Abstract

A mathematical model of micropolar squeezing flow of nanofluids between parallel planes is taken into consideration under the influence of the effective Prandtl number using ethyl glycol and water as base fluids along with nanoparticles of gamma alumina . The governing nonlinear PDEs are changed into a system of ODEs via suitable transformations. The RKF (Range–Kutta–Fehlberg) technique is used to solve the system of nonlinear equations deriving from the governing equation. The velocity, temperature, and concentration profiles are depicted graphically for emerging parameters such as Hartmann number micronation parameter squeeze number , Brownian motion parameter , and thermophoresis parameter . However, physical parameters such as skin friction coefficient, Nusselt number, and Sherwood number are portrayed in tabulated form. The inclusion of the effective Prandtl number model indicated that the effect of the micropolar parameter on angular velocity h(ξ) in both suction and injection cases is opposite for both nanofluids. It is observed that the increase in angular velocity is rapid for throughout the study.

1. Introduction

Recent technological advancements have renewed interest in non-Newtonian fluid flows. These fluids play an important role in many situations. Engineers, mathematicians, modelers, physicists, and computer scientists have been interested in the flows of these fluids in recent years due to their applications in industry and technology. In addition to the Navier–Stokes equations, the governing equations of non-Newtonian fluids are of a higher order and highly nonlinear, which are presented in [1,2,3]. Non-Newtonian fluid flows have been the subject of even more research. Micropolar fluids differ from non-Newtonian fluids in that they exhibit microscopic characteristics such as micro-rotational and rotational inertia. The theory of micropolar fluids was initially suggested by [4]. Micropolar fluids are essential for the movement of colloidal suspensions, liquid crystals, additive-containing fluids, suspension solutions, animal blood, and other fluids. Ariman T [5] discusses the application of micro-continuum fluid mechanics. Ezzat [6] and Helmy [7] presented some uses of the magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) boundary layer flow. Raees [8] and Jena [9] incorporate the applications of the Free Convection Flow of a Micropolar Fluid from a Vertical Flat Plate. The application of stagnation point flow of micropolar fluid flow was investigated by Guram [10] and Nazar [11]. Similarly, Ahmadi [12] and Takhar [13] have investigated the flow of micropolar fluids in various configurations to accomplish such applications. Recently, Ramesh et al. [14] have investigated the time-dependent Casson-micropolar nanofluid squeezing flow with suction/blowing and slip effects. By contrast, Kumbinarasaiah et al. [15] used the Hermite wavelet approach to solve coupled nonlinear differential equations occurring in a rotating micropolar nanofluid flow system. Later on, Shamshuddin et al. [16] demonstrated the influences of different aspects of micropolar nanofluids such as a chemically reactive Casson fluid treated to a rotatory system with electrical and Hall currents between parallel plates. Hussain et al. [17] investigated multiple slip effects in a biothermal MHD convection flow of a micropolar nanofluid between two parallel discs, while Sastry et al. [18] incorporated the application to cardiovascular problems of unsteady 3D micropolar nanofluid flow through a squeezing channel.

Squeezing flows are also common in hydrodynamic machines, polymer processing, compression and injection molding models, lubrication processes, and polymer processing procedures, among other things. The time-dependent squeezed flow is frequently addressed in industrial situations to characterize fluid movement along a prescribed length of contracting area. A preliminary sluggish liquid may be placed between a pair of rectangular parallel discs and planes to show the associated mathematical models upon such planes of coordinates, and this flow can be set up. Usha [19] found an exact solution to a similar problem in a couple of elliptic plates using a multifold time-dependent series. The time-dependent viscous squeezing flow between two parallel plates with a constant temperature was investigated by [20]. Grimm [21] looked at the squeezing flows of Newtonian liquid plates.

