Abstract

As AI decision support systems play a growing role in high-stakes decision making, ensuring effective integration of human intuition with AI recommendations is essential. Despite advances in AI explainability, challenges persist in fostering appropriate reliance. This review explores AI decision support systems that enhance human intuition through the analysis of 84 studies addressing three questions: (1) What design strategies enable AI systems to support humans’ intuitive capabilities while maintaining decision-making autonomy? (2) How do AI presentation and interaction approaches influence trust calibration and reliance behaviors in human–AI collaboration? (3) What ethical and practical implications arise from integrating AI decision support systems into high-risk human decision making, particularly regarding trust calibration, skill degradation, and accountability across different domains? Our findings reveal four key design strategies: complementary role architectures that amplify rather than replace human judgment, adaptive user-centered designs tailoring AI support to individual decision-making styles, context-aware task allocation dynamically assigning responsibilities based on situational factors, and autonomous reliance calibration mechanisms empowering users’ control over AI dependence. We identified that visual presentations, interactive features, and uncertainty communication significantly influence trust calibration, with simple visual highlights proving more effective than complex presentation and interactive methods in preventing over-reliance. However, a concerning performance paradox emerges where human–AI combinations often underperform the best individual agent while surpassing human-only performance. The research demonstrates that successful AI integration in high-risk contexts requires domain-specific calibration, integrated sociotechnical design addressing trust calibration and skill preservation simultaneously, and proactive measures to maintain human agency and competencies essential for safety, accountability, and ethical responsibility.

1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) is rapidly transforming high-risk decision making across critical domains where errors can have devastating consequences. From medical diagnostics and financial risk assessment to judicial rulings and military strategy, AI systems now influence decisions that can determine life or death, trigger massive financial losses, or cause widespread societal harm. Ensuring effective collaboration between humans and AI systems has become more urgent than ever before [1]. AI systems are increasingly capable of processing vast datasets, detecting complex patterns, and generating decision support recommendations with a speed and scalability that surpass human capabilities [2]. For instance, in intensive care units, the Targeted Real-time Early Warning System (TREWS) employs machine learning to analyze real-time physiological data, predicting sepsis risk hours in advance and issuing timely alerts. Clinicians integrate these AI-generated insights with their clinical expertise characterized by rapid, experience-based assessments to make informed decisions. Studies demonstrate that this human–AI collaborative approach, where clinicians evaluate and confirm TREWS alerts within 3 h while integrating AI predictions with their clinical judgment, significantly reduces sepsis-related mortality by 18.7% (adjusted relative reduction) compared to cases where alerts were not promptly confirmed [3]. More broadly, the 2024 Stanford HAI report highlights AI’s capacity to surpass human performance in specific tasks, enhance workforce efficiency, improve task quality, and narrow skill disparities among workers [4].

Intuitive decision making, defined as the human ability to make rapid and effective judgments based on experience, subconscious pattern recognition, and emotional cues without deliberate analytical reasoning, is central to human–AI collaboration. Enhancing intuitive decision making requires design strategies that align AI systems with human cognitive processes, supporting rapid, experience-based judgments while preserving decision-making autonomy (e.g., preserving human agency and final decision authority) [5]. Effective AI systems should provide insights through intuitive presentation and interaction approaches, fostering a symbiotic relationship that calibrates trust and promotes appropriate reliance on AI recommendations. Such collaboration not only improves decision-making efficiency but also yields superior outcomes in high-risk decision-making scenarios where errors carry severe consequences, such as emergency medical diagnoses, air traffic control decisions, or financial fraud detection requiring both rapid response and nuanced judgment.

As AI becomes increasingly prevalent in high-risk decision-making domains, the necessity for systematic investigation into human–AI collaboration has become critically important [1,2]. Existing research has extensively documented AI’s immediate advantages in task efficiency and accuracy [4,6]; however, comprehensive analyses investigating the long-term effects of sustained human–AI interaction on human cognitive strategies, decision-making capabilities, and professional competencies remain limited. For instance, research highlights cognitive risks such as automation bias, where over-reliance on AI recommendations can lead to diminished decision-making skills and mental inertia, particularly in healthcare settings where clinicians increasingly depend on AI-driven diagnostic tools [7,8]. Additionally, ethical challenges such as diminished clarity in accountability, especially in military applications involving autonomous weapon systems, underline critical gaps requiring attention [9,10].

Furthermore, the diverse requirements for AI decision support systems across distinct disciplines and application contexts complicate the development of universally adaptive, trustworthy systems. For example, medical diagnostic AI must prioritize transparency to foster clinician trust and patient safety [11], whereas AI systems in educational contexts must balance personalization with educator autonomy and pedagogical objectives [12,13]. These differing domain-specific demands highlight the complexity inherent in designing universally effective HAIC frameworks.

To address these challenges, this review synthesizes interdisciplinary perspectives to examine the following three critical dimensions: (1) design strategies that enable AI systems to support humans’ intuitive capabilities while maintaining decision-making autonomy; (2) the influence of AI presentation and interaction approaches on trust calibration and reliance behaviors; and (3) the ethical and practical implications of AI integration in high-risk decision making, with particular attention to trust calibration, skill degradation, and accountability across different domains. By focusing on these dimensions, this review aims to offer structured, evidence-based guidance for developing HAIC systems that enhance rather than replace human cognitive agency.

1.1. Background

1.1.1. From AI Tools to Collaborative Partners: An Evolution

Since its inception with Turing’s seminal work in 1950 [14] and the formal establishment of the field at Dartmouth [15], the field of artificial intelligence has undergone substantial theoretical and technological development, revolutionizing computational approaches to decision support. Early systems offered transparent but rigid assistance, while the rise in machine learning and deep learning enabled adaptive capabilities in tasks like image recognition and natural language processing, often at the cost of interpretability [16]. Since 2022, large language models and multimodal systems (e.g., GPT-4, Claude) have integrated language, vision, and reasoning, marking AI’s transition toward general intelligence and positioning it as a viable collaborator in complex decision making [17].

Contemporary AI systems transcend traditional automation, functioning as collaborative partners that augment human cognitive capabilities [18]. Professionals across fields such as medicine, finance, and engineering increasingly leverage AI to generate initial insights, optimize solutions, or validate judgments [1]. However, effective HAIC hinges on achieving appropriate reliance, wherein decision-makers neither over-rely on AI outputs nor dismiss them outright [19]. This balance requires AI systems to deliver not only accurate recommendations but also transparent, contextually relevant explanations that align with human cognitive processes, particularly in high-stakes decision-making environments.

The design of effective HAIC systems must be grounded in established theories of human cognition and decision making. Endsley’s model of situational awareness provides a foundational framework, emphasizing three critical levels: perception of relevant elements, comprehension of their current situation, and projection of future states [20]. For AI systems to support rather than hinder human awareness, their outputs must be structured to enhance all three levels without overwhelming cognitive capacity. Similarly, Cognitive Load Theory distinguishes between intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive load [21], suggesting that effective AI design should minimize irrelevant information processing while supporting meaningful pattern construction and respecting human cognitive limitations [22]. Klein’s Recognition-Primed Decision (RPD) model further illuminates how experts make rapid decisions in complex environments, advocating for AI systems that function as “intelligent aides” to amplify human pattern recognition rather than to replace expert judgment [23,24].

Effective collaboration requires appropriate reliance, balancing human intuition with AI recommendations [25]. AI explainability is critical for intuitive decision making, characterized by rapid, experience-based judgments informed by pattern recognition [26]. Explainable AI (XAI) refers to AI systems’ ability to provide interpretable and understandable outputs that allow users to comprehend how decisions are made [27]. This explainability enables users to validate AI recommendations against their expertise and make informed decisions about when to rely on AI assistance. For instance, in medical diagnostics, XAI systems provide transparent insights into diagnostic reasoning, helping clinicians understand the basis for AI recommendations and fostering appropriate trust in decision making [28].

