1. Introduction

Process monitoring is a crucial means to ensure the stable and safe operation of industrial processes [

1]. With the accumulation of massive production data in distributed control systems, data-driven process monitoring methods have been extensively developed and applied. Multivariate Statistical Process Monitoring (MSPM) has attracted considerable attention due to its low dependence on prior process knowledge and ease of implementation.

Currently, MSPM mainly includes principal component analysis (PCA), partial least squares (PLS), independent component analysis (ICA), and so on [

2]. These methods typically operate by projecting high-dimensional process data into a low-dimensional feature space that preserves most of the original information [

3]. Within this low-dimensional space, the distribution of normal operating conditions can be characterized by certain statistics, for example, the Hotelling’s

statistic [

4,

5], thus enabling effective fault detection. Most MSPM methods assume that the process operates under a predefined normal and stable condition, which means that the process variables are stationary [

6]. However, in large-scale and complex chemical processes, due to factors such as equipment aging, planned operational adjustments, and external disturbances, non-stationary variables commonly exist [

7], posing significant challenges to the monitoring performance of traditional MSPM methods. The primary idea to implement non-stationary process monitoring is to eliminate the non-stationary trends by preprocessing and then establish models [

8], in which a common approach is to conduct the transform of difference. Time series in general industrial processes can be converted to stationary by differencing at most twice [

9], by which the seasonality, cyclicality, or other forms of non-stationary characteristics can be removed. However, the dynamic information of the process may be lost during the differencing, which could compromise the monitoring effect [

10]. Model adaptive updating strategies are also applied to solve the non-stationary problems, where the model structure and parameters are continuously updated. However, the update nodes of the model are difficult to determine because faults and non-stationary trends are difficult to distinguish, and if the model is updated with fault data, it will compromise the effectiveness of monitoring.

In addition to these methods, the long-term equilibrium relationship analysis is considered an effective approach. Its core idea is to extract stable collaborative relationships from non-stationary variables. The cointegration analysis (CA), originally developed for economic variable analysis [

11,

12], was introduced to monitor the non-stationary. Zhao et al. [

13] proposed a sparse cointegration analysis (SCA) based total variable decomposition and distributed modeling algorithm to fully explore the underlying non-stationary variable relationships. Hu et al. [

14] proposed a dual cointegration analysis for common and specific non-stationary fault variations diagnosis.

The stationary subspace analysis (SSA), first proposed by Bunau et al. [

15], as another long-term equilibrium relationship analysis method, aims to separate stationary and non-stationary sources from mixed signals. By using the stationary components to build monitoring models, SSA enables effective monitoring of non-stationary processes. Wu [

16] considered the dynamic characteristics of the non-stationary process and proposed dynamic stationary subspace analysis (DSSA). The time shift technique is introduced to model dynamic relationships and the Mahalanobis distance is adopted for monitoring stationary components of augmented data. The results of three cases demonstrated the performance of DSSA. Chen [

17] developed an exponential analytic stationary subspace analysis (EASSA) algorithm to estimate the stationary sources more accurately and numerically stably. Two cases studied demonstrated that the real faults could be distinguished from normal changes.

In large-scale chemical processes, non-stationary variables induced by equipment aging, operational adjustments, and external disturbances present a critical challenge for reliable process monitoring. Traditional non-stationary process monitoring methods predominantly emphasize the modeling of stationary features, while often overlooking fault relevant information hidden within the non-stationary subspace. This limitation arises from the inherent monitoring design of traditional SSA, which exclusively focus on extracting stationary components. Consequently, potential fault signatures, such as gradual drifts, oscillatory behaviors, or dynamic anomalies, embedded in non-stationary components are frequently discarded. This omission compromises monitoring sensitivity and leads to increased missed detection rates in practical applications.

Autoencoders (AE), as typical deep learning models, have demonstrated strong feature extraction capabilities through their encoder-decoder structure [

18]. Their basic principle is to minimize the error between the input and the reconstructed data, thereby learning latent features that effectively represent the input. The stacked autoencoders (SAE) are formed by stacking multiple autoencoders layer by layer, with each hidden representation serving as the input to the next encoder [

19]. Through multi-layer nonlinear mappings, SAE can gradually extract higher-order features, making them well-suited to capture complex relationships in non-stationary process data.