Furthermore, in the last two decades engineers have turned their attention to a new form of fluid known as “nanofluid.” Nanofluids are fluids that include nanometer-sized particles in a suspension, also known as nanoparticles. Nanomaterials are important because of their high thermal and mechanical properties. The properties of the nanoliquids created by each nanomaterial are considerably altered by these materials. Among nanomaterials, there is a substance known as aluminum alloys, in which aluminum plays a significant role. Aluminum alloys are divided into two categories: heat-treatable and non-heat-treatable. Some of the most commonly used nanofluids are water , ethyl glycol and oil. Choi [22] was the first to demonstrate that putting these nanoparticles into a base fluid enhanced its thermal conductivity. Buongiorno [23] proposed a mathematical model to emphasize the significant impacts of the Brownian motion and thermophoretic diffusion of nanoparticles.

Soundings into the flow dynamics of nanofluids have revealed their importance in cooling operations by Popa [24], T.M.O. Sow [25], and H. Beiki [26]. To cool an engine, Moghaieb [27] employed an nanofluid. Ganesh [28] and Rashidi [29] demonstrated that similarity solutions improved the flow properties of nanofluids over stretchy surfaces. They used experimentally-based thermophysical properties in their studies to ensure the physical pertinence of gamma alumina nanoparticles.

A careful review of the literature finds that no one has studied the effects of an experimentally based Prandtl number model on the squeezing flow of micropolar fluids flow of (gamma alumina and water) and (gamma alumina and ethyl glycol) across parallel plates, to the author’s knowledge. In light of this, we investigate the impact of an effective Prandtl number model on the squeezing flow of nanoparticle micropolar fluid between parallel planes. As a result, the squeezing flow of (gamma alumina and water) and (gamma alumina and ethyl glycol) between two parallel planes is explored in this study under the impact of the effective Prandtl number. The analytical solutions generated are being utilized to investigate the influence of various factors on the squeezing flow between two parallel planes.

2. Mathematical Analysis

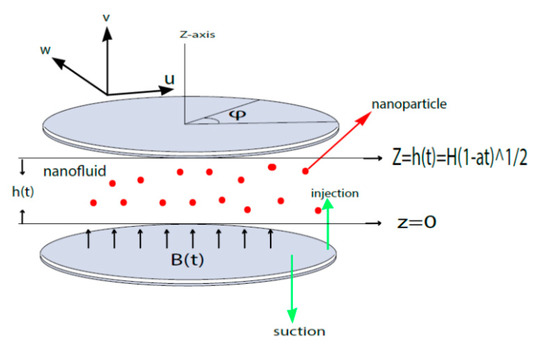

Consider the two-dimensional axisymmetric flow of incompressible nanofluid between two parallel planes with vertical magnetic fields proportional to . As for low Reynold numbers, the magnetic field is neglected. It contains nanoparticles such as aluminum oxide and gamma aluminium oxide in base fluids such as water and ethylene glycol . The lower plane is at Z = 0, and the upper plane is separated by As shown in the Figure 1, the upper plane moves toward or away from the lower plane at a velocity of .

Figure 1.

Geometry of the problem.

The following are the governing equations for two-dimensional axisymmetric and unsteady fluid flow, as well as heat transfer in viscous fluids:

Subject to auxiliary conditions [30]

The velocity components in the and directions are represented by and , respectively, while the azimuthal component of micro-rotation is represented by . The concentration of nanoparticles in the fluid is denoted by . and represent nanoparticle concentrations, while and represent constant temperature at the lower and upper planes, respectively. is the effective density, is efficient thermal diffusion, is dynamic viscosity of nanofluids, is vortex viscosity, is kinematic viscosity, indicates pressure, and represents specific heat capacitance. Furthermore, is the mass diffusion coefficient, is the Brownian motion coefficient, and is the thermophoretic diffusion coefficient. is temperature, and is the mean fluid temperature. Furthermore, represents a non-dimensional parameter, which is the ratio of the nanoparticle’s effective heat capacity to the fluid’s heat capacity. is assumed to be constant and represents wall injection and suction velocity. is assumed to be constant and , where represents the refrence length. is the effective electrical conductivity of nano liquids. Moreover, the effective density and dynamic viscosity of the nanofluid [24] are as follows:

Nanofluid’s effective Prandtl number [30,31] is demarcated as

Nanofluid’s effective electrical conductivity is given as

The thermophysical characreristics of nanoparticles are painted in Table 1 [31].

Table 1.

Thermal and physical properties of base fluids and nanoparticles.

