Abstract

With the increasing access capacity of new energy, the impact of extreme weather on source–load is intensifying, threatening the balance of supply and demand in the power system. Aiming at the systemic risks caused by the uncertainty and volatility of the spatiotemporal distribution of source–load under extreme weather conditions, this paper proposes a new method for power system operation risk assessment considering the spatiotemporal distribution of source–load under extreme weather. Firstly, the influence of various meteorological factors on the output and load of new energy under extreme weather is studied, and the meteorological sensitivity model of source–load is established. Secondly, aiming at the problem of limited historical data of extreme weather scenarios, this paper proposes a method for generating annual operation scenarios of power systems considering extreme weather: using Gaussian process regression to reconstruct extreme weather scenarios, and fusing them into typical meteorological year series through quantile incremental mapping method, forming meteorological scenarios with both typical characteristics and extreme events, and combining the source-load model to obtain the system operation scenario. Thirdly, a new power system risk assessment model considering the impact of extreme weather is established, and the risk indicators such as load shedding, line overlimit, and wind and solar curtailment on a long-term scale are evaluated by using the daily operation simulation in the annual operation scenario of the system. Finally, the IEEE 24-node System is used to analyze the numerical examples, which show that the proposed method provides a quantitative risk assessment framework for the power system to cope with extreme weather, which is helpful to improve the resilience and reliability of the system.

1. Introduction

In the context of global climate change, extreme weather events are becoming more frequent and more destructive. Extreme meteorological conditions such as high temperatures, heat waves, cold waves, and typhoons have brought serious challenges to the stable operation of the power system [1,2,3]. With the rapid growth of new energy installed capacity, the randomness and volatility of new energy output further increase the operational risk of the power system [4]. Extreme weather conditions will bring significant fluctuations and uncertainties to new energy power generation, and put great pressure on the optimal scheduling, power supply reliability, and grid security of the power system [5]. At the same time, as the proportion of air conditioning load increases, the load characteristics will also change significantly with extreme weather conditions. In extreme high temperature weather, the air conditioning and cooling load have increased sharply; In low temperature weather, the heating load increases significantly [6]. These changes pose a severe risk of supply and demand imbalance, which can lead to problems such as load cutting, line exceeding limits, and abandoning wind and solar energy, which threatens the safe and stable operation of the power system [7,8,9]. The destructive impacts of extreme weather are not merely theoretical but have been starkly demonstrated in real-world power system disasters. For instance, Tropical Cyclone Gonu caused the collapse of multiple 132 kV transmission towers in Oman, leading to extensive and prolonged blackouts [10]. Similarly, the 2021 winter storm in Texas, USA, triggered a catastrophic power crisis due to the sequential failure of gas, wind, and nuclear power facilities, resulting in widespread load shedding and socio-economic chaos [11]. Furthermore, Super Typhoon Mangkhut inflicted severe damage to overhead lines and substations in Southern China, compelling a massive and complex grid restoration effort [12]. These events underscore the vulnerability of critical power infrastructure—including generation units, transmission lines, and substations—to diverse extreme weather phenomena and highlight the urgent need for robust risk assessment frameworks.

At present, scholars have carried out research on meteorological factors and power system source–load prediction. Refs. [13,14] proposed a method for predicting the output of new energy stations by combining meteorological factors such as wind speed, air pressure, temperature, humidity, and light intensity, which significantly improved the prediction accuracy of new energy output. Ref. [15] analyzed the impact mechanism of extreme weather on wind power, photovoltaics, and hydropower, and pointed out that the fluctuation of meteorological conditions caused by climate change significantly reduced the stability of new energy output. Ref. [16] discusses the prediction performance of physical models, time series analysis, and deep learning methods to solve the problem of wind power output fluctuations in extreme weather. Ref. [17] explores the indirect effects of extreme weather on solar power generation, such as a 30% reduction in irradiance caused by aerosol occlusion; Ref. [18] analyzed the spatiotemporal correlation between climate factors and power loads, and separated climate-sensitive loads from the overall load for special prediction, which significantly improved the accuracy of load prediction. Ref. [19] suggests that the global heatwave in 2024 led to an increase in electricity demand by 31%, 37%, and 19% in China, the United States, and India, respectively, with air conditioning loads dominating. The study found that the decline in photovoltaic output and the surge in load under extreme high temperatures form a “double pressure”, forcing the increase of coal power output. The above studies on meteorological factors can obtain a good prediction of new energy output and load. However, most of the existing studies focus on a single meteorological factor or local scenario, and lack a comprehensive analysis of the comprehensive impact of power system source–load under extreme weather, and its scalability and effectiveness in large-scale power grid systems still need to be verified.

Meteorological scenarios that conform to actual physical characteristics are the basis for assessing the operational risk of the power system in extreme weather. At present, scholars have studied the generation method of extreme weather scenarios and applied it to the risk assessment of power systems. Ref. [20] proposed a pattern-guided diffusion model (PGDM) for the generation of controlled renewable energy scenarios, which uses a perceptual variational autoencoder to map high-dimensional scenes into low-dimensional latent spaces, thereby reducing the computational burden. Combined with the conditional potential diffusion model, controllable scene generation is realized. Ref. [21] proposed a DRL framework based on the Conditional Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Model (CDDPM), which enhances the stability of scene generation by constructing a time series denoising network (TSDN). Ref. [22] based on the improved Iterative Ad Hoc Data Analysis Technology Algorithm (ISODATA) clustering algorithm and backward reduction method, a set of typical scenarios representing photovoltaic and load uncertainty was generated. The above studies can describe extreme weather scenarios, but they cannot accurately describe the spatio-temporal characteristics of meteorological factors, and fail to solve the uncertainty and fluctuation of the spatio-temporal distribution of source–load caused by extreme weather.

Regarding power system risk assessment, Reference [23] discusses the advantages and disadvantages of methods for predicting weather-related outages in power systems. It also elaborates on the risk assessment process for power systems under extreme weather conditions based on these methods. Reference [24] proposes a long-term risk assessment model for power systems considering multiple extreme weather events, developing power system failure scenarios based on electrical component vulnerability curves and random sampling methods. Reference [25] addresses the hazards of typhoon weather to power grids by proposing an exponential function-based line failure rate model based on typhoon wind speeds, using system load shedding volume as a risk assessment indicator for simulation calculations. Reference [26] introduces FMEA to analyze the risk of power outages caused by extreme weather events at different locations in major cities on New Zealand’s North Island through a location-based risk assessment method, aiming to evaluate and enhance power system resilience. Reference [27] proposes a framework for assessing the vulnerability of electricity provisioning grids (EPG) to extreme weather events, evaluating future EPG vulnerability under three distinct climate change scenarios. Reference [28] introduces a multi-scenario stochastic risk assessment method to quantitatively evaluate the operational risks of power systems during extreme rainfall events. Considering load curtailment levels and their significance to quantitatively evaluate power supply security risks under extreme rainfall scenarios. The aforementioned studies primarily focus on risk decision-making frameworks and probabilistic risk assessment models, investigating the impact of extreme weather on power system operational risks. However, they address only specific historical extreme weather events, overlooking the fact that actual power grids may face multiple types of extreme weather and multiple uncertainties. Consequently, they fail to effectively analyze the impact of extreme weather on the spatiotemporal distribution of large-scale renewable energy generation and air conditioning loads.