Motivated by these considerations, this study proposes a hybrid process monitoring framework that integrates SSA and SAE to jointly exploit information from both stationary and non-stationary subspaces. Specifically, SSA was first applied to decompose process data into stationary and non-stationary components. In the stationary subspace, conventional monitoring statistics were constructed to capture stationary variations. In the non-stationary subspace, SAE is employed to learn deep latent features, and the reconstruction error is used as monitoring statistics, thereby retaining fault relevant dynamic information that would otherwise be ignored. To achieve unified decision-making, Support Vector Data Description (SVDD) [

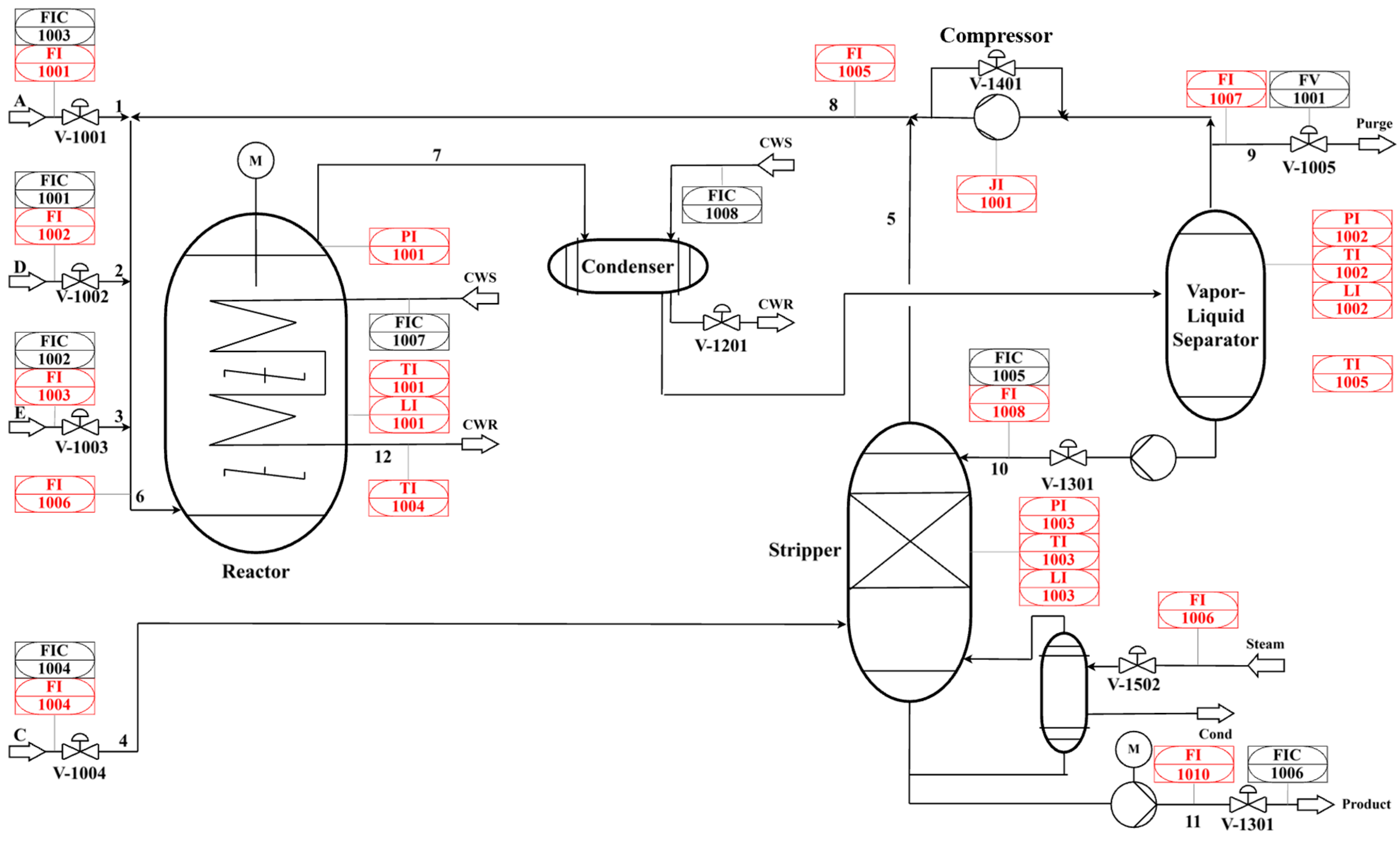

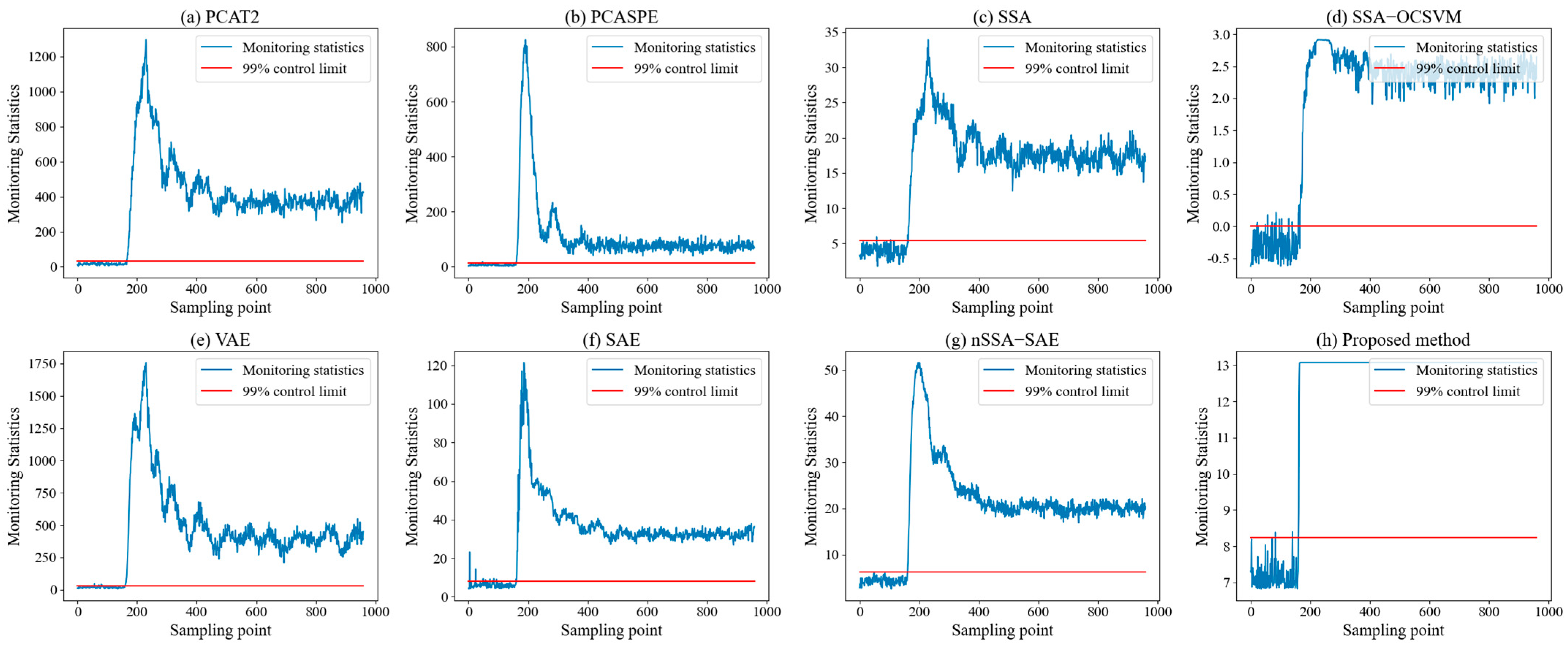

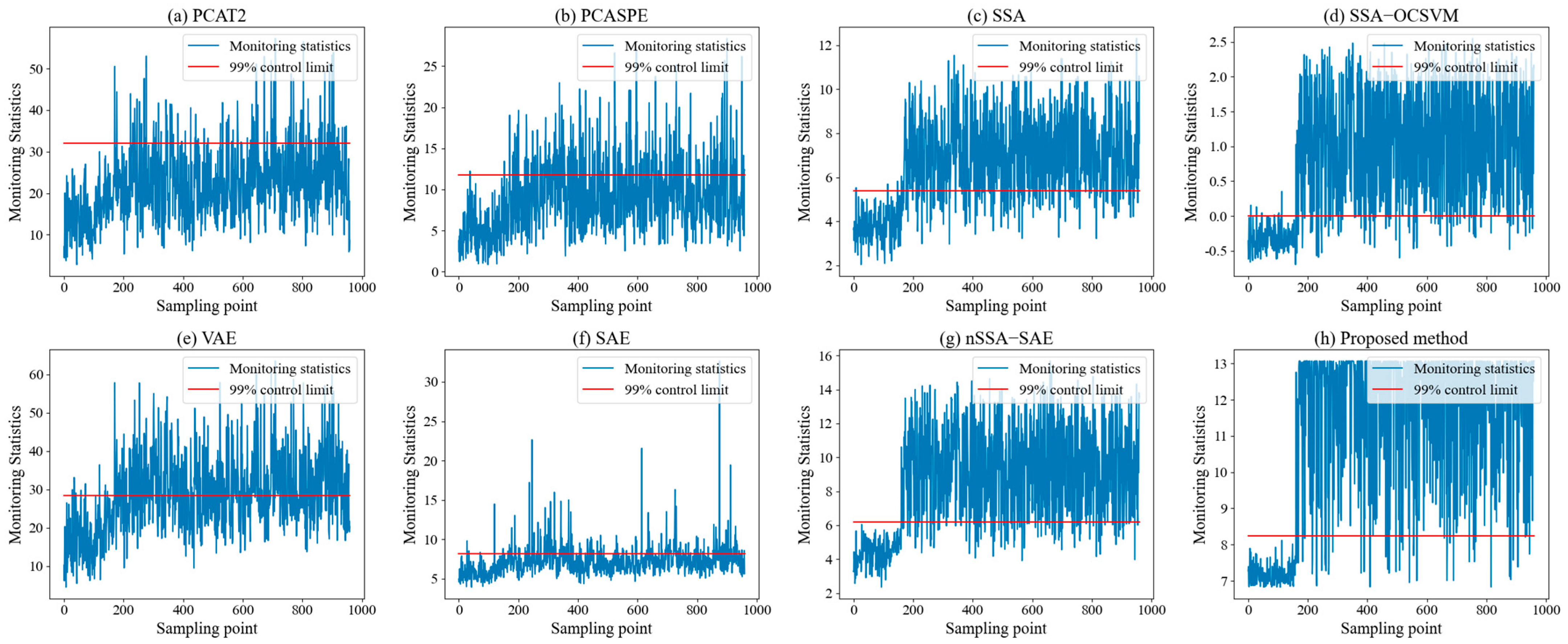

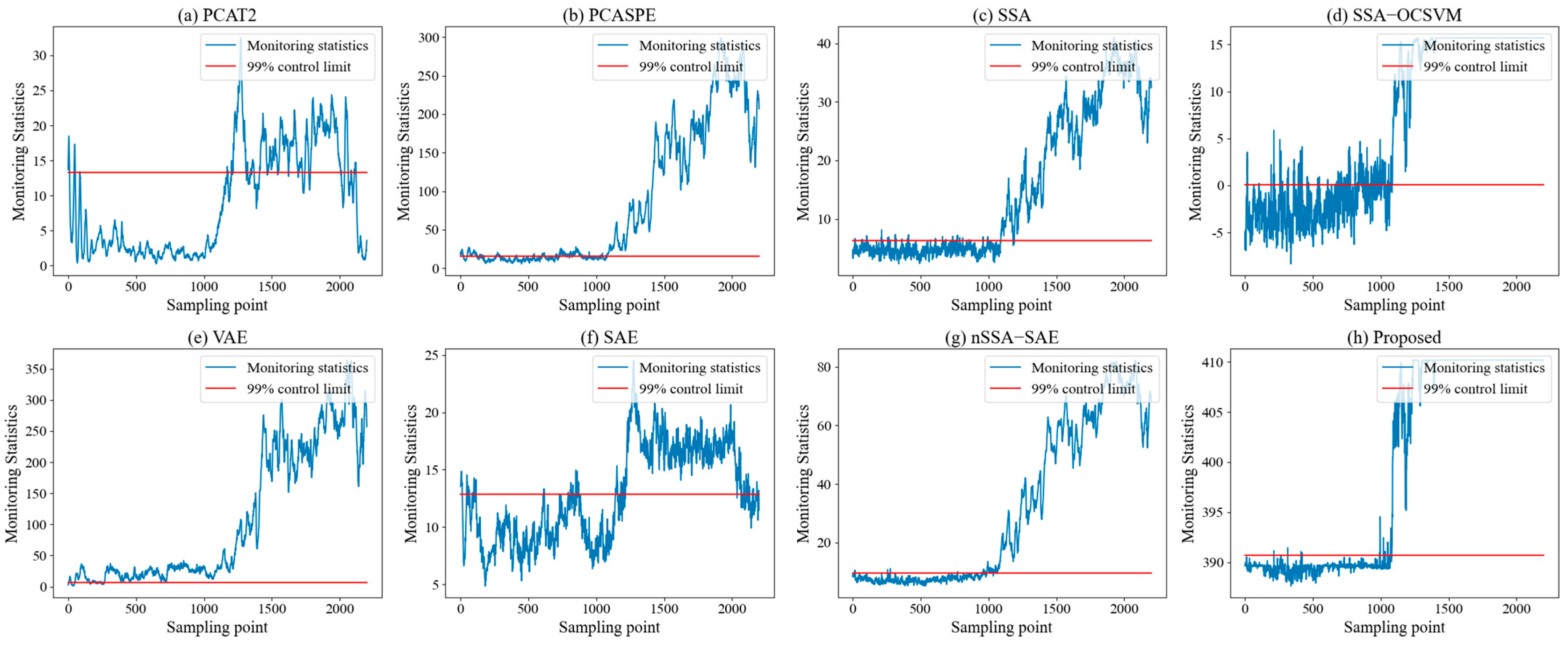

