Disassembly and Its Obstacles: Challenges Facing Remanufacturers of Lithium-Ion Traction Batteries

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

1.2. Related Research

| I | Comparison | Does the study compare different design possibilities? |

| II | Degree of Disassembly | How deep is the disassembly of the LIB carried out? |

| III | Application case: Battery | Are EV batteries the application case of the study? |

| IV | Year | Has the study been published recently? |

| V | Disassembly performed | Are purposeful disassembly analyses conducted to support the evaluation? |

- -

- There have been only a few detailed comparative evaluations of different batteries and none for battery components from different brands to assess the extent to which they facilitate disassembly.

- -

- There is a lack of structured analysis at the component level and comparisons of how they enable or hinder disassembly. Existing publications tend to summarize insights from a higher-level perspective, comparing whole battery packs without investigating the depth and sequence of disassembly processes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Circular Economy

2.2. Lithium-Ion Batteries

2.3. End-of-Use/End-of-Life Strategies

2.4. General Dangers to the Remanufacturing of Lithium-Ion Batteries

2.5. Methodology

- 1.

- Disassembly of battery system and documentation thereof

- 2.

- Parts list

- 3.

- Priority matrix

- 4.

- List of disassembly steps and necessary tools

- 5.

- Disassembly graph

3. Results

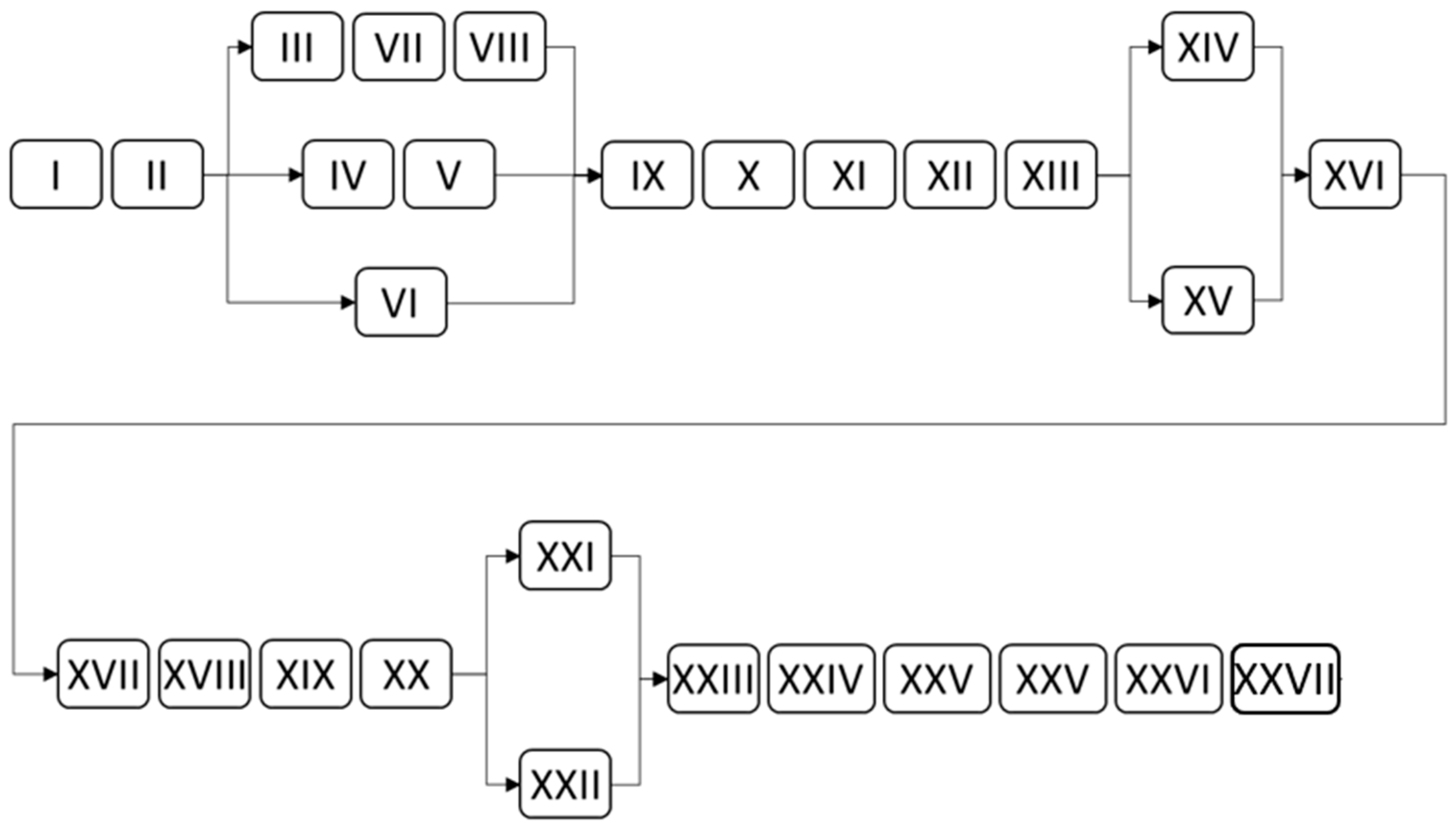

3.1. Disassembly to Module Level of the BMW F48 X1 xDrive25e

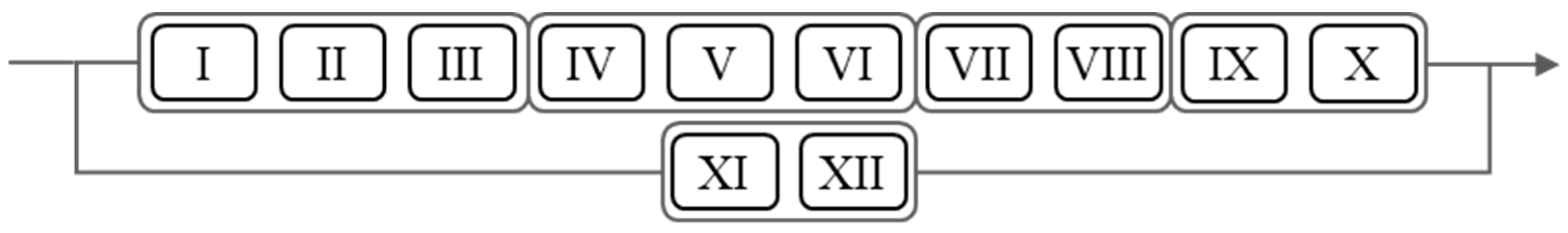

3.2. Disassembly to Module Level of the SMART EQ

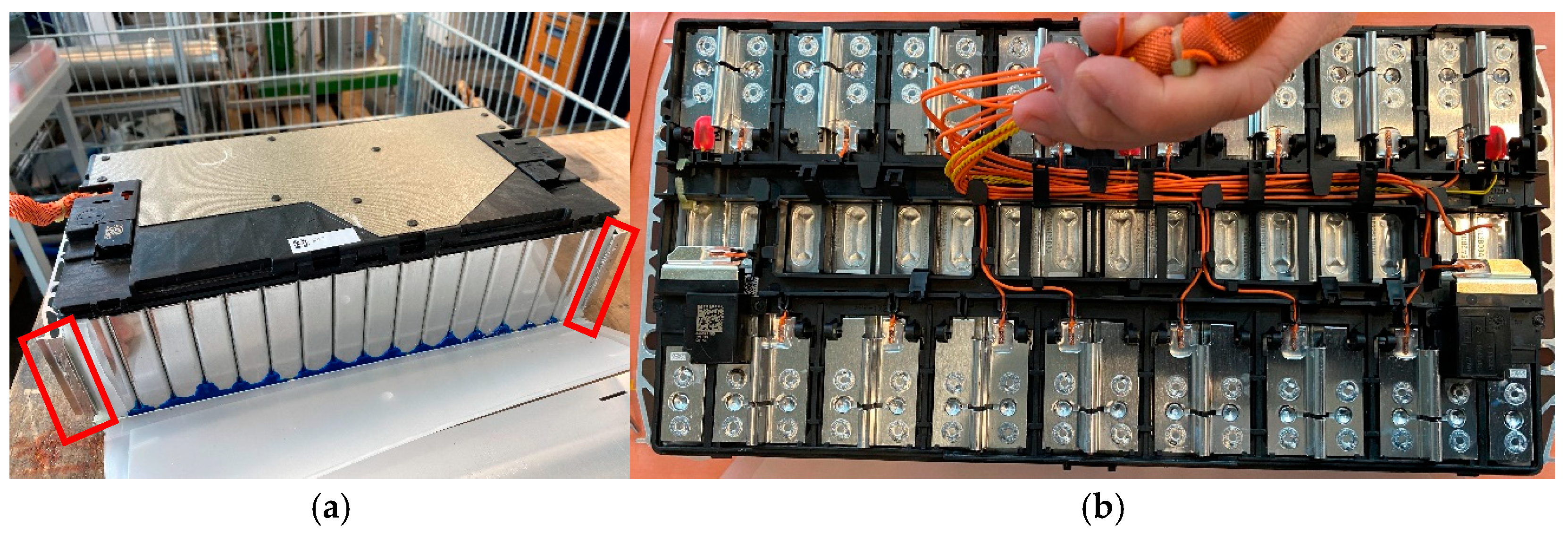

3.3. Disassembly to Cell Level of the BMW F48 X1 xDrive25e

3.4. Disassembly to Cell Level of the SMART EQ

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, T.; Song, W.; Son, D.-Y.; Ono, L.K.; Qi, Y. Lithium-ion batteries: Outlook on present, future, and hybridized technologies. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 2942–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Yang, X.; Zhang, G.; Chen, K.; Wang, S. Experimental investigation on the thermal performance of heat pipe-assisted phase change material based battery thermal management system. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 138, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwicker, M.; Moghadam, M.; Zhang, W.; Nielsen, C.V. Automotive battery pack manufacturing—A review of battery to tab joining. J. Adv. Join. Process. 2020, 1, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.; Beverungen, D.; Winter, M.; Menne, S. Umwidmung und Weiterverwendung von Traktionsbatterien; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; ISBN 978-3-658-21020-5. [Google Scholar]

