Abstract

The aluminum electrolysis industry is a typical high-energy-consumption and high-carbon-emission sector, and its low-carbon transformation is crucial for achieving “dual-carbon” goals. However, aluminum electrolysis is constrained by thermodynamic safety limits, and conventional dispatch models also often overlook carbon emission trading and the integrated utilization of waste heat. To address these challenges, a low-carbon economic dispatch method considering production safety constraints is proposed in the paper for integrated energy systems in aluminum electrolysis, aiming to enhance wind power utilization and ensure operational safety. First, a load model incorporating thermodynamic safety constraints is developed, and a thermal dynamics equation of electrolytic cells is established to characterize the temperature dynamics of aluminum loads. Then, a bi-level optimization framework for the power–aluminum system is constructed: the upper level minimizes grid power-supply costs by coordinating thermal, wind, and photovoltaic generation, while the lower level maximizes enterprise profit, balancing production safety and economic efficiency to achieve coordination between the system and enterprise layers. Finally, a tiered carbon trading mechanism and waste heat heating model are integrated into the framework, combined with a second-order RC building thermal inertia model to realize coordinated optimization among electricity, heat, and carbon flows. The simulation results demonstrate that the proposed method effectively reduces carbon emissions while ensuring electrolytic cell safety: with carbon trading, emissions decrease by 7.2%; when incorporating waste heat utilization reduces boiler heating emissions, they decrease by 74.7%; and further considering building thermal inertia increases wind power utilization to 99.6%, achieving the coordinated optimization of electricity–heat–carbon systems.

1. Introduction

Flexible production utilizing renewable energy is a critical approach to maintaining competitiveness in the aluminum electrolysis industry. However, existing load regulation strategies for aluminum electrolysis fail to adequately incorporate the safety requirements of chemical production processes, consequently limiting their operational flexibility in power systems with high renewable energy penetration. Current research primarily concentrates on modeling the participation of aluminum electrolysis in power system dispatch operations. The authors of [1] implemented a steady-state safety constraint by restricting the total input power of aluminum electrolysis loads within a specified period, ensuring that it exceeds the thermal energy required to maintain heat balance in the electrolytic cells. Reference [2] models aluminum electrolysis loads as conventional curtailable loads with penalty mechanisms, completely disregarding the essential safety requirements of electrochemical production processes. The authors of [3] investigated the power transfer characteristics of aluminum electrolysis loads in relation to production rates, yet focused exclusively on establishing the production–power relationship while neglecting safety operation modeling. The authors of [4,5,6] established equivalent circuit models to represent the dynamic behavior of aluminum electrolytic cells, enabling their involvement in frequency regulation control, while neglecting essential safety constraints in operation. References [7,8] propose multiple operational states for aluminum electrolysis loads and impose safety restrictions through daily state transition limits (state transition constraints) and adjustment frequency caps (adjustment frequency constraints). These models establish constraints across multiple dimensions including day-ahead operational limits, state transitions, and power restrictions. Nevertheless, these modeling approaches fail to properly account for the unique safety characteristics inherent to aluminum electrolytic cell production as a chemical industrial process, particularly regarding production safety. The capability of these models to guarantee operational safety in real aluminum electrolysis plants has not yet been validated, underscoring a critical deficiency in existing research approaches.

Research on industrial enterprises’ participation in carbon emission trading is an imperative consideration for the development of high-carbon emission industries. Existing studies on power system optimization have incorporated various carbon trading mechanisms. Reference [9] establishes a bi-level game-theoretic model with the objective of optimizing benefits for industrial park operators and heterogeneous industrial loads. The upper level optimizes dynamic pricing strategies under carbon emission trading mechanisms, while the lower level optimizes energy management strategies for industrial loads to maximize profits. The authors of [10] investigated the impact of carbon trading mechanisms on the operation of combined cooling, heating, and power-integrated energy systems. The authors of [11] applied a tiered carbon trading mechanism to the dispatch of electricity–gas–heat–hydrogen integrated energy systems in low-carbon industrial parks, incorporating power-to-hydrogen and hydrogen storage equipment. Reference [12] proposes corresponding low-carbon dispatch strategies for AC/DC hybrid distribution networks. References [13,14] introduce a graded carbon trading mechanism suitable for electric vehicles. Reference [15] presents a hybrid game-based multi-park integrated demand response strategy in a joint electricity–carbon market, addressing the issues of high costs and significant carbon emissions in multi-park integrated demand response. The authors of [16,17] describe optimization dispatch strategies for hydrogen-integrated energy systems under a green certificate carbon trading fusion mechanism. Currently, research on aluminum electrolysis production scheduling considering carbon emission trading mechanisms remains relatively scarce. In particular, aluminum electrolysis production scheduling, which incorporates tiered carbon trading mechanisms with penalty effects, is even less common, making further research in this area urgently needed.

The integrated use of energy sources like electricity, heat, and cooling enhances the overall energy efficiency of consumption systems. In particular, the integrated energy utilization of waste heat and residual heat in industrial enterprises can effectively reduce carbon emissions. The authors of [18] employed an energy hub model to examine the impact of the accuracy of model parameters for different energy conversion equipment in the dispatch process of integrated energy systems. Study [19] proposes an integrated electricity–heat energy dispatch model for industrial parks, incorporating a flexible thermoelectric response model for generation units. The authors of [20] presented a day-ahead economic dispatch method for an integrated electricity–water–heat energy system that includes a high proportion of fluctuating renewable energy sources such as photovoltaic and solar thermal power. Study [21] establishes a multi-objective household electricity–heat joint optimization dispatch model with the goals of minimizing energy purchase costs and optimizing thermal comfort. The authors of [22] investigated the energy optimization dispatch strategy for park-level integrated energy systems and the issue of user dissatisfaction. The authors of [23,24] proposed an optimized dispatch strategy for industrial park integrated energy systems that includes electric vehicle load. Current research on integrated energy system dispatch in industrial parks primarily focuses on electricity, cooling, heat, and hydrogen, with most studies targeting the dispatch of thermal production equipment, such as electric boilers and combined heat and power systems.

In summary, most existing studies treat electrolytic aluminum (EAL) loads as curtailable demand or approximate them through power or state-transition constraints, without adequately capturing thermodynamic and temperature dynamics to ensure safe operation. Carbon trading mechanisms are usually modeled at the system level with an emphasis on overall emission reduction, without considering the enterprise-level decision-making process. In addition, integrated energy scheduling for EAL production has rarely been investigated, and little attention has been paid to industrial waste heat recovery and building thermal inertia, leading to insufficient representation of energy coupling.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

(1) An EAL load model that considers production safety constraints is established. The DC power consumption–output model, thermodynamic model, temperature dynamic simulation model, and safety constraint model of electrolytic cells are sequentially constructed, providing a fundamental basis for subsequent research. By capturing the thermodynamic characteristics and temperature dynamics of EAL cells, safety conditions ensuring stable and secure production are obtained.

(2) To address the limitations of global-level carbon pricing, where carbon price signals are often weakened during transmission and fail to reflect enterprise-specific production constraints, this study establishes a power–carbon coordinated bilevel optimization framework. In this framework, the carbon emission cost is introduced into the electrolytic aluminum load model under production safety constraints and combined with a stepwise carbon trading mechanism. This design enables carbon price signals to be fully captured at the enterprise level and dynamically fed back to the system layer, allowing the carbon price to directly influence production scheduling decisions and thereby enhancing the regulatory effectiveness of carbon market signals.

(3) A coordinated aluminum–heat cogeneration integrated energy scheduling system is developed, establishing a collaborative optimization framework that couples electrolytic aluminum loads, waste heat recovery, and building heating. The proposed system models the coupling between electrical and thermal energy flows and load responses, enabling efficient utilization of industrial waste heat within the integrated energy system and improving overall system coordination and operational performance.

2. Two-Level Optimization Framework

The dispatch strategy, which utilizes renewable energy and the inherent flexibility of electrolytic aluminum systems, represents a complex multi-stakeholder optimization challenge that involves both grid operators’ interests and aluminum producers’ benefits, where grid operators typically represent societal welfare by aiming to minimize overall power supply costs, while aluminum producers seek to maximize their own profits, with their strategic interaction naturally reaching an equilibrium state through market mechanisms; in actual operations, aluminum producers treat production data and output information as confidential business intelligence. Building upon the established electrolytic aluminum load modeling framework, this section proposes a novel electricity–aluminum bilevel optimization dispatch strategy that incorporates production safety constraints, employing a bilevel optimization model to formulate this equilibrium problem in system dispatch where the upper-level power dispatch model coordinates electricity distribution, while the lower-level model comprehensively considers aluminum production constraints and building heating requirements with thermal inertia limitations that define thermal demand parameters. Additionally, the latter incorporates carbon emission trading constraints to ensure operational safety, energy efficiency, and environmental compliance while maintaining necessary commercial confidentiality protections throughout the coordinated optimization process.