These techniques enhance intuitive decision making by aligning AI outputs with human cognitive processes, reducing cognitive friction, and mitigating risks like automation bias [29]. The AI presentation and interaction techniques include various modalities: visual representations (such as saliency maps in medical imaging or decision paths in diagnostic systems), natural language explanations that articulate reasoning processes, interactive elements allowing users to query specific decisions, and uncertainty visualizations that communicate confidence levels. However, designing effective presentation and interactions demands a human-centered approach, tailoring interfaces to domain-specific needs and cognitive constraints [30]. As AI integrates into high-stakes decision making, investigation into presentation and interaction techniques is essential to ensure transparent, trustworthy, and intuitive HAIC. These presentation approaches directly influence how users calibrate trust and develop reliance patterns, which are critical factors in determining whether AI enhances or undermines human decision-making capabilities.

Trust in HAIC differs fundamentally from interpersonal trust due to the deterministic nature of AI systems and their lack of intentionality [31]. Computational trust models distinguish between cognitive trust (based on competence assessments) and affective trust (based on emotional bonds), with AI systems primarily relying on cognitive trust mechanisms [32]. Trust calibration is the alignment between a person’s level of trust in an automated system and the system’s actual trustworthiness or capabilities and the existing trust framework identifies three trust calibration states: appropriate trust (aligned with system capabilities), over-trust (exceeding system reliability), and under-trust (below system capabilities) [31]. This framework provides a theoretical foundation for designing AI systems that promote appropriate reliance through accurate capability communication and uncertainty expression [33].

1.1.2. Applications of HAIC

AI has evolved into an integral collaborative partner in complex decision-making processes. This evolution has enabled HAIC to deeply penetrate various vertical domains, revealing distinct collaborative patterns and challenges, particularly in high-risk decision environments where human intuition intersects with AI-driven insights. This section examines the manifestation and impact of HAIC across four critical domains: military, education, medical, and industry.

In the military, HAIC enhances the strategic planning, intelligence analysis, and management of autonomous systems [34,35]. AI platforms, for instance, support mission planning by providing advanced visualization and predictive analytics, enabling collaborative decision making between human commanders and AI systems [36]. Decision patterns here often involve humans setting strategic objectives while AI processes vast datasets to recommend tactical options [37]. Yet, challenges persist, including the opacity of AI reasoning, which can erode trust, and ethical dilemmas surrounding autonomous weapon systems, necessitating robust human oversight to align with international norms [38,39].

In education, HAIC facilitates personalized learning and automated assessment, tailoring educational experiences to individual student needs [12]. Intelligent tutoring systems exemplify this collaboration, with AI delivering adaptive content and feedback while educators interpret analytics to refine teaching strategies [13]. Decision patterns typically involve AI handling data-driven personalization and humans providing contextual judgment. Challenges include technical integration into existing systems, educator resistance due to unfamiliarity, and ensuring AI aligns with pedagogical objectives rather than overshadowing human roles.

In medical settings, HAIC manifests in diagnostic support, treatment planning, and patient monitoring [40,41]. AI algorithms enhance diagnostic precision by analyzing medical imaging and patient data, collaborating with clinicians who validate and contextualize findings [11]. Decision patterns often feature AI proposing evidence-based options while humans retain final authority to account for patient-specific factors. Research also demonstrates that this “hybrid intelligence” model combines the cognitive advantages of humans and AI, potentially achieving better outcomes than either could alone [1]. The collaborative approach is particularly valuable in diagnostic imaging, where AI assists in detecting patterns while physicians provide contextual interpretation and ethical judgment. However, challenges persist in data complexity, the need for interpretable AI outputs to build clinician trust, and ethical concerns over accountability in life-critical decisions [42,43].

In industry, HAIC drives human–robot collaboration, optimizing production through the synergy of AI’s computational capabilities and human creativity [44]. Collaborative robots (cobots) assist in real-time decision making on factory floors, with humans guiding adaptability to unforeseen changes [45]. Decision patterns here blend AI’s rapid data processing with human oversight for safety and innovation. Challenges include ensuring safe human–robot interactions, adapting to dynamic environments, and addressing ethical issues tied to workforce displacement and automation biases.

In summary, HAIC demonstrates remarkable potential for transforming decision-making processes across high-risk domain applications [46]. Each domain exhibits distinctive collaborative patterns: military and healthcare sectors predominantly utilize AI-assisted advisory decision models, while education and industrial settings employ more adaptive support-oriented decision frameworks. Despite domain-specific implementations, these collaborative systems face common challenges, including insufficient transparency, difficulties in establishing trust, and ethical conflicts [17,47]. Given the profound socioeconomic implications of these domains, continued in-depth research is essential to develop HAIC systems with domain adaptability, ethical safeguards, and appropriate human dependency mechanisms. This will help ensure that human–machine collaboration genuinely enhances both decision-making quality and outcomes in applications within these critical areas.

1.1.3. Ethical Concerns and Challenges

As AI transitions from a tool to a collaborative partner in high-stakes decision-making domains, its integration raises profound ethical questions that are inseparable from its design and practical implementation. These concerns not only highlight the limitations of current AI systems but also point to critical gaps that must be addressed to ensure effective and responsible HAIC.

Transparency and trust are the most significant issues. The “black box” nature of many AI systems obscures their decision-making processes, making it difficult for users to assess the validity of outputs or integrate them with their own intuition [48]. In domains such as healthcare and defense, where decisions carry ethical weight, opaque AI can erode trust and complicate accountability, leaving decision-makers uncertain about how to balance AI recommendations with their own expertise [19]. Furthermore, biases embedded in training data—whether from societal inequalities or developer assumptions—can lead to skewed outcomes, amplifying ethical risks and undermining fairness [5]. These challenges highlight the necessity for explanation methods that bridge the gap between AI reasoning and human understanding.

Privacy and data usage also pose dilemmas that intersect with collaboration dynamics. AI systems often rely on vast personal datasets, raising concerns about consent and security, particularly in sensitive areas like medical diagnostics and intelligence analysis [49]. As humans and AI iterate in a bidirectional learning process, the risks of data misuse or breaches grow, potentially compromising both user trust and system integrity. This interplay between ethical constraints and operational demands calls for AI designs that prioritize accountability and align with domain-specific values.

Together, these ethical dimensions—cognitive impacts, transparency, bias, and privacy—reveal a critical need to rethink how AI decision support systems are developed. Rather than viewing ethics as a secondary consideration, integrating these concerns into the design process is essential for fostering appropriate reliance, where humans leverage AI as a partner without losing agency or ethical grounding. Current research lacks a unified approach to address these issues, leaving gaps in how AI can be tailored to complement human intuition while mitigating risks [17].

This intersection of ethical challenges and collaborative design sets the stage for deeper gaps. How can AI systems be crafted to bolster human decision making without fostering over-dependence? What mechanisms can ensure transparency and trust in AI outputs? And what are the broader implications of these systems shaping human judgment across diverse domains? Addressing these questions is vital to unlocking the full potential of HAIC while safeguarding its integrity.

1.2. Existing Gaps

As AI decision support systems become increasingly integrated into critical domains, ensuring that decision-makers can effectively balance their intuition with AI recommendations is essential for trust, efficiency, and performance. Although the body of the literature on HAIC is expanding, the current research landscape remains fragmented. Previous systematic reviews have typically isolated specific dimensions of the partnership, focusing narrowly on trust metrics [33], technical explainability (XAI) [27], or domain-specific implementation hurdles [11]. This siloed approach obscures the complex interplay between system design and human cognition. For instance, a review focusing solely on XAI accuracy may miss how those same explanations inadvertently trigger cognitive overload or over-reliance in high-stress environments.

Furthermore, existing syntheses have predominantly adopted a descriptive rather than evaluative stance. While they catalog “what works” in controlled experiments, they often fail to critically assess methodological limitations, such as the reliance on mock tasks that do not reflect the high stakes of real-world decision making. Consequently, the “performance paradox”, where HAIC teams underperform despite superior AI accuracy, remains under-theorized in the context of the review literature.

