/3 (0.12; 0.15; 0.15) follow each other closely with respect to degradation efficacy. Again, textural properties seem to be key factors determining the activity of the studied materials. When we calculate the amount of charge spent on reactive species generation, we obtain 142 reactive species generated per degraded MO molecule for the most active cZIF800. We can conclude that all studied materials can degrade both MB and MO almost completely in 4.5 h, with MB degradation reaching 96% while MO reaches 99% in the same timeframe. However, the energy needed for degradation, per molecule of MB, is ~16 times less than the energy needed to degrade MO molecules, making these materials more efficient in MB degradation, compared to MO, by electrochemical means. The reason may be seen in the higher repulsion of the anionic MO dye and negatively polarized electrode, hindering surface-guided electrodegradation. A comparison of literature data on degradation efficiency, considering energy consumption, is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparative table on dye degradation efficiency and energy consumption in electrochemical treatment.

Comparative charge-based analysis reveals that MB degradation is inherently more electrochemically efficient than MO degradation, requiring up to four orders of magnitude less electrical charge for comparable removal efficiencies. Herein, we highlight the proposed convenient way to calculate the efficacy of a degradation procedure. Motivation comes from many researchers in the field, often reporting complete or almost total degradation without the data on energy spent on the degradation itself, which essentially conceals how “green” the removal procedure is. This way, the descriptor “energy efficacy” can be introduced to compare different materials easily.

4. Conclusions

N-doped carbon/Co/Co3O4 composites, cZIFs, were prepared by the carbonization of ZIF-67 at 800 and 900 °C and tested as materials for degrading organic dyes in water. Thermal treatment affected particle sizes, measured by the Nanoparticle Tracking Analyzer, with a mean diameter ranging from 122 nm for parent ZIF-67 to 130–148 nm for derived cZIFs. All samples exhibited negative surface charges, with the lowest values of zeta potential recorded for the sample synthesized by heating at 800 °C for 3 h (−19.3 mV), while carbonization at 900 °C for 3 h resulted in −27.6 mV zeta potential. The environmental applicability of these materials was tested through the adsorption and electro-assisted degradation of cationic methylene blue (MB) and anionic methyl orange (MO) dyes. Dye adsorption increased from ZIF-67 (32 mg/g MB and 36 mg/g MO) to its carbonized forms, with maximum adsorption capacities for MB/MO recorded as 55/51 mg/g (ZIF-67 heating up to 800 °C), 67/61 mg/g (ZIF-67 carbonization at 800 °C for 3 h), and 63/43 mg/g (ZIF-67 carbonization at 900 °C for 3 h). For complete pollutant degradation, cZIFs were used in dye electrochemical degradation under alkaline conditions, serving as electrode materials. The oxygen reduction reaction produced highly reactive species O2•− and •OH, and the electrodegradation of both dyes followed pseudo-first-order kinetics, achieving 96% MB and 99% MO degradation in 4.5 h for 10 mg/L dye loading. FTIR profiles of cZIF electrodes before and after the reaction in dye solution showed the evolution of vibrational bands attributed to introduced C–OH functionalities from the KOH electrolyte solution and ORR, as well as to the binding of dye degradation products.

We propose the calculation of the current conversion efficiency index (φ in MC/mol) as the amount of charge associated with reactive species generation needed to remove one mole of the dye. The lowest values of φ for both dye molecules degradation were found for the ZIF-67 sample, heating up to 800 °C. Based on this parameter, the energy needed for degradation, per molecule of MB, is ~16 times less than the energy needed to degrade an MO molecule. The higher repulsion between an anionic MO dye and a negatively polarized electrode hinders surface-guided electrodegradation due to an increase in electrostatic repulsion. The φ index differentiates among different ZIF-derived composites as promising candidates for environmentally sustainable and complete remediation of dye-contaminated waters.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.-R., N.G. and G.Ć.-M.; methodology, M.R. and A.J.L.; validation, G.Ć.-M.; formal analysis, M.R., A.J., D.B.-B. and A.J.L.; investigation, M.R., A.R., A.J. and N.G.; data curation, M.R. and A.J.; writing—original draft preparation, N.G., M.R., M.M.-R. and D.B.-B.; writing—review and editing, M.M.-R. and G.Ć.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Science Fund of the Republic of Serbia, Grant No. 7750219 Advanced Conducting Polymer-Based Materials for Electrochemical Energy Conversion and Storage, Sensors and Environmental Protection–AdConPolyMat (IDEAS program) and by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia (Contract No. 451-03-137/2025-03/200146, 451-03-136/2025-03/200146 and 51-03-136/2025-03/200161).