Abstract

This paper presents an intrusion detection system (IDS) leveraging a hybrid machine learning approach aimed at enhancing the security of IoT devices at the edge, specifically for those utilizing the TCP/IP protocol. Recognizing the critical security challenges posed by the rapid expansion of IoT networks, this work evaluates the proposed IDS model with a primary focus on optimizing training time without sacrificing detection accuracy. The paper begins with a comprehensive review of existing hybrid machine learning models for IDS, highlighting both their strengths and limitations. It then provides an overview of the technologies and methodologies implemented in this work, including the utilization of “Botnet IoT Traffic Dataset For Smart Buildings”, a newly released public dataset tailored for IoT threat detection. The hybrid IDS model is explained in detail, followed by a discussion of experimental results that assess the model’s performance in real-world conditions. Furthermore, the proposed IDS is evaluated for its effectiveness in enhancing IoT security within smart building environments, demonstrating how it can address unique challenges such as resource constraints and real-time threat detection at the edge. This work aims to contribute to the development of efficient, reliable, and scalable IDS solutions to protect IoT ecosystems from emerging security threats.

1. Introduction

Internet of Things is an interconnected network of physical devices, sensors, and systems that communicate and exchange data over the Internet, enabling automation, real-time monitoring, and intelligent decision making. These devices, ranging from household items like thermostats to industrial machines and infrastructure, are embedded with sensors and processors that collect data from their environment and either act on it locally or send it to cloud systems for further analysis. IoT enables a seamless integration of physical and digital worlds, allowing devices to make autonomous decisions, optimize processes, and provide insights across several industries [1]. However, IoT also raises significant concerns around security, privacy, and data management. The massive amount of sensitive data collected by IoT devices, combined with potential vulnerabilities in device networks, makes them attractive targets for cyberattacks, and ensuring data protection and user privacy remains a critical challenge for widespread adoption [2].

IoT is reshaping numerous industries by integrating advanced connectivity, data analytics, and automation into traditional systems, driving innovation and improving operational efficiency [3]. It allows business to gain better visibility into their operations, enabling smarter resource allocation and smoother workflows. IoT’s role in improving safety and supporting sustainability is becoming a part of modern industrial practices, helping organizations adapt to changing demands and operate more responsibly. While not a universal solution, IoT serves as a practical tool that enhances existing strategies and drives meaningful progress in today’s connected world.

The manufacturing industry is continuously evolving to meet dynamic market demands, driven by the need for efficiency, flexibility, and the rapid reconfiguration of production processes. As companies struggle to optimize their operations, they encounter significant challenges, particularly in adapting to constant changes in product specifications and production volumes. Inadequate adaptation can lead to bottlenecks, which are points in the production line that impede the overall production process, resulting in delays and financial losses. These bottlenecks often arise from human errors, incorrect configurations, and improper machine maintenance, adding complexity to identifying the root causes of the events. Rodríguez Aguilar et al. [4] propose a framework designed around Industry 4.0 principles, Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT), and Big Data, focusing on real-time data analysis to predict risks and enhance bottleneck detection. By leveraging historical data and continuous optimization across multiple levels of operation, the system aims to improve decision making and mitigate delays in the manufacturing process.

The smart building industry is rapidly evolving, driven by the need for enhanced energy efficiency, occupant comfort, and improved health outcomes in built environments. As urban populations continue to grow, the demand for innovative solutions to optimize building performance has become necessary. Integrating advanced technologies like IoT has emerged as a key strategy to monitor and manage various parameters that influence indoor air quality and overall user satisfaction. El-Leathey, L.-A. et al. [5] presents a novel IoT monitoring system designed to enhance building performance by continuously monitoring indoor environmental parameters linked to occupant comfort and health. The system tracked various meteorological and health indications and while health parameters mostly remained within safe limits, thermal comfort levels were frequently exceeded, highlighting the need for improved natural ventilation and better communication regarding laboratory activities affecting air quality. The findings affirm the reliability of the proposed system for real-time data acquisition and emphasize the integration of such technologies for improved energy efficiency and occupant well being in various building types.

The rise in smart homes has been significantly influenced by the Internet of Things, which seamlessly integrates with a variety of physical devices equipped with sensors and microprocessors to enhance daily living. However, as the number of IoT devices grows, their inadequate security configurations pose substantial threats, particularly concerning their potential use in Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks. To address these challenges, Al-Begain, K. et al. [6] presents a lightweight security model designed to protect IoT devices withing smart home environments from being compromised and utilized as bots in malicious activities.

The integration of IoT technology into agriculture is revolutionizing traditional farming practices by enabling smart farming, which utilizes advanced technologies to optimize crop production while minimizing waste. As the global population grows and food demand rises, leveraging IoT sensors for the real-time monitoring of soil moisture, temperature, and other environmental factors becomes crucial for informed decision making in farming. Elbasi, E. et al. [7] explores the significant impact of machine learning (ML) applications within this context, particularly focusing on how these algorithms enhance crop production and resource efficiency. By analyzing comprehensive datasets from IoT sensors and other sources, farmers can optimize planting, watering, and harvesting schedules, leading to increased yields and reduced costs. The study highlights the current landscape of machine learning in agriculture, identifying both challenges and opportunities while showcasing experimental results that demonstrate the effectiveness of various algorithms.

IoT is revolutionizing healthcare by facilitating remote patient monitoring and personalized treatment solutions. In this context, effective skin-wound healing is influenced by both the exterior and interior environments surrounding a wound, which collectively impact healing outcomes. Traditional studies have largely focused on isolated environmental factors such as moisture, pH, or healing enzymes, neglecting the interaction of various environmental factors, including temperature, humidity, air quality, and pollutants. Sattar, H. et al. [8] introduce an innovative wound care solution that integrates an exterior environment monitoring system with a neural network model, enabling the real-time assessment of wound-healing processes as either continuous or impaired. By using a multi-sensor approach with temperature, humidity, gas, and air-quality sensors, the proposed system provides patients with a smart and intelligent solution for monitoring and managing wound care at home.

IoT is driving significant transformation across various industries, enhancing modernization and operational efficiency while also introducing critical security concerns that must be addressed to protect both businesses and end users. As these technologies continue to evolve, ensuring the trust and safety of all stakeholders becomes crucial for the successful integration of IoT solutions. In this context, leveraging machine learning algorithms presents a promising technology to strengthen security measures, especially in the areas of cybersecurity and AI security within IoT environments [9]. By using advanced analytical techniques, organizations can proactively identify and mitigate potential threats, allowing them to stay one step ahead of cyber attackers. This strategy not only cultivates a more secure IoT ecosystem, but also enables businesses to innovate with confidence, knowing there are robust security measures in place to protect their operations and users [10]. This is particularly critical in smart buildings, where IoT is transforming how buildings are managed and maintained. With IoT devices controlling essential systems such as HVAC, lightning, and security, any vulnerabilities could have severe implications. Therefore, leveraging machine learning in smart-building environments to detect anomalies and respond to threats in real time becomes an essential part of safeguarding the entire infrastructure and ensuring operational resilience.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) plays an important role in strengthening IoT security by addressing the complexity and scale of connected devices, which are often resource constrained and vulnerable to evolving threats. Traditional security methods struggle to cope with the vast data generated by IoT networks, making AI’s ability to process and analyze large volumes of data in real time invaluable [11]. ML algorithms enable AI to detect anomalies by identifying unusual patterns in device behavior or network traffic, flagging potential threats like malware, data filtration, or unauthorized access. Unlike static rule-based systems, AI continuously learns from new data and past security incidents, allowing it to detect emerging threats, including zero-day attacks. Moreover, AI enhances IoT security by optimizing encryption and authentication methods, adjusting them based on device capabilities, and implementing advanced techniques like biometric authentication to ensure only authorized user access devices [12]. In tandem, AI-driven threat detection gathers data from various sources, predicting vulnerabilities and automating responses, such as isolating compromised devices or patching security flaws in real time. AI’s ability to orchestrate security policies across diverse IoT environments, including edge devices, ensures consistent protection while reducing intelligent defenses [9].

Hybrid machine learning approaches refers to the integration of multiple techniques, combining different machine learning algorithms with data manipulation methods such as feature extraction, normalization, and dimensionality reduction to improve performance and accuracy. By leveraging diverse models and preprocessing strategies, hybrid approaches enhance the data quality and adaptability of machine learning systems [13]. In security, particularly for IoT devices on the edge, hybrid models are highly effective because they enable real-time threat detection and response despite limited computational resources. These systems can first preprocess data to filter noise or enhance relevant features, then apply a combination of algorithms like anomaly detection and classification to detect evolving cyber threats [14]. This makes hybrid machine learning ideal for securing IoT environments, where both data complexity and the need for fast, adaptive responses are critical.

2. Objectives

This paper proposes an intrusion detection system built using a hybrid machine learning approach for enhancing IoT security at the edge for IoT devices that use TCP/IP protocol for communication, focusing on evaluating the performance of the final model, particularly in terms of training time. The paper includes a review of existing hybrid machine learning approaches, an overview of the technologies used, a detailed presentation of a newly available public dataset for IoT threat detection, an explanation of the hybrid system, and a discussion of the experimental results. Additionally, the paper will address how the solution can reinforce the security of IoT systems in smart buildings.