Given the above analysis, this paper investigates a novel power system operational risk assessment method that accounts for the spatiotemporal distribution of generation and load under extreme weather conditions. First, it examines the mechanisms of renewable energy output and load variation patterns influenced by multiple meteorological factors during extreme weather events, establishing a new meteorological sensitivity model for generation and load. Second, addressing the limited and incomplete observational data for extreme weather scenarios, this paper proposes an annual power system operation scenario generation method that incorporates extreme weather. This method first employs Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) to reconstruct extreme weather event scenarios, yielding a set of extreme weather scenarios. Subsequently, the Quantile Delta Mapping (QDM) technique was applied to fuse the reconstructed extreme weather scenario set with typical meteorological year (TMY) sequences, generating annual meteorological scenarios that retain the original statistical characteristics of TMY while incorporating key extreme weather features. These scenarios were then combined with the source-load meteorological sensitivity model to derive power system operation scenarios. Finally, a novel power system operational risk assessment model was established, accounting for the spatiotemporal distribution impacts of extreme weather on generation and load. This model evaluates the effects of extreme weather on the safe and stable operation of the power system from multiple dimensions, including load shedding, line power flow violations, and curtailed wind and solar power generation.

2. Meteorological Sensitivity Model of New Source-Load

Under extreme weather, meteorological factors such as temperature, wind speed, irradiance, precipitation, and humidity do not act independently; instead, they jointly affect new energy output and load characteristics through complex coupling relationships. The new energy output is directly related to the meteorological factors, and the coupling of multiple factors in extreme weather will break the normal characteristics, presenting strong nonlinearity, sudden change, and uncertainty. For loads, the coupled effect of multiple factors in extreme weather will amplify the peak-to-valley difference of loads, change the timing characteristics, and even trigger structural mutations. In the following, the meteorological sensitivity model of the new source-load is established by analyzing the mechanism of new energy output and the change rule of load.

2.1. Meteorological Sensitivity Model of Photovoltaic Power

Photovoltaic output and irradiance are approximately linearly correlated, and the conversion efficiency of photovoltaic panels decreases with increasing temperature. Although irradiance is high at extremely high temperatures, the efficiency loss due to high temperatures may be greater than the PV efficiency gain due to high irradiance. For example, when the operating temperature of PV panels reaches 40 °C (a condition that may occur in urban areas due to the heat island effect or in open fields with inadequate heat dissipation), the output power under the same solar intensity is 15% lower than that at 25 °C. At low temperatures, although low temperatures can improve the conversion efficiency of PV, if there is snow cover at this time, the output power will still plummet, forming a paradoxical coupling of “favorable temperature–irradiance blocked”. The meteorological sensitivity model of PV output is expressed as [29]:

where is rated PV output power (kW); is actual PV output power (kW); is the irradiance (W/m2); is the rated power of PV system (kW); is the surface temperature of PV (°C); and are the temperatures under the rated irradiance and rated power, respectively; (dimensionless) is the joint correction coefficient for multiple meteorological factors, such as 0.8–0.9 for extreme high temperature, 0.1–0.3 for typhoon, and 0.2–0.5 for cold snap.

2.2. Meteorological Sensitivity Model of Wind Power Output

Wind power output is mainly dependent on wind speed, and its output depends on the real-time wind speed and the wind turbine output characteristic curve. However, the combined effect of temperature, humidity, air pressure, and other factors in extreme weather also affects the efficiency of the wind turbine in capturing wind energy. In extreme weather, blade icing under blizzard conditions reduces the efficiency of mechanical transmission; to prevent rotor overheating and damage under extreme high temperatures, wind turbines usually operate with reduced power. The meteorological sensitivity model of wind power output is as follows [30]:

where is the wind speed, is the rated wind speed, is the cut-in wind speed, and is the cut-out wind speed; is the rated power of the wind turbine, is the icing coverage rate; is the icing impact factor, which is usually 0.3–0.6.

The parameter settings of meteorological sensitivity model for PV power plant and wind farm are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameters of wind power and photovoltaic output conversion model.

2.3. Meteorological Sensitivity Modeling of Air-Conditioning Loads

Under extreme weather conditions, the sensitivity of electricity load to meteorological factors increases significantly. In high-temperature weather, air conditioners and other refrigeration equipment are activated in large numbers, driving residential and commercial electricity loads to climb; in low-temperature weather, the use of heating equipment increases, also causing load growth. Changes in irradiance also affect lighting loads. High irradiance during the day reduces the demand for lighting in buildings and reduces the load; cloudy days or low irradiance at night increase the hours of use of lighting equipment and drive up the load. The direct effect of wind speed on negative loads is relatively small and usually negligible. The weather-sensitive load calculation formula that integrates the effects of temperature and irradiance is shown as follows [31]:

Equations (6)–(8), is the base load demand; and are the temperature and irradiance of t; and are the load temperature and irradiance sensitivity coefficients of n; and are the comfort temperature and irradiance; indicates that every 1 °C load increase in high temperature reflects the air conditioning and cooling demand; indicates the load increase for every 1 °C decrease in low temperature reflects the heating demand; indicates the irradiance correction coefficient; indicates that the change of irradiance on the lighting load impact rate, usually cloudy. represents the rate of impact of irradiance changes on lighting loads, which typically increase on cloudy days or at night.

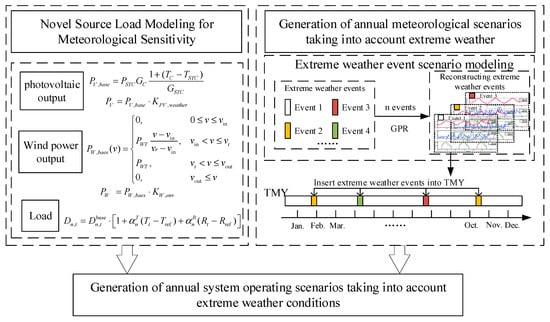

3. Generating Annual Operational Scenario Generation for Considering Extreme Weather Events

Extreme weather events significantly impact the spatiotemporal distribution of power generation and load in power systems. While traditional Typical Meteorological Year (TMY) sequences capture long-term climate characteristics, they struggle to reflect the suddenness and abnormality of extreme events. To more accurately assess operational risks in power systems under extreme weather conditions, it is necessary to construct annual operational scenarios that retain the typical statistical features of TMY while also reflecting the impact of extreme events. This chapter proposes a method for generating annual power system operation scenarios incorporating extreme weather events: First, based on historical extreme weather data, Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) is employed to model and reconstruct the occurrence time, frequency, duration, and intensity of extreme weather events, generating a set of extreme weather scenarios with spatiotemporal characteristics. Second, the reconstructed extreme weather scenarios are embedded into the TMY sequence using Quantile Delta Mapping (QDM), thereby rationally introducing the “anomaly signals” of extreme events while preserving the original meteorological statistical characteristics of the TMY. Finally, integrating the meteorological sensitivity models for PV, wind power, and load established in Section 2, the meteorological scenarios are converted into system operation scenarios. Scenario probabilities are estimated based on historical occurrence frequencies, and the annual system operation scenario generation framework for extreme weather is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Framework Diagram for Generating Annual System Operation Scenarios Considering Extreme Weather Events.

3.1. Modeling Extreme Weather Events Using Gaussian Process Regression

This study employs a Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) model [32] based on historical extreme weather event data to reconstruct scenarios of extreme weather events such as heatwaves, cold waves, and typhoons.