Crucially, a significant void exists regarding the preservation of human intuition. While “human-in-the-loop” is a common concept, few comprehensive studies analyze how to design systems that actively sustain, rather than gradually erode, the expert’s intuitive judgment over time. There is a lack of unified frameworks that connect design features directly to long-term ethical outcomes like skill degradation and accountability gaps, necessitating a more critical and holistic investigation.

1.3. Research Questions

To address these gaps, this review aims to explore the development of AI systems and explanation methods that enhance human intuition and promote appropriate reliance in HAIC. By analyzing existing approaches, challenges, and effectiveness, this review seeks to provide actionable insights into designing AI-driven decision support systems that empower users to make informed and balanced decisions. This comprehensive review aims to address three research questions:

RQ1: What design strategies enable AI systems to support humans’ intuitive capabilities while maintaining decision-making autonomy?

RQ2: How do AI presentation and interaction approach influence trust calibration and reliance behaviors in HAIC?

RQ3: What ethical and practical implications arise from integrating AI decision support systems into high-risk human decision making, particularly regarding trust calibration, skill degradation, and accountability across different domains?

2. Methodology

This review utilizes a human–AI collaborative synthesis approach that aligns with the core principles examined in this review, leveraging AI to augment rather than replace human judgment. We detail our methodology in two primary aspects: the structured collection of the literature from multidisciplinary databases and the collaborative analytical framework designed to identify design principles, presentation and interaction techniques, and ethical considerations relevant to enhancing intuition and appropriate reliance in HAIC.

2.1. Search Strategy

After several iterations and refinements, we first established our search query by consulting with team members. Both primary and secondary terms are used in the search query; the former encompass synonyms and abbreviations of human–artificial intelligence collaboration and related methodologies, while the latter aid in finding publications that are pertinent to the use of intuition in decision making. The primary terms mainly consisted of “Human–AI Collaboration”, “Human–AI Interaction”, “Human–AI Teaming”, “Human–Machine Teaming”, and “Human–AI Partnership”, and the secondary terms consisted of “Intuition”, “Intuitive Decision Making”, “Intuitive Human Decision”, “Intuitive Cognitive decision”, “Intuitive Decision Accuracy”, “Intuitive Cognitive Approach”, and “Intuitive Cognitive Enhancement”. Both primary and secondary terminologies were searched in titles and abstracts. The research papers comprised diverse evidence from the 2018–2025 literature.

Keywords Boolean: (“Human–AI Collaboration” OR “Human–AI Interaction” OR “Human–AI Teaming” OR “Human–Machine Teaming” OR “Human–AI Partnership”) AND (“Intuition” OR “Intuitive Decision Making” OR “Intuitive Human Decision” OR “Intuitive Cognitive decision” OR “Intuitive Decision Accuracy” OR “Intuitive Cognitive Approach” OR “Intuitive Cognitive Enhancement”).

2.2. Screening and Eligibility

After formulating the search strategy, screening and eligibility assessments were conducted by considering the following exclusion criteria (EC):

EC1: Do not explicitly investigate HAIC.

EC2: Focus solely on AI or automated decision making without human involvement.

EC3: Do not provide sufficient methodological detail or empirical data.

EC4: Are not published in peer-reviewed journals, conference proceedings, or as registered reports.

2.3. Data Collection

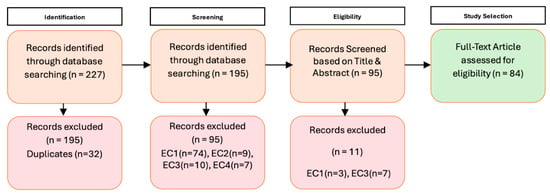

Although this study is not a systematic review, we incorporated key elements of the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) framework to guide the collection, screening, and filtering of the relevant literature [50]. In particular, we report the processes of the initial literature search, duplicate removal, screening against predefined criteria, and final study selection, structured into four main phases: identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion (shown in Figure 1). The application of PRISMA in this context is limited to strengthening the rigor of literature management.

Figure 1.

The process of study screening and selection.

2.4. Study Selection

To ascertain the data source, our team adhered to the methodology delineated in prior literature reviews [51]; we initially randomly selected 227 papers utilizing a search query across six databases, namely ACM Digital Library (ACM-DL), IEEE Xplore Digital Library (IEEE-XDL), ScienceDirect, Web of Science (Clarivate), PubMed (NIH), and Google Scholar. We then reviewed all the papers from each source: ACM-DL (60 paper collected), IEEE-XDL (20 paper collected), ScienceDirect (60 paper collected), Clarivate (20 papers collected), NIH (7 papers collected), and Google Scholar (60 papers collected). Items with duplicate titles (32 articles) and non-peer-reviewed full papers (7 articles) were removed before screening the remaining 188 articles.

In accordance with the four exclusion criteria, EC1-EC4, we started screening by independently reviewing the titles and abstracts of all the 227 identified articles (100%). During the process, the articles were assigned with “include” or “exclude” labels. Based on the screening of the titles and abstracts of all the articles, it resulted in 95 out of 227 articles for full-text review. In terms of eligibility, we then read the full text of each article and labeled them as “include” or “exclude.” Based on the full-text review, we excluded 11 articles in total according to the four exclusion criteria. As a result, we identified 84 out of 95 articles to be included in our final review. The inclusion/exclusion criteria were predefined to ensure that only relevant studies were included in the review.

2.5. Synthesis Methods: A Human–AI Collaborative Framework

To address the research questions, this review employs a human–AI collaborative synthesis method whose design philosophy aligns with the principles examined in this review—namely, that AI should augment human capabilities rather than replace human judgment. While AI-assisted systematic reviews represent an emerging methodological approach [52,53,54], we acknowledge this represents a methodological innovation that requires careful validation and transparency. Our collaborative framework embodies the principle of complementary role architecture: AI handles the efficient processing of structured information extraction tasks, while human researchers retain the ultimate authority over judgments concerning research relevance and scholarly value. The method involves four interconnected stages: (1) AI-assisted deep reading and information extraction, (2) human expert-informed judgment, (3) consensus building among human researchers, and (4) AI-assisted synthesis and report generation. This approach leverages the computational efficiency of AI for structured data extraction while prioritizing the nuanced judgment of human researchers in final decision making [55,56].

2.5.1. Stage 1: AI-Assisted Deep Reading and Information Extraction

Each of the 84 papers included was first processed by advanced large language models (Claude 3.7 Sonnet and Grok-3) for deep reading. Critically, the AI’s task was not to make “include/exclude” judgments, but rather to provide human researchers with structured information extraction, including the following:

- Precise summaries of research questions and objectives.

- Standardized extraction of methodological elements (study design, sample characteristics, and data types).

- Itemized organization of core findings.

- Preliminary annotations of potential relevance to the three research questions (RQ1-RQ3) with supporting textual evidence.

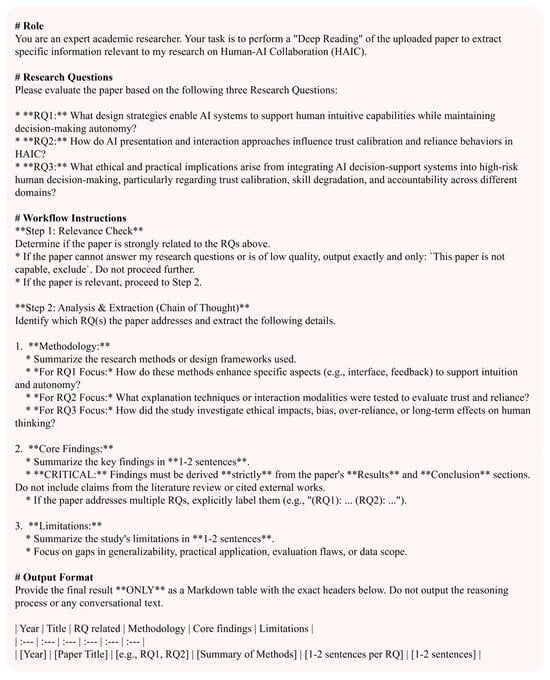

In this stage, AI functioned as a “research assistant”, providing comprehensive background information and preliminary analysis without making final judgments. We designed a structured prompt for AI (shown in Figure 2) to ensure the consistency and completeness of information extraction. Prior to the full-scale analysis, the prompt underwent iterative refinement and validation using a pilot subset of ten papers to ensure it could accurately and consistently extract the required structured information.