3. Related Work

Over the past few years, hybrid machine learning methods have gained significant adoption as an effective technique for resolving complex data driver challenges. By combining multiple machine learning algorithms, hybrid methods aim to leverage the strengths of individual models while mitigating their weaknesses [15]. These approaches often integrate supervised and unsupervised learning, deep learning, and traditional machine learning techniques, creating systems that are more robust and accurate than any single model. The flexibility of hybrid methods makes them particularly useful in diverse domains such as financial forecasting, anomaly detection, intrusion detection systems, or healthcare analytics, where data patterns can be highly nonlinear, noisy, and multidimensional. The fusion of models not only enhances predictive accuracy, but also helps in handling imbalanced datasets, reducing overfitting, and improving generalization to new data.

A growing number of studies have examined various hybrid approaches, showcasing their superior performance across multiple applications. From combining ensemble techniques with neural networks to integrating clustering algorithms with deep learning architectures, researchers have developed innovative algorithms to solve specific challenges. Hybrid models often involve stacking or cascading machine learning algorithms, where the output of one model serves as the input to another, enhancing the overall system predictive power. The use of feature-extraction techniques such as principal component analysis (PCA), autoencoders, or convolutional neural networks (CNNs) in conjunction with traditional classifiers like support vector machines (SVMs) or random forests (RFs) has demonstrated promising results. This chapter reviews developments in hybrid machine learning, categorizing methods based on their underlying techniques and discussing their applications in various domains. While numerous articles were considered and are presented in Table 1, only some of the most relevant and impactful studies for this topic will be highlighted in detail in the text. This selective approach ensures a focused discussion on the most important advancements in the field.

Table 1.

Comparison of hybrid machine learning methods.

Paper [17] focuses on predicting harmful algal blooms (HAB) that impact mollusk farming by using hybrid machine learning models. Specifically, it compares models such as Neural-Network-Adding Bootstrap (BAGNET) and Discriminative Nearest Neighbor Classification (SVM-KNN) for estimating whether mollusk meat toxicity is above legal limits, which influences production closures. The use of hybrid models to handle complex, irregular environmental data aligns with a broader trend seen in other fields, such as drilling prediction [20] and intrusion detection [28]. Similarly to the other studies, this research shows that hybrid techniques outperform single-model approaches in accuracy and generalization, especially in complex and fluctuating environments.

Study [18] enhances Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) by incorporating state machines to simulate memory for handling sequential data, such as music notation. By using a state machine, the ANN can transition between states to better manage tasks involving sequence-based inputs. This approach mirrors the augmentation of machine learning models in the HAB study [17], where a hybrid model improves predictions in dynamic environments. Both papers demonstrate the advantage of combining machine learning techniques to adapt to more complex data structures. Moreover, the focus on enhancing ANNs ties into other studies that explore neural networks in hybrid models, such as software defect detection in paper [22] and intrusion detection in paper [28]

In study [19], machine learning is applied to predict student performance, particularly in mathematics, using a hybrid approach. Principal component analysis (PCA) is combined with classification algorithms such as random forest, support vector machine, and Naïve Bayes to enhance prediction accuracy. The hybrid model addresses misclassification issues, similar to HAB prediction model from paper [17] and the cross-project software detection from paper [22]. In all cases, hybrid models are used to improve classification outcomes in datasets with complex, interrelated variables. This connection shows the flexibility of hybrid machine learning techniques across fields as diverse as education and environmental monitoring.

Paper [20] tackles the challenge of predicting rate of penetration in drilling operations, a critical factor in optimizing costs. A hybrid model combining empirical methods and machine learning, based on the similarity of new input data, outperforms individual models in robustness and accuracy. This method of combining empirical models with machine learning mirrors the hybrid approaches used in the HAB prediction study in paper [17] and the student performance prediction in paper [19], where complex environments or datasets required multiple techniques for better results. The shared use of hybrid models underscores the versatility of this approach across diverse fields, from resource management to education.

Study [22] explores defect prediction across software projects using a hybrid model that combines ensemble methods such as support vector machines (SVMs), random forest (RF), and extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost, XGB) with neural networks. The model addresses the challenge of predicting software defects in datasets from different projects, and the ensemble approach outperforms single-method models. This mirrors the cross-context prediction goals seen in the HAB research in paper [17] and the drilling prediction in paper [20], where hybrid models are used to generalize across varied conditions. The ability of these models to adapt to different projects or environments conditions emphasizes the shared theme of using hybrid models for broad applicability and improved accuracy.

In the field of network security, paper [28] presents a hybrid model for intrusion detection, combining XGBoost and deep learning methods such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM). The hybrid model addresses the limitations of traditional intrusion detection systems by increasing detection accuracy and reducing false positives. This study shares common ground with papers like rate of penetration prediction in paper [20] and cross-project software defect detection in paper [22], where hybrid approaches are necessary to handle complex, unpredictable data. Like those papers, the intrusion detection model uses a combination of different techniques to improve performance in environments where traditional models fall short.

Study [29] develops a deep learning anomaly detection system for IoT environments, utilizing a denoising autoencoder to capture robust features that withstand noisy, heterogeneous environments. The approach resembles the hybrid intrusion detection model from paper [28] where deep learning is combined with other techniques to improve detection performance in complex network systems. Additionally, the focus on handling diverse IoT data links back to the adaptive techniques used in the cross-project software defect prediction from paper [22] and drilling prediction from paper [20], both of which aim to generalize across diverse datasets and contexts.

Paper [30], a novel hybrid model using CNN, LSTM and Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs) is applied to intrusion detection in electric-vehicle charging stations (EVCS). The ensemble model achieves high accuracy across both binary and multi-class classifications. The combination of deep learning methods (CNN, LSTM) mirrors other intrusion detection efforts like in paper [28], as well as the anomaly detection system for IoT environments from paper [29], demonstrating that hybrid models are essential for improving cybersecurity across a variety of network-based systems. The success of ensemble techniques also echoes the use of similar hybrid models in the drilling and software defect prediction studies [20,22].

Study [31] develops a hybrid intrusion detection system (IDS) for the Industrial IoT, using a combination of CNN and LSTM models. The model is tested on the Edge-IIoTset dataset and achieves high performance in both binary and multi class classifications. This research shares key similarities with the IDS for electric-vehicle charging stations from paper [31] and other intrusion detection models from paper [28], as all these studies use hybrid deep learning techniques to improve security in complex networked environments. The application of CNN and LSTM is a common thread across papers dealing with network intrusion detection, highlighting the strength of deep learning methods in anomaly detection.

Paper [33] focuses on intrusion detection in IoT systems using a hybrid model that combines CNN for feature extraction and XGBoost for classification. By applying principal component analysis (PCA) to reduce redundancy in the dataset, the model improves the accuracy of detecting network attacks. The use of PCA for dimensionality reduction links back to the student performance prediction model form paper [19], where PCA was similarly applied to improve classification. This connection between fields like education and cybersecurity underscores the universal applicability of machine learning techniques such as CNN and XGBoost, which are also seen in earlier intrusion detection studies from papers [28,30].

Study [36] examined the performance of multiple machine learning models for detecting intrusions in IoT network through a Python-based implementation. The research employed the BoT-IoT dataset, which is publicly available from the University of New South Wales Canberra and features both botnet and normal traffic data. Due to limitations in computational resources, the dataset was reduced to a 5% subset and split into 80% for training and 20% for testing. This approach provided balance between data availability and processing feasibility, resulting in a training set with 2.934.817 records and a testing set with 733.706 records. Preprocessing steps narrowed down the dataset to ten critical features relevant for attack classification. The researchers chose four algorithms (random forest, decision trees, Naïve Bayes and extreme gradient boost) to build the models and compare their predictive capabilities across different types of attacks, including various subcategories.

Not only across these papers, but analyzing all resources from Table 1, there is a clear emphasis on hybrid and ensemble machine learning models to address complex, diverse datasets, and achieve higher accuracy in predictions and classifications. Each paper draws on a combination of deep learning techniques (CNN, LSTM), traditional machine learning models (SVM, RF), or feature-extraction methods (PCA, denoising autoencoders) to solve domain-specific problems, from environmental monitoring to software defect prediction and cybersecurity in IoT and IIoT systems. Looking forward, the next chapter will contain a theoretical part of the technologies that will be used for the proposed hybrid machine learning intrusion detection system for IoT devices that use TCP/IP protocol for communication.

4. Methodology

The conducted study contains several stages, including a review of previously analyzed literature presented in the previous chapter, a detailed methodology for the tested components used in intrusion detection, an explanation of the test results, and the rationale behind selecting specific technologies for the hybrid machine learning approach.

To evaluate the models, a variety of metrics were used, such as precision, accuracy, sensitivity, and F1 score, each offering a distinct view of the model’s performance. Precision assessed the model’s ability to correctly identify true positives out of all predicted positives, while accuracy measured the proportion of correct predictions overall. Sensitivity, or recall, focused on the decision rate of true positive cases, ensuring minimal missed intrusions. The F1 score combined precision and recall for a more comprehensive evaluation. Among the algorithms tested, XGB outperformed the others in all metrics, indicating its effectiveness for predicting the occurrence and specific nature of various network attacks. K-fold cross-validation was used to verify these results, further demonstrating the reliability of XGB intrusion detection within IoT environments using TCP/IP communication protocols.

Incorporating regularization terms in its cost function, XGB uses both Lasso (L1) and Ridge (L2) techniques to penalize complexity in the model. The use of L1 regularization encourages sparsity, effectively reducing the weight of less important features, while L2 regularization helps to balance large weight values across the model, preventing overfitting. By doing so, XGB enhances the generalizability of the model, reducing the risk of fitting the training data too closely. This is particularly important in the context of intrusion detection, where datasets often contain complex patterns that may not extend well to unseen data. Through this combination of regularization techniques, the model becomes more adaptable to new data, improving the robustness and stability of predictions [37].