3.1.1. Gaussian Process Regression Model

Gaussian process regression is a regression method based on Gaussian processes (GP). A Gaussian process is a set of random variables defined on an input space, where the joint distribution of each variable follows a Gaussian distribution. In scene generation, the advantages of Gaussian processes primarily lie in their ability to capture complex functional relationships, quantify uncertainty, and adapt flexibly based on observational data.

The core of Gaussian process regression lies in the covariance function of the Gaussian process, which determines the degree of data smoothing. For Gaussian regression problems, the following form is typically considered:

Here, x denotes the input vector, f represents the function value, and y signifies the observed value after noise addition. If the noise is assumed, the joint prior distribution of the observed value and the predicted value can be obtained as shown in Equation (10):

Among these, denotes the covariance matrix of a symmetric positive definite matrix, where matrix elements describe the correlation between xi and xj; represents the nth-order covariance matrix between the training set input X and test points ; signifies the covariance between test points and themselves, is the n × n identity matrix. The posterior distribution of the predicted value calculated based on its joint prior distribution is given by Equation (11):

Their means and covariances satisfy the equation (12):

The covariance function in the above equation is selected as a combination of the ScaleKernel and RBFKernel covariance functions from GPyTorch (v1.10.0 and v2.1.0).

In Equation (13), and represent the hyperparameters of the ScaleKernel and the base covariance function, respectively. x1 and x2 denote the input variables, while is the hyperparameter of the RBFKernel, also known as the long-range parameter. Combining these two covariance functions yields the overall covariance function for the Gaussian process regression model.

3.1.2. Generation of Extreme Weather Scenarios

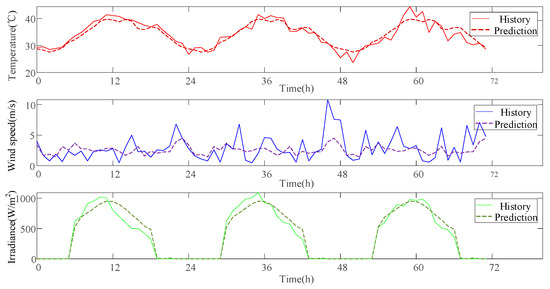

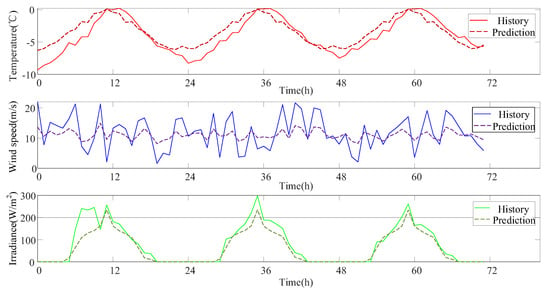

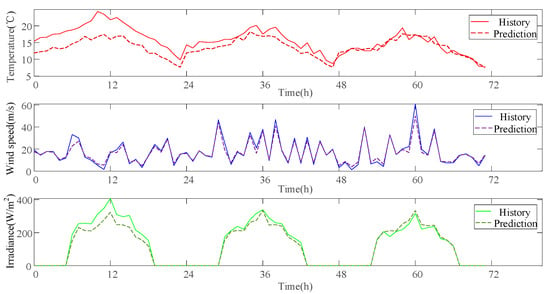

The formation and development of extreme weather events are influenced by a complex interplay of multiple factors, whose relationships are often nonlinear and intricate. Gaussian process regression (GPR) offers a flexible approach to capturing these complex nonlinear relationships, enabling more accurate characterization of patterns within historical extreme weather data. After reconstructing historical extreme weather events using the GPR model, three types of extreme weather scenarios—extreme heat, cold waves, and typhoons—were generated, as illustrated in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4.

Figure 2.

Extreme Heat Scenario.

Figure 3.

Cold Wave Scenario.

Figure 4.

Typhoon Scenario.

3.2. Annual Operation Scenario Generation Method Based on TMY

To significantly reduce computational effort and effectively capture long-term variation patterns of meteorological elements, typical meteorological year (TMY) operational scenarios are generated based on meteorological scenarios that account for spatiotemporal characteristics.

3.2.1. Method for Generating a Typical Meteorological Year

TMY refers to a “hypothetical year” constructed by selecting 12 typical months with meteorological elements closest to historical averages and statistically significant, based on historical meteorological data spanning at least the past decade. Twelve representative meteorological months most consistent with long-term climatic patterns are individually selected, and these 12 months are ultimately linked to form a “hypothetical year” as the TMY. TMY is a classic method in meteorology and renewable energy assessment studies, capable of representing long-term climate patterns. The generation process is as follows [33]:

- (1)

- Calculate the long-term cumulative distribution function and the annual cumulative distribution function values for each meteorological parameter:

In the formula, represents the long-term cumulative distribution value at position x; k denotes the rank of factor x in the ascending time series; N is the total sample size.

- (2)

- Calculate the Finkelstein-Schafer statistics for each meteorological variable, abbreviated as

In the formula, represents the absolute difference between the long-term cumulative distribution value of each meteorological element and its monthly cumulative distribution value; denotes the number of days within each analysis month.

- (3)

- Based on the values calculated for each meteorological element monthly as described above, is computed using a specific weighting coefficient

In the formula, KK denotes the number of meteorological elements. The minimum value corresponding to the solar energy resource element is selected as the representative value for that time point (month), thereby forming a complete annual time series dataset.

3.2.2. Extreme Weather Scenario Insertion into TMY

Integrating extreme weather scenarios generated by Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) into TMY data involves embedding the “anomaly signals” of extreme events while preserving the original typical meteorological characteristics of TMY, ensuring both spatio-temporal continuity and physical consistency of the data. Quantile Delta Mapping (QDM) is an efficient method that incorporates extreme weather features by adjusting the quantile distribution of TMY data. The specific steps are as follows:

- (1)

- Select appropriate time periods for extreme events based on climatic patterns: extreme heat is inserted into TMY’s summer months (July–August), while cold waves are inserted into winter months (December–February).

- (2)

- Calculate the quantiles of TMY data. Choose appropriate quantile calculation scales for different meteorological factors: hourly quantiles are calculated daily for temperature and irradiance; hourly quantiles are calculated monthly for wind speed.

- (3)

- Extract the increment for extreme weather events. Compare the extreme event parameter value with the corresponding TMY quantile for that time window, calculating the absolute increment as: Δ = Extreme Value–TMY Quantile. For example, if an extreme high temperature event reaches 40 °C while the TMY 95th percentile for the same period is 35 °C, then Δ = 5 °C.

- (4)

- Hourly adjustment of TMY. Within the insertion window, add the calculated Δ to the corresponding TMY parameter: Adjusted parameter = Original TMY value + Δ.

After inserting TMY into the extreme weather scenario, calculate the annual occurrence probability of each meteorological day in the system operation scenario based on the frequency of historical meteorological data. The calculation formula is shown in Equation (17):

Among these, represents the probability of occurrence for scenario d in the TMY; denotes the number of occurrences for this scenario type within the meteorological month; M indicates the number of days in that month.

3.2.3. Annual Operation Scenario Generation Process for Power Systems

The annual operation scenario generation process based on TMY is as follows:

Step 1: Reconstruction of Extreme Weather Scenarios. Based on historical extreme weather event data, the GPR model is utilized to statistically reconstruct their occurrence times, frequencies, durations, and meteorological parameter intensities. Multiple sequences of extreme weather scenarios are generated to form a set of extreme weather scenarios.