Figure 2.

Prompt design of LLM deep reading.

2.5.2. Stage 2: Human Expert-Informed Judgment

Two human researchers evaluated each paper with full access to the AI-extracted information. Unlike traditional independent double-blind reviews, our design enabled researchers to first review the AI-generated structured summary to quickly establish an overall understanding of the paper, then examine the original text with specific questions in mind, verifying key information and supplementing content that AI may have missed, and finally make judgments regarding relevance to the research questions.

This “AI information first, human judgment second” design embodies the principle of collaborative augmentation: the structured information provided by AI helps human researchers to focus more efficiently on core issues requiring professional judgment, rather than spending substantial amounts of time on basic information extraction. Human researchers evaluated each paper using a standardized checklist derived directly from the research questions to ensure consistency. For example, the checklist prompted reviewers to answer questions such as: “does this paper propose or evaluate specific design principles to enhance user intuition (RQ1)?” and “does it introduce or test presentation or interaction techniques for intuitive decision making (RQ2)?”. The researchers documented their judgments and cited specific text sections as evidence.

2.5.3. Stage 3: Consensus Building Among Human Researchers

The primary objective of this stage is to enhance the accuracy and validity of the review by resolving discrepancies between the two human researchers’ judgments regarding each article’s relevance to the research questions. Notably, disagreement resolution at this stage was entirely human-led—AI did not participate in arbitration, as relevance judgments fundamentally require scholarly expertise and value assessment.

When there was any disagreement, the reviewers held a focused discussion. They revisited the original article, explained their reasoning, and referred to specific text passages, until both reached an agreement. AI notes could be used to quickly find relevant sections, but they did not arbitrate the disagreement. If the two reviewers could not reach agreement, a third senior researcher examined the paper and made the final decision.

2.5.4. Stage 4: Final Synthesis

After human researchers completed all judgments, AI re-engaged to assist with the final synthesis work. Based on human-confirmed RQ assignments, AI generated standardized analysis reports for each paper, including the following:

- RQ relevance (e.g., RQ1, RQ2, RQ3, or multiple).

- Methodology (e.g., study design and data sources).

- Core findings (e.g., key results and implications).

- Limitations (paper-specific, AI analysis, and human judgment).

This framework was applied to the 84 studies that met the final eligibility criteria, while no papers were excluded during this synthesis phase. This method leverages AI’s ability to process and summarize large volumes of literature efficiently [57,58]. This collaborative workflow illustrates a complementary role architecture: AI handles large-scale, structured reading and drafting, while human experts retain control over all evaluative and interpretive judgments.

2.6. Effectiveness of the Human–AI Collaborative Approach

To evaluate the effectiveness of this collaborative method and ensure methodological transparency, we assessed both efficiency gains and inter-rater reliability.

Efficiency Gains Through AI Assistance. We assessed the time efficiency of our human–AI collaborative approach compared to traditional human-only review methods. Using the ten papers from the prompt optimization phase, we measured that independent human reading and evaluation required approximately 20–35 min per paper. In contrast, under our collaborative framework, where researchers reviewed AI-extracted summaries before the targeted examination of the original texts, the average processing time was reduced to under 8 min per paper across all 84 articles. This represents an efficiency improvement of approximately 60–75%, enabling researchers to allocate more cognitive resources to critical evaluation and synthesis rather than basic information extraction.

Inter-Rater Reliability Among Human Researchers. To assess the reliability of human judgments, we calculated inter-rater agreement between the two human researchers on RQ relevance classifications. The two researchers achieved a raw agreement rate of 95.2% (80 out of 84 papers). Only four papers required discussion to resolve disagreements, for which a consensus was reached for all through deliberation, without requiring arbitration by the third researcher. The disagreements primarily involved borderline cases where papers addressed multiple research questions with varying degrees of emphasis. These cases were resolved by examining the papers’ stated objectives and the relative depth of treatment for each topic.

3. Results

3.1. Review Findings and Discussions

3.1.1. Descriptives Statistics

Publication Year

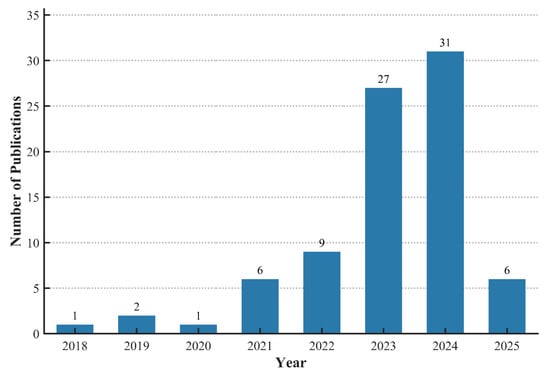

Since 2018, publications exploring HAIC have increased significantly, with 76.2% of the relevant papers (N = 64) published after this timepoint. This surge coincides with the late 2022 advancement of large language models and the industrial adoption of techniques (e.g., Retrieval-Augmented Generation), which mitigated AI limitations and established AI as a reliable decision-making partner. The research landscape consequently shifted toward HAIC, evidenced by post-2023 studies emphasizing trust dynamics, cognitive mechanisms, and practical applications—reflecting both scholarly interest and growing societal demand (shown in Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Frequency of the papers in each publication year.

The time distribution of the publications highlights distinct phases of HAIC development: Early Research (2018–2020): This stage primarily focused on theoretical frameworks and conceptual definitions, with limited empirical studies. Development Phase (2021–2023): This stage involved diversified research methods, expanded application domains, and extensive experimental validation. Recent Trends (2024–2025): This stage focused on (1) the increased application of generative AI in collaborative settings, (2) greater emphasis on interaction models and adaptive system design, (3) deeper explorations of ethical considerations and trust mechanisms, and (4) expansion into diverse professional fields and real-world applications.

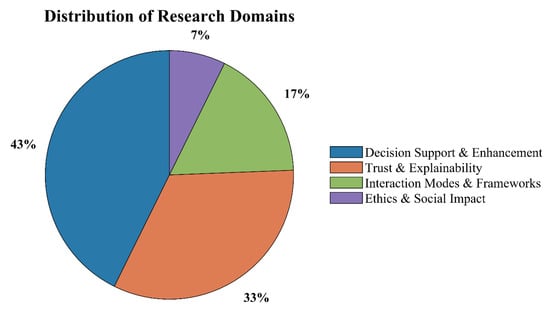

Research Domains’ Distribution

The literature reveals four distinct research clusters that capture the evolving landscape of HAIC, with Decision Support and Augmentation (35 papers, 42.7%) leads, focusing on enhancing decision making in fields like medicine and marketing. Post-2023 studies leverage generative AI for adaptive agents and decision-oriented dialogs. Trust and Explainability (27 papers, 32.9%) explores trust dynamics and explainable AI, with recent work (2024–2025) addressing trust calibration and cognitive biases. Interaction Patterns and Collaboration Boon Frameworks (14 papers, 17.1%) designs adaptive systems for seamless collaboration, emphasizing communicative agents in healthcare and security. Ethics and Social Impact (6 papers, 7.3%) examines moral implications and standardization, particularly in aviation and ethical decision making (shown in Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Categorization of HAIC by research by domain.