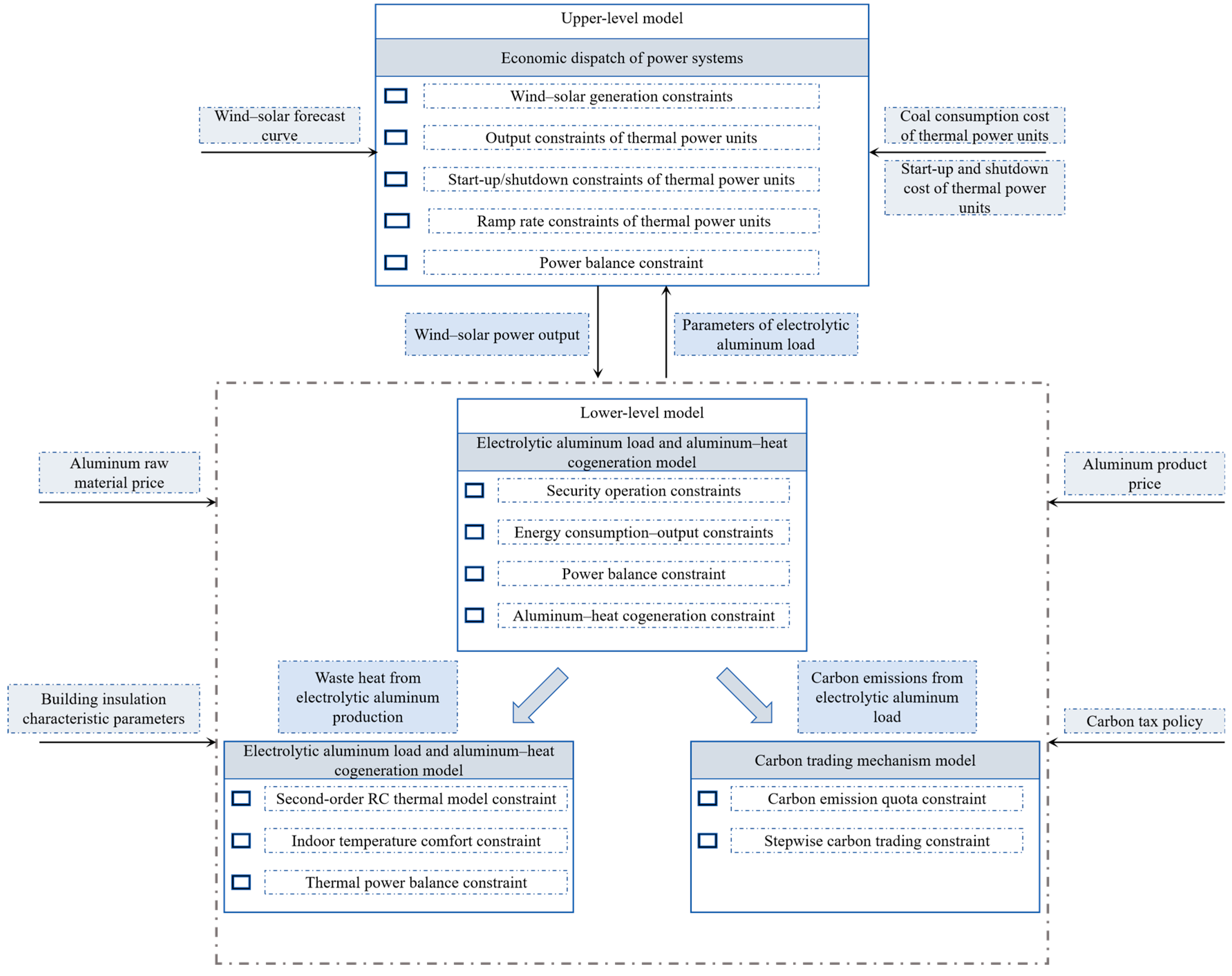

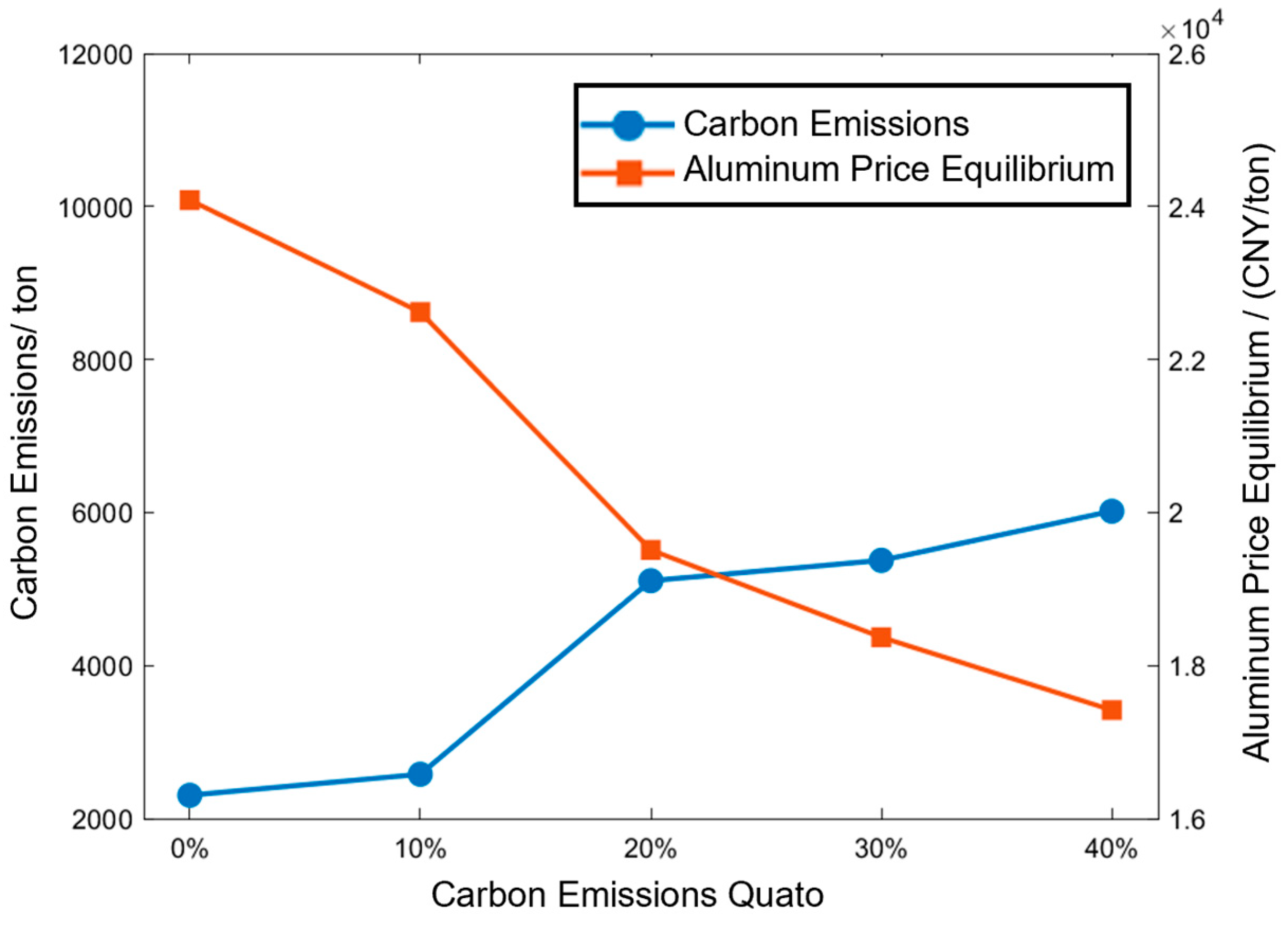

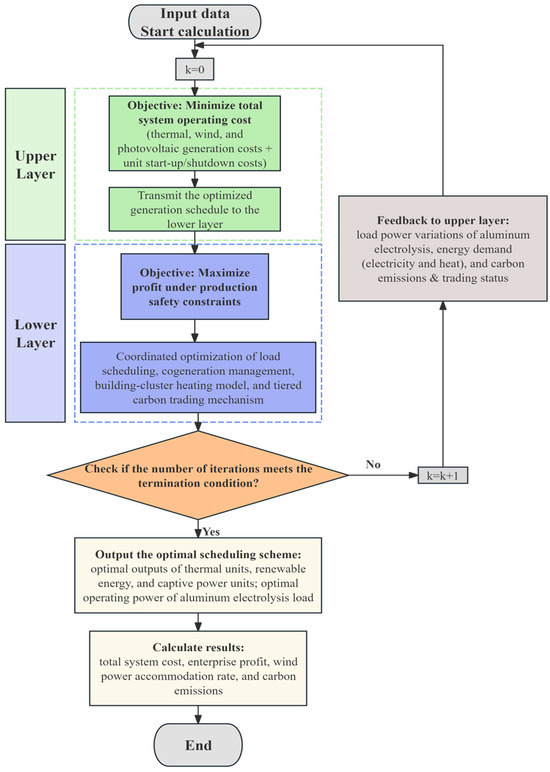

As illustrated in Figure 1, the overall system architecture consists of an upper-level model and a lower-level model, forming a source–load collaborative bi-level optimization framework. The upper-level model represents the economic dispatch of the power system, managed by the grid operator. As inputs, it uses the forecasted outputs of wind and photovoltaic renewable generation, together with conventional load predictions, and determines the optimal generation mix and output levels of thermal and renewable units. The optimization is subject to wind–solar output constraints, thermal unit output limits, start-up/shutdown constraints, ramp-rate limits, and power–balance constraints, aiming to minimize the total system operating cost while ensuring safe and stable operation. The optimized results from the upper level, such as generation schedules and electricity price signals, are subsequently transmitted to the lower-level model.

Figure 1.

Double-layer framework structure diagram.

The lower-level model, operated by the electrolytic aluminum enterprise, comprises three interconnected sub-models: the electrolytic–aluminum load and aluminum–heat cogeneration model, the building cluster heating model, and the stepwise carbon trading mechanism model. These sub-models are coupled through both energy flow and information flow to realize integrated load-side optimization. The electrolytic–aluminum cogeneration model uses the renewable generation outputs from the upper level as key inputs and optimizes cell operating power, energy consumption–output ratio, and waste heat recovery according to process characteristics. The recovered electrolysis heat is then supplied to the building cluster heating model to satisfy the heating demand. The building cluster model employs a second-order RC thermal model to characterize building insulation, dynamically adjusting heating power while satisfying indoor temperature–comfort and thermal–power–balance constraints to achieve optimal heat distribution. In addition, the stepwise carbon trading mechanism model imposes carbon-emission quotas and stepwise carbon trading constraints on the entire production system. Based on the carbon price signals, it adjusts the objective functions of the other sub-models to coordinate production planning with carbon cost management, thereby achieving both economic and environmental objectives.

Finally, upper-level dispatch and lower-level optimization interact through the exchange of power and information. The grid-side optimization enhances renewable-energy utilization, while the load-side response balances energy consumption and carbon emissions. Consequently, the proposed source–load collaborative framework ensures grid stability, promotes energy conservation and emission reduction for the enterprise, and maximizes the system benefits.

3. Bi-Level Optimization Scheduling Model

3.1. Upper-Level Power Grid Optimization Scheduling Model

The model takes minimum power supply cost as its optimization objective, subject to renewable generation output constraints, thermal power unit commitment, and generation capacity constraints. Its objective function is expressed as follows:

where , , , , and represent the electricity cost of thermal power, wind power, and photovoltaic power, as well as the startup and shutdown costs of generators during the dispatch period, respectively. and denote the startup and shutdown costs of unit . The binary decision variables , , and indicate the operating status (1 for online, 0 for offline), startup action (1 for starting up, 0 otherwise), and shutdown action (1 for shutting down, 0 otherwise) of generator , respectively. The coefficients , , and represent the coal consumption cost parameters of thermal power units, where denotes the output of thermal power unit during time period , and is the total number of thermal power units. represents the operating cost coefficient of wind power units, with being the output of wind farm at time , and being the number of dispatched wind farms. Similarly, is the operating cost coefficient of photovoltaic plants, where denotes the output power of PV plant at time , and is the number of scheduled PV plants. The dispatch horizon is set to 24 h in this study, with representing the dispatch interval, specified as 1 h. The linearization method is as follows:

Equation (2) must be linearized to maintain the model’s linearity.

where represents the breakpoint, and and are auxiliary parameters.

In addition, the ramping ability and start–stop conditions of thermal power units need to be restricted. Therefore, the thermal power unit model is applied in accordance with Equations (11)–(20). Equations (16)–(18) define the operating status constraints of each thermal unit, while Equations (19) and (20) specify the minimum duration requirement for every state.

where represents a certain moment in the past time, with and being interchangeable; and denote the minimum up-time and down-time of generator ; and , , , and represent the ramp-up limit, ramp-down limit, startup power, and shutdown power of unit , respectively.

The output constraints for wind and photovoltaic (PV) generation are as follows:

3.2. Lower-Level Optimization Scheduling Model

3.2.1. Equivalent Circuit Model of Electrolytic Series

The electrolytic aluminum load series is composed of multiple electrolytic cells, which are powered by converting alternating current into direct current. The relationship expression between cell voltage and current is as follows:

where and are the DC voltage and current of the electrolytic series, respectively; denotes the power consumption of the electrolytic cells; represents the total resistance of the electrolytic series; and is the sum of the electrochemical reaction voltages of the electrolytic series.

The aluminum production rate has a linear relationship with the electrolyzer current. When regulating the electrolytic aluminum load, certain production requirements need to be satisfied.

where represents the output of aluminum products; denotes the electrochemical equivalent of aluminum; is the current efficiency of the electrolytic aluminum series; and represents the number of electrolytic cells.

3.2.2. Thermal Balance Analysis of the Electrolytic Cell

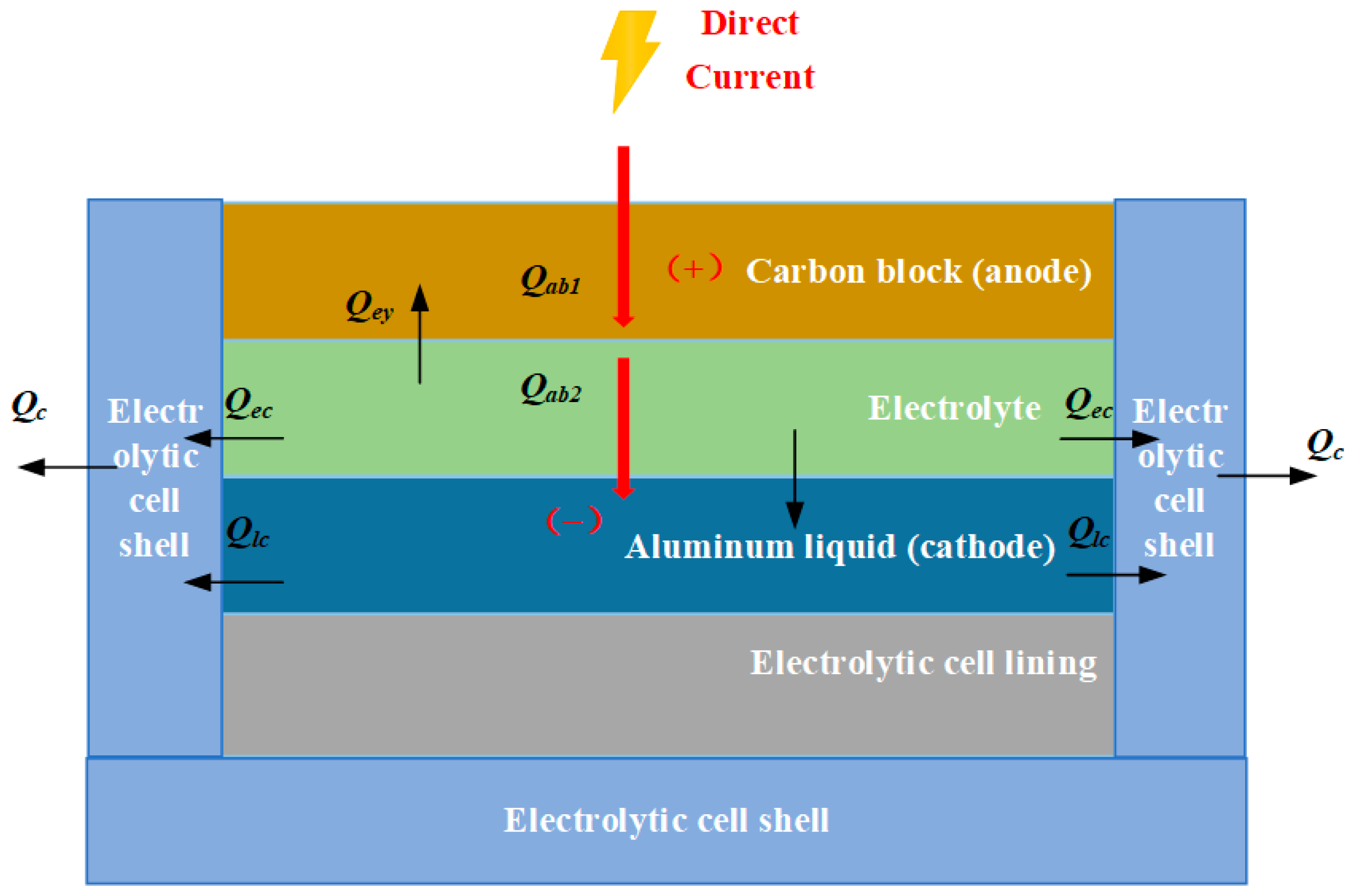

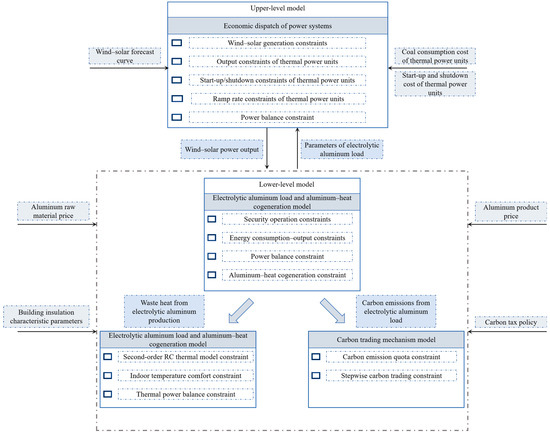

For ease of analyzing the thermal balance model of the electrolytic cell can be divided into two parts: the thermal balance between the electrolyte and liquid aluminum, and the thermal balance between the cell shell and anode carbon blocks (refer to Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Thermal balance diagram of the aluminum electrolytic cell.

Inside the cell, the temperatures of the electrolyte and liquid aluminum are assumed to be uniformly distributed. Consequently, the thermal equilibrium equation for the electrolyte–aluminum system is formulated as follows:

For the electrolyte–molten aluminum system, since the electrochemical reactions occur at the interface between the electrolyte and the molten aluminum, the electrolyte is selected as the primary object of analysis. Considering the heat exchange between the electrolyte and the surrounding media, as well as the internal heat losses within the system, the total heat balance can be expressed as shown in Equation (26).

In this equation, , , and represent the heat generated by the current passing through the electrolyte, the heat absorbed during the electrochemical reactions, and the heat required for heating the raw materials, respectively. and denote the heat dissipated from the electrolyte to the sidewall of the cell shell and to the anode carbon blocks at the top, respectively. indicates the heat exchanged between the electrolyte and the molten aluminum. is the specific heat capacity of the electrolyte, is its mass, and represents the temperature variation in the electrolyte.

Taking the molten aluminum as the object of study, its heat balance can be expressed as shown in Equation (27).

In this equation, and represent the heat generated by the internal reactions within the molten aluminum and the heat dissipated from the molten aluminum to the sidewall of the cell shell, respectively. is the specific heat capacity of the molten aluminum, is its mass, and denotes the temperature variation in the molten aluminum.