20] was then adopted to fuse the monitoring statistics from both subspaces. SVDD provides a powerful one-class classification framework that encloses normal operating data within a hypersphere in feature space, allowing effective discrimination between normal and abnormal conditions. This integration not only enhances sensitivity to both steady-state and dynamic faults but also improves robustness against process non-stationarity. The proposed framework was validated on the benchmark Tennessee Eastman (TE) and two industrial processes. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed framework significantly outperformed conventional SSA and some deep learning-based monitoring methods, offering superior detection accuracy, lower false alarm rates.

2. Theory and Methods

2.1. Stationary Subspace Analysis

SSA is a blind source separation approach that factorizes the observed signal

into stationary and non-stationary source based on the Equation (1) as follows:

where

is an invertible matrix.

and

are stationary and non-stationary sources, respectively. The goal of SSA is to separate the stationary sources and non-stationary sources by estimating a separation matrix ad the following:

where

and

are the stationary and non-stationary projection matrices.

The process data were first divided into consecutive and nonoverlapping epochs, . For any projection matrix , it was possible to obtain the mean and covariance matrix of stationary sources in each epoch, thus obtaining the distribution .

The distance between the stationary sources and the standard normal distribution was calculated in each epoch, which was measured by the Kullback–Leibler divergence

.

were summed over each epoch to construct an objective function as follows:

Equation (4) corresponds to the following optimization objective:

The problem is usually solved by the gradient descend method to obtain the optimal stationary projection matrix and stationary sources .

2.2. Stacked Autoencoder

The structure of the autoencoder is divided into two parts, the encoder and the decoder, for input data

, the encoder maps it to the hidden layer of the following form:

where

is the hidden layer features,

is the encoder layer weights,

is the bias vector, and

is the activation function. The decoder reconstructs the hidden layer features to obtain the reconstructed data

with the loss function as the following:

Stacked autoencoders, on the other hand, were obtained by stacking and combining multiple autoencoders, where the current hidden layer features were used as inputs to the next layer of encoders.

2.3. Support Vector Data Description

The goal of the support vector data description is to find a hypersphere region of minimum size , thus including all the training objects, and when a sample point falls outside the region, the sample can be considered as an anomaly.

Its optimization problem can be formulated as follows:

The radius of the hypersphere was calculated through nonlinear mapping by kernel function

as the following:

The Gaussian kernel function is employed as the following:

For a new sample

, the distance

to the center of the hypersphere region can be calculated using the following equation:

If , it is considered that a fault may have occurred.