The objective function used by XGBoost combines both a loss term and regularization terms to strike a balance between model accuracy and complexity. The loss term quantifies the error between actual and predicted values, while the regularization components impose penalties based on the model’s complexity, thereby discouraging overfitting. For a regression problem, this function typically takes the following form:

where calculates the prediction error, and integrates both L1 and L2 regularization terms to manage the depth and intricacy of the trees in the model. This regularization prevents models from becoming overly complex, thus maintaining generalization capability.

In training individual trees, XGB’s approach involves optimizing a combination of gain (the improvement from a potential split) and regularization parameters at each node. The optimization objective for a given tree is defined as:

Here, and are the sums of gradients and Hessians at node j, respectively, indicating the need for adjustments in predictions. The parameters and control the level of regularization applied, thus influencing the balance between fitting the data accurately and maintaining model simplicity. This framework enables XGBoost to be flexible across different machine learning tasks, including classification, ranking, and regressing, making it suitable for diverse application areas.

This study utilizes XGBoost as a part of the hybrid machine learning system to assess platform performance in detecting intrusions in IoT networks. Its integration of regularization techniques and versatile performance across various metrics demonstrate XGBoost’s capability to address the unique challenges posed by IoT security.

In addition to XGBoost, this paper will also discuss the following technologies: Argus—a network monitoring tool that provides comprehensive traffic analysis, PCA—a dimensionality reduction technique, Orange Pi—a low cost, open-source single board computer, and MQTT—a lightweight messaging protocol widely used in IoT applications.

Argus (Audit Record Generation and Utilization System) [38] is an open-source versatile network monitoring tool used for tracking and analyzing network traffic. It is particularly useful in intrusion detection, as it provides detailed records of network connections, allowing for the identification of suspicious or anomalous behaviors. Argus operates by capturing packets at the network layer and converting them into flow records, which contain metadata such as connection duration, packet count, byte count, and protocol used. This metadata can be used to create a feature set for intrusion detection algorithms, enabling the identification of patterns that may indicate security breaches.

Mathematically, the flow records generated by Argus can be represented as vectors in an n-dimensional space, where each dimension corresponds to a specific feature (number of packets, average packet size, protocol, etc.). For example, a flow vector can be expressed as:

In this context, represents a particular feature of the network flow. Machine learning algorithms, such as XGBoost, can be used to classify these vectors as either normal or anomalous based on the feature values. Argus’ detailed flow records enable the development of robust feature sets, which improves the accuracy of intrusion detection models. Regular updates to the flow records also allow for real-time monitoring, which is crucial in dynamic IoT environments.

Principal component analysis (PCA) [39] is a statistical technique used to reduce the dimensionality of data while retaining its most important features. In the context of intrusion detection in IoT networks, PCA is used to simplify the data by transforming it into a new coordinate system, where the greatest variance by any projection of the data lies on the first coordinate (known as the first principal component), the second greatest variance on the second coordinate, and so forth. This transformation can be mathematically represented by:

represents the original data matrix, is the matrix of eigenvectors (principal components), and is the transformed data in the new principal component space. The eigenvectors are computed from the covariance matrix of the original data:

Here, represents each data point, is the mean of the data points, and is the total number of data points. The eigenvectors corresponding to the largest eigenvalues are selected as the principal components, reducing the original data’s dimensionality while retaining the features with the most variance.

PCA helps in intrusion detection by focusing on the most significant data characteristics and filtering out noise, thereby improving the performance of classification algorithms like XGBoost in distinguishing between normal and botnet traffic patterns.

Orange Pi [40] is an open-source single-board computer similar to the popular Raspberry Pi, but with different hardware capabilities. It provides a cost-effective platform for deploying IoT applications, as it supports a variety of operating systems, including Linux and Android, and has interfaces for connecting sensors, cameras, and other peripherals commonly used in IoT environments. The hardware architecture of Orange Pi typically includes a multi-core ARM processor, memory, storage options, and general-purpose input/output pins, making it a suitable platform for prototyping and testing IoT solutions.

From a theoretical standpoint, Orange Pi can be used to simulate different network conditions and device behaviors in an IoT environment. It allows researchers to deploy multiple instances running various communication protocols and algorithms, such as MQTT or intrusion detection models based on XGBoost, to create a testbed for performance evaluation. The data collected from these simulations can be used to evaluate the scalability and robustness of IoT security solutions.

Orange Pi’s ability to run on edge computing tasks is particularly relevant in IoT security, where processing data locally on the device can reduce latency and bandwidth usage. For example, data aggregation and initial intrusion detection can be performed directly on an Orange Pi before sending critical alerts to a central server for further analysis. This distributed approach to computing aligns with the concepts of fog computing in IoT, which involves extending cloud services to the edge of the network.

MQTT (Message-Queuing Telemetry Transport) [41] is a lightweight publish/subscribe messaging protocol designed for constrained devices and low-bandwidth, high-latency networks. It is widely used in IoT applications due to its simplicity and efficiency in data transmission. In MQTT, communication is established through a broker that manages the distribution of messages between clients. The clients can either publish data to a topic or subscribe to a topic to receive updates. The broker ensures that messages published on a specific topic are delivered to all subscribers of that topic.

The theoretical foundation of MQTT is based on the publish/subscribe pattern, where the broker acts as an intermediary to decouple message producers from consumers. The quality of service (QoS) levels in MQTT, defined as QoS 0 (at most once), QoS 1 (at least once), and QoS 2 (exactly once), determine the reliability of message delivery. The mathematical model for message delivery in MQTT can be expressed through probability measures:

- QoS 0 (at most once)—the probability of a message being delivered is defined by the following formula, where there is no retransmission guarantee.

- 2.

- QoS 1 (at least once)—the probability of a message being delivered at least once is represented below, assuming acknowledgement and possible retransmission occur.

- 3.

- QoS 2 (Exactly once)—the probability of duplicate message is minimized by a four-step handshake process, ensuring message is delivered only once.

MQTT’s lightweight nature makes it ideal for IoT applications that involve sensors and devices with limited processing power. It supports various security measures, including Transport Layer Security (TLS) for encrypted communications and authentication mechanisms for validating client identities. These features make MQTT suitable for building secure communication frameworks in smart buildings, where multiple devices must exchange information reliably and efficiently.

The scope of the paper is to propose a hybrid machine learning approach in order to efficiently and promptly train a classifier for an intrusion detection system that will operate on the Orange Pi 5 board. The classifier will use data from a newly created dataset that will be described in the next section of the paper, which contains normal data, and botnet data simulated in a real environment.

After training the XGBoost classifier, the following metrics will be used to evaluate the accuracy of the machine learning model based on the classification report: accuracy, precision, sensitivity, and F1 score. Additionally, the performance of all models will be assessed using the k-fold cross-validation technique. Besides the quality metrics, the platform metrics will also be assessed to understand which model had the best training metrics, such as script execution time, model training time, RAM utilization, and CPU utilization.

5. Botnet IoT Traffic Dataset for Smart Buildings

The Botnet IoT Traffic Dataset For Smart Buildings (BotIoT-SB) is a comprehensive, publicly available dataset [42] designed to support research and development in intrusion detection, especially in IoT environments in smart buildings. The dataset captures both normal and attack traffic, providing a unique blend of MQTT and HTTP traffic types. Data were collected from three IoT devices connected to an Orange Pi 5 network gateway, with each device communicating via distinct IPs using TCP/IP communication. Among these devices, one used the MQTT protocol to communicate with a broker integrated into the gateway, while the others generated standard IP traffic. The dataset includes a set of attack types targeting the gateway such as DoS, port scanning, and OS fingerprinting, as well as those targeting the MQTT broker such as brute force, DoS, publish, and subscribe, performed using various specialized tools. These attacks are simulated using a Kali Linux machine on the same network as the gateway.

Each type of attack in the dataset is recorded for an hour, offering a manageable yet representative sample of malicious behavior, enabling the examination of specific attack signatures and patterns. The dataset was captured using tcpdump and later analyzed with the Argus tool to highlight key features, making it especially valuable for researchers aiming to enhance machine learning models for anomaly detection. The analyzed data were labeled and converted to CSV files to facilitate its use in machine learning models.

Table 2 contains the IoT setup involved, which contains a gateway with an MQTT broker that handled the MQTT communications of device 1, while devices 2 and 3 communicated via traditional HTTP and TCP/IP protocols. This setup reflects a real implementation in real-world scenarios in smart buildings where IoT devices interact using varied protocols, increasing the complexity of intrusion detection.

Table 2.

Device configuration.

The dataset contains several attack types described in Table 3, each simulating a specific threat. Each attack was performed for multiple hours, with only one complete hour per attack retained in the dataset. This was done to ensure focused, high-quality data for each attack scenario.

Table 3.

Description of attacks.

Table 3 summarizes the commands and tools used to conduct attacks in the dataset, demonstrating a realistic simulation of threats to smart-building IoT infrastructure.

Argus, a network monitoring tool, was used to process packets captured by tcpdump and extract key features useful for intrusion detection. The tool not only parsed raw network traffic but also performed initial data cleaning by filtering out incomplete, malformed, or irrelevant packets to ensure the dataset is both accurate and meaningful for analysis. To further curate the data, Argus removed duplicate entries and missing values were handled to maintain consistency. Based on the criteria set in reference [36], Table 4 contains the ten best features that were determined as most significant for assessing network security. These features facilitate accurate intrusion detection by characterizing both typical and atypical traffic patterns. In smart-building networks, where both MQTT and regular traffic coexist, these attributes are essential for identifying irregularities that may signify an attack. Together, these features provide a comprehensive perspective on network traffic. By focusing on attributes like connection frequency, duration, and state, security systems can better recognize irregularities that may suggest intrusions such as brute-force attempts, DoS attacks, and unauthorized access to MQTT brokers.