Under the following similarity transformation [32] to reduce the constitutive Equations (2)–(6) as:

2.1. Model of

Using similarity transformations (15), we get transform equations for

where,

2.2. Model of

Using similarity transformations (15), we get transform equations for

where,

The non-dimensionalized boundary conditions are

The following non-dimensionized parameters are used in the flow model.

where is Micropolar parameter, is Magnetic parameter (Hartmann number), is Squeezed Reynolds number, is Lewis number, is Thermophoresis parameter, is Brownian motion parameter is Prandtl number, and is suction or injuction parameter.

The skin friction coefficient , local nusselt number , and sherwood number at both upper and lower disks are demarcated [30] as

where,

The transformed form of , for the model is

and for the model is

where is local squeezed Reynolds number.

3. Method of Solutions

The numerical procedure known as the Runge–Kutta–Fehlberg method (or RKF method) is used to solve mathematical equations with the computational error being demarcated as . In the discipline of numerical analysis, the RKF method is a method for solving numerical solutions to ODEs.

- The coupled system of equations is first converted into a collection of initial value problems, which are then solved by the shooting method.

- Secondly, the Runge–Kutta–Fehlberg Method, is employed to collect the outcomes. All of the imitations and graphically recognized analyses are brought out using the software Mathematica.

With the aid of Equation (15), we engrave Equations (16)–(19) as follows:

Let us take

By using the above substitution, we get

The relevant boundary conditions are

This is the approach that was developed for . Similarly, we obtain this approach for

4. Graphical Results

We analyze how changing values of emerging parameters affect flow pattern behavior and variations in radial velocity rotational velocity, temperature field and concentration profile It should be noted that indicates suction flow, whereas indicates injection or blowing.

4.1. Radial Velocity

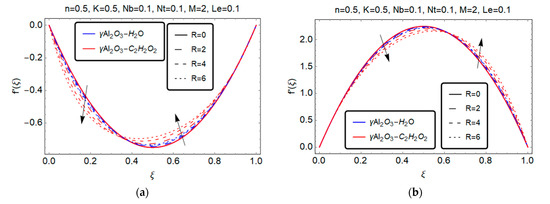

The effects of many evolving parameters on radial velocity, such as the micropolar parameter , squeezed Reynolds number , and Hartmann number , are depicted in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4.

Figure 2.

Effect of squeezed number on . (a) S > 0; (b) S < 0.

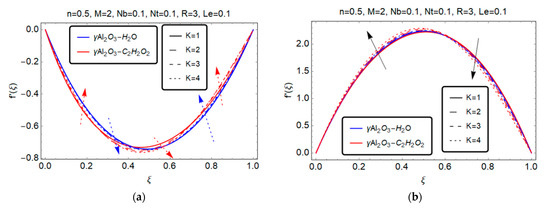

Figure 3.

Effect of micropolar parameter on . (a) S > 0; (b) S < 0.

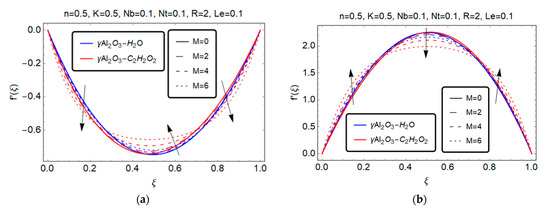

Figure 4.

Effect of Hartmann number M on . (a) S > 0; (b) S < 0.

For (suction), the magnitude of radial velocity elevates rapidly as the squeeze number increases in the range of . Furthermore, the flow behavior of nanofluid water and ethyl glycol fluctuates in the 0.4 < ξ ≤ 1 region, showing that increases as Reynold number goes up, as shown in Figure 2a. For , radial velocity decelerates upon a rising value of in the range , then starts accelerating as illustrated in Figure 2b. Physically, when the surfaces move closer together, the fluid is forced out of the channel, slowing the velocity in the boundary area. Contrarily, when the surfaces move faster, the fluid is squeezed into the channel, increasing the velocity of the boundary area.