Step 2: Insertion of Extreme Scenarios into TMY. Employing quantile increment mapping, the reconstructed extreme weather scenarios are embedded into corresponding periods within the TMY. This introduces extreme meteorological deviations while preserving the overall statistical characteristics of the TMY, resulting in an annual meteorological scenario sequence that balances typicality and extremity.

Step 3: Meteorological-Source-Load Conversion and Scenario Probability Calculation. The integrated annual meteorological scenarios are input into meteorological sensitivity models for PV, wind power, and load (Section 1). Daily and hourly renewable energy output and load data are generated to form system operation scenarios. Simultaneously, based on the historical frequency of extreme weather events in the region, the occurrence probability of each meteorological day is calculated using Equation (17), providing a basis for subsequent risk probability assessment.

Step 4: Output Annual Scenario Set. Integrate all date-specific scenarios and their occurrence probabilities to generate an annual power system scenario set with probability distributions. This serves as the foundational input for operational simulations and risk assessments.

4. Operational Risk Assessment Framework for Power Systems Under Extreme Weather

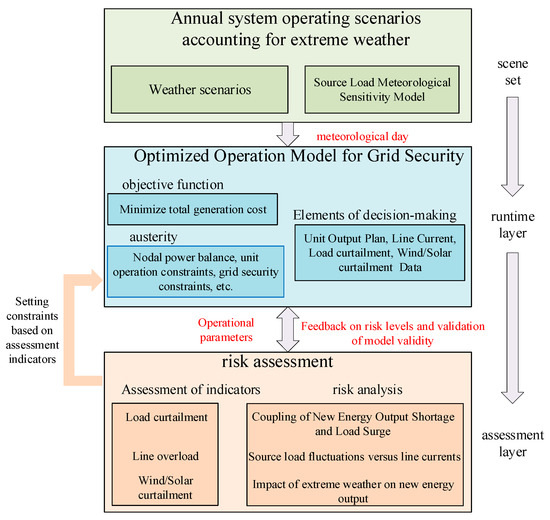

To address the impact of extreme weather on the operation of new power systems, this paper constructs a risk assessment framework for new power system operation that accounts for the spatiotemporal distribution of sources and loads under extreme weather conditions, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Operational Risk Assessment Framework.

By iteratively processing annual operational scenarios incorporating extreme weather events, each meteorological day serves as an operational scenario for the power system optimization model that evaluates grid security. The risk assessment indicators are calculated for each day, then aggregated to derive monthly and annual risk assessment metrics. These metrics are subsequently utilized to analyze the impact of extreme weather on power system operational risks.

4.1. Optimal Operation Model for Power Systems Considering Grid Security

To establish a daily operational model for the power system under annual operational scenarios, this paper develops an optimized operational model for the power system at the meteorological day level, incorporating grid security considerations. This model provides a foundation for subsequent risk assessments of power system operations under extreme weather conditions. The optimization objective is to minimize the operational cost per meteorological day, encompassing unit start-up/shutdown costs, generation costs, load shedding costs, and wind and solar curtailment costs.

4.1.1. Objective Function

The objective function is formulated as:

In the equation, denotes the generation cost of unit g at time t, including fuel costs and start-stop costs ; is the actual active power output of the g-th conventional generation unit at time t; , , represent the fuel cost coefficients of the g-th conventional generation unit; , represent the single start-up cost and shut-down cost of the g-th conventional generation unit, respectively; , represent the start-up status variable and shut-down status variable, respectively; and represent the penalty costs for curtailed wind and solar power generation and load shedding, respectively; is the load shedding amount of load l at time t; denotes the solar curtailment of photovoltaic station PV at time t; denotes the wind curtailment of wind farm W at time t; , , and denote the generator set, load set, solar power set, and wind power set within the system, respectively.

4.1.2. Constraints

- (1)

- Node active power balance constraints are given by Equation (19):

- (2)

- Unit Operation Constraints

Unit operation constraints include: upper and lower output limits as in Equation (20), generator ramping constraints as in Equation (21), and unit start-up/shutdown constraints as in Equation (22) [34]:

where and represent the minimum and maximum active power technical outputs of units g, respectively; and denote the maximum ramp-up rate and maximum ramp-down rate of units g, respectively; , , and represent the operational state, start state, and stop state of unit g during time period t, respectively; and denote the minimum continuous operational and non-operational durations of unit g during time period t.

- (3)

- Load shedding constraints are shown in Equation (23):

- (4)

- Renewable Energy Output Constraint as shown in Equation (24) [35]:

- (5)

- Line Transmission Power Flow Constraint as shown in Equation (25) [36]:

4.2. Calculation of Risk Assessment Indicators

This paper primarily focuses on four types of risks: load shedding risk, line overlimit risk, wind curtailment risk, and solar curtailment risk. Load shedding risk quantifies the probability and impact of load shedding by evaluating load gaps and discrepancies between generation capacity and load demand. Line overlimit risk is assessed based on power flow probability distributions and concerns grid security and stability. Wind and solar curtailment risks are assessed based on the relationship between wind and solar power generation output and grid capacity. The calculation formulas for load shedding, line overlimit, wind curtailment, and solar curtailment risk indicators are shown in (26)–(29) [37,38,39]:

where , , , and denote the load shedding risk, line overlimit risk, wind curtailment risk, and solar curtailment risk, respectively; and represent the load shedding amount and original load of load l at time t on day d; is the occurrence probability of scenario d in the annual operation scenario accounting for extreme weather, obtainable via Section 3.2.2; is the power flow on line br at time t on day d; is the maximum transmission capacity of line br, where BR is the total number of lines in the system; and are the curtailed wind power and original available power output of wind farm w at time t on day d; and are the curtailed power and original available power output of photovoltaic power station pv at time t on day d.

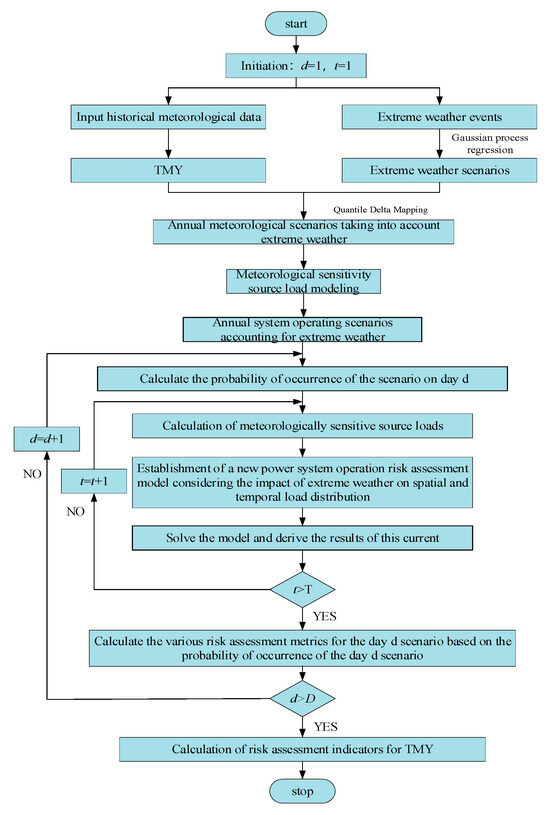

4.3. Risk Assessment Process of New Power System Operation Under Extreme Weather

The overall assessment process is illustrated in Figure 6, comprising three components: generating TMY data incorporating spatiotemporal characteristics and extreme weather scenarios while calculating scenario probabilities; establishing an optimized grid security operation model; and computing various system risk indicators. Specific steps are as follows:

Figure 6.