2.4. Proposed Monitoring Strategy

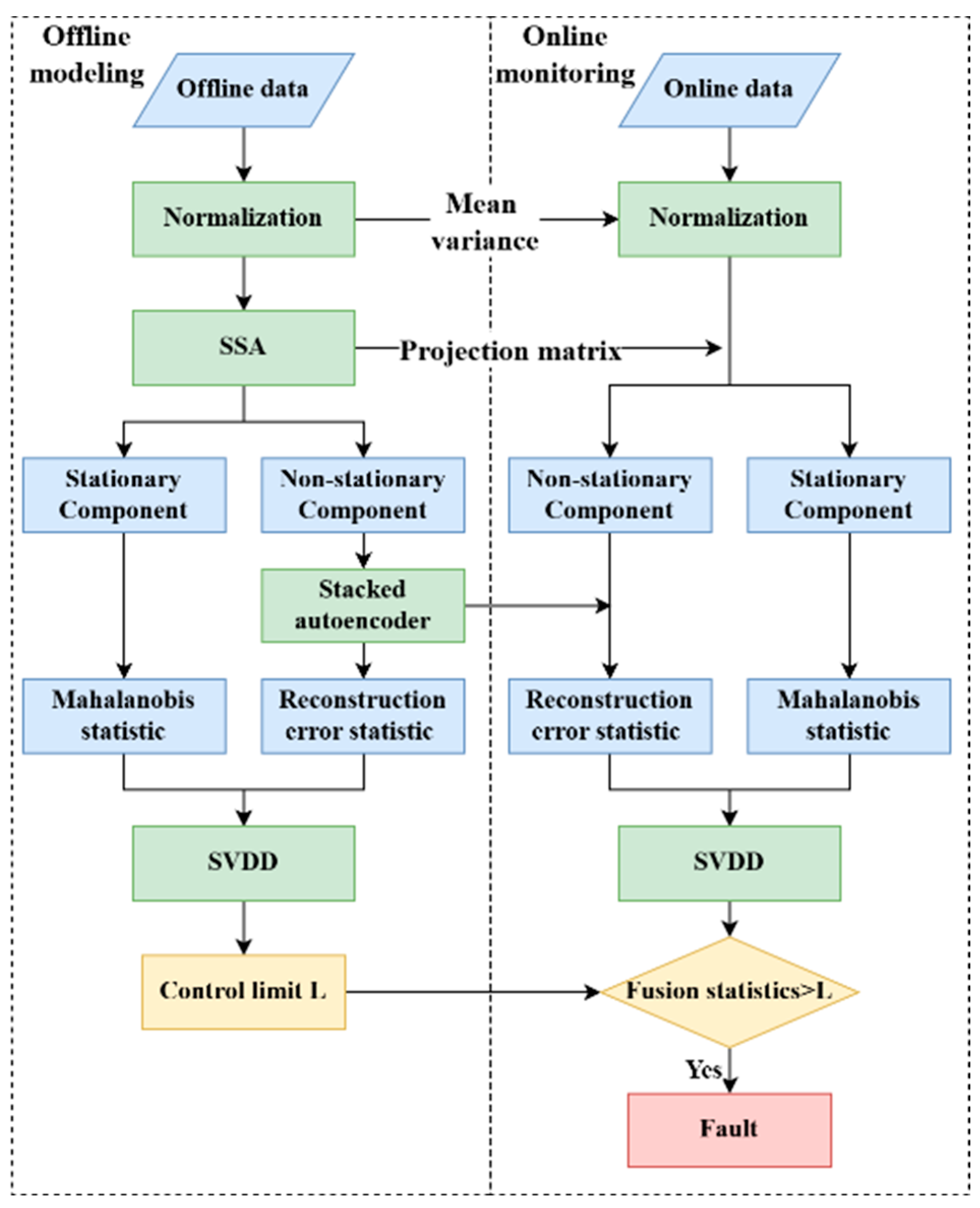

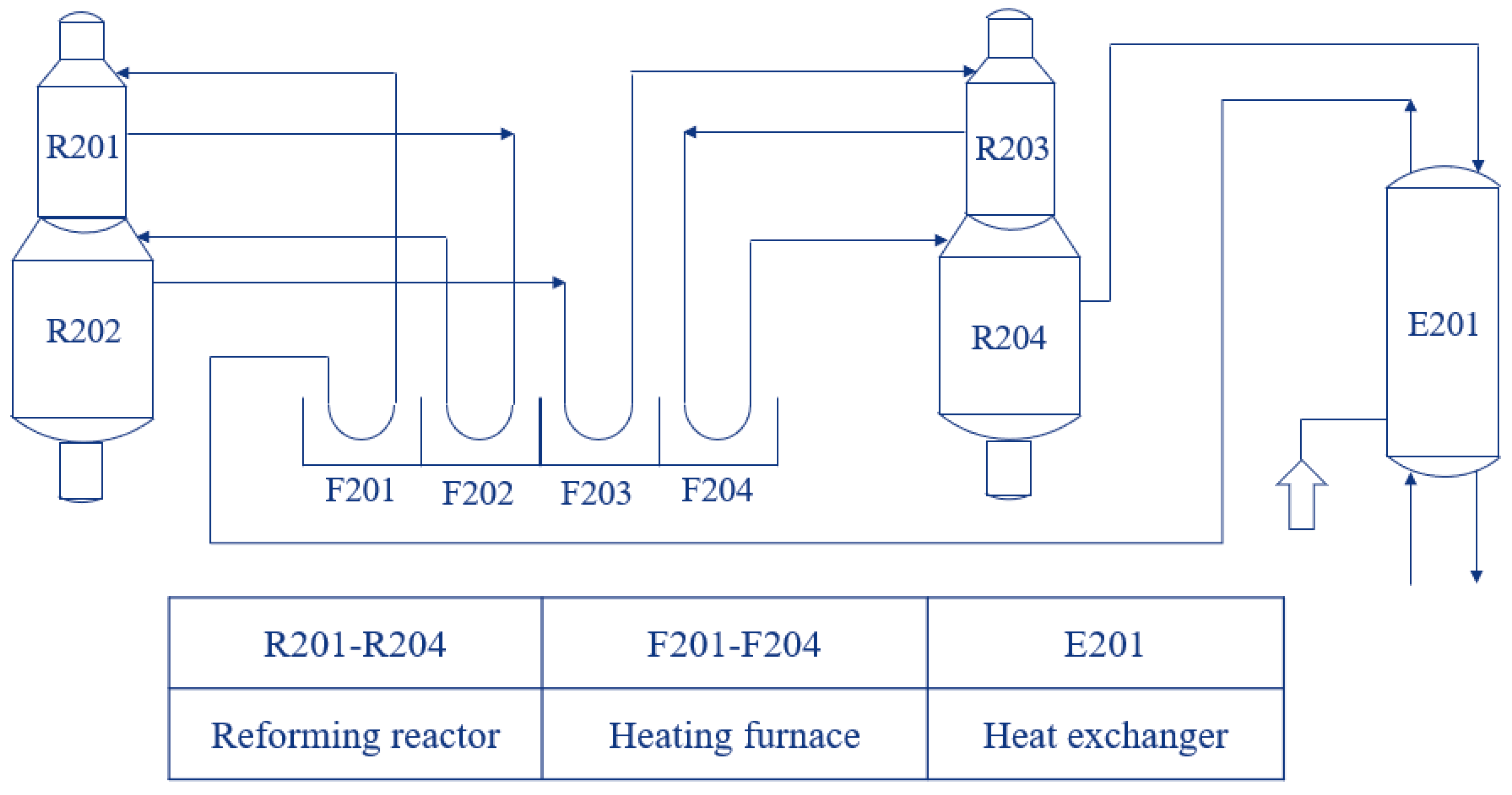

The modeling and implementation steps of the method are shown in

Figure 1, which is mainly divided into two parts: offline modeling and online monitoring.

Offline modeling

The offline modeling consists of the following steps:

Step 1: The training data were normalized with Equation (14):

where

and

denote the sample mean and the standard deviation of the training data, respectively.

Step 2: SSA was employed on the normalized data to extract the stationary and non-stationary components. A Mahalanobis distance statistic was established for the stationary components, while the non-stationary components were input into a stacked autoencoder.