Figure 3 depicts the effect of the micropolar parameter on the radial velocity For (suction), the radial velocity decreases with the increase in the micropolar parameter , but the variation in the flow behavior of the nanofluids, water, and ethyl glycol with the suspended gamma alumina particles occurs around 0.7, after which increases with the increase in the micropolar parameter , as shown in Figure 3a. In the case of injection, an opposite behavior is observed.

Figure 4 depicts the behavior of Hartmann number on the radial velocity. In the suction case, radial velocity decreases at the wall region for both models and , as Hartmann number increases. Physically, the Lorentz force, which slows fluid motion at the boundary layer when the plates come together, causes the velocity distribution to drop as the magnetic parameter increases. Furthermore, when and two plates are very close to each other, the scenario causes an unfavorable pressure gradient, which is exacerbated by the retarding Lorentz force. When such forces act over a long period of time, a point of separation may arise, resulting in backflow. Furthermore, as the plates separate (i.e., S > 0), the magnetic parameter rises and the velocity distribution falls. S > 0 has a somewhat different cause than . When two plates separate, a vacant space is created, and the fluid in that region moves at a high velocity, ensuring that mass flow conservation is maintained. As a result, a faster flow is observed.

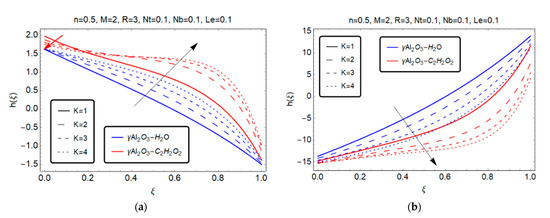

4.2. Angular Velocity

Figure 5 and Figure 6 are painted to investigate the influence of physical parameters on angular velocity for both models and

Figure 5.

Effect of micropolar parameter on . (a) S > 0; (b) S < 0.

Figure 6.

Effect of squeezed Reynold number on . (a) S > 0; (b) S < 0.

Figure 5a shows that when the micropolar parameter is increased in the suction condition, the angular velocity initially falls at the area of for the model, then increases with increasing values of . For the model , the angular velocity initially increases with the increment of values of for . For , the angular velocities of both models decrease as the micropolar prameter increases, as shown in Figure 5b. But the behavior of the graph 5b shows that the angular velocity is increased in the region of , more rapidly for the model .

Figure 6a pointed out that, for the angular velocities of both models and increased as the squeeze number increased. By contrast, in the case of injection, the opposite phenomenon occurs at the region with rising values of , after which the angular velocities increase with increasing squeezed number .

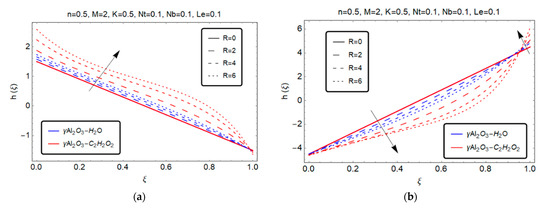

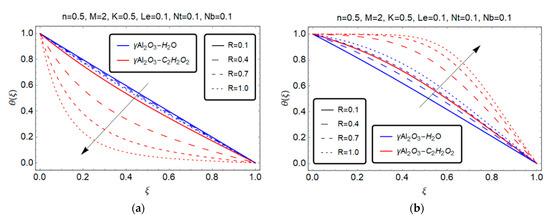

4.3. Temperature Field

Figure 7 and Figure 8 depict the effect of important flow factors on the temperature distribution, including the thermophoresis parameter and the squeezed number R.

Figure 7.

Effect of thermophoresis parameter on . (a) S > 0; (b) S < 0.

Figure 8.

Effect of squeezed Reynold number R on . (a) S > 0; (b) S < 0.

For , the temperature distribution rises with increasing values of the thermophoresis parameter for both models and as shown in Figure 7a. By contrast, in the case of injection, the temperature distribution slowly increases with increasing values of only for the model, but for the model, the temperature distribution remains unchanged until it approaches the neighborhood of 0.5, after which it slowly decreases until it approaches 1.

Figure 8a depicts the temperature distribution of the model gradually increasing with rising values , and temperature distribution of the model rapidly increasing in comparison to the for . By contrast, in the case of blowing the opposite effect is observed for both models. Physically, the temperature in the flow increases as increases the kinetic energy of fluid particles due to the bigger channel volume. The lower channel volume, on the other hand, reduces the kinetic energy of fluid particles, slowing down the temperature field.