- Roland Berger. The Lithium Ion (EV) Battery Market and Supply Chain: Market Drivers and Emerging Supply Chain Risks; Roland Berger: Mumbai, India, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, G.; Sommerville, R.; Kendrick, E.; Driscoll, L.; Slater, P.; Stolkin, R.; Walton, A.; Christensen, P.; Heidrich, O.; Lambert, S.; et al. Recycling lithium-ion batteries from electric vehicles. Nature 2019, 575, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gschwendtner, G.; Kopacek, P. A New Method for the Assessment of Products for Automated Disassembling. IFAC Proc. Vol. 1996, 29, 748–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, E.; Hanft, T.A. Quantitative evaluation of product disassembly for recycling. Res. Eng. Des. 1998, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, A.; Mital, A. Evaluation of disassemblability to enable design for disassembly in mass production. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2003, 32, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodhi, R.; Sonnenberg, M.; Das, S. Evaluating the unfastening effort in design for disassembly and serviceability. J. Eng. Des. 2004, 15, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, C.; Raatz, A.; Mennenga, M.; Schmitt, J.; Andrew, S. Assessment of Automation Potentials for the Disassembly of Automotive Lithium Ion Battery Systems. In Leveraging Technology for a Sustainable World, Proceedings of the 19th CIRP Conference on Life Cycle Engineering, University of California at Berkeley, Berkeley, NJ, USA, 23–25 May 2012; Dornfeld, D.A., Ed.; LCE 2012; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; ISBN 364229068X. [Google Scholar]