Flowchart for Assessing Operational Risks of New Power Systems Under Extreme Weather Conditions.

- (1)

- Initialize the number of scenarios D and the assessment time t.

- (2)

- Generate annual system operation scenarios incorporating extreme weather. Reconstruct extreme weather event scenarios using the GPR model to obtain a set of extreme weather scenarios. Subsequently, fuse the reconstructed extreme weather scenario set with typical meteorological year sequences using the quantile increment mapping method.

- (3)

- Calculate scenario probabilities. Combine historical data to compute the occurrence probability of scenario d on day d according to Equation (17).

- (4)

- Calculate renewable energy output and load. Substitute the TMY data, incorporating extreme weather into the meteorological sensitivity models for PV (Equation (1)), wind power (Equation (2)), and air conditioning load (Equations (6)–(8)) to obtain output and load data at time t on day d.

- (5)

- Establish an optimized operation model considering grid security. Solve the model to obtain power flow results for the power system at time t on day d. If t > T, terminate the day d power flow calculation; otherwise, set t = t + 1, return to step 4, and calculate the power flow at time t + 1 until a full day’s power flow results are obtained.

- (6)

- Calculate various risk indicators for the system. Substitute the day d power flow results into Formulas (26)–(29) to compute risk assessment metrics. If d > D, terminate the current risk assessment cycle; otherwise, set d = d + 1, return to step 3 to calculate the occurrence probability for day d + 1; proceed to steps 4 and 5 to compute the day d + 1 power flow results; then calculate the day d + 1 risk assessment metrics. Repeat until the risk assessment metrics for the entire scenario are obtained.

5. Case Studies and Analysis

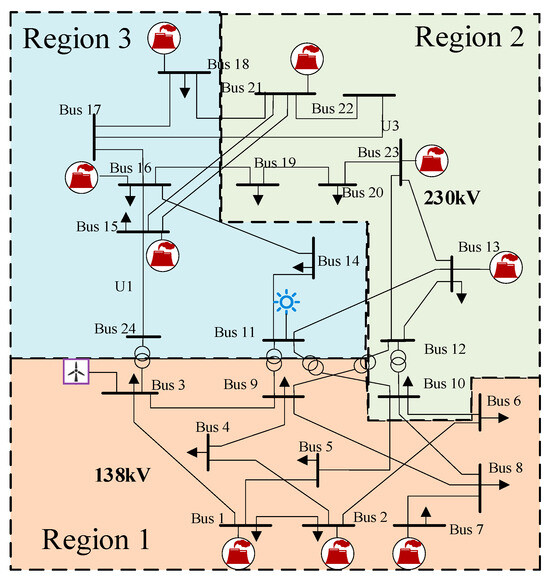

5.1. Scene Setting

This case study employs the modified IEEE 24-node System as the test system, utilizing the Python 3.12 platform to build and run the evaluation model. The modified system network diagram is shown in Figure 7, with the test system’s fundamental data referenced from Ref. [40]. A 200 MW wind farm is connected at node 3, and a 150 MW photovoltaic power station is connected at node 11. The IEEE 24-node System is divided into three zones. The extreme heat scenario is categorized into urban centers and suburban areas, designated as Zones 1, 2, and 3. It should be noted that the temperature thresholds are based on general extreme weather data and are not exclusive to urban environments. The regional classification is adopted to reflect spatial differences in temperature profiles, such as those amplified by urban heat islands. The typhoon and cold wave scenarios are divided into central, peripheral, and distant zones, labeled as Zones 1–3. TMY historical weather data is sourced from a decade of meteorological observations in a southern region of China [41], including temperature, wind speed, and irradiance. Based on statistical analysis of historical data, extreme weather events—cold waves in January, extreme heat in July, and typhoons in August—were inserted into the TMY data for these respective months.

Figure 7.

IEEE 24-node System Topology Diagram.

5.2. Generation of Annual System Operation Scenarios Considering Extreme Weather

Based on the set of extreme weather event scenarios, the typical meteorological characteristics of three categories of extreme weather scenarios are summarized in Table 2. For extreme weather scenarios inserted into the TMY, the most severe scenarios are considered, namely extreme high temperatures in urban central areas, cold waves, and typhoon centers.

Table 2.

Regional Scenario Characteristics of Extreme Weather.

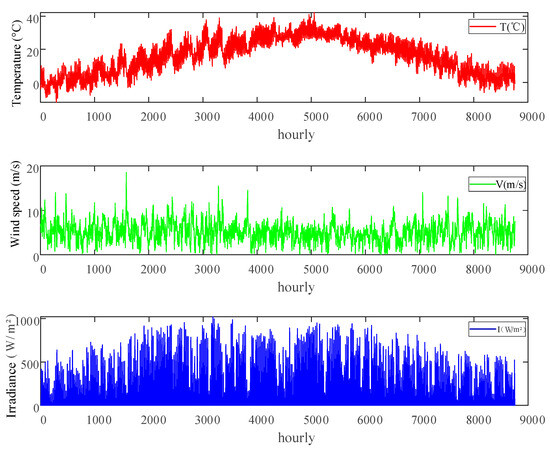

Based on the framework for generating annual system operation scenarios accounting for extreme weather outlined in Section 2, the extreme weather scenario set is integrated into the TMY using QDM to derive annual meteorological scenarios that incorporate extreme weather. These are then combined with the meteorologically sensitive source-load model to produce the system’s annual operation scenarios. The annual meteorological scenarios accounting for extreme weather are shown in Figure 8:

Figure 8.

Annual Meteorological Scenarios Accounting for Extreme Weather Events.

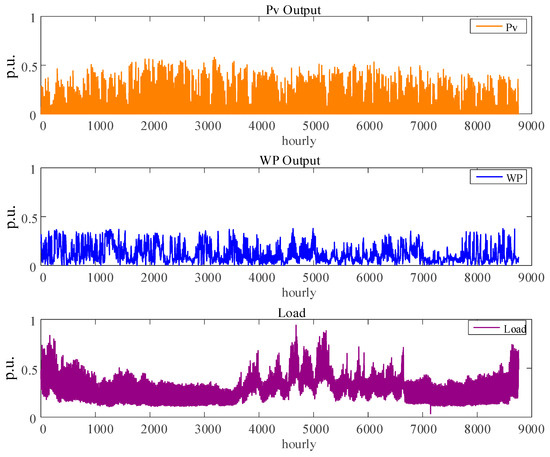

Annual meteorological scenarios incorporating extreme weather events are combined with a meteorologically sensitive source-load model to derive system-level annual operational scenarios accounting for extreme weather. As shown in Figure 9:

Figure 9.

Annual System Operation Scenario Considering Extreme Weather Events.