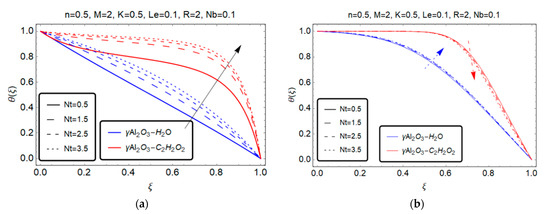

4.4. Concentration Profile

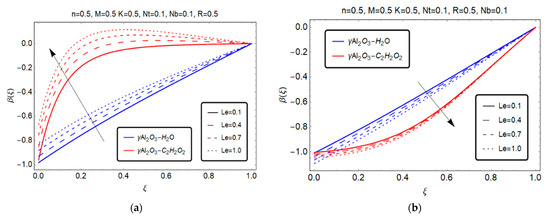

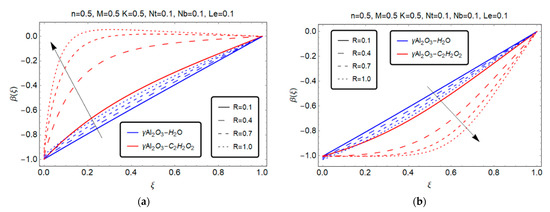

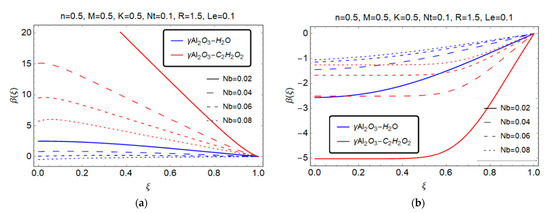

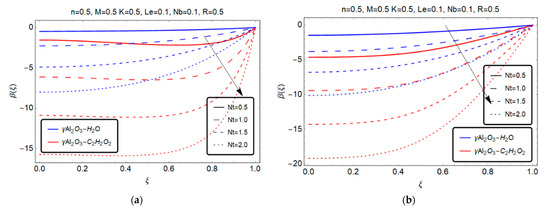

The influence of several physical parameters, , on the concentration profile is incorporated in Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12.

Figure 9.

Effect of Lewis number on . (a) S > 0; (b) S < 0.

Figure 10.

Effect of Reynold number R on on . (a) S > 0; (b) S < 0.

Figure 11.

Effect of Brownian motion on . (a) S > 0; (b) S < 0.

Figure 12.

Effect of Thermophoresis parameter on . (a) S > 0; (b) S < 0.

Figure 9a and Figure 10a indicate that for both models and in suction (), the variation of the concentration profile rises immediately with the increase in the Lewis number and the squeezed number . By contrast, Figure 9b and Figure 10b show the opposite phenomenon for both models in the case of injection ().

Figure 11a and Figure 12a demonstrate the impact of Brownian motion parameter and thermophoresis parameter on concentration profile . They demonstrate that for both models, and , is inversely proportional to Brownian motion and thermophoresis parameter . Figure 11b demonstrates that is directly proportional to Brownian motion , whereas Figure 12b demonstrates that is directly proportional to for both models and in the case of injection (), respectively.

5. Numerical Results

To validate our present study, the impact of different emerging parameters such as Hartmann number , microrotation parameter and local squeezed Reynold number on shear stresses, rate of heat transfer, and mass transfer are portrayed in tabulated form.

Table 2 and Table 3 illustrate how different emerging parameters of the model affect the skin friction coefficient in upper and lower planes with strong and weak . interactions. When , increasing Hartmann number M in the upper plane causes the skin friction coefficient to rise, but increasing Hartmann number M in the top plane causes the skin friction coefficient to fall. However, for both strong and weak connections, opposing behaviors are observed at the lower and higher planes for . As the local compressed Reynolds number Rr increases, the skin friction coefficient in the upper and lower planes decreases, resulting in both weak and strong interactions for and . The influence of the micropolar parameter K on the skin friction coefficient in both the upper and lower planes is equivalent to the Hartmann number M. As a result, for both strong and weak contacts, the skin friction coefficient at the top plane increases with increasing values of and for S > 0, but the opposite phenomenon occurs for rising values of and for . Similarly, Table 4 and Table 5 report on gamma alumina with ethyl glycol which we have observed for gamma alumina with water

Table 2.