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Escobar-Teran, F.; Perrot, H.; Sel, O. Carbon-Based Materials for Energy Storage Devices: Types and Characterization Techniques. Physchem 2023, 3, 355–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, L.; Wen, H.; Shen, R.; Zhang, H.; Guo, X.; Jiang, J.; Li, B. Review and Perspectives on Carbon-Based Electrocatalysts for the Production of H2O2 via Two-Electron Oxygen Reduction. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 9501–9542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinath, K.P.; Vo, D.-V.N.; Gnana Prakash, D.; Adithya Joseph, A.; Viswanathan, S.; Arun, J. Environmental Applications of Carbon-Based Materials: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 557–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popadić, D.; Krstić, J.; Janošević Ležaić, A.; Popović, M.; Milojević-Rakić, M.; Ignjatović, L.; Bajuk-Bogdanović, D.; Gavrilov, N. Acetamiprid’s Degradation Products and Mechanism: Part II—Inert Atmosphere and Charge Storage. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 308, 123772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupar, J.; Hrnjić, A.; Uskoković-Marković, S.; Bajuk-Bogdanović, D.; Milojević-Rakić, M.; Gavrilov, N.; Janošević Ležaić, A. Electrochemical Crosslinking of Alginate—Towards Doped Carbons for Oxygen Reduction. Polymers 2023, 15, 3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupar, J.; Bajuk-Bogdanović, D.; Milojević-Rakić, M.; Krstić, J.; Upadhyay, K.; Gavrilov, N.; Janošević Ležaić, A. Tailored Porosity Development in Carbons via Zn2+ Monodispersion: Fitting Supercapacitors. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2022, 335, 111790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Ren, D.; Wang, S.; Zhang, M.; Sun, Y.; Sun, S.; Huo, Z.; Zhang, N. Carbon Materials in Electrocatalytic Oxidation Systems for the Treatment of Organic Pollutants in Wastewater: A Review. Carbon Resour. Convers. 2023, 6, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thamaraiselvan, C.; Bandyopadhyay, D.; Powell, C.D.; Arnusch, C.J. Electrochemical Degradation of Emerging Pollutants via Laser-Induced Graphene Electrodes. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2021, 8, 100195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popadić, D.; Gavrilov, N.; Ignjatović, L.; Krajišnik, D.; Mentus, S.; Milojević-Rakić, M.; Bajuk-Bogdanović, D. How to Obtain Maximum Environmental Applicability from Natural Silicates. Catalysts 2022, 12, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Adhikary, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Roy, D.; Chatterjee, S.; Chakraborty, A.; Banerjee, D.; Ganguly, A.; Nanda, S.; Rajak, P. Contamination of Textile Dyes in Aquatic Environment: Adverse Impacts on Aquatic Ecosystem and Human Health, and Its Management Using Bioremediation. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 353, 120103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milojević, M.; Dondur, V.; Damjanović, L.; Rakić, V.; Rajić, N.; Ristić, A. The Activity of Iron-Containing Zeolitic Materials for the Catalytic Oxidation in Aqueous Solutions. Mater. Sci. Forum 2007, 555, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goren, A.Y.; Recepoğlu, Y.K.; Edebali, Ö.; Sahin, C.; Genisoglu, M.; Okten, H.E. Electrochemical Degradation of Methylene Blue by a Flexible Graphite Electrode: Techno-Economic Evaluation. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 32640–32652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranković, M.; Janošević Ležaić, A.; Gavrilov, N.; Pašti, I.; Bajuk-Bogdanović, D.; Vasiljević, B.N.; Savić, M.; Krstić, J.; Ćirić-Marjanović, G. Novel N-Doped Carbon/Co/Co3O4 Ternary Composites Derived by Direct Carbonization of ZIF-67: Efficient Electrocatalysts for Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2026, 348, 131530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayathiri, M.; Pulingam, T.; Lee, K.T.; Sudesh, K. Activated Carbon from Biomass Waste Precursors: Factors Affecting Production and Adsorption Mechanism. Chemosphere 2022, 294, 133764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milojević-Rakić, M.; Bajuk-Bogdanović, D. (Eds.) Zeolites and Porous Materials: Insight into Catalysis and Adsorption Processes; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2023; ISBN 978-3-0365-8155-2. [Google Scholar]