5.3. Calculation Results of System Risk Assessment Indicators

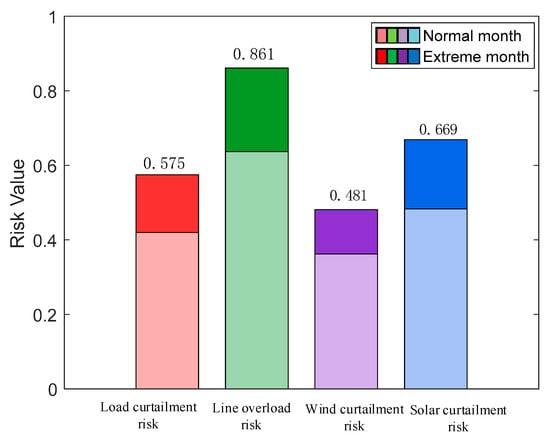

This section calculates the daily risk for each day of the system’s annual operating scenario and accumulates these values to derive risk assessment indicators for 12 meteorological months and the entire year. The results of the risk indicator calculations are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Risk Indicator Calculation Results.

As indicated in Table 3, among the four types of annual risk indicators, the total value of line overlimit risk is the highest (0.861), which constitutes the core risk in power system operation. It is followed by solar curtailment risk (0.669) and load shedding risk (0.575), while wind curtailment risk has the lowest total value (0.481).

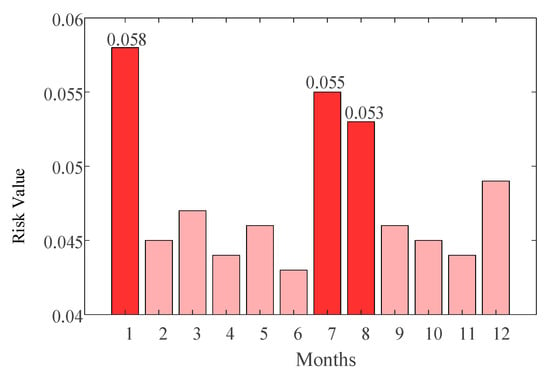

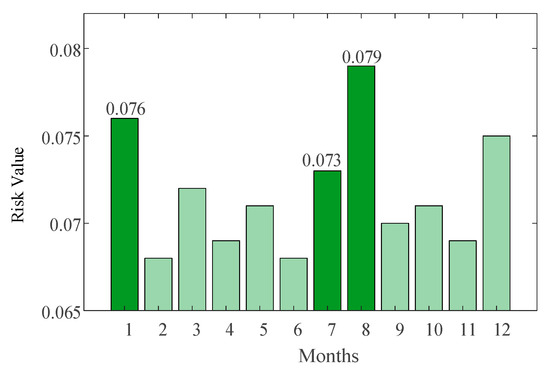

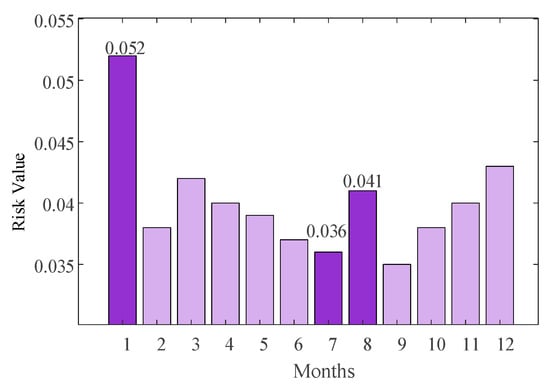

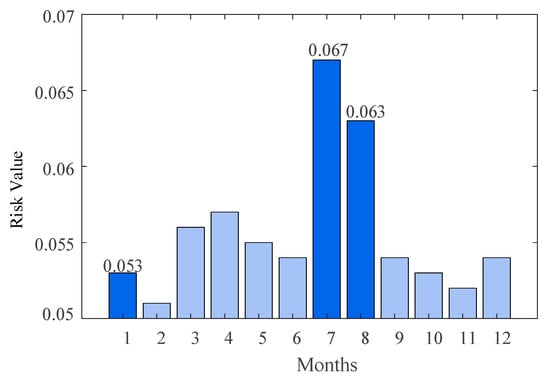

From a monthly perspective, the risks exhibit distinct characteristics associated with extreme weather. Affected by cold waves in January, both the load shedding risk (0.058) and wind curtailment risk (0.052) reach their annual peaks. Under extreme high temperatures in July, the solar curtailment risk (0.067) hits the highest level of the year, and the load shedding risk (0.055) also remains at a high level. In August, the typhoon scenario leads to the line overlimit risk (0.079) becoming the highest throughout the year. These phenomena reflect that different types of extreme weather exert differentiated impacts on various risk dimensions of the power system, whereas the various risk indicators in months without extreme weather remain relatively stable.

The risk levels of various indicators over the year are respectively shown in Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13, and the annual risk levels are presented in Figure 14.

Figure 10.

Risk level of load-cutting over the year.

Figure 11.

Over-limit risk level for lines over the year.

Figure 12.

Risk level of wind power curtailment over the year.

Figure 13.

Risk level of solar power curtailment over the year.

Figure 14.

Annual risk level across different categories over the year.

5.4. Analysis of System Risk Level Results

By conducting a full-time risk quantification assessment of annual system operation scenarios incorporating extreme weather, and integrating the spatiotemporal distribution characteristics of four risk indicators—load shedding, line over-limit, wind curtailment, and solar curtailment—this analysis reveals the impact mechanism of extreme weather on the operational risks of new power systems. Specific findings are as follows:

5.4.1. Risk Analysis of Extreme Weather Scenarios

Extreme weather alters the spatiotemporal distribution characteristics of generation and load, leading to differentiated high-incidence patterns across different risk types. Specifically:

- (1)

- Load Shedding Risk Analysis:

The spatiotemporal distribution of load shedding risk is closely linked to the type and intensity of extreme weather events. The risk level of load-cutting over the year is depicted in Figure 10. It is observed that, during the January cold wave scenario, the load shedding risk reached 0.058, marking the highest monthly value throughout the year. The primary cause is the average temperature in the cold wave’s core region dropping below −2 °C, leading to a sharp increase in heating demand. Concurrently, icing on wind turbine blades and snow accumulation on photovoltaic panels cause a sudden drop in renewable energy output. This creates a sharp contradiction between rapidly rising demand and sharply declining supply, where the widening supply-demand gap directly drives the increase in load shedding risk. During the extreme heat scenario in July, the load shedding risk remained at a relatively high level of 0.055. This was primarily due to temperatures exceeding 35°C in urban centers, triggering a sharp increase in air conditioning load. Concurrently, photovoltaic panel conversion efficiency dropped by over 15% due to high temperatures. This dual pressure of “load surge and PV output decline” exacerbated the supply-demand imbalance, thereby elevating the load shedding risk.

- (2)

- Line Overlimit Risk Analysis:

Over-limit risk level for lines over the year is depicted in Figure 11; the peak risk of line over-limit occurs during periods of extreme weather that trigger severe fluctuations in source-load conditions. Under the August typhoon scenario, the line over-limit risk reached 0.079, significantly higher than in other months. This phenomenon is closely related to the strong wind speeds of 13.9–20.7 m/s observed in the typhoon’s central region. High wind speeds cause wind power output to fluctuate significantly at high frequencies, with fluctuation magnitudes reaching 2 to 3 times those under normal operating conditions. The rigid constraints on grid transmission power cannot accommodate such rapid fluctuations, leading to frequent line power flow limit violation events. Additionally, the sharp increase in load during extreme heat waves triggers the redistribution of grid power flows. Consequently, the risk of line over-limit events in July (0.073) rises compared to non-extreme months, reflecting the indirect impact of load-side fluctuations on grid power flow stability.