Table 4.

Feature description.

The dataset is structured hierarchically into three levels of classification: type, class and subclass. Type distinguishes between two main categories of network traffic: attack and normal. The class level provides a more specific categorization, dividing traffic into normal activity and MQTT related activity, which includes both normal and malicious operations. Finally, the most granular level, subclass, identifies specific attack types within the dataset. These include DoS, port scanning, OS fingerprinting, and various MQTT specific attacks such as MQTT brute force, MQTT DoS, MQTT publish attack, and MQTT subscribe attack. This hierarchical structure enables a detailed analysis of network traffic and allows models to detect and classify attacks with precision, ranging from general distinctions to specific behaviors.

The Botnet IoT Traffic Dataset For Smart Buildings is valuable due to its realistic representation of normal and attack traffic, covering both MQTT and traditional IP protocols. With attacks meticulously carried out using specialized tools and commands, and traffic analyzed to highlight critical intrusion detection features, this dataset serves as a crucial resource for researchers seeking to develop robust intrusion detection systems. The public availability of dataset [43] offers a needed benchmark for evaluating intrusion detection models, particularly in the context of smart-building IoT environments where complex protocols coexist.

6. Implementation

This chapter provides a detailed guide for implementing a Python script on an Orange Pi 5 board to evaluate the consistency and performance of the hybrid machine learning protocol. This script leverages PCA for dimensionality reduction, performs training and testing using XGBoost, and saves key metrics to a CSV file. The aim is to assess how various levels of PCA impact the model’s performance across multiple iterations.

The pseudocode in Table 5 outlines the steps to implement the script, which iterates through multiple PCA levels and evaluates the XGBoost model consistency over 100 iterations.

Table 5.

Pseudocode for hybrid machine learning protocol.

The implementation relies on four main components that work together to assess the performance of the XGBoost model at various PCA levels over multiple iterations.

First, data loading and preprocessing ensures the dataset is correctly loaded and organized. This involves separating the feature columns and label columns, then applying label encoding. Preprocessing is completed with data splitting and scaling. The data are split into an 80% training set and a 20% testing set. This method was chosen over k-fold cross-validation because, given the large size of the dataset and the focus on evaluating overall model performance, an 80/20 split provides a clear separation between training and testing data, reducing computational overhead associated with k-fold cross-validation. This approach is particularly effective for intrusion detection systems, where it is crucial to have a reliable test set that simulates unseen traffic patterns. The next step is feature scaling with StandardScaler, standardizing each feature to have a mean of zero and a variance of one. This scaling step is crucial as it improves the model’s ability to learn effectively, especially for algorithms sensitive to feature magnitudes.

Second, dimensionality reduction with PCA is performed to reduce the number of features while retaining a chosen level of variance (100%—PCA 100, 95%—PCA 95, 90%—PCA90, 80%—PCA 80, 70%, PCA 70). This step mitigates the curse of dimensionality, helping the model focus on the most informative features and reducing computational load on the Orange Pi 5 board, which proves to be an asset in resource-limited environments. By applying PCA, the model can potentially achieve similar predictive accuracy with fewer dimensions, thereby improving both processing time and memory efficiency.

Third, model training and evaluation utilizes XGBoost, a high-performance gradient boosting algorithm known for handling unbalanced data and achieving high accuracy with relatively low computational cost. The model is trained on the PCA-reduced training set in each iteration and evaluated on the test set using metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score. These metrics provide a comprehensive assessment of the model performance by measuring both predictive power and the balance between precision and recall, which is essential for models deployed in real-world applications.

Finally, file management involves logging results from each iteration and PCA level to a CSV file. This file contains recorded performance metrics, iteration numbers, and PCA percentage, allowing for easy tracking and analysis. With this setup, it enables a comprehensive way to compare the consistency of XGBoost performance across iterations and observe how dimensionality reduction impacts the model. This final step ensures transparency and reproducibility, providing a dataset that can be analyzed and to fine tune model parameters or make further optimizations.

The results in the figures that will be presented in the next section are intended to illustrate the variation in performance metrics over 100 iterations and PCA variation in the model training and evaluation process. These figures provide a clear representation of the stability and consistency of the models across multiple runs, as explained in Table 6.

Table 6.

Experiment description.

In addition to analyzing the hybrid machine learning model, four classical machine learning algorithms (random forests—RFs, Naïve Bayes—NB, decision trees—DTs, and XGBoost—XGB) were trained to serve as benchmarks for performance comparison. These models were applied without leveraging the hybrid approach, relying on the curated dataset for their predictions. Each algorithm was applied to ensure a fair comparison across metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score. This analysis provided insights into the capabilities of the hybrid model by highlighting its ability to integrate diverse learning paradigms, while also demonstrating the baseline effectiveness of classical methods operating with only data curation.

Adding to the newly created dataset, the same methodology will be applied to the BoT-IoT dataset [44], which is publicly available from the University of New South Wales Canberra and includes both botnet and normal traffic data. Due to computational resource constraints, the dataset was reduced to a 5% subset, which was subsequently split into 80% for training and 20% for testing. This approach ensured a balance between data availability and processing feasibility, resulting in a training set comprising 2,934,817 records and a testing set containing 733,706 records. Preprocessing steps were conducted to narrow down the dataset to the same ten critical features that are most relevant for attack classification from Table 4.

The next chapter will transition to analyzing the results of this experiment, examining the recorded metrics to understand the effects of PCA on XGBoost performance. The analysis will provide insight into the optimal PCA level for balancing efficiency and accuracy on resource limited devices, giving a clearer picture of the model suitability and stability for deployment in real-world smart-building scenarios.

7. Results

The Results section is structured to provide a comprehensive analysis of the experimental findings. It is divided into two subsections: one dedicated to the newly created dataset and another focusing on the BoT-IoT dataset. The first subsection presents a detailed evaluation of the system’s performance using the newly created dataset, highlighting the metrics and efficiency achieved in this controlled environment. In the second subsection, a similar analysis is performed using the BoT-IoT dataset to validate the system’s applicability across different datasets. This includes comparisons and complementary insights, maintaining consistency in the evaluation metrics and methodologies. Additionally, the section concludes with an integrated discussion summarizing the observations from both subsections, offering an assessment of the system’s strengths and limitations.

7.1. Botnet IoT Traffic Dataset for Smart Buildings - BotIoT-SB

This analysis examines the performance of an XGBoost-based intrusion detection system enhanced with PCA dimensionality reduction. Each chart offers insights into how PCA impacts different performance metrics, providing a holistic overview of resource efficiency, model accuracy, and suitability for deployment in IoT smart-building gateways.

The performance comparison from Table 7 highlights that while all four algorithms perform exceptionally well at the broad type level, there are notable differences in their effectiveness as the granularity of classification increases.

Table 7.

BotIoT-SB comparison of rudimentary ML algorithms’ performance.

At the subclass level, XGBoost consistently outperforms the other models with the highest precision, recall, and F1 scores. This indicates its superior ability to handle detailed distinctions within the dataset, which is critical in the context of network intrusion detection systems. Intrusions often involve subtle and complex patterns that require high precision and recall at the most granular levels to avoid false positives and negatives. While RF and DT also demonstrate strong performance, XGBoost’s robustness and efficiency in handling nuanced distinctions make it the optimal choice for integration into a hybrid approach for network IDS, ensuring both accuracy and reliability in detecting diverse intrusion types.

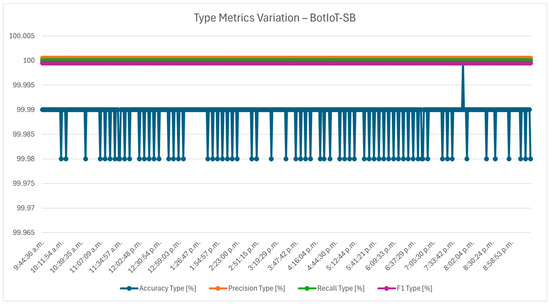

The type metrics variation from Figure 1 focuses on the intrusion detection system’s ability to classify traffic into general types, an essential feature for an IoT gateway, where distinguishing normally from potential malicious traffic is a primary consideration. The metrics presented, accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score, show minimal deviation across PCA levels, with accuracy consistently near 99.99% for all configurations from PCA 100% to PCA 70%. This indicates that PCA dimensionality reduction does not degrade the model’s capability to distinguish traffic types. Furthermore, precision and recall are both high and consistent, reflecting the model’s strong performance in capturing accurate predictions while minimizing false alarms. The stability of these metrics across PCA levels suggests that even aggressive dimensionality reduction retains the features most critical for traffic-type classification. This reliability is crucial in smart-building networks where the accurate identification of traffic types helps the IDS to quickly detect and manage potential threats.

Figure 1.

Type metrics variation—BotIoT-SB.

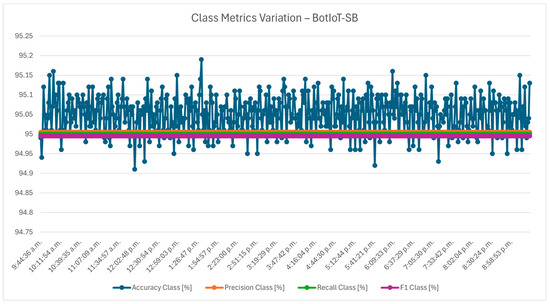

The class metrics variation chart from Figure 2 shifts focus from general traffic types to more specific traffic classes, providing a finer lens on the IDS classification accuracy. In this context, accuracy remains high across PCA configurations, with minimal fluctuations indicating that dimensionality reduction may modestly impact the model’s sensitivity to certain traffic classes. However, the other metrics remain the same across all PCA levels, showing that the model’s core classification reliability remains consistent despite the reduced feature set. This steadiness suggests that the IDS maintains its balance between capturing true positives and minimizing false positives, even as dimensions decrease. For an IoT-enabled smart buildings, these results prove that a dimensionally reduced dataset offers an effective balance, preserving class detection reliability while reducing computational load, which will be proved in the following discussions.