During the electrolytic aluminum production process, the molten aluminum and the molten electrolyte remain in a state of continuous dynamic circulation, which promotes a uniform temperature distribution within the system. Based on this characteristic, the temperature difference between the electrolyte and the molten aluminum can be considered negligible. Therefore, in the thermodynamic analysis, the two phases can be treated as a single integrated system. Under this simplified assumption, the electrolyte and the molten aluminum exhibit synchronous temperature variations, =, Equations (26) and (27) can be combined and expressed as follows:

In this equation, represents the total heat generated by the electric current input into the aluminum electrolytic cell. The aluminum electrolysis reaction itself is an endothermic process, meaning that a portion of the electrical energy supplied to the cell is consumed by the electrochemical reactions, while the remaining energy is released in the form of heat. Therefore, the expression for the heat generated by the current in the aluminum electrolytic cell can be written as follows:

In this equation, denotes the thermal neutral voltage of the electrolytic cell. It is noteworthy that, according to Equation (28), in the absence of an external heat source, the aluminum electrolysis reaction cannot be sustained when the voltage across the electrolytic cell is lower than the thermal neutral voltage. The alumina raw material is conveyed into the electrolytic cell through a dense-phase pneumatic conveying system, and during the heating process to reach the reaction temperature, continuous heat absorption is required. The corresponding heat quantity, can be expressed as follows:

In this equation, represents the equivalent electrical energy consumption required for heating the raw materials per ton of aluminum produced, which is approximately 0.7 kwh/kg (Al). At the solid–liquid interface, heat transfer occurs through convective heat exchange across the boundary layer. The heat dissipation from the electrolyte and molten aluminum to the sidewall of the cell shell, as well as the heat loss from the electrolyte to the anode carbon blocks at the top, can be calculated using the convective heat transfer equations.

In this equation, denotes the average temperature of the electrolyte–molten aluminum system, and represents the average temperature of the cell shell–anode block system. is the convective heat transfer coefficient between the electrolyte and the sidewall of the cell shell, and is the corresponding heat transfer area. represents the convective heat transfer coefficient between the molten aluminum and the sidewall of the cell shell, and is the heat transfer area between them. denotes the convective heat transfer coefficient between the electrolyte and the anode carbon blocks at the top, while represents the corresponding heat transfer area.

By substituting Equation (30) and rearranging, the differential expression governing the time evolution of the electrolyte–molten aluminum system temperature is obtained as follows:

Situated between the external environment and the electrolyte–molten aluminum system, the cell shell–anode block system conducts heat from inside the cell to the ambient air through the cell shell. Taking the cell shell–anode block system as the object of analysis, its heat balance can be expressed as shown in Equation (32):

In this equation, represents the heat transferred from the electrolyte–molten aluminum system to the cell shell–anode block system, and denotes the heat released from the cell shell–anode block system to the ambient air. is the specific heat capacity of the cell shell–anode block system, is its mass, and represents the variation in its average temperature. The heat transferred from the electrolyte–molten aluminum system to the cell shell–anode block system includes the heat dissipation from both the electrolyte and molten aluminum to the sidewall of the cell shell, as well as the heat loss from the electrolyte to the anode carbon blocks at the top, which can be expressed as follows:

The heat transferred from the cell-shell–anode block system to the ambient air can be calculated using the convective heat transfer equation.

In this equation, denotes the convective heat transfer coefficient between the cell shell–anode block system and the ambient air; is the corresponding heat transfer area; and is the ambient temperature.

By substituting Equations (30), (33), and (34) into Equation (32) and rearranging, the differential expression governing the time evolution of the average temperature of the cell shell–anode block system is obtained:

By discretizing Equations (31) and (36), the expressions for the corresponding output can be obtained, as shown in Equations (37)–(40).

3.2.3. Electrolytic Aluminum Load Production Constraints

One of the most important and easily controllable factors in aluminum electrolysis load is the temperature of the electrolyte in the electrolytic cell. During the process, the temperature of the electrolyte must be maintained within a certain temperature range. If the temperature is too low, the electrolyte solidifies on the walls and bottom, while the cryolite melt freezes toward the carbon blocks, severely compromising thermal stability. On the other hand, excessive temperature can cause the cryolite melt and corrode the cell walls, thus reducing the electrolyzer’s service life.

where and represent the lower and upper limits of the electrolyte temperature that do not affect normal production.

In theory, aluminum electrolytic cells can be shut down for several hours without irreversible damage; however, such short-term shutdowns are rarely implemented in actual electrolytic aluminum production. Therefore, plant shutdown scenarios are not considered in this study.

In practice, the thermal characteristics of electrolytic cells vary among facilities. Operating continuously near the temperature boundary poses significant safety risks, as thermal equilibrium becomes unstable and even minor disturbances may lead to irreversible cell failures. Based on this, it is more reasonable to define both upper and lower production limits together with a maximum allowable load-shifting duration to ensure system safety and thermal stability. Accordingly, the dynamic operation of aluminum electrolysis can be classified into the following modes:

(1) Reduced-production mode.

This mode corresponds to low-load operation, where the Joule heat generated by the current is insufficient and the cell temperature decreases continuously, resulting in an aluminum output below the rated level.

(2) Rated-production mode.

In this mode, operating parameters such as current, voltage, and feed rate remain within their design ranges, maintaining a stable cell temperature and a steady aluminum production rate.

(3) Overload mode.

This mode represents high-load operation, in which excessive Joule heat generation causes a continuous temperature rise and the aluminum output exceeds the rated level.

In this work, the rated production power is assumed to fluctuate only within a narrow range of 95–105%, while the minimum and maximum production levels are set to 80% and 120% of the rated output, respectively. The safe operating boundaries (i.e., maximum-on and minimum-off durations) are derived from the electro-thermal coupling model given in Equations (31) and (36) under the most adverse operating conditions.

A representative electrolytic aluminum plant situated in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China, has been selected as the primary research subject for investigation. Specifically, the aluminum electrolytic cells employed in this particular plant are characterized by a rated voltage output of 4 volts and a rated current capacity of 400 kiloamperes, with the detailed specifications of their thermal parameters being comprehensively elaborated upon in Table 1 and Table 2 of the present work. It is noteworthy that the operating temperature of the electrolyte within these cells is strictly constrained to lie within the range of 940 to 960 degrees Celsius. The simulation results that correspond to the aforementioned operational parameters are subsequently presented in the following sections.

Table 1.

Electrolytic cell parameters.

Table 2.

The convective heat transfer coefficients and heat transfer areas of each part of the electrolytic cell.

3.2.4. Lower-Level Objective Function

The objective function is to maximize the revenue of the electrolytic aluminum plant:

where represents the raw material cost; denotes the revenue from aluminum production; represents the coal consumption cost of self-owned generating units; denotes the cost of purchasing electricity; indicates the carbon emission cost; and is the revenue from heat sales.

The above cost term can be expressed as follows:

where is the selling price of aluminum products; is the production volume of finished aluminum at time ; and denote the raw material price of the electrolytic aluminum plant and the additional costs incurred in other production processes, respectively; , , and represent the purchase prices of wind power, photovoltaic power, and thermal power, respectively; and , , and are the amounts of wind power, photovoltaic power, and thermal power procured at time .

where is the carbon emission allowance, is the allowance coefficient representing the carbon emission quota allocated per unit of power, and is the actual carbon emissions of the aluminum producer, which mainly consist of three components: denotes the carbon emissions corresponding to net purchased electricity and heat, is the carbon emissions from the producer’s self-owned power plant, and is the carbon emissions generated during the aluminum production process itself.

3.2.5. Carbon Emission Trading Constraints for Aluminum Electrolysis

The carbon emissions associated with grid electricity purchases are

Carbon emissions from self-owned thermal power plants are

Carbon emissions from aluminum production are

where represents the carbon emissions per ton of aluminum produced.

The tiered carbon system enforces stricter penalties for enterprises exceeding the carbon emission limit, with greater excess leading to heavier penalties.

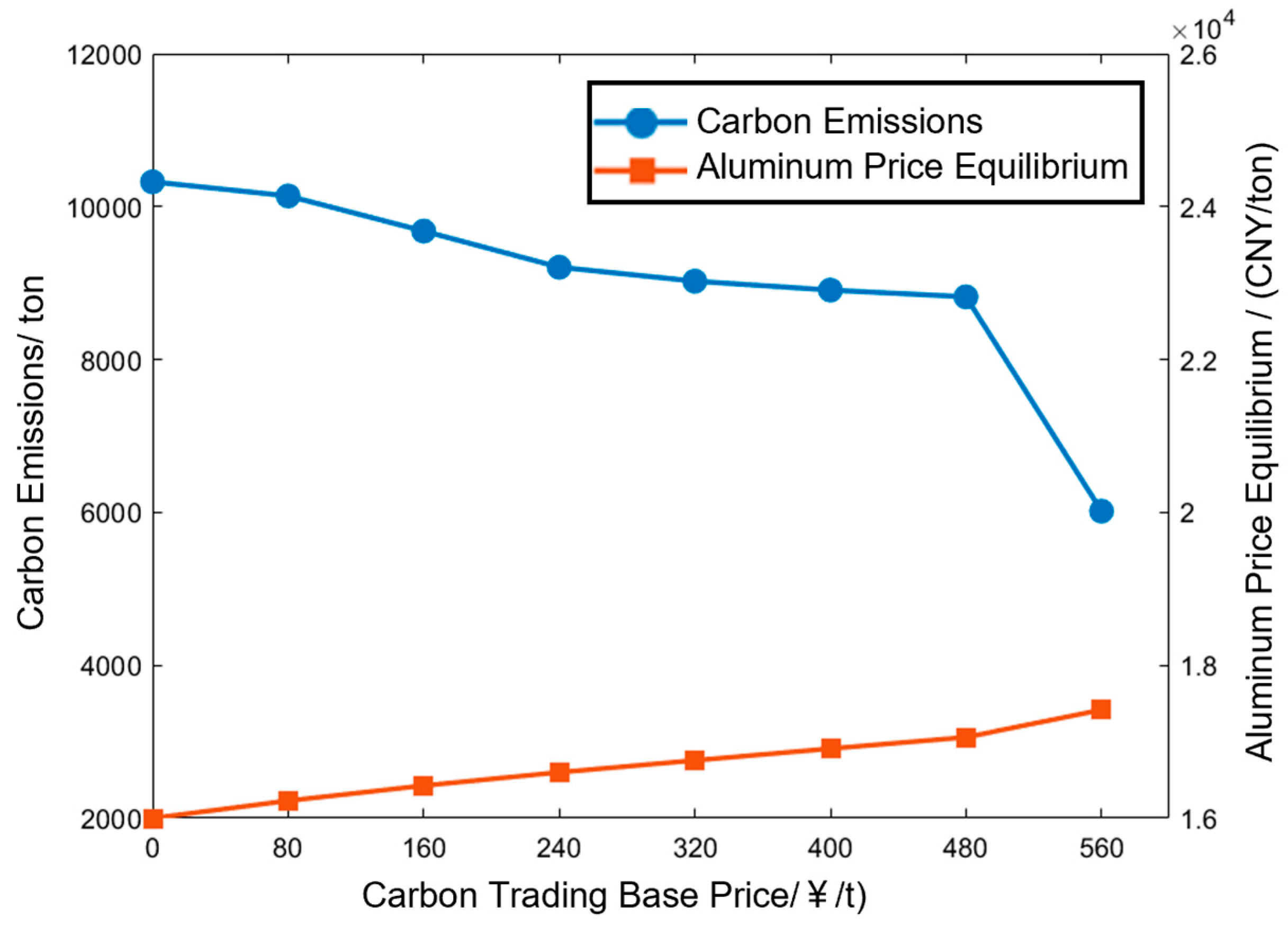

where , , and , respectively, represent the carbon price benchmark value, price growth rate, and carbon emission grade interval span. As illustrated in the figure below, under the tiered carbon pricing mechanism, the unit carbon price increases progressively with higher emission volumes.

Perform linearization processing on Equation (52):

where is a binary variable used to identify and distinguish emission tiers, and and are the coefficient parameters associated with carbon prices in different intervals. These variables and parameters together constitute the key elements describing the piecewise relationship between emission tiers and carbon prices.

The revenue from selling waste heat, denoted by , is expressed as follows:

where represents the selling price of waste heat, is the rated operating power of the aluminum electrolysis process, denotes the heat recovery efficiency, is the waste heat power, u is a binary decision variable (0–1) indicating the operational status, and α is the power coefficient. During the aluminum electrolysis process, the system’s thermal balance must first be ensured to meet the basic heat requirements for production, such as preheating raw materials and processing aluminum ore. The excess heat generated after fulfilling these process demands constitutes the recoverable waste heat.

In Equation (58), represents the product of a continuous variable and a binary decision variable. introduces a nonlinear constraint. To address this, an auxiliary variable z is introduced, and the Big-M method is employed to perform linear relaxation equivalence, thereby enabling efficient problem-solving. Here, M is a sufficiently large positive real number.

3.2.6. Constraints for Utilizing Aluminum Electrolysis Waste Heat in Building Heating Systems

The waste heat generated by aluminum electrolysis plants should be supplied to surrounding buildings. Typically, the heating demand of these buildings is met by thermal boilers. However, waste heat recovery, as a form of resource recycling, offers lower costs for localized heating and should be prioritized. Every effort should be made to utilize waste heat for heating purposes. To determine the heating demand of the surrounding buildings, a second-order RC model is adopted to simulate building heating. Drawing on the equivalent resistance-capacitance model of parallel circuits in electrical circuit theory, the building heating model is formulated as follows:

where and represent the thermal resistances between the indoor air and the wall, and between the wall and the outdoor environment, respectively; and denote the thermal capacitances of the indoor air and the wall structure, respectively; and indicate the temperatures of the indoor space and the wall, respectively; is the heating power supplied to the building; and is the outdoor ambient temperature.