- (3)

- Analysis of Wind and Solar Curtailment Risks:

The drivers of wind curtailment and solar curtailment risks vary depending on the type of extreme weather event. The risk level of wind and solar power curtailment over the year is depicted in Figure 12 and Figure 13, respectively. Wind curtailment risk peaked at 0.052 during the January cold wave scenario. This was primarily due to ice accumulation on turbine blades in the core cold wave region, causing a 30% to 60% reduction in mechanical transmission efficiency [42]. As a result, actual turbine output fell significantly below potential generation capacity, necessitating forced curtailment to ensure equipment safety. Conversely, solar curtailment risk is most pronounced during July’s extreme heat scenario (0.067). This occurs because photovoltaic panels in urban centers experience operating temperatures exceeding 40 °C, reducing conversion efficiency by 15% compared to the rated 25 °C operating condition. The widening gap between actual output and theoretical generation capacity, coupled with surging air conditioning loads, ultimately elevates solar curtailment risk. During the August typhoon scenario, wind turbines adopted power-reduction strategies to prevent rotor overheating, causing the wind curtailment risk to rise slightly to 0.041.

5.4.2. Annual System Risk Analysis

This section analyzes the annual risk levels across different categories over the year, as shown in Figure 14. It is observed that line overloading poses the highest risk at 0.861, representing the primary risk source. Concentrated power flows during extreme weather conditions can easily lead to line overloads. Solar and wind curtailment risks are moderate, with solar curtailment slightly higher due to photovoltaic output being more significantly affected by daily variations and extreme weather. Load shedding risk is relatively low, as the system supply-demand balance is generally maintainable. However, widespread line or power source failures during extremes could still necessitate load shedding. The figure also illustrates the proportion of risks attributable to extreme weather: line overlimit risks account for the highest share among all risk types, followed by solar curtailment risks (higher than wind curtailment), while load shedding risks show the lowest proportion. Overall, the mismatch in the spatiotemporal distribution of generation and load during extreme weather amplifies the pressure on renewable energy integration and transmission capacity, making system operation risks more constrained by network limitations and renewable energy absorption capabilities. This case study demonstrates that in the improved IEEE 24-node test system under extreme weather conditions, risks primarily concentrate on line overloading and renewable energy integration, with significant supply-demand imbalance risks as well. This provides a reference for grid operation planning and dispatch strategy formulation.

6. Discussion

This study proposes a novel operational risk assessment framework for power systems that incorporates the spatio-temporal distribution of source-load under extreme weather conditions. By developing extreme weather scenario models, this approach captures the spatio-temporal characteristics of source and load in large-scale renewable energy integrated power systems. The research outcomes enable effective assessment of operational risks in power systems with substantial renewable energy penetration, facilitating analysis of extreme weather-induced instability in renewable power generation and supporting strategic generation planning.

The present study, however, has certain limitations:

- (a)

- While extreme weather events such as hurricanes and floods significantly affect transmission infrastructure, the current framework does not incorporate transmission system impacts or physical damage models;

- (b)

- The potential contributions of energy storage systems, microgrids, and other technologies to enhancing system operational risk resilience remain unaddressed.

Future research should focus on developing damage models for transmission system components under extreme weather conditions and investigating how emerging technologies, including energy storage and microgrids, influence power system operational risk assessment.

7. Conclusions

This study addresses operational risk assessment for new power systems under extreme weather conditions by establishing a framework that accounts for the spatiotemporal distribution characteristics of generation and load during such events. Through theoretical modeling, scenario generation, and case validation, the following conclusions are drawn:

- (1)

- Extreme weather significantly amplifies system operational risks by altering the spatiotemporal distribution of generation and load. Case studies based on the IEEE 24-node system reveal that months with extreme weather contribute disproportionately to annual high-risk events: The January cold wave concurrently elevates load shedding risk (0.058, the annual peak), wind curtailment risk (0.052, the annual peak), and solar curtailment risk (0.053). During July’s extreme heat, the ‘dual pressures’ of surging air-conditioning load and reduced PV efficiency push load shedding risk (0.055) and solar curtailment risk (0.067, the annual peak) to high levels. The August typhoon, characterized by fluctuating wind power and transmission constraints, markedly accentuates line overlimit risk (0.079, the annual peak) and wind curtailment risk (0.041). Different extreme weather events exhibit distinct risk profiles, validating the necessity of integrating weather type and spatiotemporal characteristics into risk assessment.

- (2)

- The constructed risk assessment framework provides quantitative decision support for power systems responding to extreme weather. By generating annual operational scenarios that incorporate extreme weather and integrating source-load meteorological sensitivity models with a grid security optimization model, it enables a dynamic assessment of multi-dimensional risk indicators, including load shedding, line overlimit, and wind/solar curtailment. This framework identifies dominant risk factors under different extreme weather conditions; for instance, the annual cumulative risk analysis highlights line overlimit risk (0.861) as the most prominent, followed by solar curtailment risk (0.669). This provides a scientific basis for formulating differentiated response strategies and contributes to enhancing the risk resilience and overall reliability of new power systems during extreme weather events.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Y.S., G.J., J.X. and Y.M.; software, J.X. and M.W.; validation, M.W. and Y.M.; data curation, Y.S. and G.J.; writing—original draft preparation, M.W. and Y.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Project of State Grid Anhui Electric Power Co., Ltd. (No. B31209240009).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Jiayin Xu, Yuming Shen and Guifen Jiang was employed by the company Economic and Technology Research Institute of State Grid Anhui Electric Power Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Liu, S.; Shu, J.; Qiao, M. Assessment of the Impact of Extreme Weather on Power System Reliability. In Proceedings of the 2024 9th Asia Conference on Power and Electrical Engineering (ACPEE), Shanghai, China, 11–13 April 2024; pp. 2475–2480. [Google Scholar]

- Pizzimbone, L. AI-Based Assessment of Power System Resilience under Climate Change-Induced Extreme Weather Events. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Europe (ISGT EUROPE), Dubrovnik, Croatia, 14–17 October 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Dessens, O.; Anandarajah, G.; Cronin, J. Climate change impacts on hydro-generation and land suitability for agriculture in Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference and Utility Exhibition on Energy, Environment and Climate Change (ICUE), Pattaya, Thailand, 26–28 October 2022; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.; Mastoi, M.S.; Wang, D. Operation Risk Assessment of Power System with High Proportion of New Energy Integration. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 10th International Power Electronics and Motion Control Conference (IPEMC2024-ECCE Asia), Chengdu, China, 17–20 May 2024; pp. 3980–3985. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y. Simulation Evaluation Method of Power Grid Operation Considering High Proportion New Energy Grid Connection. In Proceedings of the 2021 6th Asia Conference on Power and Electrical Engineering (ACPEE), Chongqing, China, 8–11 April 2021; pp. 1666–1671. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, L.; Wei, M.; Zhang, P.; Wen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Mao, W. Load Adjustable Potential Assessment Considering Load Flexible Control and Air Conditioner Load Response in Extremely Hot Weather. In Proceedings of the 2023 8th International Conference on Power and Renewable Energy (ICPRE), Shanghai, China, 22–25 September 2023; pp. 1505–1510. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, M.A.; Sunny, M.R.; Zhang, C. An Approach to Imbalance Power Management Using Demand Response in Electricity Balancing Market. In Proceedings of the 2019 5th International Conference on Advances in Electrical Engineering (ICAEE), Dhaka, Bangladesh, 26–28 September 2019; pp. 490–495. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Yu, Z.; Ye, R.; Lin, Z.; Tang, Y. An Ordered Curtailment Strategy for Offshore Wind Power Under Extreme Weather Conditions Considering the Resilience of the Grid. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 54824–54833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Weng, J.; Lou, B.; Huang, X.; Huang, H.; Wu, J.; Zhou, D. Vulnerability Assessment of Distributed Load Shedding Algorithm for Active Distribution Power System Under Denial of Service Attack. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 9, 2066–2075. [Google Scholar]