Figure 2.

Class metrics variation—BotIoT-SB.

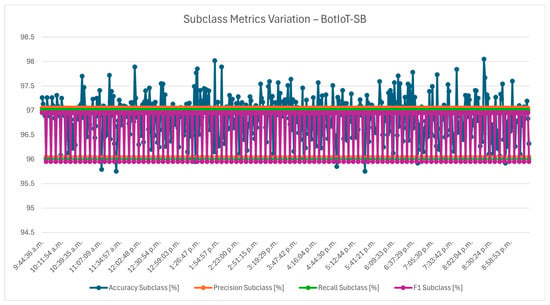

The subclass metrics variation chart from Figure 3 dives deeper into the IDS performance, examining its ability to identify specific traffic subclasses within the IoT network. Given the complexity of detecting subclass differences, metrics at this level can be more sensitive to dimensionality reduction. The chart reveals that while the overall reliability remains strong, it varies slightly with dimensionality reduction. The F1 score remains robust but shows a slight decrease from 97% to 96% as dimensions are further reduced. These results show that PCA 70 might sacrifice a bit of differentiation power, particularly important for detecting nuanced threats. In the context of smart-building cybersecurity, this makes the PCA 70 a good candidate, balancing the need for computational efficiency with the critical requirement to capture detailed traffic subclass patterns for robust threat detection.

Figure 3.

Subclass metrics variation—BotIoT-SB.

Table 8 presents the confidence intervals for the key performance metrics of the hybrid model. For each metric, the upper and lower bounds of the interval are specified, indicating the range within which the true performance value is likely to lie with a high level of confidence. For all metrics and network classifications, the confidence intervals exhibit extremely narrow differences, reflecting high reliability of the models at this broad level. These intervals highlight the models’ consistent performance across different levels of granularity, with slight variability as the classification task becomes more detailed.

Table 8.

Confidence intervals—BotIoT-SB.

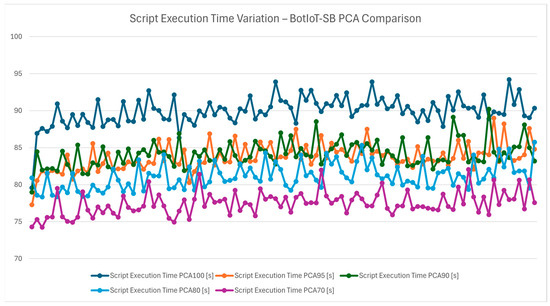

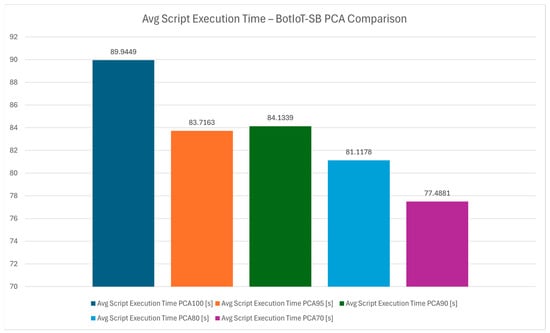

The script execution time variation chart from Figure 4 provides insights into how PCA impacts the total time taken to execute the IDS script across configurations. A trend is visible, as the script execution time decreases as the retained variance in PCA reduces. PCA 70 shows the shortest execution time, demonstrating that reducing dimensions leads to more efficient processing. The reduction in execution time is crucial for real-time IDS deployments on devices like Orange Pi 5, where the retraining of the model can be treated by multiple teams to create a more performant ML model and can improve the system response to potential threats. PCA 70 offers significant reductions and makes it an attractive choice for IoT devices with limited processing power in smart-building environments.

Figure 4.

Script execution time variation—BotIoT-SB PCA comparison.

The chart in Figure 5 provides an aggregate view of the average execution time across PCA levels, further confirming PCA 70 as the most efficient configuration. By averaging execution times, it removes outliers, offering a clearer picture of time savings with reduced variance retention. The average execution time for PCA 70 is notably lower than the other configurations, reinforcing that PCA 70 is suitable for time-sensitive applications in IoT cybersecurity.

Figure 5.

Average script execution time—BotIoT-SB PCA comparison.

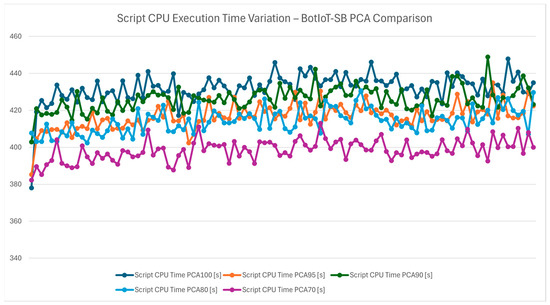

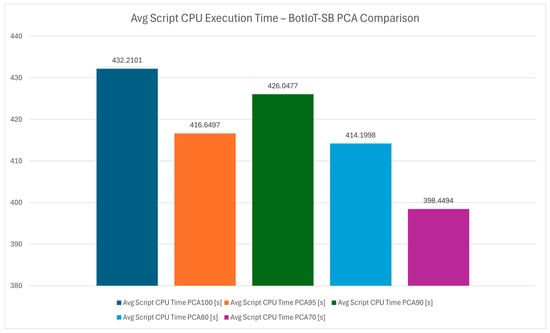

The script CPU execution time variation chart from Figure 6 explores how PCA affects CPU time, a crucial metric for understanding the computational load of the IDS. By increasing the dimensions of the dataset, the CPU demands are also lowered when training the ML model. For IoT gateways in smart buildings, where CPU resources are limited, minimizing CPU usage extends device lifespan and improves responsiveness, allowing the IDS to function more sustainably. Lower CPU demands at PCA 70 indicate that this configuration is optimized for maintaining low computational demand while having similar detection capabilities.

Figure 6.

Script CPU execution time variation—BotIoT-SB PCA comparison.

The average script CPU execution time chart from Figure 7 averages the CPU time usage across PCA levels, offering a smoothed perspective on CPU demand. PCA 70 stands out as the most efficient CPU configuration, showing its potential to reduce processing overhead while delivering effective IDS performance.

Figure 7.

Average script CPU execution time—BotIoT-SB PCA comparison.

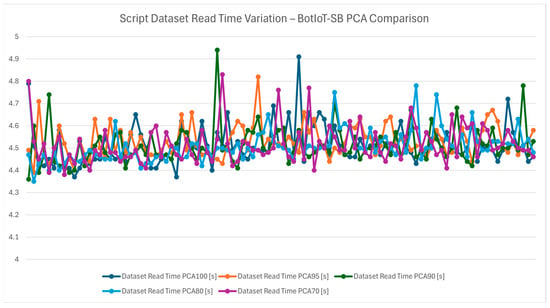

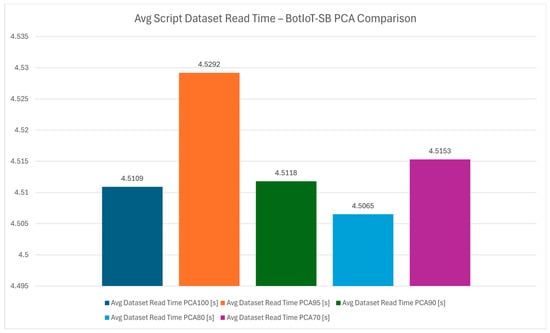

The script dataset read-time variation chart from Figure 8 examines the impact taken to read the dataset. However, since the dataset is first being read and the computation is applied after the fact, the read times are relatively consistent across all PCA configurations indicating that dimensionality reduction influences the processing time rather than data loading. Figure 9 shows the average reading times of the dataset which reinforces the fact that PCA benefits are more prominent during data processing.

Figure 8.

Script dataset read time variation—BotIoT-SB PCA comparison.

Figure 9.

Average script dataset read time—BotIoT-SB PCA comparison.

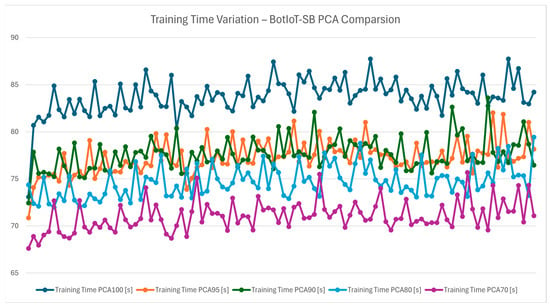

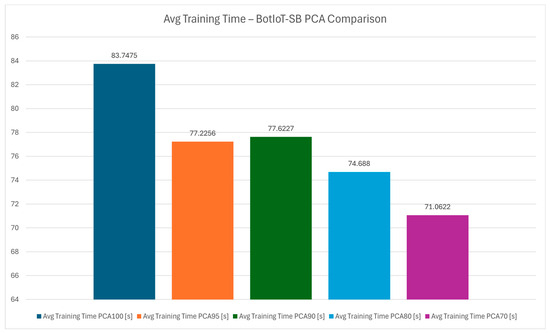

The training time variation chart from Figure 10 highlights how PCA impacts the time required to train the XGBoost model. As expected, training time decreases with lower PCA variance, with PCA 70 showing the shortest training times. This reduction in training time is beneficial for IDS systems that need to adapt quickly to new threats by training the model. For an IoT gateway managing various devices, quicker retraining times mean faster adaptation, enhancing the IDS responsiveness to evolving cybersecurity threats. Figure 11 provides an average view of training times across PCA levels, confirming that PCA 70 is the most efficient for training. By minimizing training time, this configuration allows the IDS to be rapidly redeployed, a significant advantage in IoT environments where threat landscapes can change rapidly.