Skin friction coefficient for at lower and upper plane with strong interaction .

Table 3.

Skin friction coefficient for at lower and upper plane with weak interaction .

Table 4.

Skin friction coefficient for at lower and upper plane with strong interaction .

Table 5.

Skin friction coefficient for at lower and upper plane with weak interaction .

The influence of the local Nusselt number on the model of Gamma Alumina with Water under the influence of physical parameters with strong and weak contacts at the upper and lower disks is explored in Table 6 and Table 7. For rising values of local squeezed Reynold number, in the presence of strong and weak contacts, the rate of heat transfer increases at the upper disc but decreases at the lower disc for both suction and injection. When the Brownian motion parameter is present, the rate of heat transfer decreases as the Brownian motion at the upper disc grows for both strong and weak contacts at a lower disc. However, for both and , the local Nusselt number is proportional to the thermophoresis parameter in the upper disc. In both circumstances of suction and injection, the inverse proportionality is observed at the lower discs. Similarly, in Table 8 and Table 9, the same phenomenon occurred for .

Table 6.

Local Nusselt number for at lower and upper plane with strong interaction .

Table 7.

Local Nusselt number for at lower and upper plane with weak interaction .

Table 8.

Local Nusselt number for at lower and upper plane with strong interaction .

Table 9.

Local Nusselt number for at lower and upper plane with weak interaction .

Table 10 and Table 11 indicate the effect of critical flow parameters on the local Sherwood number at the upper and lower discs for the model in the presence of weak and strong interactions. For , the rate of mass transfer at the upper plane rises as increases, whereas for both weak and strong contacts, the rate of mass transfer at the bottom plane decreases. However, the opposite behavior is expected for . The mass transfer rate is increased when there is an increase in Brownian motion parameter only at the upper plane, while at the lower plane the rate of mass transfer decreases for . Also, it decreases at both planes for . Similarly, when increases occur in the thermophoresis parameter, decreasing mass transfer occurs at the upper plane at both suction and injection, while the opposite behavior occurs at the lower plane at both suction and injection for both weak and strong interaction, respectively. However, for , the local Sherwood number is directly proportional to the Lewis number Le, but for , it is inversely proportional.

Table 10.

Local Sherwood number for at lower and upper plane with strong interaction .

Table 11.

Local Sherwood number for at lower and upper plane with weak interaction .

Table 12 and Table 13 indicate the effect of critical flow parameters on the local Sherwood number at the upper and lower planes for the model at both strong and weak contacts. For both strong and weak contacts, this model is the same as the above model for in both upper and lower planes. By contrast, for only the squeezed Reynolds number and Brownian motion parameters differ from the above model, indicating that as increases in the upper plane, it decreases in the lower plane. When increases, the Sherwood number also increases in the upper plane while it decreases in the lower plane.

Table 12.

Local Sherwood number for at lower and upper plane with strong interaction .

Table 13.

Local Sherwood number for at lower and upper plane with weak interaction .

6. Conclusions

A mathematical model of the micropolar squeezing flow of nanofluids between parallel disks is analyzed. We used two base fluids, ethyl glycol and water with suspended nanoparticles of First, we transformed a system of nonlinear PDEs into a set of ODEs by using similarity transformations. The major points from the presented results are as follows:

- The behavior of the micropolar parameter K on radial velocity and angular velocity h(ξ) in both suction and injection cases is polar opposite for both nanofluids, and .

- The effect of the Hartmann number M on the radial velocity for . At the wall, the radial velocity is inversely proportional, i.e., between and, but directly proportional at . For both models and , the opposite phenomenon is found for .

- Squeezed Reynolds number R has a direct proportional influence on angular velocity for and an inverse proportional effect for .

- For , the temperature profile θ(ξ) is directly proportional to the thermophoresis parameter for both models and , while only is inversely proportional to for r .