When a building cluster is considered, and represent the equivalent thermal resistances of the cluster, while and denote its equivalent thermal capacitances. and indicate the average indoor and wall temperatures of the cluster, respectively. The aggregate parameters can be derived from the thermal properties of individual buildings using the following method:

During heating operations, the indoor temperature must be maintained within a comfortable range (in this study, set at 18–22 °C):

Thermal power balance constraint for building clusters:

The thermal power input from aluminum electrolysis must not exceed the available waste heat capacity:

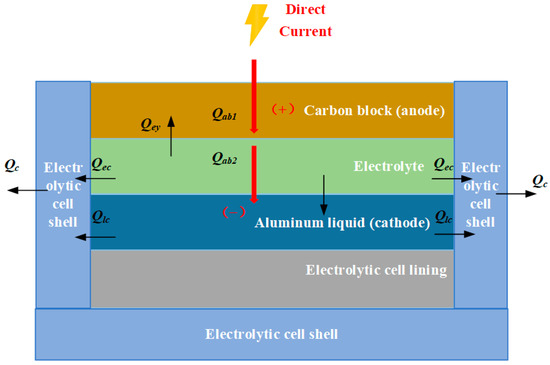

3.2.7. Overall Computational Flowchart of the Two-Level Optimization Framework

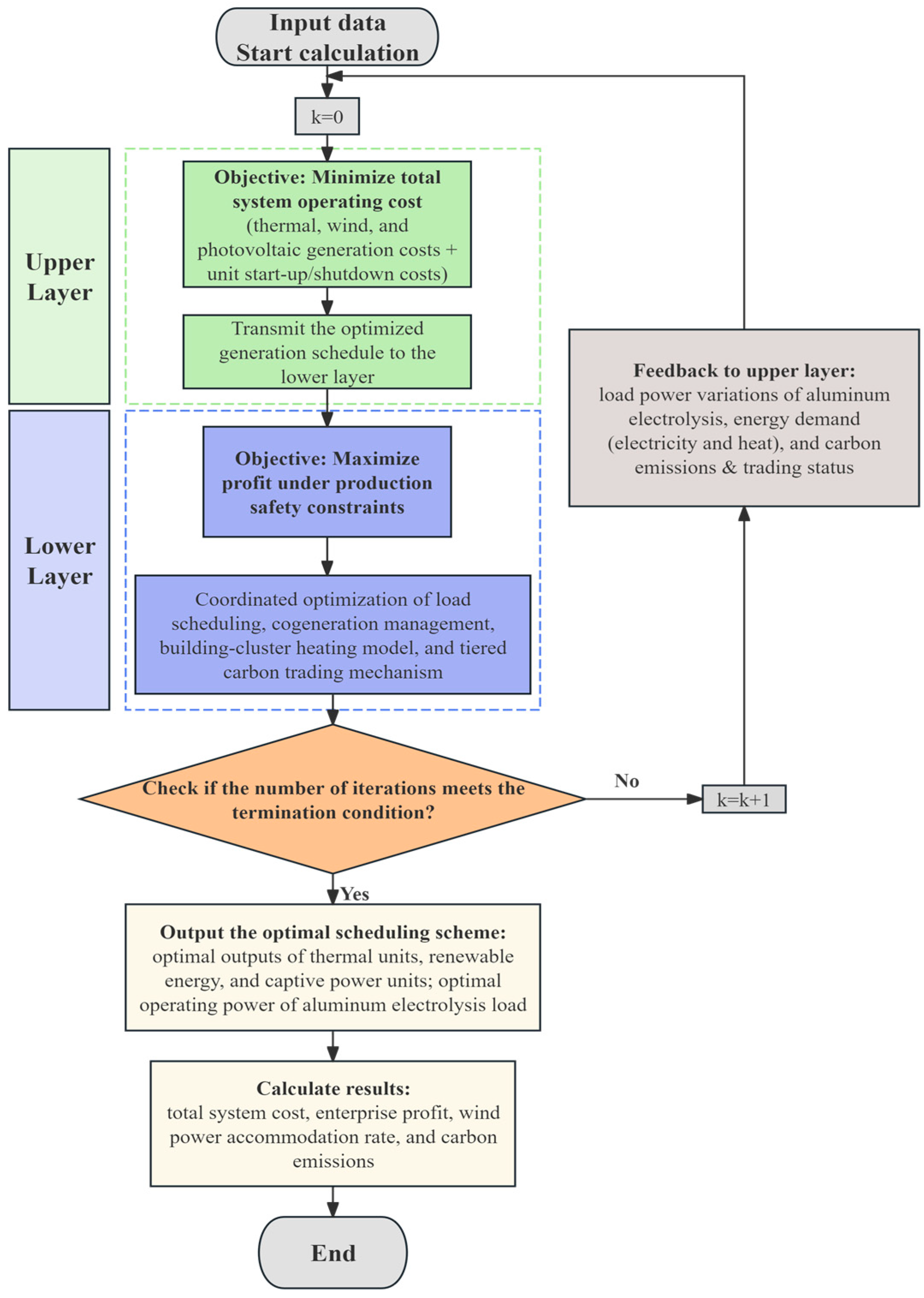

The overall computational process of the proposed model is illustrated in Figure 3. First, the model receives and organizes a series of input data, including the forecasted outputs of wind and photovoltaic power generation, conventional load demand, operational characteristics of thermal power units, and process parameters of aluminum electrolysis. Based on these inputs, the upper-level model performs the economic dispatch optimization of the power system with the objective of minimizing the total operating cost. It comprehensively considers the fuel cost and start-up/shutdown cost of thermal units, the generation characteristics of renewable energy, and power balance and system security constraints in order to determine the optimal generation portfolio of thermal, wind, and photovoltaic units. The resulting electricity price signals and power allocation plans are then transmitted to the lower level. At the lower level, the model carries out enterprise-side scheduling optimization under aluminum production safety constraints. By jointly optimizing the operating power and output of electrolytic cells, the output of captive power plants, the utilization of waste heat for district heating, and carbon trading strategies, the model achieves a comprehensive optimization of load responsiveness and economic performance. Meanwhile, the lower level feeds back key information—including the load response characteristics of aluminum electrolysis, aggregated energy demand (electricity and heat), and carbon emission status—to the upper level to support subsequent iterative dispatch decisions. Through iterative information exchange and coordinated optimization, the two levels progressively achieve source–load collaborative scheduling until convergence is reached. Ultimately, the model outputs the coordinated optimal generation plans for main-grid thermal units, renewable energy sources, captive power plants, and aluminum electrolysis loads, while also calculating comprehensive performance indicators such as total system operating cost, enterprise profit, wind power accommodation rate, and carbon emission levels.

Figure 3.

Overall computational flowchart of the two-level optimization framework.

4. Case Studies

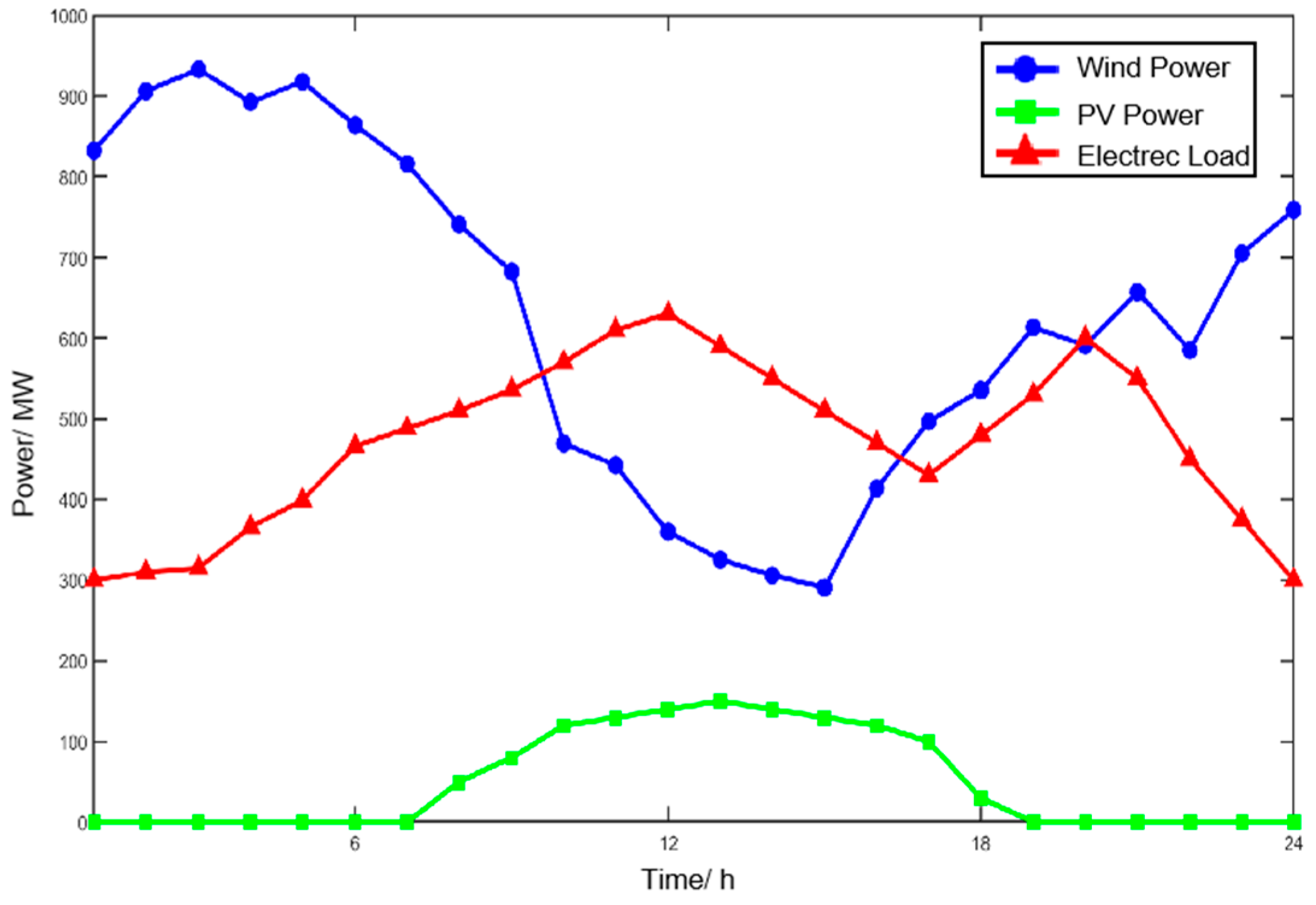

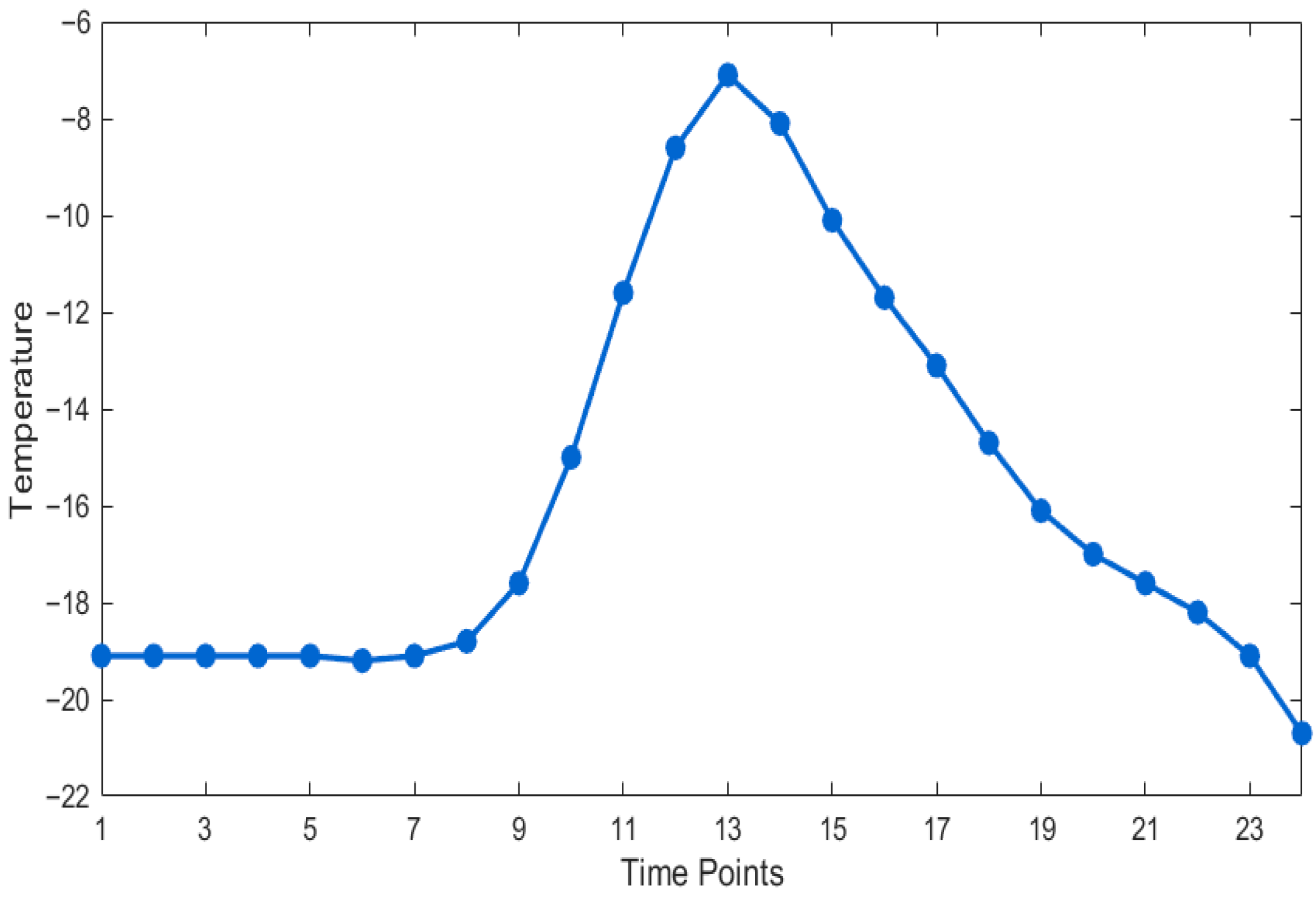

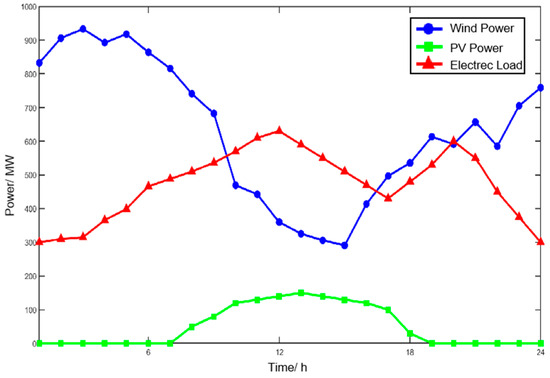

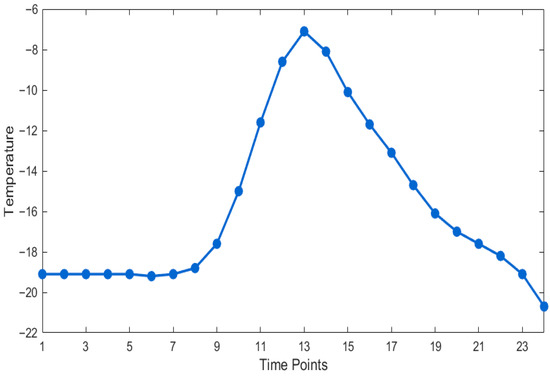

This case study discusses a typical electrolytic aluminum plant located in the Xinjiang region. The upper-level main power grid consists of three thermal power units (CG1–CG3), a wind farm, and a photovoltaic (PV) power station. The lower-level system includes an electrolytic aluminum plant with a rated power of 700 MW and a captive thermal power plant (CGEAL) with a capacity of 330 MW. The detailed parameters of the thermal power units are listed in Table 3, where CG1 and CG3 are set as base-load units. The wind power, photovoltaic generation, and electric load curves of the upper-level grid are shown in Figure 4. The aluminum price is set at 16,000 CNY per ton, and the feed-in tariffs for photovoltaic and wind power are 250 CNY/MWh and 350 CNY/MWh, respectively. The optimization scheduling time step is set to 1 h. In the aluminum electrolysis process, carbon electrodes are consumed, leading to CO2 emissions. The average emission factor for grid-supplied coal-fired power is 0.8 t/MWh, while the captive coal-fired power plants of aluminum producers follow a nonlinear emission model with coefficients , , and . For heating systems, conventional boilers emit 0.3 t CO2/MWh with a heat price of 150 RMB/MWh, whereas waste heat recovered from aluminum electrolysis is priced at 80 RMB/MWh and considered carbon-free. The carbon emission allowance is set at 40% of historical emissions. A tiered carbon pricing scheme is adopted in accordance with the current Chinese carbon market, with a baseline price of 80 RMB/t, a tier interval of 1000 t, and a price escalation rate of 30% per tier. The model further incorporates the typical winter temperature profile of Xinjiang, where nighttime temperatures reach as low as –20 °C, resulting in significant heating demand, while indoor comfort is maintained at 18–22 °C, as shown in Figure 5. The building thermal inertia parameters are summarized in Table 4.