- Weyrich, M.; Natkunarajah, N. Conception of an automated plant for the disassembly of lithium-ion batteries. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Life Cyle Management (LCM), Gothenburg, Sweden, 25–28 August 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Soh, S.L.; Ong, S.K.; Nee, A. Design for Disassembly for Remanufacturing: Methodology and Technology. Procedia CIRP 2014, 15, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rallo, H.; Benveniste, G.; Gestoso, I.; Amante, B. Economic analysis of the disassembling activities to the reuse of electric vehicles Li-ion batteries. Resources, Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 159, 104785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankemeyer, S.; Wiens, D.; Wiese, T.; Raatz, A.; Kara, S. Investigation of the potential for an automated disassembly process of BEV batteries. Procedia CIRP 2021, 98, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellmuth, J.F.; DiFilippo, N.M.; Jouaneh, M.K. Assessment of the automation potential of electric vehicle battery disassembly. J. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 59, 398–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, S.; Huster, S.; Baazouzi, S.; Glöser-Chahoud, S.; Al Assadi, A.; Schultmann, F. Field Study and Multimethod Analysis of an EV Battery System Disassembly. Energies 2022, 15, 5324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lander, L.; Tagnon, C.; Nguyen-Tien, V.; Kendrick, E.; Elliott, R.J.; Abbott, A.P.; Edge, J.S.; Offer, G.J. Breaking it down: A techno-economic assessment of the impact of battery pack design on disassembly costs. Appl. Energy 2023, 331, 120437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baazouzi, S.; Grimm, J.; Birke, K.P. Multi-Method Model for the Investigation of Disassembly Scenarios for Electric Vehicle Batteries. Batteries 2023, 9, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra-Fontalvo, L.; Polo-Cardozo, J.; Maury-Ramírez, H.; Mesa, J.A. Diagnosing remanufacture potential at product-component level: A disassemblability and integrity approach. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 205, 107529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacy, P.; Rutqvist, J. Waste to Wealth; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-1-349-58040-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards the Circular Economy Vol. 1: An Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Isle of Wight, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Haas, W.; Krausmann, F.; Wiedenhofer, D.; Heinz, M. How Circular is the Global Economy?: An Assessment of Material Flows, Waste Production, and Recycling in the European Union and the World in 2005. J. Ind. Ecol. 2015, 19, 765–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.; Nasr, N. Value-Retention Processes within the Circular Economy. In Remanufacturing in the Circular Economy; Nasr, N., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 1–29. ISBN 9781118414101. [Google Scholar]

- Promi, A.; Meyer, K.; Ghosh, R.; Lin, F. Advancing electric mobility with lithium-ion batteries: A materials and sustainability perspective. MRS Bull. 2024, 49, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korthauer, R. Handbuch Lithium-Ionen-Batterien; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; ISBN 978-3-642-30652-5. [Google Scholar]

- VDI Zentrum Ressourceneffizienz GmbH. Ressourceneffizienz Durch Remanufacturing—Industrielle Aufarbeitung von Altteilen; VDI Zentrum Ressourceneffizienz GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jocher, P.; Steinhardt, M.; Ludwig, S.; Schindler, M.; Martin, J.; Jossen, A. A novel measurement technique for parallel-connected lithium-ion cells with controllable interconnection resistance. J. Power Sources 2021, 503, 230030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Hynan, P.; von Jouanne, A.; Yokochi, A. Current Li-Ion Battery Technologies in Electric Vehicles and Opportunities for Advancements. Energies 2019, 12, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potting, J.; Hekkert, M.P.; Worrell, E.; Hanemaaijer, A. Circular Economy: Measuring innovation in the product chain. Planbur. Voor De Leefomgeving 2017. [Google Scholar]

- British Standards Institution. Design for Manufacture, Assembly, Disassembly and End-Of-Life Processing (MADE) Part 2 Terms and Definitions British Standards Institution; British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 9780580632853. [Google Scholar]

- Kampker, A. Elektromobilproduktion; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; ISBN 978-3-642-42021-4. [Google Scholar]

- Baltac, S.; Slater, S. Batteries on Wheels: The Role of Battery Electric Cars in the EU Power System and Beyond. Available online: https://www.transportenvironment.org/uploads/files/2019_06_Element_Energy_Batteries_on_wheels_Public_report.pdf (accessed on 19. November 2024).