- For , a rise in the number of Lewis numbers Le raises the concentration profile while for the concentration profile drops as rises.

- The temperature of nanofluids is larger than that of the base fluids.

- The numerical values of the skin friction coefficient, the local Nusselt number, and the Sherwood number are tabulated in the presence of weak and strong interactions for both and .

- It is observed that the increase in angular velocity is rapid for throughout the study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.I.U.K.; and U.G.; methodology, U.G.; software, A.Z.; validation, H.X., U.G.; formal analysis, S.I.U.K.; investigation, A.Z.; resources, U.G.; data curation, W.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.I.U.K.; writing—review and editing, S.I.U.K.; visualization, H.X.; supervision, A.Z.; project administration, W.B.; funding acquisition, H.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation, grant number ZR2020ME100, by Heze University Natural Science Foundation, grant number XY21BS42.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

| is micro rotation of nanoparticles | |

| , | are the velocities in and directions, respectively |

| is concentration of nanoparticles | |

| is temperature | |

| is the effective density of nanofluid | |

| is the density of base fluid | |

| is the efficient thermal diffusion of nanofluid | |

| is the thermal diffusion of base fluid | |

| is the dynamic viscosity of nanofluid | |

| is the dynamic viscosity of base fluid | |

| is the effective Prandtl number of nanofluid | |

| is the Prandtl number of base fluid | |

| is vortex viscosity | |

| N | is kinematic viscosity |

| P | is pressure |

| represents specific heat capacitance. Furthermore, | |

| Is the Brownian motion coefficient | |

| is the thermophoretic diffusion coefficient | |

| is the mean fluid temperature | |

| is the effective electrical conductivity of the basefluid | |

| Is the electrical conductivity of basefluid | |

| is the nanoparticles volume fraction | |

| K | is the micropolar parameter |

| R | is the Reynold number |

| M | is the magnetic parameter (Hartmann number) |

References

- Rajagopal, K.R. Boundedness and Uniqueness of Fluids of Differential Type. Acta Sin. India 1982, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopal, K.R. On the Boundary Conditions for Fluids of the Differential Type. In Navier-Stokes Equation and Related Nonlinear Problems; Sequira, A., Ed.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 273–278. [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopal, K.R.; Szeri, A.Z.; Troy, W. An Existence Theorem for the Flow of Non-Newtonian Fluid Past an Infinite Porous Plate. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 1986, 21, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eringen, A.C. Theory of micropolar fluids. J. Math. Mech. 1996, 16, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ariman, T.; Turk, M.A.; Sylvester, N.D. Applications of Micro-Continum Fluid Mechanics. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 1974, 12, 273–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzat, M.A.; Othman, M.I.; Helmy, K.A. A Problem of Micropolar Magnetohydrodynamic Boundary Layer Flow. Can. J. Phys. 1999, 77, 813–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmy, K.A.; Idriss, H.F.; Kassem, S.E. MHD Free Convection Flow of a Micropolar Fluid Past a Vertical Porous Plate. Can. J. Phys. 2002, 80, 166–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, D.A.S.; Pop, I. Free Convection Boundary Layer Flow of a Micropolar Fluid from a Vertical Flat Plate. IMA J. Appl. Math. 1998, 61, 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, S.K.; Mathur, M.N. Similarity Solution for Laminar Free Convection Flow of Thermo-Micropolar Fluid Past a Nonisothermal Flat Plate. Int. J. Eng. 1981, 19, 1431–1439. [Google Scholar]