Research Methods’ Distribution

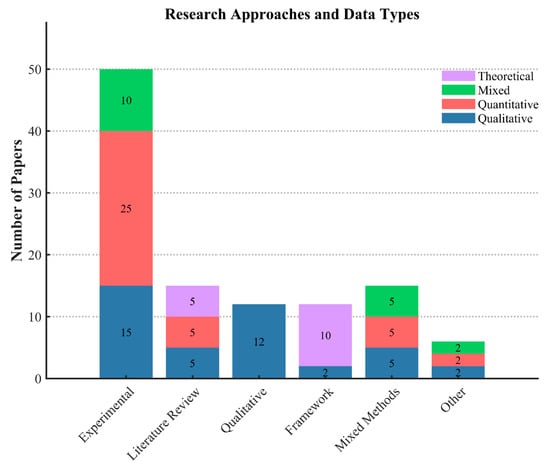

Research methodologies in HAIC studies demonstrate diverse approaches to data collection and analysis, with experimental studies (41.5%, N = 34) dominating the field, primarily utilizing quantitative (70.6%) and mixed methods (29.4%) to validate metrics such as trust calibration. Literature reviews (18.3%, N = 15) and mixed methods studies (18.3%, N = 15) each employ balanced distributions of data types. Qualitative studies (14.6%, N = 12) exclusively use qualitative data to capture user experiences, particularly in healthcare settings. Framework/theoretical studies (13.4%, N = 11) predominantly rely on theoretical data (81.8%) to develop conceptual models. The remaining studies (7.3%, n = 6) distribute evenly across qualitative, quantitative, and mixed approaches, often addressing specialized applications (shown in Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Categorization of HAIC research by Approaches and Data Types.

3.2. RQ1: What Design Strategies Enable AI Systems to Support Humans’ Intuitive Capabilities While Maintaining Decision-Making Autonomy?

The 63 studies addressing RQ1, spanning from 2018 to 2025, reveal four primary design strategies that enable AI systems to support humans’ intuitive capabilities while preserving decision-making autonomy. These strategies emerge from research demonstrating that effective HAIC requires systems that amplify rather than replace human judgment, adapt to individual decision-making styles, and provide users with meaningful control over the decision process. The identified strategies are: (1) complementary role architecture, (2) adaptive user-centered design, (3) context-aware task allocation, and (4) autonomous reliance calibration.

3.2.1. Strategy 1: Complementary Role Architecture

Three theoretical positions have emerged regarding how human–AI complementarity should be structured. The first, represented by Reverberi et al. [1], frames complementarity as Bayesian belief revision; endoscopists in their study integrated AI recommendations with clinical assessments while retaining diagnostic control. This approach positions humans as the integrators of multiple information sources rather than the passive recipients of AI outputs. Wang et al. reported analogous findings among IBM data scientists, who viewed Auto-AI as a collaborator automating routine tasks while requiring human domain expertise [59]. However, Reverberi et al.’s study was restricted to colonoscopy with a high-accuracy AI (~85%), leaving it unclear whether results generalize to lower-accuracy systems or other clinical domains. Wang et al.’s single-organization sample introduces potential selection bias.

A second position emphasizes complementarity in domains requiring emotional or creative judgment. Sharma et al. demonstrated that AI feedback increased conversational empathy by 19.6% among peer supporters while preserving response autonomy [47]. Petrescu and Krishen extended this argument to marketing, where AI handles data analysis while humans retain content creation authority [60]. This perspective suggests complementarity is most valuable where AI capabilities are weakest. The limitation is empirical thinness: Sharma et al.’s study lasted only 30 min in a non-clinical setting, and Petrescu and Krishen’s analysis remains theoretical without implementation evidence.

A third position directly challenges complementarity’s effectiveness. Vaccaro et al.’s meta-analysis of 106 studies found that human–AI combinations underperformed the best individual agent (Hedges’ g = −0.23), though they exceeded human-only performance (g = 0.64) [18]. Task type moderated this effect: decision tasks showed losses while creative tasks showed gains. Scholes’s research reinforced this concern, noting that while AI effectively predicts average outcomes, humans remain critical for rare high-stakes events—yet often fail to recognize when override is appropriate [61]. These findings indicate that complementarity may be constrained by coordination costs or inadequate designs for leveraging distinct capabilities.

Recent works have attempted to reconcile these positions. Cai et al. found that pathologists required comprehensive information about AI capabilities and limitations to determine effective partnership strategies—suggesting that metacognitive support may mediate complementarity’s success [62]. Xu et al. reported similar findings in a single-case analysis of AI augmentation, though the single-case design limits generalizability [63]. The Kase et al. framework for military decision making proposed progressive levels of collaboration from transparent AI to theory-of-mind teaming, but remains unvalidated empirically [36].

The divergence between these positions reflects a deeper theoretical uncertainty about human metacognitive capacity in HAIC. The Bayesian integration view assumes humans can accurately weight AI recommendations against their own intuitions, but the performance paradox evidence suggests this assumption is frequently violated. If humans systematically mis-calibrate their reliance, over-relying when AI errs and under-relying when AI excels, then complementarity’s benefits may be inherently limited regardless of role architecture design. The emotional intelligence preservation perspective sidesteps this problem by restricting complementarity to domains where AI contributions are auxiliary rather than central, but this retreat substantially narrows the scope of effective human–AI collaboration. What remains absent from the literature is the systematic investigation of whether metacognitive training or interface scaffolding can close the gap between theoretical complementarity and observed performance, and whether the task-type moderation identified by Vaccaro et al. [18] reflects fundamental cognitive constraints or merely current design limitations.

3.2.2. Strategy 2: Adaptive User-Centered Design

Research on adaptive design divides between computational adaptation and interactive co-creation approaches. Computational adaptation aims to automatically adjust AI support based on inferred user states. Ding et al. developed a Bayesian trust model achieving 97.6% accuracy in predicting appropriate trust levels by adapting to task difficulty and user confidence [64]. Hauptman et al. showed that adaptive autonomy in cybersecurity—higher automation for predictable tasks, lower for uncertain ones—improved collaboration by matching workflow patterns [65]. Both approaches share a critical limitation: Ding et al.’s model assumes rational decision making, neglecting cognitive biases; Hauptman et al.’s hypothetical scenarios may not reflect operational behavior.

Interactive co-creation takes a different approach, involving users in shaping AI assistance. Gomez et al. found that user participation in AI prediction generation for bird classification increased recommendation acceptance and teamwork perceptions [66]. Muijlwijk et al. showed that allowing marathon coaches to modify feature weights improved both model acceptance (β = 0.266, p < 0.001) and prediction accuracy (error reduced from 3.14% to 2.33%) [67]. The mechanism proposed is that co-creation develops more accurate mental models of AI capabilities. However, Gomez et al. used a simplified AI with static predictions and academically sophisticated participants; Muijlwijk et al.’s findings are domain-specific to marathon running with analysis limited to unfamiliar runners.

Several studies have explored scaffolding approaches that bridge computational adaptation and co-creation. Liu et al. developed Selenite, using LLM-generated overviews and questions to accelerate interdisciplinary sensemaking while preserving researcher autonomy [68]. Zheng et al. demonstrated DiscipLink’s human–AI co-exploration for information seeking [69]. Shi et al. showed that chemists using RetroLens for molecular deconstruction experienced reduced cognitive load, though the system’s static recommendation pathways limited flexibility [70]. Pinto et al. proposed conversational decision support for supply chain management, but their framework lacks a technology assessment with regard to implementation [71].

Evidence suggests adaptation requirements vary by user characteristics. Meske and Ünal tested five automation levels in face recognition and found no universal optimum—preferences varied significantly across individuals [72]. This finding challenges both pure computational adaptation and one-size-fits-all co-creation approaches. Choudari et al. proposed human-centered automation for data science, preserving intuitive decision making, but their framework awaits empirical validation [60]. The ongoing research by Kumar on effective HAIC acknowledges potential data accessibility challenges and the rapidly evolving AI landscape [73].

The computational adaptation versus co-creation debate may ultimately prove to be a false dichotomy, as both approaches rest on untested assumptions about what enables effective personalization. Computational adaptation assumes that user states can be accurately inferred from behavioral signals and that optimal support configurations can be derived from these inferences—yet the evidence that self-reported measures fail to align with behavioral measures [74] suggests that even users themselves may not have accurate insight into their support needs [74]. Co-creation approaches assume that user involvement enhances mental model accuracy and thereby improves reliance calibration—yet Gomez et al.’s [66] finding that interaction may inadvertently increase over-trust suggests that involvement does not guarantee appropriate calibration. The field’s reliance on small samples of technology-familiar academics (Zheng et al. with eight pharmacists [75]; Park with twenty participants [76]; and Meske and Ünal with twenty-four participants [72]) raises serious questions about whether findings would replicate with technology-naive populations or in domains where users lack the baseline expertise to evaluate AI capabilities. Until research addresses these foundational uncertainties—through studies with diverse populations, realistic AI systems with known imperfections, and longitudinal tracking of adaptation effects—recommendations for adaptive design remain premature.