Figure 10.

Training time variation—BotIoT-SB PCA comparison.

Figure 11.

Average training time—BotIoT-SB PCA comparison.

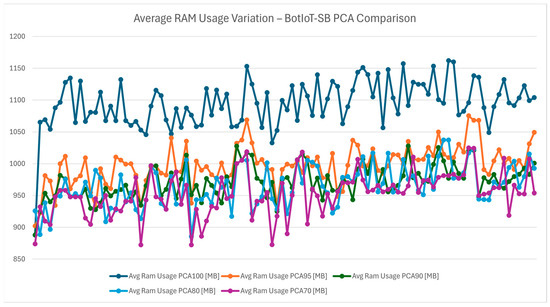

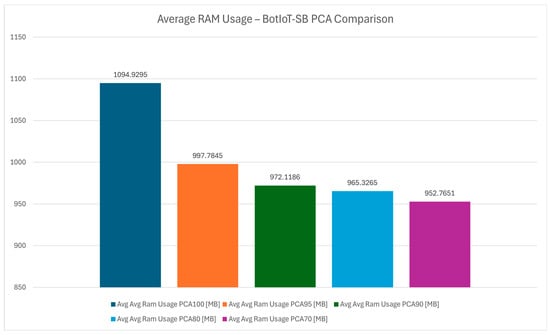

The average RAM usage variation chart from Figure 12 examines how PCA affects memory consumption. Reducing the dimensions naturally decreases RAM usage, with PCA 70 demonstrating the lowest average memory demand, reinforced by Figure 13 For resource-constrained IoT devices, conserving RAM is crucial to avoid overloads and maintain stable operation. Lower RAM usage ensures that the IDS can function without excessive memory strain, allowing it to scale effectively in smart-building environments.

Figure 12.

Average RAM usage variation—BotIoT-SB PCA comparison.

Figure 13.

Average RAM usage—BotIoT-SB PCA comparison.

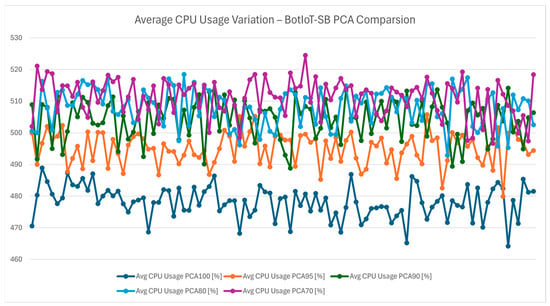

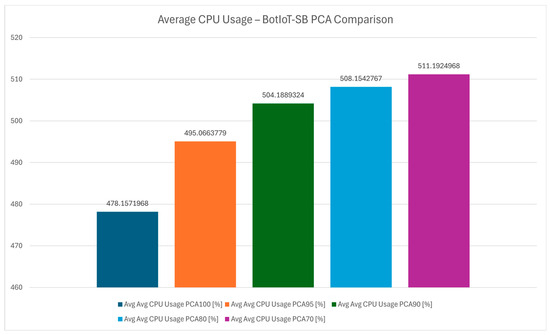

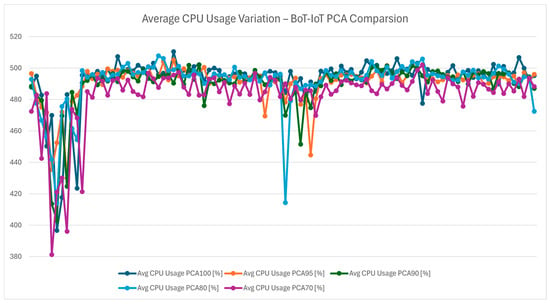

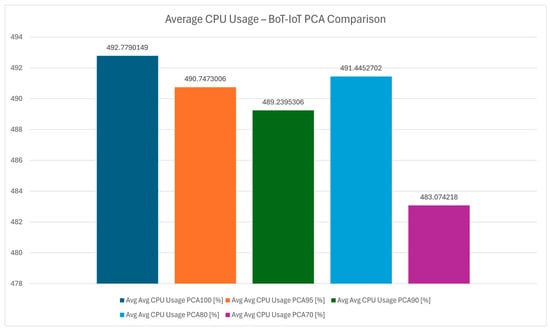

The average CPU usage variation chart from Figure 14 offers insights into the total CPU consumption across PCA levels. The chart reveals that with higher dimensionality reduction results in increased CPU usage. This trend is also reinforced in Figure 15 and it suggests that as PCA becomes more aggressive, additional computational effort is required to process the reduced feature set effectively. This increased CPU load could impact device longevity and energy efficiency, which are critical for smart-building systems. However, the CPU load does not feel much more aggressive than the PCA 100 and it still provides a stable and efficient system for long-term utilization.

Figure 14.

Average CPU usage variation—BotIoT-SB PCA comparison.

Figure 15.

Average CPU usage—BotIoT-SB PCA comparison.

These charts, as well as Table 9, demonstrate that PCA-enhanced XGBoost models improve intrusion detection in IoT smart buildings. The PCA 70 configuration consistently reduces CPU time, RAM usage, training time, and script execution time, making it ideal for real-time, resource-constrained devices. It also maintains high accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 scores across traffic types and classes. This balance of performance and efficiency makes PCA 70 perfect for scalable IDS deployment in IoT systems, effectively protecting smart-building networks from cyber threats while meeting resource constraints.

Table 9.

BotIoT-SB PCA 100 vs. PCA 70 comparison.

7.2. Bot-IoT Dataset

The evaluation of a rudimentary machine learning approach using the BoT-IoT dataset from Table 10 reveals outstanding performance metrics across various machine learning algorithms, with XGB being the most effective model. For attack-level classifications, all algorithms demonstrated near-perfect metrics, with XGB achieving 100% in each metric. This highlights its unparalleled ability to correctly identify attacks and minimize false positives or negatives. RF and DT also showed strong performances, with 99.99% accuracy and similar precision and recall scores, underscoring their robustness in handling diverse attack scenarios. However, NB lagged slightly, achieving a lower accuracy of 99.61%, which may be attributed to its probabilistic assumptions that are less effective with the dataset’s complexity.

Table 10.

Bot-IoT comparison of rudimentary ML algorithms’ performance.

In more granular classifications, such as the category and subcategory levels, the superiority of XGB is even more pronounced. It achieved nearly perfect metrics, with category-level accuracy reaching 99.97% and subcategory-level precision 99.88%. RF and DT performed well at these levels too, but XGB’s consistent precision and recall across all levels make it ideal for scenarios requiring detailed attack classification. NB’s performance dropped notably for category-level classifications, with an accuracy of 70.66% and F1 score of 68% indicating challenges in capturing nuanced distinctions between traffic types. These results emphasize the integration of XGB in the hybrid machine learning approach, demonstrating its ability to deliver high accuracy and reliability, making it a robust solution for IoT-enabled smart buildings where precision and adaptability are critical.

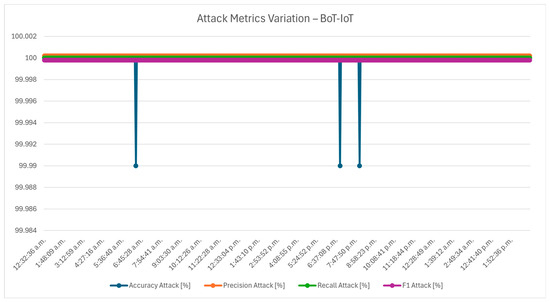

The chart in Figure 16 evaluates the hybrid protocol’s ability to differentiate between broad types of network traffic using key performance metrics: accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score. The attack-level metrics focus on capturing the characteristics of traffic, such as benign versus malicious behavior. A high accuracy here signifies the protocol’s overall reliability, while high precision highlights its capability to minimize false positives, a critical factor in IoT environments to avoid unnecessary disruptions. Recall and F1 score provide further depth, emphasizing the protocol’s ability to consistently identify malicious traffic without overlooking attacks. Together, these metrics reflect the foundational strength of the protocol, forming the first layer of validation for its application in smart buildings.

Figure 16.

Attack metrics variation—Bot-IoT.

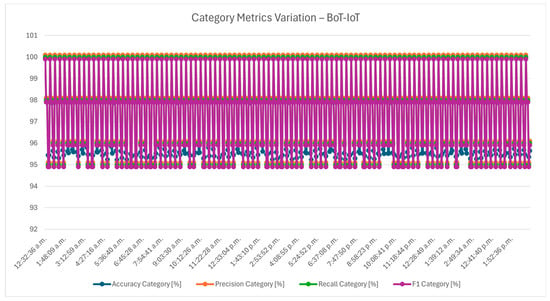

The category metrics variation from Figure 17 builds on the class-level analysis by diving deeper into individual traffic classes, such as specific types of malicious activities. By examining the same set of metrics at this finer granularity, the chart reveals how effectively the hybrid protocol can identify distinct patterns in various traffic categories. This analysis is critical for ensuring that the IDS can differentiate between different attack types, such as DoS, data exfiltration, or unauthorized access attempts. In an IoT context, where each category may represent a unique threat vector, these results underscore the protocol’s ability to safeguard smart buildings from diverse threats.