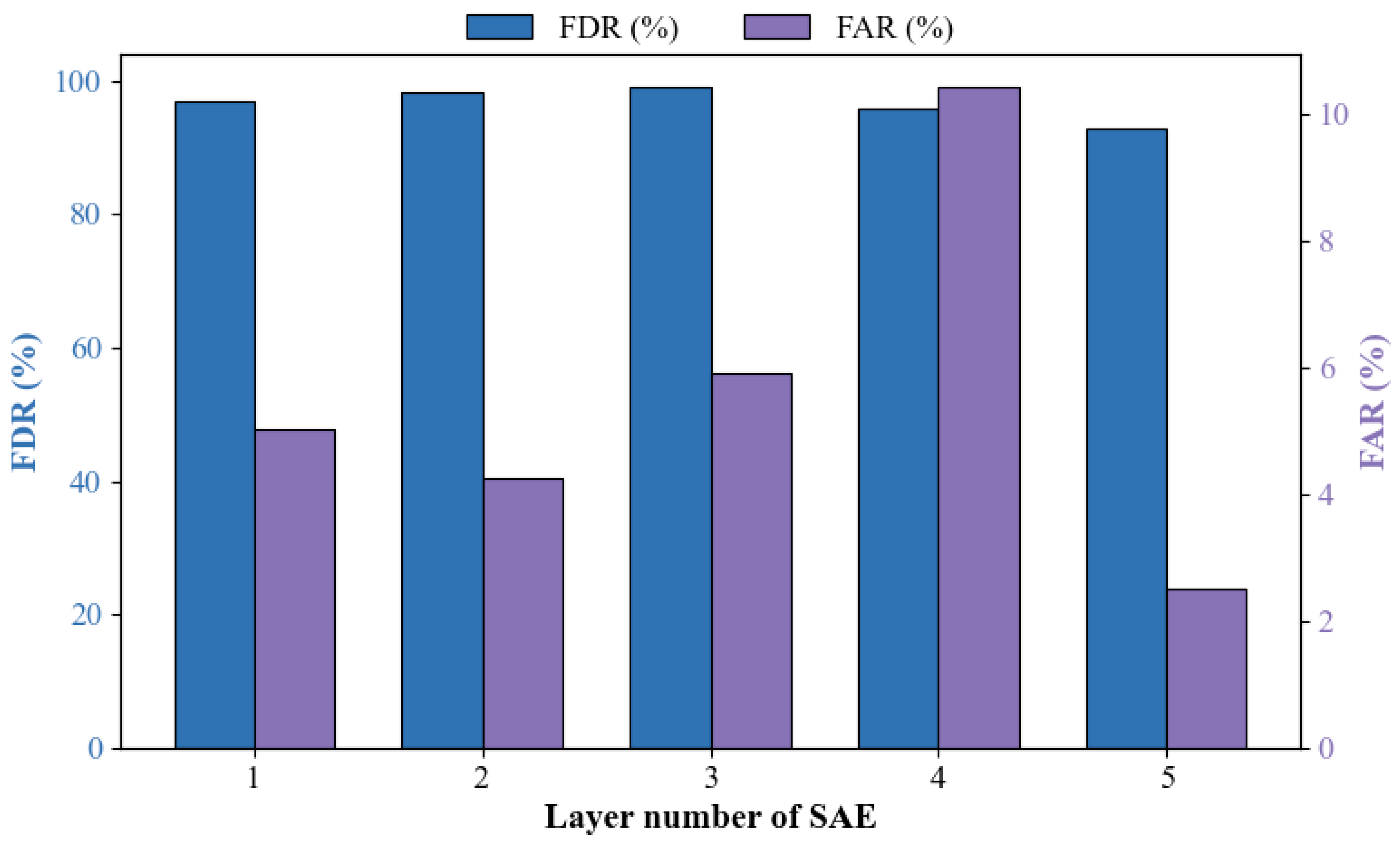

Step 3: The SAE model was established to reconstruct the non-stationary components, and a monitoring statistic based on reconstruction error is then established.

Step 4: The two statistics were concatenated together, and each statistic can be regarded as a spatial coordinate of a sampling point. Then, all sampling points were mapped to a high-dimensional space via SVDD to find a hypersphere region of minimum size. The radius of the hypersphere is the control limit.

Online monitoring

The online modeling consists of the following steps:

Step 1: The online data were normalized by the mean and variance of the offline data.

Step 2: The normalized data were projected into stationary and non-stationary subspace. A Mahalanobis distance statistic was established for the stationary subspace, while the non-stationary components were input into the trained stacked autoencoder.

Step 3: The non-stationary components were reconstructed by the trained SAE model to obtain the reconstruction error-based statistics.

Step 4: The two statistics were concatenated and mapped by SVDD to obtain the distance between a new sample and the hypersphere’s center, which is the fusion statistics. When the fusion statistics exceed the control limits, it is deemed that a fault has occurred.