3.2.3. Strategy 3: Context-Aware Task Allocation

Context-aware allocation addresses how decision-making responsibilities should be distributed based on task characteristics and situational factors. Research divides between taxonomic approaches specifying predetermined allocations and dynamic approaches adjusting in real-time.

Taxonomic approaches aim to classify tasks by optimal human–AI division. Korentsides et al. adapted the HABA-MABA framework for aviation, allocating skill-based and rule-based tasks to AI while preserving human authority over knowledge-based and expertise-based decisions [77]. Gomez et al. identified seven interaction patterns across 105 studies, including AI-first and request-driven approaches [46]. Their key finding was that current designs inadequately support complex interactive tasks. Both contributions are primarily theoretical: Korentsides et al. acknowledge lacking empirical validation or implementation examples; Gomez et al.’s taxonomy excluded robots and gaming, potentially missing important interaction modalities.

Dynamic allocation approaches argue that task characteristics alone cannot determine optimal division—situational demands must be incorporated. Schoonderwoerd et al. demonstrated that sitrep and knowledge–rule interaction patterns improved urban search-and-rescue performance [78]. Jalalvand et al. showed that human–AI teaming in alert prioritization improved performance through the automation of routine tasks, with human control over novel threats [79]. Chen et al. proposed adaptive frameworks for security operations centers to mitigate alert fatigue [80]. These studies face ecological validity concerns: Schoonderwoerd et al. used wizard-of-Oz methods with static AI in simplified virtual environments; Jalalvand et al. acknowledged limited focus on augmented collaboration and absence of practical user validation.

Task complexity moderates’ allocation effectiveness. Lin et al. found GPT-3 underperformed compared to human assistants in goal-directed planning despite generating longer dialogs, suggesting humans should retain strategic decision control [81]. The study primarily evaluated GPT-3, with uncertain generalization to newer models. Hao et al. reported the limited effectiveness of AI in creative tasks where human intuition has advantages—some AI suggestions were impractical or overlooked cultural factors [82]. Dodeja et al. found that participant diversity was limited (ages 18–30) and testing used a Risk boardgame rather than real-world tasks [37].

Temporal dynamics add another dimension. Flathmann et al. found that decreasing AI influence over time enhanced human performance, while sustained high influence increased cognitive workload [83]. This suggests allocation should not be static but should evolve as collaboration develops. However, the study used a low-risk gaming context with college-age participants. Ghaffar et al. demonstrated that comprehensive data availability improved optometry diagnostic accuracy for both novices and experts, but with only 14 optometrists from one geographic region in simulated rather than real-time clinical scenarios [84].

The tension between taxonomic and dynamic approaches reflects a fundamental uncertainty about the stability of optimal task allocation. Taxonomic approaches implicitly assume that task characteristics are sufficiently stable and predictable, allowing predetermined allocations to be specified, yet the evidence from dynamic allocation research suggests that situational factors not captured by task taxonomies substantially influence optimal division. More troubling are the temporal dynamics findings from Flathmann et al. [83], which suggest that even within a single task context, optimal allocation may shift as users develop expertise or experience cognitive fatigue—a complexity that neither taxonomic nor current dynamic approaches adequately address. The predominance of virtual environments and gaming contexts in this literature raises additional concerns: allocation strategies effective in simplified low-stakes settings may fail catastrophically in safety-critical operational contexts where errors carry severe consequences. The finding from Lin et al. [81] that GPT-3 underperformed human assistants in strategic planning—despite being allocated precisely the kind of reasoning-intensive task that taxonomies would suggest favoring AI—indicates that current models of AI capability may systematically overestimate performance in complex real-world conditions. Until allocation strategies are validated in authentic operational settings with consequential outcomes, their practical utility remains speculative.

3.2.4. Strategy 4: Autonomous Reliance Calibration

Autonomous reliance calibration shifts focus from system-level optimization to empowering users to calibrate their own reliance on AI. This strategy acknowledges that no amount of system design can substitute users’ metacognitive capacity.

Research has identified specific mechanisms through which users appropriately reject AI recommendations. Chen et al. documented three intuition-driven override pathways: strong outcome intuition, discrediting AI through feature analysis, and recognizing AI limitations [29]. All pathways improved outcomes when users detected AI unreliability. Rastogi al. examined cognitive biases in AI-assisted decision making, finding that non-expert participants limited generalizability to expert domains [85]. Chen et al.’s study used think-aloud protocols that may have artificially increased engagement [29], and participants skewed toward highly educated, ML-experienced individuals.

Interactive calibration offers structured approaches. Muijlwijk et al. showed that case-based reasoning systems allowing coaches to test predictions against expertise improved both acceptance and accuracy [67]. Paleja et al. demonstrated that interactive policy modification in financial forecasting outperformed static approaches [86]. The mechanism appears to involve users developing refined mental models through structured interaction. However, Paleja et al.’s Overcooked-AI environment with university students may not be generalizable to complex real-world tasks.

The relationship of explainability to calibration is more complex than initially assumed. Rosenbacke found that explainable AI increased trust but risked promoting over-reliance, leading to undetected errors [87]. This occurred specifically through “False Confirmation” errors where clinicians failed to identify AI mistakes. The study’s small sample and focus on recurrent ear infections limit generalizability. Jang et al. showed that explanation effectiveness diminishes with supervision in an ‘explanation–action tradeoff’, where greedy explanation methods limit future feedback opportunities [76].

System reliability critically affects calibration. Kreps and Jakesch demonstrated that AI-mediated communication with human oversight increased trust when AI performed well, but poor performance eroded confidence [88]. The study used crowd workers rather than real constituents and investigated only GPT-3. Schemmer et al. found that deception detection tasks with low human performance limited appropriate reliance development [89]. Chakravorti et al. proposed prediction markets as calibration mechanisms [90], but used simplistic behavioral primitives in simulations rather than actual human participants.

Recent works have explored uncertainty communication for calibration. Xu et al. examined how LLM-verbalized uncertainty influences reliance, but findings were limited to U.S. participants familiar with AI and to specific uncertainty framings [91]. Tutul et al. found that agreement with a single expert for ground truth and reliance on self-reports to measure trust may miss behavioral indicators [92].

The autonomous reliance calibration strategy confronts a fundamental paradox that the preceding strategies do not resolve: the very transparency mechanisms designed to support calibration may undermine it. Rosenbacke’s [87] finding that explainable AI can promote over-reliance through “False Confirmation” errors suggests that making AI reasoning visible does not straightforwardly enable users to identify when AI is wrong—it may instead provide false assurance that errors have been checked for and ruled out. This paradox is compounded by Jang et al.’s explanation–action tradeoff [76], which indicates that calibration support through explanation may come at the cost of future learning opportunities. The field’s assumption that well-designed explanations will enable appropriate calibration appears increasingly untenable in light of this evidence. More fundamentally, Chen et al.’s intuition-driven override pathways require precisely the kind of domain expertise and metacognitive sophistication that cannot be assumed in general user populations—their participants were highly educated and ML-experienced, representing the ceiling rather than the floor of calibration capacity [29]. The question of whether autonomous calibration is a viable strategy for typical users in typical deployment contexts, rather than expert users in controlled studies, remains unanswered. If calibration depends on capabilities that most users lack, the entire framework of human–AI collaboration may require reconceptualization around systems that do not presuppose metacognitive competence.

3.2.5. Supporting Evidence and Implementation Considerations

Implementation research reveals barriers that cut across strategic approaches. Syiem et al. found that adaptive agents in augmented reality mitigated attentional issues technically but produced no significant overall task performance improvement—benefits were limited to receptive users [93]. Schmutz et al. reported that AI implementation often reduces team coordination effectiveness, with most findings based on laboratory rather than organizational settings [94].