Table 3.

Thermal power unit parameters.

Figure 4.

Forecasted wind–solar generation and load output of the upper level.

Figure 5.

Xinjiang typical winter temperature profile.

Table 4.

Building thermal inertia parameters.

4.1. Dynamic Temperature Simulation Results of the Electrolytic Cell

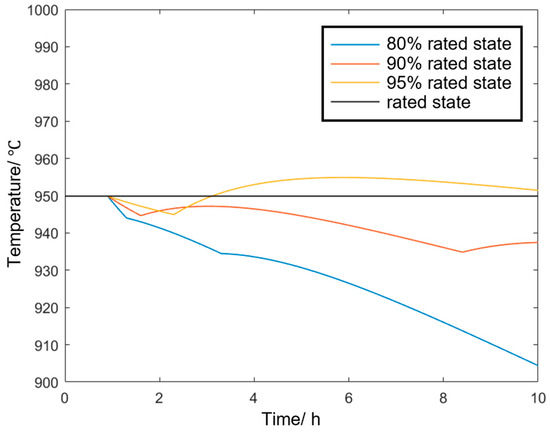

Based on the models established in Table 2 and Table 3 and Section 3.1, the temperature of the electrolyte–molten aluminum system is set to 950 °C, and the temperature of the cell shell–anode carbon block system is set to 834 °C under rated operating conditions. These values are used as the initial conditions for simulating the aluminum electrolytic cell.

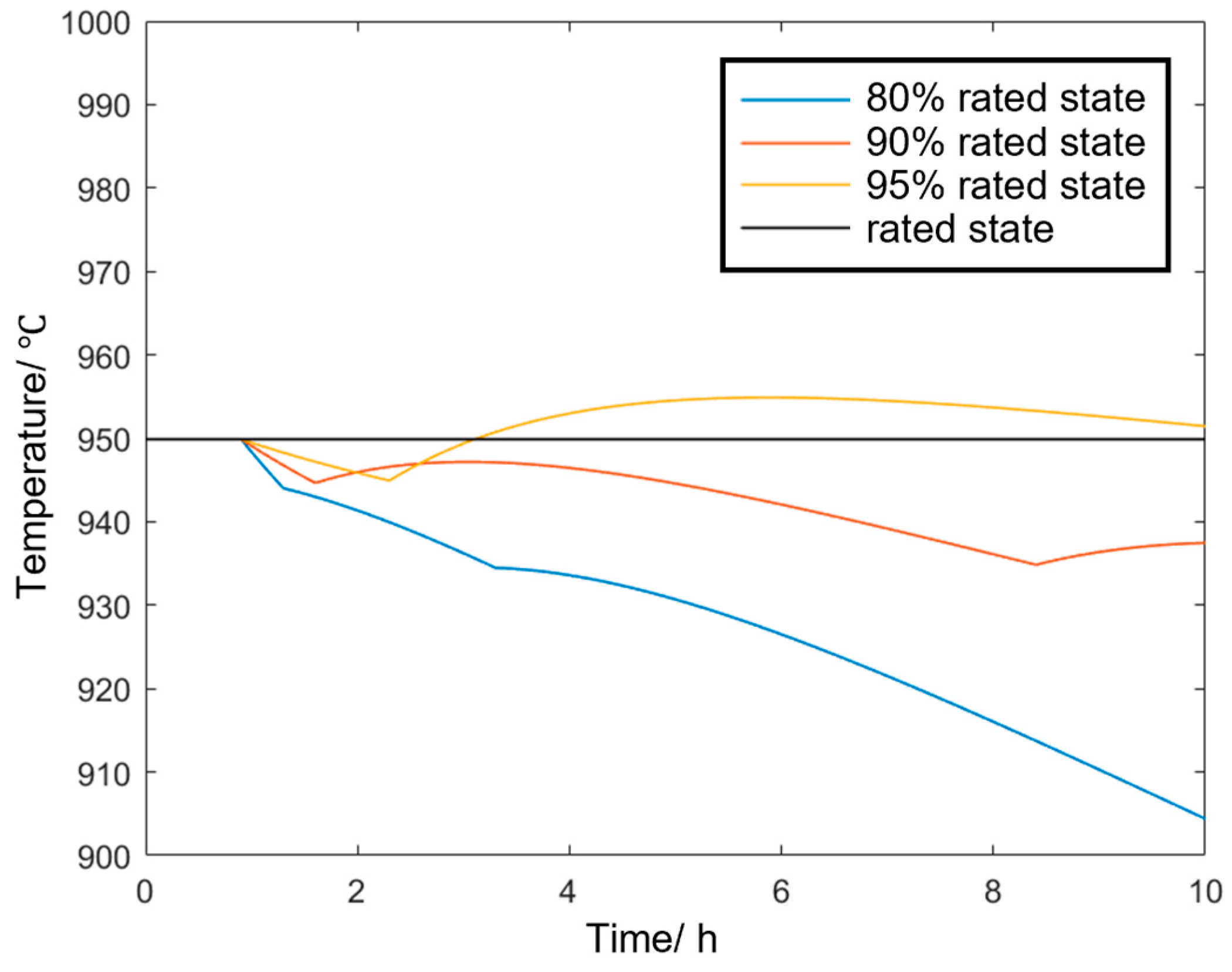

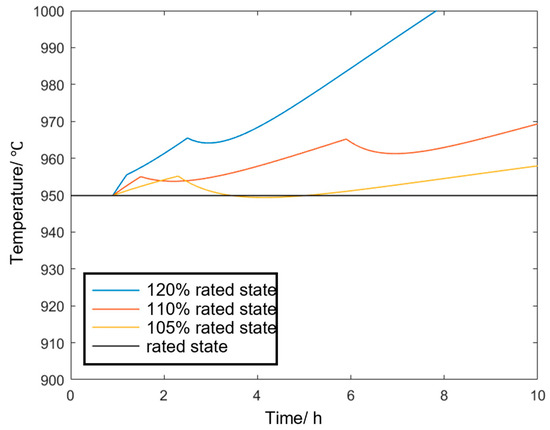

(1) Simulation Scenario 1: Continuous production reduction

The aluminum electrolytic cell enters different levels of continuous production reduction modes, and the temperature variations in the electrolyte–molten aluminum system are shown in Figure 6. It can be observed that when the production is reduced to 95% of the rated power, the aluminum electrolysis plant can restore the temperature through its own temperature regulation mechanism (i.e., by reducing the wind cooling); when the production is reduced to 90% of the rated power, although the plant can slow down the temperature drop through its temperature regulation mechanism, it is unable to restore the temperature to the rated value of 950 °C; when the production is reduced to 80% of the rated power, at the 5.2 h mark, the cell temperature drops below 930 °C, meaning that after 4.2 h of production reduction, the cell temperature exceeds the safety boundary.

Figure 6.

Temperature variation process of the electrolytic cell under different continuous production reduction states.

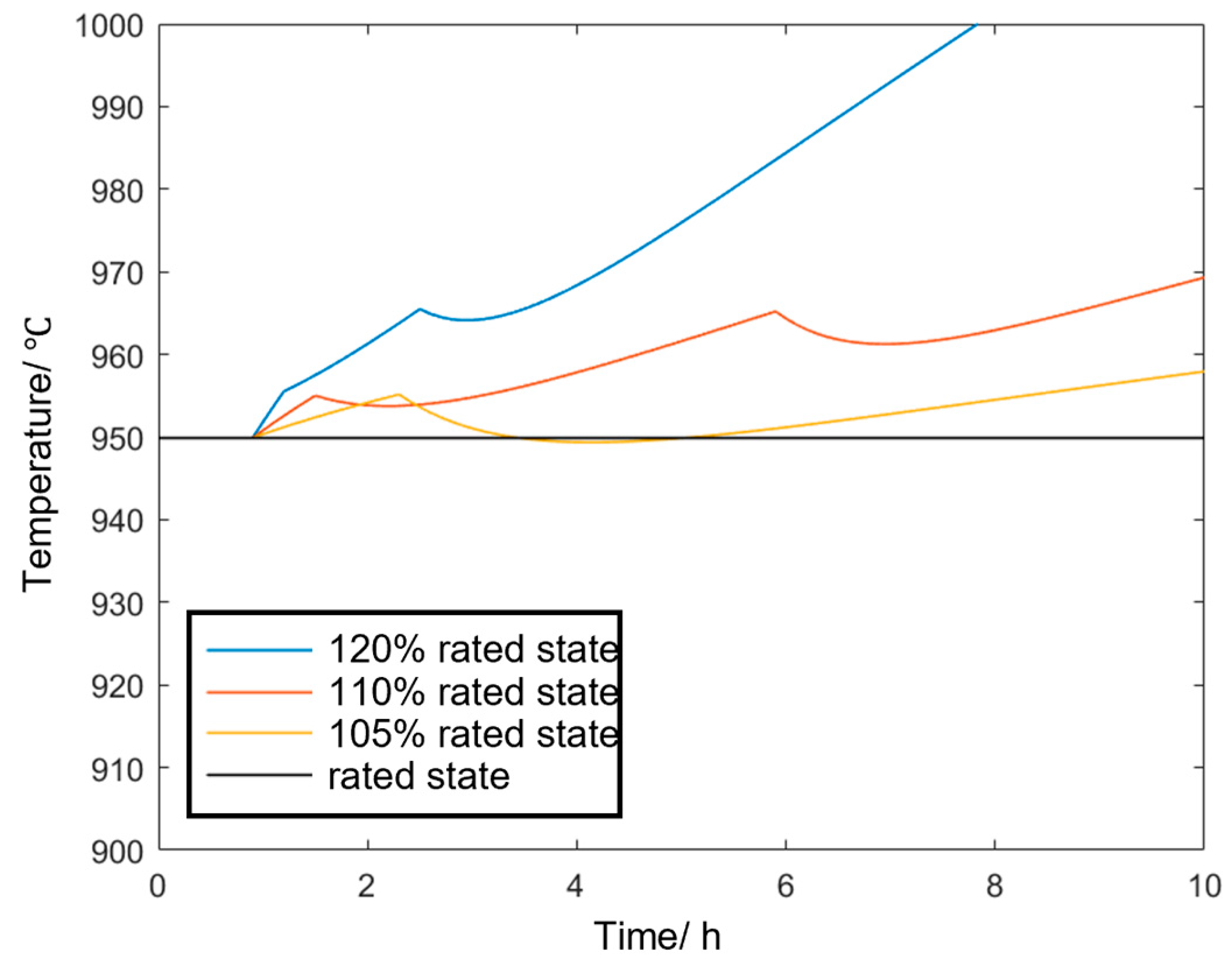

(2) Simulation Scenario 2: Continuous Overload

The aluminum electrolytic cell enters different levels of continuous overload modes, and the temperature variations in the electrolyte–molten aluminum system are shown in Figure 7. It can be observed that when the overload reaches 105% of the rated power, the aluminum electrolysis plant can restore the temperature through its own temperature regulation mechanism (i.e., by increasing wind cooling). When the overload reaches 110% of the rated power, the plant can slow down the temperature rise and partially reduce the temperature through its regulation mechanism, but it cannot restore the cell temperature to the rated value of 950 °C. At 110% of the rated power, the cell temperature exceeds 970 °C at 5.4 h, indicating that after 4.4 h of overload operation, the cell temperature surpasses the safety boundary.

Figure 7.

Temperature variation process of the electrolytic cell under different continuous overload states.

The dynamic temperature characteristic model of the aluminum electrolysis load established in this study can accurately describe the temperature variation process of the electrolytic cell under production reduction and overload modes. It determines the maximum continuous operating durations (4.4 h under the production reduction mode and 4.2 h under the overload mode), providing fundamental constraint conditions for subsequent dispatch optimization.

4.2. Analysis of Dispatch Results

Based on the above parameter configuration, four typical scenarios are designed to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed scheduling model under different coordination strategies and policy mechanisms.

Scenario 0: Power–Aluminum Coordination (without carbon trading mechanism).

Scenario 1: Power–Aluminum–Carbon Coordination (with carbon trading only).

Scenario 2: Power–Aluminum–Carbon–Heat Coordination (without thermal inertia).

Scenario 3: Power–Aluminum–Carbon–Heat Coordination (with thermal inertia).

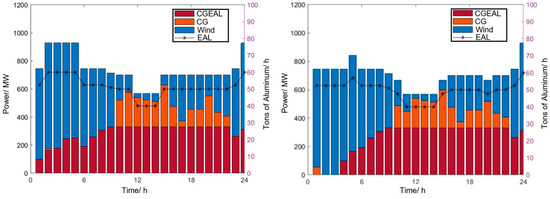

(1) Impact of Carbon Trading Mechanism (Comparison between Scenario 1 and 0).