- Guram, G.S.; Smith, A.C. Stagnation Flows of Micropolar Fluids with Strong and Weak Interactions. Comput. Math. Appl. 1980, 6, 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmadi, G. Self Similar Solution of Incompressible Micropolar Boundary Layer Flow over Semi-Infinite Flat Plate. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 1976, 14, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazar, R.; Amin, N.; Filip, D.; Pop, I. Stagnation Point Flow of Micropolar Fluid towards a Stretching Sheet. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 2004, 39, 1227–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takhar, H.S.; Bhargava, R.; Agrawal, R.S.; Balaji, A.V.S. Finite Element Solution of a Micropolar Fluid Flow and Heat Transfer between Two Porous Discs. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 2000, 38, 1907–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, G.K.; Roopa, G.S.; Rauf, A.; Shehzad, S.A.; Abbasi, F.M. Time-dependent squeezing flow of Casson-micropolar nanofluid with injection/suction and slip effects. Int. Commun. Heat Transf. 2021, 126, 105470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumbinarasaiah, S.; Raghunatha, K.R.; Rezazadeh, M.; Inc, M. A solution of coupled nonlinear differential equations arising in a rotating micropolar nanofluid flow system by Hermite wavelet technique. Eng. Comput. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamshuddin, M.; Ibrahim, W. Finite element numerical technique for magneto-micropolar nanofluid flow filled with chemically reactive casson fluid between parallel plates subjected to rotatory system with electrical and Hall currents. Int. J. Model. Simul. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, T.; Xu, H. Time-dependent squeezing bio-thermal MHD convection flow of a micropolar nanofluid between two parallel disks with multiple slip effects. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2022, 31, 101850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sastry, V.S.R.K.; Kumar, N.N.; Kameswaran, P.K.; Shaw, S. Unsteady 3D micropolar nanofluid flow through a squeezing channel: Application to cardiovascular disorders. Indian J. Phys. 2022, 96, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usha, R.; Sridharan, R. Arbitrary squeezing of a viscous fluid between elliptic plates. Fluid Dyn. Res. 1996, 18, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duwairi, H.M.; Tashtoush, B.; Domseh, R.A. On heat transfer effects of a viscous fluid squeezed and extruded between two parallel plates. Heat Mass Transf. 2004, 14, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, R.J. Squeezing flow of Newtonian liquid films—analysis including fluid inertia. Appl. Sci. Res. 1976, 32, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.U.S.; Siginer, D.A.; Wang, H.P. (Eds.) Developments and Applications of Non-Newtonian Flows. In Proceedings of the 995 ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition, San Francisco, CA, USA, 12–17 November 1995; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Buongiorno, J. Convective Transport in Nanofluids. J. Heat Transfer. 2006, 128, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, C.V.; Fohanno, S.; Polidori, G.; Nguyen, C.T. Analysis of laminar-to- turbulent threshold with water γAl2O3 and ethylene glycol-γAl2O3 nanofluids in free convection. In Proceedings of the 5th IASME/WSEAS International Conference on Heat Transfer, Thermal Engineering and Environment, Athens, Greece, 25–27 August 2007; p. 188. [Google Scholar]

- Maré, T.; Sow, O.; Halelfadl, S.; Lebourlout, S.; Nguyen, C.T. Experimental study of the freezing point of γAl2O3 water nanofluid. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiki, H.; Esfahany, M.N.; Etesami, N. Laminar forced convective mass transfer of γAl2O3 electrolyte nanofluid in a circular tube. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2013, 64, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaieb, H.S.; Abdel-Hamid, H.M.; Shedid, M.H.; Helali, A.B. Engine cooling using γAl₂O₃/water nanofluids. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 115, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnu Ganesh, N.; Abdul Hakeem, A.K.; Ganga, B. A comparative theoretical study on Al2O3 and γAl2O3 nanoparticles with different base fluids over a stretching sheet. Adv. Powder Technol. 2016, 27, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, M.M.; Ganesh, N.V.; Hakeem, A.K.A.; Ganga, B.; Lorenzini, G. Influencesof an effective Prandtl number model on nano boundary layer flow of Al2O3–H2O and Al2O3–C2H6O2 and over a vertical stretching sheet. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2016, 98, 616–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh Irfanullah, K.; Mohyud-Din, S.T.; Yang, X.-J. Squeezing Flow of Micropolar Nanofluid between Parallel Disks. J. Magn. 2016, 21, 476–489. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.I.U.; Alzahrani, E.; Khan, U.; Zeb, N.; Zeb, A. On Mixed Convection Squeezing Flow of Nanofluids. Energies 2020, 13, 3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiga, S.E.B.; Nguyen, C.T.; Galanis, N.; Roy, G. Heat transfer behaviors of nanofluids in a uniformly heated tube. Superlattices Microstruct. 2004, 35, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).