Organizational and domain factors significantly moderate implementation success. Judkins et al. found AI recommendations significantly underutilized in IT project selection, with small sample sizes and measurement issues with trust scales [95]. Daly et al. showed that healthcare professionals prioritize reliability and accountability while creative professionals emphasize originality and autonomy—the study acknowledged gender imbalance and self-selection toward technology-interested participants [96]. Lowell et al. found small business contexts (70% with 1–50 employees) may not represent enterprise environments [97].

User perception may diverge from actual effectiveness. Hah and Goldin found clinicians demonstrated positive sentiments toward AI (sentiment score 0.92) despite no performance improvements [98]. The study’s small purposive sample (N = 114) and binary operationalization of AI assistance limit interpretation. Papachristos et al. found that lab settings with specific prototypes limit real-world generalizability [99].

The four strategies examined in RQ1 represent a coherent theoretical framework for supporting humans’ intuitive capabilities in HAIC. Yet the evidence reveals that this framework remains largely aspirational. The performance paradox documented by Vaccaro et al. [18] indicates that human–AI combinations frequently fail to achieve complementarity’s theoretical benefits, underperforming the best individual agent in decision tasks. The adaptive design literature is fragmented between computational and co-creation approaches, neither of which has been validated with diverse, technology-naive populations facing realistic tasks. Context-aware allocation research relies predominantly on virtual environments and gaming contexts that cannot establish ecological validity for safety-critical applications. Autonomous calibration mechanisms face the troubling finding that transparency may promote rather than prevent over-reliance. Across all four strategies, longitudinal research tracking how collaboration dynamics evolve over extended periods is almost entirely absent—a critical gap given that skill development, trust formation, and reliance calibration are inherently temporal processes. The field has generated rich theoretical models but has not yet demonstrated that these models translate into effective real-world implementations. What is needed is not the further elaboration of design principles but rigorous validation studies in authentic operational contexts with diverse user populations and consequential outcomes.

3.3. RQ2: How Do AI Presentation and Interaction Approaches Influence Trust Calibration and Reliance Behaviors in HAIC?

This section presents findings from 34 studies examining how different AI presentation and interaction approaches affect trust calibration and reliance behaviors in HAIC systems.

3.3.1. How AI Systems Present Information to Users

Method 1: Visual Presentations-Showing Users What AI “Sees”

Visual presentation techniques emerged as the most extensively studied approach for influencing trust calibration and reliance behaviors. Feature-based visual presentation, particularly Class Activation Maps (CAMs) with traditional red–blue coloring schemes, significantly improved both diagnostic accuracy and physician confidence in medical imaging applications for detecting thoracolumbar fractures [100]. The effectiveness of these visual presentations was enhanced when they aligned with users’ existing cognitive models, suggesting that domain-appropriate visual design is crucial for successful trust calibration.

In cybersecurity contexts, Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME) and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) visualizations enhanced interpretability and increased human trust in AI decisions for malware detection tasks [101]. However, the complexity of visual presentations proved to be a critical moderating factor. Simple visual highlights consistently outperformed more complex presentation in reducing over-reliance on AI systems during difficult tasks [102]. This finding indicates that excessive presentation complexity can increase perceived task difficulty, potentially impairing user trust calibration and compliance [103].

Method 2: Learning Through Examples: How AI Shows Similar Cases

Example-based presentation methods demonstrated distinct effects on trust calibration and reliance behaviors compared to feature-based approaches. These presentations provided concrete instances illustrating AI reasoning, which were found to be less disruptive to users’ natural intuition and promoted inductive reasoning patterns [29]. Importantly, example-based presentations provided clearer signals of AI unreliability, supporting appropriate reliance behaviors by helping users identify when AI systems might fail.

However, the quality of examples significantly influenced trust calibration outcomes. When example-based presentations contained errors, they proved more deceptive than natural language alternatives, affecting reliance behaviors differently across expertise levels [104]. This finding highlights the critical importance of presentation accuracy in maintaining appropriate trust calibration.

3.3.2. How Users Interact and Collaborate with AI Systems

Method 1: Giving Users Control: Interactive Features and User Agency

Interactive frameworks that enabled user engagement with AI recommendations demonstrated particularly strong effects upon trust calibration and reliance behaviors. Interactive prediction models allowing users to adjust feature weights showed significant benefits for both user perception and behavioral outcomes. When coaches could modify the importance weights of previous races in marathon finish time predictions, both the acceptance of the model’s recommendations and perceived model competence improved substantially [67]. Notably, this interactive approach also improved the model’s prediction accuracy, suggesting mutual benefits from collaborative human–AI interaction.

Similar collaborative benefits were observed in financial forecasting tasks, where interactive policy modification led to significant team development and outperformed static approaches to promoting appropriate reliance behaviors [86]. These interactive approaches enabled deeper engagement with AI systems and addressed individual user needs and preferences in trust calibration.

Method 2: Expressing Uncertainty: How AI Communicates Confidence Levels

The communication of AI system confidence and uncertainty emerged as a crucial factor in trust calibration and reliance decision making. The explicit display of correct likelihood information proved effective in promoting appropriate trust behaviors. Research comparing three strategies based on estimated human and AI correctness likelihood—Direct Display, Adaptive Workflow, and Adaptive Recommendation—found that all three approaches promoted more appropriate human trust in AI, particularly reducing over-trust when AI provided incorrect recommendations [105].

The design of uncertainty presentations significantly influenced their effectiveness in influencing reliance behaviors. In pharmacy medication verification tasks, histogram visualizations of prediction probabilities and “confused pill” displays improved transparency and trust in AI recommendations [75]. Higher transparency through revealing top AI recognitions increased understandings of and trust in AI capability while reducing perceived workload, contributing to better calibrated reliance behaviors [76].

Method 3: Explaining the Process: How AI Describes Its Decision Making

Contextual and process-based interaction approaches focused on explaining how and why AI decisions were made, influencing both trust and reliance through enhanced understanding. The concept of Shared Mental Models (SMMs) provided a theoretical foundation for these approaches, with explainable AI serving as a key enabler for establishing SMMs in human–AI teams by allowing humans to form accurate mental models of AI teammates [106].

Explanatory dialogs and justifications improved collaboration effectiveness and influenced reliance behaviors. AI systems providing justifications and AR-based visual guidance demonstrated improved task performance, shared awareness, and reduced errors compared to systems without these explanatory elements [107]. These approaches were particularly effective when combined with prescriptive and descriptive guidance that contextualized AI recommendations within the user’s task environment.

3.3.3. Effects on User Trust: How Much Users Believe in AI

The various presentation and interaction approaches demonstrated profound but varied effects on trust calibration. Feature-based visual methods like Grad-CAM in medical imaging increased physicians’ diagnostic trust by aligning with familiar cognitive models, while LIME/SHAP approaches in cybersecurity applications bolstered experts’ confidence through clear decision rationales [101]. These approaches achieved trust enhancement by making AI reasoning visible and connected to domain knowledge.

Interactive presentation frameworks significantly boosted trust calibration by providing users with agency in the AI process. The co-creation aspect of these interactions appeared to enhance perceived reliability through the shared ownership of the outcomes [67]. Transparency mechanisms, such as revealing the top five AI recognitions and showing correct likelihood information, calibrated trust by revealing AI capabilities and often reduced workload perceptions and uncertainty [76,105].

However, trust calibration effects were not universal across all approaches. Several studies identified contextual complications, including the potential for explainable AI to sometimes lead to over-trust [87], and the significant effect of confirmation bias on trust development when AI recommendations aligned with users’ initial judgments [108]. In clinical settings, explanatory visualizations increased clinicians’ perceptions of AI usefulness and their confidence in AI’s decisions yet did not significantly affect binary concordance with AI recommendations, suggesting that trust calibration effects may manifest in subtle ways beyond simple compliance measures [109].