- Beverungen, D. (Ed.) Dienstleistungsinnovationen für Elektromobilität: Märkte, Geschäftsmodelle, Kooperationen; [DELFIN—Dienstleistungen für Elekromobilität—Förderung von Innovation und Nutzerorientierung]; Gefördert vom Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung; [Laufzeit: 1 May 2013–31 October 2015]; Fraunhofer-Verl.: Stuttgart, Germany, 2015; ISBN 3839608430. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, W.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, H. A Method for Pre-determining the Optimal Remanufacturing Point of Lithium ion Batteries. Procedia CIRP 2014, 15, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charter, M.; Gray, C. Remanufacturing and product design. Int. J. Prod. Dev. 2008, 6, 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhilper, R. Produktrecycling: Vielfachnutzen Durch Mehrfachnutzung; Fraunhofer-IRB-Verl.: Stuttgart, Germany, 1999; ISBN 3816753078. [Google Scholar]

- Standridge, C.R.; Corneal, L. Remanufacturing, Repurposing, and Recycling of Post-Vehicle-Application Lithium-Ion Batteries; Tech Report United States; Mineta National Transit research Consortium: San Jose, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kampker, A.; Vallée, D.; Schnettler, A. Elektromobilität; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; ISBN 978-3-662-53136-5. [Google Scholar]

- Colledani, M.; Battaïa, O. A decision support system to manage the quality of End-of-Life products in disassembly systems. CIRP Ann. 2016, 65, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanisch, C.; Haselrieder, W.; Kwade, A. Recycling von Lithium-Ionen-Batterien—Das Projekt LithoRec. Recycl. Und Rohst. 2012, 5, 691–698. [Google Scholar]

- Geisbauer, C.; Wöhrl, K.; Lott, S.; Nebl, C.; Schweiger, H.-G.; Goertz, R.; Kubjatko, T. Scenarios Involving Accident-Damaged Electric Vehicles. Transp. Res. Procedia 2021, 55, 1484–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akademie des Deutschen Kraftfahrzeuggewerbes GmbH. Handbuch zur Schulung von Fachkundigen für Arbeiten an HV-eigensicheren Systemen: Hybridfahrzeuge, Elektrofahrzeuge, Brennstoffzellenfahrzeuge; Vogel Buchverlag: Würzburg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson, F.; Bertilsson, S.; Furlani, M.; Albinsson, I.; Mellander, B.-E. Gas explosions and thermal runaways during external heating abuse of commercial lithium-ion graphite-LiCoO2 cells at different levels of ageing. J. Power Sources 2018, 373, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.; Hilton, M.; Crossette, S.; Horton, I.; Hickman, M.; Mason, R.; Brown, A. Cutting Lithium-Ion Battery Fires in the Waste Industry; Eunomia Research & Consulting: Bristol, UK, 2021; Available online: https://qna.files.parliament.uk/qna-attachments/1625088/original/Waste-Fires-Caused-by-Li-ion-Batteries_FINAL-amended-w0l4kc.pdf (accessed on 19. November 2024).

- Gassmann, M. Akku-Packs Können Wie Eine BOMBE Hochgehen. Available online: https://www.welt.de/wirtschaft/article128500300/Akku-Packs-koennen-wie-eine-Bombe-hochgehen.html (accessed on 19. November 2024).

- Wegener, K.; Andrew, S.; Raatz, A.; Dröder, K.; Herrmann, C. Disassembly of Electric Vehicle Batteries Using the Example of the Audi Q5 Hybrid System. Procedia CIRP 2014, 23, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author (s) (Year) | I. Comparison | II. Degree of Disassembly | III. Application Case: Batteries | IV. Year | V. Method: Disassembly |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gschwendtner/Kopacek (1996) [7] | ⭘ | ◑ | ⭘ | ⭘ | ⭘ |