- Chaikittisilp, W.; Ariga, K.; Yamauchi, Y. A New Family of Carbon Materials: Synthesis of MOF-Derived Nanoporous Carbons and Their Promising Applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Liu, Q.; Wang, F. In-Situ Carbonization of ZIF-67 to Fabricate Magnetically Co/N-MC with High Adsorption Capacity toward Water Remediation. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Khan, U.A.; Iqbal, N.; Noor, T. Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework (ZIF)-Derived Porous Carbon Materials for Supercapacitors: An Overview. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 43733–43750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oturan, M.A.; Brillas, E. Electrochemical Advanced Oxidation Processes (EAOPs) for Environmental Applications. Port. Electrochim. Acta 2007, 25, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Sánchez, C.; Robles, I.; Godínez, L.A. Review of Recent Developments in Electrochemical Advanced Oxidation Processes: Application to Remove Dyes, Pharmaceuticals, and Pesticides. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 12611–12678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameta, R.; Chohadia, A.K.; Jain, A.; Punjabi, P.B. Fenton and Photo-Fenton Processes. In Advanced Oxidation Processes for Waste Water Treatment; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 49–87. [Google Scholar]

- Isaev, A.B.; Shabanov, N.S.; Magomedova, A.G.; Nidheesh, P.V.; Oturan, M.A. Electrochemical Oxidation of Azo Dyes in Water: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 2863–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Dong, H.; Liu, K.; Zheng, Y.; Hoffmann, M.R.; Liu, W. Porous Carbon Monoliths for Electrochemical Removal of Aqueous Herbicides by “One-Stop” Catalysis of Oxygen Reduction and H2O2 Activation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 414, 125592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, P.; Zhou, M.; Song, G.; Du, X.; Lu, X. Efficient H2O2 Generation and Spontaneous OH Conversion for In-Situ Phenol Degradation on Nitrogen-Doped Graphene: Pyrolysis Temperature Regulation and Catalyst Regeneration Mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 397, 122681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Zhao, K.; Quan, X.; Cao, P.; Chen, S.; Yu, H. Highly Efficient Metal-Free Electro-Fenton Degradation of Organic Contaminants on a Bifunctional Catalyst. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 416, 125859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Su, H.; Chen, Z.; Yu, H.; Yu, H. Fabrication of Electrochemically Reduced Graphene Oxide Modified Gas Diffusion Electrode for In-Situ Electrochemical Advanced Oxidation Process under Mild Conditions. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 222, 1501–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-Z. Avoiding Spurious Correlation in Analysis of Chemical Kinetic Data. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 6861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, R.; Najeeb, J.; Sattar, A.; Naseem, K.; Irfan, A.; Al-Sehemi, A.G.; Farooqi, Z.H. Chemical Reduction of Methylene Blue in the Presence of Nanocatalysts: A Critical Review. Rev. Chem. Eng. 2020, 36, 749–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katafias, A.; Lipińska, M.; Strutyński, K. Alkaline Hydrogen Peroxide as a Degradation Agent of Methylene Blue—Kinetic and Mechanistic Studies. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2010, 101, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamčíková, L.; Pavlíková, K.; Ševčík, P. The Decay of Methylene Blue in Alkaline Solution. React. Kinet. Catal. Lett. 2000, 69, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jevremović, A.; Savić, M.; Janošević Ležaić, A.; Krstić, J.; Gavrilov, N.; Bajuk-Bogdanović, D.; Milojević-Rakić, M.; Ćirić-Marjanović, G. Environmental Potential of Carbonized MOF-5/PANI Composites for Pesticide, Dye, and Metal Cations—Can They Actually Retain Them All? Polymers 2023, 15, 4349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Lotina, A.; Portela, R.; Baeza, P.; Alcolea-Rodriguez, V.; Villarroel, M.; Ávila, P. Zeta Potential as a Tool for Functional Materials Development. Catal. Today 2023, 423, 113862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Budarin, V.L.; Clark, J.H.; North, M.; Wu, X. Rapid and Efficient Adsorption of Methylene Blue Dye from Aqueous Solution by Hierarchically Porous, Activated Starbons®: Mechanism and Porosity Dependence. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 436, 129174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelhamid, H.N. Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Dyes Using ZIF-67. Surf. Interfaces 2025, 73, 107580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Jery, A.; Alawamleh, H.S.K.; Sami, M.H.; Abbas, H.A.; Sammen, S.S.; Ahsan, A.; Imteaz, M.A.; Shanableh, A.; Shafiquzzaman, M.; Osman, H.; et al. Isotherms, Kinetics and Thermodynamic Mechanism of Methylene Blue Dye Adsorption on Synthesized Activated Carbon. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Guo, Z.; Ling, H.; Huang, Z.; Tang, D. Effect of Pore Structure on the Adsorption of Aqueous Dyes to Ordered Mesoporous Carbons. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2016, 227, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Liu, X.; Lv, G.; Zhu, R.; Tian, L.; Liu, M.; Li, Y.; Rao, W.; Liu, T.; Liao, L. Study on the Adsorption Properties of Methyl Orange by Natural One-Dimensional Nano-Mineral Materials with Different Structures. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peighambardoust, S.J.; Rezaei-Aghdam, S.; Sakhaei Niroumand, J.; Mohammadzadeh Pakdel, P.; Sillanpää, M. Efficient Methylene Blue Elimination from Water Media by Nanocomposite Adsorbent-Based Carboxymethyl Cellulose-Grafted Poly(Acrylamide)/Magnetic Biochar Decorated with ZIF-67. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 32407–32423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Huitle, C.A.; Rodrigo, M.A.; Sirés, I.; Scialdone, O. A Critical Review on Latest Innovations and Future Challenges of Electrochemical Technology for the Abatement of Organics in Water. Appl. Catal. B 2023, 328, 122430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Sumboja, A.; Wuu, D.; An, T.; Li, B.; Goh, F.W.T.; Hor, T.S.A.; Zong, Y.; Liu, Z. Oxygen Reduction in Alkaline Media: From Mechanisms to Recent Advances of Catalysts. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 4643–4667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, X.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Wei, Z.; Chen, C.; Du, K.; Zhao, C.; Yang, G.; Li, Y. Performance and Mechanism of Methylene Blue Degradation by an Electrochemical Process. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 24712–24720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, R.; Song, S.; Liu, Y.; Dong, S. Mechanisms of Methylene Blue Electrode Processes Studied by in Situ Electron Paramagnetic Resonance and Ultraviolet–Visible Spectroelectrochemistry. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1990, 86, 3125–3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegu, R.; Majumdar, K.J.; Talukdar, D.J.; Pratihar, S. Oxalate Capped Iron Nanomaterial: From Methylene Blue Degradation to Bis(Indolyl)Methane Synthesis. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 33446–33456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadzil, N.A.M.; Zainal, Z.; Abdullah, A.H. Ozone-Assisted Decolorization of Methyl Orange via Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Photocatalysis. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2012, 7, 11993–12003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Cui, S.; Zhang, J.; Huang, W.; Wang, Y. Efficient Degradation of Methyl Orange with Fe/Co@PC Particle Electrodes in a Three Dimensional Electrochemical Reactor: Performance and Mechanism. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 69, 106765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Gong, Z.; Yu, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, S. Dendritic Cu–Co3O4 with Elevated Oxygen Vacancies for the Degradation of Organic Pollutants. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2025, 8, 23288–23299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Liu, Y.; Ye, J.; Lin, Z.; Yang, X. Electrochemical Oxidation of Methyl Orange by a Magnéli Phase Ti4O7 Anode. Chemosphere 2020, 241, 125084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Li, X.; Yan, Y.; Wang, L. Electrochemical Oxidation of Methyl Orange in an Active Carbon Packed Electrode Reactor (ACPER): Degradation Performance and Kinetic Simulation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, Z.; Du, W.; Liu, P.; Zhang, L.; Shi, F. Treatment of Wastewater Containing Methyl Orange Dye by Fluidized Three Dimensional Electrochemical Oxidation Process Integrated with Chemical Oxidation and Adsorption. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 311, 114775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, J.; Dai, Y.; Li, X.; Shao, C.; Sun, Y.; Wang, R.; Zou, J. Co3O4@carbon with High Co2+/Co3+ Ratios Derived from ZIF-67 Supported on N-Doped Carbon Nanospheres as Stable Bifunctional Oxygen Catalysts. Mater. Today Energy 2021, 21, 100737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, Z.; Bajuk-Bogdanović, D.; Jovanović, S.; Mravik, Ž.; Kovač, J.; Holclajtner-Antunović, I.; Vujković, M. The Role of Surface Chemistry in the Charge Storage Properties of Graphene Oxide. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 258, 1228–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saputra, E.; Saputra, R.; Nugraha, M.W.; Irianty, R.S.; Utama, P.S. Removal of Methylene Blue from Aqueous Solution Using Spent Bleaching Earth. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 345, 012008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Chu, Z.; Zhou, J.; Wang, G.; Zhu, M. Electrochemical Efficient Degradation of Methylene Blue (MB) by Two-Step Electrodeposited Ti/TiO2-NTs/β-PbO2 Electrode: Performance, Degradation Mechanism, and Toxicity Study of Intermediate Products. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 307, 119419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.