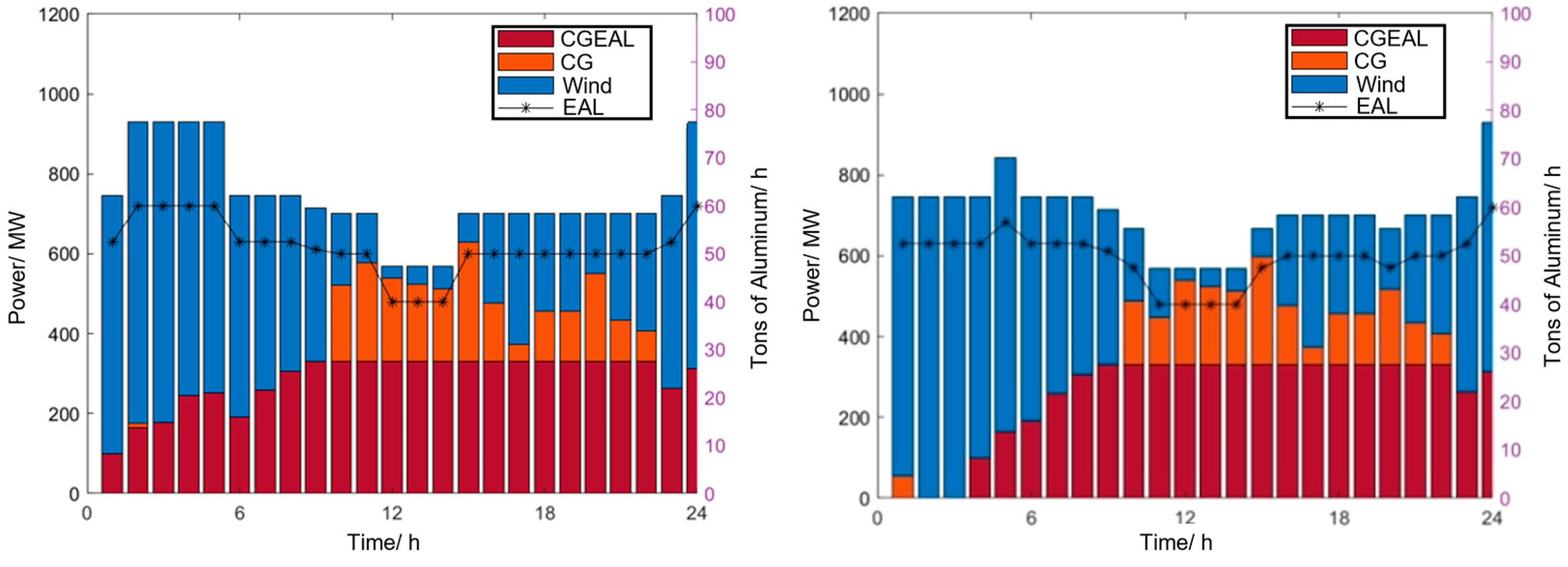

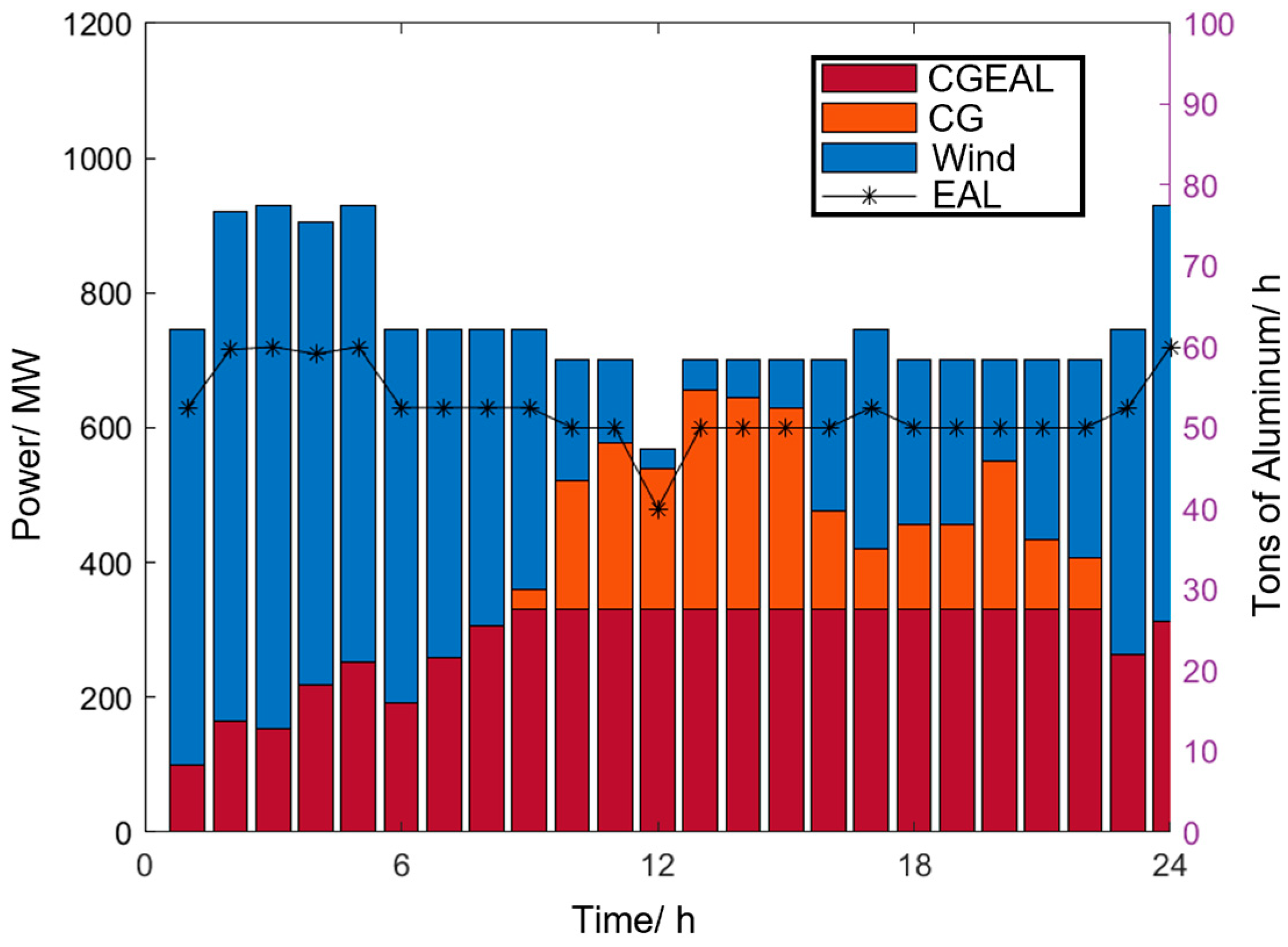

As shown in Figure 8, the left subfigure corresponds to the scheduling results of Scenario 0, while the right subfigure corresponds to those of Scenario 1. In Scenario 0, at the beginning and end of the day, the wind power generation is abundant and the corresponding electricity cost is relatively low. Therefore, the aluminum electrolysis load appropriately increases and operates in an overload mode to achieve more economical production. However, during the 12:00 h to 15:00 h period, the wind power output decreases, resulting in higher electricity costs. Consequently, the aluminum electrolysis plant reduces its load and enters a low-load operation mode to minimize production costs. Although a certain amount of wind curtailment still occurs between 0:00 h and 1:00 h, the aluminum electrolysis load has already been operating continuously in overload mode for four hours (from 1:00 h to 5:00 h). Due to production safety and operational constraints, the overload duration has reached its upper limit and cannot be further extended.

Figure 8.

Comparison of power load and aluminum production scheduling between Scenario 0 and Scenario 1.

Compared with Scenario 0, the proportion of thermal power utilized by the aluminum producer decreases in Scenario 1. Specifically, all thermal power units remain offline during the 0:00–3:00 period, which effectively reduces carbon emissions.

As shown in Table 5, without considering the carbon trading mechanism, the aluminum producer achieves a profit of RMB 5.058 million, with a wind power utilization rate of 99.3%. When carbon emission trading is introduced in Scenario 1, the additional carbon reduction cost decreases the producer′s profit margin. Compared with Scenario 0, the enterprise responds by reducing production capacity to lower its emission-related expenses, resulting in a decreased profit of RMB 4.81 million—a reduction of approximately 4.7%. Meanwhile, the wind power utilization rate slightly declines to 98.8%. Therefore, under the carbon trading mechanism, a higher aluminum output does not necessarily correspond to higher profitability. Since waste heat utilization is not considered in this case, all buildings rely solely on boiler-based heating, producing 1052 t of CO2 emissions that cannot be mitigated. Consequently, the total system emissions remain relatively high.

Table 5.

Optimal dispatch results of CIES according to different models.

(2) Considering the impact of waste heat utilization (comparison between Scenario 2 and Scenario 1).

Building upon Scenario 1, Scenario 2 further incorporates industrial waste heat utilization to enhance the coordination between electrical and thermal energy flows and improve the overall economic performance of the system. This scenario aims to examine the effects of waste heat recovery on the electrical–thermal coupling relationship and system operation characteristics. Figure 9 illustrates the scheduling curves of the aluminum producer and the system power load under Scenario 2. Compared with Scenario 1, where waste heat utilization was not considered, the aluminum production capacity increases significantly in Scenario 2. During 1:00–9:00 and 22:00–24:00, the aluminum plant operates in an overload mode. These periods coincide with wind power generation peaks and low nighttime temperatures, which drive a surge in heating demand. Consequently, the industrial waste heat generated from aluminum electrolysis is utilized for space heating, yielding additional economic benefits. As summarized in Table 5, under the combined influence of carbon trading and waste heat utilization, the aluminum producer increases its waste heat sales, resulting in an annual revenue of RMB 4.98 million and an improved wind power utilization rate of 99.0%.

Figure 9.

Dispatch diagram of power load and electrolytic aluminum production under Scenario 2.

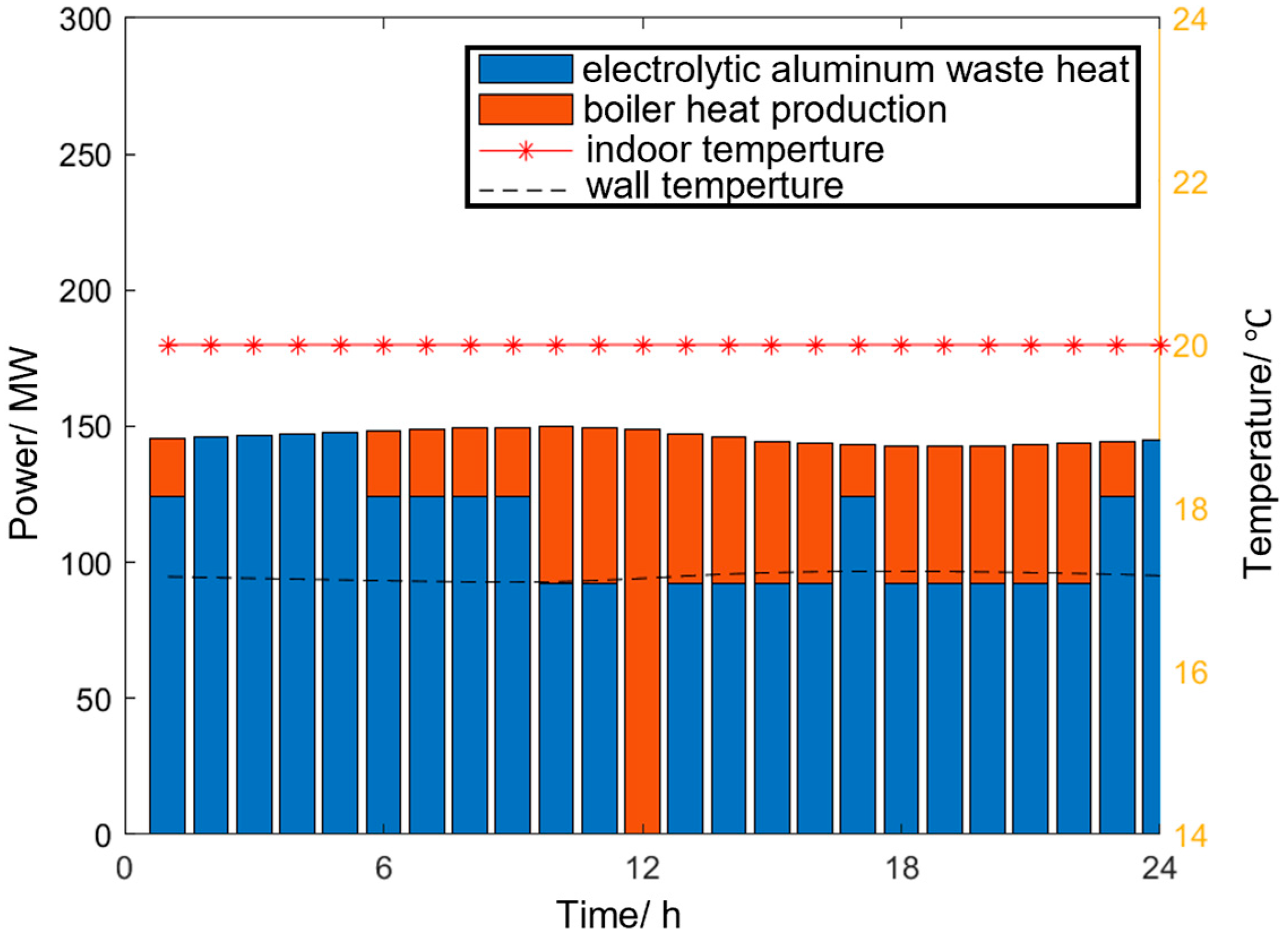

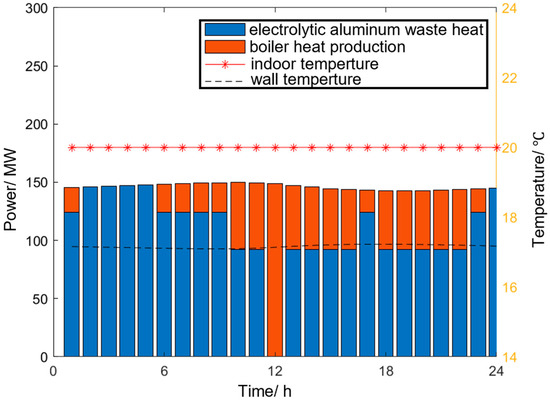

The curve of indoor temperature in buildings under Scenario 2 is shown in Figure 10 above. Since the thermal inertia of the buildings is not considered, the temperature of the buildings will always be maintained at 20 °C, and the waste heat from electrolytic aluminum cannot be fully utilized, resulting in the need for boilers to generate heat for central heating during the day. Compared with Scenario 1, Scenario 2 uses industrial waste heat, which reduces the carbon emissions from building heating from 1052 tons to 266 tons, a total reduction of 786 tons. However, due to the increased production capacity of electrolytic aluminum, the carbon emissions from electrolytic aluminum production have increased by 1044 tons. The total carbon emissions have increased by 258 tons compared with Scenario 1, but they still decreased by 4.8% compared with Scenario 0.