- Abdalla, O.H.; Alkhusaibi, T.M.; Awlad-Thani, M.; Al-Mazrouey, M.N. Restoration of a 132 kV overhead transmission line affected by tropical cyclone Gonu in Oman. In Proceedings of the IEEE PES Transmission and Distribution Conference and Exposition, Chicago, IL, USA, 21–24 April 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Busby, J.W.; Baker, K.; Bazilian, M.D.; Gilbert, A.Q.; Grubert, E.; Rai, V.; Rhodes, J.D.; Shidore, S.; Smith, C.A.; Webber, M.E. Cascading risks: Understanding the 2021 winter blackout in Texas. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 77, 102106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babatunde, O.M.; Munda, J.L.; Hamam, Y. Power system flexibility: A review. Energy Rep. 2020, 6 (Suppl. S2), 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, J.; Wang, Q.; Chen, S.; Lyu, H.; Liang, G.; Zhao, J.; Dong, Z.Y. On Vulnerability of Renewable Energy Forecasting: Adversarial Learning Attacks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 3650–3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zadjali, S.; Al Maashri, A.; Al-Hinai, A.; Al Abri, R.; Gajare, S.; Al Yahyai, S.; Bakhtvar, M. A Fast and Accurate Wind Speed and Direction Nowcasting Model for Renewable Energy Management Systems. Energies 2021, 14, 7878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, F. Extreme Weather and Renewable Energy: How Do Weather and Climate Interact? Energy Solutions, 19 April 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, G.; Shen, L.; Dong, Q.; Cui, G.; Wang, S.; Xin, D.; Chen, X.; Lu, W. Ultra-short-term Wind Power Forecasting Techniques: Comparative Analysis and Future Trends. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 11, 1345004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobo, J.T. The Importance of Data Around Extreme Weather and Variability in Solar PV. PV Tech, 17 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Nasiri, Y.A.; Al-Hafidh, M.S.M. Three-Component Weather-Sensitive Load Forecast Using Smart Methods. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Energy and Power (ICEP 2021), Chiang Mai, Thailand, 18–20 November 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rangelova, K.; Jones, D.; Fulghum, N. Powering Through the Heat: How 2024 Heatwaves Reshape Electricity Demand. Ember, 5 March 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X.; Sun, Y.; Yang, Y.; Mao, Z. Controllable Renewable Energy Scenario Generation Based on Pattern-guided Diffusion Models. Appl. Energy 2025, 398, 126446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; He, G.; Che, L. Conditional Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Model Based Ante-hoc Explainable Scenario Generation for Power Systems Dispatch. Energy 2025, 33, 137115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wei, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, B.; Wang, Y. Multi-Energy Optimal Dispatching of Port Microgrids Taking into Account the Uncertainty of Photovoltaic Power. Energies 2025, 18, 3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhong, J. Risk Assessment of Power Systems Under Extreme Weather Conditions—A Review. In Proceedings of the IEEE Manchester PowerTech, Manchester, UK, 18–22 June 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Lu, H.; Lin, J.; Yin, X. Long-Term Risk Evaluation of Power System Considering Extreme Weather Events. In Proceedings of the 2023 5th Asia Energy and Electrical Engineering Symposium (AEEES), Chengdu, China, 23–26 March 2023; pp. 753–757. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; He, C. Risk Assessment of Power System Under Extreme Typhoon Events. In Proceedings of the 2023 5th Asia Energy and Electrical Engineering Symposium (AEEES), Chengdu, China, 23–26 March 2023; pp. 724–728. [Google Scholar]

- Lakshita, L.; Nair, N.-K.C. Extreme Weather Risk Framework for Power System Location-based Resilience Assessment. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Power Systems Technology (POWERCON), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 12–14 September 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, J.; Rijo, T.; Mar, A.; César, A.; Fortes, P.; Calvão, T.; Raiyani, K.; Pereira, P.; Pires, V.F. Framework for Risk Assessment of the Electrical Power Grid Under Extreme Weather Conditions. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 18th International Conference on Compatibility, Power Electronics and Power Engineering (CPE-POWERENG), Gdynia, Poland, 24–26 June 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, G.; Shi, J.; Chen, B.; Qi, Z.; Wang, L. Risk Assessment of Power Supply Security Considering Optimal Load Shedding in Extreme Precipitation Scenarios. Energies 2023, 16, 6660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalva, M.G.; Gazoli, J.R.; Filho, E.R. Comprehensive Approach to Modeling and Simulation of Photovoltaic Arrays. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2009, 24, 1198–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lydia, M.; Kumar, S.S.; Selvakumar, A.I.; Kumar, G.E.P. A Comprehensive Review on Wind Turbine Power Curve Modeling with Special Emphasis on the Combined Power Curve. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 30, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Piette, M.A.; Chen, Y.; Lee, S.C.; Taylor-Lange, S.C.; Zhang, R.; Sun, K.; Price, P. Commercial Building Energy Saver: An Energy Retrofit Analysis Toolkit. Appl. Energy 2015, 159, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, C.E.; Williams, C.K.I. Gaussian Processes for Machine Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Alargt, F.S.; Khalifa, Y.M.; Kharaz, A.H. Generation of a TMY for Tripoli City Using the Finkelstein –Schafer Statistical Method. In Proceedings of the IECON 2021—47th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Toronto, ON, Canada, 13–16 October 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Takriti, S.; Krasenbrink, B.; Wu, L.S.Y. Incorporating Fuel Constraints and Electricity Spot Prices into the Stochastic Unit Commitment Problem. Oper. Res. 2000, 48, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Huang, Y.; Yang, H.; Hou, H.; Wu, X. Damage Analysis of Distribution Network in Super Typhoon Mangkhut. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 155, 822–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.J.; Wollenberg, B. Power Generation, Operation, and Control, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Billinton, R.; Allan, R.N. Reliability Evaluation of Engineering Systems: Concepts and Techniques, 2nd ed.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, X.; Sedzro, K.S.; Yuan, H.; Ye, H.; Hodge, B.-M. Deliverable Flexible Ramping Products Considering Spatiotemporal Correlation of Wind Generation and Demand Uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2019, 35, 2561–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Xiong, W.; Yang, Z.; Sun, B. A Fast Risk Assessment Method for Power System Considering Wind Power Uncertainty. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 8th Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration (EI2), Shenyang, China, 29 November–2 December 2024; p. 5252. [Google Scholar]

- Subcommittee, P.M. IEEE Reliability Test System. IEEE Trans. Power Appar. Syst. 1979, PAS-98, 2047–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASA. NASA POWER Data Access Viewer. Langley Research Center. 2024. Available online: https://power.larc.nasa.gov/data-access-viewer/ (accessed on 23 June 2024).

- Zarketa-Astigarraga, A.; Penalba, M.; Martin-Mayor, A.; Martinez-Agirre, M. Impact of turbulence and blade surface degradation on the annual energy production of small-scale wind turbines. Wind Energy 2023, 26, 1217–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).