| Kroll/Carver (1999) [8] | ⭘ | ⬤ | ⭘ | ⭘ | ⭘ |

| Desai/Mital (2003) [9] | ⭘ | ⬤ | ⭘ | ⭘ | ⭘ |

| Sodhi et al. (2004) [10] | ⭘ | ⬤ | ⭘ | ⭘ | ⬤ |

| Herrmann et al. (2012) [11] | ⭘ | ⭘ | ⬤ | ◑ | ⬤ |

| Weyrich (2013) [12] | ⭘ | ⭘ | ⬤ | ◑ | ⭘ |

| Soh et al. (2014) [13] | ⭘ | ◑ | ⭘ | ◕ | ⭘ |

| Rallo et al. (2020) [14] | ⭘ | ◕ | ⬤ | ◕ | ⬤ |

| Blankemeyer et al. (2021) [15] | ⬤ | ◔ | ⬤ | ◕ | ◑ |

| Hellmuth et al. (2021) [16] | ◑ | ⭘ | ⬤ | ◕ | ⬤ |

| Rosenberg et al. (2022) [17] | ⭘ | ◑ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ |

| Lander et al. (2023) [18] | ⬤ | ◑ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ◔ |

| Baazouzi et al. (2023) [19] | ⭘ | ◔ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ |

| Sierra-Fontalvo (2024) [20] | ◑ | ⬤ | ⭘ | ⬤ | ⬤ |

| This study | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ |

| Strategy | Description |

|---|---|

| R3 Reuse | Reuse by another consumer of discarded product that is still in good condition and fulfills its original function |

| R4 Repair | Repair and maintenance of defective product so it can be used with its original function |

| R5 Refurbish/Recondition | Return a used product to a satisfactory working condition by rebuilding or repairing major components that are close to failure, even where there are no reported or apparent faults in those components |

| R6 Remanufacture | Return a used product to at least its original performance with a warranty that is equivalent to or better than that of the newly manufactured product |

| R7 Repurpose | Use discarded product or its parts in a new product with a different function |

| R8 Recycle | Process materials to obtain the same (high grade) or lower (low grade) quality |

| Number | Part |

|---|---|

| 1–5 | Cell Module 1–5 |

| 6 | Safety Box |

| 7 | Battery Management Unit |

| 8 | System Cover |

| 9 | System Base |

| 10 | Bottom Shelf |

| 11 | Top Shelf |

| 12 | Top Cooler |

| 13 | Bottom Cooler |

| 14 | HV cable plus/minus |

| 15 | HV connector |

| 16 | NV wiring harness |

| Priority Matrix | Successor | Total | Rank | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 6 | 7 | 11 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 12 | 10 | 4 | 5 | 16 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 9 | |||||

| Predecessor | 8 | System Cover | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 15 | 1 | |

| 6 | Safety Box | −1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 2 | ||

| 7 | BMS | −1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 2 | ||

| 11 | Top Shelf | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 11 | 4 | ||

| 1 | Cell Module 1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 5 | ||

| 2 | Cell Module 2 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 5 | ||

| 3 | Cell Module 3 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 5 | ||

| 12 | Top Cooler | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 8 | ||

| 10 | Bottom Shelf | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 10 | ||

| 4 | Cell Module 4 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 11 | ||

| 5 | Cell Module 5 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 11 | ||

| 16 | LV Wiring Harness | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 8 | ||

| 13 | Bottom Cooler | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 13 | ||

| 14 | HV cable | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 14 | ||

| 15 | HC Connector | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 15 | ||