Figure 10.

Curve diagram of indoor temperature in buildings under Scenario 2.

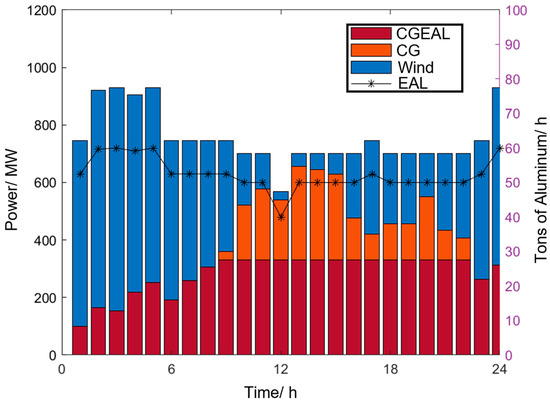

(3) Considering the impact of building thermal inertia (comparison between Scenario 3 and Scenario 2).

The building temperature curve in Scenario 3 is shown in the above figure. After considering the building’s thermal inertia, the building uses the additional waste heat from the overload operation of electrolytic aluminum at night for thermal energy storage. The indoor temperature approaches 22 °C at night. As the load of electrolytic aluminum decreases, the building releases heat during the day, which will significantly reduce the heating power of the boiler. During the 0:00–6:00 period, when the aluminum electrolysis units operate in an overload mode, a large amount of waste heat is generated. The increased heat supply causes the indoor temperature to rise rapidly, reaching nearly 22 °C around 2:00–3:00. From 6:00 to 12:00, the aluminum production load decreases significantly, and the available waste heat declines accordingly. The indoor temperature gradually falls but remains within the comfort range of 18–20 °C. During this period, the required boiler heating power is noticeably reduced, indicating that the previous heat accumulation is sufficient to maintain indoor conditions. Between 12:00 and 18:00, the outdoor temperature rises moderately, keeping indoor temperature stable around 18–19 °C with minimal fluctuation. After 18:00, as the ambient temperature drops again, the aluminum production load increases slightly, providing additional waste heat that compensates for the growing heating demand. In this scenario, since thermal inertia is equivalent to energy storage that can shift part of the heat demand, it is equivalent to increasing the flexibility of demand. Compared with Scenarios 1 and 2, the wind power accommodation rate increases to 99.6%. On the other hand, due to the impact of thermal inertia, carbon emissions will be reduced, some expenditures will be cut, and the profit will rise to CNY 5.02 million. When thermal inertia is considered, the carbon emissions from building heating drop to 44 tons, with a total carbon emission of 10,127 tons. Its carbon emissions are lower than those in Scenario 0 and Scenario 2, but higher than the carbon emission quota in Scenario 2. The carbon emissions from electrolytic aluminum are 10,083 tons, which is the highest of all scenarios. However, its profit is CNY 210,000 higher than that in Scenario 1. It can be seen that Scenario 3 increases income by increasing heat supply, but at the cost of increased carbon emissions. In order to more accurately consider the actual demand for heat supply, it is necessary to take thermal inertia into account.

(4) Impact of different new energy power generation levels.

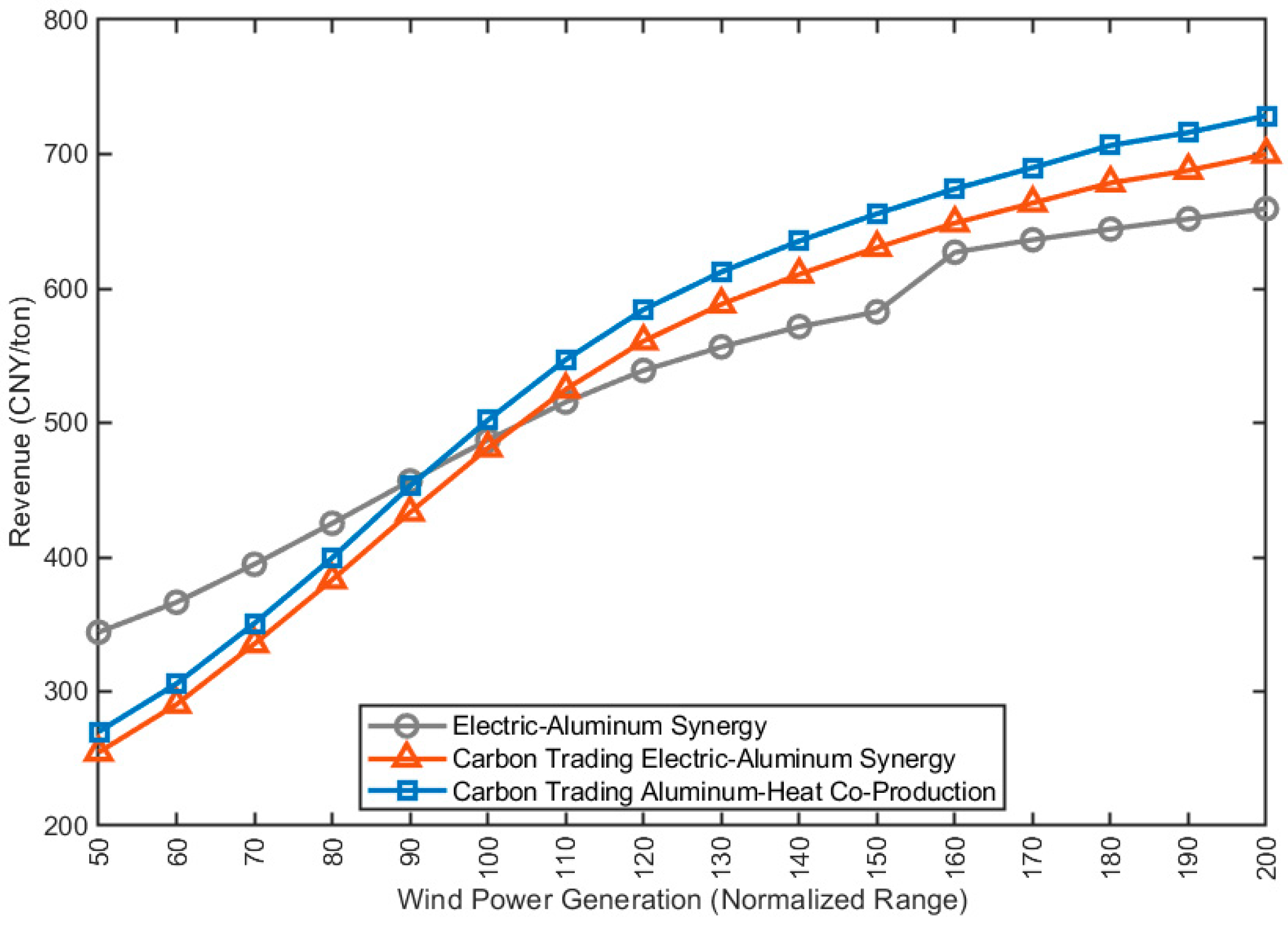

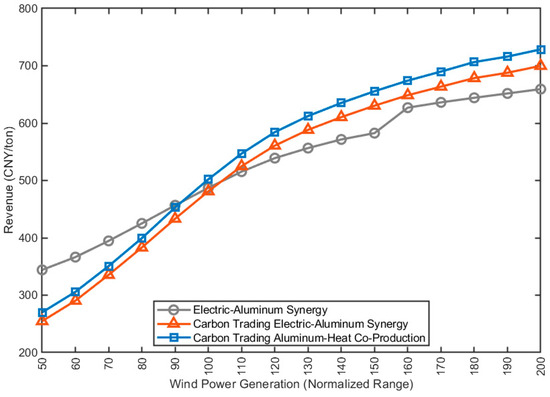

This section mainly examines the impact of different new energy power generation levels on the results of the above scheduling model, focusing on Scenarios 0, 1, and 3, with emphasis on comparing the revenue and carbon emissions of electrolytic aluminum producers under different new energy power generation levels.

Figure 11 shows the revenue of electrolytic aluminum producers under Scenarios 0, 1, and 3 at different wind power generation levels, where 100% represents the rated wind power capacity, and 200% represents the output when the installed capacity is twice the current installed capacity under full load operation. It can be found that the production revenue of aluminum–heat cogeneration under carbon trading in Scenario 3 is always better than that of the electricity–aluminum synergy scenario under carbon trading, which is due to the additional revenue generated by the sale of waste heat.

Figure 11.

Revenue curve of electrolytic aluminum producers under different wind power generation levels.

When the wind power generation level is low, since more thermal power needs to be used for production in this case, the penalties brought by the carbon trading mechanism will lead to the revenue of electrolytic aluminum producers in the latter two scenarios, including carbon trading being lower than that of Scenario 0 (electricity–aluminum synergy without considering the carbon trading mechanism). However, when the wind power generation level exceeds 84%, the impact of carbon emission trading costs in Scenario 0 will decrease, and the revenue of aluminum–heat cogeneration under carbon trading in Scenario 3 will be greater than that of Scenario 0 with only electricity–aluminum synergy; when the wind power generation level exceeds 95%, the impact of carbon emission trading costs in Scenario 0 will continue to decrease, and the revenue of aluminum-electricity synergy under carbon trading in Scenario 2 will be greater than that of Scenario 0 with only electricity–aluminum synergy. It can be seen that the new energy power generation level will indirectly affect the revenue of electrolytic aluminum producers through carbon emission trading.

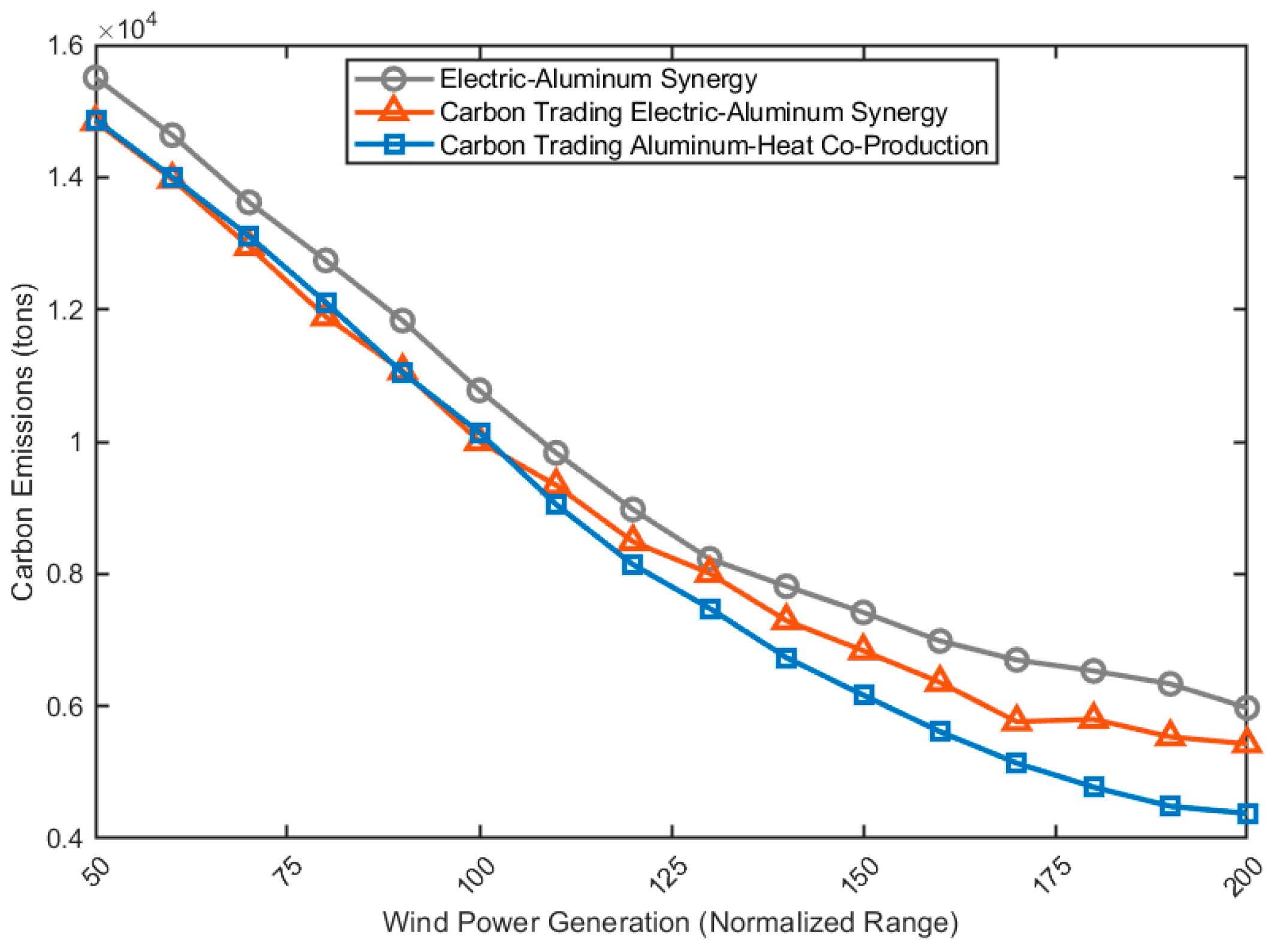

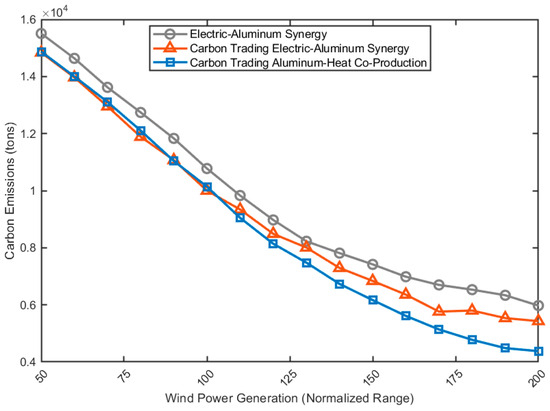

Figure 12 shows the carbon emissions of electrolytic aluminum producers in Scenarios 0, 1, and 3 at different wind power generation levels. After considering the carbon trading mechanism, carbon emissions are significantly reduced. Regardless of the wind power generation level, the total carbon emissions under the scenarios considering the carbon trading mechanism are lower than those under the scenarios not considering the carbon trading mechanism, which indicates the role of the carbon trading mechanism in reducing carbon emissions. We found that due to the increased aluminum production resulting from the aluminum–heat cogeneration under the carbon trading mechanism in Scenario 3, the carbon emissions increase, even exceeding those in the scenario of electricity–aluminum synergy under the carbon trading mechanism in Scenario 1. However, through the simulation in this section, it can be observed that under the condition of high wind power generation level, although the aluminum–heat cogeneration under the carbon trading mechanism in Scenario 3 will increase aluminum production due to the heating demand, the use of wind power will not lead to additional increase in carbon emissions. Therefore, the carbon emissions in this case will be lower than those in the scenario of electricity–aluminum synergy under the carbon trading mechanism in Scenario 1. The proposed aluminum–heat cogeneration model under the carbon trading mechanism not only achieves the highest revenue but also can realize the lowest carbon emission level under the condition of high wind power generation level, which also indicates the impact of wind power generation level on carbon emissions.