3.3.4. Effects on User Behavior: How Users Actually Use AI Recommendations

Beyond trust calibration, presentation and interaction approaches directly shaped user reliance patterns with significant implications for decision quality and human–AI complementarity. Visual presentation techniques, particularly simple visual highlights, demonstrated effectiveness in reducing over-reliance on AI systems during difficult tasks compared to prediction-only or written presentation techniques [102]. Example-based presentations provided stronger signals of AI unreliability, potentially preventing the blind acceptance of incorrect recommendations [29].

However, some interactive approaches revealed potential tensions in reliance behaviors. While user engagement increased, certain interactive methods may inadvertently increase over-trust by boosting confidence in co-created outputs [66]. This finding highlights a critical design challenge in balancing user engagement with appropriate skepticism.

Confidence and uncertainty information proved particularly effective at guiding appropriate reliance behaviors. Providing accurate information about AI recommendations led to better calibrated trust, with participants deviating more from low-quality recommendations and less from high-quality ones [74]. Similarly, correctness likelihood strategies effectively promoted appropriate trust in AI, especially in reducing over-trust when AI provided incorrect recommendations [105].

3.3.5. What Influences These Effects: Key Factors That Matter

Several factors moderated the relationship between presentation/interaction approaches, and trust calibration and reliance behaviors. The relationship was influenced by user expertise levels, with the impact of different presentation types varying between novices and experts, as each group utilized different aspects of the presentations in their decision making [29].

The content characteristics of presentations also moderated effects. Feature-based presentations highlighting task-relevant versus gendered features in occupation prediction tasks had different effects on stereotype-aligned reliance, demonstrating how presentation content can influence fairness perceptions and reliance behaviors [110].

Error types significantly influenced reliance patterns, with research showing that humans were less likely to delegate complex predictions to AI when it made rare but large errors, driven by higher self-confidence rather than lower confidence in the model [111]. Additionally, humans violated choice independence in HAIC, with errors in one domain affecting delegation decisions in others.

In clinical settings, a more nuanced picture of reliance behaviors emerged beyond simple acceptance or rejection patterns. Clinicians demonstrated four distinct behavior patterns when engaging with AI treatment recommendations: ignore, negotiate, consider, and rely [109]. This “negotiation” process highlighted that reliance behaviors represent complex, multi-faceted responses that extend beyond binary measures and are significantly influenced by how AI systems present information and enable interaction.

In summary, the research on presentation and interaction approaches reveals a field that has generated numerous interventions without establishing the fundamental conditions under which they succeed or fail. The paradox—simpler explanations outperforming sophisticated alternatives—challenges the core assumption driving XAI development that more comprehensive explanations enable better decisions. Yet even this apparently robust finding may be an artifact of the laboratory contexts in which it was established: Vasconcelos et al.’s [102] ‘perfect’ explanations bear little resemblance to the imperfect explanations real XAI systems produce, and Morrison et al.’s [104] demonstration that imperfect example-based explanations are more deceptive than their alternatives suggests that findings from idealized conditions may reverse in deployment. The trust–behavior dissociation documented by Sivaraman et al. [109] and Eisbach et al. [74] poses a fundamental challenge to intervention evaluation: if self-reported trust does not predict behavioral reliance, then studies relying on trust self-reports—which constitute the majority of this literature—may systematically misestimate intervention effectiveness. The confirmation bias findings from Bashkirova and Krpan [108] further complicate interpretation, suggesting that apparent trust improvements may reflect motivated reasoning rather than genuine calibration. What emerges from this synthesis is not a set of validated design recommendations but rather a catalog of phenomena that current research has documented without explaining or resolving. The field requires a fundamental shift from demonstrating that interventions can affect trust or reliance in controlled conditions to understanding when, why, and for whom specific approaches succeed or fail in authentic deployment contexts.

3.4. RQ3: What Ethical and Practical Implications Arise from Integrating AI Decision Support Systems into High-Risk Human Decision Making, Particularly Regarding Trust Calibration, Skill Degradation, and Accountability Across Different Domains?

The integration of AI decision support systems into high-risk human decision-making contexts generates complex ethical and practical implications that fundamentally challenge traditional models of human agency, accountability, and competence. Our analysis reveals three primary areas of concern directly addressing RQ3: trust calibration challenges, skill degradation risks, and accountability gaps, each with distinct manifestations across high-risk domains.

3.4.1. Challenge 1: Trust Calibration Challenges in High-Risk Contexts

Generalized Trust Formation and Its Risks

Effective trust calibration in human–AI systems requires ongoing, context-sensitive adjustments based on user experience and situational demands [112]. The Human–Automation Trust framework identifies key factors shaping trust: system attributes such as reliability, predictability, and transparency, along with human factors such as expertise, workload, and individual differences [113].

Trust calibration in AI decision support systems presents unique challenges that differ fundamentally from human-to-human trust dynamics. Research demonstrates that humans tend to generalize trust or distrust from one AI system to all AI agents, unlike with human teammates where trust is assessed individually [114]. This generalization becomes particularly problematic in high-risk environments where different AI systems may have vastly different reliability profiles, yet users apply uniform trust assumptions across contexts.

XAI theory provides mechanisms for trust calibration through transparency and interpretability [115]. However, explanation quality must be tailored to user expertise and context, as inappropriate explanations can either promote dangerous over-trust or create counterproductive under-trust [115,116]. The theoretical foundation suggests that effective trust calibration requires adaptive explanation mechanisms that respond to user needs and system performance variations.

The cognitive burden of this generalization manifests as inefficient monitoring behaviors following negative experiences, diverting cognitive resources from primary decision-making tasks—a critical concern in high-stakes environments where cognitive load management is essential for safety and effectiveness.

The Capability–Morality Trust Paradox

A fundamental tension emerges in how users perceive AI systems in high-risk contexts. Users consistently perceive AI systems as “capable but amoral”, creating a paradoxical situation where they view AI as technically superior but morally deficient compared to human experts [117]. This moral trust deficit creates ethical concerns about appropriate reliance levels, particularly in domains where moral reasoning and value judgments are integral to decision making.

Despite this perceived moral deficiency, users demonstrate increasing reliance on AI recommendations as they gain experience, suggesting a dangerous disconnect between perceived trustworthiness and actual reliance behaviors. This pattern is especially concerning in high-risk contexts where over-reliance could lead to catastrophic outcomes.

Error Pattern Sensitivity and Risk Assessment

Trust calibration is significantly influenced by error patterns, with critical implications for high-risk decision making. Users demonstrate reduced willingness to delegate complex predictions to AI systems that make rare but large errors [111]. Conversely, continuous small errors in domains where humans possess expertise face stronger penalties than occasional catastrophic failures. This suggests that humans employ sophisticated mental models when assessing AI reliability, but these models may not align optimally with risk management principles in high-stakes contexts.

Performance Paradox in HAIC

Empirical evidence reveals a concerning performance paradox: human–AI combinations often perform worse than the best solo performer (human or AI) but better than humans alone [18]. Task type significantly moderates this relationship, with decision tasks typically showing performance losses while creation tasks demonstrate gains. This finding challenges fundamental assumptions about the benefits of HAIC in high-risk decision-making contexts and highlights the need for careful task-specific implementation strategies.

3.4.2. Challenge 2: Skill Degradation and Human Agency Preservation

Patterns of Human Agency in AI-Mediated Decision Making

The preservation of human competence and agency represents a critical concern in high-risk AI integration. Research identifies six distinct types of human agency in AI-enabled decision making: verification, supervision, cooperation, intervention, rejection, and regulation [118]. Each configuration presents unique risks for skill maintenance and human autonomy preservation.

High control configurations risk over-reliance and the progressive de-skilling of human decision-makers, while high learning capacity configurations create vulnerabilities to automation bias and implementation failures. The challenge lies in maintaining configurations that preserve human competence while leveraging AI capabilities effectively.

Influence Dynamics and Skill Preservation

The temporal dynamics of AI’s influence significantly impact human skill development and maintenance. AI teammates that decrease their influence over time enable humans to improve their performance, while highly influential AI teammates can increase perceived cognitive workload and potentially inhibit skill development [83]. This suggests that adaptive influence management represents a critical design consideration for maintaining human competence in high-risk contexts.