Figure 17.

Category metrics variation—Bot-IoT.

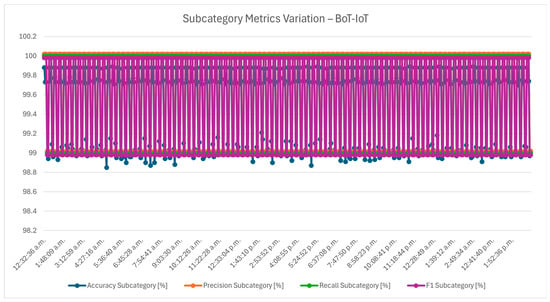

At the subcategory level, Figure 18 show the most granular distinction within the traffic, such as specific variations within broader attack categories. This chart evaluates the protocol’s precision and recall at this highly detailed level, which is essential for identifying subtle attack patterns that may otherwise go unnoticed. The ability to perform well at the subcategory level demonstrates the hybrid protocol’s nuanced understanding of IoT traffic, ensuring it can detect even sophisticated or low-signal threats. This capability is vital for smart buildings, where IoT devices often operate with minimal human oversight, making them attractive targets for subtle attacks.

Figure 18.

Subcategory metrics variation—Bot-IoT.

Table 11 provides the confidence intervals for the primary performance metrics of the hybrid model. Each metric includes its upper and lower bounds, defining the range within the true performance value is highly likely to fall. Across all metrics and network classifications, the confidence intervals demonstrate minimal variation, underscoring the models’ strong reliability at a comprehensive level. These intervals emphasize the consistent performance of the models across varying levels of granularity, with only minor fluctuations as the classification task becomes more specific.

Table 11.

Confidence intervals—Bot-IoT.

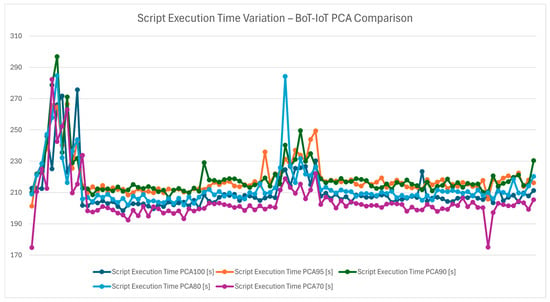

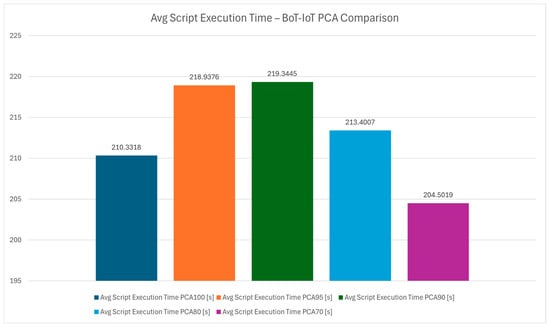

Figure 19 focuses on the execution time of the entire detection pipeline for different PCA configurations, while Figure 20 presents the average execution time of the detection pipeline. PCA is employed to reduce the dimensionality of the dataset, improving computational efficiency without compromising detection accuracy. By comparing execution times, the chart highlights how PCA 70 achieves the best trade off, minimizing processing time while retaining sufficient feature information for robust detection. In IoT systems where timely responses are critical, reducing execution time enhances the protocol’s suitability for real-time applications.

Figure 19.

Script execution time variation—Bot-IoT PCA comparison.

Figure 20.

Average script execution time—Bot-IoT PCA comparison.

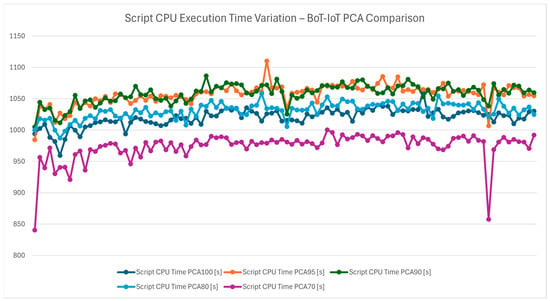

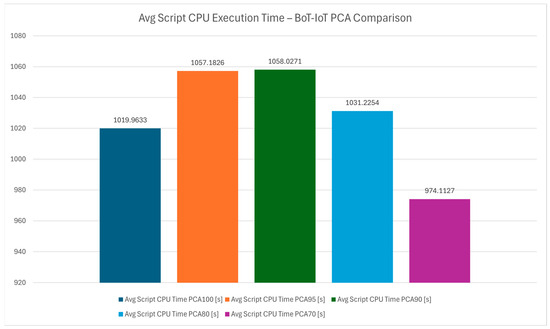

The chart in Figure 21 represents the CPU time consumed during script execution, further analyzing the computational load of the hybrid protocol. Figure 22 illustrates the average CPU time consumed during script execution. PCA 70’s efficiency is evident, as it reduces the burden on CPU resources while maintaining high detection accuracy. This finding underscores the protocol’s design for resource-constrained IoT environments, where devices may have limited processing capabilities.

Figure 21.

Script CPU execution time variation—Bot-IoT PCA comparison.

Figure 22.

Average script CPU execution time—Bot-IoT PCA comparison.

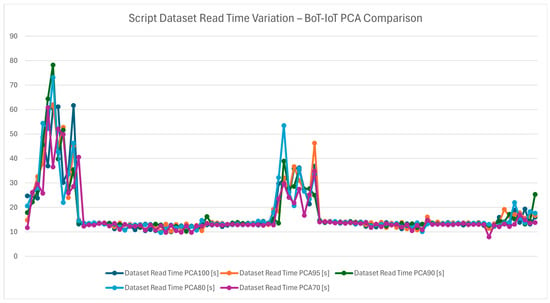

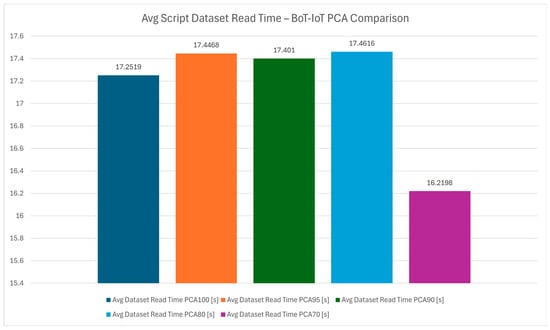

Figure 23 measures the dataset read time, which represents the efficiency of the data preprocessing phase, a critical step in the detection pipeline. This chart, as well as Figure 24 that shows the average dataset read time, highlights how PCA configurations impact the speed of reading and preparing the dataset for analysis. The reading times are similar across all PCA values as the same dataset is being used.

Figure 23.

Script dataset read time variation—Bot-IoT PCA comparison.

Figure 24.

Average script dataset read time—Bot-IoT PCA comparison.

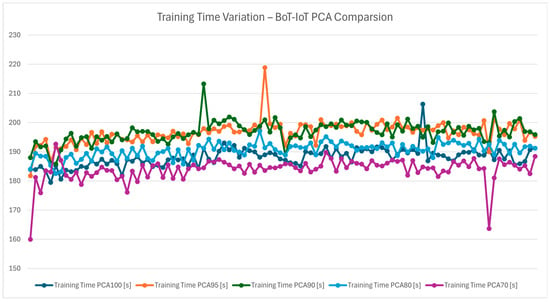

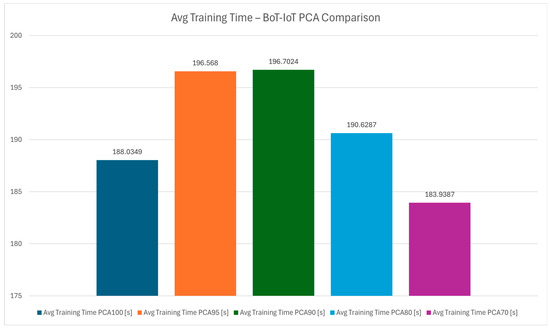

The chart in Figure 25 assess’ the training time, which is a key metric for the practicality of an IDS, especially in dynamic IoT environments where models may need frequent updates. Figure 26 contains the average training time of the detection pipeline and both this chart and the one in Figure 25 evaluate the time required to train the hybrid protocol across model updates without sacrificing performance. This agility is particularly valuable for adapting to evolving threat landscapes in smart buildings.

Figure 25.

Training time variation—Bot-IoT PCA comparison.

Figure 26.

Average training time—Bot-IoT PCA comparison.

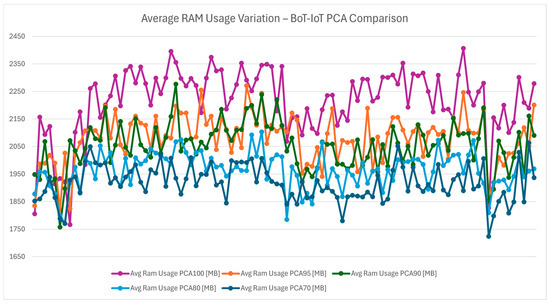

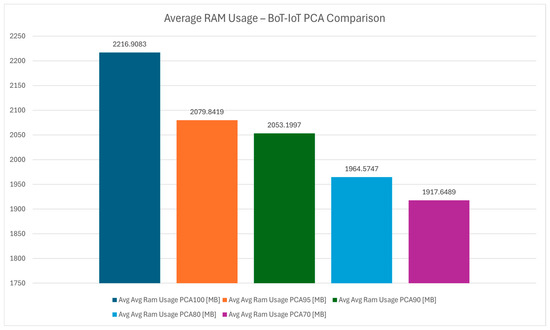

Figure 27 examines RAM usage across PCA configurations, focusing on memory efficiency during detection. PCA 70 stands out as the most memory-efficient option, reducing the protocol’s footprint on system resources, which is also proven in Figure 28 which illustrates the average RAM usage. This is a critical advantage in IoT devices, which often operate with limited RAM.