Figure 12.

Carbon emission curve of electrolytic aluminum producers under different wind power generation levels.

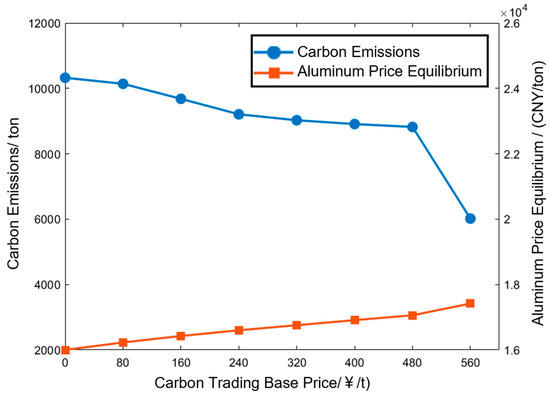

(5) Impact of carbon emission policies

Beyond operational coordination, carbon pricing policies also play a decisive role in shaping enterprise profitability and emission behavior. Therefore, a sensitivity analysis is conducted to investigate how variations in baseline carbon price and free emission allowances influence aluminum production economics. At present, China’s carbon price is still relatively low, at CNY 80 per ton, while the EU’s carbon price has reached about CNY 480 to 560 per ton (EUR 60 to 70 per ton). Considering China’s carbon neutrality goals, carbon policies are likely to become stricter in the future. Therefore, this section analyzes the impact of changes in key parameters related to carbon emission policies on the electrolytic aluminum industry.

Figure 13 shows the changes in the carbon emission quota of electrolytic aluminum producers as the basic price of carbon trading gradually increases from 0 CNY/ton to 560 CNY/ton, as well as the price of finished aluminum when electrolytic aluminum producers maintain a break-even level, that is, the price of finished aluminum required for electrolytic aluminum producers to maintain the profit level at the basic carbon trading price of 0 CNY/ton. It can be observed in the figure that the carbon emission quota of electrolytic aluminum producers has decreased by 41.7%, but in order to maintain the same profit, the aluminum price needs to rise from 16,000 CNY/ton to 17,417 CNY/ton.

Figure 13.

Trend in finished aluminum prices, maintaining profit balance under different basic carbon trading price levels.

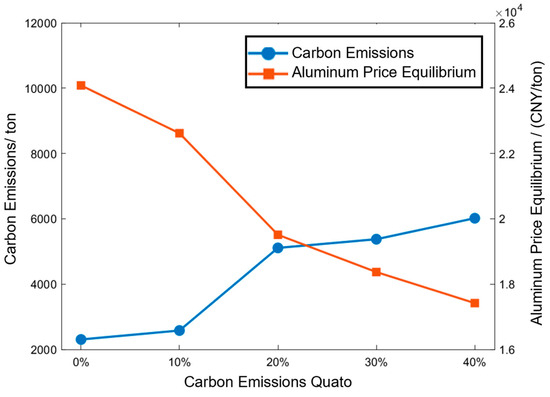

Figure 14 shows the changes in the price of finished aluminum when electrolytic aluminum producers maintain a break-even level after the free carbon emission quota is adjusted. It can be seen from the figure that when the free carbon emission quota decreases from 40% to 0%, the aluminum price required to maintain the same profit increases from 17,400 CNY/ton to 24,000 CNY/ton, which indicates the impact of carbon emission quotas on aluminum prices. These findings highlight that stricter carbon policies significantly increase production costs, thereby reinforcing the necessity of flexible, low-carbon scheduling mechanisms such as the proposed model.

Figure 14.

Curve of finished aluminum prices maintaining profit balance under different levels of free carbon quotas.

5. Methodology

In this study, to achieve low-carbon economic dispatch, we propose an optimized dispatch method that integrates aluminum electrolysis production, wind power consumption, carbon emission trading, and waste heat utilization. First, a load model for aluminum electrolysis that considers production safety constraints is established and optimized using a bi-level framework. The upper-level model focuses on optimizing the grid’s power dispatch to minimize grid power supply costs, while the lower-level model optimizes the aluminum electrolysis production schedule, ensuring production safety and maximizing the aluminum producer’s profit. Additionally, the carbon emission trading mechanism, waste heat recovery, and building thermal inertia are incorporated into the model to further reduce the system’s carbon emissions.

6. Conclusions

This study proposes a coordinated electricity–heat–carbon dispatch model that considers carbon emission constraints and waste heat utilization. Multi-scenario simulations verify its effectiveness in improving both economic performance and emission reductions. The results show that coordinated optimization of the carbon trading mechanism and waste heat utilization enables flexible matching between aluminum electrolysis loads and renewable generation, while building thermal inertia achieves temporal and spatial balancing of heat, significantly improving system efficiency.

The main innovations of this research are as follows:

(1) A bi-level optimization framework for the power–aluminum system is developed, explicitly incorporating production safety constraints and addressing the limitations of existing models.

(2) A coordinated optimization method combining a tiered carbon trading mechanism with waste heat recovery and building thermal inertia is proposed to achieve multi-energy flow coordination among electricity, heat, and carbon.

(3) A multi-physics electro–thermal coupling model of the electrolytic cell is established, capturing the interactions among current density, polarization voltage, and Joule heating, thereby reflecting the real electrochemical energy conversion and providing a solid physical basis for safe and efficient operation.

(4) By integrating a building thermal inertia model, the study links industrial waste heat utilization with demand-side flexibility, extending low-carbon dispatch from production-oriented optimization to source–load collaborative optimization.

The findings of this study provide a theoretical and methodological foundation for the electrolytic aluminum industry to participate in carbon markets and improve waste heat utilization. By coordinating electricity–heat–carbon multi-energy flows, the proposed framework enhances renewable energy integration, reduces carbon emissions, and improves economic performance, offering a practical pathway for the low-carbon transformation of industrial loads in high-renewable systems. Furthermore, the proposed modeling framework and electro–thermal coupling mechanism can be extended to other electrolysis processes, such as copper and zinc production, and to integrated energy management in industrial parks. Future work will incorporate real-time operational data and advanced electrochemical models to improve accuracy and applicability, laying the groundwork for safer, more efficient, and low-carbon optimization in energy-intensive industries.

However, despite the effectiveness of the proposed model in reducing carbon emissions and optimizing scheduling, several limitations remain.

(1) The simplification of the aluminum electrolysis production process may lead to prediction errors under certain specific conditions, particularly concerning the dynamic thermal behavior of electrolytic cells and variations in production processes.

(2) The simulation analysis is mainly based on typical case data, without fully considering different system operating states and economic fluctuations that may occur during long-term operations.

Therefore, future research could improve the dispatch method by incorporating additional industrial constraints, refining the thermodynamic models, and considering a broader range of long-term operational data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Y. and S.L.; methodology, Y.Y. and S.W.; validation, R.Z. and S.W.; formal analysis, Y.Y. and S.L.; investigation, S.L.; resources, Y.Y. and S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L. and S.W.; writing—review and editing, S.W.; visualization, R.Z.; supervision, Y.Y.; project administration, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key Research and Development Program Project of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (2022B01020-1).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Songyuan Li was employed by the company Secondary Maintenance Workshop of State Grid Shenyang Power Supply Company. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Liu, J.; Wang, K.; Su, Z.; Feng, Y.; Wang, C.; Ai, X. Source-load Coordinated Optimal Scheduling in Stochastic Unit Commitment Considered Electrolytic Aluminum Load and Wind Power Uncertainty. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 5th International Electrical and Energy Conference (CIEEC), Nanjing, China, 11 August 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, F.; Ren, K.; Zhang, A.; Chen, S.; Feng, J.; Zhang, K.; Li, D. Review of electrolytic aluminum load participating in demand response to absorb new energy potential and methods. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Big Data, Artificial Intelligence and Internet of Things Engineering (ICBAIE), Nanchang, China, 26–28 March 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, X.; Liao, S.; Xu, J.; Sun, Y. A Source-Load Coordinated Control Strategy in an Industrial Aluminum Production Mircrogrid for Smoothing Wind Power Fluctuations. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/IAS Industrial and Commercial Power System Asia (I&CPS Asia), Chongqing, China, 7–9 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.F.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, X.; Yu, Q.; Jiang, X.; Liao, S. Electrolytic Aluminum Load Participating in Power Grid Frequency Modulation Method Based on Active Adjustable Capacity Coordination. In Proceedings of the 2021 3rd Asia Energy and Electrical Engineering Symposium (AEEES), Chengdu, China, 26–29 March 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Gong, F.; Sun, T.; Yuan, J.; Yang, S.; Liu, Z. Research on the method of electrolytic aluminum load participating in the frequency control of power grid. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Big Data, Artificial Intelligence and Internet of Things Engineering (ICBAIE), Nanchang, China, 26–28 March 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Zeng, K.; Wang, C.; Le, L.; Zhang, M.; Ai, X. Unit commitment considering electrolytic aluminum load for ancillary service. In Proceedings of the 2019 4th International Conference on Intelligent Green Building and Smart Grid (IGBSG), Yichang, China, 6–9 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Fu, B.; Ding, K.; Sun, Y. Day-ahead Economic Dispatch of Power Systems Considering the Demand Response of Electrolytic Aluminum Loads. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Power Science and Technology (ICPST), Dali, China, 9–11 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, W.; Yu, P.; Xu, Z.; Fan, T.; Liu, H.; Yu, M.; Li, J. Day-ahead Intra-day Economic Dispatch Methodology Accounting for the Participation of Electrolytic Aluminum Loads and Energy Storage in Power System Peaking. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Power Science and Technology (ICPST), Dali, China, 9–11 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Du, H.; Hu, J.; Tong, Y. Distributed Optimization Operation Strategy for Green Power Industrial Parks Considering Coordination of Electricity-Certificate-Carbon Mechanisms. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2025, 1–17. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/32.1180.TP.20240820.1451.006 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Jia, X.; Li, D.; Chen, H. Optimal Operation Strategy of Multi-source Combined Cooling, Heating and Power System in Industrial Parks Considering Carbon Trading. J. Chin. Soc. Power Eng. 2023, 43, 1095–1102. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Z.; Yang, C.; Yang, Y. Optimization of Integrated Energy System in Low-carbon Parks Based on Stepwise Carbon Trading. Electr. Eng. 2023, 65, 58–61. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, S.; Zou, Y.; Yao, Y. Optimal Operation of AC/DC Hybrid Distribution Network Based on Network Reconfiguration Under Stepwise Carbon Trading Mechanism. South. Power Syst. Technol. 2025, 19, 96–105. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, N.; Wang, S.; Wu, X.; Yan, H. The low-carbon economic scheduling method for regional integrated energy systems considering the joint integration of electric vehicles and concentrated solar power plants for wind power consumption. Wind. Eng. 2025, 0309524, 241302464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Lu, H.; Chen, M.; Chang, X.; Zheng, C. A low-carbon optimization of integrated energy system dispatch under multi-system coupling of electricity-heat-gas-hydrogen based on stepwise carbon trading. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 97, 362–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, P.; Lin, H.; Tian, Y. Multi-park Integrated Demand Response Strategy Based on Hybrid Game in Electricity-Carbon Joint Market. Proc. CSU-EPSA 2025, 37, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Ma, G.; Yao, Y.; Meng, Y.; Li, W. Multi-energy Optimal Scheduling for Industrial Parks Considering Green Certificate-Carbon Trading Mechanism and Hydrogen-blended Natural Gas. Electr. Power 2025, 58, 154–163. [Google Scholar]

- An, J.; Liu, W.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Kang, J. Optimal Scheduling of Hydrogen-integrated Energy Systems under Green Certificate-Carbon Trading Integration Mechanism. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2024, 45, 104–114. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Mu, Y.; Jia, H. Optimal Scheduling Method for Regional Integrated Energy Systems Considering Off-design Characteristics of Equipment. Power Syst. Technol. 2021, 45, 951–958. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Cao, X.; Chen, J. Optimal Scheduling of Park Integrated Energy Systems with Flexible Thermoelectric Response under Green Certificate-Carbon Trading Mechanism. Electr. Power 2024, 57, 110–120. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, H.; Yu, X.; Zhang, J.; Jin, X.; Deng, Y. Day-ahead Optimal Scheduling Method for Electricity-Water-Heat Integrated Energy Systems Considering Virtual Energy Storage. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2023, 47, 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Han, L.; Deng, X.; Gao, H. Scheduling Optimization of Household Electricity-Heat Integrated Energy Systems Considering Thermal Comfort Improvement. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2025, 46, 165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Song, D. Energy Optimal Scheduling Strategy for Industrial Park Integrated Energy Systems Considering User Dissatisfaction. Master’s Thesis, Yanshan University, Qinhuangdao, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Z.; Song, Z.; Li, L.; Liu, Y. Optimal Scheduling of Industrial Park Integrated Energy Systems with Electric Vehicles. Electr. Power 2024, 57, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Q.; Yang, K.; Song, Z. Scheduling Strategy for Industrial Park Integrated Energy Systems Considering Carbon Trading and Electric Vehicle Charging Load. High Volt. Eng. 2023, 49, 1392–1401. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).