| 9 | System Base | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 16 | ||

| Disassembly Step Number | Disassembly Step | Necessary Tool |

|---|---|---|

| I | Unscrew and remove cover (8) | Ratchet, hand |

| II | Remove seal (8) | Hand |

| III | Detach HV cable (1) | Hand |

| IV | Disconnect HV plug (6) | Hand |

| V | Unscrew and remove safety box (6) | Ratchet, hand |

| VI | Unscrew, unplug, and remove battery management unit (7) | Ratchet, hand |

| VII | Unplug cell supervisory electronics (1) | Hand |

| VIII | Unscrew and remove cell module (1) | Ratchet, hand |

| IX | Unplug temperature sensor wire (11) | Hand |

| X | Cut cable tie and remove clips (11) | Side cutter, hand |

| XI | Unscrew and remove top shelf (11) | Ratchet, hand |

| XII | Detach HV cables (2,3) | Hand |

| XIII | Unplug cell supervisory electronics (2,3) | Hand |

| XIV | Unscrew and remove cell module (2) | Ratchet, hand |

| XV | Unscrew and remove cell module (3) | Ratchet, hand |

| XVI | Unscrew and remove top cooler (12) | Ratchet, hand |

| XVII | Unscrew and remove bottom shelf (10) | Ratchet, hand |

| XVIII | Detach HV cables (4,5) | Hand |

| XIX | Remove cable duct with HV cables (4,5) | Hand |

| XX | Unplug cell supervisory electronics (4,5) | Hand |

| XXI | Unscrew and remove cell module (4) | Ratchet, hand |

| XXII | Unscrew and remove cell module (5) | Ratchet, hand |

| XXIII | Remove clips and disconnect HV-interlock (16) | Hand |

| XXIV | Unscrew and disconnect NV connector and remove NV wiring harness (16) | Ratchet, hand |

| XXV | Unscrew and remove bottom cooler (13) | Ratchet, spanner |

| XXVI | Remove clips, disconnect HV connector, and remove HV cable (14) | Pliers, hand |

| XXVII | Unscrew and remove HV connector (15) | Ratchet |

| Number | Part |

|---|---|

| 1 | System Cover |

| 2 | HV Connector |

| 3 | LV Connector |

| 4 | Cell Module 1 |

| 5 | Cell Module 2 |

| 6 | Cell Module 3 |

| 7 | LV Wiring Harness |

| 8 | Cooler 1 |

| 9 | Cooler 2 |

| 10 | System Base |

| 11 | HV Power Rail |

| 12 | Drying Cartridge |

| 13 | Gas Venting |

| Priority Matrix Disassembly | Successor | Total | Rank | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |||||

| Predecessor | 1 | System Cover | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 1 | |

| 2 | HV Connector | −1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 2 | ||

| 3 | LV Connector | −1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 2 | ||

| 4 | Cell Module 1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | ||

| 5 | Cell Module 2 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | ||

| 6 | Cell Module 3 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | ||

| 7 | LV Wiring Harness | −1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 4 | ||

| 8 | Cooler 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | ||

| 9 | Cooler 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | ||

| 10 | System Base | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 10 | ||

| Disassembly Step Number | Disassembly Step | Necessary Tool |

|---|---|---|

| I | Unscrew cover (1) and base (10) | Ratchet |

| II | Unscrew high- (2) and low- (3) voltage connectors | Ratchet |

| III | Remove the cover (1) | Hand |

| IV | Loosen and disconnect HV power rail (11) | Ratchet |

| V | Unplug high- (2) and low- (3) voltage connectors | Hand |

| VI | Remove high- (2) and low- (3) voltage connectors | Hand |

| VII | Unplug low (3) voltage wiring harness | Hand |

| VIII | Remove low (3) voltage wiring harness | Hand |

| IX | Unscrew cell module (5,6,7) | Ratchet |

| X | Remove cell module (5,6,7) | Hand |

| XI | Unscrew cooler (8,9) | Ratchet |

| XII | Remove cooler (8,9) | Hand |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ohnemüller, G.; Beller, M.; Rosemann, B.; Döpper, F. Disassembly and Its Obstacles: Challenges Facing Remanufacturers of Lithium-Ion Traction Batteries. Processes 2025, 13, 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13010123

Ohnemüller G, Beller M, Rosemann B, Döpper F. Disassembly and Its Obstacles: Challenges Facing Remanufacturers of Lithium-Ion Traction Batteries. Processes. 2025; 13(1):123. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13010123

Chicago/Turabian StyleOhnemüller, Gregor, Marie Beller, Bernd Rosemann, and Frank Döpper. 2025. "Disassembly and Its Obstacles: Challenges Facing Remanufacturers of Lithium-Ion Traction Batteries" Processes 13, no. 1: 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13010123

APA StyleOhnemüller, G., Beller, M., Rosemann, B., & Döpper, F. (2025). Disassembly and Its Obstacles: Challenges Facing Remanufacturers of Lithium-Ion Traction Batteries. Processes, 13(1), 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13010123