Figure 27.

Average RAM usage variation—Bot-IoT PCA comparison.

Figure 28.

Average RAM usage—Bot-IoT PCA comparison.

The chart in Figure 29 shows that the average CPU usage variation confirms PCA 70’s position as the most efficient configuration. This is further supported by Figure 30, which presents the overall average CPU usage, demonstrating that the protocol can achieve high performance with minimal energy consumption. This aligns with the goal of maintaining energy efficient IoT systems in smart buildings.

Figure 29.

Average CPU usage variation—Bot-IoT PCA comparison.

Figure 30.

Average CPU usage—Bot-IoT PCA comparison.

The detailed analysis provided showcases that the hybrid machine learning protocol is efficient as an IDS for IoT in smart buildings. The performance metrics at the attack, category, and subcategory levels highlight the protocol’s robust detection capabilities, while the PCA comparisons underscore its computational efficiency. Together, these results validate the protocol’s practicality, adaptability, and scalability, making it an ideal choice for securing smart buildings in a resource-constrained IoT ecosystem.

7.3. Experiment Conclusions

The experimental conclusions highlight the good efficacy and efficiency of the proposed hybrid machine learning protocol for an intrusion detection system in IoT-enabled smart buildings. Using the newly developed dataset, the system demonstrated robust detection capabilities across various classifications. The integration of XGB ensured high accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 scores, particularly at granular levels such as class and subclass classifications. The protocol’s use of PCA for dimensionality reduction proved crucial, balancing computational efficiency with high detection accuracy. PCA 70 emerged as the optimal configuration, significantly reducing execution time, memory usage, and CPU load while maintaining reliable performance metrics. These characteristics establish the protocol as a scalable and resource-efficient IDS suitable for dynamic IoT environments.

Similarly, results from the BoT-IoT dataset reinforced the system’s robustness and adaptability. XGB stood out as the most effective model, achieving perfect metrics for attack-level classifications and near-perfect results for category and subcategory levels, underscoring its capability to detect nuanced and sophisticated threats. Across both datasets, the protocol demonstrated consistent reliability, computational efficiency, and adaptability, proving its practical viability for securing smart buildings against evolving cyber threats. These conclusions affirm the hybrid protocol’s potential as a critical tool for enhancing IoT security in resource-constrained environments.

Despite promising results, there are potential limitations to the experiments and datasets used. The performance of the hybrid protocol may vary when applied to other IoT environments with different network topologies or device configurations, as the datasets used in this study were specific to smart buildings and may not fully represent the diversity of IoT ecosystems. Additionally, while the PCA 70 configuration provided optimal results in terms of computational efficiency, further investigation into other dimensionality reduction techniques and configurations could have even better performance. The protocol’s performance with real-time, high-volume attack data warrants further exploration, as the current datasets may not fully capture the full range of sophisticated and evolving cyber threats in dynamic IoT systems.

8. Future Development

The current research introduces an innovative intrusion detection system based on a hybrid machine learning approach that enhances IoT security at the edge, specifically for devices utilizing the TCP/IP protocol. By focusing on the model’s training time and optimizing detection accuracy, this system sets a foundation for secure IoT operations within resource-constrained environments, such as smart buildings. Despite these advancements, there are several promising directions for future development. These directions include an optimization of the model for greater efficiency, expanding its adaptability, integrating novel data sources, and exploring practical development strategies. By addressing these areas, future research can further strengthen IoT security and make the system more versatile and robust emerging IoT threats.

Real-time detection is essential for effective IDS, especially in IoT ecosystems where threats evolve rapidly. Integrating edge AI techniques could improve the IDS’s ability to detect and respond to threats with minimal latency. Future development should focus on edge AI frameworks that allow for real-time processing and decision making, potentially leveraging lightweight deep learning models or even hardware specific accelerators like Tensor-Processing Units (TPUs), Graphics Processing Units (GPUs), or Neural Processing Units (NPUs) suited for low-powered environments. By developing more computational power at the edge, the IDS could handle sophisticated threat detection directly on IoT devices, minimizing data transfer and thus enhancing both speed and data privacy.

To maximize the impact of the proposed IDS, it is crucial to explore its integration with broader IoT and smart-building systems. For instance, linking the IDS with building management systems (BMS) could provide an additional layer of security by allowing the IDS to act based on the contextual data from the building’s other IoT devices, such as access control lightning, and HVAC systems. This integration would allow for a more comprehensive threat response system capable of shutting down compromised devices or isolating affected networks automatically. Developing standardized communication protocols and APIs to facilitate this integration would be an essential step in this direction.

The proposed hybrid strategy is also designed to enhance security in an air-quality monitoring platform from University Politehnica Bucharest [44], and the design of the hybrid IDS represents the first step toward establishing extensive platform security. Currently, the platform is limited to providing air-quality readings, ensuring data integrity and reliability for environmental monitoring. By integrating the proposed intrusion detection system, we aim to safeguard the platform against potential cyber threats, creating a secure environment that can support additional functionalities. This enhanced security will enable the platform to evolve into a control system capable of autonomously adjusting air-quality parameters based on the monitored data, such as activating ventilation systems or issuing alerts in real time. These advancements will transform the platform into a dynamic, smart solution for improving indoor air quality, ensuring both operational efficiency and resilience against malicious attack. The efforts align with growing need for “secure-by-design” systems, as emphasized in the context of Smart Energy communities [45], where the early evaluation of cybersecurity risks is critical to ensure resilient and trustworthy platforms.

By pursuing these future directions, researchers and developers can build upon the proposed hybrid machine learning IDS to create more robust, efficient, and scalable solutions that meet the diverse security needs of modern IoT networks. As IoT ecosystems continue to expand and evolve, these advancements will be essential for maintaining strong security and trust in IoT devices and smart infrastructure worldwide.

9. Conclusions

This paper has presented a novel intrusion detection system based on a hybrid machine learning approach, designed to enhance the security of IoT devices at the edge, particularly those using TCP/IP protocol. By focusing on both training time and detection accuracy, the proposed system demonstrates a promising balance of speed and performance, addressing the unique challenges of securing IoT environments with limited resources, such as smart buildings.

A key strength of this research lies in its ability to outperform existing IDS models by leveraging a carefully curated combination of techniques. Unlike traditional IDS implementations, which often rely on singular or homogeneous approaches, the proposed system integrates complementary machine learning elements that work together. The strategic combination not only provides similar detection accuracy using a smaller dataset, but also reduces computational overhead, making the solution highly suitable for constrained hardware devices. By tackling the dual challenges of performance and resource efficiency, the proposed system represents a significant advancement in IDS design for IoT environments.

Another critical differentiator of this study is its use of a newly available public dataset to train and validate the hybrid model. While many prior studies utilized outdated or less diverse datasets, this paper ensures that the system is robust against a wider variety of modern threats. The experimental results confirm that the hybrid IDS delivers superior detection capabilities, identifying threats with higher precision compared to conventional models. The model’s ability to achieve these results without requiring extensive hardware resources makes it a groundbreaking solution for edge computing scenarios, where efficiency and speed are essential.

Additionally, the flexibility of the proposed hybrid approach allows for adaptability to various IoT applications, with a particular focus on smart-building environments. Its modular design ensures compatibility with a range of IoT devices, making it a versatile and scalable solution as IoT networks continue to evolve. Unlike other systems that often focus on specific device types or applications, the generalized applicability of this model positions it as an innovative tool capable of addressing the diverse and dynamic nature of IoT ecosystems. By ensuring robust and efficient threat detection, the proposed system supports the secure operation of critical smart-building functions, such as energy management, access control and environmental monitoring, reinforcing its practical relevance in this domain.

One critical shortcoming is the lack of comprehensive testing across diverse IoT systems and environments. The algorithm has been validated on specific datasets, such as the newly created dataset and BoT-IoT, but its effectiveness for other IoT platforms, with varying architectures and communication protocols, remains uncertain. Additionally, the dependency on PCA for dimensionality reduction, while efficient, might not generalize well to systems with highly dynamic or nonlinear data patterns, potentially limiting detection accuracy. The platform’s resource constraints, such as processing power and memory, could also hinder the scalability of the IDS when deployed in larger IoT ecosystems with more devices and complex interactions.

In conclusion, the proposed hybrid machine learning IDS offers a viable and flexible solution for securing IoT systems. By addressing the key limitations of prior models, such as excessive resource consumption, reliance on singular methods, and incompatibility with constrained devices, this study facilitates more efficient intrusion detection within the IoT domain. As the IoT landscape continues to expand, systems like this will play a crucial role in protecting IoT networks and supporting the secure integration of these technologies into everyday applications. Future work could explore refining the model to address emerging threats and extending its applicability to even more resource-constrained environments, ensuring sustained security in an increasingly connected world.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.-A.C. and R.N.P.; methodology, R.-A.C.; software, R.-A.C.; validation, R.N.P. and M.A.M.; resources, R.-A.C. and R.N.P.; data curation, R.-A.C. and Ș.M.; writing—original draft preparation, R.-A.C. and R.N.P.; writing—review and editing, Ș.M., M.A.M. and S.I.C.; project administration, R.-A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding